Abstract

Purpose

The rapidly increasing number of older adults cycling through local criminal justice systems (jails, probation and parole) suggests a need for greater collaboration among a diverse group of local stakeholders including professionals from healthcare delivery, public health, and criminal justice and directly affected individuals, their families, and advocates. In response, we developed a framework that local communities can use to understand and begin to address the needs of criminal justice-involved older adults.

Approach

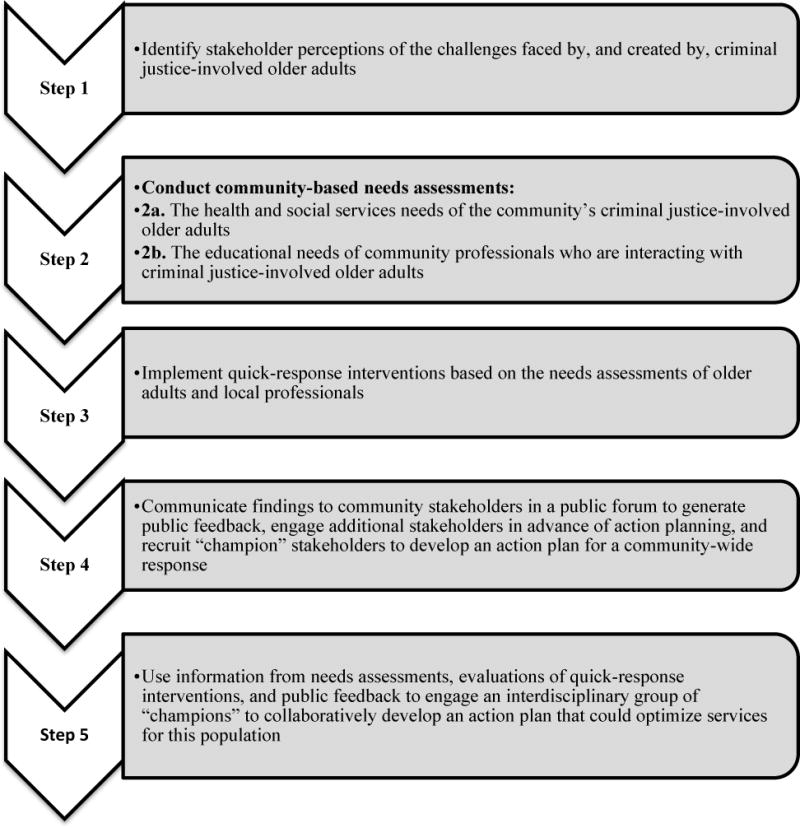

The framework included: (1) solicit input from community stakeholders to identify pressing challenges facing criminal justice-involved older adults, (2) conduct needs assessments of criminal justice-involved older adults and professionals working with them; (3) implement quick-response interventions based on needs assessments; (4) share findings with community stakeholders and generate public feedback; (5) engage interdisciplinary group to develop an action plan to optimize services.

Findings

A 5-step framework for creating an interdisciplinary community response is an effective approach to action planning and broad stakeholder engagement on behalf of older adults cycling through the criminal justice system.

Value

This study proposes the COJENT (Criminal Justice Involved Older Adults in Need of Treatment) Initiative Framework for establishing an interdisciplinary community response to the growing population of medically and socially vulnerable criminal justice-involved older adults.

Background

The number of criminal justice-involved older adults (awaiting trial, on community-based probation or parole, or serving prison sentences) is growing rapidly in many nations (Fazel and Baillargeon, 2011, Williams et al., 2014a, Maschi et al., 2013). Accordingly, the number of criminal justice-involved older adults in need of health and social services – both in correctional facilities and in the community - is also on the rise (Aday, 2003, Williams et al., 2012a). Criminal justice-involved individuals are typically considered “older adults” in their 50s due to a disproportionate burden of chronic illness, disability, and geriatric conditions at early ages (Williams et al., 2012b, Ahalt et al., 2013). In the United States this population is growing rapidly. Over 500,000 American older adults are arrested annually, including more than one percent of all U.S. adults aged 55-64 (Snyder, 2012). With over 150,000 sentenced prisoners age 55 or older – and an additional 450,000 middle-aged prisoners (ages 40 to 55) – the prison aging trend is expected to continue. Because the vast majority of incarcerated individuals in the U.S. are eventually released (Freeman, 2003), the number of community-dwelling older adults with current or former criminal justice involvement will also grow. Yet relatively little is known about the needs of these medically and socially complex older adults (Ahalt et al., 2012, Ahalt et al., 2015). In response, we designed a 5-Step Initiative to develop the evidence needed for a community-wide, interdisciplinary action plan to identify and meet this population’s needs.

