Abstract

Abstinence from methamphetamine addiction enhances proliferation and differentiation of neural progenitors and increases adult neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus (DG). We hypothesized that neurogenesis during abstinence contributes to context-driven drug-seeking behaviors. To test this hypothesis, the pharmacogenetic rat model (GFAP-TK rats) was used to conditionally and specifically ablate neurogenesis in the DG. Male GFAP-TK rats were trained to self-administer methamphetamine or sucrose and were administered the antiviral drug valganciclovir (Valcyte) to produce apoptosis of actively dividing GFAP type 1 stem-like cells to inhibit neurogenesis during abstinence. Hippocampus tissue was stained for Ki-67, NeuroD, and DCX to measure levels of neural progenitors and immature neurons, and was stained for synaptoporin to determine alterations in mossy fiber tracts. DG-enriched tissue punches were probed for CaMKII to measure alterations in plasticity-related proteins. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed in acute brain slices from methamphetamine naive (controls) and methamphetamine experienced animals (+/−Valcyte). Spontaneous EPSCs and intrinsic excitability were recorded from granule cell neurons (GCNs). Reinstatement of methamphetamine seeking enhanced autophosphorylation of CaMKII, reduced mossy fiber density, and induced hyperexcitability of GCNs. Inhibition of neurogenesis during abstinence prevented context-driven methamphetamine seeking, and these effects correlated with reduced autophosphorylation of CaMKII, increased mossy fiber density, and reduced the excitability of GCNs. Context-driven sucrose seeking was unaffected. Together, the loss-of-neurogenesis data demonstrate that neurogenesis during abstinence assists with methamphetamine context-driven memory in rats, and that neurogenesis during abstinence is essential for the expression of synaptic proteins and plasticity promoting context-driven drug memory.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Our work uncovers a mechanistic relationship between neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus and drug seeking. We report that the suppression of excessive neurogenesis during abstinence from methamphetamine addiction by a confirmed phamacogenetic approach blocked context-driven methamphetamine reinstatement and prevented maladaptive changes in expression and activation of synaptic proteins and basal synaptic function associated with learning and memory in the dentate gyrus. Our study is the first to demonstrate an interesting and dysfunctional role of adult hippocampal neurogenesis during abstinence to drug-seeking behavior in animals self-administering escalating amounts of methamphetamine. Together, these results support a direct role for the importance of adult neurogenesis during abstinence in compulsive-like drug reinstatement.

Keywords: CaMKII, electrophysiology, methamphetamine, NeuroD, self-administration, synaptoporin

Introduction

The adult dorsal hippocampus is involved in forming context-specific memories associated with relapse to drug seeking (Fuchs et al., 2005; Wells et al., 2016), and the ventral hippocampus is important for reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior triggered by drug context, drug cues, or the drug itself (Rogers and See, 2007; Lasseter et al., 2010; Deschaux et al., 2014). These findings suggest that the neuroadaptive changes in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus contribute to the craving or “preoccupation/anticipation” state that drives reinstatement of drug seeking (Ito et al., 2005; Koob and Volkow, 2010; Schumacher et al., 2016). To add to the existing hippocampal theories on addiction, one recent discovery about the adult hippocampus that is potentially important for addiction research is the ability of the hippocampus to continuously generate new neural progenitor cells throughout adulthood. The discovery (Messier et al., 1958; Messier and Leblond, 1960; Altman, 1962, 1969a,b) and eventual acceptance (Eriksson et al., 1998; Gould et al., 1999; Manganas et al., 2007) of adult-generated progenitors that mature into dentate gyrus (DG) granule cell neurons (GCNs) has spurred substantial investigation of the proliferative capacity of the hippocampus. New emerging correlative data suggest that the phenomena of adult neurogenesis during abstinence from drug use may contribute to some aspects of the reinstatement of drug-seeking behaviors (Eisch et al., 2000; Abrous et al., 2002; Nixon and Crews, 2002; Mandyam et al., 2008; Noonan et al., 2008; Richardson et al., 2009; Recinto et al., 2012). These effects on the reinstatement of drug seeking could be due to the ability of adult neurogenesis to modulate the sparseness of activity of DG GCNs through recruitment of feedback inhibition to affect and strengthen pattern discrimination (Niibori et al., 2012). This pattern discrimination, in the context of spatial memory could enable contextual discrimination and assist with drug seeking triggered by drug context.

Major afferents to the DG are from excitatory perforant path fibers arising from the entorhinal cortex (Andersen et al., 1966a), and electrophysiological studies have demonstrated that activation of the perforant path can initiate excitation of GCNs (Andersen et al., 1966b; Yeckel and Berger, 1990). The synaptic transmission through the DG most importantly function to store, consolidate, and retrieve declarative, spatial, and associative long-term memory (Burgess et al., 2002; Squire et al., 2004). In this context, mechanistic studies from preclinical models show that methamphetamine exposure alters the functional plasticity of hippocampal neurons. Acute and systemic methamphetamine treatment reduces long-term potentiation of CA1 pyramidal neurons through the activation of D1 receptors and increases baseline excitatory synaptic transmission (Swant et al., 2010). Acute methamphetamine exposure reduces the excitability of GCNs, whereas repeated exposure to methamphetamine increases the excitability of GCNs (Criado et al., 2000). These studies demonstrate enhanced neuronal activity in the DG during methamphetamine experience; however, it is yet to be determined whether these alterations in electrophysiological properties of GCNs persist into protracted abstinence from methamphetamine experience.

This led us to hypothesize that proliferation of progenitors and neurogenesis during abstinence plays a role in the propensity for relapse in methamphetamine-addicted animals, and that inhibiting proliferation and neurogenesis during abstinence will reduce the reinstatement of drug seeking. To test the functional role of neurogenesis during abstinence in the reinstatement of drug seeking triggered by drug context, we used GFAP-TK (TK) rats, a pharmacogenetic model for specifically and conditionally inhibiting neurogenesis in adulthood (Snyder et al., 2016). TK rats without Valcyte demonstrated normal and robust methamphetamine self-administration and reinstatement of methamphetamine seeking, comparable to other strains of rats with extended access methamphetamine (Kitamura et al., 2006; Rogers et al., 2008). Our results show that the suppression of active proliferation and the generation of immature neurons in the DG in TK rats during abstinence protects against the propensity for relapse, with reduced context-driven reinstatement. These findings support the direct role of newly born immature neurons in the hippocampus in assisting with maladaptive plasticity in the DG to assist with context-driven drug-seeking behaviors.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Transgenic rats expressing HSV-TK under the human GFAP promoter (GFAP-TK) were generated on a Long–Evans background (Snyder et al., 2016). Sixty-three adult male rats completed the study. These rats were bred at The Scripps Research Institute and VA San Diego Healthcare System. Rats were weaned at 21–24 d of age, pair housed, and genotyped by PCR (TransnetYX). The rats were housed two/cage in a temperature-controlled (22°C) vivarium on a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on 8:00 P.M. to 8:00 A.M.). All procedures were performed during the dark phase of the light/dark cycle. Food and water access was available ad libitum. All rats weighed ∼220–250 g and were 8 weeks old at the beginning of the study. All experimental procedures were performed in strict adherence to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication number 85–23, revised 1996) and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Scripps Research Institute and VA San Diego Healthcare System.

Suppression of neurogenesis.

Neurogenesis was suppressed by feeding the animals the orally available antiviral prodrug valganciclovir (Valcyte, Roche India), which is enzymatically converted to ganciclovir. Valcyte (7.5 mg, p.o.) was given in a 0.5 g pellet of a 1:1 mixture of ground chow and peanut butter. To minimize neophobia, rats were exposed to the chow–peanut butter mixture in their home cage for 2–4 d before drug treatment. On drug treatment days, each rat was separated into an empty cage without bedding and individual Valcyte pellets were placed on the wall of the cage and monitored for feeding activity to ensure consistent dosing. Once the animal consumed the drug pellet, the animal was moved back to the housing chamber. The entire feeding procedure lasted between 4 and 7 min, and care was taken to reduce any stressful experience. Valcyte treatment (1×/d) was initiated during the last week of self-administration and was continued until the day they were killed. All TK animals consumed the chow/peanut butter pellet [with (+) or without (−) Valcyte].

Intravenous catheter surgery and self-administration.

Thirty-six rats underwent surgery for catheter implantation for intravenous methamphetamine self-administration (Galinato et al., 2015). Rats were anesthetized with 2–3% isoflurane mixed in oxygen and implanted with a sterilized silastic catheter [0.64 mm inner diameter (i.d.) × 1.19 mm outer diameter (o.d.); Dow Corning] into the right jugular vein under aseptic conditions. The distal end of the catheter was threaded under the skin to the back of the rat and exited the skin via a metal guide cannula (22 ga, Plastic One). Immediately after surgery, Flunixin (2.5 mg/kg, s.c.; Bimeda—MTC Animal Health) was given as an analgesic. The rats were subjected to antibiotic therapy with Cefoxitin or Cefazolin for 10 d after the surgeries. Catheters were flushed daily with antibiotic in heparinized saline (30 USP units/ml) and tested for patency using methohexital sodium (10 mg/ml, 2 mg/rat; Brevital, King Pharmaceuticals).

Methamphetamine self-administration.

Following 4 d of recovery after surgery, 36 rats were trained to lever press for intravenous infusions of methamphetamine (0.05 mg/kg/injection of methamphetamine hydrochloride, generously provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse) in an operant chamber (context A) on an fixed-ratio 1 (FR1) schedule for 6 h per session for 17 sessions. During daily sessions, a response on the active lever resulted in a 4 second infusion (90–100 μl volume), followed by a 20 second time-out period to prevent overdose. Each infusion was paired for 4 seconds with white stimulus light over the active lever (conditioned stimulus [CS]). Response during the time-out or on the inactive lever was recorded but resulted in no programmed consequences (Galinato et al., 2015). During daily sessions, a response on the active lever resulted in a 4 second infusion (90–100 μl volume), followed by a 20 second time-out period to prevent overdose. Each infusion was paired for 4 seconds with white stimulus light over the active lever (conditioned stimulus [CS]). Response during the time-out or on the inactive lever was recorded but resulted in no programmed consequences (Galinato et al., 2015). Rats were primed for the first hour of the session for the first two sessions. After 17 d of self-administration, rats experienced 22 d of forced abstinence from methamphetamine (a time frame required for newly born progenitors to differentiate and integrate into DG circuitry; Enikolopov et al., 2015). Rats then experienced 6 d of extinction and 2 d of reinstatement. Rats received either Valcyte (TK+Valcyte, n = 17) or vehicle (TK−Valcyte, n = 19) starting on day 13 of self-administration and Valcyte/vehicle treatment was continued daily for 1 week. During the following weeks and until the end of the study, rats were maintained on Valcyte/vehicle twice a week.

Sucrose self-administration.

Fifteen rats were trained to orally self-administer sucrose solution (30 min sessions, 10% sucrose on an FR1 schedule; context A) for 17 sessions. Before sucrose sessions, animals received two training sessions that were conducted overnight in the operant chambers, and active lever presses were rewarded with tap water (100 μl). This allowed us to determine whether the animal learned to (1) press the correct lever for a fluid reward and (2) drink the administered fluid from the delivery/sipper cup. All animals distinguished the active versus the inactive lever and consumed tap water dispensed during the sessions. Following two water sessions, animals lever pressed for sucrose, and these sessions were conducted as 30 min sessions, and 100 μl of 10% sucrose was delivered following an active lever press (similar to methamphetamine sessions, a response on the active lever resulted in a 4 second infusion, followed by a 20 second time-out period. Each infusion was paired for 4 seconds with white stimulus light over the active lever. Response during the time-out or on the inactive lever was recorded but resulted in no programmed consequences). Operant sessions were conducted for a total of 17 sessions. As indicated for methamphetamine rats, sucrose rats received either Valcyte (n = 9) or vehicle (n = 7) starting day 13 of self-administration and drug/vehicle treatment was continued daily for 1 week. During the following weeks and until the end of the study, rats were maintained on Valcyte/vehicle twice a week. Animals remained in their home cages during forced abstinence, which lasted for 22 d, and abstinence was followed by extinction and reinstatement sessions.

Extinction.

Extinction sessions for methamphetamine and sucrose animals were performed in a new context (context B), and each session for methamphetamine animals lasted 1 h and sessions for sucrose animals lasted 30 min. Both groups experienced six extinction sessions. During extinction sessions, animals could respond on two levers in context B located in similar positions compared with the context A where drug self-administration occurred. However, responses on either lever did not result in any programmed consequences (drug, cue light, or drug pump noise). In this context, methamphetamine animals were not attached to the drug infusion apparatus, white noise was added during the entire session, a house light was turned on for the entire session, and black colored tape was pasted on the operant door. Responses on either the active or inactive lever were recorded and did not result in programmed consequences (i.e., no infusions and no conditioned stimulus presentations).

Reinstatement.

Twenty-four hours after the final extinction session, animals underwent context-induced reinstatement in which they were placed into the methamphetamine- or sucrose-paired context (context A) for 1 h or 30 min, during which methamphetamine animals were connected to the infusion apparatus to allow for a similar interaction with the spatial elements of the context as during methamphetamine self-administration training. Sucrose animals were paired with the sucrose context. Lever presses were used as a measure of drug seeking, and responses on either the active or inactive lever were recorded and did not result in an infusion of fluids through the catheter or sipper cup or other programmed consequences (i.e., conditioned stimulus presentations). The next day, animals underwent context-plus-cue-induced reinstatement in which conditions were the same as context-induced reinstatement, and responses on the active lever resulted in the conditioned stimulus light presentation. One hour after the end of the session, animals were killed by rapid decapitation and brain tissue was processed for immunohistochemistry (IHC), Western blotting, or slice electrophysiology.

Brain tissue processing for Western blotting and IHC.

One hour after the reinstatement session, methamphetamine and sucrose-naive control rats (n = 7) and methamphetamine and sucrose rats were killed by rapid decapitation, and the brains were isolated and dissected along the midsagittal plane. The left hemisphere was snap frozen for Western blotting, and the right hemisphere was postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for IHC. For tissue fixation, the hemispheres were incubated at room temperature for 36 h and subsequently at 4°C for 48 h with fresh paraformaldehyde replacing the old solution every 12 h. Finally, the hemispheres were transferred to sucrose solution (30% sucrose with 0.1% sodium azide) for cryoprotection and storage until tissue sectioning was conducted (Cohen et al., 2015). Subsequently, the tissue was sliced in 40 μm sections along the coronal plane on a freezing microtome. Sections were stored in 1× PBS with 0.1% sodium azide at 4°C for histochemical analysis.

IHC.

Every eighteenth section through the hippocampus (anteroposterior, −2.5 to −6.3 mm from bregma) was mounted on Superfrost Plus slides and dried overnight (Somkuwar et al., 2016). Sections were stained for Ki-67 (1:700; rabbit polyclonal, Thermo Fisher Scientific), NeuroD (1:500; goat polyclonal, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) followed by biotin-tagged secondary antibodies and visualized with DAB. The sections were pretreated (Mandyam et al., 2004), blocked, and incubated with the primary antibodies (Ki-67, NeuroD) followed by biotin-tagged secondary antibodies. Immunoreactive cells in the subgranular zone (i.e., cells that touched and were within three cell widths inside and outside the hippocampal granule cell–hilus border for Ki-67 and NeuroD) and cells in the subventricular zone (SVZ; NeuroD) were quantified with a Zeiss AxioImagerA2 (400× magnification) using the optical fractionator method, in which sections through the DG (−1.4 to −6.7 mm from bregma; Paxinos and Watson, 1997) and SVZ (3.70–2.2 mm from bregma) were examined. In addition to cell counting, area measures of the granule cell layer were determined for each section for each animal using StereoInvestigator software (MicroBrightField), and the raw cell counts per section per animal for Ki-67 and NeuroD were divided by the area of the granule cell layer and are indicated as the number of cells per square millimeter of the granule cell layer per animal.

For the density of immature neurons, hippocampal sections through the DG (−1.4 to −6.7 mm from bregma) were separately stained for doublecortin (1:500; goat polyclonal, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) followed by biotin-tagged secondary antibodies and visualized with DAB (Yuan et al., 2011). The images were captured with Zeiss AxioImagerA2 at 10× magnification to incorporate the entire granule cell layer. Grayscale, white-balanced images were captured with StereoInvestigator software (MicroBrightField) and were evaluated by quantifying DAB stain (percentage of the area stained) using ImageJ software [National Institutes of Health (NIH)]. Briefly, the immature neurons were contoured using the polygonal selection feature. A circular area above the granule cell layer was used to quantify nonspecific/background staining.

For morphometric analysis of the density of mossy fiber projections, dorsal hippocampal sections (representing −2.56 and −4.8 mm from bregma, four sections per rat) were separately stained for synaptoporin (1:50; rabbit polyclonal, Synaptic Systems) followed by biotin-tagged secondary antibodies and visualized with DAB (Staples et al., 2017). We chose to use the presynaptic vesicle protein for detecting the density of mossy fiber projections due to the expression of the protein in measurable amounts in the mossy fiber tracts and can be used to quantify mossy fiber sprouting (Römer et al., 2011; Häussler et al., 2016; Schmeiser et al., 2017). For mossy fiber density, images were captured at 10× and the infrapyramidal and suprapyramidal mossy fiber tracts were combined for density measures. Colored, white-balanced images were captured with StereoInvestigator software (MicroBrightField); synaptoporin in the hilus of the dorsal DG and the stratum lucidum (where mossy fibers synapse with hilar and CA3 neurons; CA3 projections) were evaluated by quantifying DAB stain (percentage area stained) using ImageJ software (NIH). Briefly, the mossy fiber tracts were contoured using the polygonal selection feature. A circular area above the CA3 was used to quantify nonspecific/background staining.

For both the immature neuron and mossy fiber density, the images were then converted to red-green-blue stacks. The green stack was used for quantification of DAB using the threshold function; the maximum and minimum thresholds for all the images were set to 130 and 90, respectively. The area stained (percentage area) and the background were measured; specific staining was calculated by subtracting the background (Jensen, 2013).

Western blotting.

Procedures optimized for measuring both phosphoproteins and total proteins were used (Kim et al., 2015). Animals were killed via rapid decapitation under light isoflurane anesthesia 1 h after the end of the reinstatement session. Brains were quickly removed and flash frozen. Tissue punches from dorsal and ventral hippocampal formation enriched in the dentate gyrus from 500-μm-thick sections were homogenized on ice by sonication in buffer (320 mm sucrose, 5 mm HEPES, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm EDTA, 1% SDS, with Protease Inhibitor Cocktail and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktails II and III diluted 1:100; Sigma-Aldrich), heated at 100°C for 5 min, and stored at −80°C until determination of protein concentration by a detergent-compatible Lowry method (Bio-Rad). Samples were mixed (1:1) with a Laemmli sample buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol. Each sample containing protein from one animal was run (20 μg/lane) on 8–12% SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (pore size, 0.2 μm). Blots were blocked with 2.5% bovine serum albumin (for phosphoproteins) or 5% milk (w/v) in TBST [25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20 (v/v)] for 16–20 h at 4°C and were incubated with the following primary antibodies for 16–20 h at 4°C: antibody to total CaMKII (tCaMKII) (1:200; catalog #ab52476, Abcam; predicted molecular weights, 47 and 60 kDa; observed bands, ∼47 and 60 kDa); and antibody to phosphorylated CaMKII (pCaMKII) Tyr-286 (1:200; catalog #ab5683, Abcam; predicted molecular weight, 50 kDa; observed band, ∼50 kDa). Blots were then washed three times for 15 min in TBST and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature (24°C), appropriately with horseradish peroxide-conjugated goat antibody to rabbit or horseradish peroxide-conjugated goat antibody to mouse (1:10,000; Bio-Rad) in TBST. After another three washes for 15 min with TBST, immunoreactivity was detected using SuperSignal West Dura Chemiluminescence Detection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and collected using HyBlot CL Autoradiography film (Denville Scientific) and a Kodak film processor. Following chemiluminescence detection, blots were stripped for 20 min at room temperature (Restore, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and reprobed for total protein levels of β-tubulin (1:4000; catalog #sc-53140, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; predicted molecular weight, 50 kDa; observed band, ∼50 kDa) for normalization purposes. Densitometry was performed using ImageStudio software (Li-Cor Biosciences). X-ray films were digitally scanned at 600 dpi resolution, then bands of interest were selected in identically sized selection boxes within the imaging program, which included a 3 pixel extended rectangle for assessment of the background signal. The average signal of the pixels in the “background” region (between the exterior border of the region of interest selection box and the additional 3 pixel border) was then subtracted from the signal value calculated for the band of interest. This was repeated for β-tubulin, and the signal value of the band of interest following subtraction of the background calculation was then expressed as a ratio of the corresponding β-tubulin signal (following background subtraction). This ratio of expression for each band was then expressed as a percentage of the drug-naive control animals included on the same blot.

Slice preparation.

Slices for electrophysiology were prepared from methamphetamine naive animals (controls; n = 5 rats; n = 11 cells) and +/−Valcyte animals (n = 3 rats each group; n = 8 cells from −Valcyte; n = 23 cells from +Valcyte). Rats from each group were subjected to brief anesthesia (ketamine/xylazine/acepromazine, 62.5/2.6/0.5 mg/kg, i.p.; 0.8 ml/150 g) and perfused for 3 min with ice-cold, oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2), modified sucrose artificial CSF (ACSF) containing the following (in mm): 71 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 3.3 MgSO4 0.5 CaCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 26.2 NaHCO3, 22 glucose, 2.0 thiourea, 72.0 sucrose, 10 choline chloride, 0.5 pyruvate, 0.4 l-ascorbic acid (∼300 mOsm), pH 7.4. The brain was rapidly dissected, and 330-μm-thick slices containing regions of interest were cut on a vibratome (VT1200, Leica). Slices were transferred to an interface chamber containing the same modified sucrose ACSF solution and incubated at 34°C for 30 min. Slices were then held at room temperature (23°C) on the interface chamber for at least 45 min before initiating recordings. Recordings were made in a submersion-type recording chamber and superfused with oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) ACSF containing the following (in mm): 119 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 4.0 MgCl2, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 20 glucose (∼300 mOsm) at 23°C at a rate of 2–3 ml/min.

Electrophysiology.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were obtained using Multiclamp 700B Amplifiers (Molecular Devices), and data were collected using pClamp 10 software (Molecular Devices). Data were low-pass filtered at 2 kHz, and digitized at 10 kHz (Digidata 1440A, Molecular Devices). Voltage-clamp and current-clamp recordings were made at room temperature using glass-pulled patch pipettes (Warner Instruments; o.d., 1.50 mm; i.d., 1.16 mm; length, 10 cm; 4–7 MΩ) filled with internal solution containing the following (in mm): 150 K-Gluconate, 1.5 MgCl2, 5.0 HEPES, 1.0 EGTA, 10 phosphocreatine, 2.0 ATP, and 0.3 GTP. GCNs in the dorsal DG were visualized and then targeted for whole-cell recording under infrared differential interference contrast videomicroscopy (BX-51 scope, Olympus; Rolera XR Digital Camera, Q Imaging). Recordings were made from GCNs located in the middle or the outer third of the granule cell layer (see Fig. 6a). Cells that were impaled were first screened to ensure that they were healthy (stable resting potential). In voltage-clamp experiments, the holding membrane potential was set to −68 mV. Series and input resistances were monitored before and after recordings; data were discarded if they increased by >10 MΩ. In current-clamp experiments, currents were injected stepwise, in 20 pA increments. Step duration was 500 ms. Analysis of electrophysiological properties was made with Clampfit 10.4 software (Molecular Devices) as previously described (Yassin et al., 2010; Benedetti et al., 2013). In brief, resting potential is defined as the recorded membrane potential when the cell membrane was initially broken into with a recording pipette for the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration. Action potential (AP) characteristics are based on a single AP evoked by intracellular current injection (ranging between 60 and 180 pA; 500 ms pulse). Peak amplitude is the actual measured peak AP amplitude in millivolts. Spike threshold is defined as the voltage at which the second derivative of the membrane potential trajectory approaching a spike crossed a user-selected threshold of 20 mV/ms2. The half-width is the period measured in latency (in milliseconds) from the start of the AP to the time when the AP reached half of the peak amplitude.

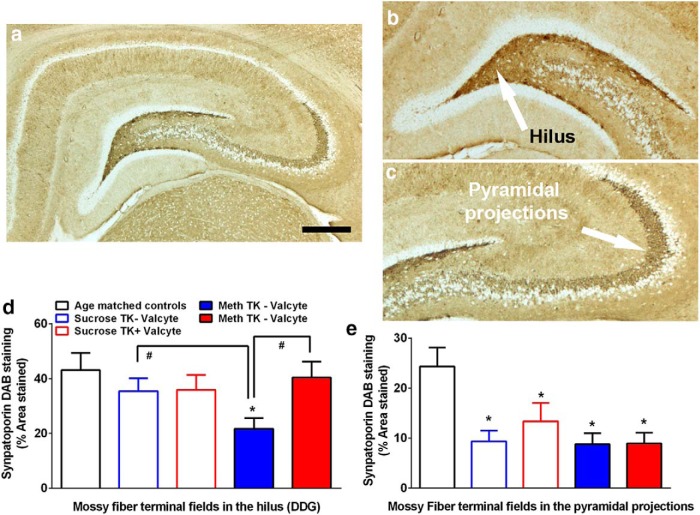

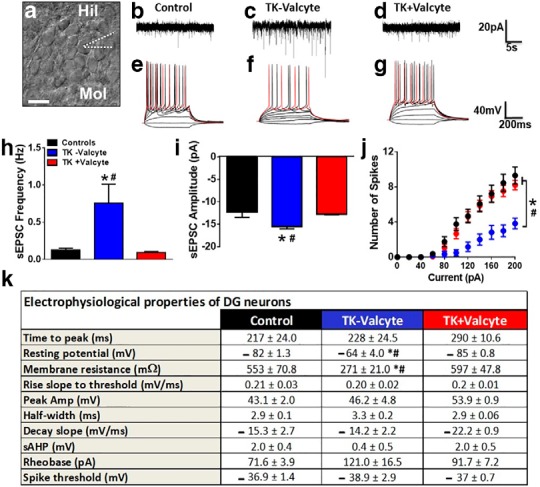

Figure 6.

(a) Representative image of the granule cell layer with GCNs and indication of the patch pipette on a selected neuron. Scale bar is 25µm applies to a. (b-d) Representative spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) traces in voltage-clamp recording from control (b), TK-Valcyte (c) and TK+Valcyte (d) rats. (e-g) Representative traces of action potentials elicited by depolarizing current injections. Traces were recorded from GCNs from control (e; drug and behavior naïve n=2 male GFAP-TK rats and n=2 male Wistar rats; the electrophysiology data between the two strains were not significantly different and therefore were combined), TK-Valcyte (f; n=3 rats) and TK+Valcyte (g; n=2 rats) rats. (h) Frequency of sEPSCs in Hz from neurons. (i) Average of all amplitudes of all sEPSCs above -10pA from GCNs. (j) Graphical relationship between the number of spikes elicited by increasing current injections in current-clamp recording. (k) Electrophysiological properties of GCNs from control, TK-Valcyte and TK+Valcyte rats. Data shown are represented as mean +/- SEM. Number of GCNs, n = 8-13 controls, n = 7-8 TK-Valcyte, n = 15 TK+Valcyte. *p < 0.05 vs. controls and #p < 0.05 vs. TK+Valcyte by ANOVA.

Statistical analyses.

Parametric statistical analysis were used to analyze our datasets based on the assumption that our data fit a normal distribution and satisfy the sample size for adequate statistical power. The methamphetamine self-administration data are expressed as the number of active lever responses per session. The effect of session duration on methamphetamine self-administration during the 6 h session was examined over the 17 escalation sessions using a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (session duration × daily session). Differences in the rate of responding between the first and other escalation sessions were evaluated using the Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test. Similar analyses were performed for sucrose animals. Lever responses during extinction and reinstatement in methamphetamine and sucrose animals was examined using a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (meth group × session) followed by the Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test. For the Ki-67, NeuroD, immature neurons, synaptoporin, Western blotting analyses, and electrophysiology, and one-way or two-way ANOVA was used followed by the Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test. The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM in all graphs.

Results

Extended access to methamphetamine self-administration resulted in escalation of methamphetamine intake

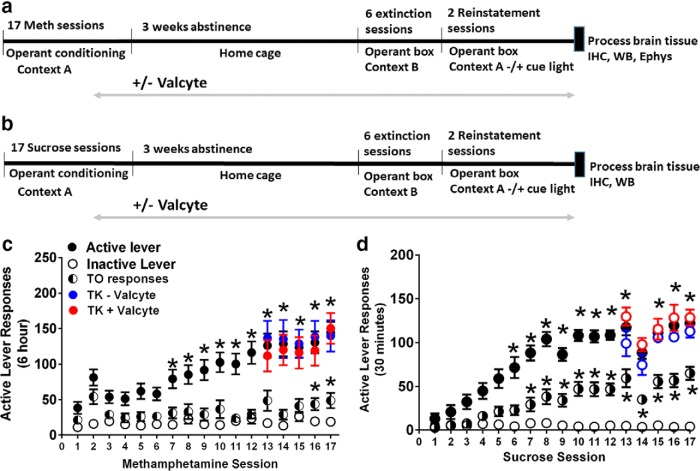

TK rats experienced extended access methamphetamine self-administration sessions for 17 d (Fig. 1a). Repeated-measures ANOVA detected a significant effect of days of self-administration as indicated by increases in the number of active lever responses (F(16,464) = 16.33, p < 0.0001) and an increase in methamphetamine intake across 17 sessions (F(16,464) = 29.5, p < 0.001; Fig. 1c). Post hoc analysis revealed a significant increase in active lever responses and increases in methamphetamine intake during the 6 h session in TK rats during days 7–17 compared with day 1. Active lever responses during timeout increased over the days of self-administration (F(16,464) = 2.31; p = 0.02). Inactive lever responses did not change over days of self-administration (F(16,464) = 0.98; p = 0.52; Fig. 1c). Valcyte treatment did not alter active lever responses in both groups (p > 0.05).

Figure 1.

a, b, Schematic of experimental design indicating the time frame for methamphetamine (Meth; a) and sucrose (b) operant behaviors. Rats either experienced intravenous methamphetamine self-administration (Meth sessions; 6 h/session, 0.05 mg/kg Meth/infusion delivered in 100 μl volume) or oral sucrose self-administration [sucrose sessions; 30 min/session, 10% sucrose solution (w/v), 100 μl solution/infusion]. After 13 sessions rats were initiated on Valcyte diet or vehicle (peanut butter) to ablate or maintain neurogenesis and continued this diet until the end of the experiment. After the last reinstatement session, brain tissue was processed for IHC, Western blotting (WB) and electrophysiology (Ephys). c, d, Escalation of methamphetamine and sucrose taking in GFAP-TK rats: lever responses during 6 h methamphetamine sessions (c) and 30 min sucrose sessions (d). Animals received Valcyte or vehicle on days 13–17, and self-administration behavior did not differ between the two groups in methamphetamine and sucrose animals. n = 19, methamphetamine TK−Valcyte; n = 17 methamphetamine;TK+Valcyte; n = 7 sucrose TK−Valcyte; and n = 9 sucrose TK+Valcyte. Data shown are represented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, compared with session 1 (c, d) by repeated-measures two-way ANOVA and Student–Newman–Keuls post-tests.

Limited access to sucrose self-administration resulted in escalation of sucrose intake

Rats experienced sucrose sessions for 17 d (Fig. 1b). Repeated-measures ANOVA detected a significant increase in the number of active lever responses (F(16,240) = 41.09, p < 0.0001) and an increase in sucrose intake across 17 sessions (F(16,384) = 22.43, p < 0.001; Fig. 1d). Post hoc analysis revealed a significant increase in sucrose intake during the 30 min session in TK rats during days 6–17 compared with day 1. Active lever responses during timeout increased over the days of self-administration (F(16,384) = 21.7; p < 0.0001). Inactive lever responses did not change over the days of self-administration (F(16,384) = 0.96; p = 0.49; Fig. 1d). Valcyte treatment did not alter self-administration behavior in both groups (p > 0.05).

Neurogenesis is necessary for context-driven drug-related memory

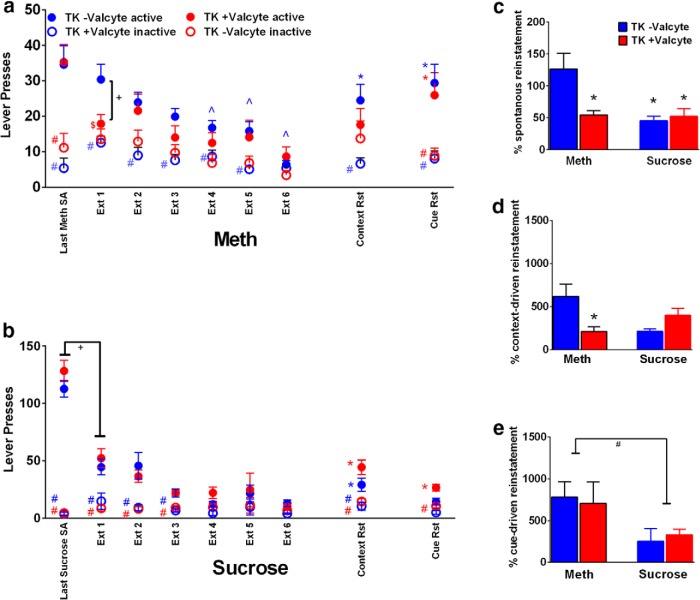

Rats were withdrawn from drug/sucrose, and after a period of protracted abstinence (22 d; a timeframe required for preneuronal progenitor cells to become granule cell neurons; Brown et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2006) all animals were tested for reinstatement of drug seeking in an A-B-A self-administration–extinction–reinstatement paradigm (Shaham et al., 2003). We treated TK rats with Valcyte to inhibit active proliferation and neurogenesis in the DG during abstinence to determine whether neurogenesis during abstinence plays a significant role in context-driven drug-related memory. In TK−Valcyte methamphetamine rats, lever responses during the first extinction session on the previously reinforced active lever were unaltered after an extended period of abstinence compared with the last day of self-administration, and this was evident as higher responses on the previously reinforced active lever compared with nonreinforced inactive lever. Two-way ANOVA detected a Valcyte group × session interaction (F(1,30) = 4.90, p = 0.04); however, no effect of Valcyte group (F(1,30) = 1.09, p = 0.30) indicated a significant effect of session (F(1,30) = 8.51, p = 0.006). Post hoc analysis demonstrated that TK−Valcyte methamphetamine rats had a higher number of lever responses on the first day of extinction compared with TK+Valcyte rats (p < 0.05; Fig. 2a), indicating significant differences in spontaneous reinstatement. Lever responses during the first extinction session on the previously nonreinforced inactive lever was unaltered after an extended period of abstinence compared with the last day of self-administration (no interaction or main effect; Fig. 2a). We next determined whether TK+Valcyte differed in latency to extinguish responses on the previously reinforced active lever compared with TK−Valcyte rats. Repeated-measures two-way ANOVA revealed a significant Valcyte group × days of extinction interaction (F(5,150) = 3.12, p = 0.04) and a significant effect of sessions (F(5,150) = 11.56, p < 0.0001) and did not show a significant effect of group (F(1,30) = 1.18, p = 0.18). Post hoc analysis indicated that TK+Valcyte rats had enhanced latency to extinguish drug-seeking behavior compared with TK−Valcyte rats on the previously reinforced active lever (p < 0.05; Fig. 2a). Responses during extinction sessions gradually declined to the criterion set ≤10 lever presses in TK−Valcyte rats, which was reached during 6 d of training (Fig. 2a; p < 0.05 vs day 1). Lever responses during the extinction sessions on the previously nonreinforced inactive lever were unaltered (no interaction or main effect). All rats were extinguished before reinstatement testing.

Figure 2.

Extinction and reinstatement of drug seeking in GFAP-TK rats. a–b, Active and inactive lever responses during extinction sessions in TK−Valcyte and TK+Valcyte methamphetamine (a) and sucrose (b) animals. Lever responses from the last day of self-administration are indicated for comparison. c–e, The percentage change in active lever responses on day 1 of extinction compared with the last day of self-administration (c), the percentage change in active lever responses on context-driven reinstatement compared with last day of extinction (d), and the percentage change in active lever responses on cue-driven reinstatement compared with last day of extinction (e). Data shown are represented as the mean ± SEM. +p < 0.05 vs TK+Valcyte in a; $p < 0.05 vs. last methamphetamine session in a; #p < 0.05 vs. active lever responses in a, b; *p < 0.05, compared with extinction session 6 (a, b) by repeated-measures two-way ANOVA and Student–Newman–Keuls post-tests. *p < 0.05 vs TK−Valcyte methamphetamine rats in c, d; +p < 0.05 main effect of treatment in b; #p < 0.05 main effect of treatment in e.

All rats were tested for context-driven and cue-induced reinstatement. TK−Valcyte rats showed significant context-driven reinstatement (repeated-measures ANOVA did not show Valcyte group × session interactions (F(1,30) = 2.3, p = 0.13) and did not show a significant effect of group (F(1,30) = 0.39, p = 0.53); however, it showed a significant effect of session (F(1,30) = 16.4, p = 0.003; Fig. 2a). Post hoc analysis indicated that TK−Valcyte rats had higher responses on the previously reinforced active lever during reinstatement compared with extinction sessions (p = 0.002). TK+Valcyte rats did not show context-driven reinstatement. TK−Valcyte and TK+Valcyte rats showed significant contextual cued reinstatement (no Valcyte group × session interaction, no significant effect of group, and a significant effect of session; F(1,30) = 24.6, p < 0.001; Fig. 2a). Post hoc analysis indicated higher responses on the cue-paired active lever compared with extinction session in TK−Valcyte and TK+Valcyte groups (p < 0.01), without any changes in inactive lever responses.

