Abstract

Perfectionism is elevated in individuals with eating disorders and is posited to be a risk factor, maintaining factor, and treatment barrier. However, there has been little literature testing the feasibility and effectiveness of perfectionism interventions in individuals specifically with eating disorders in an open group format. In the current study, we tested the feasibility of (a) a short CBT for perfectionism intervention delivered in an inpatient, partial hospitalization, and outpatient for eating disorders setting (combined N = 28; inpatient n = 15; partial hospital n = 9; outpatient n = 4), as well as (b) a training for disseminating the treatment in these settings (N = 9). Overall, we found that it was feasible to implement a perfectionism group in each treatment setting, with both an open and closed group format. This research adds additional support for the implementation of perfectionism group treatment for eating disorders and provides information on the feasibility of implementing such interventions across multiple settings.

Keywords: Anorexia nervosa, perfectionism, eating disorders, CBT, group therapy

Perfectionism is a risk and maintaining factor for eating disorders (Bardone-Cone, Sturm, Lawson, Robinson, & Smith, 2010; Bulik, Sullivan, & Joyce, 1999; Fairburn, Cooper, & Shafran, 2003; Schmidt & Treasure, 2013) and has consistently been shown to be elevated in individuals with eating disorders in comparison to healthy controls (e.g., Bardone-Cone et al., 2007; Egan, Wade, & Shafran, 2011). Perfectionism has also been implicated as a barrier to positive treatment outcomes, within the eating disorder, anxiety disorder, and depressive disorder literatures (Ashbaugh et al., 2007; Bizeul, Sadowsky, & Rigaud, 2001; Mitchell, Newall, Broeren, & Hudson, 2013; Sutandar-Pinnock, Woodside, Carter, Olmsted, & Kaplan, 2003). Thus, researchers have begun to design interventions explicitly designed to target perfectionism (Handley, Egan, Kane, & Rees, 2015; Pleva & Wade, 2007; Riley, Lee, Cooper, Fairburn, & Shafran, 2007).

Perfectionism interventions have been modified to treat individuals with eating disorders, through two different formats: enhancing CBT for eating disorders (CBT-E) with a perfectionism module (Goldstein, Peters, Thornton, & Touyz, 2014) and using perfectionism as a stand-alone group treatment (Lloyd, Fleming, Schmidt, & Tchanturia, 2014; Tchanturia, Larsson, & Adamson, 2016). Enhanced CBT-E has been tested in a day-hospital setting in patients with anorexia nervosa (AN) (Goldstein et al., 2014) and for individuals with bulimia nervosa (Steele & Wade, 2008). Perfectionism treatment as a stand-alone treatment has been tested as a closed group format in patients with AN in an inpatient setting (Lloyd et al., 2014; Tchanturia et al., 2016). Findings from these trials (CBT enhanced vs. stand-alone perfectionism) have been conflicting, with the CBT enhanced trials finding decreases in perfectionism, but not in comparison to the control group (treatment as usual). Alternatively, Lloyd et al. (2014) and Tchanturia et al. (2016), found that in inpatients with AN, perfectionism was lowered after a 6-week group CBT-for perfectionism intervention (as a stand-alone intervention).

Some researchers have suggested that lack of change in perfectionism groups may be because perfectionism is a non-modifiable personality trait (Chik, Whittal, & O'Neill, 2008; Rice & Aldea, 2006). However, substantial literature shows that perfectionism can be modified (e.g., Ashbaugh et al., 2007; Fairweather-Schmidt & Wade, 2015; Handley et al., 2015; Hewitt et al., 2015; LaSota, Ross, & Kearney, 2017; Lloyd, Schmidt, Khondoker, & Tchantura, 2015; Nehmy & Wade, 2015; Riley et al., 2007; Rozental et al., 2017; Shafran, Lee, Payne, & Fairburn, 2006) and that treatment of perfectionism can decrease anxiety, depression, and disordered eating symptoms (Handley et al., 2015). However, it is important to note that most of this research has been done in an outpatient setting. Given the high occurrence and impact of perfectionism on eating disorders, and the conflicting findings from the current trials, clarifying research is needed to improve perfectionism interventions in the eating disorders.