While the medical literature about criminal justice-involved older adults in the U.S. is sparse, research has shown many experience disproportionate rates of co-occurring behavioral, medical and mental health conditions (Barry et al., 2016, Bolano et al., 2016, Chodos et al., 2014). As a result, criminal justice, health, and social service professionals interact with these individuals on a frequent basis (Brown et al., 2014, Soones et al., 2014). Yet despite their complex needs, few of the intensive interdisciplinary services shown to improve outcomes for other criminal justice-involved populations (e.g., those living with HIV and veterans) have been developed and targeted for criminal justice-involved older adults. For example, an older adult with age-related cognitive impairment recently released from prison may require care for multiple chronic health conditions while also facing the challenges of finding stable housing and abstaining from drug use. A subsequent violation of this person’s parole may reflect more on his age-related cognitive impairment and might be avoided through more support. Without integrated medical and social services, this individual risks re-incarceration for medical rather than criminal behavior. An ongoing lack of integrated community-based policy and services geared towards the needs of such older adults could result in multiple adverse community outcomes, including increased homelessness, crowded urgent care clinics, and increased interactions of this population with law enforcement.

Therefore, a coordinated, interdisciplinary, and community-wide response is needed to meet the complex challenges that criminal justice-involved older adults pose to many public agencies and non-profit organizations (e.g., probation, departments of public health, behavioral health programs, the courts, and social services agencies). The most important first step in that effort is to identify this population’s challenges, the resources that are available to meet these challenges in the community, and the gaps in knowledge and services that function as barriers to effectively meeting this population’s needs. The goal of this project was to develop a replicable, community-based framework to determine the needs of criminal justice-involved older adults, assess the community’s relevant resources, identify knowledge and resource gaps, and to use this information to develop a stakeholder-driven action plan to address their needs.

The 5-Step COJENT Framework: Approach and Results

The “Criminal Justice-Involved Older Adults in Need of Treatment” (COJENT) Initiative was established to develop an evidence-based, community-wide, interdisciplinary action plan to identify and address the needs of the growing number of criminal justice-involved older adults in our local community (San Francisco, California). This manuscript describes the 5-step COJENT Framework that resulted.

The COJENT Framework draws on three approaches to health care and health system research: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, Health Impact Assessment (HIA) and the Sequential Intercept Mapping (SIM) Model for Criminal Justice Services). Patient-Centered Outcomes Research emphasizes placing patients, providers, and the community at the center of research, in the development of evidence-based programming to improve healthcare delivery, and to generate practical solutions that account for provider and community-identified obstacles to optimal health outcomes (Selby et al., 2012). The HIA model is used to identify and respond to health inequities by understanding the potential health risks and benefits involved in policy change. It does so through concurrent steps including screening and scoping existing evidence and stakeholder opinions, appraising policies and procedures, obtaining local data, and weighing these factors alongside potential health impacts to create recommendations and influence decisions (Mindell et al., 2003). Finally, the SIM model, originally developed to address behavioral health gaps in criminal justice systems, identifies points, or intercepts, along the course of criminal justice involvement at which an intervention could be made to prevent further unnecessary criminal justice involvement. From police contact through court adjudication, bail hearings, jail intake and community reentry, the SIM model emphasizes opportunities at every criminal justice phase to engage vulnerable populations in treatment and support (Munetz and Griffin, 2006).

Applying Patient-Centered Outcomes Research and the HIA and SIM models, we developed the 5-step COJENT Framework to generate the knowledge needed for a consensus-based, feasible action plan that the community could use to prioritize and transform policies and practices to meet this population’s health and social service needs, Figure 1. The COJENT Framework’s 5 steps include: (1) identify stakeholder perceptions of the challenges faced by, and created by, criminal justice-involved older adults; (2) conduct community-based needs assessments of: (2a) the health and social services needs of the community’s criminal justice-involved older adults; (2b) the educational needs of community professionals who are interacting with criminal justice-involved older adults; (3) implement quick-response interventions based on the needs assessments of older adults and local professionals; (4) communicate findings to community stakeholders in a public forum to generate public feedback, engage additional stakeholders in advance of action planning, and recruit “champion” stakeholders to develop an action plan for a community-wide response; and (5) use information from needs assessments, evaluations of quick-response interventions, and public feedback to engage an interdisciplinary group of “champions” to collaboratively develop an action plan to optimize services for criminal justice-involved older adults.

