Abstract

This study examines the effectiveness of interactive telephone calls vs automated short message service on improving adherence to fecal immunochemical test screening compared with usual care.

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends annual fecal immunochemical test (FIT) as one of the colorectal cancer (CRC) screening tests.1 Adherence to yearly FIT is crucial to programmatic success.2 However, longitudinal adherence is low and strategies to improve persistent adherence are needed.3 We evaluated the effectiveness of interactive telephone calls vs automated short message service (SMS) on improving adherence to FIT screening compared with usual care.

Methods

We conducted a prospective randomized parallel group study, with the setting previously described.4 The trial was registered on Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02815436). Asymptomatic patients with negative FIT results in their first screening round from April to September 2015 due for annual screening in 2016 were eligible. Patients who could not understand telephone or SMS, or did not have mobile phones were excluded. Participants were randomized by a computer-generated sequence with an allocation ratio of 1:1:1. In the control group, participants were told in 2015 that they should visit the screening center for annual FIT pickup at the same calendar month of 2016. In the SMS group, subjects received a 1-way SMS, highlighting importance of CRC screening, and notifying date and location of FIT pickup on their mobile. In the telephone group, participants received a call from a trained health care physician with the same message as the SMS, but an interactive conversation was permitted. The interventions were delivered 1 month before the expected date of participant return for second round of screening. The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee approved the study and participant consent was waived because the interventions were an extension of the screening services. The trial protocol is provided in the Supplement.

Outcomes were rate of FIT pickup within 1 month of a patient’s anticipated return, and rate of FIT return within 2 months of anticipated return. Six hundred patients provide 80% power (at 5% α level) for detecting an 11% increase in FIT return rate in the intervention groups compared with control, which was assumed to have a FIT return rate of 70%.5 Associations between study groups and outcomes were examined by backward stepwise, binary logistic regression. Subgroup analysis for sex, marital status, household income, and educational level were performed, because these factors were previously found to be associated with screening adherence.6

Results

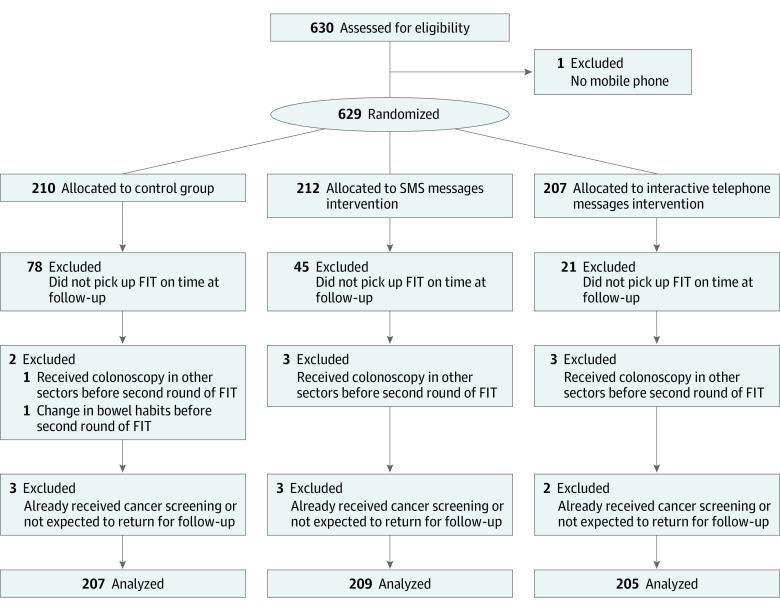

Of 621 patients, 207 were randomized to the control group, 209 to the SMS group, and 205 to the interactive telephone group (Figure). No statistically significant differences were noted among the groups for participant and clinical characteristics, including age, sex, and sociodemographic variables. The FIT pickup rate was 62.3%, 78.5%, and 89.8% for the control, SMS, and telephone groups, respectively (P < .001) (Table). Delayed pick up of FIT (ie, 1 month after the anticipated return date) occurred in 10.6%, 6.7%, and 3.4% of the corresponding groups, respectively (P = .02). The FIT return rate was 69.1%, 82.8% and 91.2%, for the respective groups (P < .001). The FIT pickup and return rates were significantly higher in the telephone group compared with the SMS group. Both interventions were more effective for FIT pickup and return than control, with similar unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios. The findings remained significant on subgroup analysis.

Figure. Consort Flow Diagram.

FIT indicates fecal immunochemical test.

Table. Effectiveness of Telephone and SMS Reminders on Rate of FIT Pickup and Return.

| Intervention Type | No. | FIT Pickup Rate | P Value | FIT Return Rate | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | ADa | AOR (95% CI) | % | ADa | AOR (95% CI) | ||||

| Usual care as reference | |||||||||

| Usual care | 207 | 62.3 | 1 [Reference] | 69.1 | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| SMS group | 209 | 78.5 | 16.2 | 2.35 (1.50-3.70) | <.001 | 82.8 | 13.7 | 2.39 (1.47-3.88) | <.001 |

| Telephone group | 205 | 89.8 | 27.5 | 6.14 (3.54-10.64) | <.001 | 91.2 | 22.1 | 5.23 (2.92-9.37) | <.001 |

| SMS group as reference | |||||||||

| SMS group | 209 | 78.5 | 1 [Reference] | 82.8 | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Telephone group | 205 | 89.8 | 11.3 | 2.39 (1.36-4.20) | .002 | 91.2 | 8.4 | 2.16 (1.18-3.95) | .01 |

Abbreviations: AD, absolute difference; AOR, adjusted odds ratios; CRC, colorectal cancer; FIT, fecal immunochemical test; SMS, short message service.

Absolute difference in proportions when compared with the reference group; adjusted odds ratios, covariates included age, sex, comorbidities, use of medications, educational level, monthly household income, job status, marital status, smoking, alcohol intake, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), waist circumference, family history of CRC in a first-degree relative.

Discussion

Nonadherence to longitudinal FIT screening contributes to CRC mortality.2 Telephone calls and SMS conferred a 5.2- and 2.4-fold higher likelihood of FIT return. Our findings should, however, be interpreted with caution because they could be sensitive to the timeframe when adherence was measured. These strategies acted on the predisposing and reinforcing factor components of the PRECEDE-PROCEED model. Telephone calls were superior to automated 1-way SMS, implying personal interaction with health care professionals enhances adherence. Screening programs in other settings with low adherence should consider telephone-based or SMS strategies to maximize the mortality benefits of screening. Since colonoscopy continues to be the gold-standard screening test in many developed countries and its adherence barriers may be different, the effectiveness of these strategies on enhancing colonoscopy attendance should be evaluated in future studies.

Trial Protocol

References

- 1.Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(23):2564-2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson LC, Tai E, Rim SH, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Vital signs: colorectal cancer screening, incidence, and mortality—United States, 2002-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(26):884-889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang PS, Wheat CL, Abhat A, et al. Adherence to competing strategies for colorectal cancer screening over 3 years. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(1):105-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong MC, Lam TY, Tsoi KK, et al. A validated tool to predict colorectal neoplasia and inform screening choice for asymptomatic subjects. Gut. 2014;63(7):1130-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong MC, Ching JY, Lam TY, et al. Prospective cohort study of compliance with faecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer screening in Hong Kong. Prev Med. 2013;57(3):227-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Power E, Miles A, von Wagner C, Robb K, Wardle J. Uptake of colorectal cancer screening: system, provider and individual factors and strategies to improve participation. Future Oncol. 2009;5(9):1371-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol