Abstract

Background

Among the Plasmodium species that infect humans, adverse effects of P. falciparum and P. vivax have been extensively studied and reported with respect to poor outcomes particularly in first time mothers and in pregnant women living in areas with unstable malaria transmission. Although, other non-falciparum malaria infections during pregnancy have sometimes been reported, little is known about the dynamics of these infections during pregnancy.

Methods and findings

Using a quantitative PCR approach, blood samples collected from Beninese pregnant women during the first antenatal visit (ANV) and at delivery including placental blood were screened for Plasmodium spp. Risk factors associated with Plasmodium spp. infection during pregnancy were assessed as well as the relationships with pregnancy outcomes.

P. falciparum was the most prevalent Plasmodium species detected during pregnancy, irrespective either of parity, of age or of season during which the infection occurred. Although no P. vivax infections were detected in this cohort, P. malariae (9.2%) and P. ovale (5.8%) infections were observed in samples collected during the first ANV. These non-falciparum infections were also detected in maternal peripheral blood (1.3% for P. malariae and 1.2% for P. ovale) at delivery. Importantly, higher prevalence of P. malariae (5.5%) was observed in placental than peripheral blood while that of P. ovale was similar (1.8% in placental blood). Among the non-falciparum infected pregnant women with paired peripheral and placental samples, P. malariae infections in the placental blood was significantly higher than in the peripheral blood, suggesting a possible affinity of P. malariae for the placenta. However, no assoctiation of non-falciparum infections and the pregnancy outcomes was observed

Conclusions

Overall this study provided insights into the molecular epidemiology of Plasmodium spp. infection during pregnancy, indicating placental infection by non-falciparum Plasmodium and the lack of association of these infections with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Author summary

P. falciparum and P. vivax infections during pregnancy have been extensively studied. Meanwhile, the dynamics of other non-falciparum malaria infections during pregnancy is not well understood. We investigated the prevalence of Plasmodium spp. in samples collected from Beninese women early in pregnancy and at delivery using a quantitative PCR approach. Factors associated with Plasmodium spp. infection during pregnancy were assessed. P. falciparum was the most prevalent Plasmodium species detected. P. malariae and P. ovale infections were also detected early in pregnancy, and in the maternal peripheral and placental blood at delivery. Noteworthily, the high prevalence of P. malariae in the placenta of pregnant women with paired peripheral and placental samples, suggests a placental affinity of P. malariae during pregnancy. However, association of non-falciparum infections with pregnancy outcomes was not observed. This study provided insights into the molecular epidemiology of Plasmodium spp. infection during pregnancy, and highlighted the underestimated prevalence of non-falciparum infections in pregnancy-related malaria.

Introduction

Plasmodium falciparum is responsible for most cases of malaria during pregnancy and is linked with poor outcomes both among mothers and their babies [1,2]. Pregnant women are at heightened risk of infection despite pre-existing immunity acquired from previous exposures that protects against clinical malaria. This increased susceptibility to malaria during pregnancy has been related to the ability of P. falciparum infected erythrocytes to sequester in the placenta, inducing a placental inflammation that may lead to foetal growth alteration, stillbirth, and low birth weight (LBW) of the babies [3–5]. Futhermore, the proliferation of this new parasite phenotype can lead to severe maternal anemia [6,7].

Among the other Plasmodium parasites that infect humans (P. malariae, P. ovale, P. knowlesi and P. vivax), P. vivax has been reported in Asia and Latin America to have consequences during pregnancy, such as maternal anemia and LBW deliveries [8–12]. However, there is no evidence of P. vivax sequestration in the placenta [13]. The detection of P. malariae and P. ovale in pregnant women [14–16] has raised concerns about their possible involvement in pregnancy-associated malaria, although it is still unclear whether they display the placental tropism that P. falciparum does. Thus, geographical distribution of non-falciparum Plasmodia in West Africa, where P. falciparum is the most prevalent malaria species, and their involvement in the pathogenesis of pregnancy-associated malaria need to be documented. A PCR-based approach was used to better detect the non-falciparum malaria parasites due to their low parasite densities and the difficulty to accurately differentiate the species by morphological analysis using microscopy [17]. Only few studies reported the detection of non-falciparum malaria parasites in the placental blood [14,18,19].

Current efforts to prevent and control malaria during pregnancy using drug-based preventive treatment or vaccine strategies essentially target P. falciparum [20]. In this study, we investigated the prevalence and impact of Plasmodium spp. infection early in pregnancy (at first antenatal visit, before the introduction of prevention treatment), and at delivery in maternal peripheral and placental blood samples collected from a cohort of Beninese pregnant women across different malaria transmission seasons.

Methods

Ethics statement

The Strategies To Prevent Pregnancy Associated Malaria (STOPPAM) project was approved by the Comité Consultatif de Déontologie et d’Ethique of the Research Institute for Development (France) and the ethical committee of the Faculty of Health Science (University of Abomey-Calavi, Benin). All procedures complied with European and French national regulations. Written informed consent was given by participants who were all adults.

Study samples and DNA extraction

Samples used in this study were collected from pregnant women during the STOPPAM study conducted from 2008 to 2010 in Southern Benin. Details of the project have been reported elsewhere [21]. Briefly, 1037 pregnant women with a gestational age under 24 weeks were enrolled early in pregnancy, during their first antenatal visit (ANC), and followed-up monthly till delivery. Upon admission to the study, pregnant women were scheduled for supervised intermittent preventive treatment (IPTp) doses of sulfadoxime pyrimethamine (SP) uptake and insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) were provided to them. Ultrasound scan was performed for gestational age determination. Hemoglobin (Hb) level was determined at each visit and birth weight was recorded at delivery. Peripheral and placental blood samples were collected from delivering women. Thick and thin blood films were prepared from all samples for microscopical detection of Plasmodium spp. The blood smears were Giemsa-stained in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and examined by two independent microscopists. A third read was performed in case of discrepancies between the first two reads. Two hundred microliters of blood pellet were stored at -20°C for DNA extraction.

Based on the available data of the parameters to be considered in this study, 975 peripheral blood samples collected at enrolment, and 667 peripheral and 562 placental blood samples collected at delivery were analysed. No placenta histology data was available for this study. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from the frozen whole blood using the DNAeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen), as recommended by the manufacturer.

