Abstract

New state-level health insurance markets, denoted Marketplaces, created under the Affordable Care Act, use risk-adjusted plan payment formulas derived from a population ineligible to participate in the Marketplaces. We develop methodology to derive a sample from the target population and to assemble information to generate improved risk-adjusted payment formulas using data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey and Truven MarketScan databases. Our approach requires multi-stage data selection and imputation procedures because both data sources have systemic missing data on crucial variables and arise from different populations. We present matching and imputation methods adapted to this setting. The long-term goal is to improve risk-adjustment estimation utilizing information found in Truven MarketScan data supplemented with imputed Medical Expenditure Panel Survey values.

Keywords: Matching, Imputation, Prediction, Risk adjustment

1 Introduction

The most innovative and contentious feature of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), a.k.a. Obamacare, was the creation of highly regulated state-level individual health insurance markets, originally known as Exchanges. More recently, federal officials refer to them as insurance Marketplaces. The name Marketplaces is used in most current discussions, and thus we use that term in this paper. The Marketplaces are intended to provide affordable comprehensive coverage to persons and families without access to qualified health insurance through their employer or other source. Although low-income persons are eligible for subsidies, Marketplaces are designed to be self-financing, meaning, in each state, the revenues generated through premiums (including any federal subsidy) are equal to the payments to the participating health plans. Premiums paid by individuals can depend only on age (not sex), geography, smoking status, and family composition [7]. For this financing system to pay fairly and convey appropriate incentives to plans, health plans drawing a sicker, more costly population need to be paid more than plans with a healthier, less costly set of enrollees. Recognizing this, the ACA required states to risk adjust plan payments in order to redistribute premium revenues to plans with more costly enrollees. The US Department of Health and Human Services commissioned researchers to modify the risk adjustment system originally developed for the Medicare population for use among the younger population enrolling in the Marketplaces [7].

The Marketplace risk-adjustment models for payment are estimated with ordinary least squares regressions on data from the same source used in this paper. Unlike premiums paid by enrollees, models for plan spending depend on three sets of indicator variables: age-sex categories, diagnostic conditions, and selected disease interactions. Partly in response to the difficulties in developing such a complex risk adjustment system, all states but Massachusetts (which had a risk-adjustment system in place for its precursor of national health care reform) have adopted the formula proposed by the federal government [7].

Development of a risk-adjustment system for Marketplaces raised another special problem. Marketplaces needed a risk adjustment system in place before the health plans went live in January 2014; in other words, before the characteristics of the enrollees were known and before states had any health care cost experience with which to calibrate risk adjustment models. When the federal government estimated its proposed risk adjustment formula, it used 2010 data from employer-sponsored health insurance plans – this is a population known not to be eligible for Marketplace participation. Eventually, Marketplaces will accumulate data on enrollment and health cost experience that can be used as a basis of risk adjustment in the Marketplaces.

This paper proposes empirical methods to improve risk adjustment and can be implemented immediately. We use more recently updated data than was available to the federal government when the current risk-adjustment models were estimated. Our main innovation lies in the selection and creation of the sample to be used as a basis for estimation. There are two main statistical challenges: matching and imputation, complicated by heterogeneous databases and their sizes. We extract information from two non-overlapping data sources to construct a set of individuals with the characteristics of those who are likely to participate in Marketplaces. However, only one data source includes Marketplace-eligible subjects and the requisite information necessary to strictly classify them as Marketplace eligible. Unfortunately, this source is missing crucial information on health conditions required for risk adjustment payments. The other data source contains detailed health condition information but excludes Marketplace eligible subjects. We use propensity-score matching methods in combination with imputation for systemically missing data to create information needed to estimate valid risk-adjustment models.

The combined use of matching and imputation in a large “big data” health care database is a novel practical problem not previously encountered. Researchers have begun to address these issues separately for their research questions in large health databases [30,15,4], while we contribute a joint approach necessary to answer our risk adjustment research question. We discuss methods to create an appropriate sample for risk adjustment in this setting.

2 Data Sources

The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) is a nationally representative survey of the civilian non-institutionalized U.S. population, with information on approximately 33,000 individuals annually. It contains detailed sociodemographic and insurance coverage information that also permits identification of Marketplace-eligible individuals. Each observation has an integer-valued weight establishing how many individuals they represent in the population. MEPS data are not suitable for estimating a risk adjustment system for Marketplaces. The publicly-available MEPS does not contain sufficient detail on health events to determine the health condition category information needed for the development of risk-adjustment models. Furthermore, MEPS data are subject to underreporting by participants. Finally, there are far too few MEPS observations to calibrate the complex risk adjustment formula.

We pooled MEPS data from the 2004–2005 survey through the 2010–2011 survey and categorized the population of individuals and families who would be eligible for Marketplaces based on income, insurance, Medicaid eligibility, and employment status using the requirements outlined in the ACA [11]. We required that each person in MEPS was present for two years in the data. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied annually, and we assigned a subject as Marketplace eligible if they satisfied the criteria in either year. We additionally considered only adults aged 21–64, as children have a separate risk-adjustment system, and included adults in households earning at least 138 percent of the federal poverty level as well as adult children under age 26 in parental households with income of at least 205 percent of the federal poverty level.

We excluded individuals continuously enrolled in Medicaid. Our total sample of Marketplace-eligible subjects contained 30,154 individuals, with non-Marketplace-eligible subjects numbering 28,179, all with two years of data.

