Abstract

Importance

Overdiagnosis of cancer—the identification of cancers that are unlikely to progress—is a source of discomfort and challenge for patients, physicians, and health care systems. A major cause of this discomfort is the inability to know prospectively with certainty which cancers are overdiagnosed. In thyroid cancer, as patients have begun to understand this concept, some individuals are independently deciding not to intervene, despite this practice not yet being widely accepted.

Objective

To describe the current experience of people who independently self-identify as having an overdiagnosed cancer and elect not to intervene.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this qualitative study, semistructured interviews were conducted between July 1 and December 31, 2015, with 22 community-dwelling adults aged 21 to 75 years who had an incidentally identified thyroid finding that was known or suspected to be malignant and who questioned the intervention recommended by their physicians. Verbatim transcripts were analyzed using constant comparative analysis.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The experience of individuals who self-identify as having an overdiagnosed cancer and elect not to intervene.

Results

Of the 22 people interviewed (16 females and 6 males; mean age, 48.5 years), 18 had elected not to intervene on their thyroid finding and had been living with the decision for a mean of 39 months (median, 40 months; range, 1-88 months). Twelve of the 18 participants reported that they experienced significant anxiety about cancer progression, but had considered reasons for choosing nonintervention: understanding issues of precision in diagnostic testing and the varied behavior of cancer, surgical risks, medication use, and low risk of death from the cancer. Twelve participants described their decisions as met with nonreassuring, unsupportive responses. Medical professionals, friends, and internet discussion groups told them they were “being stupid,” “were wrong,” or were “crazy” to not intervene. Although 14 individuals said they wished to connect with others about their experiences, only 3 reported success in doing so. Fifteen participants reported that they managed their overall experience through secret keeping. By the time of this study, 5 of the 18 individuals had discontinued surveillance, the recommended alternative to intervention. Despite this, only 7 participants “wished they did not know” about their thyroid finding.

Conclusions and Relevance

Isolation and anxiety characterize the current experience of patients with thyroid cancer who are living with the decision to not intervene. These patients are at risk of disengaging from health care. Successful de-escalation of intervention for patients who self-identify as having overdiagnosed cancers requires explicit social and health system support and education. We hypothesize that improved support would also promote quality of care by increasing the likelihood that patients could be kept engaged for recommended surveillance.

This qualitative study describes the experience of US patients who independently self-identify as having an overdiagnosed cancer and elect not to intervene.

Key Points

Question

What has been the experience of people who were among the first to question the practice of immediate intervention for their small, incidentally identified thyroid cancers?

Findings

In this qualitative study of 22 patients, participants reported receiving nonreassuring, unsupportive responses to their decision not to intervene; they experienced anxiety about disease progression, felt isolated, and most kept their diagnosis a secret because of their experiences. A substantial minority stopped monitoring their cancers as a result of their experiences.

Meaning

If efforts to de-escalate treatment for small asymptomatic thyroid cancers are to expand, explicit social and health system support and educational strategies will be needed.

Introduction

Overdiagnosis of cancer—the identification of cancers unlikely to progress—is an increasingly common source of discomfort and challenge for patients, physicians, and health care systems, mainly because overdiagnosis is an epidemiologic phenomenon, not a true diagnosis. It is not possible to know prospectively with certainty which incidentally detected cancers prone to this problem have been overdiagnosed. Overdiagnosis can occur in organized screening programs (such as has been documented with prostate cancer) but can also result when health care activities undertaken for other reasons uncover cancers for which the patient has no matching symptoms.

Overdiagnosis has now been recognized to occur in patients with thyroid cancer, which has large ramifications for population health. By the age of 50 years, half of the population has at least 1 thyroid nodule. By the age of 90 years, virtually all individuals have at least 1 thyroid nodule, making the population at risk of being identified with a thyroid nodule, and thus a cancer, very large. In Japan, it has been recognized that many small thyroid cancers can be effectively managed by a strategy of active surveillance. The most recent clinical practice guidelines from the United States acknowledge the Japanese data but still recommend surgical intervention for these cancers.

Although surveillance experiences for prostate cancer have been examined, these cancers are found and monitored in organized screening programs, which is arguably quite different from an individual self-labeling as overdiagnosed and choosing nonintervention outside a sanctioned monitoring program. We report on 18 people who self-identified as having overdiagnosed thyroid cancers and had been living this way for a mean of more than 3 years at the time of the study.