Plasmodium detection and quantification by real-time PCR

Species of Plasmodium spp. were detected in the whole blood DNA samples as described [22]. Briefly, a dual amplification was performed using Plasmodium-specific primers and probes previously published [23], and a detection primers/probes system for the human GAPDH gene GAPDH_Fw: CCTCCCGCTTCGCTCTCT, GAPDH_Rev: GCTGGCGACGCAAAAGA) and GapdhProbe: VIC-CCTCCTGTTCGACAGTCAGCCGC–MGBNFQ). GAPDH was used as an internal control gene to ensure that gDNA was successfully extracted. Plasmodium load was quantified by extrapolation of cycle thresholds (Ct) from a 6 fold standard curve of Plasmodium ring-infected erythrocytes. Samples without amplification (no Ct detected) were considered negative, and a density of 2 parasites/μl was assigned if amplification was observed out of the lower range of the standard curve (5 parasites/μl). A negative control with no DNA template was run in all reactions. This study benefited from a quality check program that was established to ensure correct performance of qPCR techniques between several laboratories including ours [22].

Plasmodium species (P. falciparum, P. malariae and P. ovale) were detected in a multiplex PCR reaction using species-specific forward and reverse primers, as well as specific probes, as described by Taylor et al. [22]. Specific primers targeting both P. ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri were used to amplify both variants of P. ovale [24]. For P. vivax detection, samples were pooled into group of 10 samples and screened as single PCR reaction. Amplification was performed using P. vivax specific primers and probe under the same conditions described above with few modifications. A total of 45 cycles was performed, and samples from any pool with amplifications have been individually screened for P. vivax detection.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using STATA software version 13. Prevalence of Plasmodium spp. infection at different time-points of collection were determined according to the age and the parity of the pregnant women. The influence of the season and intensity of malaria transmission were explored in relation to Plasmodium spp. infections among pregnant women. Months in the year were coded from 1 to 12 respectively for January to December. Dry seasons were defined as December-March and August (12, 1, 2, 3 and 8) while wet seasons were defined as April-July (4–7) and Sep-Nov (9–11), as previously described [21]. P. ovale and P. malariae infections were combined and analyzed as non-falciparum infections. Infections involving P. falciparum and non-falciparum parasites together were grouped as mixed infections. Furthermore, a multi-variable logistic regression model was used to assess the risk factors for P. falciparum, non-falciparum and mixed infections at different time points by controlling for potential confounders and using those without malaria infection as the reference group. In addition, an exploratory analysis was conducted at selected time-points to determine whether there was any association between Plasmodium spp. infections and primary pregnancy outcomes (LBW, prematurity and maternal anaemia), and active PM. For this analysis, groups of women presenting each outcome were considered, and the distribution of P. falciparum and non-falciparum in the detected infections early in pregnancy and at delivery was investigated in comparison to women with no malaria infection from the corresponding outcome group. Active microscopic PM was defined as confirmed Plasmodium spp. infection in placental blood by microscopy, and was found to be exclusively P. falciparum active PM. All statistical tests were conducted at 0.05 level of significance.

Results

Description of Plasmodium spp. infections detected by microscopy and qPCR

Parasites density generated from qPCR amplification of Plasmodium spp. as well as the parasite load of the infections determined by microscopy, are reported in Table 1. All the infections detected by microscopy were positive by qPCR screening. However, more than 60% of the infections detected by qPCR (61% at enrolment, 71% of peripheral and 63% of placental infections at delivery) have been missed by microscopy. It is important to note that none of the submicroscopic infections were associated with fever, suggesting an asymptomatic infection.

Table 1. Parasite load of infections detected by microscopy and PCR.

| Inclusion | Delivery | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral | Placental | ||

| Microscopy | |||

| Number | 162 | 70 | 73 |

| Mean ± SD | 1593.94 ± 4115.59 | 15265.89 ± 38755.36 | 23367.85 ± 73418.04 |

| Median (IQR) | 311 (153–1456) | 1142.5 (301–6957) | 1268 (287–8552) |

| Min—Max | 24–35745 | 14–258389 | 46–522183 |

| PCR | |||

| Number | 425 | 244 | 199 |

| Mean ± SD | 5629.71 ± 36441.53 | 13420.87 ± 76045.49 | 285903.2 ± 3850952 |

| Median (IQR) | 158.2 (24.71–1125.05) | 12.23 (2–284.15) | 26.98 (6.09–458.68) |

| Min—Max | 2–1995045.6 | 2–846618.82 | 2–54328425.79 |

SD = Standard Deviation; IQR = Interquartiles; Min = minimum; Max = maximum. Placental parasitaemia by PCR are shown to be indicative, as they are over-estimated from mature forms.

Prevalence of Plasmodium spp. infection early in pregnancy

Among samples collected early in pregnancy at the inclusion time-point, P. falciparum was the most prevalent Plasmodium species found in infected women. P. falciparum infection was detected in 39.3% of samples analysed either as a mono-species infection (29.6%) or involved in mixed infection (9.7%) with other Plasmodium species (Table 2). Infections involving P. malariae and P. ovale were detected respectively in 9.2% and 5.7% of samples. It appeared that infections with P. malariae early in pregnancy were more prevalent than those involving P. ovale (Chi square test, p = 0.001). When the analysis was performed considering the non-falciparum Plasmodium parasites as mono-species infection, a reverse trend was observed. Indeed, the prevalence of P. malariae mono-infection (1.4%) was significantly lower as compared to P. ovale mono-infection (2.3%) (Chi square test, p < 0.0001). Mixed infections involving P. falciparum and non-falciparum were detected in 98 (10.1%) samples as reported in Table 2. Infection with P. vivax was not detected in samples analysed in this work.

Table 2. Plasmodium spp. infections in Beninese pregnant women.

| Inclusion | Delivery | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral | Placental | ||

| Number of pregnant women | 975 | 667 | 562 |

| Number of P. falciparum infections | 383 | 231 | 180 |

| Prevalence (95% CI) | 39.3% (36.3–42.4) | 34.6% (31.1–38.3) | 32.0% (28.3–36.0) |

| Number of P. malariae infections | 90 | 9 | 31 |

| Prevalence (95% CI) | 9.2% (7.6–11.2) | 1.3% (0.7–2.6) | 5.5% (3.9–7.7) |

| Number of P. ovale infections | 56 | 8 | 10 |

| Prevalence (95% CI) | 5.7% (4.4–7.4) | 1.2% (0.6–2.4) | 1.8% (1.0–3.3) |

| Mono-infections, no. (%) | |||

| P. falciparum | 289 (29.6) | 227 (34.0) | 162 (28.8) |

| P. malariae | 14 (1.4) | 5 (0.7) | 15 (2.7) |

| P. ovale | 22 (2.3) | 8 (1.2) | 2 (0.4) |

| Mixed infections, no. (%) | |||

| P. falciparum, P. malariae | 64 (6.6) | 4 (0.6) | 12 (2.1) |

| P. falciparum, P. ovale | 22 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.7) |

| P. falciparum, P. malariae, P. ovale | 8 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.4) |

| P. malariae, P. ovale | 4 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.4) |

Relation of parity and age with P. falciparum and non-falciparum infections early in pregnancy

The prevalence of Plasmodium spp. infections at enrolment was analysed according to the parity of the women and their age (Table 3). The prevalence of P. malariae and P. ovale infection was combined as non-falciparum and P. falciparum infections were analysed as mono-infection while mixed infections were considered as a separate group. P. falciparum infection occurring early in pregnancy was significantly associated with parity (Chi square test, p = 0.005) and age (Chi square test, p < 0.0001), resulting in higher prevalence of P. falciparum infection in primigravid and younger women. No relation was observed when non-falciparum infections at enrolment were compared with parity and age of the women.