The Truven MarketScan (MarketScan) database is one of the largest longitudinal enrollment and claims databases in the United States, generating information for between 17 and 51 million people annually [1]. Data are submitted by both private health plans and employers, and capture employees and dependent family members covered under the same plan. Claims information includes the date and site of service, procedures rendered and an indicator for whether the claim was paid through a capitated contract. Inpatient facility claims are assigned Medicare-equivalent diagnosis-related groups. Inpatient professional claims and outpatient claims are assigned current procedural terminology procedure codes, and drug claims are assigned 11-digit national drug code identifiers. The database also contains enrollee demographic information including age, sex, enrollee state and census region, type of insurance plan, and out-of-pocket spending.

We used data for persons with two years of continuous coverage from years 2011–2014. Our total sample contains more 10.9 million persons. We constructed Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) variables, the basis of the federal risk adjustment system, using ICD-9-CM codes [7]. While MarketScan was the basis of estimates for federal Marketplace risk adjustment systems, it contains no Marketplace-eligible individuals, nor the crucial information used to identify Marketplace-eligible individuals. Table 1 contains a summary of the data sources and variables.

Table 1.

Characteristics of data sources.

| Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) |

Truven MarketScan (MarketScan) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Nationally representative U.S. civilian population | Commercially insured U.S. working adults & dependents | |

| Eligibility Variables (C) | Income Insurance Medicaid Eligibility Employment Status | ||

| MEPS Variables (A) | Self-reported Health Status Marital Status | ||

| MarketScan Variables (D) | Heirarchical Condition Categories | ||

| Common Variables (V) | |||

| Age | |||

| Sex | |||

| (W) | Metropolitan Statistical Area | ||

| Region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West) | |||

| Inpatient Healthcare Diagnosis Codes | |||

| (Y) | Total Annual Expenditures | ||

3 Methods

Define

as an unobserved underlying full data experimental unit with corresponding distribution containing Marketplace-eligible and non-Marketplace-eligible individuals. V denotes variables common to the two data sources, such as age, sex, and health care spending; D are 74 binary HCC variables for use in the risk adjustment formula; C are variables used to assign Marketplace eligibility; A are additional survey variables that may be useful for risk adjustment, but are not currently used for this purpose; and M is an indicator of Marketplace eligibility. Let W ⊂ V, where W contains all variables common to both databases except total annual expenditures, which we denote as Y. Total annual expenditures is the outcome of interest in our risk adjustment formula, and W is the subset of variables in V that are used to predict spending in the risk adjustment formula, along with variables D.

Given that our full data X is not fully observed, we now define the observed data structure for those subjects who met our inclusion criteria in both the MarketScan database and MEPS survey data. The observed data structure on a randomly sampled subject in the MarketScan database is represented as:

where Δ is an indicator for inclusion in the MarketScan database. Therefore, Δ = 1 for all subjects in MarketScan, and Δ = 0 for all subjects in MEPS. Recall that M = 0 for all subjects in MarketScan. Similarly, the data structure for MEPS is represented

Of note, we have both Marketplace-eligible and non-Marketplace-eligible individuals available in the MEPS database.

The 74 binary HCC variables D are indicators for medical conditions. Conditions with a prevalence of at least 1% were:

-

–

breast (age 50 and over) and prostate cancer, benign/uncertain brain tumors, and other cancers and tumors;

-

–

inflammatory bowel disease;

-

–

rheumatoid arthritis and specified autoimmune disorders;

-

–

major depressive and bipolar disorders;

-

–

seizure disorders and convulsions; and

-

–

specified health arrhythmias.

The variables in W were constructed using two years of data. For variables that changed over time, such as inpatient diagnoses, observations were assigned a “yes” indicator if they had the diagnosis in either year. Sex, geography, and age were assigned based on year 1 information. Table 2 provides a summary of common variables V among MarketScan and MEPS.

Table 2.

Summary information of common variables (V) in two health care databases.

| Truven MarketScan (MarketScan) |

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS)* |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Not Marketplace Eligible (M = 0) 10,976,994 |

Marketplace Eligible (M = 1) 30,154 |

Not Marketplace Eligible (M = 0) 28,179 |

| Male (%) | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.43 |

| Metropolitan | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| Statistical Area | |||

| Age | |||

| 21 to 34 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.30 |

| 35 to 54 | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.51 |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.17 |

| Midwest | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.21 |

| South | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.37 |

| Inpatient Diagnoses | |||

| Heart Disease | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Cancer | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Diabetes | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Other | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.16 |

| Mean Total Annual | $10,529 | $5,755 | $10,055 |

| Expenditures [SD] | [$28,686] | [$15,109] | [$22,410] |

unweighted data

We drew a matched sample of subjects from MarketScan that had similar characteristics to those who were Marketplace eligible in MEPS. This involved the use of W from both sources to select individuals in MarketScan such that the distribution of W was similar in MEPS and MarketScan. The ideal set of variables to assign eligibility is C (income, insurance, Medicaid status, and employment), however, C is not available in MarketScan. The variables W may or may not be acceptable substitutes for C. Current implementations of risk-adjustment models do not have any restrictions on the MarketScan data to produce a sample similar to the target population. Thus, creation of this matched sample alone is an improvement on existing techniques versus using the entire MarketScan database.

The combined use of the two databases, however, afforded an opportunity to incorporate more information. We used imputation to assign values for A in the selected MarketScan data based on the Marketplace-eligible MEPS data. This provided supplementary variables for determining the risk adjustment formula, and an exploration of whether self-reported health and marital status may further improve prediction. It is important to note that these variables would not be available for risk adjustment at the state or federal level. Thus, we investigated whether the lack of these variables in risk adjustment was a detriment to construction of a risk adjustment formula. We additionally examined whether the imputed variables were useful for assessing the performance of the risk adjustment model for subgroups identified by imputed variables. Although a variable such as “self-assessed health status” is impractical for use in a risk adjustment payment formula, it is very useful to know whether a particular risk adjustment formula pays fairly for subgroups with low health status.

