Abstract

Autophagy is a well-known intracellular degradation process involved in clearing damaged or unnecessary components in cells. Functional autophagy is important for cardiac homeostasis. Given this, it is not surprising that dysregulation of autophagy has been implicated in the aging process and in various cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, understanding the functional role of autophagy in the heart under various conditions and whether manipulation of the pathway has therapeutic benefits have been a major focus of many investigations in recent years. Although consensus exists that autophagy is a critical cellular quality control pathway in the heart, its role in disease remains controversial. Whether altered autophagy is protective or detrimental in the heart seems to depend on the context and the disease. Here, we review the latest insights into autophagy in cardiovascular homeostasis and disease and its role in disease development.

Keywords: Autophagy, heart disease, aging, diabetes

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease remains the number one contributor to mortality worldwide, with over 17.3 million deaths per year [1]. Thus, there is a great need for a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying development of cardiovascular disease to prevent the progression to heart failure. Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) is an intracellular degradation process that is altered in various diseases of the heart. The autophagy related genes (Atg) and the various signal transduction pathways involved in autophagy initiation and progression have been well-summarized in recent reviews [2–4].

Autophagy is responsible for degrading long-lived proteins and dysfunctional or excess organelles [2]. Under conditions of stress such as nutrient or oxygen deprivation, autophagy is also involved in generating energy substrates to meet metabolic demand and in eliminating cytotoxic protein aggregates and organelles. However, excessive and chronic autophagic activation can lead to depletion of essential proteins and organelles, which can trigger cell death. Dysregulation of autophagy contributes to the pathology of many diseases, including cardiovascular diseases. In this review, we discuss the latest developments and current concepts of autophagy in cardiovascular homeostasis and disease, and how perturbation in the pathway contributes to disease development.

Autophagy in Cardiac Homeostasis and Aging

The heart consists of post-mitotic cardiac myocytes and functional autophagy is essential to maintain myocyte function and viability with age. Not surprisingly, selective disruption of autophagy in mouse hearts led to accumulation of defective proteins and organelles and cardiac dysfunction [5]. Similarly, patients with Danon disease, an X-linked genetic disorder characterized by a mutation in the gene encoding lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2), have impaired autophagic flux and develop severe and progressive lethal cardiomyopathy [6]. Characterization of iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes from patients with Danon disease confirmed that the cells exhibited impaired autophagic flux, abnormal calcium handling, enhanced oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage [7**]. Impaired mitochondrial autophagy was also observed in a mouse model of Danon disease, suggesting that diminished mitochondrial clearance may be a central component of the disease [8].

Autophagic activity is reduced with age in tissues, including the heart [2,5]. Therefore, it is not surprising that reduced autophagy leads to accelerated cardiac aging [5] and interventions that enhance autophagy preserve cardiac function and extend life span in various organisms [9–12]. Selective disruption of autophagy in the heart led to reduced life span in mice [5]. In contrast, enhancing autophagic flux in the heart with the dietary compound polyamine spermidine reduced the decline in cardiac function observed in aged mice and extended life span [9**]. These beneficial effects were abrogated in cardiac specific autophagy deficient mice, confirming that the cardioprotective effects were dependent on autophagy [9**]. Similarly, administration of rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR and activator of autophagy, reversed age-related cardiac hypertrophy and decline in function in mice by improving energy metabolism [13**]. Clearly, autophagy plays an important role in rejuvenating myocytes. However, many of the treatments to enhance autophagy in those experiments also affect other pathways, making it difficult to discern how much enhanced autophagy contributes to delaying aging.

