Abstract

Importance

Adjuvant chemotherapy offers a survival benefit to a number of staging scenarios in non–small-cell lung cancer. Variable recovery from lung cancer surgery may delay a patient’s ability to tolerate adjuvant chemotherapy, yet the urgency of chemotherapy initiation is unclear.

Objective

To assess differences in survival according to the time interval between non–small-cell lung cancer resection and the initiation of postoperative chemotherapy to determine the association between adjuvant treatment timing and efficacy.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective observational study examined treatment-naive patients with completely resected non–small-cell lung cancer who received postoperative multiagent chemotherapy between 18 and 127 days after resection between January 2004 and December 2012. The study population was limited to patients with lymph node metastases, tumors 4 cm or larger, or local extension. Patients were identified from the National Cancer Database, a hospital-based tumor registry that captures more than 70% of incident lung cancer cases in the United States. The association between time to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy and survival was evaluated using Cox models with restricted cubic splines.

Exposures

Adjuvant chemotherapy administered at different time points after surgery.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy according to time to initiation after surgery.

Results

A total of 12 473 patients (median [interquartile range] age, 64 [57-70] years) were identified: 3073 patients (25%) with stage I disease; 5981 patients (48%), stage II; and 3419 patients (27%), stage III. A Cox model with restricted cubic splines identified the lowest mortality risk when chemotherapy was started 50 days postoperatively (95% CI, 39-56 days). Initiation of chemotherapy after this interval (57-127 days; ie, the later cohort) did not increase mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 1.037; 95% CI, 0.972-1.105; P = .27). Furthermore, in a Cox model of 3976 propensity-matched pairs, patients who received chemotherapy during the later interval had a lower mortality risk than those treated with surgery only (HR, 0.664; 95% CI, 0.623-0.707; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

In the National Cancer Database, adjuvant chemotherapy remained efficacious when started 7 to 18 weeks after non–small-cell lung cancer resection. Patients who recover slowly from non–small-cell lung cancer surgery may still benefit from delayed adjuvant chemotherapy started up to 4 months after surgery.

This study assesses differences in survival according to the time interval between non–small-cell lung cancer resection and the initiation of postoperative chemotherapy to determine the association between adjuvant treatment timing and efficacy.

Key Points

Question

Does delaying the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy after non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) resection affect its efficacy?

Findings

In this retrospective study of 12 473 patients with NSCLC from the National Cancer Database, adjuvant chemotherapy given later (57–127 days) in the postoperative period was not associated with mortality. Furthermore, patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy later had a significantly better survival when compared with patients treated with surgery alone.

Meaning

Patients with a delayed recovery from NSCLC resection may benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy started up to 4 months after surgery.

Introduction

Lung cancer is a particularly aggressive disease, resulting in over 158 000 deaths a year in the United States. Even patients with locoregionally confined non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that undergo complete surgical resection (negative surgical margins) carry a significant risk for systemic failure. In an effort to reduce the risk of NSCLC recurrence, chemotherapy has been administered in the postoperative period with encouraging results. More specifically, a number of clinical trials and meta-analyses have established a survival benefit when chemotherapy is given to patients who underwent surgery and have lymph node metastases or have larger or locally invasive tumors. Consequently, adjuvant chemotherapy has become a standard recommendation for patients with NSCLC with lymph node metastases, tumors 4 cm or larger, or extensive local invasion.

While a consensus has been established regarding the indications for adjuvant chemotherapy, the optimal timing following surgical resection remains poorly defined. Many clinicians endorse initiating chemotherapy within 6 weeks of surgical resection. However, patients vary considerably in their ability to tolerate adjuvant therapy while recovering from a lung cancer resection. Multiple factors including patient health, extent and approach of surgical resection, and the occurrence of postoperative complications may affect a patient’s ability to tolerate systemic therapy in the perioperative period.

Recently, concerns have emerged over the possibility for delays in the administration of chemotherapy to compromise the efficacy of adjuvant treatment. For example, in colon cancer and breast cancer, delays in the initiation of chemotherapy have been associated with decreased overall survival (OS). Patients with lung cancer in particular may be slow to regain their preoperative performance status after surgery, secondary to advanced age, prevalence of smoking-related lung disease, and higher risk for postoperative complications. Therefore, the relationship between the time to initiate adjuvant chemotherapy and its effectiveness is highly relevant to clinical practice.

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) is one of the largest and most comprehensive clinical oncology registries in the world, capturing more than 70% of incident lung cancer cases in the United States with robust long-term follow-up. Furthermore, the NCDB contains detailed treatment information including time intervals between different components of multimodal therapy (eg, surgery plus chemotherapy, radiotherapy, etc). Therefore, the NCDB is uniquely suited to analyze the relationship between time to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy in NSCLC and long-term outcomes. We evaluated the relationship between postoperative chemotherapy timing and 5-year mortality, comparing results with patients treated with surgery alone, to better understand the impact of treatment delay on the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy for NSCLC.

Methods

Data Source

The NCDB is a hospital-based tumor registry managed by the American College of Surgeons in collaboration with the American Cancer Society. The institutional review board of the Yale School of Medicine approved this study with consent waived.