Perfectionism is a complex construct, and most research so far has focused on testing if the two primary dimensions of perfectionism, high standards and maladaptive perfectionism, decrease over the course of perfectionism treatments (Handley et al., 2015; Tchanturia et al., 2016). High standards is conceptualized as having high expectations for oneself and may or may not be accompanied by self-critical evaluation when those expectations are not met, whereas maladaptive perfectionism is the self-critical evaluation associated with the preoccupation over one's errors and expectations from others (Frost et al., 1997). Maladaptive perfectionism is generally measured as a composite of concern over mistakes, doubts about actions, parental criticism, and parental expectations (Frost et al., 1997). However, concern over mistakes is the aspect of perfectionism most related to eating disorder psychopathology, specifically within AN (Bulik et al., 2003). Therefore, it seems important to examine if concern over mistakes specifically is affected by perfectionism interventions.

Relatedly, the literature discussed above has been conducted across different eating disorder treatment settings. There have been two tests in an inpatient setting and one in a day hospital (Goldstein et al., 2014; Lloyd et al., 2014; Tchanturia et al., 2016). All three of these studies employed a closed group format (e.g., closed to new members after the start of the group), though we know that most treatments in these types of facility are typically open groups (with new members joining as the group progresses) (Bieling, McCabe, & Antony, 2009; Schopler & Galinsky, 2006). Furthermore, the literature showing successful outcomes for CBT perfectionism groups has primarily been in outpatient settings (Ashbaugh et al., 2007; Egan et al., 2014; Handley et al., 2015; Kutlesa & Arthur, 2008; Riley et al., 2007). It seems important to test if both an open group format and an outpatient group are (a) feasible for implementing a perfectionism for eating disorder group treatment, and (b) able to effectively target and decrease perfectionism. Furthermore, it is unknown how often treatment providers in such facilities currently use perfectionism interventions and are willing to be trained in them. We wanted to test if it was feasible to train eating disorder practitioners and if they would be willing to implement such groups. Assessing each of these questions (i.e., open vs. closed group, outpatient perfectionism group, and treatment provider training) will add to the growing literature on the feasibility and effectiveness of perfectionism treatment for eating disorders.

Therefore, in the current study, we tested: (a) an open group in both an inpatient and partial hospital eating disorder treatment setting, (b) a closed group in an outpatient setting, and (c) a training on perfectionism treatment for eating disorder treatment providers. We specifically measured the two major components of perfectionism (high standards and concern over mistakes) to assess if treatments were effective at decreasing one or both of these aspects. We hypothesized that these groups would be feasible to implement, that perfectionism symptoms would decrease across treatment, and that eating disorder treatment providers would learn from a training on perfectionism.

Methods

Inpatient and Partial Hospital Methods

Participants

Participants were current inpatients or partial hospital patients at two different eating disorder treatment facilities. All participants were recruited as part of regular programming in place of other programming. Participants were required to attend when available. There were no exclusion criteria. Participants in both the inpatient and partial hospitalization group were collected across the span of four months. Average group size ranged from 5-10 participants per group. Participants were in group as part of larger treatment at an eating disorder center. Other treatments the participants were in concurrently were: dialectical behavior therapy groups, support groups, meal therapy, and individual therapy. Participants ended the group when their treatment at each of these clinics ended. All procedures were approved by the University of North Carolina or Washington University Institutional Review Board.

Treatment Methods

Treatment was a 7-module treatment on perfectionism that introduced the concept of perfectionism, identified areas in which participants were perfectionistic, challenged perfectionistic thoughts, and created and implemented a perfectionistic exposure hierarchy. Materials were created from existing CBT-for-perfectionism protocols (Shafran, Egan, & Wade, 2010) and adapted for use in an inpatient and partial hospital eating disorder treatment setting using an open group format. Material on exposure therapy and development of an exposure hierarchy was added. Specifically, we added materials directing on the creation of an exposure hierarchy related to perfectionism, as well as materials for implementing the exposures from the hierarchy. Materials and adaptations are available at request from the first author. Due to the open nature of the group, we used any individual who attended more than one group (i.e., 2-7 groups) and used their first and last score on the perfectionism measure as their outcomes.