Table 3. Prevalence of Plasmodium spp. infections during pregnancy according to parity and age of the woman, and the season of sample collection.

| Inclusion, no. (%) | Peripheral Blood, no. (%) | Placental Blood, no. (%) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pf | P * | non-Pf | P * | Mixed | P * | Pf | P * | non-Pf | P * | Mixed | P * | Pf | P * | non-Pf | P * | Mixed | P * | ||

| Parity | 0.005 | 0.75 | 0.17 | 0.92 | 0.55 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.98 | 0.94 | ||||||||||

| Primiparae | 68 (38.4) | 8 (4.5) | 22 (12.4) | 38 (33.6) | 3 (2.7) | 2 (1.8) | 31 (34.4) | 3 (3.3) | 3 (3.3) | ||||||||||

| Multiparae | 221 (27.7) | 32 (4.0) | 72 (9.0) | 189 (34.1) | 10 (1.8) | 2 (0.4) | 131 (27.8) | 16 (3.4) | 15 (3.2) | ||||||||||

| Age | 0.000 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.73 | 0.000 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.92 | ||||||||||

| < 18 years | 16 (43.2) | 3 (8.1) | 4 (10.8) | 11 (39.3) | 1 (3.6) | 2 (7.1) | 11 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.6) | ||||||||||

| 18–20 years | 75 (42.6) | 8 (4.5) | 22 (12.5) | 45 (38.8) | 3 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 34 (34.0) | 6 (6.0) | 3 (3.0) | ||||||||||

| 21–24 years | 53 (29.6) | 7 (3.9) | 18 (10.1) | 32 (28.1) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (21.1) | 2 (2.1) | 4 (4.2) | ||||||||||

| 25 years+ | 139 (24.4) | 21 (3.7) | 49 (8.6) | 134 (33.8) | 8 (2.0) | 2 (0.51) | 91 (27.3) | 11 (3.3) | 10 (3.0) | ||||||||||

| Season** | 0.47 | 0.75 | 0.04 | 0.51 | 0.80 | 0.31 | 0.43 | 0.008 | 0.12 | ||||||||||

| Other months | 119 (30.6) | 17 (4.4) | 38 (9.8) | 107 (32.4) | 7 (2.1) | 3 (0.9) | 70 (26.3) | 15 (5.6) | 5 (1.9) | ||||||||||

| April-July | 50 (26.0) | 6 (3.1) | 10 (5.2) | 84 (34.9) | 5 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 67 (31.5) | 1 (0.5) | 11 5.2) | ||||||||||

| Sep-Nov | 20 (30.5) | 17 (4.3) | 46 (11.7) | 36 (38.7) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 25 (30.9) | 3 (3.7) | 2 (2.5) | ||||||||||

Pf = Plasmodium falciparum; non-Pf = non-falciparum

*P value

**Season of enrolment and season of delivery for peripheral and placental blood

Sub-microscopic detection of non-falciparum infection at delivery

Plasmodium spp. infection at delivery was assessed in the peripheral and placental blood samples. P. falciparum was, by far, the most prevalent Plasmodium species detected in maternal peripheral (34.6%) and placental blood (32%) samples (Table 2). Plasmodium spp. infections involving P. malariae and P. ovale at delivery were detected respectively in 1.3% and 1.2% of maternal peripheral blood samples, resulting in non significant difference in the prevalence of both parasites in the maternal peripheral blood samples at delivery. Only P. falciparum and P. malariae mixed infections were detected in 4 out of 667 maternal peripheral blood samples. Remarkably, in the placental samples, the prevalence of P. malariae infections (5.5%) was significantly higher than those involving P. ovale (1.8%) (Chi square test, p < 0.0001). Mixed infections comprising P. falciparum/P. malariae; P. falciparum/P. ovale; P. falciparum/P. malariae/P. ovale and P. malariae/P. ovale were respectively detected in 12 (2.1%); 4 (0.7%); 2 (0.4%) and 2 (0.4%) placental samples. Most importantly, mono-infections with P. malariae were detected in the placenta of 15 women (2.7%), at a higher prevalence compared to that of P. ovale (0.4%) (Chi square test, p < 0.0001). However, this difference was not observed in the maternal peripheral samples (0.7% for P. malariae and 1.2% for P. ovale). As at enrolment, no P. vivax infection was detected in the samples collected at delivery.

In the maternal peripheral blood samples at delivery, neither P. falciparum nor non-falciparum infections were associated with parity or age of the women. However, younger mothers were the most exposed to mixed infections (p < 0.001), while no difference was observed in the prevalence of P. falciparum and non-falciparum infections over different age groups and the parity of the women (Table 3).

P. falciparum infection in placental blood samples was significantly associated with the women’s age (p = 0.025), suggesting that younger pregnant women are more susceptible to develop a placental P. falciparum-malaria although being co-infected with other Plasmodium species. It is worth noting that although not statistically significant, primigravid women had higher prevalence of P. falciparum than multigravid women.

