SUMMARY

While Slicer activity of Argonaute is central to RNAi, conserved roles of Slicing in endogenous regulatory biology are less clear, especially in mammals. Biogenesis of erythroid Dicer-independent mir-451 involves Ago2 catalysis, but mir-451-KO mice do not phenocopy Ago2 catalytic-dead (Ago2-CD) mice, suggesting other needs for Slicing. Here, we reveal mir-486 as another dominant erythroid miRNA with atypical biogenesis. While it is Dicer-dependent, it requires Slicing to eliminate its star strand. Thus, in Ago2-CD conditions, miR-486-5p is functionally inactive due to duplex arrest. Genomewide analyses reveal miR-486 and miR-451 as the major Slicing-dependent miRNAs in the hematopoietic system. Moreover, mir-486-KO mice exhibit erythroid defects, and double knockout of mir-486/451 phenocopies cell-autonomous requirements of Ago2-CD in the hematopoietic system. Finally, we observe that Ago2 is the dominant-expressed Argonaute in maturing erythroblasts, reflecting a specialized environment for processing Slicing-dependent miRNAs. Overall, the mammalian hematopoietic system has evolved multiple conserved requirements for Slicer-dependent miRNA biogenesis.

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

RNAi is a deeply conserved phenomenon that is typically associated with restriction of selfish genetic elements. Since its recognition, RNAi has been exploited as a powerful and versatile technique for gene suppression. Moreover, this genome defense mechanism has been repurposed for diverse strategies of endogenous gene regulation in different organisms, including via microRNA (miRNA) loci that modulate host transcriptomes. Nevertheless, if we consider the core of RNAi as the cleavage activity of specific Argonaute proteins, an activity that is conserved from archaebacteria to man, we still have relatively poor understanding of how this fundamental activity is involved in endogenous regulation.

This situation is exemplified in mammals. Amongst their four Ago-class proteins, Ago2 is recognized as the sole “Slicer” enzyme (Liu et al., 2004; Meister et al., 2004; Rand et al., 2004). Why does mammalian Ago2 retain this activity? Select mammalian cell types may utilize Ago2-driven RNAi to restrict viruses (Ding and Voinnet, 2014), but the interferon pathway is the dominant antiviral mechanism (Cullen et al., 2013). Other possibilities include highly-complementary miRNA targets (Karginov et al., 2010; Shin et al., 2010; Yekta et al., 2004), although the biological imperative to cleave these rare targets has not been demonstrated. Target cleavage by endo-siRNAs may be of broader impact. In particular, siRNAs from complementary gene/pseudogene transcript pairs are specifically found in mouse oocytes (Tam et al., 2008; Watanabe et al., 2008). A compelling demonstration of their functional importance is that oocyte-specific inactivation of Ago2 cleavage activity, achieved by conditional knockout of Ago2 in trans to a catalytically dead allele (Ago2-CD) (Cheloufi et al., 2010) causes oocyte arrest (Stein et al., 2015). Thus, siRNA-mediated regulation is surprisingly dominant over miRNA function in mouse oocytes (Ma et al., 2010; Suh et al., 2010). However, as the mouse oocyte siRNA system is driven by a rodent-specific Dicer isoform (Flemr et al., 2013), this does not represent a conserved usage of Ago2 catalysis.

The most overt conserved usage of mammalian RNAi, in terms of molecular mechanism and phenotypic requirement, seems to lie in miRNA biogenesis (Yang and Lai, 2010). Pan-vertebrate mir-451 bears a short hairpin structure, which causes it to bypass Dicer cleavage and instead load directly into Ago proteins. Ago2-mediated cleavage of the 3′ hairpin arm is prerequisite for maturation into functional miRNAs (Cheloufi et al., 2010; Cifuentes et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2010), involving 3′ trimming by PARN nuclease (Yoda et al., 2013). mir-451 is erythroid-specific (Patrick et al., 2010; Rasmussen et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2010) and its deletion in mice causes stress-induced erythroid defects. This appears to correlate with apparent erythroid defects in Ago2-CD homozygous mice (Cheloufi et al., 2010). Nevertheless, Ago2-CD homozygotes are perinatal lethal, whereas mir-451 knockouts (with or without deletion of its clustered locus mir-144) are fully viable and exhibit mild phenotypes under normal rearing. Moreover, irradiated mice rescued with Ago2-KO bone marrow reconstituted with Ago2-CD expression do not seem to phenocopy Ago2-CD mice (O’Carroll et al., 2007). Altogether, these studies indicate that a major requirement for Ago2 catalysis lies in erythroid maturation via Slicer-dependent miR-451, but suggest other regulatory requirements besides this miRNA.

Here, we reveal that the conserved, erythroid locus mir-486 also exhibits Ago2-Slicer dependence. Its atypical biogenesis was hidden because Slicing does not overtly affect the accumulation of mature strand miR-486-5p; instead, Ago2 cleavage removes its duplex passenger (3p) strand. By contrast, typical miRNA duplexes generally exhibit internal mismatches that promote Slicer-independent strand dissociation (Kawamata et al., 2009). We employ in vitro biochemistry, in vivo genetics, and genomewide approaches to demonstrate that miR-451 and miR-486 are the major mammalian Slicing-dependent miRNAs. We generate mir-486 knockout mice that exhibit erythroid differentiation defects and impaired homeostasis especially under stress conditions. Moreover, conditional ablation of Ago2 catalysis in the hematopoietic system closely resembles the effects of mir-486/451 double knockout mice, consistent with these being the major Slicer-dependent miRNAs. Interestingly, we find that the erythroid system is a unique tissue setting where sole expression of Ago2 amongst the four Argonautes is found. Thus, utilization of mammalian Slicer for atypical erythroid miRNA biogenesis appears to have co-evolved with a specialized Ago environment.

RESULTS

Distinct dependencies of erythroid loci mir-451 and mir-486 on Ago2 catalysis

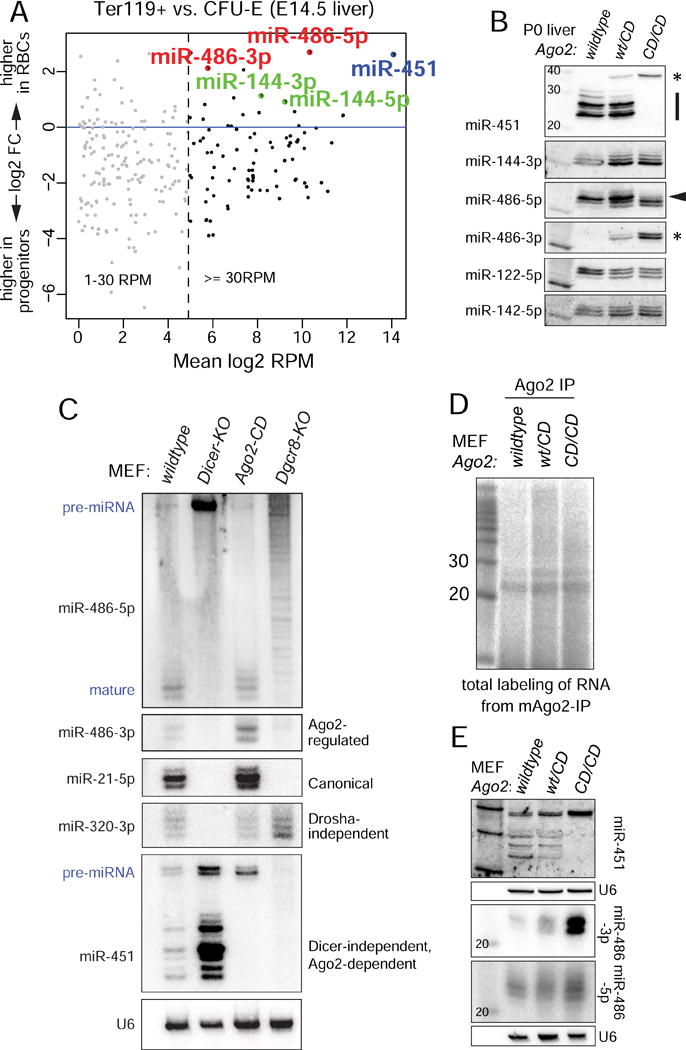

We explored miRNA expression during erythroid differentiation using available small RNA data (Zhang et al., 2011). As reported, Ago2-dependent miR-451 is a dominant miRNA in committed erythroid progenitors (CFU-E) and its levels increase to constitute the majority of miRNA reads in resultant Ter119+ mature erythroblasts from fetal liver (Figure 1A). The miR-451 cluster partner miR-144 was not upregulated to the same extent, reflecting non-canonical biogenesis of the former and/or differential stability or turnover. Of note, the locus most elevated in mature erythroblasts was miR-486-5p, and its partner “star” strand miR-486-3p was similarly elevated although it reached a lower level (Figure 1A). We investigated whether these miRNAs were affected in other datasets, including from control and homozygous Ago2-CD fetal liver (Cheloufi et al., 2010). As reported, miR-451 was the most down-regulated miRNA between these datasets. Curiously, miR-486-3p was the most up-regulated miRNA in Ago2-CD liver; miR-486-5p was modestly reduced in Ago2-CD (Figure S1A).

Figure 1. miR-486 is an atypical Ago2 slicing-dependent, erythroid locus.

(A) Analysis of small RNA libraries comparing miRNA reads between CFU-E erythroid progenitors and Ter119+ mature erythroblast cells. miR-451 and miR-486 are the highest upregulated miRNAs during erythropoiesis. (B) Northern blotting of endogenous miRNAs from wildtype, heterozygous, and homozygous Ago2-CD P0 liver. Note pre-mir-451 and miR-486-3p accumulation (denoted by asterisks). (C) Wildtype and mutant mouse embryonic fibroblasts for the indicated factors were transfected with mir-486 and mir-144/451 expression constructs and blotted for the indicated ectopically expressed or endogenously expressed miRNAs. (D) Total labeling of small RNAs immunoprecipitated with Ago2 from wildtype, Ago2-CD/wt, and Ago2-CD/CD MEFs. Comparable amounts of small RNAs in miRNA-sized range (~21-25nt) are observed. (E) MEFs generated from wildtype, heterozygous, and homozygous Ago2-CD embryos were used to test the patterns of miR-486 and miR-451 maturation. Strong upregulation of miR-486-3p is noted.

We confirmed this with Northern blotting from P0 liver (Figure 1B). While control miRNAs were relatively unaffected by Ago2 catalytic status, we observed dramatic alterations in mir-451 and mir-486. Wildtype liver expressed mature miR-451 species, whereas Ago2-CD accumulated exclusively the pre-mir-451 precursor. miR-486-5p was easily detected in both genotypes, although a shift towards shorter isoform lengths was apparent in Ago2-CD liver. Importantly, miR-486-3p was specifically and abundantly detected only in Ago2-CD conditions (Figure 1B). We even observe a dominant effect, in that Ago2-CD heterozygous liver accumulated intermediate levels of both pre-mir-451 and miR-486-3p. Overall, while Slicer function is not generally needed for miRNA biogenesis, two major erythroid-upregulated miRNAs are affected by Slicer activity, albeit in opposite fashion.