Methods

Inclusion Criteria

To be included, participants were required to have had an incidental thyroid finding (ie, not currently causing symptoms) that was suspicious for or known to contain cancer and to question the medical recommendation for an intervention on that finding because they thought their cancer or probable cancer was unlikely to progress. We defined suspicious for or known to contain cancer as a needle biopsy Bethesda Criteria cytologic reading of III-VI: atypical cells, follicular neoplasm, suspicious for malignancy, or malignant; a pathology report from a tissue specimen indicating thyroid cancer; or results from ultrasonography of a thyroid nodule described to the individual by his or her health care practitioner as likely to be a cancer. The definition we use here for suspicious for or known to contain cancer is broader than what a clinician might infer from the same information. We chose this approach because the lived experience of the study participants who had these various findings was indistinguishable.

The Dartmouth Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects reviewed and approved the study. Study candidates were directed to an Institutional Review Board–approved informational website (archived at http://www.louisedaviesmd.us) that served as an approved alternative to a signed consent form. Once participants completed that process, interviews were scheduled. At the beginning of each interview, the interviewer again reviewed the information website content and allowed the interviewees to ask any clarifying questions prior to beginning the interview.

The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research Publication Guidelines were used to guide the design and reporting of this work. Details of the study methods and the results of the member checking are in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

Recruitment

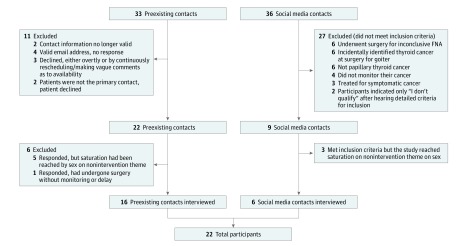

The principal investigator (L.D.) had been independently contacted by 33 people during a period of 5 years prior to the start of this study; these individuals were invited to participate in the study. Recruitment advertisements were also placed by Thyca: Thyroid Cancer Survivors’ Association Inc on their web site (http://www.Thyca.org). In addition, the study was publicized through Twitter and by word of mouth through professional networks to identify additional candidates. Efforts to work with other thyroid cancer survivor and activist groups were not successful. Details of study candidate identification are shown in Figure 1. Additional recruitment details are in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

Figure 1. Study Recruitment.

Preexisting contacts were people who had independently contacted one of us (L.D.). Social media contacts came from advertisements on the website of a thyroid cancer survivors’ group, Thyca (http://www.thyca.org).

Study Design

Twenty-two participants (and family members of 2 participants) completed 1 qualitative, semistructured interview each. Between July 1 and December 31, 2015, 2 of us (C.D.H. and G.S.H.) conducted interviews with participants via telephone, recording the audio and taking field notes. The mean duration of interviews was 57 minutes (median, 56 minutes; range, 36-83 minutes). The audio recordings were transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Data analysis was based on the constant comparative method. A codebook was developed and refined, then applied to all transcripts. Next, the team identified the major analytic categories and domains from the data itself, through data reduction. Following this, the data were interpreted to identify the major concepts and themes. Study participants were invited to review the findings and comment on their accuracy through “member checking” (confirming accuracy of the results with participants), conducted in a secure survey format.

Results

Sixteen women and six men participated, consistent with the epidemiologic presentation of thyroid cancer (3:1 ratio in age-adjusted incidence rate in 2013). The participants’ thyroid findings were all identified incidentally to other health care activities (Table).

Table. Demographics of Study Participants.

