Abstract

Chronic pain impacts individuals with pain as well as their loved ones. Yet, there has been little attention to the social context in individual psychological treatment approaches to chronic pain management. With this need in mind, we developed a couple-based treatment, “Mindful Living and Relating,” aimed at alleviating pain and suffering by promoting couples’ psychological and relational flexibility skills. Currently, there is no integrative treatment that fully harnesses the power of the couple, treating both the individual with chronic pain and the spouse as two individuals who are each in need of developing greater psychological and relational flexibility to improve their own and their partners’ health. Mindfulness, acceptance, and values-based action exercises were used to promote psychological flexibility. The intervention also targets relational flexibility, which we define as the ability to interact with one’s partner, fully attending to the present moment, and responding empathically in a way that serves one’s own and one’s partner’s values. To this end, the intervention also included exercises aimed at applying psychological flexibility skills to social interactions as well as emotional disclosure and empathic responding exercises to enhance relational flexibility. The case presented demonstrates that healthy coping with pain and stress may be most successful and sustainable when one is involved in a supportive relationship with someone who also practices psychological flexibility skills and when both partners use relational flexibility skills during their interactions.

Keywords: chronic pain, couples, psychological flexibility, relational flexibility, couple-based interventions, couple therapy

Chronic pain is a costly public health problem that is associated with impaired functioning and poor quality of life across multiple domains (e.g., mood, sleep problems, interference in daily activities). Behavioral and cognitive-behavioral interventions have been developed to alleviate these problems and these approaches have had some success (Fordyce, 1976; Morley, Eccleston, & Williams, 1999; Nicholas, Wilson, & Goyen, 1992). Unfortunately, marital and interpersonal conflict interfere with the outcomes of psychological treatments for pain—almost 50% of people with chronic pain experiencing interpersonal distress drop out of individual interventions for chronic pain (Carmody, 2001), and individuals with chronic pain and interpersonal distress are less likely to benefit from these approaches even when they complete treatment (Edwards et al., 2007; Strategier, Chwalisz, Altmaier, Russell, & Lehmann, 1997; Turk, 2005; Turk, Okifuji, Sinclair, & Starz, 1998). Thus, current practice is limited in its ability to adequately meet the needs of couples in which chronic pain in one or both partners has contributed to individual and relational distress. To address this need, we developed an integrative couple-based psychological treatment to improve psychological flexibility (i.e., the ability to attend to and remain in the present moment, while also adapting to the environment in a way that is aligned with one’s values; Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010) and relational flexibility, which we define as the ability to interact with one’s partner, fully attending to the present moment, and responding in a way that serves one’s own and one’s partner’s values. Both psychological and relational flexibility skills are associated with greater relationship satisfaction, intimacy, pain adjustment, and well-being in couples (e.g., Barnes, Brown, Krusemark, Campbell, & Rogge, 2007; Laurenceau et al., 1998; Williams & Cano, 2014).

The psychological treatment described here is grounded in both cognitive-emotional models of chronic pain and models of close relationships. According to cognitive-emotional models, rigid styles of thinking and emotional experience contribute to pain and distress (Burns, Quartana, & Bruehl, 2008; Eccleston & Crombez, 1999). Psychological treatments have been developed to help people with pain disengage from these cognitive-emotive styles by teaching psychological flexibility skills including mindfulness (present-moment awareness and openness to experiences), acceptance (willingness to experience the full range of feelings and sensations), and values-based action (taking action to pursue meaningful, valued activities). Several of these mindfulness- and acceptance-based interventions for pain have been shown to improve pain, sleep, psychological distress (Davis, Zautra, Wolf, Tennen, & Yeung, 2015; Kabat-Zinn, 1982; McCracken, Gauntlett-Gilbert, & Vowles, 2007; Vowles, Wetherell, & Sorrell, 2009; Wetherell et al., 2011; Zautra et al., 2008), and even familial distress (Davis & Zautra, 2013). In addition, psychological flexibility appears to be the mechanism driving improvements in these interventions (Davis et al., 2015; Kabat-Zinn, 1982; McCracken et al., 2007; Vowles et al., 2009; Vowles & McCracken, 2008; Wicksell, Olsson, & Hayes, 2010; Zautra et al., 2008).

However, intervening in the social context is also critical in pain as coping with health stressors is best achieved in the context of a satisfying and supportive relationship (Baucom, Kirby, & Kelly, 2009; Revenson, 1994; Sullivan & Davila, 2010). Indeed, satisfaction with one’s relationship is associated with health (Robles, Slatcher, Trombello, & McGinn, 2014) and satisfaction with an interaction with one’s romantic partner is associated with reduced pain intensity (Corley, Cano, Goubert, Vlaeyen, & Wurm, in press). Emotional disclosure and empathic responsiveness appear to be key interaction behaviors that allow people to cope with pain and pain-related distress (Cano & Goubert, in press; Cano & Williams, 2010). These relational flexibility skills are important components of close relationships models such as the intimacy process model (Reis & Shaver, 1988), which states that partner responsiveness to disclosures is necessary to build intimacy and well-being in couples. Indeed, partner responsiveness is correlated with better relationship adjustment in community couples (Laurenceau et al., 1998; Laurenceau, Barrett, & Rovine, 2005). Disclosure and empathic responses are also associated with less pain and greater relationship adjustment in couples with pain (Cano, Barterian, & Heller, 2008; Cano, Leong, Williams, May, & Lutz, 2012; Leong, Cano, Wurm, Lumley, & Corley, 2015). In contrast, a lack of relational flexibility in the form of unhealthy patterns of disclosure, criticism and emotional invalidation, and a lack of empathic and validating responses contribute to pain and depressive symptoms in couples with pain (Burns et al., 2013; Cano et al., 2008; Cano et al., 2012; Cano & Williams, 2010; Johansen & Cano, 2007; Leong et al., 2015; Leong, Cano, & Johansen, 2011) and relationship dissatisfaction, depressive symptoms, and biomarkers of stress in community couples (Hooley & Teasdale, 1989; Laurenceau et al., 1998; Slatcher, Selcuk, & Ong, 2015). Couples therapy approaches that include emotional disclosure and empathy skills building, such as Integrative Behavioral Couples Therapy, contribute to gains in acceptance of partner, tolerance building, communication, and relational problem-solving skills (Christensen, Atkins, & Baucom, 2010; Christensen, Jacobson, & Babcock, 1995).

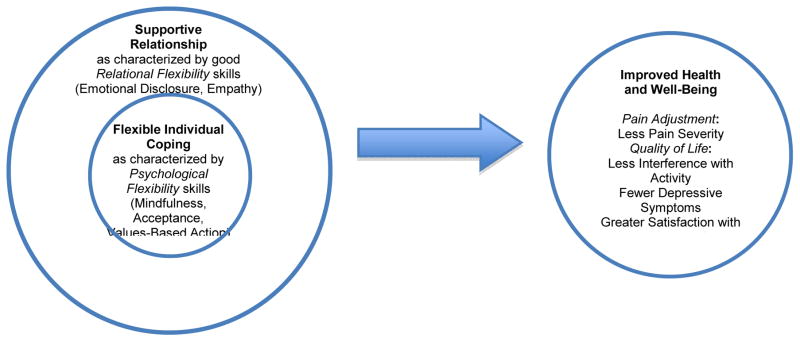

The empirical and conceptual evidence suggests that flexible and adaptive coping is needed at both the individual and the relationship levels to promote health and quality of life (see Figure 1). In other words, psychological and relational flexibility skills must be exercised by both partners in order for individuals with chronic pain and their partners to reap the benefits of psychological treatments. Following the model in Figure 1, the treatment is aimed at alleviating pain and suffering by promoting couples’ psychological and relational flexibility skills. Currently, there is no integrative psychological treatment that fully harnesses the power of the couple, treating both the individual with chronic pain and his/her spouse as two individuals who are each in need of developing greater psychological and relational flexibility to improve their own and their partners’ health.

