Abstract

Background

Although they have demonstrated efficacy in reducing substance use and criminal recidivism, competing priorities and limited resources may preclude drug court programs from formally addressing HIV risk. This study examined the efficacy of a brief, three-session, computer-facilitated HIV prevention intervention in reducing HIV risk among adult felony drug court participants.

Methods

Two hundred participants were randomly assigned to an HIV intervention (n = 101) or attention control (n = 99) group. All clients attended judicial status hearings approximately every six weeks. At the first three status hearings following study entry, clients in the intervention group completed the computerized, interactive HIV risk reduction sessions while those in the control group viewed a series of educational life-skill videos of matched length. Outcomes included the rate of independently obtained HIV testing, engagement in high risk HIV-related behaviors, and rate of condom procurement from the research site at each session.

Results

Results indicated that participants who received the HIV intervention were significantly more likely to report having obtained HIV testing at some point during the study period than those in the control condition, although the effect was marginally significant when examined in a longitudinal model. In addition, they had higher rates of condom procurement. No group differences were found on rates of high-risk sexual behavior, and the low rate of injection drug reported precluded examination of high-risk drug-related behavior.

Conclusions

The study provides support for the feasibility and utility of delivering HIV prevention services to drug court clients using an efficient computer-facilitated program.

Keywords: Computerized intervention, Drug Court, HIV

1. INTRODUCTION

Recent estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Hall et al., 2015) indicate that there are approximately 1.2 million adults and adolescents in the United States who are living with HIV infection. According to CDC estimates (CDC, 2012), injection drug use was the third most common high risk behavior among individuals living with HIV (8%) after male-to-male sexual contact (61%) and high-risk heterosexual contact (25%). Although injection drug users represent only 3% of the U.S. population, they make up over one-fifth of all individuals living with HIV (Lansky et al., 2014). In addition to risks of direct and indirect transmission associated with injection drug use, non-injection substance users are also disproportionately at risk for contracting HIV through sexual transmission. Substance use has been frequently linked to sexual risk behaviors and viral transmission among both heterosexuals and men who have sex with men (MSM). Clearly, drug and alcohol use can affect economic status, social network membership, and decision making with respect to partner selection and condom use. These factors frequently enable unsafe sexual practices (e.g., Kwiatkowski et al., 2000; Royce et al., 1997 Brewer et al., 2007; Celantano et al., 2008; Cheng et al., 2010). Finally, some research has indicated that the biological effects of drug abuse can affect a person’s susceptibility to HIV and progression of AIDS (e.g., Bagby et al., 2006; Samet et al., 2003, 2004).

1.1. HIV among criminal justice populations

Nationwide, there were an estimated 20,093 HIV/AIDS infected inmates in state and federal prisons at the end of December 2010, accounting for 1.5% of the total prison population (Maruschak, 2012). Furthermore, it has been estimated that 17% to 25% of all US individuals who are living with HIV/AIDS pass through the criminal justice system annually (e.g., Spaulding et al., 2009). High rates of drug use place criminal justice clients at an increased risk of contracting HIV infection and transmitting the virus to others as approximately 80% of prison and jail inmates were under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time of their arrest (Belenko and Peugh, 2005; James, 1988; Teplin, 1994).

Although the primary focus of HIV prevention efforts within the criminal justice system has centered on incarcerated populations (e.g., Braithwaite and Arriola, 2003; Hammett et al., 1999), the majority of offenders are actually under community supervision with over 5 million offenders on probation or parole (Glaze and Bonczar, 2009). Moreover, HIV infection in this population is primarily attributed to pre- and post-incarceration risk behaviors (Braithwaite et al., 2008; Blankenship, 2013). Rates of drug related risks are particularly high among individuals under community supervision (Glaze and Bonczar, 2009), placing them at higher risk of HIV infection. Belenko et al. (2004) reported HIV/AIDS prevalence rates among probationers and parolees that mirrored those observed in inmates, rates of injection drug use (IDU) that were slightly higher, and high prevalence of risky sex behaviors.

1.2. HIV risk among drug court participants

One type of community corrections program that has demonstrated substantial efficacy in improving client outcomes is drug courts. Drug courts provide a judicially supervised regimen of drug abuse treatment and other needed services for nonviolent, drug-abusing offenders in lieu of criminal prosecution or incarceration (Marlowe et al., 2008). Relatively little is known about HIV prevalence rates among drug court participants. A recent study (Festinger et al., 2012) examined the prevalence of HIV risk behaviors in an urban drug court sample. While rates of injection drug use were generally low, high risk sexual practices were prevalent. Over half of the sample reported having multiple sexual partners and almost two thirds reporting having unprotected sex in the past six months. High risk sexual behaviors were more prevalent among males and African Americans and decreased as a function of age. Given the high rates of drug use and engagement in other high risk behaviors among drug court clients, this segment of the criminal justice system is of particular relevance to HIV prevention and treatment.

Although drug courts have been quite successful in addressing participants’ drug and alcohol problems and their criminal propensities, time constraints, competing priorities, and limited resources may preclude many drug courts from including HIV interventions in their curriculum. Case managers, probation officers, and other stakeholders in drug courts typically have very large caseloads and have many issues to address with their clients. A computerized intervention may provide critical health information to the clients without taking up substantial staff time, delivering this information in a more cost-effective manner. Additionally, computerized interventions can be presented privately, offering clients essential knowledge and resources in a confidential manner.

1.3. Computer Assessment and Risk Reduction Education (CARE) for HIV risk reduction

We evaluated a number of brief computerized HIV risk reduction interventions for use in this study. We sought a brief computerized tool that followed the CDC’s recommendations for effective risk reduction interventions as well as the recommendations of effective computerized interventions more generally. These key elements include (1) keeping the session(s) focused on HIV risk reduction, (2) including an in-depth, personalized risk assessment, (3) acknowledging and providing support for positive achievements, (4) clarifying critical specifics rather than general misconceptions, (5) negotiating concrete, achievable, behavioral steps to reduce HIV risk, (6) allowing flexibility in the prevention approach, and (7) providing skill-building opportunities (Adopted from the CDC’s Revised Guidelines for HIV Counseling, Testing, and Referral, November 9, 2001/50(RR19); 1–58).

We ultimately selected the Computer Assessment and Risk Reduction Education (CARE) intervention as a model for our intervention. The platform uses narrated self-interviewing to ascertain behavioral risk, track drug use, assess self-efficacy/motivation, and provide tailored feedback on specific risk behaviors. Prior to developing a health promotion plan around sexual and drug use risk behaviors, users watch skill-building videos appropriate to their stage of readiness for behavior change (versions are available for heterosexual or same-sex active viewers). CARE counseling uses client-centered motivational interviewing (Miller et al., 2003) to solicit the individuals’ own impetus for behavior change, within an overall framework of Information, Motivation, and Behavioral Skills (IMB). Stage-based tailoring of feedback messages and videos follows the Transtheoretical Model (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1992) based on each individual’s readiness to change. It incorporates elements from the counseling evidence base including Project RESPECT, an individual-level, client focused, intervention designed to reduce sexual and drug use risk behavior related to HIV infection and other sexually transmitted diseases (Kamb et al., 1998; O’Donnel et al., 1998). CARE has been found to be acceptable and feasible for use in busy clinical settings among patients with limited computer experience and resulted in more patients receiving testing (Kurth et al., 2007).

This article presents during treatment findings from 200 participants in a two-group randomized controlled trial, comparing the efficacy of a modified version of the CARE intervention to an attention control procedure in reducing high-risk HIV behavior among individuals in a drug court. Specifically, we hypothesized that drug court clients assigned to the CARE intervention would have higher rates of HIV testing and condom procurement, and report lower rates of high-risk behavior.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was overseen by the Institutional Review Boards of the Treatment Research Institute and the City of Philadelphia and the Data Safety Monitoring Board of the Treatment Research Institute.

In Phase One of the study, prior to initiation of the randomized trial, we made a number of customizations to the CARE tool. To accomplish this we convened a multidisciplinary advisory team of experts in the fields of HIV research, substance abuse, drug courts, and corrections. The team met early in year one of the project to review the current version of the CARE tool and discuss specific modifications for its use as a self-administered ancillary intervention for drug court clients. Modifications to the tool included (1) contextualizing it to the case management and drug court setting (e.g., “It is great that you made it to your scheduled status hearing with the judge this week …”), (2) programming it to update the risk assessment and strategic plan at each of the first three scheduled status hearings, (3) adding several additional instructional videos, including topics such as needle sharing, needle cleaning, and how drug and alcohol use leads to poor decision making and increased sexual risk, (4) adding several brief intermittent objective quizzes with corrective feedback to reinforce learning of the material, and (5) adding messages for HIV positive subjects regarding options for HIV care and adherence. During months 4 through 12, the advisory team received regular updates on the progress of the agreed upon modifications and provided feedback to the programmers through the Principal Investigators. At month 9 the team reconvened to review the modified criminal justice CARE (CJ-CARE) program and provide final feedback before it was finalized by the programmers in month 12.

