Abstract

The rapidly growing set of GenBank submissions includes sequences that are derived from vouchered specimens. These are associated with culture collections, museums, herbaria and other natural history collections, both living and preserved. Correct identification of the specimens studied, along with a method to associate the sample with its institution, is critical to the outcome of related studies and analyses. The National Center for Biotechnology Information BioCollections Database was established to allow the association of specimen vouchers and related sequence records to their home institutions. This process also allows cross-linking from the home institution for quick identification of all records originating from each collection.

Database URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/biocollections

Introduction

The BioCollections Database is a curated dataset of metadata for culture collections, museums, herbaria and other natural history collections connected to sequence records in GenBank. It is maintained and curated by the Taxonomy group at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Biocollection institution codes are unique across multiple types of collections and the database is used to support the ‘structured voucher’ annotation in the sequence entries submitted to International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (INSDC) (1). This broadly follows the Darwin Core (DwC) standard for biodiversity data (2) and is used to standardize usage across interconnected databases including GenBank the NCBI (3), as well as the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) (4) and DNA Databank of Japan (DDBJ) (5).

Initially, the data were imported from Index Herbariorum (6), World Federation for Culture Collections (http://www.wfcc.info/), Insect and Spider Collections of the World (http://hbs.bishopmuseum.org/codens/codens-r-us.html), Amphibian Species of the World (AMNH) (7) and the Catalog of Fishes (8). Only the institution codes that are listed in the BioCollections Database appear as ‘structured voucher’ in GenBank records. New repository records are added to the database as they are submitted to INSDC along with sequence data. Since the BioCollections Database is maintained at NCBI, the validation process is fast. Prior to inclusion in BioCollections, the new collections are validated to ensure that they are curated, are readily available to the public and there is a contact person responsible for the collections. If a home institution has a catalogue page and provides us with URL formula, the vouchers in the sequence entries are hot-linked to specimen pages at the relevant collection (Figure 1). Personal collections are not normally included. Other directories of repositories are periodically reviewed to ensure that the NCBI BioCollections is up-to-date.

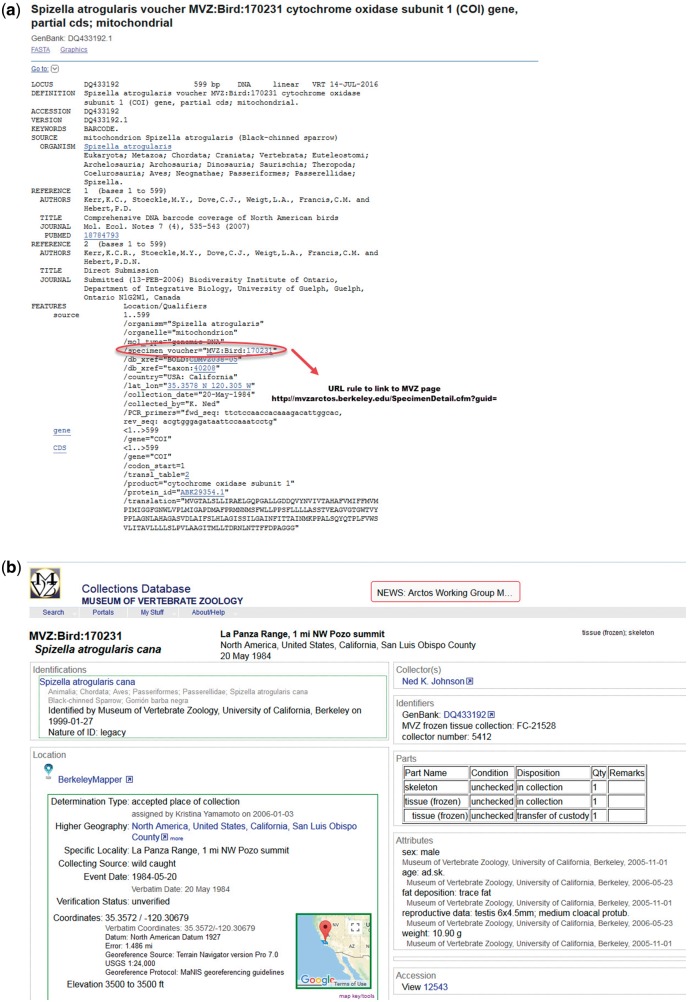

Figure 1.

