Key Points

Question

Is laryngopharyngeal reflux associated with nasal resistance, and does pharmacologic therapy improve subjective and objective nasal findings?

Findings

This case-control study of 100 adults (50 with laryngopharyngeal reflux, 50 controls) found that oral antireflux medication was associated with significant decreases in all parameters of the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation and Total Nasal Resistance values.

Meaning

Laryngopharyngeal reflux has a negative effect on nasal resistance and nasal congestion; treatment may improve subjective and objective nasal findings.

This case-control study describes the association of oral antireflux medication with laryngopharyngeal reflux and nasal resistance.

Abstract

Importance

Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is thought to be a potential exacerbating factor in upper airway diseases.

Objective

To describe the effect of pharmacologic therapy of laryngopharyngeal reflux on nasal resistance.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Prospective observational study performed between August 30, 2014, and October 1, 2015, at a tertiary care academic center including 50 patients with Reflux Symptom Index higher than 13 and Reflux Finding Score higher than 7 and 50 controls with no history of LPR and nasal disease.

Interventions

Oral antireflux medication was given to the LPR group for 12 weeks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The measurements of total nasal resistance (TNR) were performed by means of active anterior rhinomanometry technique and Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) was assessed.

Results

The LPR group had 29 (58%) women and a median age of 41.5 years (range, 18-64 years). The control group had 27 (54%) women and a median age of 38.5 years (range, 19-63 years). After treatment, a significant decrease was observed in all parameters. The median (range) TNR scores of the LPR group before and after treatment were 0.29 (0.12-0.36) and 0.19 (0.10-0.31), respectively. The median TNR score of the control group was 0.20 (range, 0.11-0.32). Whereas the TNR scores of the LPR group were higher than those of the control group before treatment (difference, −0.77; 95% CI, −0.10 to 0.05), they were almost the same after treatment (difference, 0.01; 95% CI, −0.01 to 0.03). The median (range) NOSE scores of the LPR group before and after treatment were 0.29 (0.12-0.36) and 0.19 (0.10-0.31), respectively. The median NOSE score of the control group was 0.20 (range, 0.11-0.32).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, laryngopharyngeal reflux had a negative effect on nasal resistance and nasal congestion. Treatment was associated with improved subjective and objective nasal findings.

Introduction

Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is an extraesophageal manifestation of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which was first described as ulcers and granulomas of the larynx by Cherry and Margulies in 1968. Studies carried out recently have demonstrated the reflux as a potential exacerbating factor in upper airway diseases. Although 2 theories have been proposed, it is still not known whether there is a relationship between reflux and nasal diseases. One of the theories is that acidic content reaching the upper airways triggers nasal congestion and inflammation. The second theory is about the esophageal-nasal reflex mechanism stimulated by vagal nerve response. This mechanism results in the congestion of nasal mucosa and a pathologic increase in nasal mucus secretion.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of LPR on the nasal airway and to determine the subsequent changes in symptoms and in nasal airway resistance after medical treatment.

Methods

We conducted a prospective observational clinical study. All investigations were performed in accordance with the guidelines regarding biomedical studies involving human subjects in the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before the study began. This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Turgut Ozal University School of Medicine.

Participants

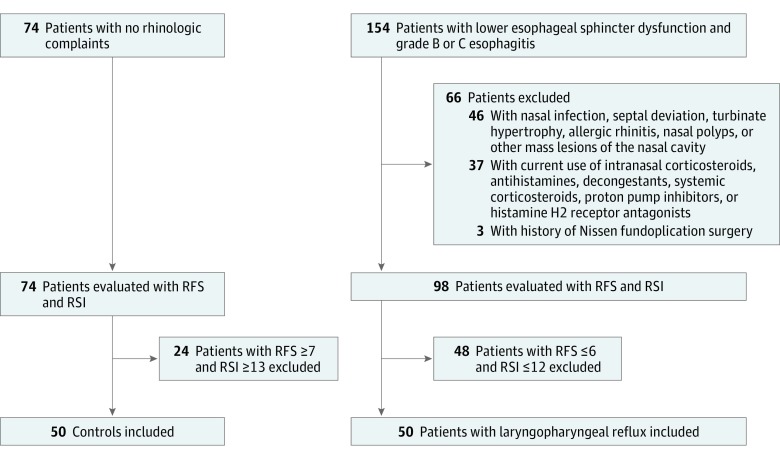

There were 2 groups in the study. In the study group, the patients had classic GERD symptoms such as heartburn and regurgitation. They underwent esophagogastroscopic examination by the same gastroenterologist. A total of 164 patients had lower esophageal sphincter dysfunction and grade B or C esophagitis according to the Los Angeles classification system. These 164 patients were directed to the otorhinolaryngology department, where they underwent a complete otorhinolaryngologic examination.

