Abstract

Objective

Previous work in pediatric oncology has found that clinicians and parents tend to under-report the frequency and severity of treatment-related symptoms compared to child self-report. As such, there is a need to identify high-quality self-report instruments to be used in pediatric oncology research studies. This study’s objective was to conduct a systematic literature review of existing English language instruments used to measure self-reported symptoms in children and adolescents undergoing cancer treatment.

Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO to identify relevant articles published through November 10, 2016. Using pre-specified inclusion/exclusion criteria, six trained reviewers carefully screened abstracts and full-text articles for eligibility.

Results

There were 7738 non-duplicate articles identified in the literature search. Forty articles met our eligibility criteria, and within these articles, there were 38 self-report English symptom instruments. Most studies evaluated only cross-sectional psychometric properties, such as reliability or validity. Ten studies assessed an instrument’s responsiveness or ability to detect changes in symptoms over time. Eight instruments met our criteria for use in future longitudinal pediatric oncology studies.

Conclusions

This systematic review aids pediatric oncology researchers in identifying and selecting appropriate symptom measures with strong psychometric evidence for their studies. Enhancing the child’s voice in pediatric oncology research studies allows us to better understand the impact of cancer and its treatment on the lives of children.

Keywords: Pediatric oncology, Self-report instruments, Adverse event self-report

Introduction

In 2016, an estimated 10,380 children and adolescents between the ages of 0 and 14 years were diagnosed with cancer in the United States [1]. Each year, approximately 40,000 children undergo cancer treatment [2] and more than 60% participate in a clinical trial [3, 4]. Treatments are associated with high degrees of symptom burden, which have both subtle and visible effects on children. For example, nearly 50% of children experience treatment-related fatigue and 30% experience treatment-related pain, nausea, cough, lack of appetite, and psychological deteriorations [5]. Unpleasant side effects may result in significant decrements in physical, mental, emotional, and social health domains as well as disruptions in primary and secondary education, which are of great concern in this young patient population [6–12].

In the past 20 years in pediatric oncology, there has been an increasing recognition of self-reporting being the gold standard for subjective health status indicators, including symptom burden and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [13, 14]. Objective indicators of symptom burden may not accurately reflect unobservable symptoms that could be better captured by subjective reports of symptom experiences. That is, an objective symptom experience such as a skin ulceration may be more amenable to parent or clinician report, but an unobservable symptom experience such as nausea may be better represented by a child’s own self-report. Several pediatric oncology studies have found that compared to child self-report, clinicians often under-report both the prevalence and severity of subjective treatment-related symptoms experienced by children [15–18]. Studies on the agreement between children and parent proxy symptom reports have found that parents’ scores only agree fairly to moderately with their children’s self-reports with correlations ranging from 0.30 to 0.49 [8, 9, 15, 19–23]. These research findings indicate that clinician or parental proxy reports of cancer treatment burden for the ill child may not accurately reflect views from the child’s perspective [24]. As such, it is imperative for us to better understand the child’s experience in order to provide more patient-centered care in pediatric oncology.

Several self-report symptom instruments have been developed and used in pediatric oncology. However, these instruments differ in important ways including: symptoms assessed, number of questions asked, reference period used, phrasing of questions, and number and type of response options. Differences often reflect the respective study’s target population, with consideration of type of cancer, developmental stage, and/or the chronological age of the children being studied. There is also variation in the type and quality of psychometric evidence supporting existing pediatric self-report instruments. For example, some instruments used in pediatric oncology have not actually been validated in children (only in adults) whereas others have been validated in children, but not those with cancer (Fig. 1).

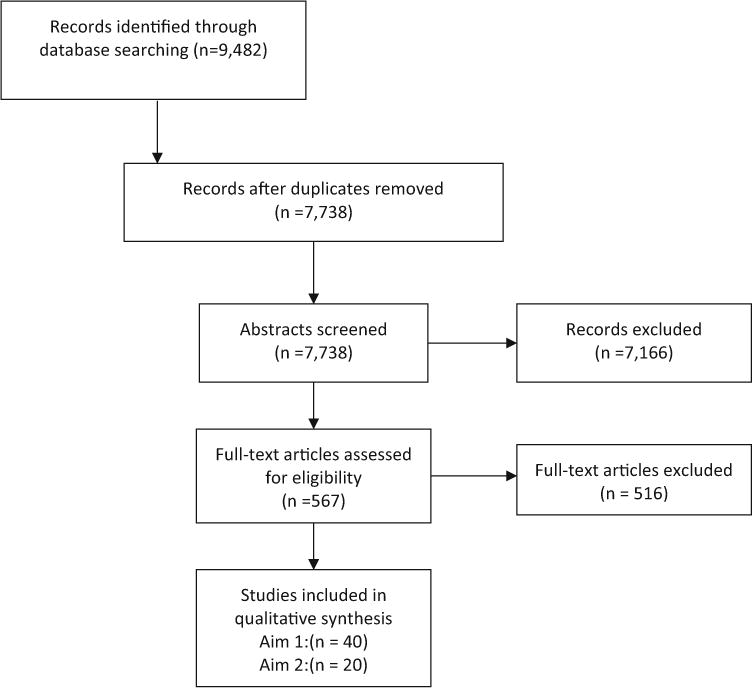

Fig. 1.

PRISMA [25] diagram of studies of pediatric self-report symptom measures in children undergoing active cancer treatment

The objective of the current study was to conduct a systematic literature review to identify and evaluate available English language instruments for measuring self-reported symptoms in children and adolescents undergoing cancer treatment. We evaluated the evidence regarding the psychometric properties of each identified instrument, whether or not the evidence derived was from cross-sectional or longitudinal evaluations, and if the instrument was used in a clinical trial. Based on the evidence, we offer recommendations regarding which self-report instruments are ready for use in pediatric oncology research. Findings from our comprehensive systematic review will help inform longitudinal studies, comparative effectiveness research studies, patient-centered outcomes research studies, and clinical trials that are interested in using self-report symptom instruments in pediatric oncology.

Methods

Literature search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO, to identify relevant articles from each database’s inception through November 10, 2016. The literature search included Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), Emtree headings, and related text and keyword searches when appropriate, focusing on terms used to describe self-reported symptom measurements in children and adolescents with cancer (Appendix A).

The study’s search strategy was developed with input from members of the research team, and an experienced librarian who conducted the searches. Details of the search strategy are presented in Appendix A.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Criteria for inclusion of studies were: (1) only empirical studies with children and adolescent self-report instruments; (2) in the English language; (3) designed or evaluated in children or adolescents with cancer less than 21 years of age; (4) focused on measuring symptoms and either reported scores for symptoms individually or in aggregate form (e.g., overall toxicity or symptom burden score); (5) reporting results for participants that were on treatment separately from those who were off treatment, as we were specifically interested in children currently on treatment; and (6) reporting psychometric evidence for the instrument in at least one publication in a pediatric cancer population. Psychometric evidence included cross-sectional or longitudinal studies that assessed reliability (internal consistency, test—retest) and validity (content, construct, responsiveness) of the self-report instrument. Studies that only correlated child assessments with parent/proxy assessments, but did not evaluate other psychometric properties did not meet our criteria for psychometric evaluation.

HRQOL instruments were eligible if they also measured symptoms and reported scores for symptoms (individually or aggregated), but not if HRQOL scores were summarized as an overall HRQOL or well-being score. Studies were excluded if instruments only reported parent or clinician proxy measures.

Data abstraction: cross-sectional psychometric properties

Two trained members of the study team evaluated each eligible study’s design (e.g., cross-sectional or longitudinal), inclusion/exclusion criteria of the study sample (e.g., English speaking/reading only), participant characteristics (e.g., sample size, mean age, percent female, cancer types included), reliability of each measure (e.g., internal consistency and test—retest), and how validity was assessed (e.g., content, construct). In particular, an instrument’s validity had to be assessed using an instrument that has been validated in a pediatric oncology population. Two senior members of the study team assessed all data abstraction for quality control and consistency. The psychometric properties of the eligible instruments are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Studies that evaluated psychometric properties of pediatric self-report symptom measures in cancer research

| Instrument being validated | Cancer Type (treatment type, inclusion/exclusion criteria) | Child Age (mean, range); | Sample Size; % female | Measure Reliability: internal consistency (α), test-retest (rt−r) | Measure Validity: content, construct |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Sleep Wake Scale (ASWS) [33] | Acute lymphocytic leukemia (41%), acute myelogenous leukemia (4%), Hodgkin lymphoma (8%), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (8%), bone tumor (15%), brain tumor (12%), other (12%) | 14.2 (10–19) years | N = 51, 43% female | Full ASWS α = 0.83. Subscales α ranges (0.66–0.78) | Known groups validity: Adolescents on chemotherapy (CTX) reported significantly lower ASWS scores than healthy adolescents (p < 0.01) Adolescents on CTX reported higher ASWS scores than those with chronic pain (p < 0.01) |

| Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ) [34] | Acute lymphocytic leukemia (44.3%), Hodgkin’s lymphoma (11.4%), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (4.3%), Wilms tumor (5.7%), Acute myeloid leukemia (5.7%), medulloblastoma (2.9%). Ewing’s tumor(4.3%), rhabdomyoscaroma (2.9%), other (18.5%), 66% off treatment, treatment: chemo, radiation (when necessary), bone marrow transplant (leukemia) | 13.6 (10–18) years | N = 70, 47% female | Not assessed. | Known groups validity: Comparison between on treatment and off treatment for CHQ, the subscales of General Health Perceptions, Role/Social-Behavior, Self-Esteem, and Mental Health were significant (p < 0.05). Concurrent validity: There was significant correlation between parent report and child report with time since diagnosis for Physical Functioning, Role/Social-Physical, and General Health Perceptions |

| Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ) [22] | On active tx: 31% ALL, 8.5% other leukemia, 14.1% HD/NHL, 29.6% solid tumor, 16.9% brain tumor | 11.7 (7–18) years | N = 71, % female not reported | Not assessed | Known groups validity: On-treatment group reported worst HRQOL than off-treatment and control group (best HRQOL) on 7 of the 10 subscales. The on- and off-treatment groups did not differ from each other in the role/social limitations-physical scale and the general health perceptions subscales Concurrent validity Moderate significant (p ≤ 0.05) correlations between the child and parent reports on 10 HRQL scales for active tx group (range 0.344–0.592) |

| Childhood Cancer Stressors Inventory (CCSI) [35] | 64% leukemia/lymphoma, 36% solid tumor | Mean not reported (7–13 years) | N = 75, 45% female | CCSI α = 0.82; Intensity subscale α = 0.83 | Content validity: 5 pediatric oncology nurses reviewed the instrument and rated the items relevant, and the wording understandable. Children age 7–13 evaluated readability of the instrument Concurrent validity: The number of school days missed correlated with the frequency of perceived stressors (r = 0.34, p < 0.01) and the intensity of stressors (r = 0.23, p = 0.03) |

| Children’s Depression (CDI) [36] | Children on active treatment who did not have CNS and were not enrolled in full-time special education. Leukemia, lymphomas and solid tumors | 11.5 (8–15) years | N =70,% female not reported | Not assessed | Known groups validity: No significant differences found between cancer and non-cancer group in CDI score (7.42 in both with p = 0.99) |

| Children’s International Mucositis Evaluation Scale (ChIMES) [37] | n = 36 leukemia/lymphoma, n = 38 solid tumor, n = 7 brain tumor, n = 6 other | 12.2 (8–18) years | N = 87, 37% female | Test-retest reliability of the total score is rt−r = 0.854 (p < 0.01) and percentage score rt−r = 0.852 (p < 0.01) for all children age 12–18 years old; Total score for all children 8–12 rt−r = 0.902 (p < 0.01) and percentage score rt−r = 0.902 (p < 0.01) | Convergent validity: ChIMES correlated with WHO Mucositis, VAS Mucositis, CTCAE grading of Mucositis, and Oral Mucositis Daily Questionnaire (OMDQ) items. For ages 12–18 correlation for ChIMES total score ranged from 0.585 to 0.904 (p < 0.01 for all), percentage score r = 0.587 to 0.905 (p < 0.01 for all). For ages 8 to <12 ChIMES total score ranged from 0.551 to 0.928 (p < 0.01 for all), percentage score r = 0.549 to 0.926 (p < 0.01 for all) Responsiveness: see Table 3 |

| Children’s International Mucositis Evaluation Scale (ChIMES) [38] | All children were receiving or had received chemotherapy for cancer, including HSCT | 12.5 (8–18) years | N = 82, % female not reported | Not assessed | Content validity: Cognitive interviews with children and parents. ChIMES mostly rated as “very easy” or “easy” to understand. Most rated the overall instrument as “good” or “okay” |

| Children’s International Mucositis Evaluation Scale (ChIMES) [39] | First phase: Leukemia/lymphoma (80%), Solid tumor (10%), Brain tumor (10%) Second phase: Leukemia/lymphoma (47.5%), Solid tumor (45%), Brain tumor (7.5%) |

Phase 1: median: 15.3 (9.2–17.7) years Phase 2: median: 12.4 (8.0–17.8) years |

Phase 1 N = 10, 40% female Phase 2 N = 40, 70% female |

Not assessed | Content validity: Cognitive interviews for first phase (instructions) and second phase (use, understandability, and suitability). Overall found that the instrument was easy to use, easy to understand and suitable to assess mucositis |

| Constipation Assessment Scale (CAS) [40]—modified version for children | Ewing’s sarcoma (38.1%) Rhabdomyosarcoma (23.8%) Osteosarcoma (14.3%) Acute lymphocytic leukemia (4.8%) Ependymoma (4.8%) Lymphoma/leukemia (4.8%) Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (4.8%) Stomach (4.8%) |

15.7 (9–21) years | N = 21, 52% female |

rt−r = 0.93, p < .01 CAS α range (0.60–0.79) during weeks 1 & week 2. CAS α range (0.28–0.82) in weeks 3–5 |

Known groups validity: Significant difference in mean CAS scores (t = 4.4, p < .01) for subjects designated as not constipated (2.83; SD, ±1.9) versus constipated (7.80; SD, ±2.6) Concurrent validity: CAS was associated with constipation noted in the medical record and the physical examination |

| Fatigue Scale-Children (FS-C); Fatigue Scale-Adolescents (FS-A) [41] | Solid tumors (86%) and AML (14%). | 12.5 (7–18) years | N = 29, 59% female | FS-C α range (0.64–0.72). FS-A α range (0.76–0.96) | Known groups validity: FS-C and FS-A scores did not differ significantly between the experimental and standard care arms Responsiveness: see Table 3 |

| Fatigue Scale-Adolescents (FS-A) [42] | Leukemia, Lymphoma, ALL (60.9%) | 15.3 (13–18) years | Focus groups: N = 15, 67% female Quantitative study: N = 64, 44% female |

α range (0.67–0.95) across 4 studies | Content validity: Individual and focus group interviews to learn about the fatigue experience, and expert panel review with health care professionals and adolescents with cancer Known groups validity: Anemic patients had significantly higher fatigue than non-anemic patients, but article only cites parent report here, (p = 0.04) Concurrent validity: Adolescent scores were significantly correlated with parent scores on 2 out of 4 studies and then when aggregating study data Responsiveness: see Table 3 |

| Fatigue Scale-Children (FS-C) [43] | Leukemia (67.9%), Lymphoma (7.2%), Brain tumor (4.1%) Solid tumor (19.9%) |

9.2 (6.6–13) years | Study 1 N = 53, 42% female. Study 2 N = 150, 44% female. Study 3 N = 18, 78% female | 10-item FS-C α = 0.76, 14-item FS-C α = 0.81 | Structural validity Factor analysis showed good fit: CFI = 0.94 (>0.90 threshold), RMSEA = 0.028 (<0.05 threshold). Concurrent validity; FS-C correlated with FS-P (parent) responses (r = 0.44, p < .01) |

| Revised 13-item Fatigue Scale- Adolescents (FS-A) [44] | 37.68% ALL, 2.89% AML, 37.68% HL/lymphoma, 18.1% solid tumor, 3.62% germ cell tumor | 15.5 (12.7–18.8) years | N = 138, 44% female | 13-item α = 0.87, 14-item α = 0.86 | Structural validity: Confirmatory factor analysis yielded reasonable fit of 4 factors; goodness-of- fit index 0.8551; Root Mean Square residual (RMSR) = 0.08 Concurrent validity: Spearman correlation in the subset of 75 patient and parent dyads was 0.347 (p < .01) |

| Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) (10–18) [5] | Leukemia, lymphoma, other solid tumor, CNS tumor, rare malignancies of childhood | 14 (10–18.2) years | N = 159, 42% female | α ranged from 0.83–0.87 Test-retest: 26 of 30 symptoms had significant correlation | Content validity: Experts in developmental pediatrics and pain management modified the adult version of the instrument. Then instrument was run through the readability tests in MS Word (SMOG, FRY). Finally, the modified instrument was pilot-tested in 10 patients around 10 years old Convergent validity: MSAS correlated with Memorial Pain Assessment Card-pediatric (MPAC-ped), and Investigator-created, face-valid VAS to assess domains of nausea, global physical, global psychological. There was strong agreement between children and parents for 24 of 30 symptoms Known groups validity: Higher symptom number and distress among inpatients than outpatients. Significant differences between recent treatment (2 weeks–1 month) vs. off-treatment (>4 months) groups for MSAS total and all sub scores except the psychological subscale |

| Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) (7–12) [19] | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, CNS tumor, Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Rhabdomyosarcoma, Wilms’ tumor, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Acute myelogenous leukemia, Neuroblastoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, Hepatoblastoma, Osteosarcoma | 9.6 (7–12) years | N = 149, 47% female | rt−r = 0.67 | Content validity: Creation of MSAS (7–12) based on data from the MSAS (10–18) study. Instrument ran through the readability tests in MS Word (SMOG, FRY) Convergent validity: Investigator-created, face-valid VAS to assess domains of pain, nausea, sadness, and body showed significant correlations ranging from 0.70–0.76 (p < 0.01). Higher MSAS symptom number and distress among inpatients than outpatients. Fair to moderate agreement between children and parents: nausea (k = 0.46), pain (k = 0.46), and lethargy (k = 0.42). Fair agreement for anorexia (k = 0.35), sadness (k = 0.33), and insomnia (k = 0.20). Poor agreement for itch (k = 0.11) and worry (k = 0.16) |

| Minneapolis-Manchester Quality of Life-Adolescent Form (MMQL-AF)* [45] | ALL, AML, Hodgkin’s, Non-Hodgkin’s, Brain tumors, Wilm’s tumor, Neuroblastoma, Rhabdomyosarcoma, Osteosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, Hepatoblastoma, Other cancer | 16.7 (13–20.9) years | N = 110, 45% female | Overall rt−r = 0.71. Subscale rt−r ranged from 0.60–0.90. Overall α = 0.92, subscale α ranges (0.67–0.89) |

