Abstract

Nanocrystalline Fe2O3 thin films are deposited directly on the conduct substrates by pulsed laser deposition as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. We demonstrate the well-designed Fe2O3 film electrodes are capable of excellent high-rate performance (510 mAh g− 1 at high current density of 15,000 mA g− 1) and superior cycling stability (905 mAh g− 1 at 100 mA g− 1 after 200 cycles), which are among the best reported state-of-the-art Fe2O3 anode materials. The outstanding lithium storage performances of the as-synthesized nanocrystalline Fe2O3 film are attributed to the advanced nanostructured architecture, which not only provides fast kinetics by the shortened lithium-ion diffusion lengths but also prolongs cycling life by preventing nanosized Fe2O3 particle agglomeration. The electrochemical performance results suggest that this novel Fe2O3 thin film is a promising anode material for all-solid-state thin film batteries.

Keywords: Lithium-ion batteries, Nanocrystalline Fe2O3, Anode material

Background

With the ever-increasing applications of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) in portable electronics and electric vehicles, there has been extensive research on developing advanced electrode materials with higher energy and power densities [1–7]. Since the first report on reversible lithium storage in transition metal oxides (TMOs) by Poizot et al. [8], TMOs (Co3O4 [9, 10], NiO [11, 12], Fe2O3 [13–15], and CuO [16, 17]) have been widely explored as anode materials due to their higher theoretical specific capacity and better safety in comparison with traditional carbon anode materials. Among all these TMOs, Fe2O3 received much attention in recent years due to its high theoretical specific capacity (~ 1005 mAh g− 1), low cost, abundant resources, and environmental benignity. However, like other TMOs, the huge volume variations associated with Li-ion insertion/extraction often leads to the pulverization and subsequent falling off of the active materials from the electrode, which results in a significant capacity fade, poor cycling stability, and poor rate capability. To circumvent these problems, many nanostructures of Fe2O3 have been synthesized for lithium-ion batteries, such as nanorods [18, 19], nanoflakes [20, 21], hollow sphere [22–24], core-shell arrays [25], and micro-flowers [26].

Besides all the above nanostructures, nanocrystalline thin film anodes (NiO [27], MnO [28], Cr2O3 [29], CoFe2O4 [30], Si [31], and Ni2N [32]) deposited directly on conducting substrates by pulsed laser deposition or sputtering can also exhibit an excellent electrochemical performance due to the enhanced electrical contact between the substrates and active materials, the shortened diffusion lengths for lithium-ion, and the structure stability. What is more important is that thin films of TMOs have potential applications in all-solid-state microbatteries as self-supported electrodes [33, 34]. The TMOs’ films can replace the lithium film anode which limits the integration of microbatteries with circuits due to the low melting point and strong reactivity with moisture and oxygen. However, up to now, there have been few reports on the Fe2O3 film anodes deposited by pulsed laser deposition or sputtering, and the reported specific capacities were much lower than the theoretical specific capacity of Fe2O3 [35, 36].

In this work, we prepared nanocrystalline Fe2O3 films by pulsed laser deposition (PLD) as an anode material for lithium-ion batteries. The Fe2O3 thin film anodes with average grain size of several tens of nanometers showed high reversible capacity of 905 mAh g− 1 at 100 mA g− 1 and high rate capacity of 510 mAh g− 1 at 15000 mA g− 1. The remarkable electrochemical performance demonstrates that nanocystalline Fe2O3 thin film has potential applications in high performance LIBs, especially all-solid-state thin film batteries.

Experimental

Synthesis of Nanocrystalline Fe2O3 Films

The films of Fe2O3 were deposited directly on copper foils or stainless steels by a PLD technique in oxygen ambient. A KrF excimer laser with a wavelength of 248 nm was focused on the rotatable target of metal Fe. The repetition rate was 5 Hz, and the laser energy was 500 mJ. The distance between the target and the substrate was 40 mm. In order to get nanocrystalline Fe2O3 films, we grew samples at room temperature under oxygen pressure of 0.3 Pa on both copper foil and stainless steels. They showed the same electrochemical performance. The thickness of the nanocomposite film is approximately 200 nm as determined by atomic force microscope (AFM, Park systems XE7). The mass of 0.121 mg was obtained by measuring the difference of substrate before and after deposition via electrobalance (METTLER TOLEDO).