Example of structured voucher annotation. (a) GenBank flat file record for Spizella atrogularis, accession DQ433192 and URL formula to map the record to MVZ specimen page. (b) Specimen page at Museum of Vertebrae Zoology, University of California, Berkeley for Spizella atrogularis linked to GenBank record DQ431992.

As the importance of specimen vouchers in biodiversity studies continues to grow, it is increasingly important to organize and annotate the data to allow users to easily access this information and confirm which collection houses the original sample. This newly released public resource is the source for building links between NCBI databases and external collections.

BioCollections Database overview

In 2005, the Consortium for the Barcode of Life (CBOL; http://www.barcodeoflife.org) proposed linking sequence records to voucher specimens as part of the DNA Barcode data standard. This method was developed in collaboration with the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (http://www.gbif.org/) and other major biodiversity database initiatives. The NCBI BioCollections Database was created as a part of this global project to gather, update, manage and search biological collections information. In mid-2008, members of INSDC started annotating sequence entries that contained culture collection or specimen voucher information with structured voucher qualifiers.

The initial method proposed for linkage by CBOL used a structured data format based on the DwC data standards developed by the Biodiversity Information Standards (TDWG, formerly the Taxonomic Database Working Group). The DwC standard Triplet format for specimen data consists of three parts: the universally-recognized code for the institution that holds the voucher specimen; the institution’s code for the collection in which the voucher specimen is kept and the unique specimen identifier, all separated by colons.

For example:

/organism=‘Spizella atrogularis’

/specimen_voucher=‘MVZ: Bird: 170231’

In many cases, a secondary collection code (such as a collection devoted to mammals or plants at a specific institution) is not utilized and in such cases the specimen data is indicated as a doublet only.

/organism=‘Enterococcus flavescens’

/culture_collection=‘ATCC: 49996’

This structured data field for voucher specimens was approved by the members of the INSDC in May 2005.

Structured Voucher Annotation:

There are three different types of qualifiers for annotating sequences from different source materials:

/culture_collection for live microbial and viral cultures and cell lines deposited in curated culture collections.

/specimen_voucher for a physical specimen in a curated museum, herbarium, frozen tissue collection or in laboratory (accessible to public). If the specimen was destroyed in the process of sequencing, electronic images (e-vouchers) are an adequate substitute for a specimen voucher.

/bio_material for source material in biological collections that do not fit into either the/specimen_voucher or the/culture_collection modifier categories, like physical specimens from zoos, aquaria, stock centers, germplasm repositories and DNA banks.

Another set of qualifiers may contain information from BioCollections. Submitters commonly use these fields to add voucher information but they are not ‘structured,’ hence, they don’t get linked to Biocollections Database.

/isolate is recommended to identify specific individuals or samples from which the sequence data was originally obtained––this can include field numbers and a broad set of unique identifiers that will not be classified under strain or culture collection.

/strain is recommended for cultures in personal collection or laboratory.

/note for any comment or additional information about the organism.

Until recently, the BioCollections Database was only used internally by the members of INSDC, mainly to facilitate sequence annotation, although a public text-based data file was (and remains) available (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/pub/taxonomy/Cowner_dump.txt). Over the years, the database has grown significantly. Each record now provides information about the institution that houses the collection, standard institution code, mailing address and associated webpage if available. If there are collections within an institution, they are listed within the institution record as collection codes. As of October 2017, there are over 7400 institution codes and ∼300 collection codes listed in the BioCollections Database. Recognizing that this information can be useful to a broader scientific community, NCBI released this resource to the public in April of 2017.