Sample selection and data construction involved three main steps:

Development of a propensity score function based on both Marketplace-eligible and non-Marketplace-eligible individuals in MEPS with W. Using these fixed parameter estimates, we assigned propensity scores to the observations in the MarketScan database.

Selection of K MarketScan subjects for each Marketplace-eligible MEPS subject using propensity score matching. K is a scaled nationally-representative weight assigned to MEPS observations. The resulting MarketScan sample contained the observations we used for risk adjustment.

Imputation of values for survey variables A in the matched MarketScan sample using information from the Marketplace-eligible MEPS subjects.

After building these data sets, we estimated risk adjustment prediction functions and evaluated their performance.

3.1 Matching

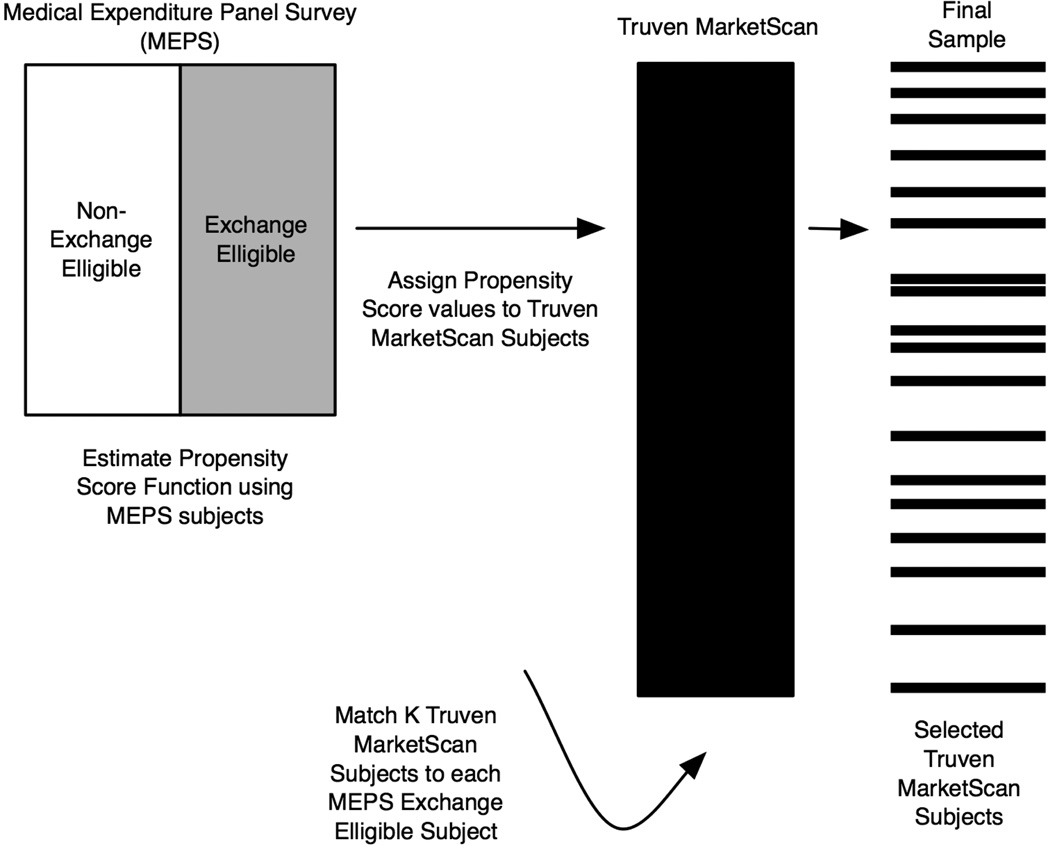

The first two steps in the construction of an improved data set for risk adjustment in Marketplaces made use of propensity score and matching methods from the statistical literature. While these methods have been commonly used to construct matched samples in the causal inference literature [2,22–24], their implementation for sample selection for the purpose of developing a risk adjustment model is novel. In the first stage, we developed a propensity score function for Marketplace eligibility using Marketplace-eligible and non-Marketplace-eligible individuals in MEPS. Recall that the MarketScan data only contained subjects who were not Marketplace eligible; thus we assigned propensity score values to all observations in MarketScan using the function generated from MEPS data. In the second step, we matched K MarketScan subjects to each Marketplace-eligible MEPS subject based on their propensity score values, where K is a scaled nationally-representative weight given to each MEPS observation (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Propensity score and matching study design for sample selection

The matching methods we considered rely on the propensity score for dimension reduction [23]. We defined the propensity score as the probability of Marketplace eligibility given the set of common covariates W:

We have the property that M ⊥ W | ps(W); M and W are conditionally independent given ps(W). This propensity score can be estimated with standard techniques, such as parametric regression models, or advanced data-adaptive machine learning methods [9,16]. One of the simplest estimators of ps(W) stratifies by all variables in W and then averages across these strata. Even with a few covariates, many bins will have a limited number of observations or no observations, making this nonparametric maximum likelihood estimator ill-defined. It also overfits the data, which leads to poor performance in finite samples. To handle this curse of dimensionality, we proposed a dimension reduction of W and applied a maximum likelihood estimator using regression in a parametric working statistical model. Alternatively, machine learning techniques, such as the ensembling super learner [31,16], could be implemented. The current computing framework of health insurance Marketplaces would make replication of these machine learning approaches difficult in practice, thus we do not pursue it here, although we have additional work exploring this area.