| Characteristic | Valuea |

|---|---|

| Total | 22 (100) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 6 (27) |

| Female | 16 (73) |

| Year of diagnosis | |

| 2008/2009 | 3 (14) |

| 2010/2011 | 6 (27) |

| 2012/2013 | 7 (32) |

| 2014/2015 | 6 (27) |

| Mode of identification of thyroid findingb | |

| Physician screening examination | 7 (32) |

| Radiologic incidental finding | 4 (18) |

| Diagnostic cascade | 10 (45) |

| Incidental to surgery | 1 (5) |

| Location of residence | |

| United States | |

| Northeast | 10 (45) |

| Southeast | 2 (9) |

| Central | 3 (14) |

| West | 4 (18) |

| Internationalc | 3 (14) |

| Highest educational leveld | |

| Some college | 3 (15) |

| College completed | 6 (30) |

| Master’s degree | 8 (40) |

| Doctorate | 3 (15) |

| Age at diagnosis, y | |

| Mean | 48.5 |

| Median (range) | 49.5 (20.0-73.0) |

| Size of thyroid finding according to the participant, cmd | |

| Mean | 1.3 |

| Median (range) | 1.2 (0.3-2.0) |

| No. of thyroid biopsies per participant | |

| Mean | 1 |

| Median (range) | 1 (1-3) |

| No. of physicians consulted about thyroid finding per participant | |

| Mean | 5 |

| Median (range) | 4.5 (2.0-10.0) |

Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

Physician screening is an examination of neck done as part of a general examination, where there are no symptoms that would otherwise require examination of the neck. Radiologic incidental finding is detection of a thyroid finding on a non–thyroid-directed imaging study. Diagnostic cascade occurs when a patient has new symptoms requiring workup, and a thyroid finding is uncovered, but it does not plausibly explain the patient’s symptoms. Incidental to surgery refers to incidental finding of thyroid cancer after surgery for nonthyroid cancer indications (eg, goiter, parathyroid adenoma, laryngeal cancer). Categories and their uses are adapted from Davies et al.

Australia, 1; Canada, 2.

n = 20.

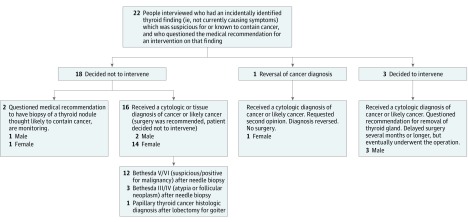

Range of Outcomes

All 22 study participants questioned the management of their thyroid finding recommended by their physicians, but the outcomes of this questioning process varied, likely reflecting the experience of the broader population. One person in the sample had the cancer diagnosis reversed on obtaining additional opinions, and 3 people ultimately elected to intervene. The remaining 18 participants decided to not intervene at various points in the workup process of their thyroid finding (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Identified Outcomes After Participants Questioned Intervention Recommendations for a Thyroid Finding.

The domains of experience identified among those who decided not to intervene, whether they had a biopsy or not, and whether their biopsy result was Bethesda III/IV or Bethesda V/VI were nearly identical; therefore, their findings are reported together as 1 group. Experiences of those who decided to have surgery or had a change in diagnosis were more heterogeneous.

The lived experience for participants whose thyroid finding was identified only on ultrasound (n = 2) compared with those who had a known or suspected cancer based on results of cytologic testing (n = 15) or identified after surgery (n = 1) was virtually indistinguishable. The effect on the participant of a suspicious ultrasonographic image was the same as for a cytologic or anatomical pathologic report labeling them as having a concerning finding or frank malignant neoplasm. Therefore, the experiences of all 18 participants were grouped together for analysis.

At the time of the study, these 18 participants had lived with their decision to not intervene for a mean of 39 months (median, 40 months; range, 1-88 months). Eleven participants were still under surveillance, 5 had stopped surveillance, 1 had not been able to find a physician willing to do surveillance, and 1 had undergone surgery after a period of surveillance because the thyroid cancer had grown.