The following 3 exclusion criteria were then applied: (1) presence of acute or chronic nasal infection, septal deviation, turbinate hypertrophy, allergic rhinitis, nasal polyps, or other mass lesions of the nasal cavity, as determined by means of flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscopic examination; (2) current use of intranasal corticosteroid, antihistamine, decongestant and/or systemic corticosteroid, proton pump inhibitor, or histamine H2 receptor antagonists; and (3) history of Nissen fundoplication surgery.

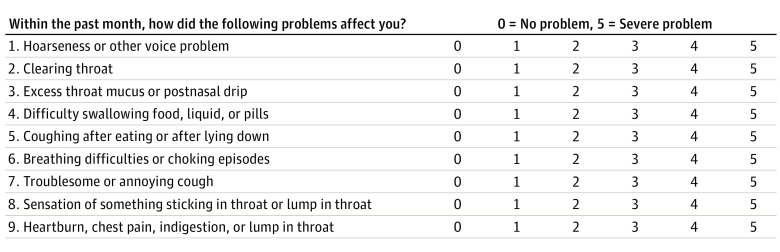

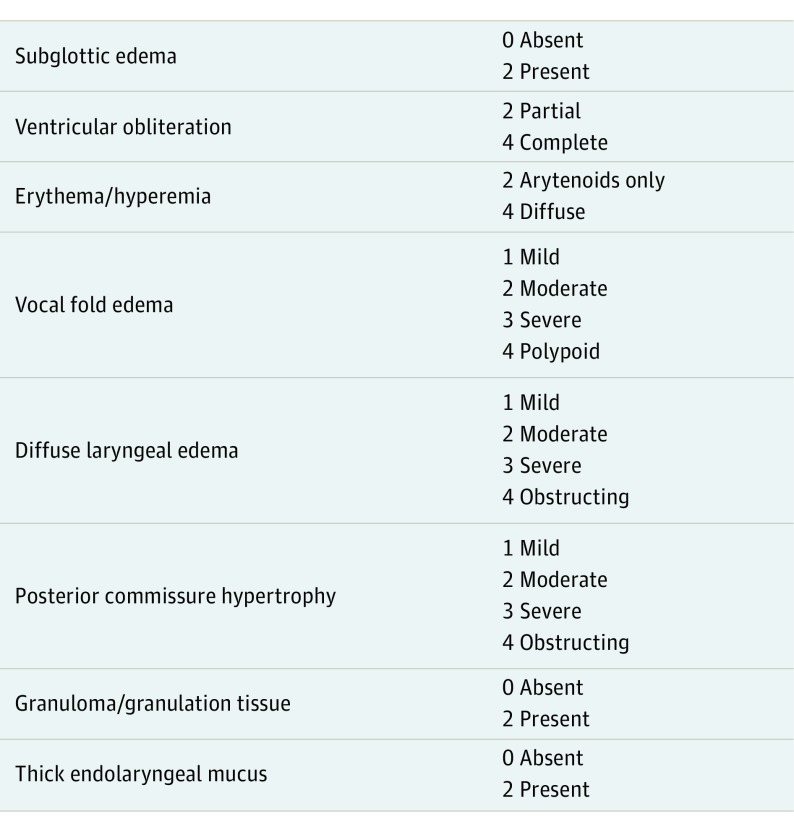

After the exclusion criteria were applied, the remaining 98 patients were examined by 2 otolaryngologists. The Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) (Figure 1) and Reflux Finding Score (RFS) (Figure 2) proposed by Belafsky et al were used to identify the diagnosis of LPR. The remaining 50 patients with RFS greater than 7 and RSI greater than 13 were enrolled in the study group. The control group consisted of patients who were seen in the otorhinolaryngology clinic without any complaint about LPR (RFS <7.0 and RSI <13.0), without any history of nasal disease, and who did not use intranasal corticosteroids, antihistamines, decongestants and/or systemic corticosteroids, or antihistamines currently. The control group underwent flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscopic examination, and patients with a diagnosis of acute or chronic nasal infection, septal deviation, turbinate hypertrophy, allergic rhinitis, nasal polyps, or other mass lesions of nasal cavity were excluded (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Reflux Symptom Index.

