SUMMARY

Protein glycosylation provides proteomic diversity in regulating protein localization, stability and activity; it remains largely unknown whether the sugar moiety contributes to immunosuppression. In the study of immune receptor glycosylation, we showed EGF induces PD-L1 and receptor programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) interaction, requiring β-1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase (B3GNT3) expression in triple-negative breast cancer. Downregulation of B3GNT3 enhances cytotoxic T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity. A monoclonal antibody targeting glycosylated PD-L1 (gPD-L1) blocks PD-L1/PD-1 interaction and promotes PD-L1 internalization and degradation. In addition to immune reactivation, drug-conjugated gPD-L1 antibody induces potent cell-killing effect as well as bystander-killing effect on adjacent cancer cells lacking PD-L1 expression without any detectable toxicity. Our work suggests targeting protein glycosylation as a potential strategy to enhance immune checkpoint therapy.

Keywords: Glycosylation, PD-L1, PD-1, B3GNT3, immunosuppression, antibody-drug conjugate, immune checkpoint blockade, TNBC, receptor internalization

eTOC Blurb

Li et al. show that glycosylation of PD-L1 is essential for PD-L1/PD-1 interaction and immunosuppression in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). They generate a glycosylation-specific antibody that induces PD-L1 internalization and an antibody-drug conjugate with potent anti-tumor activities in TNBC models.

INTRODUCTION

Evasion of immune surveillance by cancer cells is associated with suppression of CD8+ T cell proliferation, cytokine release, and cytolytic activity (Dong et al., 2002; Krummel and Allison, 1995). Immunoglobulin-like immunosuppressive molecules, such as programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1; also known as B7 homolog 1), are expressed on a wide range of cell types, including cancer cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and stromal cells (Curiel et al., 2003; Dong et al., 1999). PD-L1 on cancer cells interacts with PD-1 on T cells, enabling cancer cells to escape T cell-mediated immune surveillance (Dong et al., 2002). Thus, blocking PD-L1 and PD-1 interaction by monoclonal antibodies reactivates tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), which has shown promising clinical effects (Brahmer et al., 2010; Sznol and Chen, 2013). However, the response rate (RR) to PD-1 or PD-L1 antibody remains at about 15–30% as a single agent, and many patients who received anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 therapy are at risk of developing autoimmune disorders, such as Crohn’s disease, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis (Rosenberg et al., 2016). In particular, single agent RR in TNBC was 18.5% in Keynote 012 (Nanda et al., 2016), 5% regardless of PD-L1 expression in Keynote 086 (Adams et al., 2017), 8.6% in Javelin phase 1b (Dirix et al., 2016), and 26% atezolizumab 1b (Schmid et al., 2017) with acceptable safety profile. Thus, identifying new immune checkpoint targets to improve the efficacy or safety of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade therapy is urgently needed.

Aside from maintaining protein integrity, posttranslational modification via the addition of carbohydrates regulates various protein functions, including protein folding, trafficking, and protein-protein interactions (Schwarz and Aebi, 2011). Initiated in the endoplasmic reticulum, N-linked glycosylation is first catalyzed by oligosaccharyl transferase (OST) complex that transfers a preformed oligosaccharide to an asparagine (Asn) side-chain acceptor, followed by several trimming steps to ensure protein integrity. Further processing takes place in the Golgi apparatus via a sequential glycosidase- and glycotransferase-mediated glycoprotein biosynthesis (Asano, 2003). β-1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 3 (B3GNT3) is a type II transmembrane protein in the Golgi, and plays a role in the biosynthesis of poly-N-acetyllactosamine chains and generation of the backbone components of dimeric sialyl Lewis A (Hennet et al., 1998). B3GNT3 also regulates L-selectin ligand function, lymphocyte trafficking, and T cell homing (Yeh et al., 2001). Although B3GNT3 is overexpressed in the breast cancers (Shiraishi et al., 2001), its role in tumorigenesis is not well understood.

Interferon gamma (IFNγ)-mediated transcriptional regulation of PD-L1 via STAT or NF-κB is well established (Dong et al., 2002) and has been shown to contribute to anti-CTLA4 (Gao et al., 2016) and anti-PD-1 (Zaretsky et al., 2016) resistance. We reported that posttranslational modification of PD-L1 regulates cancer cell-mediated immunosuppression (Li et al., 2016a; Lim et al., 2016). Specifically, glycosylation of PD-L1 prevents glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) from phosphorylating and mediating PD-L1 degradation, which in turn stabilizes PD-L1 and suppresses cytotoxic T cell activity (Li et al., 2016a). However, whether and how glycosylation itself affects PD-L1/PD-1 interaction and immunosuppressive functions remain to be explored. Because glycosylation controls protein expression, folding, or trafficking (Cheung and Reithmeier, 2007), the study of carbohydrate regulation of PD-L1 may help identify biomarkers or develop combinatorial treatment strategies for clinical use (Pardoll, 2012).

RESULTS

Glycosylation is required for PD-L1 and PD-1 interaction

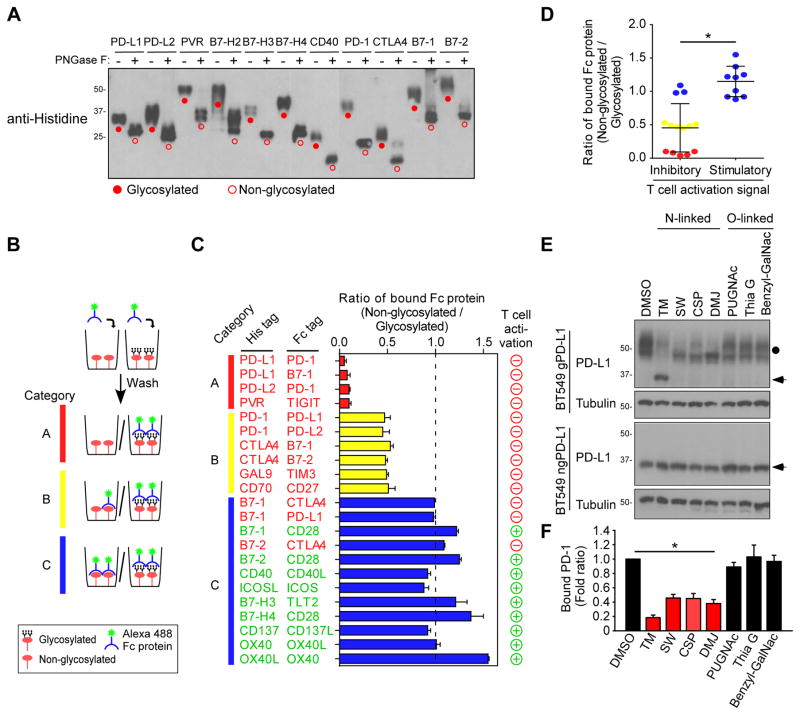

To determine whether glycosylation of immune receptor/ligands is critical for binding to their corresponding receptors, we first examined the migration pattern by Western blot analysis in the presence or absence of a recombinant glycosidase, PNGase F, which removes N-linked oligosaccharides from polypeptides. In our experience, glycosylated proteins usually display a heterogeneous pattern and appear to have higher than expected molecular weight on immunoblots (Li et al., 2016a). Bands that corresponded to higher-molecular-weight PD-L1, PD-L2, PVR, B7-H2, B7-H3, B7-H4, CD40, PD-1, cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4), B7-1, and B7-2 (Figure 1A; closed circle, glycosylated proteins) were reduced in the presence of PNGase F (Figure 1A; open circle, non-glycosylated proteins). Positive staining of the glycan structure was also observed in purified His-tagged protein but not in the presence of PNGase F (Figures S1A and S1B). Next, to determine whether glycosylation is required for ligand-receptor engagement, we employed an in vitro receptor-ligand binding assay to investigate the interaction between Fc-tagged receptors and His-tagged glycosylated or non-glycosylated ligands (Figure 1B). On the basis of the binding affinity, the ligand-receptor pairs were categorized into three groups: A, complete loss (red color), B, moderate loss (yellow color), and C, no loss (blue color) of binding (Figure 1B). A complete loss of binding was primarily found in PD-L1/PD-1, PD-L1/B7-1, PD-L2/PD-1, and poliovirus receptor (PVR)/T-cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT) immune receptor-ligand pairs but not others (Figure 1C). Of note, the co-inhibitory (induces immunosuppressive signaling, negative/red circles) but not co-stimulatory (induces immune activation signaling, positive/green circles) ligand/receptor pairs exhibited significant loss of binding upon PNGase F treatment (Figures 1C and 1D). Thus, because PD-L1 exhibited the most significant loss in receptor binding after PNGase F treatment and is a well-known immune inhibitory ligand in cancer cells, we focused on glycosylation of PD-L1 in all subsequent studies.

Figure 1. Glycosylation of inhibitory immune receptor is required for interaction with its ligand.

(A) Western blot analysis of Histidine-tagged ligand proteins. Protein samples (1 μg) were treated with or without PNGase F for 30 min before Western blot. (B) Schematic diagram of in vitro receptor and ligand binding assay. (C) In vitro association of immune ligand receptor pairs. Ratio of 1.0 indicates no change of binding upon PNGase F treatment. (D) Binding affinity of glycosylation in inhibitory and stimulatory receptors and ligands for T cell activation. The glycosylated and non-glycosylated His-tagged proteins correspond with those shown in panel (C). (E) Western blot analysis of PD-L1 expression with N-linked or O-linked glycosylation inhibitors. (F) PD-1 and PD-L1 binding assay in PD-L1 WT expressing BT549 cells treated with N-linked or O-linked inhibitors. *p < 0.05, statistically significant by Student’s t-test. Error bars, mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

