Key Points

Question

What is the prognosis for patients undergoing salvage surgery following locoregional recurrence of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma?

Findings

In this cohort study, the most important determinant of overall survival in patients undergoing curative intent salvage surgery for locoregionally recurrent oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma was adjuvant therapy after primary surgery. Patients who received prior adjuvant therapy had a 5-year survival of 10% compared with 74% in the lowest risk group (no prior adjuvant therapy and younger than 62 years).

Meaning

Patients who received adjuvant therapy following primary surgery had significantly worse survival following salvage surgery for locoregionally recurrent oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma.

Abstract

Importance

Locoregional recurrence of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OCSCC) continues to be a life-threatening and difficult clinical situation. Salvage surgery can result in significant morbidities, and survival following recurrence is poor.

Objective

To outline prognostic factors influencing overall survival (OS) following salvage surgery for OCSCC to guide management of treatment for patients with locoregionally recurrent disease.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The medical records of 293 patients presenting to the London Health Sciences Center with locoregionally recurrent OCSCC between October 5, 1999, and May 2, 2011, were retrospectively reviewed. The primary outcome was OS from salvage treatment to last follow-up or death. Univariate analyses were carried out using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. A recursive partitioning analysis was used to create risk groups based on prognosis. Analysis was conducted from December 8, 2015, to February 26, 2016.

Results

Of the 293 patients evaluated, 59 (20%) had recurrence identified after their initial OCSCC treatment; 39 (66%) were men, and the mean (SD) age at diagnosis was 62.2 (11.8) years. Thirty-nine (66%) of these patients underwent salvage surgery for locoregional recurrence with curative intent. Five-year OS from the time of salvage surgery was 43%. Recursive partitioning analysis identified 3 risk groups: (1) high risk (patients who received adjuvant chemoradiotherapy or radiotherapy after initial surgery) with 5-year OS rate of 10% (hazard ratio [HR], 9.41; 95% CI, 2.68-33.04), (2) intermediate risk (previous surgery alone, age ≥62 years) with a 5-year OS rate of 39% (HR, 2.95; 95% CI, 0.86-10.09), and (3) low risk (previous surgery alone, age <62 years) with 5-year OS rate of 74%.

Conclusions and Relevance

This recursive partitioning analysis identified 3 prognostic groups in patients undergoing salvage surgery for recurrent OCSCC. The marked differences in survival between these groups should be taken into consideration when counselling and managing treatment for patients with locoregionally recurrent disease.

This cohort study evaluates overall survival in patients who undergo salvage surgery for recurrent oral cavity squamous cell cancer.

Introduction

Oral cavity squamous cell cancer (OCSCC) remains the most common site of head and neck cancer, with an estimated 300 400 new cases and 145 400 deaths occurring worldwide in 2012. Although 5-year overall survival (OS) for early disease is 90%, survival remains poor in patients with advanced disease despite advances in therapy.

Recurrence of OCSCC occurs in up to 30% of patients, with most failures being local and/or regional relapses. Many of these patients are offered salvage surgery, but despite advances in reconstructive techniques, salvage treatment may result in significant morbidity, including dysphagia, dysarthria, and disfigurement. Prior studies have demonstrated poor prognosis for patients with recurrent OCSCC. Considering the potential morbidity of salvage surgery and the guarded prognosis, clinical indicators of survival may be valuable in guiding patients regarding salvage surgery. This study aimed to characterize prognostic factors influencing survival following salvage surgery for recurrent OCSCC to stratify patients into risk groups according to prognosis and better guide treatment decisions for patients.

Methods

Patient Cohort

This retrospective review included all patients seen at the London Health Sciences Center, London, Ontario, Canada, for whom adequate clinical information was available. A total of 293 patients with OCSCC (mean [SD] age at diagnosis was 62.2 [11.8] years) who received primary surgery, with or without adjuvant treatment, were identified between October 5, 1999, and May 2, 2011. Patient demographics, smoking and alcohol history, staging, and pathologic data (margin status, evidence of lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, and extracapsular spread) were obtained. All staging was completed according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer. The study was approved by the Western University's Health Sciences Research Ethics Board. A waiver of informed consent was granted by the institutional review board due to the retrospective nature of this study.