Figure 2. Reflux Finding Score.

Figure 3. Flow Diagram.

Study Design

All participants were asked to complete the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) Questionnaire, which has a 0 to 4 point scale (0, not a problem; 1, very mild problem; 2, moderate problem; 3, fairly bad problem; and 4, severe problem). The NOSE Questionnaire was used to evaluate the following symptoms: swelling or fullness in the nose, nasal congestion, difficulty in breathing through the nose; difficulty in sleeping; and inability to breathe comfortably through the nose during exercise or effort. All patients in the study and control groups were examined by rhinomanometry (NR6 instrument, G M Instruments Ltd) to measure total nasal resistance (TNR). The rhinomanometry was calibrated according to the international standard committee’s 2005 regulations. Rhinomanometric measurement was fulfilled in a standard, active, anterior procedure, and the data were presented as nasal inspiratory resistances indirectly measured from the flow at a reference pressure of 150 Pa. Patients were held in a seated position and asked to breathe through their noses with their mouths closed.

All the patients in the study group were advised on dietary modification and lifestyle changes to improve their conditions and prescribed oral antireflux proton pump inhibitor medication (pantoprazole, 40 mg) twice a day for 12 weeks.

All data about RSI, RFS, the NOSE Questionnaire, and TNR were collected before and after 12 weeks of proton pump inhibitor treatment.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package Program for the Social Sciences (version 15.0; SPSS Inc) software. Following the entry of patient data, all necessary diagnostic checks and corrections were performed. The conformity of the measured values with a normal distribution was examined graphically by the use of the Shapiro-Wilk test. Median (minimum-maximum) values were used for groups that were not distributed normally. The Wilcoxon test was used to evaluate the dependent groups whereas the Mann-Whitney test was used to evaluate the independent groups. Median differences were analyzed by the independent samples Hodges-Lehman median difference method with 95% confidence interval.

Results

A total of 100 adults participated in the study. The LPR group consisted of 50 patients, 29 women (58%) and 21 men (42%) with a median age of 41.5 years (range, 18-64 years). The control group consisted of 50 patients, 27 women (54%) and 23 men (46%) with a median age of 38.5 years (range, 19-63 years). There was no statistically significant difference between the age (difference, −2 years; 95% CI, −9 to 3 years) and sex distributions of the groups.

The RSI, RFS, and NOSE Questionnaire results before and after treatment are reported in the Table. The RSI (difference, −11.0; 95% CI, −12.0 to −10.0), RFS (difference, −3.5; 95% CI, −4.0 to −3.5), and NOSE Questionnaire results (difference, −3.0; 95% CI, −3.5 to −2.5) were significantly lower than pretreatment values (Table). Only 1 patient had a higher TNR value after treatment (before treatment, 0.12; after treatment, 0.13). The NOSE symptom score decreased in 47 patients, but 3 patients did not mention any change. A total of 43 patients (86%) had an RSI score less than 13 and 48 patients (96%) had an RFS score of less than 7.0 after treatment. The median TNR scores of the LPR group before treatment were significantly higher than those of the control group (difference, −0.77; 95% CI, −0.10 to −0.05), whereas there was no statistically significant difference between the median TNR scores of the LPR group after treatment and the control group (difference, 0.01; 95% CI, −0.01 to 0.03) (Table). The median NOSE scores of the LPR group before treatment were significantly higher than those of the control group (difference, −2.0; 95% CI, −3.0 to −1.0). The median NOSE scores of the LPR group were significantly higher before than after treatment (difference, −3.0; 95% CI, −3.5 to −2.5) (Table).