Measure

Perfectionism scale

We used the high standards and concern over mistakes subscales from the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (Frost, Marten, Lahart, & Rosenblate, 1990), a self-report measure of different dimensions of perfectionism. The high standards subscale is comprised of seven items and assesses high expectations for oneself, as well as critical evaluation of oneself when not living up to those standards. Example items include: I am likely to end up a second rate person, If I do not set the highest standards for myself, and I set higher goals for myself than most people. The concern over mistakes subscale is comprised of nine items and assesses preoccupation over making errors and the belief that any error constitutes complete failure. Example items include: People will probably think less of me if I make a mistake and If I fail partly, it is as bad as being a complete failure. Both the high standards and concern over mistakes subscales have evidenced good convergent and divergent validity as well as good internal consistency (Frost et al., 1990). Participants were asked to report on the FMPS since their last treatment session. In other words, participants were asked to report how perfectionistic they currently felt. Cronbach's alpha for this scale was good (αs = .83-.89)

Outpatient Closed Group Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from an outpatient practice focusing on eating disorder treatment. Participants were participating in therapy with an eating disorder specialist at two different outpatient locations. Participants continued to engage in individual outpatient therapy sessions through the duration of this group.

Treatment Methods

Treatment was again based on the 7-module treatment on perfectionism. However, treatment sessions were tailored to spend more sessions on challenging thoughts and developing and implementing the exposure hierarchy. Participants completed a total of 13 sessions.

Measures

The FMPS as described above was used to evaluate progress. In addition, we used the following measures:

The Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI; (Garner, Olmstead, & Polivy, 1983)is a self-report questionnaire that assesses eating disorder behaviors and attitudes and is comprised of 91 items. In the current study, the Body Dissatisfaction, Bulimia Symptoms, and Drive for Thinness subscales were utilized. Example items from each of these subscales include: I think my hips are too big, I eat when I am upset, and I am terrified of gaining weight, respectively. The EDI-2 has evidenced good internal consistency and good convergent and divergent validity (Garner et al., 1983).

The Obsessive Compulsive Inventory (OCI; Foa et al., 2002) is a self-report measure that assesses obsessive compulsive symptoms related to six subscales (Hoarding, Checking, Neutralizing, Obsessing, Ordering, and Washing) and is comprised of 18 items. Example items include: I check things more often than necessary and I find it difficult to control my own thoughts. The OCI has evidenced good convergent validity and internal consistency.

The Social Appearance Anxiety Scale (SAAS; Hart et al., 2008) is a 16 item self-report questionnaire that assesses fears related to being negatively judged and rejected based on one's appearance. Example items include: I worry people will judge the way I look negatively and I am concerned people would not like me because of the way I look. The SAAS has evidenced high test-retest reliability and good internal consistency.

The Fear of Food Measure (FOFM; Levinson & Byrne, 2015) is a self-report questionnaire that assesses fear of food through three subscales (anxiety about eating, feared concerns related to eating, and food avoidance behaviors) and is comprised of 25 items. Example items from each subscale include: I feel tense when I am around food, I don't like to eat in social situations, and I have rules about what I eat, respectively. The FOFM has evidenced excellent test-retest reliability and good convergent and divergent validity.

Perfectionism Training

Participants

Participants were therapists and dieticians at an eating disorder treatment facility who were invited to participate in a 1-hour training session on perfectionism treatment for eating disorders.

Methods

Participants completed a 1-hour training in perfectionism treatment. Participants learned about perfectionism, how it relates to eating disorders, and what interventions can be implemented in eating disorder populations. Participants were asked about their training experience before and after the training, and then again at one year follow up.

