Abstract

Background

The somatostatin receptor subtype 2 (sstr2) is expressed on a majority of luminal breast cancers, however SPECT and scintigraphy imaging with agonistic sstr2 probes has been sub-optimal. High affinity antagonists can access more binding sites on the cell surface, resulting in higher tumor uptake and improved sensitivity. We compared the tumor uptake and biodistribution of the antagonist 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 with two agonists 68Ga-DOTA-Tyr3-octreotide (68Ga-DOTATOC) and 68Ga-DOTA-Tyr3-octreotate (68Ga-DOTATATE), in the human, sstr2-positive, luminal breast cancer model: ZR-75-1.

Results

Peptides were assayed for binding affinity using a filtration-based competitive assay to sstr2. natGa-DOTATOC and natGa-DOTATATE had excellent affinity (inhibition constant Ki: 0.9 ± 0.1 nM and 1.4 ± 0.3 nM respectively) compared to natGa-NODAGA-JR11 (25.9 ± 0.2 nM). The number of binding sites on ZR-75-1 cells was determined in vitro by saturation assays. Agonist 67/natGa-DOTATOC bound to 6.64 ± 0.39 × 104 sites/cells, which was 1.5-fold higher than 67/natGa-NODAGA-JR11 and 2.3-fold higher than 67/natGa-DOTATATE. All three 68Ga-labeled peptides were obtained in good decay-corrected radiochemical yield (61-68%) and were purified by high performance liquid chromatography to ensure high specific activity (137 – 281 MBq/nmol at the end of synthesis). NOD scid gamma mice bearing ZR-75-1 tumors were injected intravenously with the labeled peptides and used for PET/CT imaging and biodistribution at 1 h post-injection. We found that 68Ga-DOTATOC had the highest tumor uptake (18.4 ± 2.9%ID/g), followed by 68Ga-DOTATATE (15.2 ± 2.2%ID/g) and 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 (12.2 ± 0.8%ID/g). Tumor-to-blood and tumor-to-muscle ratios were also higher for the agonists (>40 and >150 respectively), compared to the antagonist (15.6 ± 2.2 and 45.2 ± 11.6 respectively).

Conclusions

The antagonist 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 had the lowest tumor uptake and contrast compared to agonists 68Ga-DOTATOC and 68Ga-DOTATATE in ZR-75-1 xenografts.

The main contributing factor to this result could be the use of an endogenously expressing cell line, which may differ from previously published transfected models in the number of low-affinity, antagonist-specific binding sites. The relative merit of agonists versus antagonists for sstr2 breast cancer imaging warrants further investigation, first in preclinical models with other sstr2-positive breast cancer xenografts, and ultimately in luminal breast cancer patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s41181-017-0023-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Somatostatin receptor, Breast cancer, Antagonists, Positron emission tomography, Peptides, JR11, ZR-75-1

Background

The somatostatin family of G-protein coupled receptors is comprised of five different subtypes which are variably expressed on many cancer types, most notably neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). Somatostatin receptor subtype 2 (sstr2) is the most commonly overexpressed subtype, and hence several high-affinity radiolabeled peptides (mostly agonists) have been developed for this target (Fani et al. 2012a; Krenning et al. 1993; Kwekkeboom et al. 2010; Maecke & Reubi 2011; Reubi et al. 2001; Reubi 2003). Such tracers have been used for diagnosis, as is the case with 111In-DTPA-D-Phe-octreotide (111In-pentatreotide), 68Ga-DOTA-Tyr3-octreotate (68Ga-DOTATATE) and 68Ga-DOTA-Tyr3-octreotide (68Ga-DOTATOC), or therapy with 90Y-DOTATOC and 177Lu-DOTATATE (Fani et al. 2012a; Krenning et al. 1993; Kwekkeboom et al. 2010; Maecke & Reubi 2011; Reubi 2003).

Similar to NETs, breast tumors differentially express somatostatin receptors compared to non-malignant tissue (Fani et al. 2012b). Several studies have evaluated the expression of sstr2 in different patient cohorts, showing that 15-66% of breast tumors were sstr-positive by autoradiography (Dalm et al. 2015; Foekens et al. 1989; Bootsma et al. 1993), 30-85% by immunohistochemistry (Ciocca et al. 1990; Schulz et al. 1998), and 97-100% by mRNA analysis (Kumar et al. 2005; Vikic-Topic et al. 1995; Evans et al. 1997). The high variability observed between reports may be due to heterogeneous intra-tumor receptor density (Reubi et al. 1990) and lack of patient stratification. Sstr2 expression strongly correlates with luminal A markers (estrogen and progesterone receptor), and is typically not found in the other breast cancer subtypes (Dalm et al. 2015; Frati et al. 2014; Reubi & Torhorst 1989). Imaging with sstr agents can therefore be applicable to a large patient population, as luminal A cancers comprise 75% of all breast cancer cases (Kwan et al. 2009).

Compared to NETs, breast cancer sstr2 density is lower and more heterogeneous as determined using autoradiography (Reubi et al. 2002; Cescato et al. 2011) and PET/CT imaging (Elgeti et al. 2008). Diagnostic SPECT and scintigraphy with 111In-pentatreotide and 99mTc-depreotide, have been explored clinically in patients with sstr2-positive breast cancer (Alberini et al. 2000; van Eijck et al. 1994; Wang et al. 2008). Sensitivity suffered in these initial studies, partly due to the low resolution of conventional scintigraphy, as well as the lower and more heterogeneous expression of sstr2 on breast carcinoma compared to NETs (Alberini et al. 2000; van Eijck et al. 1994; Wang et al. 2008).

More recently, a number of reports have identified several antagonist somatostatin analogs that visualized sstr2-positive tumors better than conventional agonists in both preclinical and clinical cases. Ginj et al. first demonstrated this finding by comparing an sstr3 agonist and sstr3 antagonist of similar binding affinities in a tumor of human embryotic kidney (HEK) cells transfected with sstr3. Scatchard analysis of these compounds revealed that the antagonist bound to more sites on the tumor cells, resulting in an overall higher tumor uptake, despite marginally lower binding affinity and no internalization capacity (Ginj et al. 2006). Since then, several sstr2 antagonists, labeled with either diagnostic or therapeutic isotopes, have been explored (Fani et al. 2012b; Cescato et al. 2011; Fani et al. 2011; Wild et al. 2011; Wild et al. 2014). Cescato et al. performed in vitro autoradiography on several sstr2-positive primary tumor samples, including breast carcinomas, and suggested that the antagonist 177Lu-DOTA-BASS bound to more sites on the tumor samples than the agonist 177Lu-DOTATATE (Cescato et al. 2011). In clinical studies involving NET patients, the diagnostic antagonist 111In-DOTA-BASS showed improved contrast compared the conventional agonist 111In-pentatreotide (Wild et al. 2011). Furthermore, the therapeutic antagonist 177Lu-DOTA-JR11 delivered a 1.7 - 10.6 fold higher tumor dose than the agonist 177Lu-DOTATATE in a small pilot study comprised of 4 patients with advanced NETs (Wild et al. 2014).

