Abstract

Despite major advancements in mechanical circulatory support, the self-management (SM) for patients with a left-ventricular assist device (LVAD) remains complex and challenging for patients and their caregivers. We have developed a mobile phone application (VAD Care App) to organize and simplify the LVAD SM process. This paper describes the development and feasibility study of the app as an SM tool for LVAD patients and caregivers requiring support from VAD coordinators. The specific aim was to evaluate the app’s acceptability and usability, and the users’ competency. App features included an automated alert, data collection/reporting, and dynamic real-time interaction systems embedded in the LVAD SM process. Beta-testing of the prototype was completed by 5 adults. For the feasibility study, we employed a mixed-method descriptive research design involving 9 patients and 9 caregivers from 2 VAD Centers in the Midwest. We asked them to use the app daily for over 30 days and complete an app Evaluation Questionnaire and an interview. The questionnaire uses a 5-point rating scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree) evaluating usability, acceptability, and competency domains. Data generated from the questionnaires and interviews were analyzed with descriptive statistics and content analytic procedures. A total of 16 users (8 patients [all male] and 8 caregivers [7 female]) aged 22 to 68 years completed the 30-day study. Median acceptability, usability, and competency scores were 4.6, 4.5, and 4.7, respectively. Based on the data, it is feasible for patients and caregivers to use an app as an LVAD SM tool warranting further research.

Keywords: left-ventricular assist device, circulatory support, self-management, mobile health app, self-care, caregiver, VAD patients

Introduction

Self-management (SM) of an implantable LVAD is a collaborative effort among patients, caregivers, and VAD coordinators.1,2 This practice is aligned with contemporary theories that reach beyond traditional dyadic approach to SM (ie, patient-caregiver solely manages the treatment regimen in the home setting). Increasingly, patients with multiple co-morbidities are enlisting licensed healthcare professionals to assist them in achieving their SM goals.3,4 The triadic approach to LVAD SM includes the enactment of health behaviors (eg, daily tasks and procedures) by patients and/or caregivers supported by coordinators. The overarching goals of LVAD SM are to maintain the functionality of the LVAD system and to prevent complications, heart failure exacerbations, and hospital readmissions.5–7 Patients and caregivers acquire their LVAD SM competencies through education and training orchestrated by the coordinators pre-hospital discharge.7 Post discharge, they are provided with resources for LVAD SM including manuals, videos, and structured logs for tracking and reporting LVAD parameters (eg, flow), vital signs, coagulation profiles, symptoms, and medications, among others.5–7

Over the past decade, there have been reports regarding the patient and their family caregiver challenges in enacting LVAD SM. A large amount of information combined with LVAD self-care skills to be mastered and the complexity of daily home-care regimen is often overwhelming to them.1,5 These problems are commonly observed within 6 months post discharge when stress due to the adjustment of living with the LVAD is at its peak. This situation and the cognitive challenges lower their abilities and confidence (self-efficacy) in enacting the daily regimen.2,8–10 Emerging data shows the associations among low LVAD care self-efficacy, low adherence to the daily regimen, and poor quality of life.2,11 Some authors speculate that poor treatment adherence contributes to LVAD complications and hospital readmissions.12,13

To address the complexity of the LVAD SM and its processes, we have developed a mobile phone application named VAD Care app. The development process of the app and its feasibility as an LVAD SM tool are presented in this paper. The specific aim of the feasibility study was to evaluate the acceptability, usability, and competency of its users.

Methods

Mobile App Development

The Agile Model,14 a widely known method of software development, was used as the guiding framework for constructing and testing the prototype of the app. The model consists of 4 stages (conception, initiation and analysis, design and construction, and testing and deployment) describing the comprehensive process of software development.

Conception Stage

Theoretical and empirical knowledge demonstrate that the SM “process” is a major variable affecting treatment adherence, health, healthcare resource utilization, and quality of life outcomes.3,4,15,16 Thus, central to the design, content, and functionality of the VAD Care App are the key conceptual elements of SM process such as self-efficacy, goal setting, self-monitoring/reporting, and enlisting support from coordinators.3,4 Volunteer stakeholders (3 patient-caregiver pairs from an LVAD support group and 4 VAD coordinators from the Midwest) who supported the idea of developing the mobile phone app were asked by the lead author to create a list of tasks/procedures as preliminary content for the app. The list was revised and clustered according to LVAD SM goals commonly reported in clinical and research literature.1,5–7,17 Real-world relevance and practicality for initial development were also significant considerations in finalizing the list (Table 1). An iOS operating system was selected as a starting point for prototype development.