Measures

We created a measure asking participating clinicians about their experience with the training. We also asked clinicians pre-and post training how well the understood the definition of perfectionism and how familiar they were with perfectionism interventions. Table 2 and Table 3 show the items on this measure.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for clinician rating items pre- and post-training on how to implement a perfectionism group for eating disorders.

| Item | N | Range | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The perfectionism training added to my understanding of perfectionism. | 9 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 7.00 | 5.33 | 1.50 |

| Treating perfectionism is relevant in an eating disorder population. | 9 | 0.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 0.00 |

| I feel like I could implement a perfectionism intervention with my patients. | 9 | 2.00 | 5.00 | 7.00 | 6.11 | 0.78 |

| I am likely to implement interventions that target perfectionism with my patients. | 9 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 7.00 | 5.89 | 1.27 |

| I am more likely to work on perfectionism with my patients after receiving the training on perfectionism. | 9 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 7.00 | 6.00 | 1.22 |

| I think the treatment of perfectionism is important for patients with eating disorders. | 9 | 1.00 | 6.00 | 7.00 | 6.89 | 0.33 |

| Perfectionism gets in the way of treatment success for my patients with eating disorders. | 9 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 5.22 | 1.86 |

Notes: SD = standard deviation

Table 3. Descriptive statistics at one year follow up for clinician training in perfectionism group for eating disorders.

| Item | N | Range | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the last year I have treated eating disorder patients. | 4 | 0.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 0.00 |

| In the last year I have implemented perfectionism interventions to treat my eating disorder patients. | 4 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 6.00 | 5.00 | 0.82 |

| In the last year I used what I learned about perfectionism from the perfectionism training. | 4 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 6.00 | 5.25 | 0.96 |

| I think the treatment of perfectionism is important for patients with eating disorders. | 4 | 1.00 | 6.00 | 7.00 | 6.75 | 0.50 |

| Perfectionism gets in the way of treatment success for my patients with eating disorders. | 4 | 2.00 | 5.00 | 7.00 | 6.25 | 0.96 |

Notes: SD = standard deviation

Results

Inpatient and Partial Hospital Open Group

Participant characteristics

Participants in two settings across two eating disorder treatment facilities participated in an inpatient and partial hospital open group (Inpatient n = 15; partial hospital n = 9). Average age was 26.80 (SD = 12.61; Range = 12 to 62). Most participants were European American (n = 20). Diagnoses were as follows: AN (n = 21; 87.5%) and other specified feeding and eating disorder (n = 3; 12.5%). Average body mass index at inpatient pre-treatment was 14.81 kg/m2 (SD = 1.72; Range = 10.85 to 17.14).

Intervention

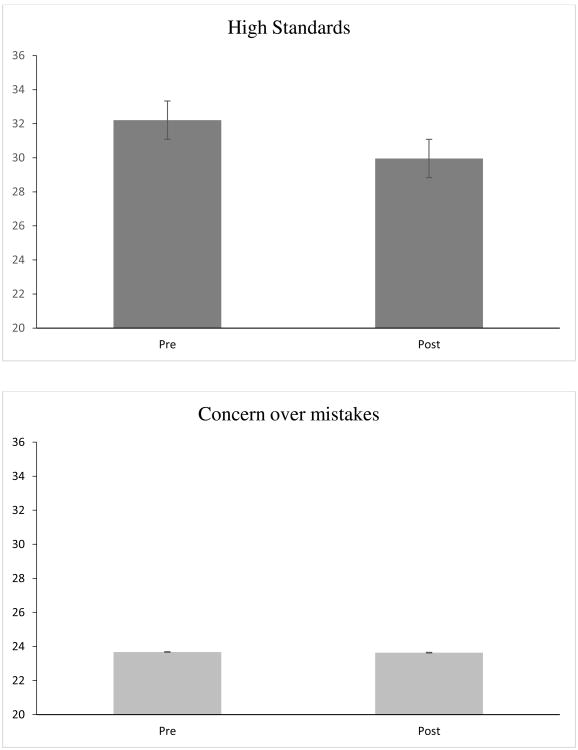

The average number of sessions attended was 3.44 (SD = 1.41; Range = 2 to 7). As shown in Figure 1, there was a significant reduction in high standards from pre-intervention (M = 32.21; SD = 7.75) to post-intervention (M = 29.96; SD = 9.16); t(23) = 2.30, p = .031. However, concern over mistakes was not significantly lower from pre-intervention (M = 23.67; SD= 7.64) to post-intervention (M = 23.63; SD = 7.22); t(23) = .042, p = .967.

Figure 1.

High Standards and Concern Over Mistakes from Pre to Post Treatment in Inpatient and Partial Hospitalization Open Group. Error bars = Standard Error +/-1.

Outpatient Closed Group

Participant Characteristics

Participants diagnoses were as follows: AN (n = 1; 25%) and other specified feeding and eating disorder (n = 3; 75%). Average age was 49.25 (SD = 7.97; Range = 39-58)years old and all participants were European American. One participant attended all 13 sessions, 2 participants attended all but 3, and 1 participant attended all but 1.

Intervention

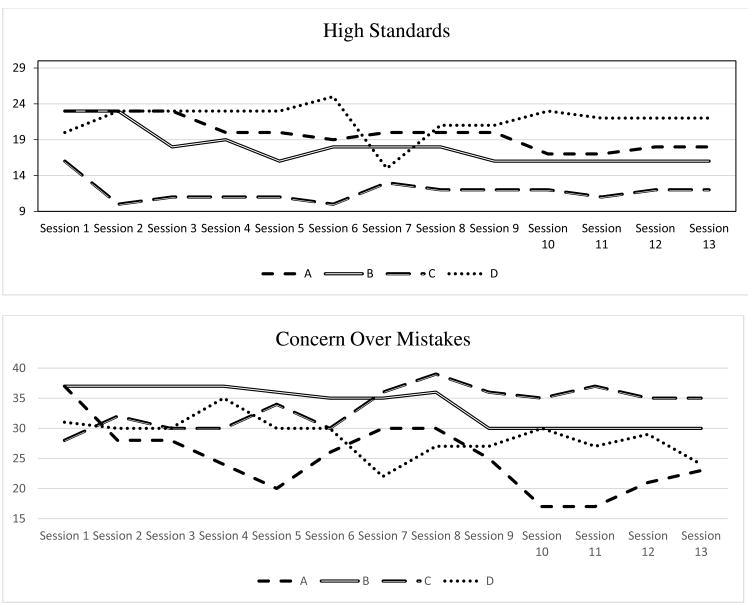

As can be seen in Table 2, concern over mistakes and high standards were lower at post-group than at pre-group therapy, though our sample was too small to test for statistical differences. Scores on drive for thinness were lower, as were scores on measures of fears of food, social anxiety, and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) symptoms. Please see Figure 2 for a breakdown of each of the four participants' scores across the 13 sessions.

Figure 2.

Concern over mistakes and high standards scores of four group participants in closed outpatient group for eating disorders. A, B, C, and D correspond to one participant each.

Perfectionism Training for Eating Disorder Clinicians and Dieticians

The following eating disorder professions were reported at a one-hour training on CBT for perfectionism for eating disorders (therapists n = 7; dieticians n = 2). As can be seen in Table 2, eating disorder professionals reported that after the training, they were more likely to understand the definition of perfectionism (Before training Mean = 4.89; SD = 1.61) (After training Mean = 6.56; SD = 6.56); t(8) = -3.54, p = .008). Eating disorder professionals reported that after the training, they were more familiar with interventions focused on perfectionism (Before training Mean = 4.11; SD = 1.62) (After training Mean = 6.22; SD = .67); t(8) = -4.64, p = .002). Please see Table 3 outlining one year outcomes for four of these eating disorder professionals.

