Abstract

Purpose

Childhood cancer survivors (CCS) report high unmet information needs. This study examined the prevalence of cancer-related information-seeking among CCS, and investigated associations between information-seeking behavior and positive health outcomes such as follow-up care.

Methods

Participants (n=193) were young adult CCS diagnosed with cancer in Los Angeles County, 54% of Hispanic ethnicity, with a mean age of 19.87, in remission, and at least two years from completion of treatment. CCS were asked where they accessed health information related to their cancer with response options categorized into four information domains: hospital resources, social media, other survivors, and family members. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess variables associated with each information domain, including sociodemographics, post-traumatic growth (i.e., reporting positive changes since cancer diagnosis), health care engagement, level of education, and health insurance status.

Results

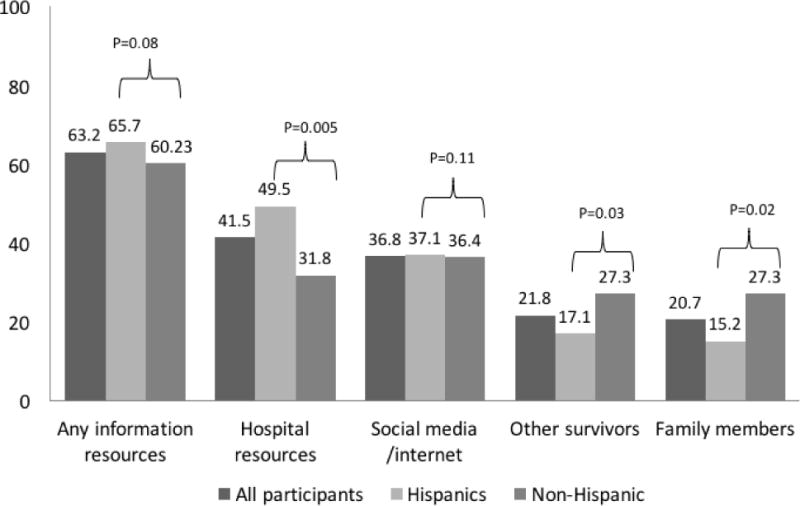

Hospital resources were the most commonly accessed information domain (65.3%), and CCS of Hispanic ethnicity (vs. non-Hispanic) were more likely to access this source. Seeking information from other cancer survivors was positively associated with follow-up care and post-traumatic growth. Hispanic CCS were marginally less likely to seek information from other survivors and family than non-Hispanics.

Conclusions

While CCS obtain information from a variety of sources, hospital resources are an important site for access, particularly for individuals of Hispanic ethnicity. Information sharing between survivors may promote positive health care engagement; however, Hispanic CCS may be less likely to utilize this resource and may face barriers in information sharing with other cancer survivors.

Keywords: Child, Adolescent, Young adult, Cancer, Survivorship, Hispanic ethnicity, Health information-seeking

Introduction

Childhood cancer survivors (CCS) have unique needs related to their cancer diagnosis and treatment [1, 2]. To address these needs, specialized survivorship programs have been developed, including coordinated long-term follow-up (LTFU) services to monitor and manage late effects of treatment, provide psychosocial services, and deliver cancer-related health information. Unfortunately, only a minority of survivors access such resources [3]. Non-utilization of survivorship-focused resources contributes both to inadequate medical surveillance for CCS and to missed opportunities for provision of cancer-related health education and promotion that could improve outcomes. As a result, there is a high prevalence of unmet cancer-related information needs among CCS, including basic health education about their disease, level of risk for late effects, risk-reduction strategies, and financial issues such as access to health insurance [4–7]. Such information deficits have been associated with lower quality of life among young adult cancer survivors, and may impact survivors’ ability and motivation to engage in their health care, including engagement in LTFU [8, 9].

Historically, studies addressing unmet information needs of CCS and adolescent and young adult (AYA) survivors have focused on deficits in the provision of information and content sought, particularly in the clinical setting, rather than on the information-seeking habits of this population [5, 8, 4, 9, 6]. However, a literature has emerged on the information-seeking patterns of individuals affected by cancer. Both cancer patients and survivors access information from a variety of sources, including clinical settings, mass media, peer exchange with other survivors (in-person or online via websites or social media), and family members, and often use multiple sources to learn about their disease [10–12]. Cancer patients and survivors may seek information outside of clinical settings because they do not fully understand information provided by their physicians, or to access other sources to aid in health decision-making [12]. Because such activities may influence health care decisions and care engagement, it is important to understand the extent and patterns of information-seeking among both cancer patients and survivors [12].