The presence of recurrent disease was ascertained in all patients. In patients with evidence of recurrence, the disease was restaged, and smoking status and alcohol use were reassessed at the time of recurrence. If salvage surgery was undertaken, pathologic characteristics were collected as indicated above. Treatment of recurrent disease and survival outcomes were recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline descriptive statistics were generated for all patients with recurrent OCSCC. All subsequent analysis was completed only on the cohort receiving salvage surgery. The primary outcome measure was OS measured from the time of salvage treatment of the recurrent disease until the last known follow-up visit or death (any cause). Recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) was performed on these patients based on baseline patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics for each end point using hazard functions.

Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression was performed to identify significant indicators of prognosis for patients undergoing salvage surgery. Kaplan-Meier estimates were generated for OS and stratified by patients receiving salvage surgery and RPA risk groups. These factors were compared using the log-rank test. Effect sizes are reported in the results with 95% CIs. All statistical analysis was performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and the R language environment for statistical computing, version 3.1.3 (http://www.r-project.org) using 2-sided statistical testing. Analysis was conducted from December 8, 2015, to February 26, 2016.

Results

Patient Cohort

A total of 59 patients with OCSSC (20%) developed recurrent disease following initial treatment. A summary of baseline characteristics is listed in Table 1. Complete details are available in the eTable in the Supplement. Median follow-up was 99 months (range, 22-166 months). Mean (SD) time from initial treatment to recurrent disease was 22.4 (18.3) months (range, 1-74 months). Forty-five patients (76%) had local recurrence, 8 patients (14%) had locoregional recurrence, 1 patient (2%) had regional recurrence only, and 5 patients (8%) had distant metastatic disease. Disease recurred in 37 of the 59 patients (63%) within the first 24 months after completion of their primary treatment.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Recurrent OCSCC.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ES (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salvage Surgery (n = 39) |

No Salvage Surgery (n = 20) |

||

| At Time of Initial Diagnosis | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 62.1 (12.4) | 62.5 (10.9) | 0.37 (−5.98 to 6.73) |