Autophagy in myocardial infarction and ischemia/reperfusion injury

Autophagy plays important roles in: 1) maintaining energy homeostasis during nutrient limiting conditions and 2) cellular quality control by eliminating damaged proteins and organelles. Limited availability of oxygen and nutrients during myocardial ischemia are potent activators of autophagy as an attempt to maintain energy levels to meet metabolic demands in the myocytes. Subsequent restoration of oxygen during reperfusion can cause intracellular damage which also activates autophagy. Although autophagy is activated during both ischemia and reperfusion for different purposes, whether targeting autophagy in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) is beneficial or detrimental has been the focus of intensive investigation and subject to much debate. The exact role of autophagy in this context remains unclear.

Studies agree that autophagy is induced during ischemia and further increased during reperfusion [14,15]. It was initially reported that the enhanced autophagic activity during acute ischemia/reperfusion served a protective role [16]. Many additional studies have reported a protective role for autophagy in I/R injury in cells and animal models [17,18]. Tibetian patients living at high altitude and subjected to chronic hypoxia had enhanced basal autophagy based on increased levels of autophagy proteins in their hearts [19*]. Notably, these patients had reduced cardiac damage compared with patients living at sea level after exposure to I/R during a cardiopulmonary bypass surgery, indicating that enhanced autophagy at baseline is cardioprotective. In addition, reperfusion can trigger excessive activation of autophagy which is detrimental to the heart [20], although this may depend on the length of the ischemia [21*]. Reducing autophagy levels to baseline with the alkaloid berberine during reperfusion decreased myocardial reperfusion injury [22]. The function of autophagy also varied with the duration of ischemia and reperfusion phases, where autophagy was beneficial when myocytes were subjected to mild to moderate ischemia but became detrimental when ischemia was prolonged [21*]. Overall, autophagy appears to be mainly an adaptive response that protects myocytes during stress. However, Wang et al. reported that abrogation of autophagy in vitro and in vivo protected against I/R, linking autophagy to cell death and injury [23]. Clearly, excessive stress or damage will lead to chronic or over activation of autophagy leading to excess degradation. Further studies are required to identify the mechanisms that define the outcome of the critical equilibrium existing between beneficial and maladaptive autophagy in I/R. It is likely that the conflicting results are due to differences in experimental design such as length of ischemia, genetic or pharmacological targeting of the autophagy pathway, and in mouse strains and species used.

Autophagy in Cardiac Hypertrophy

Baseline autophagy suppresses development of cardiac hypertrophy as early studies observed that disruption of autophagy in mouse hearts led to development of cardiac hypertrophy [24,25]. Autophagic activity is also altered in response to hypertrophic stimuli. In response to hemodynamic overload, the heart undergoes hypertrophy as an adaptive response to reduce wall stress, which can progress to pathological hypertrophy and heart failure if unresolved. There is currently little consensus on the role of autophagy during pressure overload. Studies agree that autophagy is activated during cardiac hypertrophy, but disagree on the length of activation and whether it is protective or detrimental to the heart [24,26,27]. Zhu et al. initially observed that Beclin1 haploinsufficient mice had reduced autophagy and pathological remodeling after transverse aortic constriction (TAC) [26]. In contrast, Beclin1 transgenic mice had enhanced pathological remodeling, indicating a maladaptive role for autophagy. However, it is important to take into account that Beclin1 might regulate other cellular processes than autophagy that might account for the phenotype observed in these mice. A recent study reported that Beclin1 also regulates the endosome pathway [28].

More recent studies have reported that restoring autophagy exerts protection against cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in response to TAC [29,30]. A detailed time course analysis revealed that autophagy was only transiently activated immediately after TAC but suppressed in the chronic phase [30**]. Also, increasing autophagic flux using TB1, a peptide derived from Beclin1, attenuated TAC-mediated cardiac dysfunction, suggesting that enhancing autophagy was protective. The acute activation of autophagy is most likely an adaptive response to the stress. However, to facilitate the initiation of hypertrophy, degradation pathways must be turned off to allow the myocytes to grow. Thus, the transient activation of autophagy is consistent with the fact that autophagy needs to be turned off to allow the myocyte to grow. Cheng et al. recently confirmed this by demonstrating that phenylephrine, a potent inducer of hypertrophy, suppressed autophagy which was required for the subsequent initiation of hypertrophic growth [31*].