Several breast cancer patients with recurrent or metastatic luminal breast cancer eventually develop resistance to endocrine therapies (Milani et al. 2014). The subset of patients that express high levels of sstr2 might benefit from treatment by peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) with somatostatin analogs if sufficient radiotracer accumulation is achieved (Dalm et al. 2016). Because antagonists can bind to more sites, it is possible that tumors with lower sstr2 density, such as breast cancers, might still be visualized and treated with radiolabeled peptides.

68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 showed excellent tumor uptake and biodistribution compared to 68Ga-DOTATATE in a preclinical setting (Fani et al. 2012b), and ~15% higher SUVmax uptake in NET patients compared to 68Ga-DOTATOC (Nicolas et al. 2015). The aim of this study was to compare a potent antagonist, 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11, and two commonly used agonists, 68Ga-DOTATATE and 68Ga-DOTATOC, for in vivo breast cancer imaging using a human xenograft model with endogenous sstr2 expression. We used the sstr2-positive luminal A breast cancer cell line ZR-75-1 (Subik et al. 2010) and determined the transcriptional expression of the five sstr subtypes in those cells. The binding affinity of the peptides to human sstr2 was measured using identical assay conditions, and biodistribution of the radiolabeled peptides was compared.

Methods

General methods

All reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification except otherwise specified. Peptides DOTATATE, DOTATOC, and NODAGA-JR11 and the cold standards of their natural gallium (natGa) complexes were prepared by standard fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis according to literature procedures (Fani et al. 2012b; Heppeler et al. 1999). C18 Sep-Pak cartridges (1 cm3, 50 mg) were obtained from Waters Corporation (Milford, MA) and pre-washed with ethanol followed by deionized (DI) water prior to use. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) purification and quality control were performed on a semi-preparative column (C18, 5 μm, 250 × 10 mm), or an analytical column (C18, 5 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm) respectively, both purchased from Phenomenex (Torrance, CA) and used on an Agilent 1260 infinity platform (Santa Clara, CA). Triethylammonium phosphate buffer (TEAP), phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and acetonitile (MeCN) were used for HPLC elution. TEAP buffer (pH 7.3) was prepared by titrating triethylamine (8 mL) with o-phosphoric acid in DI water (1 L), and PBS (pH 7.4) was prepared by dissolving PBS powder or tablets in DI water. The pH was monitored using a Denver Instrument UltraBasic Benchtop pH meter (Bohemia, NY), and solvents were filtered using 0.2 μm filters (Whatman, GE Healthcare or Durapore, Merck Milliproe) prior to use.68Ga was eluted from a 50 mCi 68Ge/68Ga generator (iThemba LABS, South Africa) and purified according to reported methods (Lin et al. 2015). 67Ga-citrate was purchased from Isologic (Burlington, Canada) and also purified following the same procedures. The activity was measured using a Capintec (Ramsey, NJ) CRC®-25R/W dose calibrator.

Binding affinity

The binding affinity of natGa-labeled compounds, natGa-DOTATOC, natGa-DOTATATE and natGa-NODAGA-JR11 to sstr2 was determined using a membrane-based competition binding assay. Somatostatin-28 (SRIF-28) purchased from Bachem (Torrance, CA) was used as a known positive control for affinity determination. Purified Chinese hamster ovary-K1 (CHO-K1) membranes overexpressing human sstr2 (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) were incubated with 125I-[Tyr11]-somatostatin-14 (125I-[Tyr11]-SRIF14, Perkin Elmer) and competing non-radioactive ligand in a 96-well, 1.2 μm glass fibre filter plate (EMD Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Prior to assay, the plate filters were pre-soaked in 0.1% polythylenimine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 1 h at ambient temperature. Following pre-incubation, membranes (25 μg/well), 125I-[Tyr11]-SRIF14 (0.05 nM) and various concentrations of competing peptides (10 μM to 1 pM) were diluted in assay buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5% BSA) and incubated for 1 h at 27 °C with moderate shaking. Once complete, the incubation mixture was aspirated through the filters, followed by 6 washes with 200 μL ice-cold wash buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 0.2% BSA). Each filter was removed and counted on a PerkinElmer WIZARD 2480 gamma counter. The inhibition constant (Ki) was calculated by fitting the data to a one-site Fit-Ki curve in GraphPad Prism v7.02. To ensure that the concentration of our peptides, and hence our determination of Ki, was accurate, the peptide concentration was determined by amino acid analysis at the SPARC BioCentre (Toronto Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada), where peptides were hydrolyzed and comprising amino acids were separated on HPLC. The peptide content was calculated by comparing the concentration of selected amino acids to known standards.

Radiolabeling

68GaCl3 in 0.5 mL DI water was added into an 8 mL glass vial preloaded with 25 μg (30 μg for NODAGA-JR11) peptide precursor and HEPES buffer solution (0.7 mL, pH 5). The vial was sealed with a screw cap and heated in a microwave oven (catalog number: DMW7700WDB, Danby Appliance, Findlay, Ohio) as described previously (Lin et al. 2015). Heating time was 60 s, and the microwave power level was set to “2.” Reaction temperature was not determined. The reaction mixture was cooled, and directly injected into the HPLC semi-preparative column (4.5 mL/min) for purification. HPLC conditions, buffers and retention times are described in Table 1. The 68Ga-labeled peptide was collected and diluted with 50 mL 0.05 M ammonium formate solution and passed through a C18 light Sep-Pak cartridge. The product was eluted with 90% ethanol in saline and formulated in saline for animal studies. The Sep-Pak purification was performed to remove HPLC solvents (especially MeCN), concentrate the product, and formulate the tracer in solution suitable for injection into mice. Quality control was done using the analytical column (2 mL/min) and the same conditions described in Table 1. Specific activity was calculated via dividing the radioactivity injected into HPLC (analytical column) by the mass of the tracer. The mass of the radiotracer was calculated based on UV absorbance from a standard curve, constructed using serial dilutions of corresponding natGa cold-standard. Radiolabeling with 67Ga for saturation binding assays was performed according to the same procedures for the preparation of their 68Ga analogs.

Table 1.

HPLC conditions and retention times (t R)

| Tracer | HPLC conditions | t R on semi-preparative column | t R on analytical column |

|---|---|---|---|

| 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 | 77% / 23% PBS/ MeCN | 14.3 min | 5.3 min |

| 68Ga-DOTATOC | 79% / 21% PBS / MeCN | 19.2 min | 6.8 min |

| 68Ga-DOTATATE | 81% / 19% TEAP / MeCN | 20.4 min | 7.4 min |

Cell culture

All imaging and biodistribution studies were performed using the human breast carcinoma, ER-positive cell model ZR-75-1 purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). In addition, HeLa cells, Jurkat cells (ATCC) and sstr5-transfected HEK-293 cells (HEK-sstr5, gifted from Dr. Stefan Schultz, Universitaetsklinikum, Jena, Germany) were used for quantitative-PCR (qPCR) standard curve construction. ZR-75-1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 + GlutaMAXTM media purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA) and supplemented with 10% FBS from VWR Life Science Seradigm (Radnor, PA). Jurkat cells were grown in the same base media, and contained 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 1 mM sodium pyruvate. HeLa cells were grown in DMEM + GlutaMAXTM (Life Technologies) with 10% FBS. HEK-sstr5 cells were grown in DMEM + GlutaMAXTM with 10% FBS, and contained 0.5 mg/mL G418 to maintain sstr5 expression. All cell cultures were exposed to 100 I.U./mL penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies) and grown in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Quantitative-PCR

The transcriptional expression of sstr1, sstr2, sstr3, sstr4 and sstr5 in ZR-75-1 cells was determined relative to reference gene hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT1) using qPCR. Total RNA from ZR-75-1 cells was purified using the GenEluteTM Mammalian total RNA miniprep kit (Sigma), treated with amplification grade DNase I (Sigma), and measured using a NanoDropTM spectrophotometer. 2.0 μg of total ZR-75-1 RNA was reverse transcribed in a 20 μL reaction using SuperScript® VILOTM cDNA synthesis kit from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). qPCR was set up in 384-well plates, in a total volume of 10 μL; each reaction containing 1 μL template cDNA, 500 μM forward and reverse primers, 250 μM probe, and 1X SsoAdvancedTM universal probes supermix from Bio Rad (Hercules, CA). Each reaction was performed in triplicates and repeated 3 times. Predefined primers (forward and reverse) and probes for all six genes were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, Iowa); see Additional file 1 for assay names. The QuantstudioTM 6 K Flex Real-Time PCR system from Thermo Fisher (Carlsbad, CA) was used for amplification and detection. The concentration of each target was determined by interpolating the Ct value from respective standard curves of known concentrations. To construct the standard curves, RNA from cell lines with known expression of sstr subtypes was purified and reverse-transcribed as described above. Target sstr genes were PCR amplified using Q5® high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions, using the same primers as the qPCR reactions (without the fluorogenic probe). PCR products were separated on a 2% agarose gel, and target bands were extracted and purified using the Monarch® DNA gel extraction kit (New England BioLabs). The amount of DNA was quantified using Qubit® dsDNA HS assay kit (Thermo Fisher) and the number of copies/μL was calculated using the following formula:

Standard curves were constructed from 10-fold serial dilutions (105 copies/μL to 1 copy/μL) and assayed by qPCR in triplicates. All standard curves were repeated 2–3 times. Sstr1 transcripts were amplified from HeLa cells, sstr2 from ZR-75-1 cells, sstr3 from Jurkat cells, sstr4 from the ChantestTM human sstr4 receptor cell line (irradiated cells) from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA), and both sstr5 and HPRT1 from HEK-sstr5 cells. Representative standard curves, primer and probe information, and cycling conditions for both PCR and qPCR can be found in the Additional file 1.

Saturation binding assays

Saturation binding assays were performed in vitro on ZR-75-1 cells using variable concentrations (0.1 – 100 nM) of 67/natGa-labeled tracers. Cells were grown to near-confluence in 12-well plates, and growth media was replaced with reaction media (RPMI, 1% BSA, 100 I.U./mL penicillin/streptomycin) 1 h before the assay. Cells were treated in duplicates with 67/natGa-DOTATOC, 67/natGa-DOTATATE or 67/natGa-NODAGA-JR11 in 500 μL reaction media and incubated for 1 h at 25 °C. Excess cold-standard (1.2 μM) was used to block receptors and determine non-specific binding. After the incubation period, the reaction media was aspirated, and the cells were washed 3 times with cold PBS. Cells were lysed and collected with 1 M NaOH and counted in a PerkinElmer WIZARD 2480 gamma counter. The number of binding sites per cell was calculated and fitted to a one-site binding model in GraphPad Prism 7.02 to determine the dissociation constant (Kd) and number of binding sites (Bmax).

Estrogen pellet implant and tumor inoculation

All animal studies were done in compliance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care guidelines and were approved by the Animal Care Committee of University of British Columbia (Vancouver, Canada). Immunodeficient female NOD.Cg-Prkdc sci Il2rg tm1Wjl/SzJ mice (NOD scid gamma) were obtained from an in-house breeding colony at the Animal Resource Centre of the BC Cancer Agency Research Centre and also from Jackson Laboratory. To sustain the growth of the ER-positive ZR-75-1 cell model, animals were administered a 1.7 mg, 60-day slow-release estrogen pellet from Innovative Research of America (Sarasota, FL) subcutaneously in the dorsal space of the neck. 3–5 days post pellet-implant, 10 million ZR-75-1 cells were re-suspended in a mixture of 1:1 PBS and Matrigel (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) and inoculated subcutaneously on the right shoulder. Tumors were grown for 5–6 weeks, until they reached a size of 7–11 mm in diameter.

Biodistribution studies

Mice were sedated using 2 mL/min of O2 with 2% isoflurane and injected intravenously (i.v.) with 1–2 MBq of 68Ga-labeled peptide. Mice were allowed to roam freely for 60 min prior to euthanasia by 2 mL/min of O2 with 4% isoflurane followed by CO2 asphyxiation. Blood was promptly collected by cardiac puncture and weighted. Internal organs were harvested, rinsed in PBS, patted dry and weighed. Organ uptake was measured either in a WIZARD 2480 gamma counter (Perkin Elmer) or Cobra II auto-gamma counter (Packard), both calibrated with standards of known 68Ga activity. Uptake was normalized to the injected dose and to the respective weight of the organ, and expressed as percent injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g).

PET/CT imaging

Tumor-bearing mice were injected i.v. with 8–9 MBq of 68Ga-labeled peptide. Static PET images were acquired 55 min post-injection for 10 min using an Inveon microPET/CT scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) as described previously (Lin et al. 2015). A baseline CT scan was used for localization and attenuation correction. Mice were promptly euthanized after imaging, and biodistribution studies were undertaken as described above.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism v7.02 software. Transcriptional sstr expression results were tested using a one-way ANOVA. Binding affinity, Bmax values, Kd values and in vivo organ uptakes were compared between the three groups using a one-way ANOVA. The difference was considered statistically significant if the p value was < 0.05. Non-statistically significant findings were indicated as “ns.”

Results

Binding affinity and radiolabeling

natGa-DOTATOC and natGa-DOTATATE had an inhibition constant (Ki) in the low nanomolar range (0.9 ± 0.1 nM, n = 4 and 1.4 ± 0.3 nM, n = 3 respectively), while the Ki of natGa-NODAGA-JR11 was higher (25.9 ± 0.2 nM, n =3, p < 0.001). The SRIF-28 control had a Ki of 3.7 ± 1.7 nM (n = 5) in our assays. Representative inhibition curves are shown in Fig. 1. Multiple batches of 68Ga-DOTATOC, 68Ga-DOTATATE and 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 were prepared in good radiochemical yield (61 ± 5, 62 ± 8 and 68 ± 13% respectively, n = 3), purity (>98%) and high specific activity (251.6 ± 33.9, 197.3 ± 85.2 and 138.8 ± 2.6 MBq/nmol respectively, n = 3). The particular tracer preparations used for animal studies corresponded to radiochemical yields of 62, 66 and 58% and specific activities of 281.2, 218.3 and 136.9 MBq/nmol for 68Ga-DOTATOC, 68Ga-DOTATATE and 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 respectively.