In Phase Two of the study we conducted a randomized controlled trial to examine the efficacy of the resulting CJ-CARE tool in reducing HIV risk behaviors among individuals in drug court. Procedures for this phase of the study were approved by the institutional review boards of the Treatment Research Institute and the City of Philadelphia.

2.1. Experimental conditions

2.1.1. Computer-facilitated HIV intervention

Individuals assigned to the experimental condition completed the self-directed CJ-CARE HIV intervention following each of their first three scheduled judicial status hearings. Each session, which was approximately 20 minutes, included a brief risk assessment, review of identified risks, structured skill building videos, and the development of a risk prevention action plan. Because of the adaptive nature of the CJ-CARE program, the content of each session was tailored to address the current risks of the participant. While the main focus of the intervention was on risk, the program provided individuals who reported being HIV infected with (1) a referral to treatment if they were not currently receiving medical care, and (2) specific education on the importance of adhering to HIV treatment.

2.1.2. Attention control

Individuals assigned to the attention control viewed a series of three educational videos following their first three scheduled status hearings. The educational videos focus on life skills including (1) stress reduction, (2) anger management, and (3) positive listening. Each session was approximately 20 minutes (about the same duration as the risk reduction modules). Importantly, the attention control videos did not directly address HIV or substance abuse so as not to dilute the observed effects of our intervention.

2.2. Participants

Two hundered consenting participants were recruited from an adult, felony pre-adjudication drug court located in Philadelphia. To be eligible for this drug court program, participants were required to (1) be at least 18 years of age, (2) be charged with a non-violent felony offense, (3) have no more than two prior non-violent convictions, juvenile adjudications or diversionary opportunities, (4) be in need of treatment for drug abuse or dependence as assessed by a clinical case manager employed by the court, and (5) volunteer to participate in the drug court program for at least 12 months.

Participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental (n = 101) or control (n = 99) group. Study participants were primarily male (81%) and most self-identified as African American (64%) or Caucasian (11%). Their mean age was 24.6 years (SD = 7.03), their mean years of education was 11.8 (SD = 11.58), and the large majority were never married (93%). In terms of drugs of abuse, the majority reported using marijuana (93%) and alcohol (70%), followed by opioids (31%), sedatives (24%), cocaine (12%), hallucinogens (7%), amphetamines (3%), and inhalants (1%).

As a check on randomization, a series of t-tests and chi-square analyses were used to compare the two groups on continuous (i.e., age, sex risk score) and categorical (i.e., gender, race, marital status, treatment history) baseline characteristics, respectively. As seen in Table 1, participants in the two groups did not differ on any baseline item, indicating that the randomization procedures were effective.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and baseline status by group

| Overall (n = 200) | Experimental (n = 101) | Control (n = 99) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M/N (SD/%) | M/N (SD/%) | M/N (SD/%) | |

| Age | 24.57 (7.03) | 25.37 (7.69) | 23.77 (6.61) | |

| Race | African American | 129 (64%) | 67 (66%) | 62 (62%) |

| Caucasian | 23 (11%) | 12 (12%) | 11 (11%) | |

| Gender | Male | 163 (81%) | 82 (81%) | 81 (82%) |

| Never married | 187 (93%) | 97 (96%) | 90 (91%) | |

| History of prior treatment | 42 (21%) | 22 (22%) | 20 (20%) | |

| RAB sex risk score | 3.20 (1.75) | 3.15 (1.63) | 3.31 (1.85) | |

2.3. Recruitment procedures

Project research assistants (RAs) attended all status hearings at the drug court. The RAs provided all defendants with an informational flyer containing an overview of the research study, including participation requirements, payment incentives, confidentiality protections (including the fact that research data would not be shared with court staff and other legal entities as the researchers have obtained an NIH confidentiality certificate), and their rights to refuse participation or withdraw from the study at any time without any negative consequences. Following their admission into the drug court program and up to their third scheduled status hearing, all individuals who indicated interest in the research project to the onsite RA were accompanied to a private office adjoining the court room to complete the consent process. Individuals who indicated that they wished to participate in the study and provided informed consent were then screened for eligibility. In the event that the consent could not take place at that time due to space limitations, courtroom hours of operation, or client commitments, the RAs rescheduled the appointment for a subsequent time. Importantly, during the consent procedure, participants were informed that all research data collected in the study would be kept strictly confidential and would not affect the status of their criminal case or their drug abuse treatment. Participants were also informed that we had obtained an NIH Confidentiality Certificate that shielded the research data from a subpoena or court order. Participants also completed a brief consent quiz (Festinger et al., 2014) that included an assessment of perceived coercion (Dugosh et al., 2014) to ensure their understanding of the study requirements, the risks and benefits, their human subject protections, and their autonomy.

2.4. Research procedures

Participants in both conditions met with a study RA following each of their first three judicial status hearings scheduled at approximately 6-, 12-, and 18-weeks post program entry. Following their hearings, project staff escorted participants to private rooms outside of the court room to complete their computer sessions. Participants were asked to sit at a desk to complete a brief session on a tablet style computer with headphones to provide additional privacy. The RA provided instructions on how to use the computer and informed participants to notify them when their session was complete, if they had any questions, or if they required a break. Following this instruction, the RA left the room. Each room contained a bowl of male and female condoms with a placard reading “Help yourself.” The bowl was filled with 25 male and 5 female condoms at the start of each session. The RA counted the number of condoms remaining after each session to determine the number of condoms procured by participants at each session. Upon completion of each session, the RA provided participants in both conditions with $25 gift cards redeemable at a centrally located shopping mall and scheduled them for the next computer session following their next scheduled judicial status hearing. In addition, participants in both conditions were given a card containing the address of a local free HIV-testing facility and a toll-free number that would allow them to locate other free testing facilities by calling, or texting a zip code. Upon completion of their third computer session, participants in both conditions were scheduled for their 9-month follow-up appointment.

2.5. Assessments

After providing written informed consent, all participants were asked to complete a brief assessment battery administered by a trained research technician. The battery consisted of a detailed locator form to provide contact information to assist with follow-up efforts, a demographic questionnaire, an HIV Testing Form (HTF), and the Risk Assessment Battery (RAB; Metzger et al., 2001). All of these measures were computerized to allow for more efficient administration and immediate and secure data storage. The baseline assessment took approximately 45 minutes to complete for which participants received a $30 gift card. Upon completion of their baseline assessment, all participants were scheduled to attend their first computer-facilitated intervention appointment approximately 6 weeks later as to coincide with their first status hearing. At the beginning of each of the 6-, 12-, and 18-week sessions, participants completed the self-administered HTF in private room prior to receiving the intervention or attention control procedures. Participants received $25 gift cards for completing each of these sessions. The follow-up interview was scheduled for 9-months post-program entry at which time participants completed the HTF and the RAB. Participants received a $40 gift card for follow-up completion.

2.6. Outcome measures

2.6.1. HIV testing rate

As discussed, all participants were provided with cards listing the number of a free-HIV testing program located a few blocks from the courthouse, as well as a toll-free number through which they could locate other free testing facilities by entering their zip code. HIV testing rates were obtained from the HTF collected following the 6-, 12-, and 18-week interventions and at the 9-month follow-up.

2.6.2. Condom procurement

All participants had access to free condoms throughout the study period. Study staff recorded the number of condoms procured from a bowl containing 25 male and 5 female condoms adjacent to the computer desk during each of the three computer sessions.

2.6.3. HIV risk behavior

High risk drug and sexual behavior was assessed using the RAB collected at the 9-month follow-up.

2.7. Data analysis

The two groups were compared on the proportion of individuals reporting HIV testing at any point during the study period using a chi-square analysis. In addition, testing rates in the two groups at each follow-up point were compared in a longitudinal model using a Generalized Estimation Equations (GEE) analysis. Rate of self-reported testing at weeks 12, 18, and 36 was the longitudinal binary dependent variable in the model. Group, time, and the group by time interaction were entered as predictors. An exchangeable correlation structure was specified for the model. Importantly, week 6 data were not included in the analysis as participants had not been exposed to the intervention at that time. The two groups were also compared on rate of condom procurement (operationalized as whether a client took condoms from the bowl) during the intervention period (i.e., weeks 6, 12, and 18) using a GEE analysis similar to that outlined above and on number of condoms taken at each visit using a GEE analysis specifying a poisson distribution. Finally, the two groups were compared on RAB sex risk scores at baseline and week 36 using a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Because there was very little variability on drug risk scores due to the low number of injection drug users, drug risk scores could not be analyzed.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Exposure to the intervention

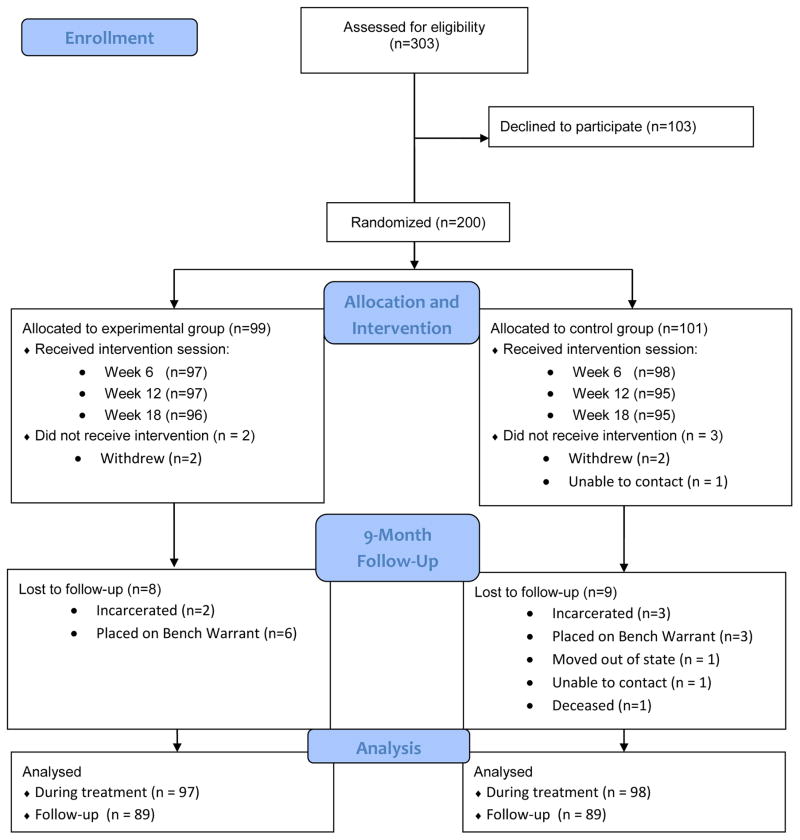

As depicted in the consort diagram (see Figure 1), 189 participants (94%) completed all three intervention sessions. Session 1 was delivered at week 5.72 post-baseline on average (SD = 2.67), Session 2 was delivered at week 11.22 on average (SD = 3.72), and Session 3 was delivered at week 16.71 (SD = 4.24) on average. Of those who did not attend all 3 sessions, 5 never came into contact with the intervention, 4 completed only the first session, and 2 completed the first two sessions. A total of 178 participants (89%) completed the 9-month follow-up session that occurred at week 38.79 on average (SD = 4.24). Among the 22 participants who did not attend the 9-month follow-up, 5 formally withdrew from the study, 10 were placed on a bench warrant, 4 were incarcerated, 1 was placed on house arrest, 1 was terminated from the program, and 1 moved out of the area. A logistic regression analysis was used to identify systematic differences between participants who did and did not complete the 9-month follow-up. The following variables were included in the model: treatment condition, age, race, gender, prior treatment history, and RAB sex risk score. No significant predictors were identified (p’s = 0.14–0.90), indicating that the follow-up sample is representative of the baseline cohort.

Figure 1.

CONSORT 2010 flow diagram.

3.2. HIV testing rates

Results indicated that participants in the experimental group were more likely to report HIV testing during the study period than those in the control group (Χ2(1) = 4.55, p = 0.03; OR = 1.86, 95% CI = 1.05–3.31). The longitudinal GEE analysis revealed a trend for the group effect with higher rates of testing in the experimental group than the control group (Χ2(1) = 3.35, p = 0.07; OR = 1.57, 95% CI = 0.96–2.57) and a significant effect for time (Χ2(1) = 20.05, p < 0.001). Contrasts indicated that overall participants were more likely to report HIV testing at the week 36 assessment than at the week 12 (OR = 2.55, 95% CI = 1.58–4.12) or week 18 (OR = 3.03, 95% CI = 1.91–4.80) assessments; rates of testing did not differ between the two groups at the week 12 and 18 assessments. Testing rates at each time point and overall are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Outcomes for each group

| Experimental | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Time point | M/N (SD/%) | M/N (SD/%) |

| HIV testingA | During study period | 52 (53%) | 35 (37%) |

| HIV testingB | Week 12 | 16 (16%) | 14 (15%) |

| Week 18 | 16 (16%) | 10 (11%) | |

| Week 36 | 37 (41%) | 21 (24%) | |

| Condom procurementC | Week 6 | 64 (65%) | 45 (47%) |

| Week 12 | 57 (58%) | 34 (37%) | |

| Week 18 | 51 (52%) | 39 (42%) | |

| RAB sex risk | Week 36 | 2.49 (1.58) | 2.81 (1.77) |

Significant group effect.

Trend for group effect; significant time effect.

Significant group effect; trend for time effect.

3.3. Condom procurement

Results indicated an effect for group with individuals being more likely to take condoms in the experimental condition than the control group (Χ2(1) = 8.30, p = 0.004; OR = 1.90, 95% CI = 1.23–2.93). There was a non-significant trend for time (Χ2(1) = 5.69, p = 0.06) with lower rates of procurement overall at weeks 12 (OR = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.51–0.98) and 18 (OR = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.51–0.98) relative to week 6. In a GEE analysis in which the number of condoms taken was modeled as a Poisson distribution, groups did not differ in the number of condoms taken (Χ2(1) = 2.62, p = 0.11).

3.4. HIV sex risk scores

Results from the repeated measures ANOVA indicated only an effect of time (F(1, 175) = 16.65, p < 0.001) with significantly lower sex risk scores overall at week 36 (M = 2.65, SD = 1.68) than at baseline (M = 3.18, SD = 1.77).

4. DISCUSSION

Although HIV risk reduction fits within the domain of services provided by community corrections programs such as drug court, which offer a combination of supervision and treatment, provision of such services is often constrained by limited staff and resources. Fortunately, the literature supports the efficacy of computerized brief interventions for reducing HIV risk (see Noar et al., 2009). The present study sought to examine the efficacy of using a brief, computerized, self-administered HIV risk reduction intervention in drug courts. Specifically, we hypothesized that participants assigned to the CJ-CARE intervention would have higher rates of HIV testing and condom procurement, and report lower rates of high-risk behavior. Results indicated that drug court clients assigned to receive the three-session educational and motivational HIV reduction intervention were significantly more likely to independently obtain HIV testing during the study period and procure free condoms from the research site than those assigned to receive a control intervention matched in time and form of delivery. However, results did not indicate any significant effect of the intervention on rates of high-risk sexual behavior.

The importance of obtaining regular HIV testing cannot be overstated. Individuals who know their status can be empowered to make informed decisions about their sexual health and their future. Given the efficacy of antiretroviral treatment in reducing viral load and HIV transmission, testing has become a cornerstone of HIV prevention (Cohen et al., 2011; Volkow and Montaner, 2011). Obtaining medical care and beginning the appropriate medication regimen can often translate into being able to live long, fulfilling, and healthy lives after receiving an HIV diagnosis. Conversely, finding out that one is HIV negative may reduce anxiety and tension, and improve relationships with sexual partners and significant others. Unfortunately fear, stigma, distrust, and misconceptions about HIV and its treatment coupled with marginalization from the health care system often prevent individuals from getting tested (American Psychological Association, 2010). Computerized testing support may help address some of these concerns.

This study has several important policy implications. First, the intervention represents an efficient strategy for motivating drug court clients to obtain HIV testing, thereby increasing the identification of individuals who are HIV positive. This closely comports with the seek, test, treat, and retain model of care (STTR) that focuses on reaching out to members of high risk groups (e.g., drug users), engaging them in HIV testing, and initiating and retaining individuals who are identified as HIV positive in the highly effective antiretroviral treatments now available to treat HIV. Given the nexus between substance abuse and engagement in criminal activity along with ongoing criminal justice reform to reduce incarceration, community corrections programs including drug courts should be equipped to address this important public health strategy.

The study has a number of limitations. First, the study included 200 participants participating in a single drug court, in a single jurisdiction, with one judge. Although the court is typical of many urban drug courts throughout the United States, the current findings may not readily generalize to courts in other jurisdictions serving different populations or where certain resources such as testing facilities are less accessible. As with virtually all empirical findings, future research is need to establish their generalizability. Second, although all participants had been charged with felony drug offenses, they had a very low rate of injection drug use. Because injection drug use places individuals at an even higher risk of HIV, this precluded us from examining the impact of the risk reduction intervention on high-risk drug behavior. Finally, examination of condom procurement cannot serve as an indicator of actual condom use. However, the differences observed between individuals in the two groups may indicate that the intervention impacted the perceived value of condoms.

The current study serves to support the feasibility and efficacy of a self-administered, brief computer-based intervention for increasing rates of HIV testing in a community corrections program. Given the self-administered format and relative brevity of the intervention, it is likely to be applicable and effective in a wide variety of community correctional milieus including probation and parole departments. Future research should be undertaken to replicate these findings in other drug courts and community correctional programs that serve the large majority of criminal offenders.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

High rates of drug use place criminal justice clients at an increased risk of contracting HIV infection and transmitting the virus to others.

Although HIV risk reduction interventions have been developed for individuals who are incarcerated or returning to the community following incarceration, no intervention has been developed and tested for the growing population of offenders diverted to community-based supervision and treatment

This two group randomized controlled trial evaluated the efficacy of a three-session computer-facilitated HIV prevention intervention among drug court clients.

Two hundred consenting participants from a city drug court were randomly assigned to receive the HIV risk reduction intervention (n = 99) or attention control procedure (n = 101).

Results indicated that participants who received the HIV risk reduction intervention were more likely to report having obtained HIV testing and had higher rates of condom procurement than those in the control condition.

The current study serves to support the feasibility and efficacy of a self-administered, brief computer-based intervention for increasing rates of HIV testing in a community corrections program.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This research was supported by grant R01-DA-030257 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NIDA.

Portions of these data were presented at the 77th Annual Scientific Meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence, Phoenix, AZ, and the 2015 Addiction Health Services Research Conference, Marina Del Rey, CA. The authors gratefully acknowledge the continuous collaboration of the Philadelphia Treatment Court, Office of the District Attorney of Philadelphia, Defender Association of Philadelphia, and the Philadelphia Coordinating Office of Drug and Alcohol Abuse Programs. We also thank Thea Musselman, Michael Stephens, Caitlin Ryan, Chloe Sierka, and Rachel Comly for their assistance with project management and data collection.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Contributors:

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript submitted for submission. DF and KD designed the study and prepared the manuscript. D.M. contributed to the conceptualization of study and preparation of the manuscript. A.K. contributed to the study methodology and manuscript preparation.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychological Association. HIV/AIDS Prevention Strategies For Mental Health: Module 5. Rockville, MD: 2010. https://www.apa.org/pi/aids/programs/hope/training/prevention-issues.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bagby GJ, Zhang P, Purcell JE, Didier PJ, Nelson S. Chronic binge ethanol consumption accelerates progression of simian immunodeficiency virus disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1781–1790. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenko S, Langley S, Crimmins S, Chaple M. HIV risk behaviors, knowledge, and prevention education among offenders under community supervision: a hidden risk group. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16:367–385. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.4.367.40394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenko S, Peugh J. Estimating drug treatment needs among state prison inmates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:269–281. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship KM, Smoyer AB. Crime, HIV And Health: Intersections Of Criminal Justice And Public Health Concerns. Springer; Netherlands: 2013. Between spaces: understanding movement to and from prison as an HIV risk factor; pp. 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite RL, Arriola KR. Braithwaite and Arriola respond. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1617. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite RL, Arriola KR. Male prisoners and HIV prevention: a call for action ignored. Am J Public Health. 2008;93:759–763. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer TH, Zhao W, Metsch LR, Coltes A, Zenilman J. High-risk behaviors in women who use crack: knowledge of HIV serostatus and risk behavior. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:533–539. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celentano DD, Latimore AD, Mehta SH. Variations in sexual risks in drug users: emerging themes in a behavioral context. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008;5:212–218. doi: 10.1007/s11904-008-0030-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveill Supp Rep. 2012:17. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng WS, Garfein RS, Semple SJ, Strathdee SA, Zians JK, Patterson TL. Binge use and sex and drug use behaviors among HIV(-), heterosexual methamphetamine users in San Diego. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45:116–133. doi: 10.3109/10826080902869620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugosh KL, Festinger DS, Clements NT, Marlowe DB. Developing an index to measure the voluntariness of consent to research. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2014;9:60–70. doi: 10.1177/1556264614544100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger DS, Dugosh KL, Marlowe DB, Clements N. Achieving new levels of recall in consent to research by combining remedial and motivational techniques. J Med Ethics. 2014;40:264–268. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2012-101124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger DS, Dugosh KL, Metzger DS, Marlowe DB. The prevalence of HIV riskbehaviors among felony drug court participants. Drug Court Rev. 2012;8:131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaze LE, Bonczar TP. Probation and parole in the United States, 2008 (NCJ 228230) 2009 Retrieved from U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics website: http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=1764.