Content validity Focus group of 20 individuals including, patients, parents, nurses, doctors. Then 20 individual “open interviews” with survivors conducted to identify domains. Two rounds of cognitive interviews each with 10 adolescent survivors of cancer Known groups validity: Significant differences between 3 groups (children with cancer, both on and off treatment, and those without cancer): Physical, Cognitive, Psychological factors. But MMQL-AF could not discriminate between 3 groups for body image, intimate relationships, outlook on life domains |

| Minneapolis-Manchester Quality of Life-Adolescent Form (MMQL-AF)* [46] | Leukemia (44%), Lymphoma (19%), Brain tumors (4%), other solid tumors (33%). | 15.4 (5.3–20.0) years | N = 136, 40% female | Not assessed | Known groups validity: Scores for those on treatment (3.77), survivor (3.96) and healthy controls (4.05) were significantly different (p

< .01). On-therapy patients were at increased risk for poor QOL (defined at a score below the 25th percentile): OR 3.3, p < 0.01. On-therapy patients were at increased risk for poor physical functioning OR 11.8, p<. 01 |

| Minneapolis-Manchester Quality of Life-Youth Form (MMQL-YF)* [47] | Leukemia, Lymphoma, Brain Tumors, Other solid tumors (on-treatment sample must be patients actively undergoing treatment for cancer for at least 2 months) | 10.2 (8–12) years | N = 72, 42% female | rt−r ranged from 0.56–0.79 (p < 0.05). Overall α = 0.85, subscales α range (0.72–0.80) | Content validity: Focus group of 10 survivors to identify concerns. Then “open interviews” were conducted with 20 survivors to identify questions to include in the questionnaire. Two rounds of cognitive interviews each with 20 survivors Known groups validity: MMQL-YF was able to distinguish between 3 groups, but On-treatment patients had the best scores of all three groups (when they were expected to have the worst) for Physical Symptoms and Psychological Functioning domains Convergent validity: MMQL-YF had some moderate, significant correlations when compared with Child Health Questionnaire-87 (compared across multiple sub-domains) |

| Minneapolis-Manchester Quality of Life-Youth Form (MMQL-YF)* [48] | Children 8–12 actively undergoing treatment for cancer for at least 2 months. Leukemia (64%), lymphoma (6%), brain tumors (8%), other solid tumors (22%) | 9.1 (1.9–12.5) y | N = 76, 42% female | Not assessed | Known groups validity: Children on treatment had lower MMQL-YF scores than healthy controls (p = 0.01). Children on therapy also had lower physical functioning (p = 0.01) and outlook on life (p < 0.01) |

| Oral Mucositis Daily Questionnaire (OMDQ) [49] | Children undergoing induction or consolidation chemotherapy for AML, relapsed ALL, or advanced lymphoma or receiving myeloablative SCT (87% of children in this study diagnosed with Leukemia/Lymphoma) | Median: 16.7 (12–18) years | N = 15, 47% female | All questions, but diarrhea exhibited very good correlation (rt−r > .80). Diarrhea question rt−r = 0.73 | Convergent validity: OMDQ had strong to moderate significant correlations with WHO mucositis scale, a mucositis VAS, and the oral component of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Esophageal Cancer Subscale (FACT-ECS) on questions about pain (0.90, 0.81, −0.62–0.77), swallow (0.65, 0.67, −0.60–0.71), drink (0.73, 0.57, −0.65–0.77) and eat (0.83, 0.470.82–0.85) Sleep and talk questions had fair correlations with WHO, VAS mucositis and FACT-ECS (between 0.35–0.59; −0.35–0.59). The diarrhea question had poor correlations ranging from 0.04–0.16 |

| Oral Mucositis Daily Questionnaire (OMDQ) [50] | Diagnosis not discussed, 100% received chemotherapy | 15 (13–17) years | N = 6, 17% female | Not assessed | Content validity: Cognitive interviews: 5 out of 6 children rated the first and third questions very easy to understand, 2 out of 6 rated the second question very easy to understand. Children found this instrument easy to use overall |

| Pain Squad App [51] | Study 1: ALL (45%), AML (9%), Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (9%), Sarcomas (16%), CNS tumors (8%), Other (13%) | Study 1: 13.1 (8–18) years | Study 1: N = 92, 49% female Study 2: N = 14, 50% female |

α = 0.96 | Discriminant Validity: PedsQL Generic Module had weak to moderate, significant correlations (p < 0.01) with Pain Squad app weekly pain indices’ scores for intensity (r = −0.3), unpleasantness (r = − 0.38), interference (r = −0.46). But no significant correlations with PedsQL Cancer Module Responsiveness: see Table 3 |

| Pediatric Advanced Care Quality of Life Scale (PAC-Qol) [52] | Doesn’t specify (only says “malignancy”) | 12.6 (9–17) years | N = 28, 64% female | Not assessed | Content validity: Cognitive interviews demonstrated that the scale was easy to understand and self-report |

| Pediatric Cancer Quality of Life Inventory (PCQL-32) [53] | Cancer type not specified. Included on and off treatment. Excluded: Non-English speaking, comorbid disease, and major development disorders | 11.8 (8–18) years | N = 281, % female not reported | Core form α = 0.83, Subscales: Pain α = 0.83, Nausea α = 0.71. | Known groups validity: Mean scores for on vs off treatment. Core: 50.8 vs. 49.4 (p = 0.03). Pain: 51.2 vs. 49.1 (p = 0.02). Nausea: 52.3 vs. 48.2 (p < 0.01)Concurrent validity: Significant correlations for the core and nausea scales with number of days missed from school |

| Pediatric Cancer Quality of Life Inventory (PCQL-32) [54] | Acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelogenous leukemia, other leukemias, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, brain tumor, Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, retinoblastoma, hepatoma | 11.8 (8–18) years | N = 291, 35% female | Overall α = 0.91, Subscales: Symptoms/Problems, α = 0.83, Physical Functioning α = 0.78, Psychological α = 0.76, Social α = 0.69, Cognitive α = 0.81. |

Known groups validity: On-treatment had significantly worse health/symptom scores than off-treatment groups for instrument as a whole, as well as Disease/Treatment Symptoms and Physical Functioning, and Psychological Functioning subscales Convergent Validity; Moderate correlations (p < 0.05) between instrument with Children’s Depression Inventory-32 (CDI), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-32 (STAIC), Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC) and Adolescents (SPPA) |

| Pediatric-Functional Assessment of Anorexia and Cachexia Therapy (Peds-FAACT) [55] |

Leukemia (43%), brain/spinal cord tumor (26%). | 11.3 (7–17) years | N = 96, 50% female | For adolescents (12–17): α = 0.80 For children (7–11): α = 0.47 10-item version α = 0.83 for children 10 years and older |

Convergent validity: 6-item & 10-item peds-FAACT correlated (r =.51, r = .46) with the PedsQL Cancer module Nausea subscale. Known groups validity: 6-item peds-FAACT statistically differentiated Patients from 2 functional performance groups (Lansky and Kamofsky) (p < 0.05). But, no significant difference found between patients with acceptable BMI and patients who were either underweight or overweight (p = 0.87) Structural validity: Scale unidimensionality confirmed by factor analysis |

| Pediatric Nausea Assessment Tool (PeNAT) [56] | Diagnosis not described, but children were divided into two groups-2 groups receiving chemotherapy, and 2 not receiving chemotherapy (Exclusion criteria: children who were developmentally delayed, non-English speaking) | 10.3 (4–17.8) years | N =177, 39% female | Test–retest (1 h in-between assessment): rt−r = 0.649, p < 0.01 | Content validity: PeNAT reviewed by clinicians, parents. Feasibility testing in 15 children receiving chemo followed by interviews (for adolescents ≥16) on understanding instructions and ease of administration (but not understanding of construct) Convergent validity: First PeNAT score and number of emetic episodes (Spearman ρ = 0.322, p = 0.12); First PeNAT score and dietary intake (Spearman ρ = −0.217, p = 0.096) Known groups validity: Children undergoing HSCT higher median scores than children with cancer not receiving chemo (p < .01). HSCT group significantly higher when compared with general pediatrics (p = 0.04). Concurrent validity: Moderate correlation observed between children’s PeNAT scores and the parents’ assessment of their child’s nausea (Spearman’s ρ = 0.442, p < 0.0001) |

| Pediatric Oncology Quality of Life Scale (POQOLS), Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI), Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) [57] |