Fig. 1.

Representative inhibition curves for natGa-DOTATOC, natGa-DOTATATE, natGa-NODAGA-JR11 and SRIF-28 against the binding of 125I-[Tyr11]-SRIF14 to sstr2-overexpressing CHO-K1 membranes

Saturation binding assays

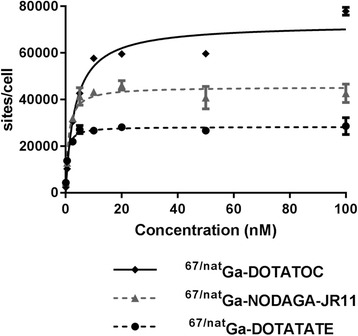

67Ga-labeled peptides used for saturation binding assays were prepared using the same procedures as the 68Ga-analogs. 67Ga-NODAGA-JR11, 67Ga-DOTATOC and 67Ga-DOTATATE were labeled in 4, 57, 25% decay-corrected radiochemical yield, > 99% radiochemical purity and 11.5, 392, 444 MBq/nmol specific activity respectively. In vitro saturation binding assays revealed that agonist 67/natGa-DOTATOC bound to more sites on ZR-75-1 cells (6.64 ± 0.39 × 104 sites/cell) compared to both 67/natGa-DOTATATE (2.85 ± 0.02 × 104 sites/cell, p < 0.001) and 67/natGa-NODAGA-JR11 (4.39 ± 0.32 × 104 sites/cell, p < 0.001). The dissociation constant (Kd) in these assays was lowest for 67/natGa-DOTATATE (0.55 ± 0.015 nM), followed by 67/natGa-NODAGA-JR11 (1.19 ± 0.06 nM, p < 0.001) and finally 67/natGa-DOTATOC (2.70 ± 0.13 nM, p < 0.001). See Table 2 for Bmax and Kd values, and Fig. 2 for representative saturation binding curves.

Table 2.

Saturation binding results for respective radiotracers with ZR-75-1 cells

| 67/natGa-NODAGA-JR11 (n = 3) |

67/natGa-DOTATOC (n = 3) |

67/natGa-DOTATATE (n = 3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bmax

(× 104 sites/cell) |

4.39 ± 0.32 | 6.64 ± 0.39 | 2.85 ± 0.02 |

| Kd (nM) | 1.19 ± 0.06 | 2.70 ± 0.13 | 0.55 ± 0.02 |

Fig. 2.

Representative saturation binding curves for 67/natGa-NODAGA-JR11, 67/natGa-DOTATOC and 67/natGa-DOTATATE to ZR-75-1 cells in vitro. The non-specific binding, determined by blocking with excess cold-standard, was subtracted and only specific binding is shown

Transcriptional Sstr expression

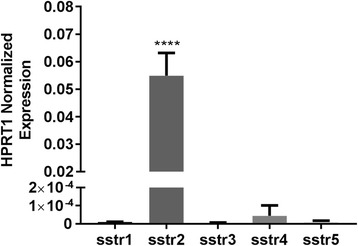

We calculated the target gene/HPRT1 copy number ratio for all five somatostatin subtypes and found predominant expression of sstr2. The normalized expression of sstr2 to HPRT1 was 0.055 ± 0.0083 (n = 3), and < 0.00005 for all other subtypes (n = 3 each, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). For all subtypes except sstr2, we calculated < 10 copies/μL of target transcript in our cDNA preparation. In comparison, we identified 12,915 ± 2218 copies/μL (n = 4) HPRT1 transcripts, and 681 ± 148 (n = 3) copies/μL sstr2 transcripts.

Fig. 3.

Relative transcriptional expression of sstr subtypes normalized to housekeeping gene HPRT1 (n = 3 for each)

Tumor and organ uptake

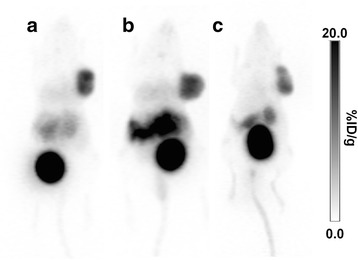

A full overview of tracer biodistribution is presented in Table 3. Among the three tested tracers, we found that the antagonist 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 had the lowest tumor uptake (12.2 ± 0.8%ID/g) compared to agonists 68Ga-DOTATOC (18.4 ± 2.9%ID/g, p < 0.001) and 68Ga-DOTATATE (15.2 ± 2.2%ID/g, ns) (Fig. 4). 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 had tumor-to-blood and tumor-to-muscle ratios of 15.6 ± 2.2 and 45.2 ± 11.6 respectively compared to 68Ga-DOTATOC (41.1 ± 5.7, p < 0.001 and 171.5 ± 55.3, p < 0.01 respectively) and 68Ga-DOTATATE (44.7 ± 11.7, p < 0.001 and 152.0 ± 60.8, p < 0.01 respectively). 68Ga-DOTATATE had the highest uptake in non-tumor sstr2-positive organs such as intestines, stomach, pancreas, adrenal glands and lungs, followed by 68Ga-DOTATOC and lastly by 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11. The excretion profile of all three tracers was predominantly renal, with high uptake in the kidneys and bladder, and low uptake in the liver. The agonist 68Ga-DOTATATE had the lowest kidney uptake (8.5 ± 1.7%ID/g), compared to 68Ga-DOTATOC (9.3 ± 1.7%ID/g) and 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 (14.1 ± 1.7%ID/g).

Table 3.

Biodistibution of 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11, 68Ga-DOTATOC and 68Ga-DOTATATE in NOD scid gamma ZR-75-1 tumor-bearing mice

|

68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 n = 5 |

68Ga-DOTATOC n = 6 |

68Ga-DOTATATE n = 6 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Tumor | 12.21 | 0.78 | 18.44 | 2.87 *** | 15.22 | 2.20 |

| Blood | 0.80 | 0.10 | 0.45 | 0.09 *** | 0.35 | 0.06 *** |

| Fat | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.15 |

| Ovaries | 0.67 | 0.22 | 0.51 | 0.07 | 0.89 | 0.35 |

| Uterus | 0.86 | 0.22 | 0.54 | 0.11 | 0.84 | 0.10 |

| Intestines | 0.90 | 0.20 | 2.39 | 0.30 *** | 7.35 | 0.44 *** |

| Stomach | 1.36 | 0.78 | 2.75 | 1.25 | 8.29 | 3.06 *** |

| Pancreas | 9.29 | 2.03 | 11.01 | 1.32 | 51.56 | 5.47 *** |

| Spleen | 0.39 | 0.05 | 0.46 | 0.11 | 0.84 | 0.38 |

| Kidneys | 14.12 | 1.65 | 9.27 | 1.73 *** | 8.45 | 1.73 *** |

| Adrenals | 2.00 | 0.65 | 9.52 | 3.78 ** | 15.20 | 7.26 ** |

| Liver | 0.99 | 0.12 | 0.71 | 0.17 | 1.95 | 0.52 *** |

| Lungs | 4.72 | 0.71 | 22.93 | 6.12 *** | 28.66 | 2.94 *** |

| Heart | 0.46 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.04 * | 0.67 | 0.13 ** |

| Muscle | 0.28 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.02 *** | 0.11 | 0.04 *** |

| Bone | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.03 |

| Brain | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Tumor to Background Ratios | ||||||

| Blood | 15.56 | 2.20 | 41.13 | 5.68 *** | 44.65 | 11.74 *** |

| Muscle | 45.15 | 11.56 | 171.51 | 55.33 ** | 151.95 | 60.75 ** |

| Kidneys | 0.87 | 0.12 | 2.01 | 0.24 *** | 1.88 | 0.48 *** |

Organ uptake is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) in units of percent injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g). The tumor uptake is highlighted in bold. Means were statistically compared to the respective organ uptake of 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 and p values < 0.05, < 0.01, and < 0.001 were expressed as *, ** and *** respectively

Fig. 4.

PET maximum intensity projection images of a. 68Ga-DOTATOC, b. 68Ga-DOTATATE and c. 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 in ZR-75-1 tumor bearing mice

Discussion

In this study, we used a human breast cancer cell model with endogenous sstr2 expression (ZR-75-1 cells) to compare tumor uptake of the antagonist 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 with two routinely used agonists 68Ga-DOTATOC and 68Ga-DOTATATE. Most studies evaluating sstr tracers in vivo typically used a rat pancreatic cell model, i.e. AR42J (Froidevaux et al. 2002), or HEK cells transfected with somatostatin receptors (Fani et al. 2012b; Ginj et al. 2006; Fani et al. 2011), which may not adequately represent a breast cancer phenotype. We chose to use the chelator NODAGA instead of DOTA for the antagonist, as 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 showed better binding affinity and higher tumor uptake compared to 68Ga-DOTA-JR11 in a preclinical model (Fani et al. 2012b). 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 is a more potent antagonist, and thus a better candidate for comparison with the current gold-standard agonists 68Ga-DOTATOC and 68Ga-DOTATATE.

We looked at the transcriptional expression of all five sstr subtypes in ZR-75-1 cells in vitro and found predominant expression of sstr2, with negligible expression of the other four subtypes. The HPRT1-normalized expression level was 0.055 ± 0.0083 for sstr2, and < 0.00005 (p < 0.001) for sstr1, sstr3, sstr4 and sstr5. Previous studies have reported a strong correlation between sstr mRNA and protein expression, suggesting that transcriptional studies are adequate for profiling this receptor family (Kumar et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2008; Schaer et al. 1997). Breast carcinoma samples typically show varied expression of all five subtypes, often with 2 or 3 subtypes co-expressed on the same sample (Kumar et al. 2005; Schaer et al. 1997). Although sstr1, sstr3 and sstr5 were identified at high levels in a number of cases, sstr2 was the most commonly expressed (Reubi et al. 2001; Kumar et al. 2005; Vikic-Topic et al. 1995; Evans et al. 1997; Schaer et al. 1997).

We tested the binding affinities of the peptides natGa-DOTATOC, natGa-DOTATATE and natGa-NODAGA-JR11 to human sstr2 in a filtration-based, competition binding assay. For the agonists natGa-DOTATOC, natGa-DOTATATE and SRIF-28, our inhibition constants (Ki) were 0.9 ± 0.1, 1.4 ± 0.3 and 3.7 ± 1.7 nM respectively. Our Ki values are comparable to the IC50 values reported by Reubi et al. (Ki values were not reported), which were 2.5 ± 0.50, 0.2 ± 0.04 and 2.7 ± 0.30 nM respectively (Reubi et al. 2000). As IC50 values are dependent on the concentration of substrates used in a specific assay, they are not reproducible between laboratories, and it is recommended that Ki values are calculated. Although natGa-DOTATATE was reported to have very high affinity to sstr2 (12 fold higher than natGa-DOTATOC) (Reubi et al. 2000), we did not observe this in our experiments. This may explain, in part, why the diagnostic performance of both peptides is similar in clinical studies, with perhaps a slight advantage for 68Ga-DOTATOC (Poeppel et al. 2011).

We observed a significantly lower binding affinity for the antagonist natGa-NODAGA-JR11 (Ki = 25.9 ± 0.2 nM) compared to the two agonists, and also compared to the IC50 reported by Fani et al. (IC50 = 1.2 ± 0.2 nM) (Fani et al. 2012b). These differences could be partially attributed to differences in methodology and assay conditions. We used a filtration-based binding assay with an SRIF-14 based competing hot ligand (125I-[Tyr11]-SRIF14), whereas other reports used an autoradiography approach and the SRIF-28 analog: 125I-[Leu8, DTrp22, Tyr25]-somatostatin-28 (Fani et al. 2012b). A standardized assay system and a direct comparison between classical protein binding assays and autoradiography methods would be valuable to improve our understanding of the structure-activity relationship of these ligands. When assessing binding affinity based on Kd values, we observed a different relationship, more closely resembling that reported in the literature. 67/natGa-DOTATATE bound sstr2 receptors on ZR-75-1 cells with the lowest Kd (0.55 ± 0.02 nM) compared to 67/natGa-DOTATOC (2.70 ± 0.13 nM) and 67/natGa-NODAGA-JR11 (1.19 ± 0.06 nM). It appears that 67/natGa-NODAGA-JR11 binds receptors on ZR-75-1 cells with high affinity, but is not as potent when competing with reference ligand 125I-[Tyr11]-SRIF14. These findings are interesting and unexpected, and indicate several factors that must be considered when choosing assay conditions to measure affinities.

When tested in vivo, the agonist 68Ga-DOTATOC had the highest tumor uptake (18.4 ± 2.9%ID/g) compared to 68Ga-DOTATATE (15.2 ± 2.2%ID/g, ns) and 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 (12.2 ± 0.8%ID/g, p < 0.001). 67/natGa-DOTATOC also had the highest Bmax value in saturation binding assays (6.64 ± 0.39 × 104 sites/cell), even higher than that observed for antagonist 67/natGa-NODAGA-JR11 (4.39 ± 0.32 × 104 sites/cell, p < 0.001). These results contrast recently published reports stating that antagonists can achieve higher tumor uptake by binding more receptor sites (Fani et al. 2012b; Ginj et al. 2006). It is possible that in a cell model where the target G-protein coupled receptor is overexpressed without concomitant overexpression of the associated G-protein, there would be a greater number of receptors in a low-affinity state (unbound by G-protein), and therefore significantly higher Bmax values observed for antagonists compared to agonists (Kenakin 1997). Overexpression of, not only the receptors, but also the associated G-protein, would be required to have a more representative model. When Ishihara et al. also overexpressed the G-protein in COS cells transfected with secretin receptor, the number of agonists binding sites increased from 1.8% (of the total seen by the antagonist) to 15% (Ishihara et al. 1991). In an endogenous model, such as the one used herein, where most receptors are found in a high affinity state (bound by the G-protein), imaging with antagonists might not be more advantageous. Similar to our studies, Wadas et al. did not observe higher tumor uptake with antagonist 64Cu-CB-TE2A-sst2-ANT compared to agonist 64Cu-CB-TE2A-Y3-TATE when using the endogenously expressing sstr2 model, AR42J (Wadas et al. 2008). It is also interesting that the agonists 67/natGa-DOTATOC and 67/natGa-DOTATATE showed differing number of binding sites (6.64 ± 0.39 and 2.85 ± 0.021× 104 sites/cell respectively) on the ZR-75-1 cells used in this study. This is an unexpected finding, which could explain why both these compounds have comparable tumor uptake clinically, despite differences in binding affinity.