Additionally, there is evidence that the active seeking of cancer-related health information among older patients is associated with positive health behaviors, including greater knowledge of cancer and one’s health risks, better psychological adjustment, greater health care self-efficacy, greater health prevention behaviors, and greater adherence to treatment regimens and post-treatment follow-up [13–16]. Not seeking health information may also be an indicator for engaging in risk behaviors; for example, childhood cancer survivors who smoke tobacco have reported infrequent or no health information-seeking [17].

Seeking health information, then, may indicate overall health care engagement for CCS. Knowing where CCS seek information may provide insights regarding relevant information delivery sources for this population. To investigate these issues, the present study examined cancer-related health information patterns of young survivors of childhood cancer. Our research questions were twofold: 1) what information sources do CCS use for accessing cancer-related information? and 2) what is the relationship between information-seeking and positive health outcomes among these survivors? Given previous research, we hypothesized that greater information-seeking would be associated with more positive health outcomes, including greater engagement in follow-up cancer-related care in this population.

Our multiethnic sample, comprising 54% survivors of Hispanic ethnicity, enabled comparisons between the health information-seeking habits of Hispanic and non-Hispanic CCS. Studies have shown that individuals of Hispanic ethnicity may be less likely to seek cancer-related health information than other ethnic and racial groups including non-Hispanic whites (NHWs) potentially due to issues of health literacy or a lack of culturally competent sources tailored to Hispanic survivors [18]. In addition, information-seeking is influenced by educational and socioeconomic status (SES), with more highly educated, higher SES individuals more likely to actively seek health-related information than lower SES, less educated individuals [19]. Further, patients with higher levels of education are more likely to seek health information from the internet and other mass or social media sources [19]. Because individuals of Hispanic ethnicity are more likely to be from lower SES backgrounds, to have attained a lower level of education, and to possess lower health literacy than non-Hispanics (particularly NHWs), we hypothesized that Hispanic CCS may be less likely to seek cancer-related information that non-Hispanics overall, and less likely to do so from social media and internet information sources [20, 21].

Methods

Data source

Data used for this analysis are from the Project Forward pilot study, a cross-sectional study evaluating health outcomes in a cohort of CCS (n=193) diagnosed with any type of cancer from two large pediatric medical centers in Los Angeles County between 2000–2007. Survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma were excluded due to participation in another cancer registry study. Participants were diagnosed between the ages 5–18 years and were between 15–25 years at the time of data collection in 2009; all participants were 2 or more years from treatment for their cancer. Study procedures have been detailed elsewhere [22]; briefly, CCS were identified through the Los Angeles Cancer Surveillance Program, the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Cancer Registry covering Los Angeles County, and were mailed a survey to complete. Information on race and ethnicity was obtained by participant self-report. To identify Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, participants were asked “how would you describe yourself?” with “Hispanic or Latino” as one of the response options.

The recruitment rate for the study was 50 percent, comparable to or exceeding similar population-based studies [23]; among those who were able to be located, the participation rate was 61 percent. As previously reported, characteristics of respondents and non-respondents that were available for the complete sample based on variables in the cancer registry database were compared, and no differences were found with respect to clinical factors, current age, age at diagnosis, or ethnicity, although females (vs. males), and those who resided in areas of high SES (vs. low) were more likely to respond. We performed a stratified analysis to assess variables associated with response for Hispanic individuals separately, and found that no variables were associated with responding among Hispanic CCS [22]. The study was approved by the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, the California Cancer Registry, and the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Southern California and both pediatric hospitals.

Measures

Outcomes

Participants were asked the question, “In the past two years, have you gotten information (or looked for information) about your cancer from any of the following?” with 8 response options. For the purpose of the present study, responses were categorized into four information domains: 1) hospital resources (including resource centers, specialized survivorship programs, and social workers); 2) social media and the internet (including contemporaneous social media sites such as Facebook and cancer-related internet sites such as Planet Cancer); 3) information obtained from other survivors; and 4) information obtained from family members. Each domain was dichotomized to represent participant endorsement of seeking information from that source (1), or non-endorsement (0). In addition, an overall item was created to indicate whether participants sought information from any of the four domains, with endorsement indicating that the participant had responded affirmatively to any of the 8 items.

Health Care Engagement

Several items pertaining to healthcare treatment, access, and planning were included in the present study. Participants were asked whether they had a regular source of both cancer and non-cancer (e.g., primary) care; whether they had seen a doctor for cancer follow-up care in the past two years; and whether they discussed their future health care with their doctors. All items were dichotomized (yes/no).