Study Population

The NCDB Participant User File (version 2013) was queried for treatment-naive (ie, no preoperative therapy) patients 20 years or older, managed with adjuvant chemotherapy after complete resection (ie, negative margins) of NSCLC. Patients diagnosed with invasive NSCLC from January 2004 to December 2012 for whom that diagnosis represented their first malignancy were included. Only patients who underwent lobectomy or pneumonectomy for pathological stage I, II, or III NSCLC and received multiagent chemotherapy were included. To be consistent with current treatment indications for adjuvant chemotherapy, patients with stage I disease and tumors smaller than 4 cm were excluded. Patients with incomplete pathologic staging or missing treatment or follow-up information, those with carcinoma in-situ or carcinoid, and those treated with adjuvant radiotherapy were also excluded. To minimize the impact of outliers, patients in the top and bottom 2% with respect to time to initiate adjuvant chemotherapy were excluded from the study. Finally, 30-day mortalities were excluded from all groups, as patients undergoing chemotherapy must have survived the perioperative period in order to receive chemotherapy (ie, immortal time bias). Recognizing the greater potential for immortal time bias with delayed chemotherapy, the comparative analyses (Cox model and propensity matching) were repeated including only those patients known to be alive at 120 days (all groups landmarked at 120 days) with no meaningful change in results (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

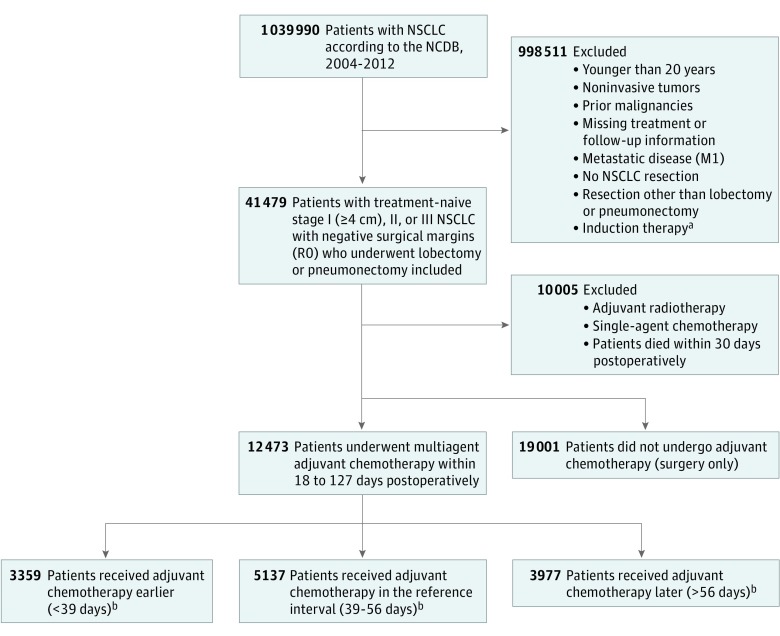

A separate cohort of patients with surgically managed NSCLC was created using the same selection criteria but including patients who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy and were treated with surgery alone. The selection steps are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Diagram of Study Cohort Selection Steps.

NSCLC indicates non–small-cell lung cancer; NCDB, National Cancer Database.

aChemotherapy, radiotherapy or chemoradiation.

bDays from NSCLC resection to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Data Elements

A complete list of the variables contained in the NCDB can be found online. Independent variables included: facility type and location, age, sex, race, Hispanic origin, insurance status, income (ie, median income of the patient’s zip code area), education (ie, percent of people in the patient’s zip code area with no high-school diploma), area of residence (based on the patients reported county and state), Charlson-Deyo (CD) score (modified by NCDB to 3 groups [0, 1, ≥2]), year of diagnosis, tumor primary site, laterality, histological type, grade, tumor size, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 6th edition pathological stage, type of resection (ie, lobectomy, pneumonectomy), length of surgical inpatient stay (categorized in ≤14 days and >14 days to represent extended length of stay), readmission within 30 days of surgical discharge, and 90-day mortality. To calculate the number of days to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy, start dates for chemotherapy were compared with those of the surgical procedure.

The study period was affected by a transition from the 6th edition to the 7th edition of the AJCC lung cancer staging system, reflected in the NCDB starting in 2010. Since patients coded prior to 2010 did not contain sufficient staging data for conversion to the 7th AJCC edition, a homogenous study group was created by converting patients diagnosed between 2010 and 2012 to the corresponding 6th edition stage.

Statistical Analysis

Cox Model With Restricted Cubic Splines

To evaluate the impact of time to adjuvant chemotherapy on survival, a multivariable Cox model with restricted cubic splines (RCS) was built. The use of RCS has been widely described as a valid strategy to analyze the relationship between survival and independent variables. Furthermore, RCS has recently been used to study the relation between survival and treatment in patients with cancer. Restricted cubic splines are a smoothly joined sum of polynomial functions that do not assume linearity of the relationship between covariates and the response (ie, survival). This technique provides greater flexibility for fitting data and modeling more complex relationships between survival and the variable of interest, while adjusting for other covariates. Additionally, RCS permits identification of the risk function inflexion point (ie, threshold). The Cox model built to evaluate the relationship between time to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy and survival was adjusted for facility type and location, age, sex, CD Score, insurance, income, education, year of diagnosis, tumor size, primary site, histological type, grade, pathological stage and type of resection. The spline was defined using three knots at the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles. The threshold was determined as the point in time with the smallest hazard ratio (HR). The 95% CI was derived by bootstrap resampling.

Stratification of Cohort by Chemotherapy Timing

Rather than dichotomize our population according to a single cut-point (ie, 50 days between surgery and start of chemotherapy), we felt it was more relevant to clinical practice to evaluate chemotherapy timing within intervals, as the chemotherapy effect was unlikely to have an abrupt spike and fall in efficacy across time. The interval of time between surgery and the initiation of chemotherapy that corresponded to the RCS-determined lowest mortality was considered the reference interval (39-56 days). Patients in whom chemotherapy was started prior to this reference interval were considered the earlier group (18-38 days), while patients who started chemotherapy after the reference interval were considered the later group (57-127 days). An adjusted survival analysis was performed using a Cox model with 3 levels for adjuvant timing (earlier, reference interval, and later).