We probed the biogenesis of mir-486 further using mutant cell lines (Figure 1C). We tested dependencies on the nuclear Drosha RNase III complex using MEFs lacking the obligate Drosha cofactor DGCR8. These cells cannot initiate biogenesis of canonical mir-21 or Dicer-independent mir-451, but readily mature the Drosha-independent miR-320. Maturation of a mir-486 expression construct was completely impaired in Dgcr8-KO MEFs (Figure 1C). In the cytoplasm, the RNase III Dicer is required for biogenesis of miR-21 and miR-320, but miR-451 matures effectively in Dicer-KO cells. Certain well-paired pre-miRNAs can be nicked on their 3′ hairpin arms by Ago2 (Diederichs and Haber, 2007; Kim et al., 2016), which may potentially allow them to access a miR-451-like Dicer bypass pathway. However, maturation of mir-486 was fully arrested as a pre-miRNA in Dicer-KO MEFs (Figure 1C).

We next tested the behavior of miRNAs in Ago2-KO MEFs that were reconstituted with hAgo2 or hAgo2-CD. As we showed earlier (Yang et al., 2010), hAgo2-CD cells cannot support maturation of miR-451. When mir-486 was introduced into these cells, we observed only minor differences in the accumulation of miR-486-5p. In contrast, the star strand miR-486-3p accumulated in Ago2-KO MEFs and Ago2-CD rescue MEFs, particularly under IP conditions. This was specifically due to Slicing, since Ago2-KO MEFs rescued with wildtype Ago2 could clear miR-486-3p, but cells rescued with Ago2-CD could not (Figure S1B).

Since the Ago2-KO MEF rescue system expresses ectopic Ago2 proteins, and potential phenotypic discrepancies between Ago2-CD rescue and knockin systems have been observed (Cheloufi et al., 2010; O’Carroll et al., 2007), we developed new MEF lines from Ago2-CD knock-in mice. Western blotting showed that heterozygous and homozygous Ago2-CD cell lines accumulate comparable levels of Ago2 protein as control MEFs (Figure S1E). Labeling of total small RNAs in Ago2-IP samples showed that similar levels of miRNA species immunoprecipitate with normal and Ago2-CD proteins (Figure 1D), indicating that bulk miRNA biogenesis appears normal in Ago2-CD knockin MEFs. Using these cell lines, we confirmed that miR-451 maturation and miR-486-3p accumulation were dose-sensitive to endogenous Slicing status (Figure 1E). In particular, miR-486-3p accumulated to much higher levels in Ago2-CD/CD cells than in wildtype cells, and was intermediate in heterozygous cells; miR-486-5p was relatively unaffected across these genotypes.

In summary, Ago2-mediated catalysis has dramatic, seemingly opposing effects on two dominant erythroid miRNAs: it promotes maturation of miR-451 and suppresses accumulation of the miR-486 star strand.

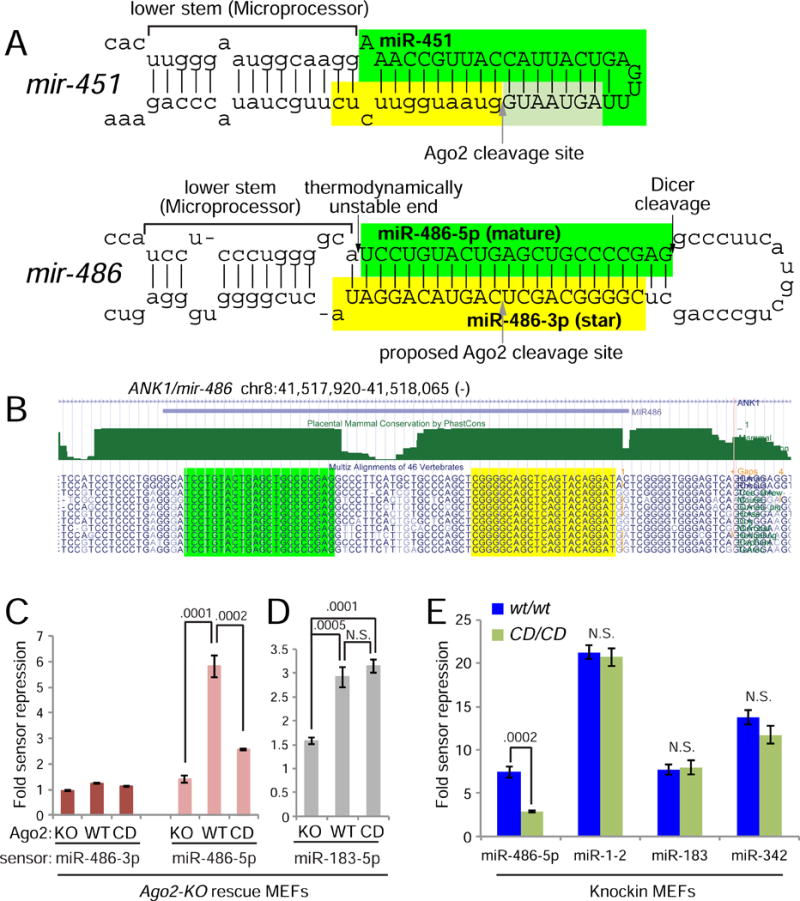

Slicing is required to generate functional miR-486-5p via passenger strand cleavage

What makes mir-486 sensitive to Slicer activity? Inspection of the mir-486 locus revealed an unusual structure. Nearly all miRNAs exhibit internal mismatches and/or bulged positions within the pre-miRNA duplex stem, which facilitate strand dissociation during miRISC maturation (Kawamata et al., 2009). In contrast, pre-mir-486, encompassing its entire miRNA/star duplex, is perfectly paired (Figure 2A). This aspect of mir-486 is not incidental, since it is perfectly conserved across mammalian species (Figure 2B). This may conceivably reflect a conserved activity of the star strand miR-486-3p (Yang et al., 2011). However, the highly paired pre-mir-486 structure also resembles those of siRNA duplexes, which depend on Ago2-mediated cleavage to remove the passenger strand during in vitro RISC assembly (Leuschner et al., 2006; Matranga et al., 2005; Miyoshi et al., 2005; Rand et al., 2005).

Figure 2. miR-486 is a perfectly conserved mammalian locus whose function depends on Ago2 slicing.

(A) Secondary structures of mir-451 and mir-486 primary hairpin are shown; both exhibit atypical fully-paired duplex stems. (B) The mir-486 hairpin is fully conserved across placental mammalian species. (C–E) Luciferase sensor assays in Ago2-KO MEFs, and Ago2-KO cells reconstituted with hAgo2-wt or hAgo2-CD (C and D) and in MEFs derived from Ago2-CD knockin and control mice (E). (C) miR-486-3p is not a functional miRNA, but the role of Ago2-Slicing is to promote miR-486-5p activity on targets. (D) Canonical control miR-183 is not functionally sensitive to Slicing. (E) miR-486-5p shows blunted activity in Ago2-CD/CD MEFs while canonical miRNA controls are not affected.

These considerations suggested two major possibilities for the consequence of Slicing on mir-486 biogenesis. Typically, upregulation of a ~22 nt miRNA species might be expected to correlate with increased activity in target silencing. However, an opposite interpretation is that accumulation of the star strand interferes with maturation, and thus activity, of the mature miR-486 strand. To distinguish these possibilities, we performed functional sensor assays using bulged sensors. Using the Ago2-KO MEF system, we observed that miR-486-3p sensor was not regulated by mir-486 under any Ago2 allelic state tested (Ago2+, Ago2-KO or Ago2-CD) (Figure 2C). This result is seemingly at odds with recent studies of miR-486-3p as a functional species (Bianchi et al., 2015; Lulli et al., 2013). However, the prior studies utilized miRNA mimics that circumvent normal biogenesis and force the occupancy of the desired small RNA as a guide molecule. Our assays demonstrate that miR-486-3p is normally poorly competent for gene regulation. In contrast, expression of mir-486 resulted in robust suppression of a miR-486-5p sensor, but its activity was blunted in Ago2-KO and Ago2-CD cells (Figure 2C). Meanwhile, activity of the canonical locus mir-183 was not affected by Ago2 catalytic status (Figure 2D). We extended this by assaying a panel of miRNA sensors (mir-486, mir-1-2, mir-183, mir-342) in control and Ago2-CD knockin MEFs, and again observed selective impairment of miR-486 function by loss of Ago2 catalysis (Figure 2E). Thus, the primary role of Slicing is not to suppress miR-486-3p as a regulatory molecule, but instead to promote miR-486-5p function.

These data strongly suggested that mir-486 requires slicing to remove its star strand. We tested this scenario by immunoprecipitating wt and catalytically inactive Ago2, and observed that miR-486-3p specifically accumulated in Ago2-CD complexes (Figure S1B). We further compared the small RNAs associated with Ago2 and non-slicing Argonaute by cotransfecting miRNA expression vectors with myc-hAgo1, −2 or −3 constructs and immunoprecipitating individual Ago proteins. As we reported, maturation of mir-451 was fully arrested at the pre-miRNA stage in hAgo1 and hAgo3 complexes (Yang et al., 2012), whereas mature miR-451 was present only in hAgo2 (Figure 3A). On the other hand, mature arm miR-486-5p accumulated relatively similarly across these Ago proteins, except that a slightly longer species accumulated in hAgo1. Different Argonautes are known to protect slightly different lengths of miRNAs (Juvvuna et al., 2012). Strikingly, only hAgo1 and hAgo3 associated with miR-486-3p, indicating that endogenous accumulation of this species is a consequence of loading into non-Slicing Argonautes (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Mechanistic analysis of miR-486 maturation.

(A) Wildtype MEFs transfected with myc-hAgo constructs and miR-451 and miR-486 were probed for miRNA species associated with the denoted Ago-IP material. (B–C) In vitro cleavage assays of radiolabeled duplex mir-486 in reactions containing lysates prepared from Ago2-CD MEFs expressing the indicated Argonaute. Duplex RNA substrates containing radiolabel of either the 5p or 3p species were tested. (D) Native PAGE Northern blot analysis of miRNA species associated with Ago2 from wildtype, heterozygous, homozygous Ago2-CD MEFs. Single-stranded and duplex radiolabeled mir-486 are shown as markers.

We next assayed directly for generation of cleaved passenger strands. We incubated radiolabeled miR-486 duplex substrate with MEF lysate to allow for Ago loading and potential cleavage and analyzed the products on denaturing gels. When the star strand was 5′-radiolabeled, we observed accumulation of a ~10 nt fragment corresponding to the 5′ product of Ago2-cleavage (Figure 3B). However, when the 5p species in the duplex was 5′-radiolabeled, no products were generated. This confirms that the in vitro system asymmetrically orients the duplex and retains the mature strand, and exclusively positions the 3p strand for cleavage. To verify that this was due to slicing, we performed comparable assays using lysates from Ago2-CD MEFs and found that no miR-486-3p cleaved products were generated (Figure 3B).