Table 1.

Content of VAD Care App

| LVAD SM Goals and Behaviors |

|---|

|

Initiation and Analysis Stage

A computer science student and a graphic designer were hired to develop an app prototype. At this stage, the design was seen as overly complex and drab and therefore in need of an overhaul. A technology solution architect was consulted, and a software development company specializing in mobile health apps was hired. Subsequently, the lead author convened a software development team (engineers and designers), a solution architect, and an information technology (IT) specialist to plan for the next stages of app development and testing.

Design and Construction Stage

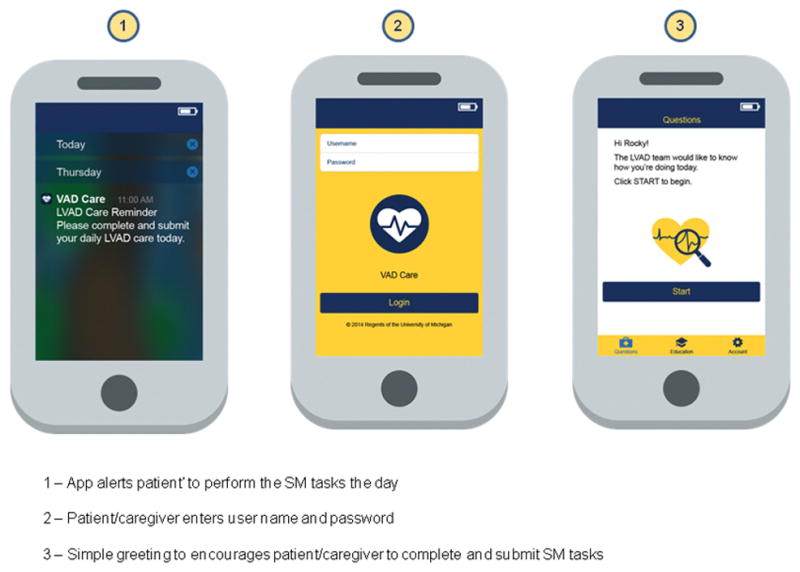

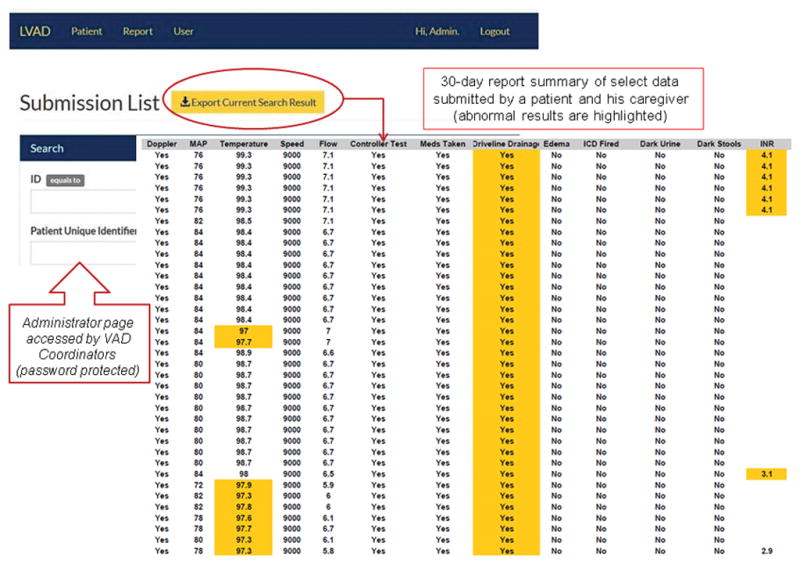

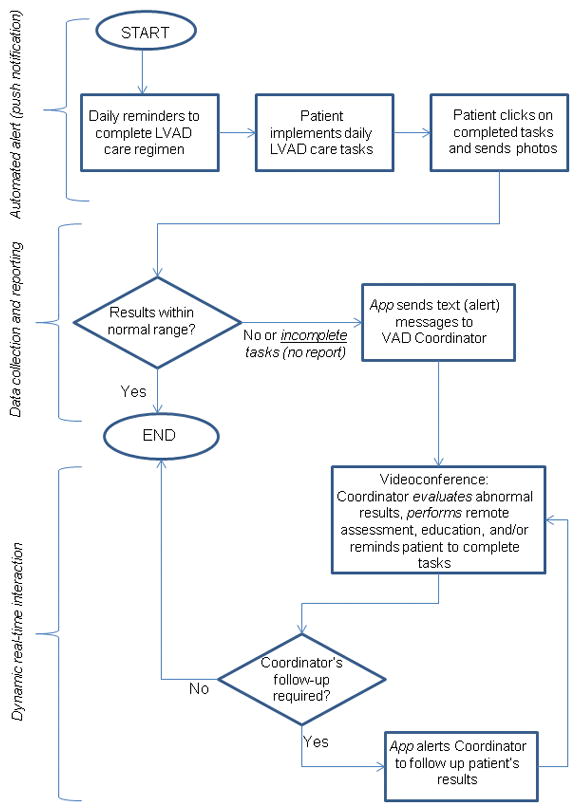

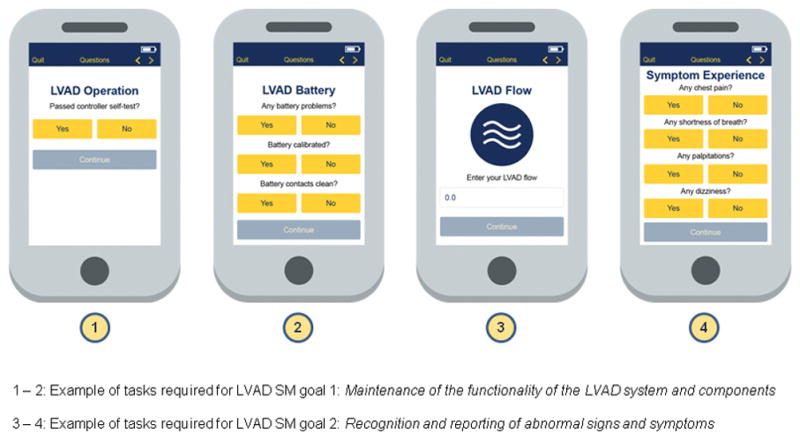

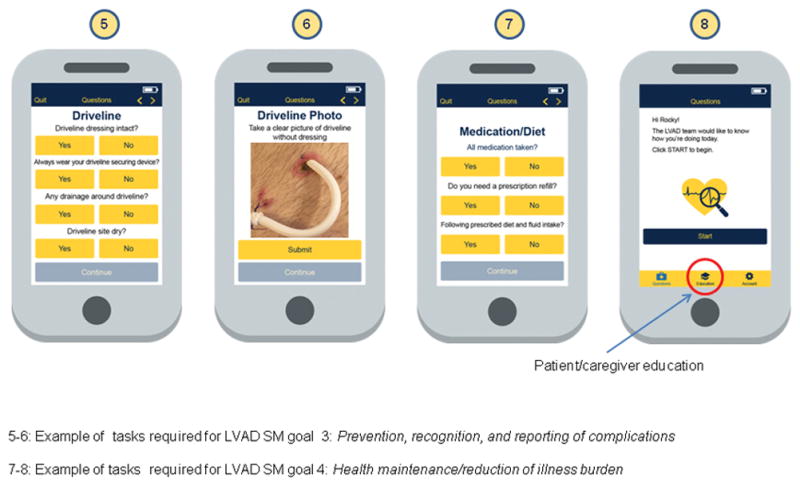

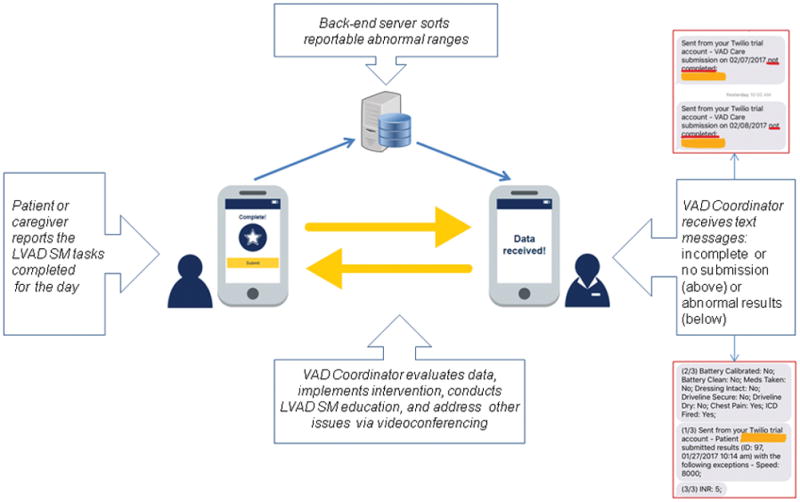

In keeping with the key conceptual elements of SM process cited above,3 we designed the app with 2 major goals: (1) assist patients and caregivers to manage the daily LVAD regimen more easily and efficiently, and (2) streamline the flow of communication between patient-caregiver and coordinators. Design features of the app include the following: (1) Automated alert is a daily push notification (ping) that reminds patients to complete the regimen and submit a photo of the driveline exit site; (2) Data collection and reporting is a built-in system that identifies abnormal results (eg, low LVAD flow) submitted by patients and/or caregivers, and will automatically notify coordinators in real-time via text messages; and (3) Dynamic real-time interaction (two-way communication system) is a feature that allows coordinators to evaluate and address abnormal results. This virtual clinic (using the phone’s videoconferencing feature) can also be used as a medium for addressing other health-related issues, conducting home environmental assessments (eg, electric outlets and dressing supplies storage), and SM skills review. Additionally, the app has built-in online LVAD SM