Abstract

Cell-free DNA screening for fetal aneuploidy is a commonly employed testing strategy in pregnancies at high risk for fetal aneuploidy. The use of cell-free DNA screening is expanding to the low risk population, as the detection rate for trisomy 21 surpasses that of traditional screening modalities. While the sensitivity and specificity of cell-free DNA are superior to traditional screening, false-positive results do occur and may indicate an adverse maternal health condition, including maternal mosaicism, or rarely, malignancy. The risk of maternal cancer when more than one aneuploidy is detected that is discordant from fetal genotype is significantly elevated. Given this risk, as well as the rising incidence of cancer in pregnancy, patient counseling and a malignancy evaluation should be considered in women when more than one aneuploidy is detected. We reviewed the published literature and developed an algorithm to evaluate women when these results are identified.

Aneuploidy Screening With Cell-Free DNA

In 2011, use of cell-free DNA was introduced as a commercial screening option for aneuploidy When aneuploidy detected on cell-free DNA is discordant from fetal karyotype, the etiologies may vary. Placental mosaicism and vanishing twins are common causes, with confined placental mosaicism occurring in 1/1065 pregnancies, and vanishing twins accounting for 40% of discordant positive cell-free DNA results in one study.1 However, because maternal DNA is also sequenced, cell-free DNA allows for identification of maternal health conditions. These may include maternal copy number variants (CNVs), maternal mosaicism for aneuploidy, or maternal malignancy.

Discordant Cell-Free DNA Results and Malignancy

In a case series from 2015, 3757 samples from a cohort of 125,426 cell-free DNA results were positive for aneuploidy.2 Of these, 10 cases of maternal malignancy were diagnosed. Seven of these cases were among the 39 patients with more than one aneuploidy detected, translating to a maternal malignancy incidence of 18% among women with more than one aneuploidy detected. In a second cohort of a total of 113,415 samples, in which 37 women had more than one aneuploidy detected and 65 had single autosomal monosomies detected, there was a 19% rate of malignancy in women with more than one aneuploidy discordant from fetal karyotype, and a 4% rate of malignancy in women with single autosomal monosomies.3 Of the 10 described cases of malignancy associated with aneuploid results,2 4 cases of lymphoma, and 1 case each of leukemia, unspecified adenocarcinoma, leiomyosarcoma, colorectal cancer, anal cancer, and neuroendocrine cancer were identified. For 8 of these women, cell-free DNA was further examined with genome-wide analysis. These analyses revealed CNVs spanning multiple chromosomes, reflecting gains and losses across the entire genome. A second case series was described in which women underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) following abnormal cell-free DNA results with CNVs concerning for malignancy; in this series of 3 asymptomatic women, 1 woman was found to have ovarian cancer and 2 were found to have lymphoma.4

While ACOG continues to advocate for the use of conventional screening methods as the first-line screen in the general obstetric population,5 cell-free DNA screening is increasingly being expanded to low-risk populations. The recommendation to screen low and high risk women with cell-free DNA was endorsed by the American College of Medical Genetics.6 With expanded application of this test, more discordant results will inevitably be identified. As such, an algorithm should be developed to aid in the evaluation of patients when more than one aneuploidy is detected that is discordant from fetal karyotype. Our purpose is to provide, through case illustration, an algorithm that can be applied in practice. This algorithm was developed jointly between maternal fetal medicine providers, a prenatal genetic counselor, and a medical oncologist. A literature search was performed to inform this discussion; PubMed searches performed using search terms “cancer pregnancy,” “malignancy pregnancy,” “gestational cancer,” “gestational malignancy,” “cell-free DNA malignancy,” “cell-free DNA cancer,” “cell-free DNA pregnancy cancer,” and “cell-free DNA malignancy cancer” yielded the references cited within this discussion. This project was reviewed and deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Case

A 35 year old Caucasian gravida 2 para 1001 presented for care at 9 weeks of gestation. She was healthy with one prior term delivery, and a medical history notable only for recently diagnosed asthma. She underwent aneuploidy screening with cell-free fetal DNA via the massively parallel shotgun sequencing platform at 12 weeks. Her cell-free DNA results returned screen positive for trisomy 21 and possible monosomy 13. The reporting laboratory added a clinical note to the report stating that bioinformatics review of genome wide data revealed multiple additional aneuploidies, similar to the patterns that had previously been reported in cases of maternal malignancy.

She then met with a genetic counselor and discussed possible etiologies of this result, including (1)fetal trisomy 21 with placental mosaicism for monosomy 13, (2)partial trisomy 21 with partial monosomy 13 resulting from an unbalanced translocation, (3)a chromosomally normal fetus with placental mosaicism for both trisomy 21 and monosomy 13, (4)maternal medical condition, including possible malignancy, and (5)unknown. She chose to undergo an amniocentesis at 15 weeks gestation to evaluate the fetal karyotype which was found to be normal. She was therefore was referred for maternal fetal medicine consultation.. Her history was notable for a recent diagnosis of asthma with persistent cough, hoarseness with vocal cord paralysis seen on endoscopy, mid-back, and left arm size greater than right (attributed to carrying her child primarily on the left side). Physical exam was otherwise notable only for mild hepatomegaly.

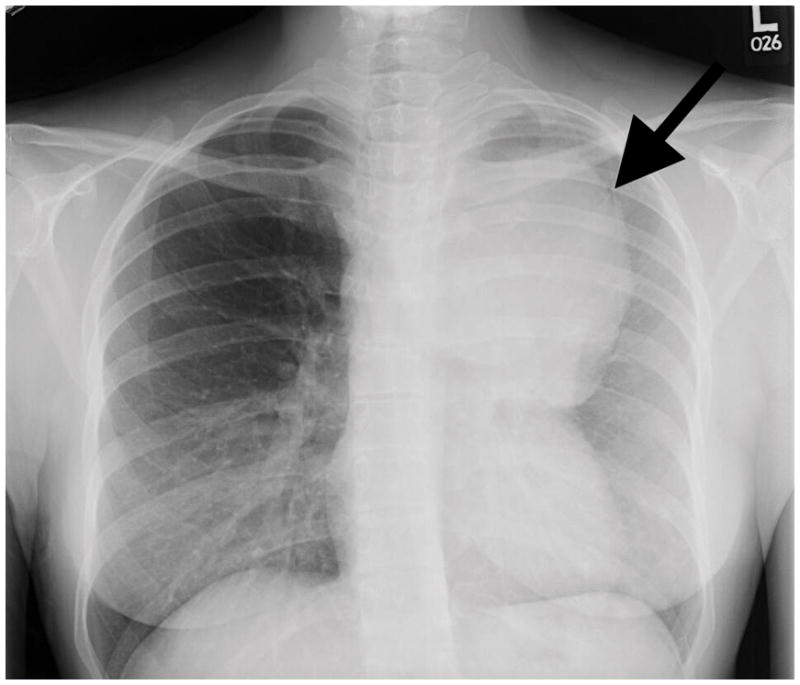

Evaluation was undertaken with a complete blood count (CBC), metabolic panel (CMP), stool guaiac, and chest X-ray. The CBC and CMP were normal. Chest x-ray was notable for a large, left-sided, anterior mediastinal mass (Figure 1). Chest computerized tomography (CT) scan confirmed the mediastinal mass, showing severe extrinsic compression and obstruction of the left upper lobe pulmonary artery and left upper lobe bronchus, invasion of the mediastinum and extension beyond the thoracic inlet to displace the trachea and thyroid. Left-sided pleural metastases were visualized, as well as a right pulmonary nodule suspicious for metastasis. Differential diagnosis at that time included invasive thymoma, thymic carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, and lymphoma.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray demonstrating large anterior mediastinal mass (arrow).

The patient was referred for thoracic oncology consultation. Biopsy revealed an atypical thymic carcinoid tumor, stage IVb. She opted for induced abortion, and subsequently underwent treatment with cisplatin, etoposide, and radiation therapy. Her disease did not respond, and she is currently being treated with Lanreotide, a somatostatin analog, as her tumor expresses abundant somatostatin receptors.

Cancer in Pregnancy

Cancer is the 2nd leading cause of death in women aged 20–39 in the United States7 and malignancy complicates approximately 1 in 1000 to 1500 pregnancies.8,9 The most common malignancies in pregnancy include melanoma, breast cancer, thyroid cancer, colon cancer, cervical cancer, ovarian cancer, and hematologic malignancies.8,10

