Abstract

Background The aim of the present study is to review the available data on suture-mediated closure devices (SMCDs) and fascia suture technique (FST), which are alternatives for minimizing the invasiveness of percutaneous endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (p-EVAR) and reduce the complications related to groin dissections.

Methods The Medline, ClinicalTrials.gov, and Cochrane library – Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) databases were searched for publications regarding SMCD and FST between January 1999 and December 2016.

Results We review 37 original articles, 30 referring to SMCDs (Prostar XL and Proglide), which included 3,992 patients, and 6 articles referring to FST, which include 426 patients. The two techniques are compared only in one article (100 patients). The two types of SMCDs were Prostar and Proglide. In most studies on SMCDs, the reported technical success rates were between 89 and 100%, but the complication rates varied greatly between 0 and 25%. Concerning FST, the technical success rates were also high, ranging between 87 and 99%. However, intraoperative complication rates ranged between 1.2 and 13%, whereas postoperative complication rates varied from 0.9 to 6.2% for the short-term and from 1.9 to 13.6% for the long-term.

Conclusions SMCDs and FST seem to be effective and simple methods for closing common femoral artery (CFA) punctures after p-EVAR. FST can reduce the access closure time and the procedural costs with a quite short learning curve, whereas it can work as a bailout procedure for failed SMCDs suture. The few failures of the SMCDs and FST that may occur due to bleeding or occlusion can easily be managed.

Keywords: suture-mediated closure devices, Prostar XL, Proglide system, fascia suture technique, percutaneous endovascular aortic aneurysm repair, femoral access, complications

During the last decade, percutaneous endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (p-EVAR) has been an attractive minimally invasive technique in a selected group of patients with aortic anatomy suitable for endografting. Traditionally, endovascular aortic aneurysm repair using the cut-down surgical approach (s-EVAR) was preferred, mostly owing to the large sheath sizes of the early devices. 1 2 3 4 5 However, as a result of the exposure of the common femoral arteries (CFAs), local groin wound complications were common in the postoperative period. 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 To minimize its invasiveness and reduce the complications related to groin dissections, some surgeons developed alternative access techniques.

Fascia suture technique (FST) 14 15 has gained field the last years as an alternative option for covering the common femoral artery (CFA) after p-EVAR. In 1997, Diethrich 14 and, several years later, Larzon et al 15 were the pioneers, who described the method as minimal access suture technique of the cribriform fascia “fascia closure”; however, it is still not widely adopted.

An alternative surgical option that has been described after the recent advances in stent graft technology (reduction of stent-graft delivery profile) refers to suture-mediated closure devices (SMCDs). 16 17 Perclose Prostar XL (Abbott Vascular, Redwood City, CA) is the main device available for percutaneous closure of large bore arterial access sheath. Although, Prostar XL was the only device with formal approval for use in EVAR, several authors have used the Proglide system (Abbott Vascular, Redwood City, CA) off-label in daily clinical practice until April 2013. 18 19 Thereafter, the Proglide system is approved for 5 F to 21 F closure, with double Proglide use required for larger than 8 F sheaths.

The primary aim of this article was to determine the efficacy and safety of the FST and SMCDs regarding closing CFA punctures after p-EVAR. All the available data from prospective, retrospective, and randomized controlled trials that reported loco-regional complications have also been evaluated in this systematic review.

Methods

Search Strategy, Data Sources, and Eligibility Criteria

A systematic review was conducted in accordance to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. A study protocol was agreed upon and was strictly followed by all authors. Identification of eligible studies was performed using three distinct databases through December 2016: Medline, ClinicalTrials.gov, and Cochrane library – Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). The following MeSH terms were utilized in various combinations: “Suture-mediated closure devices” and “Fascia Suture Technique.” and the keywords “Percutaneous endovascular aneurysm repair (p-EVAR)” and “Femoral Artery Access Sites.” Moreover, the reference lists of all included articles were examined manually for further references. All studies were independently assessed by two investigators (Georgios Karaolanis and Konstantinos G. Moulakakis), and the full texts of the studies were retrieved.

Studies were included in the present review if:

They provided results referring to SMCDs that involved only the Prostar XL and/or Proglide closure devices.

They provided results referred to FST.

A series of at least 10 patients were studied.

Articles were excluded if:

They were referring also to other SMCDs other than Prostar XL and/ or Proglide closure devices.

They provided data of the SMCDs use in other surgical fields other than the vascular.

Narrative reviews described the FST and the SMCDs without elaboration data.

Prospective, retrospective, and randomized trials were included, but letters, reviews, and non-English language articles were excluded. We sought to review all updates on the subject after the introduction of the FST in the treatment armamentarium.

As primary outcomes, technical success rate and loco-regional complications using both closure techniques (FST/SMCDs) were considered. Secondary outcomes assessed were operative time, hospital stay, and time to ambulation in the SMCDs group. In the FST group, short- (≤30 days) and long-term (>30 days and within 12 months) complications were also classified as secondary outcomes.

Definitions

The definition of technical success was not uniform across all studies in the SMCDs group. 16 17 18 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 We attempted to standardize technical success as the ability to obtain hemostasis at the access site without the need for surgical cut down. On the other hand, in the FST group, technical success was defined as the achievement of hemostasis with adequate distal perfusion within the first 24 hours without femoral occlusion or use of additional fascial sutures. 15 46 47 48 49 50 Any complication (bleeding and/or thrombosis) that leads to additional procedure within 24 hours was classified as intraoperative complication, whereas complications, such as bleeding, thrombosis, pseudoaneurysm, stenosis, neuralgia, seroma, and local infection, that took place after 24 hours were considered postoperative.