Influence of seasons on Plasmodium spp. infection during pregnancy

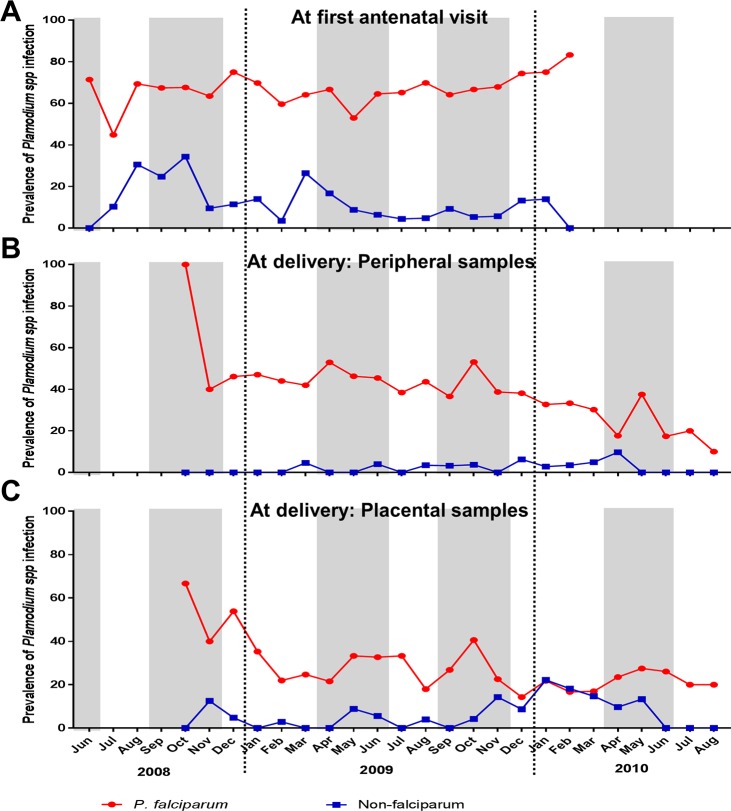

The prevalence of P. falciparum and non-falciparum infections was analysed according to seasons corresponding to the blood sampling. The monthly prevalences of P. falciparum and non-falciparum infections at enrolment and at delivery are shown in Fig 1. Over the period of sample collection in early pregnancy stage, the monthly prevalence of P. falciparum infections (range, 45%–84%) was significantly higher than non-falciparum infections (range, 0%–34%) (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test, p < 0.0001). This differential monthly prevalence of P. falciparum and non-falciparum infections was maintained at delivery with a high prevalence of P. falciparum infections in peripheral and placental blood samples (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test, p < 0.0001 for both peripheral and placental samples). However, over three successive months (January to March 2010), similar prevalence values of P. falciparum and non-falciparum placental infections were observed. Of note, Plasmodium spp. infection early in pregnancy clearly appeared to be high regardless of season and irrespective to the Plasmodium species. In these samples collected at enrolment, no distinct pattern of overlapping peaks of Plasmodium spp. prevalence and the rainy seasons was observed, although a significant increase of mixed infections (p = 0.045) was detected between September and November (Table 3). However, season was not a risk factor for Plasmodium spp. infection at enrolment (Tables 4 and 5, S1 Table).

Fig 1. Monthly prevalence of P. falciparum and non-falciparum infections in Beninese pregnant women.

The prevalence of P. falciparum (in red) and non-falciparum (in blue) infections detected in pregnant at the enrollment (A) and at delivery in the peripheral (B) and placental (C) blood samples are presented. Periods covered June 2008 to February 2010 corresponding to the recruitment of the pregnant women and October 2008 to August 2010 for the data collection at delivery.

Table 4. Risk factors for P. falciparum malaria infections at enrolment.

| Risk factors | Crude OR | p value | *Adjusted OR | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | ||||

| Gravidity | ||||

| Primiparae | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - |

| Multiparae | 0.61 (0.44–0.86) | 0.005 | 0.99 (0.65–1.52) | 0.968 |

| Gestational age | ||||

| 1st trimester (<13 weeks) | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - |

| 2nd trimester (13–26 weeks) | 1.37 (0.98–1.92) | 0.069 | 1.23 (0.88–1.75) | 0.228 |

| 3rd trimester (>26 weeks) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Age | ||||

| < 18 years | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - |

| 18–20 years | 0.97 (0.48–1.99) | 0.944 | 1.00 (0.48–2.11) | 0.995 |

| 21–24 years | 0.55 (0.27–1.14) | 0.108 | 0.58 (0.27–1.27) | 0.173 |

| 25 years+ | 0.42 (0.22–0.84) | 0.013 | 0.45 (0.21–0.98) | 0.044 |

| Season of enrolment | ||||

| Other months | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - |

| April-July | 0.80 (0.54–1.18) | 0.257 | 0.84 (0.56–1.25) | 0.396 |

| Sep-Nov | 0.99 (0.73–1.35) | 0.967 | 1.02 (0.74–1.39) | 0.913 |

OR = Odd ratio

*Crude ORs for parity, gestational age, season of enrolment are adjusted for all other Covariates (parity, gestational age, mother’s age, season of enrolment).

Table 5. Risk factors for P. falciparum and non-falciparum malaria mixed infections at enrolment.

| Risk factors | Crude OR | p vlaue | *Adjusted OR | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | ||||

| Gravidity | ||||

| Primiparae | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - |

| Multiparae | 0.70 (0.42–1.16) | 0.167 | 0.80 (0.42–1.51) | 0.491 |

| Gestational age | ||||

| 1st trimester (<13 weeks) | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - |

| 2nd trimester (13–26 weeks) | 1.02 (0.61–1.70) | 0.934 | 0.96 (0.57–1.61) | 0.873 |

| 3rd trimester (>26 weeks) | 9.71 (1.30–72.56) | 0.027 | 8.99 (1.18–68.17) | 0.034 |

| Age | ||||

| < 18 years | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - |

| 18–20 years | 1.18 (0.38–3.65) | 0.776 | 1.35 (0.42–4.33) | 0.616 |

| 21–24 years | 0.92 (0.29–2.90) | 0.89 | 1.05 (0.31–3.56) | 0.933 |

| 25 years+ | 0.78 (0.26–2.29) | 0.647 | 0.99 (0.29–3.36) | 0.987 |

| Season of enrolment | ||||

| Other months | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - |

| April-July | 0.51 (0.25–1.04) | 0.065 | 0.52 (0.25–1.08) | 0.080 |

| Sep-Nov | 1.22 (0.78–1.92) | 0.389 | 1.20 (0.76–1.90) | 0.445 |

OR = Odd ratio

*Crude ORs for parity, gestational age, season of enrolment are adjusted for all other Covariates (parity, gestational age, mother’s age, season of enrolment).

At delivery, no association between the prevalence of maternal peripheral Plasmodium spp or P. falciparum infections and season was observed (Table 6). Conversely, in placental blood, a significantly higher number of non-falciparum infections samples was detected during the dry season (p = 0.008, Table 3) as compared to the wet season, when the risk of non-falciparum infections in placenta blood was significantly higher (Adjusted OR, 0.07; p = 0.012, S2 Table), and these infections were mostly caused by P. malariae (S3 Table). Unlike early in pregnancy, most peaks in the monthly prevalence of P. falciparum and non-falciparum infection profiles in both peripheral and placental blood samples at delivery matched with the rainy seasons (Fig 1).