Material Characterization

The crystalline phase of the Fe2O3 film was characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) on a Rigaku D/Max diffractometer with filtered Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) at a voltage of 40 kV and a current of 40 mA. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and selected area electron diffraction (SEAD) were carried out by a JEOL 100CX instrument. For the TEM measurement, the Fe2O3 film grown on NaCl substrate was put into water to dissolve the NaCl. After that, the suspension was dropped onto a holey carbon grid and dried. The morphology of the samples were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a SU8010. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurement was performed on a Thermo Scientific ESCALAB 250XI photoelectron spectrometer.

Electrochemical Measurements

For the electrochemical measurements, conventional CR2032 type coin cells with the Fe2O3 nanocrystalline film anodes were assembled inside an argon-filled glove box with the oxygen and moisture content below 0.1 ppm. The electrochemical cells were prepared using lithium metal as the counter electrode and a standard electrolyte of 1:1:1 ethylene carbonate (EC)/dimethyl carbonate (DMC)/LiPF6. Galvanostatic cycling measurements were processed at room temperature by a LAND-CT2001A battery system at various current rates between 0.01 and 3.0 V. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) and AC impedance measurements were performed with a CHI660E electrochemical workstation (CHI Instrument TN). The scanning rate was 0.1 mV s− 1.

Results and Discussion

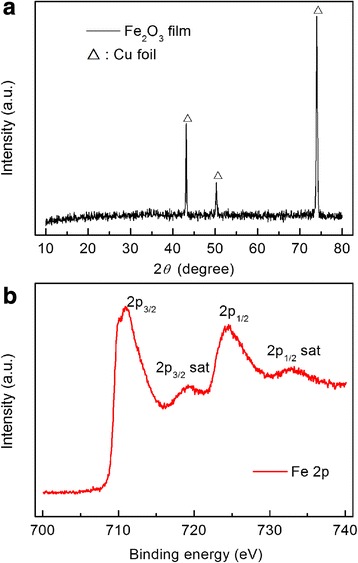

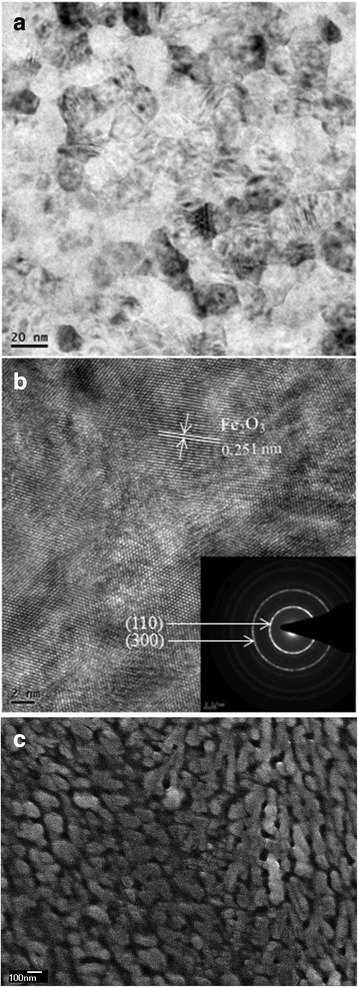

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the Fe2O3 film are shown in Fig. 1a. It can be observed that there is no obvious peak except the peaks of cubic crystal Cu substrate, suggesting that the Fe2O3 film is amorphous or crystallized with nanosized grains. Such phenomenon could be attributed to the deposition occurred at room temperature. In order to determine the chemical composition of the obtained film, XPS measurement was performed as shown in Fig. 1b. The Fe 2p3/2 and Fe 2p1/2 main peaks are clearly accompanied by satellite structures on their high binding-energy side, with a relative shift of about 8 eV. The peaks of Fe 2p3/2 locating at 710.9 eV and Fe 2p1/2 locating at 724.5 eV are similar with XPS spectra of Fe2O3 reported in the literature [37–39]. To further reveal the structure and composition of as-deposited thin films, TEM characterization was conducted as shown in Fig. 2. It revealed that the Fe2O3 films were made of small nanograins with average size of several tens of nanometers. The HRTEM image clearly presents the lattice fringes of the (110) corresponding to d-spacing of 0.251 nm of α-Fe2O3. Meanwhile, the ring-like feature of the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) confirmed the polycrystalline nature of Fe2O3 film. As shown by the SEM images in Fig. 2c, the Fe2O3 film consists of particles in nanometer scale. Based on all these results, we can confirm that the film deposited at room temperature is composed of Fe2O3 with ultrafine nanosized crystalline grains.

