This study describes the symptoms, imaging characteristics, course, and treatment of otogenic septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint in children.

Key Points

Question

What are the clinical, bacteriological, and imaging characteristics of otogenic septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint in children?

Findings

This retrospective multicenter study of 9 pediatric cases of otogenic septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint found that the main clinical symptom for 5 patients (55%) was preauricular bulging, the most frequently isolated bacterial species was Fusobacterium necrophorum (found in 4 patients [44%]), and the condition evolved into temporomandibular joint ankylosis for 6 patients (67%).

Meaning

In cases of pediatric acute mastoiditis, septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint should always be sought to limit the incidence of temporomandibular joint ankylosis.

Abstract

Importance

Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint (SATMJ) is a very rare but potentially severe complication of pediatric middle ear infections because it presents risks of TMJ ankylosis.

Objective

To describe the clinical, radiological, biological, and microbiological characteristics and evolution of SATMJ complicating middle ear infections (otogenic SATMJ) in children.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This multicenter retrospective study included all children younger than 18 years referred between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2015, for otogenic SATMJ or for TMJ ankylosis that occurred a few months to a few years after an acute mastoiditis. Nine children were included in the study. Review of the children’s medical charts was conducted from February 1, 2016, to April 1, 2016.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Patients’ demographic characteristics and symptoms; radiological, biological, and bacteriological findings, including reanalysis of initial imaging; and treatment and outcome of SATMJ.

Results

Of the 9 children, 6 were boys and 3 were girls; the mean age was 2.1 years (range, 6 months to 4.7 years). In 7 cases (78%), the primary middle ear infection was acute mastoiditis. Clinically, 5 children (55%) had preauricular swelling and only 1 (11%) had trismus. Associated thrombophlebitis of the lateral sinus or intracranial collections was present in 7 cases (78%). An initial computed tomographic scan was performed for all but 1 patient, and second-line analysis detected clear signs of TMJ inflammation in all 8 children who had a computed tomographic scan. However, SATMJ was diagnosed in only 3 cases at the time of the initial middle ear infection, leading to the recommendation of TMJ physical therapy for several months. The most frequently involved bacteria was Fusobacterium necrophorum, which was found in 4 cases. Long-term ankylosis was identified in 6 cases (67%), and 5 of these children required surgical treatment.

Conclusions and Relevance

Clinicians and radiologists must thoroughly look for signs of SATMJ in children with acute mastoiditis to detect this complication, which can lead to disabling and hard-to-treat TMJ ankylosis.

Introduction

Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint (SATMJ) is a very rare complication of middle ear infection (MEI). To our knowledge, only 5 cases of pediatric SATMJ complicating MEI (otogenic SATMJ) have been published so far. Besides MEI, other causes of pediatric SATMJ have been reported in the literature, including blunt trauma, neonatal sepsis, systemic infectious disease, and juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

The aim of this study was to better describe the symptoms, imaging characteristics, natural course, and treatment of otogenic SATMJ in children.

Methods

Study Design

This retrospective study reviewed all pediatric otogenic SAMTJ cases referred to one of the 3 pediatric ear, nose, and throat departments of Trousseau, Necker, and Robert Debré Sick Children Hospitals in Paris, France, between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2015. This study was approved by the Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile-de France 2 ethical research committee. The committee waived the need for patient consent.

Review of Medical Records

The institutional database (Classification Commune des Actes Médicaux) was used to retrieve and review the medical records of children with otogenic SATMJ. The age, sex, medical history, symptoms, radiological findings, laboratory studies, treatments, outcomes, and additional complications for each child were noted. Initial imaging of the TMJ was systematically reanalyzed by one of us (S.B.).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients younger than 18 years who had otogenic MEI with SATMJ were included in the study. The diagnosis of acute otitis media (AOM) relied on the presence of an inflammation and/or bulging of the tympanic membrane. The diagnosis of acute mastoiditis (AM) was based on the association of postauricular subcutaneous edema or abscess with clinical AOM or middle ear opacity on computed tomographic (CT) imaging. The presence of fever, otalgia, purulent otorrhea, or visible defects of the mastoid cortex on CT scan was not necessary to diagnose AOM or AM.