Figure 1.

The 5-Step COJENT Initiative Framework. The COJENT Initiative Frameworka is used to generate the knowledge needed to develop a community-driven, consensus action plan that can be used to prioritize and transform policies and practices to meet the health and social service needs of criminal justice-involved older adults

aThe COJENT Initiative Framework incorporates elements of Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, Health Impact Assessment, and Sequential Intercept Mapping

Step 1: Identify stakeholder perceptions of the challenges faced by, and created by, criminal justice-involved older adults

Approach

Using Patient-Centered Outcomes Research (identify patient-oriented health care solutions and pursue stakeholder-driven implementation science), we engaged stakeholder and community input throughout the COJENT Initiative. To launch the Initiative, we invited local and national experts in correctional health, geriatrics, and palliative medicine as well as key stakeholders from local social services agencies for older adults to participate in a roundtable meeting to discuss the known challenges faced by criminal justice-involved older adults, the gaps in knowledge about this population’s health and social service needs and the available community services that could be mobilized or developed to meet their needs. To ensure that affected communities were included in the discussion, we identified a local non-profit organization for criminal justice-involved older adults, “The Senior Ex-Offenders Program” (Bayview Senior Services Senior Ex-Offender Program [online resource], 2016) and invited leadership, staff, and clients to participate in the meeting.

Results

The 26 roundtable participants included experts in correctional health, public defenders and district attorneys, leaders from community corrections and social service agencies, formerly incarcerated individuals, legal/criminal justice experts, and academic geriatricians. Through consensus, this interdisciplinary group identified six priority areas for policy and program reform to better characterize and address the challenges older adults face while navigating the local criminal justice system, Table 1. These recommendations then shaped the research team’s approach to the needs assessments conducted in Step 2 by informing the development of questionnaires that then focused on the priority areas that roundtable participants identified as most important to the community.

Table 1.

Roundtable recommendations to better understand the challenges faced by criminal justice-involved older adults, their health and social service needs, and the community services needed to better meet their needs (Step 1)

| Consensus Recommendations Identified by Interdisciplinary Roundtable Experts |

|---|

| 1. Collect age-stratified data to assess outcomes |

| 2. Improve access to alternatives to incarceration |

| 3. Develop tools to identify at-risk older adults on arrest |

| 4. Expand self-care and peer mentoring for incarcerated older adults |

| 5. Enable transitions of healthcare from jail/prison to community |

| 6. Expand training in geriatrics for criminal justice professionals |

Step 2a. Conduct community-based needs assessments: The health and social services needs of the community’s criminal justice-involved older adults

Approach

Addressing the health and health-related needs of criminal justice-involved older adults requires accurate data describing those needs. While some information can be surmised from the few studies published about this population, local interventions benefit from in-depth knowledge about the local population. For example, while the risk of cognitive impairment in this population should be included in action plans in any community, the burden of other medical and social vulnerabilities (e.g., drug use, homelessness, and specific chronic diseases such as HIV or Hepatitis C) may vary depending on the prevalence in the local environment, available community resources, and the community’s aging population profile. Therefore, Step 2 of the COJENT Initiative was to develop an evidence base around the health and social services needs of older adults cycling through the local criminal justice system.

We partnered with the county jail’s health services unit (which is part of the county’s department of public health) to enroll two cohorts of older adults in jail who were age 55 or older to determine their health and social service needs. The first cross-sectional study included 250 participants. The second longitudinal study enrolled 125 participants in jail and followed them for 6 months to assess changes in health and health care utilization as participants entered, exited, and in some cases re-entered jail. These epidemiologic studies used methods optimized for conducting clinical research with vulnerable populations, including questionnaires written at a 5th grade reading level, culturally appropriate and trained research staff, and a teach-to-goal method for obtaining consent with vulnerable populations (Sudore et al., 2006).