Figure 1.

Integrative model of psychological and relational flexibility.

Psychological flexibility skills must be exercised within the context of a supportive relationship in order for patients to reap the benefits of psychological treatments for pain.

In addition to the application of this conceptual model, our approach is distinct from other psychological treatments for chronic pain because both partners are active participants in the intervention. This means that the current treatment enables each partner to individually benefit from the treatment to promote system-level change that may enable each partner to support individual and relationship skills building.

As noted above, psychological flexibility skills are associated with reduced pain and distress in people with pain. Partners are also likely to benefit from learning these skills for two reasons. First, living with a loved one who has a chronic illness can introduce stress. In particular, some partners experience declines in relationship satisfaction, increases in depressive symptoms, and increased burden associated with performing more physical labor around the house as well as logistical and financial stressors associated with their partners’ care (Flor, Turk, & Scholz, 1987; Leonard & Cano, 2006; Miaskowski, Zimmer, Barrett, Dibble, & Wallhagen, 1997). Second, partners may benefit from learning psychological flexibility skills to cope with their own stressors outside the pain (e.g., employment stress). Just as mindfulness- and acceptance-based interventions result in decreased psychological distress among individuals not facing chronic illness (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006; Öst, 2014; Powers, Zum Vörde Sive Vörding, & Emmelkamp, 2009), partners’ participation in such approaches may help reorient them to valued behavioral goals and learn coping strategies to directly improve their own well-being.

Furthermore, each individual may benefit when the other partner practices psychological flexibility skills. Conceptual models note that spousal behavior can affect chronic pain treatment gains for better or worse (Fordyce, 1976; Kerns & Otis, 2003; Turk, Meichenbaum, & Genest, 1983). Research has shown that the partner’s psychological inflexibility is associated with their own pain, their partner’s chronic pain, and depressive symptoms (Leonard & Cano, 2006). In contrast, spouses’ mindfulness was related to spousal support behaviors towards individuals with chronic pain even when controlling for that individual’s mindfulness (Williams & Cano, 2014). Similarly, Barnes et al. (2007) found that one partner’s mindfulness was related to less anger and hostility in their romantic partner after a conflict discussion. These results suggest that actively engaging both partners in learning psychological flexibility skills that are aligned with their values may help support the other partner in their attempts to use mindful and flexible coping strategies for pain and stress. Additionally, attending to both partners’ psychological flexibility may result in larger, and perhaps more persistent, gains than involving only the individual with pain. Thus, the current intervention teaches psychological flexibility skills to both partners.

Finally, relational skills are best learned and put into practice when both partners are actively involved in treatment. Couple-based interventions for pain are predominantly partner-assisted treatments, in which the focus is on the person with pain and with the partner acting as a coach who can reinforce pain-coping skills. Unfortunately, they appear to have either small or no incremental benefits above individual psychological treatments (Martire, Schulz, Helgeson, Small, & Saghafi, 2010). Closer to the novel treatment approach described in this article are couples therapies such as CBCT for posttraumatic stress disorder (Monson, Stevens, & Schnurr, 2005), anorexia (Bulik, Baucom, Kirby, & Pisetsky, 2011), depression (Bodenmann et al., 2008; Cohen, O'Leary, & Foran, 2010), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (Abramowitz et al., 2013). However, these couple interventions do not regard the partner’s individual coping skills as a target of treatment as well. Furthermore, the current psychological treatment, while borrowing some techniques from traditional cognitive behavioral approaches to couples therapy such as instruction in direct communication and turn-taking (Baucom, Shoham, Mueser, Daiuto, & Stickle, 1998; Gurman, Lebow, & Snyder, 2015; Hahlweg et al., 2009), is more akin to ACT and mindfulness-based couples approaches, which emphasize emotional awareness, acceptance of the other, and emotional responsiveness (Christensen et al., 2010; Harris, 2009). The intervention described here teaches each spouse not only how to recognize and manage their own distress with psychological flexibility skills but also how to apply these skills to choose how and when to communicate their distress as well as how to mindfully and empathically respond to their partner’s distress (i.e., better relational flexibility).

In sum, there is great potential for an integrative psychological treatment that directly targets the psychosocial inflexibility often found in people with chronic pain and their spouses. We next describe the novel integrative couple-based treatment, entitled “Mindful Living and Relating” because the treatment is aimed at alleviating pain and suffering by building psychological and relational flexibility skills in both spouses. Mindfulness, values-based action, and mindful communication exercises were used to enhance each partner’s individual and relational flexibility skills. Some of the mindfulness meditation and values exercises included in this treatment have been used in other psychological treatments (e.g., breathing meditations, body scans, values clarification exercises; Dahl & Lundgren, 2006; Hanh, 1999; Kabat-Zinn, 1990). However, they have not been applied to the problems facing couples with chronic pain and relationship distress, nor have they been packaged together with the other exercises developed specifically for this intervention (e.g., mindful handholding, relational flexibility exercises) in such a way as to address the psychological and relational inflexibility that many couples with pain experience. Then, we present measures completed in the context of our treatment development study, followed by a case illustration. The study was approved by the university’s IRB and couples provided informed consent to participate in the study. The intervention was administered in a department of psychology at a large midwestern university campus in an urban setting.

Intervention Description

Mindful Living and Relating consisted of six (6) 1.5-hour sessions with individual couples and was delivered by master-level therapists in clinical psychology or social work. Therapists had training and experience in individual and conjoint therapy as well as cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based techniques, and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. However, training in all of these approaches is not considered necessary to deliver the intervention. Therapists received training prior to intervention delivery, which consisted of reviewing and discussing the treatment manual as well as background readings including literature cited in the introduction of this paper. Therapists also participated in weekly group supervision led by the first author and relied on the treatment manual, which is available upon request from the first author. Supervision sessions included discussion of session material and listening to audio recordings of the sessions. See Table 1 for an outline of sessions.

Table 1.

Outline of Sessions for Mindful Living and Relating

| Session 1 | ||

Objectives

| ||

| Psychological Flexibility |

In-Session Work

|

At-Home Practice

|

| Session 2 | ||

Objectives

| ||

| Psychological Flexibility |

In-Session Work

|

At-Home Practice

|

| Session 3 | ||

Objectives

| ||

| Psychological Flexibility |

In-Session Work

|

At-Home Practice

|

| Session 4 | ||

Objectives

| ||

| Psychological Flexibility |

In-Session Work

|

At-Home Practice

|

| Relational Flexibility |

|

|

| Session 5 | ||

Objectives

| ||

| Psychological Flexibility |

In-Session Work

|

At-Home Practice

|

| Relational Flexibility |

|

|

| Session 6 | ||

Objectives

| ||

| Psychological Flexibility |

In-Session Work

|

|

| Relational Flexibility |

|

|

| All Elements |

|

At-Home Practice

|

Session 1

Session 1 began with the Oral History Interview (Buehlman et al., 1992), which was adapted for the current study to include questions about pain (e.g., “How do you think your pain/your partner’s pain impacts your relationship?”, “How has his/her or your pain affected: the time you spend together? What you talk about? Who does the chores or how they are done? Time spent with kids, family, and friends? Hobbies or leisure time?”). The purpose of this interview was twofold. The interview allowed the therapist to understand the couple’s shared history and experience of pain while also providing an opportunity for the couple and the therapist to build a working alliance to foster acceptance of and engagement in the intervention.

After the interview, the therapist provided an overview of the intervention and a rationale for the order of the sessions. An excerpt of the rationale is as follows: “The first set of skills (Sessions 1–3) focus on ways you can relax and calm your body, take stock of what you value, and make a plan for pursuing goals. These are called ‘psychological flexibility’ skills because they help you build and strengthen your ability to cope with pain and stress and live the life you want to live. You will then build on the psychological flexibility skills by working on a second set of skills called ‘relational flexibility’ skills (Sessions 3–6), which are aimed at developing and strengthening healthy communication skills. This order of skills training was chosen because healthy individual coping is often needed so that couples can support and respond to each other in a healthy way.” See Supplemental Information for a sample handout.

The couple was then introduced to their first mindfulness exercise: a breathing meditation. This exercise is often used as an initial meditation to introduce the concept of mindfulness (Kabat-Zinn, 1982). In the present intervention, it was included to enhance mindfulness and acceptance for each individual in the couple. Although the couple was guided through this meditation together, mindfulness meditation was an individual practice. The couple was provided a rationale for practicing mindful breathing, which included its utility in centering one’s attention to the present moment. Each individual was instructed to focus the attention on their own breath and to notice it without changing it. Additionally, the couple was guided to nonjudgmentally notice when their focus had wandered away from the breath and to gently guide their focus back to their breath. After the couple was guided through this meditation, each individual’s experience of the meditation was discussed to address challenges and clarify the practice of this exercise. This type of discussion followed each experiential exercise to ensure that couples understood the instructions and address any questions or concerns. The couple was asked to practice the breathing meditation at least once per day before the next session, which was the suggested frequency for at-home practice of the various meditations throughout the treatment. As previously noted, because this exercise was not a joint activity, the couple was not directed to complete the meditations together, nor were they asked to refrain from joint practice. The couple also had the option of using an audio recording to guide their practice.

Also in Session 1, the couple was introduced to a values clarification exercise based on acceptance work for couples (Harris, 2009) to help both individuals to explore what is important and meaningful to them as an individual and as a couple. Values clarification was included in the initial session for several reasons. Values-based work is especially critical for individuals with chronic pain and their partners because chronic pain often causes significant interference in the couple’s life that derails efforts to live a meaningful life. Many individuals and partners facing chronic pain become so focused on chronic pain that their thoughts and behaviors become defined by pain. Opportunities for social reinforcement are reduced, which can lead to greater individual and relationship distress. The inclusion of values work early in treatment ensured that both partners identified valued goals that they could continue to pursue throughout the treatment and, moreover, help the therapist and the couple to fit all subsequent work into the grander scheme of building a meaningful life, thus contributing to early commitment to the treatment.

The first values exercise selected for Mindful Living and Relating included an adaptation of an imaginative exercise in which each individual was asked to imagine attending a celebration for their anniversary 10 years from now (e.g., a couple married 15 years would imagine their 25-year anniversary; Harris, 2009). Each partner was instructed to imagine his or her romantic partner giving a speech about the last 10 years of their life together, including statements that the partner might say about what the imaginer meant to the partner. In line with individual values-based imagination exercises (Dahl & Lundgren, 2006), each individual was also asked to imagine that other people from different areas in their life (e.g., family relationships, social relationships, work, health, etc.) also comment about the imaginer’s strengths and contributions in various domains of life. It was emphasized that this imagination exercise focuses on what the person ideally would like to hear about themselves in various domains, rather than what might realistically be said. The couple was provided the instructions for this exercise in session and asked to complete this imaginative exercise, record their responses, and discuss the exercise with each other after both had completed it individually at home. They were asked to bring their responses to Session 2. This specific exercise was included because it was aimed at helping individuals identify values in their lives without any requisite knowledge about the concept of values. Thus, this exercise is an excellent starting point for learning about and exploring values.

Session 2

Session 2 and each session thereafter began with experiential practice of the mindfulness meditation that was taught in the previous session, sharing of individual experiences of the meditations, and a review of the practice over the week. The therapist helped the couple troubleshoot obstacles to practice and highlighted positive benefits from the practice.

After the review of the breathing meditation that was presented in Session 1, the therapist introduced the body scan meditation, which is a mindfulness exercise that guided the individual to bring attention to each area of the body, one area at a time, starting with the toes. As with the other meditations in this intervention, the therapist emphasized a nonjudgmental and present-moment focus. Participants were instructed to gently bring their attention back to the area of focus whenever they found that their mind had wandered. This meditation was included to help both partners continue to build mindfulness and acceptance skills, including the ability to focus on the present moment in a nonjudgmental manner. Further, this exercise was chosen because it is common for people with pain to avoid feeling pain or focusing on pain to the exclusion of other sensations (Eccleston & Crombez, 1999; Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000). The body scan meditation is aimed at developing awareness of all bodily sensations.

The anniversary values clarification homework was then reviewed. The therapist addressed questions about the exercise and helped each individual in the couple to further clarify their values by summarizing and reflecting back valued themes in each individual’s imagination exercise. Following this review, the couple was given instructions on the next values-based homework: developing values statements and completing a values compass. In this activity, each individual in the couple was asked to write down statements that reflected their values in the same 10 domains that were used in the anniversary exercise (e.g., relationship with your partner, leisure, citizenship, etc.). Creating values statements helped each individual in the couple to further clarify values. The second part of this activity, the values compass, involved rating the extent to which each value statement was important to them and the extent to which they were currently living out each value statement (i.e., 2 ratings per values statement, both ratings on a scale from 0 to 10). The values compass helped each partner to identify valued goals to pursue during the course of the treatment. This exercise was begun in session and guided by the therapist. The couple was then instructed to discuss their responses with their partner after they completed the exercise at home and to bring their responses to the next session.

Session 3

Recall that in Sessions 2 through 6, the first segment of the session always included a review followed by the introduction of new skills. The new elements in the third session included the leaves-on-a-stream meditation and developing values-based behavioral goals. The leaves-on-a-stream meditation, a classic ACT exercise (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999), involves bringing attention to thoughts by imagining a gently flowing stream with leaves floating on the surface of the water and allowing each thought or feeling that arises to gently land on a leaf and let it flow by. Multiple mindfulness exercises were introduced and practiced over the course of the intervention to allow the couple to build on their skills and identify, with practice, the mindfulness exercises that best suited each partner (i.e., a “toolbox” approach). It was reasoned that a one-size-fits-all approach would not be appropriate when working with two individuals who may have different experiences and needs.