Fig. 1.

Structure and composition characterization of Fe2O3 film deposited at room temperature. a XRD patterns of Fe2O3 film. b XPS spectrum of Fe2O3 film

Fig. 2.

a TEM image. b HRTEM image with inset showing SAED patterns. c SEM image of the Fe2O3 film prepared at room temperature

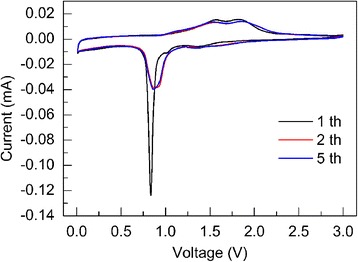

The electrochemical performance of the electrode made of Fe2O3 nanocrystalline film was firstly evaluated by cyclic voltammetry (CV). Figure 3 shows the first three CV curves of Fe2O3 nanocrystalline film anode. The CV curves are similar to the previous reports of Fe2O3 anode [40–46]. In the first cathodic process, three peaks were observed at 1.38, 1.02, and 0.84 V, which could be related to a multi-step reaction. First, the very small peak at 1.38 V may be due to the lithium insertion into the crystal structure of Fe2O3 film forming LixFe2O3 without change in the structure [40, 43]. Second, another peak at about 1.02 V could be ascribed to phase transition from hexagonal LixFe2O3 to cubic LiFe2O3. The third sharp reduction peak at 0.84 V corresponds to the complete reduction of iron from Fe2+ to Fe0 and the formation of solid electrolyte interface (SEI). In the anodic process, two broad peaks observed at 1.57 and 1.85 V represent the oxidation of Fe0 to Fe2+ and further oxidization to Fe3+. In the subsequent cycles, the reduction peaks were replaced by two peaks locating around 0.88 V because of the irreversible phase transformation in the first cycle. The overlapping of the CV curves during the following 2 cycles demonstrated good reversibility of the electrochemical reactions, and this was further confirmed by the cycling performance.

Fig. 3.

Cyclic voltammetry curves of the nanocrystalline Fe2O3 film. The curves were measured at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s− 1 from 0.01 to 3 V

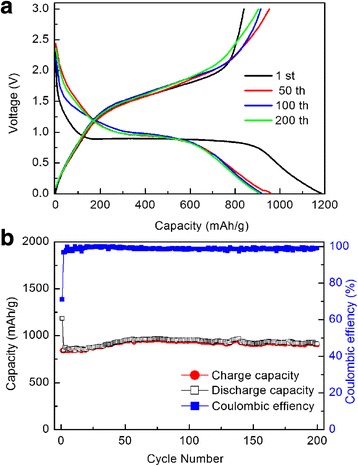

Figure 4a shows the discharge and charge profiles of the Fe2O3 nanocrystalline film for different cycles at a specific current of 100 mA g− 1 with a voltage range of 0.01–3 V. Obvious voltage hysteresis are observed due to the conversion reaction during charge/discharge processes, and the voltage plateaus are in good agreement with the above CV results. The clear voltage slopes observed in each charge/discharge process indicate the oxidation of Fe to Fe3+ and the reduction of Fe3+ to Fe, respectively. The smooth slope from 1.5 to 2.0 V in the charge process represents the two oxidation peaks in the CV curves. Meanwhile, the plateau or slope around 0.9 V in the discharge process represents the reduction peak in the CV curves. The initial discharge and discharge capacity of the Fe2O3 nanocrystalline film are 1183 and 840 mAh g− 1, respectively, resulting in a Coulombic efficiency of 71%. The irreversible capacity loss is mainly attributed to the formation of SEI layer on the surface of anode, which is commonly observed in most anode materials [44–47].