Mammalian Ago2 was initially classified as the sole Ago-class Slicer enzyme (Liu et al., 2004; Meister et al., 2004; Rand et al., 2004), but Ago1 and Ago3 were reported to cleave certain substrates (Park et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2009). However, when we analyzed lysates from Ago2-CD MEFs transfected with Ago1 and Ago3 in parallel to Ago2 transfection samples, only Ago2 generated cleaved miR-486-3p (Figure 3C). These assays suggest that in the absence of Ago2 catalysis, mir-486 biogenesis is arrested at the duplex stage. To assay for this, we immunoprecipitated Ago2 complexes from wildtype, Ago2-CD/+, or Ago2-CD/CD MEFs expressing mir-486, and analyzed their contents on native gels. We observed that miR-486-5p migrated as a single-stranded species when isolated from Ago2-wt, but was predominantly found in a double-stranded form in Ago2-CD (Figure 3D). Tests of miR-486-3p showed that it did not accumulate in Ago2-wt complexes, consistent with total RNA analyses, but that it was present essentially solely in duplex form in Ago2-CD (Figure 3D). We further tested control miRNAs and found they existed in predominantly single-stranded complexes in wt and Ago2-CD conditions (Figure 3D). In sum, these data reveal a specific and obligatory in vivo requirement of Ago2-slicing for passenger strand removal in an endogenous miRNA.

Bypassing Ago2-dependent biogenesis of mir-486 by structural alterations in cis or by activating slicing in Ago1/3/4

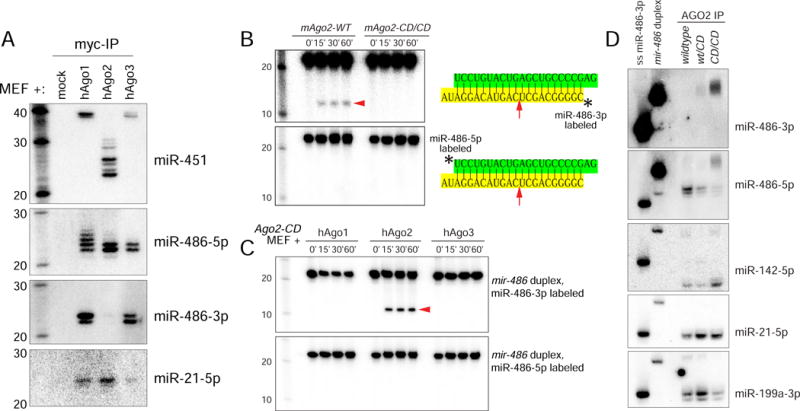

Although Ago2 is the main endogenous Slicer, other mammalian paralogs retain potential catalytic residues. In fact, appropriate modifications can activate slicing capacity in mammalian Ago1/3/4, and thereby support miR-451 biogenesis to varying extents (Faehnle et al., 2013; Hauptmann et al., 2013; Nakanishi et al., 2013; Schurmann et al., 2013). We confirmed this by transfecting catalytically activated Ago1/3/4 into Ago2-CD/CD MEFs. We observed that cat-Ago1 supported normal levels of miR-451 maturation, while cat-Ago3 and cat-Ago4 exhibited modest, but detectable, activity in this respect (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Cis and trans rescue of miR-486 function and genomewide analysis of slicing dependent miRNAs.

(A) Rescue of miR-451 maturation and miR-486-3p clearance upon expression of catalytically reprogrammed Argonautes. Northern blotting of miRNAs in Ago2-CD MEFs expressing denoted wildtype and reprogrammed Ago. (B) Quantification of biological triplicate reprogrammed Ago rescue experiments, representative blot of which is shown in Figure 4A. (C) Rescue of miR-486 function in Ago2-CD MEFs via expression of catalytically reprogrammed Argonautes. Luciferase sensor assay using miR-486-5p sensor. (D) Diagram of hairpin secondary structures of wildtype and bulge mutant miR-486. (E) Luciferase sensor assays in Ago2 wt/wt, wt/CD, CD/CD MEFs to test the activity of wildtype and bulge mutant miR-486. (F) Plot showing the distribution of conserved miRNAs that contain varying number of continuous base pairs along their stem. (G) Plot showing distribution of miRNAs ordered based on minimum free energy of their hairpins. (H) Scatter plot showing the log2 fold change and mean log2 reads per million comparing miRNAs in Ago2-IP from wildtype and Ago2-CD/CD fetal liver. Biologically replicate libraries were sequenced and analyzed for each condition.

We then analyzed the capacity for catalytically activated Agos to mature mir-486. Elevation of generic Argonaute proteins can increase the levels of canonical miRNAs from cotransfected constructs (Diederichs and Haber, 2007). Thus, mature miR-144 produced from the mir-144/451 expression vector increased upon cotransfection of Ago2 or other Ago constructs (Figure 4A). However, we observed an opposite response of miR-486-3p, whose accumulation was suppressed by Ago2 and catalytically activated Ago proteins. Quantifications of biological triplicate experiments are shown in Figure 4B. The level of miR-486-3p suppression correlated with their ability to mature miR-451, with cat-Ago1 performing nearly as well as Ago2 in reducing miR-486-3p. Sensor assays verified that the cat-Agos were also able to promote repression activity of miR-486-5p, with the relative sensor repression correlating with the relative decrease in the levels of inhibitory miR-486-3p (Figure 4C). Thus, it is the unique slicing activity of Ago2 and not other intrinsic properties of this enzyme that matures active miR-486-5p.

We investigated an alternate strategy for mir-486 to bypass Ago2 function, by converting it into a conventional miRNA backbone with bulges at nts 10-11 from the miR-486-5p 5′ end (mir-486-bulge) (Figure 4D). When we compared these constructs in functional sensor assays, we observed that wildtype mir-486 function was impaired in Ago2-CD knockin cells (Figure 4E), as in the Ago2-CD reconstituted cell system (Figure 2C), whereas activity of mir-486-bulge was similar in wt, wt/Ago2-CD, and Ago2-CD/CD MEFs (Figure 4E).

Overall, these data from cis (miRNA hairpin modification) and trans (cat-Ago) strategies to bypass the requirement of Ago2 slicing support the notion that star strand clearance underlies guide strand function of mir-486.

Genomewide analyses show mir-486 as the dominant conserved miRNA controlled by Slicing

We next compared the structural and sequence properties of mir-486 to all other conserved mammalian miRNA loci. These analyses showed that mir-486 exhibited the most continuous duplex pairing, the lowest free energy of pri-miRNA, pre-miRNA and miRNA/star duplex structures, and had the highest G:C content in its duplex (Figure 4F–G and Figure S2). Therefore, mir-486 has been uniquely selected for its extensive pairing and low free energy, features that underlie its requirement for Slicer-dependent mechanism to remove its passenger strand. We emphasize these idiosyncratic mir-486 features are absolutely conserved across mammals (Figure 2B).

We then directly interrogated the small RNA content of Ago2 immunoprecipitates (Ago2-IP) from wt and Ago2-CD/CD fetal liver by sequencing biologically replicate libraries to depths of 15-26M reads (Table S1). The miRNA contents of Ago2 in wt and Slicer-deficient conditions were remarkably similar except in two regards: Ago2-CD was markedly decreased in miR-451 and reciprocally increased in miR-486-3p (Figure 4H). Overall, these genomewide analyses provide clear evidence that miR-451 and miR-486 are the dominant Slicer-dependent miRNAs in fetal liver, site of hematopoiesis in the developing mouse embryo. Moreover, these data raised the possibility for functional linkages between loss of these slicing dependent miRNAs and the phenotype of Slicing deficient mice, especially considering these two miRNAs are the most highly upregulated and expressed miRNAs in maturing erythroblasts (Figure 1A).

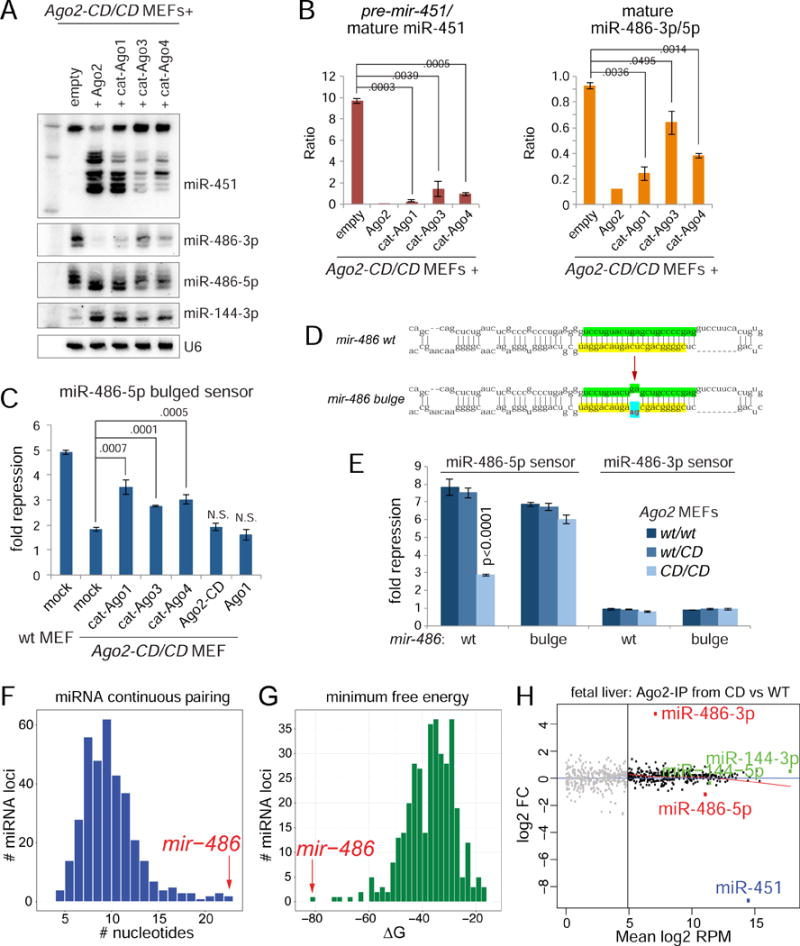

mir-486-KO mice reveal defects in erythroid maturation

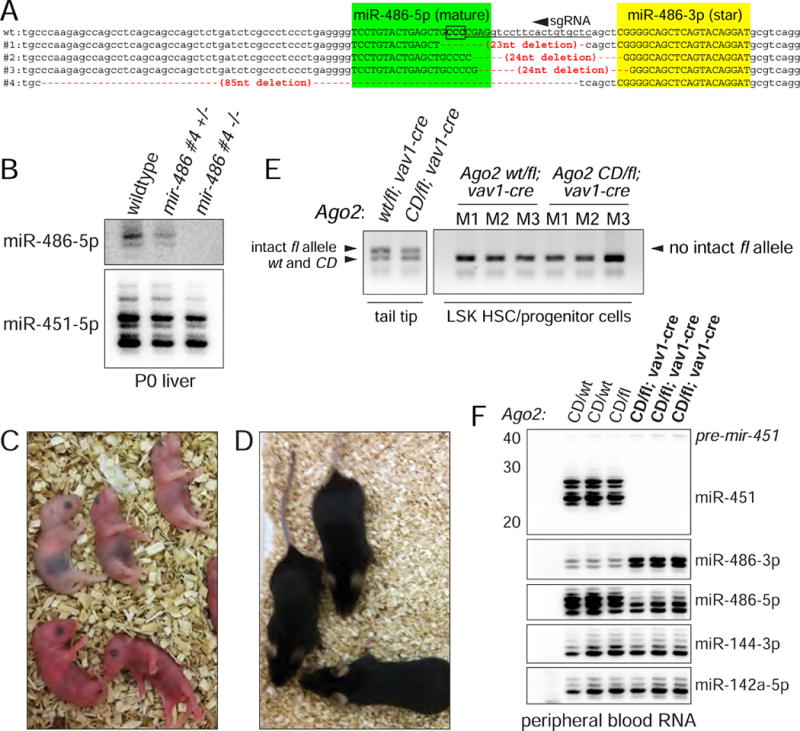

miR-486 dysfunction has been implicated in diverse developmental, disease and cancer contexts (Alexander et al., 2014; Peng et al., 2013; Shaham et al., 2015; Small et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2015). However, to date, no study has employed a genuine knockout model. Given frequent discrepancies of antisense and knockout methods (Sun and Lai, 2013), we employed CRISPR/Cas9 to generate multiple mir-486 mouse mutants (Figure 5A). All of these alleles were homozygous viable, and Northern blotting confirmed lack of mature miR-486 (Figure 5B). We used the 85 nt deletion (#4) that completely deletes mature miR-486-5p for detailed studies.

Figure 5. Mouse models for mir-486-KO and conditional Ago2-CD.

(A) CRISPR/Cas9-induced alleles of mir-486. Shown is the sense strand of the mir-486 locus, with the mature (green) and star (yellow) sequences in uppercase. The sgRNA region is underlined and the PAM is boxed (on the antisense strand). We used zygote injection of Cas9/sgRNA to recover four different alleles that delete the mir-486 loop and into the miR-486-5p sequence to varying extents. One of these alleles, #4, is an 85 nt deletion that completely removes mature miR-486-5p. (B) Northern blot validation that mir-486 mutant mice fail to express mature miR-486-5p. (C) Ago2-CD homozygous mice die within the first day of birth. (D) vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] conditional mutants of Ago2 catalysis in the hematopoietic system are adult viable. (E) Genotyping of sorted LSK HSC/progenitor cells from vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] mutant and vav1>Ago2[fl/WT] control mice shows that no intact floxed allele is detected, indicative of full recombination. (F) Northern blotting of peripheral blood total RNA from control and vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] mice validate functional deletion of floxed Ago2 allele in the hematopoietic compartment. Note complete absence of mature miR-451 and concomitant accumulation of miR-486-3p in vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] mutants.

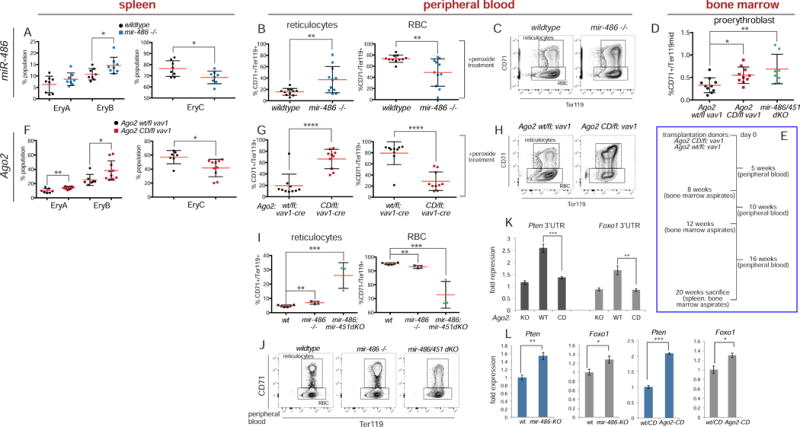

We assessed potential defects in hematopoietic tissues in mir-486-KO mice. While we did not observe significant deviations in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and various hematopoietic progenitor populations, we observed defects specifically in the erythroid lineage in the bone marrow, notably in the proerythroblast population (Figure S3). Furthermore, when we examined erythroid progenitors in the spleen of mir-486-KO mice, we observed a clear accumulation of the early erythroblast population EryB and a reduction in EryC late stage erythroblasts (Figure 6A; Figure S4A shows representative FACS plots). The phenotype in erythroid progenitor populations suggested a potential effect on the levels of mature red blood cells in the circulation. Indeed, when we examined the peripheral blood, we found a significant reduction in the proportion of mature red blood cells and an accumulation of immature reticulocytes in mir-486-KO mice (Figure S4C).

Figure 6. Erythroid-specific phenotype in mir-486-KO and vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] conditional mutant mice and genetic relationship between erythroid miRNAs and Ago2 mutants.

(A) FACS analysis of erythroid progenitors in wildtype and mir-486-KO spleen. (B and C) Peripheral blood FACS analysis of wildtype and mir-486-KO mice after hydrogen peroxide treatment. (D) Bone marrow FACS analysis of conditional Ago2 mutants and mir-451/486-dKO mice and controls shows accumulation of proerythroblast population in both Ago2 and miRNA mutants. As noted in main text, miR-dKO also lacks the clustered mir-144, which does not contribute to erythroid phenotypes. (E) Experimental diagram for transplantation of bone marrow from conditional Ago2 mutants and controls and followup analysis. (F) Spleen FACS analysis shows accumulation of EryA and EryB erythroblasts and reduction in proportion of EryC population in vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] transplant recipients. (G and H) Peripheral blood FACS analysis of vav1>Ago2[fl/wt] control and vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] recipient mice after hydrogen peroxide treatment shows shift to greater proportion of reticulocytes in conditional Ago2 mutants. (I and J) FACS analysis of peripheral blood from wildtype, mir-486-KO, and mir-451/486-dKO mice. More pronounced RBC maturation defect, accumulation of immature reticulocytes in mir-451/486-dKO mice. (K) Luciferase assays of 3′ UTR sensors in Ago2-KO MEFs and those rescued with Ago2-WT or CD constructs. (L) qPCR of Pten and Foxo1 show target derepression in mir-486-KO and Ago2-CD fetal liver. Error bars, st dev. P values * <.05 **<.01 ***<.001 ****<.0001.

Because erythroid phenotypes in the spleen can suggest defects in the erythroid stress response, we isolated peripheral blood from mir-486-KO and wildtype control mice and exposed them to H2O2-induced oxidative stress. We observed greater reduction in the proportion of red blood cells in mutant peripheral blood compared to control, accompanied by increase in proportion of reticulocytes (Figure 6B and C). To extend this to organismal erythroid homeostasis, we treated mir-486-KO and wildtype mice with phenylhydrazine, an erythroid oxidative stressor, and monitored red blood cell counts and hematocrit in peripheral blood. Consistent with the in vitro results, we found that there was a greater reduction in the red blood cell counts and volume in mir-486-KO mice compared to controls in response to drug treatment (Figure S4D).

Conditional Slicer deficiency in the hematopoietic system phenocopies mir-486/mir-451 dKO

The erythroid phenotypes we find in the mir-486 mutants resemble those of mir-451 mutants. Furthermore, because small RNA libraries prepared from Ago2-wt and Ago2–CD mice reveal these two miRNAs to be the sole miRNAs affected by Slicer activity in hematopoietic tissue (Figure 4H), we reasoned that deletion of both Slicing-dependent miRNA loci might provide insight into Ago2-CD mice. We confirmed that Ago2-CD homozygotes are perinatal lethal (Figure 5C). However, while it was suggested these mice are anemic (Cheloufi et al., 2010), it was unclear if this was due to an autonomous defect in the blood system.

In order to employ an accurate reference for Slicing deficiency in hematopoietic lineages, we generated conditional catalytic dead mutants, in which the Ago2-CD allele is placed over an Ago2-fl allele whose recombination is driven by vav1-cre (vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] mice). Such mice permit assessment of cell autonomous effects of Ago2-CD in hematopoietic lineages, as the vav1-cre allele directs recombination throughout the entire hematopoietic compartment during embryogenesis (de Boer et al., 2003). Surprisingly, unlike the originally reported Ago2-CD knockin mice, the conditional Ago2-CD mutant mice were viable, survive into adulthood and breed normally (Figure 5D).

As conclusions from these mice depend on fully penetrant recombination in hematopoietic cells, we undertook stringent testing to confirm deletion of the floxed Ago2 allele. Using primers detecting wt, CD, and floxed Ago2 alleles, we genotyped LSK HSC/progenitor cells which were sorted from vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] and vav1>Ago2[fl/WT] mice. We found full recombination in these cells with no detection of the intact floxed allele with 40 cycles of amplification, while we could readily detect the mutant CD allele (Figure 5E). In addition, as a functional readout for slicing status in hematopoietic cells of conditional Ago2 mutants, we performed Northern blotting of peripheral blood total RNA. Whereas control miRNAs were unaffected, we observed full arrest of miR-451 at the pre-miRNA stage and also strong accumulation of miR-486-3p in vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] mice, confirming a clean knockout of the floxed allele in hematopoietic compartments (Figure 5F).

Similar to mir-486 mutants, we found an erythroid specific phenotype in vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] mice compared to matched vav1>Ago2[fl/WT] control mice. While we did not observe differences in other hematopoietic lineages (Figure S5A), we found accumulation of the proerythroblast population of the erythroid lineage in the bone marrow (Figure 6D). We also observed an erythroid phenotype in the spleen of conditional Ago2 mutants. There was an accumulation of EryA erythroblasts, accompanied by reduction of downstream EryC cells (Figure S5B). When we examined the peripheral blood, we found a shift in balance to immature reticulocytes versus mature red blood cells in conditional Ago2-CD mice (Figure S5C).

To test the cell autonomous phenotype associated with Ago2 slicing more stringently, and to overcome the limitation in the number of conditional Ago2 mutants obtained by the necessary crossing schemes, we performed transplantation of isolated bone marrow from vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] and matched control vav1>Ago2[fl/WT] mice into 10 lethally irradiated recipients each, respectively (Figure 6E). We found stable engraftment of ~90% for all recipient mice (Figure S6A). Interestingly, we found a 2-3 fold accumulation of the proerythroblast population in Ago2 mutant recipients versus controls in the bone marrow at all of the timepoints examined (8, 12, 20 weeks) (Figure S7), consistent with the phenotype observed in the primary donor mice.

We also examined the peripheral blood at various timepoints post transplantation and consistently found increased values in the reticulocyte population and a reduction in mature red blood cells in vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] transplanted mice, phenotypes that were greatly enhanced by H2O2 treatment and which were reminiscent of those observed in mir-486-KO mice (Figure 6G and H; compare to Figures 6B and C showing mir-486-KO). Lastly, upon sacrifice at 20 weeks post transplant, we assessed erythropoiesis in the spleens and found EryA and EryB erythroblast accumulation and EryC reduction, consistent with the phenotype observed in mir-486-KO mice, as well as the primary Ago2 conditional mutants (Figure 6F; compare to Figure 6A showing mir-486-KO). In sum, the defect in erythroblast maturation observed in the bone marrow and spleen and the resultant phenotype in the mature peripheral blood of conditional Ago2 mutants reveal a cell autonomous role for slicing in the erythroid compartment that resembles the mir-486-KO phenotype.

In order to gain further insight into the genetic relationship between the slicing dependent miRNA loci and Ago2 slicing, we crossed the mir-486 knockout mice to a strain deleted for the mir-144/451 cluster (Yu et al., 2010). We note that other detailed comparisons of independent mir-451 and mir-144/451 deletion alleles clearly show that erythroid phenotypes and target gene derepression are primarily attributable to loss of miR-451 (Rasmussen et al., 2010). For simplicity, we refer to double knockout of the two loci (comprising three miRNAs) as “miR-dKO”, but we expect the major phenotypes to be due to loss of the Slicing-dependent miRNAs miR-486 and miR-451. Indeed, deletion of both miR-451 and miR-486 resembled vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] mice, in that the peripheral blood of the miR-dKO mice demonstrated a dramatic shift in favor of immature reticulocytes (Figure 6I and J), similar to what is seen in the blood of both primary vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] and transplant recipient vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] mice (Figure S5C and Figure 6G, respectively). We also found that the bone marrow of the miR-dKO mirrored that of primary and transplant vav1>Ago2[fl/CD] mice in accumulation of the proerythroblast population (Figure 6D; Figure S3A shows single and double miR-KO).

We extended these phenotypic connections by showing that repression of validated miR-486-5p targets Pten and Foxo1 in luciferase sensor-3′ UTR assays is fully dependent on endogenous Ago2 catalytic activity (Figure 6K), and that both genes are upregulated in mir-486-KO and Ago2[CD/CD] fetal liver (Figure 6L). These molecular connections are notable given the highly specific alterations we detected in the miRNA profile of Ago2[CD/CD] tissue (Figure 4H). In sum, we demonstrate conditional loss of Ago2 catalysis in the hematopoietic system yields specific defects in erythroid homeostasis, and link this to loss of atypical conserved miRNAs that require Ago2 Slicing for their biogenesis and function.

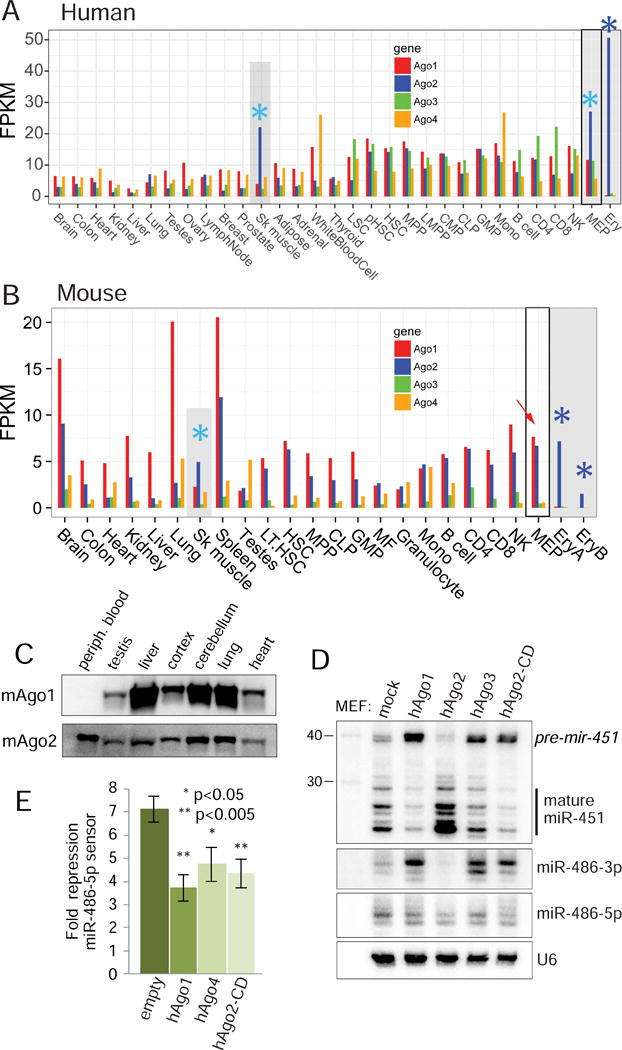

Specialized Ago environment in the erythroid system is needed for proper maturation and function of Ago2-dependent miRNAs

To gain further insight into why Slicing is of particular importance in the erythroid system, we examined the spatial expression of the four Ago-class genes. Surveying a broad panel of human tissue data (Figure 7A), almost all settings coexpress multiple Ago genes. Diverse hematopoietic cell types coexpress multiple Ago transcripts but there is a distinctive Ago2-only gene expression signature in erythroid cells. We also examined the four Ago-class genes in RNA-seq data from a broad panel of mouse tissues (Figure 7B) and found remarkable concordance with expression patterns in human, with both species showing a distinct Ago2-only expression signature in the erythroid lineage. In the mouse in particular, even megakaryocytic erythroid progenitor (MEPs), which give rise to red blood cells, express comparable levels of Ago1/2. However, in maturing erythroblast populations (EryA and EryB), there was a distinctive and abrupt change in Ago gene expression, such that only Ago2 was detected (Figure 7B). We confirmed these genomics data with Western blotting for Ago1 and Ago2 across a panel of mouse tissues, and find that only peripheral blood exhibits a bias towards sole expression of Ago2 (Figure 7C). These expression data correlate well with the notion that the erythroid lineage specifically upregulates multiple Ago2-dependent miRNAs. Interestingly, the only other tissue type in human and mouse where Ago2 is the dominantly expressed Argonaute is skeletal muscle (Figure 7A–B), which is the other location of mir-486 expression (Alexander et al., 2011; Small et al., 2010). Thus, although miR-451 is well-known as an erythroid Slicing-dependent miRNA, the expression bias of Ago2 is better correlated to that of the newly recognized Slicing-dependent miR-486.

Figure 7. Specialized Ago environment in the erythroid system is needed for proper maturation and function of Ago2-dependent miRNAs.

(A–B) Ago1/2/3/4 expression levels from RNA-seq data from diverse tissues and hematopoietic populations in human (A) and mouse (B). Multiple Argonautes are coexpressed across most tissues and cell types with a few exceptions, marked in gray and noted with asterisks. Within the human hematopoietic system, Ago2 becomes elevated above Ago1/3/4 within the megakaryocytic erythroid progenitor (MEP), and becomes the sole Argonaute expressed in maturing erythroblasts (Ery, blue asterisk). Similarly, Ago2 is coexpressed with Ago1 in mouse MEPs, but is exclusively expressed in early and late erythroblast populations (EryA and EryB, blue asterisks). The Ago2-Slicer dependent miRNAs miR-451 and miR-486 are the top upregulated miRNAs during this transition (Figure 1A). In addition, Ago2 is elevated relative to other Agos in skeletal muscle of both species (aqua asterisks), which is the other location of dominant miR-486 expression. (C) Ago1/2 Western blotting of lysates prepared from wildtype mice tissues. (D) Northern blotting of miRNAs transfected in MEFs expressing the indicated Argonautes shows inhibitory effect on the biogenesis of slicing dependent miRNAs by non-Slicer Argonautes; i.e. loss of mature miR-451 and accumulation of miR-486-3p. (E) Luciferase sensor assays show that expression of non-slicing Argonautes inhibits the function of miR-486-5p.

Why might restricting Ago diversity be of utility? Given evidence that non-Slicing Argonautes arrest the biogenesis of mir-451 and mir-486 at intermediate stages (Figure 3A), we hypothesize that their presence essentially acts as dominant-negative factors. We tested this by co-expressing constructs for these miRNAs in the presence of different Ago constructs. We observe that elevated Ago2 enhances miR-451 maturation and clearance of miR-486-3p, whereas Ago1/3 and Ago2-CD have the opposite effect (Figure 7D). This has consequences for target repression, since coexpression of Ago1, Ago4 or Ago2-CD all inhibit the activity of mir-486 on its sensor (Figure 7E). Since miR-486 and miR-451 exhibit highly erythroid restricted co-expression (McCall et al., 2017) and uniquely require slicing biogenesis, we infer that the conserved and unique program of Argonaute gene signature reveals a critical usage of endogenous Ago2 catalysis. That is, the cell type-specific deployment of multiple atypical, Slicing-dependent miRNAs has co-evolved with a specialized environment that predominantly expresses catalytically-active Argonaute2 in the erythroid system.

Discussion

Multiple conserved roles for mammalian Ago2-Slicer in atypical erythroid miRNA biogenesis

Overall, this study advances our understanding on the role and evolutionary maintenance of Slicing in mammals. As mentioned in the introduction, while instances of mammalian substrates that can be cleaved have been described, there remain substantial gaps in linking conserved mechanisms of Ago2 cleavage to biology. Here, we extend work from our group and others on Dicer-independent, Slicer-dependent biogenesis of mir-451 (Cheloufi et al., 2010; Cifuentes et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2010), by revealing mir-486 as an unexpected Dicer-dependent, Slicer-dependent locus. These conserved, atypical miRNAs share a common expression pattern, since they represent the dominant miRNAs that are specifically up-regulated in the erythroid lineage. Knockout analyses show that both miRNAs are required for efficient erythroid homeostasis and phenocopy conditional inactivation of Ago2-Slicer function within the hematopoietic compartment. Although previous and current structure-function studies show that both mir-451 and mir-486 can be altered so as to bypass Slicing-dependent biogenesis, the strict primary sequence conservation of these loci indicates that the atypical maturation of these miRNAs is not evolutionarily malleable. Thus, the mammalian erythroid system has specifically evolved to deploy conserved, non-canonical, Slicer-dependent miRNAs, unlike essentially all other mammalian cells and tissue types.

Potentially broader implications for passenger strand cleavage for mechanism

Since mir-486 emerged within the mammalian lineage, whereas mir-451 is conserved across vertebrates (Kozomara and Griffiths-Jones, 2014), we envisage that an early mammalian ancestor built upon innovation of miR-451 biogenesis to implement dual strategies for Slicer-dependent miRNA biogenesis. This post-transcriptional mode of miRNA processing control imposes a challenge for “sorting” (Czech and Hannon, 2010), since small RNA duplexes are eligible to load into any of the available Argonaute proteins. As we have shown, the presence of non-Slicing Ago proteins is dominant negative for the biogenesis and activity of both miR-451 and miR-486. This challenge appears to have been solved in vivo by altering the Ago environment in the erythroid lineage such that Ago2 is the sole Argonaute in this setting, unlike in virtually all other tissues and cells. We take this co-evolution of Ago2 expression and dominant tissue-specific deployment of multiple Slicer-dependent miRNAs as an indication that this represents one of the critical in vivo usages of Ago2 catalysis in mammals. We note that the Ago2 expression bias is also observed in skeletal muscle, the other location of miR-486 deployment, consistent with a biological rationale to adjust the Ago environment to make more Ago2 available for miR-486 RISC.

At the same time, one wonders whether there is a broader impact of passenger cleavage on other miRNA loci. For example, certain other well-paired miRNA hairpins have been detected as being cleaved by Ago2 (Diederichs and Haber, 2007; Liu et al., 2014), although in these cases at the pre-miRNA stage. It is conceivable that miR-486 is an outlier whose biogenesis is heavily reliant upon Ago2 catalysis (by eliminating one strand), but that the strand output of other miRNA loci might be tuned by this mechanism. Indeed, widespread functional activity of both strands of miRNA duplexes has been detected (Kuchenbauer et al., 2011; Okamura et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2011), and passenger strand cleavage might be a strategy to alter miRNA duplex properties. Although prior studies of mammalian Argonaute sorting attempted to find small RNAs specifically associated with different effectors (Azuma-Mukai et al., 2008; Dueck et al., 2012), our data indicate that analysis of 5p:3p ratio differences might be more productive to find Slicer-dependent loci. One biological scenario might be that potential subtle alterations in the accumulation of many miRNAs might be associated with Ago2-CD phenotypes in certain settings.

Implications of Slicer-dependent miR-486 biogenesis for disease

Deregulation of mir-486 has been reported to be functionally involved in a variety of diseases. For example, transgenic expression of miR-486 was shown to improve a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Alexander et al., 2014), overexpression of miR-486 can induce replicative senescence in certain cell models (Kim et al., 2012), and gain of miR-486 activity was recently shown to drive certain types of myeloid leukemia (Shaham et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). Our data provide the unexpected mechanistic underpinning that all of these settings, and other settings involving deregulated miR-486, require Ago2-Slicer activity. Given that miR-486 (and miR-451) are unusually dose-sensitive to Ago2-Slicer function, as we showed even in the in vivo heterozygous situation (Figure 1B), it may be that certain disease states may prove to be amenable to manipulation of Ago2 enzymatic activity.

STAR METHODS

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Monoclonal Anti-mouse Ago2 | WAKO | Cat#018-22021 |

| Rabbit polyclonal Anti-Ago1 | MBL | Cat#RN028PW |

| Anti-beta tubulin | DSHB | AB_2315513 |

| FITC anti-mouse CD71 [R17217] | BioLegend | Cat#113805 |

| Anti-mouse TER-119 PE-Cy5 | eBioscience | Cat#15-5921-81 |

| CD45.2-A700 | Invitrogen/ebioscience | Cat#56045482 |

| CD45.1-PE-Texas Red | BD Biosciences | Cat#562452 |

| Mac1-PB | BD Biosciences | Cat#560455 |

| Gr1-APC | Invitrogen/ebioscience | Cat#17593182 |

| CD3e-PB | Invitrogen/ebioscience | Cat#48003180 |

| CD4-PE | BD Biosciences | Cat#557308 |

| CD8a-FITC | BD Biosciences | Cat#553031 |

| IgM-APC | Biolegend | Cat#406509 |

| PeCy7 B220 | BD Biosciences | Cat#552772 |

| Sca1-PB | Biolegend | Cat#122520 |

| APC Cy7 cKit | Biolegend | Cat#105826 |

| CD150 APC | Biolegend | Cat#115910 |

| CD48 PE | BD Biosciences | Cat#557485 |

| Pe-Cy7 CD16/32 | Biolegend | Cat#101318 |

| CD34 FITC | Invitrogen/ebioscience | Cat#11034185 |

| CD3e-PeCy5 | eBioscience | Cat#15-0031-83 |

| CD4-PeCy5 | eBioscience | Cat#15-0041-83 |

| CD8a-PeCy5 | eBioscience | Cat#15-0081-83 |

| Gr1-PeCy5 | eBioscience | Cat#15-5931-83 |

| B220-PeCy5 | eBioscience | Cat#15-0452-83 |

| CD19-PeCy5 | eBioscience | Cat#15-0193-83 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Phenylhydrazine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#114715-100G |

| Hydrogen peroxide solution | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#H1009-100ML |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Lipofectamine LTX | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#15338030 |

| Lipofectamine 2000 | Fisher Scientific | Cat#11668030 |

| Capillary pipettes | Drummond Scientific Company | Cat#2-000-200 |

| Surveyor Mutation Detection Kit | IDT | Cat#706020 |

| MEGAshortscript T7 transcription kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#AM1354 |

| mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 transcription kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#AM1344 |

| MEGAclear Transcription Clean-Up Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#AM1908 |

| Dynabeads protein G | Life Technologies | Cat#10004D |

| Antarctic Phosphatase | NEB | Cat#M0289S |

| ATP, [gamma-P32] | PerkinElmer | Cat#BLU502Z250UC |

| T4 PNK | NEB | Cat#M0201L |

| SequaGel UreaGel System | National Diagnostics | Cat#EC-833 |

| Quantitect Reverse Transcription Kit | Qiagen | Cat#205311 |

| SYBR select master mix | Life Technologies | Cat#4472942 |

| Dual Glo luciferase assay system | Promega | Cat#E2940 |

| Trizol | Life technologies | Cat#15596-018 |

| GeneScreen Plus membrane | PerkinElmer | Cat#NEF1017001PK |

| T4 RNA ligase 2 (1-249; K227Q) | NEB | Cat#M0351L |

| T4 RNA ligase 1 | NEB | Cat#M0204L |

| Superscript III RT kit | Invitrogen | Cat#18080-051 |

| Adenylation Kit | NEB | Cat#E2610L |

| Deposited Data | ||

| sRNA-seq libraries from mouse fetal liver | This study | GEO: GSE101849 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Ago2-catalytic dead knockin MEF | This study | N/A |

| Ago2-KO and Ago2 rescue MEF | Eric Lai lab | N/A |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: B6.Cg-Tg(Vav1-icre)A2Kio/J vav1-cre | The Jackson Laboratory | Stock No:008610 |

| Mouse: B6.129P2(129S4)-Ago2tm1.1Tara/J Ago2-floxed | The Jackson Laboratory | Stock No:016520 |

| Mouse: B6;129S6-Ago2tm3Ghan/J Ago2-CD | The Jackson Laboratory | Stock No:014150 |

| Mouse: mir-486−/−; FVB | This study | N/A |

| Mouse: mir-144/451−/− | Mitchell Weiss | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Refer to Supplementary Table 3 | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pCDNA6.2-N-terminal EmGFP-TOPO | Invitrogen | Cat#360-20 |

| pCDNA3-Myc-Ago1 | Jidong Liu | N/A |

| pCDNA3-Myc-Ago2 | Jidong Liu | N/A |

| pCDNA3-Myc-Ago3 | Jidong Liu | N/A |

| pCDNA3-Myc-Ago4 | Jidong Liu | N/A |

| pCDNA3-Myc-Ago2 CD | Jidong Liu | N/A |

| pCDNA6.2-hsa-miR-144/451 | This study | N/A |

| pCDNA6.2-mmu-miR-486 | This study | N/A |

| pCDNA6.2-bulge-mmu-miR-486 | This study | N/A |

| pCDNA6.2-hsa-miR-183 | Eric Lai lab | N/A |

| pCDNA6.2-hsa-miR-1-2 | Eric Lai lab | N/A |

| pCDNA6.2-hsa-miR-342 | Eric Lai lab | N/A |

| Catalytically activated hAgo1 plasmid | Gunter Meister | N/A |

| Catalytically activated hAgo3 plasmid | Gunter Meister | N/A |

| Catalytically activated hAgo4 plasmid | Gunter Meister | N/A |

| psiCHECK-bulge-miR-486-5p | This study | N/A |

| psiCHECK-bulge-miR-486-3p | This study | N/A |

| psiCHECK-bulge-miR-183 | This study | N/A |

| psiCHECK-bulge-miR-1-2 | Eric Lai lab | N/A |

| psiCHECK-bulge-miR-342 | Eric Lai lab | N/A |

| psiCHECK-mmu-Pten-3′UTR | This study | N/A |

| psiCHECK-mmu-Foxo1-3′UTR | This study | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| FlowJo V10.1 | FlowJo, LLC | N/A |

| Prism 6.0 | GraphPad | N/A |

| cutadapt | (Martin, 2011) | |

| edgeR/Limma Bioconductor library | (Oshlack, 2010) (Smyth, 2005) | N/A |

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Eric Lai (laie@mskcc.org).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

MOUSE MODELS

Ago2[CD] (B6;129S6-Ago2tm3Ghan/J); vav1-cre (B6.Cg-Tg(Vav1-icre)A2Kio/J); Ago2-flox (B6.129P2(129S4)-Ago2tm1.1Tara/J); mir-486−/− (FVB); mir-144/451 (BL6) mice were used for our analysis of hematopoietic phenotypes. Age matched littermates were used for control and experimental groups according to genotype. All animal studies were performed in compliance with IACUC and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center animal care regulations.

CELL LINES

Ago2-CD and control MEFs were generated from E15.5 embryos as described below in the main STAR methods text. Cell lines were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 in DME-high glucose media containing 15% FBS, 1% non-essential amino, 1% sodium pyruvate, penicillin/streptomycin, L-glutamate, and 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol. These cell lines have been authenticated via genotyping and assaying for slicer activity.

METHOD DETAILS

Generation of miRNA expression constructs

Wildtype human and mouse microRNA expression constructs were generated by PCR amplification of ~500bp amplicons from HeLa cell and MEF cell gDNA, respectively. Amplicons were cloned between two EcoRI sites in pCDNA6.2-N-terminal-EmGFP-TOPO plasmid. Mutant mir-486 expression constructs were generated by first generating two separate amplicons using a set of wildtype forward and mutant reverse primer and a set of overlapping mutant forward and wildtype reverse primer. A second PCR using the overlapping amplicons as templates was performed to generate the full length ~500bp mutant mir-486 insert. The amplicon was cloned between two EcoRI sites in pCDNA6.2-N-terminal-EmGFP TOPO. Sequence of primers are listed in Table S3.

Generation of mouse embryonic fibroblast cell lines

MEF cell lines (Ago2 wt/wt; wt/CD; CD/CD) were generated from E15.5 embryos collected from pregnant Ago2 wt/CD females resulting from cross to a Ago2 wt/CD male. Head, limbs, tail, and internal organs were removed and the resulting skin tissue was transferred to trypsin and chopped using forceps. The tissue was incubated at 4°C overnight and warmed up to 37°C and pushed through an 18G needle ~10 times. The resulting cells were plated in DME-high glucose media containing 15% FBS, 1% nonessential amino, 1% sodium pyruvate, penicillin/streptomycin, L-glutamate, and 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol. The primary MEFs were passaged 5-10 times and then transfected/immortalized with SV40 T antigen. Transfected cells were passaged at low density 5-10 times and then single cell clones were selected and expanded.