Aneuploidy and Cell-Free DNA in Oncology Patients

The link between cancer and genetic changes is well-established, and the use of cell-free DNA to identify cancer characteristics via a ‘liquid biopsy’ for screening, prognosis and surveillance has been receiving increasing attention. Rapidly growing tissues, including tumors, undergo apoptosis at increased rates, releasing DNA into the circulation. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA is used in many types of cancer to evaluate for disease burden, recurrence, and presence or absence of mutations to aid in guiding therapy.11 Circulating DNA has been illustrated to have good test characteristics as a screening tool in the identification of patients with non-small cell lung cancer.12 Additionally, mosaic aneuploidy in peripheral blood is associated with an increased risk of both a current cancer and a future cancer diagnosis. In a large case-control study, mosaicism was more common in individuals with solid tumors than in cancer-free individuals; additionally, when identified a year prior to diagnosis, those with leukemia had increased odds of mosaicism with odds ratio of 35.4 when compared to leukemia-free individuals.13 This would imply that the risk for malignancy, particularly hematologic malignancy, persists over time. This finding was confirmed in a second cohort that identified a 10-fold increased risk of future hematologic cancer diagnosis in individuals with detectable clonal mosaicism.14

Malignancy Evaluation

Given the high prevalence (as high as 19%) of cancer in women with more than one aneuploidy detected via cell-free DNA discordant from fetal karyotype,2,3 a malignancy evaluation is warranted. If the laboratory performing the cell-free DNA screening does not initially report genome-wide data on their report, it may be of benefit in triaging patients for the provider to contact the laboratory and request that this data be unblinded to determine whether additional aneuploidies are detected. The genetic counselor employed by the performing laboratory should be able to provide the clinician with this information. In our case, the performing laboratory reported erratic signals from all chromosomes on the genome wide analysis, increasing suspicion for maternal malignancy. Screening for malignancy in pregnant women should focus on those malignancies most commonly identified in reproductive age women and should utilize screening tests that are minimally invasive and cost-effective.

A systematic approach should be utilized to guide a thorough evaluation of these patients (Box 1). A complete history and physical exam are suggested as an initial step to guide further evaluation, including a comprehensive review of systems. The clinician should inquire about fatigue, night sweats, and unintentional weight loss, though these symptoms may overlap with common complaints of early pregnancy. Family history should be closely examined to identify whether increased risk for familial cancer syndromes may be present. Specifically, degree of affected relative, age of cancer onset, ancestry, and any genetic testing results should be solicited. Comprehensive exam should include a thorough evaluation of the skin, oropharynx, neck, thyroid, breast, lung, and abdomen, as well as a pelvic and rectal exam. Any atypical-appearing nevi warrant biopsy and dermatology evaluation. Palpable breast masses or atypical or unilateral nipple discharge would raise concern for breast cancer. Thyromegaly or nodules may be seen with thyroid cancer. Generalized lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly may raise suspicion for hematologic malignancies; in 3 of 4 women diagnosed with lymphoma in the above-described case series, presentation was with a palpable mass.4 Pelvic exam should include a pap smear if one has not recently been done as cervical cancer is the third most common malignancy found in pregnancy.10

Box 1. Stepwise Evaluation of the Patient With More Than One Aneuploidy Detected on Cell-Free DNA.

-

Discuss results with performing laboratory

-

History and physical examination with laboratory evaluation

CBC with peripheral smear

CMP

Pap smear

-

Fecal occult blood

-

Chest X-ray

-

MRI chest, abdomen, and pelvis

Consider annual CBC for surveillance

In the absence of other findings, we would suggest performing a CBC with peripheral smear and a CMP including liver function testing. Leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, or atypical leukocytes would trigger further evaluation. Screening for fecal occult blood is an inexpensive and noninvasive screening modality for colorectal cancer, with sensitivity of approximately 61.5–79.4%.15 While it is not specific for colorectal cancer and may identify other conditions including hemorrhoids or inflammatory bowel disease, it may be preferred in pregnancy over endoscopic examination in the absence of symptoms to minimize anesthesia exposure. A chest x-ray is also recommended to evaluate for lung and mediastinal lesions. Should this evaluation be negative, MRI of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis should be considered. MRI without contrast has not been associated with adverse neonatal or childhood outcomes16 and does not result in radiation exposure, and as such, is generally preferred to CT.. In children with genetic conditions which place them at high risk for development of cancer, MRI was found to have excellent sensitivity with 100% negative predictive value17; additionally, 3 of the previously described cases detected after concerning cell-free DNA results were identified by MRI. Thus, in this high risk population, MRI could have significant utility in identifying preclinical disease.

