Abstract

Computer-based video provides a valuable tool for HIV prevention in hospital emergency departments. However, the type of video content and protocol that will be most effective remain underexplored and the subject of debate. This study employs a new and highly replicable methodology that enables comparisons of multiple video segments, each based on conflicting theories of multimedia learning. Patients in the main treatment areas of a large urban hospital’s emergency department used handheld computers running custom-designed software to view video segments and respond to pre-intervention and postintervention data collection items. The videos examine whether participants learn more depending on the race of the person who appears onscreen and whether positive or negative emotional content better facilitates learning. The results indicate important differences by participant race. African American participants responded better to video segments depicting White people. White participants responded better to positive emotional content.

Although the effectiveness of video-based HIV testing and prevention programs has been clearly established (Carey, Coury-Doniger, Senn, Vanable, & Urban 2008; Gilbert et al., 2008; Merchant et al., 2007, 2009) systematic examinations of how educational video segments can be optimized for greater impact have largely been overlooked. For example, studies generally do not compare multiple video segments to examine how the physical characteristics of people who appear onscreen in a public health message can shape a video’s effectiveness among particular groups of viewers. Nor do studies typically examine how the tone of a public health message can influence learners’ response. As a result, the design of an educational video segment often reflects the experience or intuition of a producer more than the results of empirical research trials.

To better understand how educational video can be made most effective, this study compared four video segments designed to test specific theories of multimedia learning. The videos depicted either a White health care provider speaking to a White patient or an African American health care provider speaking to an African American patient. Additionally, each video was designed to elicit either a positive or negative emotional response. The purpose of this study is not only to evaluate these videos but also to establish a model for quantifying the effectiveness video segments while educating underserved populations in demanding real-world settings, such as the main treatment area of a hospital emergency department (ED).

This research comes at a time of increased calls to offer HIV testing to all patients. Federal guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) call for opt-out screening, in which all patients in all types of health care settings are screened for HIV once the patient is notified that testing will be performed, unless the patient specifically declines an HIV test (Branson et al., 2006). Similarly, as of September 2010, New York State now requires staff to offer an HIV test to all people between the ages of 13 and 64 who are receiving hospital or primary care services, including ED patients (New York State Department of Health, 2010).

Routine HIV testing in hospital ED is recommended by the CDC, because people who visit an may lack access to other forms of health care, and if they are not tested for HIV, they may be infected for years before receiving a diagnosis (Branson et al., 2006). However, providing the limited pretest information needed to meet the CDC’s HIV testing guidelines (Branson et al., 2006) can be especially difficult for staff given the extensive responsibilities they already face, along with the exceptionally challenging environments in which they work (Merchant et al., 2007). Facing budget considerations, health care providers often devote less time to patient education in general because it may not be viewed as cost effective (Roye, Silverman, & Krauss, 2007). Even when adequate education is provided and tests are offered, high-risk patients may decline (Carey et al., 2008).

A well-designed, computer-based learning environment can enable hospital staff to reach wider and less motivated audiences of patients (Kiene & Barta, 2006) without sacrificing quality, interrupting workflow, or neglecting patient rights. A computer-based video learning environment can also help standardize the information provided to patients, as not all facilities have trained HIV counselors available at all times. In addition, handheld computers help maintain patient privacy. Instead of collectively viewing video messages on a large screen in a room full of people, or speaking with an HIV counselor where other patients and visitors might overhear, each patient can view educational videos on a handheld device and respond individually.

Previous studies have successfully used video and computer-based interventions in clinical settings to educate patients about HIV testing and prevention and to reduce risk behaviors. Merchant et al., (2009) used a 9.5 minute video to provide HIV pretest information to patients recruited from the ambulatory care and urgent care areas of a hospital ED and found the video “was an acceptable substitute for an in-person information session” (p. 132). Carey et al., (2008) used a video to promote HIV testing among patients at an STD (sexually transmitted disease) clinic who were at risk for HIV and had declined multiple offers of an HIV test. They found that after watching the video, participants improved in both attitude toward, and knowledge of, HIV testing, although patients who received individualized stage based counseling instead of watching the video accepted an HIV test more frequently. Gilbert et al., (2008) used laptop computers at outpatient HIV clinics to deliver video presentations that were tailored to each participant by gender, risk profile, and readiness to change. Participants who viewed the videos later reported decreases in illicit drug use and unprotected anal or vaginal intercourse.

