SUMMARY

Patterns of spontaneous brain activity, typically measured in humans at rest with fMRI, are used routinely to assess the brain’s functional organization. The mechanisms that generate and coordinate the underlying neural fluctuations are largely unknown. Here we investigate the hypothesis the nucleus basalis of Meynert (NBM), the principal source of widespread cholinergic and GABAergic projections to the cortex, contributes critically to such activity. We reversibly inactivated two distinct sites of the NBM in macaques while measuring fMRI activity across the brain. We found that inactivation led to strong, regionalized suppression of shared or “global” signal components of cortical fluctuations ipsilateral to the injection. At the same time, the commonly studied resting state networks retained their spatial structure under this suppression. The results indicate the NBM contributes selectively to the global component of functional connectivity, but plays little if any role in the specific correlations that define resting state networks.

ETOC

Turchi et al. demonstrate that the basal forebrain, a major source of modulatory projections to the cerebral cortex, controls the level of broadly shared (“global”) spontaneous fluctuations without altering the spatial structure of resting-state networks.

INTRODUCTION

The brain’s ongoing activity fluctuations, which persist in the absence of sensory stimulation or movement generation, are one of its most conspicuous features. Studying the correlational structure of this activity has led to important insights about the functional organization of the human brain (Fox and Raichle, 2007; Yeo et al., 2011). However, the mechanisms that generate and orchestrate this continual stream of neural events are largely unknown. Neuromodulatory systems may play an important role, as they can influence spontaneous activity across different time scales. For example, early work in animals established that the cerebral cortex is under strong influence of ascending brainstem projections (Magoun, 1952; Nauta and Kuypers, 1958), and that when these pathways are transected, the forebrain can fall into a synchronous state resembling slow-wave sleep (Bremer, 1935). Might these neuromodulatory projections hold the key to understanding the activity correlations that underlie fMRI functional connectivity?

One important source of neuromodulation in all mammals is the basal forebrain, whose regions include the diagonal band and nucleus basalis of Meynert (NBM) (Heimer and Van Hoesen, 2006). The large projection neurons sitting in these regions innervate nearly the entire isocortex, as well as the hippocampus, amygdala and other prominent structures, such as the thalamic reticular nucleus (Mesulam et al., 1983; Pearson et al., 1983; see also Kitt et al., 1987, and Ghashghaei and Barbas, 2001). They consist of varied cell subpopulations, including cholinergic, glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons, which together complement the broad ascending neuromodulatory inputs from the brainstem (Wainer et al., 1984). Clusters of cholinergic cells in the basal forebrain, named Ch1 to Ch4 according to their mediolateral position, each innervate specific regions of the mammalian telencephalon with partially overlapping projections (Mesulam et al., 1983; Zaborszky et al., 2013). Electrical stimulation of these regions diminishes slow cortical synchronization, an effect that is thought to depend on acetylcholine acting upon muscarinic receptors (Metherate et al., 1992; Disney and Reynolds, 2014; but see also Hangya et al., 2015, as well as Raver and Lin, 2015). In the monkey, the activity of neurons in the basal forebrain conjointly reflects both high-level cognitive parameters and indicators of behavioral arousal (Monosov et al., 2015; Ledbetter et al., 2016). In the rodent, recent optogenetic studies have highlighted the differential contributions of cholinergic, glutamatergic, and GABAergic neurons in the basal forebrain to cognitive processes (Lin et al., 2015; Gritton et al., 2016), as well as the regulation of wakefulness (Xu et al., 2015; Zant et al., 2016). While the broad organization of this region is similar in rodents and monkeys, some important aspects, such as the proportion of cholinergic neurons and local connectivity, appears to be very different (Raver and Lin, 2015; Mesulam et al 1983; Martin et al., 1993). In humans, the cholinergic elements of the basal forebrain are prominent and known to play an important role in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (see Schliebs and Arendt, 2011).

In the past decade, the field of human fMRI has embraced spontaneous resting state activity, most often focusing on temporal correlations across the brain as measures of functional connectivity. This approach is widely used to study network organization, brain development, plasticity, and neurodegeneration in disease (Pendl et al., 2017; Hillary and Grafman, 2017; Munro et al., 2015). Analysis of the spatiotemporal structure of fMRI data has distinguished between “resting state networks”, defined by the selective correlation among functionally interacting brain areas (e.g., Damoiseaux et al., 2006) and “global activity”, which is broadly shared across the cerebral cortex (e.g., Schölvinck et al., 2010). There is ample evidence that, in a given voxel, both fMRI signal components reflect local fluctuations in neural activity (for a review, see Leopold and Maier, 2012; Chen et al., 2017). Nonetheless, interpreting the results of functional connectivity can be difficult owing to our limited understanding of what ultimately drives the underlying neural fluctuations. One interesting prospect is that common input from basal forebrain areas, such as the NBM, might serve to orchestrate spontaneous activity across the brain. This idea is supported by recent evidence that anatomical projections from the NBM target multiple cortical areas that are themselves interconnected within a functional network (Zaborszky et al., 2013). Thus, it is possible that the NBM might modulate functionally related regions in parallel, leading to a slow synchrony of neural activity and fMRI that is interpreted as functional connectivity.

In the present study, we tested this hypothesis in macaques by combining reversible pharmacological inactivation of two NBM subregions with whole-brain resting state fMRI scanning. Inactivation led to a prominent ipsilateral reduction in the global component of spontaneous activity across a broad but circumscribed cortical region that depended on the specific NBM subregion. Strikingly, however, the commonly described resting state networks retained a spatial structure that was nearly indistinguishable from that observed in the control sessions. The results demonstrate that input from the basal forebrain regulates the global component of resting state time course, but plays little if any role in determining the spatial structure of commonly studied bilateral resting state networks.

RESULTS

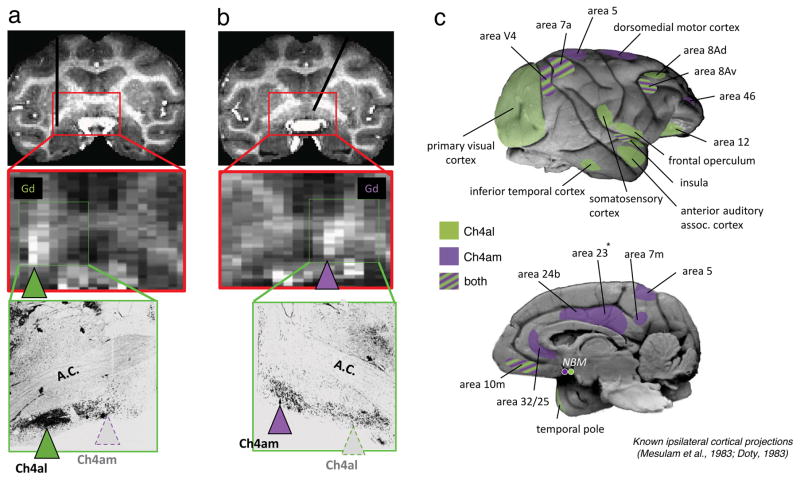

The main objective of this study was to determine the contribution of the NBM to spontaneous fMRI fluctuations in the cerebral cortex. To this end, we inactivated each of two small subregions of the NBM by injecting the GABAA agonist muscimol (1.8–2.4 μL). One set of microinjections was centered on an anteromedial cluster Mesulam termed Ch4am, from which the majority of magnocellular cholinergic cells innervate medial cortical regions, including the cingulate cortex (Mesulam et al., 1983; see Figure 1b,c). The other injection site targeted more lateral regions that included portions of Mesulam’s regions Ch4al, Ch4id, and Ch4iv, which collectively send projections to broad swaths of more lateral cortex, including visual areas (Figure 1a,c). For simplicity, we refer to this latter site as Ch4al. It is important to note that, while we adopt this nomenclature in the present study, we did not attempt to dissociate the contribution of cholinergic neurons from other species of basal forebrain projection neurons (Mesulam et al., 1983; Zaborszky et al., 2008). In fact, our injections likely affected a heterogeneous population of GABAergic, glutamatergic and cholinergic neurons projecting to the same areas.

Figure 1. Inactivation of basal forebrain subregions.

MRI was used to guide injection cannula through a grid to targets more anteromedial or more posterolateral target locations in the basal forebrain. During each session, gadolinium (Gd) was co-injected as a contrast agent to visualize the location of the injection. (a) Example of a session targeting the Ch4al position. Upper panel shows the position of the cannula. Middle panel shows the spread of Gd for one session. Lower panel shows the location of cholinergic staining defining Ch4al basal forebrain subregion (green arrowhead, image, adapted from Mesulam et al., 1983). (b) Same format as (a), but for Ch4am injection in opposite hemisphere. (c) Pattern of known relevant cortical projections from basal forebrain in the macaque, based on previous anatomical tracer studies.