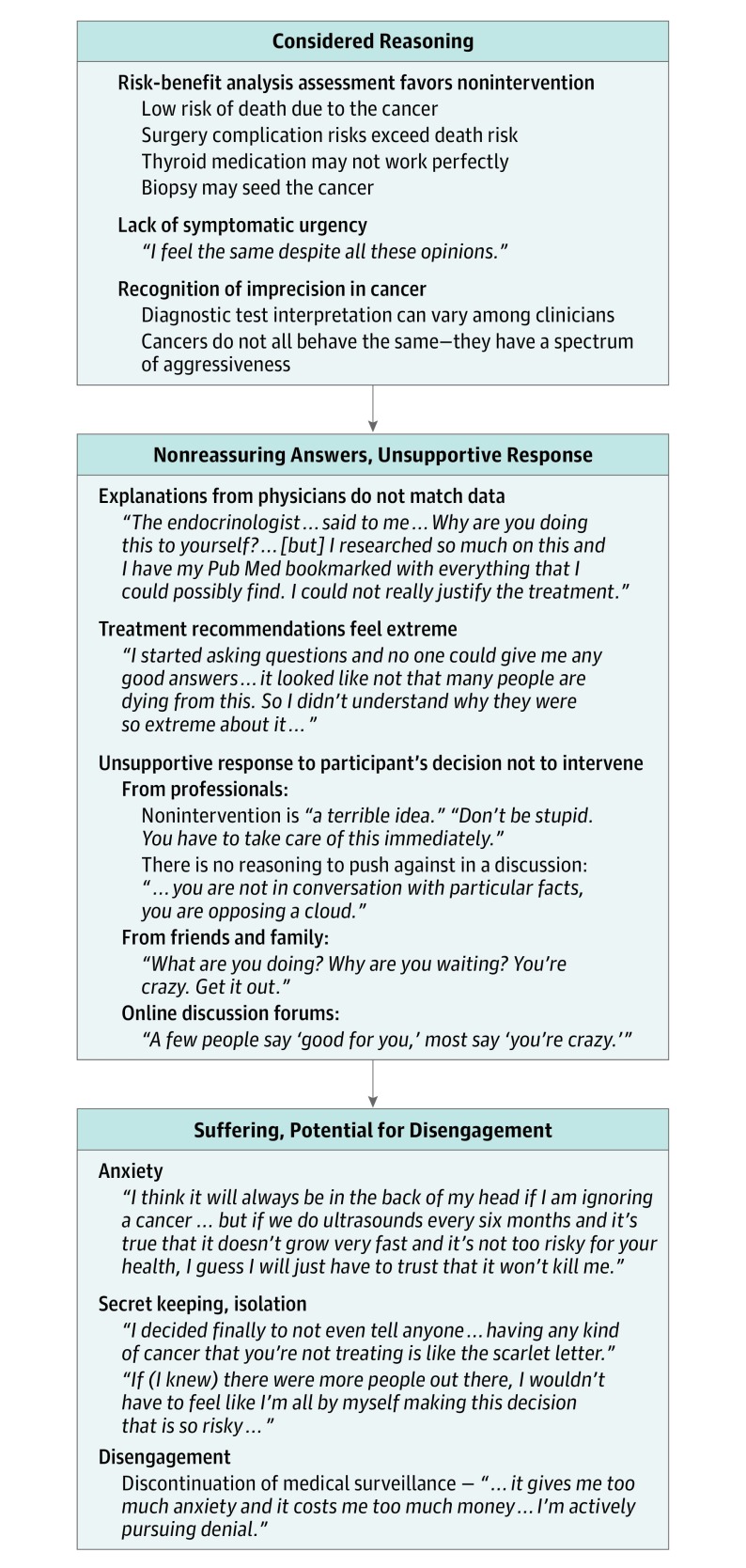

The Experiential Arc of Overdiagnosis

Figure 3 shows the major domains of experience for the 18 people who self-identified as overdiagnosed and elected to not intervene. Participants had sophisticated reasons for nonintervention, at times quoting medical literature and published risk probabilities. They typically focused on 1 or 2 concepts, but there was no single dominant pattern of reasoning. The participants’ proposal for nonintervention was met unfavorably. They did not receive reassuring responses to academic literature on surveillance of thyroid cancers they presented to clinicians or others. Twelve participants described instances of being told they were “stupid,” “wrong,” or “crazy” by medical professionals and others. Fifteen individuals described using a strategy of secret keeping to manage this response, because, as 1 person said, “untreated cancer is a scarlet letter,” referring to the book The Scarlet Letter, whose themes are public shaming and ostracism. Fourteen participants expressed a desire to hear about others’ experiences of nonintervention or to connect with others going through similar experiences. Only 3 individuals reported having found satisfying support.

Figure 3. Findings and Interpretation of the Overdiagnosis Experience Among Participants Who Self-identified as Having Overdiagnosed Cancers and Who Elected to Not Intervene.

Results are for the 18 people who had an incidental thyroid finding known or suspected to be thyroid cancer who elected to not intervene.

Anxiety about cancer progression was prominent in the descriptions of another 12 participants. Two of the 12 said they became more comfortable over time with their decision to not intervene. As a result of the participants’ overall experiences, by the time of this study, 5 of 18 had discontinued surveillance, the recommended alternative to intervention.

Reflections on the Experience of Having an Overdiagnosed Cancer

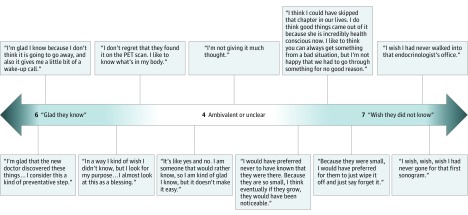

Despite the challenges described in choosing and living with nonintervention, not all participants wished they did not know about their thyroid finding. Six participants reported feeling glad that they knew about their thyroid finding when asked whether they preferred to know about their thyroid finding or to have never found out (Figure 4). Among the others for whom this question applied, 4 were ambivalent and 7 said that they wished they did not know.