The methodology employed by this study differs from the above in three important ways. First, this study’s intervention was very short. The videos lasted approximately 2 minutes, and the entire intervention, including data collection, took patients about 10 minutes to complete. The Gilbert et al., (2008) intervention, in contrast, required multiple sessions of roughly 1 hour each and therefore would have been impractical in an ED. Second, this study’s intervention was implemented in the main treatment area of a hospital ED, in contrast to that of Merchant et al.’s (2009), which was implemented in an ED but may not have recruited patients in all parts of the ED, such as the critical care area. Unlike Carey et al., (2008) or Gilbert et al., which brought participants to a private room to deliver the intervention, the video segments used in this study were delivered on a handheld computer where the patient was receiving treatment. In the environment where this study’s data were collected, moving participants to a separate area would have disrupted the ED’s workflow, interfering with patient care. Third, and perhaps most notable, the above studies did not compare multiple video segments to determine the most effective implementation of educational theory. Merchant et al. (2009) and Carey et al. (2008) showed participants a single video and then evaluated the video’s success. Gilbert et al. (2008) targeted specific video segments to individual participants, but all the videos depicted the same actor in the role of physician. Unlike this study, the above studies did not create multiple videos depicting health care providers of different ethnic/racial backgrounds or different types of emotional content to compare their effectiveness.

Although Bandura (1986, 1994) wrote about the importance of matching people who appear as educational models to the characteristics of their viewers, both in terms of ethnicity and circumstances, others, such as Durantini, Albarracín, Mitchell, Earl, and Gillette (2006), have noted that, at times, deliberately selecting a nonmatching information source to deliver a message may yield greater results. Likewise, whereas Ashby, Isen, and Turken (1999) described the benefits of eliciting a positive emotional state in learners or problem solvers, Witte and Allen (2000) identified fear as an especially potent motivator among viewers of video-based public health campaigns. Thus, the goal of this study is not to determine whether video can be used to educate people about HIV prevention and testing but rather to examine how the characteristics of the people who appear onscreen in a video, and the emotional content of the message they convey, shape that video’s effectiveness.

RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

The primary goals of this study are as follows.

To develop an intervention and replicable methodology that facilitate increased HIV testing and prevention education while collecting data in a high volume clinical environment. This will be measured by increases in HIV test acceptance, including test acceptance by patients who initially decline an HIV test upon arrival at the hospital. This will also be measured by increases in knowledge of HIV testing and prevention, and self-reported intent to use a condom.

To implement a structured, randomized comparison of four original video segments to determine the most effective combination of onscreen race (African American, White) and emotional content (positive, negative). We expect one video will prove most effective, as measured by HIV test acceptance, increases in knowledge of HIV testing and prevention, and self-reported intent to use a condom.

METHOD AND SAMPLE

A convenience sample of 202 adult patients in two EDs at a high-volume urban hospital center in the Northeast were approached during 22 days of data collection in summer 2008 and asked if they would like to participate. The hospital center serves a broad range of patients from a variety of ethnic backgrounds, literacy levels, and income levels. Participants ranged in age from 18 to over 65. Most participants reported their age as 25 to 34 (27.7%, n = 56) or 35–44 (23.3%, n = 47). Participants identified themselves as Black or African American (36.6%, n = 74), White (29.7, n = 60), Latino (24.3%, n = 49), and other (9.4%, n = 19). Almost all participants (90.1%, n = 182) reported that English was the language they spoke at home. The next most frequently reported language was Spanish (5.9%, n = 12).

Approximately 56% (n = 113) of participants were female and 44% (n = 89) male. Approximately 56% (n = 114) reported having sex with men, 40% (n = 81) reported having sex with women, and approximately 4% (n = 7) reported having sex with both. Roughly 65% (n = 132) reported that they planned to have vaginal intercourse within the next 3 months, approximately 15% (n = 30) reported they planned to have anal intercourse in the next 3 months. Only participants who reported intent to have vaginal or anal sex in the next 3 months were asked about their intent to use a condom during vaginal or anal sex, respectively.