The diagnosis of otogenic SATMJ was made in the presence of an MEI and of TMJ anomalies on CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): effusion in the TMJ, bony erosion of the mandibular condyle, obvious joint space widening, and abscess involving the TMJ. Clinically, SATMJ could be asymptomatic or revealed by trismus, preauricular pain, and/or bulging. In some cases, the diagnosis of SATMJ was made long after the initial MEI because of a long-term complication, such as TMJ ankylosis. Exclusion criteria were as follows: children older than 18 years, nonotogenic SATMJ, and absence of TMJ imaging.

Treatment Protocols

Acute otitis media was treated according to the French National Guidelines. Oral antibiotics were systematically prescribed for children younger than 2 years and for older children, but only in case of high fever, intense otalgia, or fever or pain that had persisted for 72 hours after initial symptoms.

All children with AM were hospitalized and given broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics consisting of third-generation cephalosporin along with clindamycin phosphate or metronidazole hydrochloride. Postauricular abscesses usually underwent needle aspiration under local anesthesia. Surgical drainage with mastoidectomy under general anesthesia was indicated in complicated cases (eg, lateral sinus thrombosis) or in the absence of a favorable response after 72 hours of intravenous antibiotics. There was no written protocol for the treatment of SATMJ.

Results

Nine children (6 boys and 3 girls) were included in the present study. The demographics, clinical anomalies, radiological findings, C-reactive protein levels, white blood cell counts, associated complications, treatments, and outcomes are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics.

| Patient No./ Sex/Age, y |

Medical History |

Primary Infection |

Associated Complications |

Preauricular Swelling |

Trismus | Detection or Presence of TMJ Radiological Anomalies During Initial MEIa |

Initial Treatmentb |

Isolated Bacteria |

CRP Level, mg/ L/WBC Count/μLc |

Evolution of TMJ Function |

Sequelae Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/M/4.7 | None | AM | LST, parapharyngeal abscess | No | No | Yes | ATBT, mastoidectomy, TMJPT | NA | 130/20 | Normal function | None |

| 2/M/3.6 | None | AOM | Meningitis, epidural empyema | No | No | No | ATBT, neurosurgical drainage | Fusobacterium necrophorum | 11/11 | Ankylosis 1 y after MEI | Physical therapy and surgery (twice) |

| 3/M/2.5 | None | AM | LST, pneumocephalus | Yes | No | No | ATBT, mastoidectomy | F necrophorum | 357/20 | Ankylosis 1 y after MEI | Physical therapy and surgery (twice) |

| 4/F/2.5 | None | AOM | None | Yes | No | No | ATBT, surgical drainage of preauricular abscess | NA | NA | Ankylosis 3 y after MEI | Physical therapy and surgery (twice) |

| 5/F/1.5 | None | AM | LST, epidural empyema | No | No | Yes | ATBT, mastoidectomy | F necrophorum | 161/30 | Normal function | None |

| 6/M/1.8 | Prematurity | AM | LST | Yes | No | No | ATBT, mastoidectomy | NA | 35/13 | Ankylosis 3 y after MEI | Physical therapy |

| 7/M/0.5 | None | AM | None | No | Yes | Yes | ATBT, mastoidectomy, TMJPT | Several species of streptococci in a bone sample | NA | Ankylosis 4 y after MEI | Physical therapy and surgery (twice) |

| 8/M/1 | None | AM | LST | Yes | No | No | ATBT, mastoidectomy | NA | 46/19 | Ankylosis 0.5 y after MEI | Physical therapy and surgery |

| 9/F/1.3 | None | AM | LST | Yes | No | Yes | ATBT, mastoidectomy, TMJPT | F necrophorum | 73/13 | Normal function | None |

Abbreviations: AM, acute mastoiditis; AOM, acute otitis media; ATBT, antibiotic treatment; CRP, C-reactive protein level; LST, lateral sinus thrombosis; MEI, middle ear infection; NA, not available; TMJ, temporomandibular joint; TMJPT, TMJ physical therapy; WBC, white blood cell.

SI conversion factors: To convert CRP to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 9.524; WBC count to ×109/L, multiply by 0.001.

Detection corresponds to the identification of septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint by the radiologist who performed the first interpretation of the initial imaging scan at the time of the episode of the middle ear infection. Presence corresponds to the finding of TMJ lesions during a second analysis of all the initial images performed by one of us (S.B.), a senior radiologist.

All patients received broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics.

Measured during the acute phase of the MEI and TMJ infection.