Table. Study Results Before and After Treatment in the Laryngopharyngeal Reflux (LPR) and Control Groups.

| Parameter | Median (Range) | Difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LPR Group | Control Group | ||

| Total Nasal Resistance Score, difference | |||

| Before treatment | 0.29 (0.12 to 0.36) | 0.20 (0.11 to 0.32) | −0.77 (−0.10 to 0.05) |

| After treatment | 0.19 (0.10 to 0.31) | NA | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) |

| Difference (95% CI) | −0.08 (−0.10 to −0.07) | ||

| Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation Score | |||

| Before treatment | 8 (1 to 10) | 6 (0 to 10) | −2 (−3 to −1) |

| After treatment | 4.5 (0 to 7) | NA | |

| Difference (95% CI) | −3.0 (−3.5 to −2.5) | ||

| Reflux symptom index | |||

| Before treatment | 19.5 (13 to 29) | 6 (0 to 10) | −14.0 (−16.0 to −13.0) |

| After treatment | 8 (4 to 18) | NA | |

| Difference (95% CI) | −11.0 (−12.0 to −10.0) | ||

| Reflux finding score | |||

| Before treatment | 8 (7 to 13) | 4 (0 to 5) | −4.0 (−5.0 to −3.0) |

| After treatment | 5 (2 to 7) | NA | |

| Difference (95% CI) | −3.5 (−4.0 to −3.5) | ||

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Discussion

Gastroesophageal reflux disease is considered to be an important cause of LPR that is associated with laryngeal inflammation. The most common symptoms of this condition presented in ear, nose, and throat clinics are hoarseness, throat pain, and sensation of a lump in the throat; however, numerous investigations have postulated that inflammation is not limited to the laryngeal mucosa. Moreover, some researchers have expressed that LPR was related to the pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis, middle ear effusion, postnasal drip, halitosis, and smelling and tasting problems. The aim of this study was to evaluate the nasal resistance and nasal symptoms in patients with LPR. To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the effect of LPR on nasal resistance.

In this study, we observed higher nasal resistance and NOSE scores in patients with LPR before treatment. Furthermore, Bozec et al also observed higher nasal resistance scores, increased visual analog scale scores of nasal obstruction, and posterior rhinorrhea in 20 patients with GERD. In our study, we used a larger sample size of 50 patients with LPR, and we used the NOSE questionnaire, which is a specific and reliable tool to evaluate nasal obstruction in adults.

Because we excluded the patients with nasal obstruction, the median NOSE score of the patients in the study group before treatment was slightly different from the control group, but we observed significant improvement in NOSE scores after treatment.

Most of the literature in this area has investigated the relationship between chronic rhinosinusitis and reflux; Holmes et al(pp1-54) proposed a connection between sinonasal disease and gastric hypersecretion. DiBaise et al observed abnormal pH meter results in 78% of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Additional evidence came from the 20-Item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-20), which was administered to 77 patients with proven GERD and controls. The authors reported that the mean SNOT-20 score was 22.1 in the study group and 9.4 in the control group.

Recent studies have assessed pharyngeal and nasopharyngeal pH monitoring and pepsin detection in mucosal secretions to show the direct exposure of acidic content above the laryngeal upper esophageal sphincter. In a study of 20 patients with chronic rhinosinusitis, 19 had a positive pharyngeal pH meter result, and 17 had positive nasopharyngeal pH meter results. Also, pepsin levels in nasal lavage fluid were positive in 5 patients. Similarly, DelGaudio observed more nasopharyngeal reflux episodes in patients with recurrent chronic rhinosinusitis after endoscopic sinus surgery. However, Wong et al claimed that standard pH meter probes lose contact with mucosa and cause artifacts that make previous study results controversial. They used a circumferential 4-channel pH probe that was less subject to artifact and demonstrated that direct reflux into the nasopharynx was a rare event. Wong et al performed an acid infusion challenge test on 10 healthy volunteers. They found no abnormal pH meter results in the nasopharynx by the use of a circumferential 4-channel pH probe, but there was a decrease in nasal peak flow, significantly greater concentration of fucose, and an increase in visual analog scale score. The authors proposed that higher acid concentrations in the lower esophagus trigger an esophageal-nasal reflex mechanism that causes a decrease in nasal airflow and mucociliary clearance rate. Although the methods used in the study of Wong et al were objective, the number of cases was limited. There are some other studies that support the vagal reflex mechanism theory. Lodi et al and Harding et al showed that patients with asthma and GERD had an increased vagal response compared with that of patients with asthma alone. Moreover, Delehaye et al found a statistically significant prolongation of the mucociliary transport time in 74% of patients with erosive esophagitis. Interestingly, the patients whose mucociliary transport time was not prolonged exhibited extraesophageal reflux. The authors concluded that the erosion in the distal esophagus triggered the vagal reflex mechanism.