Once the propensity score was estimated for all subjects, we matched K MarketScan subjects to each Marketplace-eligible subject in MEPS with a small caliper, c,

This was the distance allowed between the propensity scores for each match in MarketScan to their respective MEPS observation [25]. The weight from MEPS was scaled by a factor of 1,000 for computational ease. Therefore, K = weight=1, 000, where the maximum value of K was 67 in our K-to-1 matching. Given the size of the MarketScan database (10.9 million observations), incomplete matching was not an issue, even when K was large. There were an adequate number of matched subjects in MarketScan for each MEPS subject, even with a small caliper. For a comparison of propensity score methods for matching, we refer to other literature [2,6,14,22,31].

After matching, the observed data structure in our matched MarketScan sample was now defined by:

for selected MarketScan subjects. Here ps(W)(·) was a dimension reduction of W, and the approximate equivalence of

was defined by the caliper c. The sampling distribution of the new matched data structure was described as above with

Thus, the matched data set contained n independent and identically distributed observations O1, …, On with sampling distribution P0. The cluster containing K matched subjects was the experimental unit, no longer an individual subject.

An alternative strategy to matching based on ps(W) would be to use appearance in the two databases as a proxy for Marketplace eligibility to assign a match. Because all MarketScan subjects were not Marketplace eligible (M = 0) and all MEPS subjects considered had M = 1, this was a possible strategy for estimation of a proxy propensity score (pps). Indeed, had non-Marketplace-eligible MEPS subjects not been available, this would have been the only way to approximate Marketplace eligibility. In this setting, we estimated

with only the Marketplace-eligible MEPS subjects and the MarketScan database (where MEPS=0).

3.2 Imputation

The scope of the missing data on the survey variables A in the MarketScan matched sample provided a challenge. The survey variables A were systemically missing, meaning none of the observations in our MarketScan matched sample contained information on A [15]. We wished to estimate improved risk-adjustment formulas using additional information A in our MarketScan matched sample, but it did not exist. While other variables could have been considered, for the purposes of our analyses, we considered two.

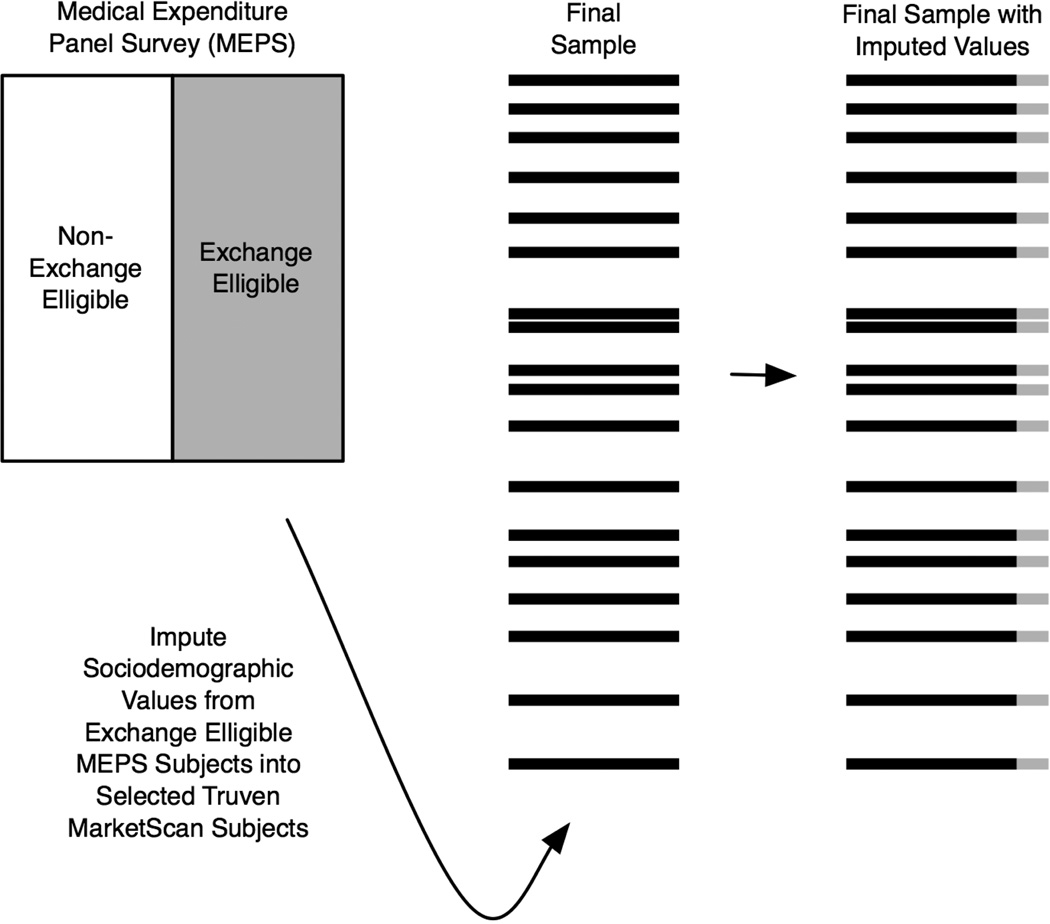

in the Marketplace-eligible MEPS subjects to impute values for A in our MarketScan matched sample (Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Imputation design

Several methods of missing data imputation were not directly applicable, including “carrying forward” the most recent value, mean value imputation, and random imputation [10]. Carry forward was adapted to this setting by assigning the value for A from MEPS to each of the K MarketScan matches. This yielded a data set where the matched MarketScan sample observations have values

for all subjects.

