Abstract

Objective

Visual hyperexcitability in the form of abnormal contrast gain control has been shown in photosensitive epilepsy and idiopathic generalized epilepsies. We assessed the accuracy and reliability of measures of visual contrast gain control in discerning individuals with idiopathic generalized epilepsies from healthy controls.

Methods

Twenty-four adult patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy and 32 neurotypical control subjects from two study sites participated in a prospective, cross-sectional study. We recorded steady-state visual evoked potentials to a wide range of contrasts of a flickering grating stimulus. The resultant response magnitude vs. contrast curves were fitted to a standard model of contrast response function, and the model parameters were used as input features to a linear classifier to separate patients from controls. Additionally we compared the relative contribution of model parameters towards the classification using a sparse feature-selection approach.

Results

Classification accuracy was 80% or better. Sensitivity and specificity both were 80–85%. Cross validation confirmed robust classifier performance generalizable across the data from the two samples. Patients’ relative lack of gain control at high contrasts was the most important information distinguishing patients from controls.

Conclusions

Individuals with idiopathic generalized epilepsy were distinguishable from the neurotypical with a high degree of accuracy and reliability by a reduction in gain control at high contrasts.

Significance

Gain control is an essential neural operation that regulates neuronal sensitivity to stimuli and may represent a novel biomarker of hyperexcitability.

Keywords: biomarker, hyperexcitability, machine learning, visual-evoked potentials

1. Introduction

Biomarkers are objective measurements reflecting a biological process and are a high priority in epilepsy research (Kelley et al., 2009). An ideal biomarker has high specificity and sensitivity, low costs and risks, and a potential to elucidate mechanism of disease. To date, however, no highly sensitive biomarker of epilepsy is available (Engel, 2011). In idiopathic (also termed primary or genetic) generalized epilepsies (IGE), the presence of bilateral synchronous epileptiform discharges is helpful to confirm the diagnosis (Koutroumanidis and Smith, 2005). Accordingly, electroencephalogram (EEG) is recommended following a first seizure (Krumholz et al., 2007). However, epileptiform discharges on EEG, being less sensitive (25–50%) than specific (79–98%) (Smith, 2005), are limited in diagnostic yield. The probability of identifying interictal epileptiform patterns on a first EEG is about 50% overall (King et al. 1998; Salinsky et al. 1987), somewhat higher in generalized epilepsies (King et al., 1998). While serial EEG (up to 4) can increase the diagnostic yield, around 10% of the patients do not have epileptiform discharges (Salinsky et al., 1987). Some patients require long-term monitoring to definitively characterize their epilepsy syndrome (Ghougassian et al., 2004). Therefore, a search for novel markers of IGE is warranted.

We have previously linked human IGE to alteration of contrast gain control (Tsai et al., 2011). Gain control refers to the dynamic adjustment of a system’s sensitivity to its input and is essential to many sensory and cognitive functions (Carandini and Heeger, 2012). The relationship between the response magnitude and stimulus contrast, so-called contrast-response function (CRF), is well established in both humans and animals (Albrecht and Hamilton 1982; Burr and Morrone 1987; Ross and Speed 1991). The typical CRF has an accelerating rising portion at low to medium contrasts and levels off at high contrasts (Carandini et al., 1997). This “contrast saturation” is shaped by mechanisms of contrast gain control, which reduces the system’s sensitivity to stimulus contrasts under conditions of high prevailing contrast (Bonin et al. 2005; Carandini and Heeger 1994, 2012; Heeger 1992b; Ohzawa et al. 1981; Shapley and Victor 1979). We identified a group effect of a lack of response saturation at high stimulus contrasts in IGE patients – that is, their CRF, on average, continued to increase at high contrasts. Moreover, by modeling the changes in contrast gain, we showed that reduced inhibitory modulation from surrounding neurons could account for the lack of response saturation (Tsai et al., 2011). These results suggest that the state of contrast gain control may be a potential novel marker of IGE. An important unanswered question is the power of this assay in resolving individual subjects. Here we address the accuracy and reliability of an assessment of visual contrast gain control in discerning individuals with IGE from the neurotypical. Our hypothesis is that a lack of response saturation is a marker of IGE.

2. Methods

Data were collected at two sites, University of California San Francisco (SF) and the University of Washington (UW). The SF sample was published in a previous report (Tsai et al., 2011) and re-analyzed here. Experimental procedures were as previously published (Tsai et al., 2011) except for minor differences noted below. Local ethics review boards approved the recruitment and experiment procedures.

2.1. Participants

The SF data comprised of ten patients (mean age 35 years) and thirteen neurotypical controls (mean age 35 years). The UW data comprised of 14 patients (mean and median age 33 years) and 19 neurotypical controls (mean age 29 years, median 21 years). Patients were diagnosed with IGE at tertiary epilepsy centers. Here we consider idiopathic generalized epilepsies as a neurobiological continuum (Berkovic et al., 1987) wherein syndromes share overlapping features, including genetic loci (Sander et al., 2000), seizure types, diurnal pattern of seizures, and response to treatment (Reutens and Berkovic, 1995). Medications and other clinical information of the UW patients are summarized in Table 1. Excluded were those with other neurological disorders. All subjects had normal or corrected-to-normal visual acuity.

Table 1.

Clinical information of the 14 patients in the UW sample. Seizure freedom is defined as no seizure for at least 2 years.

| ID | Sex | Age (year) |

Age onset (year) |

Diagnosis | Current AED |

Photo- sensitivity |

Seizure free |

Electro-clinical data |

EEG at time of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | F | 21 | 8 | JME | KLZ, LTG, ZNS |