The present analysis draws upon thirty sessions in two monkeys, with a total of 107 scans, all of which were 30 minutes in length (see Table 1). In twenty-one of the sessions (70 scans), we unilaterally inactivated either Ch4am or Ch4al, with either no manipulation of opposite hemisphere or injection of saline as a control. We carried out 9 further control sessions (37 scans) in which there was either no injection or unilateral injection of saline. For inactivation sessions, we co-injected gadolinium with muscimol to aid in the visualization of the injection spread (Wilke et al., 2010). The following sections describe the effects of NBM inactivation on different aspects of the ongoing fMRI fluctuations at rest, with a focus on the cerebral cortex.

Table 1.

Description of all sessions included in this study.

| Subject | Ch4al inactivation left hemisphere |

Ch4al inactivation right hemisphere |

Ch4am inactivation left hemisphere |

Ch4am inactivation right hemisphere |

Control sessions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sessions (scans) | sessions (scans) | sessions (scans) | sessions (scans) | sessions (scans) | |

| Monkey Z | 5 (15) | 6 (18)* | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (15)** |

| Monkey F | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | 3 (11) | 3 (10) | 5 (22)*** |

includes 2 sessions (7 scans) with saline in left hemisphere

includes 3 sessions (12 scans) with no injection, and 1 session (3 scans) with saline in Ch4al right hemisephre

includes 2 sessions (8 scans) with no injection, and 3 sessions (14 scans) with saline in Ch4al (left hemisphere)

Global fMRI fluctuations depend on nucleus basalis input

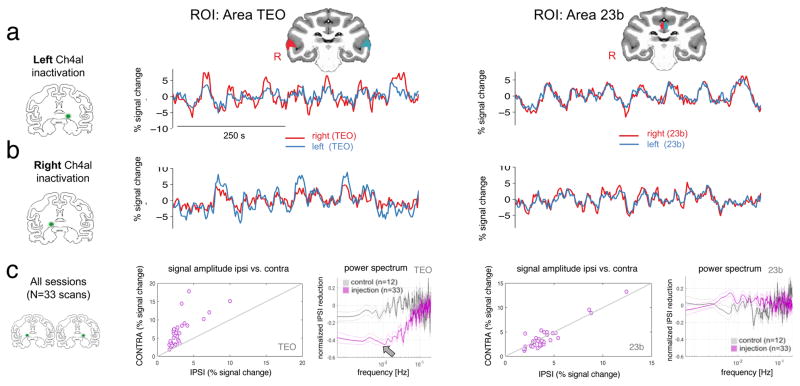

The main effect of muscimol infusion into the NBM was a prominent and sustained decrease in the relative amplitude of spontaneous fluctuations in the cerebral cortex ipsilateral to the injection site. With each injection, this decrease was expressed over a broad but circumscribed swath of cortex, whose spatial distribution depended on the injection target. The effect was evident in the raw fMRI time courses, and was most obvious when comparing spontaneous activity in corresponding regions of the left and right cerebral hemispheres. For example, Figures 2a and 2b compare the effects of left versus right Ch4al inactivation on the spontaneous fluctuations in a region of the temporal cortex TEO (left column), which is known to receive direct input from this basal forebrain subregion. Inactivation led to a relative decrease in the amplitude of raw fMRI signal fluctuations ipsilateral to the injection site, in this case on the left side. By contrast, no interhemispheric differences were observed during the same time points among voxels in the cingulate cortex (area 23b, right column), whose innervation by the basal forebrain arises from a more medial subregion. These effects were consistent across Ch4al inactivation sessions, with a lower ipsilateral fMRI amplitude in TEO in all 33 scans, but not in the cingulate cortex (see Figure 2c; see also Figure S1 for Ch4am inactivation sessions). In area TEO, which is known to receive direct projections from Ch4al, the power spectra were attenuated in the low-frequency range (primarily below 0.05 Hz, Figure 2c, arrow). In contrast, no such effect was found in the cingulate cortex (area 23b), which does not receive projections from Ch4al.

Figure 2. NBM inactivation induces regional changes in the amplitude of spontaneous fMRI signals.

Time series extracted from symmetric ROIs following inactivation of the Ch4al subregion in the left (a) and right (b) hemispheres. In example area TEO in the inferotemporal cortex, which is known to receive direct projections from Ch4al, the amplitude of spontaneous fluctuations is attenuated in the hemisphere ipsilateral to the injection site following both left- and right-hemisphere injections. In contrast, no inter-hemispheric differences were observed during the same time intervals in the cingulate cortex (area 23b), which does not receive projections from Ch4al. This effect was observed in all 33 Ch4al inactivation scans (c), with a lower ipsilateral fMRI amplitude in inferotemporal cortex but not in the cingulate cortex. Each point corresponds to a single scan, and amplitude was computed using variance as a summary statistic. Power spectra on the right, computed from the same symmetric ROIs, demonstrate the selective drop in the low-frequency components of the fMRI signal. The plotted spectra are the normalized differences between the hemispheres, computed at each frequency value as (ipsilateral-contralateral)/(ipsilateral +contralateral). Data are shown for all Ch4al injection sessions of monkey Z, and shaded error bars reflect standard error.

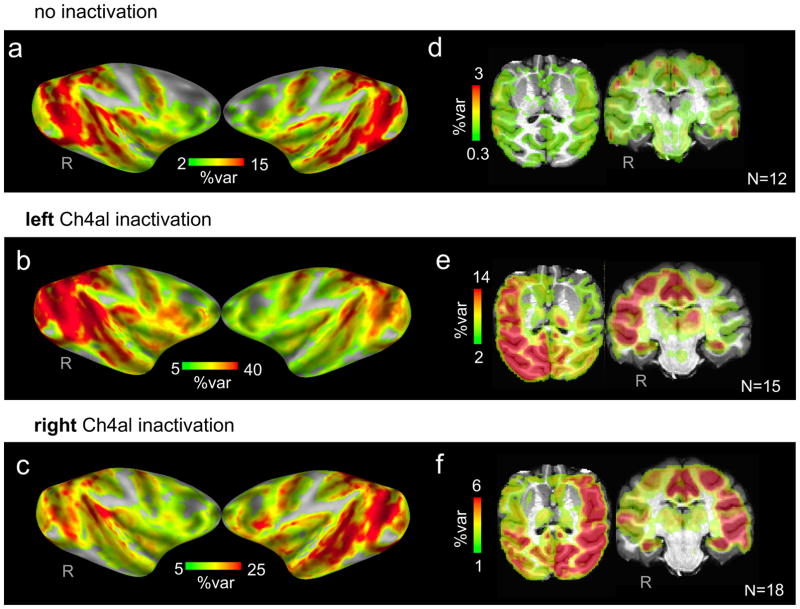

The observed regional differences in the amplitude of spontaneous activity prompted us to map the cortical areas whose shared fluctuations were affected following inactivation of each of the NBM subregions. We approached this by mapping the spatial distribution of the global signal in two ways. In the first (Figure 3a–c), we computed the average voxel time course across the entire cerebral cortex, reasoning that this function might approximate the global signal. In the second (Figure 3d–f; see Figure S2a for results from Monkey F and Supplementary Methods for further details), we computed the difference in the average cortical signals independently in the two hemispheres. Both methods demonstrated a regional suppression of the global signal in the injected hemisphere. In the control sessions, correlation with the global signal had a symmetric distribution across the two hemispheres (Figure 3a,d n=12 scans). Reversible inactivation of Ch4al in the left hemisphere led to prominent decreased correlations within the left hemisphere (Figure 3b,e n=15 scans), which were most obvious in visual, insular, somatosensory, auditory association and temporal cortical regions, areas whose innervation by the basal forebrain is known to originate in and around Ch4al. Other cortical regions that receive input from different NBM subregions, such as the cingulate gyrus and hippocampus, were spared. Inactivation of the same subregion in the right hemisphere led to mirror asymmetrical effects (Figure 3c,f n=18 scans). Maps for individual Ch4al sessions are shown in Figure S2b–c, with time series analysis in Figure S2d–i demonstrating that the ipsilateral decrease in global signal cannot be ascribed to changes in CO2 or subject motion. Furthermore, regression of the CO2 time series prior to this analysis did not alter the basic result (Figure S3). Figure S4a shows the result of Ch4am inactivation. One consistent observation was that for both Ch4al and Ch4am injections, a large region of the contralateral thalamus also exhibited a drop in its global signal component, an unexpected observation that is currently under investigation (see Figure S4b).

Figure 3. NBM inactivation alters the distribution of shared spontaneous fluctuations.