Discussion

We found that a perfectionism group treatment was feasible to implement in an open group format in an inpatient and partial hospitalization eating disorder treatment facility. Furthermore, we found that high standards decreased across the intervention, whereas concern over mistakes did not. Though we should note that our primary aim of the study was to test feasibility, it is promising that we found a decrease in high standards. We also found that an outpatient closed group was feasible to implement. Scores on high standards were lower at the end of outpatient treatment, though the sample size was too small to test for statistical differences. Finally, we found that eating disorder treatment providers were open to a training on perfectionism treatments and were more likely to understand perfectionism and use perfectionism interventions in their work after a training, albeit this was a small sample of providers.

Overall, this research adds to the growing literature suggesting that stand-alone perfectionism interventions may be a viable treatment for eating disorders (Goldstein et al., 2014; Lloyd et al., 2014; Tchanturia et al., 2016). Our research builds on these findings by suggesting that an open group format, as well as a closed outpatient group, is feasible and effective for the treatment of perfectionism in the eating disorders. However, we should note that only high standards decreased across the intervention, suggesting that more attention should be given to implementing perfectionism interventions focused on concern over mistakes. Given that concerns over mistakes has been found to be the aspect of perfectionism most related to eating disorders, this finding seems especially noteworthy (Bulik et al., 2003). Previous research has found a decrease in concern over mistakes (e.g., Lloyd et al., 2014; Tchanturia et al., 2016). Therefore, future research should test what active ingredients of therapy decrease concern over mistakes. Additional interventions could focus on purposively making mistakes or on challenging thoughts related to concerns about making mistakes. For example, clients could do exposures such as purposively dropping food items in grocery stores and then challenge thoughts that occur during the exposure. Most of the specific interventions for perfectionism discuss high standards (e.g., Shafran et al., 2010) and do not explicitly define or focus on exposures to concern over mistakes. Thus, it seems logical that these approaches would be more likely to target high standards rather than concern over mistakes.

Limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. First and foremost, we had a very small sample size and no control group. However, given that the purpose of pilot studies is to field-test logistical aspects of the study in preparation for a randomized control trial (Kistin & Silverstein, 2015), we feel that the tests presented here accomplished this goal. Accordingly, any findings related to effectiveness of the intervention should be interpreted with caution, given both the small sample sizes and nature of the pilot study. Our main priority was to demonstrate the feasibility of these types of groups. Additional limitations of this research include a relatively non-diverse sample and the lack of usage of a structured clinical interview for diagnosis. However, given that all participants who participated in the treatment were currently in a treatment center for an eating disorder (or were recently discharged, as in the outpatient group), we feel confident that these participants met criteria for an eating disorder. Additionally, given that our goal is to implement perfectionism treatments in such treatment settings, we are confident in the appropriateness of the samples. Finally, we did not collect qualitative data on the acceptability of the group from the participants' perspective; we hope that future research will explore how participants perceive participation in similar groups, perhaps through focus groups. Future research should also focus on number of sessions attended. It seems likely that attendance at more groups (e.g., in an open group format) would relate to better outcomes. However, given our small sample size we were unable to test this hypothesis in the current study.

In conclusion, we found that an open group perfectionism treatment was feasible and effective in an inpatient and partial hospitalization setting and that a closed group was feasible in an outpatient setting. Future extensions of this research are needed to test if similar interventions are effective in comparison to treatment as usual, if there are long term benefits from perfectionism treatments, and if treatments can be developed to specifically target concerns over mistakes. We hope that future research will clarify answers to these questions to develop an empirically-supported perfectionism treatment specifically for eating disorder patients in all levels of care.

Table 1. Outcomes from Outpatient Closed Group.

| Time 1 Mean | Time 2 Mean | Time 1 SD | Time 1 SD | t-statistic | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concern Over Mistakes | 38.25 | 30.00 | 8.73 | 7.12 | 1.17 | 0.327 |