Fascia Suture Technique

Under general, spinal, or local anesthesia, puncture of the femoral artery just below the inguinal ligament and after its identification either palpably, through duplex or through computed tomography angiography (CTA), is performed. The next step after the completion of any endovascular procedure is the fascia closure. This procedure requires the introducer with the dilator and the guide wire to remain in place. First, the skin incision at the introducer insertion site is extended either transversally by 4 to 8 cm 15 or longitudinally by 3 to 4 cm. 46 Dissection down, but not through, the femoral fascia follows. Fascia closure is performed either with one stitch (No. 2 PDS absorbable suture) in the fascia on each side of the introducer with the arterial wall intentionally not included in the stitch 15 or with a double U-shaped suture line (No. 2 PDS absorbable suture) on both sites of the lumen of the introducer, as it was recently described. 50 Subsequently, the sutures are tightened with simultaneous withdrawal of the introducer. When hemostasis is achieved, the guidewire is removed, and the sutures are further tightened. In case of inadequate hemostasis, reinsertion of the introducer is indicated to perform supplementary suturing either through primary fascia suturing or with a superficial Z-shape (Prolene 3–0) suture. 47 During this step, attention should be paid so that suturing achieves bleeding stoppage without causing narrowing of the vessel. In case of further bleeding, open dissection of the femoral artery and arterial closure is indicated, and this was defined as a technical failure. 47 A handheld Doppler is used to identify the flow through the femoral segment. 15 47 The whole procedure is completed with the skin closure without the use of external compression.

Results

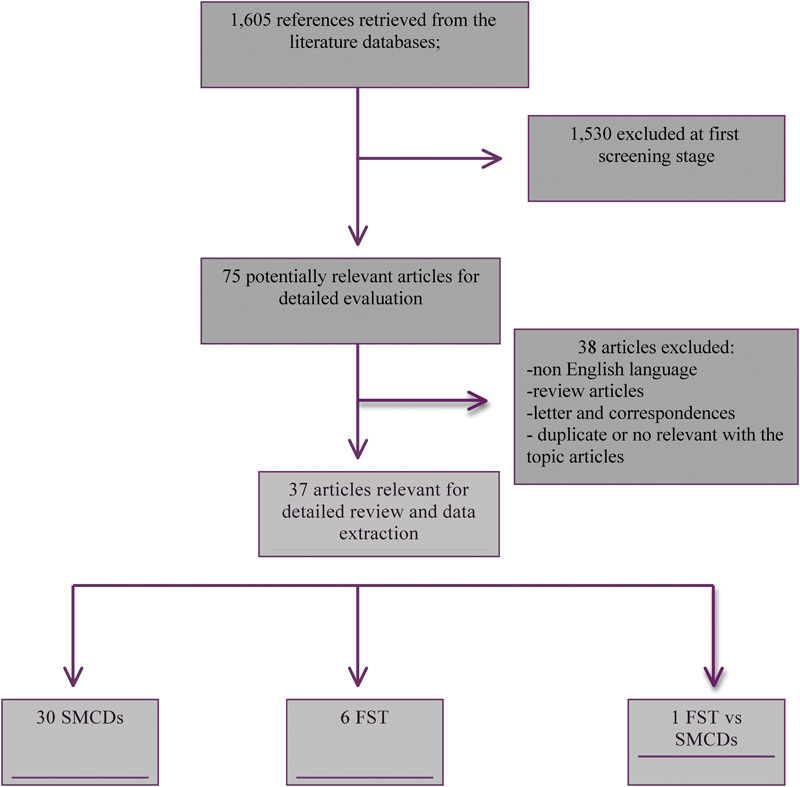

The literature search yielded 1,605 publications ( Fig. 1 ). After an extensive review, 1568 publications (non-English language, review articles, letter, and correspondences, duplicate or no relevant with the topic) were excluded from subsequent evaluation. Thirty-seven original articles with a total of 4,518 patients were eligible for the present systematic review: 30 referring to SMCD, 6 to FST, and 1 article comparing SMCD with FST.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart summarizing literature search results. FST, fascia suture technique; SMCDs, suture-mediated closure devices.

Study Characteristics

Out of the 30 studies referring to SMCD, 16 17 18 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 only 2 17 20 were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (SMCD with open cut down), and the other 28 16 18 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 were non-randomized trials (NRCTs). In addition, 9 out of the 30 studies also included cases with groin dissection as a control group for comparison, 16 17 20 21 28 30 31 32 43 whereas the remaining 21 studies included only cases with SMCDs. The effectiveness of the Proglide system was evaluated in four studies, 18 28 29 42 whereas the outcomes of the two SMCDs were compared and described in two studies. 27 29 On the other hand, all six studies 15 47 48 49 50 51 referring to FST were non-randomized trials and did not include a control group with groin dissection for comparison. Recently, one RCT study investigated whether the FST can reduce the access closure time and the procedural costs compared with the Prostar XL technique in patients ( n = 100) undergoing EVAR. 52 The 30 original articles reporting results of SMCD included 3,992 patients having undergone closure of the wound of CFA by this method. Concerning the six studies on FST, they included 426 patients and 660 catheterized CFA in total.

Results of SMCD

The two types of SMCD that were used in the reviewed studies were Prostar XL and the Proglide system. Prostar XL was used in 27 studies, 16 17 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 43 44 45 46 and Proglide was used in 6 studies. 18 20 27 28 29 42 In three studies, 20 27 29 both Prostar and Proglide devices were used. The rates of technical success by access site ranged between 63 and 100%, but with only two articles 34 37 reporting rates below 80% and most articles 16 17 18 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 35 36 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 reporting rates between 89 and 100%. The rates of technical success by patient ranged between 53 and 100%, but with only three articles reporting rates below 80% 22 34 35 and most articles reporting rates between 89 and 100%. 16 17 21 23 28 29 30 32 33 36 40 41 42 43 44 46 The complication rates varied greatly, with rates between 0 and 25%. 16 17 18 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 35 36 38 39 41 42 43 44 45 46 The mean operating time ranged between 86.7 and 180 minutes. 16 17 20 21 25 28 29 30 31 32 34 37 41 45 The mean time to ambulation was mentioned in only four articles, and it ranged between 17 and >24 hours, 17 20 25 29 with the exception of one article in which it was only 4 to 6 hours after the operation. 38 The mean duration of hospital stay was between 1.3 and 6.7 days. 16 20 21 25 26 28 29 30 31 32 36 37 41 42 45 Tables 1 and 2 summarize the above results.

Table 1. Summary of all the studies using SMCDs after p-EVAR and their characteristic.

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of study | Number of patients ( n ) | Type of device | Number of devices ( n ) | Catheter sheath size (Fr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torsello et al 17 | 2003 | RCT | 30 (15 p-EVAR, 15 s EVAR) | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | ≥14 Fr |

| Nelson et al 20 | 2014 | RCT | 151 (101 p-EVAR,50 s EVAR) | Prostar XL 10 Fr or Proglide 8 F | 1 Prostar and 2 Proglide | 21 Fr |

| Ichihashi et al 28 | 2016 | RS | 146 (50 p-EVAR, 96 s EVAR | Proglide 6 F | 1 | 16–24 Fr/12–18(c) |

| Pratesi et al 27 | 2015 | OS | 1322 | Prostar XL 10 (78.4% of cases) Proglide 6 F (21.6% of cases) | 1 Prostar or 2 Proglide | 9–25 Fr |

| Rijkée et al 26 | 2015 | OS | 85 | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | 9–22 Fr |

| Petronelli et al 25 | 2014 | OS | 200 | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | 18–24 Fr /12–18 Fr(c) |

| Skagius et al 24 | 2013 | OS | 114 | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | 20–26 Fr |

| Thomas et al 23 | 2013 | OS | 50 | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | 8–25 Fr |

| Metcalfe et al 45 | 2012 | OS | 57 | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | 12–22 Fr |

| Kracjer et al 29 | 2011 | PS | 38 | Prostar XL 10/ Proglide 6 F | 1 or 2 Prostar or 2 Proglide | >17 F/9 Fr (c) |

| Grenon et al 42 | 2009 | RS | 15 | Proglide 6 F | 2 | 15–21 Fr |

| Eisenack et al 44 | 2009 | OS | 500 | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | 14–24 Fr |

| Heyer et al 41 | 2009 | OS | 14 | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | 20–22 Fr/16–18 Fr (c) |

| Arthurs et al 40 | 2008 | OS | 88 | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | 12–20 Fr |

| Lee et al 18 | 2008 | OS | 292 | Proglide 6 F | 2 | 12–24 F |

| Jean-Baptiste et al 16 | 2008 | OS | 40 (19 p-EVAR, 21 s EVAR) | Prostar XL 10 | 2 Prostar/1 Prostar (c) | 18–24 Fr |

| Najjar et al 32 | 2007 | OS | 37 (15 p-EVAR, 22 s EVAR) | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | 12–18 Fr |

| Watelet et al 22 | 2006 | OS | 29 | Prostar XL 8 and 10 | 2 Prostar XL 8 or 1 Prostar XL 10 | 16–22 Fr |

| Starnes et al 39 | 2006 | OS | 49 | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | 12–24 Fr |

| Petersen et al 43 | 2005 | OS | 11 (7 p-EVAR, 4 s EVAR) | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | 18 Fr |

| Borner et al 21 | 2004 | OS | 121(95 p-EVAR, 26 s EVAR) | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | 14–20 Fr |

| Morasch et al 31 | 2004 | OS | 82 (47 p-EVAR, 35 s EVAR) | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | 12–18 Fr |

| Quinn and Kim 38 | 2004 | OS | 63 | Prostar XL 10 | 1 Prostar for <12 Fr sheaths, or 2 for >12 Fr | 12–16 Fr |

| Howell et al 30 | 2002 | OS | 126 (30 p-EVAR, 96 s EVAR) | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | 22 and 16 Fr (c) |

| Rachel et al 37 | 2002 | OS | 100 | Prostar XL 10 | 2 | 16/22 Fr |

| Quinn et al 36 | 2002 | OS | 15 | Prostar XL 10 | 2 | 14–20 Fr |

| Howell et al 46 | 2001 | OS | 144 | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | 16 Fr |

| Teh et al 35 | 2001 | OS | 44 | Prostar XL 10 | 1 | 18–20 Fr/16–18 Fr (c) |

| Traul et al 34 | 2000 | OS | 17 | Prostar XL 10 | 2 Prostar/1 Prostar (c) | 22 Fr/16 Fr (c) |

| Haas et al 33 | 1999 | OS | 12 | Prostar XL 10 | 1 Prostar for 16 Fr sheaths, and 2 for 22 Fr. | 16–22 Fr |

| Total | 1999–2015 | RCT/OS/RS | 3992 | Prostar/Proglide | 1 Prostar and/or 1 or 2 Proglide | 9–26 Fr |

Abbreviations: c, contralateral; FST, fascia suture technique; NR, non-reported; OS, observed study; p/s-EVAR, percutaneous/ surgical cut down EVAR; RCT, randomized control trial; RS, retrospective study; SMCDs, suture-mediated closure devices.

Table 2. Summarizes all the studies using SMCDs after p-EVAR and their characteristics.

| Authors | Year of publication | Technical success by access site (%) | Technical success rate (%) | Complication rates n (%) | Mean hospital stay (days) | Mean operative time (min) | Time to ambulation (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torsello et al 17 | 2003 | NR | 93% (Prostar XL) 100% (s-EVAR) | 13% | NR | 86.7 ± 27 min (Prostar XL)/107.8 ± 38.5 min s-EVAR | 20.1 ± 3 (Prostar XL)/33.1 ± 19.4 (s-EVAR) |

| Nelson et al 20 | 2014 | 95% | NR | 5% | 1.3 ± 0.7 (Proglide) 1.4 ± 0.9 (Prostar) | 107 ± 45 min (Proglide) 95 ± 35 min (Prostar) | 17 ± 7.2 (Proglide) 16 ± 9.1 (Prostar) |

| Ichihashi et al 28 | 2016 | 100% | 100% | 4% | 6.7 ± 6.8 (Proglide) 9.3 ± 4.5 (s-EVAR) |

153 ± 47 (Proglide)/211 ± 88 (s-EVAR) | NR |

| Pratesi et al 27 | 2015 | 96.8% | NR | 3.2% | NR | NR | NR |

| Rijkée et al 26 | 2015 | 93.5% | NR | 6.5% | 5.19 ± 4.93 | NR | NR |

| Petronelli et al 25 | 2014 | 97.5% | NR | 2.5% | ≥2 | 45–300 min (150 ± 30 min) | ≥24 |

| Skagius et al 24 | 2013 | 91.5% | NR | 8.5% | NR | NR | NR |

| Thomas et al 23 | 2013 | 93.6% | 90% | 7.7% | NR | NR | NR |

| Metcalfe et al 45 | 2012 | 95.2% | NR | 4.8% | 2 | 131 (105–151) | NR |

| Kracjer et al 29 | 2011 | NR | 97% | 3% | 1.4 | 117 ± 47 | 17 ± 15 |

| Grenon et al 42 | 2009 | 93% | 93% | 7% | 2.2 | NR | NR |

| Eisenack et al 44 | 2009 | 96.1% | 95.4% | 3.9% | NR | NR | NR |

| Heyer et al 41 | 2009 | 96% | 93% | 4% | 1.4 | 119 | NR |

| Arthurs et al 40 | 2008 | 95% | 95% | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Lee et al 18 | 2008 | 94.4% | NR | 5.5% | NR | NR | NR |

| Jean-Baptiste et al 16 | 2008 | 92% (Prostar) 90% (s-EVAR) |

92% (Prostar) 90% (s-EVAR) |

16% (Prostar) 14% (s-EVAR) |

5.8 (Prostar) 7.8 (s-EVAR) |

130 min (Prostar)/122 minute (cut down) | NR |

| Najjar et al 32 | 2007 | NR | 100% (Prostar) NR (s-EVAR) | 0% (Prostar) NR (s-EVAR) |

3.0 ± 6.9 (Prostar) 11.5 ± 6.9 (s-EVAR) | 107 ± 30 min (Prostar)/205 ± 31 min (s-EVAR) | NR |

| Watelet et al 22 | 2006 | 83% | 72% | 17% | NR | NR | NR |

| Starnes et al 39 | 2006 | 94% | NR | 6.3% | NR | NR | NR |

| Petersen et al 43 | 2005 | NR | 100% (Prostar) 100% (s-EVAR) | 0% (Prostar) 0% (s-EVAR) |

NR | NR | NR |

| Borner et al 21 | 2004 | 89% (Prostar) NR | 89% (Prostar) | 21% (Prostar) | 4 | 180 min (100–425) (Prostar XL) | NR |

| Morasch et al 31 | 2004 | NR | NR | 19% (Prostar) 17% (s-EVAR) |

1.48 (Prostar) 1.89 (s-EVAR) |

139 min (Prostar) 169 (s-EVAR) |

NR |

| Quinn and Kim 38 | 2004 | NR | NR | 23% | NR | NR | 4–6 |

| Howell et al 30 | 2002 | 97% (Prostar) NR |

93% (Prostar) | 7% (Prostar) NR (s-EVAR) |

1.3 ± 0.6 | 105 ± 21 min (Prostar) | NR |

| Rachel et al 37 | 2002 | 64–85% | NR | NR | 1.6 | 106 min | NR |

| Quinn et al 36 | 2002 | NR | 93% | 7% | 6.5 (urgent cases) 1.7 (elective) |

NR | NR |

| Howell et al 46 | 2001 | NR | 94% | 6% | NR | NR | NR |

| Teh et al 35 | 2001 | 85% | 75% | 25% | NR | NR | NR |

| Traul et al 34 | 2000 | 63% | 53% (Prostar) | NR | NR | 90 min | NR |

| Haas et al 33 | 1999 | 100% | 100% (Prostar) | 0% | NR | NR | NR |

| Total | 1999–2015 | 63–100% | 53–100% | 0–25% | 1.3–6.7 | 86.7–180 min | >4 |

Abbreviations: c, contralateral; FST, fascia suture technique; NR, non-reported; p/s-EVAR, percutaneous/ surgical cut down EVAR; SMCDs, suture-mediated closure devices.