Table 6. Risk factors for P. falciparum malaria infections at delivery.

| Delivery | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral Blood | Placental Blood | |||||||

| Risk factors | Crude OR | p value | *Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p value | Crude OR | p value | *Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p value |

| Parity | ||||||||

| Primiparae | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - |

| Multiparae | 1.02 (0.67–1.57) | 0.921 | 1.14 (0.65–2.00) | 0.642 | 0.73 (0.45–1.18) | 0.2 | 0.94 (0.49–1.81) | 0.849 |

| Term at delivery | ||||||||

| Premature (<37 weeks) | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - |

| Early term (37–38 weeks) | 0.75 (0.41–1.38) | 0.361 | 0.72 (0.39–1.33) | 0.290 | 1.60 (0.74–3.48) | 0.234 | 1.67 (0.75–3.70) | 0.208 |

| Full term (39–40 weeks) | 0.53 (0.31–0.92) | 0.023 | 0.54 (0.31–0.94) | 0.030 | 0.73 (0.35–1.52) | 0.405 | 0.83 (0.39–1.76) | 0.633 |

| Late term (41 weeks) | 0.76 (0.39–1.48) | 0.42 | 0.79 (0.40–1.55) | 0.488 | 0.68 (0.28–1.65) | 0.388 | 0.74 (0.30–1.85 | 0.52 |

| Post term (> = 42 weeks) | 0.76(0.33–1.74) | 0.519 | 0.81 (0.35–1.88) | 0.620 | 1.30 (0.48–3.57) | 0.607 | 1.34 (0.47–3.81) | 0.589 |

| Age | ||||||||

| < 18 years | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - |

| 18–20 years | 0.98 (0.42–2.28) | 0.962 | 0.92 (0.37–2.29) | 0.852 | 0.52 (0.20–1.31) | 0.163 | 0.62 (0.22–1.73) | 0.362 |

| 21–24 years | 0.60 (0.25–1.43) | 0.25 | 0.57 (0.22–1.49) | 0.252 | 0.27 (0.10–0.70) | 0.008 | 0.31 (0.10–0.93) | 0.037 |

| 25 years+ | 0.79 (0.36–1.74) | 0.558 | 0.72 (0.28–1.88) | 0.503 | 0.38 (0.16–0.90) | 0.028 | 0.44 (0.15–1.32) | 0.143 |

| Season of delivery | ||||||||

| Other months | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - | [Reference] | - |

| April-July | 1.12 (0.78–1.58) | 0.543 | 1.14 (0.80–1.63) | 0.475 | 1.28 (0.86–1.91) | 0.217 | 1.37 (0.91–2.07) | 0.136 |

| Sep-Nov | 1.32 (0.82–2.12) | 0.259 | 1.35 (0.83–2.20) | 0.228 | 1.25 (0.72–2.16) | 0.422 | 1.45 (0.82–2.56) | 0.198 |

OR = Odd ratio

*Crude ORs for parity, gestational age, season of delivery are adjusted for all other Covariates (parity, gestational age, mother’s age, season of enrolment).

Other risk factors of Plasmodium spp. infection early in pregnancy and at delivery

Factors associated with P. falciparum and non-falciparum malaria infection in pregnant women were assessed in samples collected early in pregnancy and at delivery. Parity has been identified as a risk factor of P. falciparum infection early in pregnancy. Indeed, relative to primigravid women, multigravid (crude OR, 0.52; p = 0.005) women had a significantly lower risk of P. falciparum infection early in pregnancy (Table 4). However, this parity-related effect disappeared when the analysis was adjusted with others covariates (Table 4). Interestingly, women older than 25 have lower risk of P. falciparum infection early in pregnancy (Adjusted OR, 0.45; p = 0.044). Parity, gestational age and age of the women did not significantly influence non-falciparum infections at enrolment, probably due to the limited size of this group (S1 Table). Strikingly, a greater risk of mixed infections was evident late in pregnancy, even though gestational age was not associated with P. falciparum and non-falciparum infections when analysed separately (Table 5, S1 Table).

At delivery, P. falciparum infection in maternal peripheral blood was a risk factor for premature delivery (Adjusted OR, 0.54; p = 0.03, Table 6). Women older than 21 presented a lower risk of P. falciparum placental infection than younger women.

Plasmodium spp. infection and pregnancy outcomes

The relationships between P. falciparum, non-falciparum and mixed infection at enrolment and at delivery, and poor pregnancy outcomes such as prematurity, LBW and maternal anaemia at delivery were investigated (Tables 7 and 8). The proportion of women who developed each outcome from P. falciparum, non-falciparum and mixed infections groups was compared to the group of women with no malaria infection at delivery. Number of pregnant women with malaria infection in the placental blood determined by microscopy was significantly higher in women who were infected early in pregnancy with either non-falciparum or P. falciparum (p = 0.048 and p = 0.006, respectively), as compared to uninfected women at enrolment (Table 7). Noteworthily, only P. falciparum infections were significantly associated to maternal anemia at enrolment (S4 Table). No relationship was observed between non-falciparum, P. falciparum and mixed infections at enrolment, and the occurrence of LBW and maternal anemia at delivery. Nevertheless, mixed infection at enrolment was significantly related to premature delivery (p = 0.037), and a similar trend was found for P. falciparum infected mothers at enrolment and at delivery.

Table 7. Association of Plasmodium spp. infections at enrolment with pregnancy outcomes.

| No malaria, no. (%)* | Non-falciparum, no. (%) | P value** | P. falciparum, no. (%) | P value** | Mixed infection, no. (%) | P value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active PM (n = 73) | 31 (9.0) | 5 (21.7) | 0.048 | 33 (17.1) | 0.006 | 4 (6.9) | 0.593 |

| Low birth weight (n = 102) | 52 (11.0) | 4 (11.8) | 0.893 | 37 (14.4) | 0.177 | 9 (12.0) | 0.802 |

| Anemia at delivery (n = 299) | 164 (43.6) | 11 (45.8) | 0.832 | 104 (50.7) | 0.100 | 20 (35.1) | 0.225 |

| Prematurity (n = 61) | 26 (5.7) | 3 (8.8) | 0.455 | 23 (9.2) | 0.076 | 9 (12.2) | 0.037 |

* Proportion of women who developed the corresponding outcome from each type of infection group is presented. Numbers for this analysis are detailed in S5 Table.