videos that are easily accessible at any time. Figures 1 to 4 show some examples of app screens and a summary report generated by the back-end server, which is managed and protected by the IT specialist. A process flow chart in Figure 5 illustrates a summary of using the app in LVAD SM supported by VAD coordinators (Figure 5).

Figure 1.

Automated alerts (push notification) and launching screens

Figure 4.

Sample reports summary generated by the back-end server of VAD Care App 1.0

Figure 5.

Features of VAD Care App and App-Directed SM Process

Testing and Deployment Stage

Content and sequencing of cues or questions presented by the app were reviewed and subsequently revised by multidisciplinary VAD care team, lead author, and solution architect. Next, beta-testing was completed by 5 non-mobile app users (3 male and 2 female adults) to elicit objective opinions about the prototype. Each beta-tester took 2 to 3 minutes to respond to cues/questions presented by the app and to submit data. Based on their feedback, fonts and buttons were enlarged, sliders were changed to a keypad for inputting numerical data, and occasional Wifi disconnections were resolved. Before the feasibility study, the app was copyrighted. Also, approval from the institutional review board was obtained.

Feasibility Study

A mixed-method descriptive research design was employed to examine the feasibility of the app used in LVAD SM. Patients and caregivers (users) were recruited from 2 VAD Centers in the Midwest. Inclusion in the study was based on the following criteria: age 21 years or older; minimum of 6th-grade education; ability to read and comprehend the English Language; absence of cognitive impairment (Mini-Mental State Exam score of ≥ 24);18 and patients with LVADs <6 months post-hospital discharge.

Study Procedures

The study began with the creation of user name, password, and mobile phone app download. Patients and caregivers were trained by the research coordinator (RC) or the lead author in using the app. Demonstration of the correct use of the app, at least twice, denoted proficiency of its use. Patients and caregivers were instructed to implement the regimen daily, as directed by the app, for over 30 days. The lead author assisted the RC to address technical issues that arose during the study.