At triage, all patients are assigned a category describing their need for care. Patients most in need of care, generally including gunshot victims or other trauma patients in severe distress, are designated emergent. Patients who had been categorized by hospital staff as nonemergent and who were not under 18 years of age, intoxicated, or in too much pain were eligible to participate.

In January of 2008, the medical center where data were collected began asking patients at triage if they would like an HIV test, at the discretion of the triage nurse—if the ED was especially busy, or if the staff HIV counselor was not present, a triage nurse would be less likely to ask patients they wanted a test. Of the people recruited for this study, 27.2% (55 people) had been asked at triage if they would like a test. Of the 55 participants offered a test at triage, 44 said no.

PROCEDURE

Patients were approached individually and asked if they might like to know more about this study. Those who expressed interest were told about the study in detail and given a consent form explaining the purpose of the research and emphasizing that participation was voluntary. All intervention materials, consent documents, and the study’s protocol were approved by institutional review boards at New York University and the hospital center where data were collected. For each person who agreed to participate, roughly two declined. This study did not keep detailed records of patients who were approached but did not enroll. Only four patients who began the intervention withdrew before responding to all study instruments. Participants were not paid.

The authors recruited most patients and collected most of the data. The hospital center where data were collected maintains a pool of volunteer “academic associates” to assist in research. These are mainly undergraduates or recent college graduates. Two academic associates also recruited participants and collected data for this study.

After providing written consent, patients were handed a small computer running software custom authored for this study. The software integrated preintervention and postintervention data collection instruments with videos developed to examine how the race of the people who appear onscreen and the emotional content of an educational video segment impact its effectiveness. The software randomly selected a treatment group for each patient. The resulting study design was 2 (emotional content: positive, negative) X 2 (onscreen race: African American, White). Each participant saw one educational video segment and all patients were asked to complete the same set of preintervention and postintervention instruments.

At the end of the intervention, the software asked all patients if they would like an HIV test: using the computer, participants could answer yes or no. Responses were transmitted wirelessly to an off-site password protected database. Participation was entirely anonymous, no identifying information was collected, and no HIV test results were recorded or delivered to patients as part of this study. All HIV testing was performed by hospital staff, independent of this study.

After patients entered brief demographic data, such as age and race, the software presented a set of preintervention questions designed to measure: knowledge of HIV testing and prevention; intent to use a condom during anal or vaginal sex. The preintervention and postintervention data collection instruments each used a five unit Likert-scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” for the knowledge test and “highly unlikely” to “highly likely” for the other measures.

Once the patient responded to the preintervention items, the computer displayed an educational video segment in which a health care provider discussed the importance of HIV testing, performed a rapid oral test, and delivered the results. Depending on the video, the onscreen interventionists either spoke about the importance of HIV testing and prevention in positive terms, reassuring and pleasantly encouraging the viewer, or in negative terms, which may have frightened viewers. Additionally, some patients saw a video in which the onscreen health care provider and patient were White, while others saw a video in which both the health care provider and the patient were African American.

Immediately following the video, the computer displayed a set of postintervention measures. These measures were the same as the preintervention items, but worded differently. After completing the postintervention items, the computer prompted patients to indicate if they would like an HIV test. Once patients entered a response to this finial prompt on the computer their participation in the study was completed.

All measures were developed specifically for this study and were reviewed by Perry N. Halkitis, associate dean for doctoral research at New York University’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development and an accomplished researcher in HIV prevention. The dialogue in the video segments was then developed to cover the material addressed in the knowledge tests. The people who appear as health care providers are in fact health care providers. Actual health care professionals were used rather than actors to avoid characterizations that could be false, or even stereotypical, and to ensure everyone involved in the videos’ creation was highly knowledgeable about the subject matter. Actual patients do not appear in the videos for privacy reasons.

ANALYSIS

This study’s instruments included seven preintervention and post intervention Likert-scale measures: five knowledge test items, and two items measuring intent to use a condom during vaginal and anal sex, respectively. Participant responses to these Likert-scale measures were analyzed using a series of repeated measures ANOVAs (analyses of variance), with separate ANOVAs for each item. The instruments also included one dichotomous measure: At the end of the intervention the computer asked participants if they would like an HIV test; possible responses were yes or no. Participant responses to this dichotomous measure were examined using a chi-square analysis.

All analyses were initially conducted using the entire sample, to determine if one treatment would emerge as most effective overall. Subsequent analyses were then conducted separately by population group (Black or African American, Latino, White) to examine possible differences in response to the same set of treatments.

RESULTS

Of the 202 people who completed this study’s intervention, a total of 86 (42.6 %) accepted an HIV test at the end. This acceptance rate includes 62 patients who had not been offered an HIV test upon arrival at the hospital but who agreed to a test after watching one of the video segments. The acceptance rate also includes patients who declined an HIV test and later accepted one after viewing a video developed as part of this study: 13 (29.5 %) of the 44 participants who initially declined an HIV test offered at triage accepted a test at the end of our intervention.

INCREASED TEST ACCEPTANCE

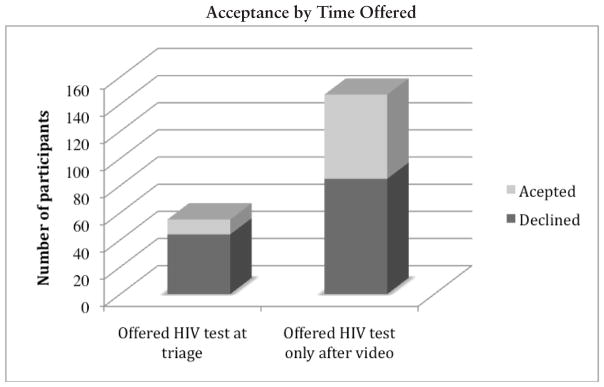

A chi-square analysis comparing the initial acceptance rate of the 55 participants who were offered an HIV test at triage with the acceptance rate of the 147 participants who were only offered an HIV test after watching a video segment indicates a highly significant relationship between watching a video produced for this study and accepting an HIV test, χ2(1, 202) = 8.53, p < .01. Although 20% of participants accepted a test offered at triage, 42.2% of the patients not offered a test at triage accepted an HIV test when it was offered after they watched a video.

INCREASES IN KNOWLEDGE AND CONDOM INTENT

When the Likert-scale responses of all participants are examined together, the data indicate an overall increase in knowledge of HIV transmission and prevention as well as condom intent among participants who viewed the educational video segments produced for this study. Statistically significant increases were noted on all knowledge test questions but one. Significant increases were also noted with regard to condom usage intent during vaginal sex.

When the responses of all 202 participants were examined as a single large group, repeated measures ANOVAs did not reveal one treatment that was significantly more effective than the other three in terms of scores on a pre-post intervention knowledge test or changes in self-reported condom intent. Similarly, when the responses of all 202 participants were examined together there were no statistically significant differences in the decision to accept an HIV test, by treatment, as detailed in a chi-square analysis.

However, when participant responses are examined separately by race (Black or African American, Latino, White), the data indicate potentially important between-group differences in learner reaction to the video segments. Black or African American participants who viewed White people onscreen showed higher increases than Black or African American participants who viewed African Americans onscreen in all knowledge test questions, other than a question about male and female condoms protecting a person from HIV. When identical repeated measures ANOVAs were separately conducted on the responses of White participants and on Latino participants, a similar pattern of Time x Onscreen Race interactions did not emerge. In fact, even when statistically significant main effects were detected for time, no significant Time x Onscreen race interactions were detected for Latino participants, and only one significant Time x Onscreen race interaction was detected for White participants.

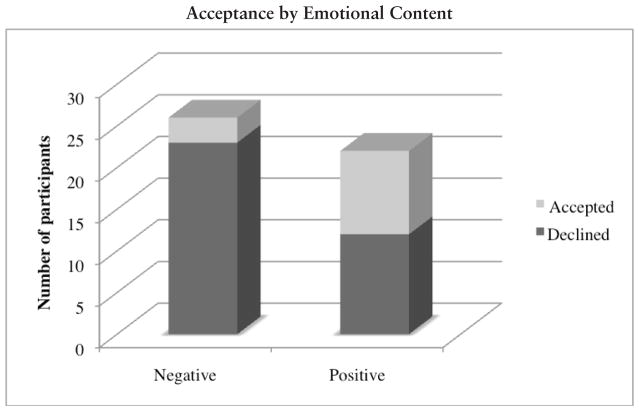

Instead, emotional content played a clear role for White people. Among patients not offered an HIV test at triage, White participants who viewed negative emotional content rarely accepted an HIV test, whereas almost half the White participants who watched positive emotional content accepted an HIV test at the end of the intervention. Emotional content did not appear to be a factor for Black or African American participants. Neither race nor emotional content produced a pattern of significant results among Latino participants. The results are described in greater detail as follows.