**P. falciparum, non-falciparum and mixed infections groups were compared with no malaria infection

Table 8. Association of Plasmodium spp. infections at delivery with pregnancy outcomes.

| No malaria, no. (%)* | Non-falciparum, no. (%) | P value** | P. falciparum, no. (%) | P value** | Mixed infection, no. (%) | P value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PERIPHERAL BLOOD | |||||||

| Active PM (n = 66) | 8 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.633 | 57 (29.1) | 0.000 | 1 (33.3) | 0.001 |

| Low birth weight (n = 69) | 39 (9.4) | 1 (8.3) | 0.897 | 28 (12.7) | 0.208 | 1 (25.0) | 0.293 |

| Anemia at delivery (n = 273) | 172 (44.2) | 7 (53.9) | 0.492 | 91 (45.5) | 0.767 | 3 (75.0) | 0.218 |

| Prematurity (n = 53) | 26 (6.3) | 3 (8.8) | 0.366 | 23 (10.7) | 0.060 | 1 (25.0) | 0.135 |

| PLACENTAL BLOOD | |||||||

| Active PM (n = 67) | 10 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.458 | 52 (32.1) | 0.000 | 5 (27.8) | 0.000 |

| Low birth weight (n = 56) | 36 (10.1) | 1 (5.3) | 0.488 | 18 (11.4) | 0.670 | 1 (5.6) | 0.525 |

| Anemia at delivery (n = 229) | 143 (42.8) | 9 (50.0) | 0.549 | 70 (47.3) | 0.361 | 7 (43.8) | 0.941 |

| Prematurity (n = 34) | 20 (5.7) | 2 (10.5) | 0.382 | 10 (6.4) | 0.755 | 2 (11.1) | 0.340 |

Non-falciparum infections in paired peripheral and placental samples

Among pregnant women with non-falciparum infection at delivery, 38 (with P. malariae infection) and 18 (with P. ovale infection) paired peripheral and placental samples were analysed. P. malariae infections rate in the placental blood was significantly higher than in the peripheral samples (Fisher's exact test, p < 0.0001) (Table 9). A similar trend was observed when mono-infection with P. malariae was considered (Table 10). In a different way, distribution of P. ovale infections was similar in the peripheral and placental blood samples (S8 Table). However, when mono-infection with P. ovale was considered, more infections were detected in peripheral blood than in placental blood samples (Fisher's exact test, p < 0.0001) (S9 Table).

Table 9. Paired peripheral and placental samples of all P. malariae involved infections.

| Placental blood | Total (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | |||

| Peripheral blood | Negative | 0 | 29 | 29 (76.3) |

| Positive | 7 | 2 | 9 (23.7) | |

| Total (%) | 7 (18.4) | 31 (81.6) | ||

Table 10. Paired peripheral and placental samples of mono-infection of P. malariae.

| Placental blood | Total (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | |||

| Peripheral blood | Negative | 0 | 14 | 14 (73.7) |

| Positive | 4 | 1 | 5 (26.3) | |

| Total (%) | 4 (21.1) | 15 (79.0) | ||

Discussion

The geographical distribution of non-falciparum malaria parasites is under re-evaluation due to continued development of more sensitive PCR-based diagnostic tools. Traditionally cited as uncommon causes of malaria in many African areas, P. malariae, P. ovale and P. vivax infections have been reported at increasing prevalences [25–29]. Common features of non-falciparum infections include chronicity, low parasite density, asymptomatic and multiple species infection [30]. In West Africa, these plasmodial infections have been detected in children [31,32], adults [32,33], and pregnant women [14–16]. However, the prevalence of non-falciparum infections among different populations remains undocumented in many West African countries, including Benin. We described the prevalence of different species of Plasmodium parasites that infect Beninese women during pregnancy, and confirm the presence of infections with P. ovale and P. malariae parasites among West African pregnant women, as previously reported [16]. Overall, P. ovale and P. malariae parasites were detected either as mono-infections, as dual infections or as mixed infections with P. falciparum in 3.7%, 0.4% and 9.3%, respectively, of pregnant women at first ANV, leading to a prevalence of non-falciparum malaria infection of 13.4%. This prevalence is higher than in other West African countries (Ghana, 0.96%; Mali, 3.81%; Gambia, 0.17% and Burkina Faso, 0.72%) [16], but close to that (9.4%) of Cameroonian pregnant women [14]. This high prevalence of non-falciparum infection might be explained by differences in study design and different epidemiological features, as well as by the highly sensitive PCR approach used [14,16].

No P. vivax infection was detected in pregnant women, although circulating P. vivax among non-pregnant Beninese was reported [34]. The authors who reported this presence of P. vivax selected a group based on sero-reactivity to rPvMSP1 and rPvCSP1 antigens [34], thus it is difficult to estimate the prevalence of P. vivax in a non-biased population.

Both at enrolment and delivery, P. falciparum was the most prevalent Plasmodium spp. supporting the general consensus that P. falciparum is responsible for most cases of pregnancy-related malaria. Indeed, P. falciparum infections either at enrolment or at delivery were related to active microscopically detectable PM, as reported [1,35]. At enrolment, prevalence of P. falciparum infection decreased with increasing age or parity, confirming the age- and parity-related susceptibility to malaria during pregnancy. Strikingly, this parity effect disappeared at delivery, suggesting a similar risk of P. falciparum infection for all pregnant women in the last weeks of pregnancy. This lack of parity-related susceptibility at delivery might be the effect of IPTp, which clears subsequent infections, but fails to protect against re-infections after the second dose of SP [36,37]. In fact, we have previously shown that uptake of IPT-SP doses in our cohort allowed to reduce the prevalence of malaria infections considerably, however re-infections were observed later in the follow-up, probably due to the decrease of the drug concentration in the blood over the time, as most of these re-infections were recrudescences [36]. An increased risk of placental infection when the first IPT-SP dose (and consequently, the second) was administered early in pregnancy [38] has been also demonstrated. These observations suggest that SP may significantly reduce parasite densities without clearing them up completely, probably also because of a level of parasite resistance to SP, even in West Africa where the mutant profiles differ from those in the East with a lower frequency of the quintuple mutants [36,39]. Our study was conducted at a time when Benin recommended two doses of SP for IPTp, that were initiated comparatively early in pregnancy (20–24 weeks gestational age), thus leaving a large part of the third trimester of pregnancy unprotected. Indeed, women were encouraged after the first ANV to use multiple malaria prevention tools, mainly IPTp and long-lasting insecticide treated nets, possibly obscuring the parity-related susceptibility of infection late in pregnancy. Furthermore, younger mothers still remained susceptible to P. falciparum placental infection which may persist from early pregnancy, since no age-related difference was observed in the prevalence of infection in maternal peripheral blood. This finding highlights the influence of IPTp, by reducing the prevalence of infection until delivery. On the other hand, this observation may also suggest that most Plasmodium spp. infections at delivery derived from new infections in IPTp-implemented areas.

A major feature of our data is the detailed description of non-falciparum malaria infection both early in pregnancy and at delivery, both in maternal peripheral and placental blood. In previous reports, P. malariae and P. ovale have been detected in placentas and placental blood samples [14,40] from pregnant women in Uganda and Cameroon. No evidence of sequestration in deep vascular beds was reported. This study revealed a relatively high prevalence of P. malariae and P. ovale in pregnant women at delivery, either as mixed or as mono-infections. The higher prevalence of P. malariae in the placental compartment compared with peripheral blood suggests a potential affinity of P. malariae for the placenta. This hypothesis requires further investigations to characterize P. malariae parasites, and to demonstrate any association with placental pathology.