Data Collection

Study participants’ demographics and pertinent clinical information were collected through interviews and reviews of healthcare records. Feasibility data were collected using a 15-item App Evaluation Questionnaire developed by the research team. The questionnaire consisted of 3 domains (acceptability, usability, and competency) that are commonly measured in feasibility studies of mobile apps.19–21 The acceptability (5 items) and usability (6 items) measures consisted of questions relating to the ease of use and user’s experience of the app, respectively. The competency (3 items) measure consisted of questions relating to the user’s knowledge of the app within the context of LVAD SM. A 5-point Likert response scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) was used for the 14 items. Higher scores on the questionnaire indicate users’ favorable acceptance, usage, and competence of the app. An open-ended response format was used for item 15 to generate a comprehensive evaluation of the app. Semi-structured, face-to-face interviews were conducted by the lead author to clarify each participant/user’s response(s) to item 15. To elicit richer data, probing questions such as “Could you please explain your response to…” and, “please tell me more about your experience using the app?” were utilized as appropriate for each participant during interviews.

Data Analyses

Frequency distribution, median, and interquartile ranges (IQR) of demographics and feasibility data were calculated. Content analytic procedures22,23 were used to analyze the participants’ responses to open-ended questions and interviews. Repeated readings of the transcribed responses (verbatim), interviews, coding, and construction of preliminary themes were performed by 2 researchers (JC and MA). Themes descriptive of the participants’ appraisals of the app were finalized accordingly.

Results

Participants

Out of 11 patient-caregiver dyads screened, 9 dyads met the inclusion criteria and consented to participate in the feasibility study. However, at week 2, one dyad withdrew from the study due to frustrations with server malfunction, and thus, 8 dyads (8 patients [100% male] and 8 caregivers [87.5% female]) completed the 30-day study. The majority of the participants were White, married, and educated at or beyond high school. All patients were on disability leave, and all caregivers were employed full-time (Table 2). Sixty-three percent of patients received an LVAD with axial flow design, and 37% received an LVAD with centrifugal flow design. Indications for LVAD were bridge-to-transplant (75%), or destination therapy (25%) with implant durations ranged from 1 to 3 months. All participants had completed the required LVAD SM education/training pre-hospital discharge. Post discharge, all patients received the usual out-of-hospital care protocol established by their VAD Centers.

Table 2.

Participants’ Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristics |

n (%)*

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient (n=8) | Caregiver (n=8) | All (n=16) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 8 (100) | 1 (12.5) | 9 (56.2) |

| Female | 0 | 7 (87.5) | 7 (43.7) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Black | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (12.5) |

| White | 7 (87.5) | 7 (87.5) | 14 (87.5) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single/Divorced | 5 (62.5) | 1 (12.5) | 6 (37.5) |

| Married | 3 (37.5) | 7 (87.5) | 10 (62.5) |

| Education | |||

| High School | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | 8 (50.0) |

| Some College | 2 (25.0) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (31.2) |

| College and beyond | 1 (12.5) | 2 (25.0) | 3 (18.7) |

| Employment | |||

| Employed | 0 | 8 (100) | 8 (50.0) |

| Unemployed | 8 (100) | 0 | 8 (50.0) |

Due to rounding, not all percentages total 100

Acceptability

Participants’ median acceptability scores ranged from 4.0 to 5.0. The patients’ median score was slightly lower than caregivers (4.4 vs. 4.9), but not statistically significant. IQR ranged from 4.0 to 5.0 (Table 3). A theme descriptive of the app’s acceptability regards the participants’ ability to expand the functionality of the app by adding a trending/tracking function. The following excerpts elaborate this domain: “…add a calendar function that would give the patient access to see what was previously entered for VAD coordinators and Drs. visits… during visits with VAD coordinators, I was also asked about device averages (flow, power). If averages could also be tallied to the left or right of each calendar week, I think that would also help with information [Patient].” “…[it] would be nice to be able to see a graph of what everything was at say, last Tuesday? Add some way for us to see what his [patient] values are for the week so we could watch for any changes [Caregiver].” Other descriptors of acceptability included the following: Caregivers would like to see “a different link to specific medications as reminders” and they commented that the “driveline [care] question [should be presented] after the picture instead of before.” A notable descriptor of the acceptability domain was this quote from a caregiver: “…love the send a photo [function] to VAD team if there is a concern. It was very reassuring.”

Table 3.

Usability, Acceptability, and Competency of VAD Care App Users

| Domains and Items | Median and Interquartile Range (IQR)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n=8) | Caregivers (n=8) | All (n=16) | |

| Acceptability | |||

| 1. Using the app helped me remember the things I needed to do on a daily basis, which include taking medications, caring for my LVAD equipment, etc. | 5.0 (3.0–5.0) | 5.0 (4.2–5.0) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) |

| 2. The app helped me organize the things I needed to do for my LVAD. | 4.0 (4.0–5.0) | 4.5 (4.0–5.0) | 4.0 (4.0–5.0) |

| 3. If given the choice, I would use the app over the binder containing manuals, medication and LVAD records, etc. | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) | 5.0 (3.2–5.0) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) |

| 4. I would consider using the app for more than a month as a part of LVAD care. | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) | 4.5 (4.0–5.0) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) |

| 5. Overall, I am satisfied with my experience using app as a part of LVAD care. | 4.0 (4.0–5.0) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) |

| Total Score* | 4.4 (4.0–5.0) | 4.9 (3.8–5.0) | 4.6 (4.0–5.0) |

| Usability | |||

| 1. The app is easy to use. | 5.0 (5.0) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) |

| 2. The app works well with few or no glitches. | 4.0 (3.0–4.0) | 4.0 (4.0) | 4.0 (4.0) |

| 3. The app works quickly. | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) |

| 4. I can easily locate the app button on the phone. | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) | 5.0 (4.2–5.0) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) |

| 5. The display on the phone is easy to read. | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) | 4.5 (4.0–5.0) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) |

| 6. The display on the phone is easy to understand. | 5.0 (5.0) | 5.0 (5.0) | 5.0 (5.0) |