Limitations

In our study, we observed higher nasal resistance in the LPR group. The patients included in the study had esophagitis, so vagal reflex activation may be the possible cause of the pathophysiologic mechanism as Delehaye et al reported. Because we did not measure pH in this study, we could not rule out direct acid exposure. Because of this limitation, we were not able to make an exact comment on pathophysiological processes. In our opinion, it could be possible that both direct acid exposure and vagal reflex activation were the exacerbating factors.

There are currently few reported studies seeking to clarify the effects of GERD and LPR on the upper respiratory tract. Therefore, additional clinical trials are needed to elucidate the pathophysiological processes that contribute to these respiratory changes.

Conclusions

Laryngopharyngeal reflux may play a role in the formation of nasal disease; however, there is no clear evidence to explain the mechanism of disease. In this study, we found that LPR had a negative effect on nasal resistance and nasal congestion. Laryngopharyngeal reflux treatment can improve subjective and objective nasal findings.

References

- 1.Cherry J, Margulies SI. Contact ulcer of the larynx. Laryngoscope. 1968;78(11):1937-1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lupa M, DelGaudio JM. Evidence-based practice: reflux in sinusitis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2012;45(5):983-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DelGaudio JM. Direct nasopharyngeal reflux of gastric acid is a contributing factor in refractory chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(6):946-957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford CN. Evaluation and management of laryngopharyngeal reflux. JAMA. 2005;294(12):1534-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong IW, Rees G, Greiff L, Myers JC, Jamieson GG, Wormald PJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and chronic sinusitis: in search of an esophageal-nasal reflex. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010;24(4):255-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstrong D, Bennett JR, Blum AL, et al. . The endoscopic assessment of esophagitis: a progress report on observer agreement. Gastroenterology. 1996;111(1):85-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom index (RSI). J Voice. 2002;16(2):274-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. The validity and reliability of the reflux finding score (RFS). Laryngoscope. 2001;111(8):1313-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stewart MG, Witsell DL, Smith TL, Weaver EM, Yueh B, Hannley MT. Development and validation of the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) scale. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(2):157-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clement PA, Gordts F; Standardisation Committee on Objective Assessment of the Nasal Airway, IRS, and ERS . Consensus report on acoustic rhinometry and rhinomanometry. Rhinology. 2005;43(3):169-179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Bortoli N, Nacci A, Savarino E, et al. . How many cases of laryngopharyngeal reflux suspected by laryngoscopy are gastroesophageal reflux disease-related? World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(32):4363-4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciorba A, Bianchini C, Zuolo M, Feo CV. Upper aerodigestive tract disorders and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. World J Clin Cases. 2015;3(2):102-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altundag A, Cayonu M, Salihoglu M, et al. . Laryngopharyngeal reflux has negative effects on taste and smell functions. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;155(1):117-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bozec A, Guevara N, Bailleux S, Converset S, Santini J, Castillo L. Evaluation of rhinologic manifestations of gastro-oesophageal reflux [in French]. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord). 2004;125(4):243-246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmes TH, Goodell H, Wolf S, et al. . The Nose: an Experimental Study of Reactions Within the Nose in Human Subjects During Various Life Experiences. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiBaise JK, Huerter JV, Quigley EM. Sinusitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(12):1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katle EJ, Hart H, Kjærgaard T, Kvaløy JT, Steinsvåg SK. Nose- and sinus-related quality of life and GERD. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269(1):121-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loehrl TA, Smith TL. Chronic sinusitis and gastroesophageal reflux: are they related? Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;12(1):18-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ocak E, Kubat G, Yorulmaz İ. Immunoserologic pepsin detection in the saliva as a non-invasive rapid diagnostic test for laryngopharyngeal reflux. Balkan Med J. 2015;32(1):46-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lodi U, Harding SM, Coghlan HC, Guzzo MR, Walker LH. Autonomic regulation in asthmatics with gastroesophageal reflux. Chest. 1997;111(1):65-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harding SM, Guxxo MR, Maples RV. Gastroesophageal reflux induced bronchoconstriction: vagolytic doses of atropine diminish airway responses to esophageal acid infusion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:A589. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delehaye E, Dore MP, Bozzo C, Mameli L, Delitala G, Meloni F. Correlation between nasal mucociliary clearance time and gastroesophageal reflux disease: our experience on 50 patients. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2009;36(2):157-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong IW, Rees G, Greiff L, Myers JC, Jamieson GG, Wormald PJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and chronic sinusitis: in search of an esophageal-nasal reflex. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010;24(4):255-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]