Participants self-reported their sociodemographics (including race, educational attainment, unstable housing/homelessness, income, and history of criminal justice involvement), chronic health conditions, geriatric conditions (e.g. functional impairment, recent falls, abnormal cognitive screening and incontinence), physical symptoms, social vulnerabilities (e.g. loneliness, social isolation), diagnoses of serious mental illness, symptoms of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder, and recent health services utilization. Participants’ jail medical records were reviewed for medical conditions to supplement data for those who may not know their diagnoses. Problem alcohol use and substance use disorders were assessed using validated screening tools. An in-person questionnaire was used to ascertain participants’ concerns about future health care access and safety in jail and the community. The Human Research Protection Program at the University of California, San Francisco, approved these studies. Detailed methodology for these studies is published elsewhere (Bolano et al., 2016, Chodos et al., 2014, Williams et al., 2014b).

Results

Participants reported extremely low income (>80% reported <$15,000 annual income), minority race/ethnicity, and low educational attainment (approximately 50% reported < a high school education). The population also experienced a high burden of multiple chronic conditions (e.g., hypertention, depression, Hepatitis C), geriatric conditions (e.g. functional impairment, incontinence, a recent fall), behavioral health risk factors (e.g. homelessness, food insecurity, substance use disorders), and complex symptomatology (including pain, other physical symptoms, and existential suffering). Participants in the longitudinal cohort study reported high rates of emergency department use (>40%) and repeat arrest (>30%) in the 6 months following their release from jail (Humphreys et al., 2015). These health services utilization events were strongly associated with geriatric conditions such as functional impairment and recent falls. Detailed study results have been published elsewhere (Bolano et al., 2016, Chodos et al., 2014, Williams et al., 2014b).

Step 2b. Conduct community-based needs assessments: The educational needs of community professionals who are interacting with criminal justice-involved older adults

Approach

Contemporaneously, we conducted a needs assessment of a diverse group of criminal justice professionals to understand their knowledge gaps and educational needs in aging-related health. Participants included legal professionals (public defenders and district attorneys, legal advocates, judges, and pre-trail diversion case managers); police officers; correctional officers; and jail-based clinicians. Participants completed questionnaires about their work experience, professional training in aging, attitudes towards older adults, and knowledge of aging and aging-related health. A subgroup from each professional group participated in semi-structured, in-depth qualitative interviews that assessed barriers to effective communication with older clients, system-level barriers to the appropriate provision of services to older adults, perceived need for further training in this area, and suggestions for how to address gaps in service delivery. Detailed methodology for these studies has been previously published (Brown et al., 2014, Soones et al., 2014, Sheffrin et al., 2016).

Results

Needs assessments revealed that most criminal justice professionals (outside of the medical professions) had little to no professional training in aging or aging-related health and the majority felt that training in this area would be important or very important for their work. Participants cited critical knowledge gaps including how dementia, delirium or depression might affect older adults’ behaviors that may result in criminal justice involvement and in older adults’ ability to follow or understand instructions once in the criminal justice system. Professionals also reported a critical knowledge gap about the health and social services available to older adults in the community. These findings resulted in the identification of four knowledge gap domains: knowledge about general aging and health; ability to identify and respond to cognitive impairment; ability to recognize and respond to older adults whose personal safety is at risk; and how to leverage existing community resources for older adults who are returning to the community from jail or prison or for those assigned to community supervision (probation) (Sheffrin et al., 2016, Brown et al., 2014, Soones et al., 2014).

Step 3. Implement quick-response interventions based on the needs assessments of older adults and local professionals

Approach

Because stakeholders identified professional education as a critical priority, we developed a brief geriatrics training for criminal justice professionals and a 2-day “geriatrics in correctional settings” training for jail-based clinicians. Both trainings were informed by findings from the needs assessments completed in Step 2.

Results

We partnered with the San Francisco Police Department to incorporate a 2-hour training for police officers into their 40-hour intensive Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) course, through which we trained approximately 500 officers over a 4-year period. We delivered the 2-hour training to approximately 200 other non-health criminal justice professionals in the community, including lawyers, judges, probation officers and Sheriff’s deputies (law enforcement officers assigned to the local jail). We provided the 2-day clinical training to 30 local correctional health staff. All groups rated the trainings highly and reported a high likelihood that they would apply the new knowledge to their work (Sheffrin et al., 2016).