Imputing the mean value for an observation also did not apply without modification, because a mean value could not be computed within the MarketScan matched sample observations. Imputing the overall mean value from MEPS would have yielded a data set with identical values for all subjects, and would therefore be of no value. However, we could impute the mean value from MEPS for all subjects within c of the propensity score. Mean value imputation was not considered in our study in favor of the more commonly used random imputation. Random imputation was adapted such that a randomly selected subject from MEPS, within c of the matched MarketScan observation, was chosen and that subject’s value for A was used to impute A for that matched MarketScan observation.

Random regression imputation posits a regression equation for each variable to be imputed, including random error in these equations. We instead examined multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) [13]. This technique involved imputing values for the set A = {A1, A2} in the matched MarketScan sample using iterative regression. The procedure built nested regressions containing random error. It proceeded by imputing A1 given fixed variables W; then A2 given the newly imputed A1 and fixed variables W. This iterated until a defined level of convergence, which has been suggested typically occurs after 10 cycles [13]. The imputed values after the last cycle were kept, and the procedure was repeated until the desired number of complete data sets were created, with the recommended number generally being 5–10 sets [30].

Multiple imputation has a key advantage over single imputation methods in that it incorporates both between- and within-imputation uncertainty in parameter estimates, which is important in constructing a risk adjustment payment formula. Other types of multiple imputation are available, each with benefits and drawbacks compared to MICE. We refer to the substantial multiple imputation literature for additional reading [8,10,12,26–30].

Imputation using so-called “logical rules” [5] might work for a variable such as self-reported health status, where we would assign each observation in the MarketScan matched sample to have lesser self-reported health if they have any reported diagnoses of heart disease, cancer, or diabetes. However, this would result in a variable that was merely a summary of existing variables in the matched sample, thereby unlikely to provide further information for risk adjustment. Additionally, attempting to use logical rules for marital status does not have an obvious extension given the available variables.

We selected MICE, performed with 10 complete data sets, for its combination of favorable traits, including the feasibility of implementing it in a large-scale “big data” health care database and its positive performance in finite samples while incorporating two types of uncertainty [13,30]. For comparison purposes, we also considered carry forward, random imputation, and random regression imputation along with MICE, all with the modifications described above, for the imputation of marital status and self-reported health status in the matched MarketScan sample.

3.3 Risk-Adjustment Estimation

Current risk-adjustment formulas use W and D for estimation. We propose the additional use of A, the survey variables imputed from MEPS, to potentially improve risk adjustment by using A as additional regressors and to define subpopulations. For comparison purposes, we estimated a parametric regression risk-adjustment formula with total annual expenditure as the outcome, and W and D as explanatory variables in both an unmatched sample from MarketScan and our matched MarketScan samples. We also estimated a risk adjustment formula in the MarketScan matched samples using A. (Here, we have matched samples indexed by the type of imputation procedure used to create A.). Therefore, we estimated both

We compared our prospective risk adjustment formulas in terms of a loss function, which assigns a measure of performance to a candidate function Q when applied to an observation OMatched = O. Explicitly, it is a function L given by

We use the L2 squared error loss functions

where Y = Total Annual Expenditure. The minimizer of the L2 loss is the conditional mean of Y, which was why we selected this loss function. Our parameters of interest Q(W;D) and Q(W,D,A) were then defined as the minimizers of their respective expected squared error loss: arg minQEL(O,Q), where L(O,Q) = (Y − Q(·))2. We had multiple estimates for Q(·) and thus prefered the estimator for which

was smallest.