Propensity Matching: Surgery With Adjuvant Chemotherapy vs Surgery Alone

To validate the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in this context, the patients in the 3 time cohorts were compared with patients treated with surgery only (SO). There was an imbalance in the number of patients within the adjuvant and SO groups; with 3359 patients in the earlier group, 5137 in the reference interval group, and 3977 in the later chemotherapy group, while the SO group had 19 001 patients. Large imbalances in risk factors can lead to spurious treatment-effect findings. In addition, adjuvant chemotherapy was evolving as the standard of care within this study period, raising the potential for treatment bias between the adjuvant and SO cohorts. Therefore, we used 1:1 propensity matching in an effort to isolate the effect of adjuvant chemotherapy in similar patient populations. Patients were matched on facility type and location, age, sex, race, Hispanic origin, CD score, insurance, income, education, area of residence, year of diagnosis, tumor size, primary site, laterality, histological type, grade, pathological stage, and type of resection. The standardized difference of each variable was calculated and found to be less than 0.1. A separate propensity matching was performed for each time-based cohort of patients who underwent adjuvant chemotherapy (earlier, reference interval, later) and patients treated with SO. The propensity match was done using a previously described SAS macro (SAS Institute Inc). The 5-year mortality was compared in a Cox model using the SO group as the reference.

Logistic Regression for Later Initiation of Chemotherapy

To identify factors independently associated with delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy (ie, the later group), multivariable logistic regression models were built (considering all variables listed in data elements except for 90-day mortality) accounting for clustering at the hospital level. Backward elimination was implemented for model refinement with a type III P value of .2 or less for inclusion in the model. Tumor size was forced into the model as it was considered to have particular clinical relevance.

Bivariate analyses were performed using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test (where χ2 could not be used because of low frequencies) for categorical variables and the Student t test and ANOVA for continuous variables. A P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant, and all statistical tests were 2-sided. Survival times were calculated from the day of surgery. Missing values in any variable were coded as unknown for multivariable modeling purposes. Cox proportional hazards models were refined using backward elimination. Visual inspections of log-log plots of the survival functions were performed to evaluate violations of the proportional hazards assumption. Standardized difference, RCS, and a post hoc power analysis were calculated using R version 3.2.2 (R Foundation). All other statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 31 474 patients met inclusion criteria; 12 473 who received adjuvant chemotherapy and 19 001 treated with SO. Among those treated with adjuvant therapy, the median time to chemotherapy initiation was 48 days (interquartile range [IQR], 37-62; range, 18-127 days). The characteristics of the earlier, reference interval, and later chemotherapy subgroups and the patients treated with SO are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics of the Chemotherapy Time-Based Groups.

| Characteristic | No. (%)a | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earlier (<39 d; n = 3359) | Reference Interval (39-56 d; n = 5137) | Later (>56 d; n = 3977) | Surgery Only (n = 19 001) | ||

| Facility type | <.001 | ||||

| Academic/research program | 910 (27) | 1710 (33) | 1608 (40) | 6558 (35) | |

| Nonacademic programb | 2449 (73) | 3427 (67) | 2369 (60) | 12 443 (65) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 63 (56-69) | 64 (57-70) | 65 (58-71) | 70 (63-76) | <.001 |

| Sex | <.001 | ||||

| Male | 1849 (55) | 2737 (53) | 2058 (52) | 10 894 (57) | |

| Female | 1510 (45) | 2400 (47) | 1919 (48) | 8107 (43) | |

| Race | <.001 | ||||

| White | 3033 (90) | 4484 (87) | 3411 (86) | 16 878 (89) | |

| Nonwhite | 326 (10) | 653 (13) | 566 (14) | 2123 (11) | |

| Hispanic origin | .02 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 3020 (90) | 4654 (91) | 3550 (90) | 17 071 (90) | |