See also Figure S1

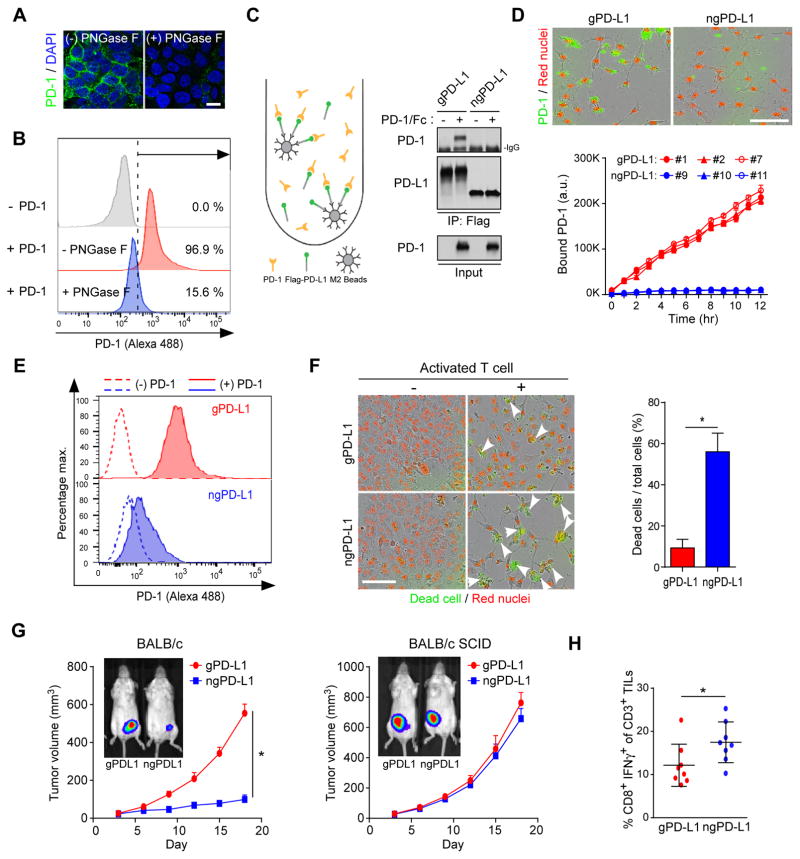

To further validate that PD-L1 glycosylation is required for PD-L1/PD-1 ligation, we first knocked down endogenous PD-L1 and then re-expressed glycosylated PD-L1 (gPD-L1, ~50 kDa) or non-glycosylated PD-L1 mutant (ngPD-L1, ~33 kDa), which lacks all four asparagine-X-threonine (NXT) motifs (Li et al., 2016a), in BT549 human breast cancer cells. The BT549-gPD-L1 and BT549-ngPD-L1 cells were then treated with glycosylation inhibitors. The results indicated that inhibitors blocking N-linked, but not O-linked, glycosylation altered the migration of PD-L1 on SDS-PAGE (top, Figures 1E and S1C). Those inhibitors, however, had no such effect on ngPD-L1 (bottom, Figure 1E), supporting that PD-L1 is primarily N-glycosylated (Li et al., 2016a). Moreover, altering PD-L1 N-linked glycosylation by tunicamycin (TM), swainsonine (SW), castanospermine (CSP), or 1-deoxymannojirimycin (DMJ) treatment substantially reduced PD-L1 and PD-1 binding (Figure 1F) in vitro. Inhibitor against mucin type O-glycosylation (benzyl-GalNAc; Figures 1F) or addition of O-glycanase which (Figure S1D) did not affect PD-L1 and PD-1 interaction, supporting the notion that the interaction is modulated specifically by N-linked glycosylation. We further examined the effects of glycosylation of cell surface PD-L1 in gPD-L1-expressing cells treated with or without glycosylation inhibitors by confocal microscopy. PNGase F (Figures 2A and 2B) and tunicamycin (Figure S2A) abrogated the binding of PD-1 to PD-L1. The results showing that Flag-ngPD-L1 failed to bind to PD-1 in a co-immunoprecipitation assay (Figure 2C) suggested that an intact glycan on PD-L1 is important for its binding to PD-1. To validate the above findings in live cells, we first selected single clones that displayed similar levels of membrane-localized gPD-L1 (clone no. 1, 2, and 7) and ngPD-L1 (clone no. 9, 10, and 11) (Figure S2B). We did not observe any significant differences in PD-L1 membrane localization in the presence of MG132 treatment (Figures S2C, confocal image, and S2D, biotinylation pull-down). Mutation of PD-L1 glycosylation sites (ngPD-L1) had no effects on the overall structure (Figure S2E) or conformational changes upon trypsin digestion (Figure S2F). The binding to PD-1 was markedly reduced in the ngPD-L1 clones but not in the gPD-L1 clones even though similar levels of PD-L1 were expressed in the cells (Figures 2D and 2E). These results suggested that glycosylation is required for the PD-L1 and PD-1 interaction.

Figure 2. Glycosylation of PD-L1 is required for interaction with PD-1.

(A) Interaction of PD-1 and PD-L1 proteins with or without PNGase F. Confocal image shows bound PD-1/Fc fusion proteins on the membrane of BT549-PD-L1 cells. (B) Flow cytometry measuring PD-1 binding on the membrane of BT549 cells expressing gPD-L1 with or without PNGase F. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis measuring the interaction of PD-1 and PD-L1 in BT549 cells expressing gPD-L1 or ngPD-L1. (D) Time-lapse microscopy quantification showing the dynamic interaction between PD-L1 and PD-1. Representative phase, red fluorescent (nuclear restricted RFP) and green fluorescent (green fluorescent labeled PD-1/Fc protein) merged images of gPD-L1- or ngPD-L1-expressing BT549 cells at 12 h (top). Scale bar, 100 μm. (E) Flow cytometry measuring the interaction of membrane bond PD-1 on gPD-L1 or ngPD-L1 expressing BT549 cells. Cells were pretreated with MG132 prior to experiment. (F) T cell-mediated tumor cell killing assay in gPD-L1- or ngPD-L1-expressing BT549 cells. Representative phase, red fluorescent (nuclear restricted RFP), and green fluorescent (NucView 488 Caspase 3/7 substrate) merged images (10× magnification) are shown. Green fluorescent cells were counted as dead cells. The quantitative ratio of dead cells showed in bar graph. (G) Tumor growth of 4T1 cells expressing gPD-L1 or ngPD-L1 in BALB/c or BALB/c SCID mice. n = 7 mice per group. (H) Quantification of intracellular cytokine stain of IFNγ in CD8+, CD3+ T cell populations in BALB/c mice. n = 8 mice per group. *p < 0.05, statistically significant by Student’s t-test. Error bars, mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

See also Figure S2

Glycosylation of PD-L1 is important for its immunosuppressive function

To determine whether glycosylation of PD-L1 governs its immunosuppressive function, we evaluated T cell response by measuring interleukin-2 (IL-2) secretion or apoptotic tumor cells in ngPD-L1 or gPD-L1 stable clones co-cultured with primary human T cells. Cells expressing ngPD-L1 were more sensitive to activated T cell (from PBMC)-mediated apoptosis (Figure 2F) and induced higher IL-2 secretion from Jurkat T cells (Figure S2G). We next examined tumorigenesis of mouse 4T1 mammary tumor cells expressing mouse gPD-L1 or ngPD-L1 in syngeneic BALB/c mice. With similar levels of mPD-L1 expression on the cell surface (Figure S2H), 4T1 cells expressing ngPD-L1 (4T1-ngPD-L1) grew significantly slower than 4T1 cells expressing gPD-L1 (4T1-gPD-L1) in BALB/c mice (Figure 2G, left); however, we did not observe any significant changes in tumor growth rates between ngPD-L1 and gPD-L1 in severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice (Figure 2G, right), suggesting the differential tumorigenicity was attributed to immune surveillance. Indeed, tumors induced by 4T1-gPD-L1 cells had less activated cytotoxic T cells (CD8+/IFNγ+) in their TILs than those in 4T1-ngPD-L1 tumors (Figure 2H). These results implied that glycosylated PD-L1 suppresses T cell activity in the tumor microenvironment, and that non-glycosylated PD-L1 causes a reduction in immunosuppressive activity likely due to its inability to bind to PD-1. Although glycosylation of PD-L1 on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) may also contribute to the overall suppressive activity, the experiment was set up for the purpose of comparing the differential response between gPD-L1 and ngPD-L1 expression in the 4T1 tumor cell system.

B3GNT3 catalyzes PD-L1 glycosylation

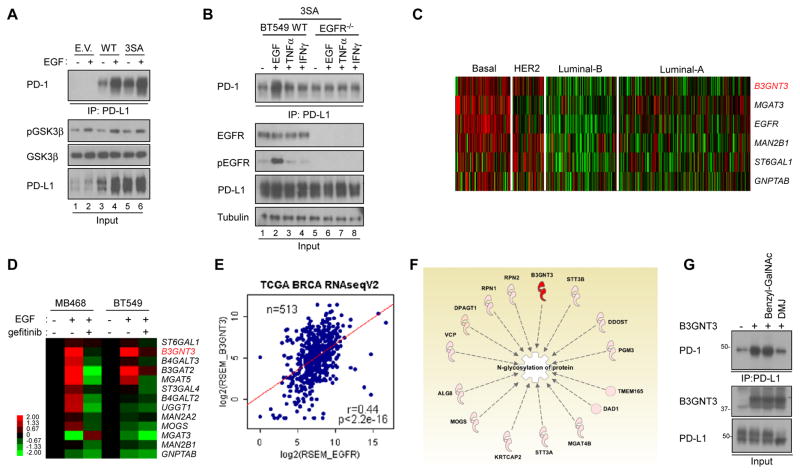

Because glycosylation of PD-L1 is critical for its immunosuppressive activity, we sought to identify the mechanisms underlying PD-L1 glycosylation. Previously, we reported that EGF signaling stabilizes PD-L1 by inhibiting GSK3β-β-TrCP-mediated degradation, and phosphorylation of ngPD-L1 by GSK3β triggers 26S proteasome-mediated degradation (Li et al., 2016a). We found the expression of PD-L1 in TNBC cells is regulated by ubiquitination (Figures S3A–S3D) and GSK3β (Figure S3E). Because glycosylation is required for ligand and receptor interaction (Figure 1), to further examine the regulatory mechanisms underlying PD-L1 glycosylation, we asked whether EGF, in addition to upregulating PD-L1 protein and/or mRNA expression (Li et al., 2016a; Lim et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2007), also enhances PD-1 binding by modulating PD-L1 glycosylation. To this end, we first examined the expression of EGFR and glycosylated PD-L1 across a panel of TNBC cell lines (Figure S3A). EGFR is known to be overexpressed in many of TNBC cells. To avoid bias by EGFR overexpression, we chose BT-549 as a suitable cell line for analysis (Figure S3A) as it exhibits moderate EGFR and PD-L1 expression and responds to EGF stimulation through EGFR as demonstrated in our earlier study (Figure 4B, Li et al. 2016). Next, we depleted endogenous PD-L1 and then re-expressed the PD-L1 3SA (S176A, T180A, and S184A) mutant to block GSK3β-mediated degradation (Li et al., 2016a). Similar to PD-L1 WT (lanes 3 vs. 4, Figure 3A), EGF also induced PD-L1 3SA and PD-1 interaction (lanes 5 vs. 6, Figure 3A), and this interaction required EGFR as EGF failed to promote PD-L1 3SA and PD-1 interaction in EGFR-knockout BT549 cells (lane 2 vs. 6, Figure 3B). Consistently, EGF induced PD-L1 WT and PD-1 interaction in the absence of GSK3β (Figure S3F). Moreover, stabilization of PD-L1 was only observed under EGF but not IFNγ treatment in another TNBC cell line (MDA-MB-468) expressing PD-L1 (Figure S3G). These results indicated that IFNγ increases PD-L1 expression primarily through transcriptional regulation as shown by the increased RNA in the parental MDA-MB-468 cells but did not stimulate PD-L1 expression under the CMV promoter in the MDA-MB-468-PD-L1 transfectants as examined by Western blotting. Together, these results indicated that, in addition to stabilizing PD-L1, EGF also triggers PD-L1 and PD-1 interaction via enhanced glycosylation.

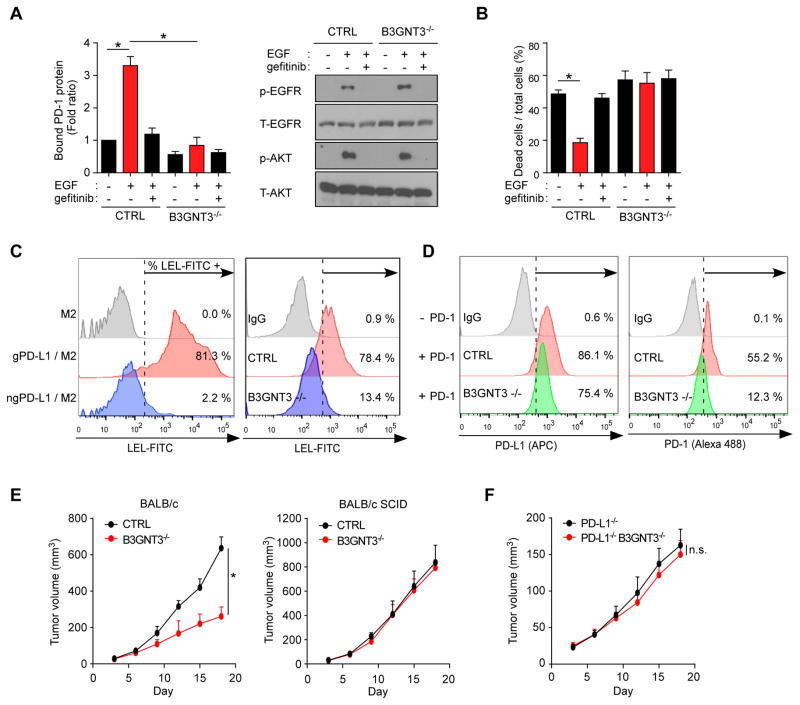

Figure 4. EGF signaling enhances PD-L1 glycosylation by B3GNT3.

(A) PD-1 and PD-L1 interaction in BT549 control (CTRL) and B3GNT3−/− cells treated with EGF or gefitinib followed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies (right). (B) T cell-mediated tumor cell killing assay in EGF- and/or gefitinib-treated BT549 CTRL or B3GNT3−/− cells. (C) The percentage represents for FITC-LEL positive PD-L1 proteins (left) or cells (right). M2 (anti-Flag) agarose sample or IgG was used as negative control. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of membrane bound PD-L1 protein (left) and membrane located PD-1 protein (right) in BT549 CTRL or B3GNT3−/− cells. (E) Tumor growth of 4T1 CTRL or B3GNT3−/− cells in BALB/c or BALB/c SCID mice. Tumor growth was measured at the indicated time points and dissected at the endpoint (n = 7 mice per group). (F) Tumor growth of 4T1 PD-L1−/− or PD-L1−/−B3GNT3−/− cells in BALB/c mice. Tumor growth was measured at the indicated time points and dissected at the endpoint (n = 7 mice per group). Data shown in (E) and (F) were collected from experiments under the same conditions to allow for comparison. *p < 0.05, statistically significant by Student’s t-test. Error bars, mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. n.s., not significant.

Figure 3. EGF signaling upregulates N-glycosyltransferase B3GNT3 in TNBC.

(A) Western blot analysis of glycosylation of PD-L1 protein in BT549 cells. Binding of PD-1 was measured by co-immunoprecipitation (IP). (B) PD-1 interaction was measured in BT549 WT and EGFR knockout (KO) cells. (C) Heatmap analysis of N-glycosyltransferase gene expression in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset. (D) Quantitative reverse transcription PCR analysis of N-glycosyltransferase mRNA expression in MDA-MB-468 (MB468) and BT549 cells treated with EGF or gefitinib. (E) Correlation between N-glycosyltransferase genes and TNBC. (F) PD-L1 bound N-linked glycosylation-associated proteins shown by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA). PD-L1 bound proteins were identified from Flag-PD-L1 co-immunoprecipitated protein complex using MS/MS analysis followed by IPA. (G) PD-1 binding assay in the presence of glycosylation inhibitors. BT549-PD-L1 cells were transient transfected with B3GNT3 with or without benzyl-GalNAc or DMJ treatment.

EGF upregulates B3GNT3 glycosyltransferase to mediate PD-L1 glycosylation

Since glycosylation of PD-L1 is required for its interaction with PD-1, we asked whether EGF signaling regulates the expression of glycosyltransferase(s) and induces PD-L1 glycosylation. To do this, we selected the enzymes according to EGFR expression in TNBC (Figure S3H) using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset because: 1) EGF/EGFR signaling is known to be an important survival signal; 2) EGFR is highly expressed in TNBC; and 3) PD-L1 protein is heavily glycosylated in TNBC cells (Li et al., 2016a). To identify the glycotransferase that catalyzes PD-L1 N-linked glycosylation in TNBC, we performed bioinformatic analysis along with the earlier identified glycan structure of PD-L1 (Li et al., 2016a). First, 50 N-linked glycotransferases was chosen based on the PCR-array panels from Qiagen (genes are listed in the Table S1). Among those 50 genes, the expression of six (MGAT3, B3GNT3, GNPTAB, ST6GAL1, MAN2B1, and MGAT5) was correlated positively with EGFR (Figure 3C) with a Pearson correlation coefficient > 0.3 (Table S1). To focus on the TNBC subtype, we sought to identify those genes upregulated in TNBC in TCGA RNAseqV2 using samples only with known subtype information. There, MGAT3, B3GNT3 (Figure S3I), ST6GAL1, B4GALT2, and MOGS expression were found to be upregulated in basal-like breast cancer (share high similarity to TNBC) patients. qPCR analysis further showed that B3GNT3 was specifically upregulated by EGF in two TNBC cell lines, MDA-MB-468 and BT549 cells (Figure 3D). We observed a strong correlation between B3GNT3 and EGFR gene expression, suggesting EGFR may be an upstream regulator of B3GNT3 (Figure 3E). Interestingly, the glycan structure on both N192 and N200 of PD-L1 contained poly-N-acetyllactosamine (poly-LacNAc) (Li et al., 2016a), which is known to be catalyzed by B3GNT3 (Ho et al., 2013). Protein identification by mass spectrometry identified B3GNT3 as a PD-L1 interacting protein (Figure 3F). The result showing B3GNT3 binding to PD-L1 further supports the involvement of B3GNT3 in PD-L1 regulation (Figure S3J). Ectopic expression of B3GNT3 or EGFR, which increases B3GNT3 expression in non-TNBC cells, induced a robust PD-L1 and PD-1 interaction, suggesting that EGFR is the major driver to induce immunosuppression in TNBC (Figure S3K). B3GNT3-mediated PD-L1 and PD-1 interaction can be blocked by DMJ but not by benzyl-GalNAc (Figure 3G). These results further suggested that B3GNT3 mediates PD-L1 and PD-1 interaction through N-linked glycosylation instead of O-linked glycosylation. Importantly, breast and lung cancer patients who had high B3GNT3 expression also had poorer overall survival outcomes than those with low or no B3GNT3 expression (Figure S3L).

Analysis of the B3GNT3 promoter region using the ENCODE transcription factor ChIP-sequencing data indicated that TCF4 downstream of the EGF-GSK3β-β-catenin pathway bound directly to the B3GNT3 core promoter region (Figures S4A and S4B), which was further validated by a reporter assay (Figures S4C and S4D). Knocking down β-catenin indeed reduced EGF-induced PD-L1 expression (Figure S4E). Knockout of B3GNT3 in BT549 cells reduced EGF/EGFR-mediated PD-1 interaction (Figure 4A) and sensitized cancer cells to T cell killing (Figure 4B). B3GNT3 catalyzes poly-LacNAc (Ho et al., 2013), which is present on PD-L1 N192 and N200 (Li et al., 2016a). Consistently, the results from lectin binding assay (Table S2) indicated that lycopersicon esculentum (Tomato) lectin (LEL), which is known to specifically recognize poly-LacNAc moiety (Sugahara et al., 2012), bound to gPD-L1 but not ngPD-L1 (81.3% vs. 2.2%; Figure 4C). Moreover, knocking out B3GNT3 in BT549 cells only slightly reduced the levels of cell surface PD-L1 (Figure 4D, left). However, the binding between PD-L1 and PD-1 was substantially reduced (Figure 4D, right, 55.2% vs. 12.3%). Consistent with the analysis of PD-L1 glycosylation (Figure 2G), the tumors induced by 4T1 B3GNT3 knockout cells grew slower than those induced by 4T1 knockout control cells in BALB/c mice but not in BALB/c SCID mice (Figure 4E). Of note, PD-L1 knockout also reduced tumor growth (Figure 4E vs. Figure 4F). In fact, knocking out B3GNT3 impaired 4T1 tumor growth similar to knocking out PD-L1. In addition, PD-L1 or B3GNT3 knockout cells showed reduced tumor growth similar to that of the PD-L1/B3GNT3 double knockout. Together, these results supported the notion that reduced tumor growth by B3GNT3 is mediated through PD-L1 in BALB/c mice.

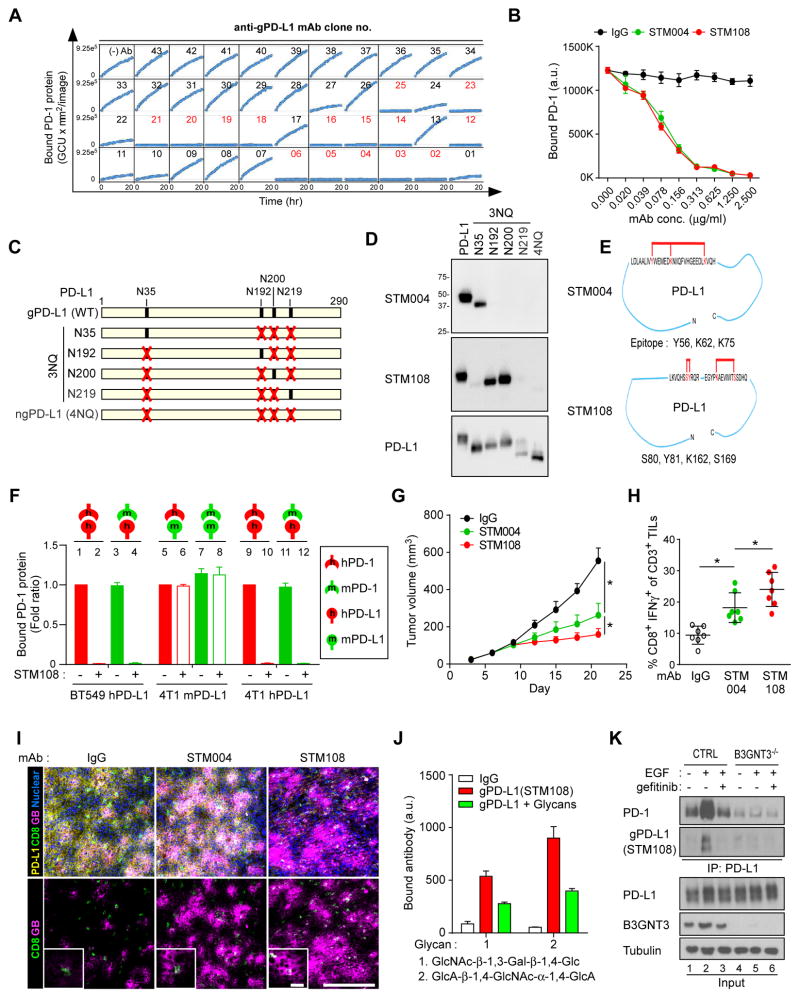

Generation of glycosylation-specific PD-L1 antibodies

Glycosylated antigen-specific antibodies are valuable in cancer therapy (Xiao et al., 2016). The above results prompted us to generate monoclonal antibodies that specifically recognize gPD-L1. To this end, we purified gPD-L1 protein from BT549 cells expressing heavily glycosylated PD-L1. Among 3,000 hybridomas that were screened against purified gPD-L1 by flow cytometry (Figure S5A), 165 glycosylation-specific monoclonal antibodies were isolated based on the specificity to gPD-L1 as well as the ability to block PD-1 interaction (representative positive clones labeled in red, Figure 5A). We also examined the selectivity by immunoblotting (Figure S5B), the specificity for gPD-L1 in human tumor tissues by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining (Figure S5C), and the ability to detect membrane bound PD-L1 by flow cytometry (Figure S5D). Based on the specificity, binding affinity (decreased equilibrium dissociation constant [KD] values), and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade efficacy (decreased half-maximal effective concentrations [EC50]) (Figure S5E and Table S3), we selected STM004 and STM108 for further analysis. STM004 and STM108 effectively blocked PD-L1/PD-1 interaction (Figure 5B) and recognized N35, and N192 and N200 glycosylation sites, respectively, on PD-L1 (Figures 5C and 5D). Consistent with the site specificity, epitope mapping indicated that STM108 cross-linked with amino acids more toward the C-terminus (Y81, K162, and S169) whereas STM004 detected amino acids relatively closer to the N-terminus (Y56, K62 and K75) of PD-L1 (Figure 5E and Table S3).

Figure 5. Production and validation of glycosylated PD-L1 antibodies.

(A) PD-1/PD-L1 blockade by glycosylated PD-L1 antibodies. Kinetic graph showing quantitative binding of PD-1/Fc protein on BT549 cells expressing PD-L1 at hourly time points after treatment with glycosylated PD-L1 antibodies. (B) Blockade of PD-L1 and PD-1 interaction by the glycosylated PD-L1 antibodies STM004 and STM108. (C) Schematic diagram of various PD-L1 NQ mutants used in this study. The numbers indicate amino acid positions of the PD-L1 protein. (D) Western blot analysis of wild-type and mutant PD-L1 using STM004 or STM108 antibody. (E) Epitope mapping of glycosylated PD-L1–binding antibodies by High-Mass MALDI mass spectrometry (CovalX service). (F) Interaction of human PD-1 (hPD-1) or mouse PD-1 (mPD-1) protein with human PD-L1 (hPD-L1) on BT549 cells or mouse PD-L1 (mPD-L1) or hPD-L1 on 4T1 cells, with or without STM108 antibody. (G) Tumor growth of 4T1 cells expressing human PD-L1 (4T1-hPD-L1) in BALB/c mice treated with STM004 or STM108 antibody. Tumors were measured at the indicated time points and dissected at the endpoint. n = 7 mice per group. (H) Intracellular cytokine stain of IFNγ in CD8+ CD3+ T cell populations. n = 7 mice per group. (I) Immunofluorescence staining of the protein expression pattern of PD-L1, CD8, and granzyme B (GB) in a 4T1-hPD-L1 tumor mass. Scale bar, 100 μm (20 μm in magnified sections). (J) Quantitative binding affinity of gPD-L1 antibody (STM108) to glycan 1 and 2. Glycan array 100 was probed with biotin-labeled gPD-L1 antibody. gPD-L1 antibody bound to two glycans (1 and 2), and the bindings were compromised by a mixture of B3GNT3 substrate or product, mixture of DiLacNAc and GlcNAcβ1,3-Gal. (K) Western blot analysis of glycosylation of PD-L1 protein in BT549 cells by STM108 (gPD-L1). BT549 control (CTRL) or B3GNT3−/− cells were treated with 25 ng/ml EGF or gefitinib overnight. *p < 0.05, statistically significant by Student’s t-test. Error bars, mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

STM108 is a mouse antibody that recognizes human PD-L1. In order to evaluate its therapeutic efficacy in a syngeneic animal model, we first generated mouse (m) 4T1 cells expressing human (h) PD-L1 (4T1-hPD-L1) by knocking out or down mPD-L1 and re-expressing hPD-L1 (see details in Methods). We compared the effects of STM108 on PD-L1 and PD-l binding in 4T1-hPD-L1 cells to those in BT549 expressing hPD-L1 (BT549-hPD-L1) and 4T1 cells expressing mPD-L1 (4T1-mPD-L1) by in vitro binding assays (Figure 5F). hPD-L1 and mPD-1 binding was similar to the cognate hPD-L1 and hPD-1 pair (lanes 3 and 11 vs. 1 and 9, Figure 5F). Consistently, STM108 efficiently blocked hPD-L1-mPD-1 interaction (lanes 4 and 12, Figure 5F) as well as hPD-L1-hPD-1 (lanes 2 and 10, Figure 5F) but not mPD-L1-mPD-1 or mPD-L1-hPD-1 (lanes 6 and 8, Figure 5F) as STM108 does not recognize mPD-L1. In 4T1-hPD-L1-inoculated BALB/c mice, treatment with either STM004 or STM108 also significantly reduced their tumor size (Figure 5G) and higher cytotoxic T cell activity as measured by CD8+/IFNγ+ and granzyme B expression, respectively (Figures 5H and 5I), compared with the control, with more potent effects from STM108 than those from STM004. Additionally, both STM004 and STM108 demonstrated good safety profiles as the levels of enzymes indicative of liver and kidney functions (Figure S5F) did not change significantly. We also observed a positive correlation between gPD-L1 (targeted by STM108), p-EGFR, and B3GNT3 in 112 breast carcinoma tissue samples by IHC staining (Figure S5G and Table S4). The results from in vitro and in vivo validation indicated that the antibodies that recognize glycosylated PD-L1 effectively inhibits the PD pathway and enhances mouse anti-tumor immunity.

Furthermore, to determine whether STM004 and STM108 recognize the glycan moiety catalyzed by B3GNT3, we performed a glycan array screening using biotin-labeled STM108 or STM004. STM108 specifically bound to GlcNAc-β-1,3-Gal-β-1,4-Glc and GlcA-β-1,4-GlcNAc-α-1,4-GlcA polysaccharides, which was competed by the addition of a mixture of glycans containing these two polysaccharides (Figures 5J and S5H). In contrast, STM004 did not bind to GlcNAc-β-1,3-Gal-β-1,4-Glc (data not shown). Interestingly, poly-LacNAc, which contains GlcNAc-β-1,3-Gal-β-1,4-Glc and is synthesized by B3GNT3 (Ho et al., 2013), was detected on PD-L1 N192 and N200 (Li et al., 2016a). Depletion of B3GNT3 by CRISPR/Cas9 in BT549 cells impaired EGF-induced PD-L1 glycosylation, and thus was not recognized by STM108 in Western blotting (lanes 2 vs. 5, Figure 5K), further supporting the presence of poly-LacNAc moiety on PD-L1 and its recognition by STM108. Taken together, we successfully isolated a PD-L1 antibody (STM108) that can specifically recognize B3GNT3-mediated the poly-LacNAc moiety on N192 and N200 glycosylation sites of PD-L1.

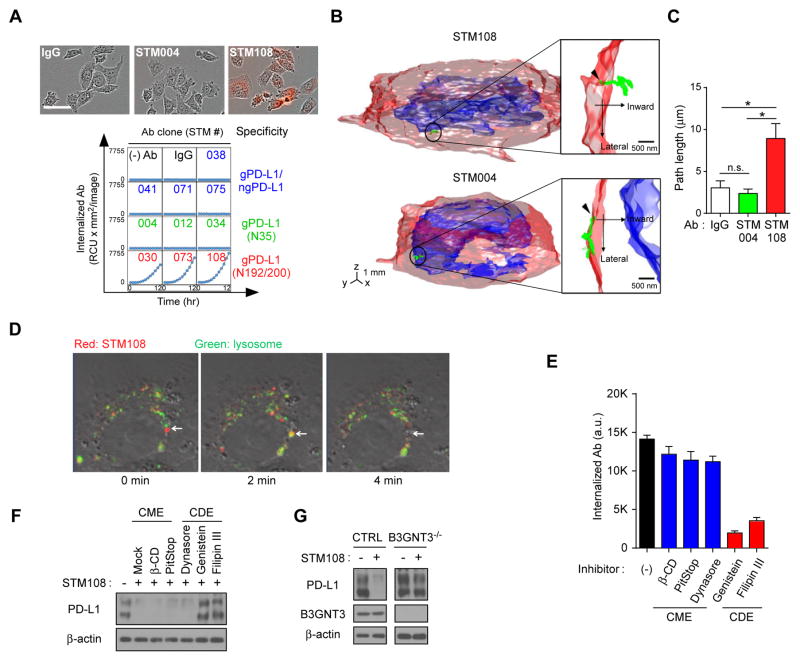

STM108 antibody induces PD-L1 internalization and degradation

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) have been shown to possess pronounced activity in clinical trials with the advantage to deliver drugs with bystander activity (Li et al., 2016b). Unlike PD-1 or CTLA4, PD-L1 is mainly expressed on tumor cells but not normal cells (Dong et al., 2002). Cytokines, such as IFNγ and TNFα, which are present in the tumor microenvironment, have been shown to elevate the levels of PD-L1 on cancer cells to switch off T cell activity (Chen and Han, 2015). In this regard, in addition to blocking immune checkpoint, PD-L1 is an ideal candidate for drug conjugation due to its cancer specificity. Moreover, the lack of response of tumors to immunotherapy is partly attributed to the heterogeneous expression of PD-L1 (McLaughlin et al., 2016). Therefore, the bystander effect of PD-L1-ADC can further increase efficacy by inhibiting adjacent cancer cells that have low or no PD-L1 expression.

To further explore this possibility, we first examined the ability of gPD-L1-specific antibodies to induce PD-L1 internalization using pHrodo Red-labeled antibodies in PD-L1- expressing BT549 cells. The results showed that STM108 but not STM004 mediated PD-L1 internalization to the lysosomes as indicated by the detection of red fluorescence when the pH was decreased from 7.0 to 4.5 (Figure 6A). Interestingly, among 10 antibodies tested, only three (STM030, STM073, and STM108) that recognized the N192 and N200 glycosylation sites of PD-L1 were internalized (Figure 6A) whereas antibodies that recognized N35 (STM004, STM012, and STM034) or both gPD-L1 and ngPD-L1 (STM038, STM041, STM071 and STM075) did not. To further validate the endocytosis of the STM108-PD-L1 protein complex, we utilized a recently developed three-dimensional single-molecule tracking platform TSUNAMI technology (Perillo et al., 2015) to record the trajectory of single protein complex in a live BT549 cell. A representative trajectory of a single STM108-PD-L1 moving 10 μm inward into the cytoplasm within 400 sec is shown in Figures 6B, 6C and Movie S1. In contrast, the STM004-PD-L1 complex remained on the cell surface (Figures 6B, 6C, and Movie S2). Western blot analysis indicated a robust degradation of PD-L1 after STM108 treatment (Figure S6A). Time-lapse immunofluorescence analysis further demonstrated co-localization of STM108 and lysosome followed by rapid PD-L1 degradation at the 2-min and 4-min time point (arrows) after STM108 treatment (Figure 6D). These results indicated that STM108 binding to PD-L1 occurred before degradation and suggested that STM108 is an ideal candidate for ADC.

Figure 6. gPD-L1 antibody STM108 induces internalization and degradation of PD-L1.

(A) Internalization of glycosylated PD-L1 antibodies. Internalized antibodies (Ab) in BT549 cells expressing PD-L1 are shown at each time point. Representative phase and red fluorescent merged images at 12 hours are shown. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Trafficking of an individual STM108 (top) or STM004 (bottom) antibody in BT549 cells was visualized by the live cell three-dimensional single-molecule tracking system (TSUNAMI). A representative trajectory of antibody moving into the cytoplasm from the cell membrane. (C) The path length of trajectories acquired from IgG, STM004, and STM108 from (B). n.s., not significant. (D) Internalization of STM108 and its co-localization in lysosome. The antibodies were labeled with pHrodoTM Red and then add to PD-L1 WT expressing BT549 cells with LysoTracker® Green. Arrow indicates localization of STM108 at lysosome after internalization. (E) Internalization of STM108 in BT549-PD-L1 cells treated with clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) or caveolae-dependent endocytosis (CDE) inhibitors. (F) Western blot analysis of wild-type (WT) PD-L1 in STM108 and/or CME or CDE inhibitor-treated BT549-PD-L1 cells. (G) Western blot analysis of PD-L1 expression. BT549 cells control (CTRL) or B3GNT3−/− were treated with STM108 for 2 days. *p < 0.05, statistically significant by Student’s t-test. Error bars, mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

Modulation of the glycosylation state has been shown to facilitate clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) (Garner and Baum, 2008). To determine whether the CME or caveolae-dependent endocytosis (CDE) pathway is associated with PD-L1 internalization, we treated cells with several inhibitors of CME or CDE. The results showed that inhibitors of CDE, but not CME, effectively inhibited STM108-induced PD-L1 internalization (Figures 6E, 6F, S6B, and S6C). Because STM108 recognizes the poly-LacNAc moiety, we also examined the effects of B3GNT3 depletion on STM108-induced PD-L1 internalization and degradation. As expected, STM108 did not induce PD-L1 internalization or degradation in B3GNT3 knockout cells (Figures 6G and S6D), further suggesting that recognition of the poly-LacNAc moiety on N192 and N200 by PD-L1 requires B3GNT3. Together, these data indicated that STM108-induced PD-L1 internalization occurs via CDE and is N192- and N200-glycosylation dependent.

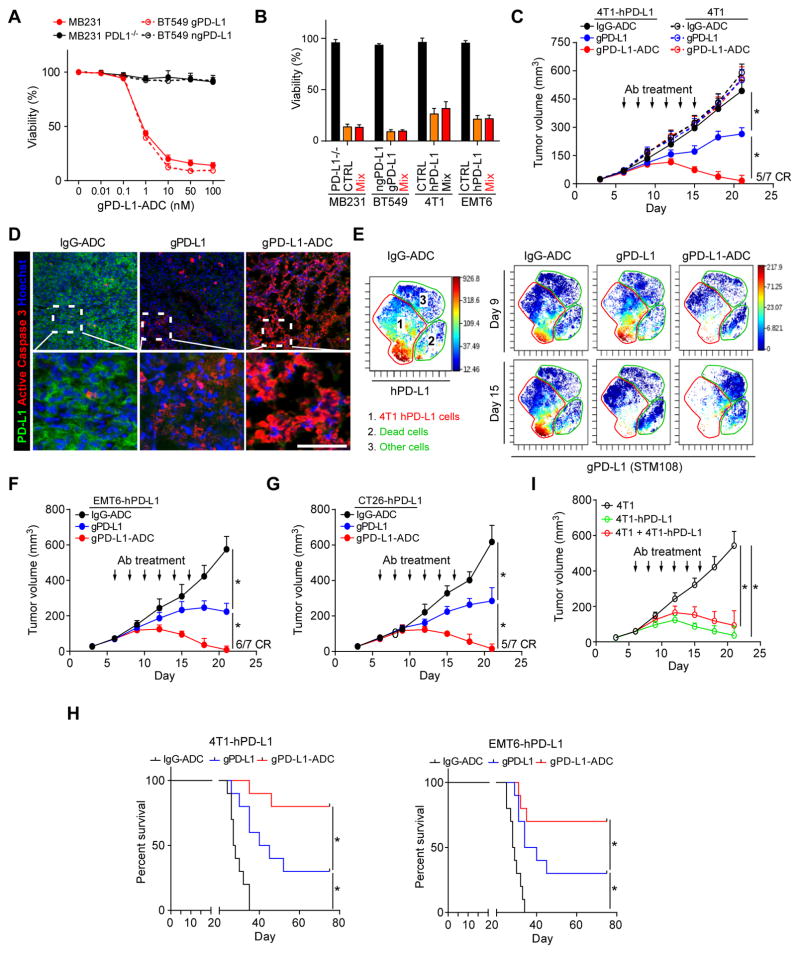

Glycosylated PD-L1 ADC is highly potent and relatively safe

It has been proposed that human PD-L1+ APCs play a role in PD-L1/PD-1-mediated immunosuppression (Zou and Chen, 2008). Indeed, glycosylated PD-L1 expression was observed in APCs (dendritic cells and macrophages) (Fig. S6E). In addition, as shown in the Figure S6E, normal tissues and naive immune cells expressed very low levels of PD-L1 and gPD-L1, which increases the feasibility of cell-specific killing by drug conjugation to STM108. To this end, we generated an STM108 antibody conjugated with a potent antimitotic drug monomethylauristatin E (MMAE) (Junutula et al., 2008) called STM108-ADC (hereinafter referred to as gPD-L1-ADC; Figure S7A). The viability of BT549 and MDA-MB-231 (MB231) cells expressing gPD-L1, but not those expressing ngPD-L1 or PD-L1 knockout cells, was attenuated upon gPD-L1-ADC treatment (Figures 7A, 7B, and S7B). Loss of B3GNT3 also impaired gPD-L1-ADC-mediated anti-cancer effect (Figure S7C). In addition, gPD-L1-ADC selectively suppressed tumors with hPD-L1 antigen (4T1-hPD-L1 or EMT6-hPD-L1) but not parental tumors that express mouse PD-L1 (4T1 or EMT6) (Figure S7D). Similar to results from in vitro assays, gPD-L1-ADC markedly reduced tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner in a 4T1-hPD-L1 syngeneic mouse model (Figure S7E). Treatment with gPD-L1-ADC led to complete regression of 4T1-hPD-L1 tumors in ~70% mice but not those with 4T1 tumors, which continued to grow (Figure 7C). In addition, gPD-L1-ADC induced massive cell death of 4T1-hPD-L1 tumor cells compared with gPD-L1 alone as indicated by active caspase 3 staining (Figure 7D) and dead cell population (Figures 7E, and S7F, CyTOF analysis). A similar complete regression rate was recapitulated in EMT6-hPD-L1 or CT26-hPD-L1 syngeneic BALB/c mouse model (Figures 7F and 7G). Furthermore, gPD-L1-ADC-treated mice exhibited significantly better survival than those treated with gPD-L1 (STM108) or IgG control (Figure 7H). No significant body weight changes (data not shown) or liver and kidney toxicities were observed during the course of therapy (Figure S7G).

Figure 7. gPD-L1 antibody-drug conjugate (gPD-L1-ADC) exhibits PD-L1/PD-1 blockade and cytotoxicity in 4T1-hPD-L1 syngeneic mouse model.

(A) Cytotoxic profile of anti-gPD-L1-ADC in MDA-MB-231 (MB231) or BT549 cells with or without antigen. Cell viability was measured by CellTiter-Glo at 72 h. (B) Bystander effect of gPD-L1-ADC on human breast cancer (MB231 and BT549) or mouse mammary tumor (4T1 and EMT6) cell lines. Cell viability were measured after 50 nM gPD-L1-ADC treatment at 72 h. (C) Tumor growth of 4T1 cells expressing human PD-L1 (4Tl-hPD-L1) or parental 4T1 cells in BALB/c mice treated with IgG-ADC, gPD-L1 (STM108), or gPD-L1-ADC. Tumors were measured at the indicated time points and dissected at the endpoint. n = 7 mice per group. Arrow, antibody (Ab) treatment; CR, complete regression. (D) Immunofluorescence staining of the protein expression pattern of PD-L1 and active caspase 3 (apoptotic cell marker) in a 4T1-hPD-L1 tumor mass. Scale bar, 50 μm. (E) viSNE map derived from CyTOF (7-marker) analysis of 4T1-hPD-L1 tumors at day 9 and 15. Tumor cell populations were identified as hPD-L1 markers. Cells in the map are color-coded by the intensity of expression of the indicated markers. (F and G) Tumor growth of EMT6 cells expressing human PD-L1 (EMT6-hPD-L1, F) or CT26 cells expressing human PD-L1 (CT26-hPD-L1, G) cells in BALB/c mice treated with IgG-ADC, gPD-L1, or gPD-L1-ADC. Tumors were measured at the indicated time points and dissected at the endpoint. n = 7 mice per group. Arrow, antibody (Ab) treatment; CR, complete regression. (H) Survival of mice bearing syngeneic 4T1-hPD-L1 or EMT6-hPD-L1 tumors following treatment with IgG-ADC, gPD-L1, or gPD-L1-ADC. Significance (*) was determined by the log-rank test (n = 10 mice per group). (I) Bystander effect of gPD-L1-ADC in BALB/c mice. 4T1 and 4T1-PD-L1 cells were mixed at 1 to 1 ratio. Tumors were measured at the indicated time points and dissected at the endpoint. n = 7 mice per group. *p < 0.05, statistically significant by Student’s t-test. Error bars, mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

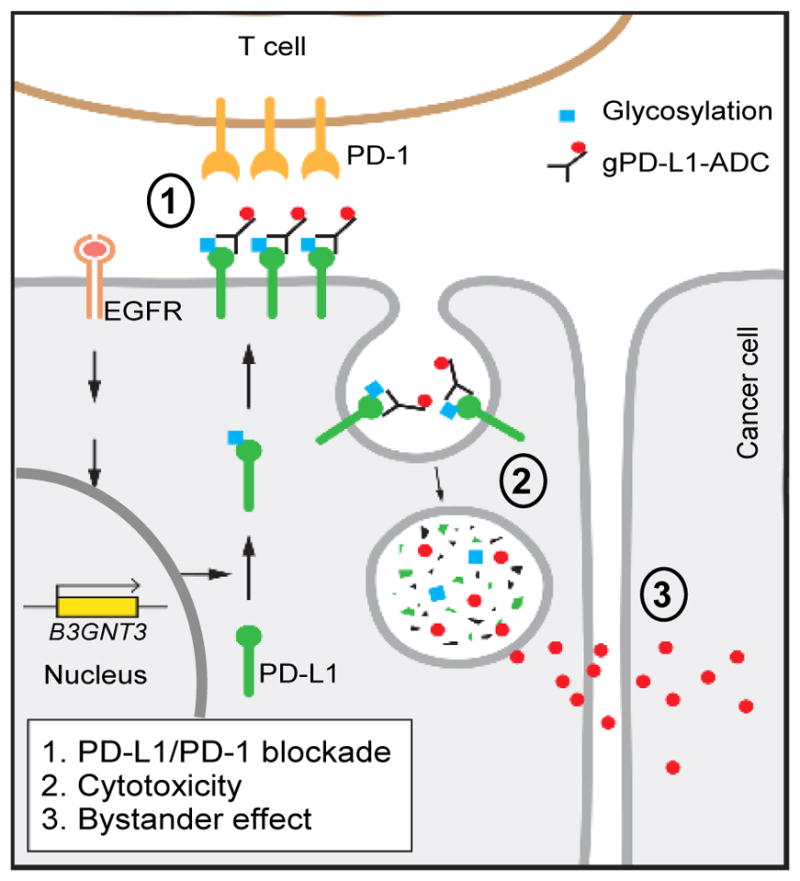

Interestingly, when both WT and PD-L1 knockout MB231 cells were mixed together, cell viability remained suppressed (red, Figure 7B), suggesting the presence of bystander activity of MMAE (Okeley et al., 2010). This bystander effect was also observed in three other cell systems (red, Figure 7B) and in 4T1 mouse model (red, Figure 7I) in which gPD-L1-ADC elicited potent anti-tumor activity when 4T1 cells were mixed with 4T1-hPD-L1 expressing the hPD-L1 antigen but not 4T1 cells alone without hPD-L1 expression. These results suggested that the residual toxin released from gPD-L1-ADC was sufficient to inhibit growth of the surrounding tumor cells even without hPD-L1 expression at primary tumor sites to produce a bystander effect. As expected, because STM004 did not induce PD-L1 internalization (Figure 6A), both STM004 and STM004-ADC only slightly reduced tumor growth but not tumor regression (Figure S7H). Although the therapeutic action of gPD-L1 antibody relied on acquired immunity (Figure S7I, black vs. blue), gPD-L1 ADC eliminated 4T1-hPD-L1 tumors even in SCID mice (Figure S7I, blue vs. red). Taken together, these results suggested that gPD-L1-ADC possesses potent antitumor activity by 1) inducing T cell reactivation; 2) eliciting drug-induced cytotoxic activities; and 3) exerting a strong bystander effect against breast cancer cells (Figure 8, proposed model).

Figure 8.

Proposed mechanism of action of gPD-L1-ADC.

DISCUSSION

A series of studies have dissected the stepwise glycan synthesis of inducible T cell costimulator (ICOS) that glycosylation of ICOS is not required for its interaction with ICOS ligand (Kamei et al., 2010). Consistently, we showed that co-stimulatory signaling does not require glycosylation (Figures 1B and 1C). However, it has become evident that glycosylation indeed is involved in many co-inhibitory signaling interactions, suggesting that the status of membrane receptor glycosylation should be considered to improve the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. The N-glycan of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) (Croci et al., 2014), neurokinin 1 receptor (Tansky et al., 2007), dendritic cell- specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3 grabbing non- integrin (DC-SIGN) (Torreno-Pina et al., 2014), and mucin 1 (MUC1) (Altschuler et al., 2000) have been reported to enhance endocytosis through the interaction with clathrin. Moreover, modulation of the glycosylation state has been shown to facilitate CME (Garner and Baum, 2008). Although the exact mechanism of PD-L1 internalization is still unknown, we demonstrated that only antibodies that recognized the N192/N200 sites of gPD-L1 (STM108), but not those that were non-specific (IgG) or specific against N35 (STM004), induced PD-L1 internalization. Currently, we do not know why functional glycosylation is found only on inhibitory but not stimulatory B7 family members (Kamei et al., 2010). However, we speculated that 1) a common binding module via glycosylation may exist in the co-inhibitory receptors, 2) certain conformational changes between gPD-L1 and gPD-1 may trigger T cell exhaustion, and 3) aberrant glycan changes may contribute to cancer malignancy. It is thus of interest to compare the glycan structure between inhibitory and stimulatory family members systematically in the future. If a specific glycosylation motif exists to distinguish these two classes of molecules, it may have important clinical implications. The current report provides the scientific basis to study glycosylation in co-inhibitory signaling. One of the major concerns regarding ADC treatment is its clinical toxicity. gPD-L1-ADC demonstrated substantial therapeutic efficacy in 4T1-hPD-L1, EMT6-hPD-L1, and CT26-hPD-L1 syngeneic mouse models without inducing significant acute liver or kidney toxicity. Although PD-L1 protein is highly expressed in cancer cells and in some immune cells, such as tumor-associated macrophages and myeloid dendritic cells, most of these targeted by gPD-L1 are localized in the tumor area, which limits its toxicity. Moreover, because gPD-L1-ADC specifically recognizes the poly-LacNAc moiety on N192 and N200 of PD-L1, it exerts specificity and affinity without significant cytotoxicity in normal cells and primary human pan-T cells, suggesting a relatively safe clinical application.

In contrast to chemotherapy, ADC allows discrimination between normal and cancer cells. Although both ado-trastuzumab emtansine and brentuximab have yielded successful outcome, optimizing the therapeutic window remains a challenge for the safety of ADC (Tolcher, 2016). In this study, we demonstrated that gPD-L1 is an excellent candidate for ADC as the glycan moiety is critical for PD-L1 endocytosis and degradation. Moreover, the expression of glycosyltransferase B3GNT3 is relatively lower in normal breast tissues than in breast cancer tissues (The Human Protein Atlas, 2017), suggesting that B3GNT3-mediated glycosylation PD-L1 is a cancerous event. Therefore, gPD-L1 antibody represents a next generation of immunotherapy that can increase target specificity and reduce the off-target effects of ADC as EGFR/B3GNT3/gPD-L1 axis is upregulated in TNBC cells.

STAR Methods

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Mien-Chie Hung (mhung@mdanderson.org).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell culture and transfection

All cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA), independently validated by STR DNA fingerprinting at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX, USA), and negative for mycoplasma contamination. These cells were grown in in DMEM/F12 or RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. PD-L1 stable transfectants in MDA-MB231, MDA-MB468, BT549, and HEK 293T cells were selected using puromycin (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA). Cells were transiently transfected with DNA using X-tremeGENE (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) or lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). For treatment with EGF, TNFα, or IFNγ, cells were serum-starved overnight prior to cytokine stimulation at the indicated time points.

Animal treatment protocol

All BALB/c or BALB/c SCID (CBySmn.CB17-Prkdcscid/J) mice (6–8-week-old females; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) procedures were conducted under the guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at MD Anderson. Mice were divided according to the mean value of tumor volume in each group. 4T1 or 4T1 hPD-L1 cells (5 × 104 cells in 25 μl of medium mixed with 25 μl of Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix [BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA]) were injected into the mammary fat fad. For treatment with antibody, 100 μg of STM004, STM108, PD-L1 antibody-drug conjugate (gPD-L1-MMAE; RMP1-14), mouse IgG1 (Bio X Cell, West Lebanon, NH, USA), or mouse IgG2b (Bio X Cell) as a control was injected intraperitoneally on days 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 after 4T1 cell inoculation. For the antibody-drug conjugate (gPD-L1-ADC antibody), gPD-L1 (STM108), STM004, and mouse IgG antibodies were conjugated with Val-Cit-MMAE (Moradec LLC, San Diego, CA, USA). The drug-antibody ratio (DAR) was calculated by the following formula: ratio of A248nm/A280nm = (n*ExPAB 248nm + ExmAb248nm)/(n*ExPAB 280nm + ExmAb 280nm), (n: DAR). The DAR of gPD-L1-ADC (STM108-MMAE) was 4.13 and the DAR of STM004-MMAE was 3.34. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. Tumors were measured with a caliper, and tumor volume was calculated by the following formula: π/6 × length × width2.

Animal procedure

To study the therapeutic effects of gPD-L1 antibody in preclinical tumor models, 4T1-hPD-L1 (5 × 104) or CT26-hPD-L1 (5 × 104) cells were suspended in 25 μL of medium mixed with 25 μl of matrigel basement membrane matrix (BD Biosciences) and injected subcutaneously into 6-week-old female BALB/c mice (Jackson Laboratories). Tumor volume was measured with a caliper and determined using the formula π/6 × length × width2, where length is the longest diameter and width is the shortest diameter. For gPD-L1 antibody treatment, 5 mg/kg of gPD-L1 antibody or control mouse IgG was injected intraperitoneally on days 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 after tumor cell inoculation (n = 7 mice per group). Data from at least three biological replicates are presented and reported as mean ± S.D. Statistical analysis was carried out using paired Student’s t-test and assumed to be significant at p < 0.05.

Human tissues

Human breast tumor tissue specimens were obtained following the guidelines approved by the Institutional Review Board at MD Anderson, and written informed consent was obtained from patients in all cases at the time of enrollment. One hundred and twelve archived, paraffin-embedded breast carcinoma slides were obtained from the Department of Pathology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

METHOD DETAILS

Immune receptor and ligand interaction assay

To measure immune receptor and ligand interaction, His-tagged proteins were incubated with or without Rapid PNGase F (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) in non-reducing buffer for 30 minutes at 50 °C and then placed on a nickel-coated 96-well plate. The plate was then incubated with recombinant Fc-tagged protein for 1 hour. The secondary antibodies used were anti-human Alexa Fluor 488 dye conjugate (Life Technologies). Fluorescence intensity of Alexa Fluor 488 dye was measured using a microplate reader (Synergy Neo; BioTeK, Winooski, VT, USA) and normalized to the intensity by total protein quantity.

To measure PD-1 and PD-L1 proteins interaction, we fixed cells in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 minutes and then incubated them with recombinant human PD-1 Fc protein (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 1 hr. The secondary antibodies used were anti-human Alexa Fluor 488 dye conjugate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI blue; Thermo Fisher Scientific). For imaging, after cell mounting, we visualized them using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA). To monitor dynamic PD-1 protein binding on live cell surfaces, we incubated cells expressing gPD-L1 or ngPD-L1 with Alexa Fluor 488 dye conjugate PD-1 Fc protein and obtained a time-lapse image every hour for 24 hours using an IncuCyte Zoom microscope (Essen Bioscience, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) (Li et al., 2016).

Immunofluorescence for mouse tumor tissue

Tumor masses were frozen in an OCT block immediately after extraction. Cryostat sections of 5-μm thickness were attached to saline-coated slides. Cryostat sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature and blocked with blocking solution (5% bovine serum albumin, 2% donkey serum, and 0.1M PBS) at room temperature for 30 minutes. Samples were stained with primary antibodies against PD-L1, CD8, granzyme B, or active Caspase 3 overnight at 4°C, followed by secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 hour. Nuclear staining was performed with Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A confocal microscope (LSM700; Carl Zeiss) was used for image analysis.

T cell-mediated tumor cell killing assay

The T cell-mediated tumor cell killing assay was performed according to the modified manufacturer’s protocol (Essen Bioscience) and has been described previously (Li et al., 2016). Briefly, to prime tumor cell-specific T cells, we co-cultured tumor cells with anti-CD3 antibody and IL-2–stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) for 5 to 7 days and then isolated and expanded the T cell population using ImmunoCult Human CD3/CD28 T Cell Activator (Stemcell Technologies). To analyze the killing of tumor cells by T cell, we co-cultured nuclear-restricted, RFP-expressing tumor cells with activated primary human T cells (Stemcell Technologies) in the presence of caspase 3/7 substrate (Essen Bioscience). T cells were activated by incubation with anti-CD3 antibody (100 ng/ml) and IL-2 (10 ng/ml). After 96 hours, RFP and green fluorescent (NucView 488 Caspase 3/7 substrate) signals were measured. Green fluorescent cells were counted as dead cells.

Antibodies and chemicals

The antibodies used in the current study are listed in Table S5. TNFα and IFNγ were purchased from R&D Systems. EGF, cycloheximide, MG132, LiCl, tunicamycin, swainsonine, castanospermine, deoxymannojirimycin, PUGNAc, and Thiamet G were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). SB2035580, PD89059, LY294002, U0126, and Bay 11-7082 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Denvers, MA, USA).

Tumor infiltration lymphocyte profile analysis

Mice receiving 5 × 104 4T1 or EMT6 cells were treated with antibodies as descried in the figures. Excised tumors were dissociated as a single cell using the gentleMACS Dissociator (Miltenui Biotec Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) with the mouse Tumor Dissociation kit (Miltenui Biotec) and lymphocytes were enriched on a Ficoll gradient (Sigma-Aldrich). T cells were isolated using Dynabeads untouched mouse T cell kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). T cells were stained using anti-CD3-PerCP (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), CD4-FITC (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), CD8-APC/Cy7 (BioLegend), CD45.1-PE (BioLegend), and IFNγ-Pacific Blue antibodies. Stained samples were analyzed using a BD FACSCanto II (BD Bioscience) cytometer.

Tumor cell profile analysis by CyTOF

Excised tumors were dissociated as a single cell using the gentleMACS™ Dissociator (Miltenui Biotec Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) with the mouse Tumor Dissociation kit (Miltenui Biotec) and tumor cells were enriched on a Ficoll gradient (Sigma-Aldrich). For CyTOF analysis, tumor cells were incubated with a mixture of metal-labeled antibodies (Table S5) for 30 minutes at room temperature, washed twice, and incubated with Cell-ID Intercalator-103Rh (Fluidigm, San Francisco, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C. We also used Cell-ID Cisplatin 195Pt (Fluidigm) for dead cell marker. The samples were analyzed using the CyTOF2 instrument (Fluidigm) in the Flow Cytometry and Cellular Imaging Core Facility at MD Anderson. CyTOF data were analyzed by viSNE in Cytobank (Cytobank, Inc. Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Generation of stable cells using lentivirus

The lentiviral-based shRNA (pGIPZ plasmids) used to knock down expression of human or mouse PD-L1 was purchased from the shRNA/ORF Core Facility at MD Anderson. Using a pGIPZ-shPD-L1/Flag-PD-L1 dual-expression construct to knock down endogenous PD-L1 and reconstitute Flag-PD-L1 simultaneously (Lim et al., 2016), we established endogenous PD-L1 knockdown and Flag-PD-L1 wild-type (WT)-expressing cell lines. To generate lentivirus-expressing shRNA for PD-L1 and Flag-PD-L1, we transfected HEK293T cells with pGIPZ-non-silence (for vector control virus), pGIPZ-shPD-L1, or pGIPZ-shPD-L1/PD-L1 WT with X-tremeGENE transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics). Twenty-four hours after transfection, the medium was changed and then collected at 24-hour intervals. The collected medium containing lentivirus was centrifuged to eliminate cell debris and filtered through 0.45-μm filters. Cells were seeded at 50% confluence 12 hours before infection, and the medium was replaced with medium containing lentivirus. After infection for 24 hours, the medium was replaced with fresh medium and the infected cells were selected with 1 μg/ml puromycin (InvivoGen). To overexpress PD-L1 WT or mutants, we used PD-L1 WT or mutant constructs as described previously (Li et al., 2016; Lim et al., 2016). For PD-L1 knockout, we transfected mouse PD-L1 Double Nickase plasmid (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) into 4T1 or EMT6 cells using X-tremeGENE transfection reagent. For mouse or human PD-L1 overexpression in 4T1 cells (4T1 mPD-L1 or 4T1 hPD-L1), we transfected the lentivirus carrying pGIPZ-shmPD-L1/mPD-L1 or pGIPZ-shmPD-L1/hPD-L1 into mouse PD-L1 KO 4T1 cells and selected cells using puromycin. For B3GNT3 knockout, we transfected mouse B3GNT3 Double Nickase plasmid (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) into 4T1 or EMT6 cells using X-tremeGENE transfection reagent. After transfection for 24 hours, the medium was replaced with fresh medium and the transfected cells were selected using puromycin (InvivoGen).

qPCR assays

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR assays were performed to measure the expression of mRNA (Lim et al., 2016). Cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and immediately lysed in QIAzol. The lysed sample was subjected to total RNA extraction using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). To measure the expression of mRNA, we synthesized cDNA from 1 μg of purified total RNA (obtained by the SuperScript III First-Strand cDNA synthesis system) using random hexamers (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR was performed using a real-time PCR machine (iQ5; BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). All data analysis was performed using the comparative Ct method. Results were first normalized to internal control β-actin mRNA.

Western blot and immunoprecipitation

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (Li et al., 2012). Image acquisition and quantitation of band intensity were performed using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). For immunoprecipitation, the cells were lysed in buffer (50mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, 150mM NaCl, 5mM EDTA, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40) and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 30 minutes to remove debris. Cleared lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies. For immunocytochemistry, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 minutes, permeabilized in 5% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes, and then stained using primary antibodies. The secondary antibodies used were mouse Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 dye conjugate, or rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 dye conjugate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI blue; Thermo Fisher Scientific). After mounting, the cells were visualized using a multiphoton confocal laser-scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss).

B3GNT3 promoter and luciferase assay

The pEZX-B3GNT3 Luc plasmid was purchased from GeneCopoeia. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) as described previously (Lim et al., 2016). pRL-TK (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was co-transfected as an internal control for normalizing transfection efficiency. After transfection and experimental treatments, cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured using the Dual Luciferase kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein expression from the luciferase assay was determined in the remaining cell lysate using Western blot analysis.

Co-culture and IL-2 expression measurement

Co-culture of Jurkat T cells and tumor cells and IL-2 expression measurement was performed as described previously (Li et al., 2016). To analyze the effect of tumor cells on T cell inactivation, we co-cultured tumor cells with activated Jurkat T cells expressing human PD-1, which were activated with Dynabeads Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Co-cultures at a 5:1 (Jurkat:tumor cell) ratio were incubated for 12 or 24 hours. Secreted IL-2 levels in medium were measured as described by the manufacturer (Human IL-2 ELISA Kits; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Glycosylation analysis of PD-L1

To confirm glycosylation of PD-L1 protein, we treated the cell lysates with PNGase F, Endo H, or O-glycosidase (New England BioLabs) as described by the manufacturer. To stain glycosylated PD-L1 protein, we stained purified PD-L1 protein using the Glycoprotein Staining Kit (Peirce/Thermo Fisher Scientific) as described by the manufacturer.

Internalization of antibody

IgG, STM004, and STM108 antibodies were labeled with pHrodo Red (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as described by the manufacturer. To monitor a dynamic internalization of antibodies on the live cell surface, we incubated BT549 cells expressing PD-L1 WT or 4NQ mutant PD-L1 with the pHrodo Red-labeled antibodies and obtained a time-lapse image every hour for 24 hours using an IncuCyte Zoom microscope (Essen Bioscience). To obtain a higher-resolution image, after adding the pHrodo Red-labeled antibodies and LysoTracker Green (Thermo Fisher Scientific), we obtained a time-lapse image of the cells every 2 minutes for 2 hours using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Live cell single molecule tracking

We used TSUNAMI (Tracking of Single particles Using Nonlinear And Multiplexed Illumination), a feedback-control tracking system that employs a spatiotemporally multiplexed two-photon excitation and temporally demultiplexed detection scheme; this has been described previously (Perillo et al., 2015). Sub-millisecond temporal resolution (50 μs, under high signal-to-noise conditions) and sub-diffraction tracking precision (16/35 nm in xy/z) have been previously demonstrated (Perillo et al., 2015). Tracking can be performed in a live cell to monitor the movements of fluorescent nanoparticle-tagged membrane receptors or ballistically injected fluorescent nanoparticles. In brief, excitation of 800 nm from a Ti:Al2O3 laser (Mira 900; Coherent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used for tracking experiments. STM antibody-conjugated fluorescent nanoparticles were used to label glycosylated PD-L1 for tracking. Biotinylated monoclonal STM antibodies (STM004 and STM108) and control mouse IgG (BioLegend) were mixed at a 1:1 ratio with ~40 nm of NeutrAvidin-labeled red fluorescent nanoparticles (F8770; Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a 1.5% bovine serum albumin/PBS solution (S7806 bovine serum albumin; Sigma-Aldrich). The antibody-conjugated fluorescence nanoparticles (~30nM, the stock solution) can be stored at 4°C for up to 1 week. The photon count rates of the ~40 nm red fluorescent beads were in the range of 200–500 kHz.

For tracking, BT549 cells were seeded onto an optical imaging 8-well chambered coverglass (154534; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a cell density of 1 × 105 cells per well and allowed to grow to ~50% confluence. Before tracking experiments, cells were stained with a mixture of Hoechst 33258 (H3569, Thermo Fisher Scientific; 1:1000 dilution in DMEM) and CellMask Deep Red (C10046, Thermo Fisher Scientific; 1:1000 dilution in DMEM) for 10 minutes at 37°C. After membrane staining, the staining buffer was replaced with the antibody solution (antibody-conjugated fluorescent nanoparticles at 100pM) diluted from the stock solution (30nM). The reaction was incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C and the antibody solution was subsequently removed. Sample cells were washed twice using PBS to remove the unbound fluorescent nanoparticles. Upon completion of membrane staining and antibody labeling, the chambered coverglass was immediately placed on the TSUNAMI microscope for tracking experiments. Two to four trajectories (duration ranged from 1–10 minutes) were typically obtained from each well. The volumes of all solutions and washing buffers used in staining were 200 μl per well. The construction of the laser scanning image has been described previously (Perillo et al., 2015). All data processing was performed in MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) and saved in a binary format. The trajectory raw data contained photon counts and voltage outputs from the actuators (i.e., the xy scanning galvo mirrors [6125H; Cambridge Technology, Bedford, MA, USA] and the objective z-piezo stage [P-726 PIFOC, PI]) at each 5-ms time point. Trajectories were plotted by simply connecting the particle positions of consecutive time points.

Production of anti-gPD-L1 antibodies

Hybridomas producing monoclonal antibodies generated against glycosylated human PD-L1 were obtained by the fusion of SP2/0 murine myeloma cells with spleen cells isolated from human PD-L1–immunized BALB/c mice (n = 6; Antibody Solutions, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) according to standardized protocol. Before fusion, sera from the immunized mice were validated for binding to the PD-L1 immunogen using FACS analysis. Monoclonal antibody (mAb)-producing hybridomas were generated. The hybridomas that produced antibodies were again tested for specificity. More than 100 candidates mAb-producing hybridomas were selected and grown in ADCF medium, and the monoclonal antibody-containing supernatant was concentrated and purified. The purified mAbs were tested for their ability to neutralize or inhibit the interaction between PD-L1 and PD-1 (PD-L1/PD-1 binding interaction) using a live-cell imaging assay, Incucyte (Essen Bioscience). This assay showed that of the mAbs tested, 16 mAbs completely blocked the binding of PD-L1 to PD-1. To identify the mAbs among these that were specific only for glycosylated PD-L1 antigen and did not cross-recognize non-glycosylated PD-L1, we placed both glycosylated human PD-L1 protein and non-glycosylated PD-L1 (i.e., PD-L1 protein treated with PNGase F) on a solid phase and tested the mAbs for binding affinity to the PD-L1 antigens.

Identification of antibody binding regions

To identify the regions of monoclonal gPD-L1 antibodies which bound to glycosylated PD-L1, wild type (glycosylated) PD-L1 (PD-L1 WT), and the glycosylation variant proteins N35/3NQ, N192/3NQ, N200/3NQ, and N219/3NQ were overexpressed in PD-L1 knockdown BT549 cells. As determined by Western blot, some MAbs recognized particular PD-L1 mutants with higher levels of binding compared with other PD-L1 mutants, demonstrating that such MAbs were site-specific. For example, MAb STM004 recognized the N35/3NQ mutant, demonstrating that this antibody bound to the N35 region of PD-L1. Further, Western blot analysis using liver cancer cell lysate also revealed a differential pattern of PD-L1 glycosylation for a representative anti-gPD-L1 antibody such as STM004. The histopathologic relevance of these MAbs was further demonstrated by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining. In a cytospin staining analysis, the anti-gPD-L1 monoclonal antibodies consistently recognized and bound the glycosylated portion of the PD-L1 protein, but not unglycosylated PD-L1 protein. In a human BLBC patient sample, the anti-gPD-L1 monoclonal antibodies also showed membrane and cytoplasm staining in a 1:30 ratio.

KD determination and binning by Octet

For high-throughput KD screening, antibody ligand was loaded to the sensor via 20nM solution. The baseline was established in PBS containing 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (assay buffer), and the association step was performed by submerging the sensors in a single concentration of analyte in assay buffer. Dissociation was performed and monitored in fresh assay buffer. All experiments were performed with sensor shaking at 1,000 rotations per minute. ForteBio (Menlo Park, CA, USA) data analysis software was used to fit the data to a 1:1 binding model to extract an association rate and dissociation rate. KD was calculated using the ratio kd:ka. In a typical epitope binning assay, antigen PD-L1-His (10nM) was pre-incubated with the second antibody (10nM) for 1 hour at room temperature. Control antibody (20nM) was loaded onto AMC sensors (ForteBio) and the remaining Fc-binding sites on the sensor were blocked with a whole mouse IgG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA). The sensors were exposed to pre-incubated antigen-second antibody mixture. Raw data were processed using ForteBio Data Analysis Software 7.0 and the antibody pairs were assessed for competitive binding. Additional binding by the second antibody indicated an unoccupied epitope (non-competitor), and no binding indicated epitope blocking (competitor).

Immunohistochemical staining of human tumor tissues

Human breast tumor tissue specimens were obtained following the guidelines approved by the Institutional Review Board at MD Anderson, and written informed consent was obtained from patients in all cases at the time of enrollment. One hundred and twelve archived, paraffin-embedded breast carcinoma slides were obtained from the Department of Pathology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was performed as described previously (Li et al., 2016). Briefly, tissue specimens were incubated with antibodies against glycosylated PD-L1 (STM108), p-EGFR, or B3GNT3 and a biotin-conjugated secondary antibody and then incubated with an avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex. Visualization was performed using amino-ethylcarbazole chromogen. For statistical analysis, the Fisher exact test and Spearman rank correlation coefficient were used, and a p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. According to histologic scoring, the intensity of staining was ranked into one of four groups: high (score 3), medium (score 2), low (score 1), and negative (score 0).

Epitope mapping by mass spectrometry

Epitope mapping for the mouse monoclonal anti-gPD-L1 antibodies STM004 and STM108 was performed by CovalX AG (Switzerland). For the epitope mapping of the antigen-antibody complex, 5 μl of the antigen sample (4μM) was mixed with 5 μl of the antibody sample (2μM) to obtain an antibody/antigen mix with a final concentration of 2μM/1μM. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 180 minutes. In the first step, 1 mg of d0 cross-linker was mixed with 1 mg of d12 cross-linker. The 2-mg prepared was mixed with 1 ml of DMF to obtain a 2 mg/ml solution of DSS d0/d12. Then, 10 μl of the antibody/antigen mix prepared previously was mixed with 1 μl of the solution of cross-linker d0/d12 (2 mg/ml). The solution was incubated for 180 minutes at room temperature to complete the cross-linking reaction. Next, 10 μl of the cross-linked solution was mixed with 40 μl of ammonium bicarbonate (25mM, pH 8.3), and 2 μl of DTT (500mM) was added to the solution. The mixture was incubated for 1 hour at 55°C, and then 2 μl of iodoacetamide (1M) was added prior to 1 hour of incubation time at room temperature in a dark room. After incubation, the solution was diluted 1/5 by adding 120 μl of the buffer used for the proteolysis. The reduced/alkylated antigen was mixed with trypsin, chymotrypsin, ASP-N, elastase, or thermolysin (Roche Diagnostics). The proteolytic mixture was incubated overnight at 37°C. The samples are analyzed by High-Mass MALDI analysis immediately after crystallization. The MALDI TOF MS analysis was performed using CovalX’s HM4 interaction module with a standard nitrogen laser and focusing on different mass ranges, from 0 to 2000 kDa. For the analysis, the following parameters were applied: linear and positive mode; ion source 1: 20 kV; ion source 2: 17 kV; lens: 12 kV; pulse ion extraction: 400 ns for mass spectrometer; gain voltage: 3.14 kV; and acceleration voltage: 20 kV for HM4. The cross-linker peptides were analyzed using Xquest version 2.0 and Stavrox 2.1 software.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data in bar graphs represent mean (±standard deviation) fold change relative to untreated or control groups, for three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Ver. 20, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Level 3 normalized TCGA RNAseq_V2 gene expression data was downloaded from Broad Institute GDAC website (http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/). Pearson correlation was used to study correlation between expression of N-glycosyltransferase and EGFR using an arbitrary cutoff of Pearson correlation coefficient 0.3 to select best correlated genes in subtype-defined breast cancer samples (Cancer Genome Atlas, 2012). Student’s t- test was used to evaluate the differences in EGFR and B3GNT3 expression in breast cancer subtypes.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

N/A

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

N/A

Supplementary Material

SIGNIFICANCE.

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) patients initially respond to conventional chemotherapy, but the disease frequently relapses, leading to the worse outcome than patients with other breast cancer subtypes. Immune checkpoint blockade has demonstrated success in other cancers, but remain limited in TNBC treatment. Here, we identified a glycosylation event on PD-L1 essential for its interaction with PD-1 and subsequent suppression of T cell activities. We isolated a glycosylation-specific antibody that can efficiently internalize PD-L1 for endocytosis and generated an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) against glycosylated PD-L1, which induces potent anti-tumor activities in TNBC models in vitro and in vivo. Our findings open a direction to target glycosylation of co-inhibitory ligand/receptor as a therapeutic strategy.

HIGHLIGHTS.

N linked-glycosylation is required for physical contact between PD-L1 and PD-1

EGF/EGFR stimulates PD-L1 glycosylation via B3GNT3 glycosyltransferase

Anti-glycosylated-PD-L1 induces PD-L1 internalization

Anti-glycosylated-PD-L1-ADC possesses potent toxicity as well as bystander effects

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by the following: National Institutes of Health grants CCSG CA16672 and R21 CA193038 (to H.-C.Y. and M.-C.H.); Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (RP160710); National Breast Cancer Foundation, Inc.; Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BRCF-17-069; to M.-C.H. and G.N.H.); Patel Memorial Breast Cancer Endowment Fund; The University of Texas MD Anderson-China Medical University and Hospital Sister Institution Fund (to M.-C.H.); Ministry of Science and Technology, International Research-intensive Centers of Excellence in Taiwan (I-RiCE; MOST 105-2911-I-002-302); Ministry of Health and Welfare, China Medical University Hospital Cancer Research Center of Excellence (MOHW106-TDU-B-212-144003); Center for Biological Pathways; Susan G. Komen for the Cure Postdoctoral Fellowship (PDF12231298; to S.-O.L.); Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Korean government (MSIP; NRF-2011-357-C00140; to S.-O.L.); and the National Research Foundation of Korea grant for the Global Core Research Center funded by the Korean government (MSIP; 2011-0030001; to J.-H.C).

Footnotes

Author contributions: C.-W.L. and S.-O.L. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; J.-H.C., W. X., L.-C.C., T.K., S.-S.C., H.-H. L., C.-K.C., Y.-L.L., H.H., T.Y., C.-W.K., K.-H.K., J.-M. H., and J.Y., performed experiments and analyzed data; Y. Wu provided patient tissue samples; J.L.H. and H.Y. provided scientific input and wrote the manuscript; A.A.S. and G. N. H. provided scientific and clinical input; E.M.C., Y.-S.K., A.H.P., S.S.Y. produced and characterized antibodies; M.-C.H. supervised the entire project, designed the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests: M.-C.H. received a sponsored research agreement from STCube Pharmaceuticals, Inc. through The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. C.-W.L., S.-O.L., and M.-C.H. are inventors listed on patent applications under review. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams S, Schmid P, Rugo HS, Winer EP, Loirat D, Awada A, Cescon DW, Iwata H, Campone M, Nanda R, et al. Phase 2 study of pembrolizumab (pembro) monotherapy for previously treated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC): KEYNOTE-086 cohort A. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35:1008–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Altschuler Y, Kinlough CL, Poland PA, Bruns JB, Apodaca G, Weisz OA, Hughey RP. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis of MUC1 is modulated by its glycosylation state. Molecular biology of the cell. 2000;11:819–831. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.3.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano N. Glycosidase inhibitors: update and perspectives on practical use. Glycobiology. 2003;13:93R–104R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, Powderly JD, Picus J, Sharfman WH, Stankevich E, Pons A, Salay TM, McMiller TL, et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:3167–3175. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Han X. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy of human cancer: past, present, and future. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3384–3391. doi: 10.1172/JCI80011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung JC, Reithmeier RA. Scanning N-glycosylation mutagenesis of membrane proteins. Methods. 2007;41:451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croci DO, Cerliani JP, Dalotto-Moreno T, Mendez-Huergo SP, Mascanfroni ID, Dergan-Dylon S, Toscano MA, Caramelo JJ, Garcia-Vallejo JJ, Ouyang J, et al. Glycosylation-dependent lectin-receptor interactions preserve angiogenesis in anti-VEGF refractory tumors. Cell. 2014;156:744–758. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curiel TJ, Wei S, Dong H, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P, Krzysiek R, Knutson KL, Daniel B, Zimmermann MC, et al. Blockade of B7-H1 improves myeloid dendritic cell-mediated antitumor immunity. Nature medicine. 2003;9:562–567. doi: 10.1038/nm863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirix LY, Takacs I, Nikolinakos P, Jerusalem G, Arkenau HT, Hamilton EP, von Heydebreck A, Grote HJ, Chin K, Lippman ME. Abstract S1-04: Avelumab (MSB0010718C), an anti-PD-L1 antibody, in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer: A phase Ib JAVELIN solid tumor trial. Cancer Research. 2016;76:S1-S1-04. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4537-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, Tamura H, Hirano F, Flies DB, Roche PC, Lu J, Zhu G, Tamada K, et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nature medicine. 2002;8:793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H, Zhu G, Tamada K, Chen L. B7-H1, a third member of the B7 family, co-stimulates T-cell proliferation and interleukin-10 secretion. Nature medicine. 1999;5:1365–1369. doi: 10.1038/70932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Shi LZ, Zhao H, Chen J, Xiong L, He Q, Chen T, Roszik J, Bernatchez C, Woodman SE, et al. Loss of IFN-gamma Pathway Genes in Tumor Cells as a Mechanism of Resistance to Anti-CTLA-4 Therapy. Cell. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner OB, Baum LG. Galectin-glycan lattices regulate cell-surface glycoprotein organization and signalling. Biochemical Society transactions. 2008;36:1472–1477. doi: 10.1042/BST0361472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]