(a–c) Surface maps display the percentage of temporal variance (R2) explained by the global signal at each voxel, during control sessions with no injection (a), and following injection of the Ch4al subregion on the left (b) and right hemispheres (c). A symmetric distribution of global signal correlations can be seen in the control sessions, while Ch4al inactivation corresponded with a marked reduction within the hemisphere ipsilateral to the injection site. Note the difference in scaling of the plots in (b) and (c), corresponding to left- and right-hemisphere injections. (d–f) Axial and coronal sections that further highlight regional suppression of the shared signal, in this case computing the difference in average signal between hemispheres (see main text and Supplementary Methods). Note obvious sparing of cingulate and hippocampus in the coronal slices in (e) and (f).

Together, these results demonstrate that time-varying input from a small subregion of the basal forebrain is a critical determinant of spontaneous fMRI activity across the ipsilateral cerebral hemisphere. This input significantly affects both the amplitude and synchrony of shared common signal over broad regions in a manner that appears to be determined by the known long-range anatomical projections of neurons in this region. We next sought more evidence that the measured changes in spontaneous fMRI activity were critically dependent on the precise region of inactivation within the nucleus basalis of Meynert.

Spatial specificity of NBM regulation of the cortex

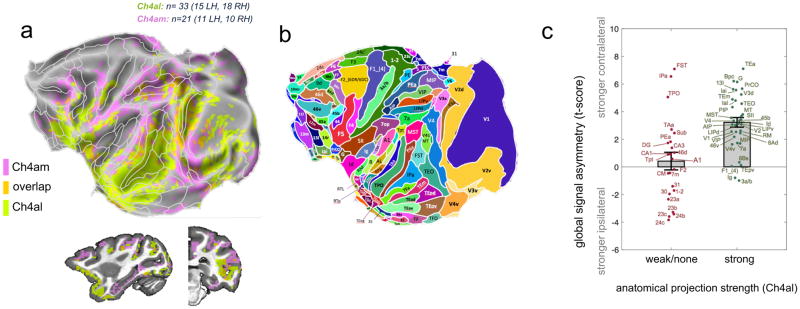

We next compared the reduction in the global signal component following inactivation of two distinct NBM subregions, Ch4al and Ch4am, which are separated by approximately 3.5 mm and are known to have different anatomical projection targets (Mesulam et al., 1983; see Figure 1c). Consistent with different subregions having distinct projection targets, we found that the two injection sites led to nearly complementary spatial patterns of global signal suppression across the cortex. This is most obvious when viewed on the flattened cortical surface (Figure 4a,b; see also Figure S4c for regional inactivations shown separately for each monkey), which demonstrates separation between the medial and parietal areas affected by Ch4am inactivation (pink) versus the temporal, occipital, and frontal regions affected by Ch4al inactivation (green). Notably, there was virtually no intersection between these affected territories (orange).

Figure 4. Spatially distinct cortical zones influenced NBM subregions.

(a) Direct comparison of regions having most significant ipsilateral suppression of global signal for the Ch4al (green; monkey Z) and Ch4am (pink; monkey F) injections sites. Maps are thresholded to show voxels with the highest 35% t-scores (ipsilateral<contralateral) in each condition, and are superimposed upon the areal boundaries of the Saleem and Logothetis atlas. (b) For anatomic reference, the areal boundaries based on the Saleem and Logothetis atlas are aligned with the map in (a). (c) Region-by-region correspondence between anatomical projection strength (from Ch4al) and asymmetry of the global signal correlation, for the Ch4al injection scans in Monkey Z (n=33 scans). Value on the y-axis represents the t-score, across scans, of the hemispheric asymmetry in the correlation with the global signal (contralateral > ipsilateral) averaged within each of the indicated areas. Each data point corresponds to an ROI, labeled as in panel (b). Error bars indicate standard error. For a description of the classification of projections into “weak/none” and “strong” categories, please refer to the Supplementary Methods.

To what extent does this regionalization match the specific pattern of afferent projections originating in the basal forebrain? To address this question, we performed an area-by-area comparison of hemispheric fMRI global signal asymmetry versus the extent of known afferent input from basal forebrain subregion Ch4al. We used the cytoarchitectonic parcellation of the brain offered in the digital version of the Saleem and Logothetis macaque atlas (Reveley et al., 2016) to identify multiple areas whose strength of anatomical projection from nucleus basalis subregion Ch4al has been characterized in one or more anatomical retrograde tracer studies in the macaque (see Mesulam and Van Hoesen, 1976; Mesulam et al., 1983; Doty 1983; Aggleton et al., 1987; Boussaoud et al., 1992; Mrzljak and Goldman-Rakic, 1993; Rosene 1993; Webster et al., 1993; Ghashghaei and Barbas, 2001; Gattass et al., 2014). We divided cortical areas into those receiving weak or no input, and those receiving strong input from Ch4al (details provided in Supplementary Methods). Figure 4c shows that the anatomical projection strength to a given cortical area is, for most areas, a good predictor of whether or not inactivation of Ch4al alters the hemispheric balance of spontaneous fMRI fluctuations within that area. In general, cortical regions receiving strong anatomical projections from Ch4al exhibited higher contralateral, versus ipsilateral, global signal correlation strength following inactivation. By contrast, the limbic structures, whose input from the basal forebrain is from more anteromedial regions, had more balanced hemispheric amplitudes, and in some cases elevated global signal on the side of injection. Three outlier areas, FST, IPa and TPO in the superior temporal sulcus, did not match the published anatomical projection strength, and the reason for this discrepancy is unknown. It is important to point out that the determination of cortical afference from multiple retrograde anatomical injections is neither precise nor comprehensive; nevertheless, we found a striking agreement between these two measures. The most parsimonious interpretation is that the spatial pattern of global signal suppression following inactivation of a NBM subregion derives from the temporary removal of input through its long range cortical projections.

Impact of basal forebrain inactivation on resting-state networks

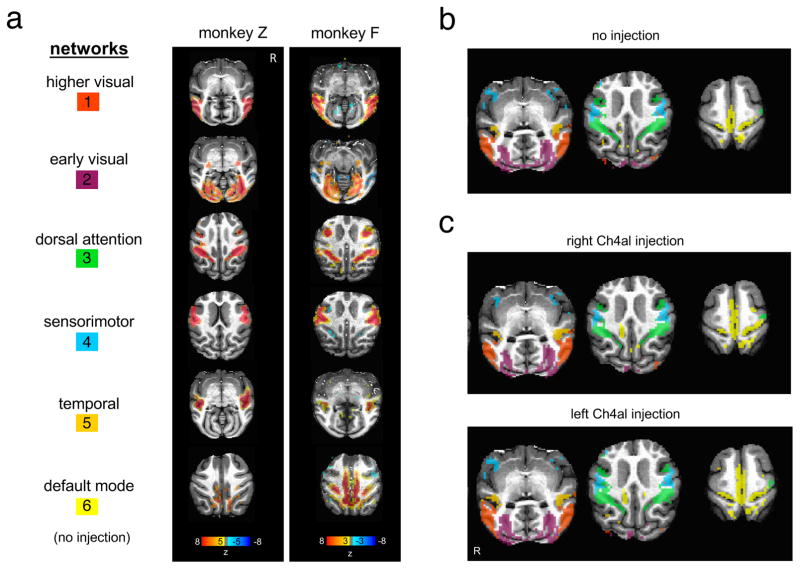

Given the profound influence of basal forebrain input on global resting state fMRI signals, we next investigated the role of the nucleus basalis in directing more specific patterns of inter-areal correlations, such as those comprising intrinsic networks investigated through methods such as independent component analysis (ICA). Intrinsic networks defined by their distinct spontaneous time courses have previously been demonstrated in humans (Fox and Raichle, 2007; Hutchison et al., 2013) and monkeys (Vincent et al., 2007; Hutchison et al., 2011; Mantini et al., 2011). Given the prominent ipsilateral decrease in the magnitude of the global signal, we asked whether Ch4al or Ch4am inactivation would also disrupt these ICA-defined networks, either in their basic layout or in their bilateral symmetry.