In the absence of exam, lab, or radiographic findings, the patient should be reassured regarding her risk for malignancy at the incident time; however, she should also be counseled that her risk, particularly for hematologic malignancy, persists. Given that many of the patients with malignancies identified following abnormal cell-free DNA results have been affected with hematologic malignancies, and that risk of development of leukemia persists years after findings of aneuploidy on cell-free DNA in non-pregnant population,14 these findings should be conveyed to the patient’s primary care provider for ongoing risk assessments. Until further prospective studies have been done, consideration should be made for annual CBC with differential for surveillance.

Discussion

We propose an evaluation for women when more than one aneuploidy is detected, given the high prevalence of malignancy in this population. Results consistent with a single autosomal monosomy carry a 4% risk of malignancy.3 This prevalence is based on small numbers, only 1 patient having malignancy in this series.. These patients should be cautiously counseled on this finding; shared decision making between the clinician and patient should guide any further evaluation.

Notably, many women with these results will not have a malignancy, and the above counseling and screening can promote significant anxiety and resource utilization. Incidental findings may be noted during the evaluation without notable health implications, though these can cause stress and further resource utilization. However, until larger prospective studies are available to more completely describe the frequency and etiology of malignancy in these women, the above-described evaluation seems reasonable.

Further prospective studies are needed to better elucidate malignancy risk, both in terms of frequency and in primary sites most commonly affected. This information would improve counseling when these results are received and allow for a more targeted evaluation.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NICHD BIRCWH K12 Grant HD001441 (Drs. Boggess and Vora); K23 HD088742 (Dr. Vora)

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has indicated that he or she has met the journal’s requirements for authorship.

Presented as poster at the International Conference on Prenatal Diagnosis and Therapy, San Diego, CA, 9–12 July 2017.

References

- 1.Cuckle H, Benn P, Pergament E. Cell-free DNA screening for fetal aneuploidy as a clinical service. Clin Biochem. 2015;48(15):932–941. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianchi DW, Chudova D, Sehnert AJ, et al. Noninvasive Prenatal Testing and Incidental Detection of Occult Maternal Malignancies. JAMA. 2015;314(2):162–169. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snyder HL, Curnow KJ, Bhatt S, Bianchi DW. Follow-up of multiple aneuploidies and single monosomies detected by noninvasive prenatal testing: implications for management and counseling. Prenat Diagn. 2016;36(3):203–209. doi: 10.1002/pd.4778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amant F, Verheecke M, Wlodarska I, et al. Presymptomatic Identification of Cancers in Pregnant Women During Noninvasive Prenatal Testing. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(6):814–819. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cell-free DNA screening for fetal aneuploidy. Committee Opinion No. 640. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e31–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gregg AR, Skotko BG, Benkendorf JL, et al. Noninvasive prenatal screening for fetal aneuploidy, 2016 update: a position statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med. 2016;18(10):1056–1065. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dotters-Katz S, McNeil M, Limmer J, Kuller J. Cancer and pregnancy: the clinician’s perspective. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2014;69(5):277–286. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pentheroudakis G, Pavlidis N. Cancer and pregnancy: poena magna, not anymore. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(2):126–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith LH, Dalrymple JL, Leiserowitz GS, Danielsen B, Gilbert WM. Obstetrical deliveries associated with maternal malignancy in California, 1992 through 1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(7):1504–1512. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.114867. discussion 1512–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diaz LA, Jr, Bardelli A. Liquid biopsies: genotyping circulating tumor DNA. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(6):579–586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang T, Zhai C, Su C, Ren S, Zhou C. The diagnostic value of circulating cell free DNA quantification in non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Lung Cancer. 2016;100:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs KB, Yeager M, Zhou W, et al. Detectable clonal mosaicism and its relationship to aging and cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44(6):651–658. doi: 10.1038/ng.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laurie CC, Laurie CA, Rice K, et al. Detectable clonal mosaicism from birth to old age and its relationship to cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44(6):642–650. doi: 10.1038/ng.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knudsen AB, Zauber AG, Rutter CM, et al. Estimation of Benefits, Burden, and Harms of Colorectal Cancer Screening Strategies: Modeling Study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(23):2595–2609. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Bharatha A, Montanera WJ, Park AL. Association Between MRI Exposure During Pregnancy and Fetal and Childhood Outcomes. JAMA. 2016;316(9):952–961. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anupindi SA, Bedoya MA, Lindell RB, et al. Diagnostic Performance of Whole-Body MRI as a Tool for Cancer Screening in Children With Genetic Cancer-Predisposing Conditions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205(2):400–408. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]