ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

To systematize and analyze the evidence from qualitative studies that address the perception of Brazilian Community Health Agents about their work.

METHODS

This is a systematic review of the meta-synthesis type on the work of community health agents, carried out from the Virtual Health Library using the descriptors “Agente Comunitário de Saúde” and “Trabalho”, in Portuguese. The strategy was constructed by crossing descriptors, using the Boolean operator “AND”, and filtering Brazilian articles, published from 2004 to 2014, which resulted in 129 identified articles. We removed quantitative or quanti-qualitative research articles, essays, debates, literature reviews, reports of experiences, and research that did not include Brazilian Community Health Agents as subjects. Using these criteria, we selected and analyzed 33 studies that allowed us to identify common subjects and differences between them, to group the main conclusions, to classify subjects, and to interpret the content.

RESULTS

The analysis resulted in three thematic units: characteristics of the work of community health agents, problems related to the work of community health agents, and positive aspects of the work of community health agents. On the characteristics, we could see that the work of the community health agents is permeated by the political and social dimensions of the health work with predominant use of light technologies. The main input is the knowledge that this professional obtains with the contact with families, which is developed with home visits. On the problems in the work of community health agents, we could identify the lack of limits in their attributions, poor conditions, obstacles in the relationship with the community and teams, weak professional training, and bureaucracy. The positive aspects we identified were the recognition of the work by families, resolution, bonding, work with peers, and work close to home.

CONCLUSIONS

This review provided an overview of the difficulties and positive aspects that are present in the daily work of community health agents. Given this, we have raised two challenges. The first one refers to how public policy makers need to appropriation the research results and the second one refers to the need to invest in studies that are designed to generate solutions for the difficulties faced by community health agents in their work.

Keywords: Community Health Workers, Family Health Strategy, Working Conditions, Health Human Resource Evaluation, Review

RESUMO

OBJETIVO

Sistematizar e analisar evidências levantadas por estudos de natureza qualitativa que abordam a percepção do ACS sobre seu trabalho.

MÉTODOS

Revisão sistemática, tipo metassíntese, sobre o trabalho dos agentes comunitários de saúde, realizada a partir da Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde utilizando os descritores “Agente Comunitário de Saúde” e “Trabalho”. A estratégia foi construída cruzando descritores, usando o operador booleano “AND”, e filtrando artigos brasileiros, publicados de 2004 a 2014, resultando em 129 artigos identificados. Foram excluídos artigos de pesquisas quantitativas ou quanti-qualitativas, ensaios, debates, revisões da literatura, relatos de experiências e pesquisas que não incluíram os ACS como sujeitos. Aplicando esses critérios, foram selecionados e analisados 33 estudos que possibilitaram: identificação de temas comuns e diferenças entre eles; agrupamento de principais conclusões; classificação de temas e interpretação de conteúdo.

RESULTADOS

A análise resultou em três unidades temáticas: Características do trabalho dos agentes comunitários de saúde; Problemas relacionados ao trabalho dos agentes comunitários de saúde; Aspectos positivos do trabalho dos agentes comunitários de saúde. Sobre as características, evidenciou-se que o trabalho dos agentes comunitários de saúde é permeado pelas dimensões política e social do trabalho em saúde com uso predominante de tecnologias leves, tendo como principal insumo o conhecimento que esse profissional obtém junto às famílias, sendo a visita domiciliar o palco para o desenvolvimento desse contato. Sobre os problemas no trabalho dos agentes comunitários de saúde, foram identificados: falta de limites em suas atribuições; condições precárias; obstáculos na relação com a comunidade e equipes; fragilidade na formação profissional e burocratização. Os aspectos positivos identificados foram: reconhecimento do trabalho pelas famílias e resolutividade, formação de vínculo, trabalho junto aos pares e perto da residência.

CONCLUSÕES

Essa revisão teceu um panorama sobre as dificuldades e aspectos positivos que se apresentam no cotidiano de trabalho dos agentes comunitários de saúde. Frente a isso, levantou dois desafios. O primeiro se refere à necessidade de apropriação dos resultados das pesquisas pelos formuladores de políticas públicas e, o segundo, à necessidade de investimento em estudos que se voltem para engendrar soluções para as dificuldades enfrentadas pelos agentes comunitários de saúde no seu trabalho.

Keywords: Agentes Comunitários de Saúde, Estratégia Saúde da Família, Condições de Trabalho, Avaliação de Recursos Humanos em Saúde, Revisão

INTRODUCTION

According to Tomaz 38 , the responsibilities of Brazilian Community Health Agents (CHA) can be summarized as the identification of risk situations, guidance for families and community, and referral of identified risk cases and situations to other members of health teams.

This means that the work of CHA is to assist in the planning and implementation of health actions both locally, by forwarding information from the health territory to the Family Health Strategy (FHS), and nationally, by feeding data to information systems of the Ministry of Health 29 .

This shows that CHA play an important role in the expansion and consolidation of primary health care (PHC) and are the subject of studies, among which we highlight, in this article, those focused on the investigation of how they perceive their work.