| Total Score* | 4.6 (4–4.8) | 4.5 (4.4–4.8) | 4.5 (4.3–4.8) |

| Competency | |||

| 1. I know the importance of completing the tasks, on the phone, for my LVAD and my health. etc. | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) | 5.0 (4.2–5.0) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) |

| 2. I would recommend this phone app to someone who has an LVAD. | 5.0 (5.0) | 5.0 (4.2–5.0) | 5.0 (5.0) |

| 3. With the phone app, I felt well-connected with my LVAD team. | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 4.0 (3.2–4.7) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) |

| Total Score* | 4.3 (4.3–4.7) | 4.7 (4.1–4.9) | 4.7 (4.3–4.7) |

Note: Response scale: 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neutral; 4 = agree; 5 = strongly agree;

not statistically significant (p>.05)

Usability

Participants’ median usability scores ranged from 4.0 to 5.0. Here, caregivers slightly scored lower on usability than patients (4.5 vs. 4.6), but not significant. IQR ranged from 4.3 to 4.8 (Table 3). Themes descriptive of the usability of the app were simplicity and efficiency. Ease of use was particularly evident, stated by one caregiver as: “I’m 62…if I can do it, anybody can.” Likewise, participants appraised the efficiency of the app, noting that it was “very helpful” and “quiet easy to use.” The app “kept [them] us most organized since leaving the hospital” and “It’s always good to have reminders.” Additional descriptors of usability domain were the following: (1) “They [online videos] were a comfort to know we had them and could refer to them if we needed to [Patient];” (2) “I found it very helpful with my day-to-day care [Patient]; and (3) “He would rather keep the phone than the binder [Caregiver].”

Competency

Participants’ median competency scores ranged from 4.0 to 5.0. The patients’ median score was lower than caregivers (4.3 vs. 4.7), but not significant. IQR ranged from 4.3 to 4.7 (Table 3). Thematic description of the competency domain included the participants’ knowledge of the app as an efficient communication tool with coordinators supporting LVAD SM. Excerpts from 2 caregivers about this domain were: “I thought it was a very good communication between the VAD team and us,” and, “When we use the app it’s being sent to the team, where they can view the daily data whereas the binder is only for us to see until we have doctor’s visit.”

Discussion

We report the outcome of development and feasibility study of the VAD Care App as an LVAD SM tool in the home setting. Its purpose, to assist patients and caregivers in the LVAD SM process, is aligned with increasing use of mobile phones as SM tools in populations with complex chronic conditions. 27–29 Such trends are affirmed by stakeholders who are primarily involved in the LVAD SM process. The ubiquity of mobile phones in day-to-day living,30 as well as them being the healthcare providers’ preferred communication tool, further support the need for app development.31 Stakeholders and laypersons’ input is central to the design of the app. The theoretical-empirical-clinical knowledge1,3–5,7,15–17 underpinning the concept of the app is fundamental to the advancement of LVAD SM science.

To the best of our knowledge, the VAD Care App is the first LVAD SM tool designed by and for patients, caregivers, and coordinators primarily engaged in the SM process. Aspects of the app that are distinct from other programs are its rigorous conceptualization and beta-testing. There are 3 existing programs that offer some of the features of the app (eg, self-monitoring and reporting). Each program uses a different computing platform, including desktop (VADWatch, USA),24 tablet (LVAD@home, Japan),25 and mobile phone (VADable, USA).26 However, none of these programs have described the purpose of its monitoring and reporting feature in the context of LVAD SM. Of these, only LVAD@home has been published in a peer-reviewed journal. The authors reported a successful use of LVAD@home by a 64-year-old patient for over 305 days in Japan. LVAD@home provided the patient with an efficient way to report the “clinical information,” such as LVAD parameters, driveline photo, and laboratory values, to the attending physician. It uses a cloud-based text messaging function for data storage and reporting.25