| Hispanic origin | 60 (2) | 92 (2) | 91 (2) | 462 (2) | |

| Unknown | 279 (8) | 391 (8) | 336 (8) | 1468 (8) | |

| Insurance status | <.001 | ||||

| Not insured | 79 (2) | 133 (3) | 142 (4) | 400 (2) | |

| Private insurance | 1568 (47) | 2234 (44) | 1526 (38) | 5032 (26) | |

| Medicaid | 171 (5) | 281 (5) | 257 (6) | 834 (4) | |

| Medicare | 1460 (43) | 2376 (46) | 1976 (50) | 12 269 (65) | |

| Other government | 41 (1) | 46 (1) | 39 (1) | 183 (1) | |

| Status unknown | 40 (1) | 67 (1) | 37 (1) | 283 (1) | |

| Education, %c | <.001 | ||||

| ≥21 | 510 (15) | 739 (14) | 679 (17) | 3487 (18) | |

| 13-20.9 | 910 (27) | 1468 (29) | 1096 (28) | 5463 (29) | |

| 7-12.9 | 1166 (35) | 1755 (34) | 1327 (33) | 6158 (32) | |

| <7 | 720 (21) | 1087 (21) | 805 (20) | 3455 (18) | |

| Unknown | 53 (2) | 88 (2) | 70 (2) | 438 (2) | |

| Area of residenced | <.001 | ||||

| Metropolitan | 2596 (77) | 3930 (77) | 3116 (78) | 14 322 (75) | |

| Urban | 561 (17) | 882 (17) | 658 (17) | 3379 (18) | |

| Rural | 90 (3) | 139 (3) | 69 (2) | 495 (3) | |

| Unknown | 112 (3) | 186 (4) | 134 (3) | 805 (4) | |

| Charlson-Deyo score | <.001 | ||||

| 0 | 1832 (55) | 2780 (54) | 2085 (52) | 9283 (49) | |

| 1 | 1160 (35) | 1777 (35) | 1415 (36) | 6887 (36) | |

| ≥2 | 367 (11) | 580 (11) | 477 (12) | 2831 (15) | |

| Year of diagnosis | <.001 | ||||

| 2004 | 277 (8) | 344 (7) | 308 (8) | 2431 (13) | |

| 2005 | 405 (12) | 482 (9) | 373 (9) | 2314 (12) | |

| 2006 | 427 (13) | 553 (11) | 381 (10) | 2224 (12) | |

| 2007 | 365 (11) | 539 (10) | 443 (11) | 2170 (11) | |

| 2008 | 353 (11) | 581 (11) | 463 (12) | 2139 (11) | |

| 2009 | 335 (10) | 515 (10) | 458 (12) | 2056 (11) | |

| 2010 | 331 (10) | 659 (13) | 469 (12) | 1857 (10) | |

| 2011 | 396 (12) | 695 (14) | 524 (13) | 1909 (10) | |

| 2012 | 470 (14) | 769 (15) | 558 (14) | 1901 (10) | |

| Primary site | <.001 | ||||

| Upper lobe | 1953 (58) | 2937 (57) | 2267 (57) | 10 632 (56) | |

| Middle lobe | 129 (4) | 228 (4) | 174 (4) | 770 (4) | |

| Lower lobe | 1150 (34) | 1730 (34) | 1312 (33) | 6749 (36) | |

| Overlapping lesion | 70 (2) | 152 (3) | 150 (4) | 512 (3) | |

| Lung, NOS | 57 (2) | 90 (2) | 74 (2) | 338 (2) | |

| Tumor laterality | .04 | ||||

| Right | 1842 (55) | 2832 (55) | 2295 (58) | 10 866 (57) | |

| Left | 1511 (45) | 2300 (45) | 1676 (42) | 8112 (43) | |

| Unknown | e | e | e | 23 (0) | |

| Tumor histological type | <.001 | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1960 (58) | 2863 (56) | 2057 (52) | 8800 (46) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1051 (31) | 1772 (35) | 1496 (38) | 8274 (44) | |

| Large cell carcinoma | 158 (5) | 223 (4) | 185 (5) | 853 (4) | |

| Otherf | 190 (6) | 279 (5) | 239 (6) | 1074 (6) | |

| Tumor grade | <.001 | ||||

| 1 | 175 (5) | 263 (5) | 176 (4) | 1228 (6) | |

| 2 | 1345 (40) | 2113 (41) | 1642 (41) | 7761 (41) | |

| 3 | 1633 (49) | 2446 (48) | 1902 (48) | 8727 (46) | |

| 4 | 107 (3) | 131 (3) | 98 (3) | 606 (3) | |

| Undetermined | 99 (3) | 184 (4) | 159 (4) | 679 (4) | |

| Tumor pathologic stage | <.001 | ||||

| I | 766 (23) | 1257 (25) | 1050 (27) | 9376 (49) | |

| II | 1650 (49) | 2530 (49) | 1801 (45) | 6189 (33) | |

| III | 943 (28) | 1350 (26) | 1126 (28) | 3436 (18) | |

| Tumor size, median (IQR), cm | 4.0 (2.5-5.5) | 4.0 (2.7-5.8) | 4.3 (2.8-6.0) | 4.5 (3.5-5.9) | <.001 |

| Type of resection | <.001 | ||||

| Lobectomy | 2967 (88) | 4465 (87) | 3401 (86) | 16 984 (89) | |

| Pneumonectomy | 392 (12) | 672 (13) | 576 (15) | 2017 (11) | |

| Length of inpatient stay, d | <.001 | ||||

| ≤14 | 3295 (98) | 4982 (97) | 3688 (93) | 16 784 (88) | |

| >14 | 64 (2) | 155 (3) | 289 (7) | 2217 (12) | |

| Readmission within 30 d of discharge | <.001 | ||||

| No | 3031 (90) | 4674 (91) | 3582 (90) | 17 141 (90) | |

| Unplanned | 104 (3) | 138 (3) | 193 (5) | 1031 (5) | |

| Planned | 138 (4) | 165 (3) | 71 (2) | 429 (2) | |

| Planned and unplanned | e | e | e | 25 (0) | |

| Unknown | 82 (2) | 154 (3) | 126 (3) | 375 (2) | |

| Ninety day mortality, d | <.001 | ||||

| Alive >90 | 3308 (99) | 5076 (99) | 3948 (99) | 17 834 (94) | |

| Died ≤90 | 41 (1) | 44 (1) | 21 (1) | 1041 (5) | |

| Unknown | 10 (0) | 17 (0) | e | 126 (1) | |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NOS, not otherwise specified; ellipses, not applicable or no data available.

Percentages might not add up to 100% due to approximation.

Includes Community Cancer Program, Comprehensive Community Cancer Program, Integrated Network Cancer Program and other specified types of cancer programs.

Percent of people in the patient’s zip code area with no high-school diploma.

Based on patient’s zip code area.

Frequencies less than 10 not reported per National Cancer Database guidelines.

Non–small cell not further defined.

Adjusted Mortality by Time to Initiation of Adjuvant Chemotherapy

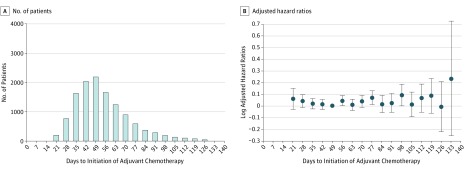

As an initial exploration into the relationship between adjuvant chemotherapy timing and outcome, an adjusted Cox model was created with adjuvant chemotherapy timing included as a categorical variable (separated into 7-day intervals). The median follow-up for surviving patients from day of surgery was 46 months (IQR, 28-73). Patients in the 49 days interval were used as the reference as they represented the cohort median for chemotherapy timing. The plotted HRs are shown in Figure 2B. No consistent correlation between mortality risk and chemotherapy timing was observed.

