Key Points

Question

How is physician-aided dying being used in Oregon?

Findings

In this analysis of publicly available data, about two-thirds of patients prescribed lethal medication under Oregon’s Death with Dignity act consumed the medication and subsequently died. Cancer was the most common underlying disease.

Meaning

Physician aid-in-dying makes up only a small fraction of Oregon resident deaths, accounting for 38.6 deaths per 10 000 total deaths, but it offers considerable potential benefits to many patients who are near the end of their life.

This study examines trends in patient utilization of physician-aided dying under the Death With Dignity Act in Oregon between 1998 and 2015.

Abstract

Importance

Numerous states have pending physician-aided dying (PAD) legislation. Little research has been done regarding use of PAD, or ways to improve the process and/or results.

Objectives

To evaluate results of Oregon PAD, the longest running US program; to disseminate results; and to determine promising PAD research areas.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective observational cohort study of 991 Oregon residents who had prescriptions written as part of the state’s Death with Dignity Act. We reviewed publicly available data from Oregon Health Authority reports from 1998 to 2015, and made a supplemental information request to the Oregon Health Authority.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Number of deaths from self-administration of lethal medication versus number of prescriptions written.

Results

A total of 1545 prescriptions were written, and 991 patients died by using legally prescribed lethal medication. Of the 991 patients, 509 (51.4%) were men and 482 (48.6%) were women. The median age was 71 years (range, 25-102 years). The number of prescriptions written increased annually (from 24 in 1998 to 218 in 2015), and the percentage of prescription recipients dying by this method per year averaged 64%. Of the 991 patients using lethal self-medication, 762 (77%) recipients had cancer, 79 (8%) had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, 44 (4.5%) had lung disease, 26 (2.6%) had heart disease, and 9 (0.9%) had HIV. Of 991 patients, 52 (5.3%) were sent for psychiatric evaluation to assess competence. Most (953; 96.6%) patients were white and 865 (90.5%) were in hospice care. Most (118, 92.2%) patients had insurance and 708 (71.9%) had at least some college education. Most (94%) died at home. The estimated median time between medication intake and coma was 5 minutes (range, 1-38 minutes); to death it was 25 minutes (range, 1-6240 minutes). Thirty-three (3.3%) patients had known complications. The most common reasons cited for desiring PAD were activities of daily living were not enjoyable (89.7%) and losses of autonomy (91.6%) and dignity (78.7%); inadequate pain control contributed in 25.2% of cases.

Conclusions and Relevance

The number of PAD prescriptions written in Oregon has increased annually since legislation enactment. Patients use PAD for reasons related to quality of life, autonomy, and dignity, and rarely for uncontrolled pain. Many questions remain regarding usage and results, making this area suitable for cancer care delivery research.

Introduction

Physician aid-in-dying (PAD) refers to a physician providing a terminally ill patient with a prescription for a lethal dose of medication that the patient intends to use to end his or her own life.1 Oregon put forth the Death with Dignity Act (DWDA) in 1994, and it became law in 1997. Oregon was the first state to enact such legislation.

The act has requirements protecting prescribers and users from civil and criminal liability. All PAD candidates must (1) be Oregon residents (duration unspecified), (2) be certified by 2 physicians to have a life expectancy of less than 6 months, (3) have drugs prescribed by an MD or DO licensed in Oregon, (4) be capable of making and communicating health care decisions for themselves, and (5) be able to self-administer the medication.2 The patient must make 2 oral requests and 1 written request for PAD, over a minimum period of 15 days. Alternatives, including comfort care, hospice, and pain control are offered. Patients are told at several points that they may rescind the request.

The Oregon Health Authority (OHA) is legally obligated to collect compliance and prescribing information, and it produces an annual report that includes basic demographic information, the number of prescriptions written, and the number of patients taking the lethal medication.3 Requests for additional data may be made. Patient confidentiality is guaranteed, and the OHA will not disclose whether an individual physician participates.

We examined DWDA data to determine usage and effectiveness, and to gauge promising cancer care delivery research areas.

Methods

We reviewed OHA website reports from 1998 to 2015.3 We also made a supplemental data request to the state concerning the numbers of physicians participating and prescriptions written per physician. Summary data, including user demographics, medication efficacy and toxic effects, and underlying reasons for patients requesting and using PAD, were gathered. These data, including patient ethnicity and time to coma and death, were assessed by the prescribing physician.

We compared trends in death rates vs prescriptions written using logistic regression.4 These were also evaluated using Poisson regression, adjusting for temporal changes in the Oregon population.5

The Oregon Health and Science University Office of Integrity deemed the study IRB-exempt because the study used publicly available data recorded in such a manner that participants could not be identified.

Results

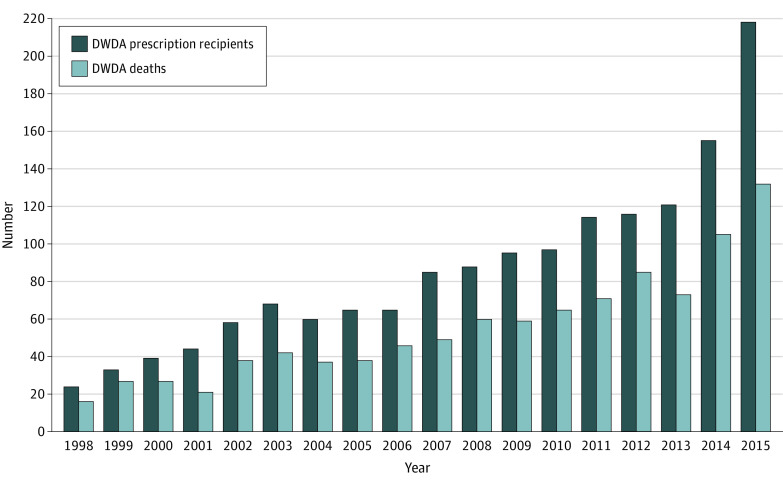

A total of 1545 prescriptions were written, and 991 (64%) patients ingested the medications and subsequently died. DWDA deaths make up only a small fraction of overall Oregon resident mortality, with a rate of 38.6 per 10 000 total deaths.3 From 1998 to 2013, the number of prescriptions written had an annual average increase of 12.1% (from 24 to 121 over the entire period), and during 2014 and 2015 it increased by 28% to 41% (121 in 2014 and 218 in 2015). The ratio of prescriptions written per year, to the number of patients dying from self-administration, ranged from 0.48 to 0.82 (median, 0.64), with no significant trend observed over time (Figure). Three-hundred thirty-six physicians wrote DWDA prescriptions, averaging 3.4 total prescriptions each (range, 1-71).

Figure. Number of Prescriptions and Physician-Assisted Deaths by Yeara.

aFigure reproduced from the Oregon Health Authority, Oregon Public Health Division.3

Of 991 patients, 52 (5.3%) were referred to psychiatrists for determination of competence. Forty-six (4.7%) were in long-term care facilities when they self-administered, and 1 individual was a hospital inpatient. Physicians were present at the time of ingestion in 148 cases (16.1%). Between 2001 and 2015, 855 (93.5%) patients notified families of their intention to use DWDA medication, and 928 (94.0%) took the medicine at home.

Pure pentobarbital was a commonly used lethal drug until it became unavailable in 2012.6 Secobarbital use accounted for 580 (58.5%) deaths.

Information on drug effectiveness and complications was requested on all patients from 1998 to 2010; after that only in cases when a health care provider was present at the time of death. The median time to coma was 5 minutes (range, 1-38 minutes). Patients rarely remained unconscious for long periods; median time to death was 25 minutes, but the range was 1 minute to more than 4 days. The medications were relatively devoid of unexpected toxic effects. Vomiting was unusual (24 patients, 2.4%). Six patients awakened, giving the medications an efficacy rate of 99.4%.

Cancer was the most common underlying terminal illness, with 762 (77.1%) patients (Table). Seventy-nine (8.0%) patients had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and 44 (4.5%) and 26 (2.6%), respectively, had incurable lung and heart disease. Nine patients (0.9%) had HIV or AIDS. Lung cancer was the most common malignant abnormality, with 177 (17.9%) cases, and breast cancer was the second most frequent, with 73 (7.4%) patients.

Table. Characteristics of 991 DWDA Patients Who Have Died From Ingesting Lethal Medicationa.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 509 (51.4) |

| Female | 482 (48.6) |

| Age at death, y | |

| 18-34 | 8 (0.8) |

| 35-44 | 23 (2.3) |

| 45-54 | 63 (6.4) |

| 55-64 | 205 (20.7) |

| 65-74 | 288 (29.1) |

| 75-84 | 259 (26.1) |

| ≥85 | 145 (14.6) |

| Raceb | |

| White | 953 (96.6) |

| Black | 1 (0.1) |

| Asian | 13 (1.3) |

| Hispanic | 10 (1.0) |

| Other, multiple, or unknown | 10 (1.0) |

| Underlying terminal illness | |

| Cancer | 762 (77.1) |

| Lung | 177 (17.9) |

| Breast | 73 (7.4) |

| Pancreas | 63 (6.4) |

| Colon | 61 (6.2) |

| Prostate | 40 (4.0) |

| Ovary | 36 (3.6) |

| Other | 312 (31.6) |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | 79 (8.0) |

| Respiratory disease | 44 (4.5) |

| Cardiac disease | 26 (2.6) |

| HIV/AIDS | 9 (0.9) |

| Other illness | 68 (6.9) |

| Unknown | 3 |

| End-of-life concerns | |

| Unable to enjoy activities of daily living | 885 (89.7) |

| Loss of autonomy | 903 (91.6) |

| Loss of dignityc | 677 (78.7) |

| Inadequate pain control | 248 (25.2) |

Data from the Oregon Health Authority, Oregon Public Health Division.3

Information available for 856 patients.

Information available for 860 patients.

Sex was relatively evenly divided, with 509 men (51.4%) and 482 (48.6%) women dying. Most of those dying (953, 96.6%) were white. Ninety-four patients (approximately 10%) were aged younger than 55 years. The youngest was 25. There were 145 (14.6%) patients who were 85 years or older and the eldest recorded user of DWDA medication was 102 years old. The median age was 71 years.

Most (865, 90.5%) patients were enrolled in hospice and had insurance. Most (708, 71.9%) had at least some college education.

Patients had a variety of reasons for requesting DWDA medication, as assessed by the prescribing physician. Nine-hundred three (92%) perceived loss of autonomy. Of 897 patients, 885 patients (89.7%) were unable to participate in enjoyable activities, and 677 (78.7%) cited loss of dignity. Few (474, 48.2%) worried about control of bodily functions. Two hundred forty-eight (25.2%) patients stated inadequate pain control contributed to their decision. A minority (30; 3.1%) of patients were concerned about treatment costs.

Discussion

Other studies have surveyed physician and patient attitudes toward PAD and described patient demographics in the United States and Europe,7 but this work is more detailed in terms of providing data on prescriptions received, patients consuming the lethal medications, and actual deaths. Oregon itself has the longest US experience with PAD. This study describes usage over the life of the Oregon DWDA and, to our knowledge, it is the most inclusive to date. Review of this period during which PAD has been legal is quite revealing and might guide future efforts to legalize PAD and/or help physicians caring for terminally ill patients.

We found that approximately two-thirds of patients having prescriptions written took the lethal medication(s), and nearly all died (>99%) when they did so. Cancer was the most common underlying terminal disease.

Though the rate of prescriptions written annually has increased steadily, this was not a result of simple growth in the Oregon resident population or increases in cancer death rates—both increasing by approximately 1.0% from 2014 to 2015 (Figure). Presumably the increase was at least in part related to further social acceptance of the DWDA. Notably, PAD deaths still make up well below 0.5% of citizen mortality in Oregon.

Inadequate symptom palliation has been cited as a reason patients seek PAD. Patients’ end-of-life concerns appear difficult to palliate, however; the most commonly cited reasons for taking lethal medications were loss of autonomy and dignity, and inability to enjoy life. A minority (248, 25.2%) of cases were associated with inadequate pain control, though that figure should be lower. In addition, although few patients were referred for psychiatric evaluation with questions of competency, increasing access to therapists and counseling for other purposes (eg, meaning-centered group psychotherapy, which has been demonstrated to improve spiritual well-being and end-of-life sense of meaning), could substantially help patients considering PAD.8

Limitations

The quality of our data is limited by the fact the attending physicians supplied the state with the underlying information (ie, primary records, such as death certificates, were not checked). In addition, because the physicians attested to the patients’ reasons for requesting DWD there is no way to ascertain whether the questioning of the patient was comprehensive.

Conclusions

We believe PAD is a promising area for formal, prospective research. Capturing more information on patients considering it (eg, how many had an underlying diagnosis of depression, whether tumors were primary or recurrent, and time since diagnosis) would be of great interest in guiding cancer care delivery research. It would be helpful to understand why patients prescribed lethal medications do or do not take them, whether an algorithm can be derived to advise patients on how long the medications will require to work, and whether we can better palliate end-of-life concerns, avoiding or delaying PAD.

References

- 1.University of Washington School of Medicine . Physician-Aid-in-Dying. https://depts.washington.edu/bioethx/topics/pad.html. Accessed Sept 14, 2016.

- 2.Oregon Public Health Authority . Death with Dignity statute. https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Pages/ors.aspx. Accessed Sept 14, 2016.

- 3.Oregon Health Authority, Oregon Public Health Division . Oregon Death With Dignity Act: 2015 Data Summary. February 4, 2016. https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year18.pdf. Accessed Sept 14, 2016.

- 4.Cox DR. The regression analysis of binary sequences (with discussion). J Roy Stat Soc B. 1958;20:215-242. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized Linear Models. 2nd ed. London: Chapman and Hall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 6.BBC . Execution drug. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-16281016. Accessed Sept 14, 2016.

- 7.Emanuel EJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Urwin JW, Cohen J. Attitudes and practices of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe. JAMA. 2016;316(1):79-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Gibson C, et al. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2010;19(1):21-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]