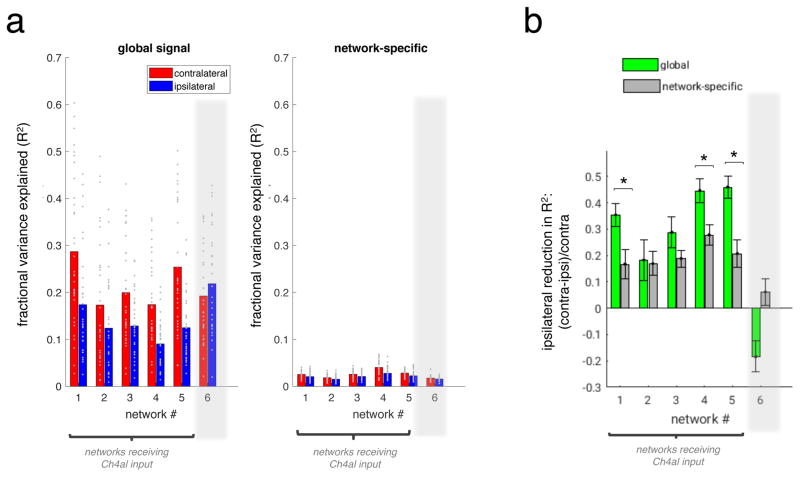

As a starting point, we used control data (i.e., no injection) to extract well-known ICA networks from resting state scans (Figure 5a,b). We identified six commonly studied networks (higher visual, early visual, dorsal attention, sensorimotor, temporal, and default-mode) in monkeys Z and F, which in both animals closely resembled those reported previously in the macaque (Hutchison and Everling, 2012). We then examined sessions in which nucleus basalis subregions had been inactivated, asking whether the prominent changes in global spontaneous activity affected the basic structure of these intrinsic networks. To our surprise, and in contrast to the major influence of NBM inactivation on the global signal components, the spatial layouts of these functional connectivity networks were virtually unaffected (Figure 5c, S6). These networks, which were extracted from the same sessions as those showing strong global signal asymmetry above, were normal in appearance and nearly bilaterally symmetric. Quantification of the results within the identified networks demonstrated the much stronger effect of inactivation on the global signal component (Figure 6). Results were similar following inactivation of either the Ch4al or Ch4am regions of the basal forebrain (Figure S5), with the spatial organization of the intrinsic networks remaining intact. The only observed change was an alteration of network strength ipsilateral to the inactivation that was statistically significant yet smaller than the magnitude of asymmetry exhibited by the global signal (Figure 6b, Figure S5b,c). The specific pattern of correlation-based networks exhibited the same basic topology following local inactivation, suggesting that the fMRI signal components contributing to the definition of intrinsic networks does not depend strongly on input from the basal forebrain.

Figure 5. Preservation of resting-state networks despite NBM inactivation.

(a) Control sessions from both monkeys (no BF injection). Using independent component analysis, we identified six components (“networks”) that closely resemble patterns reported in previous literature. (b) Control session networks obtained from dual regression displayed in different colors. (c) Same networks identified after injection of the NBM. Maps of individual networks were created by averaging, for each network, the dual-regression weights (β) across scans of the same condition (NBM injection site). To form the composite map shown here, each voxel was assigned to the network having the highest value at that voxel, and the resulting image was binarized at β = 0.004 (details in Supplementary Methods).

Figure 6. Comparison between global and network-specific effects of NBM injection.

(a) Fractional variance explained (R2) for global signal time courses (left) and network-specific time courses (right), averaged within the boundaries of symmetric ROIs corresponding to each of the 6 resting-state networks depicted in Figure 5a. Bar height corresponds to mean, and each dot indicates one scan (N=33, all Ch4al sessions of Monkey Z). Note that only networks 1–5 receive input from Ch4al, whereas network 6 is extrinsic to Ch4al projection zones. To derive R2 values for network-specific signals, we first orthogonalized each dual-regression network time course to the remaining network time courses prior to taking its (marginal) R2 with the fMRI data. (b) Quantification of the asymmetry in R2 between contralateral and ipsilateral hemispheres, expressed as a proportion of the contralateral value. Error bars indicate standard error. Asterisks indicate network ROIs wherein the hemispheric asymmetry of R2 is significantly greater in the global signal compared to the network-specific signal (at p<0.05, Bonferroni-corrected).

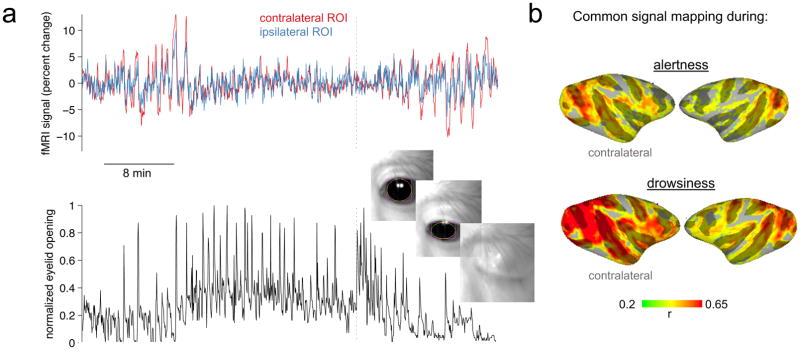

Behavioral arousal gates basal forebrain contribution to global signal

Given the known relationship between the basal forebrain and arousal, we next examined whether the regional fMRI signal suppression following Ch4al and Ch4am inactivation was dependent on the animal’s state of wakefulness. As in a previous study (Chang et al., 2016), we approximated arousal level through measurement of spontaneous eye opening and closing, which allowed us to define epochs of drowsiness and alertness in the data (see Supplementary Methods). We were thus able to determine whether the hemispheric asymmetry in the amplitude of spontaneous fluctuations was constant and continuous, or whether it was restricted to periods of either high or low arousal level.

Dividing the data in this way revealed a clear relationship between arousal level and the effect of basal forebrain inactivation on spontaneous fMRI signal fluctuations. As shown in Figure 7, the amplitude of fMRI fluctuations increased in both hemispheres during periods of overt drowsiness compared to alertness, consistent with previous reports (Fukunaga et al., 2006; Larson-Prior et al., 2009; Chang et al., 2013). Importantly, hemispheric disparity in the amplitude of fluctuations increased markedly during periods of low arousal (Figure 7a), which was again most evident when mapped onto the cortical surface in the form of a correlation with the global signal (Figure 7b). Permutation testing indicated that the degree of global-signal asymmetry is significantly greater during drowsiness than alertness, even when normalizing for the higher overall levels of fMRI signal fluctuation amplitude during drowsiness (p=0.02 Ch4al left-hemisphere, monkey Z; p=0.035 Ch4al left-hemisphere, monkey F; p=0.014 Ch4al right-hemisphere, monkey F; see Supplementary Methods, and see Figure S7 for quantification of resting-state networks). The results underscore the close relationship between the basal forebrain input, cortical excitability, global signal fluctuations, and the state of behavioral arousal. Future studies with concurrent electrophysiology, fMRI, and behavioral measures will invite deeper investigation into this relationship.

Figure 7. Influence of NBM input depends on behavioral arousal state.

Following inactivation, the hemispheric asymmetry in fMRI signal fluctuation amplitude, and in the global signal, was more pronounced during periods of apparent drowsiness compared to alertness. (a) Time series taken from symmetric positions in the occipital cortex during a scan following left-hemisphere NBM injection in Ch4al (monkey Z). The lower panel indicates, for the same time interval, an estimate of behavioral arousal based on eyelid opening and closure. (b) Maps of correlation with the global signal during conditions of probable alertness and drowsiness.

DISCUSSION

The consistent pattern of spontaneous fMRI correlation across the brain is one of the most influential discoveries in human neuroscience in the last two decades. Functional connectivity analysis, and the characterization of correlational networks, has been used to study diverse aspects of brain organization and disease. At the same time, the origination and physiological principles at the root of these spontaneous fluctuations have not been satisfactorily identified. A particularly vexing issue has been how to think about broadly shared synchronous fluctuations, sometimes termed the “global” signal. Within a given voxel, both broadly shared and regionally specific components are superimposed within the spontaneous time course. The present findings demonstrate that while the global signal strongly depends on input from the basal forebrain, the spatial structure of correlated resting-state networks derives primarily from alternate sources. In the following sections, we discuss the manner in which the basal forebrain orchestrates shared spontaneous fluctuations, the relationship of basal forebrain modulation to arousal and cognition, and the potential sources underlying intrinsic networks.

Nucleus basalis origin of shared cortical fluctuations

Our data suggest that the basal forebrain plays a special role in determining correlated fMRI signal fluctuations, likely owing to its unique, widespread cholinergic and GABAergic projections to all known cortical regions. These projections are often considered to be modulatory, and in that sense different in nature from many other types of long-range connections to the cortex. This difference is apparent when comparing the present results to those from a study in which another forebrain structure, the amygdala, is reversibly inactivated. The amygdala also sends long-range connections to a range of cortical areas, but its cortical projections are primarily excitatory and glutamatergic. In a recent study, Grayson and colleagues examined changes to spontaneous fMRI activity following reversible inactivation of the amygdala (Grayson et al., 2016). They found that, in contrast to the present findings, inactivation had a major impact on intrinsic networks in which the amygdala directly participated. While that study did not specifically examine the effects on the shared, global signal, the nature of the specific network disruption appeared fundamentally different from our findings. A straightforward explanation is that, owing to its unique anatomical projections, the NBM is a broadly reaching source of neuromodulation rather than a canonical network element within a particular functional circuit.