Figure 2. Mortality Risk Associated With Time to Initiation of Adjuvant Chemotherapy.

The time interval between surgical resection and the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy is indicated in days. A, The number of patients is shown. B, The log of the hazard ratios derived from an adjusted Cox model is shown (dots correspond to log of hazard ratio and whiskers correspond to log of 95% CI). The reference used was 49 days.

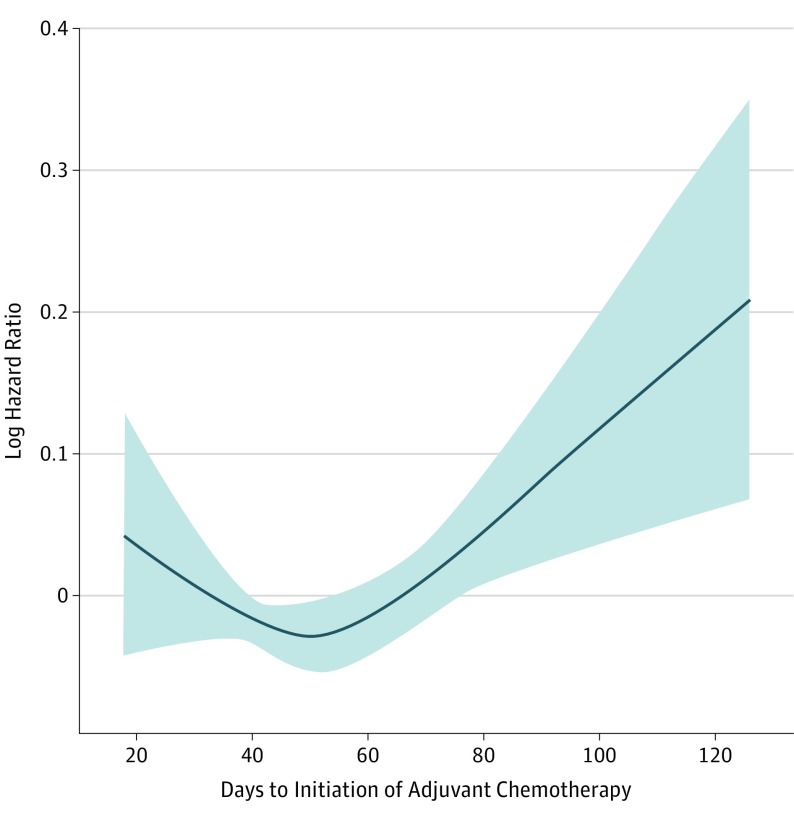

Restricted Cubic Splines to Identify Adjuvant Timing Associated With Lowest Mortality Risk

To more rigorously evaluate the relationship between chemotherapy timing and survival, a Cox model with RCS was created yielding an inflection point in the risk function at 50 days (Figure 3). The population was stratified according to 3 timing intervals (earlier, reference interval, and later) defined around the RCS-derived inflection point. The reference interval refers to patients that started chemotherapy in the timeframe corresponding to the 95% CI for the RCS inflection point (39-56 days). The earlier subgroup refers to patients whose time to initiation of chemotherapy was shorter than the reference interval (18-38 days), while the later subgroup was comprised of patients who started chemotherapy after the reference interval (57-127 days).

Figure 3. Restricted Cubic Spline Modeling of the Relationship Between Time to Initiation of Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Mortality Risk.

The log of the hazard ratios derived from a multivariate Cox model is shown on the y-axis. The 95% CIs of the adjusted hazard ratios are represented by the shaded area. The risk function demonstrates an inflection point at 50 days.

Adjuvant Efficacy Relative to the Reference Interval

Unadjusted KM 5-year OS estimates were not significantly different between the 3 groups (earlier, 53%; reference interval, 55%; later, 53%; log-rank P = .23). A post hoc power analysis demonstrated a 91% probability of finding a 2% difference in 5-year OS between adjuvant chemotherapy groups. Furthermore, an adjusted Cox model did not show differences in survival between the earlier and later groups when compared with the reference interval (earlier HR, 1.009; 95% CI, 0.944-1.080; P = .79 and later HR, 1.037; 95% CI, 0.972-1.105; P = .27) (Table 2).

Table 2. Cox Proportional Hazards Model of Patients Who Underwent Adjuvant Chemotherapy.

| Covariate | No. | HR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjuvant chemotherapy timing | |||

| Reference interval (39-56 d) | 5137 | [Reference] | |

| Earlier (<39 d) | 3359 | 1.009 (0.944-1.080) | .79 |

| Later (>56 d) | 3977 | 1.037 (0.972-1.105) | .27 |

| Facility type | |||

| Academic/research program | 4228 | [Reference] | |

| Nonacademic programa | 8245 | 1.082 (1.020-1.148) | .01 |

| Age | 1.019 (1.016-1.023) | <.001 | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 5829 | [Reference] | |

| Male | 6644 | 1.249 (1.181-1.322) | <.001 |

| Hispanic origin | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 11 224 | [Reference] | |