Step 4. Communicate findings to community stakeholders in a public forum to generate public feedback, engage additional stakeholders in advance of action planning, and recruit “champion” stakeholders to develop an action plan for a community-wide response

Approach

Three years into the COJENT Initiative, we collaborated with our local Sheriff’s Department, Jail Health Services, and the Senior Ex-Offenders Program to host a public meeting about the community’s growing population of criminal justice-involved older adults and to share the findings and results from our program to date. The meeting’s aim was to publically disseminate findings from the project, engage a broader public in meeting the challenge of providing adequate services to this population, and recruit “champions” who would participate in the development of a model action plan to achieve those goals (in Step 5). To recruit local community leaders to this public meeting, we asked project stakeholders to invite clients and community members interested in participating in an effort to address the needs of older adults in our local criminal justice system.

The public meeting introduced the topic of aging in the criminal justice system to the local community, including a panel discussion with key stakeholders from the medical community, Jail Medical and Behavioral Health Services, the Senior-Ex Offenders Program, and local law enforcement. Our team presented findings from the needs assessments conducted with criminal justice-involved older adults and community-based professionals (in Step 2).

Results

Approximately 150 community members and professionals attended the meeting, including representatives from each of the program’s core constituencies and stakeholders who had not been previously engaged (e.g. faith communities, homeless shelters). Of the attendees, 65 indicated that they would like to be actively involved in creating an Action Plan (Step 5).

Step 5. Use information from needs assessments, evaluations of quick-response interventions, and public feedback to engage an interdisciplinary group of “champions” to collaboratively develop an action plan that could optimize services for this population

Approach

In the COJENT Initiative’s last step, we convened a 2-day working group meeting with the goal of creating an Action Plan to improve the health, social, and criminal justice outcomes of older adults in our community. Participants from among key stakeholders participating in the Initiative’s launch meeting (in Step 1) and volunteers at the public meeting (in Step 4) were selected to ensure a balance of disciplines and local constituencies, including older adults who had been involved in the criminal justice system. These participants included the UCSF Department of Medicine, Saint Francis Memorial Hospital, HealthRight 360, the Curry Center, Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, and San Francisco’s Veterans Affairs medical center, Sheriff’s Department, Public Defender’s Office, District Attorney’s Office, and Jail Health Services.

Over the course of the working group meeting, participants engaged in a Sequential Intercept Mapping (SIM) exercise (Munetz and Griffin, 2006) to understand the local landscape for criminal justice-involved older adults in our community. Using knowledge gathered from Steps 1-4 in addition to their own expert knowledge, participants then identified community resources for this population and resource gaps and suggested ways to expand and improve services, with particular attention to cross-agency coordination.

Results

The working group meeting generated a description of community resources that could be immediately leveraged to improve outcomes for criminal justice-involved older adults, including resource availability and access challenges and broken or missing services at each of the five SIM model intercepts, or points along the course of criminal justice involvement: (1) law enforcement and emergency services, (2) initial detention, (3) jails and courts, (4) reentry, and (5) community corrections. This exercise led to the development of actionable items and strategies for local implementation. An example of the working group’s detailed recommendations is described for Intercept 1, “Contact with Law Enforcement and Emergency Services” in Table 2.

Table 2.

Examples from the available resources and resource gaps identified by the working group under the Sequential Intercept Model’s Intercept 1 “Law Enforcement and Emergency Services” Intercept (COJENT Step 5)

| Resources Available | Gaps |

|---|---|

| Law enforcement training: Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training includes a 2-hour geriatrics training (20% of police force must be trained based on California mandate) | Lack of general awareness of national suicide hotline for older adults: 1-800-273-8255 (TALK) |

| Older Offender Population (OOP) training for hospital security (not mandatory) | Less than 5% of 911 staff have had crisis intervention training |

| San Francisco Sheriff’s Department primary care dispatch | 911 does not have enough staff with knowledge about older adults |

| Shelter cell-phone app for law enforcement professionals: “Elder App 368” | There is no OOP training for the San Francisco Sheriff’s Department |

| EMS-6 Frequent User Service Enhancement (FUSE) for homeless (a pilot project) | Adult Protective Services is underutilized and over capacity |

| Senior mobile crisis (Department of Public Health), 9am-5pm | Older adults must be released without mandatory follow-up if they have not reached 5150 criteria following evaluation |

| Dore Urgent Care Clinic, open 24/7, offers detox, peer services, medical screening, and residential support | Lack of communication between jail and hospital concerning medical needs of older adults and whether behavior leading to police arrest could be medical in etiology |

| County Hospital Psychiatric Emergency Services: • social worker on staff for referrals • two-week hotel voucher with 6 beds • phone triage available for police department • 18 PED beds |