Fig. 4.

a Discharge-charge profiles of the nanocrystalline Fe2O3 film anode cycled between 0.01–3 V at a specific current of 100 mA g− 1. b Cycling performance of the nanocrystalline Fe2O3 film anode and corresponding Coulombic efficiencies at a specific current of 100 mA g− 1

The cycling performance of the film electrode at a specific current of 100 mA g− 1 at room temperature is shown in Fig. 4b. It can be seen that the reversible capacity gradually increases to 951 mAh g− 1 after the 70 cycles and then keeps stable in the range of 900–950 mAh g− 1 with a Coulombic efficiency nearly 100% during the following cycles. Similar phenomenon of the capacity increasing during cycling has been found in many transition metal oxide electrodes in previous studies [13, 48–52]. The possible reason for this would be the electrode activation, which induces the reversible growth of polymer/gel-like films to increase the capacity at low potentials [50]. Compared with the previous reports of Fe2O3 film anode batteries deposited by pulsed laser deposition or sputtering [35, 36], the capacity of Fe2O3 in our work has a considerable improvement as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The capacity comparison of our work with reported Fe2O3 film anode

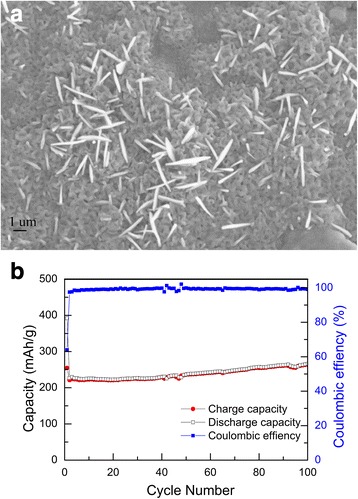

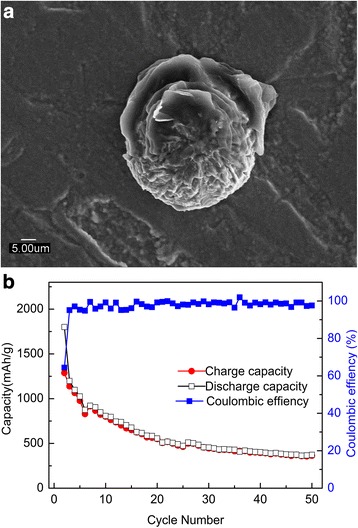

Previous studies on the effect of particle size on lithium intercalation into Fe2O3 shows that nanocrystalline Fe2O3 exhibited better electrochemical performance than macro-sized (> 100 nm) Fe2O3 [53]. To confirm the role of particle size in the electrochemical performance, we annealed the as-prepared Fe2O3 film on stainless steels at 400°. The prepared Fe2O3 film anode at high temperature was deposited on stainless steels only due to the instability of copper foil. The morphology comparison in Fig. 5a and Fig. 2c confirms that the particle sizes of the samples annealed at high temperature are obviously larger. Figure 5b shows that the capacities was only about 263 mAh g− 1 after 100 circles, which was much lower than the specific capacity of as-prepared Fe2O3. In addition, we also fabricated Fe2O3 film anode with larger particle size on stainless steels under 400 °C as shown in Fig. 6a. Figure 6b shows its discharge and charge profiles for different cycles at a specific current of 100 mA g− 1. The capacities dropped to 361 mAh g− 1 after 50 circles. These results indicate that the enhanced reversible capacity of nanocrystalline Fe2O3 film grown at room temperature can be attributed to the nanoscaled structure of the thin film electrode, which can sustain high lithium insertion strain because of the smaller number of atoms and large surface areas within nanoparticles [13, 14, 54].