Search and retrieve data

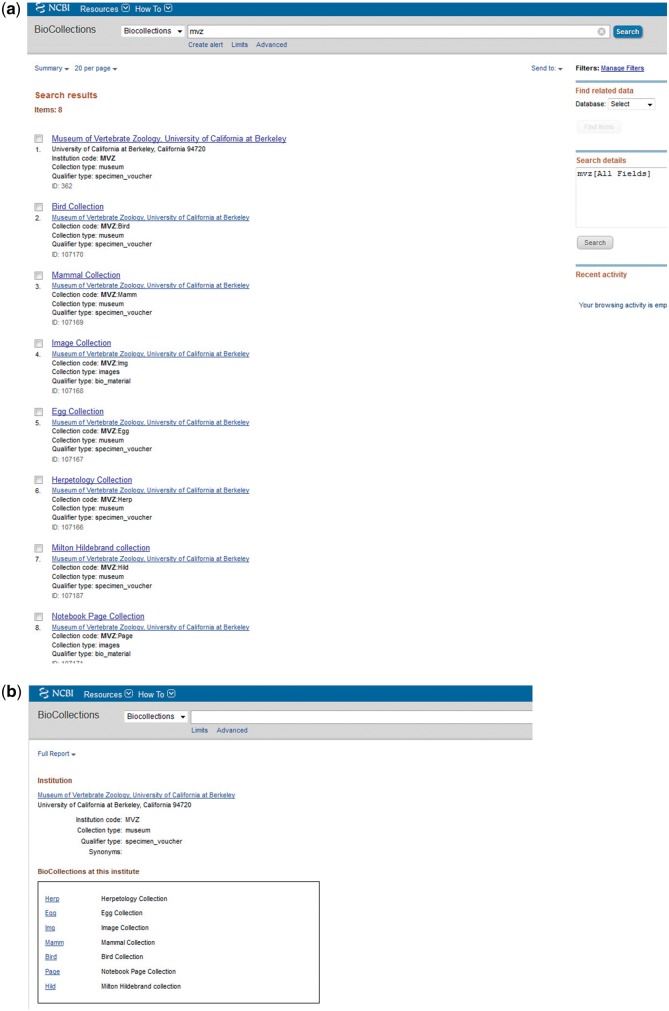

Various search queries can be used to search the BioCollections Database using the search box on the BioCollections homepage. For example, searching with MVZ will bring up Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California at Berkeley and its collections (Figure 2). Some useful search fields are listed in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of BioCollections search page. (a) Showing result for institution code MVZ. (b) Biocollections Database entry for MVZ.

Table 1.

Selected search field and queries

| Query | Find by |

|---|---|

| Search by code | Institution codes or collection codes or combination |

|

Retrieves all the entries that have UAM as institution code including the ones that are unique |

|

Retrieves only the exact match |

| UAM = University of Alaska, Museum of the North | |

|

Retrieves all the institution entries that list mamm as collections |

|

Retrieves all the entries that list UAM as institution code/collection code and synonyms |

| Search by name | Partial or full institution or collection name |

|

Retrieves all the entries that have Alaska in the institution name |

|

Retrieves all the entries that have mammal in collection name |

|

Retrieves all entries that have Alaska in institution/collection name |

| Search by properties | Modifier type |

| Collection type museum[prop] | Retrieves all museum entries |

| Collection type herbarium[prop] | Retrieves all herbarium entries |

| Collection type culture collection[prop] | Retrieves all culture collection entries |

Complex queries can be built by specifying the search terms, their fields and the Boolean operations AND, OR and NOT.

The BioCollections Database is reciprocally linked to other databases like Nucleotide, Protein, Popset, EST and GSS. This allows users to find all related records that are from an institution of interest.

Users can download the BioCollections dataset by using ‘Send To’ -> ‘File’ option, located at the upper right corner of the search results page. Summary will download text file with data based on number of records selected using checkbox from page. CSV will download comma separated values. XML will download XML file with data based on number of records selected using checkbox from page. In each case the user can select specific entries to include in the download by using checkboxes. The data can also be downloaded as a pipe-delimited text file from the NCBI ftp site (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/pub/taxonomy/biocollections/).

Duplicated or ambiguous collections and codes

For various reasons, some institutions use more than one institution code. For example, University of Maryland uses MARY for its herbarium collection and UMDC for its museum collection. These are listed as separate records. If an institution changes the code for its collection or institution and adopts a new one, the old code is retained in the database as a synonym. Similarly, when there are several institution codes for the same collection, they are listed as synonyms.

When more than one institution uses the same code for their specimen, the International Organization for Standardization three letter country code is used to unique the collections. If the institutions are from the same country, a state code is added in addition to country code. The institution code that is already in the database is retained (without the country code) and the subsequent ones are registered with country codes (state codes where applicable).