At the same time, an important aspect of the current findings is that different subregions of the nucleus basalis exerted regional specificity in their control of the shared, global cortical signal. The two subregions we tested (Ch4al and Ch4am), whose projections targets are largely distinct, appear to regulate global signal amplitude in almost non-overlapping portions of the cerebral cortex. Moreover, the effects of inactivation were expressed unilaterally, with a relative suppression ipsilateral to the injection site. Following inactivation, there was a broad but circumscribed region, or “hole”, of diminished global signal amplitude within the injected hemisphere. This hole was not present in the contralateral hemisphere, was most obvious when the two hemispheres were directly compared, and demonstrates that basal forebrain control over the global signal component is itself regional in nature. It is important to point out that the injections diminished but did not completely eliminate the global signal even in this hole. As we estimate that roughly one fifth of corticopetal basal forebrain neurons were affected by a given injection, one possible explanation for this is that unaffected divergent NBM projections from subregions flanking the injection site might have continued to drive cortical tissue in this area. Other possibilities include coordinated sources of neuromodulation stemming from other brain regions, such as from the brainstem reticular formation (see Parvizi and Damasio, 2003), or a somewhat weaker entrainment through connections from other cortical regions that retained their modulation through uninjected portions of the NBM. Whether a complete inactivation of the NBM would entirely eliminate these global fluctuations, and thus indicate that it was is the principal or sole driver of global resting state activity, is a difficult question that remains a topic for future investigation.

Nonetheless, the present study helps to shed new light on the mechanisms of coordinated signal fluctuations: to date, there has been little evidence to suggest that the topographic basal forebrain projections to the cortex are key drivers of the global fMRI signal. Our observation of repeatable and regionally specific fluctuations of the global signal controlled from neurons within small volume of basal forebrain strongly suggests a mechanism whereby global signal fluctuations stem from common input through long-range anatomical projection.

Survival of specific resting state networks

One of the striking findings in the present study was the minimal disruption of cortical resting state networks, despite strong, site-specific, ipsilateral disruption of the global cortical signal. Independent component analysis revealed that the standard family of functional networks retained their organization and spatial extent after the injection. This set of observations strongly suggests that the strongest version of our original hypothesis, that the NBM orchestrates activity across the cortex to determine the structure of resting state networks, cannot be correct. Instead, it is primarily the global signal component, shared across the entire cortex, that can be ascribed to input from the basal forebrain.

This result may be important for interpreting prodromal changes in spontaneous fMRI activity among patient groups. For example, in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, the nucleus basalis appears to be central to observed neuropathological changes (Braak and Braak, 1991a & 1991b; Emre et al., 1993; Baker-Nigh et al., 2015). Recent structural and fMRI studies also suggest that mapping both volumetric changes and functional connectivity of the nucleus basalis has predictive value for the progression of this disease (Cantero et al., 2016; Li et al., 2014; Cai et al., 2015). Our findings suggest that the specific influence of the nucleus basalis on fMRI activity depends on the behavioral state, thus the functional integrity of the basal forebrain might best be tested in a drowsy state, with a focus on the regional expression of the global spontaneous fMRI fluctuations. While cholinergic therapy in its present form is largely palliative (but see also Lahmy et al., 2013; Fisher et al., 2016), and less effective due to the nature of signaling through this pathway (Gritton et al., 2016), it is possible that considering patients in a drowsy state, and focusing on the global signal component, might allow for earlier non-invasive detection of basal forebrain dysregulation, prior to observable structural changes, opening the door for earlier treatment strategies as they arise.

In making this distinction between network vs. global signal effects, our findings invite deeper consideration of the mechanisms that may underlie coherent, regionally specific correlations among the resting state networks. These networks by definition, involve the existence of fMRI components that are selectively shared between certain brain areas. In practice, these selective correlations generally yield bilaterally symmetrical patterns, particularly in the monkey where hemispheric asymmetry is less prominent than in the human. The derived patterns of functional connectivity bear resemblance to known neuroanatomical projections (see Van Dijk et al., 2010; Buckner et al., 2013; Foster et al., 2016, for review). There is considerable overlap between spontaneous BOLD signal correlations and specific anatomic networks as revealed by retrograde tracer injections (Lewis and Van Essen, 2000; Vincent et al., 2007; Margulies et al., 2009), and studies comparing diffusion imaging and fMRI indicate a degree of correspondence at the level of the whole brain (Hagmann et al., 2008; Honey et al., 2009). However, anatomical projections alone cannot explain the correlational patterns characterized as functional connectivity, since selective activity correlations can also arise in structures that share no direct projections. Some evidence suggests that such correlations may arise from polysynaptic connections (Krienen and Buckner, 2009; Johnston et al., 2008). Computational modeling further suggests that neural/propagation dynamics and noise can further shape the pattern observed correlations (Deco et al., 2009; Ghosh et al., 2008; Honey et al., 2007). Through the present experiments, however, we cannot completely exclude the possibility of a direct NBM contribution to network correlations. While the spatial structure of networks was apparently unaltered, the magnitude did exhibit a small but significant hemispheric asymmetry (Figure S5). One possibility is that the observed asymmetry arises trivially from the presence of an asymmetric common signal that cannot be completely dissociated from the network signal with ICA and regression-based methods; another possibility is that correlated network activity in fact contains a contribution from NBM input, either directly to the nodes of resting-state networks or via the propagation of global NBM input on the anatomic connections that shape resting-state networks. Future studies, perhaps taking the approach of systematically inactivating nodes in a known functional network (Grayson et al., 2016), may help to understand the neural origins of these spontaneous correlations, which have come to play such a prominent role in both basic and clinical neuroscience.

Our findings may have some relevance to the procedure of ‘global signal regression’, i.e., projecting out the whole-brain average time series from each voxel’s signal as a preprocessing step for fMRI data (Murphy and Fox, 2017). Here, we did not directly examine the consequences of global signal regression on network characteristics, as we had used an ICA/dual-regression approach. Nonetheless, our results support the presence of a spatially widespread (“global”) signal component of neural origin and which may arise from mechanisms largely distinct from those driving the correlated activity within intrinsic networks. The amplitude of global fluctuations affected by NBM injection was higher during states of lower arousal, consistent with previous literature (e.g., Horovitz et al., 2008, Wong et al., 2013). However, the present study does not address the optimal procedure for separating global neuromodulatory activity from intrinsic network activity, and the interplay between global and network-specific activity remains an open question. Importantly, the sources contributing to the whole-brain average fMRI signal within a given scan can differ across individuals and populations (Power et al., 2017), as can the degree to which the global mean approximates a common additive signal of either neural or artifactual origin. When possible, it is recommended to measure and model the influence of specific processes, such as respiration/cardiac activity and fluctuating arousal levels, which can provide more clearly-defined signals of interest (or no interest) than can the global average fMRI signal. Our work also highlights the notion that widespread fMRI signals may carry information about brain function (e.g. Yang et al., 2014, Schölvinck et al., 2010), implying that regressing out a whole-brain average signal could remove important neural features.

Finally, we also note that the present study used ICA as the basis for delineating intrinsic functional networks. In the future, complementary techniques – including the powerful and flexible modeling approaches of networks science (e.g., Power et al., 2011; Rubinov and Sporns 2011; Bassett and Sporns 2017) - could be leveraged to gain additional insight into the effects of focal perturbations on large-scale functional interactions.

STAR★METHODS

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Guidelines established by the Institute of Laboratory Animal Research, and approved by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC), were followed for all experimental procedures.

Animals and housing

Two female rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta, 4.5 – 5.5 kg, ages 4 – 5 years at the start of the experiment) participated in this study. Both subjects were socially housed, each with a different female conspecific companion, in light (fixed 12hr light/dark cycle), temperature and humidity controlled rooms. They received meals of primate chow, nuts and fruits, and had access to water ad libitum; their health was routinely monitored by veterinary staff.

METHOD DETAILS

Local targeting

Precise targeting of the intracerebral injections was achieved using a grid system, described in detail elsewhere (Talbot et al., 2012). Briefly, the monkeys were anesthetized and surgically implanted, using aseptic techniques, with a G10 headpost and either a customized rectangular chamber (52mm × 32mm) or cylindrical chambers (Crist Instruments), made of Ultem®. Following a two-week recovery interval, high-resolution T1-weighted whole-brain anatomical scans (0.5-mm isotropic) were obtained to map the grid and target brain structures (4.7T Bruker scanner, Modified Driven Equilibrium Fourier Transform [MDEFT] sequence). The chamber(s) were filled with a dilute gadolinium solution (Magnevist, Berlex Pharmaceuticals; 1:1200 v:v in sterile saline, pH 7.0–7.5), and we inserted the appropriate guide grid into the chamber to visualize the grid holes (see Talbot et al., 2012). Target coordinates were confirmed in a subsequent scan session with local infusions of sterile dilute gadolinium contrast agent (up to 2.5 μl of a 5mM solution, Asthagiri et al., 2011); this contrast agent was included for each of the functional injection scanning sessions (see Figure 1a, b).