It is worth mentioning that out of the six studies that used the Proglide system, 18 20 27 28 29 42 five used the 6 F Proglide system, 18 27 28 29 42 and one used the 8 F Proglide system, 20 while three used only the Proglide system, 18 28 42 and the other three used either the Proglide or the Prostar XL system. 20 27 29 However, only two studies compared the Proglide with the Prostar XL system. 20 27 Nelson et al 20 reported no significant differences between the two systems in terms of blood loss, operative time, technical failure, major access-related complications, groin pain, time to ambulation, or length of hospital stay. In addition, neither Nelson et al 20 nor Pratesi et al 27 detected significant difference between the two systems in regards to technical failure (Nelson et al: Proglide: 6%, Prostar XL: 11.8%; p = 0.487 and Pratesi et al: Proglide: 2.5%, Prostar XL: 3.3%; p = 0.33). Similarly, Nelson et al 20 found no significant difference between the two systems as far as major access-related complications are concerned (Proglide: 6%, Prostar XL: 11.8%; p = 0.487).

Results of FST

The technical success rates were high, ranging between 87 and 99%. The rates of intraoperative complications ranged between 1.2 and 13%, whereas the rates of short-term complications, within 30 days from the operation, were from 0.9 up to 6.2%. Similar were the rates of long-term complications >30 days from the operation, which varied between 1.9 and 13.6%. 15 47 48 49 50 51 Table 3 illustrates the above results. Only one study, conducted by Larzon et al, 52 has attempted to compare FST with SMCD. In particular, median access closure time was shorter with the FST than the Prostar XL Device (12.4 min versus 19.9 min, p < 0.001), but no significant differences were detected between FST and SMCD in regards to the rates of technical failure, complications, or reintervention. In addition, there was a decrease in cost by €800 when FST was used ( p < 0.001). 52

Table 3. Short- and long-term results of FST after P-EVAR among various studies.

| Authors | Number of patients ( n ) | Number of Femoral sites (n) |

Technical success (%) | Complications ( n (%)) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative n (%) |

<30 days n (%) |

>30 days n (%) |

||||

| Larzon et al 15 | 127 | 131 | 87.8% | 16 (12.2%) | NR | 2 (1.5%) |

| Harrison et al 51 | 38 | 69 | 87% | 9 (13%) | 4 (5.8%) | NR |

| Montán et al 47 | 100 | 160 | 91.3% | 14 (8.8%) | 2 (1.3%) | 9 (5.6%) |

| Mathisen et al 49 | 49 | 81 | 99% | 1 (1.2%) | 5 (6.2%) | 11 (13.6%) |

| Dziekiewicz et al 50 | 58 | 116 | 96% | 5 (4.3%) | 1 (0.9%) | 3 (2.6%) |

| Bountouris et al 48 | 54 | 103 | 96.1% | 4 (3.9%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (1.9%) |

| Total | 426 | 660 | 87–99% | 1.2–13% | 0.9–6.2% | 1.5–13.6% |

Abbreviations: FST, fascia suture technique; N , number of arteries in every study; NR, non-reported; p-EVAR; percutaneous endovascular aortic aneurysm repair.

Discussion

In all fields of surgery, there is a trend toward less invasive procedures, aiming at reducing hospital stay, complications, and mortality. In vascular surgery, for the treatment of aortic diseases, open surgical technique is gradually less applied, and instead p-EVAR is a widely accepted treatment modality today. As a result of the gradually increased popularity of the latter, the debate regarding the method of arterial closure grows. FST and SMCDs have emerged as alternative techniques for closure of CFA 14 15 33 after p-EVAR.

Since the first description by Haas et al in 1999, 33 the “preclose” technique has been used increasingly to perform p-EVAR. The technique utilizes SMCDs, such as Prostar XL and/or Proglide in off-label application, to close arterial access larger than 10 F. The technical success rate was 100% based on a sample of 12 patients. One year later, a first attempt was made by Traul et al, 34 who used the Prostar XL 10 device on 17 patients with endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. In particular, they used two 10 Fr devices on the side of the main body and one contralateral 10 Fr device contralateral. The technical success of this first attempt was low (63% by access site and 53% by patient), but the success rates have risen since then in most studies. 17 28 29 32 33 43

In our analysis, the technical success rate ranges between 89 and 100%, whereas the loco-regional complications were calculated between 0 and 25%. Our results are absolutely consistent with two recently published studies. 53 54 In the first study, 53 the use of the Prostar XL device has indicated overall good results for the percutaneous techniques with a weighted average success rate of 91% (87–95%) in the same time that regarding local complications a risk ratio of 0.87 (95% confidence interval [CI]) in favor of p-EVAR over surgical access was found a lower risk which nevertheless did not reach statistical significance. In the second study, 54 the reported technical success in p-EVAR group was 92%, whereas the local complications were reported lower in the group undergoing percutaneous access (risk ratio, 0.47; 95% CI). In the same time, the aforementioned studies revealed that p-EVAR compared with s-EVAR seemed advantageous in terms of reduced procedural time, hospital stay, and time to ambulation in comparison. These results were confirmed in our study ( Tables 1 and 2 ) with the mean operative time to be 86.7 to 180 min, the hospital stay 1.3 to 6.7 days, and mean time to ambulation 17 to 24 hours. To minimize the groin complication, rates should be considered in the context of patient selection for p-EVAR. As demonstrated in most series, and to be eligible for p-EVAR, patients had to meet certain anatomical criteria. 17 18 20 24 27 28 30 37 38 44 46 The main reasons why some patients were not considered candidates for p-EVAR were: small iliofemoral artery size (<6 or <7 mm diameter), 22 46 high CFA bifurcation, 23 24 25 26 27 anterior or circumferential CFA calcification, 23 24 25 26 27 scarred groin, 17 34 43 45 obesity, 25 26 27 CFA aneurysm, 22 and the presence of vascular graft in the inguinal zone. 43 So, particular caution is needed when clinicians perform p-EVAR in this group of patients, whereas their experience and familiarity with the devices remain significant predictors of success. 44