Interestingly, it was observed that DNA-damage inducible transcript 4-like was upregulated in pathological, but not in physiological, hypertrophy and that its primary function was to inhibit pathological hypertrophy by increasing basal autophagy and promoting atrophy [32**]. Finally, Hsp27 transgenic mice develop cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure within four weeks after birth. Autophagic activity is enhanced in these hearts in both the adaptive and maladaptive stages [33*]. Suppressing autophagy pharmacologically alleviated the cardiac dysfunction observed in the transgenic mice, confirming that persistent activation of autophagy was detrimental under these circumstances [33*]. Overall, these findings suggest an important role for autophagy both in adaptation and in the regulation of cardiac growth. However, its functional role in hypertrophy clearly depends on the stimuli. Taken together, each of these studies demonstrate how extended autophagy activation can contribute to negative consequences for the heart in models of heart failure.

Autophagy and Anthracycline-Mediated Cardiotoxicity

Anthracyclines, such as doxorubicin, are potent chemotherapeutic agents but their use is limited due to cardiotoxicity [34]. Several studies have investigated the role of autophagy in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity and there is emerging consensus that enhancing autophagy prior to doxorubicin exposure is cardioprotective [35–37]. However, doxorubicin abrogates autophagy in myocytes, but studies disagree on the underlying mechanism. Autophagosomes accumulate in the heart after doxorubicin exposure [35,37,38] and a recent study reported that doxorubicin impaired lysosomal acidification which caused autophagosomes to accumulate in myocytes [37**]. This study found that reduced autophagy in Beclin1+/− mice protected from doxorubicin-induced cardiac damage, whereas overexpression of Beclin1 exacerbated cardiotoxicity [37**]. This suggests that the accumulation of autophagosomes contributes to the cardiotoxicity observed with doxorubicin. In contrast, Pizarro et al. reported that doxorubicin exposure inhibited formation of autophagosomes by activation of mTOR in myocytes [36], implicating altered autophagy signaling in the toxicity rather than accumulating autophagosomes. Clearly, doxorubicin-induced toxicity and its effect on autophagy is a complex and not fully understood process. Additional studies are needed to uncover exactly how doxorubicin alters autophagic activity and its consequences on cardiomyocyte viability.

Autophagy and diabetic cardiomyopathy

Diabetes mellitus (DM)-related cardiomyopathy is a major cause of heart failure in diabetic patients [39]. The mechanisms underlying its pathogenesis remain unclear and etiological differences between type 1 and type 2 diabetes have complicated studies attempting to elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Recent studies have focused on how autophagic activity in the heart is altered with diabetes and in diabetic cardiomyopathy.

As insulin signaling inhibits autophagy by activating mTOR, it is anticipated that impaired insulin production would lead to enhanced autophagy. Consistent with this notion, a study recently reported that autophagic activity was increased in hearts from streptozotocin (STZ)-induced type 1 diabetic mice. Inhibiting autophagy exacerbated cardiac dysfunction and injury [40*], suggesting that the enhanced autophagy was cardioprotective. Similarly, enhancing autophagy with fenofibrate, a peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor α agonist, was also cardioprotective in the STZ type 1 diabetic mice [41]. However, another study reported that autophagy was inhibited in hearts of OVE26 type 1 diabetic mice [42]. This study also found that restoring autophagic flux reduced cardiac injury, confirming that enhancing autophagy is cardioprotective in type 1 diabetes. A different study observed reduced cardiac autophagy in type 1 diabetic hearts which functioned to limit cardiac injury. Cardiac damage was attenuated in type 1 diabetic autophagy deficient mice, while enhancing autophagic activity aggravated cardiac damage [43]. In summary, recent studies report both increased and decreased baseline autophagic activity in the hearts of type 1 diabetic mouse models, and that modulating autophagy can either protect or exacerbate cardiac damage. Clearly, additional studies are needed to uncover the function of autophagy in type 1 diabetes and whether modulating it is beneficial or detrimental for the heart.

Although it is expected that the excess intracellular nutrient status in type 2 diabetes would lead to suppression of autophagy, reports on autophagic activity and function are conflicting in type 2 diabetes. For instance, autophagy was reported to be suppressed in hearts of db/db diabetic mice [40*] and in high-fat-diet-induced obesity mice [44]. Also, pharmacological manipulation to enhance autophagy using resveratrol restored cardiac diastolic function, while inhibition of autophagy using chloroquine worsened cardiac function in the db/db diabetic mice [40*]. In contrast, cardiac autophagic activity has been reported to be unchanged in mice fed a high fat diet [45] or activated in mice by fructose-induced insulin resistance and hyperglycemia [46]. Moreover, Munasinghe et al. reported increased levels of autophagy proteins in the right atria of human type 2 diabetic heart patients [47]. The different results in these studies can partly be attributed to variation in the diet duration and composition (carbohydrates and lipids) and in the duration. Also, it is clear that evaluating autophagy in animal models may not accurately reflect the more complex environment in a patient. Overall, these studies highlight the complexity of autophagy in diabetes and further studies will need to determine how autophagy is altered in type 2 diabetes and whether data obtained in mouse models will translate to human patients.

Conclusion

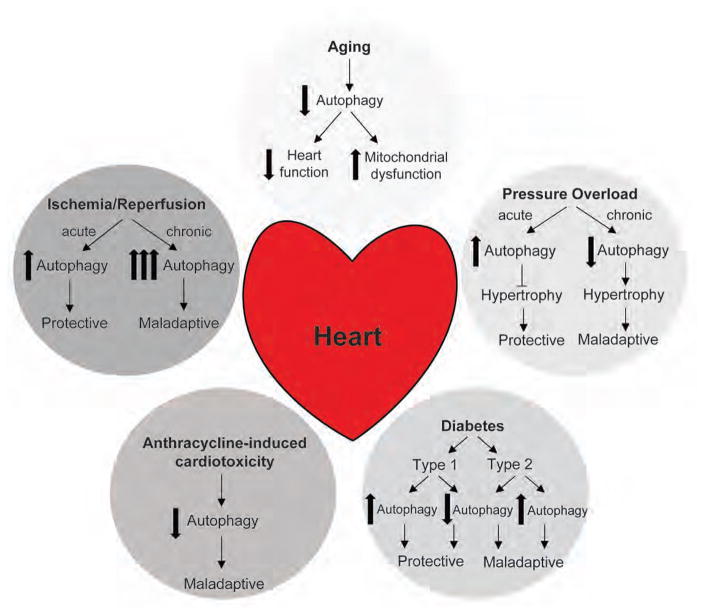

In the past decade, numerous studies have been designed to dissect the pathways governing autophagic activation, flux, and lysosomal processing, and to determine the functional implications of changes in autophagic pathways (Figure 1). However, the precise role of autophagy in various cardiac pathologies remains unclear and clearly warrants further investigation. Several key questions that remain unanswered include: 1) When does autophagy switch from beneficial to detrimental in I/R injury and what are the signaling pathways involved in regulating this switch? 2) Does autophagy play a different function depending on the disease? If so, did the function change with the stage and/or severity of the disease? 3) Is autophagy also altered in fibroblasts, endothelial cells and inflammatory cells in cardiovascular diseases? Most studies to date have focused on autophagy in myocytes but other cell types in the heart also contribute to disease development. Finally, development of specific pharmacological modulators of autophagy are also needed to help better understand the role of autophagy in the heart. It is clear that additional investigations are necessary to fully understand the function of autophagy in various cardiovascular diseases before this pathway can be considered as a therapeutic target.