We observed that other sstr2-positive organs such as pancreas, adrenal glands, intestine and stomach had very high uptake with agonist 68Ga-DOTATATE compared to the other two radiotracers. This finding can be explained by injected peptide amount, which was lowest for 68Ga-DOTATATE (15.6 ± 4.4 pmol/mouse) compared to 68Ga-DOTATOC (33.0 ± 33.5 pmol/mouse) and 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 (40.3 ± 21.5 pmol/mouse). A biphasic relationship between uptake in receptor-positive organs and injected peptide mass has been reported, with maximum tumor uptake reached between 10 – 100 pmol/mouse (Bernhardt et al. 2003; de Jong et al. 1999; Notni et al. 2016). In other sstr2-positive organs, maximum uptake is achieved at lower peptide doses, presumably due to lower absolute receptor quantities (more regionally concentrated) and therefore lower saturation limits in these organs (Bernhardt et al. 2003; de Jong et al. 1999; Notni et al. 2016). In our studies, low capacity organs (i.e. pancreas, adrenals, intestine and stomach), but not high capacity organs (i.e. tumor), showed elevated uptake with 68Ga-DOTATATE, indicating this to be a peptide mass effect.

Although tumor uptake is also influenced by peptide dose, we believe the mass differences in our studies were not significant enough to cause major differences between the three groups. De Jong et al. showed optimal CA20948 uptake when 111In-DOTATOC was injected in 0.5 μg/rat (~30 pmol/mouse), with uptake > 80% of the maximum in the 0.25 – 1 μg/rat range (~15 – 60 pmol/mouse) (de Jong et al. 1999). Similarly Bernhardt et al. showed > 70% of maximum tumor uptake with 111In-pentetreotide (GOT1 cell model) when the tracer was injected between 6.4 – 664 pmol/mouse (Bernhardt et al. 2003). Indeed, normalization of peptide content would remove some variability, and enable a more accurate comparison.

Tumor-to-blood and tumor-to-muscle ratios were lower for 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 (15.6 ± 2.2 and 45.2 ± 11.6 respectively) compared to 68Ga-DOTATOC (41.1 ± 5.7 and 171.5 ± 55.3 respectively) and 68Ga-DOTA-TATE (44.7 ± 11.7 and 152.0 ± 60.8 respectively). 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 had a ~2 fold higher uptake in the blood and muscle compared to the other two agonists, accounting for the lower tumor contrast. These results differ significantly from recently reported clinical data in subjects with neuroendocrine tumors (Nicolas et al. 2016). The improved contrast reported by Nicolas et al. might be caused by a combination of lower specific activity, combined with a lower binding affinity of 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 (68Ga-OPS202) to sstr2, which may decrease tracer accumulation in low capacity binding sites (Nicolas et al. 2016). Alternatively, different pharmacokinetic properties between mice and humans may also contribute to these conflicting results.

All three tested peptides had predominant renal clearance. Exogenous estrogen pellets are known to cause hydronephrosis and urine retention (Gakhar et al. 2009; Ingberg et al. 2012), thus we expected higher than normal kidney uptake due to the indirect effects of estrogen.

Beyond diagnosis, sstr2-targeting tracers can also be used therapeutically. Diagnostic somatostatin radiotracers, such as the ones evaluated in this study, can identify breast cancer lesions and monitor response to therapy by PRRT. Treatment of sstr2-positive breast cancer with therapeutic agents such as 177Lu-DOTATATE, 177Lu-DOTATOC and 177Lu-DOTA-JR11 could be particularly valuable to patients that develop resistance to conventional endocrine therapy. The efficacy and safety of 177Lu-DOTATATE was demonstrated in an international, multi-centric phase III clinical trial, and showed a potent tumor response and very favourable toxicity in patients with metastatic midgut NETs (NCT01578239) (Strosberg et al. 2016). Similarly, the safety and tolerability of 177Lu-DOTA-JR11, also known as 177Lu-OPS201, is currently being tested in phase I/II clinical trials for NET patients (NCT02592707).

Conclusion

We compared the tumor uptake and biodistribution of two well-known agonists and one antagonist in vivo using ZR-75-1 tumors, a human breast cancer xenograft with endogenous sstr2 expression. In this model, the antagonist 68Ga-NODAGA-JR11 had the lowest tumor uptake and contrast among the three tracers; a finding that differs significantly from recently published reports. This result may be explained by the use of an endogenously expressing sstr2 cell model, which would have fewer low-affinity binding sites compared to transfected models. More studies are needed to determine if antagonists are better radiotracers for sstr2 breast cancer imaging than agonists, particularly in other breast cancer xenografts, and ultimately in luminal breast cancer patients.

Additional file

Supplemental information. Figure S1. Representative standard curve for absolute quantification qPCR experiments. Table S1. Standard curve parameters. Table S2. PCR Cycling conditions. Table S3. qPCR Cycling conditions. (DOCX 38 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Chengcheng Zhang, Dr. Joseph Lau and Gemma Dias for meaningful discussion and input at all steps of this study. We would also like to thank the Animal Resource Centre (ARC) at the BC Cancer Agency Research Center for animal monitoring and care, and Dr. Jinhe Pan for help eluting the 68Ge/68Ga generator.

Funding

This study was funded by the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation.

Authors’ contributions

FB and KSL conceived and designed the complete study. Binding affinity assays, qPCR experiments, saturation binding assays, and biodistribution studies were performed by ID. Animal procedures and monitoring were primarily done by ID with some assistance and critical input from HM. ZZ was responsible for chemical synthesis and quality control of cold standards and radiotracers. NC, NHJ and JR were responsible for PET/CT image acquisition. The manuscript was drafted by ID with critical revisions from FB, KSL and ZZ. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors of this manuscript have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

All animal studies were done in compliance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care guidelines and were approved by the Animal Care Committee of University of British Columbia (Vancouver, BC, Canada).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- %ID/g

Percent injected dose per gram

- 111In-Pentatrotide

111In-DTPA-D-Phe-octreotide

- 125I-[Tyr11]-SRIF14

125I-Tyr11-somatostatin 14

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- cDNA

Coding DNA

- Ct

Cycle threshold

- CT

Computed tomography

- DI

Deionized

- DMEM

Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- DOTA

1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid

- DOTATATE

DOTA-Tyr3-octrotate

- DOTATOC

DOTA-Tyr3-octrotide

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- HEK

Human embryonic kidney

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- HPLC

High performance liquid chromatography

- HPRT1

Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1

- i.v.