| Male | 23 (59) | 16 (80) | 21.0 (−2.3 to 44.4) |

| Smoking history | |||

| Yes, >25 pack-years | 16 (42) | 7 (41) | −0.9 (−29.1 to 27.2) |

| Yes, <25 pack-years | 4 (11) | 2 (12) | 1.2 (−16.9 to 19.4) |

| No | 18 (47) | 8 (47) | −0.3 (−28.9 to 28.2) |

| Alcohol use | |||

| <21 Drinks/wk | 31 (86) | 15 (79) | −7.2 (−28.7 to 14.4) |

| >21 Drinks/wk | 5 (14) | 4 (21) | 7.2 (−14.4 to 28.7) |

| Initial T category | |||

| T1 | 19 (49) | 2 (10) | −38.7 (−59.2 to −18.3) |

| T2 | 9 (23) | 5 (25) | 1.9 (−21.2 to 25.1) |

| T3 | 2 (5) | 4 (20) | 14.9 (−4.0 to 33.7) |

| T4a | 9 (23) | 9 (45) | 21.9 (−3.6 to 47.4) |

| Initial N category | |||

| N0 | 30 (77) | 6 (30) | −46.9 (−71.0 to −22.9) |

| N1 | 2 (5) | 5 (25) | 19.9 (−0.3 to 40.1) |

| N2a | 1 (3) | 0 | −2.6 (−7.5 to 2.4) |

| N2b | 4 (10) | 8 (40) | 29.7 (6.3 to 53.2) |

| N2c | 2 (5) | 1 (5) | −0.1 (−11.9 to 11.7) |

| Initial treatment | |||

| Surgery alone | 28 (72) | 8 (40) | −31.8 (−57.5 to −6.1) |

| Surgery + RT/CRT | 11 (28) | 12 (60) | 31.8 (6.1 to 57.5) |

| At Time of Recurrence | |||

| Recurrence location | |||

| Alveolus | 8 (21) | 4 (20) | −0.5 (−22.1 to 21.1) |

| Buccal | 4 (10) | 1 (5) | −5.3 (−18.7 to 8.2) |

| Floor of mouth | 7 (18) | 0 | −18.0 (−30.0 to −5.9) |

| Retromolar trigone | 2 (5) | 1 (5) | −0.1 (−11.9 to 11.7) |

| Tongue | 14 (36) | 3 (15) | −20.9 (−42.6 to 0.8) |

| Other | 4 (10) | 11 (55) | 44.7 (21.0 to 68.5) |

| Salvage treatment | |||

| Any | 39 (100) | 11 (55) | −45.0 (−66.8 to −23.2) |

| Surgery alone | 24 (62) | 0 | −61.5 (−76.8 to −46.3) |

| Surgery + RT/CRT | 15 (38) | 0 | −38.5 (−53.7 to −23.2) |

| RT ± CT | 0 | 11 (55) | 55.0 (33.2 to 76.8) |

| None | 0 | 9 (45) | 45.0 (23.2 to 66.8) |

| Status | |||

| Alive, disease | 1 (3) | 1 (5) | 2.7 (−8.5 to 13.9) |

| Alive, no disease | 17 (44) | 1 (5) | −38.3 (−56.9 to −19.8) |

| Death, disease | 16 (41) | 15 (79) | 37.9 (14.0 to 61.9) |

| Death, no disease | 5 (13) | 2 (11) | −2.3 (−19.6 to 15.0) |

| Median follow-up, median (95% CI), y | 8.25 (5.50-9.08) | 6.33a | |

Abbreviations: CRT, chemotherapy; CT, chemotherapy; ES, effect size; OCSCC, oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma; RT, radiotherapy.

Calculation was based on 2 individuals in this group; therefore, no 95% CI could be calculated.

Of the 59 patients, 1 patient (2%) underwent salvage radiotherapy alone, 6 patients (10%) underwent salvage chemotherapy alone, and 4 patients (7%) underwent salvage chemoradiotherapy alone. Nine patients (15%) declined active treatment. Thirty-nine patients (66%) underwent surgical salvage with curative intent. Eight of these 39 patients (21%) underwent adjuvant radiotherapy following salvage surgery, and 8 patients (21%) underwent adjuvant chemoradiotherapy.