The patient’s mean age at the time of the initial MEI was 2.1 years (range, 6 months to 4.7 years). The primary infection was AM in 7 children (78%) and AOM in 2 (25%). Associated complications were frequent in 6 children (75%) (Table 1), and the most common of these complications was lateral sinus thrombosis (6 children [66%]). This complication was associated with epidural empyema in 2 cases, with pneumocephalus in 1 case, and with parapharyngeal abscess in 1 other case. Another child had meningitis and epidural empyema (Table 1).

Clinically, all 9 patients had fever, 5 (55%) had preauricular swelling, and 1 (11%) had trismus (Table 1).

Of the 9 patients, 8 (89%) received initial imaging at the time of the MEI: 7 had a CT scan, 1 (patient 1) had both a CT scan and an MRI, and 1 (patient 2) had no imaging (Table 1 and Figure 1A-C). For 4 patients (patients 1, 5, 7, and 9), the diagnosis of SATMJ was made at the time of the initial MEI episode. For 5 children (patients 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8), the radiological signs of SATMJ—clearly identified during a second review of the initial imaging by one of us (S.B.)—were missed by the radiologist who performed the first radiological interpretation. Symptoms suggestive of SATMJ (ie, trismus and preauricular bulging) were not statistically more frequent in children for whom otogenic SATMJ was diagnosed immediately (1 [25%] of trismus and 1 [25%] of preauricular bulging) as compared with those for whom SATMJ was diagnosed secondarily at the time of systematic review of all initial imaging data (0 of trismus and 4 [80%] of preauricular bulging).

Figure 1. Radiographic Imaging From 4 Patients.

A, Patient 5. Axial computed tomographic (CT) scan showing abscess of the left temporomandibular joint (TMJ) (circle) and lateral sinus thrombosis (arrowhead). B, Patient 4. Sagittal CT scan showing displacement of the condyle within the glenoid cavity (asterisk) and an effusion of the left TMJ (arrowheads). C, Patient 1. A T1-weighted, fat-saturated axial magnetic resonance image (MRI) showing an effusion of the right TMJ (arrowhead). D, Patient 3. Sagittal CT scan showing right TMJ ankylosis.

The mean C-reactive protein level was 123 mg/L (range, 11-357 mg/L) and the mean white blood cell count was 18.8/μL (range, 11-30/μL). (To convert C-reactive protein level to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 9.524; white blood cell count to ×109 per liter, multiply by 0.001.)

Bacteriological samples were obtained from 7 retroauricular abscesses, 1 intracranial collection (patient 2), 1 blood culture (patient 3), 1 preauricular abscess (patient 4), and 1 bone sample obtained during surgical treatment of a TMJ ankylosis performed 10 years after the initial MEI. Fusobacterium necrophorum was isolated in 4 patients (Table 1). The bone sample contained several types of streptococci.

Seven patients with AM (78%) underwent mastoidectomy as the initial treatment for the MEI (Table 1). Patient 4 underwent concomitant drainage of a preauricular abscess. All 3 patients diagnosed with SATMJ during the initial MEI underwent physical therapy (ie, jaw opening exercises) over the course of several months, but none underwent aspiration or incision and drainage of the TMJ (Table 1).

Temporomandibular joint ankylosis was observed in 6 patients (67%) (Figure 1D). This complication was diagnosed between 1 and 3 years after the initial MEI (mean value, 2 years). One case (patient 7) occurred despite an SATMJ diagnosis during the initial episode of MEI, leading to early treatment with TMJ physical therapy (Table 1). All 6 patients with TMJ ankylosis had trismus, and half of them reported feeding or speaking difficulties. The treatment of TMJ ankylosis consisted of surgery in 5 cases (83%). Temporomandibular joint was exposed through a pretragal approach, and local osteotomies or ostectomies were performed. In patient 8, a cartilaginous rib graft was fixed to the mandibular ramus with the upper portion placed within the glenoid fossa. Four children needed 2 surgical procedures. These treatments resulted in a partial improvement of the jaw opening in 5 cases. The sixth patient was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Because of its rarity, otogenic SATMJ remains a poorly recognized complication of pediatric MEI. The aim of this present study was to describe its clinical, radiological, biological, and microbiological characteristics and evolution.

Pathophysiologic Features

Middle ear infection might reach the TMJ through direct or hematogenous pathways. Direct extension is favored by the thinness of the bony plate that separates the middle ear from the glenoid fossa. In young children, the separation between the middle ear and the TMJ could be particularly permeable because of yet unachieved local ossification processes in children. This fact probably explains why our patients are young (mean age, 2.4 years; range, 6 months to 4 years) (Table 1) and why only 1 case of otogenic SATMJ has been reported in adults.