Clinical factors

Two items of clinical relevance were included. The intensity of prior cancer treatment was categorized using the Intensity of Treatment Rating Scale 2.0 (ITR-2) [24], a validated scale that was applied here to cancer registry data and medical chart review. Treatment was categorized by four levels of intensity: 1 = least intensive (e.g., surgery only), 2 = moderately intensive (e.g., chemotherapy or radiation), 3 = very intensive (e.g., two or more treatment modalities), and 4 = most intensive (e.g., regimens for relapsed disease including hematopoietic cell transplantation). In addition, time (years) since cancer diagnosis was obtained from cancer registry data.

Psychosocial factors

Health care self-efficacy (HCSE)

The HCSE scale was adapted from the Stanford Patient Education Research Center Chronic Disease Self-Efficacy scales [25]. The scale included three items related to survivors’ perceived confidence in discussing concerns with their physicians, making appointments with physicians, and obtaining cancer follow-up care in the next two years. Responses comprised a 3-point Likert-type scale ranging from ‘not confident/not sure’ to ‘very confident.’ Items were summed to form a continuous composite score (ranging from 3–9) with higher scores indicating greater HCSE. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was 0.64.

Post-traumatic growth

The Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) short form is a 10-item measure of personal growth experienced by individuals who have undergone a traumatic event, in this case cancer [26]. Items reflect different areas of growth, including relating to others, new possibilities, personal strength, spiritual change, and appreciation of life. Responses are based on a 6-point scale ranging from 0 (“I did not experience this change”) to 5 (“I experienced this change to a very great degree”). A total PTGI mean score was calculated, with higher scores indicating greater post-traumatic growth. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was 0.90.

Depression symptoms

The 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to assess symptoms of depression [27]. Participants indicated how often they had experienced symptoms (e.g., depressed mood, loss of appetite, sleep and psychomotor disruption, and feelings of guilt and worthlessness and/or helplessness and hopelessness) during the previous week on a 4-point ordinal scale ranging from ‘rarely or none of the time’ (less than 1 day) to ‘most or all of the time’ (5–7 days). A total score was calculated with higher scores representing higher levels of depressive symptoms. The Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was 0.92.

Knowledge of follow-up care

A single item assessed participants’ knowledge of the need for long-term follow-up care. Participants were asked how long they should remain in follow-up care; responses ranged from ‘less than 5 years’ to ‘my whole lifetime’ (the correct answer). The item was dichotomized as the correct answer versus all incorrect responses as the reference group.

Covariates

Covariates included age at time of survey dichotomized as <21 years and ≥21 years (a distinction representing the age of transfer from pediatric to adult-centered health care providers at the study sites); ethnicity (self-reported Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic ethnicity); sex; level of education; and health insurance status. Health insurance status was dichotomized as any health insurance (public or private) vs. no insurance coverage.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive frequencies and means were used to describe the sample. Pearson’s chi-square tests were used to compare statistical differences in the proportions of Hispanic (vs. non-Hispanic) CCS endorsing information-seeking. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression was then performed. In the first step of the analysis, bivariate analyses were conducted with variables selected for their theoretical significance to the outcomes; p <0.10 was the entry threshold for the multivariable model. In the second step, significant variables were entered into multivariable regression models. Current age, sex, Hispanic ethnicity, and health insurance status were included in all multivariable models as these covariates are of theoretical importance in the relationship between the exposure variables and the outcomes. All tests were two-tailed, with an alpha criterion of p < 0.05. Because of multiple comparisons, the Bonferroni correction was applied: alpha = 0.05/5 = 0.01. All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software (Version 9.4) (SAS Institute; Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Selected characteristics of sample

Socio-demographic data are presented in Table 1. Roughly half of respondents were female and 54% were of Hispanic ethnicity. The median age of the sample was 21, and the majority of participants had at least a high school education (69%). More than 80% reported some type of health insurance, and 73% reported having seen their physician for cancer-related follow-up care within the past two years. Two-thirds reported a usual source of care, including a cancer and a non-cancer provider.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of sample (n=193)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at survey completion | ||

| 15–20 | 114 | 59.1 |

| 21–25 | 79 | 40.9 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 96 | 49.7 |

| Male | 97 | 50.3 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 105 | 54.4 |

| Non-Hispanic | 88 | 45.6 |

| Cancer follow-up care in past two years | ||

| Yes | 140 | 72.5 |

| No | 51 | 26.4 |

| Missing | 2 | 1.0 |

| Regular cancer provider | ||

| Yes | 123 | 64.7 |

| No | 67 | 35.3 |

| Regular non-cancer provider | ||

| Yes | 124 | 64.6 |

| No | 68 | 35.4 |

| Level of education | ||

| <High school | 56 | 29.0 |

| High school | 44 | 22.0 |

| Some college | 55 | 28.5 |

| Associate/college degree | 36 | 18.6 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.5 |

| Any health insurance | ||

| Yes | 154 | 81.1 |

| No | 36 | 19.0 |

Prevalence of information-seeking

Prevalence of information-seeking is shown in Figure 1. Sixty-three percent of participants accessed any cancer-related health information across all domains. A significantly greater proportion of Hispanic (vs. non-Hispanic) participants accessed cancer-related health information from hospital resources (49.5% vs. 31.8%; p=0.005). Conversely, a greater proportion of non-Hispanic than Hispanic CCS accessed information from other survivors (27.3% vs. 17.1%; p=0.03) and from family members (27.3% vs. 15.2%; p=0.02).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of information-seeking among childhood cancer survivors by information domain.

Factors related to utilization of health information by category

Any cancer-related information resources

The relationship between clinical, psychosocial, and socio-demographic factors and seeking any cancer-related information is shown in Table 2. In bivariate analyses, having a regular source of cancer care, having cancer follow-up care in the past two years, discussing cancer follow-up care with one’s physician, and greater post-traumatic growth were all significantly associated with seeking any cancer-related health information. Being younger, female, and having health insurance were significantly associated with information-seeking. Only female sex and education were significantly associated with information-seeking in multivariable analysis. After Bonferroni correction neither variable remained significant.

Table 2.

Bivariate associations and multivariable model of correlates of any cancer-related information-seeking among childhood cancer survivors (N=193)

| Any information resources | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|

| Clinical factors | ||

| Regular source of cancer care (y/n) | 2.75 (1.48–5.11)** | 2.41 (0.98–6.03)+ |

| Regular source of non-cancer care (y/n) | 1.76 (0.96–3.23)+ | 1.02 (0.46–2.26) |

| Cancer follow-up care in past two years (y/n) | 3.18 (1.64–6.18)** | 1.78 (0.72–4.33) |

| Follow-up care discussion with physician (y/n) | 2.33 (1.26–4.27)** | 1.89 (0.93–3.82)+ |

| Treatment intensitya | 1.20 (0.83–1.74) | − |

| Years since diagnosisa | 0.90 (0.76–1.05) | − |

| Psychosocial factors | ||

| Healthcare Self-efficacya | 1.14 (0.92–1.42) | − |

| Post-traumatic growtha | 1.04 (1.01–1.07)** | 1.03 (1.00–1.07)+ |

| Depression symptomsa | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) | − |

| Knowledge of follow-up care (y/n) | 1.51 (0.84–2.73) | − |

| Covariates | ||

| Age group > 21 y (reg group, < 21) | 0.53 (0.29–0.96)* | 0.72 (0.28–1.86) |

| Sex (ref group, male) | 2.12 (1.17–3.86)* | 2.59 (1.22–5.46)* |

| Level of educationa | 1.25 (0.96–1.63)+ | 1.49 (1.01–2.19)* |

| Hispanic ethnicity (ref group, non-Hispanic) | 1.27 (0.70–2.28) | 1.69 (0.78–3.66) |

| Any health insurance (y/n) | 2.60 (1.24–5.44)* | 2.10 (0.75–5.85) |

Continuous variable

P<0.10;

P<0.05;

Significant at P<0.01 (Bonferroni correction)

Hospital-based information resources

In bivariate analyses, having a regular source of cancer care, having cancer follow-up care in the past two years, discussing cancer follow-up care with one’s physician, and greater post-traumatic growth were all significantly associated with seeking information from hospital resources (Table 3). Hispanic ethnicity and having health insurance were also significantly associated with accessing hospital information resources. In multivariable analyses, Hispanic ethnicity and greater post-traumatic growth were significantly associated with accessing cancer-related hospital-based information resources. However, neither remained significant after Bonferroni correction.

Table 3.