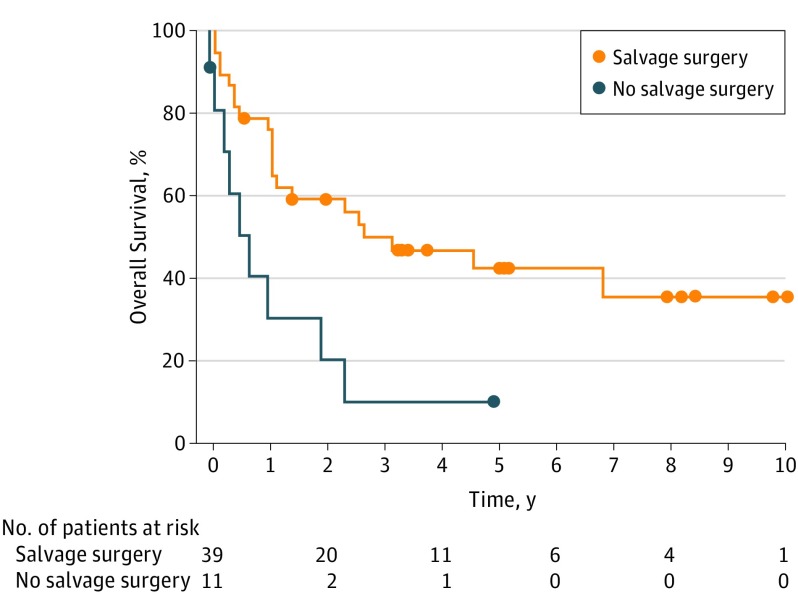

Five-year OS from the time of salvage treatment of the recurrence for all 59 patients was 36%. Patients undergoing salvage surgery had a 5-year OS of 43% (Figure 1). The median survival for patients receiving nonoperative treatment or palliation was 8 months (range, 0-66), with only 1 patient alive at 4 years (10%).

Figure 1. Overall Survival in Patients Undergoing and Not Undergoing Salvage Surgery.

Overall survival in patients with recurrent oral cavity cancer undergoing salvage surgery compared with those not undergoing salvage surgery.

Univariate Analysis

Results from the univariate analysis for the 39 patients undergoing salvage surgery with curative intent are listed in Table 2. Univariate variables that estimated OS following salvage surgery included age at first diagnosis, initial T and N categories, treatment modality of the initial primary tumor, pathologic features from the initial surgery (perineural invasion, vascular invasion, and extracapsular spread), age at the time of recurrence, recurrent T category, and pathologic factors from the salvage surgery (perineural and lymphovascular invasion as well as margin status).

Table 2. OS in Patients Undergoing Salvage Surgery for Recurrent OCSCC.

| Variable | OS, HR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|

| At Initial Diagnosis | |

| Age, ≥62 vs <62 y | 3.20 (1.20-8.45) |

| Male | 1.49 (0.62-3.60) |

| Smoking history, yes vs no | 0.64 (0.27-1.52) |

| Alcohol use, >21 vs <21 drinks/wk | 1.64 (0.47-5.68) |

| Initial T category, T3-T4 vs T1-T2 | 5.50 (2.20-13.74) |

| Initial N category, N1-N2 vs N0 | 3.07 (1.15-8.20) |

| Primary treatment | |

| Surgery + CRT vs surgery | 2.37 (0.52-10.76) |

| Surgery + RT vs surgery | 8.64 (2.93-25.47) |

| Differentiation vs well | |

| Moderate/well-moderate | 1.32 (0.51-3.43) |

| Poor/moderate-poor | 0.87 (0.22-3.39) |

| Perineural invasion | 5.68 (1.89-17.03) |

| Vascular invasion | 7.85 (2.10-29.30) |

| Margin status | |

| Close, <3 mm vs negative | 0.71 (0.24-2.13) |

| Positive vs negative | 0.37 (0.05-2.80) |

| Extracapsular spread | 8.62 (2.09-35.49) |

| At the Time of Recurrence | |

| Smoking history, yes vs no | 0.75 (0.27-2.04) |

| Alcohol use, >21 vs <21 drinks/wk | 0.86 (0.31-2.41) |

| Recurrent T category, T3-T4 vs T1-T2 | 3.29 (1.31-8.25) |

| Recurrent N category, N1-N3 vs N0 | 1.57 (0.51-4.83) |

| Second treatment | |

| Surgery + RT/CRT vs surgery | 1.67 (0.69-4.03) |

| Site of recurrence, vs tongue | |

| Alveolus | 1.48 (0.95-4.84) |

| Buccal | 3.00 (0.74-12.24) |

| Floor of mouth | 2.53 (0.77-8.34) |

| Retromolar trigone | 1.64 (0.19-13.85) |

| Other | 0.78 (0.09-6.48) |

| Reconstruction | 2.51 (0.95-6.67) |

| Nodal disease | 2.29 (0.91-5.78) |

| Differentiation vs well | |

| Moderate/well-moderate | 1.44 (0.48-4.31) |

| Poor/moderate-poor | 3.63 (0.98-13.39) |

| Perineural invasion | 2.64 (1.05-6.66) |

| Lymphatic invasion | 3.69 (1.16-11.69) |

| Vascular invasion | 4.99 (1.67-14.94) |

| Margin status | |

| Close, <3 mm vs negative | 2.15 (0.77-6.02) |

| Positive vs negative | 5.22 (1.61-16.94) |

| Extracapsular spread | 1.94 (0.50-7.56) |

Abbreviations: CRT, chemoradiotherapy; HR, hazard ratio; OCSCC, oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma; OS, overall survival; RT, radiotherapy.