Leukemia (39%), brain tumor (6%), Hodgkin’s disease (28%) and other types of cancer (27%). | 13.7 (8–19) years | N = 19, % female not reported | POQOLS α = 0.83, CDI α = 0.81, RCMAS α = 0.30, symptom checklist α = 0.86 | Concurrent validity: Children’s scores on POQOL were positively and significantly correlated with parents’ scores |

| Pediatric Patient-Reported Outcomes Version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (Pediatric PRO-CTCAE) [58] | Round 1: Leukemia (49%), Lymphoma (18%), Sarcoma (18%), Other solid tumor (13%), Brain (2%) Round 2: Leukemia (50%), Lymphoma (19%), Sarcoma (28%), Other solid tumor (3%) |

Round 1: Mean not reported (7–12 years) Round 2: Mean not reported (7–15 years) | Round 1: N = 45, 58% female Round 2: N = 36, 42% female |

Not assessed | Content validity: Two rounds of cognitive interviews with children/adolescents on active treatment and their caregivers. Assessed symptom AE terms, question structure, response options, and recall period. Overall instrument performed well and found to be easy to complete |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-4.0 Generic Score (PedsQL) Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-Cancer Module State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) Faces Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R) [59] |

51% leukemia, 17% CNS tumor, 17% sarcoma, 10% lymphoma, 5% other (germ cell, Wilms) | 8.6 (4–17) years | N = 45; 38% female | Not assessed | Known groups validity: Children who received medication (compared with those not on medication) reported lower QOL as measured by the PedsQL Cancer Module (p = 0.02) and lower general HRQOL as measured by the PedsQL (p = 0.01) and greater pain severity as measured by FPS-R (p < 0.01) |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-4.0 Generic Score (PedsQL) [60] | Solid tumors, Hodgkin’s disease, ALL, and NHL | 11.6 (5–18) years | N = 222, 46% female | Physical α = 0.90, Emotional α = 0.84, Social α = 0.71, School α = 0.82 rt−r ranged 0.53–0.67 |

Concurrent validity: Agreement between child and parents ranged from 0.61 (social function) to 0.86 (physical function) |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-4.0 Generic Core (PedsQL) [61] | Intracranial tumors. Children alive at one year after diagnosis were included in analyses | Median 9.4 (1.8–16.6) years | N = 26, % female not reported | Not assessed | Known groups validity: at T1 there was significant difference between patients and controls for all summary scores (p = 0.03), but not emotional/social domains (p = 0.12). At T6, total score and summary scores were significantly different between patients and controls (p = 0.03). At T12, only the physical summary score was significantly different between the two groups (p = 0.02) Concurrent validity: at T1, child/parent agreement was 0.65 to 0.79. At T6, parent/child agreement ranged from 0.53 to 0.86. At T12, parent/child agreement ranged from 0.66 to 0.87 Responsiveness: see Table 3 |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-4.0 Generic Core (PedsQL); Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-Cancer Module [62] |

Solid tumor, Hodgkin’s disease, Acute lymphocytic leukemia, Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 11.6 (5–18) years | N = 222, 45% female | Not assessed | Known groups validity: Mean PedsQL scores between EPO and placebo were not significant (p = 0.76) Concurrent validity: For the general score, child/parents agreement ranged from 0.59 to 0.77 (p < 0.01) and for the cancer module it ranged from 0.34 to 0.59 (p < 0.01). Correlation between changes in hemoglobin and PedsQL-GCS (r = 0.15, p = 0.03) Responsiveness: see Table 3 |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-4.0 Generic Core (PedsQL): Acute version, Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-Multidimensional Fatigue Scale: Acute version, Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-Cancer Module: Acute version [63] |

Children with ALL (50%), Brain tumor (7%), NHL (6%), HL (3%), Wilm’s tumor (6%), other cancers (28%) | 10.9 (8–18) years | N = 222, 44% female | Total PedsQL α = 0.88. Subscales: Physical health α = 0.81, Psychosocial health α = 0.83, Emotional health α = 0.73, Social functioning α = 0.70 PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Total fatigue α = 0.89. Subscales: General fatigue α = 0.77, Sleep/rest fatigue α = 0.78, Cognitive fatigue α = 0.83 PedsQL 3.0 Cancer Module overall: α = 0.72, Pain and hurt: α = 0.70, Nausea α = 0.79, Procedural anxiety α = 0.82, Treatment anxiety α = 0.79, Worry α = 0.74, Cognitive problems α = 0.76, Perceived physical appearance α = 0.49, Communication α = 0.66 |

Known groups validity: For PedsQL Oncology Sample reported worse HRQOL than the Healthy Sample (p < 0.01). For PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, the Oncology Sample reported worse fatigue than the Healthy Sample (p < 0.05); For PedsQL 3.0 Cancer Module, children on treatment reported worse Nausea, Treatment Anxiety, Worry compared to children off treatment (>12 months) Convergent validity: Examined through an analysis of the inter-correlations among the PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Total Scale score with the PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Total Score and the PedsQL Cancer Module Scales show medium effect size |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-Cancer Module; Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-Multidimensional Fatigue Scale [64] |

Not reported | 15.6 (13–19) years | N = 102, 49% female | Not assessed | Discriminant validity: Correlation between pain and fatigue is 0.62 (p < 0.01), pain and nausea is 0.33 (p < 0.01), fatigue and nausea is 0.47 (p < 0.01) |

| PROMIS Pediatric Measures: Physical Functioning—Mobility, Physical Functioning—Upper Extremity, Pain Interference, Fatigue, Depressive Symptoms Anxiety, Peer Relationships, and Anger [31] | Currently receiving curative cancer treatment (60% were diagnosed with leukemia or lymphoma) | 12.5 (8–17) years | N = 200, 45% | Not assessed | Known group validity: Active treatment vs. survivorship compared across 8 domains (Depression, Anxiety, Anger, Peer Relationships, Pain interference, Fatigue, Upper extremity, Mobility): Children in active tx group had statistically significantly lower (worse) mean scores compared to survivors in all categories except anger |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) [65] | Cancer group: ALL (25.4%), other Leukemia (6.9%), HD/NHL (28.5%), Solid Tumor (30.0%), Brain tumor (9.2%) | 13.1 (7–18) years | N = 130, 41% female | Not assessed | Known groups validity Cancer group had the lowest anxiety score (34.3) compared to chronically ill (35.1) and control (37.0). F(2597) = 8.0, p < .01 |

| Symptom Distress Scale (SDS), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) [66] | Leukemia (64%) and Hodgkin’s Disease (36%). | Mean not reported (10–17) years | N = 11, 45% female | SDS α = 0.85, STAIC-1 α = 0.86 | Responsiveness: see Table 3 |

| Symptom Screening in Pediatrics Tool (SSPedi) [67] | Included children under active treatment. Excluded those who were severely ill, had cognitive disabilities or visual impairment | Mean not reported (8–18) years | N = 30, 33% female | Not assessed | Content validity Cognitive interviews found the SSPedi was easy to complete and understandable among children undergoing active treatment for cancer |

| 10-cm Self-Report Visual Analog Scale (VAS) Nausea 10-cm Self-Report Visual Analog Scale (VAS) Anxiety [68] |

Leukemia (40%), lymphoma (27%), brain tumor (7%), sarcoma (27%). | 12.7 (9–18) years; | N = 15, 27% female | Not assessed | Known groups validity: To assess nausea VAS: compared children on antiemetics reported more nausea than children with no antiemetics. Assessing nausea and anxiety VAS: compared to clinical anchors (pulse rate, systolic, and diastolic blood pressure, antiemetic v. no antiemetic) comparison with significance: systolic blood pressure increased significantly (m = 104.80) from previous intervention level (m = 98.27) Responsiveness: see Table 3 |