The relevance of a study on the perspective of workers is related to how services are conceived in a sphere in which players are thought abstractly, with generic characteristics, elaborated from theoretical conceptions. Until the service starts, workers and users will have few opportunities to position themselves on the rules and to try the process to verify difficulties or problems in the operation 8 , 16 , 34 .

In the case of public health services, such as the FHS, this situation is intensified by the distance between the front line and the regulatory agency. This distance hinders the identification of problems that occur in the operation of the service by those who could solve them, while at the same time workers are unaware of what managers expect from the actions at the front line. Such condition results in a mutual incomprehension that, in turn, reduces the chances of correcting eventual gaps in the service project 8 , 34 .

Thus, research studies that have explored the perception of front-line workers, such as CHA, expose the problems of work inadequacy caused by production system projects, processes, work organization, and tasks made from simplifying stereotypes 27 .

In this perspective, this article aims to systematize and analyze evidence from qualitative studies, carried out from 2004 to 2014, which discuss the perception of CHA about their work, offering evidence that can support the improvement of their work process.

METHODS

This article is a meta-synthesis review on studies on Brazilian CHA linked to the FHS, published between 2004 and 2014, which were selected from the Virtual Health Library (BIREME) that brings together Health Sciences databases, such as the Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences (LILACS), the Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), and the Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieve System Online (Medline). We chose this model because the meta-synthesis is a methodological approach used for the rigorous study of qualitative conclusions, whose interpretations and redefinitions result in the (re)conceptualization of the original conclusions 11 , thus meeting the objective of this article.

The guiding question for this review was: what are the evidences found by qualitative studies on the work of Brazilian CHA who are linked to the FHS, from 2004 to 2014? To this end, we searched BIREME in March 2015 using the descriptors “Agente Comunitário de Saúde” and “Trabalho”, in Portuguese, crossed from the Boolean operator AND, and we filtered Brazilian articles published between 2004 and 2014. Thus, we retrieved 129 articles, being 124 indexed in the Lilacs database and five in the Medline database.

This result was exported to the Mendeley reference manager, which detected six duplicate documents. Next, we started the screening process, which was carried out by the lead author with the supervision of the co-authors to minimize biases from the presence of only one evaluator. We screened the articles that presented original qualitative results and that addressed the work of CHA linked to the FHS.

The exclusion criteria considered the type of methodological approach used in studies, study subjects, and nature of the article. Thus, we removed quantitative or quanti-qualitative research articles, essays, debates, literature reviews, reports of experiences, as well as those that did not include CHA as research subjects.

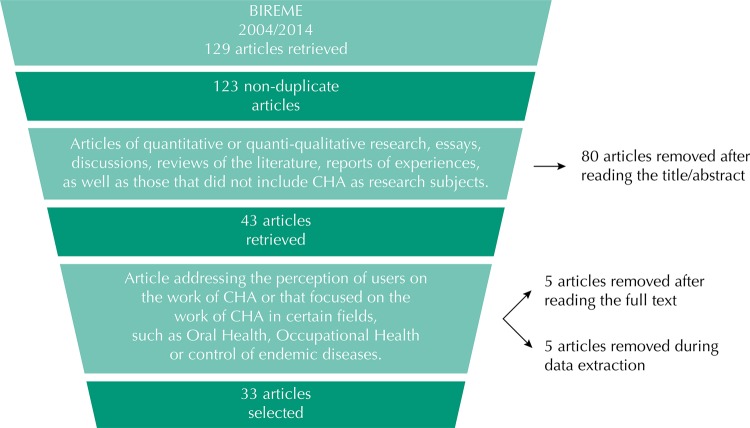

Following these criteria, the articles were selected in three stages: analysis of the titles, analysis of abstracts, and analysis of full texts. Thus, we removed 46 articles analyzing the title, 34 analyzing the abstract, and we fully analyzed 44 of them. In this last phase, we also removed 11 articles. The Figure shows the flow of article selection, whose result was the corpus of this meta-synthesis.

Figure. Flow of the selection process of the articles in the different phases of the meta-synthesis of the perception of CHA on their work.

BIREME: Latin-American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information; CHA: Community Health Agent

ANALYSIS OF RESULTS

The Box summarizes the 33 articles selected and their main results. We verified the following distribution of these studies among the Brazilian regions: twenty in the Southeast, seven in the Northeast, three in the South, two in the Midwest, and one that covered the North, Midwest, and Southeast at the same time. Regarding this aspect, we highlight a discrepancy in the number of studies carried out in the Southeast region compared to the other Brazilian regions, which is consistent with an article that has shown that health research in Brazil is concentrated in the Southeast region 14 .

Box. Summary of the information from selected studies for the meta-synthesis of the perception of Community Health Aagents about their work.

| Authors/year | Region | Subjects of the research | Procedure for data collection | Subject |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baralhas M, Pereira MAO 1 (2011) | Southeast | CHA | Interview | Representation of CHA on their care practices |

| Barbosa RHS, Menezes CAF, David HMSL, Bornstein VJ 2 (2012) | Southeast | CHA | Focus group | Relationship between the gender dimension and the work of CHA |

| Binda JB, Bianco MF, Sousa EM 3 (2013) | Southeast | CHA | Observation, discussion groups, and interview | Analysis of the work processes of CHA |

| Bornstein VJ, Stotz EM 4 (2008) | Southeast | CHA, physicians, and nurses of FHS | Interviews, documentary analysis, and participant observation | Characterization of the types of mediation present in the work of CHA |

| Carli R, Costa MC, Silva EB, Resta DG, Colomé ICS 5 (2014) | South | CHA | Interview | Perceptions of CHA on the reception and bonding practices |

| Coriolano MWL, Lima LS 6 (2010) | Northeast | CHA | Focus group | Description of the work process of CHA |

| Costa MC, Silva EB, Jahn AC, Resta DG, Colom ICS, Carli R 7 (2012) | South | CHA | Interview | Analysis of the work process of CHA |

| Ferreira VSC, Andrade CS, Franco TB, Merhy EE 9 (2009) | Northeast | CHA | Interview and focus group | Production of care, work process, technologies, and restructuring of the productive process of CHA |

| Filgueiras AS, Silva ALA 10 (2011) | Southeast | CHA | Interview | Discussion of the facilitating and limiting aspects of the activities assigned to CHA |

| Fonseca AF, Machado FRS, Bornstein VJ, Pinheiro R 12 (2012) | North, Midwest, and Southeast | CHA, work supervisors of CHA, and service managers | Interview and focus group | Analysis of the processes of evaluation of the work of CHA |

| Galavote HS, Franco TB, Lima RCD, Belizário AM 13 (2013) | Southeast | CHA | Interview and observation | Work process of CHA |

| Gomes AL, Lima Neto PJ, Silva VLA, Silva EF 15 (2011) | Northeast | CHA | Interview and observation | Relationship between the organization and the work process and mental health of CHA |

| Jardim TA, Lancman S 17 (2009) | Southeast | CHA | Group of Work Psychodynamics | Discussion about living and working in the same community |

| Lara MO, Brito MJM, Rezende LC 18 (2012) | Southeast | CHA, nurse, physician, nursing assistant, and users | Interviews | Analysis of the influence of the cultural practices present in the work of CHA |

| Lima AP, Corrêa ACP, Oliveira QC 19 (2012) | Midwest | CHA | Interview and participant observation | Identification of the knowledge of CHA about PCIS instruments/records |

| Lopes DMQ, Beck CLC, Prestes FC, Weiller TH, Colomé JS, Silva GM 20 (2012) | South | CHA | Focus group | Suffering and pleasure in the work of CHA |

| Martines WRV, Chaves EC 21 (2007) | Southeast | CHA | Interview and observation | Representations of CHA about the vulnerabilities for suffering at work and the manifestations of this suffering in the performance of work |

| Nascimento GM, David HMSL 22 (2008) | Southeast | CHA | Participant observation | Development of an instrument for risk assessment of the work of CHA |

| Oliveira AR, Chaves AEP, Nogueira JA, Sá LD, Collet N 23 (2010) | Northeast | CHA | Questionnaire | Research on the satisfaction and limitation in the daily work of CHA |

| Oliveira DT, Ferreira PJO, Mendonça LBA, Oliveira HS 24 (2012) | Northeast | CHA | Interview | Perception of CHA about their work process |

| Peres CRFB, Caldas Júnior AL, Silva RF, Marin MJS 25 (2011) | Southeast | CHA | Interview | Analysis of the difficulties and facilities of CHA regarding teamwork. |

| Pinheiro RL, Guanaes-Lorenzi C 26 (2014) | Southeast | CHA | Groups of discussion | Perception of CHA about their practices with social networks |

| Queirós AAL, Lima LP 28 (2012) | Northeast | CHA, managers, legislators, social movement, movement of CHA and popular movement, researcher | Interview | Analysis of the social practice of the work of CHA |

| Rosa AJ, Bonfanti AL, Carvalho CS 30 (2012) | Midwest | CHA and users | Groups of work psychodynamics, interview, and observation | Analysis of the relationship between work and psychological distress of CHA |

| Sakata KN, Mishima SM 31 (2012) | Southeast | CHA, dental office assistant, nursing assistant, dental surgeon, nurse, physician, and health unit manager | Interview and participant observation | Analysis of social relationships between CHA and family health teams |

| Santos LFB, David HMSL 32 (2011) | Southeast | CHA | Interview | Identification of the occupational stress factors reported by CHA and analysis of their relation with possible health effects |

| Schmidt MLS, Neves TFS 33 (2010) | Southeast | CHA | Focus groups | Analysis of the aspects of the implementation of the Family Health Program (FHP) as a primary public policy in the struggle with the hegemonic medical-care model in the country |

| Sossai LCF, Pinto IC, Mello DF 36 (2010) | Southeast | CHA and users | Interviews | Presentation of the work of CHA from the perspective of users and CHA |

| Souza LJR, Freitas MC 37 (2011) | Northeast | CHA | Interview and participant observation | Analysis of workplace violence in CHA |

| Trapé CA, Soares CB 39 (2007) | Southeast | CHA | Focus groups and interviews | Conceptions of health education present in the work of CHA |

| Vilela RAG, Silva RC, Jackson Filho JM 40 (2010) | Southeast | CHA and managers | Interview and observation | Analysis of the relationship between complaints of suffering and the conditions of work of CHA and proposed measures to modify them |

| Wai MFP, Carvalho AMP 41 (2009) | Southeast | CHA | Interview | Perception of CHA on events that cause overload and coping strategies used by them. |

| Zanchetta MS, Leite LS, Perreault M, Lefebvre H 42 (2005) | Southeast | CHA | Individual and group interviews. Observation | Perception of CHA on barriers in the work practice |

CHA: Community Health Agents; PCIS: Primary Care Information System; FHS: Family Health Strategy

The analysis of the results of the articles produced three thematic categories, presented below, that became the axis to understand the problem explored in this meta-synthesis.

Characteristics of the Work of CHA

The work of CHA is more permeated by the political and social dimensions of health work 6 , 31 , with predominant use of light technologies, such as communication 6 , 7 , reception and bond 1 , 5 , 7 , 9 , 17 , dialog 4 , and listening 1 , 4 , 26 .

Some studies 4 , 9 point out that the main input of the work of CHA is the knowledge obtained in the contact with families and, as far as this contact is concerned, research studies state that home visits are a privileged stage for its development 1 , 4 , 5 , 10 .

Vilela et al. 40 state that home visits are primary activities to build the relationship between CHA and users, and they also represent the main means to promote the health of the surrounding community. From the managerial point of view, home visits are valued operations that count as production of the unit.

One study 12 has specifically addressed the evaluation of the work of CHA, evidencing that this evaluation is based on a quantitative bias based on the achievement of goals that predominantly encompass tasks related to the biomedical field.

Problems Related to the Work of CHA

The main challenges related to the work of CHA evidenced in the studies are described below.

Lack of limits in the work of CHA

Thirteen articles have addressed the lack of limits of the actions of CHA summarized in two issues: idealization of the work and lack of limits of the attributions of this professional.

Regarding the idealization of the work, studies have shown that CHA perceive as their mission the solution of all the issues of the families and the community they serve, idealizing their practices and disregarding the importance of other resources to carry out their actions 1 , 21 . Studies show that CHA understand their work as a vocation based on values of friendship, solidarity, voluntariness, and charity, which are based on the perception about their attributions as elements that contribute to the difficulty in delimiting their role 1 , 2 , 21 , 36 , 42 .

The lack of limits of the work of CHA can be understood both in studies that highlight the lack of clarity of their duties 20 , 21 and in studies that emphasize the excess of planned functions 6 , 15 , 20 , 22 , 23 , 30 . For the excess of functions, the CHA perform tasks that do not concern them, such as: work at the reception 28 , 36 , 40 , scheduling of appointments 1 , 15 , 28 , 36 , organization of folders and medical records 36 , control of materials and warehouse and cleaning service 36 , delivery of referrals to specialists 15 , 31 , sending of messages from the health service to users 31 , and feeding of children in the absence of parents 42 .

In addition to the tasks that are not the responsibility of CHA, other functions are gradually incorporated into their role, officially, such as the weighing of families for their re-registration in the government program Bolsa Família and actions to prevent and combat dengue fever 15 .

This framework reinforces that CHA are seen as a multipurpose workers, given the lack of definition of the limits of their professional duties and the idealization of the role, and thus their scope of action is constantly extended.

Precarious working conditions

Another problem related to the activities of CHA is their precarious working conditions, identified in thirteen articles: explicitness of the fragility of the employment relationship 1 , 3 , 33 , exposure to work hours that go beyond the opening hours of the health unit and which invades the private life 1 , 6 , 7 , 17 , 40 , 41 , care for a greater number of families than what is advocated 35 , exposure to unhealthy working conditions 30 , 41 , low pay and absence of social protection 1 , 4 , 7 , 30 , poor recognition of work by managers, peers, and users 2 , 12 , 20 , 24 , 26 , 32 , and precariousness of the system 17 , 40 .

As a consequence of this precariousness, two studies have shown that CHA view the profession as a temporary activity, since there is no prospect of transformation of the work situations or a planned career plan 20 , 30 .

The precariousness of the work of CHA is also related to the fragility of the health system, which cannot adequately meet the demand of users, with a lack of opening for appointments and examinations, materials, and medications. This situation affects the relationship between CHA and the community they serve, since many users attribute to them the administration of the lack of resources of the health unit and the system, considering their responsibility for the front line in the care of the population 17 , 40 .

Relationship with the community

As for the relationship of CHA with the community, the most reported problems were: obligation to live in the community where they work, coexistence with community problems, exposure to violence, and relationship with users.

The CHA need to live in the community they serve, which is a problem as these workers have their private life exposed when sought outside working hours, on weekends, and in living spaces in the neighborhood, such as church and fairs, thus overloading them 6 , 10 , 17 , 20 , 41 . In this way, these professionals have an uninterrupted involvement with the users of the health service. Jardim and Lancman 17 emphasize that, just as CHA enter the private world of users, the private world of these workers is also invaded by the community and its problems, as they are literally unable to keep a distance from the population for which they are responsible.

The second subject of this category addresses studies that point to the fact that CHA generally work with poor populations living in peripheral regions. In these regions, social problems are more acute, increasing the emotional load related to work, both because of the difficulty in managing these issues and because CHA often share the same problems as they also live in these communities 4 , 6 , 17 , 20 , 23 , 41 .

The third subject related to the relationship between CHA and the community refers to the exposure of these workers to violence. Studies carried out in large urban centers have shown that these professionals work in regions where violence is pronounced, especially that related to organized crime and drug trafficking 32 , 37 , 42 .

Therefore, because they work and live in the same territory, CHA are more vulnerable to situations of conflict compared to the other FHS workers who do not circulate as much. In this sense, studies 6 , 37 state that CHA generally need to build strategies to cope with these situations, corroborating the findings of Jardim and Lancman 17 , who report that CHA avoid reporting to the police or Child Protective Council for fear for their safety.

In line with this issue, the problem of the relationship between CHA and users is manifested. According to Bornstein and Stotz 4 , CHA perceive that users expect a more viable access to health services, which is similar to the result of other studies 10 , 17 . However, when these professionals cannot respond to the demands of users for appointments, medications, exams, or access to other services, users lose their trust on CHA without considering that the lack of access is a matter of how the system works1–5,7,22,23,30,32,33,40,41. Jardim and Lancman 17 have found that the credibility of CHA in the community is directly associated to the resolution of the demands of users and this credibility can be hampered by aspects related to the structuring of the service and the inoperability of the health system.

In this sense, another dimension that is related to this issue has been identified by Santos and David 32 and refers to the violence present in the work of CHA, which emerges from the relationship of these professionals with the community. These authors have observed that the frustration of users to demands not met can also turn into verbal aggression or intense psychological pressure.

Fragility in the professional qualification of CHA

The CHA consider their professional training insufficient and the main perceived gaps were: excess of standardization of contents that address predominantly technical-scientific subjects and that do not include data on the local reality, lack of focus on theoretical and practical aspects that could assist them in coping with issues of the daily work, such as the management of family and social problems, and, finally, restriction of the work hours offered for such activity 1 , 4 , 7 , 10 , 19 , 36 , 39 .

Bureaucratization of the work

The bureaucratization of the work of CHA is another evidence highlighted in the studies included in this meta-synthesis, and it is related, in the perception of these workers, to the collection of data on the surrounding population, especially those related to diet and use of the Primary Care Information System (PCIS) 19 .

In this sense, authors 19 state that CHA have difficulties in identifying, naming, and describing the records they need to fill in to feed the PCIS, and they also do not understand the variables, terms, and pathologies that make up these instruments. As a consequence, tasks related to health surveillance, notwithstanding their importance to the FHS, focus on the work of CHA as mere statistical data collection activities, with little meaning for these workers 1 , 32 , 36 , 40 .

Other aspects regarding the perception of bureaucratization were listed in the study of Nascimento and David 22 , which indicate the presence of the following characteristics in the work process of CHA: standardization, great number of prescriptions, and organization according to the logic of process divisions and hierarchy.

In this perspective, bureaucratization starts to permeate even the tasks that are not administrative, given the predominance of the logic to count procedures, instead of assessing the quality of the care provided 9 , 12 , 19 .

Problems in the relationship with the team

Teamwork was identified as a limiting factor in the work of CHA, when there is a lack of articulation with other professionals and an inflexibility of relationships produced by the work organization that hinders the exchange between players outside the spaces established for this end 7 , 13 , 41 , 42 .

Peres et al. 25 , when analyzing the perceptions of CHA on teamwork, indicate that these workers feel as the weakest link in the relationship with other FHS professionals. Such situation is in line with the findings of other authors 3 , 9 , 40 who have identified a hierarchy of knowledge in the FHS that gives to CHA an unequal role in the planning and decision making of interventions.

When analyzing the work of CHA in the interface with the teams, a dysfunction was found in the relation between CHA and teams, from the different ways of approaching the problems of users. In this sense, it is common for teams not to value what CHA raise as a priority in meeting the needs of users 40 .

In addition, the organization of work in the FHS is guided by the achievement of goals, excess of activities, and little availability of time for the exchange between professionals, which hinders the establishment of teamwork and is negatively reflected on the work of CHA 31 , 41 , 42 .

Other perceived difficulties are caused by “personal differences; difficulty in visualizing all actions; lack of flexibility, communication, cooperation, responsibility, and horizontality of actions” (Peres et al. 25 , p.908).

Facilitating Aspects of the Work of CHA

We describe below the positive aspects that act as facilitators of the work of CHA identified by the selected studies.

Recognition of the work by families/community and resolubility

The most recurrent positive aspect in this meta-synthesis was the recognition of the families in relation to the work of CHA. Thus, several authors 1 , 6 , 7 , 13 , 23 , 36 , 42 have pointed out that CHA feel satisfied with their work when they see that they are useful to the community, when there has been a change in the health conditions of users, or when families recognize their competence and commitment. Two studies 2 , 20 reinforce these findings, adding that the recognition of the assisted population is a motivating factor for CHA, strengthening their self-esteem and contributing to the conformation of their identity.

The resolubility of CHA has been identified in the study by Lopes et al. 20 as “possibility to solve the problems of users and to verify that the work carried out is improving the health conditions of the community” (p.635). In this context, resolubility is identified as a positive aspect related to the work of CHA, since this characteristic is linked to the feeling of gratification and utility, thus contributing to the professional satisfaction of these workers 23 , 36 .

Bonding with families and community

Seven studies included in this meta-synthesis show that CHA perceive the bond with the user as a necessary condition for their work to happen, because, according to some authors 1 , 5 , 13 , 31 , 42 , this bond is intimately related to the mission of being the link between health professionals and the community. The construction of the trust and credibility of CHA among users has been identified in five studies 1 , 5 , 17 , 18 , 31 , as dimensions that favor the establishment of the bond. This is because they allow the worker to approach problems that extrapolate the biological dimension, despite being part of the health-disease process, such as situations of family or community conflict, domestic violence, poverty, sexual abuse, child neglect, ill-treatment of older adults, trafficking, and use of drugs. Such situations are complex and they cannot always be accessed without building a trust relationship between users and CHA.

Working together with peers

Peer-to-peer activities were identified as facilitators when they were established by the positive relationships between CHA and other staff members, allowing the horizontal discussion of daily problems and allowing the sharing of work strategies 9 , 25 , 31 . Such a construction is favored in team meetings from the perspective of CHA 24 .

In fact, according to Filgueiras and Silva 10 , the positive aspects of teamwork are the support for the actions of CHA, as the integration with the other professionals allows the collective construction of coping mechanisms for the problems identified.

Formal work close to the residence

The last positive trait in the work of CHA identified in the studies analyzed concerns the formal employment relationship. This situation has been evidenced in the study by Sossai et al. 36 , which show the rare presence of job vacancies that comply with the norms of the Labor Law Consolidation in the region of the study. This distinguishes the work of CHA from the other workers, as CHA can combine formal employment with living close to their residence, meeting the findings of Zanchettaet al. 42

In addition, two other studies 2 , 3 have shown that work close to home is perceived as advantageous, especially for women, who are most of the CHA. This situation enables the combination of the care of the family with the professional work.

DISCUSSION

We aimed to collect and analyze evidence on the work process of CHA with this meta-synthesis. We analyzed 33 articles, which allow us to perceive the characteristics of the profession, as well as problems and positive aspects related to professional work. In this sense, we emphasize that the academic production that addresses the subject of the work of CHA is useful in pointing this evidence.

The duties of CHA need to be reviewed in order to better define their role and size their actions according to the resources available, avoiding, above all, the abuse of functions.

We need to overcome the precariousness of the work of CHA by building a career plan that values not only the knowledge accumulated over time but also the strategic role they play in the consolidation of the FHS.

Another important issue raised in this meta-synthesis refers to the need to rethink the organization of work within the FHS, incorporating demands related to the specificities of the work of CHA. In this sense, the organization of the work of FHS teams must be reviewed to allow CHA to have a space of dialog strengthened with the other members of the team. In fact, horizontal teamwork, with integration among members, is positively reflected in the work of CHA.

Regarding the organization of the work, we can observe the need to rethink the bureaucratic tasks inherent to CHA. This would be done, on the one hand, by giving a meaning to the filling of the reports used to collect population data, because as Lima et al. 19 have observed, the CHA have difficulty recognizing the usefulness of these instruments. On the other hand, we can mention that although the work in the FHS and, in particular the work of CHA, is based on an expanded concept of health, in the principles of the PHC which is parametrizated qualitatively, we can observe the prevalence of the normative logic that organizes the work hierarchically and using processes.

This fact is also reflected in how the work done is evaluated, which is given by the counting of procedures and not by the quality of the care. Given this situation, we need to urgently rethink models that evaluated the work of CHA that are in line with the tools and values recommended for the FHS while also contemplating the specificities of the profession.

Regarding the issue of living with the community problems, the fact that CHA live in the same territory where they work is a challenge. Although this exposes workers to violence and to the invasion of their private life, the most significant set of knowledge of the CHA is structured in the contact with the community. In addition, we observed that the work close to the residence also benefits these workers.

Regarding the fragility in the training of the CHA, Ordinance 253, of September 25, 2015, recently established the Introductory Course for CHA, which standardized the minimum work hours for this training and defined the basic curricular components.

In conclusion, regarding the distribution of research in Brazil, we verified a predominance of studies carried out in the Southeast region and in large urban centers. In this sense, new studies can be carried out in Brazilian regions with different realities, such as those that attend to riverine or rural populations, where the work of CHA assumes other characteristics. Regarding the meta-synthesis carried out, we presented an overview of the difficulties and positive aspects that are present in the daily work of CHA. Given this, this review posed two challenges for future research. The first one refers to how public policy makers need to appropriate the research results and the second one refers to the need to invest in studies that are designed to generate solutions for the difficulties faced by CHA in their work.