Univariate analysis using Cox proportional hazards regression models predictive of OS.

Recursive Partitioning Analysis

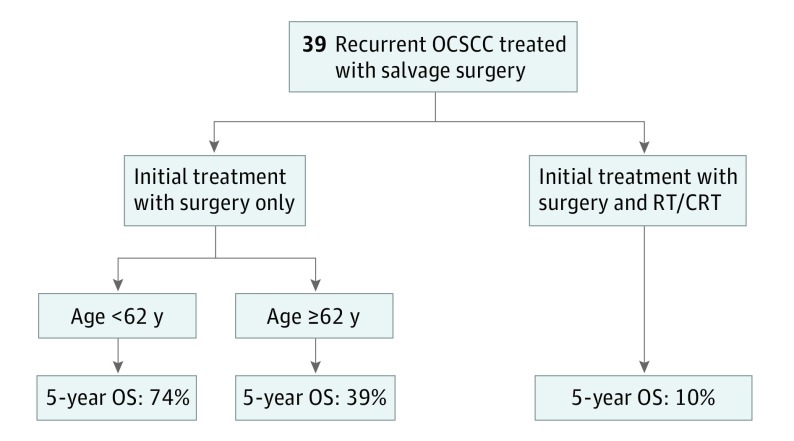

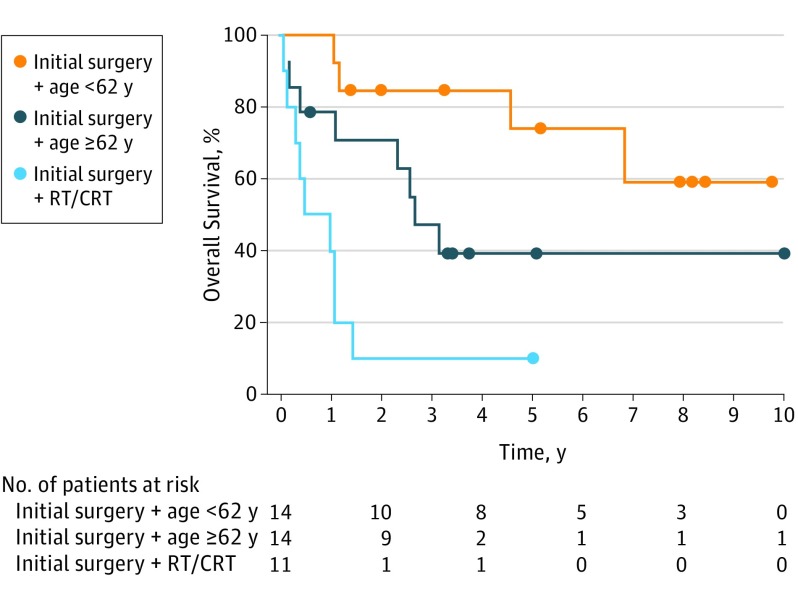

Recursive partitioning analysis demonstrated that the most important negative prognostic factor for OS was adjuvant radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy following primary surgery. Age older than 62 years was found to be the second most important negative prognostic indicator. These 2 prognostic factors allowed subdivision into 3 risk groups (Figure 2). The high-risk group consisted of patients who received prior adjuvant therapy (hazard ratio [HR], 9.41; 95% CI, 2.68-33.04). The intermediate-risk group included patients who did not receive prior adjuvant therapy and were 62 years or older (HR, 2.95; 95% CI, 0.86-10.09). The low-risk group, serving as the reference group, comprised patients who did not receive prior adjuvant therapy and were younger than 62 years. For patients who underwent salvage surgery with curative intent, the 5-year OS was 54% for those who did not receive prior adjuvant treatment and 10% for those who received adjuvant treatment following primary surgery (Figure 3). Median survival was 6 months (range, 0-60 months) for patients in the high-risk group and 31 months (range, 0-126 months) in the intermediate-risk group. In the low-risk group, median survival was not reached.