Bivariate associations and multivariable models of correlates of cancer-related information-seeking by information domain among childhood cancer sunivors (N=193)

| Hospital resources | Social media/Internet | Other survivors | Family members | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|

| Clinical factors | ||||||||

| Regular source of cancer care (y/n) | 1.95 (1.05–3.66)* | 1.61 (0.65–3.86) | 1.40 (0.75–2.63) | – | 1.48 (0.70–3.12) | – | 3.14 (1.31–7.57)* | 1.61 (0.53–4.91) |

| Regular source of non-cancer care (y/n) | 1.21 (0.66–2.21) | – | 1.80 (0.95–3.41)+ | 1.50 (0.70–3.18) | 1.49 (0.71–3.14) | – | 1.36 (0.64–2.89) | – |

| Cancer follow-up care in past two years (y/n) | 2.98 (1.44–6.17)** | 2.37 (0.90–6.27)+ | 1.76 (0.87–3.55) | – | 4.38 (1.48–12.98)** | 6.38 (1.31–31.18)** | 3.07 (1.13–8.33)* | 1.48 (0.46–4.83) |

| Follow-up care discussion with physician (y/n) | 2.13 (1.16–3.91)* | 1.88 (0.92–3.85) | 1.52 (0.82–2.82) | – | 1.89 (0.89–3.99)+ | 1.66 (0.70–3.93) | 2.45 (1.12–5.38)* | 1.81 (0.77–4. 25) |

| Treatment intensitya | 1.44 (0.99–2.10)+ | 1.32 (0.83–2.09) | 1.03 (0.72–1.48) | – | 1.26 (0.81–1.97) | – | 0.85 (0.54–1.33) | – |

| Years since diagnosisa | 0.97 (0.84–1.12) | – | 0.90 (0.78–1.05) | – | 0.90 (0.76–1.07) | – | 0.93 (0.78–1.11) | – |

| Psychosocial factors | ||||||||

| Healthcare Self-efficacya | 0.99 (0.80–1.23) | – | 1.23 (0.97–1.55)+ | 1.15 (0.88–1.50) | 1.17 (0.89–1.54) | – | 1.35 (1.00–1.82)+ | 1.18 (0.83–1.67) |

| Post-traumatic growtha | 1.01 (0.98–1.07)** | 1.04 (1.01–1.08)* | 1.04 (1.00–1.07)* | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | 1.04 (1.00–1.08)* | 1.06 (1.01–1.11)* | 1.02 (0.98–1.05) | – |

| Depression symptomsa | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | – | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | – | 0.99 (0.95–1.02) | – | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | – |

| Knowledge of follow-up care (y/n) | 0.80 (0.45–1.43) | – | 1.70 (0.92–3.13)* | 1.42 (0.73–2.76) | 2.22 (1.05–4.66)* | 1.81 (0.79–4.15) | 2.02 (0.95–4.26)+ | 1.88 (0.84–4.17) |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Age group > 21 y (reg group, < 21) | 0.60 (0.33–1.08)+ | 0.91 (0.39–2.16) | 0.91 (0.50–1.65) | 1.11 (0.49–2.52) | 0.76 (0.37–1.54) | 0.72 (0.27–1.92) | 0.64 (0.30–1.32) | 0.93 (0.36–2.44) |

| Sex (ref group, male) | 1.11 (0.63–1.97) | 1.17 (0.58–2.37) | 2.41 (1.32–4.40)** | 2.76 (1.39–5.47)** | 1.66 (0.83–3.32) | 1.38 (0.62–3.09) | 0.89 (0.45–1.79) | 0.99 (0.46–2.15) |

| Level of educationa | 1.09 (0.85–1.41) | 1.28 (0.88–1.85) | 1.24 (0.95–1.61) | 1.17 (0.82–1.66) | 1.22 (0.90–1.66) | 1.09 (0.73–1.62) | 1.00 (0.73–1.36) | 0.86 (0.57–1.28) |

| Hispanic (ref group. non-Hispanic) | 2.10 (1.17–3.79)* | 2.52 (1.19–5.30)* | 1.03 (0.56–1.86) | 0.89 (0.41–1.64) | 0.55 (0.28–1.10)+ | 0.45 (0.19–1.06)+ | 0.48 (0.24–0.98)* | 0.50 (0.23–1.09)+ |

| Any health insurance (y/n) | 2.92 (1.25–6.81)* | 1.82 (0.61–5.49) | 1.70 (0.75–3.69) | 1.94 (0.73–5.16) | 0.96 (0.40–2.29) | 0.59 (0.18–1.97) | 2.44 (0.81–7.36) | 1.25 (0.34–4.60) |

Continuous variable

P<0.10;

P<0.05;

Significant at P<0.01 (Bonferroni correction)

Cancer-related social media and internet information resources

In bivariate analyses, greater post-traumatic growth and female sex were significantly associated with accessing cancer-related social media and internet-based information resources (Table 3). In multivariable analyses, only female sex remained significant, and retained significance after Bonferroni correction.

Other survivors as information sources

In bivariate analyses, cancer follow-up care in the past two years and greater knowledge of follow-up care were significantly associated with seeking information from other cancer survivors (Table 3). In multivariable analyses, follow-up care in the past two years and post-traumatic growth remained significant, although the latter association was no longer significant after Bonferroni correction.

Family members as information sources

In bivariate analyses, having a regular source of cancer care, receiving cancer follow-up care in the past two years, and discussing cancer follow-up care with one’s physician were significantly associated with seeking information from other cancer survivors (Table 3). Hispanic CCS were significantly less likely to report seeking cancer-related information from family members than non-Hispanic CCS. In multivariable analysis, none of these associations remained significant.

Discussion

The present study described the prevalence and correlates of health information-seeking among young survivors of childhood cancer. Overall, we found that a majority—60 percent—of CCS accessed any cancer-related information source. Hospital resources were the most commonly accessed source of information for young adult CCS, and Hispanic CCS were significantly more likely to access information from hospital sources than non-Hispanics. We also found a strong relationship between information-seeking from other cancer survivors and engagement in follow-up health care among CCS, and an association between information-seeking and greater post-traumatic growth, an indicator of well-being and adjustment after cancer. In alignment with prior health information-seeking literature, we found that females and individuals with higher levels of education were more likely to seek information from online sources [28, 29]. This gap in utilization of online health information may be narrowing by both gender and educational status due to the rapid proliferation of social networking and smartphone access among this age group [30–32]. However, given the highly correlated nature of ethnicity, SES, and educational attainment, it is possible that this gap may persist for Hispanic CCS [19].

In this sample, hospital resources were the most frequently cited source of information particularly by Hispanic CCS. While information resources may be more readily available at hospitals and clinical sites than other resources, prior research has indicated the key role that health professionals play in addressing the ongoing information needs of cancer survivors [33, 34]. Despite disparities in health care access, perceived poorer care experience, and lower rates of long-term follow-up care among this population [22, 35, 36], CCS of Hispanic ethnicity were significantly more likely than non-Hispanics to seek information from hospital-based resources. Qualitative research has found that older adult Hispanic cancer patients often view health professionals and written material received from physicians as the most credible, and sometimes sole, source of health information [18]. In addition, younger Hispanic cancer patients report forming strong bonds with their doctors and other health care professionals who become a “second family” during treatment [37]. As a result, hospital resource centers and specialized survivorship services (e.g., survivorship clinics) may be particularly important sites of access for cancer-related information for Hispanic CCS and their families, and long-term relationships with trusted health care professionals may be key to addressing the information needs of this population, to the extent that culturally competent and appropriate care is available.

Seeking information from other survivors was strongly associated with follow-up care. CCS who reported follow-up care in past two years were more than six times as likely to report seeking information from other survivors, and more likely to experience post-traumatic growth after their cancer experience. While engagement with medical care may increase the likelihood of connecting with other survivors (e.g., through hospital support groups or from learning about other survivor-focused activities), such interactions may also educate and motivate CCS towards greater engagement with the health care system and retention in follow-up care. Interestingly, treatment intensity (an indirect indicator for greater need for cancer-related follow-up care) was not associated with information-seeking, suggesting that clinicians may need to focus greater attention on unmet information needs among those who receive multiple modalities of treatment and therefore may be at increased risk for late effects.

While we observed that Hispanic CCS may be less likely to access information from family members and other survivors than non-Hispanics, our data indicated only marginal associations. Nevertheless, other studies have drawn attention to issues of stigma regarding cancer-related communication among Hispanic families [38, 39]. Further, young Hispanic cancer survivors report greater unmet social information needs compared to non-Hispanics, and may suffer from a “social information deficit” [40]. Because of the strong association between seeking information from other survivors and follow-up care observed in our data, more research is needed to examine the extent to which CCS of Hispanic ethnicity may experience difficulty in seeking or sharing cancer-related information with families and peer survivors, and to investigate factors related to these potential disparities.

While our study had strengths, with Hispanic CCS comprising more than half of the sample, our data were cross-sectional and thus our findings do not imply causality. Our primary questions about cancer-related health information did not separate active seeking from receipt of information, and these may be different indicators with distinct correlates; future research is required that differentiates these activities within a similar population. In addition, “Hispanic” represents a heterogeneous ethnicity, and our study did not identify Hispanic ethnicity by racial or heritage subgroup. Based on recent census data for Los Angeles County [41], our assumption is that the majority of CCS participating in the study were Mexican-American. However, results may vary by subgroup, and further analysis should take such differences into account. In addition, our comparator group of non-Hispanics, while predominantly composed of non-Hispanic whites, included smaller numbers of individuals from other ethnic and racial groups. Thus results may differ between ethno-racial categories, and further studies should examine such differences with a larger sample to permit subgroup analysis. Finally, our results may be specific to locale (e.g., large regional referral medical centers in a Western urban area) and thus may not generalize outside of similar regions or care settings.