Transient inactivation

Reversible inactivations were achieved by infusing muscimol (18mM–44mM, 1.8–2.46 μl, sterile filtered, Rusmin et al., 1975) into the Ch4al/id/iv subregion of the basal forebrain (hereafter referred to as Ch4al), as well as Ch4am subregions in the awake animal. The microinfusions were performed over multiple days, with a single infusion (targeting one BF subregion in one hemisphere) per day, and no more than one intracerebral infusion per week.

Resting-state fMRI data acquisition

Following each infusion, 3 – 5 resting-state fMRI scans were acquired. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed with a 4.7 T/60 cm vertical scanner (Bruker BioSpec 47/60), using a custom-built transmit-receive RF coil (width 90 mm). This coil provided the highest signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in the occipital lobe, with a gradient of decreasing SNR in more anterior areas. A T1 contrast structural scan [MDEFT sequence] was acquired in 7.5 min in order to confirm the injection location. The contrast agent included in the injection caused local signal enhancement. The structural spatial resolution is 0.5 mm in-plane and 1.5mm in slice thickness.

Monocrystalline iron oxide nanoparticles (MION) were administered intravenously prior to fMRI acquisition, serving as a T2* contrast agent that isolates the regional cerebral blood flow (rCBV) component of the hemodynamic response and provides higher contrast-to-noise ratio than that of the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal. Functional MRI data were acquired using single-shot echo planner imaging (EPI) with parameters TR = 2.5 s, TE = 14 ms (for monkey Z; 14.3 ms for monkey F), and voxel size = 1.5 mm isotropic. Forty two (42) sagittal slices covered the whole brain; the field of view was 96 mm along anterior-posterior direction, and 51 mm for monkey Z (57 mm for monkey F) along head-foot direction. Unwanted signal from tissues below the brain was suppressed by spatial saturation pulses. Each scan consisted of 720 volume acquisitions (30 min), and 3–5 scans were acquired for each experimental session. During the fMRI scans, monkeys sat in near-complete darkness, and no monitor screen was present. An infrared video camera (sampling rate of 29.97 Hz) inside the bore was focused on the monkey’s face, clearly showing one eye, and this data were used to determine the extent to which the eyes remained open or closed throughout the scan (details in Modulation of effects by arousal state, below).

DATA ANALYSIS

Pre-processing of fMRI data

Unless otherwise specified, pre-processing steps were carried out using routines from the AFNI/SUMA software package (http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni). Each scan underwent slice-timing correction, correction for static magnetic field inhomogeneities using the PLACE algorithm (Xiang and Ye, 2007), motion coregistration, and between-session spatial registration to a single EPI reference scan. The first seven time frames of each scan were discarded for T1 stabilization, followed by removal of low-order temporal trends (polynomials up to the 5th order) and spatial smoothing to 2-mm isotropic resolution. Skull-stripping was carried out using the ‘bet’ function in FSL (Smith, 2002). The time series of each voxel was converted to units of percent signal change by subtracting, and then dividing by, the mean intensity at each voxel over the scan.

Surface and flat maps were generated using a combination of the AFNI and CARET (Van Essen et al., 2001) software packages. The high-resolution anatomy volume was skull stripped and normalized using AFNI and then imported into CARET. Within CARET, surface and flattened maps were generated from a white matter mask, and exported to SUMA for viewing.

Atlas-based regions of interest

To define regions of interest (ROIs) for fMRI data analysis, we used a digital atlas that provides neuroanatomic parcellation of the macaque brain based on the Saleem and Logothetis atlas (as discussed in Reveley et al., 2016), in the coordinate space of the macaque brain on which they were defined (monkey ‘D99’). To apply this atlas to the data of monkeys Z and F, we aligned the structural image of monkey D99 to the respective high-resolution structural images of monkeys F and Z using a series of affine and nonlinear registration steps described in (Reveley et al., 2016), and resampled its dimensions to match the native (EPI image) space. The reverse transformation was also calculated to enable displaying results from monkeys Z and F in a common (D99) space, as in Figure 4. Analysis of regional time course properties (Figure 2) was performed in the native image space of each monkey; ROI time courses were formed by averaging the time courses of all voxels falling within the boundaries of the ROI in the aligned, resampled D99 atlas. ROIs were excluded from analysis if they contained fewer than 5 voxels falling within the EPI spatial mask of both monkeys (described below).

Assessment of global spontaneous fluctuations

To examine the impact of BF inactivation on the distribution of shared spontaneous fluctuations, we constructed a reference regressor (“global signal”) by averaging the fMRI time courses of voxels contained within a broad mask spanning the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala. This spatial mask was defined from the union of all atlas regions in the D99 Atlas spanning the aforementioned areas, excluding voxels with insufficient signal-to-noise ratio (defined as those for which the ratio of the temporal standard deviation to the temporal mean within a reference EPI scan exceeded a threshold; a threshold of 18 was chosen by visual inspection, as this value appeared to exclude voxels with probable partial-volume effects from CSF and large vessels). For each scan, we calculated the percentage of temporal variance (R2) explained by this global signal in the time course of every voxel in the brain. The resulting maps were averaged across scans of a given experimental condition (Figure 3a–c). To further examine the hemispheric asymmetry in shared fluctuations, we separately calculated the average fMRI signal of each hemisphere within the spatial mask described above, and took the difference (contralateral minus ipsilateral to injection; or left minus right in scans with no injection) between these two signals. The difference signal was mapped on a voxel-wise basis (Figure 3d–f).

Since BF injections were performed in only one hemisphere per session, we examined whether shared spontaneous fluctuations exhibited an asymmetry between the cerebral hemispheres. Specifically, we subtracted the Fisher-z-transformed correlations with the global signal between approximately symmetric locations in the two hemispheres (contralateral minus ipsilateral), obtaining a map that reveals region-dependent global signal suppression across the ipsilateral hemisphere. Maps corresponding to the same injection target (Ch4al or Ch4am) were entered into a t-test, pooling left- and right-hemisphere injection scans of the associated site. For this analysis, we obtained approximately corresponding locations across hemispheres by spatially aligning – via nonlinear warping – a subject’s high-resolution structural image onto a left-right flipped version of this image, and applying these alignment parameters to the functional maps.

The relationship between global component asymmetry and anatomical projection strength shown in (Figure 4c), represents information pooled from studies using retrograde tracer injections in the macaque (see Mesulam and Van Hoesen, 1976; Mesulam et al., 1983; Doty 1983; Aggleton et al., 1987; Boussaoud et al., 1992; Mrzljak and Goldman-Rakic, 1993; Rosene 1993; Webster et al., 1993; Ghashghaei and Barbas, 2001; Gattass et al., 2014). In the study by Mesulam and colleagues (1983), the relative contributions of each of 8 basal forebrain subregions (Ch1, Ch2, Ch3, Ch4am, Ch4id, Ch4iv, Ch4al and Ch4p) were reported as percentages of all neurons labeled by the retrograde tracer within the basal forebrain, as well as the hypothalamus. We used this information to designate areas with low levels of labeling (“weak/none”, indicating <10% of total labeled neurons) and those with stronger contributions (“strong”, indicating >10% labeled neurons). As the degree to which different groups saturated particular recipient cortical fields with retrograde tracers varied considerably, this scaling is not intended as a comprehensive survey of the projection strengths from specific basal forebrain subregions.

Delineation of intrinsic networks

Intrinsic functional networks were derived using the dual regression technique (Filippini et al., 2009). This approach enables corresponding networks to be assessed in distinct scan sessions or subjects. First, spatial maps corresponding to canonical resting-state networks were obtained by applying independent component analysis (ICA) across the control scans for which no injection was performed. Multi-session ICA was carried out using FSL ‘melodic’ (https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/MELODIC) with temporal concatenation and a model order of 40. Six of the resulting components could be readily identified as intrinsic networks reported in previous literature: (1) primary visual (2) high-order visual (3) dorsal attention network (4) somatomotor (5) temporal (6) default-mode. Next, the spatial maps of all 40 components were entered together into a multiple regression, along the spatial dimension, against the fMRI data for each scan. This step yielded a set of 40 time courses, which were then entered into a multiple regression against the fMRI data along the temporal dimension, yielding a set of 40 spatial maps. Maps corresponding to the six networks of interested were extracted, where the values in these maps (regression weights, β) reflect the expression of each network in a given scan. Maps displayed in Figure 5 were created by averaging corresponding networks across scans of the same condition (BF injection site). To form the composite maps, each voxel was assigned to the network having the highest value at that voxel, and the image was binarized at β = 0.004 (monkey Z, Figure 5) and β = 0.008 (monkey F, Figure S5). To quantify inter-hemispheric differences in network strength, the average of the voxel-wise dual-regression weights was calculated separately for the left and right hemispheres, within the boundaries of the network. These network boundaries were defined as supra-threshold within the associated ICA component (from the 40-component decomposition of the control data), where a threshold of z=5 was used for all networks.