Figure 2. Recursive Partitioning Analysis of Patients Undergoing Curative Intent Salvage Surgery.

CRT indicates chemoradiotherapy; OCSCC, oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma; OS, overall survival; and RT, radiotherapy.

Figure 3. Patients Undergoing Curative Intent Salvage Surgery Using Recursive Partitioning Analysis End Points.

CRT indicates chemoradiotherapy; RT, radiotherapy.

Functional Outcomes

In patients undergoing salvage surgery, 21 patients (54%) had a gastrostomy tube inserted, with 18 patients (46%) still having a permanent gastrostomy tube at the time of the last follow-up. In these 18 patients, 7 (39%) individuals were in the high-risk group, 9 (50%) were in the intermediate-risk group, and 2 (11%) were in the low-risk group. Four patients (10%) required permanent tracheostomy: 1 patient in the high-risk group, 1 patient in the intermediate-risk group, and 2 patients in the low-risk group.

Discussion

Our study found a significant difference in prognosis in patients undergoing salvage surgery for OCSCC based on whether adjuvant therapy was received after the initial cancer surgery. Five-year OS was poor in patients whose cancer recurred when the initial treatment procedure was surgery with adjuvant radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. Given the low chance of cure with salvage therapy, surgery should be undertaken after careful consideration of the potential surgical morbidity and a realistic chance of long-term disease control. In contrast, 5-year OS was better in patients younger than 62 years whose initial treatment consisted of surgery alone.

Salvage surgery for recurrent OCSCC may result in significant morbidity. Selecting patients appropriate for surgical salvage can be challenging because the presentation of the disease is variable and consideration of preexisting comorbidities, prior treatments, and patient goals can result in complexities in decision making. Patient stratification into risk categories may be of value when counseling patients with recurrent OCSCC and determining individualized treatment.

Gañán et al performed an RPA analysis on patients with recurrent head and neck cancers and also found that the modality of initial treatment was an important indicator of patient survival. This study investigated salvage surgery in all head and neck sites and found that the modality of initial treatment was especially important for patients with advanced laryngeal cancer and local node-negative disease. However, initial treatment and prognosis vary widely between sites in the head and neck. This is, to our knowledge, the first study to utilize RPA analysis to stratify patients undergoing salvage surgery for OCSCC.

The modality of the initial treatment for our patients was offered based on the nature and initial presentation of the tumor. Therefore, patients with poor tumor biology (eg, advanced T category), advanced nodal disease, and adverse pathological features would likely receive adjuvant radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy at the time of initial treatment. This finding concurs with the findings of Kernohan et al, who demonstrated similar results when patients who were treated initially with a single modality fared better than those treated with combined modality therapy.

Age was the second most significant factor in our RPA model. This finding may be expected given the primary outcome of OS. In addition, some studies have suggested improved baseline survival in younger patients with oral cavity cancer. Other prognostic factors discovered in univariate analysis are consistent with those of similar studies. However, few studies focused on patients undergoing surgical salvage. Goto et al investigated prognostic factors after salvage surgery for patients with OCSCC in the oral tongue subsite only. In this cohort, stage, nodal status, extracapsular extension, and disease-free interval were found to be significant prognostic indicators on univariate analysis. However, in the multivariable analysis, only extracapsular spread was an independent prognostic factor for OS. In their cohort, 68% of the patients underwent primary treatment with radiotherapy only, whereas all patients in our study were treated with primary surgery with or without adjuvant therapy.

