Abstract

Various diseases and toxic factors easily impair cellular and organic functions in mammals. Organ transplantation is used to rescue organ function, but is limited by scarce resources. Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)‐based therapy carries promising potential in regenerative medicine because of the self‐renewal and multilineage potency of MSCs; however, MSCs may lose biological functions after isolation and cultivation for a long time in vitro. Moreover, after they are injected in vivo and migrate into the damaged tissues or organs, they encounter a harsh environment coupled with death signals due to the inadequate tensegrity structure between the cells and matrix. Preconditioning, genetic modification and optimization of MSC culture conditions are key strategies to improve MSC functions in vitro and in vivo, and all of these procedures will contribute to improving MSC transplantation efficacy in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Preconditioning with various physical, chemical and biological factors is possible to preserve the stemness of MSCs for further application in studies and clinical tests. In this review, we mainly focus on preconditioning and the corresponding mechanisms for improving MSC activities in vitro and in vivo; we provide a glimpse into the promotion of MSC‐based cell therapy development for regenerative medicine. As a promising consequence, MSC transplantation can be applied for the treatment of some terminal diseases and can prolong the survival time of patients in the near future.

Keywords: preconditioning, mesenchymal stem cell, stemness, in vitro, in vivo

Introduction

Various diseases and toxic factors easily impair cellular and organic functions in mammals; parenchymal cells and stromal cells move into an apoptotic state, accelerating the development of injury or disease. If the functions cannot be repaired in a timely manner, multiple complications will occur as a consequence. Previously, organ transplantation was the only effective repair for tissue injury, whereas cell transplantation has gradually become a burgeoning route for regenerative medicine. However, transplantation of primary cells is limited by scarce resources; therefore, stem cell transplantation becomes a hot topic in current tissue engineering. In general, stem cells are classified as embryonic stem cells (ESCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and adult stem cells such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and other tissue‐specific stem cells 1. ESCs are stem cells isolated from the inner cell mass of early‐stage embryos; they can proliferate indefinitely without a senescent phenotype and differentiate into all cell lineages 2. Transcription factors such as OCT4 and NANOG are indispensable for maintaining the high pluripotency state of ESCs 3, and then, iPSCs were generated via conversion of somatic cells into an ESC‐like pluripotent state by overexpression of several vital transcription factors 4. Although both of them have extreme pluripotency, unlimited self‐renewal and multilineage potency, their application should be considered carefully because of potential ethical problems, safety issues and low efficiency 5. MSCs, which are prevalent in tissues, exist in almost all kinds of tissues, and they are adult stem cells with multilineage potentials 6. There are no ethical issues associated with their use, and they serve as a promising cell source for cell‐based therapy to maintain homeostasis under physiological and pathological conditions 7, 8. Furthermore, the low immunological rejection rate permits their autotransplantation and allogeneic transplantation applications 9. MSCs exhibit plastic adherence and fibroblast spindle‐like‐shaped morphology when cultured in vitro and can highly proliferate and differentiate towards adipocytes, osteocytes, chondrocytes, hepatocytes, endothelial cells, cardiomyocytes, neural cells, etc. 1, 10, 11, 12. MSCs have been reported to exert various effects on host cells or organs via immunomodulation 13: pro‐angiogenic 14, antiapoptotic 15 and antioxidative effects 16 and activation of local quiescent stem cells 17. In fact, MSCs together with local somatic cells establish cell‐to‐cell interactions and produce autocrine and paracrine factors 18, and culture medium isolated from MSCs also contains biological factors including mRNAs, microRNAs and enzymes that protect cells or organs from further damage 19. Moreover, cell fusion of MSCs also contributes to the repair of tissues or organ function 13, 14; it occurs rarely and is classified into two types, namely homotypic and heterotypic cell fusions, with the former occurring between the same lineage, while the latter occurs between different lineages 15. In addition, evidence demonstrated that MSCs could still transdifferentiate into cardiomyocytes or neural cells at low rates after infusion or injection in mammals although MSCs mainly promoted the regeneration of injured organs through paracrine mechanism 12, 16.

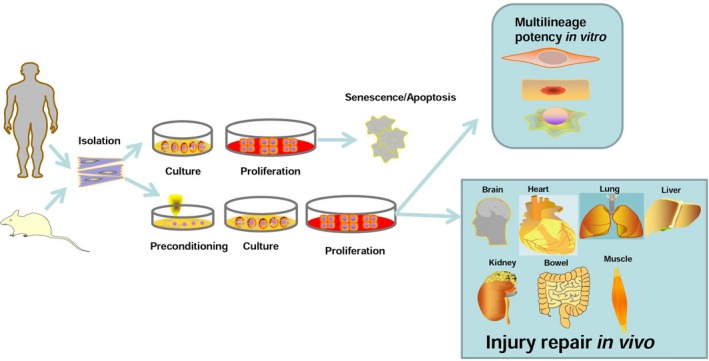

MSCs reside in the general microenvironment with low oxygen tension (i.e. 1–5% O2) in vivo, while the oxygen concentration of the general culture environment (i.e. 20–21% O2) is higher than their original living environment 17, 20. The changed culture oxygen tension in vitro may decrease the cell activities, including proliferation, differentiation, the anti‐inflammatory response, and also decrease the cell activities for repairing dysfunctional organs 21, 22. MSCs are generally deprived of nutrients and oxygen after isolation ex vivo, and the addition of trophic factors is not enough to maintain the cell activities for further application 20. MSCs isolated from unhealthy individuals or those that have proliferated for a long period will have an impaired self‐renewal ability and physiological state 23, 24. In contrast, transplanted MSCs are confronted with apoptosis or senescence attributed to harsh environmental conditions, anoikis and inflammation induced by damaged tissues or organs 25, which leads to an imbalance between the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant mechanisms 26. Inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils, monocytes and macrophages, which are recruited by chemokines or cytokines, will induce apoptosis and inactivate the cytoprotective production of nitric oxide (NO) 27. The acute inflammatory response promotes angiogenesis and the recruitment of progenitor cells, while chronic inflammation inhibits the recruitment and survival of local progenitor cells and implanted MSCs 28. To this end, MSCs have been shown to protect tissues and organs from external injury; however, investigating more effective routes to improve their therapeutic effects is still necessary (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

After isolation in vitro, MSCs can be pretreated with various protective factors to improve survival rate and further enhance its application in vitro and in vivo.

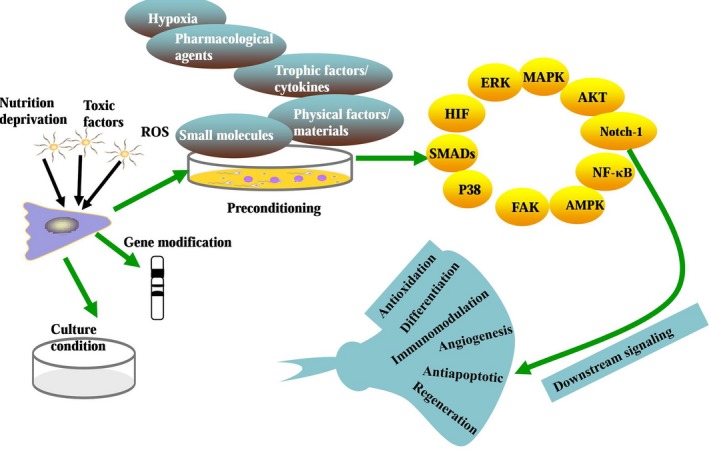

Preconditioning, genetic modification and optimization of MSC culture conditions are key strategies to improve MSC function in vitro and in vivo. All of these procedures contribute to improving MSC transplantation efficacy in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine 29. Recently, studies have demonstrated that pretreated MSCs showed better cell survival, increased differentiation efficacy, enhanced paracrine effects and an improved homing ability into injury sites 29, 30, 31. Preconditioning of MSCs by hypoxia, pharmacological agents, chemical agents, trophic factors, cytokines and physical factors prior to their application is capable of initiating survival signalling to counter the rigorous harsh microenvironment for MSC transplantation application (Fig. 2). However, the optimization of these external factors for MSC preconditioning and the underlying mechanisms should be further investigated to improve MSC therapeutic effects. Currently, the mechanisms of preconditioning with hypoxia and other important strategies (Tables 1 and 2) have been widely investigated in experimental studies and clinical trials. In this review, we mainly focus on the preconditioning and the corresponding mechanisms for improving MSC activities in vitro and in vivo. In this way, we provide a glimpse in the promotion of MSC‐based cell therapy development for regenerative medicine. As a promising consequence, MSC transplantation can be applied for the treatment of some terminal diseases and can prolong the survival time of patients in the near future.

Figure 2.

Preconditioning, genetic modification and optimization of MSC culture conditions are key strategies to improve MSC function in vitro and in vivo, and preconditioning is effective at activating various important signalling pathways for protecting cells and organs from injury.

Table 1.

Hypoxia and the potential mechanisms for preconditioning on MSCs

| O2 content | Effect | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5% | Counteracts the deficiency of adipose‐derived MSCs from older donors and highly improves their differentiation capacity | Acts as a protective factor | 23 |

| 1% | Prevents the apoptosis of MSCs | Increases the secretion of angiogenic factors, VEGF and basic fibroblast growth factor (BFGF) in MSCs | 36 |

| 1% | Decreases the sensitivity of MSCs to the ischaemic microenvironment without changing their biological behaviour, immunophenotype or karyotype | Increases the metabolic activity and decreases the caspase‐3/7 activity and lactate dehydrogenase release of MSCs | 37 |

| 2% | Decreases tumorigenic potential of MSCs | Down‐regulates the expression levels of tumour‐suppressor genes and TERT and the suboptimal double‐stranded DNA breaks in MSCs | 17 |

| 3% | Improves the genetic stability and chromosome stability and guarantees the safety of MSCs | Decreases the incidence of aneuploidy in MSCs | 38 |

| 5% | Enhances the clonogenic potential and proliferation rate of MSCs | Up‐regulates the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secretion in MSCs | 35 |

| 5% | Exerts no effect on the phenotype or differentiation ability of MSCs but significantly enhances the autophagy progress | Increases the expression of HIF‐1α and activates the AMPK/mTOR signalling pathway | 39 |

| 0.1–0.3% | Promotes neurogenesis and neurological functional recovery | Promotes the secretion of various growth factors including brain‐derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), glial cell line‐derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) and VEGF | 40 |

| 0.5% | Improves the motor and cognitive function of the animal models | Promotes the secretion of growth factors including hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and VEGF | 42 |

| 0.5% | Suppresses microglia activity in the brain and promotes locomotion recovery | Up‐regulates the expression levels of HIF‐1α, the VEGF receptor, erythropoietin (EPO), the EPO receptor, stromal‐derived factor‐1 (SDF‐1) and CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) but decreases the release of pro‐inflammatory cytokines | 43 |

| 1% | Promotes liver regeneration in massive hepatectomy models | Increases the expression of cyclin D1 and VEGF, enhances the proliferation of hepatocytes and increases the liver weight/bodyweight ratio | 41 |

| 1% | Improves the intracavernosal pressure and erectile function in diabetes models | Up‐regulates the release of angiogenesis‐ and neuroprotection‐related factors including VEGF, the VEGF receptor, angiotensin, BFGF, BDNF, GDNF, SDF‐1 and CXCR4; up‐regulates the expression levels of NO synthases, endothelial markers and smooth muscle markers | 45 |

| 1.5% | Compensates the loss of lung functions in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis models | Improves the proliferation, migration, angiogenesis, antioxidant, antiapoptotic and antifibrotic properties of implanted MSCs | 46 |

| 1.5% | Guarantees the safety of cell transplantation | Inhibits the malignant transformation of MSCs | 47 |

| 1–7% | Repairs the injury in a murine hindlimb ischaemia model | Activates the HIF‐1α/GRP78/Akt signal axis | 48 |

| 2% | Promotes the recovery of the ischaemic tissue | Improves the expression of prion protein (PrPC), activates PrPC‐dependent JAK2 and STAT3 signalling pathways, and then up‐regulates the activity of superoxide dismutase and catalase | 49 |

| 2% | Inhibits the rabbit femoral head osteonecrosis | Increases the angiogenesis function and decreases the tissue apoptosis | 50 |

| 5% | Facilitates revascularization in diabetic lower limb ischaemia (DLLI) | Increases the expression levels of angiogenin, matrix metallopeptidase (MMP)‐9, VEGF‐1α and HIF‐1α and activates the p‐AKT signalling pathway | 51 |

Table 2.

Other important agents and the potential mechanisms for preconditioning on MSCs

| Type | Agent | Effect | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical drugs | Lenalidomide | Up‐regulates the erythroid and myeloid colony formation of early haematopoietic progenitors of MSCs | Reduces the release of stromal‐derived factor 1‐alpha and cobblestone area formation | 53 |

| Vitamin E | Reduces oxidative stress and senescence induced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in MSCs | Up‐regulates the expression levels of proliferative markers and transforming growth factor‐beta (TGF‐β), while it reduces the expression levels of apoptosis‐related genes and the release of VEGF and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | 54 | |

| Low‐dose LPS | Inhibits the apoptosis of MSCs induced by hypoxia and serum deprivation (H/SD) | Preserves the mitochondrial membrane potential and inhibits cyto C release; activates the ERK signalling pathway | 55 | |

| Sevoflurane | Maintains the survival and migration rates of MSCs under condition of H/SD | Up‐regulates the expression levels of HIF‐1α, HIF‐2α, VEGF and p‐Akt/Akt | 56 | |

| Valproic acid | Promotes hepatogenic differentiation of MSCs | Activates the AKT and ERK signalling pathways | 57 | |

| Astragaloside IV | Promotes the proliferation of MSCs and inhibits the high glucose‐induced expression of Toll‐like receptor 4 (TLR4) in MSCs | Decreases the translocation of NF‐κB p65 and increases the level of MMP‐2 | 58 | |

| Apple extract | Enhances the proliferative ability of MSCs | Up‐regulates the phosphorylation of p44/42 MAPK, mTOR, p70S6K, S6RP, eIF4B and eIF4E and up‐regulates the release of VEGF and interleukin‐6 | 59 | |

| Icariside II | Promotes the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of MSCs | Up‐regulates the PI3K/AKT/mTOR/S6K1 signalling pathways | 60 | |

| Genistein | Enhances cell proliferation and adipogenic differentiation of MSCs but inhibits the osteogenic progress | Up‐regulates the expression of PPARγ | 61 | |

| Oxytocin | Promotes the cell proliferation and migration of MSCs; protects against the H/SD‐induced cytotoxic and apoptotic effects on MSCs | Activates the Akt/ERK1/2 pathway | 62 | |

| Deferoxamine | Increases the migration of MSCs in vitro and homing ability of MSCs in vivo | Increases the expression of HIF‐1α, CXCR4, C‐C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2), MMP‐2 and MMP‐9 | 63 | |

| Atorvastatin | Enhances the cardiac function and improves post‐implantation survival of MSCs | Activates the eNOS/NO system | 24 | |

| 2,4‐Dinitrophenol (DNP) | Improves cardiac function and reduces scar formation after MSC transplantation | Up‐regulates angiogenesis in myocardial infarction models | 64 | |

| Angiotensin II | Decreases the degree of cardiac fibrosis and infarct size after MSC transplantation | Up‐regulates the release of growth factors | 65 | |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) | Maintains the left ventricular ejection fraction after MSC transplantation | Improves the cardiomyogenic transdifferentiation of MSCs | 66 | |

| OT | Improves cardiac function and reduces fibrosis in a rat myocardial infarction model after MSC transplantation | Up‐regulates the expression level of Krüppel‐like factor 2 (KLF2) and angiogenic differentiation ability of MSCs | 67 | |

| Melatonin | Protects brain function from injury | Activates the ERK signalling pathway | 69 | |

| Rapamycin (RAP) | Promotes the osteogenesis of MSCs in vitro and in vivo | Activates the autophagy | 70 | |

| Vitamin E | Impedes the progression of osteoarthritis and increases potential to treat osteoarthritis after MSC transplantation | Increases the proteoglycan content in the cartilage matrix | 54 | |

| All‐trans retinoic acid (ATRA) | Enhances the tube formation and the in vivo wound healing ability after MSC transplantation | Increases the expression levels of cytochrome c oxidase (COX)‐2, HIF‐1, CXCR4, CCR2, VEGF, angiogenin‐2 and angiogenin‐4 in MSCs | 71 | |

| Polyribocytidylic acid | Rescues the trinitrobenzene sulphonate (TNBS)‐induced colitis mouse models after MSC transplantation | Activates the Notch‐1 signalling pathway | 72 | |

| Small molecules | BAY 11‐708 | Blocks the pro‐angiogenesis and antiapoptosis function of MSCs | Inhibits the NF‐κB activity | 73 |

| LL‐37 | Enhances the MSC proliferation and migration | Activate the MAPK signalling pathway | 74 | |

| Dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG) | Improves the therapeutic effects of MSCs for reducing heart infarct size and promoting functional repair in myocardial infarction | Increases the expression levels of survival and angiogenic factors including HIF‐1α, VEGF, glucose transporter 1 and phospho‐AKT in MSCs | 76 | |

| JI‐34 | Enhances the differentiation into endothelial tube cells in vitro and improves the engraftment of MSCs into hemic hindlimb muscles for repairing injured parts | Serves as a growth hormone‐releasing hormone agonist | 78 | |

| Cytokines | Stromal‐derived factor‐1 (SDF‐1) | Protects MSCs from H2O2‐induced apoptosis | Enhances the proliferation, migration, and survival rate of MSCs; up‐regulates the release of angiogenic cytokines and activates the AKT and ERK signalling pathways | 81 |

| TGF‐β1 | Drives MSC fate towards osteoblasts generation in vitro, while it inhibits adipogenic differentiation of MSCs; switches MSCs from adipogenesis into osteogenesis | Activates SMAD/C/EBPs/PPARγ signalling pathways | 82 | |

| TNF‐α | Enhances proliferation, mobilization and osteogenic differentiation of MSCs | Activates the ERK1/2 and MAPK signalling pathways | 83 | |

| Interferon (IFN)‐γ | Suppresses natural killer (NK) activation and NK‐mediated cytotoxicity partly | Up‐regulates the synthesis of indoleamine 2,3‐dioxygenase (IDO) and prostaglandin E2 | 84 | |

| IL‐1 and TNF‐α | Inhibits the osteogenesis and adipocyte generation of MSCs | Activates the canonical NF‐κB signalling, IL‐1R1/MyD88 signalling pathway | 85, 86 | |

| TNF‐α and IFN‐γ | Promotes the generation of anti‐inflammatory M2 macrophages and suppresses the human peripheral blood mononuclear cell proliferation | Increases the production of IDO | 87 | |

| IL‐1β | Improves the migration ability of MSCs | Increases the expression levels of various cytokines and chemokines, as well as adhesion molecules in MSCs | 89 | |

| TGF‐β1 | Induces MSC migration into the remodelling sites and couples bone formation and resorption | Activates the canonical SMADs signalling pathway or the non‐canonical signalling pathways involving AKT, ERK1/2, FAK and p38 | 91 | |

| TGF‐β1 | Prolongs the effective therapy time in damaged lungs | Improves the survival of MSCs and enhances the expression of extracellular matrix components, particularly fibronectin in damaged lungs | 92 | |

| Oncostatin M (OSM) | Maintains pulmonary respiratory function, and down‐regulates the release of inflammatory and fibrotic factors in bleomycin‐induced lung fibrotic mice | Increases the expression of type 2 OSM receptor and HGF in MSCs | 93 | |

| IFN‐α | Improves the therapeutic effects on dextran sodium sulphate (DSS)‐ and TNBS‐induced colitis after MSC transplantation | Increases the migration potential of MSCs and inhibits Th1 inflammatory responses | 94 | |

| Migration inhibitory factor (MIF) | Maintains the proliferation and survival of aged MSCs in vivo | Improves the secretion of various growth factors including VEGF, BFGF, HGF and insulin‐like growth factor (IGF) | 95 | |

| Physical factors | Low‐level lasers | Improves the proliferation rate, enhances mitochondrial biogenesis and improves the migration ability of MSCs | Up‐regulates the generation of ROS and NO, activates the ERK1/2 and FAK signalling pathways and up‐regulates the expression levels of HGF and platelet‐derived growth factor (PDGF) | 96 |

| Pulsed electromagnetic fields (PEMF) | Decreases the cell death rate of MSCs | Up‐regulates the expression of AKT and RAS | 97 | |

| Silica | Increases the proliferation of MSCs or induces a slight increase in apoptosis | Improves the phosphorylation of ERK1/2; up‐regulates the phosphorylation of p38 | 98 | |

| Mechanical stretch | Increases the angiogenic capacity and survival rate of MSCs | Up‐regulates the activities of VEGFA and NF‐κB p65 | 73 | |

| GFc7 | Increases the quality and differentiation rate of MSCs | Improves cell proliferation, expression of pluripotency genes and homing markers and antioxidative defence; represses the spontaneous differentiation‐related genes while it enhances the levels of specific differentiation‐related genes | 99 | |

| Selenite | Recovers the osteoblastic differentiation of MSCs | Inhibits the activation of the ERK signalling pathway | 100 | |

| Carboxyl‐terminated hyperbranched polyester (CHBP) | Provides more resistance for MSCs to starvation‐induced oxidative stress in a dose‐dependent manner | Maintains the MMP and mitochondrial membrane integrity and activates the Nrf2/Sirt3/FoxO3a pathway | 101 |

Hypoxia preconditioning for improving the cell activities of MSCs

O2 is essential for cellular homeostasis as the lack of O2 is involved in the pathogenesis of some diseases with high morbidity and mortality 32. Hypoxia preconditioning including culturing for 15 min at 2.5% O2, reoxygenation for 30 min at 21% O2 and hypoxia preconditioning for 72 hrs at 2.5% O2 significantly improves the proliferation and migration abilities of MSCs in vitro 33. Hypoxia reduces the cell viability and proliferation of MSCs but the following reoxygenation promotes the recovery of MSCs, and the process of hypoxia and reoxygenation (H/R) improves the expression of pro‐survival genes and various trophic factors in MSCs 34; moreover, hypoxia or H/R has been proven to promote multipotency of MSCs in determined microenvironments in vitro 33, 35. Considering the advantages of hypoxia or H/R, current studies have focused on the optimization of oxygen concentrations to improve the cell activities and therapeutic effects of MSCs. Hypoxia at 0.5% O2 for 24 hrs can act as a protective factor to effectively counteract the deficiency of adipose‐derived MSCs from older donors and highly improve their differentiation capacity 23. When incubated in low‐serum medium, MSCs will move into an apoptotic state, but hypoxia preconditioning (1% O2) can prohibit the damage via increasing the secretion of angiogenic factors, VEGF and basic fibroblast growth factor (BFGF) 36. Moreover, 1% O2 also increases the metabolic activity and decreases the caspase‐3/7 activity and lactate dehydrogenase release of MSCs, thus decreasing the sensitivity of MSCs to the ischaemic microenvironment without changing their biological behaviour, immunophenotype or karyotype 37. The decreased tumorigenic potential of MSCs induced by 2% O2 has been demonstrated to be mediated by the down‐regulation of the expression levels of tumour‐suppressor genes and TERT and the induction of suboptimal double‐stranded DNA breaks in MSCs in vitro 17. Intriguingly, a hypoxic condition at 3% O2 decreases the incidence of aneuploidy in MSCs compared to that in the normoxic condition at 20% O2, indicating that pretreatment with hypoxia improves the genetic stability and chromosome stability and guarantees the safety of MSCs in vitro 38. Culture in 5% ambient O2 consistently enhances the clonogenic potential and proliferation rate of MSCs via up‐regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secretion 35. Liu et al. 39 demonstrated that 5% O2 exerted no effect on the phenotype or differentiation ability of MSCs but significantly enhanced the autophagy by increasing the expression of HIF‐1α and the activation of the AMPK/mTOR signalling pathway. While Boyette et al. 35 proved that 5% ambient O2 improved the osteogenesis and chondrogenesis of MSCs expanded under normoxia, while it inhibited the adipogenesis and chondrogenesis of MSCs expanded under three‐dimensional pellet conditions.

After transplantation in vivo, the pathological environment significantly decreases the self‐renewal and survival rate of MSCs. Evidence has shown that transplantation of hypoxia‐pretreated MSCs enhanced the therapeutic effects via up‐regulating the secretion of cytokines and growth factors 40, 41. After hypoxia preconditioning (0.1–0.3% O2), transplanted MSCs migrate into peri‐injury regions in the intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke brain and promote neurogenesis and neurological functional recovery through secreting various growth factors, including brain‐derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), glial cell line‐derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) and VEGF 40. In traumatic brain injury rats, hypoxia preconditioning at 0.5% O2 promotes MSCs to secrete more growth factors, including hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and VEGF, to improve the motor and cognitive functions of the animal models 42. In addition to the above‐mentioned growth factors, the expression levels of HIF‐1α, the VEGF receptor, erythropoietin (EPO), the EPO receptor, stromal‐derived factor‐1 (SDF‐1) and CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) were improved, while the release of pro‐inflammatory cytokines was decreased by MSCs preconditioned with hypoxia at 0.5% O2. Furthermore, these pretreated MSCs have been demonstrated to suppress microglia activity in the brain and promote locomotion recovery more effectively than a normoxia‐cultured MSC group 43. Although MSCs that are pretreated by hypoxia at 0.5% O2 can improve the left ventricular function of monkeys with myocardial infarction more effectively than normoxia‐cultured MSCs, they are not able to increase the occurrence of arrhythmogenic complications 44. MSCs that are pretreated under 1% O2 have been shown to promote liver regeneration in massive hepatectomy models via increasing expression of cyclin D1 and VEGF, enhancing proliferation of hepatocytes and increasing the liver weight/bodyweight ratio 41. Sublethal oxygen concentration (1%) up‐regulates the release of angiogenesis‐ and neuroprotection‐related factors including VEGF, the VEGF receptor, angiotensin, BFGF, BDNF, GDNF, SDF‐1 and CXCR4 in MSCs, and transplantation of these cells significantly up‐regulates the expression levels of NO synthases, endothelial markers and smooth muscle markers and also improves the intracavernosal pressure and erectile function in diabetes models 45. Preconditioning with 1.5% O2 enhances the activities of MSCs and effectively improves the proliferation, migration, angiogenesis, antioxidant, antiapoptotic and antifibrotic properties of implanted MSCs to compensate the loss of lung functions in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis models 46. Most importantly, preconditioning with hypoxia at 1.5% O2 inhibits the malignant transformation of MSCs after transplantation and thus highly guarantees the safety of cell transplantation 47. After transplantation in a murine hindlimb ischaemia model, MSCs that are pretreated by 1% to 7% O2 activate the HIF‐1α/GRP78/Akt signal axis for repairing the injury 48; moreover, 2% O2 improves the expression of prion protein (PrPC), activates PrPC‐dependent JAK2 and STAT3 signalling pathways and then up‐regulates the activity of superoxide dismutase and catalase to inhibit the oxidative stress‐induced apoptosis of MSCs and promote the recovery of the ischaemic tissue 49. Transplantation of 2% O2‐treated MSCs significantly increases the angiogenesis function and decreases the tissue apoptosis in rabbit femoral head osteonecrosis compared to that observed in 20% O2‐treated MSCs 50. MSCs that are pretreated with hypoxia at 5% O2 can not only improve the migratory and tube‐forming capacities of endothelial cells in vitro but also facilitate revascularization in diabetic lower limb ischaemia (DLLI) via increasing the expression levels of angiogenin, matrix metallopeptidase (MMP)‐9, VEGF‐1α and HIF‐1α and activation of the p‐AKT signalling pathway 51. Although most studies have proven that hypoxia is a protective factor for MSCs in vitro and in vivo, determining the optimal oxygen concentration for improving the survival rate and therapeutic effects of MSCs is still necessary.

Preconditioning with pharmacological or chemical agents for MSC‐based regenerative medicine

Various drugs exert therapeutic effects in different diseases and protect organs from further loss of function, thus elongating the long‐term survival rate of patients. In current studies, specialists focus on investigating the underlying mechanisms of drugs to protect MSCs from injury and improve their application in regenerative medicine. Although special medications have been demonstrated to exert protective effects on MSCs, as a premise, extremely high concentrations of drugs will impair the function of MSCs. Thus, exploring the optimal concentration of drugs for MSCs in vitro and in vivo is a prerequisite. High concentrations of zoledronic acid inhibited the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow‐derived MSCs, while low concentrations of zoledronic acid played the opposite role without influencing their immunomodulatory properties 52. Preconditioning with drugs is presumed to be responsible for protecting against ischaemic injury during stem cell transplantation and further activating endogenous cellular machinery for regeneration.

Under the pathological state in various diseases, the self‐renewal and differentiation abilities of MSCs are undoubtedly decreased, thus limiting the supply of cell resources for basic application. For instance, MSCs isolated from those with low‐ but not high‐risk myelodysplastic syndrome demonstrated a lower erythroid and myeloid colony formation of early haematopoietic progenitors; fortunately, preconditioning with lenalidomide effectively rescued the dysfunction in the disease‐derived MSCs 53. Because hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) induces oxidative stress and senescence in MSCs in vitro, vitamin E pretreatment counteracts the injury and up‐regulates the expression levels of proliferative markers and transforming growth factor‐beta (TGF‐β), while it reduces the expression levels of apoptosis‐related genes and the release of VEGF and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in vitro 54. Hypoxia and serum deprivation (H/SD) in vitro initiates apoptosis of MSCs, while preconditioning of MSCs with low‐dose lipopolysaccharide (LPS) preserves the mitochondrial membrane potential and inhibits cyto C release in H/SD‐cultured MSCs; LPS preconditioning also decreases the expression of connexin 43 via regulation of the ERK signalling pathway, thus stabilizing the cell membrane of MSCs 55. Preconditioning with sevoflurane up‐regulates the expression levels of HIF‐1α, HIF‐2α, VEGF and p‐Akt/Akt and prevents the initiation of apoptosis and loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential, thus maintaining the survival and migration rates of MSCs after H/SD 56. In addition, valproic acid (VPA), a histone deacetylase inhibitor with anticonvulsive function, takes part in the promotion of hepatogenic differentiation via activation of the AKT and ERK signalling pathways and up‐regulation of the expression of endodermal genes in MSCs in vitro 57. Chinese medicines and some natural extracts have also been applied to protect MSCs from injury and enhance the differentiation content of MSCs in vitro. Astragaloside IV, which can resist oxidative stress‐induced injury, has been used to promote the proliferation of MSCs and inhibit the high glucose‐induced expression of Toll‐like receptor 4 (TLR4) in MSCs via decreasing the translocation of NF‐κB p65 and increasing MMP‐2 expression 58. Apple extract dose dependently enhances the proliferative ability of adipose‐derived MSCs via phosphorylation of p44/42 MAPK, mTOR, p70S6K, S6RP, eIF4B and eIF4E and up‐regulation of the release of VEGF and interleukin‐6 59. Preconditioning with icariside II (ICSII) has been demonstrated to promote the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow‐derived MSCs via up‐regulating PI3K/AKT/mTOR/S6K1 signalling pathways, and wortmannin or rapamycin neutralizes the transition and acts as antagonists for this type of Chinese medicine 60. Genistein, which is a type of phytoestrogen, has anti‐inflammatory and antioxidative abilities; it exerts different effects on MSCs as it enhances cell proliferation and adipogenic differentiation of MSCs but inhibits the osteogenic progress by up‐regulating PPARγ expression 61. On the other hand, hormones that can maintain the homeostasis of mammals and protect organs from injury contribute to the preconditioning of MSCs in vitro. Oxytocin (OT), which is secreted from the hypothalamus, induces activation of the Akt/ERK1/2 pathway to promote the cell proliferation and migration of MSCs, thus protecting against the H/SD‐induced cytotoxic and apoptotic effects on MSCs 62.

Preconditioning of MSCs with various drugs in vitro also improves the therapeutic effects of MSCs in vivo for multiple diseases by repairing the lost functions via regulation of various pathways. Deferoxamine (DFO), a type of iron chelator, increases the migration in vitro and homing ability in vivo of MSCs via increasing the expression of HIF‐1α, CXCR4, C‐C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2), MMP‐2 and MMP‐9 but can be significantly down‐regulated by an HIF‐1α inhibitor, namely 2‐methoxyestradiol 63. Atorvastatin is widely used in coronary heart disease for inhibiting hyperlipidaemia, preconditioning with which has been demonstrated to enhance cardiac function and improve post‐implantation survival via activation of the eNOS/NO system in MSCs 24. 2,4‐Dinitrophenol (DNP)‐pretreated MSCs significantly improve cardiac function and reduce scar formation via up‐regulation of angiogenesis in myocardial infarction models 64. The renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) takes part in physiological processes by responding to external stimuli, and pretreatment with the derivatives of RAAS can effectively influence MSC activities in vivo. Transplantation of angiotensin II‐pretreated MSCs leads to less cardiac fibrosis, smaller infarct size via up‐regulation and the release of growth factors in the myocardial infarcted myocardium, whereas there is no promotion of cardiogenic differentiation in MSCs 65. Pretreatment with angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) increases the cardiomyogenic differentiation efficiency of MSCs in vitro. Furthermore, transplantation of ARB‐pretreated MSCs can significantly maintain the left ventricular ejection fraction in vivo 66. Streptozotocin is widely used to produce diabetes models, and MSCs isolated from these models show severely impaired proliferation and angiogenic activities. OT significantly reversed the self‐renewal and differentiation ability of these MSCs in vivo. Consequently, transplantation of OT‐pretreated diabetes‐derived MSCs significantly improves cardiac function and reduces fibrosis in a rat myocardial infarction model 67. VPA pretreatment significantly up‐regulates the expression levels of neuroprogenitor markers including nestin, Musashi, prominin 1 and glial fibrillary acidic protein and consequently increases the number and neurite length of neurogenic MSCs 68. In a cerebral ischaemia model, melatonin pretreatment increases the post‐transplantation survival of implanted MSCs and protects brain function from injury via activating the ERK signalling pathway 69. In spite of cardiogenic differentiation and neural differentiation, other drugs have been used to improve the other differentiation abilities of MSCs in vivo. Rapamycin (RAP), which is an antifungal antibiotic, can significantly promote the osteogenesis of MSCs in vivo by the activation of autophagy, but the effect can be reversed by an autophagy inhibitor, namely 3‐methyladenine 70. The transplantation of vitamin E‐pretreated MSCs increases the proteoglycan content in the cartilage matrix for chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs 54. Preconditioning with all‐trans retinoic acid (ATRA) increases the expression levels of cytochrome c oxidase (COX)‐2, HIF‐1, CXCR4, CCR2, VEGF, angiogenin‐2 and angiogenin‐4 in MSCs, which can be reversed by a selective COX‐2 inhibitor, namely celecoxib, in vitro; ATRA‐pretreated MSCs enhance tube formation and the in vivo wound healing ability 71. Pretreatment of umbilical cord‐derived MSCs with polyribocytidylic acid enhances the therapeutic efficiency in trinitrobenzene sulphonate (TNBS)‐induced colitis mouse models; Notch‐1 signalling promotes the release of prostaglandin E2 for immune suppression of umbilical cord‐derived MSCs 72. Although drugs exert their specific protective effects on MSCs and promote the repair of injured tissues via enhancing MSC activities after transplantation, whether the drugs have adverse effects on MSC properties should be further investigated for their safe application.

In regenerative medicine, small molecules are applied to generate iPSCs from somatic cells and contribute to current cell and tissue engineering. They have been demonstrated to participate in the regulation of MSC fate in vitro and in vivo, although whether the effects are advantageous or disadvantageous should be further investigated. As shown above, mechanical stretch increases VEGFA expression and resistance to apoptosis. A small molecule, namely BAY 11‐708, blocks the pro‐angiogenesis and antiapoptosis function of MSCs via the inhibition of NF‐κB activity 73. As a naturally occurring antimicrobial peptide that can effectively enhance the proliferative and migratory abilities of MSCs to assist in wound repair, LL‐37 has been demonstrated to contribute to the improvement of MSC proliferation and migration by activation of the MAPK signalling pathway 74. Dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG) is a prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor that induces the migration of MSCs into peripheral blood circulation. However, Ge et al. 75 showed that DOMG‐pretreated MSCs had a similar immune phenotype and multilineage differentiation capability as control MSCs, and the release levels of transforming growth factor (TGF) and PDGF were comparable in both groups. DMOG can effectively increase the expression levels of survival and angiogenic factors including HIF‐1α, VEGF, glucose transporter 1 and phospho‐AKT in MSCs and improve the therapeutic effects of MSCs via reducing heart infarct size and promoting functional repair in myocardial infarction after transplantation 76. Pretreatment with RU486, an antagonist of the glucocorticoid receptor, significantly increases the proliferation of human MSCs in a gender‐dependent way and enhances the expression of osteogenic markers in osteogenic MSCs compared to that observed in control MSCs 77. Moreover, preconditioning with JI‐34, a growth hormone‐releasing hormone agonist, enhances the differentiation into endothelial tube cells in vitro and improves the engraftment of MSCs into hemic hindlimb muscles for repairing injured parts 78. Although small molecules are widely used in current reprogramming programmes, they are still a negligible portion of active factors for preconditioning of MSCs, and a large number of small molecules should be developed for the protection of MSCs.

Trophic factors and cytokines for regulation of MSC fate

The interaction between growth factor and its receptors activates the downstream signal transduction for cell survival and cell differentiation; thus, growth factor and cytokine preconditioning may influence the host tissue through paracrine/autocrine pathways. MSCs contain a variety of trophic factors or cytokines with biological functions including immunomodulatory properties 79 and anti‐inflammatory capacities 80. Despite the promising results, one impediment is that the short biological half‐lives of the growth factors inhibit the stable therapeutic effects. SDF‐1 pretreatment protects MSCs from H2O2‐induced apoptosis via enhancing the proliferation, migration and survival rate; concurrently, angiogenic cytokines including BFGF and VEGF and pro‐survival signalling pathways including AKT and ERK are also up‐regulated by preconditioning with SDF‐1 81. Intriguingly, TGF‐β1 drives MSC fate towards osteoblasts generation in vitro, while it inhibits adipogenic differentiation; furthermore, the addition of TGF‐β1 into adipogenic medium switches MSCs from adipogenesis into osteogenesis, mainly through activating SMAD/C/EBPs/PPARγ signalling pathways 82. A short‐term preconditioning with TNF‐α on MSCs enhances proliferation, mobilization and osteogenic differentiation via activation of ERK1/2 and MAPK signalling pathways, whereas silencing by siRNA can partially inhibit ERK1/2 signalling and osteogenic differentiation of MSCs 83. Pretreatment of MSCs with interferon (IFN)‐γ suppresses natural killer (NK) activation and NK‐mediated cytotoxicity partly via up‐regulating the synthesis of indoleamine 2,3‐dioxygenase (IDO) and prostaglandin E2 84. On the other hand, an optimal combination of growth factors for directed differentiation of stem cells into the desired lineage remains a challenge. IL‐1 and TNF‐α inhibit the osteogenesis and adipocyte generation of MSCs via activating the canonical NF‐κB signalling 85 and IL‐1R1/MyD88 signalling pathway 86. Moreover, the addition of TNF‐α and IFN‐γ into MSCs in vitro increases the production of IDO for the generation of anti‐inflammatory M2 macrophages and the suppression of human peripheral blood mononuclear cell proliferation 87. A sequential pretreatment with BFGF followed by sex steroid hormones highly improves the expression of neural markers and promotes the differentiation efficacy of bone marrow‐derived MSCs 88.

Preconditioning with various cytokines have also been proven to have protective effects on injury models and can participate in the regulation of cell fate. Preconditioning with IL‐1β increases the expression levels of various cytokines including TNF‐α, IL‐6, IL‐8 and IL‐23A and chemokines such as CCL5, CCL20, CXCL1, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6, CXCL10 and CXCL11, as well as adhesion molecules such as vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)‐1, intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)‐1 and ICAM‐4 in MSCs, thus improving the migration ability of MSCs to the site of inflammation in vivo 89. In addition, IL‐1β pretreatment not only increases the proliferation but also up‐regulates the chondrogenic potential of synovial MSCs; however, high concentrations of IL‐1β exert adverse effects on synovial MSCs by reducing the adhesion ability and pluripotency 90. TGF‐β1, which can be released from the bone matrix, induces MSC migration into the remodelling sites and couples bone formation and resorption via the canonical SMADs signalling pathway or the non‐canonical signalling pathways involving AKT, ERK1/2, FAK and p38 91. A low concentration of TGF‐β1 has the optimal effect on human umbilical cord‐derived MSC proliferation and stimulates the expression of ECM‐related genes without altering their immunophenotype and differentiation capacity, whereas pretreatment can significantly improve the survival of umbilical cord‐derived MSCs in damaged lungs in vivo 92. Preconditioning with oncostatin M (OSM), which belongs to the IL‐6 family, significantly increases the expression of type 2 OSM receptor and HGF in MSCs, consequently maintaining pulmonary respiratory function and down‐regulating the release of inflammatory and fibrotic factors in bleomycin‐induced lung fibrotic mice 93. IFN‐α‐pretreated MSCs can be used to treat dextran sodium sulphate (DSS)‐ and TNBS‐induced colitis via increasing the migration potential of MSCs and inhibiting Th1 inflammatory responses 94. Even under conditions of H/SD, pretreatment with migration inhibitory factor (MIF) significantly reduces the apoptosis rate of aged MSCs and rejuvenates the senescence by activating the AMPK‐FOXO3a signalling pathway 95. These trophic factors and growth factors may influence MSC properties synergistically or antagonistically; thus, the concentration or combination of these factors needs to be optimized according to their chemical characteristics.

Preconditioning with physical factors and materials for regulating MSC fate

Physical factors are generally noxious for MSC activities in vitro; however, an increasing number of studies have proven that they could enhance the proliferation and differentiation abilities in vitro and in vivo. Extremely low‐level lasers are effective for improving the proliferation rate via increasing the S‐phase proportion and enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis via up‐regulating the generation of ROS and NO in MSCs; moreover, the migration ability of MSCs is improved by activating the ERK1/2 and FAK signalling pathways and up‐regulating expression levels of HGF and platelet‐derived growth factor (PDGF) 96. Pretreatment with pulsed electromagnetic fields (PEMF) increases the expression levels of MSCs and decreases cell death by up‐regulating the expression of AKT and RAS in a dose‐ and time‐dependent manner 97. After suspension in culture medium, silica can be divided into NPs and MPs according to its differently sized particles, and NPs increase the proliferation of adipose‐derived MSCs via promoting phosphorylation of ERK1/2, while MPs cause a slight increase in apoptosis via increasing phosphorylation of p38 98. Intriguingly, some external elements only exert their protective effects under harmful microenvironments. For instance, mechanical stretch preconditioning increases the angiogenic capacity and survival rate of MSCs via up‐regulation of VEGFA and NF‐κB p65 activity in a condition of nutrient deprivation 73. GFc7, a nanochelating‐based nanocomplex, improves cell proliferation, expression of pluripotency genes and homing markers and antioxidative defence; spontaneous differentiation‐related genes are repressed, while specific differentiation‐related genes for the direction of the determined cell fate are significantly up‐regulated 99. Selenite recovers the osteoblastic differentiation of MSCs and inhibits the activation of the ERK signalling pathway in MSCs under the conditions of excessive H2O2 via improving the activity of glutathione peroxidase and the total antioxidant capacity and reducing glutathione for ROS generation 100. Pretreatment with carboxyl‐terminated hyperbranched polyester (CHBP) maintains the MMP and mitochondrial membrane integrity and activates the Nrf2/Sirt3/FoxO3a pathway, thus providing more resistance to starvation‐induced oxidative stress in a dose‐dependent manner, while CHBP exerts little effects on the differentiation and self‐renewal capacity of MSCs under normal conditions 101. The three‐dimensional microenvironment mimics the physical environment for MSC culture by providing intensive cell–cell interactions, providing enough space for MSC proliferation and generating more biochemical and biomechanical cues 102; thus, multiple physical factors can be applied to organization of three‐dimensional microenvironment in vitro or in vivo according to their advantages. However, the usage of physical factors and materials may effectively improve MSC‐based therapeutic effects, while it may also lead to DNA damage and apoptosis of MSCs in vitro.

Conclusions

Once MSCs are isolated from original tissues and induced to proliferate in vitro, the surrounding environment is not sufficient for maintaining their self‐renewal and differentiation capacities indefinitely. In fact, MSCs also lose a portion of their functions after isolation and cultivation in vitro as the surrounding microenvironments are changed and not the same as the environment in vivo. In addition, after they are injected in vivo and migrate into damaged tissues or organs, they encounter a harsh environment coupled with death signals due to the inadequate tensegrity structure between the cells and matrix. Consequently, although cultured MSCs are widely applied in cellular transplantation, the low survival rate and high apoptosis rate lower their therapeutic effects. Various protocols including preconditioning, gene modification and various coculture methods have been tested and widely investigated in recent studies. Preconditioning can influence the biological activities of MSCs in vitro and in vivo, thus highly improving the repairing efficacy for injury and disease models. However, there are still many obstacles to determine the optimal methods for preconditioning in MSC‐based therapy. First, will the factors exert adverse effects on MSCs? Secondly, what is the applicable dose of these factors? Thirdly, will MSCs acquire tumorigenicity after pretreatment? Fourthly, how can some factors be combined to synergistically enhance MSC activities? Fifthly, more factors that can effectively protect MSCs from apoptosis should be developed or produced. Lastly, the detailed mechanisms should be further investigated as there is not a simple regulative route to protect MSCs from injury. Although MSC transplantation has been applied to multiple clinical trials, additional studies should be conducted to more precisely understand whether and how such strategies may affect the in vivo biological activity of transplanted cells. After these potential problems that inhibit the application of preconditioning on MSCs are solved, MSC‐based therapy may be applied more widely in current regenerative medicine and can be applied for the treatment of some terminal diseases in the near future.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.: 81700553), the Stem Cell and Translational Research, the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2016YFA0101001), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2017M183789) and the Science Fund for Creative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.: 81121002).

References

- 1. Hu C, Li L. In vitro culture of isolated primary hepatocytes and stem cell‐derived hepatocyte‐like cells for liver regeneration. Protein Cell. 2015; 6: 562–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thomson JA, Itskovitz‐Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998; 282: 1145–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Young RA. Control of the embryonic stem cell state. Cell. 2011; 144: 940–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006; 126: 663–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Herberts CA, Kwa MS, Hermsen HP. Risk factors in the development of stem cell therapy. J Transl Med. 2011; 9: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Salem HK, Thiemermann C. Mesenchymal stromal cells: current understanding and clinical status. Stem Cells. 2010; 28: 585–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pessina A, Gribaldo L. The key role of adult stem cells: therapeutic perspectives. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006; 22: 2287–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ankrum JA, Ong JF, Karp JM. Mesenchymal stem cells: immune evasive, not immune privileged. Nat Biotechnol. 2014; 32: 252–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Djouad F, Bouffi C, Ghannam S, et al Mesenchymal stem cells: innovative therapeutic tools for rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009; 5: 392–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen Q, Shou P, Zheng C, et al Fate decision of mesenchymal stem cells: adipocytes or osteoblasts? Cell Death Differ. 2016; 23: 1128–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tao H, Han Z, Han ZC, et al Proangiogenic features of mesenchymal stem cells and their therapeutic applications. Stem Cells Int. 2016; 2016: 1314709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sandvig I, Gadjanski I, Vlaski‐Lafarge M, et al Strategies to enhance implantation and survival of stem cells after their injection in ischemic neural tissue. Stem Cells Dev. 2017; 26: 554–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bianco P, Cao X, Frenette PS, et al The meaning, the sense and the significance: translating the science of mesenchymal stem cells into medicine. Nat Med. 2013; 19: 35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Madrigal M, Rao KS, Riordan NH. A review of therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cell secretions and induction of secretory modification by different culture methods. J Transl Med. 2014; 12: 260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mok PL, Leong CF, Cheong SK. Cellular mechanisms of emerging applications of mesenchymal stem cells. Malays J Pathol. 2013; 35: 17–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Webster RA, Blaber SP, Herbert BR, et al The role of mesenchymal stem cells in veterinary therapeutics ‐ a review. N Z Vet J. 2012; 60: 265–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Singec I, Snyder EY. Inflammation as a matchmaker: revisiting cell fusion. Nat Cell Biol. 2008; 10: 503–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eschenhagen T, Bolli R, Braun T, et al Cardiomyocyte Regeneration: A Consensus Statement. Circulation. 2017; 136: 680–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Choi JR, Pingguan‐Murphy B, Wan Abas WA, et al In situ normoxia enhances survival and proliferation rate of human adipose tissue‐derived stromal cells without increasing the risk of tumourigenesis. PLoS ONE. 2015; 10: e0115034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Choi JR, Pingguan‐Murphy B, Wan Abas WA, et al Impact of low oxygen tension on stemness, proliferation and differentiation potential of human adipose‐derived stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014; 448: 218–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schive SW, Mirlashari MR, Hasvold G, et al Human adipose‐derived mesenchymal stem cells respond to short‐term hypoxia by secreting factors beneficial for human islets in vitro and potentiate antidiabetic effect in vivo . Cell Med. 2017; 9: 103–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Han KH, Kim AK, Kim MH, et al Enhancement of angiogenic effects by hypoxia‐preconditioned human umbilical cord‐derived mesenchymal stem cells in a mouse model of hindlimb ischemia. Cell Biol Int. 2016; 40: 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barros S, Dehez S, Arnaud E, et al Aging‐related decrease of human ASC angiogenic potential is reversed by hypoxia preconditioning through ROS production. Mol Ther. 2013; 21: 399–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Song L, Yang YJ, Dong QT, et al Atorvastatin enhance efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells treatment for swine myocardial infarction via activation of nitric oxide synthase. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e65702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Robey TE, Saiget MK, Reinecke H, et al Systems approaches to preventing transplanted cell death in cardiac repair. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008; 45: 567–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Majzunova M, Dovinova I, Barancik M, et al Redox signaling in pathophysiology of hypertension. J Biomed Sci. 2013; 20: 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chang W, Song BW, Moon JY, et al Anti‐death strategies against oxidative stress in grafted mesenchymal stem cells. Histol Histopathol. 2013; 28: 1529–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Khansari N, Shakiba Y, Mahmoudi M. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress as a major cause of age‐related diseases and cancer. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2009; 3: 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Saparov A, Ogay V, Nurgozhin T, et al Preconditioning of human mesenchymal stem cells to enhance their regulation of the immune response. Stem Cells Int. 2016; 2016: 3924858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sen S, Domingues CC, Rouphael C, et al Genetic modification of human mesenchymal stem cells helps to reduce adiposity and improve glucose tolerance in an obese diabetic mouse model. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015; 6: 242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Qazi TH, Mooney DJ, Duda GN, et al Biomaterials that promote cell‐cell interactions enhance the paracrine function of MSCs. Biomaterials. 2017; 140: 103–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brahimi‐Horn MC, Pouyssegur J. Oxygen, a source of life and stress. FEBS Lett. 2007; 581: 3582–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kheirandish M, Gavgani SP, Samiee S. The effect of hypoxia preconditioning on the neural and stemness genes expression profiling in human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells. Transfus Apher Sci. 2017; 56: 392–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim YS, Noh MY, Cho KA, et al Hypoxia/reoxygenation‐preconditioned human bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stromal cells rescue ischemic rat cortical neurons by enhancing trophic factor release. Mol Neurobiol. 2015; 52: 792–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Boyette LB, Creasey OA, Guzik L, et al Human bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells display enhanced clonogenicity but impaired differentiation with hypoxic preconditioning. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014; 3: 241–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu L, Gao J, Yuan Y, et al Hypoxia preconditioned human adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells enhance angiogenic potential via secretion of increased VEGF and bFGF. Cell Biol Int. 2013; 37: 551–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bader AM, Klose K, Bieback K, et al Hypoxic preconditioning increases survival and pro‐angiogenic capacity of human cord blood mesenchymal stromal cells in vitro . PLoS One. 2015; 10: e0138477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Estrada JC, Albo C, Benguria A, et al Culture of human mesenchymal stem cells at low oxygen tension improves growth and genetic stability by activating glycolysis. Cell Death Differ. 2012; 19: 743–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu J, Hao H, Huang H, et al Hypoxia regulates the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells through enhanced autophagy. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2015; 14: 63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sun J, Wei ZZ, Gu X, et al Intranasal delivery of hypoxia‐preconditioned bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells enhanced regenerative effects after intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke in mice. Exp Neurol. 2015; 272: 78–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yu J, Yin S, Zhang W, et al Hypoxia preconditioned bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells promote liver regeneration in a rat massive hepatectomy model. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013; 4: 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chang CP, Chio CC, Cheong CU, et al Hypoxic preconditioning enhances the therapeutic potential of the secretome from cultured human mesenchymal stem cells in experimental traumatic brain injury. Clin Sci (Lond). 2013; 124: 165–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wei L, Fraser JL, Lu ZY, et al Transplantation of hypoxia preconditioned bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells enhances angiogenesis and neurogenesis after cerebral ischemia in rats. Neurobiol Dis. 2012; 46: 635–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hu X, Xu Y, Zhong Z, et al A large‐scale investigation of hypoxia‐preconditioned allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells for myocardial repair in nonhuman primates: paracrine activity without remuscularization. Circ Res. 2016; 118: 970–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang X, Liu C, Li S, et al Hypoxia precondition promotes adipose‐derived mesenchymal stem cells based repair of diabetic erectile dysfunction via augmenting angiogenesis and neuroprotection. PLoS One. 2015; 10: e0118951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cruz FF, Rocco PR. Hypoxic preconditioning enhances mesenchymal stromal cell lung repair capacity. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015; 6: 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Feng Y, Zhu M, Dangelmajer S, et al Hypoxia‐cultured human adipose‐derived mesenchymal stem cells are non‐oncogenic and have enhanced viability, motility, and tropism to brain cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2015; 6: e1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lee JH, Yoon YM, Lee SH. Hypoxic preconditioning promotes the bioactivities of mesenchymal stem cells via the HIF‐1alpha‐GRP78‐Akt Axis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017; 18: pii: E1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Han YS, Lee JH, Yoon YM, et al Hypoxia‐induced expression of cellular prion protein improves the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 2016; 7: e2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fan L, Zhang C, Yu Z, et al Transplantation of hypoxia preconditioned bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells enhances angiogenesis and osteogenesis in rabbit femoral head osteonecrosis. Bone. 2015; 81: 544–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Liu J, Hao H, Xia L, et al Hypoxia pretreatment of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells facilitates angiogenesis by improving the function of endothelial cells in diabetic rats with lower ischemia. PLoS One. 2015; 10: e0126715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hu L, Wen Y, Xu J, et al Pretreatment with bisphosphonate enhances osteogenesis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2017; 26: 123–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ferrer RA, Wobus M, List C, et al Mesenchymal stromal cells from patients with myelodysplastic syndrome display distinct functional alterations that are modulated by lenalidomide. Haematologica. 2013; 98: 1677–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bhatti FU, Mehmood A, Latief N, et al Vitamin E protects rat mesenchymal stem cells against hydrogen peroxide‐induced oxidative stress in vitro and improves their therapeutic potential in surgically‐induced rat model of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017; 25: 321–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang J, Li Z, Zhang Y, et al CX43 change in LPS preconditioning against apoptosis of mesenchymal stem cells induced by hypoxia and serum deprivation is associated with ERK signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013; 380: 267–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sun X, Fang B, Zhao X, et al Preconditioning of mesenchymal stem cells by sevoflurane to improve their therapeutic potential. PLoS One. 2014; 9: e90667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. An SY, Han J, Lim HJ, et al Valproic acid promotes differentiation of hepatocyte‐like cells from whole human umbilical cord‐derived mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Cell. 2014; 46: 127–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Li M, Yu L, She T, et al Astragaloside IV attenuates Toll‐like receptor 4 expression via NF‐kappaB pathway under high glucose condition in mesenchymal stem cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012; 696: 203–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lee J, Shin MS, Kim MO, et al Apple ethanol extract promotes proliferation of human adult stem cells, which involves the regenerative potential of stem cells. Nutr Res. 2016; 36: 925–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Luo G, Xu B, Huang Y. Icariside II promotes the osteogenic differentiation of canine bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR/S6K1 signaling pathways. Am J Transl Res. 2017; 9: 2077–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhang LY, Xue HG, Chen JY, et al Genistein induces adipogenic differentiation in human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and suppresses their osteogenic potential by upregulating PPARgamma. Exp Ther Med. 2016; 11: 1853–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Noiseux N, Borie M, Desnoyers A, et al Preconditioning of stem cells by oxytocin to improve their therapeutic potential. Endocrinology. 2012; 153: 5361–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Najafi R, Sharifi AM. Deferoxamine preconditioning potentiates mesenchymal stem cell homing in vitro and in streptozotocin‐diabetic rats. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2013; 13: 959–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Khan I, Ali A, Akhter MA, et al Preconditioning of mesenchymal stem cells with 2,4‐dinitrophenol improves cardiac function in infarcted rats. Life Sci. 2016; 162: 60–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Liu C, Fan Y, Zhou L, et al Pretreatment of mesenchymal stem cells with angiotensin II enhances paracrine effects, angiogenesis, gap junction formation and therapeutic efficacy for myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2015; 188: 22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Numasawa Y, Kimura T, Miyoshi S, et al Treatment of human mesenchymal stem cells with angiotensin receptor blocker improved efficiency of cardiomyogenic transdifferentiation and improved cardiac function via angiogenesis. Stem Cells. 2011; 29: 1405–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kim YS, Kwon JS, Hong MH, et al Restoration of angiogenic capacity of diabetes‐insulted mesenchymal stem cells by oxytocin. BMC Cell Biol. 2013; 14: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jeong SG, Ohn T, Kim SH, et al Valproic acid promotes neuronal differentiation by induction of neuroprogenitors in human bone‐marrow mesenchymal stromal cells. Neurosci Lett. 2013; 554: 22–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tang Y, Cai B, Yuan F, et al Melatonin pretreatment improves the survival and function of transplanted mesenchymal stem cells after focal cerebral ischemia. Cell Transplant. 2014; 23: 1279–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wan Y, Zhuo N, Li Y, et al Autophagy promotes osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell derived from osteoporotic vertebrae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017; 488: 46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pourjafar M, Saidijam M, Mansouri K, et al All‐trans retinoic acid preconditioning enhances proliferation, angiogenesis and migration of mesenchymal stem cell in vitro and enhances wound repair in vivo . Cell Prolif. 2017; 50: e12315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Qiu Y, Guo J, Mao R, et al TLR3 preconditioning enhances the therapeutic efficacy of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells in TNBS‐induced colitis via the TLR3‐Jagged‐1‐Notch‐1 pathway. Mucosal Immunol. 2017; 10: 727–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zhu Z, Gan X, Fan H, et al Mechanical stretch endows mesenchymal stem cells stronger angiogenic and anti‐apoptotic capacities via NFkappaB activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015; 468: 601–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Yang Y, Choi H, Seon M, et al LL‐37 stimulates the functions of adipose‐derived stromal/stem cells via early growth response 1 and the MAPK pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016; 7: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ge T, Yu Q, Liu W, et al Characterization of bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells from dimethyloxallyl glycine‐preconditioned mice: evaluation of the feasibility of dimethyloxallyl glycine as a mobilization agent. Mol Med Rep. 2016; 13: 3498–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Liu XB, Wang JA, Ji XY, et al Preconditioning of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by prolyl hydroxylase inhibition enhances cell survival and angiogenesis in vitro and after transplantation into the ischemic heart of rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014; 5: 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Yu Y, Wei N, Stanford C, et al In vitro effects of RU486 on proliferation and differentiation capabilities of human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells. Steroids. 2012; 77: 132–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ma Q, Xia X, Tao Q, et al Profound actions of an agonist of growth hormone‐releasing hormone on angiogenic therapy by mesenchymal stem cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016; 36: 663–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Bernardo ME, Fibbe WE. Mesenchymal stromal cells: sensors and switchers of inflammation. Cell Stem Cell. 2013; 13: 392–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Keating A. Mesenchymal stromal cells: new directions. Cell Stem Cell. 2012; 10: 709–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Liu X, Duan B, Cheng Z, et al SDF‐1/CXCR4 axis modulates bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell apoptosis, migration and cytokine secretion. Protein Cell. 2011; 2: 845–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. van Zoelen EJ, Duarte I, Hendriks JM, et al TGFbeta‐induced switch from adipogenic to osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells: identification of drug targets for prevention of fat cell differentiation. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016; 7: 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Lu Z, Wang G, Dunstan CR, et al Activation and promotion of adipose stem cells by tumour necrosis factor‐alpha preconditioning for bone regeneration. J Cell Physiol. 2013; 228: 1737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Noone C, Kihm A, English K, et al IFN‐gamma stimulated human umbilical‐tissue‐derived cells potently suppress NK activation and resist NK‐mediated cytotoxicity in vitro . Stem Cells Dev. 2013; 22: 3003–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Sullivan CB, Porter RM, Evans CH, et al TNFalpha and IL‐1beta influence the differentiation and migration of murine MSCs independently of the NF‐kappaB pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014; 5: 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Martino MM, Maruyama K, Kuhn GA, et al Inhibition of IL‐1R1/MyD88 signalling promotes mesenchymal stem cell‐driven tissue regeneration. Nat Commun. 2016; 7: 11051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Francois M, Romieu‐Mourez R, Li M, et al Human MSC suppression correlates with cytokine induction of indoleamine 2,3‐dioxygenase and bystander M2 macrophage differentiation. Mol Ther. 2012; 20: 187–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Parivar K, Baharara J, Sheikholeslami A. Neural differentiation of mouse bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells treated with sex steroid hormones and basic fibroblast growth factor. Cell J. 2015; 17: 27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Carrero R, Cerrada I, Lledo E, et al IL1beta induces mesenchymal stem cells migration and leucocyte chemotaxis through NF‐kappaB. Stem Cell Rev. 2012; 8: 905–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Matsumura E, Tsuji K, Komori K, et al Pretreatment with IL‐1beta enhances proliferation and chondrogenic potential of synovium‐derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cytotherapy. 2017; 19: 181–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Dubon MJ, Yu J, Choi S, et al Transforming growth factor beta induces bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell migration via noncanonical signals and N‐cadherin. J Cell Physiol. 2017; 233: 201–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Li D, Liu Q, Qi L, et al Low levels of TGF‐beta1 enhance human umbilical cord‐derived mesenchymal stem cell fibronectin production and extend survival time in a rat model of lipopolysaccharide‐induced acute lung injury. Mol Med Rep. 2016; 14: 1681–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Lan YW, Theng SM, Huang TT, et al Oncostatin M‐preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells alleviate bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis through paracrine effects of the hepatocyte growth factor. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017; 6: 1006–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Duijvestein M, Wildenberg ME, Welling MM, et al Pretreatment with interferon‐gamma enhances the therapeutic activity of mesenchymal stromal cells in animal models of colitis. Stem Cells. 2011; 29: 1549–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Xia W, Zhang F, Xie C, et al Macrophage migration inhibitory factor confers resistance to senescence through CD74‐dependent AMPK‐FOXO3a signaling in mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015; 6: 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Yin K, Zhu R, Wang S, et al Low‐level laser effect on proliferation, migration, and antiapoptosis of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2017; 26: 762–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Urnukhsaikhan E, Cho H, Mishig‐Ochir T, et al Pulsed electromagnetic fields promote survival and neuronal differentiation of human BM‐MSCs. Life Sci. 2016; 151: 130–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Kim KJ, Joe YA, Kim MK, et al Silica nanoparticles increase human adipose tissue‐derived stem cell proliferation through ERK1/2 activation. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015; 10: 2261–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Hafizi M, Hajarizadeh A, Atashi A, et al Nanochelating based nanocomplex, GFc7, improves quality and quantity of human mesenchymal stem cells during in vitro expansion. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015; 6: 226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Liu H, Bian W, Liu S, et al Selenium protects bone marrow stromal cells against hydrogen peroxide‐induced inhibition of osteoblastic differentiation by suppressing oxidative stress and ERK signaling pathway. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2012; 150: 441–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Wang S, Zhang C, Niyazi S, et al A novel cytoprotective peptide protects mesenchymal stem cells against mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis induced by starvation via Nrf2/Sirt3/FoxO3a pathway. J Transl Med. 2017; 15: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Sart S, Agathos SN, Li Y, et al Regulation of mesenchymal stem cell 3D microenvironment: from macro to microfluidic bioreactors. Biotechnol J. 2016; 11: 43–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]