- Hall HI, An Q, Tang T, Song R, Chen M, Green T, Kang J. Prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed HIV infection—United States, 2008–2012. MMWR. 2015;26:657–662. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammett TM, Harmon P. 1996–1997 Update: HIV/AIDS, STDs, and TB in Correctional Facilities. Series: Issues and Practices. NCJ 1999 [Google Scholar]

- James D. Prison, mental illness, and identity. Lancet. 1988;2:1371. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90912-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, Jr, Rhodes F, Rogers J, Bolan G, Zenilman J, Hoxworth T, Malotte CK, Iatesta M, Kent C, Lentz A, Graziano S, Byers RH, Peterman TA. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1161–1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth A, Spielberg F, Severynen A, Holt DA. A Randomized Controlled Trial Of Computer Counseling To Administer Rapid HIV Test Consent And Counseling In A Public ED. Paper presented at the 4th IAS HIV Conference; Sydney, Australia. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski CF, Booth RE. Differences in HIV risk behaviors among women who exchange sex for drugs, money, or both drugs and money. AIDS Behav. 2000;4:233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Lansky A, Finlayson T, Johnson C, Holtzman D, Wejnert C, Mitsch A, Gust D, Chen R, Yuko M, Crepaz N. Estimating the number of persons who inject drugs in the United States by meta-analysis to calculate national rates of HIV and hepatitis C virus infections. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB, Festinger DS, Dugosh KL, Arabia PL, Kirby KC. An effectiveness trial of contingency management in a felony preadjudication drug court. J Appl Behav Anal. 2008;41:565–577. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak LM. HIV in prisons, 2001–2010. AIDS. 2012;20:25. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DS, Navaline HA, Woody GE. Assessment of substance abuse: HIV risk assessment battery (RAB) In: Carson-DeWitt R, editor. Encyclopedia of Drugs, Alcohol, and Addictive Behavior. 2. Macmillian-Thompson Gale; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Miller W, Yahne C, Tonigan J. Motivational interviewing in drug abuse services: a randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:754–762. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Black HG, Pierce LB. Efficacy of computer technology-based HIV prevention interventions: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23:107–115. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831c5500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell C, O’Donnell L, Doval A, Duran R, Labes K. Reductions in STD infections subsequent to an STD clinic visit: using video-based patient education to supplement provider interactions. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25:161–168. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199803000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages of change in the modification of problem behaviors. Prog Behav Modif. 1992;28:183–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royce RA, Sena A, Cates W, Jr, Cohen MS. Sexual transmission of HIV. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1072–1078. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet JH, Horton NJ, Meli S, Freedberg KA, Palepu A. Alcohol consumption and antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected persons with alcohol problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:572–577. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000122103.74491.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet JH, Horton NJ, Traphagen ET, Lyon SM, Freedberg KA. Alcohol consumption and HIV disease progression: are they related? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:862–867. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000065438.80967.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammet TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 2006: declicing share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS One. 2009:4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA. Psychiatric and substance abuse disorders among male urban jail detainees. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:290–293. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.2.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Montaner J. The urgency of providing comprehensive and integrated treatment for substance abusers with HIV. Health Affair. 2011;30:1411–1419. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.