For example, all the following institutions use UAM as their institution code. To distinguish between the collections, the institution codes are listed as:

University of Alaska, Museum of the North UAM

University of Arkansas at Monticello UAM<USA-AR>

University of Alabama, Malacology Collection UAM<USA-AL>

Universidad Autonoma De Madrid culture collection of cyanobacteria UAM<ESP>

Universidad de los Andes, Facultad de Ciencias UAM<VEN>

Since University of Alaska, Museum of the North (UAM) was the first one to be registered in the BioCollections Database, UAM is retained for University of Alaska and the subsequent UAM codes are added with country and state codes. When a record is submitted to Genbank with an ambiguous code (ex: UAM), it prompts a consult so a curator can confirm the correct institution is listed.

Challenges of DwC Triplet

DwC Triplet creates an identifier for voucher specimens in the form <institution_code>:<OPTIONAL collection_code>:<specimen_id>. The problems with DwC Triplets as identifiers have been discussed before (9). There are many institutions that share the same institution code. We resolve this ambiguity by adding three letter country codes to the duplicated institution codes. This works well for our internal system i.e. to link BioCollections with GenBank records but may not find exact matches across other repositories. Adding to the problem, DwC Triplets are not formatted consistently and different collections codes could be used for a single institution. For example, we use UWBM: ORN: for University of Washington, Burke Museum Ornithology Collection, whereas VertNet Database (http://vertnet.org/) uses UWBM: BIRD: for the same collection. Furthermore, submitters are asked to fill in the voucher information when submitting sequences to GenBank but many don’t provide that information, thus, many voucher specimens are fielded as/strain or/isolate in GenBank records and cannot be linked to BioCollections. We have over 600 000 ATCC records that are formatted correctly as/culture_collection and are linked to BioCollections but there are about 76 000 ATCC records that are not formatted correctly and appear as/strain or/isolate in GenBank records. We are working on improving processes to correct the legacy records for which the culture collections acronyms are not ‘structured.’ Additionally, GenBank has recently started to automatically structure selected culture collections codes in new entries submitted as/strain or/isolate if they are from DSM, CBS, JCM, ATCC, LMG, NBRC, CCUG and KCTC. We selected these culture collection codes based on number of type strains we have in the taxonomy database (Table 2). Going forward, we will expand this list to other institution codes as well. Also, we would like to encourage submitters to provide specimen vouchers in a structured format so that they can be correctly linked to BioCollections by emailing updated information to gb-dmin@ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Table 2.

Top eight culture collections based on number of type strains in NCBI taxonomy database

| Culture collection | No. of type strains in Taxonomy database |

|---|---|

| Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH (DSM) | 9117 |

| Centraal bureau voor Schimmelcultures, Fungal and Yeast Collection (CBS) | 7667 |

| Japan Collection of Microorganisms (JCM) | 6980 |

| American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) | 6063 |

| Belgian Coordinated Collections of Microorganisms/LMG Bacteria Collection (LMG) | 3383 |

| NITE Biological Resource Center (NBRC) | 3352 |

| Culture Collection, University of Goteborg, Department of Clinical Bacteriology (CCUG) | 2855 |

| Korean Collection for Type Cultures (KCTC) | 2762 |

Often, institutions change their codes or are merged with other institutions. Linking mechanisms that depend on metadata like institution codes are prone to break as the metadata changes. The biodiversity community has long recognized the need for globally unique identifiers (GUID) to share, link and track biocollections data (specimen records, images, taxonomic names and DNA sequences) that are scattered all around the world. Several different technologies like Life Science Identifiers, Digital Object Identifiers, HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP) Uniform Resource Identifier-based identifiers etc. have been discussed for this purpose. More recently the use of GUID to provide stable identifiers for biocollections has gained traction (10–12). We will consider using these options as they become universally used in future.