In conclusion, CCS obtain information from a variety of sources, with hospital resources the most frequently accessed, particularly for Hispanic CCS. While information-seeking and sharing may promote positive health care engagement for CCS including greater adherence to recommended follow-up care, Hispanic CCS may be less likely to pursue or have less access to certain information resources such as peer support groups. Additional research is warranted to understand and address the barriers that Hispanic CCS face in information-seeking and sharing.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This paper was supported by the Whittier Foundation and 1R01MD007801 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health. Additional support was provided by P30CA014089 and T32CA009492 from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-0742-3730

Financial disclosures: The authors of this paper report no financial disclosures.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest: Kimberly A. Miller declares that she has no conflict of interest. Cynthia N. Ramirez declares that she has no conflict of interest. Katherine Y. Wojcik declares that she has no conflict of interest. Anamara Ritt-Olson declares that she has no conflict of interest. Lourdes Baezconde-Garbanati declares that she has no conflict of interest. Stefanie M. Thomas declares that she has no conflict of interest. David R. Freyer declares that he has no conflict of interest. Ann S. Hamilton declares that she has no conflict of interest. Joel E. Milam declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Research involving Human Participants and/or Animals: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Hudson MM, Gurney JG, Casillas J, Chen H, et al. Health care of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(1):61–70. doi: 10.1370/afm.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM. Cancer survivors and survivorship research: a reflection on today’s successes and tomorrow’s challenges. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22(2):181–200, v. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nathan PC, Greenberg ML, Ness KK, Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Mahoney MC, et al. Medical care in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4401–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keegan TH, Lichtensztajn DY, Kato I, Kent EE, Wu XC, West MM, et al. Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: a population-based cancer registry study. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(3):239–50. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0219-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox CL, Zhu L, Ojha RP, Li C, Srivastava DK, Riley BB, et al. The unmet emotional, care/support, and informational needs of adult survivors of pediatric malignancies. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(4):743–58. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0520-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gianinazzi ME, Essig S, Rueegg CS, von der Weid NX, Brazzola P, Kuehni CE, et al. Information provision and information needs in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(2):312–8. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knijnenburg SL, Kremer LC, van den Bos C, Braam KI, Jaspers MW. Health information needs of childhood cancer survivors and their family. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54(1):123–7. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeRouen MC, Smith AW, Tao L, Bellizzi KM, Lynch CF, Parsons HM, et al. Cancer-related information needs and cancer’s impact on control over life influence health-related quality of life among adolescents and young adults with cancer. Psychooncology. 2015;24(9):1104–15. doi: 10.1002/pon.3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith AW, Parsons HM, Kent EE, Bellizzi K, Zebrack BJ, Keel G, et al. Unmet Support Service Needs and Health-Related Quality of Life among Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: The AYA HOPE Study. Front Oncol. 2013;3:75. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viswanath K. Science and society: the communications revolution and cancer control. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(10):828–35. doi: 10.1038/nrc1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanch-Hartigan D, Chawla N, Moser RP, Finney Rutten LJ, Hesse BW, Arora NK. Trends in cancer survivors’ experience of patient-centered communication: results from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) J Cancer Surviv. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0550-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagler RH, Romantan A, Kelly BJ, Stevens RS, Gray SW, Hull SJ, et al. How do cancer patients navigate the public information environment? Understanding patterns and motivations for movement among information sources. J Cancer Educ. 2010;25(3):360–70. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0054-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis N, Martinez LS, Freres DR, Schwartz JS, Armstrong K, Gray SW, et al. Seeking cancer-related information from media and family/friends increases fruit and vegetable consumption among cancer patients. Health Commun. 2012;27(4):380–8. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.586990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung M. Determinants of health information-seeking behavior: implications for post-treatment cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(16):6499–504. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.16.6499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shneyderman Y, Rutten LJ, Arheart KL, Byrne MM, Kornfeld J, Schwartz SJ. Health Information Seeking and Cancer Screening Adherence Rates. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31(1):75–83. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0791-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suziedelyte A. How does searching for health information on the Internet affect individuals’ demand for health care services? Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(10):1828–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagler RH, Puleo E, Sprunck-Harrild K, Viswanath K, Emmons KM. Health media use among childhood and young adult cancer survivors who smoke. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(9):2497–507. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2236-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan CP, Napoles A, Davis S, Lopez M, Pasick RJ, Livaudais-Toman J, et al. Latinos and Cancer Information: Perspectives of Patients, Health Professionals and Telephone Cancer Information Specialists. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2016;9(2):154–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee CJ, Ramirez AS, Lewis N, Gray SW, Hornik RC. Looking beyond the Internet: examining socioeconomic inequalities in cancer information seeking among cancer patients. Health Commun. 2012;27(8):806–17. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.647621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson NB, Bulatao RA, Cohen B, National Research Council(U.S.) Critical perspectives on racial and ethnic differences in health in late life. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2004. Panel on Race Ethnicity and Health in Later Life. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richardson A, Allen JA, Xiao H, Vallone D. Effects of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status on health information-seeking, confidence, and trust. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(4):1477–93. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milam JE, Meeske K, Slaughter RI, Sherman-Bien S, Ritt-Olson A, Kuperberg A, et al. Cancer-related follow-up care among Hispanic and non-Hispanic childhood cancer survivors: The Project Forward study. Cancer. 2015;121(4):605–13. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harlan LC, Lynch CF, Keegan TH, Hamilton AS, Wu XC, Kato I, et al. Recruitment and follow-up of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: the AYA HOPE Study. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(3):305–14. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0173-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werba BE, Hobbie W, Kazak AE, Ittenbach RF, Reilly AF, Meadows AT. Classifying the intensity of pediatric cancer treatment protocols: the intensity of treatment rating scale 2.0 (ITR-2) Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(7):673–7. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorig K. Outcome measures for health education and other health care interventions. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cann A, Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, Taku K, Vishnevsky T, Triplett KN, et al. A short form of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2010;23(2):127–37. doi: 10.1080/10615800903094273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;3:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manierre MJ. Gaps in knowledge: tracking and explaining gender differences in health information seeking. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:151–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bass SB, Ruzek SB, Gordon TF, Fleisher L, McKeown-Conn N, Moore D. Relationship of Internet health information use with patient behavior and self-efficacy: experiences of newly diagnosed cancer patients who contact the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Service. J Health Commun. 2006;11(2):219–36. doi: 10.1080/10810730500526794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perales MA, Drake EK, Pemmaraju N, Wood WA. Social Media and the Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Patient with Cancer. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s11899-016-0313-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorence D, Park H. Gender and online health information: a partitioned technology assessment. Health Info Libr J. 2007;24(3):204–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2007.00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith A. 46% of American adults are smartphone owners. Pew Research Center; Washington, D.C: 2012. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Smartphone-Update-2012.aspx. Accessed September 14 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mills ME, Davidson R. Cancer patients’ sources of information: use and quality issues. Psychooncology. 2002;11(5):371–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rutten LJ, Arora NK, Bakos AD, Aziz N, Rowland J. Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: a systematic review of research (1980–2003) Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57(3):250–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Guadagnoli E, Fuchs CS, Yost KJ, Creech CM, et al. Patients’ perceptions of quality of care for colorectal cancer by race, ethnicity, and language. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(27):6576–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmer NR, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Arora NK, Rowland JH, Aziz NM, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in patient-provider communication, quality-of-care ratings, and patient activation among long-term cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(36):4087–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.5060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones BL, Volker DL, Vinajeras Y, Butros L, Fitchpatrick C, Rossetto K. The meaning of surviving cancer for Latino adolescents and emerging young adults. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33(1):74–81. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181b4ab8f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meeske KA, Sherman-Bien S, Hamilton AS, Olson AR, Slaughter R, Kuperberg A, et al. Mental health disparities between Hispanic and non-Hispanic parents of childhood cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(9):1470–7. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casillas J, Kahn KL, Doose M, Landier W, Bhatia S, Hernandez J, et al. Transitioning childhood cancer survivors to adult-centered healthcare: insights from parents, adolescent, and young adult survivors. Psychooncology. 2010;19(9):982–90. doi: 10.1002/pon.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kent EE, Smith AW, Keegan TH, Lynch CF, Wu XC, Hamilton AS, et al. Talking About Cancer and Meeting Peer Survivors: Social Information Needs of Adolescents and Young Adults Diagnosed with Cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2013;2(2):44–52. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2012.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.United States Census Bureau. Hispanic or Latino Origin by Specific Origin. U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey Office; 2013. http://factfinder2.census.gov/ [Google Scholar]