Intravenous

- IC50

Half maximal inhibitory concentration

- Ki

Inhibition constant

- MeCN

Acetonitrile

- mRNA

Messenger RNA

- natGa

Natural gallium

- NET

Neuroendocrine tumor

- NOD scid gamma

NOD.Cg-Prkdc scid Il2rg tm1Wjl/SzJ

- NODAGA

1,4,7-triazacyclononane,1-glutaric acid-4,7-acetic acid

- ns

Not significant

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- PR

Progesterone receptor

- PRRT

Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy

- qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- RPMI

Rosewell Park Memorial Institute

- SD

Standard deviation

- SPECT

Single photon emission computed tomography

- SRIF-28

Somatostatin-28

- Sstr1-5

Somatostatin receptor subtype 1–5

- SUV

Standard uptake value

- TEAP

Triethylammonium phosphate

- tR

Retention time

- Tris

2-Amino-2-hydroxymethyl-propane-1,3-diol

Contributor Information

Iulia Dude, Email: idude@bccrc.ca.

Zhengxing Zhang, Email: zzhang@bccrc.ca.

Julie Rousseau, Email: jrousseau@bccrc.ca.

Navjit Hundal-Jabal, Email: nhundal@bccrc.ca.

Nadine Colpo, Email: ncolpo@bccrc.ca.

Helen Merkens, Email: hmerkens@bccrc.ca.

Kuo-Shyan Lin, Email: klin@bccrc.ca.

François Bénard, Phone: 604-675-8206, Email: fbenard@bccrc.ca.

References

- Alberini JL, Meunier B, Denzler B, Devillers A, Tass P, Dazord L, et al. Somatostatin receptor in breast cancer and axillary nodes: study with scintigraphy, histopathology and receptor autoradiography. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;61:21–32. doi: 10.1023/A:1006447325077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt P, Kolby L, Johanson V, Nilsson O, Ahlman H, Forssell-Aronsson E. Biodistribution of 111in-DTPA-D-Phe1-octreotide in tumor-bearing nude mice: influence of amount injected and route of administration. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:253–260. doi: 10.1016/S0969-8051(02)00417-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootsma AH, van Eijck C, Schouten KK, Reubi JC, Waser B, Foekens JA, et al. Somatostatin receptor-positive primary breast tumors: genetic, patient and tumor characteristics. Int J Cancer. 1993;54:357–362. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910540302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cescato R, Waser B, Fani M, Reubi JC. Evaluation of 177Lu-DOTA-sst2 antagonist versus 177Lu-DOTA-sst2 agonist binding in human cancers in vitro. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1886–1890. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.095778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciocca DR, Puy LA, Fasoli LC, Tello O, Aznar JC, Gago FE, et al. Corticotropin-releasing hormone, luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone, growth hormone-releasing hormone, and somatostatin-like immunoreactivities in biopsies from breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1990;15:175–184. doi: 10.1007/BF01806354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalm SU, Sieuwerts AM, Look MP, Melis M, van Deurzen CH, Foekens JA, et al. Clinical Relevance of Targeting the Gastrin-Releasing Peptide Receptor, Somatostatin Receptor 2, or Chemokine C-X-C Motif Receptor 4 in Breast Cancer for Imaging and Therapy. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1487–1493. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.160739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalm SU, Melis M, Emmering J, Kwekkeboom DJ, de Jong M. Breast cancer imaging using radiolabelled somatostatin analogues. Nucl Med Biol. 2016;43:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong M, Breeman WA, Bernard BF, van Gameren A, de Bruin E, Bakker WH, et al. Tumour uptake of the radiolabelled somatostatin analogue [DOTA0, TYR3]octreotide is dependent on the peptide amount. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999;26:693–698. doi: 10.1007/s002590050439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgeti F, Amthauer H, Denecke T, Steffen I, Heuck F, Stelter L, et al. Incidental detection of breast cancer by 68Ga-DOTATOC-PET/CT in women suffering from neuroendocrine tumours. Nuklearmedizin. 2008;47:261–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AA, Crook T, Laws SA, Gough AC, Royle GT, Primrose JN. Analysis of somatostatin receptor subtype mRNA expression in human breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:798–803. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fani M, Del Pozzo L, Abiraj K, Mansi R, Tamma ML, Cescato R, et al. PET of somatostatin receptor-positive tumors using 64Cu- and 68Ga-somatostatin antagonists: the chelate makes the difference. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1110–1118. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.087999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fani M, Maecke HR, Okarvi SM. Radiolabeled peptides: valuable tools for the detection and treatment of cancer. Theranostics. 2012;2:481–501. doi: 10.7150/thno.4024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fani M, Braun F, Waser B, Beetschen K, Cescato R, Erchegyi J, et al. Unexpected sensitivity of sst2 antagonists to N-terminal radiometal modifications. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1481–1489. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.102764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foekens JA, Portengen H, van Putten WL, Trapman AM, Reubi JC, Alexieva-Figusch J, et al. Prognostic value of receptors for insulin-like growth factor 1, somatostatin, and epidermal growth factor in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1989;49:7002–7009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frati A, Rouzier R, Lesieur B, Werkoff G, Antoine M, Rodenas A, et al. Expression of somatostatin type-2 and −4 receptor and correlation with histological type in breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:3997–4003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froidevaux S, Eberle AN, Christe M, Sumanovski L, Heppeler A, Schmitt JS, et al. Neuroendocrine tumor targeting: study of novel gallium-labeled somatostatin radiopeptides in a rat pancreatic tumor model. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:930–937. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gakhar G, Wight-Carter M, Andrews G, Olson S, Nguyen TA. Hydronephrosis and urine retention in estrogen-implanted athymic nude mice. Vet Pathol. 2009;46:505–508. doi: 10.1354/vp.08-VP-0180-N-BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginj M, Zhang H, Waser B, Cescato R, Wild D, Wang X, et al. Radiolabeled somatostatin receptor antagonists are preferable to agonists for in vivo peptide receptor targeting of tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16436–16441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607761103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppeler A, Froidevaux S, Mäcke HR, Jermann E, Béhé M, Powell P, et al. Radiometal-Labelled Macrocyclic Chelator-Derivatised Somatostatin Analogue with Superb Tumour-Targeting Properties and Potential for Receptor-Mediated Internal Radiotherapy. Chem Eur J. 1999;5:1974–1981. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3765(19990702)5:7<1974::AID-CHEM1974>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ingberg E, Theodorsson A, Theodorsson E, Strom JO. Methods for long-term 17beta-estradiol administration to mice. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2012;175:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara T, Nakamura S, Kaziro Y, Takahashi T, Takahashi K, Nagata S. Molecular cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding the secretin receptor. EMBO J. 1991;10:1635–1641. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07686.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T. Differences between natural and recombinant G protein-coupled receptor systems with varying receptor/G protein stoichiometry. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18:456–464. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(97)90683-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenning EP, Kwekkeboom DJ, Bakker WH, Breeman WA, Kooij PP, Oei HY, et al. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy with [111In-DTPA-D-Phe1]- and [123I-Tyr3]-octreotide: the Rotterdam experience with more than 1000 patients. Eur J Nucl Med. 1993;20:716–731. doi: 10.1007/BF00181765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar U, Grigorakis SI, Watt HL, Sasi R, Snell L, Watson P, et al. Somatostatin receptors in primary human breast cancer: quantitative analysis of mRNA for subtypes 1–5 and correlation with receptor protein expression and tumor pathology. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;92:175–186. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-2414-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan ML, Kushi LH, Weltzien E, Maring B, Kutner SE, Fulton RS, et al. Epidemiology of breast cancer subtypes in two prospective cohort studies of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/bcr2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwekkeboom DJ, Kam BL, van Essen M, Teunissen JJ, van Eijck CH, Valkema R, et al. Somatostatin-receptor-based imaging and therapy of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:R53–R73. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin KS, Pan J, Amouroux G, Turashvili G, Mesak F, Hundal-Jabal N, et al. In vivo radioimaging of bradykinin receptor b1, a widely overexpressed molecule in human cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75:387–393. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maecke HR, Reubi JC. Somatostatin receptors as targets for nuclear medicine imaging and radionuclide treatment. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:841–844. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.084236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milani A, Geuna E, Mittica G, Valabrega G. Overcoming endocrine resistance in metastatic breast cancer: Current evidence and future directions. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5:990–1001. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i5.990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas G, Kaul F, Mena R, Bouterfa H, Fani M, Wild D. First clinical data on 68Ga-labeled somatostatin receptor antagonists: a phase I/II study comparing 68Ga-OPS202 with 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:266. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas G, Schreiter N, Kaul F, Uiters J, Mena R, Bouterfa H, et al. PET/CT with the somatostatin receptor antagonist 68Ga-OPS202 is twice as accurate as with the agonist 68Ga-DOTATOC for detecting liver metastases: Results of a phase 1/2 study in gastroenteropancreatic NET patients. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:154. [Google Scholar]