Clinical Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis of otogenic SATMJ is difficult because of the frequent absence of trismus, which was true in 7 of our patients (78%) and in 2 (40%) of the 5 previously published cases. This symptom might be underestimated because it is not routinely sought by physicians during their clinical evaluation of children with MEI. Preauricular swelling is much more frequent than trismus; it was absent in only 4 of our patients (44%) and in only 1 of the 5 other published cases (20%). Such a swelling is not a pathognomonic sign of SATMJ given that it can also be observed in AM with preauricular subcutaneous extension of the infection through zygomatic air cells.

Imaging

Despite the growing concerns about the long-term effects of CT scan radiation exposure in children, CT with contrast enhancement remains the first-line imaging method in the presence of AM or SATMJ for the following reasons: compared with MRI, CT is more readily obtained and easier to perform in children; it also delineates both the bone and the soft tissues, enabling the detection of areas of bone destruction or demineralization as well as soft-tissue edema or abscesses, intracranial collections, and lateral sinus thrombophlebitis. In addition to checking this list of classic findings, the radiologist should systematically and thoroughly explore the TMJ area because SATMJ can occur without any overt physical signs such as preauricular bulging or trismus (Table 1). There may be mild radiological abnormalities, such as displacement of the mandibular condyle within the glenoid cavity, hypodensity, or contrast enhancement in or around the TMJ (Figure 1A-C). Bony changes are rare at the beginning of the process. Magnetic resonance imaging is not routinely obtained in the presence of AM. However, when AM is associated with trismus or preauricular bulging and when the CT scan does not show any clear anomaly of the TMJ, MRI is probably useful to improve the identification of SATMJ (Figure 1C). Alternatively, TMJ ultrasonography can be used in this context. When ankylosis is suspected, a CT scan easily demonstrates bony ankylosis (Figure 1D).

Microbiology

Four of the 5 previously reported cases (80%) of pediatric otogenic SATMJ were the result of group A Streptococcus (Table 2). In contrast to these findings, 4 (80%) of our positive bacteriological samples retrieved F necrophorum and isolated no group A Streptococcus. This discrepancy might result from 2 differences between our patients and other published cases:

Table 2. Previously Published Cases of Pediatric Otogenic SATMJa.

| Source | Age | MEI | TMJ Revealing Symptom | Imaging | Initial Treatmentb | Involved Bacteria | Sequelae and Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faerber et al, 1990 | 15 mo | AM | Preauricular tumefaction | CT scan: no arthritis | Mastoidectomy | Staphyloccocus epidermidis (myringotomy and mastoidectomy) | Ankylosis 30 mo after initial MEI; Initial TMJPT; TMJ surgery at age 6 y; additional TMJ surgery for ankylosis recurrence 8 mo later; good outcome |

| Hadlock et al, 2001 | 11 y | AM | Trismus, preauricular tumefaction | CT scan: arthritis | Mastoidectomy; TMJ puncture: purulent fluid | Group A Streptococcus (mastoidectomy) | None |

| Gayle et al, 2013 | 6 y | AOM | Trismus | CT scan: arthritis | TMJ puncture: purulent fluid | Group A Streptococcus (blood and joint culture) | None |

| Hammoudi et al, 2009 | 7 mo | AOM | Preauricular tumefaction | CT scan: arthritis | Myringotomy; TMJ puncture: no pus; TMJPT | Group A Streptococcus (myringotomy and blood culture) | None |

| Bast et al, 2015 | 7 y | AOM | Trismus, preauricular tumefaction | MRI: arthritis | TMJ puncture and washout: purulent fluid | Group A Streptococcus (TMJ sample, PCR) | None |

Abbreviations: AM, acute mastoiditis; AOM, acute otitis media; CT, computed tomographic; MEI, middle ear infection; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SATMJ, septic arthritis of the TMJ; TMJ, temporomandibular joint; TMJPT, TMJ physical therapy.

Otogenic SATMJ is pediatric MEI complicating SATMJ.

All patients also received broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic therapy.

Seven of our patients (78%) initially had mastoiditis, whereas 3 (60%) of previously published cases resulted from an episode of AOM. Interestingly, F necrophorum is rarely involved in AOM but represents about 7% of bacteria isolated in pediatric AM.