Ablation of neurogenesis during abstinence does not alter context-driven sucrose-related memory

We treated TK rats with Valcyte to inhibit active proliferation and neurogenesis in the DG during abstinence to determine whether neurogenesis during abstinence plays a significant role in context-driven sucrose (non-drug)-related memory. Two-way ANOVA of previously reinforced active lever responses during the first extinction session did not detect a Valcyte group × session interaction or an effect of Valcyte group; however, it indicated a significant effect of session (F(1,14) = 116.7, p < 0.0001; Fig. 2b). Lever responses during the first extinction session on the previously reinforced inactive lever was also altered after an extended period of abstinence compared with the last day of self-administration (no interaction or main effect of group, and a significant main effect of session; F(1,14) = 5.527, p = 0.03; Fig. 2b). Two-way ANOVA did not reveal a significant Valcyte group × days of extinction interaction or a significant effect of group; however, it revealed a significant effect of sessions (F(5,70) = 9.51, p = 0.0001). Responses during extinction sessions gradually declined to the criterion set ≤10 lever presses in TK− and TK+Valcyte sucrose rats, which was reached during 6 d of training (Fig. 2b; p < 0.05 versus day 1). Inactive lever responses were unaltered. All rats were extinguished before reinstatement testing.

TK−Valcyte and TK+Valcyte rats showed significant context-driven reinstatement (repeated-measures two-way ANOVA showed Valcyte group × session interaction; F(1,14) = 6.245, p = 0.02) and did not show a significant effect of group; however, it showed a significant effect of sessions (F(1,14) = 32.60, p = 0.01; Fig. 2b). Post hoc analysis indicated that TK−Valcyte and TK+Valcyte rats had higher responses on the active lever during reinstatement compared with extinction sessions (p < 0.05). TK+Valcyte rats showed significant cue-induced reinstatement (repeated-measures two-way ANOVA showed Valcyte group × session interaction; F(1,14) = 15.17, p < 0.001) and did not show a significant effect of group; however, it showed a significant effect of sessions (F(1,14) = 12.7, p < 0.001; Fig. 2b). Post hoc analysis indicated higher responses on the cue-paired active lever compared with the extinction session in TK+Valcyte rats (p < 0.01). TK−Valcyte rats did not show cue-induced reinstatement. Inactive lever responses were unaltered.

Methamphetamine rats demonstrate higher reinstatement compared with sucrose rats

TK−Valcyte methamphetamine rats demonstrated the highest levels of spontaneous reinstatement [there was a Valcyte × treatment interaction (F(1,44) = 4.19, p = 0.04), and there was no effect of Valcyte; however, there was an effect of treatment (F(1,44) = 4.5, p = 0.03, by two-way ANOVA)]. Post hoc analysis revealed higher reinstatement in TK−Valcyte methamphetamine rats compared with all other groups (p < 0.05; Fig. 2c). There was a significant Valcyte group × treatment interaction when the percentage of context-driven reinstatement was analyzed (F(1,44) = 4.4, p = 0.04), and post hoc analysis revealed higher reinstatement in TK−Valcyte methamphetamine rats compared with TK+Valcyte rats (p = 0.01; Fig. 2d). There was a significant effect of treatment when the percentage of cue-driven reinstatement was analyzed (F(1,44) = 4.1, p = 0.04), and no other measures were significant (Fig. 2e).

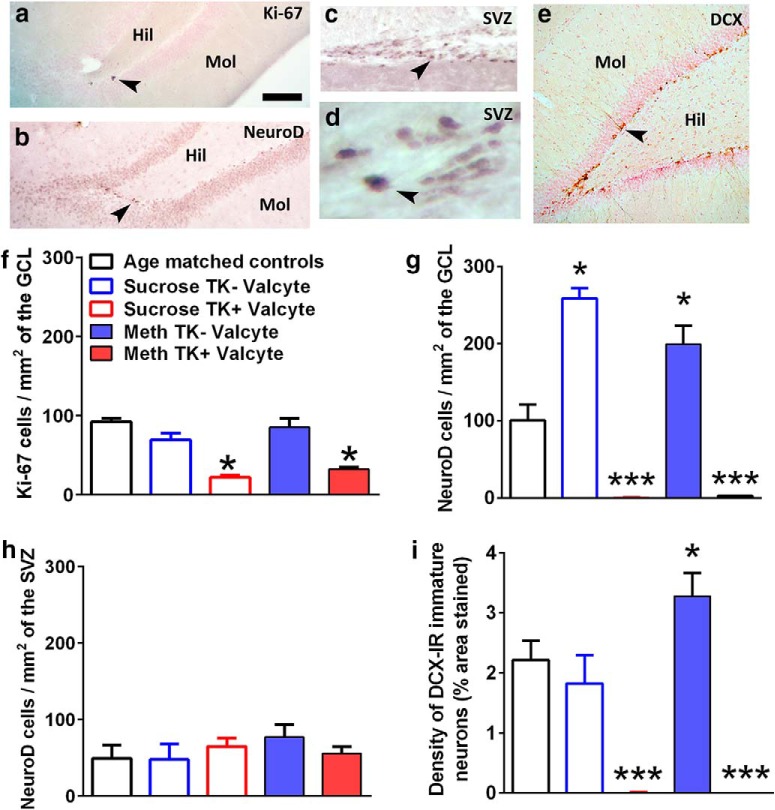

Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that Valcyte treatment completely reduces progenitors and immature neurons and abstinence in sucrose and methamphetamine rats differentially regulate the number of progenitors and immature neurons

IHC with Ki-67, NeuroD, and immature neurons (DCX) was performed to determine the efficacy of Valcyte treatment and the effect of abstinence on progenitors and immature neurons. One-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant effect of Valcyte on the number of Ki-67 cells in the DG (F(4,45) = 12.47, p = 0.002). Post hoc analysis demonstrated a significant decrease in Ki-67 cells in TK+Valcyte rats compared with TK−Valcyte rats and drug-naive controls (p < 0.05; Fig. 3f). One-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant effect of methamphetamine, sucrose, and Valcyte on the number of NeuroD cells in the DG (F(4,45) = 41.9, p = 0.0001). Post hoc analysis demonstrated a significant increase in NeuroD cells in TK−Valcyte methamphetamine and sucrose rats compared with drug-naive controls and a decrease in NeuroD cells in TK+Valcyte rats compared with TK−Valcyte rats and drug-naive controls (p < 0.05; Fig. 3g). Valcyte did not affect the number of NeuroD cells in the SVZ (Fig. 3h). One-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant effect of methamphetamine and Valcyte on the density (percentage of the area stained) of DCX cells in the DG (F(4,45) = 25.02, p < 0.0001). Post hoc analysis demonstrated a significant decrease in DCX cells in TK+Valcyte rats compared with TK−Valcyte rats and drug-naive controls, and an increase in DCX cells in TK−Valcyte methamphetamine rats compared with controls (p < 0.05; Fig. 3i).

Figure 3.

Valcyte reduces proliferation and inhibits neurogenesis in methamphetamine and sucrose rats. a–e, Photomicrographs of labeled cells from control rats: Ki-67 in the DG (a), NeuroD in the DG (b), NeuroD in the SVZ (c, d), and doublecortin in the DG (e). Scale bars: (in a) a–c, e, 100 μm; (in a) d, 20 μm. Arrowheads in a–e point to immunoreactive cells. Hil, Hilus; Mol, molecular layer. f–i, Quantitative analysis of the total number of cells labeled with Ki-67 (f), NeuroD (g, h), and doublecortin (i) in all rats. Drug-naive age-matched controls, n = 6; methamphetamine TK−Valcyte, n = 16; methamphetamine TK+Valcyte, n = 14; sucrose TK−Valcyte, n = 7; sucrose TK+Valcyte, n = 9. Data shown are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 compared with drug-naive controls by one-way ANOVA; ***p < 0.001 vs TK−Valcyte groups and controls by one-way ANOVA.

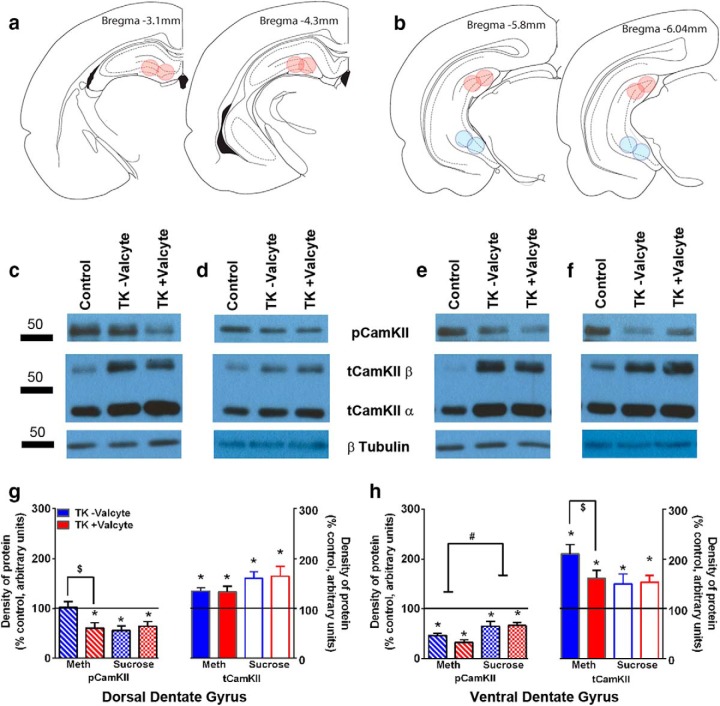

Neurogenesis during abstinence modulates CaMKII activity in the dorsal DG and CaMKII expression in the ventral DG, and these changes regulate context-driven drug-related memory

Immunoblotting with antibodies against plasticity-related proteins was performed to determine whether abstinence from methamphetamine and sucrose affect synaptic proteins that regulate plasticity in the DG and whether neurogenesis during abstinence alters the expression of synaptic proteins in the DG. In the dorsal DG, two-way ANOVA for pCaMKII detected a significant Valcyte × treatment interaction (F(1,39) = 5.201, p < 0.02) and a main effect of treatment (F(1,39) = 3.792, p = 0.05). Post hoc analysis revealed lower expression of pCaMKII in TK−Valcyte methamphetamine rats versus TK+Valcyte methamphetamine rats (p < 0.05; Fig. 4g). Two-way ANOVA for tCaMKII did not detect a significant Valcyte × treatment interaction; however, it detected a main effect of treatment (F(1,41) = 4.720, p = 0.03). In the ventral DG, a split-plot ANOVA for pCaMKII and tCaMKII did not detect a significant Valcyte × treatment interaction; however, it detected a main effect of treatment (pCaMKII: F(1,42) = 19.00, p < 0.01; tCaMKII: F(1,40) = 3.763, p = 0.05; Figure 4h).