Figure 1. Effect of aging and cardiovascular diseases on cardiac autophagy and its functional consequences on the heart.

Autophagy plays a complex role in aging and cardiovascular disease as discussed in this review. Deregulation in autophagic activity contributes to disease progression and is altered in a variety of cardiac maladies.

Highlights.

Functional autophagy is important for cardiac homeostasis

Dysregulation of autophagy contributes to the pathology of many cardiovascular diseases

The specific contribution of altered autophagy in various cardiac pathologies remains unclear and is still controversial

Acknowledgments

Funding

Å.B. Gustafsson is supported by an AHA Established Investigator Award, and by NIH R21AG052280, R01HL087023, R01HL132300 and P01HL085577. M.A. Lampert is supported by the UCSD Graduate Training Program in Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology grant T32GM007752.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Floyd J, Fornage M, Gillespie C, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shirakabe A, Ikeda Y, Sciarretta S, Zablocki DK, Sadoshima J. Aging and Autophagy in the Heart. Circ Res. 2016;118:1563–1576. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galluzzi L, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Levine B, Green DR, Kroemer G. Pharmacological modulation of autophagy: therapeutic potential and persisting obstacles. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yin Z, Pascual C, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: machinery and regulation. Microb Cell. 2016;3:588–596. doi: 10.15698/mic2016.12.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taneike M, Yamaguchi O, Nakai A, Hikoso S, Takeda T, Mizote I, Oka T, Tamai T, Oyabu J, Murakawa T, et al. Inhibition of autophagy in the heart induces age-related cardiomyopathy. Autophagy. 2010;6:600–606. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.5.11947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maron BJ, Roberts WC, Arad M, Haas TS, Spirito P, Wright GB, Almquist AK, Baffa JM, Saul JP, Ho CY, et al. Clinical outcome and phenotypic expression in LAMP2 cardiomyopathy. JAMA. 2009;301:1253–1259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7**.Hashem SI, Perry CN, Bauer M, Han S, Clegg SD, Ouyang K, Deacon DC, Spinharney M, Panopoulos AD, Izpisua Belmonte JC, et al. Brief Report: Oxidative Stress Mediates Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis in a Human Model of Danon Disease and Heart Failure. Stem Cells. 2015;33:2343–2350. doi: 10.1002/stem.2015. This paper demonstrates that the impaired autophagic flux in iPSC derived cardiomyocytes from patients with Danon Disease results in increased oxidative stress, abnormal calcium handling, and cell death. It is one of the first papers to provide mechanistic evidence of how impairment of autophagic flux in Danon disease patients leads to cardiomyocyte cell death. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashem SI, Murphy AN, Divakaruni AS, Klos ML, Nelson BC, Gault EC, Rowland TJ, Perry CN, Gu Y, Dalton ND, et al. Impaired mitophagy facilitates mitochondrial damage in Danon disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017;108:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9**.Eisenberg T, Abdellatif M, Schroeder S, Primessnig U, Stekovic S, Pendl T, Harger A, Schipke J, Zimmermann A, Schmidt A, et al. Cardioprotection and lifespan extension by the natural polyamine spermidine. Nat Med. 2016;22:1428–1438. doi: 10.1038/nm.4222. This article is notable for linking enhanced autophagy with the extension of lifespan in mice. Supplementation with the polyamine spermidine also produced cardioprotective effects and represents an intriguing new therapeutic option to prevent development of age-related heart disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen M, Chandra A, Mitic LL, Onken B, Driscoll M, Kenyon C. A role for autophagy in the extension of lifespan by dietary restriction in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e24. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melendez A, Talloczy Z, Seaman M, Eskelinen EL, Hall DH, Levine B. Autophagy genes are essential for dauer development and life-span extension in C. elegans. Science. 