Six of our patients (75%) developed TMJ ankylosis, whereas only 1 (20%) of the previously published cases had such a complication. Thus, our study population might represent a subgroup of SATMJ with specific bacterial flora associated with higher risks of functional sequelae. Fusobacterium necrophorum is an aggressive bacterium leading to long-lasting and complicated cases of AM with frequent skull base osteitis and septic thrombophlebitis.

In 1 of our patients, several streptococci were isolated in a bone sample performed during the surgical treatment of TMJ ankylosis several years after the initial MEI episode. This underlines the possibility of long-lasting bacterial TMJ osteitis after SATMJ, eventually leading to late-onset TMJ ankylosis.

Initial Treatment and Outcome

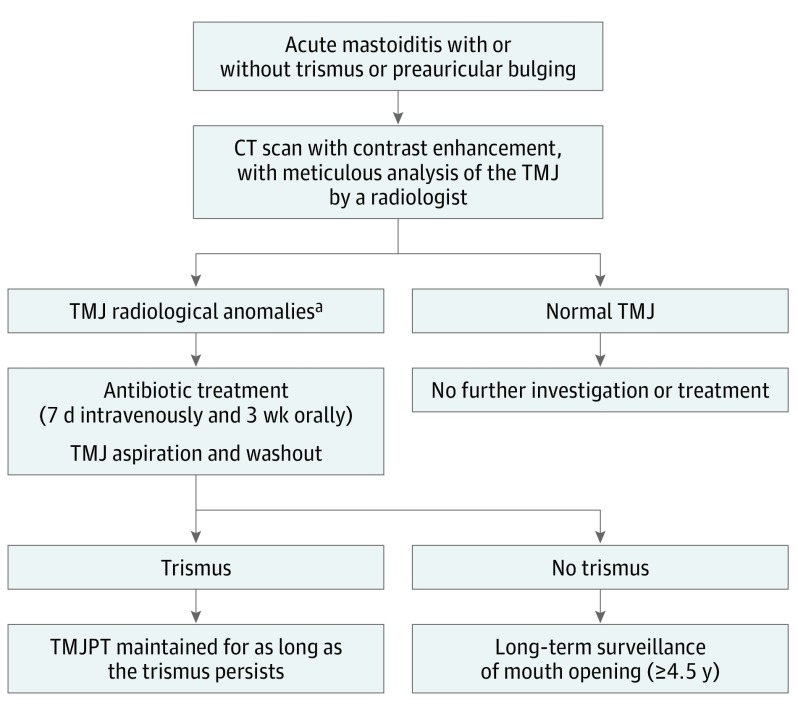

Of the 7 cases (3 from the present study and 4 from the literature) in which SATMJ was diagnosed at the time of the initial MEI episode, 4 were treated with TMJ physical therapy and 4 with TMJ aspiration (Tables 1 and 2). Only 1 case (patient 7) eventually evolved to TMJ ankylosis. These numbers are too small to assess the efficacy of TMJ physical therapy and TMJ aspiration and thus wash out in the prevention of ankylosis. However, based on this study’s findings, our new protocol for the treatment of otogenic SATMJ encompasses 7 days of intravenous followed by 3 weeks of oral antibiotic treatment, TMJ aspiration, and washout (Figure 2). In the presence of trismus, TMJ physical therapy with lateral excursive and protrusive movements is maintained for as long as the trismus persists. In the absence of trismus, a clinical surveillance of mouth opening is scheduled once every 3 weeks for 6 months, then once every 6 months for 1 year, and finally once a year for 3 years. This long-term surveillance is justified by the fact that TMJ ankylosis can occur up to 4 years after the initial MEI. In addition, a final visit is scheduled at ages 12 to 13 years to detect SATMJ-induced unilateral mandibular hypoplasia.

Figure 2. Working Algorithm: Diagnosis and Treatment of Otogenic Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint (SATMJ).

Otogenic septic arthritis is also known as middle ear effusion infection complicating SATMJ. CT indicates computed tomographic; TMJ, temporomandibular joint; and TMJPT, TMJ physical therapy.

aTemporomandibular joint radiological anomalies are effusion in the TMJ, bony erosion of the mandibular condyle, obvious joint space widening, and abscess involving the TMJ.

To manage TMJ ankylosis, all but 1 of the 7 children (6 from the present study and 1 from the literature) required invasive TMJ surgery, and 5 children had to have an operation several times. The final functional outcome was satisfying in all cases.