Intended use with cancer survivors

VAS Visual Analog Scale

Data abstraction: longitudinal psychometric properties

Two members of the study team further evaluated studies that were deemed eligible for the psychometric property assessment to determine whether they also assessed the pediatric self-report instrument’s responsiveness or ability to detect changes over time. Eligible studies included ones that performed a psychometric evaluation of responsiveness or studies that simply collected and reported change scores for the instrument at two time points. Longitudinal study attributes including study design (e.g., observational, randomized control trial), participant characteristics (e.g., cancer types, mean age, sample size, percent female), and conclusions regarding the instrument’s responsiveness are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Longitudinal studies providing evidence for the responsiveness of the pediatric symptom measures

| Instrument validated | Cancer type (treatment type, inclusion/exclusion criteria) | Child age (mean, range); | Sample size; % female | Responsiveness | Number and timing of assessments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) [69] | Children with Leukemia (41%) or solid tumors (59%). Exclusion criteria included patients with progressive disease, individuals diagnosed <2 weeks ago, and those in the intensive care unit | Median: 12.9 (8–16.8) years | N = 99, 39% female | At T1: median CDI for children was 6.0 and 3.5 at T2 (p < 0.01). The 23-item version of the CDI had a median of 4.0 at time 1 and 3.5 at time 2 (p < 0.01). Both the CDI and CDI-23 should statistically significant decline from T1 to T2 | Two time points T1: At study enrollment and T2: 4–6 weeks after |

| Children’s International Mucositis Evaluation Scale (ChIMES) [37] |

n = 36 Leukemia/Lymphoma, n = 38 Solid tumor, n = 7 Brain tumor, n = 6 Other |

Median: 14.7 (8–18) years | N = 87, 37% female | Among children who reported mucositis on the 14th day, Children ages 12–18 years: at baseline reported 0.9 and at 14 days reported 10.6 (p < 0.01), Children ages 8–12 years: at baseline reported 0.9 and at 14 days reported 12.6 (p = 0.06). Overall, the CHIMES showed significant increases in mucositis between baseline and day 14 | 14 time points T1: baseline is 2–5 days and then again daily for days 7–17 |

| Fatigue Scale-Adolescent (FS-A) [42] | ALL (60.9%), AML (4.7%), HD/lymphoma (9.3%), Solid tumor (25%) |

15.3 (13–18) years | N = 64, 44% female | Combined scores across 4 studies. FS-A scores increased significantly between T1 and T2 (p = 0.01) | Two time points. MFCC study, T1: first day of re-induction, T2: end of re-induction. SLEEP study, T1: 2nd day of the first 5-day period, T2: 2nd day of the second 5-day period. SLEEP2 study, T1: date of admission to hospital, T2: 3rd day of hospitalization. CLUSTERS study, T1: 1st day of chemotherapy, T2: week after final dose of chemotherapy. |

| Fatigue Scale-Adolescents (FS-A), Fatigue Scale-Children (FS-C) [41] |

Solid tumors (86%) and AML (14%). Eligibility: 7–18 years, inpatient, able to understand English, and able to give assent. Children with CNS tumors, being treated for recurrent disease, scheduled for rehab due to amputated limb, and those experiencing uncontrolled pain (>3 on a 5-point scale) were ineligible for the study. | 12.5 (7–18) years | N = 29, 59% female | FS-C and FS-A scores did not vary significantly over time (F = 0.50, p = 0.61) | Four time points T1: Date of hospital admission and fatigue was collected the following three days (T2, T3, and T4) |

| Fatigue Scale-Adolescents (FS-A), Fatigue Scale-Children (FS-C) [70] |

ALL (low risk, standard risk (63%)); 50 weeks after diagnosis (on continuation therapy) | 9.2 (5–18) years | N = 100, 38% female | Children ages 7–12 years completing the FS-C reported significantly more fatigue during the on-dex period than during the off-dex period (p < 0.01) Findings were similar for adolescents ages 13–18 completing the FS-A (p < 0.01) | Four time points (2 consecutive 5-day periods). T1 (day 2) and T2 (day 5): Patients not taking dexamethasone. T3 (day 7) and T4 (day 10): Patients taking dexamethasone |

| Fatigue Scale-Adolescents (FS-A), Fatigue Scale-Children (FS-C) [71] |

Solid tumor (86%), acute myeloid leukemia (14%) | 12.5 (7.4–18.2) years | N = 29, 59% female | Mean FS-C was 16.59 at T1, 22.69 at T2, 23.22 at T3, and 23.33 at T4. Mean FS-A was 25 at T1, 31.67 at T2, 33.78 at T3, and 37 at T4. Authors do not present whether this was a statistically significant change over time | Four time points T1: Date of admission, fatigue was collected for the following 3 days (T2, T3, and T4) |

| Fatigue Scale-Adolescents (FS-A), Fatigue Scale-Children (FS-C) [72] |

ALL (6 children, 3 adolescents); AML (1 adolescent); lymphoma (5 children, 7 adolescents); solid tumor (5 children, 3 adolescents). Newly diagnosed within 3 cycles of chemo | No mean (6–18 years) | N = 30, 30% female | FS-C at T1: 18 and at T2: 10.5 (p = 0.05) and FS-A at T1: 23.5 and at T3: 20.5 (p = 0.15). Using the FS-C, fatigue significantly decreased from cycle 1 to 3, but there was no significant change using the FS-A | Two time points T1: first cycle of chemotherapy between days 15–29 of the cycle, T2: third cycle of chemotherapy between days 15–29 of the cycle |

| Fatigue Scale-Adolescents (FS-A), Fatigue Scale-Children (FS-C) [73] |

Solid tumor (59%), Lymphoma (41%) | No mean (7–18 years) | N = 45, 35% female | CFS showed significant decreases in overall fatigue among children 7–12 years (p = 0.04), but not among adolescents 13–18 years (p = 0.94). The CFS also showed improvements over time in the energy (p = 0.01) and function domains (p = 0.04), indicating that fatigue declines | Four time points. T1: During the 2nd cycle of chemotherapy. Measured again every 2 chemotherapy cycles for up to 4 cycles (8 cycles total) |

| Fatigue Scale-Adolescents (CFS-A), Fatigue Scale-Children (CFS-C) [74] |

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | 8.7 (6–18) years | N = 16, 69% female | Fatigue levels did not change significantly over the 2 week study period (p = 0.42) | Three assessment points over 2 weeks |

| Fatigue Scale-Adolescents (CFS-A), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) [75] |

Leukemia, Bone tumor, Brain tumor, Lymphoma | 15.7 (12–21) years | N = 34, 29% female | Anxiety levels did not change significantly over time in the control group (p = 0.4701) or the intervention group (p = 0.8291) Fatigue levels did not change significantly over time in the control group (p = 0.5337) or the intervention group (p = 0.9949) |

Fatigue and anxiety collected daily during hospitalization. Pre-intervention (days 1–2) and post-intervention (days 3–4+) |

| Pain Squad App [51] | Osteosarcoma (57%), Ewing sarcoma (29%), Other (14%) | Study 2: 14.8 (9–18) years | Study 2: N = 14, 50% female | Detect change in pain scores after surgery using F scores: The increase in pain intensity from week 1 to week 2 was not significant. However, decrease in pain intensity from week 2 to week 3 was significant (p = 0.03). Pain interference significantly increased from week 1 to week 2 (p = 0.005), but pain interference did not significantly decrease from week 2 to week 3. Median effect sizes were large for pain unpleasantness (Cohen’s effect size = .96, 95% CI 0.14 to 1.79) and pain interference from week 1 to 2 (Cohen’s effect size = 1.08, 95% CI 0.16 to 2.00) |

Daily assessments for 3 weeks: Participants started completing daily assessments 1 week before scheduled surgery. Then continued to complete daily assessments the next two weeks after surgery |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-4.0 Generic Core (PedsQL) [61] | Primary intracranial tumors. Children alive at one year after diagnosis were included in analyses | Median: 9.4 (1.8–16.6) years | N = 26, does not report % female | There were statistically significant improvements in HRQOL over time for the total and physical summary scores (p = 0.01), but not for the psychosocial summary, emotional, social or school domains (p = 0.28). HRQOL improved over time | Three time points. T1: 1-month post-diagnosis, T2: 6-month post-diagnosis, T3: 12-month post-diagnosis |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-4.0 Generic Core (PedsQL) [76] | Primary intracranial tumors | Median: 9.1 (1.5–16.4) years | N = 35, 49% female | Mean score at T1: 73.4, mean score at T2: 78.4, and mean score at T3: 81.3. Authors do not report on the statistical significance of these increases over time | Three time points. T1: 1-month post-diagnosis, T2: 6-month post-diagnosis, T3: 12-month post-diagnosis |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-4.0 Generic Core (PedsQL) (self- and parent-report versions) [77] | n = 5 Ependymoma, n = 19 Astrocytoma, n = 3 Germ cell, n = 3 Medulloblastoma, n = 5 Other (children must completed the 12 month assessment to be included in the study | Median: 9.1 (1.5–16.4) years | N = 35, 50% female | PedsQL at T1: 73.4 and at T2 81.3 (no statistically significant difference) | Two time points. T1: 1-month post-diagnosis, T2: 12-month post-diagnosis |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-4.0 Generic Score (PedsQL) Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-Cancer Module [78] |

Hodgkin disease (Inclusion: Patients newly diagnosed, had to be enrolled by the second week after starting chemotherapy-all stages could participate | 14.7 (8–18) years | N = 49, 55% female | Responsiveness between T1 and T4 (in subset of participants who reported improvement in health based on global impression of change): Effect sizes were large for all instruments. However, when analyzing the changes between individual time points 2–3 and 3–4. The PedsQL Cancer Module had small to moderate effect sizes. The PedsQL had moderate to large effect sizes. Between T1 and T4: PedsQL Cancer Module: Significant change over time (t = 5.83, p < 0.05). Cohen’s effect size = 1.22; PedsQL 4.0 (t = 7.38, p < 0.05). Cohen’s effect size = 1.69 | Four time points. T1: 2 weeks after beginning 1st course of chemo, T2: Day 3 of 2nd course of chemo, T3: 3rd week of radiation, T4: 1 year post-diagnosis. Children who did not receive radiation therapy did not complete T3 questionnaires |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-4.0 Generic Score (PedsQL) Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-Cancer Module [62] |

Confirmed diagnosis of solid tumor, Hodgkin’s disease, Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia, Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 11.6 (5–18) years | N = 222, 45% female | Two groups (EPO and placebo) of 111 children in each. Mean PedsQL-GCS at the final visit was significantly greater in the EPO group (compared to mean baseline score) among kids 5–7 years (mean 88.0 vs. 78.1, p = 0.043), but no statistically significant differences over time in the 8–12 or 13–18 year old groups or in the placebo group | Two time points. T1: baseline, T2 = final visit |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) [79] | 56% Central Nervous System neoplasm, 36% Non-CNS solid tumor, 7.2% Leukemia. |

Median: 11.9 (8.1–21.9) years | N = 55, 42% female | Children’s ratings of distress decreased significantly pre/post magnetic resonance imaging procedure (p < 0.01) | Two time points (pre/post). T1: Immediately pre magnetic resonance imaging procedure T2: immediately after |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) [80] | Not reported | No mean (5–18 years) | N = 20, does not report % female | No significant differences in STAI anxiety | Two time points (pre/post). T1: pre-intervention and T2: post-intervention |

| Symptom Distress Scale (SDS), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) [66] |

Leukemia (64%) and Hodgkin’s Disease (36%). Inclusion: aged 10–17 years, first diagnosis of cancer, within first 4 months of initial chemo regimen, need at least three more chemo cycles to complete their treatment, able to read/write in English, no metastatic disease to brain and no history of motion sickness | No mean (10–17 years) | N = 11, 45% female | Immediately after the chemotherapy treatments, there were significant differences in the SDS (p = 0.06), but no differences in the STAIC-1 (p = 0.11). When the instruments were used 48 h after the chemotherapy was given, they found that STAIC-1 scores differed over time (p = 0.07), but there were no statistically significant differences in the SDS (p = 0.19) The hypothesis that the visual distraction would have a lasting effect on helping manage chemotherapy-induced symptoms was not supported | Two time points. T1: Immediately after chemotherapy treatments and T2: Within 48 h of chemotherapy being given |

| 10-cm Self-Report Visual Analog Scale (VAS) Nausea [68] | Experiment one: Leukemia (27%), Lymphoma (22%), Sarcoma (50%), Teratoma (4%), Brain tumor (4%) | 15.4 (9–20) years | N = 26, 27% female | In the experiment (stratified by antiemetic use), there was a significant decline in nausea observed (p = 0.02) | Two time points T1: Before video game intervention, T2: after video game intervention |

Data abstraction: use of instrument in clinical trials

We were interested in which pediatric self-report symptom measurement instruments were currently being used in oncology clinical trials. We conducted a review of the ClinicalTrials.Gov database (last checked September 2016) using these search criteria: (1) instrument name (or abbreviated name) identified from the first two searches; (2) cancer; and (3) child (limited to birth—21 years of age). We collected information on the study status (i.e., completed, recruiting), study type (i.e., interventional or observational), intervention type, phase of trial, estimated sample size, age of children, and if self-report symptoms were measured as a primary, secondary, or exploratory endpoint. Findings are presented in Supplemental Table 4.

Criteria for the symptom instruments that are ready for pediatric oncology longitudinal research

Informed by published criteria on the use of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) for outcomes research, [26–29] we identified the following three criteria to select an instrument to be ready for pediatric oncology research with longitudinal data collection:

There must be evidence of the instrument’s reliability (alpha >.70) in children receiving treatment for cancer. Reliability can include either internal consistency or test—retest reliability.

There must be evidence for the validity of the measure in children undergoing treatment for cancer. Validity includes assessments of content and construct validity.

The symptom measure must show evidence of the measure’s ability to capture symptom change over time in children undergoing treatment for cancer.

Results

Literature search results

A total of 9482 articles were identified through database searching, of which 7738 were non-duplicates. A total of 7166 articles were excluded during the initial abstract screening phase leaving us with 567 articles eligible for full-text review. An additional 516 articles were excluded during the full-text review phase, leaving 53 articles that met all eligibility criteria for inclusion in this study. For cross-sectional psychometric studies, we included 40 empirical studies. For longitudinal studies, we included 20 empirical studies.

Study selection

A minimum of two trained members of the research team independently screened all titles and abstracts for inclusion using the eligibility criteria described above. Six trained reviewers screened the initial 7738 abstracts. Inter-rater reliability among all six reviewers was kappa of 0.72 (95% CI 0.61–0.84), estimated from a subset of 100 articles that all six team members reviewed. Studies with titles and abstracts that met inclusion criteria or lacked adequate information to determine inclusion or exclusion underwent full-text review. A senior member of the review team resolved conflicts.

During the full-text review, a minimum of two trained members of the research team independently reviewed each full-text article for inclusion or exclusion based on the eligibility criteria described above. If both reviewers agreed that a study did not meet eligibility criteria, the study was excluded. If the two reviewers disagreed, a senior member of the review team resolved conflicts. Five reviewers participated in the full-text article screening.

Table 1 presents characteristics of the 38 self-report English symptom instruments used in children and adolescents undergoing cancer treatment that met our eligibility criteria. Table 1 includes a summary of the instruments’ age range, types of symptoms assessed, attributes of the symptoms measured (e.g., severity, frequency, interference), recall period (e.g., past 7 days), number of questions included, and response options.

Table 1.

Characteristics of pediatric self-report symptom measures in cancer research

| Instrument name (alphabetical order) | Age range (years) | Symptoms (and HRQOL) domains assessed | Symptom attributes (severity, frequency, etc.) | Reference period | Number of questions | Number of response options |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Sleep Wake Scale (ASWS) | 12–18 | Sleep quality | Frequency | “Last week” | 28 | 6 |

| Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ) | 10–18 | Physical functioning, pain, sadness, fatigue, mobility, concentration, anger, frightened, loneliness, Nervousness, body image, worry, headache, insomnia, overall health, behavior issues |

Interference, Frequency, Severity | Varied by question: “Past 4 weeks”; “In general”; “Compared to one year ago” |

87 | 4–6 |

| Childhood Cancer Stressors Inventory (CCSI) | 7–13 | Fatigue, vomiting, pain, worry, insomnia, anorexia, hair loss, weight change | Presence, Frequency, Intensity | Since the diagnosis of cancer | 18 | 5 |

| Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) | 7–17 | Depression | Presence, Severity | “Past 2 weeks” | 28 | 3 |

| Children’s International Mucositis Evaluation Scale (ChIMES) | 8–18 | Mucositis (mouth/throat pain, dysphagia, mouth sores) | Severity, Interference, Presence | “Today” | 6–7 (conditional questions) | 2–6 |

| Constipation Assessment Scale (CAS) | 9–21 | Abdominal distension (bloating), constipation, diarrhea, fecal incontinence, rectal pain, change in flatulence | Presence, Severity | “Compared to your usual pattern” | 8 | 3 |

| Faces Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R) | 4–16 | Pain | Presence, Severity, Intensity | “Right now” | 1 | 6 |

| Fatigue Scale-Adolescents (FS-A) | 13–18 | Fatigue | Frequency, Interference | “Past 7 days” | 13 | 5 |

| Fatigue Scale-Children (FS-C) | 7–12 | Fatigue | Frequency, Interference | “Past 7 days” | 10 | 2–5 |

| Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) 7–12 | 7–12 | Fatigue, sadness, Itch, pain, worry, anorexia, nausea, insomnia |

Presence, Frequency, Severity, Distress |

“Last 2 days” | 8 (Additional conditional questions) | 2–4 |

| Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) 10–18 | 10–18 | Fatigue, pain, concentration, cough, dry mouth, nausea, worry, neuropathy, insomnia, diarrhea, sadness, vomiting, problems with urination, nervousness, difficulty swallowing, anorexia, hair loss, weight change, dizziness, changes in skin, sweating, itch, headache, irritability, dyspnea, drowsiness, dysgeusia, mucositis, constipation, lymphedema | Presence, Frequency, Severity, Distress |

“Past week” | 30 (Additional conditional questions) | 2–5 |

| Minneapolis-Manchester Quality of Life-Adolescent Form (MMQL-AF) | 13–20 | Physical functioning- (such as fatigue, mobility), Psychological functioning- (such as sadness, worry, anger, nervousness, loneliness, fear), Cognitive functioning- (such as concentration, memory), Appearance- (such as body image), social functioning |

Presence Distress Frequency |

Participants are asked to choose a statement that describes themselves or how they feel “in general” | 46 | 2–5 |

| Minneapolis-Manchester Quality of Life-Youth Form (MMQL-YF) | 8–12 | Physical symptoms- (such as blurry vision, insomnia, headache, pain, muscle aches, difficulty hearing, difficulty speaking), physical functioning- (such as fatigue, mobility), psychological functioning- (such as sadness, worry, anger, fear, loneliness), family dynamics and outlook on life | Presence Distress Frequency |

Participants are asked to choose a statement that describes themselves or how they feel “in general” | 32 | 4–5 |

| Oral Mucositis Daily Questionnaire (OMDQ) | 12–18 | Mouth and throat soreness, diarrhea, overall health | Severity Impact Interference |

“Past 24 h” | 3 (Additional conditional questions) | 4 |

| Pain Squad App | 8–18 | Pain | Intensity, Interference, Unpleasantness | “Last 12 h” | 22 (Additional conditional questions) | Varies from 0–12; Some open-ended questions |

| Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Pediatric Measures | 8–17 | Depression, Anxiety, Anger, Pain Interference, Fatigue, Mobility, Upper extremity functioning (see www.HealthMeasures.net for a full list of PROMIS Pediatric domains) | Frequency | “Past 7 days” | PROMIS allows different lengths of measures; Tested are 8 items per symptom except fatigue with 10 items. | 5 |

| Pediatric Advanced Care Quality of Life Scale (PAC-Qol) | 8–12 child 13–18 adolescent |

Physical Comfort- (such as pain, constipation, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, dyspnea, anorexia, headache, nosebleeds, blurry vision, mobility, upper extremity functioning, difficulty speaking), psychological well-being- (such as emotional distress, worry, loneliness, nervousness, anger, fear, sadness, insomnia, memory) | Frequency | “Past 7 days” | 57–65 depending on version | 4 |

| Pediatric Cancer Quality of Life Inventory (PCQL-32) (two versions based on age) |

8–12 child 13–18 adolescent |

Physical functioning- (such as mobility), disease and treatment-related symptoms/problems- (such as anxiety, nausea, dysgeusia, muscle aches, pain), psychological functioning- (such as sadness, fear, worry), social functioning- (such as behavior issues), cognitive functioning- (such as concentration, memory) | Interference, Frequency | “Past month” | 32 | 4 |

| Pediatric-Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Pediatric Anorexia/Cachexia (Peds-FAACT) | 7–12 version; 12–18 version; |

Fall, fatigue, mobility, Muscle weakness, pain, depression, worry, anorexia, dysgeusia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, loneliness, nervousness |

Frequency, Interference | “Past 7 days” | 37–40 depending on version | 5 |

| Pediatric-Functional Assessment of Anorexia and Cachexia Therapy (Peds-FAACT) | 12–18 | Anorexia, nausea, abdominal pain, vomiting | Frequency | “Past 7 days” | 10 | 5 |

| 10 Item version | ||||||

| Pediatric Nausea Assessment Tool (PeNAT) | 4–18 | Nausea | Intensity | “Right now” | 1; Plus script to determine term used by family to refer to nausea and vomiting |

4 |

| Pediatric Oncology Quality of Life Scale (POQOLS) | 8–19 | Physical function- (such as fatigue, mobility, pain), Reaction to current treatment- (such as hair loss, weight change, nausea, vomiting), Emotional distress- (such as sadness, anger, insomnia, fear) | Frequency | “Past two weeks” | 21 | 7 |

| Pediatric Patient-Reported Outcomes Version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (Pediatric PRO-CTCAE) | 7–15 | Library including 62 symptomatic adverse events; core items include: abdominal pain, anorexia, anxiety, constipation, cough, depression, diarrhea, fatigue, headache, insomnia, mucositis oral, nausea, pain, peripheral sensory neuropathy, vomiting, (and 47 additional less prevalent items) | Frequency, severity, interference | “Past 7 days” | Variable depending on the symptoms selected from the library | 4 |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-Cancer Module (4 versions based on age) |

5–7 version; 8–12 version; 13–18 version; 18–25 version |

Pain and hurt, nausea, procedural anxiety, treatment anxiety, worry, cognitive problems (such as concentration), body image | Severity | “Past one month” | 27; (5–7 version 26) |

5; 5–7 version has 3 response options |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-4.0 Generic Core (PedsQL) | 5–7 version; 8–12 version; 13–18version; 18–25 version |

Physical functioning- (such as pain, fatigue, mobility), emotional functioning- (such as depression, insomnia, anger, scared), Social functioning, School functioning- (such as concentration problems) |

Severity | Acute version- “Past 7 days” Standard version- “Past 1 month” |

23 | 5; 5–7 version has 3 response options |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-Multidimensional Fatigue Scale (3 versions based on age) |

5–7 version; 8–12 version; 13–18 version |

General fatigue, sleep/rest fatigue (such as insomnia), cognitive fatigue (such as concentration problems) | Severity | “Past one month” | 18 | 5; 5–7 version has 3 response options |

| Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMNS) | 6–19 | Physiological anxiety- (such as nausea, fatigue, insomnia, dyspnea), worry and oversensitivity- (such as nervousness, fear, irritability, loneliness), concentration anxiety- (such as restlessness) | Presence | “What I think and feel” | 37 | 2 |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC State) | 9–12 | Apprehension, tension, worry | Intensity | “Feelings now, at this moment” | 20 | 4 |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC Trait) | 5–13 | Anxiety | Frequency | “How you generally/usually feel” | 20 | 4 |

| Symptom Distress Scale (SDS) | 10–17 | Nausea, anorexia, insomnia, pain, fatigue, bowel discomfort, concentration, dyspnea, cough | Severity | “Lately” | 13 | 5 |

| Symptom Screening in Pediatrics Tool (SSPedi) | 8–18 | Sadness, worry, anger, fatigue, mouth sores, pain, headache, neuropathy, anorexia, vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, constipation, concentration, memory, dysgeusia | Interference | “Yesterday or Today” | 15 | 5 |

| 10-cm Self-Report Visual Analog Scale (VAS) Nausea | 9–20 | Nausea | Intensity | “Right now” | 1 | Left endpoint-No nausea Right endpoint-Nausea as bad as it could be |

| 10-cm Self-Report Visual Analog Scale (VAS) Anxiety | 9–18 | Nausea Anxiety |

Intensity | “Right now” | 2 | Left endpoint-No Nausea/Anxiety Right endpoint-Nausea/Anxiety as bad as it could be |

The seven validated PROMIS domains are considered as seven separate instruments

Pediatric self-report instrument characteristics

The youngest recommended age was 4 years; instruments intended for younger ages rely on faces scales for response options (Table 1). Most instrument age ranges were from 8 to 18 years (Table 1). Some instruments were dedicated to measuring one symptom while others included a range of symptoms experienced by children and adolescents undergoing cancer treatment. Reference periods for symptom recall ranged between “right now” (or today), 7 days (or the past week) up to one year prior. Response options varied considerably and most instruments used a version of the Likert scale. The most commonly assessed symptoms were nausea, pain, fatigue, depression, and anxiety. The 38 self-report symptom instruments included in this review measured approximately 81 different symptoms. The most comprehensive instrument was the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) 10–18, assessing 30 symptoms [5]. Whereas the Pediatric Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) is an item library assessing up to 62 symptomatic toxicities [30].

Psychometric studies

Table 2 summarizes the 40 psychometric studies of the 38 symptom instruments included in Table 1. The majority of the studies assessed cross-sectional psychometric properties with 10 instruments being assessed longitudinally. Sample sizes ranged from 6 to 291 children/adolescents, but nearly 60% of eligible studies included fewer than 100 children. Instruments generally used a diverse sample of children and adolescents with respect to cancer type, age, and gender.

Instruments varied in terms of reporting scores for individual symptoms versus aggregating across symptoms to report an overall toxicity score. As such, some studies reported one internal consistency score, whereas others reported Cronbach’s alphas for instrument subscales or specific symptoms. Overall, 20 validated instruments reported reliability measures above 0.70 when assessed at single time point (internal consistency) or multiple time points (test—retest). There were 15 instruments that did not report any measures of reliability and three instruments whose reliability did not meet our 0.70 threshold.

The types of evidence for the validity of the instruments also varied across instruments. Many studies evaluated an instrument’s content validity using focus groups, in-depth interviews, or expert opinion (e.g., clinicians). Other studies tested known group’s validity by comparing children on and off treatment or children with cancer to other chronic diseases or to healthy children their age. Convergent validity was often evaluated by comparing pediatric self-report scores to parent proxies as well as clinicians and nurses. Other studies assessed convergent validity by comparing the new instrument with an established PRO instrument that was known to measure the same or similar concept of interest. Finally, some studies compared self-report scores to other more objective measures such as sleep duration or number of emetic episodes.