Figure 4. Representative Reflections of Participants on the Experience of Choosing Nonintervention for Thyroid Finding.

Seventeen of 18 participants are included in the count. Excluded is the one person who underwent surgery for a change in the thyroid finding after a period of surveillance.

Discussion

Participants in this study self-identified as having overdiagnosed thyroid cancers and have been early adopters of nonintervention. They described a difficult course: their experience was characterized by a lack of acceptance by their social and health care systems, as well as anxiety about their cancer progression. Participants found it difficult to find publicly available information and wished to connect with others about their experience, but most could not find a community and were isolated. Most participants ended up keeping their decision a secret. A substantial minority disengaged from surveillance, the recommended alternative to intervention.

This is the first report to our knowledge that describes the patient experience among early adopters of nonintervention in overdiagnosed thyroid cancer. The experience we describe here is probably not unusual. Studies show low levels of physician awareness about overdiagnosis: only 28% of physicians in a recent study on prostate cancer screening listed overdiagnosis as a potential harm. Patients in another survey said their doctors mentioned overdiagnosis to them in the context of cancer screening less than 20% of the time. Half of these patients had at least a partial understanding of overdiagnosis, suggesting that patients may be ahead of physicians in their recognition of the concept.

A review of the history of the acceptability of active surveillance of prostate cancer shows clear parallels to what is currently happening with thyroid cancer. A potentially important difference is that, while overdiagnosis in prostate cancer came about as a result of organized, medically sanctioned screening programs, overdiagnosis of thyroid cancer has come about through incidental detection. This scenario could lead people to feel their cancer was more likely to need immediate treatment because it was found through serendipity, but the literature on prostate cancer suggests that this may not be the case. An article from 2002 in which men were interviewed about their prostate cancer treatment decisions, which historically parallels the time period we are in with thyroid cancer in terms of the data available to support surveillance, reported similar experiences. Patients independently found data that might support surveillance, but they experienced pressure to undergo treatment from family, friends, physicians, and even those in support groups. There was little acknowledgment or allowance for open discussion of this new approach, despite medical evidence supporting it. As a result, few pursued the option of surveillance. In another study, coping strategies for living with the uncertainty of cancer overdiagnosis described by the individuals in our data—changing health behaviors and trying to actively shift thinking—were noted to be actively used by those with prostate cancer as well. The similarity in experience and coping strategies implies that approaches suggested to help patients with prostate cancer manage life with surveillance instead of intervention may be helpful in thyroid cancer as well, such as providing psychosocial support for the anxiety and uncertainty, and interventions to increase empowerment and promote meaning in the experience.

The experience of our participants also has potential parallels to the Choosing Wisely campaign goal of limiting unnecessary interventions, which has not yet created as much change as hoped. McCaffery et al have pointed out that “suggesting a reduction in tests that are popular with the public can provoke emotionally charged, even hostile responses, reflecting cognitive dissonance,” which is exactly what our participants described. Unfortunately, medical training emphasizes action rather than inaction, with errors of omission generally treated more unfavorably than errors of commission. Our study focused on individuals, who face the challenge of living with their cancers, but overdiagnosis is also a challenge for clinicians, who must live with the uncertainty of potentially missing a case they might have been able to manage earlier. Changing behavior toward less intervention is likely to require more than education of patients or physicians alone; it will likely require a change in our larger social and medical culture. This is work worth undertaking since issues around what constitutes a cancer are only going to become more complex given that certain subtypes of papillary thyroid cancers will soon no longer be categorized as cancer.

Limitations

There are limitations to these findings. The small sample size means it is possible that some domains of experience were not identified, and the limited acceptance of nonintervention in thyroid cancer means that this population is necessarily unique. To ensure representativeness in the group, we sought a sample composition that included the key variables along which we hypothesized findings would be expected to vary, such as age, sex, and geographic location, and we continued to sample until we reached theoretical saturation on the domains of interest. Our participants did have high levels of educational attainment: more than half held a master’s degree or higher compared with 12% of the general population. This finding is likely because there is no societal framework yet for people who consider themselves to be overdiagnosed. Patients who place themselves in this category do not have access to available educational materials or broadly endorsed support groups. Thus, only those who are able to access the primary literature or detailed medical reporting—mostly individuals with higher levels of educational attainment—are able to create this framework for themselves. To ensure the reliability of our data interpretation, we used robust analytic methods, using a team approach for analysis with regular checks to ensure accuracy and completeness, and performed formal member checking with the research participants, who confirmed the accuracy of the interpretation in capturing their experiences.