The couple also began developing values-based goals in this session. In this activity, each person was asked to identify the top three values from their values compass assignment in Session 2 with the greatest discrepancy between their rated importance and their rated current fulfillment. For each of these three values, the individual was asked to develop up to three concrete, specific goals that would bring them closer to living out these values, potential obstacles to completing such goals, and plans for dealing with those obstacles. Each individual in the couple was asked to complete the exercise individually at home prior to discussing it as a couple. The couple was not directed to identify a relational goal although it was expected that many couples would indeed identify personal and relational goals.

Session 4

In this session, the couple was introduced to a joint mindfulness exercise: mindful handholding. Unlike the previous meditation exercises in this treatment, this exercise was a dyadic mindfulness exercise. In this meditation, the couple was instructed to hold hands and bring present-moment focused attention to the experience of holding their partner’s hand. For example, each partner could notice the weight of the partner’s hand and the texture and temperature of the skin. Anytime their minds wandered from this mindful task, they were instructed to bring their attention back nonjudgmentally to the feel of their partner’s hand in their own. This dyadic mindfulness activity was introduced after the couple had some experience with individual mindfulness exercises and was designed to help partners attend to each other intimately in preparation for the mindful interaction exercise to be introduced later in the session.

As in the other sessions, the therapist reviewed previous values homework to ensure that the couple was keeping on track with valued-based action. To continue each individual’s values-based work, each partner was asked to choose one goal from each of their values-based goals and plan a time and day to complete the goal before the next week’s session.

Additionally, this session introduced a mindful listening and positive emotional disclosure activity. The couple was taught the importance of communicating emotions to each other. Each individual was asked to reflect on any positive feelings they had about their partner that day, whether or not the partner was present. The therapist guided the couple in sharing positive emotions and mindfully listening to their partner. Individuals were provided a list of words to assist them in better describing and identifying their emotions so that they could be as specific as possible (e.g., “I felt full of joy” vs. “I felt good”). Partners also shared the situation that prompted that emotion (e.g., an interaction, observing one’s partner in a task, thinking about one’s partner). When disclosing an emotion, individuals were asked to allow their partner to respond and to use mindful awareness when listening to one’s partner respond. The spouse receiving the disclosure was asked to be fully present to the partner by applying mindful awareness skills to the interaction, which included listening, making eye contact, recognizing distractions and nonjudgmentally returning attention to the partner’s responses, refraining from interrupting, and taking a mindful breath before responding to one’s partner. The spouse receiving the disclosure was then instructed to respond with empathy (e.g., reflecting back the emotion or thoughts) and/or gratitude (e.g., “Thank you for sharing that with me.”). Each individual practiced both the speaker and the listener roles before leaving the session. After the in-session practice, the couple was instructed to continue to record at least one partner-related positive emotion each day for 3 days and then begin daily sharing of these positive emotions with each other on the fourth day. This exercise was designed to help couples identify positive emotions regarding their partners and to provide couples with practice of relational flexibility skills in a safe context: disclosure, mindful listening, and mindful responding about nonthreatening emotions.

Session 5

A loving-kindness meditation was introduced in this session. In this meditation, each individual was guided to silently express wishes for themselves and their romantic partner of kindness, compassion, and freedom from anger and pain. The exercise was practiced with both partners together, so although each partner was practicing this exercise individually, they were doing so conjointly. As with the previous session, homework was reviewed, including values-based goal completion and positive emotional disclosure. A new values-based goal was selected and to be completed during the week.

To build on the mindful communication skills introduced in Session 4, the couple was guided through a similar, yet often more difficult, interaction activity in which each individual was directed to disclose negative emotions arising from a painful or stressful situation while the other partner mindfully listened. The purpose of this activity was to help partners develop greater intimacy by sharing their feelings about pain and stress and providing and receiving emotional validation and support. When disclosing an emotion, the discloser was directed to refrain from lodging complaints towards each other, but rather, share difficult emotions that were experienced from other life stressors or pain with the goal of obtaining support from the partner. As with Session 4, each partner practiced discloser and listener roles and the therapist provided feedback to the couple about their emotional expression and mindful listening skills. After practicing this task in session and receiving guidance from the therapist, the therapist instructed each individual to record their negative feelings about pain or stress in their life for 3 days and then begin daily sharing on the fourth day.

Session 6

In addition to a review of Session 5 material, the final session of the treatment included the development of an action plan for the couple. Each partner identified specific exercises they wanted to continue to practice and identified their rationale for choosing those exercises to bolster motivation. Each partner also noted the frequency of the exercises, potential barriers, and solutions to create a committed action plan.

Measures

Couples completed the following measures prior to Session 1 and within 1 week of completing the intervention:

Pain Severity

A numerical rating scale was used to assess average pain over the last 24 hours on a 0 (no pain) to 10 (pain as bad as you can imagine) rating scale.

Depressive Symptoms

The 21-item Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck, Steer, Ball, & Ranieri, 1996) was used to assess depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks. Researchers (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) have categorized scores for descriptive purposes: minimal range (0–13), mild depression (14–19), moderate depression (20–28), and severe depression (29–63).

Relationship Satisfaction

The 32-item Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976) was used to assess relationship adjustment. A score below 97 is often used as an indicator of marital distress (Jacobson & Truax, 1991). Note, however, that researchers have also found that this cutoff may overclassify couples as discordant compared to interview measures of satisfaction (Heyman, Feldbau-Kohn, Ehrensaft, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, & O'Leary, 2001).

Intimate Partner Violence

The 4-item HITS (Hurt, Insult, Threaten, and Scream), Short domestic Violence Screening Tool (Sherin, Sinacore, Li, Zitter, & Shakil, 1998) was used to screen for intimate partner violence. If either participant reported the presence of physical violence within the last year, the couple was excluded from the study and referred out.

Case Illustration

Kathy and Nick1

Kathy, age 62, and Nick, age 65, were married for 37 years and identified themselves as heterosexual, White, and practicing nondenominational Christians. The couple resided in the suburbs of a large metropolitan area in a midwestern state in the United States. They have an adult daughter living in another state with whom they had a good relationship. Nick received a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering and Kathy stated that she had a high school diploma. Both are now retired. They reported an annual household income of $55,000. The couple learned about the intervention through Kathy’s physician, who had fliers about the program. The couple attended the Mindful Living and Relating sessions in a psychology research laboratory at a local university.

Kathy reported diagnoses of fibromyalgia and osteoarthritis. Her fibromyalgia began shortly after the birth of her daughter, when she was in her 20s, and her osteoarthritis began when she was in her 50s. Nick reported that he had pain from time to time (e.g., due to excessive yard work or occasional tension headaches) but that it was not chronic in nature. Kathy used acetaminophen and hydrocodone to control her pain. Kathy rated her current pain as a 7 on average. She also reported that her pain limited activities that she once found enjoyable; in the last 5 to 10 years Kathy spent less and less time riding her bicycle and going out to musical events with her husband because of her pain. She reported that she was afraid her pain might get worse if she rode her bicycle or if she had to sit at an event for more than 30 minutes. She also reported eliminating some valued social activities because of the pain, such as volunteering at a soup kitchen because the standing took a toll on her knees and attending church services because of the need to stand up, kneel, and sit repeatedly. Because of these activity changes, Kathy reported not seeing her friends as often as she would like. Further, Kathy retired from a part-time job as a receptionist 3 years ago, in part because of the pain, and in part to spend more time with her husband who was also retired. These changes contributed to a decrease in Kathy’s social interactions.