Figure 4.

Plasticity-related proteins are affected by methamphetamine seeking, and Valcyte treatment normalizes these effects. a, b, Schematic showing the location of tissue punches taken in the dorsal (a) and ventral (b) DG of the hippocampus. c–f, Representative Western blots for protein expression in dorsal (c, d) and ventral (e, f) DG-enriched tissue of total and phosphorylated CaMKII from methamphetamine (c, e) and sucrose (d, f) rats. g, h, Density of protein expression for total and phosphorylated CaMKII in dorsal (g) and ventral (h) DG from methamphetamine and sucrose rats. *p < 0.05 compared with drug- and sucrose-naive age-matched controls by one-way ANOVA followed by unpaired t tests. $p < 0.05 vs +Valcyte group by two-way ANOVA followed by significant effect of Valcyte. #p < 0.05 vs sucrose group by two-way ANOVA followed by significant effect of treatment. Data shown are represented as the mean ± SEM. Drug-naive age-matched controls, n = 6; methamphetamine TK−Valcyte, n = 13–16; methamphetamine TK+Valcyte, n = 14; sucrose TK−Valcyte, n = 7; sucrose TK+Valcyte, n = 9.

Ablation of neurogenesis during abstinence prevents loss of mossy fiber tracts in the hilus of the dorsal dentate gyrus

IHC with synaptoporin was performed to determine whether abstinence from methamphetamine and sucrose affect mossy fiber density and whether neurogenesis during abstinence alters mossy fiber density. In the hilus, one-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant effect of treatment on the density of synaptoporin F(4,42) = 3.211, p = 0.02). Post hoc analysis demonstrated a significant decrease in synaptoporin density in TK−Valcyte methamphetamine rats compared with drug-naive controls, TK−Valcyte sucrose rats, and TK+Valcyte methamphetamine rats (p values <0.05; Fig. 5d). In the CA3 projections, one-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant effect of treatment on the density of synaptoporin (F(4,41) = 3.193, p = 0.02). Post hoc analysis demonstrated a significant decrease in synaptoporin density in TK−Valcyte and TK+Valcyte sucrose and methamphetamine rats compared with drug-naive controls (p values <0.05; Fig. 5e).

Figure 5.

Methamphetamine seeking alters mossy fiber tracts in the DG and Valcyte normalizes these effects. a–c, Photomicrographs of sections through the anterior dorsal hippocampus stained with synaptoporin. Staining revealed mossy fiber tracts and terminal fields in the hilus (b) and the CA3 pyramidal projections (c). The arrow in b points to the area in the hilus used for density measures, and the arrow in c points to the pyramidal projections used for density measures. Scale bar, a, 500 μm. d, e, Quantitative analysis of the density measures in the hilus (d) and CA3 pyramidal projections (e). Data shown are represented as the mean ± SEM. Drug-naive age-matched controls, n = 6; methamphetamine TK−Valcyte, n = 16; methamphetamine TK+Valcyte, n = 12; sucrose TK−Valcyte, n = 7; sucrose TK+Valcyte, n = 9. *p < 0.05 compared with drug- and sucrose-naive age-matched controls. #p < 0.05 vs respective treatment groups.

Spontaneous neuronal transmission is elevated in TK−Valcyte rats that reinstated methamphetamine seeking compared with drug-naive controls and TK+Valcyte rats

Since we demonstrate reduced mossy fiber density in the hilus and enhanced activity of CaMKII in the DG in TK−Valcyte rats that reinstated methamphetamine seeking, we determined the functional consequences of these alterations in GCNs using whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology. We assessed baseline neuronal transmission using whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings of spontaneous EPSCs (sEPSCs) in the GCNs from control, TK−Valcyte rats, and TK+Valcyte rats (Fig. 6a). GCNs from TK−Valcyte rats had a significantly higher sEPSC frequency and amplitude compared with GCNs from control (frequency: F(2,38) = 15.8, p < 0.0001) and TK+Valcyte rats (frequency: F(2,38) = 6.3, p = 0.004 by one-way ANOVA; Fig. 6b–i). Post hoc analysis demonstrated higher sEPSC frequency in TK−Valcyte rats compared with the other groups (p values <0.01), and higher sEPSC amplitude in TK−Valcyte rats compared with the other groups (p values <0.01).

We next studied the neuronal excitability of GCNs (Fig. 6j,k). GCNs from all groups were able to generate fast action potentials with large amplitudes that were elicited by depolarizing current injections (Fig. 6j). The number of spikes elicited by GCNs from each group with increasing current injections in current-clamp recording were determined, and two-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant number of spike × treatment interaction (F(20,310) = 6.01, p < 0.001), significant increases in the number of spikes over current injections (F(10,310) = 115.1, p < 0.001), and a significant effect of treatment (F(2,31) = 6.0, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis demonstrates that reinstated rats have a reduced number of spikes with increasing current injections compared with all other groups from current injections ranging from 100 to 200 pA (Fig. 6j; p values <0.05). GCNs from TK−Valcyte rats showed depolarized resting potentials compared with controls and TK+Valcyte rats (F(2,30) = 27.85, p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA; Fig. 6k). Post hoc analysis revealed significant differences between TK−Valcyte rats when compared with controls and TK+Valcyte rats (p values <0.01). GCNs from TK−Valcyte rats showed lower membrane resistance compared with other groups (F(2,30) = 10.2, p = 0.004 by one-way ANOVA; Fig. 6k). Post hoc analysis revealed significant decreases in TK−Valcyte rats when compared with controls and TK+Valcyte rats (p values <0.01). Other electrophysiological properties of GCNs were examined, and none of them, including time to peak, rise slope to threshold, peak amplitude, half-width, decay slope, slow afterhyperpolarization, rheobase current, or spike threshold, showed significant differences between groups (Fig. 6k; p = n.s.).

Discussion

The current study determined differences in propensity for relapse in methamphetamine and sucrose rats that demonstrated escalation of drug and sucrose intake and the neuroadaptations in the DG contributing to the behavioral differences. We chose to use the transgenic rat approach over the other types of approaches used for manipulating neurogenesis in adult rats (Tada et al., 2000; Shors et al., 2001; Jessberger et al., 2009); as neurogenesis can be specifically and conditionally inhibited via phamacogenetic strategy during adulthood (Snyder et al., 2016). Methamphetamine rats with intact neurogenesis during abstinence demonstrated significantly greater drug-seeking behavior during extinction and context-driven reinstatement compared with sucrose rats with intact neurogenesis. Inhibition of neurogenesis during abstinence in methamphetamine rats prevented drug-seeking behavior; however, this approach did not affect sucrose-seeking behavior. This indicates that the Valcyte-induced genetic ablation did not generally impair contextual discrimination or alter motivation and motor skills associated with non-drug/reward-seeking behaviors. Together, control over the timing of the ablation specific to abstinence made it possible to explore the role of adult-generated GCNs in the expression of drug-seeking behaviors. Our treatment strategy with Valcyte produced the highest ablation of newly born neurons in the DG, without altering significant numbers of adult-generated cells in the SVZ (Snyder et al., 2016). Moreover, it is unlikely that the deficits in drug seeking that were observed in methamphetamine rats were attributable to a loss of olfactory bulb granule cells, because the current set of experiments did not use odor cues and test for odor-related memories during training and during extinction/reinstatement sessions (Arruda-Carvalho et al., 2014a).

Unregulated, escalated methamphetamine self-administration reduces net proliferation of progenitors and immature neurons in the DG by reducing the number of proliferating preneuronal neuroblasts and increasing the number of proliferating preneuronal progenitor cells (Yuan et al., 2011). These data indicate that the experience of methamphetamine produces a continuous decrease in the number of neural stem cells, which may underlie the psychostimulant-induced decline in hippocampal neurogenesis during the drug experience. However, abstinence from the methamphetamine experience increases the net proliferation of progenitors and the survival of newly born granule cell neurons, suggesting that cell-intrinsic signals that maintain the stem cell pool and cell proliferation are differentially regulated during abstinence from the drug (Recinto et al., 2012). The current findings from GFAP-TK rats support these previous reports that demonstrate enhanced survival of progenitors during abstinence from methamphetamine. The current findings also demonstrate that some of the neurogenic effects are absent during abstinence from sucrose. For example, abstinence increased NeuroD cells and immature neurons in methamphetamine rats, whereas abstinence increased NeuroD cells without increases in immature neurons in sucrose rats. This supports the previous reports that NeuroD cell number is not indicative of net neural differentiation and that DCX expression (one of the targets of NeuroD cells) and cell density represent a later stage of neural differentiation during neurogenesis (Seo et al., 2007; Zheng et al., 2013). These findings suggest that new progenitors generated during the period of forced abstinence from methamphetamine had time to differentiate into immature neurons (Dayer et al., 2003; Mandyam et al., 2008), and immature neurons contributed to some aspects of context-driven methamphetamine seeking and not sucrose seeking (Cameron et al., 1995; Wilkins et al., 2006; Schneider et al., 2008; Galinato et al., 2017). Forced abstinence from methamphetamine lasted for 3 weeks before the extinction sessions began; therefore, it is likely that 3-week-old newly born neurons contributed to spontaneous and context-driven reinstatement. This corresponds to a time point when adult-generated newly born granule cell neurons have synaptically integrated into hippocampal circuitry and display heightened plasticity at input synapses and responsivity to hippocampal-dependent learning and memory (Shors et al., 2001; van Praag et al., 2002; Ming and Song, 2011; Niibori et al., 2012; Akers et al., 2014; Park et al., 2015; Epp et al., 2016). This finding is consistent with other recent studies that have demonstrated a functional role of adult-generated olfactory bulb granule cell neurons in the expression of odor-reward memory via loss-of-function and gain-of-function studies (Alonso et al., 2012; Arruda-Carvalho et al., 2014a). Together, the loss-of-neurogenesis data demonstrate that the ablation of newly generated granule cell neurons erased context-driven drug memory in methamphetamine-addicted rats, and that adult-generated granule cell neurons during abstinence are essential for the expression of context-driven drug memory.

Plasticity in the DG is influenced by plasticity-related proteins, including CaMKII and GluNs (Ni et al., 2009). However, it is not yet established whether alterations in the expression and activation of synaptic plasticity-related proteins in the DG contribute to particular aspects of context-driven drug-related memory. CaMKII is strongly implicated in the induction and maintenance of synaptic strengthening via autonomous activity and increases in autophosphorylation at T286 (Fukunaga et al., 1995; Colbran and Brown, 2004; Lengyel et al., 2004), suggesting that CaMKII activity in the DG could support synaptic plasticity and stability. Our findings demonstrate that the inhibition of neurogenesis during abstinence reduced autophosphorylation of CaMKII at T286 in the dorsal DG and reduced the expression of CaMKII in the ventral DG. A potential limitation in the interpretation of these results is that CaMKII expression and activation could be regulated as a function of the neurogenesis of progenitor cells born during acute withdrawal. Although beyond the scope of the current study, it would be critical to investigate of the role of CaMKII in adult-born neurons in context-driven drug seeking (Arruda-Carvalho et al., 2014b). Additional consideration should be given to evaluating the changes in protein expression at various time points during abstinence that correlate with distinct stages of neurogenesis (Dayer et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2006). Nevertheless, these results suggest that one consequence of perturbing neurogenesis during abstinence is impaired CaMKII activity and expression, and this alteration could alter other forms of plasticity in the DG to reduce context-driven drug memories.

In the DG, newly born GCNs contribute to the density of mossy fiber tracts (Römer et al., 2011). Given the inverse correlation between mossy fiber density and CaMKII expression in the DG (Ni et al., 2009), we determined the density of mossy fiber projections in methamphetamine and sucrose rats. Our findings demonstrate that in the hilus, in animals that demonstrated context-driven methamphetamine seeking, mossy fiber density was significantly reduced, and that this correlated with the enhanced activity of CaMKII, and this relationship has been previously shown to support enhanced learning and memory behaviors (Crusio and Schwegler, 1987; Crusio et al., 1987; Ni et al., 2009). Ablating newly born neurons during abstinence prevented these changes and reduced context-driven drug seeking. In the pyramidal projections, we observed that mossy fiber tracts were reduced in all treatment groups that experienced context-driven seeking behavior, supporting the fact that hippocampal load was enhanced and that all animals (methamphetamine and sucrose) that learned to perform operant behavior should be compared with drug/behavior-naive animals (Lipp et al., 1984, 1988).

We next characterized the alterations in the basal neuronal function of GCNs as it is influenced by the activity of CaMKII (Liao et al., 2001; Rakhade et al., 2008). The electrophysiological results indicate that GCNs from TK−Valcyte rats with intact neurogenesis during abstinence have dysregulated neuronal functioning in the basal state. GCNs from TK−Valcyte rats have an increased level of spontaneous glutamatergic activity compared with controls and TK+Valcyte rats, with enhanced frequency and amplitude of sEPSCs. Generally, changes in the frequency of EPSCs reflect changes in the probability of glutamate release, while changes in EPSC amplitude and kinetics reflect a change in postsynaptic glutamatergic receptor function (De Koninck and Mody, 1994). Therefore, the enhanced basal function of GCNs evident as hyperexcitability of neurons in TK−Valcyte rats suggests that activated CaMKII signaling can upregulate glutamatergic synaptic transmission and assist with molecular memory to support context-driven drug seeking (Shen et al., 2000; Liao et al., 2001; Wang and Kelly, 2001). GCNs from TK−Valcyte rats also demonstrated altered active and passive membrane properties, visualized as reduced action potential generation with an increased number of depolarizing current injections compared with neurons from controls and TK+Valcyte rats. One contributing factor is that GCNs in TK−Valcyte rats have lower membrane properties that favor decreased action potential generation with similar current stimuli compared with naive controls, and these effects could be facilitated by altered calcium signaling and loss of or less functional glutamate receptors (Spruston et al., 1995; Cammarota et al., 2002).

In sum, the pharmacogenetic approach we used allowed for efficient deletion of newly born granule cell neurons in the entire DG, suggesting that a relatively small proportion of neurons is sufficient to induce CaMKII expression in concert with plasticity and to promote hippocampus-dependent context-driven drug seeking. The integration of newly born neurons into the DG circuitry is a fine-tuned process; therefore, it is possible that even small perturbations of this process can impact DG-dependent activity and function (Aimone et al., 2014; Kempermann et al., 2015). It is likely that the inhibition of neurogenesis during abstinence not only compromises, but also impairs the plasticity of preexisting granule cell neurons (Lacefield et al., 2012). Therefore, an alternative (but not necessarily mutually exclusive) possibility is that reduced context-driven drug seeking is related to the reduced potential for the strengthening of synaptic inputs during abstinence to promote the propensity for relapse.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (DGE-1144086 to M.H.G.), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA-034140 to C.D.M. and minority supplement DA-034140-S to M.H.G.), and the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (AA-020098 and AA-06420 to C.D.M.); and by startup funds from the Veterans Medical Research Foundation (C.D.M.). We thank Dr. Heather Cameron and Michelle Brewer from the National Institutes of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health (NIH) for providing the GFAP-TK rats. We also thank Alekhya Bommireddipalli, Vionna Wong, Atoosa Ghofranian, Leyda Villagrasa, and Jacque Quigley from the independent study program at University of California San Diego, the Summer Undergraduate Research Fellows program at The Scripps Research Institute, and the Summer Research program from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH, for excellent technical assistance with tissue processing and IHC. In addition, we thank Lani Francis from The Scripps Research Institute vivarium for her assistance with breeding and genotyping GFAP-TK rats.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Abrous DN, Adriani W, Montaron MF, Aurousseau C, Rougon G, Le Moal M, Piazza PV (2002) Nicotine self-administration impairs hippocampal plasticity. J Neurosci 22:3656–3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aimone JB, Li Y, Lee SW, Clemenson GD, Deng W, Gage FH (2014) Regulation and function of adult neurogenesis: from genes to cognition. Physiol Rev 94:991–1026. 10.1152/physrev.00004.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akers KG, Martinez-Canabal A, Restivo L, Yiu AP, De Cristofaro A, Hsiang HL, Wheeler AL, Guskjolen A, Niibori Y, Shoji H, Ohira K, Richards BA, Miyakawa T, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW (2014) Hippocampal neurogenesis regulates forgetting during adulthood and infancy. Science 344:598–602. 10.1126/science.1248903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso M, Lepousez G, Sebastien W, Bardy C, Gabellec MM, Torquet N, Lledo PM (2012) Activation of adult-born neurons facilitates learning and memory. Nat Neurosci 15:897–904. 10.1038/nn.3108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J. (1962) Are new neurons formed in the brains of adult mammals? Science 135:1127–1128. 10.1126/science.135.3509.1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J. (1969a) Autoradiographic and histological studies of postnatal neurogenesis. 3. Dating the time of production and onset of differentiation of cerebellar microneurons in rats. J Comp Neurol 136:269–293. 10.1002/cne.901360303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J. (1969b) Autoradiographic and histological studies of postnatal neurogenesis. IV. Cell proliferation and migration in the anterior forebrain, with special reference to persisting neurogenesis in the olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol 137:433–457. 10.1002/cne.901370404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen P, Holmqvist B, Voorhoeve PE (1966a) Entorhinal activation of dentate granule cells. Acta Physiol Scand 66:448–460. 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1966.tb03223.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen P, Holmqvist B, Voorhoeve PE (1966b) Excitatory synapses on hippocampal apical dendrites activated by entorhinal stimulation. Acta Physiol Scand 66:461–472. 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1966.tb03224.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruda-Carvalho M, Akers KG, Guskjolen A, Sakaguchi M, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW (2014a) Posttraining ablation of adult-generated olfactory granule cells degrades odor-reward memories. J Neurosci 34:15793–15803. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2336-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruda-Carvalho M, Restivo L, Guskjolen A, Epp JR, Elgersma Y, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW (2014b) Conditional deletion of α-CaMKII impairs integration of adult-generated granule cells into dentate gyrus circuits and hippocampus-dependent learning. J Neurosci 34:11919–11928. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0652-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti BL, Takashima Y, Wen JA, Urban-Ciecko J, Barth AL (2013) Differential wiring of layer 2/3 neurons drives sparse and reliable firing during neocortical development. Cereb Cortex 23:2690–2699. 10.1093/cercor/bhs257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JP, Couillard-Després S, Cooper-Kuhn CM, Winkler J, Aigner L, Kuhn HG (2003) Transient expression of doublecortin during adult neurogenesis. J Comp Neurol 467:1–10. 10.1002/cne.10874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess N, Maguire EA, O'Keefe J (2002) The human hippocampus and spatial and episodic memory. Neuron 35:625–641. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00830-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, McEwen BS, Gould E (1995) Regulation of adult neurogenesis by excitatory input and NMDA receptor activation in the dentate gyrus. J Neurosci 15:4687–4692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota M, Bevilaqua LR, Viola H, Kerr DS, Reichmann B, Teixeira V, Bulla M, Izquierdo I, Medina JH (2002) Participation of CaMKII in neuronal plasticity and memory formation. Cell Mol Neurobiol 22:259–267. 10.1023/A:1020763716886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A, Soleiman MT, Talia R, Koob GF, George O, Mandyam CD (2015) Extended access nicotine self-administration with periodic deprivation increases immature neurons in the hippocampus. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 232:453–463. 10.1007/s00213-014-3685-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbran RJ, Brown AM (2004) Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and synaptic plasticity. Curr Opin Neurobiol 14:318–327. 10.1016/j.conb.2004.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criado JR, Gombart LM, Huitrón-Reséndiz S, Henriksen SJ (2000) Neuroadaptations in dentate gyrus function following repeated methamphetamine administration. Synapse 37:163–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crusio WE, Schwegler H (1987) Hippocampal mossy fiber distribution covaries with open-field habituation in the mouse. Behav Brain Res 26:153–158. 10.1016/0166-4328(87)90163-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crusio WE, Schwegler H, Lipp HP (1987) Radial-maze performance and structural variation of the hippocampus in mice: a correlation with mossy fibre distribution. Brain Res 425:182–185. 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90498-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayer AG, Ford AA, Cleaver KM, Yassaee M, Cameron HA (2003) Short-term and long-term survival of new neurons in the rat dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol 460:563–572. 10.1002/cne.10675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Koninck Y, Mody I (1994) Noise analysis of miniature IPSCs in adult rat brain slices: properties and modulation of synaptic GABAA receptor channels. J Neurophysiol 71:1318–1335. 10.1152/jn.1994.71.4.1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschaux O, Vendruscolo LF, Schlosburg JE, Diaz-Aguilar L, Yuan CJ, Sobieraj JC, George O, Koob GF, Mandyam CD (2014) Hippocampal neurogenesis protects against cocaine-primed relapse. Addict Biol 19:562–574. 10.1111/adb.12019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisch AJ, Barrot M, Schad CA, Self DW, Nestler EJ (2000) Opiates inhibit neurogenesis in the adult rat hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:7579–7584. 10.1073/pnas.120552597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enikolopov G, Overstreet-Wadiche L, Ge S (2015) Viral and transgenic reporters and genetic analysis of adult neurogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7:a018804. 10.1101/cshperspect.a018804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epp JR, Silva Mera R, Köhler S, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW (2016) Neurogenesis-mediated forgetting minimizes proactive interference. Nat Commun 7:10838. 10.1038/ncomms10838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, Alborn AM, Nordborg C, Peterson DA, Gage FH (1998) Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med 4:1313–1317. 10.1038/3305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Evans KA, Ledford CC, Parker MP, Case JM, Mehta RH, See RE (2005) The role of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, basolateral amygdala, and dorsal hippocampus in contextual reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 30:296–309. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga K, Muller D, Miyamoto E (1995) Increased phosphorylation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and its endogenous substrates in the induction of long-term potentiation. J Biol Chem 270:6119–6124. 10.1074/jbc.270.11.6119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinato MH, Orio L, Mandyam CD (2015) Methamphetamine differentially affects BDNF and cell death factors in anatomically defined regions of the hippocampus. Neuroscience 286:97–108. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.11.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinato MH, Lockner JW, Fannon-Pavlich MJ, Sobieraj JC, Staples MC, Somkuwar SS, Ghofranian A, Chaing S, Navarro AI, Joea A, Luikart BW, Janda KD, Heyser C, Koob GF, Mandyam CD (2017) A synthetic small-molecule Isoxazole-9 protects against methamphetamine relapse. Mol Psychiatry. Advance online publication. Retrieved January 23, 2018. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.46. 10.1038/mp.2017.46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Reeves AJ, Fallah M, Tanapat P, Gross CG, Fuchs E (1999) Hippocampal neurogenesis in adult old world primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:5263–5267. 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häussler U, Rinas K, Kilias A, Egert U, Haas CA (2016) Mossy fiber sprouting and pyramidal cell dispersion in the hippocampal CA2 region in a mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Hippocampus 26:577–588. 10.1002/hipo.22543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito R, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW (2005) The hippocampus and appetitive pavlovian conditioning: effects of excitotoxic hippocampal lesions on conditioned locomotor activity and autoshaping. Hippocampus 15:713–721. 10.1002/hipo.20094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen EC. (2013) Quantitative analysis of histological staining and fluorescence using ImageJ. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 296:378–381. 10.1002/ar.22641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessberger S, Clark RE, Broadbent NJ, Clemenson GD Jr, Consiglio A, Lie DC, Squire LR, Gage FH (2009) Dentate gyrus-specific knockdown of adult neurogenesis impairs spatial and object recognition memory in adult rats. Learn Mem 16:147–154. 10.1101/lm.1172609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G, Song H, Gage FH (2015) Neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7:a018812. 10.1101/cshperspect.a018812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim A, Zamora-Martinez ER, Edwards S, Mandyam CD (2015) Structural reorganization of pyramidal neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex of alcohol dependent rats is associated with altered glial plasticity. Brain Struct Funct 220:1705–1720. 10.1007/s00429-014-0755-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura O, Wee S, Specio SE, Koob GF, Pulvirenti L (2006) Escalation of methamphetamine self-administration in rats: a dose-effect function. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 186:48–53. 10.1007/s00213-006-0353-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Volkow ND (2010) Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 35:217–238. 10.1038/npp.2009.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacefield CO, Itskov V, Reardon T, Hen R, Gordon JA (2012) Effects of adult-generated granule cells on coordinated network activity in the dentate gyrus. Hippocampus 22:106–116. 10.1002/hipo.20860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasseter HC, Xie X, Ramirez DR, Fuchs RA (2010) Sub-region specific contribution of the ventral hippocampus to drug context-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Neuroscience 171:830–839. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.09.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengyel I, Voss K, Cammarota M, Bradshaw K, Brent V, Murphy KP, Giese KP, Rostas JA, Bliss TV (2004) Autonomous activity of CaMKII is only transiently increased following the induction of long-term potentiation in the rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci 20:3063–3072. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Scannevin RH, Huganir R (2001) Activation of silent synapses by rapid activity-dependent synaptic recruitment of AMPA receptors. J Neurosci 21:6008–6017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp HP, Schwegler H, Driscoll P (1984) Postnatal modification of hippocampal circuitry alters avoidance learning in adult rats. Science 225:80–82. 10.1126/science.6729469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp HP, Schwegler H, Heimrich B, Driscoll P (1988) Infrapyramidal mossy fibers and two-way avoidance learning: developmental modification of hippocampal circuitry and adult behavior of rats and mice. J Neurosci 8:1905–1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandyam CD, Norris RD, Eisch AJ (2004) Chronic morphine induces premature mitosis of proliferating cells in the adult mouse subgranular zone. J Neurosci Res 76:783–794. 10.1002/jnr.20090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandyam CD, Wee S, Crawford EF, Eisch AJ, Richardson HN, Koob GF (2008) Varied access to intravenous methamphetamine self-administration differentially alters adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Biol Psychiatry 64:958–965. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manganas LN, Zhang X, Li Y, Hazel RD, Smith SD, Wagshul ME, Henn F, Benveniste H, Djuric PM, Enikolopov G, Maletic-Savatic M (2007) Magnetic resonance spectroscopy identifies neural progenitor cells in the live human brain. Science 318:980–985. 10.1126/science.1147851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messier B, Leblond CP (1960) Cell proliferation and migration as revealed by radioautography after injection of thymidine-H3 into male rats and mice. Am J Anat 106:247–285. 10.1002/aja.1001060305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messier B, Leblond CP, Smart IH (1958) Presence of DNA synthesis and mitosis in the brain of young adult mice. Exp Cell Res 14:224–226. 10.1016/0014-4827(58)90235-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming GL, Song H (2011) Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions. Neuron 70:687–702. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni H, Jiang YW, Tao LY, Cen JN, Wu XR (2009) Effects of penicillin-induced developmental epilepticus on hippocampal regenerative sprouting, related gene expression and cognitive deficits in rats. Toxicol Lett 188:161–166. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niibori Y, Yu TS, Epp JR, Akers KG, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW (2012) Suppression of adult neurogenesis impairs population coding of similar contexts in hippocampal CA3 region. Nat Commun 3:1253. 10.1038/ncomms2261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon K, Crews FT (2002) Binge ethanol exposure decreases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J Neurochem 83:1087–1093. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01214.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan MA, Choi KH, Self DW, Eisch AJ (2008) Withdrawal from cocaine self-administration normalizes deficits in proliferation and enhances maturity of adult-generated hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci 28:2516–2526. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4661-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EH, Burghardt NS, Dvorak D, Hen R, Fenton AA (2015) Experience-dependent regulation of dentate gyrus excitability by adult-born granule cells. J Neurosci 35:11656–11666. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0885-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C (1997) The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates, Ed 3 San Diego: Academic. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakhade SN, Zhou C, Aujla PK, Fishman R, Sucher NJ, Jensen FE (2008) Early alterations of AMPA receptors mediate synaptic potentiation induced by neonatal seizures. J Neurosci 28:7979–7990. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1734-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]