For confirmation, we also performed multi-session ICA (temporal concatenation; without dual regression) separately for each condition, obtaining similar results (Figure S6). This provided critical assurance that the similarity of networks under BF injection does not arise from the use of the same (control-condition) networks as the basis for dual regression. For the maps in Figure S6, a mixture-modeling threshold of 0.5 was used (Beckmann et al., 2004).

Modulation of effects by arousal state

Epochs of high and low arousal were defined based on the video recordings of the monkeys’ eye behavior. From these videos, we created a waveform indicating the degree to which the eyes were open or closed over time. This was calculated by extracting the height of a bounding box around the pupil at each movie frame and taking its median value within the time bin corresponding to each volume acquisition (TR) of the fMRI data, yielding a time series sampled at the same rate as the fMRI data. This time series was subsequently normalized by the maximum value within the session, corresponding to the eye being fully open, such that the units were rendered comparable across sessions despite slight variations in the positioning of the camera relative to the eyes.

Using this behavioral arousal time series, we defined epochs of probable high and low arousal state with the following approach. Starting from the beginning of a scan, we slid a window of 1-min duration (24 TRs) across the scan, with a step size (shift) of one TR. For each window, if the number of time points below 0.5 (eye half closed) exceeded the number of time points above 0.5, all points within the window are designated as belonging to the drowsy state; otherwise, they are designated as belonging to the alert state. Note that because of the overlap between sliding time windows, time points may change their state assignment as the window moves forward in time. To account for hemodynamic delays in the corresponding fMRI data, state assignments were shifted forward by 5 s (2 TRs).

Maps of voxel-wise correlations with the global signal were recomputed separately for each of the two putative arousal states, as shown in Figure 7. We then conducted permutation tests to formally assess whether the hemispheric asymmetry is indeed significantly more pronounced during the drowsy condition. A laterality (or asymmetry) index for the global-signal correlation maps in each of the two conditions was calculated as follows. Let denote the average correlation with the global signal across all voxels in the hemisphere hem and in state state, where hem is either contra (contralateral to BF injection) or ipsi (ipsilateral to BF injection) and state is either “d” (drowsy) or “a” (alert). We can define the quantities

to reflect the asymmetry of global signal in each of these conditions, and summarize the difference between conditions as

After calculating this index D for the true partitioning of data into states (i.e., based on the eye behavior), we then permuted the state assignments across the data through successive circular shifts by 20 TRs per iteration, thereby preserving the temporal structure of the partitions. The laterality indices (and their difference) were computed for each of these permuted state assignments, providing in a null distribution to which we could compare the ‘true’ difference in laterality. Since eye-behavior recordings for 3 sessions of monkey Z (corresponding to inactivation of the Ch4al subregion in the right hemisphere) were unavailable, these sessions were excluded from the analysis of arousal-state dependence. We also excluded scans for the Ch4am inactivation sessions in monkey F from this analysis, as eyes remained closed throughout all scans.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Inactivation of the nucleus basalis decreased ipsilateral global fMRI fluctuations

Reduction of global signal was strongest in known cortical projection targets

Nucleus basalis inactivation had minimal effect on resting-state fMRI networks

Effects of inactivation on fMRI were most pronounced during periods of low arousal

Acknowledgments

Functional and anatomical MRI scanning was carried out in the Neurophysiology Imaging Facility Core (NIMH, NINDS, NEI). This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health (ZIAMH002896 and ZICMH002899). I.E.M. was supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Biological Technologies Office (BTO) ElectRx program under the auspices of Dr. Eric Van Gieson through the CMO Grant/Contract No.HR0011-16-2-0022 and the National Institute of Mental Health under Award Number R01MH110594. We thank Katy Smith, Charles Zhu for experimental assistance; Paul Taylor, Richard Reynolds, and Daniel Glen for advice regarding AFNI software tools, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

Additional information, including 7 figures, is available online with this article at http://…