Mobile crisis has a long wait time (up to one hour), is not necessarily geared to meet the unique needs of older adults |

| One community hospital has 3 behavioral health safe rooms and 18 all-purpose beds in the ER | Lack of a one-stop drop-off center for older adults in crisis |

| VA urgent care services | The psychiatric emergency services in the community are over capacity and often divert to other emergency rooms with less expertise |

| Plans for OOP team to serve patients with dementia awaiting commitment hearings | Limited resources for post-emergency room referral and follow-up especially after hours |

| There can be an hour wait for para-transport |

After completing this process, the working group developed a comprehensive flowchart based on the SIM Model of the points of contact that older adults may have with the criminal justice system; identified gaps, resources, and opportunities to improve the system at each point of contact; and developed three priority action items. For each of the three high-priority recommendations, the group created specific strategies and assigned initial tasks to a lead agency that would take responsibility for implementation as a next step for future study, Table 3. Results from the 2-day seminar were disseminated to all participants in the working group.

Table 3.

High-priority recommendations developed through consensus by the interdisciplinary working group (Step 5)

| High-Priority Recommendation | Strategies | Agencies Responsible for Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Increase resources for law enforcement and emergency services as alternatives to incarceration for older adults | • Create a public, live, and comprehensive database of crisis resources that meet older adults’ needs • Increase and improve training in aging-related health for all first responders • Identify High Users of Multiple Systems (“HUMS”) who are older adults and effective ways for sharing data about these individuals between health services and jails • Convene a meeting targeting the leadership of planning groups for special populations to discuss criminal justice-involved older adult population needs |

Taskforce with members from Sheriff’s Department, various community services (specified in the action plan document but not in this manuscript), 311, Department of Public Health, Adult Probation Department, Police Department, District Attorney’s Office, Public Defender’s Office, Mayor’s Office, local university and county hospital |

| 2. Improve methods to assess older adults with cognitive impairment and intervene to avoid incarceration or reduce length of incarceration | • Develop a neurocognitive screening tool and screen all older adults (55+) for cognitive impairment in jail: trigger automatic medical referral • Develop a criminal justice-dementia taskforce to identify case-by-case system change needs over 6 to 12 months |

Taskforce with members from the Police Department, Public Safety Department, District Attorney’s Office, county hospital, Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and from correctional health care (MDs and NPs from jail health) |

| 3. Improve and systematize post-incarceration discharge and care planning for older adults | • Hire a Discharge Planning Coordinator for older adults with expertise in gerontology • Define the scope of this discharge planning and the population who can receive full or elements of discharge planning • Create a taskforce for discharge planning and a discharge planning process, considering continuity of transitions and a written plan for older adults |

Taskforce with members from community organizations, Probation, Sheriff’s Department, Housing Organizations, the county’s Department of Aging and Adult Services, Adult Protective Services, Mayor’s Office, medical clinics serving this patient population, Department of Public Health, collaborative courts, and public guardians office |

Discussion

The COJENT Initiative developed a framework for how to use an interdisciplinary, community-wide, and participant-centered approach to generate a local plan with broad consensus for meeting the needs of the growing number of criminal justice-involved older adults, Figure 1. Through application of this framework, our local community created an action plan focused on the most critical needs of this population which reflects insights from a representative group of local professionals and the population itself. The 5-step COJENT Framework also ensured that the action plan was evidence-based, using quantitative and qualitative data to describe the local population, professional needs and public feedback. Processes of regular stakeholder and public engagement resulted in an activated group of champions representing a range of critical constituencies. Moreover, by generating new knowledge and disseminating findings through trainings, stakeholder meetings, and public forums we increased community awareness and understanding of the needs of this population and broadened support for action on their behalf among city leaders and policymakers.