Nick also reported that while he did not have chronic pain, he too limited his activities because of his wife’s pain. He no longer attended musical events because “I don’t want to go without her” and refrained from asking her to go to events that required long periods of sitting or standing. Instead, he spent time watching television and going for walks in the neighborhood. He also began taking over the cleaning and gardening chores that Kathy once did. He reported that he came to enjoy gardening but that cleaning was a burden to him. As a recent automobile engineer retiree, Nick had been trying to find fun things to do but reported that “I have not found my calling yet.” He reported having a few friends who were still working and with whom he got together for lunch twice per month but they were not as available as he was at the time.

The couple reported that they were highly committed to their relationship but that they were not as happy as they used to be, in part because of the pain and its impact on their lives. Specifically, Kathy received a score of 90 on the DAS, indicating marital distress, and Nick received a score of 98, which was one point above the cutoff typically used to indicate marital distress; thus, the couple reported some marital discord. They each reported depressive symptoms on the BDI-II, with Kathy scoring 25 (moderate symptoms) and Nick scoring 15 (mild symptoms). The couple denied having serious arguments and denied intimate partner violence on the HITS. However, they avoided talking about topics that might arouse sadness or anger in the other partner, a pattern that was present since their early years of marriage but that was exacerbated by Kathy’s pain and Nick’s recent retirement. Each partner also reported that they felt somewhat disconnected from each other both emotionally and sexually. They reported expressing little physical affection toward one another and that they had sexual intercourse about once every other month, which was much less frequent than the once per week frequency approximately 5 years prior. The couple cited pain and growing apart as reasons for their infrequent sexual intercourse.

Case Formulation

Mindful Living and Relating was ideal for this couple for several reasons. First, Kathy reported that chronic pain interfered with her daily activities as well as valued activities, some of which were activities in which she engaged in alone or with others and some of which were activities in which the couple participated. Second, Nick also reported that he had not been engaging in valued, enjoyable activities, in part because of Kathy’s pain but also as a consequence of his retirement. Both partners reported some depressive symptoms. Thus, both partners could benefit from an approach that would help them each identify their values and corresponding activities to live a meaningful life. Third, the couple reported some distress in their marriage but still remained committed to each other. Thus, they were willing to enter into the treatment in a good-faith effort to develop pain coping skills and improve their relationship. The absence of intimate partner violence also indicated that the couple could engage in the activities safely. It is important to note that another option could have been to focus on Kathy’s pain coping skills and to enlist Nick as her coach. However, both partners reported growing apart from each other. Nick saw some of his role in helping to manage Kathy’s pain as a burden. In addition, Nick was having some struggles of his own (i.e., depressive symptoms, loss of valued activities). While treating Nick as a coach might result in some benefits to Kathy, it would also represent a missed opportunity because Nick would not get a chance to develop his own psychological flexibility skills. With one partner serving as a coach, the couple would not be able to practice relational flexibility skills together to enhance their relationship and support each other in their attempts to learn psychological flexibility skills. The approach described here aims to influence each partner as well as the system within which they live, thus contributing to healthier outcomes for both partners.

Treatment

The couple initially expressed some skepticism towards the treatment; they wondered how couple therapy could help Kathy with her pain. The therapist provided the rationale for the couple-based intervention, including how the initial sessions were aimed at helping each partner learn skills to cope with their own pain and stress so that the couple could better attend to each other’s needs. Each partner accepted this explanation and expressed a willingness to engage in the treatment. The following section focuses on the key intervention components, including positive experiences and obstacles.

Psychological Flexibility Skills

Mindfulness

As shown in Table 1, treatment initially addressed individual mindfulness skills. Kathy was especially excited about the mindfulness exercises as she had had exposure to meditation in yoga classes. In each of the first 3 sessions, the therapist introduced the mindfulness exercises as a way to be more present-centered and nonjudgmental and walked the couple through the exercises. Kathy reported feeling more relaxed and having less pain after doing the meditations. However, she reported difficulties with the body scan, introduced in Session 2, as it often increased her awareness of her body and her pain, the latter of which she was trying to avoid. The therapist encouraged her to attempt the exercise with a mindful spirit, noticing rather than avoiding the pain. The therapist was also able to help Kathy recall times when her pain avoidance led her to forgo something enjoyable. Kathy was able to see the value of “sitting with” her pain rather than avoiding it. Still, she reported enjoying the other meditations to a greater extent, and the therapist encouraged her to use the mindfulness tools that best suited her and her situation. In other words, the therapist modeled a willingness to experience yet maintained a nonjudgmental stance.

Nick reported some difficulty engaging in the breathing meditation, which was introduced in Session 1. He stated that he became frustrated because he could not successfully “block out” his thoughts. The therapist recognized that Nick misunderstood the purpose of mindfulness and so she further explained that the exercises were not meant to “erase” thoughts but to simply notice thoughts and to return attention to breathing without judgment, even if he had to return his attention 100 times. Thus, he was instructed to note his thought as it occurred (e.g., “I’m frustrated that I cannot block out my thoughts”) and simply return to his breathing. Once Nick understood this principle, he was able to engage in the mindfulness exercises and reported a greater sense of ease while doing so. At one point, he began to use them to go to sleep in the evening. While this was not discouraged, the therapist underscored the importance of doing the meditations at other times of day as well so that he could benefit from the practice while he was awake. Of all the mindfulness exercises, Nick preferred the leaves-on-a-stream exercise (Session 3) because he reported that the images of the leaves helped him remain more present-focused and accepting of his thoughts while also being able to let them go: “It was a good way to see problems floating away from you.”

Both partners discussed their experiences of their individual mindfulness practice each week. In addition, the couple reported that the partner-based mindfulness exercises of mindful handholding (Session 4) and loving-kindness meditation (Session 5) were particularly enjoyable because they were doing something together that fostered intimacy in a gentle manner. They stated that they looked forward to the mindful handholding exercise each day.

Values

At Session 2, the couple reported that the anniversary exercise was challenging because they had not done such an imaginative exercise before; however, after the initial challenge, they reported that they enjoyed this activity because it helped them take a step back from their normal routine. Kathy noted that she wanted to be remembered as a loving wife and an avid gardener who liked to tend to others’ needs. Nick stated that he wanted others to think of him as a “people person” who made others laugh. Together, the couple also reported that they wanted to be remembered as a couple that stayed together “through thick and thin” and were considered best friends. Kathy expressed sadness and sorrow upon realizing how these desires were not aligned with her behaviors. Nick was able to support his wife while also stating that he too realized through the exercise that he was not leading his life the way he envisioned.

The therapist validated these feelings, stating that this exercise often surprises people but that it also provides couples with a way forward; every day offers a new opportunity to live out one’s values. She then provided instruction to the couple to develop one to two values statements that articulated their desires. As part of their at-home practice after Session 2, the couple completed values statements for multiple domains of their lives (e.g., family, friends, couple, leisure time). During the review of values statements in Session 3, the therapist realized that the couple had begun to confuse values (i.e., desired ways of living) and goals (i.e., specific activities that align with identified values). For instance, Kathy’s value statement concerning leisure was actually a goal statement: “I want to spend 2 hours in my garden each week.” The therapist worked with the couple to differentiate values from goals by clarifying that goals were specific and measurable and then exploring why certain activities brought joy or fulfillment. For instance, Kathy’s love of gardening stemmed from an interest in beauty and the outdoors (e.g., “I value beautifying my surroundings.”). Once the couple understood this distinction, they were able to rework their values statements to accurately reflect values, rather than goals.

After fully developing values statements for multiple domains in their lives, the therapist assisted the couple in selecting areas on which to focus. Kathy and Nick were instructed to rate the importance of each domain in their life and the extent to which they were living out that domain in their life, both on a scale from 0 to 10. Goals were developed for the domains with the largest discrepancies. For Kathy, while her romantic relationship and leisure activities were highly important to her (10 and 9, respectively), she noted that she was not living out these values (6 and 4, respectively). Similarly, Nick indicated that his romantic relationship (10) and friendships (9) were very important to him, but that he was not living his life in accordance with his values in these domains (7 and 3, respectively). To address the valued domain of their romantic relationship that they both shared, Kathy and Nick’s values in regards to the relationship were further discussed. Kathy valued being a loving and responsive partner, and Nick valued being a partner who is fun to be around, trustworthy, and reliable. They both reported that they valued closeness and intimacy with each other. Jointly, they created a goal to spend 15 minutes each day with each other, listening to music or gardening when the weather permitted. Kathy also identified a goal to ride her bicycle for 15 minutes, 3 times per week. Nick’s second goal, tied to his value in the friendship domain, was to call two friends to invite them to go to a baseball game in the next month.

These goals were further detailed, and potential barriers and solutions were discussed. For instance, Nick thought a barrier was that both of his friends might not want to go, or that they would not be able to find a time that worked for everybody’s schedule. The therapist reinforced the importance of returning to values for guidance when faced with barriers, and Nick identified that simply reaching out to his friends to talk would be moving in the direction of his values. Beginning in Session 4, the couple began to select a values-based goal to complete each week. Both partners reported satisfaction with completing the values-based goals and a desire to build upon these goals. For example, Kathy and Nick wanted to set aside more time to garden with each other and listen to music. While they noted that listening to music at home was not the same as going to concerts like they used to, it was meaningful to again share that hobby.

Relational Flexibility Skills

In Session 4, the therapist introduced Kathy and Nick to mindful relating skills. Kathy and Nick expressed a deep interest in this component. During the mindful relating skills practice, each partner took turns in the “speaker” and “listener/responder” roles. Initially, Nick found it difficult to identify his emotions when asked to identify a positive emotion related to a pleasant interaction with his wife. At first, he identified his emotions as simply “good” or “nice.” The therapist supplied both partners with a list of feeling words and encouraged each person to identify the specific emotion that was experienced. With some practice during session and at home, Nick reported greater comfort and ease using feeling words to describe the positive experiences that he had with his wife. Specifically, he described that one morning, Kathy made him a simple breakfast and he felt appreciative because this showed her concern for him. For her part, Kathy was able to listen mindfully to Nick and accept his gratitude. Through this simple interaction focused on a positive experience with one’s spouse, the couple reported that they felt closer to each other than they had in a long time.

The therapist built upon these mindful relating skills in Session 5 by explaining that it is normal for negative emotions to arise in the course of everyday life and that disclosing them to one’s partner may be effective in coping with stressful situations, including pain. Kathy and Nick expressed some hesitation about this task because they reported a pattern of avoiding difficult conversations and negative emotions. As a precautionary instruction, the therapist emphasized that the purpose of the negative emotion disclosure exercise was not to “lodge complaints” against a spouse but to share stressful experiences as they relate to pain or other life domains in an effort to gain support and emotional validation from one’s spouse.

The couple agreed to try the exercise. Kathy explained to Nick that she felt worried because her pain increased in intensity over the past week. At first, Nick began to tell Kathy not to worry. However, the therapist was able to discuss the meaning of statements such as this. In Kathy’s view, “don’t worry” sent the message that Nick did not want to hear about her experience. Nick was able to state that he did not intend to send that message but that he was at a loss as to how to respond in an empathic manner to Kathy. The therapist worked with the couple to identify Kathy’s need (i.e., validation) and construct an alternative response. Nick was able to then validate Kathy’s worry by stating, “I understand why you would be worried because the last time your pain flared up, you could not leave the house for a month. Is there anything I can do to help?” Kathy responded with appreciation of Nick’s validation, and clarified that she did not need assistance for her pain but that Nick’s concern was helpful enough. Nick said that this exercise motivated him to “start looking at things from Kathy’s point of view” rather than just his own. When the couple reversed roles, Nick shared that he felt angry about an interaction in the last week when his physician told him rather gruffly that Nick should “lose some weight if you want to see 70.” Kathy reflected back that she was surprised that Nick had not talked about this experience sooner and validated that his anger was normal. Nick voiced that he was afraid to share this sooner because he was worried that she would take the “doctor’s side,” but that he now felt relieved that his wife was on his side. In the final session, Nick and Kathy shared that the mindful relating skills helped them to listen to and attend to each other better, and share in each other’s emotional experiences to a greater extent. In turn, they reported that they were beginning to regain some of the closeness they had lost over the years.

Planning and Goal Setting

In the last session, Kathy and Nick identified a number of exercises that they wanted to continue to practice. Kathy stated that she wanted to continue to do the mindful breathing exercise daily “even for a minute or two” because it helped her reduce her pain in the moment as well as made her feel more “centered and relaxed.” She also wanted to practice listening mindfully to Nick because she believed it was helping them “reconnect” and understand one another. Nick also saw value in sharing difficult emotions with Kathy and “checking in” with his emotions so that they continued to live out the shared value of having a close romantic relationship. Both partners reported a desire to continue to spend more time together and to seek out shared goals like listening to music together, or attending a concert or social outing once a month. Nick also noted that he wanted to continue to engage in mindful breathing “to overcome stress” and the leaves-on-a-stream mindfulness exercise “to relax my mind” daily. Finally, both partners commented that they had seen improvement in each other at the end of the intervention. Kathy remarked that Nick appeared to be more cheerful and active while Nick reported that Kathy appeared to be more sociable and talkative.

Follow-up

Approximately a week after the treatment concluded, the couple was interviewed about their experience with the intervention. Both partners reported that they were highly satisfied with the couple-based treatment, including the individual sessions, session progression, and session number and duration. They each independently reported that they were pleasantly surprised that the intervention helped them in such a short period of time. At this assessment, Kathy’s pain and both partners’ relationship distress and depressive symptoms scores were reassessed. Kathy reported that her average pain was a 5 on a 0- to 10-point scale, which could be considered a minimal improvement from her baseline score of 7 (Farrar et al., 2001). She also reported that the skills were very helpful in accepting and reducing the impact of her pain in the moment. In addition, she reported that pain interfered with her activities to a much lesser degree and that she was able to engage in more pleasurable activities on her own and with her husband. Nick also reported that he had begun to engage with his friends more often and that he and Kathy had bought tickets to their first concert in years. Both partners also reported greater emotional intimacy and physical affection. Consistent with these qualitative reports, both partners reported decreases in psychological distress and increases in relationship satisfaction. Kathy scored an 18 on the BDI-II, a 7-point decline that put her in the mild range of symptoms (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), whereas Nick reported a more modest decline of 3 points, from 15 (mild depression) to 12 (minimal range). Kathy and Nick experienced improvements in relationship distress scores on the DAS; Kathy’s and Nick’s scores increased from 90 to 100 and 98 to 105, respectively, moving both partners into the “satisfied” range.

General Discussion and Future Directions

The couple-based psychological treatment described here, Mindful Living and Relating, was based on a novel integration and application of individual and dyadic approaches to alleviate chronic pain. While psychological treatments based on cognitive-emotional models of pain and dyadic models of coping have been developed for a variety of problems, these models have never been combined in an integrative manner. Unlike the majority of psychological treatments for pain, which either treat the individual in isolation or involve the partner as a coach, the current intervention included the spouse as an active participant who would personally benefit from the skills training. Involving both partners as active participants who could benefit from greater psychological flexibility also set the stage for a healthier relationship context for both partners. With regard to the case study, Kathy was able to learn skills that enhanced her ability to manage her pain and engage in valued activities alone and with Nick. Likewise, Nick learned psychological and relational flexibility skills that allowed him to address his own needs and reengage in valued activities. The couple's mindful communication activities built upon each partner’s developing psychological flexibility skills in mindfulness and value-based action to create a more flexible and satisfying relationship environment in which both partners could seek support from one another. It is hoped that Kathy and Nick continue to remind and reinforce each other’s newfound psychological and relational flexibility skills learned long after the intervention is over.

Research is ongoing to determine if increased psychological and relational flexibility are indeed the mechanisms by which this treatment works, and to examine the efficacy of this treatment to improve pain and quality of life. In addition to the measures described in this article to assess health and well-being, additional validated measures can be used to test hypotheses, including the Brief Pain Inventory (Cleeland, 1991), Multidimensional Pain Inventory (Kerns & Rosenberg, 1995; Kerns, Turk, & Rudy, 1985), McGill Pain Questionnaire (Melzack, 1975), and the Satisfaction with Life scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). Changes in psychological flexibility can be assessed with the Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire (McCracken, Vowles, & Eccleston, 2004); Pain Catastrophizing Scale (Cano, 2005; Sullivan, Bishop, & Pivik, 1995); Five Facet Mindfulness Scale (Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006); and Chronic Pain Values Inventory (McCracken & Yang, 2006). To assess changes in relational flexibility, a number of other measures can be used, including the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (Davis, 1980; self-reported empathy toward others), Perceived Partner Responsiveness (Reis, Clark, & Holmes, 2004; Reis & Collins, 2000; partner-perceived empathy), Ambivalence over Emotional Expression Questionnaire (King & Emmons, 1990) and Holding Back Scale (Pistrang & Barker, 1995; i.e., comfort with emotional expression), and observational tasks such as that used by Cano et al. (2012) to assess emotional disclosure and emotionally validating and invalidating responses. Other measures may need to be developed through qualitative data collection and analysis as work in this field continues.

Further research is also needed to address the suitability of this couple-based psychological treatment for people with different types or severities of pain. Likewise, research is needed to test the extent to which the intervention is suitable and acceptable for couples from different cultural and religious backgrounds, although the emphasis on values allows couples to integrate cultural and spiritual values into their work. It is expected that this treatment would be most appealing for the up to 47.4% of couples in which both partners report chronic pain problems (Issner, Cano, Leonard, & Williams, 2012). However, this intervention could also be used for individuals in which only one partner has chronic pain that is interfering with valued activities, as in the current case. While the intervention was developed for couples with individual and relational distress, for whom psychological and relational flexibility skills are most likely to promote change, it is likely that couples with no or minimal relationship discord may also benefit from this intervention. The use of master’s-level clinicians suggests that this intervention could be delivered in a variety of settings; however, couples would most likely be referred by primary care providers and/or pain specialists who observe that pain is interfering with valued activities and one’s relationships.

In sum, there is a great need for an integrative intervention that addresses the needs of couples for whom pain has contributed to individual and relational distress. The couple-based psychological treatment presented here was developed to provide psychological and relational flexibility skills training to couples to promote individual and relational well-being in the context of pain. Through this novel approach, both partners may learn sustainable skills to increase individual well-being, reduce pain interference, and enhance relationship well-being so that the impact of pain is minimized.

Highlights.

A novel psychological treatment for couples with chronic pain is described.

Both partners are treated as individuals within a relationship context.

The treatment targets psychological and relational flexibility in both partners.

Components include mindfulness, values, and empathic interaction exercises.

A case study demonstrates the need to treat both partners conjointly.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number R21AT007939. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Names were changed and details of the case were based on an amalgam of several cases so as to protect anonymity of individual couples.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abramowitz JS, Baucom DH, Boeding S, Wheaton MG, Pukay-Martin ND, Fabricant LE, Paprocki C, Fischer MS. Treating obsessive-compulsive disorder in intimate relationships: a pilot study of couple-based cognitive-behavior therapy. Behavior Therapy. 2013;44(3):395–407. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;12:27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S, Brown KW, Krusemark E, Campbell WK, Rogge RD. The role of mindfulness in romantic relationship satisfaction and responses to relationship stress. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2007;33(4):482–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00033.x. doi:10.1111/j.1752- 0606.2007.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH, Kirby JS, Kelly JT. Couple-based interventions to assist partners with psychological and medical problems. In: Halwehg K, Grawe-Gerber M, Baucom D, editors. Enhancing Couples: The Shape of Couple Therapy to Come. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe Publishing; 2009. pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH, Shoham V, Mueser KT, Daiuto AD, Stickle TR. Empirically supported couple and family interventions for marital distress and adult mental health problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(1):53–88. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri WF. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and –II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;67(3):588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory: Second Edition Manual. San Antonio, Texas: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, Plancherel B, Beach SR, Widmer K, Gabriel B, Meuwly N, Charvoz L, Hautzinger M, Schramm E. Effects of coping-oriented couples therapy on depression: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(6):944. doi: 10.1037/a0013467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehlman KT, Gottman JM, Katz LF. How a couple views their past predicts their future: Predicting divorce from an oral history interview. Journal of Family Psychology. 1992;5(3–4):295–318. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.5.3-4.295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik CM, Baucom DH, Kirby JS, Pisetsky E. Uniting couples (in the treatment of) anorexia nervosa (UCAN) International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2011;44(1):19–28. doi: 10.1002/eat.20790. dx.doi.org/10.1002/eat.20790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JW, Peterson KM, Smith DA, Keefe FJ, Porter LS, Schuster E, Kinner E. Temporal associations between spouse criticism/hostility and pain among patients with chronic pain: A within-couple daily diary study. Pain. 2013;154(12):2715–2721. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JW, Quartana PJ, Bruehl S. Anger inhibition and pain: conceptualizations, evidence and new directions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;31(3):259–279. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Barterian JA, Heller JB. Empathic and nonempathic interaction in chronic pain couples. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2008;24(8):678–684. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31816753d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Goubert L. What’s in a name? The case of emotional disclosure of pain-related distress. Journal of Pain. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.01.008. in press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cano A, Leonard MT, Franz A. The significant other version of the pain catastrophizing scale (PCS-S): Preliminary validation. Pain. 2005;119:26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Leong LEM, Williams AM, May DK, Lutz JR. Correlates and consequences of the disclosure of pain-related distress to one’s spouse. Pain. 2012;153:2441–2447. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Williams ACdC. Social interaction in pain: Reinforcing pain behaviors or building intimacy? Pain. 2010;149:9–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody TP. Psychosocial subgroups, coping, and chronic low-back pain. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2001;8:137–148. doi: 10.1023/A:1011309401598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A, Atkins DC, Baucom B, Yi J. Marital status and satisfaction five years following a randomized clinical trial comparing traditional versus integrative behavioral couple therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(2):225–235. doi: 10.1037/a0018132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A, Jacobson N, Babcock J. Clinical Handbook of Marital Therapy. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. Integrative behavioral couple therapy; pp. 31–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland CS. Pain Research Group. 1991. The brief pain inventory. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, O'Leary KD, Foran H. A randomized clinical trial of a brief, problem-focused couple therapy for depression. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41(4):433–446. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corley AM, Cano A, Goubert L, Vlaeyen JWS, Wurm LH. Global and situational relationship satisfaction moderate the effect of threat on pain in couples. Pain Medicine. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw022. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl J, Lundgren T. Living beyond your pain: Using acceptance and commitment therapy to ease chronic pain. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Davis MC, Zautra AJ. An online mindfulness intervention targeting socioemotional regulation in fibromyalgia: Results of randomized controlled trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2013;46(3):273–284. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9513-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MC, Zautra AJ, Wolf LD, Tennen H, Yeung EW. Mindfulness and cognitive-behavioral interventions for chronic pain: Differential effects on daily pain reactivity and stress reactivity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(1):24–35. doi: 10.1037/a0038200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology. 1980;10:85. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccleston C, Crombez G. Pain demands attention: A cognitive-affective model of the interruptive function of pain. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:356–366. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.125.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RR, Klick B, Buenaver L, Max MB, Haythornthwaite JA, Keller RB, Atlas SJ. Symptons of distress as prospective predictors of pain-related sciatica treatment outcomes. Pain. 2007;130(1–2):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar JT, Young J, James P, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94(2):149–158. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor H, Turk DC, Scholz OB. Impact of chronic pain on the spouse: Marital, emotional and physical consequences. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1987;31:63–71. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(87)90099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fordyce WE. Behavioral methods for chronic pain and illness. Saint Louis: The C.V. Mosby Company; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Gurman AS, Lebow JL, Snyder DK. Clinical handbook of couple therapy. 4. New York: Guilford Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hahlweg K, Baucom DH, Grawe-Gerber M, Snyder DK, Christensen A, Snyder DK, … Casey LM. In: Enhancing couples: The shape of couples therapy to come. Hahlweg K, Grawe-Gerber M, Baucom DH, editors. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hanh TN. The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering Into Peace, Joy, and Liberation. New York: Broadway Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Harris R. ACT with Love: Stop Struggling, Reconcile Differences, and Strengthen Your Relationship with Acceptance and Commitment. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1–25. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(02)80041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: The Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman R, Feldbau-Kohn S, Ehrensaft M, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, O'Leary KD. Can questionnaire reports correctly classify relationship distress and partner physical abuse? Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:334–346. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.15.2.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Teasdale JD. Predictors of relapse in unipolar depressives: Expressed emotion, marital distress, and perceived criticism. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1989;98(3):229–235. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.98.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issner JB, Cano A, Leonard MT, Williams AM. How do I empathize with you? Let me count the ways: Relations between facets of pain-related empathy. Journal of Pain. 2012;13(2):167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59(1):12–19. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen A, Cano A. A preliminary investigation of affective interaction in chronic pain couples. Pain. 2007;132:S86–S95. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1982;4:33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Full Catastrophe Living. New York: Bantam Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Rottenberg J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:467–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns RD, Otis JD. Family therapy for persons experiencing pain: Evidence for its effectiveness. Seminars in Pain Medicine. 2003;1(2):79–89. doi: 10.1016/S1537-5897(03)00007-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns RD, Rosenberg R. Pain-relevant responses from sigificant others: Development of a significant-other version of the WHYMPI scales. Pain. 1995;61(2):245–249. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00173-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns RD, Turk DC, Rudy TE. The West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory (WHYMPI) Pain. 1985;23(4):345–356. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LA, Emmons RA. Conflict over emotional expression: psychological and physical correlated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:864–877. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.5.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau J, Barrett LF, Pietromonaco P. Intimacy as an interpersonal process: The importance of self-disclosure, partner disclosure, and perceived partner responsiveness in interpersonal exchanges. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1238–1251. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau JP, Barrett LF, Rovine MJ. The interpersonal process model of intimacy in marriage: a daily-diary and multilevel modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19(2):314. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard MT, Cano A. Pain affects spouses too: Personal experience with pain and catastrophizing as correlates of spouse distress. Pain. 2006;126:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong L, Cano A, Wurm L, Lumley M, Corley A. A perspective taking manipulation leads to greater empathy and less pain during the cold pressor task. The Journal of Pain. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong LEM, Cano A, Johansen AB. Sequential and base rate analysis of emotional validation and invalidation in chronic pain couples: Patient gender matters. Journal of Pain. 2011;12(11):1140–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire LM, Schulz R, Helgeson VS, Small BJ, Saghafi EM. Review and meta-analysis of couple-oriented interventions for chronic illness. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;40(3):325–342. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9216-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken LM, Gauntlett-Gilbert J, Vowles KE. The role of mindfulness in a contextual cognitive-behavioral analysis of chronic pain-related suffering and disability. Pain (03043959) 2007;131(1–2):63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken LM, Vowles KE, Eccleston C. Acceptance of chronic pain: Component analysis and a revised assessment method. Pain. 2004;107(1–2):159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken LM, Yang S. The role of values in contextual cognitive-behavioral approach to chronic pain. Pain. 2006;123:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzack RD. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: Major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277–299. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(75)90044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski C, Zimmer EF, Barrett KM, Dibble SL, Wallhagen M. Differences in patients' and family caregivers' perceptions of the pain experience influence patient and caregiver outcomes. Pain. 1997;72(1–2):217–226. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, Stevens SP, Schnurr PP. Cognitive-Behavioral Couple's Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;24:97–101. doi: 10.1002/jts.20604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley S, Eccleston C, Williams ACdC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain. 1999;80(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas MK, Wilson PH, Goyen J. Comparison of cognitive-behavioral group treatment and an alternative non-psychological treatment for chronic low back pain. Pain. 1992;48(3):339–347. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90082-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öst LG. The efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2014;61:105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]