| Hispanic origin | 243 | 0.731 (0.580-0.922) | .01 |

| Unknown | 1006 | 0.989 (0.899-1.088) | .82 |

| Insurance status | |||

| Medicare | 5812 | [Reference] | |

| Medicaid | 709 | 1.170 (1.026-1.335) | .02 |

| Not Insured | 354 | 1.027 (0.853-1.235) | .78 |

| Other government | 126 | 1.294 (0.984-1.701) | .07 |

| Private insurance | 5328 | 0.893 (0.831-0.959) | .002 |

| Status unknown | 144 | 0.909 (0.701-1.179) | .47 |

| Income, $b | |||

| >63 000 | 3277 | [Reference] | |

| 48 000-62 999 | 3471 | 1.072 (0.994-1.156) | .07 |

| 38 000-47 999 | 3145 | 1.131 (1.047-1.221) | .002 |

| <38 000 | 2363 | 1.172 (1.079-1.273) | <.001 |

| Unknown | 217 | 2.262 (1.889-2.708) | <.001 |

| Charlson-Deyo score | |||

| 0 | 6697 | [Reference] | |

| 1 | 4352 | 1.138 (1.073-1.208) | <.001 |

| ≥2 | 1424 | 1.336 (1.228-1.454) | <.001 |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 2004 | 929 | [Reference] | |

| 2005 | 1260 | 0.983 (0.879-1.098) | .76 |

| 2006 | 1361 | 0.970 (0.868-1.084) | .59 |

| 2007 | 1347 | 0.967 (0.864-1.083) | .57 |

| 2008 | 1397 | 0.893 (0.795-1.002) | .06 |

| 2009 | 1308 | 0.907 (0.804-1.024) | .11 |

| 2010 | 1459 | 0.784 (0.691-0.889) | <.001 |

| 2011 | 1615 | 0.825 (0.724-0.939) | .004 |

| 2012 | 1797 | 0.856 (0.743-0.987) | .03 |

| Primary site | |||

| Upper lobe | 7157 | [Reference] | |

| Middle lobe | 531 | 1.158 (1.015-1.320) | .03 |

| Lower lobe | 4192 | 1.162 (1.096-1.232) | <.001 |

| Overlapping lesion | 372 | 0.891 (0.750-1.057) | .19 |

| Lung, NOS | 221 | 0.960 (0.776-1.188) | .71 |

| Tumor histological type | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 6880 | [Reference] | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 4319 | 0.844 (0.792-0.898) | <.001 |

| Large cell carcinoma | 566 | 1.181 (1.042-1.338) | .009 |

| Otherc | 708 | 1.017 (0.907-1.139) | .78 |

| Tumor pathological stage | |||

| I | 3073 | [Reference] | |

| II | 5981 | 1.582 (1.466-1.708) | <.001 |

| III | 3419 | 2.081 (1.918-2.257) | <.001 |

| Tumor size | 1.002 (1.001-1.002) | <.001 | |

| Type of resection | |||

| Lobectomy | 10 833 | [Reference] | |

| Pneumonectomy | 1640 | 1.132 (1.043-1.230) | .003 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NOS, not otherwise specified.

Includes Community Cancer Program, Comprehensive Community Cancer Program, Integrated Network Cancer Program, and other specified types of cancer programs.

Based on patient zip code area.

Non–small cell not further defined.

Impact of Chemotherapy Timing on Efficacy of Adjuvant Over Surgery Alone

To confirm the effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy, each adjuvant chemotherapy subgroup (earlier, reference interval, later) was compared with similarly staged patients (stage I ≥4cm, stage II, and stage III) treated with SO (Table 1). A propensity-matched analysis was performed resulting in well-balanced pairs (earlier, 3277 pairs; reference interval, 4967; later, 3976) (eTables 1-3 in the Supplement). Univariate Cox models of propensity-matched pairs (with SO as the reference) suggested that the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy, regardless of time interval relative to surgery, was associated with a lower mortality risk when compared with SO (earlier HR, 0.672; 95% CI, 0.626-0.720; P < .001; reference interval HR, 0.645; 95% CI, 0.608-0.683; P < .001; later HR, 0.664; 95% CI, 0.623-0.707; P < .001). Kaplan-Meier survival analyses with log-rank test of propensity-matched patients and multivariate Cox Proportional hazards models of unmatched patients demonstrated similar findings (data available on request).

The survival analyses were landmarked at 120 days to determine the impact of immortal time bias on the results. The unadjusted KM 5-year OS for the earlier group was 54%; reference interval group, 56%; and the later group, 54% (log-rank P = .23). The landmarked adjusted Cox model demonstrated a similar mortality risk of earlier (HR, 1.003; 95% CI, 0.937-1.074; P = .93) and later (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.974-1.111; P = .24) chemotherapy relative to the reference interval group (eTable 4 in the Supplement). The univariate Cox models of the chemotherapy groups propensity matched to the SO group showed an HR of 0.752 for the earlier group (95% CI, 0.700-0.809; P < .001); an HR of 0.709 for the reference interval group (95% CI, 0.668-0.753; P < .001); and an HR of 0.737 for the later group (95% CI, 0.690-0.787; P < .001) when compared with SO.

Predictors of Later Initiation of Adjuvant Chemotherapy

In an attempt to understand the factors that influence chemotherapy timing, a multivariate logistic regression was performed to identify predictors of later initiation (>56 days) of adjuvant chemotherapy (eTable 5 in the Supplement). Increased age, being nonwhite, having Medicaid or no insurance, lower education, squamous cell carcinoma, undetermined grade, pneumonectomy resection, extended length of stay (>14 days), and unplanned 30-day readmission were significant predictors of delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Discussion

The current study tested the hypothesis that chemotherapy remained efficacious when given outside of the traditional postoperative window, in hopes of providing greater flexibility for clinicians to allow patients to recover from surgery when needed. The timing of adjuvant chemotherapy was stratified relative to a mathematically derived window (ie, reference interval [39-56 days]). This timeframe is remarkably consistent with the 6 to 9 week window for the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy mandated by many of the NSCLC adjuvant chemotherapy trials that have shaped the current standard of care. Although most (41%) of our population received adjuvant chemotherapy within this interval, 32% of our cohort initiated chemotherapy more than 56 days after surgery. As one might expect, those who started chemotherapy later were more likely to have a prolonged length of inpatient stay and to be readmitted, suggesting they were more likely to have experienced a challenging postoperative course. Interestingly, several sociodemographic factors (advanced age, uninsured status, low education) were independent predictors for later administration of chemotherapy, potentially illustrating socioeconomic barriers to timely care.

Our key findings with respect to adjuvant timing can be summarized as: (1) later chemotherapy timing (57-127 days postoperatively) did not consistently compromise survival expectations (compared with 39-56 days); and (2) patients who received chemotherapy later still had lower risk of mortality than those treated with SO. These findings indicate that patients who receive adjuvant chemotherapy up to 4 months after surgery may continue to derive benefit from chemotherapy. This conclusion is supported by several smaller series for NSCLC which did not identify a difference in chemotherapy efficacy according to the time administered. More specifically, Booth et al and Ramsden et al analyzed the effect by using cut-off points based on the NSCLC adjuvant trials and found no survival differences in patients with a delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy. Likewise, Zhu et al, using a statistically derived threshold, analyzed this effect in patients with stage IIIA NSCLC and found that time to adjuvant chemotherapy had no impact on disease-free survival.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations in addition to those commonly associated with retrospective studies. First, the NCDB captures the time of chemotherapy initiation but does not code whether chemotherapy was delayed for specific reasons (eg, surgical complication). As a result, our data indicates that delays in chemotherapy do not preclude a survival benefit, but we cannot predict the efficacy for any specific clinical scenario that affects adjuvant chemotherapy timing (eg, delay for pulmonary embolism). Additionally, the NCDB does not capture information on specific chemotherapy regimens. Although the cohort was limited to patients that received multiagent chemotherapy, unknown differences in specific agents and dosimetry may impact survival. Furthermore, the NCDB does not possess information on cancer-specific survival, and as such our results are limited to OS. Thus, delays in chemotherapy might not impact OS but could have an impact on recurrence-free survival. Finally, it is possible that the comparison groups differed in characteristics not embedded in the NCDB (performance status, pulmonary function tests, etc) that could potentially impact the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy. This bias may disproportionately affect the SO cohort, as this patient subgroup appeared to be eligible for adjuvant chemotherapy but did not receive it. Recognizing that the standard of care evolved during the study period, failure to receive adjuvant chemotherapy may reflect other risk factors with the potential to affect OS (eg, poor health, major postoperative complication, treating team unaware of practice standards).

While we believe these results indicate that chemotherapy remains effective when given up to 4 months postoperatively, these findings should not be interpreted to mean that chemotherapy has an equivalent effect, irrespective of when it is given. Although our study population was large and the post hoc analysis indicated appropriate statistical power, the chemotherapy effect is relatively small (5% difference in survival). Therefore, it is possible that a small but significant difference in survival exists based on when chemotherapy is given but is not able to be appreciated within this data set.

Conclusions

Patients with completely resected NSCLC in the NCDB continue to benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy when given outside the traditional postoperative window. Clinicians should still consider chemotherapy in appropriately selected patients that are healthy enough to tolerate it, up to 4 months after NSCLC resection. Further study is warranted to confirm these findings.

eTable 1. Patient Characteristics of the Propensity-Matched Pairs of Surgery Only and “Earlier” Adjuvant Chemotherapy Group.

eTable 2. Patient Characteristics of the Propensity-Matched Pairs of Surgery Only and “Reference Interval” Adjuvant Chemotherapy Group.

eTable 3. Patient Characteristics of the Propensity-Matched Pairs of Surgery Only and “Later” Adjuvant Chemotherapy Group.

eTable 4. Cox Proportional Hazards Model of Adjuvant Chemotherapy Patients “Landmarked” at 120 Days After Surgery.

eTable 5. Multivariate Logistic Regression Modeling of Predictors of “Later” (>56 Days) Initiation of Adjuvant Chemotherapy.

References

- 1.Mohammed N, Kestin LL, Grills IS, et al. . Rapid Disease Progression With Delay in Treatment of Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79(2):466-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fedor D, Johnson WR, Singhal S. Local recurrence following lung cancer surgery: incidence, risk factors, and outcomes. Surg Oncol. 2013;22(3):156-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arriagada R, Bergman B, Dunant A, Le Chevalier T, Pignon JP, Vansteenkiste J; International Adjuvant Lung Cancer Trial Collaborative Group . Cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(4):351-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winton T, Livingston R, Johnson D, et al. ; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group; National Cancer Institute of the United States Intergroup JBR.10 Trial Investigators . Vinorelbine plus cisplatin vs. observation in resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(25):2589-2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Douillard J-Y, Rosell R, De Lena M, et al. . Adjuvant vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus observation in patients with completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (Adjuvant Navelbine International Trialist Association [ANITA]): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(9):719-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pignon J-P, Tribodet H, Scagliotti GV, et al. ; LACE Collaborative Group . Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation: a pooled analysis by the LACE Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(21):3552-3559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arriagada R, Auperin A, Burdett S, et al. ; NSCLC Meta-analyses Collaborative Group . Adjuvant chemotherapy, with or without postoperative radiotherapy, in operable non-small-cell lung cancer: two meta-analyses of individual patient data. Lancet. 2010;375(9722):1267-1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brundage MD, Davies D, Mackillop WJ. Prognostic factors in non-small cell lung cancer: a decade of progress. Chest. 2002;122(3):1037-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varlotto JM, Recht A, Flickinger JC, Medford-Davis LN, Dyer AM, Decamp MM. Factors associated with local and distant recurrence and survival in patients with resected nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(5):1059-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu C-F, Fu J-Y, Yeh C-J, et al. . Recurrence risk factors analysis for stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(32):e1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howington JA, Blum MG, Chang AC, Balekian AA, Murthy SC. Treatment of stage I and II non-small cell lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5 suppl):e278S-e313S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramnath N, Dilling TJ, Harris LJ, et al. . Treatment of stage III non-small cell lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5 suppl):e314S-e340S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (Version 3.2016). 2015; https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines_nojava.asp. Accessed December 8, 2015.