Conclusions

For people who self-identify as having overdiagnosed cancers, nonintervention is currently a challenging path. The problems outlined here also provide insight into the difficulties facing those who would attempt to reduce overuse of medical care more broadly. Despite the challenge of living with nonintervention, not all participants wished they had not known about their thyroid finding. If the efforts to de-escalate treatment are to expand, explicit social and health system support and educational strategies will be needed.

eAppendix. Methods

References

- 1.Welch HG, Black WC. Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(9):605-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sandhu GS, Andriole GL. Overdiagnosis of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012(45):146-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies L, Ouellette M, Hunter M, Welch HG. The increasing incidence of small thyroid cancers: where are the cases coming from? Laryngoscope. 2010;120(12):2446-2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies L, Welch HG. Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States, 1973-2002. JAMA. 2006;295(18):2164-2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies L, Welch HG. Current thyroid cancer trends in the United States. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140(4):317-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, National Cancer Institute SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2002. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2002/. Accessed November 1, 2016.

- 7.Harach HR, Franssila KO, Wasenius VM. Occult papillary carcinoma of the thyroid: a “normal” finding in Finland: a systematic autopsy study. Cancer. 1985;56(3):531-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mortensen JD, Woolner LB, Bennett WA. Gross and microscopic findings in clinically normal thyroid glands. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1955;15(10):1270-1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyauchi A. Clinical trials of active surveillance of papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid. World J Surg. 2016;40(3):516-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugitani I, Fujimoto Y. Management of low-risk papillary thyroid carcinoma: unique conventional policy in Japan and our efforts to improve the level of evidence. Surg Today. 2010;40(3):199-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugitani I, Toda K, Yamada K, Yamamoto N, Ikenaga M, Fujimoto Y. Three distinctly different kinds of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma should be recognized: our treatment strategies and outcomes. World J Surg. 2010;34(6):1222-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN guidelines version 2: thyroid carcinoma. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/thyroid.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2016.

- 14.Oliffe JL, Davison BJ, Pickles T, Mróz L. The self-management of uncertainty among men undertaking active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(4):432-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, National Cancer Institute Cancer statistics. http://www.seer.cancer.gov. Accessed June 3, 2016.

- 19.Elstad EA, Sutkowi-Hemstreet A, Sheridan SL, et al. Clinicians’ perceptions of the benefits and harms of prostate and colorectal cancer screening. Med Decis Making. 2015;35(4):467-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moynihan R, Nickel B, Hersch J, et al. Public opinions about overdiagnosis: a national community survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moynihan R, Nickel B, Hersch J, et al. What do you think overdiagnosis means? a qualitative analysis of responses from a national community survey of Australians. BMJ Open. 2015;5(5):e007436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapple A, Ziebland S, Herxheimer A, McPherson A, Shepperd S, Miller R. Is “watchful waiting” a real choice for men with prostate cancer? a qualitative study. BJU Int. 2002;90(3):257-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pickles T, Ruether JD, Weir L, Carlson L, Jakulj F; SCRN Communication Team . Psychosocial barriers to active surveillance for the management of early prostate cancer and a strategy for increased acceptance. BJU Int. 2007;100(3):544-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, et al. Early trends among seven recommendations from the Choosing Wisely campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1913-1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCaffery KJ, Jansen J, Scherer LD, et al. Walking the tightrope: communicating overdiagnosis in modern healthcare. BMJ. 2016;352:i348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feinstein AR. The “chagrin factor” and qualitative decision analysis. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145(7):1257-1259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikiforov YE, Seethala RR, Tallini G, et al. Nomenclature revision for encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: a paradigm shift to reduce overtreatment of indolent tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(8):1023-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan CL, Bauman K. Educational Attainment in the United States: 2015. Washington, DC: US Dept of Commerce Census Bureau; March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnes JA, Davies L. Reading grade level and completeness of freely available materials on thyroid nodules: there is work to be done. Thyroid. 2015;25(2):147-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Methods