4 Results

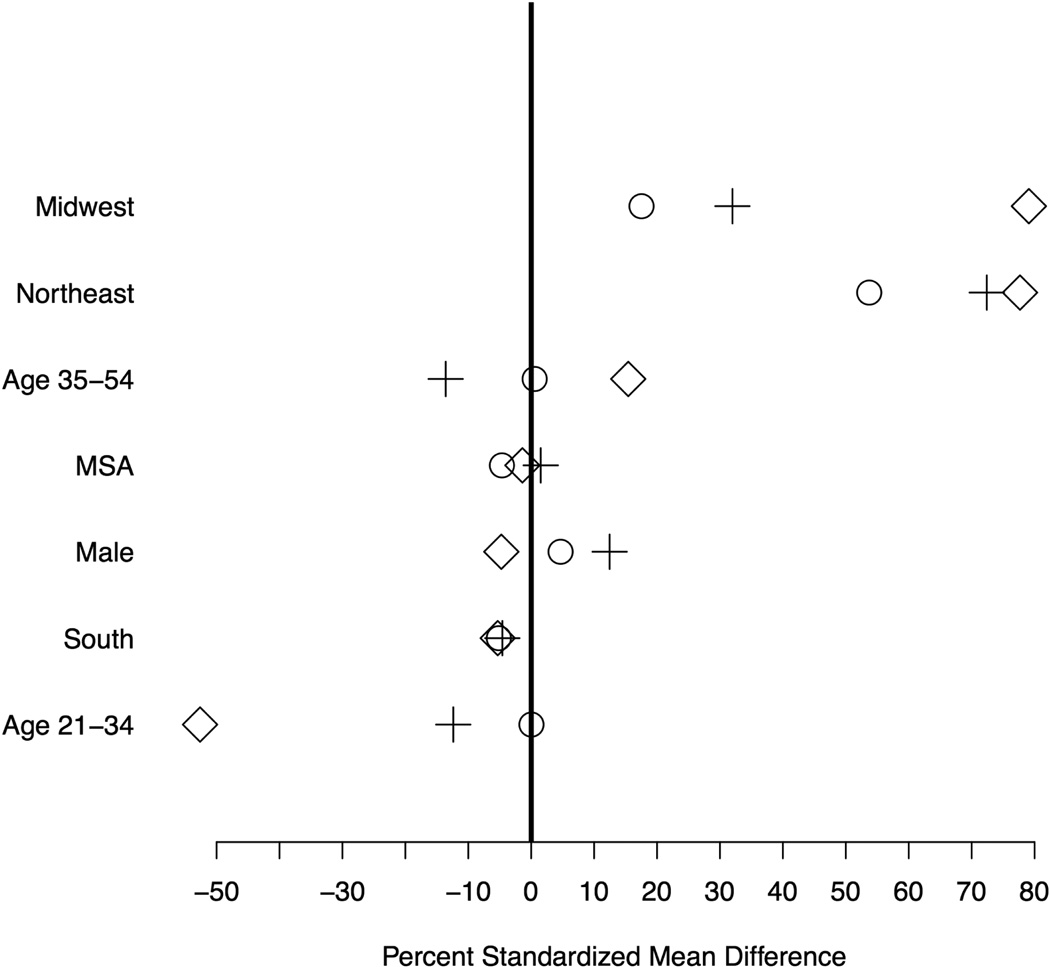

Our ps(W)-based matched MarketScan sample contained 319, 372 observations with a K-to-1 match based on 30,154 MEPS observations. These 319, 372 observations were drawn from the full MarketScan database of 10,976,994 non-Marketplace-eligible subjects. The value of c = 0.065, on the logit scale. Summary information on select variables for the ps(W)-based and pps(W)-based matched samples compared to an unmatched sample of equal size is presented in Table 3. The percent standardized differences (displayed in Figure 3) demonstrated that, in most cases, the ps(W)-based matched sample improved on an unmatched sample of equal size extracted from the complete database. However, these differences were still high.

Table 3.

Summary information on select variables in the matched samples (N = 319, 372).

| Unmatched | ps(W) Matched | pps(W) Matched | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 0.48 | 0.54 | 0.51 |

| Metropolitan | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.83 |

| Statistical Area | |||

| Age | |||

| 21 to 34 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.36 |

| 35 to 54 | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.49 |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.18 |

| Midwest | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.21 |

| South | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.37 |

| Mean Total Annual | $10,524 | $9,924 | $8,961 |

| Expenditures [SD] | [$28,498] | [$27,231] | [$21,768] |

Fig. 3.

Percent standardized mean differences in unmatched MarketScan sample (diamond), ps(W) matched MarketScan sample (plus), and pps(W) matched MarketScan sample (circle). The variables are ordered by largest positive percent standardized mean difference in the unmatched MarketScan sample. Values for basic diagnosis variables are omitted given their rare values (≤ 0.1%) in the MEPS data.

The pps(W)-based matched MarketScan sample improved on both the ps(W)-based matched MarketScan sample and the unmatched MarketScan sample, and, in all cases except Midwest and Northeast regions, the percent standardized mean differences were less than 10%. The value of c = 0.122 in this sample. This result was not entirely surprising, as the ps(W)-based matched MarketScan sample used a propensity score derived from only MEPS data. Therefore, the assigned ps(W)-based propensity scores for MarketScan subjects lacked information about the MarketScan data distribution. These results also reinforce the fact that the non-Marketplace-eligible MEPS subjects differ from the MarketScan subjects, despite both groups being non-Marketplace-eligible, as seen in Table 2.

However, our goal was to reproduce a sample that had the characteristics of the Marketplace-eligible MEPS subjects, thus, this lack of homogeneity between the non-Marketplace-eligible groups was less concerning. The proxy-matched sample using pps(W) approximated the unknown Marketplace-eligibility assignment well, despite being mis-specified. In both samples, approximately 2% of subjects were matched more than once. The estimated functions or the two propensity regressions are given below, with