Conclusions

Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint is a very rare but potentially severe complication of acute MEI in children. Trismus is often initially absent, and this diagnosis should be particularly suspected in case of preauricular swelling. Because of the possibility of asymptomatic cases, the TMJ should be systematically and accurately analyzed on CT scans performed on children with AM. Further prospective studies that include larger cohorts will be necessary to determine the incidence and the optimal treatment of otogenic SATMJ.

References

- 1.Murphy JB. Arthroplasty for intra-articular bony and fibrous ankylosis of temporomandibular articulation: report of nine cases. JAMA. 1914;42(23):1783-1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.1914.02560480017006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hadlock TA, Ferraro NF, Rahbar R. Acute mastoiditis with temporomandibular joint effusion. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125(1):111-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammoudi K, Manceau A, Cazeneuve N, Poulain D, Buis J, Soin C. Childhood septic temporomandibular arthritis [in French]. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2009;126(1):18-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gayle EA, Young SM, McKenna SJ, McNaughton CD. Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint: case reports and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(5):674-678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bast F, Collier S, Chadha P, Collier J. Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint as a complication of acute otitis media in a child: a rare case and the importance of real-time PCR for diagnosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79(11):1942-1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leighty SM, Spach DH, Myall RW, Burns JL. Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint: review of the literature and report of two cases in children. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;22(5):292-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Regev E, Koplewitz BZ, Nitzan DW, Bar-Ziv J. Ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint as a sequela of septic arthritis and neonatal sepsis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(1):99-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasznia-Kocot J, Cichos B, Sada-Cieślar M, Buszman Z. [Staphylococcal septicemia in a newborn infant with multiple organ involvement] [in Polish]. Wiad Lek. 1990;43(7):301-304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaves Netto HD, Nascimento FF, Chaves Md, Chaves LM, Negreiros Lyrio MC, Mazzonetto R. TMJ ankylosis after neonatal septic arthritis: literature review and two case reports. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;15(2):113-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parmar J. Case report: septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint in a neonate. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46(6):505-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Axhausen G. Arthritis deformans of the temporomandibular joint [in German]. Dtsch Zahnarztl Z. 1954;9(15):852-859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chuk R, Arvier J, Laing B, Coman D. Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint in an infant. Clin Pract. 2015;5(2):736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Twilt M, Arends LR, Cate RT, van Suijlekom-Smit LWA. Incidence of temporomandibular involvement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2007;36(3):184-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, et al. ; International League of Associations for Rheumatology . International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):390-392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morales H, Cornelius R. Imaging approach to temporomandibular joint disorders. Clin Neuroradiol. 2016;26(1):5-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Société de Pathologie Infectieuse de Langue Française Recommandation de bonne pratique: antibiothérapie par voie générale en pratique courante dans les infections respiratoires hautes de l’adulte et de l’enfant. http://www.infectiologie.com/UserFiles/File/medias/Recos/2011-infections-respir-hautes-recommandations.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed February 7, 2017.

- 17.Quesnel S, Nguyen M, Pierrot S, Contencin P, Manach Y, Couloigner V. Acute mastoiditis in children: a retrospective study of 188 patients. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(12):1388-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keith DA. Development of the human temporomandibular joint. Br J Oral Surg. 1982;20(3):217-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright DM, Moffett BC Jr. The postnatal development of the human temporomandibular joint. Am J Anat. 1974;141(2):235-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai X-Y, Yang C, Zhang Z-Y, Qiu W-L, Chen M-J, Zhang S-Y. Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint: a retrospective review of 40 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(4):731-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faerber TH, Ennis RL, Allen GA. Temporomandibular joint ankylosis following mastoiditis: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48(8):866-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(22):2277-2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bounds GA, Hopkins R, Sugar A. Septic arthritis of the temporo-mandibular joint—a problematic diagnosis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;25(1):61-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trimble LD, Schoenaers JA, Stoelinga PJ. Acute suppurative arthritis of the temporomandibular joint in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Maxillofac Surg. 1983;11(2):92-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manfredini D, Guarda-Nardini L. Ultrasonography of the temporomandibular joint: a literature review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38(12):1229-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Monnier A, Jamet A, Carbonnelle E, et al. Fusobacterium necrophorum middle ear infections in children and related complications: report of 25 cases and literature review. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(7):613-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]