2003;301:1387–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.1087782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai DF, Karunadharma PP, Chiao YA, Basisty N, Crispin D, Hsieh EJ, Chen T, Gu H, Djukovic D, Raftery D, et al. Altered proteome turnover and remodeling by short-term caloric restriction or rapamycin rejuvenate the aging heart. Aging Cell. 2014;13:529–539. doi: 10.1111/acel.12203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13**.Chiao YA, Kolwicz SC, Basisty N, Gagnidze A, Zhang J, Gu H, Djukovic D, Beyer RP, Raftery D, MacCoss M, et al. Rapamycin transiently induces mitochondrial remodeling to reprogram energy metabolism in old hearts. Aging (Albany NY) 2016;8:314–327. doi: 10.18632/aging.100881. This paper demonstrates the beneficial effects of activating autophagy through mTOR inhibition in reversing diastolic dysfunction in aged mice. Importantly, the results indicate that the transient activation of autophagy and increased mitochondrial biogenesis leads to rejuvenated mitochondrial homeostasis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurusamy N, Lekli I, Gorbunov NV, Gherghiceanu M, Popescu LM, Das DK. Cardioprotection by adaptation to ischaemia augments autophagy in association with BAG-1 protein. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:373–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00495.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR, Logue SE, Sayen MR, Jinno M, Kirshenbaum LA, Gottlieb RA, Gustafsson AB. Response to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury involves Bnip3 and autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:146–157. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR, Gottlieb RA. Enhancing macroautophagy protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29776–29787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603783200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen-Scarabelli C, Agrawal PR, Saravolatz L, Abuniat C, Scarabelli G, Stephanou A, Loomba L, Narula J, Scarabelli TM, Knight R. The role and modulation of autophagy in experimental models of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2014;11:338–348. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie M, Kong Y, Tan W, May H, Battiprolu PK, Pedrozo Z, Wang ZV, Morales C, Luo X, Cho G, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibition blunts ischemia/reperfusion injury by inducing cardiomyocyte autophagy. Circulation. 2014;129:1139–1151. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19*.Hu Y, Sun Q, Li Z, Chen J, Shen C, Song Y, Zhong Q. High basal level of autophagy in high-altitude residents attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:1674–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.03.038. This article demonstrates in a unique study that those living with chronic hypoxia at high altitude have higher basal levels of cardiac autophagy and are more protected from ischemia/reperfusion cardiac injury. It provides exciting clinical evidence of the beneficial effects of autophagy in ischemia/reperfusion injury. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsui Y, Takagi H, Qu X, Abdellatif M, Sakoda H, Asano T, Levine B, Sadoshima J. Distinct roles of autophagy in the heart during ischemia and reperfusion: roles of AMP-activated protein kinase and Beclin 1 in mediating autophagy. Circ Res. 2007;100:914–922. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000261924.76669.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21*.Xu Q, Li X, Lu Y, Shen L, Zhang J, Cao S, Huang X, Bin J, Liao Y. Pharmacological modulation of autophagy to protect cardiomyocytes according to the time windows of ischaemia/reperfusion. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:3072–3085. doi: 10.1111/bph.13111. This paper reports that the effect of autophagy on the heart in response to ischemia/reperfusion injury is time and context-dependent. This is especially to important to consider in clinical contexts for selecting the proper autophagy-modulating therapeutics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang Z, Han Z, Ye B, Dai Z, Shan P, Lu Z, Dai K, Wang C, Huang W. Berberine alleviates cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting excessive autophagy in cardiomyocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;762:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang K, Liu CY, Zhou LY, Wang JX, Wang M, Zhao B, Zhao WK, Xu SJ, Fan LH, Zhang XJ, et al. APF lncRNA regulates autophagy and myocardial infarction by targeting miR-188-3p. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6779. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakai A, Yamaguchi O, Takeda T, Higuchi Y, Hikoso S, Taniike M, Omiya S, Mizote I, Matsumura Y, Asahi M, et al. The role of autophagy in cardiomyocytes in the basal state and in response to hemodynamic stress. Nat Med. 2007;13:619–624. doi: 10.1038/nm1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaber N, Dou Z, Chen JS, Catanzaro J, Jiang YP, Ballou LM, Selinger E, Ouyang X, Lin RZ, Zhang J, et al. Class III PI3K Vps34 plays an essential role in autophagy and in heart and liver function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2003–2008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112848109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu H, Tannous P, Johnstone JL, Kong Y, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Le V, Levine B, Rothermel BA, Hill JA. Cardiac autophagy is a maladaptive response to hemodynamic stress. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1782–1793. doi: 10.1172/JCI27523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao TT, Chen HH, Dong Z, Xu YW, Zhao P, Guo W, Wei HC, Zhang C, Lu R. Stachydrine Protects Against Pressure Overload-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy by Suppressing Autophagy. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;42:103–114. doi: 10.1159/000477119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKnight NC, Zhong Y, Wold MS, Gong S, Phillips GR, Dou Z, Zhao Y, Heintz N, Zong WX, Yue Z. Beclin 1 is required for neuron viability and regulates endosome pathways via the UVRAG-VPS34 complex. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu B, Wu Z, Li Y, Ou C, Huang Z, Zhang J, Liu P, Luo C, Chen M. Puerarin prevents cardiac hypertrophy induced by pressure overload through activation of autophagy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;464:908–915. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30**.Shirakabe A, Zhai P, Ikeda Y, Saito T, Maejima Y, Hsu CP, Nomura M, Egashira K, Levine B, Sadoshima J. Drp1-Dependent Mitochondrial Autophagy Plays a Protective Role Against Pressure Overload-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Heart Failure. Circulation. 2016;133:1249–1263. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020502. This paper establishes the important role of mitochondrial autophagy in maintaining proper cardiac health in a pressure overload model of cardiac hypertrophy. Notably, an increase in autophagy is shown to be cardioprotective and amerliorate mitochondrial dysfunction. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31*.Cheng Z, Zhu Q, Dee R, Opheim Z, Mack CP, Cyr DM, Taylor JM. Focal Adhesion Kinase-mediated Phosphorylation of Beclin1 Protein Suppresses Cardiomyocyte Autophagy and Initiates Hypertrophic Growth. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:2065–2079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.758268. This article demonstrates that suppression of autophagy in myocytes is necessary for hypertrophic cell growth. To do so, focal adhesion kinase (FAK) phosphorylates Beclin1 and suppresses downstream autophagosome formation for subsequent hypertrophic growth. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32**.Simonson B, Subramanya V, Chan MC, Zhang A, Franchino H, Ottaviano F, Mishra MK, Knight AC, Hunt D, Ghiran I, et al. DDiT4L promotes autophagy and inhibits pathological cardiac hypertrophy in response to stress. Sci Signal. 2017:10. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaf5967. The authors find that DNA-damage inducible transcript 4-like (DDiT4L) is upregulated in models of pathological hypertrophy but not in those of physiological hypertrophy. It provides mechanistic evidence that an increase in basal autophagy (through DDiT4L) promotes atrophy and decreases pathological hypertrophy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33*.Yu P, Zhang Y, Li C, Li Y, Jiang S, Zhang X, Ding Z, Tu F, Wu J, Gao X, et al. Class III PI3K-mediated prolonged activation of autophagy plays a critical role in the transition of cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure. J Cell Mol Med. 2015;19:1710–1719. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12547. This paper provides support to the notion that increased and sustained autophagy is associated with pathological progression from cardiac hypertrophy into heart failure. Suppression of PI3-k is shown to prevent progression to heart failure and could have significant clinical applications. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGowan JV, Chung R, Maulik A, Piotrowska I, Walker JM, Yellon DM. Anthracycline Chemotherapy and Cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2017;31:63–75. doi: 10.1007/s10557-016-6711-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawaguchi T, Takemura G, Kanamori H, Takeyama T, Watanabe T, Morishita K, Ogino A, Tsujimoto A, Goto K, Maruyama R, et al. Prior starvation mitigates acute doxorubicin cardiotoxicity through restoration of autophagy in affected cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;96:456–465. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pizarro M, Troncoso R, Martinez GJ, Chiong M, Castro PF, Lavandero S. Basal autophagy protects cardiomyocytes from doxorubicin-induced toxicity. Toxicology. 2016;370:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37**.Li DL, Wang ZV, Ding G, Tan W, Luo X, Criollo A, Xie M, Jiang N, May H, Kyrychenko V, et al. Doxorubicin Blocks Cardiomyocyte Autophagic Flux by Inhibiting Lysosome Acidification. Circulation. 2016;133:1668–1687. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017443. These authors uncover that doxorubicin exposure leads to impaired lysosomal degradation in the heart. Also, reducing initiation of autophagy decreased doxorubicin-mediated toxicity indicating that accumulating autophagosomes are harmful to myocytes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.An L, Hu XW, Zhang S, Hu X, Song Z, Naz A, Zi Z, Wu J, Li C, Zou Y, et al. UVRAG Deficiency Exacerbates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43251. doi: 10.1038/srep43251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kasznicki J, Drzewoski J. Heart failure in the diabetic population - pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:546–556. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2014.43748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40*.Kanamori H, Takemura G, Goto K, Tsujimoto A, Mikami A, Ogino A, Watanabe T, Morishita K, Okada H, Kawasaki M, et al. Autophagic adaptations in diabetic cardiomyopathy differ between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Autophagy. 2015;11:1146–1160. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1051295. This article reports that cardiac autophagy is increased in type 1 diabetes, whereas it is suppressed in type 2 diabetes. They also found that inhibiting autophagy in type 1 diabetes leads to an exacerbated cardiac phenotype while enhancing autophagy in Type 2 diabetes is cardioprotective. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J, Cheng Y, Gu J, Wang S, Zhou S, Wang Y, Tan Y, Feng W, Fu Y, Mellen N, et al. Fenofibrate increases cardiac autophagy via FGF21/SIRT1 and prevents fibrosis and inflammation in the hearts of Type 1 diabetic mice. Clin Sci (Lond) 2016;130:625–641. doi: 10.1042/CS20150623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie Z, Lau K, Eby B, Lozano P, He C, Pennington B, Li H, Rathi S, Dong Y, Tian R, et al. Improvement of cardiac functions by chronic metformin treatment is associated with enhanced cardiac autophagy in diabetic OVE26 mice. Diabetes. 2011;60:1770–1778. doi: 10.2337/db10-0351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu X, Kobayashi S, Chen K, Timm D, Volden P, Huang Y, Gulick J, Yue Z, Robbins J, Epstein PN, et al. Diminished autophagy limits cardiac injury in mouse models of type 1 diabetes. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:18077–18092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.474650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu X, Ren J. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) knockout preserves cardiac homeostasis through alleviating Akt-mediated myocardial autophagy suppression in high-fat diet-induced obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015;39:387–396. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.French CJ, Tarikuz Zaman A, McElroy-Yaggy KL, Neimane DK, Sobel BE. Absence of altered autophagy after myocardial ischemia in diabetic compared with nondiabetic mice. Coron Artery Dis. 2011;22:479–483. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e32834a3a71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mellor KM, Bell JR, Young MJ, Ritchie RH, Delbridge LM. Myocardial autophagy activation and suppressed survival signaling is associated with insulin resistance in fructose-fed mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:1035–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Munasinghe PE, Riu F, Dixit P, Edamatsu M, Saxena P, Hamer NS, Galvin IF, Bunton RW, Lequeux S, Jones G, et al. Type-2 diabetes increases autophagy in the human heart through promotion of Beclin-1 mediated pathway. Int J Cardiol. 2016;202:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.08.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]