From the design perspective, none of these programs24–26 have an automated alert (push notifications) system that could help patient and caregiver increase their adherence to the daily regimen. This alert system may also potentially replace the frequent telephone follow-up by coordinators.1 The two-way communication (Figure 4) is another feature distinct to the design of the VAD Care App, in comparison with the programs above.24–26 This feature may facilitate the development and enhancement of patients and/or caregivers’ self-efficacy. The ability to complete and report the tasks/procedures required for daily LVAD care may build a patient or caregiver’s sense of accomplishment (Figures 4 and 5) leading to an increased in self-care efficacy.9,10 Furthermore, the constructive feedback provided by coordinators via text messaging or video conferencing may also reinforce self-efficacy building.9,10 Collectively, these mechanisms, paired with the seamless flow of communication, between patient-caregiver and coordinator, may increase self-efficacy for and adherence to daily care regimen. Self-efficacy and adherence are known behavioral factors influencing SM outcomes including quality of life.15,16 The successful completion of our feasibility study can be explained in part by its resolution of common mobile app design pitfalls (eg, an absence of stakeholders’ input) and its completion of comprehensive beta-testing.14,32,33 The success is reflected by patients’ and caregivers’ high favorable ratings of acceptability, usability, and competency—namely, a high level of understanding about the utility of the app as an LVAD SM tool (Table 3). The 80 to100% daily submission rates, which implied completion of the regimen along with the patients’ and caregivers’ recommendation to further improve the functionality of the app, are suggestive of a successful feasibility outcome. Notably, a patient-caregiver pair from each center requested to continue using the app for another month.

Results of the feasibility study also initiated the bridging of the gap of knowledge in the mobile health apps, which is the role of a healthcare provider in app data management.34 In the feasibility study, we enlisted the 4 VAD coordinators to test some features of the app. They tested the videoconferencing feature of the mobile phone for remote home environment assessment and LVAD care competency reassessments during weeks 1 and 3 of the study. A total of 8 users (4 patient-caregiver dyads) from Center # 2 agreed to test these features. The amount of time required for coordinators to complete assessments and reassessments ranged from 21 to 45 minutes, without difficulty. According to the coordinators, they were able to integrate the app data management in their workflow for over 30 days, and they found that the data summary (Figure 5) was helpful with patient care.

Limitations and Future Directions

The sample was limited to users with an iOs operating system, who are mobile phone-literate with normal cognitive function, relatively educated, and are residents of the Midwest. There is no set criteria for sample size, and the use of questionnaires like ours are common in this type of study,20–21 so we also acknowledge these as limitations. The app evaluation questionnaire that was adopted from published studies20–21 may not provide a comprehensive description of the feasibility domains under investigation. However, these were offset by the quantitative-qualitative methods that generated acceptability, usability, and competency data. These data were deemed sufficient in helping us prepare for a pilot randomized control trial (RCT) and design the VAD Care App 2.0.

Future studies should address these limitations to include diverse and large sample size from multiple centers across the US. Moreover, a comprehensive evaluation of the role and workload of the coordinators caring for patients/caregivers with the app will be included. Longitudinal and intervention studies (RCTs) are warranted to (a) understand the mechanism of the effect of the app on LVAD SM process and outcomes, (b) determine its sustainability and scalability that are essential for translating knowledge into clinical practice, and (c) modify its functionality in response to changes in LVAD designs.

Conclusion

It appeared feasible using an app in assisting LVAD patients and caregivers to implement and manage the complex care regimen. Longitudinal research is needed to examine the long-term usability and acceptability of the VAD Care App. Furthermore, the effects of the app on the VAD coordinators’ workload and patients/caregivers’ burden in the context of a more organized and simplified LVAD SM process also warrant investigation. Research designs aimed at understanding the mechanism by which the app improves behavioral (eg, self-efficacy and adherence), clinical (eg, complications), healthcare resource utilization (eg, hospital readmission), health, and quality of life outcomes. Future revisions of the content and architecture of the app are expected to occur in concert with the evolving LVAD technology.

Figure 2.

LVAD SM goals, tasks completion, and submission screens

Figure 3.

Reporting, submission, and dynamic real-interaction feature

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding

This study is funded by the NIH P20NR015331 and the University of Michigan School of Nursing, Ann Arbor, MI

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Logic Solutions, Inc., Kinnothan Nelson, and the VAD care teams at the University of Michigan Health System and Barnes-Jewish Hospital Washington University during the conceptualization, construction, and testing of the app.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None