External resources

Resources outside of NCBI are constantly reviewed to keep the NCBI BioCollections Database up to date. In the past, we have exchanged data with the Global Registry of Biodiversity, an online metadata resource that provides information on biodiversity collections (13). Recently, we imported about 300 institution codes from Index Herbariorum (6) and about 50 culture collections codes from World Federation of Culture Collections. Integrated Digitized Biocollections (iDigBio) is another resource that provides data and images for millions of biological specimens in electronic format (14) and ways to link iDigBio specimen records to GenBank sequences associated with those specimens should be further explored. In 2011, the Global Genome Biodiversity Network (GGBN) was created as a part of Global Genome Initiative to bridge the gap between biodiversity repositories, sequence databases and research (15). Through its Data Portal, GGBN aims to make biodiversity samples readily discoverable and accessible to the research community. We will continue to explore the possibilities of crosslinking and updating data in accordance with all these external resources.

We are in the process of cleaning and updating the information in the BioCollections Database and have already updated >200 records by contacting resource managers and asking them to verify and correct their relevant information. We are also requesting institutions to provide us with an URL rule to their catalogue page so we can cross link the data. At present, NCBI offers the ability for credible third party resources to link out directly from either sequence records or via taxonomic names in the Taxonomy Browser. LinkOut aims to facilitate another way to access relevant online resources and supplement information found in NCBI databases (16). Links could be expanded at these individual pages by collaborating with more biorepositories.

Addditional uses of BioCollections Database and future steps

Ideally, taxonomic vouchers should be expertly identified samples deposited and stored in a facility that is accessible to researchers for further study and thus serve an important role in biological research (17). For prokaryote names to be validly published, its type strains must be deposited in two recognized culture collections, a rule set by International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes under the International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes (18). Type strains in culture collections are the points of reference that other strains must be compared with when determining their taxonomic identity. Similarly, the International code for Nomenclature for algae, fungi and plants (19) and The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (http://iczn.org/code) also requires the designation of a type specimen, albeit with slightly different rules. The designation of vouchers is an important part of establishing provenance in systematic research and allows for critical assessment. With the increasing use of molecular sequences analysis in the systematics, it is important to establish a mechanism to connect these two sets of data. Besides taxonomic identification, associated metadata can provide important information on geographic dispersal and DNA can potentially be obtained for further research.

There are >1 600 000 species-level taxonomy ids in the NCBI Taxonomy database and they are identified with varying degree of certainty, with almost 400 000 identified with a binomial name. Type specimens have an important role in this regard, by providing a clear reference for comparison. We currently have just over 36 000 names with type material annotations. The complete list of type material annotations will be released as part of the taxonomy ftp files. Since 2013, GenBank curates type material in the Taxonomy Database and uses it to flag sequences from types in the sequence records. This has led to an improvement in the annotation of sequence records. Recently, GenBank has developed a protocol to identify and correct misidentified prokaryotic genomes, using Average Nucleotide Identity genome neighboring statistics in conjugation with reference genomes from type (20). In addition to this, GenBank, together with its collaborative partners in the INSDC, has accepted the addition of a new ‘type material’ qualifier for sequence records which will enable specific sequence records to be annotated automatically with information from the NCBI Taxonomy database (1). BioCollections Database can be used as a useful resource to facilitate the identification of the home institutions providing these important set of records and track these specimens. Furthermore, BioCollections can add value to other NCBI databases. In 2011, NCBI developed BioProject and BioSample databases to organize and integrate data across interdisciplinary resources and allow users to query across many NCBI databases to retrieve data relevant to their interest (21). BioSample can potentially include blood samples, cell cultures, individual organisms etc. that may come from culture collections, museums, herbaria or other repositories. Expanded links between BioCollections and BioSample database will help make these databases more comprehensive.

The individual biorepository pages in BioCollections can serve as a start site for users specifically interested in the breakdown of sequenced vouchers at a specific institution. For example, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History shares specimens and DNA samples with collaborators worldwide. As a result, DNA sequence data is submitted to Genbank, ENA and DDBJ by a large number of submitters and are often not formatted correctly and therefore are not linked to BioCollections Database. USNM (National Museum, >29 000 total records) and US (National Herbarium, > 16 000 total records) notations represent a large number of sequence records and are part of an important collaborative effort. The ‘USNM’ and ‘US’ strings were used to search the entire GenBank database, then manually checked to assure they referred to specimens as expected. This information was reported to Smithsonian where they were added to the databases of appropriate departments. Depending on the choice of the individual institution this can facilitate the linking of specimens to their sequence records. One option will be to provide LinkOuts to specific samples pages directly from sequence records.

We hope to expand the utility of the BioCollections Database in a similar fashion for other biocollections in future. In the meanwhile, this focused resource will continue to provide important institutional context to the large number of sequence records in the public sequence databases.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Scott Federhen and dedicate this paper in his memory. Scott initiated this resource at NCBI to promote linkage between sequence data and specimens and championed its release.

Funding

Funding for Open Access charge: Intramural Research Program of National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine.

Conflict of interest. None declared.

References

- 1. Mizrachi I., Takagi T., Cochrane G (2018) The International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration. Nucleic Acids Res., 46, D48–D51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wieczorek J., Bloom D., Guralnick R.. et al. (2012) Darwin Core: an evolving community-developed biodiversity data standard. PLoS One, 7, e29715.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benson D.A., Cavanaugh M., Clark K.. et al. (2018) GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res., 46, D41–D47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Toribio A.L., Alako B., Amid C.. et al. (2017) European Nucleotide Archive in 2016. Nucleic Acids Res., 45, D32–D36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mashima J., Kodama Y., Fujisawa T.. et al. (2017) DNA data bank of Japan. DNA Data Bank Jpn., 45, D25–D31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thiers B. Index Herbariorum: a global directory of public herbaria and associated staff New York Botanical Garden, New York. http://sweetgum.nybg.org/ih/ (15 October 2017, date last accessed).

- 7. Frost D. (2017) Amphibian species of the World: an online reference, Version 6.0. American Museum of Natural History, New York. http://research.amnh.org/herpetology/amphibia/index.html (15 December 2017, date last accessed).

- 8. Eschmeyer W.N., Fricke R., van der Laan R. Catalog of fishes. http://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/ichthyology/catalog/fishcatmain.asp (15 October 2017, date last accessed).

- 9. Guralnick R., Conlin T., Deck J.. et al. (2014) The trouble with triplets in biodiversity informatics: a data-driven case against current identifier practices. PLoS One, 9, e114069.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Güntsch A., Hyam R., Hagedorn G.. et al. (2017) Actionable, long-term stable and semantic web compatible identifiers for access to biological collection objects. Database, 2017, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guralnick R.P., Cellinese N., Deck J.. et al. (2015) Community next steps for making globally unique identifiers work for biocollections data. Zookeys., 494, 133–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Krishtalka L., Dalcin E., Ellis S.. et al. (2016) Accelerating the Discovery of Biocollections Data. GBIF Secretariat, Copenhagen: http://www.gbif.org/resource/83022 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schindel D.E., Miller S.E., Trizna M.G.. et al. (2016) The global registry of biodiversity repositories: a call for community curation. Global Registry Biodiv. Repositories: Biodivers Data J., 4, e10293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Soltis P.S., Godden G.T. (2014) A new iDigBio web feature links DNA banks and genetic resources repositories in the United States In: Applequist W.A., Campbell L.M. (eds). DNA Banking for 21st Century. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO, pp. 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Droege G., Barker K., Seberg O.. et al. (2016) The global genome biodiversity network (GGBN) data standard specification. Database, 2016, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kwan Y.K. (2013) LinkOut: linking to External Resources from NCBI Databases In: The NCBI Handbook [Internet], 2nd edn National Center for Biotechnology Information (US; ), Bethesda (MD: ). [Google Scholar]

- 17. Culley T.M. (2013) Why vouchers matter in botanical research. Appl. Plant Sci., 1, apps.1300076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parker C.T., Tindall B.J., Garrity G.M. (2015) International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., http://ijs.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/ijsem/10.1099/ijsem.0.000778#tab1. [Google Scholar]

- 19. McNeill J. et al. (2012) International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Melbourne Code), Vol. 154. In: McNeill (ed). Regnum Vegetabile. Koeltz Scientific Books, Königstein, p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Federhen S. (2015) Type material in the NCBI taxonomy database. Nucleic Acids Res., 43, D1086–D1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barrett T., Clark K., Gevorgyan R.. et al. (2012) BioProject and BioSample databases at NCBI: facilitating capture and organization of metadata. Nucleic Acids Res., 40, D57–D63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]