for the ps(W)-based matched MarketScan sample, and

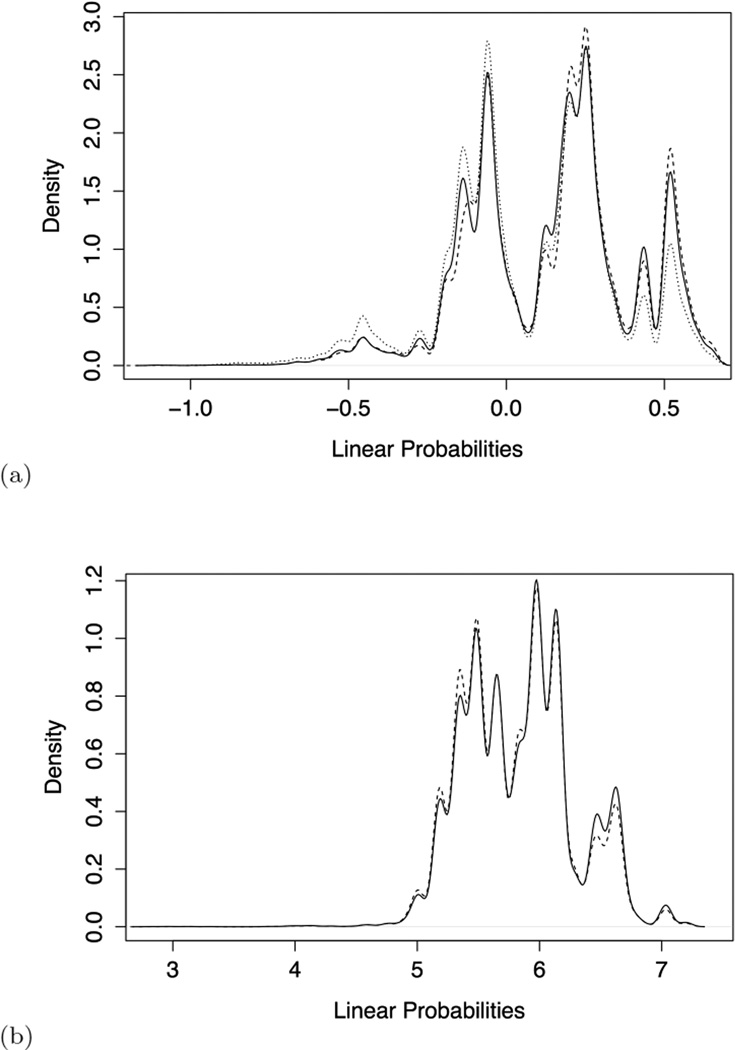

for the pps(W)-based matched MarketScan sample. Both regressions were estimated using weights, with K for MEPS subjects and a weight of 1 assigned to all MarketScan subjects. The linear probability distributions of the propensity scores for ps(W)-based and pps(W)-based samples are displayed in Figure 4. The overlap between the ps(W)-based matched sample and the MEPS Marketplace eligible is tighter than with the MEPS non-Marketplace eligible. However, the Marketplace eligible and non-eligible distributions in MEPS are not well separated, lending evidence that the variables W may not be adequate replacements for C in predicting Marketplace eligibility. The pps(W)-based sample and MEPS Marketplace eligible linear probability distributions are also concordant.

Fig. 4.

Density plots for ps(W) (a) and pps(W) (b) linear probabilities in the matched sample (dashed), MEPS Marketplace eligible (solid), and MEPS non-Marketplace eligible (dotted) [does not appear in plot (b)].

The only imputation procedure we employed that required building regression equations was MICE. This involved first estimating a regression of the A1 (marital status) on W in the MEPS data to estimate predicted probabilities and assign initial binary values to the matched MarketScan sample for the systemically missing variable A1:

A1 = 1 for MEPS subjects who were married and A1 = 0 otherwise (divorced, widowed, separated, etc). This was followed by a regression of A2 (self-reported health status) on W and A1 in the MEPS data to assign initial values to the matched MarketScan sample for A2:

A2 = 1 for MEPS subjects with self-rated health as ‘excellent’ or ‘very good,’ and A2 = 0 for self-rated health categorized as ‘good,’ ‘fair,’ or ‘poor.’ The MICE procedure then continued as described in Section 3.2 by re-estimating these equations in the matched MarketScan samples.

Despite the lesser balance in the ps(W)-based matched MarketScan sample, this selection procedure was superior in terms of the R2 of the risk-adjustment model. The ps(W)-based samples with no imputation and the three different imputation techniques outperformed all of the pps(W)-based samples (Table 4). Of note, the imputation procedures had identical performance compared to the corresponding sample with no imputation, with respect to cross-validated R2. An interesting finding was that the pps(W)-based samples that rely on a “proxy” propensity score are not only less informative than the ps(W)based samples, but also an unmatched sample of equal size drawn from the MarketScan population. The ps(W)-based samples had 9% higher R2 values than the pps(W)-based samples. Of greater importance, however, was that the ps(W)-based sample had only minor improvements compared to an unmatched sample of equal size, with an increased performance of 4%. When examining the imputation variable self-reported health in stratified R2 summaries, we found that the performance in these subgroups did not differ from one another.

Table 4.

Risk-adjustment estimation in MarketScan samples

| Cross-validated R2 | ||

|---|---|---|

| ps(W)-based | pps(W)-based | |

| No imputation | 0.24 | 0.22 |

| Carry-forward | 0.24 | 0.22 |

| Random impute | 0.24 | 0.22 |

| MICE | 0.24 | 0.22 |

| Unmatched | ||

| 0.23 | ||

5 Concluding Remarks

Risk-adjustment formulas used in the new state-level health insurance markets called “Marketplaces,” created under the ACA, were estimated in a sample of people ineligible to participate in the Marketplaces: the Truven MarketScan database of commercial beneficiaries. We implemented matching techniques to create a sample of subjects from the MarketScan databases that reflect the characteristics of the Marketplace-eligible individuals in MEPS (those who, based on their income and insurance status, would qualify for Marketplaces) and then imputed survey values from MEPS into MarketScan. This work involved one level of matching (selecting MarketScan beneficiaries based on Marketplace-eligible MEPS subjects) and a round of imputation procedures in order to estimate risk-adjustment formulas. Researchers in the Netherlands merge survey data with claims data (used for risk adjustment) to check model performance for groups with low health status [32]. Here we conduct the parallel analyses on the basis of imputed self-assessed health status, and this could be performed in other settings as well.

The use of a propensity-score matched sample based on Marketplace eligibility in the MEPS data produced an improved sample for risk adjustment in health insurance Marketplaces, although only a minor improvement in R2. This is an interesting finding in that this project was a first step in a larger initiative to build new metrics for assessing risk adjustment beyond R2 values. This initial study is an important demonstration that use of a single measure like R2 may in fact be masking important differences in the assessment of risk adjustment formulas, particularly among samples with notably disparate distributions. While this may be the case, our results may be a consequence of the variables common between the databases used to develop the propensity score. The ideal set of eligibility variables (i.e., income, insurance, Medicaid eligibility, and employment status) are not present in MarketScan, and we used instead age, sex, metropolitan statistical area, region, and several inpatient healthcare diagnosis codes. Our results may also reflect additional correlation between the cluster of subjects sampled from Marketscan for each MEPS subject.