Fig. 5.

a SEM image and b cycling performance of the Fe2O3 film anode annealed at 400 °C at a specific current of 100 mA g− 1

Fig. 6.

a SEM image and b cycling performance of the Fe2O3 film anode grown at 400 °C at a specific current of 100 mA g− 1

To investigate the kinetics of lithium inserting/deinserting, electrochemical impedance spectra measurement was performed in Fig. 7a. The charge-transfer impedance on the electrode/electrolyte surface is about 50 Ω, which can be deduced from the single semicircle in the high-middle frequency. The superior conductivity of the film electrode without binder can be attributed to the nanocrystalline structure of the Fe2O3 film and the enhanced electrical contact between active anode and substrate. The good conductivity of the nanocrystalline Fe2O3 film anode led to excellent rate performance. Figure 7b shows the charge/discharge capacities at different current densities. The anode delivered capacities up to 855, 843, 753, 646, and 510 mAh g− 1 at high current densities of 750, 1500, 3000, 7500, and 15,000 mA g− 1, respectively, which is corresponding to 98.2, 96.7, 87.8, 75.3, and 59.5% retention of the capacity at 250 mA g− 1 (about 871 mAh g− 1). More importantly, when the specific current reduced to 250 mA g− 1, the capacity could recover to 753 mAh g− 1. The excellent rate performance benefits from both the good conductivity of the anode and the increase of capacity upon cycling.

Fig. 7.

a Electrochemical impedance spectra of the nanocrystalline Fe2O3 film. b Rate capabilities of the nanocrystalline Fe2O3 film at different specific currents

Conclusions

In summary, nanocrystalline Fe2O3 film anode has been deposited by pulsed laser deposition at room temperature. The results of structure and morphology characterization showed that the deposited films are composed of nanocrystalline Fe2O3 with grain size of several tens of nanometers. The prepared Fe2O3 exhibits an excellent electrochemical performance, such as superior cycling stability (905 mAh g− 1 at a specific current of 100 mA g− 1 after 200 cycles) and high rate capability (510 mAh g− 1 at 15000 mA g− 1). The outstanding electrochemical performance can be related to the nanocrystalline structure of Fe2O3 which could sustain high strain, shorten diffusion lengths for lithium-ion, and keep the structure stable. The excellent electrochemical performance and room temperature growth suggest that nanocrystalline Fe2O3 has potential application in high performance LIBs, especially in all-solid-state thin film batteries.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Institute of Materials for Energy and Environment in Qingdao University for the technical assistance during TEM and SEM observations.

Funding

This work was supported partly by the National Sciences Foundation of China Nos. 11504192, 11674187, 11604172, 11704211; the National Science Foundation of Shandong Province BSB2014010, BS2015SF003; and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation 2015M570570.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data are fully available without restriction.

Abbreviations

- AFM

Atomic force microscope

- CV

Cyclic voltammetry

- DMC

Dimethyl carbonate

- EC

Ethylene carbonate

- LIB

Lithium-ion batteries

- PLD

Pulsed laser deposition

- SEAD

Selected area electron diffraction

- SEI

Solid electrolyte interface

- SEM

Scanning electron microscopy

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

- TMOs

Transition metal oxides

- XPS

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy

- XRD

X-ray diffraction

Authors’ Contributions

The experiments and characterization presented in this work were carried out by XLT, YZQ, XTS, and STF. The experiments were designed by QL and SDL. The experiments were discussed in the results by XW, HSL, JX, and DRC. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ Information

Not applicable

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiaoling Teng, Email: 1047745717@qq.com.

Youzhi Qin, Email: 991183430@qq.com.

Xia Wang, Email: wangxiakuaile@qdu.edu.cn.

Hongsen Li, Email: hsli@qdu.edu.cn.

Xiantao Shang, Email: 1781741842@qq.com.

Shuting Fan, Email: 959479438@qq.com.

Qiang Li, Email: liqiang@qdu.edu.cn.

Jie Xu, Email: xujie@qdu.edu.cn.

Derang Cao, Email: caodr@qdu.edu.cn.

Shandong Li, Email: lishd@qdu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Armand M, Tarascon JM. Building better batteries. Nature. 2008;451:652–657. doi: 10.1038/451652a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodenough JB, Kim Y. Challenges for rechargeable Li batteries. Chem Mater. 2010;22:587–603. doi: 10.1021/cm901452z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang Y, Zhang Y, Li W, Ma B, Chen XD. Rational material design for ultrafast rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:5926–5940. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00442F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li H, Peng L, Zhu Y, Chen D, Zhang X, Yu G. An advanced high-energy sodium ion full battery based on nanostructured Na2Ti3O7/VOPO4 layered materials. Energy Environ Sci. 2016;9:3399–3405. doi: 10.1039/C6EE00794E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Candelaria S, Shao Y, Zhou W, Li X, Xiao J, Zhang J, Wang Y, Liu J, Li J, Cao G. Nanostructured carbon for energy storage and conversion. Nano Energy. 2012;1(2):195–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2011.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X, Kim HM, Xiao Y, Sun YK. Nanostructured metal phosphide-based materials for electrochemical energy storage. J Mater Chem A. 2016;4:14915–14931. doi: 10.1039/C6TA06705K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li H, Ding Y, Ha H, Shi Y, Peng L, Zhang X, Ellison C, Yu G. An all-stretchable-component sodium-ion full battery. Adv Mater. 2017;29:1700898. doi: 10.1002/adma.201700898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poizot P, Laruelle S, Grugeon S, Dupont L, Tarascon JM. Nano-sized transition-metaloxides as negative-electrode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Nature. 2000;407:496–499. doi: 10.1038/35035045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Pan A, Zhu Q, Nie Z, Zhang Y, Tang Y, Liang S, Cao G. Facile synthesis of nanorod-assembled multi-shelled Co3O4 hollow microspheres for high-performance supercapacitors. J Power Sources. 2014;272:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.08.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Z, Ren W, Wen L, Gao L, Zhao J, Chen Z, Zhou G, Li F, Cheng H. Graphene anchored with Co3O4 nanoparticles as anode of lithium ion batteries with enhanced reversible capacity and cyclic performance. ACS Nano. 2010;4:3187–3194. doi: 10.1021/nn100740x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang D, Sun W, Chen Z, Zhang Y, Luo W, Jiang Y, Dou S. Two-dimensional cobalt-/nickel-based oxide nanosheets for high-performance sodium and lithium storage. Chem-Eur J. 2016;22:18060–18065. doi: 10.1002/chem.201604115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen W, Wu J, Cao M. Rapid one-step synthesis and electrochemical performance of NiO/Ni with tunable macroporous architectures. Nano Energy. 2013;2:1383–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2013.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang Y, Zhang D, Li Y, Yuan T, Bahlawane N, Liang C, Sun W, Lu Y, Yan M. Amorphous Fe2O3 as a high-capacity, high-rate and long-life anode material for lithium ion batteries. Nano Energy. 2014;4:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2013.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H, Zhou L, Yu C. Highly crystallized Fe2O3 nanocrystals on graphene: a lithium ion battery anode material with enhanced cycling. RSC Adv. 2014;4:495–499. doi: 10.1039/C3RA44891F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao D, Xiao Y, Wang X, Gao Q, Cao M. Ultra-high lithium storage capacity achieved by porous ZnFe2O4/alpha-Fe2O3 micro-octahedrons. Nano Energy. 2014;7:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2014.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu W, Zhao JC, Wang MZ, Hu YH, Chen LF, Xie HQ (2015) Thermal conductivity enhancement in thermal grease containing different CuO structures. Nanoscale Res Lett 10:113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Mai Y, Wang X, Xiang J, Qiao Y, Zhang D, Gu C, Tu J. CuO/graphene composite as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim Acta. 2011;56:2306–2311. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2010.11.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cherian CT, Sundaramurthy J, Kalaivani M, Ragupathy P, Kumar PS, Thavasi V, Reddy MV, Sow CH, Mhaisalkar SG, Ramakrishna S, Chowdari BVR. Electrospun alpha-Fe2O3 nanorods as a stable, high capacity anode material for Li-ion batteries. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:12198–12204. doi: 10.1039/c2jm31053h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S, Sun Y, Zhou F, Nan J. Improved electrochemical performance of alpha-Fe2O3 nanorods and nanotubes confined in carbon nanoshells. Appl Surf Sci. 2016;375:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.03.