Longitudinal studies

Table 3 presents longitudinal studies (not test—retest studies) that examined an instrument’s responsiveness or sensitivity to changes over time. Ten instruments were used to assess changes over time in children undergoing cancer treatment. Each study include 2–5 assessment points spanning two or more 24-h sequential periods and several months up to one year. We also present data on the timing of assessment points to highlight the variation across studies. Many of the eligible studies were not designed as psychometric studies, but rather were studies that evaluated symptoms over time as part of their larger study objectives (e.g., evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention).

Instruments used in clinical trials

Supplemental Table 4 includes instruments that have been used in studies that are registered in clinicaltrials.gov. Twenty-two instruments were identified in this search. The PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales, PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, PedsQL 3.0 Cancer Module, Fatigue Scale (Adolescent and Child version), and the Faces Pain Scale-Revised were the instruments most often cited in clinicaltrials.gov.

Discussion

This systematic review identified 38 self-report symptom instruments used in pediatric oncology research with at least one psychometric validation study in children with cancer undergoing active treatment. These English language instruments varied considerably in terms of symptoms measured, phrasing and format of questions asked, and the amount of psychometric evidence supporting each instrument.

Ten of the instruments were included in a study with the intention of measuring change in a symptom or aggregate of symptoms over time. However, a majority of the longitudinal studies were not designed as a psychometric study to evaluate the responsiveness of the instrument. For example, some studies collected self-report symptom and HRQOL data over time, but did not characterize the trends over time. The following instruments met our three assessment criteria for use in longitudinal pediatric oncology studies (described above): Children’s Depression Inventory, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children, Children’s International Mucositis Evaluation Scale, Fatigue Scale (Child and Adolescent versions), Pain Squad App, PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales, and PedsQL 3.0 Cancer Module. These eight instruments have been psychometrically evaluated (both reliability and validity) and able to detect significant changes over time. All of the instruments, except the Pain Squad App, are currently being used in a pediatric oncology clinical trial.

The NIH’s Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Pediatric instruments include measures of symptoms such as anxiety, depressive symptoms, fatigue, and pain interference. At the time of this article’s publication, cross-sectional data supporting the validity and reliability of the instruments in children with cancer have been published [31, 32]. In addition, these measures have been found to be responsive over time [14]. It is the opinion of the authors that the PROMIS pediatric measures show adequate evidence for their use in longitudinal pediatric oncology studies.

Methods for summarization of patient-reported data as scores also varied considerably, an issue particularly important for symptom research. The use of summary scores (i.e., aggregating across multiple symptoms) to represent overall patient well-being or symptom burden can often mask domain- or symptom-specific decrements. Summarizing data as individual symptom scores allows researchers and clinicians to examine the effectiveness of an intervention on a specific symptom or adverse event.

Some studies did not show statistically significant changes in symptoms over time. We believe that some of the non-significant findings are due to specific features of the study design. For example, issues of small sample sizes and not selecting time points that capture an instrument’s sensitivity (i.e., assessments selected at times when symptoms change in intensity) were seen across most studies that did not observe differences over time. Factors such as broad study participant inclusion criteria and ambiguous time points likely contributed to small effect sizes and insignificant results. If researchers intend to measure an instrument’s responsiveness, they must be thoughtful and deliberate when selecting time points, being careful to choose time points where it is reasonable to expect a change in the symptom experience. Another possibility is to ask the patient directly if they felt a change in their symptoms between time points, which could be done by administering a global impression of change scale. These considerations are especially important for social or behavioral interventions where the anticipated effect size may already be small.

Additionally, a few studies, including clinical trials, collected longitudinal data using self-report symptom instruments, but investigators did not present findings in their publications. Researchers should consider including results from these types of instruments in their published findings to add further to the evidence base. Further, for studies that include different instrument versions for child, adolescent, and adult reports of symptoms, treatment toxicities, and quality of life, we recommend that the findings be distinctly reported for each instrument version and not as one total group.

Limitations

There were limitations to this systematic review. First, our search was limited to English language instruments because verifying the quality of the translation of the instrument and the further content evaluation was outside the scope of this review. Including only English language instruments limits the geographical scope of this review. Next, inconsistent use of the instrument’s name challenged our search within clinicaltrials.gov. As such, if an investigator entered only a portion of the instrument’s name or abbreviation, it is possible the instrument does not appear in Supplemental Table 4. In addition, while we did assess the quality of the instrument (i.e., validity and reliability were assessed), we did not examine the quality of each study. We recommend that future studies examine this important issue. Lastly, we focused only on symptom measures for children currently undergoing active cancer treatment, but further studies should also consider self-report instruments for children and adolescents in palliative care as well as survivors of childhood cancer.

Conclusion

Investigators should consider several issues in the selection of the appropriate self-report instrument for their pediatric oncology study. Before considering the use of an instrument, the researcher should have a comprehensive understanding of the characteristics of the target population in terms of age, cancer type, and disease status. They should know what outcomes or domains they want to measure, which should be driven by the study’s research aims. The selected instrument should be designed to be relevant for the age of the children under study, and take into account a child’s literacy and cognitive abilities. In addition, the instrument should have undergone psychometric evaluation of reliability, validity, and responsiveness, ideally with the study’s target population. If the particular domains are primary study endpoints, choosing an instrument with strong reliability and validity data is optimal.

This systematic review serves as guidance for pediatric oncology researchers to select appropriate symptom measures with strong psychometric evidence. The overarching motivation behind this work is to enhance the child’s voice in pediatric oncology research studies in order to obtain a better understanding of the impact of cancer and its treatment on the lives of children.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Natalie Ernecoff, Kathryn Jackson, Susan Keller, and Sejin Lee for their help with this study.

Funding This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01CA175759.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Informed consent Informed consent from study subjects was not needed as the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill IRB granted this research exemption from review.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11136-017-1692-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Ethical approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2016. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2016. p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CureSearch Childhood Cancer Statistics. http://curesearch.org/Childhood-Cancer-Statistics.

- 3.Sateren WB, Trimble EL, Abrams J, Brawley O, Breen N, Ford L, et al. How sociodemographics, presence of oncology specialists, and hospital cancer programs affect accrual to cancer treatment trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20(8):2109–2117. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleyer A, Budd T, Montello M. Adolescents and young adults with cancer: The scope of the problem and criticality of clinical trials. Cancer. 2006;107(7 Suppl):1645–1655. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins JJ, Byrnes ME, Dunkel IJ, Lapin J, Nadel T, Thaler HT, et al. The measurement of symptoms in children with cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2000;19(5):363–377. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Docherty SL. Symptom experiences of children and adolescents with cancer. Annual Review of Nursing Research. 2003;21:123–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eiser C, Hill JJ, Vance YH. Examining the psychological consequences of surviving childhood cancer: Systematic review as a research method in pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2000;25(6):449–460. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.6.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linder LA. Measuring physical symptoms in children and adolescents with cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2005;28(1):16–26. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pickard AS, Topfer LA, Feeny DH. A structured review of studies on health-related quality of life and economic evaluation in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 2004;2004(33):102–125. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruland CM, Hamilton GA, Schjodt-Osmo B. The complexity of symptoms and problems experienced in children with cancer: A review of the literature. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2009;37(3):403–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vance YH, Eiser C. The school experience of the child with cancer. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2002;28(1):5–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2002.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waters E, Stewart-Brown S, Fitzpatrick R. Agreement between adolescent self-report and parent reports of health and well-being: Results of an epidemiological study. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2003;29(6):501–509. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2003.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.F. A. D. A. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, editor. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, F. A. D. A. Guidance for industry: Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinds, P. S. (2016). In B. B. Reeve (Ed.), (Email ed.).

- 15.Hockenberry MJ, Hinds PS, Barrera P, Bryant R, Adams-McNeill J, Hooke C, et al. Three instruments to assess fatigue in children with cancer: The child, parent and staff perspectives. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2003;25(4):319–328. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00680-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Gales C, Costet N, Gentet JC, Kalifa C, Frappaz D, Edan C, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation of a health status classification system in children with cancer. First results of the French adaptation of the Health Utilities Index Marks 2 and 3. International Journal of Cancer Supplement. 1999;12:112–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glaser AW, Davies K, Walker D, Brazier D. Influence of proxy respondents and mode of administration on health status assessment following central nervous system tumours in childhood. Quality of Life Research. 1997;6(1):43–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1026465411669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parsons SK, Barlow SE, Levy SL, Supran SE, Kaplan SH. Health-related quality of life in pediatric bone marrow transplant survivors: According to whom? International Journal of Cancer Supplement. 1999;12:46–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(1999)83:12+<46::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]