- Notni J, Steiger K, Hoffmann F, Reich D, Kessler H, Schwaiger M, et al. Variation of Specific Activities of Ga-68-Aquibeprin and Ga-68-Avebetrin Enables Selective PET-Imaging of Different Expression Levels of Integrins α5β1 and αvβ3. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1618-24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Poeppel TD, Binse I, Petersenn S, Lahner H, Schott M, Antoch G, et al. 68Ga-DOTATOC versus 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT in functional imaging of neuroendocrine tumors. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1864–1870. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.091165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubi JC. Peptide receptors as molecular targets for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:389–427. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubi JC, Torhorst J. The relationship between somatostatin, epidermal growth factor, and steroid hormone receptors in breast cancer. Cancer. 1989;64:1254–1260. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890915)64:6<1254::AID-CNCR2820640615>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubi JC, Waser B, Foekens JA, Klijn JG, Lamberts SW, Laissue J. Somatostatin receptor incidence and distribution in breast cancer using receptor autoradiography: relationship to EGF receptors. Int J Cancer. 1990;46:416–420. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910460315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubi JC, Schär J-C, Waser B, Wenger S, Heppeler A, Schmitt JS, et al. Affinity profiles for human somatostatin receptor subtypes SST1–SST5 of somatostatin radiotracers selected for scintigraphic and radiotherapeutic use. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27:273–282. doi: 10.1007/s002590050034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubi JC, Waser B, Schaer JC, Laissue JA. Somatostatin receptor sst1-sst5 expression in normal and neoplastic human tissues using receptor autoradiography with subtype-selective ligands. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:836–846. doi: 10.1007/s002590100541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubi C, Gugger M, Waser B. Co-expressed peptide receptors in breast cancer as a molecular basis for in vivo multireceptor tumour targeting. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:855–862. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0794-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaer JC, Waser B, Mengod G, Reubi JC. Somatostatin receptor subtypes sst1, sst2, sst3 and sst5 expression in human pituitary, gastroentero-pancreatic and mammary tumors: comparison of mRNA analysis with receptor autoradiography. Int J Cancer. 1997;70:530–537. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970304)70:5<530::AID-IJC7>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz S, Schulz S, Schmitt J, Wiborny D, Schmidt H, Olbricht S, et al. Immunocytochemical detection of somatostatin receptors sst1, sst2A, sst2B, and sst3 in paraffin-embedded breast cancer tissue using subtype-specific antibodies. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:2047–2052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strosberg J, Wolin E, Chasen B, Kulke M, Bushnell D, Caplin M, et al. NETTER-1 Phase III in Patients with Midgut Neuroendocrine Tumors Treated with 177Lu-Dotatate: Efficacy and Safety Results. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:629. [Google Scholar]

- Subik K, Lee J-F, Baxter L, Strzepek T, Costello D, Crowley P, et al. The Expression Patterns of ER, PR, HER2, CK5/6, EGFR, Ki-67 and AR by Immunohistochemical Analysis in Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Breast Cancer (Auckl) 2010;4:35–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eijck CH, Krenning EP, Bootsma A, Oei HY, van Pel R, Lindemans J, et al. Somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy in primary breast cancer. Lancet. 1994;343:640–643. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92637-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikic-Topic S, Raisch KP, Kvols LK, Vuk-Pavlovic S. Expression of somatostatin receptor subtypes in breast carcinoma, carcinoid tumor, and renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:2974–2979. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.10.7559883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadas TJ, Eiblmaier M, Zheleznyak A, Sherman CD, Ferdani R, Liang K, et al. Preparation and biological evaluation of 64Cu-CB-TE2A-sst2-ANT, a somatostatin antagonist for PET imaging of somatostatin receptor-positive tumors. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1819–1827. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.054502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Wang Z, Wu J, Qu W, Yao W, Zhao J, et al. The role of technetium-99 m-labeled octreotide acetate scintigraphy in suspected breast cancer and correlates with expression of SSTR. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35:665–671. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild D, Fani M, Behe M, Brink I, Rivier JE, Reubi JC, et al. First clinical evidence that imaging with somatostatin receptor antagonists is feasible. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1412–1417. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.088922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild D, Fani M, Fischer R, Del Pozzo L, Kaul F, Krebs S, et al. Comparison of somatostatin receptor agonist and antagonist for peptide receptor radionuclide therapy: a pilot study. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:1248–1252. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.138834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental information. Figure S1. Representative standard curve for absolute quantification qPCR experiments. Table S1. Standard curve parameters. Table S2. PCR Cycling conditions. Table S3. qPCR Cycling conditions. (DOCX 38 kb)