The general shortage of a geriatrics-trained healthcare workforce creates an urgent need for innovative approaches to meeting the needs of medically and socially vulnerable populations of older adults, particularly as those populations grow (Kovner et al., 2002, Lee et al., 2013). The 5-step COJENT Framework is a system-wide assessment strategy that reflects the interdisciplinary approaches to clinical care taken by successful geriatric health care models such as the Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE) program and the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE). Both GRACE and PACE have been shown to effectively care for older adults by bringing together diverse experts from health and social service fields to assess patient needs, develop a care plan, and deliver health services (Counsell et al., 2006, Counsell et al., 2007, Hirth et al., 2009). The 5-step COJENT Framework capitalizes on the interdisciplinary nature of geriatrics to provide interdisciplinary community leaders with steps for developing a data-driven geriatrics strategy to meet the needs of the criminal justice-involved older adults in their community and in view of their local jurisdiction’s unique advantages and constraints.

The 5-step COJENT Framework draws on three models of planning for health care interventions (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, Health Impact Assessment and Sequential Intercept Mapping) and adapted elements of each to identify and address the unique challenges of criminal justice-involved older adults. As a result, the COJENT Framework accounts for the complex intersection of criminal justice, public health, and medical vulnerability by emphasizing local landscape analysis and data gathering to inform subsequent action planning. At the COJENT Framework’s core is a recognition of the need to pool local resources and strategies, train a diverse workforce in aging-related health issues, and conduct public and stakeholder outreach to advance the cause of criminal justice-involved older adults. Given the dramatic rise in the number of criminal justice-involved older adults in recent years, meeting this challenge is likely to prove critical to public health, criminal justice reform, and effective public spending.

Recommendations

Based on results of the COJENT Initiative, we recommend that community-based organizations working on behalf of vulnerable older adults and/or older adults in the criminal justice system consider partnering with an academic center or other researchers to engage in the following steps to develop a strategy for improving services in their community:

Convene a group of local experts, advocates, health and criminal justice professionals, criminal justice-involved older adults and their families, aging services, and other stakeholders to discuss the critical gaps in care in their community and begin to identify the priority areas for improvement.

Undertake an effort, either through primary data collection or through review of aggregate public health data, to quantify the issues and challenges that will need to be confronted.

Conduct targeted outreach to professionals to discuss their experiences with this population and engage them in basic training on aging and health, providing all professionals with a guide to community resources for vulnerable older adults at the very least.

Using multiple or regular sessions with stakeholders, review preliminary results of the above activities to ensure that the action planning process is participant-centered and interdisciplinary.

Hold public forums to share knowledge and raise awareness of this medically vulnerable population and to broaden community engagement in identifying and implementing solutions.

Identify community “champions” representing a cross-section of stakeholder groups who will commit to shaping and advancing the community response.

Using outside facilitators if possible, distill the information learned to develop a community action plan to better meet the needs of criminal justice-involved older adults at each SIM “intercept” along the criminal justice continuum.

Conclusion

The interdisciplinary 5-step COJENT Framework can serve as a tool for communities to identify the health and social service needs of local criminal justice-involved older adults, ascertain existing community resources that can be mobilized to meet those needs, and develop an actionable set of consensus recommendations for local policy and program change. Our next steps are to assess the implementation policy and practice recommendations that emanate from the COJENT Initiative for their impact on the community’s ability to better meet the needs of criminal justice-involved older adults.

Acknowledgments

All authors listed here meet the criteria of authorship for this manuscript and no others contributed to this manuscript sufficiently to warrant inclusion as an author. This paper is not under review or published in any publication. Dr. Williams received funding from the Department of Medicine at University of California, San Francisco, the Jacob & Valeria Langeloth Foundation, a Pilot Grant from the National Palliative Care Research Center, a Research Supplements for Aging Research on Health Disparities grant from the National Institute on Aging, and Tideswell at UCSF to collaborate with healthcare and criminal justice professionals and community members on this project. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the City and County of San Francisco or of the Department of Medicine at UCSF; nor does mention of any agency listed in this paper imply its endorsement. We also thank Hank J. Steadman and the Policy Research Associates for their help in developing the Sequential Intercept Map and facilitating the meeting.