We also found that the use of a proxy variable for Marketplace eligibility (appearance in the MarketScan or MEPS databases) produced a sample with inferior performance as measured by cross-validated R2 compared to an unmatched sample. Thus, the use of matching for sample selection in similar applications will require careful consideration of the variables available to classify subjects. The introduction of survey imputed values, derived using multiple methods based on information from the MEPS database, yielded no improvement in the performance of our risk adjustment formula, but this result is not definitive. This provides cursory evidence that the inability to include these attributes in risk adjustment in concert with variables currently used for risk adjustment may not be problematic for predicting health care spending. However, this result could have also been due to the restricted set of variables available to impute the survey variables.

Future related statistical work includes the incorporation of machine learning methods for propensity score assignment of the match [9,16] and extension of methods used in the generalizability [3], two-stage sampling [19], and biased sampling [17,18,20,21] literature to the setting of systemic missingness in observational studies. Further work also involves introducing and adapting machine learning methods for use in risk adjustment formulas. Additional projects in risk adjustment revolve around more informative evaluation tools for risk adjustment formulas, as discussed above.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from NIH/NIMH 2R01MH094290.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Sherri Rose, Harvard Medical School, Department of Health Care Policy, 180 Longwood Ave, Boston, MA, 02115, USA, Tel.: +1-617-432-3493, Fax: +1-617-432-0173, rose@hcp.med.harvard.edu.

Julie Shi, Peking University, School of Economics, Haidian District, Beijing, China 100871.

Thomas G. McGuire, Harvard Medical School, Department of Health Care Policy, 180 Longwood Ave, Boston, MA, 02115, USA

Sharon-Lise T. Normand, Harvard Medical School, Department of Health Care Policy, 180 Longwood Ave, Boston, MA, 02115, USA and Harvard School of Public Health, Department of Biostatistics, 655 Huntington Ave, Boston, MA, 02115 USA

References

- 1.Adamson DM, Chang S, Hansen LG. Health research data for the real world: The marketscan databases. New York: Thompson Healthcare; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Austin PC, Mamdani MM. A comparison of propensity score methods: A case study estimating the effectiveness of postami statin use. Statistics in Medicine. 2006;25:2084–2106. doi: 10.1002/sim.2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cole SR, Stuart EA. Generalizing evidence from randomized clinical trials to target populations the actg 320 trial. American journal of epidemiology. 2010;172(1):107–115. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DuGoff E, Schuler M, Stuart E. Generalizing observational study results: applying propensity score methods to complex surveys. Health Services Research. 2014;49(1):284–303. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gelman A, Hill J. Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gu X, Rosenbaum PR. Comparison of multivariate matching methods: Structures, distances, and algorithms. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 1993;2:405–420. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kautter J, Pope GC, Ingber M, Freeman S, Patterson L, Cohen M, Keenan P. The hhs-hcc risk adjustment model for individual and small group markets under the affordable care act. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review. 2014;4(3) doi: 10.5600/mmrr.004.03.a03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King G, Honaker J, Joseph A, Scheve K. American Political Science Association. Vol. 95. Cambridge Univ Press; 2001. Analyzing incomplete political science data: An alternative algorithm for multiple imputation; pp. 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee B, Lessler J, Stuart EA. Improving propensity score weighting using machine learning. Statistics in Medicine. 2009;29:337–346. doi: 10.1002/sim.3782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGuire TG, Newhouse JP, Normand SL, Shi J, Zuvekas S. Assessing incentives for service-level selection in private health insurance exchanges. Journal of Health Economics. 2014;35:47–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meng XL. Multiple-imputation inferences with uncongenial sources of input. Statistical Science. 1994:538–558. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Survey methodology. 2001;27(1):85–96. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rassen JA, Shelat AA, Myers J, Glynn RJ, Rothman KJ, Schneeweiss S. One-to-many propensity score matching in cohort studies. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2012;21(S2):69–80. doi: 10.1002/pds.3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Resche-Rigon M, White IR, Bartlett JW, Peters SA, Thompson SG. Multiple imputation for handling systematically missing confounders in meta-analysis of individual participant data. Statistics in medicine. 2013;32(28):4890–4905. doi: 10.1002/sim.5894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rose S. Mortality risk score prediction in an elderly population using machine learning. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(5):443–452. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose S, van der Laan M. Simple optimal weighting of cases and controls in case-control studies. Int J Biostat. 2008;4(1) doi: 10.2202/1557-4679.1115. Article 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rose S, van der Laan M. Why match? Investigating matched case-control study designs with causal effect estimation. Int J Biostat. 2009;5(1) doi: 10.2202/1557-4679.1127. Article 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose S, van der Laan M. A targeted maximum likelihood estimator for two-stage designs. Int J Biostat. 2011;7(1) doi: 10.2202/1557-4679.1217. Article 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rose S, van der Laan M. A double robust approach to causal effects in case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(6):663–669. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rose S, van der Laan M. Rose and van der laan respond to “Some advantages of RERI”. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(6):672–673. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenbaum PR. Observational Studies. 2 edn. New York: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1984;79:516–524. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The bias due to incomplete matching. Biometrics. 1985:103–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation after 18+ years. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91(434):473–489. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Vol. 81. John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin DB, Schenker N. Multiple imputation in health-are databases: An overview and some applications. Statistics in medicine. 1991;10(4):585–598. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780100410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychological methods. 2002;7(2):147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stuart EA, Azur M, Frangakis C, Leaf P. Multiple imputation with large data sets: a case study of the children’s mental health initiative. American journal of epidemiology. 2009 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp026. kwp026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Laan MJ, Rose S. Targeted learning: causal inference for observational and experimental data. Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Kleef RC, Van Vliet RC, Van de Ven WP. Risk equalization in the netherlands: an empirical evaluation. 2013 doi: 10.1586/14737167.2013.842127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]