Plasmodial infection during pregnancy occurs throughout the year in our study area where malaria transmission is continuous (Fig 1). Although season of enrolment was not a risk factor for Plasmodium spp. infection, the prevalence of mixed-Plasmodium infections was lower during the first rainy season. Similarly, a lower prevalence of non-falciparum, mainly P. malariae, was detected during both rainy seasons as compared to the dry season. At delivery, prevalence of non-falciparum placental blood infection was lower in the first rainy season. One limitation of this study is the lack of contemporary rainfall and entomological data at sample collection. Such information would allow to better define rainy and dry seasons, and to better correlate parasite prevalence and malaria transmission. This study showed that epidemiology of malaria early in pregnancy is not strictly dictated by transmission fluctuations, contrary to non-pregnant populations [41]. Some infections may simply emerge from asymptomatic (low-density) infections acquired early in pregnancy or before. Our findings contrast with reports from pregnant women in other areas where the rainy season was associated with an increased risk of malaria infection [42,43].

Many studies have demonstrated the role of P. falciparum in PM through the placental sequestration of P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes [44–46]. Here, non-falciparum and P. falciparum, but not mixed infections early in pregnancy were associated with placental blood infection at delivery. Women infected with non-falciparum at enrolment may be more susceptible to P. falciparum later in pregnancy, leading to PM at delivery. However, longitudinal studies are needed to investigate such putative role of early non-falciparum infection in promoting P. falciparum PM. Mixed infections at delivery displayed distinct relationships with gestational age, enrolment season, and age of the women. Although size differences of the groups may partly account for these observations, the contribution of non-falciparum parasites to the pathology and modulation of the immune response during co-infection with P. falciparum needs to be addressed.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

OR = Odd ratio; *Crude ORs for parity, gestational age, season of enrolment are adjusted for all other Covariates (parity, gestational age, mother’s age, season of enrolment)

(DOCX)

OR = Odd ratio; *Crude ORs for parity, gestational age, season of delivery are adjusted for all other Covariates (parity, gestational age, mother’s age, season of enrolment).

(DOCX)

*P value.

(DOCX)

* Proportion of women who developed the corresponding outcome from each type of infection group is presented. **P. falciparum, non-falciparum and mixed infections groups were compared with no malaria infection.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the women who participated in the study and those involved in the STOPPAM project. The cohort study in Benin was part of the STOPPAM project, “Strategies To Prevent Pregnancy-Associated Malaria”. We thank all the medical staffs of Akodeha, Come Central and Ouedeme Pedah health centers, for their valuable contributions.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