An alternative closure technique of the femoral artery (FST) has gained territory in the last years after the first description by Diendrich. 14 The first attempt to evaluate it in the daily clinical practice was made by Larzon et al 15 who used this technique in 51% (131/257) of the femoral arteries after endovascular repair of the thoracic or abdominal aorta. In this study, exclusion criteria were not reported, and the detection of the CFA preoperatively was assessed with palpation. A few years later, Harrison et al 51 reviewed their results for 69 cases, where CFA were detected by duplex ultrasound. Exclusion criteria in this study were morbid obesity, high bifurcation of CFA, previous groin surgery, inadvertent high puncture, arteries with diameter <5 mm, and the surgeons' preference. It is worth mentioning that Harrison et al 51 proposed one of the crucial steps of the procedure, which is to leave a guidewire in the artery lumen until satisfactory hemostasis is achieved.

Subsequently, Montán et al 47 presented their results from 160-sutured fascial cases, where CFA were assessed with preoperative fluoroscopic guidance. In this study, there were no anatomical exclusion criteria such as high bifurcation of the CFA, and the thickness of the fat overlying the CFA did not compromise the success of the technique. In the same period, Mathisen et al. 49 reviewed their results in a retrospective study, which included 49 patients (81 femoral access sites). The CFA was detected using palpation. It is worth mentioning that in these later studies, plaque/calcification did not appear to influence the success of fascia closure, as it was reported with the SMCD. 23 24 25 26 27 A new attempt to evaluate the technical success was made by Dziekiewicz et al. 50 In this study, 58 patients (116 CFA) were included, whose CFA were detected preoperatively using a CTA. Recently, we published our experience with the results to be acceptable. 48 Primary and secondary technical success rates were high with 96.1 and 100%, respectively, and with low short- and mid-term technical failures.

The other finding of our analysis was that p-EVAR using FST reported a technical success between 87 and 99%. Most short-term complications (0.9–6.2%) associated with the technique, such as dissection, pseudoaneurysm formation, arterial stenosis, and ischemia, could be identified using handheld Doppler in the operation room and a duplex scan postoperatively. Moreover, perioperative bleeding could be tackled immediately by reintroducing the sheath over the retained guidewire and putting additional sutures if needed. Long-term complications (1.9–13.6%), such as arterial stenosis or pseudoaneurysms were faced either surgically or conservatively. Therefore, we judged the technique as safe, effective, and durable with a quite short learning curve. Moreover, FST seems to offer a “no-touch” artery closure, which could be advantageous in case of endovascular treatment of ruptured aortic aneurysms. 52 The lack of the preclosure preparation of the access site seems to be advantageous under these critical situations. Furthermore, as demonstrated in the Larzon et al's study, 52 FST can work as a bailout procedure for failed Prostar XL suture. In the same study, there was an attempt to investigate whether FST can reduce the access closure time and the procedural costs compared with the Prostar XL technique. 52 The FST was raised as faster (median closure time 12.4 min) than Prostar (median closure time 19.9 min), but the main reason why the FST was significantly cheaper was the reduction in material costs. There was a significant cost difference in favor of FST, with a median difference of €800. 52

On the other hand, FST presents two weak points that the vascular surgeon must keep in mind for successful outcomes. First, not all patients have an anatomically distinct femoral fascia, especially on the medial side. Weakness of the femoral fascia may cause leakage and difficulty in suture sealing. Second, optimal puncture site below the inguinal ligament and above the femoral bifurcation represents the cornerstone for a successful FST. A puncture above the inguinal ligament may make the femoral closure less effective, as the femoral fascia is not appropriate for the coverage of the artery wall, and retroperitoneal bleeding may occur. In addition, low puncture close to the deep femoral artery (DFA) might also lead to the same complication and cause hemorrhage in the groin. 30

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that collect overall data from the FST and SMCDs studies after p-EVAR. However, the study presents some limitations. First, the nature of p-EVAR and FST studies that include only three randomized controlled trial. Furthermore, the reviewed studies presented some differences with regard to the type of endovascular procedure, the indication for the treatment, the type of closure device used, and the duration of follow-up. All studies failed to provide clear guidelines when SMCDs and FST were useful under significant confounders, such as vascular calcification, obesity, groin scarring, etc. Moreover, the outcome was described with relevant terms, such as technical success and failure. Further studies with a large number of patients are necessary to compare the two techniques and to extract essential and safe conclusions.

Conclusions

SMCDs and FST seem to be effective and simple methods for closing CFA punctures after p-EVAR. The techniques seem to be applicable to all patients, even in emergency procedures, whereas the few failures that may occur due to bleeding or occlusion can easily be managed. Particular caution is needed when clinicians perform p-EVAR using SMCDs where their experience and familiarity with the devices remain significant predictors of success. FST can reduce the access closure time and the procedural costs with a quite short learning curve, still the results remain controversial due to the limited number of published studies.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest None.