N | N | abs, GTC, myo; soon after awakening. 3 Hz GSW. |

mild background slowing. 2- 4 Hz GSW. |

| 14 | F | 33 | 21 | JME | LAC, ETX, TPM, PHT |

N | N | abs, GTC. GSW, gen polyspikes on LTM. |

Normal awake. |

| 30 | M | 22 | 5 | CAE | LTG, VPA |

N | Y | abs, GTC. Mother and twin have epilepsy. GSW and polyspikes on EEG. |

normal awake. |

| 48 | M | 25 | late teen |

JME | LEV | N | N | myo, abs, GTC. 4 Hz polyspikes on LTM. |

normal awake. |

| 60 | M | 40 | 15 | JME | LEV, TPM |

Y | N | myo, GTC. Video game trigger. Primary GTC on LTM. |

normal awake. |

| 97 | F | 44 | 10 | JAE | KLZ, LTG, TPM, FEB |

N | N | abs, GTC. 3–4 Hz GSW on LTM. |

Left frontal theta, otherwise normal awake. |

| 121 | F | 33 | 13 | JME | LTG | N | N | myo, GTC in morning. 3–4 Hz GSW, polyspikes on EEG. |

normal awake. |

| 125 | F | 20 | 11 | JAE | LEV, ZNS | N | N | abs status, GTC. Gen bifrontal spikes. Normal EEG 2015. |

normal awake. |

| 126 | F | 40 | 39 | IGE | KLZ, LTG | N | N | GTC, 3.5 Hz polyspike-waves on EEG. |

normal awake. |

| 128 | F | 21 | 4.5 | CAE | none | N | N | abs, GTC. 3–5 Hz GSW and absence on LTM. |

normal awake. |

| 131 | M | 52 | 6 | CAE | TPM, LTG, CLB |

N | N | GTC, abs, later myo. abs and 3–4 Hz GSW on LTM. |

normal awake. |

| 156 | F | 39 | 17 | GTC AM | PHT | N | N | GTC in morning. | normal awake. |

| 162 | M | 45 | 21 | GTC AM | PB, LTG | N | Y | GTC in morning. 5- 6 Hz GSW/poly- spikes EEG 2000. normal EEG 2009. |

normal awake. |

| 178 | F | 23 | 16 | JME | LEV | Y | Y | myo. PPR, posterior and GSW on EEG. |

normal awake. |

JME juvenile myoclonic epilepsy; CAE childhood absence epilepsy; JAE juvenile absence epilepsy; GTC AM generalized tonic clonic seizures upon awakening; KLZ clonazepam; LTG lamotrigine; ZNS zonisamide; LAC lacosamide; ETX ethosuximide; TPM topiramate; PHT phenytoin; VPA valproic acid; LEV levetiracetam; FEB felbatol; CLB clobazam; PB phenobarbital. GTC generalized tonic clonic; GSW generalized spike wave; abs absence; myo myoclonic seizure; PPR photoparoxysmal response; LTM long term monitoring, gen generalized.

2.2. Display and stimuli

Stimuli were shown in a darkened room using in-house software (powerDIVA) on cathode-ray tube monitors calibrated for nonlinear voltage vs. luminance response: a 19” LaCie Electron Blue monitor with 72 Hz vertical refresh rate and a mean luminance of 34cd/m2 (SF), and a 19” SONY 75 Hz refresh rate and mean luminance of 57 cd/m2 (UW). Subjects viewed the display binocularly at a distance of 127cm.

Briefly, stimuli were horizontal sine gratings (2 cycles/degree) windowed by a circularly symmetric Gaussian envelope (4 degrees radius) presented at fixation. The mean luminance was kept constant throughout the experiments. Stimulus contrast was defined as the difference between the maximum and minimum luminance of the grating divided by their sum. The contrast of the stimulus was temporally modulated (contrast-reversals) by a 7.2 Hz and 7.5 Hz sinusoid for SF and UW, respectively. For the SF experiments, the peak contrast was held fixed to one of the following: 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8, during each trial (10 seconds). For the UW experiments, the peak contrast was swept from 0.013 to 0.94 in 10 equal log-steps over each 10-second trial. The fixed-contrast and swept steady-state visual evoked potentials (SSVEP) paradigms have been shown to yield comparable contrast response functions (Tsai et al., 2011). Twenty trials of each condition were obtained with a short 3–5 second break in between trials.

2.3. SSVEP recording and preprocessing

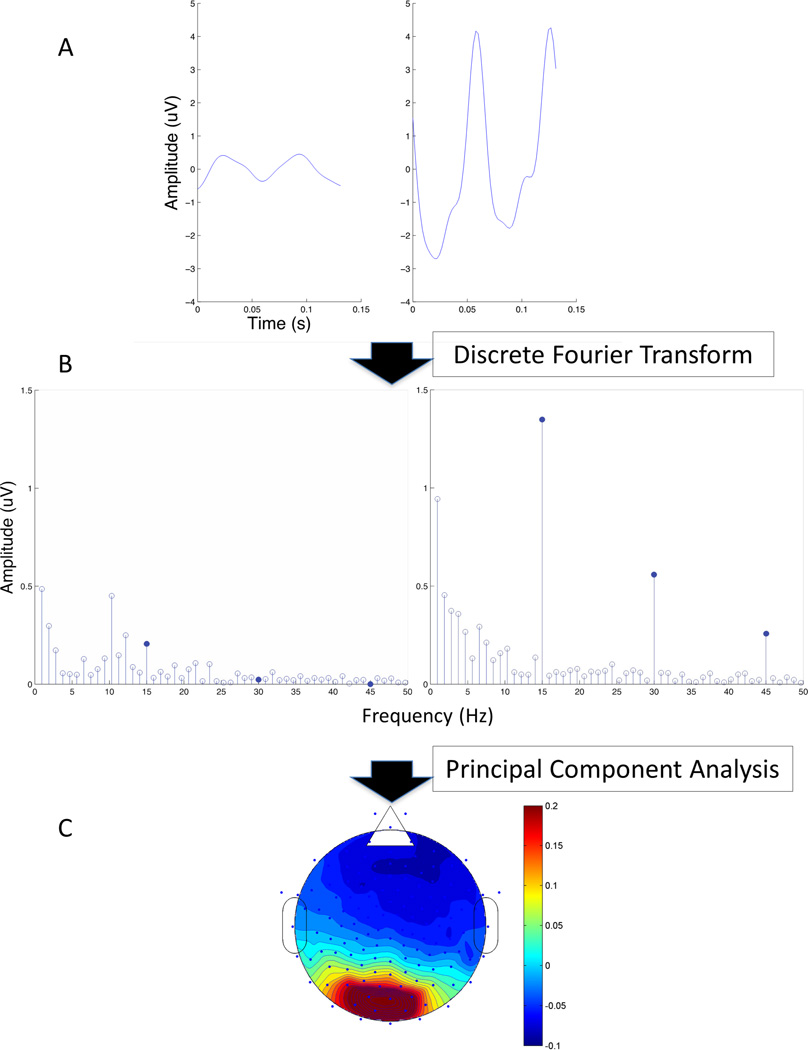

EEG was recorded using 128-electrode HydroCel Sensor Nets on an Electrical Geodesic Inc. (Eugene, OR) NetStation 200 (SF) or NetStation 300 system (UW). Signals were recorded with a vertex physical reference, amplified with a gain of 1,000, band-pass filtered at 0.1–50 Hz, and digitized at 432 Hz (SF) or 450 Hz (UW). Artifact rejection, re-referencing, and spectral analysis were as described in Tsai et al. (2011). The frequency resolution of the spectral analysis was 0.93 Hz and 0.5 Hz for the UW and the SF data, respectively. The data-processing pipeline is illustrated in Fig. 1 using data from a typical subject.

Figure 1.

Data from UW subject 49. (A) EEG signal from the Oz electrode averaged over one cycle of stimulus with peak contrast of .02 (left panel) and .94 (right) to illustrate low and high contrast responses. Waveforms shown were the data averaged over one stimulus cycle, which was 133 ms in duration. Two peaks are evident in the response because there were two contrast reversals per stimulus cycle. (B) Spectrum of the average response analyzed over the duration of each step (1.07 seconds) of the contrast sweep. Filled circles indicate the first 3 even harmonics of the stimulus frequency. (C) Scalp topography of the first principal component of the SSVEP amplitude calculated over 128 EEG channels.

We followed the approach outlined by Appelbaum et al. (2006) in calculating a “total amplitude” index of SSVEPs. The rationale for this approach is to maximize the power of the index by capturing as much of the SSVEP response as possible without a priori knowledge of which harmonics are important to distinguish epilepsy subjects. As illustrated in Fig. 1B, the SSVEPs consist of even harmonic components since two contrast reversals occur in each cycle of the stimulus (Regan, 1989). Therefore, we pooled the largest three even harmonics to represent the total activity. From the collated responses at each stimulus contrast and each channel for each subject, we computed the first spatial principal component, which represented a weighted sum of the channels so as to account for the largest proportion of the variance in the data. The even harmonic responses were projected onto the first principal component (Fig. 1C) and the Euclidian norm of the projections was computed as a measure of the response magnitude.

2.4. Modeling

Contrast response functions were fitted to a standard model (Albrecht and Hamilton 1982; Heeger 1992b; Peirce 2007),

| (1) |

where R is the response magnitude, c is stimulus contrast, Rmax is the maximal response, b is the baseline response, and ν is the semi-saturation constant. Here the exponent of the hyperbolic ratio is set to two (Carandini et al. 1997; Heeger 1992a; Tsai et al. 2012). Eq. 1 serves both as a descriptive model of a sigmoid-shaped function (Albrecht and Hamilton, 1982), as well as a computational model of gain control (via the “normalization” operation) (Carandini and Heeger 2012; Heeger 1992b). Importantly, the parameter s quantifies the degree of response saturation in the following manner. If s = 1, the model describes a monotonically increasing function that asymptotically approaches Rmax, i.e., the function “saturates”. If s < 1, the function increases without bound (no “saturation”). Finally if s > 1, the function rises to a peak then decreases thereafter, a phenomenon known as “supersaturation”, which has been observed in field potentials and single unit recordings (Peirce, 2007; Tsai et al., 2012). Data fitting was accomplished using a nonlinear least square regression routine lmfit in Python 2.7.

2.5. Machine learning

In general, machine learning makes use of a known (training) data set, comprising of input data features and corresponding output labels, to construct a prediction model (classifier) applicable to unknown (testing) data sets. Here we used support vector machine (SVM), a standard classification technique that has been successfully applied to biomedical data (Furey et al., 2000; Klöppel et al., 2008). SVM constructs a “hyper-plane” in the data space that divides the data into two groups and maximizes the margin of separation between them (see the Supplementary Appendix for mathematical details). Here the input data features were the estimated parameters in Eq. (1) and the output was the group labels (epilepsy vs. control).

Accuracy of the classification was defined as the proportion of subjects labelled correctly. A “leave-one-out” validation was performed as follows. The data set was decomposed into N subsamples, equal to the number of subjects. From these N subsamples, a single subsample was kept as the test data while the remaining N−1 subsamples were used as training data. This process was repeated N times for each of the subsamples (Efron, 1982).

3. Results

3.1. Group-level comparison

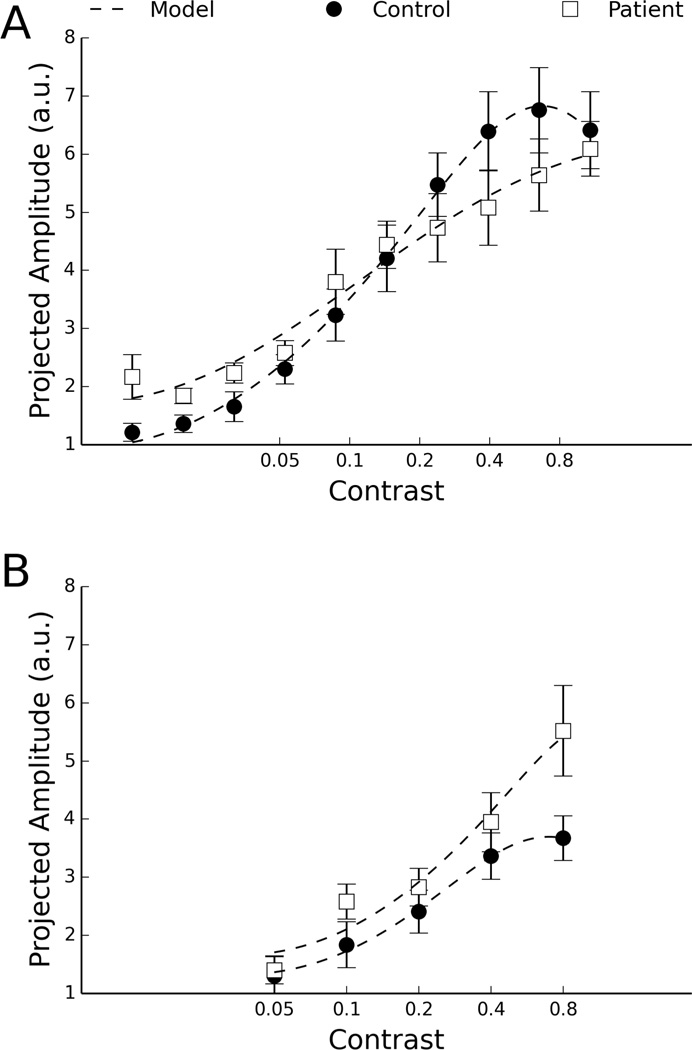

To examine data consistency, we compared the mean CRF’s for patients and controls in the UW and SF samples (Fig. 2). In both samples, the response of the control group plateaued above 40% contrast, while that of the patient group continued to increase throughout the range of contrasts presented. Thus, the new data (UW) replicated the lack of response saturation in IGE (Tsai et al., 2011). The non-monotonic response at high stimulus contrasts evident in the UW control group is a phenomenon known as “supersaturation” or “oversaturation”. Supersaturation has been observed in single unit responses (Albrecht and Hamilton, 1982; Li and Creutzfeldt, 1984; Peirce, 2007; Williford and Maunsell, 2006) and in ensemble activity recorded at the scalp (Lauritzen et al., 2010; Tsai et al., 2012; Tyler and Apkarian, 1985;). The point at which the inflection appeared was found to be around 50% to 75% contrast in a human study (Tyler and Apkarian, 1985) and approximately 75% contrast on average in a sample of single neurons in the cat (Li and Creutzfeld, 1984). Thus the observation of supersaturation may depend on the range of contrast examined (whether it covers the inflection point). In the UW sample, the contrast range extended to higher value (94% vs. 80%) and was more finely sampled (0.6 vs. 1 octave steps) than in the SF sample. Supersaturation was more apparent in the UW than in the SF sample likely by virtue of difference in the contrasts used.

Figure 2.

Mean contrast response function of each group. The norm of the projected amplitude of the 2nd, 4th, and 6th harmonics of the SSVEP was averaged across the subjects within each group. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean. Dashed lines are the best fitting model. (A) UW data (B) SF data.

To quantify the difference in the shape of the CRF between patients and controls, we fitted the CRF’s to a standard model (Albrecht and Hamilton, 1982; Heeger, 1992b; Peirce, 2007) (see methods). The best fitting values of the model to the data are shown in Table 2. The model fits the data well, as evident by the large explained variance (R2 > 0.96). The degree of response saturation (the parameter s) was significantly smaller in patients compared to controls, as evident by the non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals, indicating a relative lack of response saturation in patients compared to controls. Of note, the remaining three parameters did not show a consistent pattern across the two data samples. For example, although patients had greater maximal response (Rmax) in the SF data, the reverse was true in the UW data. Although the mean age of the control subjects was smaller in the UW relative to the SF sample (29 vs. 35), there was no significant correlation between individual subject’s age and the Rmax (Pearson’s ρ = −0.1, p = 0.5). Therefore, the modest age difference did not contribute to the amplitude variation in our samples.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates for the group mean CRF’s shown in Fig. 2. The range indicated for each estimate represents the 95% confidence interval. R2 is the proportion of variance explained.

| Sample | Group | Model parameters | R2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s | ν | Rmax | b | |||

| UW | Controls | 3.91 [3.53, 4.37] | 1.02 [0.95, 1.21] | 12.20 [11.21,13.23] | 0.94 [0.83, 1.16] | 0.99 |

| Patients | 1.39 [1.03, 3.07] | 0.97 [0.72, 1.17] | 9.22 [7.97, 15.76] | 1.72 [1.53, 2.28] | 0.98 | |

| SF | Controls | 3.22 [2.91, 3.75] | 1.07 [0.80,1.19] | 6.20 [5.32, 8.11] | 1.33 [1.18, 2.37] | 0.99 |

| Patients | 1.01 [0.62. 2.77] | 1.51 [1.21, 1.98] | 12.36 [9.68, 14.99] | 1.56 [1.20, 1.97] | 0.96 | |

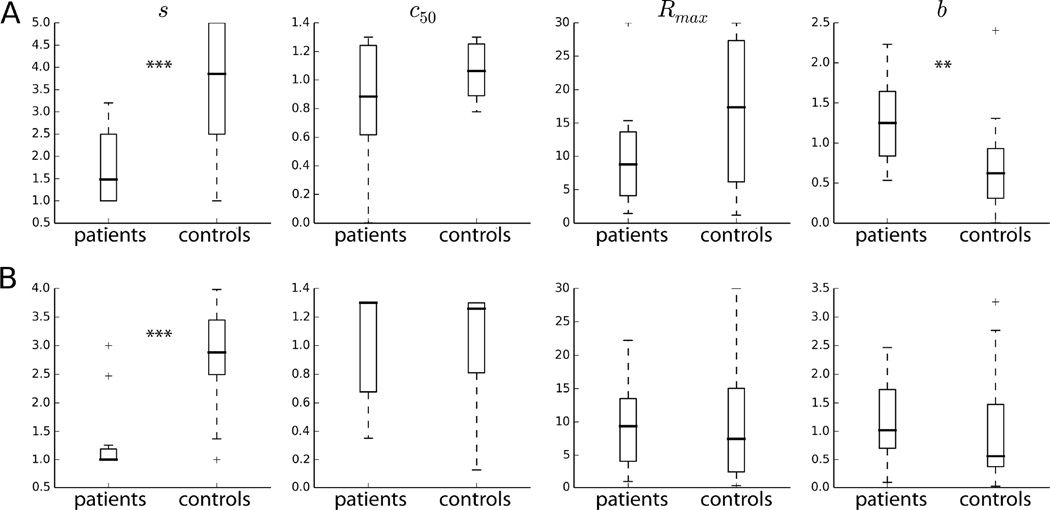

3.2. Individual-level classification

We next fitted individual subject’s CRF to the model (Eq. 1), obtaining a set of parameter values for each subject. The mean R2 of the individual fits was 0.87 and 0.89 for UW and SF, respectively, indicating that the model captured the data quite well. Fig. 3 shows the scatter of the four parameters. Notably, the degree of response saturation was significantly smaller in patients compared to controls. The other three parameters did not show a consistent relationship across the two samples. To systematically evaluate the separability of patients from controls, we applied a linear support vector machine (SVM), taking the four parameters as data features, to classify each subject as either a patient or control.

Figure 3.

Boxplots of model parameters fitted to individual subjects’ contrast response function. (A) UW (B) SF data. *** denotes p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05 (Mann-Whitney rank test).

We verified the classification results via two approaches: first, a “leave-one-out” cross-validation scheme; and second, by training on one sample (UW or SF) then testing the classifier on the remaining sample, and vice versa. Table 3 shows the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity for combinations of sample and validation scheme. In general, accuracy, sensitivity and specificity were 80% or better. Accuracy was modestly greater with the leave-one-out than the alternate approach, as might be expected by virtue of disjoint training and testing samples in the latter. When the two samples were merged, accuracy decreased slightly compared to when each sample was separately analyzed. Accuracy was similar regardless of whether the classifier was trained on the UW data and tested on the SF data, or vice versa. Together, these results showed that the classifier was robust and reliable with similar accuracy, sensitivity and specificity across two independent data sets.

Table 3.

Classification results obtained using a linear classifier. See text for details.

| Validation scheme |

Leave one out | Training | Testing | Training | Testing | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | UW | SF | UW ∪ SF | UW | SF | SF | UW |

| Accuracy | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.82 | ||

| Sensitivity | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.85 | ||

| Specificity | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.79 | ||

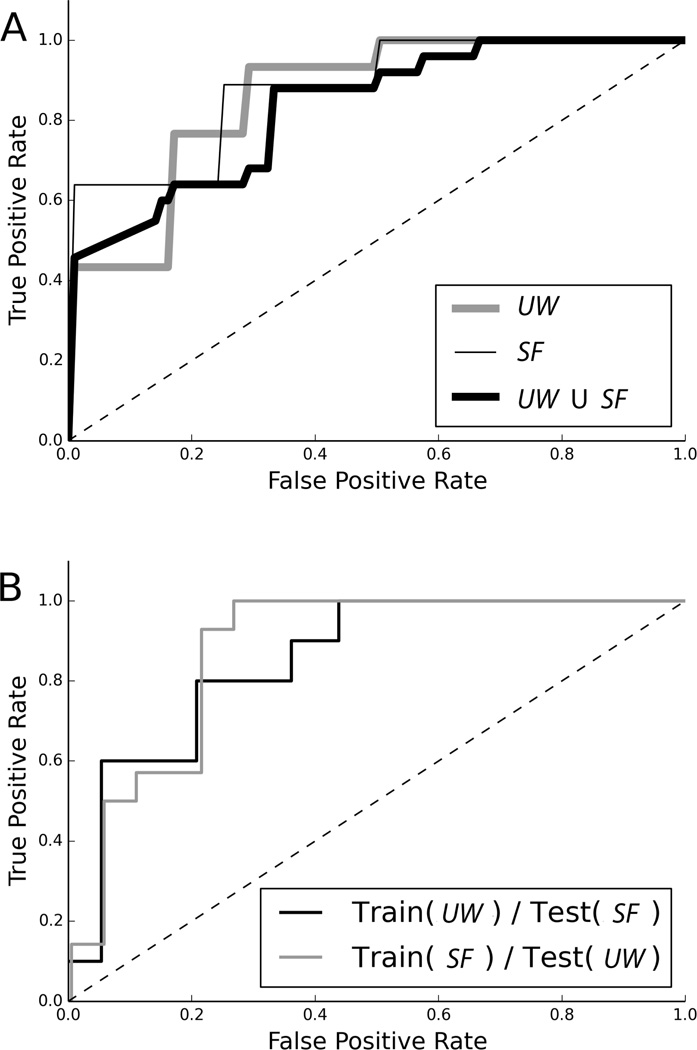

Performance of a binary classifier is commonly depicted as a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The area under the curve (AUC) provides another measure of the discriminability of the two classes. The ROC curves for each experiment (see Fig. 4) were in line with the classification accuracy results reported above.

Figure 4.

Receiver operating curves for various classification experiments. (A) Leave-one-out cross validation. (B) training and testing on disjoint data sets. The corresponding area under curve (AUC) are 0.87 for UW, 0.89 for SF, and 0.83 for the merged data (UW ∪ SF), 0.84 for training (UW)/testing (SF) and 0.87 for training (SF)/testing (UW).

3.3. Classifier feature selection

To gain insight into the basis for the classification, we examined the relative order of each model parameter in terms of its contribution to the classifier. We used a sparse feature-selection strategy that imposed a penalty (1/λ) on the number of parameters used by the classifier (see the Supplementary Appendix for mathematical details). In principle, inclusion of more parameters might potentially improve accuracy, but at additional cost. As the penalty increased, only the most informative parameters tended to be selected. By iteratively stepping through a range of penalty values and correlating with selected parameters, we determined the relative selection frequency of each parameter. Table 4 shows that the response saturation parameter was most frequently selected as the penalty increased. This result indicated that response saturation was the most important feature for distinguishing patients from controls.

Table 4.

Ranking of the model parameters. Selection frequency, defined as the number of times a parameter was selected divided by the number of steps (1,000) between the extrema of regularization parameter λ given. The range of λ was empirically chosen so as to allow for separation of the parameters. As an example, two different intervals were illustrated for the SF data. By appropriate choice of interval, one can resolve the relative order between pairs of parameters.

| Sample | Range of λ | Selection frequency | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s | ν | Rmax | b | ||

| UW | [0.03, 0.1] | 1.000 | 0 | 0.825 | 0.66 |

| SF | [0.03, 0.2] | 1.000 | 0 | 0.887 | 0.568 |

| [0.03, 0.04] | 1.000 | 0 | 0.156 | 0 | |

| UW ∪ SF | [0.03, 0.06] | 1.000 | 0 | 0.208 | 0.619 |

3.4. Clinical correlates

EEG recorded as part of this study was reviewed by a trained clinical neurophysiologist (JT). Twenty-one out of 24 patients had a normal background without epileptiform patterns. One patient (UW 10) showed mild background slowing and frequent runs of 2–4 Hz generalized spike-wave discharges. A second (SF 2) had rare bursts of frontally predominant polyspikes. A third (SF 10) had occasional 6Hz generalized spike-wave bursts. A caveat is that EEG data were limited in duration (about 12–20 minutes) and did not follow standard clinical protocol (e.g. no hyperventilation, no sleep).

An interesting question is whether the classification outcome was affected by degree of seizure control or EEG abnormalities. That is, was the classifier more likely to mis-classify a patient if she had normal EEG or was seizure-free? Out of a total of 24 patients, six were seizure free for at least 2 years (UW 30, 162, 178; SF 1, 3, 4), three had epileptiform patterns on EEG at the time of the study (UW 10; SF 2, 10), and four were incorrectly classified by our classifier (UW 14, 48; SF 7, 9). There was no overlap among these subjects and thus no clear correlation between epileptiform EEG, seizure control, and classification accuracy.

4. Discussion

We demonstrated that individuals can be classified as IGE or neurotypical with a high degree of accuracy and reliability based on interictal visual evoked potentials. The sensitivity of our assay in particuar compared favorably to that of finding epileptiform discharges on standard clinical EEG. An initial EEG demonstrated epileptiform activity in 67% of those who presented with first time seizure and were eventually diagnosed with IGE based on clinical, EEG and imaging data. A follow-up sleep deprived study identified additional 23% with epileptiorm discharges (King et al., 1998). In another study, the prevalence of epileptiform discharges in IGE patients who were not seizure-free was 57–83% and in their siblings 8–13% (Badawy et al., 2013). Notably, most of the patients in our study had normal EEG at the time of this study but still showed abnormal gain control, suggesting that gain control can be a useful adjunct to identifying epileptic subjects. While our approach will not replace routine EEG, it may provide a rapid and accessible ancillary test to facilitate the diagnosis of IGE.

4.1. Other biomarkers of generalized epilepsies

One promising biomarker is cortical motor hyperexcitability investigated using paired-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) (Badawy et al., 2014). Compared to healthy controls, patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) manifested decreased intracortical inhibition correlating with degree of seizure control (Badawy et al., 2010; Manganotti et al., 2000). While TMS offers a powerful assay of hyperexcitability, to date the reported results using pair-pulse TMS have been limited to group level analysis due to response variability (Badawy et al., 2014). Refinement of this approach may enable extension to individuals.

Another long-known trait associated with epilepsy is photosensitivity, characterized by seizures or epileptiform activity induced by flickering lights (Trenité, 2006). Photosensitivity is five-times more common in generalized than focal epilepsy patients (Wolf and Goosses, 1986). Photosensitivity, as traditionally identified, is limited by a low sensitivity even among IGE patients. Of note, only two (of 24) patients included in the current study had evidence of photosensitivity. The assessment of visual evoked responses over a range of contrasts, as we have shown, appears to confer greater sensitivity.

4.2. Interpretation of machine learning results

SVM and other machine learning techniques, notably artificial neural networks, have achieved remarkable success in solving a number of complex pattern recognition problems from classifying background EEG in epilepsy (Koçer and Canal, 2011) to the game of Go (Silver et al., 2016). We leveraged machine learning to systematically evaluate which aspects of the SSVEP were relevant to separating patients from controls. While response saturation was most important, other parameters were also relevant (Table 4). In contradistinction, the semi-saturation parameter ν appeared to be the least important. This suggests that response to high-contrast stimuli, where contrast saturation is evident, may be preferentially scrutinized for screening purposes. Our approach differed from some other studies in that, in addition to the clinical objective of correct classification, we sought to understand the biological basis for the difference between epilepsy patients and controls. The lack of gain control identified has important implications for the study of epilepsy as we will discuss below.

4.3. Neural computation and epilepsy

There is growing appreciation that epilepsy is not simply a seizure disorder, but a systems disorder affecting multiple domains of the brain (Jensen, 2011; Wolf and Beniczky, 2014), including psychiatric and cognitive. Efforts are under way to probe the molecular and cellular mechanisms common to both epilepsy and comorbidities such as depression and autism (Jensen, 2011). However, little is known about the nature of the impact at the systems level. In this context, our results shed new light on functional disturbance in epilepsy. Gain control mechanisms operate in many sensory systems and association areas and are thus proposed to be a canonical computation of the brain (Kouh and Poggio, 2008; Carandini and Heeger, 2012). Gain control enables flexible and efficient neural coding, such as maximizing sensitivity given limited dynamic response range, robust representation invariant to changes in irrelevant stimulus feature (Carandini and Heeger, 2012). A disruption of gain control mechanisms could have widespread and fundamental effects on neural computation (Carandini and Heeger, 2012).

What might give rise to the abnormal contrast gain control seen in IGE patients? Contrast gain control is known to operate at multiple levels of the visual pathway (Bonin et al., 2005; Ohzawa et al., 1981; Shapley and Victor, 1979). Our results do not implicate any specific site or biophysical mechanism of gain control, which is an active area of research. A putative mechanism of gain control is GABAergic inhibition that modulates gain and temporal summation via memebrane shunting conductance (Carandini and Heeger, 1994; Carandini et al., 1997; Morrone et al., 1987). Other candidate mechanisms include synaptic depression and action potentials generation – it is likely that different mechanisms are responsible for gain control depending on species and systems (Carandini and Heeger, 2012). Insofar as epilepsy may impact these different mechanisms in different brain areas, the concept of gain control can serve as an unifying “computational endo-phenotype” across the spectrum of epilepsies.

4.4. Effects of anti-epileptic drugs

The literature on the effect of anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) on visual evoked potentials indicates that AEDs are unlikely to account for the relative lack of response saturation at high contrasts in IGE patients. Data are most abundant for valproic acid (VPA), which can reduce or abolish spike-wave discharges (Bruni et al., 1980) and photoparoxysmal response (Harding et al., 1978). In a study of 10 healthy volunteers, VPA at 500mg or 1000mg per day did not affect the latency or amplitude of the P100 response in pattern reversal VEP (Harding et al., 1985). Using the same paradigm, Sundqvist et al. (1999) also found no effect on the VEP in 16 juvenile myoclonic epilepsy patients treated with VPA monotherapy at 1000mg and 2000mg/day for 6 months each. Using an on-off SSVEP paradigm, Geller et al. (2005) found no effect of VPA on the second harmonic amplitude in generalized epilepsy compared to healthy controls. In contrast to the above, amplitude of the flash VEP in photosensitive epilepsy patients decreased following treatment with VPA (Herrick and Harding, 1980). Similar results were reported for other AEDs. In a group of patients with unspecified epilepsies on monotherapy with carbamazepine, levetiracetam, or VPA, no significant change was observed in P100 amplitude compared to healthy controls not taking medications (Tumay et al., 2013). Carbamazepine had no effect on SSVEP amplitude compared to healthy controls not taking any medication (Geller et al., 2005). In a group of 30 focal and generalized epilepsy patients, monotherapy using phenytoin, carbamazepine, or phenobarbital did not change the latency or amplitude of P100, but polypharmacy decreased the amplitude and increased latency (Drake et al., 1989). In sum, the preponderance of the evidence indicate that AEDs do not alter the amplitude of visual evoked potentials in neurotypical subjects or in patients with generalized epilepsies, but that the amplitude may be reduced with polytherapy or in certain groups such as photosensitive and complex partial epilepsies. Given these findings, it is unlikely that AEDs contributed to the effect that we report, greater amplitude at high contrasts, i.e. lack of response saturation, in IGE patients compared to controls.

4.5. Limitations and open questions

Current understanding of generalized epilepsies posits that widely distributed brain networks subserving normal physiological functions are “hijacked” to generate paroxysmal rhythms and reflex seizures (Beenhakker and Huguenard, 2009; Wolf and Beniczky, 2014). On the other hand, focal epilepsies as a whole comprise a heterogenous group of individualized epileptic networks (Fahoum et al., 2012). What is the role of contrast gain control in focal epilepsy, and whether it could distinguish focal from generalized epilepsies are important open questions (Badawy et al., 2007). Moreover, it is unknown how gain control might depend on clinical variables such as genetic mutations, background EEG, or degree of seizure control. These questions need to be addressed by a larger study. Lastly, despite minor differences in methodology and demographics between the two data samples, the findings were remarkably concordant.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the diagnostic utility of visual evoked potentials in distinguishing IGE from healthy individuals. It further substantiates a link between abnormal contrast gain control and hyperexcitability. Further study of gain control may lead to insights into common final pathway and novel biomarkers for a broad class of epilepsies.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy (IGE) manifest abnormal gain control to increasing contrast of visual stimuli.

IGE patients were reliably classified from healthy controls based on the contrast responses.

The most discriminating feature was patients' relative lack of gain control at high contrasts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John W. Miller for helpful suggestions on the manuscript. This work was supported by NSF grant CMMI 1333841 to DW and WAC, and by NIH grant EY020876 to JJT. The funding sources had no influence on the study design, collection and analysis of data, and writing of report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have potential conflicts of interest to be disclosed.

References

- Albrecht DG, Hamilton DB. Striate cortex of monkey and cat: contrast response function. J Neurophysiol. 1982;48:217–237. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum LG, Wade AR, Vildavski VY, Pettet MW, Norcia AM. Cue-Invariant Networks for Figure and Background Processing in Human Visual Cortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11695–11708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2741-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badawy RaB, Vogrin SJ, Lai A, Cook MJ. Capturing the epileptic trait: cortical excitability measures in patients and their unaffected siblings. Brain. 2013;136:1177–1191. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badawy RAB, Curatolo JM, Newton M, Berkovic SF, Macdonell RAL. Changes in cortical excitability differentiate generalized and focal epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:324–331. doi: 10.1002/ana.21087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badawy RAB, Macdonell RAL, Berkovic SF, Newton MR, Jackson GD. Predicting seizure control: cortical excitability and antiepileptic medication. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:64–73. doi: 10.1002/ana.21806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badawy RAB, Strigaro G, Cantello R. TMS, cortical excitability and epilepsy: the clinical impact. Epilepsy Res. 2014;108:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beenhakker MP, Huguenard JR. Neurons that fire together also conspire together: is normal sleep circuitry hijacked to generate epilepsy? Neuron. 2009;62:612–632. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkovic SF, Andermann F, Andermann E, Gloor P. Concepts of absence epilepsies Discrete syndromes or biological continuum? Neurology. 1987;37:993–993. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.6.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonin V, Mante V, Carandini M. The suppressive field of neurons in lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10844–10856. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3562-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruni J, Wilder BJ, Bauman AW, Willmore LJ. Clinical efficacy and long-term effects of valproic acid therapy on spike-and-wave discharges. Neurology. 1980;30:42–42. doi: 10.1212/wnl.30.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr D, Morrone M. Inhibitory interactions in the human vision system revealed in pattern-evoked potentials. J Physiol. 1987;389:1–21. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carandini M, Heeger D. Summation and division by neurons in primate visual cortex. Science. 1994;264:1333–1336. doi: 10.1126/science.8191289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carandini M, Heeger DJ. Normalization as a canonical neural computation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:51–62. doi: 10.1038/nrn3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carandini M, Heeger DJ, Movshon JA. Linearity and Normalization in Simple Cells of the Macaque Primary Visual Cortex. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8621–8644. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08621.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes C, Vapnik V. Support-vector networks. Mach Learn. 1995;20:273–297. [Google Scholar]

- Drake ME, Pakalnis A, Padamadan H, Hietter SA, Brown M. Effect of anti-epileptic drug monotherapy and polypharmacy on visual and auditory evoked potentials. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1989;29:55–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. The Jackknife, the Bootstrap and Other Resampling Plans. Philadelphia: SIAM; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Engel J. Biomarkers in epilepsy: introduction. Biomark Med. 2011;5:537–544. doi: 10.2217/bmm.11.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahoum F, Lopes R, Pittau F, Dubeau F, Gotman J. Widespread epileptic networks in focal epilepsies: EEG-fMRI study. Epilepsia. 2012;53:1618–1627. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03533.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furey TS, Cristianini N, Duffy N, Bednarski DW, Schummer M, Haussler D. Support vector machine classification and validation of cancer tissue samples using microarray expression data. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:906–914. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller AM, Hudnell HK, Vaughn BV, Messenheimer JA, Boyes WK. Epilepsy and Medication Effects on the Pattern Visual Evoked Potential. Doc Ophthalmol. 2005;110:121–131. doi: 10.1007/s10633-005-7350-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghougassian DF, d’Souza W, Cook MJ, O’Brien TJ. Evaluating the utility of inpatient video-EEG monitoring. Epilepsia. 2004;45:928–932. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.51003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding GFA, Alford CA, Powell TE. The Effect of Sodium Valproate on Sleep, Reaction Times, and Visual Evoked Potential in Normal Subjects. Epilepsia. 1985;26:597–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1985.tb05698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding GFA, Herrick CE, Jeavons PM. A Controlled Study of the Effect of Sodium Valproate on Photosensitive Epilepsy and Its Prognosis. Epilepsia. 1978;19:555–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1978.tb05036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeger DJ. Half-squaring in responses of cat striate cells. Vis Neurosci. 1992a;9:427–443. doi: 10.1017/s095252380001124x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeger DJ. Normalization of cell responses in cat striate cortex. Vis Neurosci. 1992b;9:181. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800009640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick CE, Harding GFA. The effect of sodium valproate on the photosensitive VEP. In: Barber C, editor. Evoked potentials. Springer; 1980. pp. 539–547. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen FE. Epilepsy as a spectrum disorder: Implications from novel clinical and basic neuroscience. Epilepsia. 2011;52(Suppl 1):1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley MS, Jacobs MP, Lowenstein DH. The NINDS epilepsy research benchmarks. Epilepsia. 2009;50:579–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01813.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King MA, Newton MR, Jackson GD, Fitt GJ, Mitchell LA, Silvapulle MJ, et al. Epileptology of the first-seizure presentation: a clinical, electroencephalographic, and magnetic resonance imaging study of 300 consecutive patients. Lancet. 1998;352:1007–1011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03543-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klöppel S, Stonnington CM, Chu C, Draganski B, Scahill RI, Rohrer JD, et al. Automatic classification of MR scans in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2008;131:681–689. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koçer S, Canal MR. Classifying epilepsy diseases using artificial neural networks and genetic algorithm. J Med Syst. 2011;35:489–498. doi: 10.1007/s10916-009-9385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouh M, Poggio T. A canonical neural circuit for cortical nonlinear operations. Neural Comput. 2008;20:1427–1451. doi: 10.1162/neco.2008.02-07-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutroumanidis M, Smith S. Use and abuse of EEG in the diagnosis of idiopathic generalized epilepsies. Epilepsia. 2005;46(Suppl 9):96–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumholz A, Wiebe S, Gronseth G, Shinnar S, Levisohn P, Ting T, et al. Practice Parameter: evaluating an apparent unprovoked first seizure in adults (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2007;69:1996–2007. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000285084.93652.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritzen TZ, Ales JM, Wade AR. The effects of visuospatial attention measured across visual cortex using source-imaged, steady-state EEG. J Vis. 2010;10:1–17. doi: 10.1167/10.14.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Creutzfeldt O. The representation of contrast and other stimulus parameters by single neurons in area 17 of the cat. Pflügers Arch Eur J Physiol. 1984;401:304–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00582601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manganotti P, Bongiovanni LG, Zanette G, Fiaschi A. Early and Late Intracortical Inhibition in Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2000;41:1129–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrone MC, Burr DC, Speed HD. Cross-orientation inhibition in cat is GABA mediated. Exp Brain Res. 1987;67:635–644. doi: 10.1007/BF00247294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohzawa I, Sclar G, Freeman RD. Contrast gain control in the cat visual cortex. Nature. 1981;298:266–268. doi: 10.1038/298266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce JW. The potential importance of saturating and supersaturating contrast response functions in visual cortex. J Vis. 2007;7:13. doi: 10.1167/7.6.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan D. Human brain electrophysiology : evoked potentials and evoked magnetic fields in science and medicine. New York: Elsevier; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Reutens DC, Berkovic SF. Idiopathic generalized epilepsy of adolescence Are the syndromes clinically distinct? Neurology. 1995;45:1469–1476. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.8.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J, Speed HD. Contrast adaptation and contrast masking in human vision. Proc Biol Sci. 1991;246:61–69. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinsky M, Kanter R, Dasheiff RM. Effectiveness of Multiple EEGs in Supporting the Diagnosis of Epilepsy: An Operational Curve. Epilepsia. 1987;28:331–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1987.tb03652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander T, Schulz H, Saar K, Gennaro E, Riggio MC, Bianchi A, et al. Genome search for susceptibility loci of common idiopathic generalised epilepsies. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1465–1472. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.10.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapley R, Victor JD. The contrast gain control of the cat retina. Vision Res. 1979;19:431–434. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(79)90109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver D, Huang A, Maddison CJ, Guez A, Sifre L, van den Driessche G, et al. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature. 2016;529:484–489. doi: 10.1038/nature16961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SJM. EEG in the diagnosis, classification, and management of patients with epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:ii2–ii7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.069245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundqvist A, Nilsson BY, Tomson T. Valproate monotherapy in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: dose-related effects on electroencephalographic and other neurophysiologic tests. Ther Drug Monit. 1999;21:91–96. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199902000-00014. z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenité DGAK-N. Photosensitivity, visually sensitive seizures and epilepsies. Epilepsy Res. 2006;70:S269–S279. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JJ, Norcia AM, Ales JM, Wade AR. Contrast gain control abnormalities in idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:574–582. doi: 10.1002/ana.22462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JJ, Wade AR, Norcia AM. Dynamics of normalization underlying masking in human visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2012;32:2783–2789. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4485-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumay Y, Altun Y, Ekmekci K, Ozkul Y. The Effects of Levetiracetam, Carbamazepine, and Sodium Valproate on P100 and P300 in Epileptic Patients. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2013;36:55–58. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e318285f3da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler CW, Apkarian Pa. Effects of contrast, orientation and binocularity in the pattern evoked potential. Vision Res. 1985;25:755–766. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(85)90183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williford T, Maunsell JHR. Effects of Spatial Attention on Contrast Response Functions in Macaque Area V4. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:40–54. doi: 10.1152/jn.01207.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf P, Beniczky S. Understanding ictogenesis in generalized epilepsies. Expert Rev Neurother. 2014;14:787–798. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2014.925803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf P, Goosses R. Relation of photosensitivity to epileptic syndromes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49:1386–1391. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.49.12.1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.