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy M, Yu T, Sow C, Shen Z, Lim C, Rao GVS, Chowdari BVR. Alpha-Fe2O3 nanoflakes as an anode material for Li-ion batteries. Adv Funct Mater. 2007;17:2792–2799. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200601186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang P, Han L, Genc A, He Y, Zhang X, Zhang L, Galan-Mascaros JR, Morante JR, Arbiol J. Synergistic effects in 3D honeycomb-like hematite nanoflakes/branched polypyrrole nanoleaves heterostructures as high-performance negative electrodes for asymmetric supercapacitors. Nano Energy. 2016;22:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.02.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang B, Chen J, Wu H, Wang Z, Lou X. Quasiemulsion-templated formation of alpha-Fe2O3 hollow spheres with enhanced lithium storage properties. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:17146–17148. doi: 10.1021/ja208346s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li C, Hu Q, Li Y, Zhou H, Lv Z, Yang X, Liu L, Guo H. Hierarchical hollow Fe2O3@MIL-101(Fe)/C derived from metal-organic frameworks for superior sodium storage. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25556. doi: 10.1038/srep25556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu W, Cui X, Liu X, Zhang L, Huang J, Piao X, Zhang Q (2013) Hydrothermal evolution, optical and electrochemical properties of hierarchical porous hematite nanoarchitectures. Nanoscale Res Lett 8:2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Luo Y, Luo J, Jiang J, Zhou W, Yang H, Qi X, Zhang H, Fan H, Yu DYW, Li C, Yu T. Seed-assisted synthesis of highly ordered TiO2@alpha-Fe2O3 core/shell arrays on carbon textiles for lithium-ion battery applications. Energy Environ Sci. 2012;5:6559–6566. doi: 10.1039/c2ee03396h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin S, Deng H, Long D, Liu X, Zhan L, Liang X, Qiao W, Ling L. Facile synthesis of hierarchically structured Fe3O4/carbon micro-flowers and their application to lithium-ion battery anodes. J Power Sources. 2011;196:3887–3893. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2010.12.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao L, Wang DX, Wang R. NiO thin films grown directly on Cu foils by pulsed laser deposition as anode materials for lithium ion batteries. Mater Lett. 2014;132:357–360. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2014.06.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cui Z, Guo X, Li H. High performance MnO thin-film anodes grown by radio-frequency sputtering for lithium ion batteries. J Power Sources. 2013;244:731–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2012.11.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khamlich S, Nuru ZY, Bello A, Fabiane M, Dangbegnon JK, Manyala N, Maaza M. Pulsed laser deposited Cr2O3 nanostructured thin film on graphene as anode material for lithium-ion batteries. J Alloy Compd. 2015;637:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.02.155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chu Y, Fu Z, Qin Q. Cobalt ferrite thin films as anode material for lithium ion batteries. Electrochim Acta. 2004;49:4915–4921. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2004.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jimenez AR, Klopsch R, Wagner R, Rodehorst UC, Kolek M, Nolle R, Winter M, Placke T. A step toward high-energy silicon-based thin film lithium ion batteries. ACS Nano. 2017;11:4731–4744. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b00922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma ZY, Zhang H, Sun X, Guo J, Li ZC. Preparation and characterization of nanostructured Ni2N thin film as electrode for lithium ion storage. Appl Surf Sci. 2017;420:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.05.139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou Y, Xue M, Fu Z. Nanostructured thin film electrodes for lithium storage and all-solid-state thin-film lithium batteries. J Power Sources. 2013;234:310–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2013.01.183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patil A, Patil V, Shin DW, Choi JW, Paik DS, Yoon SJ. Issue and challenges facing rechargeable thin film lithium batteries. Mater Res Bull. 2008;43:1913–1942. doi: 10.1016/j.materresbull.2007.08.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li W, Zhou Y, Fu Z. Nanocomposite Fe2O3-Se as a new lithium storage material. Electrochim Acta. 2010;55:8680–8685. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2010.07.095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarradin J, Guessous A, Ribes M. Synthesis and characterization of lithium intercalation electrodes based on iron oxide thin films. J Power Sources. 