References

- 1.Birch S E, Borchard K L, Hewitt P M, Stary D, Scott A R. Endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: a 7 year experience at the Launceston General Hospital. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75(05):302–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalainas I, Nano G, Casana R, Tealdi Dg. Mid-term results after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms: a four-year experience. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;27(03):319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kibbe M R, Matsumura J S; Excluder Investigators.The Gore Excluder US multi-center trial: analysis of adverse events at 2 years Semin Vasc Surg 20031602144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slappy A L, Hakaim A G, Oldenburg W A, Paz-Fumagalli R, McKinney J M. Femoral incision morbidity following endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2003;37(02):105–109. doi: 10.1177/153857440303700204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faries P L, Brener B J, Connelly T L et al. A multicenter experience with the Talent endovascular graft for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35(06):1123–1128. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.123324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohnert T U, Oelert F, Wahlers T et al. Matched-pair analysis of conventional versus endoluminal AAA treatment outcomes during the initial phase of an aortic endografting program. J Endovasc Ther. 2000;7(02):94–100. doi: 10.1177/152660280000700203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore W S, Kashyap V S, Vescera C L, Quiñones-Baldrich W J.Abdominal aortic aneurysm: a 6-year comparison of endovascular versus transabdominal repair Ann Surg 199923003298–306., discussion 306–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chuter T A, Gordon R L, Reilly L M et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm in high-risk patients: short- to intermediate-term results of endovascular repair. Radiology. 1999;210(02):361–365. doi: 10.1148/radiology.210.2.r99ja37361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Treharne G D, Thompson M M, Whiteley M S, Bell P R. Physiological comparison of open and endovascular aneurysm repair. Br J Surg. 1999;86(06):760–764. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.May J, White G H, Yu Wet al. Concurrent comparison of endoluminal versus open repair in the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms: analysis of 303 patients by life table method J Vasc Surg 19982702213–220., discussion 220–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brewster D C, Geller S C, Kaufman J Aet al. Initial experience with endovascular aneurysm repair: comparison of early results with outcome of conventional open repair J Vasc Surg 19982706992–1003., discussion 1004–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stelter W, Umscheid T, Ziegler P. Three-year experience with modular stent-graft devices for endovascular AAA treatment. J Endovasc Surg. 1997;4(04):362–369. doi: 10.1583/1074-6218(1997)004<0362:TYEWMS>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blum U, Voshage G, Lammer J et al. Endoluminal stent-grafts for infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(01):13–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701023360103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diethrich E B. What do we need to know to achieve durable endoluminal abdominal aortic aneurysm repair? Tex Heart Inst J. 1997;24(03):179–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larzon T, Geijer H, Gruber G, Popek R, Norgren L. Fascia suturing of large access sites after endovascular treatment of aortic aneurysms and dissections. J Endovasc Ther. 2006;13(02):152–157. doi: 10.1583/05-1719R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jean-Baptiste E, Hassen-Khodja R, Haudebourg P, Bouillanne P J, Declemy S, Batt M. Percutaneous closure devices for endovascular repair of infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms: a prospective, non-randomized comparative study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35(04):422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torsello G B, Kasprzak B, Klenk E, Tessarek J, Osada N, Torsello G F. Endovascular suture versus cutdown for endovascular aneurysm repair: a prospective randomized pilot study. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38(01):78–82. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(02)75454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee W A, Brown M P, Nelson P R, Huber T S, Seeger J M. Midterm outcomes of femoral arteries after percutaneous endovascular aortic repair using the Preclose technique. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47(05):919–923. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dosluoglu H H, Cherr G S, Harris L M, Dryjski M L. Total percutaneous endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms using Perclose ProGlide closure devices. J Endovasc Ther. 2007;14(02):184–188. doi: 10.1177/152660280701400210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson P R, Kracjer Z, Kansal N et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of totally percutaneous access versus open femoral exposure for endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (the PEVAR trial) J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(05):1181–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.10.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Börner G, Ivancev K, Sonesson B, Lindblad B, Griffin D, Malina M. Percutaneous AAA repair: is it safe? J Endovasc Ther. 2004;11(06):621–626. doi: 10.1583/04-1291MR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watelet J, Gallot J C, Thomas P, Douvrin F, Plissonnier D. Percutaneous repair of aortic aneurysms: a prospective study of suture-mediated closure devices. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;32(03):261–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas C, Steger V, Heller S et al. Safety and efficacy of the Prostar XL vascular closing device for percutaneous closure of large arterial access sites. Radiol Res Pract. 2013;2013:875484. doi: 10.1155/2013/875484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skagius E, Bosnjak M, Björck M, Steuer J, Nyman R, Wanhainen A. Percutaneous closure of large femoral artery access with Prostar XL in thoracic endovascular aortic repair. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;46(05):558–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petronelli S, Zurlo M T, Giambersio S, Danieli L, Occhipinti M. A single-centre experience of 200 consecutive unselected patients in percutaneous EVAR. Radiol Med (Torino) 2014;119(11):835–841. doi: 10.1007/s11547-014-0399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rijkée M P, Statius van Eps R G, Wever J J, van Overhagen H, van Dijk L C, Knippenberg B. Predictors of Failure of Closure in Percutaneous EVAR Using the Prostar XL Percutaneous Vascular Surgery Device. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;49(01):45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pratesi G, Barbante M, Pulli R et al. Italian Percutaneous EVAR (IPER) Registry: outcomes of 2381 percutaneous femoral access sites' closure for aortic stent-graft. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2015;56(06):889–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ichihashi T, Ito T, Kinoshita Y, Suzuki T, Ohte N. Safety and utility of total percutaneous endovascular aortic repair with a single Perclose ProGlide closure device. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63(03):585–588. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.08.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krajcer Z, Nelson P, Bianchi C, Rao V, Morasch M, Bacharach J. Percutaneous endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: methods and initial outcomes from the first prospective, multicenter trial. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2011;52(05):651–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howell M, Doughtery K, Strickman N, Krajcer Z. Percutaneous repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms using the AneuRx stent graft and the percutaneous vascular surgery device. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;55(03):281–287. doi: 10.1002/ccd.10072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morasch M D, Kibbe M R, Evans M E et al. Percutaneous repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40(01):12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Najjar S F, Mueller K H, Ujiki M B, Morasch M D, Matsumura J S, Eskandari M K. Percutaneous endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arch Surg. 2007;142(11):1049–1052. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.11.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haas P C, Krajcer Z, Diethrich E B. Closure of large percutaneous access sites using the Prostar XL Percutaneous Vascular Surgery device. J Endovasc Surg. 1999;6(02):168–170. doi: 10.1177/152660289900600209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Traul D K, Clair D G, Gray B, O'Hara P J, Ouriel K. Percutaneous endovascular repair of infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms: a feasibility study. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32(04):770–776. doi: 10.1067/mva.2000.107987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teh L G, Sieunarine K, van Schie G et al. Use of the percutaneous vascular surgery device for closure of femoral access sites during endovascular aneurysm repair: lessons from our experience. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2001;22(05):418–423. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2001.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quinn S F, Duke D J, Baldwin S S et al. Percutaneous placement of a low-profile stent-graft device for aortic dissections. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13(08):791–798. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61987-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rachel E S, Bergamini T M, Kinney E V, Jung M T, Kaebnick H W, Mitchell R A. Percutaneous endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Ann Vasc Surg. 2002;16(01):43–49. doi: 10.1007/s10016-001-0127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quinn S F, Kim J. Percutaneous femoral closure following stent-graft placement: use of the Perclose device. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27(03):231–236. doi: 10.1007/s00270-003-2713-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Starnes B W, Andersen C A, Ronsivalle J A, Stockmaster N R, Mullenix P S, Statler J D. Totally percutaneous aortic aneurysm repair: experience and prudence. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43(02):270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arthurs Z M, Starnes B W, Sohn V Y, Singh N, Andersen C A. Ultrasound-guided access improves rate of access-related complications for totally percutaneous aortic aneurysm repair. Ann Vasc Surg. 2008;22(06):736–741. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heyer K S, Resnick S A, Matsumura J S, Amaranto D, Eskandari M K. Percutaneous Zenith endografting for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg. 2009;23(02):167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grenon S M, Gagnon J, Hsiang Y N, Chen J C. Canadian experience with percutaneous endovascular aneurysm repair: short-term outcomes. Can J Surg. 2009;52(05):E156–E160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterson B G, Matsumura J S, Morasch M D, West M A, Eskandari M K. Percutaneous endovascular repair of blunt thoracic aortic transection. J Trauma. 2005;59(05):1062–1065. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000188634.72008.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eisenack M, Umscheid T, Tessarek J, Torsello G F, Torsello G B. Percutaneous endovascular aortic aneurysm repair: a prospective evaluation of safety, efficiency, and risk factors. J Endovasc Ther. 2009;16(06):708–713. doi: 10.1583/08-2622.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Metcalfe M J, Brownrigg J R, Black S A, Loosemore T, Loftus I M, Thompson M M. Unselected percutaneous access with large vessel closure for endovascular aortic surgery: experience and predictors of technical success. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;43(04):378–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howell M, Villareal R, Krajcer Z. Percutaneous access and closure of femoral artery access sites associated with endoluminal repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Endovasc Ther. 2001;8(01):68–74. doi: 10.1177/152660280100800112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montán C, Lehti L, Holst J, Björses K, Resch T A. Short- and midterm results of the fascia suture technique for closure of femoral artery access sites after endovascular aneurysm repair. J Endovasc Ther. 2011;18(06):789–796. doi: 10.1583/11-3621.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bountouris I, Melas N, Karaolanis G I et al. Endovascular aneurysm repair with fascia suture technique: short and mid-term results. Int Angiol. 2016;35(05):504–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mathisen S R, Zimmermann E, Markström U, Mattsson K, Larzon T. Complication rate of the fascia closure technique in endovascular aneurysm repair. J Endovasc Ther. 2012;19(03):392–396. doi: 10.1583/JEVT-11-3702R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dziekiewicz M, Maciag R, Maruszynski M. New surgical modification of fascial closure following endovascular aortic pathology repair. Wideochir Inne Tech Malo Inwazyjne. 2014;9(01):89–92. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2011.35795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harrison G J, Thavarajan D, Brennan J A, Vallabhaneni S R, McWilliams R G, Fisher R K. Fascial closure following percutaneous endovascular aneurysm repair. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41(03):346–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Larzon T, Roos H, Gruber G et al. Editor's choice. A randomized controlled trial of the fascia suture technique compared with a suture-mediated closure device for femoral arterial closure after endovascular aortic repair. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;49(02):166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haulon S, Hassen Khodja R, Proudfoot C W, Samuels E. A systematic literature review of the efficacy and safety of the Prostar XL device for the closure of large femoral arterial access sites in patients undergoing percutaneous endovascular aortic procedures. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41(02):201–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Malkawi A H, Hinchliffe R J, Holt P J, Loftus I M, Thompson M M. Percutaneous access for endovascular aneurysm repair: a systematic review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39(06):676–682. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]