References

- 1.Smith EM, Franzwa J. Chronic outpatient management of patients with a left ventricular assist device. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:2112–24. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.10.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casida JM, Wu HS, Abshire M, Ghosh B, Yang JJ. Cognition and adherence are self-management factors predicting the quality of life of adults living with a left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36:325–30. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2016.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan P, Sawin KJ. The Individual and Family Self-Management Theory: background and perspectives on context, process, and outcomes. Nurs Outlook. 2009;57:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grey M, Schulman-Green D, Knafl K, Reynolds NR. A revised self- and family management framework. Nurs Outlook. 2015;63:162–70. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casida JM, Peters RM, Magnan MA. Self-care demands of persons living with an implantable left-ventricular assist device. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2009;23:279–293. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.23.4.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kato N, Jaarsma T, Ben Gal T. Learning self-care after left ventricular assist device implantation. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2014;11:290–8. doi: 10.1007/s11897-014-0201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Widmar SB, Dietrich MS, Minnick AF. How self-care education in ventricular assist device programs is organized and provided: a national study. Heart Lung. 2014;43:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casida JM, Marcuccilli L, Peters RM, Wright S. Lifestyle adjustments of adults with long-term implantable left ventricular assist devices: a phenomenologic inquiry. Heart Lung. 2011;40:511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casida J, Wu SH, Harden J, Chern J, Carie A. Development and initial evaluation of the psychometric properties of self-efficacy and adherence scales for patients with a left ventricular assist device. Prog Transplant. 2015;25:107–115. doi: 10.7182/pit2015597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casida J, Wu HS, Harden J, Carie A, Chern J. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of self-efficacy and adherence scales for caregivers of patients with a left-ventricular assist device. Prog Transplant. 2015;25:116–23. doi: 10.7182/pit2015556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casida J, Wu H, Senkiv V, Yang JJ. Self-efficacy and adherence are predictors of quality of life in patients with left ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:S90–S91. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forest SJ, Bello R, Friedmann P, et al. Readmissions after ventricular assist device: etiologies, patterns, and days out of hospital. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:1276–81. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasin T, Marmor Y, Kremers W, et al. Readmissions after implantation of axial flow left ventricular assist device. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:153–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banos O, Villalonga C, Garcia R, et al. Design, implementation and validation of a novel open framework for agile development of mobile health applications. Biomed Eng Online. 2015;142:S6. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-14-S2-S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lorig KR. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grady PA, Gough LL. Self-management: a comprehensive approach to management of chronic conditions. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e25–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldman D, Pamboukian SV, Teuteberg JJ, et al. The 2013 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines for mechanical circulatory support: executive summary. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:157–87. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davidson KW, Goldstein M, Kaplan RM, et al. Evidence-based behavioral medicine: what is it and how do we achieve it? Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:161–71. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2603_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Free C, Phillips G, Lamber F, Galli L, Patel V, Edwards P. The effectiveness of m-health technologies for improving health and health services: a systematic review protocol. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:250. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodgers CC, Krance R, Street RL, Hockenberry M. Feasibility of a symptom management intervention for adolescents recovering from a hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36:394–99. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31829629b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meredith SE, Robinson A, Erb P, et al. A mobile-phone-based breath carbon monoxide meter to detect cigarette smoking. Nicotene Tob Res. 2014;16:766–73. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334–40. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alere. Alere VADWatch Home Telemonitoring Program Hospital User Instruction Manual. Orlando, FL: Alere Home Monitoring, Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nomoto S, Utsumi M, Minakata K. A cloud-based home management system for patients with a left ventricular assist device: a case report. Int J Artif Organs. 2016;39:245–48. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.University of Southern California Center for Body Computing. [Accessed February 21, 2017];VADable The Life Companion for Patients with an Artificial Heart Pump. https://www.uscbodycomputing.org/vadable/

- 27.Parmanto B, Praman G, Yu DX, Fairman AD, Dicianno BE, McCue MP. iMHere: A novel mHealth system for supporting self-care in management of complex and chronic conditions. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2013;11(1):e10. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panagioti M, Richardson G, Small N, et al. Self-management support interventions to reduce healthcare utilisation without compromising outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:356. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whitehead L, Seaton P. The effectiveness of self-management mobile phone and tablet apps in long-term condition management: A systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2016;16(18):e97. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pew Research Center. [Accessed January 31, 2017];Mobile Fact Sheet. 2007 Jan 12; http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/

- 31.Patel B, Johnston M, Cookson N, King D, Arora S, Darzi A. Interprofessional communication of clinicians using a mobile phone app: A randomized crossover trial using simulated patients. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e79. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCurdie T, Taneva S, Casselman, et al. mHealth consumer apps: the case for user-centered design. Biomed Instrum Technol. 2012;(Suppl):49–56. doi: 10.2345/0899-8205-46.s2.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schnall R, Rojas M, Bakken S, et al. A user-centered model for designing consumer mobile health (mHealth) applications (apps) J Biomed Inform. 2016;60:243–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh K, Drouin K, Newmark LP, et al. Many mobile health apps target high-need, high-cost populations, but gaps remain. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;1:2310–18. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]