| Personal Standards | 28.75 | 21.50 | 4.19 | 5.92 | 2.70 | 0.074 |

| Drive for Thinness | 25.67 | 22.33 | 9.50 | 9.02 | 10.00 | 0.010 |

| Bulimic Symptoms | 25.33 | 19.33 | 7.51 | 4.62 | 1.59 | 0.254 |

| Binge Eating | 19.67 | 14.67 | 5.51 | 3.21 | 2.17 | 0.163 |

| Body Dissatisfaction | 13.67 | 8.67 | 9.24 | 10.02 | 1.57 | 0.260 |

| OCD Symptoms | 27.33 | 17.67 | 23.80 | 18.90 | 2.86 | 0.104 |

| Feared Concerns | 35.67 | 38.67 | 15.28 | 13.80 | -1.96 | 0.188 |

| Social Appearance Anxiety | 47.67 | 47.00 | 7.09 | 6.56 | 0.56 | 0.635 |

Notes: OCD = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder SD = standard deviation; We have included t and p-values for completion though our sample size is only 4 and therefore differences between time points should be interpreted with caution.

References

- Ashbaugh A, Antony MM, Liss A, Summerfeldt LJ, McCabe RE, Swinson RP. Changes in perfectionism following cognitive-behavioral treatment for social phobia. Depression and Anxiety. 2007;24:169–177. doi: 10.1002/da.20219. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardone-Cone AM, Sturm K, Lawson MA, Robinson DP, Smith R. Perfectionism across stages of recovery from eating disorders. The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;43:139–48. doi: 10.1002/eat.20674. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardone-Cone AM, Wonderlich SA, Frost RO, Bulik CM, Mitchell JE, Uppala S, Simonich H. Perfectionism and eating disorders: Current status and future directions. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:384–405. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.12.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieling PJ, McCabe RE, Antony MM. Guilford Press; 2009. Cognitive-behavioral therapy in groups. Retrieved from https://www.guilford.com/books/Cognitive-Behavioral-Therapy-in-Groups/Bieling-McCabe-Antony/9781606234044. [Google Scholar]

- Bizeul C, Sadowsky N, Rigaud D. The prognostic value of initial EDI scores in anorexia nervosa patients: a prospective follow-up study of 5–10 years. European Psychiatry. 2001;16:232–238. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(01)00570-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(01)00570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Joyce PR. Temperament, character and suicide attempts in anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and major depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1999;100:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10910.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik CM, Tozzi F, Anderson C, Mazzeo SE, Aggen S, Sullivan PF. The Relation Between Eating Disorders and Components of Perfectionism. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:366–368. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.366. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chik HM, Whittal ML, O'Neill ML. Perfectionism and Treatment Outcome in Obsessive-compulsive Disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32:676–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-007-9133-2. [Google Scholar]

- Egan SJ, van Noort E, Chee A, Kane RT, Hoiles KJ, Shafran R, Wade TD. A randomised controlled trial of face to face versus pure online self-help cognitive behavioural treatment for perfectionism. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2014;63:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.09.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan SJ, Wade TD, Shafran R. Perfectionism as a transdiagnostic process: A clinical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41:509–528. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00088-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairweather-Schmidt AK, Wade TD. Piloting a perfectionism intervention for pre-adolescent children. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2015;73 doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.07.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Huppert JD, Leiberg S, Langner R, Kichic R, Hajcak G, Salkovskis PM. The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory: Development and validation of a short version. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:485–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.14.4.485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Marten P, Lahart C, Rosenblate R. The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1990;14:449–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01172967. [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Trepanier KL, Brown EJ, Heimberg RG, Juster HR, Makris GS, Leung AW. Self-Monitoring of Mistakes Among Subjects High and Low in Perfectionistic Concern over Mistakes. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1997;21:209–222. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021884713550. [Google Scholar]