1996;62:149–154. doi: 10.1016/S0378-7753(96)02429-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mills P, Sullivan JL. A study of the core level electrons in iron and its three oxides by means of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J Phys D Appl Phys. 1983;16:723–732. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/16/5/005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McIntyre NS, Zetaruk DG. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopic studies of iron oxides. Anal Chem. 1977;49:1521–1529. doi: 10.1021/ac50019a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brundle CR, Chuang TJ, Wandelt K. Core and valence level photoemission studies of iron oxide surfaces and the oxidation of iron. Surf Sci. 1977;68:459–468. doi: 10.1016/0039-6028(77)90239-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun B, Horvat J, Kim HS, Kim WS, Ahn J, Wang GX. Synthesis of mesoporous alpha-Fe2O3 nanostructures for highly sensitive gas sensors and high capacity anode materials in lithium ion batteries. J Phys Chem C. 2010;114:18753–18761. doi: 10.1021/jp102286e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chou S, Wang J, Wexler D, Konstantinov K, Zhong C, Liu H, Dou S. High-surface-area alpha-Fe2O3/carbon nanocomposite: one-step synthesis and its highly reversible and enhanced high-rate lithium storage properties. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:2092–2098. doi: 10.1039/b922237e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu H, Wang G, Park J, Wang J, Liu H, Zhang C. Electrochemical performance of alpha-Fe2O3 nanorods as anode material for lithium-ion cells. Electrochim Acta. 2009;54:1733–1736. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2008.09.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qiu J, Li M, Zhao Y, Kong Q, Li X, Li C. Scalable synthesis of nanometric alpha-Fe2O3 within interconnected carbon shells from pyrolytic alginate chelates for lithium storage. RSC Adv. 2016;6:7961–7969. doi: 10.1039/C5RA21541B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song Y, Qin S, Zhang Y, Gao W, Liu J. Large-scale porous hematite nanorod arrays: direct growth on titanium foil and reversible lithium storage. J Phys Chem C. 2010;114:21158–21164. doi: 10.1021/jp1091009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang X, Liu HH, Petnikota S, Ramakrishna S, Fan HJ. Electrospun Fe2O3-carbon composite nanofibers as durable anode materials for lithium ion batteries. J Mater Chem A. 2014;2:10835–10841. doi: 10.1039/c3ta15123a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu J, Yin Z, Yang D, Sun T, Yu H, Hoster HE, Hng HH, Zhang H, Yan Q. Hierarchical hollow spheres composed of ultrathin Fe2O3 nanosheets for lithium storage and photocatalytic water oxidation. Energy Environ Sci. 2013;6:987–993. doi: 10.1039/c2ee24148j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu H, Zheng Z, Chen BC, Liao LB, Wang X (2017) Cobalt oxide porous nanofibers directly grown on conductive substrate as a binder/additive-free lithium-ion battery anode with high capacity. Nanoscale Res Lett 12:302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Yu SH, Lee SH, Lee DJ, Sung YE, Hyeon T. Conversion reaction-based oxide nanomaterials for lithium ion battery anodes. Small. 2016;12:2146–2172. doi: 10.1002/smll.201502299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ponrouch A, Taberna PL, Simon P, Palacin MR. On the origin of the extra capacity at low potential in materials for Li batteries reacting through conversion reaction. Electrochim Acta. 2012;61:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2011.11.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mao Y, Duan H, Xu B, Zhang L, Hu Y, Zhao C, Wang Z, Chen L, Yang Y. Lithium storage in nitrogen-rich mesoporous carbon materials. Energy Environ Sci. 2012;5:7950–7955. doi: 10.1039/c2ee21817h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balaya P, Bhattacharyya AJ, Jamnik J, Zhukovskii YF, Kotomin EA, Maier J. Nano-ionics in the context of lithium batteries. J Power Sources. 2006;159:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2006.04.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu Y, Liu Z, Nam K, Borkiewicz OJ, Cheng J, Hua X, Dunstan MT, Yu X, Wiaderek KM, Du L, Chapman KW, Chupas PJ, Yang X, Grey CP. Origin of additional capacities in metal oxide lithium-ion battery electrodes. Nat Mater. 2013;12:1130–1136. doi: 10.1038/nmat3784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Larcher D, Masquelier C, Bonnin D, Chabre Y, Masson V, Leriche JB, Tarascon JM. Effect of particle size on lithium intercalation into alpha-Fe2O3. J Electrochem Soc. 2003;150:A133–A139. doi: 10.1149/1.1528941. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu H, Chen J, Hng H, Lou X. Nanostructured metal oxide-based materials as advanced anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Nano. 2012;4:2526–2542. doi: 10.1039/c2nr11966h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are fully available without restriction.