References

- Aday RH. Aging Prisoners: Crisis in American Corrections. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ahalt C, Binswanger IA, Steinman M, Tulsky J, Williams BA. Confined to ignorance: the absence of prisoner information from nationally representative health data sets. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:160–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1858-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahalt C, Bolano M, Wang EA, Williams B. The state of research funding from the National Institutes of Health for criminal justice health research. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:345–52. doi: 10.7326/M14-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahalt C, Trestman RL, Rich JD, Greifinger RB, Williams BA. Paying the price: the pressing need for quality, cost, and outcomes data to improve correctional health care for older prisoners. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:2013–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry LC, Wakefield DB, Trestman RL, Conwell Y. Disability in prison activities of daily living and likelihood of depression and suicidal ideation in older prisoners. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1002/gps.4578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayview Senior Services Senior Ex-Offender Program [online resource] San Francisco: Bayview Senior Services; c2016 [updated 2016; cited 2016 Oct 6]. Available from: https://bhpmss.org/senior-ex-offender-program/. [Google Scholar]

- Bolano M, Ahalt C, Ritchie C, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Williams B. Detained and Distressed: Persistent Distressing Symptoms in a Population of Older Jail Inmates. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:2349–2355. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RT, Ahalt C, Steinman MA, Kruger K, Williams BA. Police on the front line of community geriatric health care: challenges and opportunities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2191–8. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodos AH, Ahalt C, Cenzer IS, Myers J, Goldenson J, Williams BA. Older jail inmates and community acute care use. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:1728–33. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Buttar AB, Clark DO, Frank KI. Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE): a new model of primary care for low-income seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1136–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, Tu W, Buttar AB, Stump TE, Ricketts GD. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2007;298:2623–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Baillargeon J. The health of prisoners. Lancet. 2011;377:956–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman R. Urban Institute Reentry Roundtable, Employment Dimensions of Reentry:Understanding the Nexus between Prisoner Reentry and Work. New York, NY: New York University Law School; 2003. Can We Close the Revolving Door?: Recidivism vs. Employment of Ex-Offenders in the U.S. [Google Scholar]

- Hirth V, Baskins J, Dever-Bumba M. Program of all-inclusive care (PACE): past, present, and future. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10:155–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys J, Ahalt C, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Widera E, Williams B. Do Palliative Care and Geriatric Factors Predict 6-Month ER Use in Older Jail Inmates? [Abstract] Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2015;51:413–414. [Google Scholar]

- Kovner CT, Mezey M, Harrington C. Who cares for older adults? Workforce implications of an aging society. Health Affairs. 2002;21:78–89. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WC, Dooley KE, Ory MG, Sumaya CV. Meeting the geriatric workforce shortage for long-term care: opinions from the field. Gerontology & geriatrics education. 2013;34:354–371. doi: 10.1080/02701960.2013.831348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschi T, Viola D, Sun F. The high cost of the international aging prisoner crisis: well-being as the common denominator for action. Gerontologist. 2013;53:543–54. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell J, Ison E, Joffe M. A glossary for health impact assessment. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:647–51. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.9.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munetz MR, Griffin PA. Use of the Sequential Intercept Model as an approach to decriminalization of people with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:544–9. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby JV, Beal AC, Frank L. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) national priorities for research and initial research agenda. JAMA. 2012;307:1583–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffrin M, Ahalt C, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Di-Thomas M, Williams BA. Educating prison and jail professionals to improve the care of older prisoners [Abstract] Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Hospice and Pallliative Medicine 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HN. Arrest in the United States, 1990-2010. Washington DC: Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2012. (NCJ 239423). [Google Scholar]

- Soones T, Ahalt C, Garrigues S, Faigman D, Williams BA. “My older clients fall through every crack in the system”: geriatrics knowledge of legal professionals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:734–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Williams BA, Barnes DE, Lindquist K, Schillinger D. Use of a modified informed consent process among vulnerable patients: a descriptive study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:867–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BA, Ahalt C, Greifinger R. The older prisoner and complex chronic care. In: Enggist S, Galea G, Udesen C, editors. Prisons and Health. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization Publications; 2014a. pp. 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Williams BA, Ahalt C, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Smith AK, Goldenson J, Ritchie CS. Pain Behind Bars: The Epidemiology of Pain in Older Jail Inmates in a County Jail. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2014b;17:1336–1343. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BA, Goodwin JS, Baillargeon J, Ahalt C, Walter LC. Addressing the aging crisis in U.S. criminal justice health care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012a;60:1150–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03962.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BA, Stern MF, Mellow J, Safer M, Greifinger RB. Aging in Correctional Custody: Setting a Policy Agenda for Older Prisoner Health Care. Am J Public Health. 2012b;102:1475–1481. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]