Cell culture and transfection

MEF cell lines were passaged in DME-high glucose media containing 15% FBS, 1% non-essential amino acids, 1% sodium pyruvate, penicillin/streptomycin, L-glutamate, and 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol. Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine LTX. For each well of a 6-well plate, 2.5μg of miRNA expression plasmid and Argonaute expression constructs were transfected. Cells were washed and collected 24 hours post-transfection.

Radiolabeling of RNA from Argonaute immunoprecipitates

Protein lysates were prepared from MEFs of the indicated genotypes by pipetting pelleted cells using lysis buffer containing 5% glycerol, 150mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 2mM MgOAc, 20mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). 2mM DTT and protease inhibitor were added prior to use. The cells were incubated on ice for 30 minutes with additional pipetting. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 14000 rpm at 4°C.

Ago2 was immunoprecipitated from the lysates with Dynabead conjugated Ago2 antibody (WAKO; 018-22021) and RNA was extracted from the beads by phenol-chloroform extraction after resuspending in .4M NaCl. The Ago2 associated RNA samples were 5′ dephosphorylated with Antarctic phosphatase (NEB) at 37°C for 1hr. The enzyme was inactivated by 70°C incubation for 10 min. The dephosphorylated RNA was radiolabeled by 5′ phosphorylation with gamma-ATP in presence of PNK (NEB). Labeled RNA samples were run on 20% urea polyacrylamide gels and exposed to phosphorimaging plates.

cDNA preparation and qPCR

cDNA was prepared from total RNA by DNase treatment and reverse transcription using QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen). qPCR reactions were performed using SYBR select master mix (Life Technologies). Data were normalized to Actb amplification. Primer sequences are listed in Table S3.

Cloning of bulge containing miRNA sensors and luciferase sensor assay

psiCHECK2 vector containing bulged targets for miR-486-5p, miR-486-3p, miR-183-5p, miR-342, miR-1-2, and endogenous 3′ UTRs of Pten and Foxo1, were cloned as follows (Okamura et al., 2007). Oligos with complementary sequences to the miRNA were designed with SalI and XhoI sites and annealed. For multiple site-containing sensors, the annealed oligos were incubated in a simultaneous ligation and restriction digest reaction containing SalI and XhoI, T4 DNA ligase buffer, T4 DNA ligase, allowing for correct orientation ligations of the tandem site sensors. The oligomers containing the appropriate number of target sites were agarose gel purified and cloned into SalI/XhoI digested psiCHECK vector. MEFs were transfected in 96 well plates with 160ng miRNA plasmid and 40ng sensor plasmid using Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen). Luciferase levels were measured using Dual Glo luciferase assay system (Promega) 24 hours after transfection. Oligo sequences are listed in Table S3.

Western blotting

Protein lysates were prepared from MEFs with lysis buffer containing 5% glycerol, 150mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 2mM MgOAc, 20mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Mouse tissues were first chopped using forceps before lysis. 10-15 μg of proteins lysates were loaded using 3× SDS sample buffer (NEB) containing DTT. Blots were incubated with following antibody dilutions. 1:1000 anti-mAgo1 (MBL; RN028PW); 1:1000 anti-mAgo2 (WAKO; 018-22021); 1:1000 ß-tubulin (E7; DSHB).

Small RNA Northern blotting

Total RNA was prepared using Trizol. 10μg RNA was run on 12-20% urea polyacrylamide gel and transferred to GeneScreen Plus (Perkin Elmer) membrane, UV-crosslinked, and baked at 80°C for 30 minutes and hybridized with gamma-P32 labeled probes. Probe sequences are listed in Table S3.

In vitro cleavage assays

Duplex miR-486 substrates were prepared by either 5′ radiolabeling (gamma-32P ATP) or cold-ATP labeling of either synthetic miR-486-5p or -3p RNA oligonucleotides. Labeled RNA oligos were denaturing PAGE purified, eluted, and ethanol precipitated. The phosphorylated 5p and 3p RNA oligos were annealed and the duplex species was native PAGE purified, eluted, and ethanol precipitated.

Cell lysates used for in vitro cleavage reactions were prepared from MEFs (either wildtype or Ago2[CD/CD] as noted in text) transfected with the appropriate Ago#-expression constructs. Lysate was mixed with equal volume of 2× reaction mix, consisting of 133.4 mM KCl, 13.4 mM MgCl2, 16.61 mM DTT, 3.4mM ATP, 40U RNase OUT, and radiolabeled RNA duplex. Reactions were performed at 25°C and stopped on ice with buffer containing 0.4M NaCl and 10mM EDTA. Reaction products were proteinase K treated, phenol/chloroform extracted, and ethanol precipitated. Products were run on 12-20% denaturing PAGE and visualized by phosphorimaging.

AGO-IP small RNA library preparation

E15.5 fetal livers were collected and lysed in NP-40 containing lysis buffer (above). Ago2 was immunoprecipitated using anti-Ago2 antibody (WAKO) after conjugation to Dynabeads Protein G. After incubation at 4°C with rotation for 2 hours, beads were washed and the Ago2 associated RNA was collected with phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. A fraction of the input lysate and immunoprecipitated beads were saved for western blotting.

Small RNA libraries were prepared from RNA collected from Ago2-IP as follows (Lee and Yi, 2014). 3′ linker was adenylated in a reaction containing 200 pmol 3′ linker oligo, 4μL 10× 5′ DNA adenylation buffer, 4μL 1mM ATP, 1μL Mth RNA ligase, and water to 40μL final volume. Adenylation was performed at 65°C for 1 hour and terminated at 85°C for 5 minutes. Precipitated, washed, and resuspended 3′ linker was used in 3′ ligation reaction containing 1 μL 10× RNA ligase buffer, 2μL adenylated 3′ linker, 1 μL RNase inhibitor, Ago2-immunoprecipitated RNA, 1 μL T4 RNA ligase 2 (1-249 K227Q), 2μL 50% PEG8000, water to final volume of 10 μL. Ligation reactions were performed at 16C for 4 hours. The 3′ ligation products were 15% urea-PAGE purified. After elution of the RNA from gel slices with overnight incubation with shaking in .4M NaCl, the 3′ linker ligated RNA was precipitated and washed and the pelleted product was used for 5′ linker ligation by adding 0.5μL 10× RNA ligase buffer, 0.5μL ATP (10mM), 0.5μL 5′ linker oligo, 2μL 50% PEG8000, and water to 4μL final volume. The reaction was pipette mixed and incubated at 37°C for 3-5 minutes to re-solubilize before incubating in a final reaction mix containing the addition of 0.5μL RNase inhibitor and 0.5μL T4 RNA ligase 1 at 37°C for 4 hours. cDNA libraries were prepared from the ligation products in RT reactions via addition of 2μL 5× RT buffer, 0.75μL 100mM DTT, 1μL Illumina RT primer (1μM), and 0.5μL dNTPs (10mM) directly to the 5′ ligation reaction mix. The RT mix was pipette mixed and incubated at 65°C for 5 min and cooled to room temperature, placed on ice, and 0.5μL of superscript III RT enzyme and 0.5μL RNase OUT were added. RT reaction was carried out at 50°C for 1 hour. cDNA libraries were amplified in reactions containing forward and illumina index reverse primers. Oligo sequences and reagents used for library preparation are provided in table S3 and Key Resources Table, respectively.

Bone marrow transplantation

Bone marrow of Ago2[wt/fl]; vav1-cre or Ago2[CD/fl]; vav1-cre mice were processed and one million cells were transplanted into CD45.1 mice that were lethally irradiated with 900 rads. Two donors from each genotype were used and each donor was transplanted into five mice. Transplanted mice were bled at five, ten, sixteen and twenty weeks post transplant whereas aspirates were performed at eight, twelve, and twenty weeks post transplant.

Flow cytometry

Peripheral blood, bone marrow and spleen cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells were immunophenotyped with the following antibodies for the different lineages: CD45.2, CD45.1, Mac1, Gr1, CD71, Ter119, CD3, CD4, CD8, IgM and B220. For stem cell analyses, bone marrow cells were stained with the following antibodies: lineage (Gr1, B220, CD3a, CD4, CD8 and Ter119), Sca1, c-Kit, CD150, CD48, CD16/32 and CD34. Stained cells were analyzed using the BD FACS Fortessa instrument and FlowJo software.

Complete blood count

Peripheral blood was collected from adult mice under anesthesia via retro-orbital sampling using capillary pipettes. Peripheral blood was processed through a hemavet for RBC and hematocrit readings.

Phenylhydrazine treatment

A 4 mg/mL solution of PHZ (Sigma #114715) was prepared in PBS and filter sterilized. The solution was administered by intraperitoneal injection using a 27G needle at a dosage of 48 mg/kg. The mice were injected once a day for two consecutive days and monitored.

Peroxide treatment of peripheral blood

Peripheral blood collected from adult mice were treated at 37°C for 2 hrs in PBS containing 2.15mM hydrogen peroxide and 20mM glucose. Cells were then incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature with 6.45mM hydrogen peroxide, washed with PBS, and stained with CD71 and Ter119 antibodies and the red blood cell and immature reticulocyte contents were monitored by FACS analysis.

Mouse lines and crossing schemes

Ago2 catalytic dead [CD] heterozygous mice derived from cryopreserved sperm, Ago2[fl/fl], and vav1-cre mice were obtained from JAX. Ago2[CD/fl]; vav1-cre conditional mutant mice were generated by first crossing Ago2[CD/+] and vav1-cre mice to obtain Ago2[CD/+]; vav1-cre mice. These mice were crossed to Ago2[fl/fl] mice to obtain the conditional mutants.

mir-144/451 knockout mice (Yu et al., 2010) were kindly provided by Mitchell Weiss. For simplicity, we refer to them as mir-451-KO mice since it has been shown that miR-144 does not substantially contribute to erythroid phenotypes in this model (Rasmussen et al., 2010). We generated mir-451/486 double knockout mutants by first crossing mir-451−/− to mir-486−/− mice. The resulting double heterozygous mice were interbred to obtain the appropriate combinations of alleles (including the double knockouts).

CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis to generate mir-486-KO mice

sgRNAs were generated to target the miR-486 mature sequence using CRISPR Design software (http://crispr.mit.edu/) and tested by transfection of a vector co-expressing Cas9 and a sgRNA into 3T3 cells by Lipofectamine® 2000. Successfully edited mir-486 loci were identified using the Surveyor® Mutation Detection kit (PCR primers, F: TCAGAAAGCACGCCAGACAT, R: TCCCATTGAGGCCCTGGATA). A selected sgRNA (guide sequence: GAGCACAGTGAAGGACCTCG) was in vitro transcribed using the Ambion MEGAshortscript™ T7 Transcription Kit and Cas9 mRNA was generated using the Ambion mMESSAGE mMACHINE® T7 Transcription Kit. RNA was isolated using the MEGAclear™ Transcription Clean-Up Kit and diluted as a pool of RNA at a final concentration of 20 ng/μL of sgRNA and 50 ng/μL of Cas9 mRNA. FVB zygotes were injected at UCSF’s LARC Rederivation Core. 55 embryos were collected, and of these, 35 injected zygotes were transplanted into pseudo-pregnant female. Pups were screened using the Surveyor® Mutation Detection kit followed by TOPO cloning and sequencing.

Small RNA-seq analysis

We cloned Ago2 IP small RNA libraries from fetal liver of wildtype and Ago2-CD/CD mice, in two biological replicates. The data are under submission to NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). After removing 5′ and 3′ adaptor sequences with cutadapt (Martin, 2011), we mapped small RNA-seq reads from these datasets to UCSC Mus musculus (mm9) genome assembly using Bowtie. Unmapped reads were iteratively trimmed one nucleotide each iteration retaining a read length of ≥17nt, and then mapped to the genome using Bowtie with no mismatches, up to 30 iterations. The reads were required to match to the microRNA mature sequences of both canonical miRNAs and mirtrons (Wen et al., 2015) with at least 15 nt overlap, and within 2 nt of the 5′ end. The miRNAs with at least 50 mapped reads were included. We normalized small RNA-seq by total microRNA counts in each library by the trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) normalization method in the edgeR/Limma Bioconductor library (Oshlack et al., 2010). We used the voom method of Limma (Smyth, 2005) to correct for the Poisson noise due to the discrete counts of small RNA-seq.

We analyzed Ago-family expression data using a panel of tissues and hematopoietic samples from publicly available RNA-seq datasets (Mouse: GSE41637 and GSE60101; Human: GSE30611 and GSE74246). To provide uniform comparisons, we processed the data from the raw files, and Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (FPKM) were calculated to give gene expression per gene.

Analysis of microRNA features

To investigate microRNA sequence properties, we partitioned mouse microRNA sequences into regions of seed, mature, star, loop, lower stem, upper stem, as well as entire precursors. The minimum free energy (MFE), pairing score (3 for G:C, 2 for A:U, 1 for G:U), number of G:C or A:U pairing, number of continuous paring, and number of unpaired bases were calculated for each partition.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

For sensor assays presented in Figure 2C–E, Figure 4E, and Figure 7E, unpaired Student’s t-test was used to evaluate significance of comparisons between repression activity of miRNAs against their sensors in different genetic backgrounds. The error bars represent standard deviation and t-test p-values are denoted above bars in the figures above. For comparisons of flow cytometry and blood count values depicted in Figure 6 and Supplementary Figures 3–7, unpaired student t-test was used to compare the values obtained from mice in control and experimental genotype groups, with each point in the plot representing an individual mouse. Error bars represent the standard deviation of values among the individual mice in each group. t-test p values are marked according to following: * <.05 **<.01 ***<.001 ****<.0001.

For quantification of Northern blot signals represented in Figure 4B, mean ratios of either the pre-mir-451/mature miR-451 or miR-486-3p/5p from triplicate experiments were plotted and upaired Student’s t-test was performed to evaluate significance in accumulation patterns of different miRNA species under the denoted experimental conditions.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

The sRNA-sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in GEO under GSE101849.

Conserved, erythroid miR-486 requires slicing of its passenger strand by Ago2.

miR-486/451 are the dominant slicing dependent miRNAs in the hematopoietic compartment.

Their loss together explains the erythroid phenotype of Ago2 slicing deficient mice.

Erythroid tissue has conserved signature of Ago2-only expression in mouse and human.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Read counts and other values for Ago2-IP small RNA libraries, Related to Figure 4.

Table S2. Values for miRNA levels and comparisons in Ago2-IP small RNA libraries, Related to Figure 4.

Table S3. List of oligonucleotides, Related to STAR Methods section.

Acknowledgments

mir-144/451-KO mice were kindly provided by Mitchell Weiss, Ago2-fl mice were provided by Alexander Tarakhovsky (Rockefeller University), Ago2-CD knockin mice originally generated by Gregory Hannon were obtained as cryopreserved sperm from Jackson Labs. vav1-cre mice were also from Jackson Labs. Catalytically reprogrammed Ago plasmids were kindly provided by Gunter Meister. Work in the Lai lab was supported by the Susan and Peter Solomon Divisional Genomics Program, NIH grants R01-GM083300 and R01-HL135564, and by the MSK Core Grant P30-CA008748.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions

DJ performed the biochemical and molecular tests, cell culture, mouse genetics, and hematopoietic work described in the study. JSY made initial observations on Slicer dependence of miR-486. SMP, TC and AC helped perform hematopoietic analyses. DJF and MTM made mir-486-KO mice. JW conducted bioinformatic analysis. ECL and MK designed the overall study and evaluated data. ECL and DJ wrote the manuscript with input from all coauthors.

Declaration of Interests

There are no competing interests.

Jee et al. reveal that a major conserved rationale for mammalian Argonaute2 slicing is for the combined maturation of miR-486 and miR-451, miRNAs necessary for erythroid development. Their loss phenocopies the erythroid defects of slicing deficient mice, and this slicing requirement explains the unique Ago2-only expression pattern found in erythroid tissue.

References

- Alexander MS, Casar JC, Motohashi N, Myers JA, Eisenberg I, Gonzalez RT, Estrella EA, Kang PB, Kawahara G, Kunkel LM. Regulation of DMD pathology by an ankyrin-encoded miRNA. Skelet Muscle. 2011;1:27. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-1-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander MS, Casar JC, Motohashi N, Vieira NM, Eisenberg I, Marshall JL, Gasperini MJ, Lek A, Myers JA, Estrella EA, et al. MicroRNA-486-dependent modulation of DOCK3/PTEN/AKT signaling pathways improves muscular dystrophy-associated symptoms. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124:2651–2667. doi: 10.1172/JCI73579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma-Mukai A, Oguri H, Mituyama T, Qian ZR, Asai K, Siomi H, Siomi MC. Characterization of endogenous human Argonautes and their miRNA partners in RNA silencing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:7964–7969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800334105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi E, Bulgarelli J, Ruberti S, Rontauroli S, Sacchi G, Norfo R, Pennucci V, Zini R, Salati S, Prudente Z, et al. MYB controls erythroid versus megakaryocyte lineage fate decision through the miR-486-3p-mediated downregulation of MAF. Cell death and differentiation. 2015;22:1906–1921. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheloufi S, Dos Santos CO, Chong MM, Hannon GJ. A dicer-independent miRNA biogenesis pathway that requires Ago catalysis. Nature. 2010;465:584–589. doi: 10.1038/nature09092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes D, Xue H, Taylor DW, Patnode H, Mishima Y, Cheloufi S, Ma E, Mane S, Hannon GJ, Lawson N, et al. A Novel miRNA Processing Pathway Independent of Dicer Requires Argonaute2 Catalytic Activity. Science. 2010;328:1694–1698. doi: 10.1126/science.1190809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen BR, Cherry S, tenOever BR. Is RNA interference a physiologically relevant innate antiviral immune response in mammals? Cell host & microbe. 2013;14:374–378. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech B, Hannon GJ. Small RNA sorting: matchmaking for Argonautes. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2010;12:19–31. doi: 10.1038/nrg2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer J, Williams A, Skavdis G, Harker N, Coles M, Tolaini M, Norton T, Williams K, Roderick K, Potocnik AJ, et al. Transgenic mice with hematopoietic and lymphoid specific expression of Cre. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:314–325. doi: 10.1002/immu.200310005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederichs S, Haber DA. Dual Role for Argonautes in MicroRNA Processing and Posttranscriptional Regulation of MicroRNA Expression. Cell. 2007;131:1097–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding SW, Voinnet O. Antiviral RNA silencing in mammals: no news is not good news. Cell reports. 2014;9:795–797. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dueck A, Ziegler C, Eichner A, Berezikov E, Meister G. microRNAs associated with the different human Argonaute proteins. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:9850–9862. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faehnle CR, Elkayam E, Haase AD, Hannon GJ, Joshua-Tor L. The making of a slicer: activation of human Argonaute-1. Cell reports. 2013;3:1901–1909. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemr M, Malik R, Franke V, Nejepinska J, Sedlacek R, Vlahovicek K, Svoboda P. A retrotransposon-driven dicer isoform directs endogenous small interfering RNA production in mouse oocytes. Cell. 2013;155:807–816. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauptmann J, Dueck A, Harlander S, Pfaff J, Merkl R, Meister G. Turning catalytically inactive human Argonaute proteins into active slicer enzymes. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2013;20:814–817. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvvuna PK, Khandelia P, Lee LM, Makeyev EV. Argonaute identity defines the length of mature mammalian microRNAs. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:6808–6820. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karginov FV, Cheloufi S, Chong MM, Stark A, Smith AD, Hannon GJ. Diverse endonucleolytic cleavage sites in the mammalian transcriptome depend upon microRNAs, Drosha, and additional nucleases. Molecular cell. 2010;38:781–788. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamata T, Seitz H, Tomari Y. Structural determinants of miRNAs for RISC loading and slicer-independent unwinding. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2009;16:953–960. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Hwang SH, Lee SY, Shin KK, Cho HH, Bae YC, Jung JS. miR-486-5p induces replicative senescence of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells and its expression is controlled by high glucose. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:1749–1760. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YK, Kim B, Kim VN. Re-evaluation of the roles of DROSHA, Export in 5, and DICER in microRNA biogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016;113:E1881–1889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602532113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: annotating high confidence microRNAs using deep sequencing data. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42:D68–73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchenbauer F, Mah SM, Heuser M, McPherson A, Ruschmann J, Rouhi A, Berg T, Bullinger L, Argiropoulos B, Morin RD, et al. Comprehensive analysis of mammalian miRNA* species and their role in myeloid cells. Blood. 2011;118:3350–3358. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-312454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JE, Yi R. Highly efficient ligation of small RNA molecules for microRNA quantitation by high-throughput sequencing. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2014:e52095. doi: 10.3791/52095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuschner PJ, Ameres SL, Kueng S, Martinez J. Cleavage of the siRNA passenger strand during RISC assembly in human cells. EMBO reports. 2006;7:314–320. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Carmell MA, Rivas FV, Marsden CG, Thomson JM, Song JJ, Hammond SM, Joshua-Tor L, Hannon GJ. Argonaute2 is the catalytic engine of mammalian RNAi. Science. 2004;305:1437–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.1102513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Zheng Q, Vrettos N, Maragkakis M, Alexiou P, Gregory BD, Mourelatos Z. A MicroRNA precursor surveillance system in quality control of MicroRNA synthesis. Molecular cell. 2014;55:868–879. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lulli V, Romania P, Morsilli O, Cianciulli P, Gabbianelli M, Testa U, Giuliani A, Marziali G. MicroRNA-486-3p regulates gamma-globin expression in human erythroid cells by directly modulating BCL11A. PloS one. 2013;8:e60436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Flemr M, Stein P, Berninger P, Malik R, Zavolan M, Svoboda P, Schultz RM. MicroRNA activity is suppressed in mouse oocytes. Curr Biol. 2010;20:265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. Embnet journal. 2011;7:10–12. [Google Scholar]