- 15.Kozower BD, Sheng S, O’Brien SM, et al. . STS database risk models: predictors of mortality and major morbidity for lung cancer resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(3):875-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teh E, Abah U, Church D, et al. . What is the extent of the advantage of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical resection over thoracotomy in terms of delivery of adjuvant chemotherapy following non-small-cell lung cancer resection? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;19(4):656-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang G, Yang F, Li X, et al. . Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery is more favorable than thoracotomy for administration of adjuvant chemotherapy after lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9(1):170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nachiappan S, Askari A, Mamidanna R, et al. . The impact of adjuvant chemotherapy timing on overall survival following colorectal cancer resection. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(12):1636-1644. EJSO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun Z, Adam MA, Kim J, et al. . Determining the optimal timing for initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy after resection for stage II and III colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59(2):87-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Des Guetz G, Nicolas P, Perret G-Y, Morere J-F, Uzzan B. Does delaying adjuvant chemotherapy after curative surgery for colorectal cancer impair survival? a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(6):1049-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chavez-MacGregor M, Clarke CA, Lichtensztajn DY, Giordano SH. Delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy among patients with breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(3):322-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irie M, Nakanishi R, Yasuda M, Fujino Y, Hamada K, Hyodo M. Risk factors for short-term outcomes after thoracoscopic lobectomy for lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(2):495-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodrigues F, Grafino M, Faria I, Pontes da Mata J, Papoila AL, Félix F. Surgical risk evaluation of lung cancer in COPD patients—a cohort observational study [in Portuguese]. Rev Port Pneumol. 2006;22(5):266-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boffa DJ, Rosen JE, Mallin K, et al. . Perks and quirks to using the National Cancer Database for outcomes research: a review. JAMA Oncol. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strauss GM, Herndon JE II, Maddaus MA, et al. . Adjuvant paclitaxel plus carboplatin compared with observation in stage IB non-small-cell lung cancer: CALGB 9633 with the Cancer and Leukemia Group B, Radiation Therapy Oncology Group, and North Central Cancer Treatment Group Study Groups. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(31):5043-5051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson JR, Cain KC, Gelber RD. Analysis of survival by tumor response and other comparisons of time-to-event by outcome variables. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(24):3913-3915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American College of Surgeons The National Cancer Database 2013 PUF Data Dictionary. 2015; http://ncdbpuf.facs.org/node/259. Accessed December 1, 2015.

- 28.Wright CD, Gaissert HA, Grab JD, O’Brien SM, Peterson ED, Allen MS. Predictors of prolonged length of stay after lobectomy for lung cancer: a Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database risk-adjustment model. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85(6):1857-1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American College of Surgeons NCDB Getting Started—A Users Guide; National Cancer Database—Data Dictionary 2015; http://ncdbpuf.facs.org/content/ncdb?q=node/274. Accessed 12/10/2015, 2015.

- 30.Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med. 1989;8(5):551-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molinari N, Daurès J-P, Durand J-F. Regression splines for threshold selection in survival data analysis. Stat Med. 2001;20(2):237-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Desquilbet L, Mariotti F. Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Stat Med. 2010;29(9):1037-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haukoos JS, Lewis RJ. THe propensity score. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1637-1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parsons LS. Performing a 1:N Case-Control Match on Propensity Score. Presented at: Proceedings of the 29th Annual SAS Users Group International Conference; May 9-12, 2004; Montreal, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scagliotti GV, Fossati R, Torri V, et al. ; Adjuvant Lung Project Italy/European Organisation for Research Treatment of Cancer-Lung Cancer Cooperative Group Investigators . Randomized study of adjuvant chemotherapy for completely resected stage I, II, or IIIA non-small-cell Lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(19):1453-1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramsden K, Laskin J, Ho C. Adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage II non-small cell lung cancer: evaluating the impact of dose intensity and time to treatment. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2015;27(7):394-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shugarman LR, Mack K, Sorbero MES, et al. . Race and sex differences in the receipt of timely and appropriate lung cancer treatment. Med Care. 2009;47(7):774-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Booth CM, Shepherd FA, Peng Y, et al. . Time to adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in non-small cell lung cancer: a population-based study. Cancer. 2013;119(6):1243-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu Y, Zhai X, Chen S, Wang Z. Exploration of optimal time for initiating adjuvant chemotherapy after surgical resection: A retrospective study in Chinese patients with stage IIIA non-small cell lung cancer in a single center. Thorac Cancer. 2016;7(4):399-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Douillard J-Y, Tribodet H, Aubert D, et al. ; LACE Collaborative Group . Adjuvant cisplatin and vinorelbine for completely resected non-small cell lung cancer: subgroup analysis of the Lung Adjuvant Cisplatin Evaluation. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(2):220-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Patient Characteristics of the Propensity-Matched Pairs of Surgery Only and “Earlier” Adjuvant Chemotherapy Group.

eTable 2. Patient Characteristics of the Propensity-Matched Pairs of Surgery Only and “Reference Interval” Adjuvant Chemotherapy Group.

eTable 3. Patient Characteristics of the Propensity-Matched Pairs of Surgery Only and “Later” Adjuvant Chemotherapy Group.

eTable 4. Cox Proportional Hazards Model of Adjuvant Chemotherapy Patients “Landmarked” at 120 Days After Surgery.

eTable 5. Multivariate Logistic Regression Modeling of Predictors of “Later” (>56 Days) Initiation of Adjuvant Chemotherapy.