Functional outcome following treatment is a major consideration in treatment choice. The presence of a gastrostomy tube offers an objective and robust measurement of swallowing function. The overall rate of gastrostomy tube dependence in our series (46%) falls within the rate of gastrostomy tubes in the literature of 25% to 50%. However, when gastrostomy tube dependence was stratified by risk groups, the percentage of gastrostomy tube dependency in the high- and intermediate-risk groups was considerably higher. However, the rate in young patients without prior adjuvant therapy was only 15%.

Limitations

This study is primarily limited by the sample size. The population was a highly selected subset of patients who not only had recurrent OCSCC but also was deemed appropriate for curative intent salvage surgery. The strict inclusion criteria enabled a consistent study population but limited our ability to further stratify patients in the RPA model, where terminal nodes of the model were the sample size within each node. Continued patient recruitment may allow further analysis and stratification of patients according to prognosis. Findings may vary, especially in populations with different etiologic factors contributing to OCSCC, such as betel nut use or reverse smoking. Despite these limitations, our findings of diverging OS rates in 3 risk categories may help to guide discussions with patients who have recurrent OCSCC.

Conclusions

Patients undergoing salvage surgery with curative intent for recurrent OCSCC have a poor prognosis. Those who received adjuvant treatment at the time of initial treatment had the worst outcome with a 5-year OS of 10%. Patients who underwent only primary surgery for their initial tumor fared better. This marked difference in OS should be taken into consideration with patient comorbidities, potential morbidity of surgery, and patient goals when deciding treatment options for patients with recurrent OCSCC.

eTable. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Having Recurrence Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koo BS, Lim YC, Lee JS, Choi EC. Recurrence and salvage treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Oral Oncol. 2006;42(8):789-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goto M, Hanai N, Ozawa T, et al. . Prognostic factors and outcomes for salvage surgery in patients with recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2016;12(1):e141-e148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin Y-C, Hsiao J-R, Tsai S-T. Salvage surgery as the primary treatment for recurrent oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2004;40(2):183-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ord RA, Kolokythas A, Reynolds MA. Surgical salvage for local and regional recurrence in oral cancer. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(9):1409-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun G-W, Tang E-Y, Yang X-D, Hu Q-G. Salvage treatment for recurrent oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20(4):1093-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zafereo M. Surgical salvage of recurrent cancer of the head and neck. Curr Oncol Rep. 2014;16(5):386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong LY, Wei WI, Lam LK, Yuen APW. Salvage of recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma after primary curative surgery. Head Neck. 2003;25(11):953-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edge SBDR, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gañán L, López M, García J, Esteller E, Quer M, León X. Management of recurrent head and neck cancer: variables related to salvage surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273(12):4417-4424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kernohan MD, Clark JR, Gao K, Ebrahimi A, Milross CG. Predicting the prognosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma after first recurrence. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136(12):1235-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiboski CH, Schmidt BL, Jordan RCK. Tongue and tonsil carcinoma: increasing trends in the US population ages 20-44 years. Cancer. 2005;103(9):1843-1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Monsjou HS, Lopez-Yurda MI, Hauptmann M, van den Brekel MWM, Balm AJM, Wreesmann VB. Oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in young patients: the Netherlands Cancer Institute experience. Head Neck. 2013;35(1):94-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee C-C, Ho H-C, Chen H-L, Hsiao S-H, Hwang J-H, Hung S-K. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue in young patients: a matched-pair analysis. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127(11):1214-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Udeabor SE, Rana M, Wegener G, Gellrich N-C, Eckardt AM. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and the oropharynx in patients less than 40 years of age: a 20-year analysis. Head Neck Oncol. 2012;4:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liao C-T, Chang JT-C, Wang H-M, et al. . Salvage therapy in relapsed squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity: how and when? Cancer. 2008;112(1):94-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Having Recurrence Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma