Abstract

Purpose of Review

A subset of patients being treated for hypothyroidism do not feel well taking levothyroxine replacement therapy, despite having a normal TSH. Pursuing a relative triiodothyronine deficiency as a potential explanation for patient dissatisfaction, has led to trials of combination therapy with liothyronine, with largely negative outcomes. This review attempts to reconcile these diverse findings, consider potential explanations, and identify areas for future research.

Recent Findings

Patients being treated with levothyroxine often have lower triiodothyronine levels than patients with endogenous thyroid function. Linking patient dissatisfaction with low triiodothyronine levels has fueled multiple combination therapy trials that have generally not shown improvement in patient quality of life, mood, or cognitive performance. Some trials, however, suggest patient preference for combination therapy. There continues, moreover, to be anecdotal evidence that patients have fewer unresolved symptoms while taking combination therapy.

Summary

The fourteen trials completed to date have suffered from employing doses of liothyronine that do not result in steady triiodothyronine levels, and having insufficient power to analyze results based on baseline dissatisfaction with therapy and patient genotype. Future trials that are able to incorporated such features may provide insight to what thyroid hormone preparations will most improve patient satisfaction with therapy.

Keywords: Hypothyroidism, quality of life, euthyroidism, levothyroxine, combination therapy

Introduction

As in most cases hypothyroidism is a permanent condition, affected patients rely on life-long replacement therapy. For many patients such therapy, usually provided as synthetic levothyroxine (LT4), is entirely satisfactory and fully resolves the symptoms of untreated hypothyroidism (1). However, some patients do not feel that they are returned to full health, and note decreased quality of life, often dating from their diagnosis of hypothyroidism. Some patients may feel better while taking combination therapy consisting of both LT4 and liothyronine (LT3). However, for some other patients, combination therapy does not provide the solution. A description of such an unhappy patient is provided in table 1. After summarizing the data regarding patient-reported dissatisfaction, this review describes the evidence suggesting that LT4 therapy may not replicate normal physiology. The significance of circulating total and free triiodothyronine (T3 and FT3) has been a source of contention, and this issue is discussed. This review also outlines the results of combination therapy trials that have been conducted thus far. Alternative explanation for unresolved symptoms are explored. Finally, areas where new research is needed are identified.

Table 1.

Patient Case

| HISTORY PROVIDED BY PATIENT | • Progressive weight gain | • Fatigue throughout day | • Poor memory affecting family life and work performance |

| PHYSICAL EXAMINATION | • No palpable tissue in thyroid bed | • No cervical lympadenopathy | • Otherwise normal examination findings |

| MEDICAL HISTORY | • Thyroidectomy for thyroid cancer | • No other medical conditions | • Takes thyroid hormone as prescribed |

| LABORATORY ASSESSMENT | • TSH 0.3 mIU/L (normal 0.4-4) | • FT4 1.5 ng/dL (normal 0.7-1.7) | • T3 90 ng/dL (normal 80-180) |

| OUTCOME | • Seen by 5 different physicians | • Trips out of state for additional consultations | • Symptoms persist when switched to combination therapy |

Patient-reported Outcomes during Levothyroxine Therapy

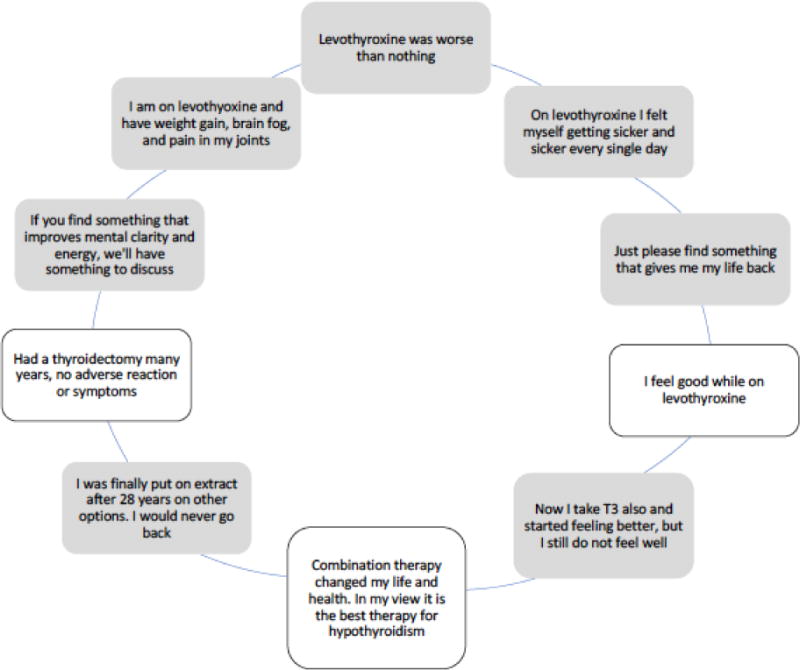

Patient quality of life can be reported using questionnaires that can be administered online, in written form, or during an interview. Some questionnaires assess general measures, while others assess measures that are specific to particular diseases, such as thyroid disease. Several questionnaires specific to thyroid disorders were recently evaluated and four related to hypothyroidism and benign thyroid disease were studied (2). The highest quality instruments for assessing symptoms in patients with hypothyroidism were found, in this recent metaanalysis (2), to be the Thyroid-Specific Patient-Reported Outcomes Measure (ThyPRO) (3, 4) and Thyroid Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (5, 6). Many patients report that LT4 provides satisfactory therapy for their hypothyroidism. However, this is not universally the case. In a study from the United Kingdom, 40.3% of treated patients had symptoms of hypothyroidism, compared with 24.9% of a control population using a Thyroid Symptom Questionnaire score of greater than 4 as a measure of dissatisfaction with therapy (7). Another study, in which participants taking LT4 were recruited by letter and then completed questionnaires assessing well-being, also showed lower scores in 2 different questionnaires in the euthyroid patients taking L-T4, although the comparison was with standard reference values, rather than a matched control group (8). In several more recent studies, treated female patients with hypothyroidism were found to have worse quality of life compared with control groups using the RAND-36 Short Form Survey Instrument (SF-36) (9), the ThyPRO and SF-36 questionnaires (10), the SF-36, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and the multidimensional fatigue inventory questionnaire (11), and worse mental health using the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) (12). One of these studies, which examined patients before and after initiation of LT4, showed improvement in some ThyPRO and SF-36 subscales as serum TSH was normalized from a median of 8.1 to 2.6 mIU/L. However, persistent deficits were noted in other subscales despite treatment. Sample patient comments regarding their therapy for hypothyroidism gathered during an online patient survey hosted on 2 patient advocate websites in 2016 are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Selected Patient-reported Symptoms from an Online Questionnaire

Comparison of Euthyroid Physiology with Physiology during Levothyroxine Treatment

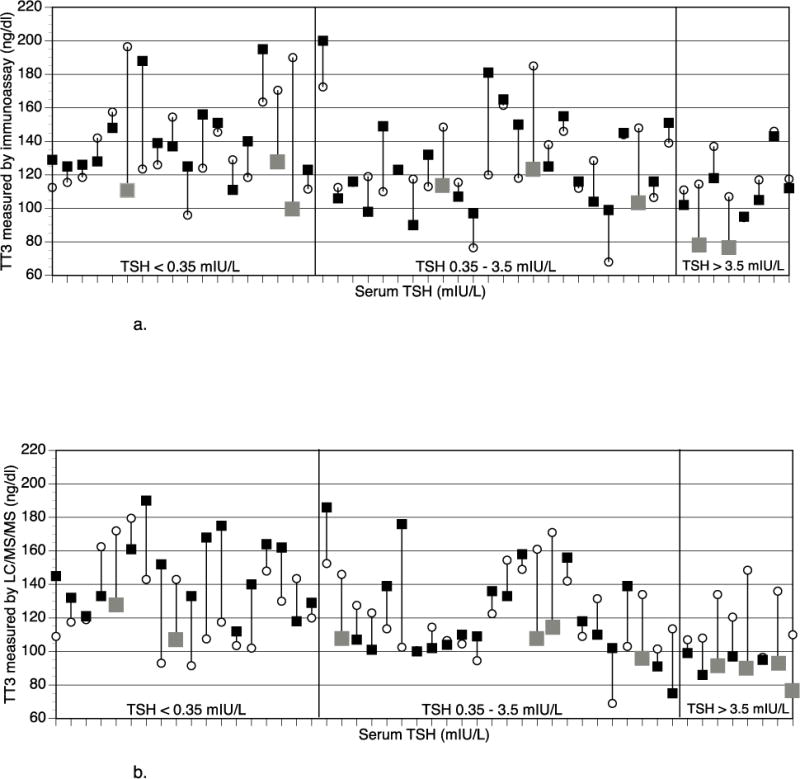

It has been well-established that individuals receiving LT4 therapy have higher serum levels of total thyroxine (T4) and free thyroxine (FT4) than endogenously euthyroid individuals, and that they therefore also have higher T4/T3 or FT4/FT3 ratios (13–16). Of the recent trials using current assay methodology for measuring T3 and FT3, the majority show that the concentrations of these analytes are lower in patients taking LT4 than in euthyroid controls (14–16). Furthermore, these trials suggest that LT4 therapy needs to be provided at doses that lower TSH levels in order to achieve a FT3 in the normal range. These trials, however, were retrospective (14–16) and/or did not use each patient as their own control (14, 16). One trial, in which patients were studied pre-thyroidectomy and post-thyroidectomy, showed maintenance of T3 levels, based on the average T3 levels (13). However, 8 of the 50 individual patients (16%) did have lower T3 levels when being treated with LT4 (see figure 2). There appeared to be a trend for lower T3 levels during LT4 therapy to be associated with higher TSH values when T3 was measured by tandem mass spectrometry, but not when an immunoassay was used.

Fig 2.

a: Mean T3 with native functioning (open circles) and T3 after LT4 dose adjustment after thyroidectomy (closed squares, with grey squares indicating >30 ng/dL lowering of T3 value) plotted as a parallel line for individual patients, grouped by TSH values on LT4

T3 measured by immunoassay

b: Mean T3 with native functioning (open circles) and T3 after LT4 dose adjustment after thyroidectomy (closed squares, with grey squares indicating >30 ng/dL lowering of T3 value) plotted as a parallel line for individual patients, grouped by TSH values on LT4

T3 measured by tandem mass spectrometry

Although sex hormone-binding globulin, cholesterol levels, and bone markers are generally considered to be relatively insensitive measures of thyroid status compared with TSH levels, a recent study comparing these measures in patients pre-thyroidectomy and post-thyroidectomy showed that these measures were best normalized in patients with mildly suppressed TSH values in the range of <0.03-≤0.3 mIU/L (17). If confirmed, this could suggest that TSH alone may not provide sufficient insight into thyroid status.

Significance of Circulating Triiodothyronine Concentrations

The concept of LT4 as a prohormone, with each tissue being able to convert FT4 to FT3 as needed, is physiologically appealing. If thyroid hormone is supplied as LT3 monotherapy this may be non-physiologic, as it is possible that individual tissues and cells might be forced to accept a specific amount of FT3, regardless of their individual needs. There has been recent debate as to whether the T3 levels achieved during treatment of hypothyroidism are important (18). Traditionally thyroid status in patients being treated for hypothyroidism with LT4 has been monitored using serum TSH, and potentially also FT4, concentrations (1). The “choosing wisely” initiative of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, supported by several endocrine societies, recommends against considering T3 levels when adjusting LT4 therapy (19). However, the hypothesis that sub-normal T3 levels are both prevalent and important has fueled the 14 or so trials of combination therapy with both T4 and T3 that have been conducted thus far.

All trials of combination therapy have used LT3 given as either a once or twice daily dose. An animal study suggesting that such periodic delivery may also be non-physiologic was recently conducted (20). Rodents were treated with either continuous LT4 alone, or continuous LT4 and periodic LT3 injections, or continuous delivery of both T4 and T3 via subcutaneously implanted pellets. In this study, the T4 and T3 levels seen in euthyroid control animals was only recapitulated by subcutaneous pellets which continuously supplied T4 and T3. The authors suggested that during T4 monotherapy the hypothalamus exhibits less inactivation of the type 2 deiodinase than other tissues, and therefore produces T3 more efficiently than other tissues (20). Thus, it was hypothesized, that TSH secretion is normalized before T3 levels are fully normalized in other tissues, resulting in low T3 levels in many peripheral tissues. Furthermore, markers of euthyroidism, such as mitochondrial and α-glycerolphosphate dehydrogenase content of liver and muscle and serum cholesterol levels, better approximated values in control animals when sustained delivery of both T4 and T3 was employed (20).

A recent cross-sectional study using data from the 2001-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey compared biochemical data and clinical data from healthy euthyroid participants to euthyroid LT4-treated participants (21). The LT4-treated group had lower serum T3 and FT3 concentrations. They were also more frequently treated with statins and antidepressants, and had a higher body mass index (BMI). However, in multivariate analysis there was no association between serum T3 concentrations and any of the clinical parameters assessed, except for age and sex. These data suggest that although serum T3 levels are lower in LT4-patient than in euthyroid controls, the physical and psychologic morbidity associated with receiving LT4 treatment for hypothyroidism may not be directly linked to the T3 levels achieved by their therapy.

Summary of Combination Therapy Trials

Stimulated by the knowledge that the native thyroid gland directly produces T3, and the finding that some individuals being treated for hypothyroidism may have low T3 levels, fourteen trials comparing combination therapy with LT4 and LT3 to monotherapy with LT4 have been conducted (22–35) [reviewed in (1)]. Despite this extensive body of evidence, clear benefit from combination therapy has not yet been shown. These trials have not shown improvement in a variety of outcome measures with the use of combination therapy. For example, thyroid-related symptoms were not different between treatment groups, and body weight was not lower during combination therapy, except in one study (22) using a combination therapy dose that suppressed serum TSH. Health-related quality of life or mood was not improved in the majority of trials, although 2 trials showed improvement in a few measures (31, 34), and 2 trials showed improvement in a majority of measures (24, 29). Similarly, with neurocognitive function, most trials showed no improvement, one trial showed improvement in a few measures (26), and one trial showed improvement in several measures (24). A preference for synthetic combination therapy was seen in 4 out the 5 crossover trials in which preference was assessed (23, 24, 26, 29). Patients preferred combination therapy in one of the trials with a parallel design (22). However, the largest trial, which had a parallel design, was not associated with patient preference for combination therapy (31).

However, there are some limitations to these trials (1). Most of these trials had fewer than 100 patients. The length of the trials has been short, with most being 5-16 weeks in duration. Only four of the trials were 4-12 months long. Another concern with these trials is the frequency of LT3 dosing. When LT3 is given once daily, steady serum levels of T3 are not maintained (36), although they are maintained with three times a day dosing (37). There were 9 trials that used once daily LT3 dosing (23, 24, 26–31, 33), 4 trials that employed twice daily LT3 dosing (22, 25, 32, 34), and none that used LT3 given three times daily. Some studies resulted in different TSH concentrations between groups, potentially confounding the study results, or reducing the ability to demonstrate differences between the groups. The predominance of healthy middle-aged females in the current studies leads to potential problems with generalizing results to the entire hypothyroid population, including the elderly, males, and those with comorbidities. The heterogeneity of the trials makes it difficult to assess outcomes with the use of meta-analyses (38–40).

The type 2 deiodinase enzyme is responsible for converting T4 to T3 in the thyroid gland, brain, pituitary, skeletal muscle, and heart (1). There has been interest in potential consequences of polymorphisms in the type 2 deiodinase gene, including the Thr92Ala polymorphism (1). This polymorphism may possibly affect enzymatic function (41) and be associated with genes involved in oxidative stress in brain tissue (42). Approximately 10-16% of the population are homozygous for this substitution. A secondary analysis of the largest combination therapy trial suggested that patients with a particular genetic variation, the Thr92Ala variant of the type 2 deiodinase responded differently to combination therapy (43). Not only did these individuals have worse scores on the general health questionnaire while taking LT4, but they also had a better response to combination therapy in which 50 mcg LT4 was replaced by 10 mcg LT3. As this study was retrospective in nature and the authors did not have a sufficient sample size to correct for multiple comparisons, a well-powered prospective study is still awaited. A recent study of quality of life in the general population and in individuals being treated for hypothyroidism examined the association of this polymorphism with impaired quality of life. No association was found in either population, although the study may have been underpowered. It is possible that if patients with this particular variant are specifically targeted in future combination therapy trials, a greater benefit of combination therapy might be documented.

Possible Explanation for Unresolved Symptoms

A recent study has shown that although quality of life does improve after patients with hypothyroidism are rendered euthyroid with LT4, these individuals still have residual impairment in health-related quality of life as assessed using the ThyPRO and SF-36 questionnaires, using normative data as the comparator (10). There are many factors that contribute to health-related quality of life. These include physical factors, psychological factors, social factors, economic factors, disease symptoms, cultural set-up, activities of daily role, and treatment (44). The decreased quality of life in biochemically euthyroid patients with hypothyroidism could have several potential causes from among these factors, with treatment for their disease perhaps not being the only relevant factor. For example, with respect to physical factors, impaired quality of life has been found to be associated with increased BMI in patients being treated for hypothyroidism (11), suggesting the importance of considering BMI as a possible contributant to quality of life. Certainly, preference for combination therapy has been associated with weight loss achieved during therapy in both a trial of synthetic combination therapy (22) and in a trial of desiccated thyroid extract (45).

Alternatively, there may be an ascertainment bias because patients who do not feel well are be more likely to be screened for and diagnosed with hypothyroidism (see table 2). For example, in one study individuals with psychological stress were more likely to be referred for screening for hypothyroidism, but were no more likely to actually have hypothyroidism than the general population (46). Being categorized as having a chronic condition could also prove detrimental to a patient’s well-being. Some support for this particular explanation is provided by a study showing that being aware of diagnoses such as diabetes, hypertension, and hypothyroidism were linked with worse self-reported health (47). Many patients with hypothyroidism may also have other chronic conditions, and there may be overlap in the symptoms associated with these conditions. For example, rheumatologic disorders may be associated with similar symptoms such as fatigue, waking up unrefreshed, and trouble thinking or remembering (48), and some tools designed to detect systemic autoimmune rheumatologic disease may have moderate validity for detecting thyroid disease also (49). Some studies also suggest that individuals with hypothyroidism are more likely to be diagnosed with disorders such as anxiety and depression (50).

Table 2.

Potential Reasons for Residual Symptoms in Patients Treated for Hypothyroidism to Achieve a Normal TSH

| POTENTIAL REASONS | FURTHER EXPLANATION |

|---|---|

| Ascertainment bias | Patients with symptoms may be more likely to be screened for hypothyroidism |

| Inadequate therapy | LT4 may not reverse hypothyroidism in all tissues |

| Inadequate biomarker | TSH may not be the best biomarker for judging adequacy of LT4 replacement |

| Genetic susceptibility | Common polymorphisms in the deiodinase or thyroid hormone transporter genes may be associated in impaired quality of life while taking LT4 and also be associated with better response to combination therapy |

| Detrimental effect of autoimmunity | Thyroid peroxidase antibodies, or other autoantibodies, may have an adverse effect on quality of life independent of triggering hypothyroidism |

| Multiple factors influencing quality of life | Other factor(s) may be contributing to, or be responsible for, impaired quality of life |

| Coexistent chronic disease | Other chronic medical conditions may be prevalent in individuals with hypothyroidism and may contribute to impaired quality of life |

| Coexistent psychiatric disease | Psychiatric conditions may be prevalent in individuals with hypothyroidism and may contribute to impaired quality of life |

On the other hand, it is possible that there is some aspect of the hypothyroid state, which is difficult to measure or capture in survey instruments, that is not adequately reversed with LT4 monotherapy. It is also possible that Hashimoto’s hypothyroidism may cause morbidity that is specifically related to the underlying autoimmunity, rather than the thyroid status (51, 52). Finally, variations in genes associated with thyroid hormone metabolism and action could be associated with an inferior response to LT4 (43), or could be associated with other conditions that affect quality of life (42).

Potential Directions for Future Research

With regard to future research into why some patients with hypothyroidism continue to have unresolved symptoms, there is still a possibility that future trials of combination therapy will provide answers. Future trials may need to study larger numbers of patients, while also ensuring serum TSH values are not different in the treatment groups, and employing standardized outcomes and validated measures of quality of life. Larger sample sizes would not only allow for more power to detect differences between groups, but would also allow detection of differences in analyses stratified by baseline symptoms. In addition, future trials may benefit from focusing on particular subgroup of patients, such as those who do not feel well, those with type 2 deiodinase polymorphisms or other genetic variations, athyreotic patients, or those have particularly low serum T3 levels during monotherapy. The population studied should also include those with other medical conditions to ensure those studied are representative of the general population with hypothyroidism. Other considerations in future trials would be using more frequent administration of LT3 in order to achieve more stable serum T3 concentrations. Three times daily LT3 therapy (as monotherapy) has been successfully achieved (37), but such frequent medication administration is challenging to maintain during long-term therapy. A sustained release T3 preparation would clearly circumvent this issue.

Conclusion

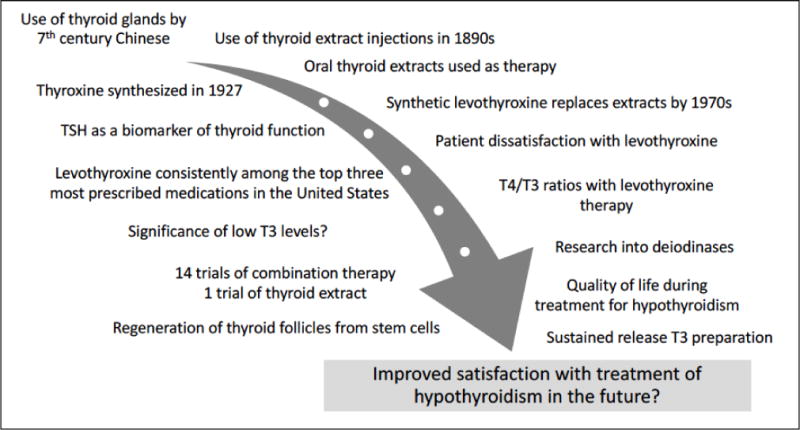

Levothyroxine is easy to administer and monitor, and results in excellent quality of life for most patients. Thus, clinicians have the opportunity to prescribe an excellent therapy that rapidly and effectively reverses the stigmata of hypothyroidism. This is indeed a significant advance since hypothyroidism was treated by grafting half a sheep’s thyroid gland into a myxedematous patient. However, despite the successes in treating hypothyroidism, there are clearly aspects of treating hypothyroidism that are not yet understood (see figure 3). There is a need to fine-tune thyroid hormone replacement so that it provides satisfactory treatment to all those affected by hypothyroidism. Development of a sustained release T3 preparation and harnessing thyroid follicles generated from stem cells are potential avenues through which this might be achieved.

Figure 3.

Past and Future Progress into the Treatment of Hypothyroidism

Key points.

Patient-reported outcomes indicate impaired quality of life in some patients treated for hypothyroidism

Patients receiving levothyroxine therapy have higher T4/T3 ratios than euthyroid controls, and may also have lower T3 concentrations

Trials of combination therapy with LT3 have failed to show clear superiority of combination therapy

There are multiple factors that could potentially contribute to impaired quality of life in patient receiving LT4 therapy

A large combination therapy trial with LT3 administered three times daily, targeting those who do not feel well taking LT4, and stratifying results by genotype may provide answers regarding how to optimize therapy for hypothyroidism

Acknowledgments

None

Financial support and sponsorship

J.J. is supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01AG033867, R01DE025822 and UL1TR001409.

Financial support: None

Abbreviations

- LT4

levothyroxine

- LT3

liothyronine

- T3

total triiodothyronine

- FT3

free triiodothyronine

- ThyPRO

Thyroid-Specific Patient-Reported Outcomes Measure

- SF-36

Short Form Survey Instrument

- GHQ

General Health Questionnaire

- T4

total thyroxine

- FT4

free thyroxine

- BMI

body mass index

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, Burman KD, Cappola AR, Celi FS, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: prepared by the american thyroid association task force on thyroid hormone replacement. Thyroid. 2014;24(12):1670–751. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2**.Wong CK, Lang BH, Lam CL. A systematic review of quality of thyroid-specific health-related quality-of-life instruments recommends ThyPRO for patients with benign thyroid diseases. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;78:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.03.006. This study analyzes the performance of thyroid-related quality of life instruments and recommends the use of ThyPRO and TSQ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watt T, Hegedus L, Groenvold M, Bjorner JB, Rasmussen AK, Bonnema SJ, et al. Validity and reliability of the novel thyroid-specific quality of life questionnaire, ThyPRO. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162(1):161–7. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watt T, Bjorner JB, Groenvold M, Rasmussen AK, Bonnema SJ, Hegedus L, et al. Establishing construct validity for the thyroid-specific patient reported outcome measure (ThyPRO): an initial examination. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(4):483–96. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMillan CV, Bradley C, Woodcock A, Razvi S, Weaver JU. Design of new questionnaires to measure quality of life and treatment satisfaction in hypothyroidism. Thyroid. 2004;14(11):916–25. doi: 10.1089/thy.2004.14.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMillan C, Bradley C, Razvi S, Weaver J. Evaluation of new measures of the impact of hypothyroidism on quality of life and symptoms: the ThyDQoL and ThySRQ. Value Health. 2008;11(2):285–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saravanan P, Chau WF, Roberts N, Vedhara K, Greenwood R, Dayan CM. Psychological well-being in patients on ‘adequate’ doses of l-thyroxine: results of a large, controlled community-based questionnaire study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002;57(5):577–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wekking EM, Appelhof BC, Fliers E, Schene AH, Huyser J, Tijssen JG, et al. Cognitive functioning and well-being in euthyroid patients on thyroxine replacement therapy for primary hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;153(6):747–53. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9**.Wouters HJ, van Loon HC, van der Klauw MM, Elderson MF, Slagter SN, Kobold AM, et al. No Effect of the Thr92Ala Polymorphism of Deiodinase-2 on Thyroid Hormone Parameters, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Cognitive Functioning in a Large Population-Based Cohort Study. Thyroid. 2017;27(2):147–55. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0199. This study showed that female patients taking LT4 had lower health-related quality of life than non-LT4 users. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10**.Winther KH, Cramon P, Watt T, Bjorner JB, Ekholm O, Feldt-Rasmussen U, et al. Disease-Specific as Well as Generic Quality of Life Is Widely Impacted in Autoimmune Hypothyroidism and Improves during the First Six Months of Levothyroxine Therapy. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156925. This study demonstrates that quality of life improves with implementation of treatment for hypothyroidism, but does not fully normalize. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelderman-Bolk N, Visser TJ, Tijssen JP, Berghout A. Quality of life in patients with primary hypothyroidism related to BMI. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173(4):507–15. doi: 10.1530/EJE-15-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12*.Rakhshan M, Ghanbari A, Rahimi A, Mostafavi A Comparison between the Quality of Life and Mental Health of Patients with Hypothyroidism and Normal People Referred to Motahari Clinic of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. IJCBNM. 2017;5(1):30–7. This study shows impaired quality of life in individuals being treated with LT4, compared with a control population. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonklaas J, Davidson B, Bhagat S, Soldin SJ. Triiodothyronine levels in athyreotic individuals during levothyroxine therapy. JAMA. 2008;299(7):769–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.7.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gullo D, Latina A, Frasca F, Le Moli R, Pellegriti G, Vigneri R. Levothyroxine monotherapy cannot guarantee euthyroidism in all athyreotic patients. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e22552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito M, Miyauchi A, Morita S, Kudo T, Nishihara E, Kihara M, et al. TSH-suppressive doses of levothyroxine are required to achieve preoperative native serum triiodothyronine levels in patients who have undergone total thyroidectomy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;167(3):373–8. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alevizaki M, Mantzou E, Cimponeriu AT, Alevizaki CC, Koutras DA. TSH may not be a good marker for adequate thyroid hormone replacement therapy. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2005;117(18):636–40. doi: 10.1007/s00508-005-0421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17**.Ito M, Miyauchi A, Hisakado M, Yoshioka W, Ide A, Kudo T, et al. Biochemical Markers Reflecting Thyroid Function in Athyreotic Patients on Levothyroxine Monotherapy. Thyroid. 2017;27(4):484–90. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0426. This analysis shows that despite normalization of TSH, other biochemical markers of thyroid status do not normalize with LT4 treatment. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdalla SM, Bianco AC. Defending plasma T3 is a biological priority. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014;81(5):633–41. doi: 10.1111/cen.12538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Don’t order a total or free T3 level when assessing levothyroxine (T4) dose in hypothyroid patients. Released October 16, 2013 [Available from: http://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/

- 20.Werneck de Castro JP, Fonseca TL, Ueta CB, McAninch EA, Abdalla S, Wittmann G, et al. Differences in hypothalamic type 2 deiodinase ubiquitination explain localized sensitivity to thyroxine. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(2):769–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI77588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21**.Peterson SJ, McAninch EA, Bianco AC. Is a Normal TSH Synonymous With “Euthyroidism” in Levothyroxine Monotherapy? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(12):4964–73. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2660. This cross-sectional study shows that T3 levels are lower in individuals being treated for hypothyroidism, but that T3 levels do not correlate with other clinical parameters. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Appelhof BC, Fliers E, Wekking EM, Schene AH, Huyser J, Tijssen JG, et al. Combined therapy with levothyroxine and liothyronine in two ratios, compared with levothyroxine monotherapy in primary hypothyroidism: a double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(5):2666–74. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bunevicius R, Jakuboniene N, Jurkevicius R, Cernicat J, Lasas L, Prange AJ., Jr Thyroxine vs thyroxine plus triiodothyronine in treatment of hypothyroidism after thyroidectomy for Graves’ disease. Endocrine. 2002;18(2):129–33. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:18:2:129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bunevicius R, Kazanavicius G, Zalinkevicius R, Prange AJ., Jr Effects of thyroxine as compared with thyroxine plus triiodothyronine in patients with hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(6):424–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clyde PW, Harari AE, Getka EJ, Shakir KM. Combined levothyroxine plus liothyronine compared with levothyroxine alone in primary hypothyroidism: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(22):2952–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Escobar-Morreale HF, Botella-Carretero JI, Gomez-Bueno M, Galan JM, Barrios V, Sancho J. Thyroid hormone replacement therapy in primary hypothyroidism: a randomized trial comparing L-thyroxine plus liothyronine with L-thyroxine alone. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(6):412–24. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-6-200503150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fadeyev VV, Morgunova TB, Melnichenko GA, Dedov II. Combined therapy with L-thyroxine and L-triiodothyronine compared to L-thyroxine alone in the treatment of primary hypothyroidism. Hormones (Athens) 2010;9(3):245–52. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaminski J, Miasaki FY, Paz-Filho G, Graf H, Carvalho GA. Treatment of hypothyroidism with levothyroxine plus liothyronine: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2016;60(6):562–72. doi: 10.1590/2359-3997000000192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nygaard B, Jensen EW, Kvetny J, Jarlov A, Faber J. Effect of combination therapy with thyroxine (T4) and 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine versus T4 monotherapy in patients with hypothyroidism, a double-blind, randomised cross-over study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;161(6):895–902. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez T, Lavis VR, Meininger JC, Kapadia AS, Stafford LF. Substitution of liothyronine at a 1:5 ratio for a portion of levothyroxine: effect on fatigue, symptoms of depression, and working memory versus treatment with levothyroxine alone. Endocr Pract. 2005;11(4):223–33. doi: 10.4158/EP.11.4.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saravanan P, Simmons DJ, Greenwood R, Peters TJ, Dayan CM. Partial substitution of thyroxine (T4) with tri-iodothyronine in patients on T4 replacement therapy: results of a large community-based randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(2):805–12. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sawka AM, Gerstein HC, Marriott MJ, MacQueen GM, Joffe RT. Does a combination regimen of thyroxine (T4) and 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine improve depressive symptoms better than T4 alone in patients with hypothyroidism? Results of a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(10):4551–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siegmund W, Spieker K, Weike AI, Giessmann T, Modess C, Dabers T, et al. Replacement therapy with levothyroxine plus triiodothyronine (bioavailable molar ratio 14 : 1) is not superior to thyroxine alone to improve well-being and cognitive performance in hypothyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2004;60(6):750–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valizadeh M, Seyyed-Majidi MR, Hajibeigloo H, Momtazi S, Musavinasab N, Hayatbakhsh MR. Efficacy of combined levothyroxine and liothyronine as compared with levothyroxine monotherapy in primary hypothyroidism: a randomized controlled trial. Endocr Res. 2009;34(3):80–9. doi: 10.1080/07435800903156340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walsh JP, Shiels L, Lim EM, Bhagat CI, Ward LC, Stuckey BG, et al. Combined thyroxine/liothyronine treatment does not improve well-being, quality of life, or cognitive function compared to thyroxine alone: a randomized controlled trial in patients with primary hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(10):4543–50. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36*.Jonklaas J, Burman KD. Daily Administration of Short-Acting Liothyronine Is Associated with Significant Triiodothyronine Excursions and Fails to Alter Thyroid-Responsive Parameters. Thyroid. 2016;26(6):770–8. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0629. This study shows that T3 monotherapy is associated with significant fluctuations in serum T3 concentrations. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Celi FS, Zemskova M, Linderman JD, Babar NI, Skarulis MC, Csako G, et al. The pharmacodynamic equivalence of levothyroxine and liothyronine: a randomized, double blind, cross-over study in thyroidectomized patients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;72(5):709–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma C, Xie J, Huang X, Wang G, Wang Y, Wang X, et al. Thyroxine alone or thyroxine plus triiodothyronine replacement therapy for hypothyroidism. Nucl Med Commun. 2009;30(8):586–93. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e32832c79e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joffe RT, Brimacombe M, Levitt AJ, Stagnaro-Green A. Treatment of clinical hypothyroidism with thyroxine and triiodothyronine: a literature review and metaanalysis. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(5):379–84. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.48.5.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Escobar-Morreale HF, Botella-Carretero JI, Escobar del Rey F, Morreale de Escobar G. REVIEW: Treatment of hypothyroidism with combinations of levothyroxine plus liothyronine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(8):4946–54. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Butler PW, Smith SM, Linderman JD, Brychta RJ, Alberobello AT, Dubaz OM, et al. The Thr92Ala 5′ type 2 deiodinase gene polymorphism is associated with a delayed triiodothyronine secretion in response to the thyrotropin-releasing hormone-stimulation test: a pharmacogenomic study. Thyroid. 2010;20(12):1407–12. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McAninch EA, Jo S, Preite NZ, Farkas E, Mohacsik P, Fekete C, et al. Prevalent polymorphism in thyroid hormone-activating enzyme leaves a genetic fingerprint that underlies associated clinical syndromes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(3):920–33. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-4092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Panicker V, Saravanan P, Vaidya B, Evans J, Hattersley AT, Frayling TM, et al. Common variation in the DIO2 gene predicts baseline psychological well-being and response to combination thyroxine plus triiodothyronine therapy in hypothyroid patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(5):1623–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deshpande PR, Rajan S, Sudeepthi BL, Abdul Nazir CP. Patient-reported outcomes: A new era in clinical research. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2(4):137–44. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.86879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoang TD, Olsen CH, Mai VQ, Clyde PW, Shakir MK. Desiccated thyroid extract compared with levothyroxine in the treatment of hypothyroidism: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(5):1982–90. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bould H, Panicker V, Kessler D, Durant C, Lewis G, Dayan C, et al. Investigation of thyroid dysfunction is more likely in patients with high psychological morbidity. Fam Pract. 2012;29(2):163–7. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jorgensen P, Langhammer A, Krokstad S, Forsmo S. Is there an association between disease ignorance and self-rated health? The HUNT Study, a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2014;4(5):e004962. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(15):1547–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Armstrong SM, Wither JE, Borowoy AM, Landolt-Marticorena C, Davis AM, Johnson SR. Development, Sensibility, and Validity of a Systemic Autoimmune Rheumatic Disease Case Ascertainment Tool. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(1):18–23. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.160327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thvilum M, Brandt F, Almind D, Christensen K, Brix TH, Hegedus L. Increased psychiatric morbidity before and after the diagnosis of hypothyroidism: a nationwide register study. Thyroid. 2014;24(5):802–8. doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pop VJ, Maartens LH, Leusink G, van Son MJ, Knottnerus AA, Ward AM, et al. Are autoimmune thyroid dysfunction and depression related? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(9):3194–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.9.5131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ott J, Promberger R, Kober F, Neuhold N, Tea M, Huber JC, et al. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis affects symptom load and quality of life unrelated to hypothyroidism: a prospective case-control study in women undergoing thyroidectomy for benign goiter. Thyroid. 2011;21(2):161–7. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]