STOPPAM is collaborative project supported by the European 7th Framework Programme (contract no. 200889). JYAD is supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. RAA is supported by PhD studentship from WHO/TDR postgraduate program in Implementation Science. AMo was supported by PhD studentship from Islamic Development Bank. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Desai M, ter Kuile FO, Nosten F, McGready R, Asamoa K, Brabin B, et al. Epidemiology and burden of malaria in pregnancy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7: 93–104. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70021-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brabin BJ. An analysis of malaria in pregnancy in Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 1983;61: 1005 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brabin BJ, Kalanda BF, Verhoeff FH, Chimsuku LH, Broadhead RL. Risk factors for fetal anaemia in a malarious area of Malawi. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2004;24: 311–321. doi: 10.1179/027249304225019136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Umbers AJ, Boeuf P, Clapham C, Stanisic DI, Baiwog F, Mueller I, et al. Placental malaria-associated inflammation disturbs the insulin-like growth factor axis of fetal growth regulation. J Infect Dis. 2011;203: 561–569. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wort UU, Hastings I, Mutabingwa TK, Brabin BJ. The impact of endemic and epidemic malaria on the risk of stillbirth in two areas of Tanzania with different malaria transmission patterns. Malar J. 2006;5: 89 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matteelli A, Donato F, Shein A, Muchi JA, Leopardi O, Astori L, et al. Malaria and anaemia in pregnant women in urban Zanzibar, Tanzania. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;88: 475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nosten F, ter Kuile F, Maelankirri L, Decludt B, White NJ. Malaria during pregnancy in an area of unstable endemicity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85: 424–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ter Kuile FO, Rogerson SJ. Plasmodium vivax infection during pregnancy: an important problem in need of new solutions. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2008;46: 1382–1384. doi: 10.1086/586744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rijken MJ, McGready R, Boel ME, Poespoprodjo R, Singh N, Syafruddin D, et al. Malaria in pregnancy in the Asia-Pacific region. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12: 75–88. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70315-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Sanchez E, Vargas M, Piccolo C, Colina R, Arria M, et al. Pregnancy outcomes associated with Plasmodium vivax malaria in northeastern Venezuela. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74: 755–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brutus L, Santalla J, Schneider D, Avila JC, Deloron P. Plasmodium vivax malaria during pregnancy, Bolivia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19: 1605–1611. doi: 10.3201/eid1910.130308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bardají A, Martínez-Espinosa FE, Arévalo-Herrera M, Padilla N, Kochar S, Ome-Kaius M, et al. Burden and impact of Plasmodium vivax in pregnancy: A multi-centre prospective observational study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11: e0005606 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Souza RM, Ataíde R, Dombrowski JG, Ippólito V, Aitken EH, Valle SN, et al. Placental histopathological changes associated with Plasmodium vivax infection during pregnancy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7: e2071 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker-Abbey A, Djokam RRT, Eno A, Leke RFG, Titanji VPK, Fogako J, et al. Malaria in pregnant Cameroonian women: the effect of age and gravidity on submicroscopic and mixed-species infections and multiple parasite genotypes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72: 229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mockenhaupt FP, Rong B, Till H, Thompson WN, Bienzle U. Short report: increased susceptibility to Plasmodium malariae in pregnant alpha(+)-thalassemic women. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64: 6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams J, Njie F, Cairns M, Bojang K, Coulibaly SO, Kayentao K, et al. Non-falciparum malaria infections in pregnant women in West Africa. Malar J. 2016;15: 53 doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1092-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mueller I, Zimmerman PA, Reeder JC. Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale—the “bashful” malaria parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2007;23: 278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arango EM, Samuel R, Agudelo OM, Carmona-Fonseca J, Maestre A, Yanow SK. Molecular detection of malaria at delivery reveals a high frequency of submicroscopic infections and associated placental damage in pregnant women from northwest Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89: 178–183. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGregor IA, Wilson ME, Billewicz WZ. Malaria infection of the placenta in The Gambia, West Africa; its incidence and relationship to stillbirth, birthweight and placental weight. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1983;77: 232–244. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(83)90081-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chêne A, Houard S, Nielsen MA, Hundt S, D’Alessio F, Sirima SB, et al. Clinical development of placental malaria vaccines and immunoassays harmonization: a workshop report. Malar J. 2016;15: 476 doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1527-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huynh B-T, Fievet N, Gbaguidi G, Borgella S, Mévo BG, Massougbodji A, et al. Malaria associated symptoms in pregnant women followed-up in Benin. Malar J. 2011;10: 72 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor SM, Mayor A, Mombo-Ngoma G, Kenguele HM, Ouédraogo S, Ndam NT, et al. A quality control program within a clinical trial Consortium for PCR protocols to detect Plasmodium species. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52: 2144–2149. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00565-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandeu MM, Moussiliou A, Moiroux N, Padonou GG, Massougbodji A, Corbel V, et al. Optimized Pan-species and speciation duplex real-time PCR assays for Plasmodium parasites detection in malaria vectors. PloS One. 2012;7: e52719 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shokoples SE, Ndao M, Kowalewska-Grochowska K, Yanow SK. Multiplexed real-time PCR assay for discrimination of Plasmodium species with improved sensitivity for mixed infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47: 975–980. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01858-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oguike MC, Betson M, Burke M, Nolder D, Stothard JR, Kleinschmidt I, et al. Plasmodium ovale curtisi and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri circulate simultaneously in African communities. Int J Parasitol. 2011;41: 677–683. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dinko B, Oguike MC, Larbi JA, Bousema T, Sutherland CJ. Persistent detection of Plasmodium falciparum, P. malariae, P. ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri after ACT treatment of asymptomatic Ghanaian school-children. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2013;3: 45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2013.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Betson M, Sousa-Figueiredo JC, Atuhaire A, Arinaitwe M, Adriko M, Mwesigwa G, et al. Detection of persistent Plasmodium spp. infections in Ugandan children after artemether-lumefantrine treatment. Parasitology. 2014;141: 1880–1890. doi: 10.1017/S003118201400033X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernabeu M, Gomez-Perez GP, Sissoko S, Niambélé MB, Haibala AA, Sanz A, et al. Plasmodium vivax malaria in Mali: a study from three different regions. Malar J. 2012;11: 405 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fru-Cho J, Bumah VV, Safeukui I, Nkuo-Akenji T, Titanji VPK, Haldar K. Molecular typing reveals substantial Plasmodium vivax infection in asymptomatic adults in a rural area of Cameroon. Malar J. 2014;13: 170 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutherland CJ. Persistent Parasitism: The Adaptive Biology of Malariae and Ovale Malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2016;32: 808–819. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2016.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Browne EN, Frimpong E, Sievertsen J, Hagen J, Hamelmann C, Dietz K, et al. Malariometric update for the rainforest and savanna of Ashanti region, Ghana. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2000;94: 15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trape JF, Rogier C, Konate L, Diagne N, Bouganali H, Canque B, et al. The Dielmo project: a longitudinal study of natural malaria infection and the mechanisms of protective immunity in a community living in a holoendemic area of Senegal. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51: 123–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diallo MA, Badiane AS, Diongue K, Deme A, Lucchi NW, Gaye M, et al. Non-falciparum malaria in Dakar: a confirmed case of Plasmodium ovale wallikeri infection. Malar J. 2016;15: 429 doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1485-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poirier P, Doderer-Lang C, Atchade PS, Lemoine J-P, de l’Isle M-LC, Abou-Bacar A, et al. The hide and seek of Plasmodium vivax in West Africa: report from a large-scale study in Beninese asymptomatic subjects. Malar J. 2016;15: 570 doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1620-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steketee RW, Nahlen BL, Parise ME, Menendez C. The burden of malaria in pregnancy in malaria-endemic areas. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64: 28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moussiliou A, Sissinto-Savi De Tove Y, Doritchamou J, Luty AJ, Massougbodji A, Alifrangis M, et al. High rates of parasite recrudescence following intermittent preventive treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine during pregnancy in Benin. Malar J. 2013;12: 195 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cottrell G, Moussiliou A, Luty AJF, Cot M, Fievet N, Massougbodji A, et al. Submicroscopic Plasmodium falciparum Infections Are Associated With Maternal Anemia, Premature Births, and Low Birth Weight. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2015;60: 1481–1488. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huynh B-T, FIEVET N, Briand V, Borgella S, Massougbodji A, Deloron P, et al. Consequences of Gestational Malaria on Birth Weight: Finding the Best Timeframe for Intermittent Preventive Treatment Administration. PLoS ONE. 2013;7: e35342 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Minja DTR, Schmiegelow C, Mmbando B, Boström S, Oesterholt M, Magistrado P, et al. Plasmodium falciparum mutant haplotype infection during pregnancy associated with reduced birthweight, Tanzania. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19 doi: 10.3201/eid1909.130133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jelliffe EF. Low birth-weight and malarial infection of the placenta. Bull World Health Organ. 1968;38: 69–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bouvier P, Rougemont A, Breslow N, Doumbo O, Delley V, Dicko A, et al. Seasonality and malaria in a west African village: does high parasite density predict fever incidence? Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145: 850–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saute F, Menendez C, Mayor A, Aponte J, Gomez-Olive X, Dgedge M, et al. Malaria in pregnancy in rural Mozambique: the role of parity, submicroscopic and multiple Plasmodium falciparum infections. Trop Med Int Health TM IH. 2002;7: 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dicko A, Mantel C, Thera MA, Doumbia S, Diallo M, Diakité M, et al. Risk factors for malaria infection and anemia for pregnant women in the Sahel area of Bandiagara, Mali. Acta Trop. 2003;89: 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fried M, Duffy PE. Adherence of Plasmodium falciparum to chondroitin sulfate A in the human placenta. Science. 1996;272: 1502–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muthusamy A, Achur RN, Bhavanandan VP, Fouda GG, Taylor DW, Gowda DC. Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes adhere both in the intervillous space and on the villous surface of human placenta by binding to the low-sulfated chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan receptor. Am J Pathol. 2004;164: 2013–2025. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63761-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doritchamou J, Bertin G, Moussiliou A, Bigey P, Viwami F, Ezinmegnon S, et al. First-trimester Plasmodium falciparum infections display a typical “placental” phenotype. J Infect Dis. 2012;206: 1911–1919. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

OR = Odd ratio; *Crude ORs for parity, gestational age, season of enrolment are adjusted for all other Covariates (parity, gestational age, mother’s age, season of enrolment)

(DOCX)

OR = Odd ratio; *Crude ORs for parity, gestational age, season of delivery are adjusted for all other Covariates (parity, gestational age, mother’s age, season of enrolment).

(DOCX)

*P value.

(DOCX)

* Proportion of women who developed the corresponding outcome from each type of infection group is presented. **P. falciparum, non-falciparum and mixed infections groups were compared with no malaria infection.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.