Footnotes

Funding: Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES – Process BEX 5217/2014-08 Program CAPES-COFECUB 702/11).

REFERENCES

- 1.Baralhas M, Pereira MAO. Concepções dos agentes comunitários de saúde sobre suas práticas assistenciais. Physis. 2011;21(1):31–46. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-73312011000100003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbosa RHS, Menezes CAF, David HMSL, Bornstein VJ. Interface. 42. Vol. 16. Botucatu: 2012. Gênero e trabalho em saúde: um olhar crítico sobre o trabalho de agentes comunitárias/os de saúde; pp. 751–765. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-32832012000300013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binda JB, Bianco MF, Sousa EM. O trabalho dos agentes comunitários de saúde em evidência: uma análise com foco na atividade. Saude Soc. 2013;22(2):389–402. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-12902013000200011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bornstein VJ, Stotz EN. O trabalho dos agentes comunitários de saúde: entre a mediação convencedora e a transformadora. Trab Educ Saude. 2008;6(3):457–480. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1981-77462008000300004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carli R, Costa MC, Silva EB, Resta DG, Colomé ICS. Acolhimento e vínculo nas concepções e práticas dos agentes comunitários de saúde. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2014;23(3):626–632. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072014001200013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coriolano MWL, Lima LS. Grupos focais com agentes comunitários de saúde: subsídios para entendimento destes atores sociais. [citado 19 out 2017];Rev Enferm UERJ. 2010 18(1):92–96. http://www.facenf.uerj.br/v18n1/v18n1a16.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costa MC, Silva EB, Jahn AC, Resta DG, Colom ICS, Carli R. Processo de trabalho dos agentes comunitários de saúde: possibilidades e limites. Rev. Gaucha Enferm. 2012;33(3):134–140. doi: 10.1590/s1983-14472012000300018. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1983-14472012000300018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derani C. Privatizações e serviços públicos: as ações do Estado na produção econômica. São Paulo: Max Limonad; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferreira VSC, Andrade CS, Franco TB, Merhy EE. Processo de trabalho do agente comunitário de saúde e a reestruturação produtiva. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25(4):898–906. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009000400021. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2009000400021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filgueiras AS, Silva ALA. Agente Comunitário de Saúde: um novo ator no cenário da saúde do Brasil. Physis. 2011;21(3):899–916. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-73312011000300008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finfgeld DL. Meta-synthesis: the state of the art - so far. Qual Health Res. 2003;13(7):893–904. doi: 10.1177/1049732303253462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732303253462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fonseca AF, Machado FRS, Bornstein VJ, Pinheiro R. Avaliação em saúde e repercussões no trabalho do agente comunitário de saúde. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2012;21(3):519–527. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-07072012000300005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galavote HS, Franco TB, Lima RCD, Belizário AM. Interface. 46. Vol. 17. Botucatu: 2013. Alegrias e tristezas no cotidiano de trabalho do agente comunitário de saúde: cenários de paixões e afetamentos; pp. 575–586. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-32832013005000015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guimarães R. Pesquisa em saúde no Brasil: contexto e desafios. Rev Saude Publica. 2006;40(Espec):3–10. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102006000400002. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102006000400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomes AL, Lima PJ, Neto, Silva VLA, Silva EF. O elo entre o processo e a organização do trabalho e a saúde mental do agente comunitário de saúde na Estratégia Saúde da Família no município de João Pessoa – Paraíba- Brasil. Rev Bras Cienc Saude. 2011;15(3):265–276. https://doi.org/10.4034/RBCS.2011.15.03.02. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomes RS. O trabalho no Programa Saúde da Família do ponto de vista da atividade: a potência, os dilemas e os riscos de ser responsável pela transformação do modelo assistencial. Rio de Janeiro: Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública Sergio Arouca; 2009. tese. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jardim TA, Lancman S. Interface. 28. Vol. 13. Botucatu: 2009. Aspectos subjetivos do morar e trabalhar na mesma comunidade: a realidade vivenciada pelo agente comunitário de saúde; pp. 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-32832009000100011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lara MO, Brito MJM, Rezende LC. Aspectos culturais das práticas dos agentes comunitários de saúde em áreas rurais. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2012;46(3):673–680. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342012000300020. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0080-62342012000300020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lima AP, Corrêa ACP, Oliveira QC. Conhecimento de agentes comunitários de saúde sobre os instrumentos de coleta de dados do SIAB. Rev Bras Enferm. 2012;65(1):121–127. doi: 10.1590/s0034-71672012000100018. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-71672012000100018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopes DMQ, Beck CLC, Prestes FC, Weiller TH, Colomé JS, Silva GM. Agentes comunitários de saúde e as vivências de prazer – sofrimento no trabalho: estudo qualitativo. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2012;46(3):633–640. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342012000300015. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0080-62342012000300015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martines WRV, Chaves EC. Vulnerabilidade e sofrimento no trabalho do agente comunitário de saúde no Programa de Saúde da Família. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2007;41(3):426–433. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342007000300012. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0080-62342007000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nascimento GM, David HMSL. Avaliação de riscos no trabalho dos agentes comunitários de saúde: um processo participativo. [citado 19 out 2017];Rev Enferm UERJ. 2008 16(4):550–556. http://www.facenf.uerj.br/v16n4/v16n4a16.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oliveira AR, Chaves AEP, Nogueira JA, Sá LD, Collet N. Satisfação e limitação no cotidiano de trabalho do agente comunitário de saúde. Rev Eletr Enferm. 2010;12(1):28–36. https://doi.org/10.5216/ree.v12i1.9511. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliveira DT, Ferreira PJO, Mendonça LBA, Oliveira HS. Percepções do agente comunitário de saúde sobre sua atuação na Estratégia Saúde da Família. Cogitare Enferm. 2012;17(1):132–137. https://doi.org/10.5380/ce.v17i1.26386. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peres CRFB, Caldas AL, Júnior, Silva RF, Marin MJS. O agente comunitário de saúde frente ao processo de trabalho em equipe: facilidades e dificuldades. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2011;45(4):905–911. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342011000400016. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0080-62342011000400016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinheiro RL, Guanaes-Lorenzi C. Estud Psicol. 1. Vol. 19. Natal: 2014. Funções do agente comunitário de saúde no trabalho com redes sociais; pp. 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-294X2014000100007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pizo CA, Menegon NL. Análise ergonômica do trabalho e o reconhecimento científico do conhecimento gerado. Produçao. 2010;20(4):657–668. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-65132010005000058. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Queirós AAL, Lima LP. A institucionalização do trabalho do agente comunitário de saúde. Trab Educ Saude. 2012;10(2):257–281. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1981-77462012000200005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodrigues AAAO, Santos AM, Assis MMA. Agente comunitário de saúde: sujeito da prática em saúde bucal em Alagoinhas, Bahia. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2010;15(3):907–915. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232010000300034. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232010000300034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosa AJ, Bonfanti AL, Carvalho CS. O sofrimento psíquico de agentes comunitários de saúde e suas relações com o trabalho. Saude Soc. 2012;21(1):141–152. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-12902012000100014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakata KN, Mishima SM. Articulação das ações e interação dos agentes comunitários de saúde na equipe de Saúde da Família. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2012;46(3):665–672. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342012000300019. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0080-62342012000300019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santos LFB, David HMSL. Percepções do estresse no trabalho pelos agentes comunitários de saúde. [citado 19 out 2017];Rev Enferm UERJ. 2011 19(1):52–57. http://www.facenf.uerj.br/v19n1/v19n1a09.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt MLS, Neves TFS. O trabalho do agente comunitário de saúde e a política de atenção básica em São Paulo, Brasil. Cad Psicol Soc Trab. 2010;13(2):225–240. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1981-0490.v13i2p225-240. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silva MT, Salomão S, Alonso CMC, Matsubara S, Silva TM, Freitas ET, et al. Transformação do modelo de atenção em saúde mental e seus efeitos no processo de trabalho. In: Políticas públicas e processos de trabalho em saúde mental. Brasília (DF): Paralelo15; 2008. pp. 87–128. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silva TL, Dias EC, Ribeiro ECO. Interface. 38. Vol. 15. Botucatu: 2011. Saberes e práticas do agente comunitário de saúde na atenção à saúde do trabalhador; pp. 859–870. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-32832011005000035. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sossai LCF, Pinto IC, Mello DF. O agente comunitário de saúde (ACS) e a comunidade: percepções acerca do trabalho do ACS. Cienc Cuid Saude. 2010;9(2):228–237. https://doi.org/10.4025/cienccuidsaude.v9i2.11234. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Souza LJR, Freitas MCS. O agente comunitário de saúde: violência e sofrimento no trabalho a céu aberto. [citado 19 out 2017];Rev Baiana Saude Publica. 2011 35(1):96–109. http://files.bvs.br/upload/S/0100-0233/2011/v35n1/a2100.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomaz JBC. Interface. 10. Vol. 6. Botucatu: 2002. O agente comunitário de saúde não deve ser um “super-herói”; pp. 84–87. https://10.1590/S1414-32832002000100008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trapé CA, Soares CB. A prática educativa dos agentes comunitários de saúde à luz da categoria práxis. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2007;15(1):142–149. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692007000100021. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-11692007000100021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vilela RAG, Silva RC, Jackson JM., Filho Poder de agir e sofrimento: estudo de caso sobre agentes comunitários de saúde. Rev Bras Saude Ocup. 2010;35(122):289–302. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0303-76572010000200011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wai MFP, Carvalho AMP. O trabalho do agente comunitário de saúde: fatores de sobrecarga e estratégias de enfrentamento. [citado 19 out 2017];Rev Enferm UERJ. 2009 17(4):563–568. http://www.facenf.uerj.br/v17n4/v17n4a19.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zanchetta MS, Leite LS, Perreault M, Lefebvre H. Educação, crescimento e fortalecimento profissional do agente comunitário de saúde: estudo etnográfico. Online Braz J Nurs. 2005;4(3) https://doi.org/10.5935/1676-4285.200535. [Google Scholar]