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, J.T., C.C., C.R.C., J.H.D., F.Q.Y. and D.A.L.; Methodology, J.T., C.C., F.Q.Y.; Investigation, J.T., C.C., F.Q.Y., B.E.R., D.Y.; Writing – Original Draft, J.T., C.C., F.Q.Y, D.A.L; Writing – Review & Editing, J.T., C.C. I.E.M., D.A.L; Funding Acquisition, D.A.L.; Resources, D.A.L., J.H.D.; Supervision, D.A.L, J.H.D.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aggleton JP, Friedman DP, Mishkin M. A comparison between the connections of the amygdala and hippocampus with the basal forebrain in the macaque. Exp Brain Res. 1987;67:556–568. doi: 10.1007/BF00247288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asthagiri AR, Walbridge S, Heiss JD, Lonser RR. Effect of concentration on the accuracy of the convective imaging distribution of a gadolinium-based surrogate tracer. J Neurosurgery. 2011;115:467–473. doi: 10.3171/2011.3.JNS101381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Nigh A, Vahedi S, Davis EG, Weintraub S, Bigio EH, Klein WL, Geula C. Neuronal amyloid-β accumulation within cholinergic basal forebrain in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2015;138:1722–1737. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv024. http://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awv024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett DS, Sporns O. Network Neuroscience. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:353–364. doi: 10.1038/nn.4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann CF, Smith SM. Probabilistic Independent Component Analysis for Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2004;23:137–152. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.822821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussaoud D, Desimone R, Ungerleider LG. Subcortical connections of visual areas MST and FST in macaques. Vis Neurosci. 1992;9:291–302. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800010701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Alzheimer’s disease affects limbic nuclei of the thalamus. Acta Neuropathologica. 1991a;81:261–268. doi: 10.1007/BF00305867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathologica. 1991b;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer F. Cerveau isolé et physiologie du sommeil. CR Soc Biol Paris. 1935;118:1235–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Krienen FM, Yeo BT. Opportunities and limitations of intrinsic functional connectivity MRI. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:832–837. doi: 10.1038/nn.3423. http://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai S, Huang L, Zou J, Jing L, Zhai B, Ji G, von Deneen KM, Ren J, Ren A the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Changes in thalamic connectivity in the early and late stages of amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a resting-state functional magnetic resonance study from ADNI. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0115573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115573. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantero JL, Zaborszky L, Atienza M. Volume loss of the nucleus basalis of Meynert is associated with atrophy of innervated regions in mild cognitive impairment. Cereb Cortex. 2016:1–9. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw195. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhw195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chang C, Leopold DA, Schölvinck ML, Mandelkow H, Picchioni D, Liu X, Ye FQ, Turchi JN, Duyn JH. Tracking brain arousal fluctuations with fMRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:4518–4523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520613113. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1520613113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Liu Z, Chen MC, Liu X, Duyn JH. EEG correlates of time-varying BOLD functional connectivity. Neuroimage. 2013;72:227–236. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LM, Yang PF, Wang F, Mishra A, Shi Z, Wu R, Wilson GH, 3rd, Ding Z, Gore JC. Biophysical and neural basis of resting state functional connectivity: Evidence from non-human primates. Mag Res Imaging. 2017;39:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2017.01.020. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2017.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damoiseaux JS, Rombouts SA, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, Stam CJ, Smith SM, Beckmann CF. Consistent resting-state networks across healthy subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13848–13853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601417103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deco G, Martí D, Ledberg A, Reig R, Sanchez Vives MV. Effective reduced diffusion-models: a data driven approach to the analysis of neuronal dynamics. PLoS Computational Biol. 2009;5:e1000587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000587. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disney AA, Reynolds JH. Expression of m1-type muscarinic acetylcholine receptors by parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons in the primary visual cortex: a comparative study of rat, guinea pig, ferret, macaque, and human. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522:986–1003. doi: 10.1002/cne.23456. http://doi.org/10.1002/cne.23456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RW. Nongeniculate afferents to striate cortex in macaques. J Comp Neurol. 1983;218:159–173. doi: 10.1002/cne.902180204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emre M, Heckers S, Mash DC, Geula C, Mesulam M-M. Cholinergic innervation of the amygdaloid complex in the human brain and its alterations in old age and Alzheimer’s disease. J Comp Neurol. 1993;336:117–134. doi: 10.1002/cne.903360110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippini N, MacIntosh BJ, Hough MG, Goodwin GM, Frisoni GB, Smith SM, Matthews PM, Beckmann CF, Mackay CE. Distinct patterns of brain activity in young carriers of the APOE-epsilon4 allele. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7209–7214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811879106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher A, Bezprozvanny I, Wu L, Ryskamp DA, Bar-Ner N, Natan N, Brandeis R, Elkon H, Nahum V, Gershonov E, LaFerla FM, Medeiros R. AF710B, an novel M1/σ1 agonist with therapeutic efficacy in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegener Dis. 2016;16:95–110. doi: 10.1159/000440864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster BL, He BJ, Honey CJ, Jerbi K, Maier A, Saalmann YB. Spontaneous neural dynamics and multi-scale network organization. Front Sys Neurosci. 2016;10:7. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2016.00007. http://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2016.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201. http://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga M, Horovitz SG, van Gelderen P, de Zwart JA, Jansma JM, Ikonimidou VN, Chu R, Deckers RH, Leopold DA, Duyn JH. Large-amplitude, spatially correlated fluctuations in BOLD fMRI signals during extended rest and early sleep stages. Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:979–992. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2006.04.018. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattass R, Galkin TW, Desimone R, Ungerleider LG. Subcortical connections of area V4 in the macaque. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522:1941–1965. doi: 10.1002/cne.23513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghashghaei HT, Barbas H. Neural interaction between the basal forebrain and functionally distinct prefrontal cortices in the rhesus monkey. Neurosci. 2001;103:593–614. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00585-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Rho Y, McIntosh AR, Kötter R, Jirsa VK. Noise during rest enables the exploration of the brain’s dynamic repertoire. PLoS Computational Biol. 2008;4:e1000196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000196. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson DS, Bliss-Moreau E, Machado CJ, Bennett J, Shen K, Grant KS, Fair DA, Amaral DG. The rhesus monkey connectome predicts disrupted functional networks resulting from pharmacogenetics inactivation of the amygdala. Neuron. 2016;91:453–466. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.06.005. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritton HJ, Howe WM, Mallory CS, Hetrick VL, Berke JD, Sarter M. Cortical cholinergic signaling controls the detection of cues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E1089–E1097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516134113. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516134113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagmann P, Cammoun L, Gigandet X, Meuli R, Honey CJ, Wedeen VJ, Sporns O. Mapping the structural core of human cerebral cortex. PLoS One. 2008;6:e159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060159. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0060159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hangya B, Ranade SP, Lorenc M, Kepecs A. Central cholinergic neurons are rapidly recruited by reinforcement feedback. Cell. 2015;162:1155–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer L, Van Hoesen GW. The limbic lobe and its output channels: implications for emotional functions and adaptive behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:126–147. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.06.006. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillary FG, Grafman JH. Injured brains and adaptive networks: the benefits and costs of hyperconnectivity. Trends Cog Sci. 2017;21:385–401. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2017.03.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey CJ, Kötter R, Breakspear M, Sporns O. Network structure of cerebral cortex shapes functional connectivity on multiple time scales. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10240–10245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701519104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey CJ, Sporns O, Cammoun L, Gigandet X, Thiran JP, Meuli R, Hagmann P. Predicting human resting-state functional connectivity from structural connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2035–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811168106. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0811168106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horovitz SG, Fukunaga M, de Zwart JA, van Gelderen P, Fulton SC, Balkin TJ, Duyn JH. Low frequency BOLD fluctuations during resting wakefulness and light sleep: a simultaneous EEG-fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2008;29:671–682. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison RM, Everling S. Monkey in the middle: why non-human primates are needed to bridge the gap in resting-state investigations. Front Neuroanat. 2012;6:29. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2012.00029. http://doi.org/10.3389/fnana.2012.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison RM, Leung LS, Mirsattari SM, Gati JS, Menon RS, Everling S. Resting-state networks in the macaque at 7 T. Neuroimage. 2011;56:1546–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.063. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison RM, Womelsdorf T, Gati JS, Everling S, Menon RS. Resting-state networks show dynamic functional connectivity in awake humans and anesthetized macaques. Hum Brain Mapping. 2013;34:2154–77. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22058. http://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JM, Vaishnavi SN, Smyth MD, Zhang D, He BJ, Zempel JM, et al. Loss of resting interhemispheric functional connectivity after complete section of the corpus callosum. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6453–6458. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0573-08.2008. http://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0573-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitt CA, Mitchell SJ, DeLong MR, Wainer B, Price DL. Fiber pathways of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in monkeys. Brain Res. 1987;406:192–206. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90783-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krienen FM, Buckner RL. Segregated fronto-cerebellar circuits revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:2485–97. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp135. http://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhp135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahmy V, Meunier J, Malmström S, Naert G, Givalois L, Kim SH, Villard V, Vamvakides A, Maurice T. Blockade of Tau hyperphosphorylation and Aβ1-42 generation by the aminotetrahydrofuran derivative AVANEX2-73, a mixed muscarinic and σ1 receptor agonist, in a non-transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;38:1706–1723. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson-Prior LJ, Zempel JM, Nolan TS, Prior FW, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME. Cortical network functional connectivity in the descent to sleep. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009 Mar;106:4489–4494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900924106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledbetter NM, Chen CD, Monosov IE. Multiple mechanisms for processing reward uncertainty in the primate basal forebrain. J Neurosci. 2016;36:7852–7864. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1123-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold DA, Maier A. Ongoing physiological processes in the cerebral cortex. NeuroImage. 2012;62:2190–2200. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.059. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JW, Van Essen DC. Corticocortical conections of visual, sensorimotor, and multimodal processing areas in the parietal lobe of the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2000;428:112–137. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001204)428:1<112::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CS, Ide JS, Zhang S, Hu S, Chao HH, Zaborszky L. Resting state functional connectivity of the basal nucleus of Meynert in humans: in comparison to the ventral striatum and the effects of age. NeuroImage. 2014;97:321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.04.019. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SC, Brown RE, Hussain Shuler MG, Petersen CCH, Kepecs A. Optogenetic dissection of the basal forebrain neuromodulatory control of cortical activation, plasticity, and cognition. J Neurosci. 2015;35:13896–13903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2590-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magoun HW. An ascending reticular activating system in the brain stem. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1952;67:145–54. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1952.02320140013002. discussion 167–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantini D, Gerits A, Nelissen K, Durand JB, Joly O, Simone L, Sawamura H, Wardak C, Orban GA, Buckner RL, Vanduffel W. Default mode of brain function in monkeys. J Neurosci. 2011;31:12954–12962. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2318-11.2011. http://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2318-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies DS, Vincent JL, Kelly C, Lohmann G, Uddin LQ, Biswal BB, Villringer A, Castellanos FX, Milham MP, Petrides M. Precuneus shares intrinsic functional architecture in humans and monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20069–20074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905314106. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0905314106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LJ, Blackstone CD, Levey AI, Huganir RL, Price DL. Cellular localizations of AMPA glutamate receptors within the basal forebrain magnocellular complex of rat and monkey. J Neurosci. 1993;13:2249–2263. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-05-02249.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Levey AI, Wainer BH. Cholinergic innervation of cortex by the basal forebrain: cytochemistry and cortical connections of the septal area, diagonal band nuclei, nucleus basalis (substantia innominata), and hypothalamus in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1983;214:170–197. doi: 10.1002/cne.902140206. http://doi.org/10.1002/cne.902140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM, Van Hoesen GW. Acetylcholinesterase-rich projections from the basal forebrain of the rhesus monkey to neocortex. Brain Res. 1976;109:152–157. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90385-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metherate R, Cox CL, Ashe JH. Cellular bases of neocortical activation: modulation of neural oscillations by the nucleus basalis and endogenous acetylcholine. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4701–4711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-12-04701.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monosov IE, Leopold DA, Hikosaka O. Neurons in the primate medial basal forebrain signal combined information about reward uncertainty, value, and punishment anticipation. J Neurosci. 2015;35:7443–7459. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0051-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrzljak L, Goldman-Rakic PS. Low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor (p75NGFR)-and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)-immunoreactive axons in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus of adult macaque monkeys and humans. Cereb Cortex. 1993;3:133–147. doi: 10.1093/cercor/3.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro CE, Donovan NJ, Guercio BJ, Wigman SE, Schultz AO, Amariglio RE, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Marshall GA. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional connectivity in mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;46:727–735. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150017. http://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K, Fox MD. Towards a consensus regarding global signal regression for resting state functional connectivity MRI. Neuroimage. 2017;154:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauta W, Kuypers H. Some ascending pathways in the brain stem reticular formation. In: Jasper HH, Proctor LD, Knighton RS, Noshay WL, Costello RT, editors. Reticular formation of the brain. Boston, USA: Little Brown; 1958. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi J, Damasio AR. Differential distribution of calbindin D28K and parvalbumin among functionally distinctive sets of structures in the macaque brainstem. J Comp Neurol. 2003;462:153–167. doi: 10.1002/cne.10711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson RCA, Gatter KC, Brodal P, Powell TPS. The projection of the basal nucleus of Meynert upon the neocortex in the monkey. Brain Res. 1983;259:132–136. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendl SL, Salzwedel AP, Goldman BD, Barrett LF, Lin W, Gilmore JH, Gao W. Emergence of a hierarchical brain during infancy reflected by stepwise functional connectivity. Hum Brain Mapping. 2017;38:2666–2682. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23552. http://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.23552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JD, Cohen AL, Nelson SM, Wig GS, Barnes KA, Church JA, Vogel AC, Laumann TO, Miezin FM, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron. 2011;72:665–678. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]