- Garner DM, Olmstead MP, Polivy J. Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1983;2:15–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198321)2:2<15∷AID-EAT2260020203>3.0.CO;2-6. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein M, Peters L, Thornton CE, Touyz SW. The Treatment of Perfectionism within the Eating Disorders: A Pilot Study. European Eating Disorders Review. 2014;22:217–221. doi: 10.1002/erv.2281. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley AK, Egan SJ, Kane RT, Rees CS. A randomised controlled trial of group cognitive behavioural therapy for perfectionism. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2015;68:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.02.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart TA, Flora DB, Palyo SA, Fresco DM, Holle C, Heimberg RG. Development and Examination of the Social Appearance Anxiety Scale. Assessment. 2008;15:48–59. doi: 10.1177/1073191107306673. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107306673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt PL, Mikail SF, Flett GL, Tasca GA, Flynn CA, Deng X, et al. Chen C. Psychodynamic/interpersonal group psychotherapy for perfectionism: Evaluating the effectiveness of a short-term treatment. Psychotherapy. 2015;52:205. doi: 10.1037/pst0000016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistin C, Silverstein M, AD O, C N, L P. Pilot Studies. JAMA. 2015;314:1561. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10962. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.10962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutlesa N, Arthur N. Overcoming Negative Aspects of Perfectionism through Group Treatment. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. 2008;26:134–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-007-0064-3. [Google Scholar]

- LaSota MT, Ross EH, Kearney CA. A Cognitive-Behavioral-Based Workshop Intervention for Maladaptive Perfectionism. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. 2017:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-017-0261-7.

- Levinson CA, Byrne M. The fear of food measure: A novel measure for use in exposure therapy for eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2015;48:271–283. doi: 10.1002/eat.22344. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd S, Fleming C, Schmidt U, Tchanturia K. Targeting Perfectionism in Anorexia Nervosa Using a Group-Based Cognitive Behavioural Approach: A Pilot Study. European Eating Disorders Review. 2014;22:366–372. doi: 10.1002/erv.2313. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd S, Schmidt U, Khondoker M, Tchanturia K. Can psychological interventions reduce perfectionism? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2015;43:705–731. doi: 10.1017/S1352465814000162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JH, Newall C, Broeren S, Hudson JL. The role of perfectionism in cognitive behaviour therapy outcomes for clinically anxious children. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2013;51:547–554. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.05.015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehmy TJ, Wade TD. Reducing the onset of negative affect in adolescents: Evaluation of a perfectionism program in a universal prevention setting. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2015;67:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.02.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleva J, Wade TD. Guided self-help versus pure self-help for perfectionism: A randomised controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:849–861. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.08.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice KG, Aldea MA. State dependence and trait stability of perfectionism: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53(2):205–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.2.205. [Google Scholar]

- Riley C, Lee M, Cooper Z, Fairburn CG, Shafran R. A randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behaviour therapy for clinical perfectionism: A preliminary study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45 doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.12.003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozental A, Shafran R, Wade T, Egan S, Nordgren LB, Carlbring P, et al. Trosell L. A randomized controlled trial of Internet-Based Cognitive Behavior Therapy for perfectionism including an investigation of outcome predictors. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.05.015. online first version. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure J, Schmidt U. The cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model of anorexia nervosa revisited: a summary of the evidence for cognitive, socio-emotional and interpersonal predisposing and perpetuating factors. Journal of Eating Disorders. 2013;1:13. doi: 10.1186/2050-2974-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopler JH, Galinsky MJ. Meeting Practice Needs: Conceptualizing the Open-Ended Group. Social Work With Groups. 2006;28:49–68. https://doi.org/10.1300/J009v28n03_05. [Google Scholar]

- Shafran R, Egan S, Wade T. Overcoming perfectionism : a self-help guide using cognitive behavioral techniques. Robinson; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shafran R, Lee M, Payne E, Fairburn CG. The impact of manipulating personal standards on eating attitudes and behaviour. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44 doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.08.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele AL, Wade TD. A randomised trial investigating guided self-help to reduce perfectionism and its impact on bulimia nervosa: A pilot study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46 doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.09.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutandar-Pinnock K, Blake Woodside D, Carter JC, Olmsted MP, Kaplan AS. Perfectionism in anorexia nervosa: A 6-24-month follow-up study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;33:225–229. doi: 10.1002/eat.10127. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchanturia K, Larsson E, Adamson J. Brief Group Intervention Targeting Perfectionism in Adults with Anorexia Nervosa: Empirically Informed Protocol. European Eating Disorders Review. 2016;24:489–493. doi: 10.1002/erv.2467. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]