ONSCREEN RACE

In both the condom intent measures and all knowledge test measures except one, the mean increase in scores by African American participants who watched White people onscreen was higher than the mean increase in scores by Black or African American participants who watched African Americans onscreen. Although the difference between the two groups was not always statistically significant (this lack of significance may be due, at least in part, to the wide variance of scores as well as the small size of each subgroup), a notable pattern begins to emerge. A series of repeated measures ANOVAs with onscreen race (African American, White) as the between-subjects factors and time as the within-subjects factor indicate statistically significant increases in knowledge and self-reported condom intent following the video segments, and significant Time X Treatment interactions as follows.

A repeated measures ANOVA with onscreen race (African American, White) as the between-subjects factors and time as the within-subjects factor indicates a statistically significant difference in the degree to which Black or African American participants who watched African Americans onscreen and African Americans who watched White people onscreen changed their answers to disagree that people are automatically tested for HIV anytime a doctor administers a blood test, F(1,72) = 4.94, p < .05, partial η2 = .06. Black or African American participants who viewed a video depicting White people moved closer to the “strongly disagree” end of the scale, which is the correct answer, than did Black or African American participants who viewed African Americans onscreen.

A separate repeated measures ANOVA with onscreen race (African American, White) as the between subjects factors and time as the within-subjects factor indicates a statistically significant difference in the degree to which Black or African American participants who watched African Americans onscreen and Black or African Americans who watched White people onscreen changed their answers to disagree that a negative test result would mean they are not infected with HIV F(1, 72) = 8.70, p. < .01, partial η2 = .108. Again, Black or African American participants who viewed a video segment depicting White people moved closer to the “strongly disagree” end of the scale, which is the correct answer, than did Black or African Americans who viewed a video segment depicting African Americans.

An additional repeated measures ANOVA with onscreen race (African American, White) as the between subjects factor and time as the within-subjects factor indicates a statistically significant difference in the degree to which Black or African American participants who watched African Americans and Black or African Americans who watched White people reported an increased intent to use condoms during vaginal sex, F(1, 47) = 4.61, p < .05, partial η2 = .089. Black or African American participants who watched White people onscreen reported a greater increase in intent to use condoms during vaginal sex than did Black or African American participants who watched African Americans onscreen. In fact, those who watched African Americans indicated almost no increase at all.

EMOTIONAL CONTENT

A chi-square analysis of White participants not offered a test at triage indicates a highly significant relationship between emotional content and decision to test, χ2 (1, 48) = 6.94, p < .01. Only 3 (11.5 %) of the 26 White participants who were not offered a test at triage and viewed negative emotional content accepted an HIV test at the end of the intervention. In contrast, almost half (45.5 %, n = 10) of the White participants who were not offered a test at triage and viewed positive content said yes after watching a video.

A chi-square analysis of the 34 Latino participants who were not offered a test at triage did not show a statistically significant relationship between emotion and a participant’s decision to test, nor did a chi-square analysis of the 52 African American participants who were not offered an HIV test at triage.

ACCEPTANCE OF AN HIV TEST AFTER INITIAL REJECTION

The emotional content of the video segments appears to be a determining factor for the 44 participants who were offered an HIV test at triage and said no. Of the 44 who initially declined, 13 later accepted a test offered at the end of the intervention. Among those who rejected a test at triage, a proportionally greater number (40%, n = 8) said yes to a test at the end of the intervention after watching negatively themed emotional content. Although the difference is not statistically significant, among those who rejected a test at triage and watched positively themed emotional content, only 20.8% (n = 5) accepted a test at the end of the intervention. The race of the person in a video did not appear to be a determining factor among those who said no to a test at triage.

DISCUSSION

The methodology and intervention developed for this study enabled ED staff to effectively educate an increased number of patients about HIV prevention and testing while collecting data in the main treatment area of a high-volume urban hospital ED. Significantly more participants accepted an HIV test after watching one of the videos developed for this study than accepted a test at triage. Furthermore, approximately 30% of participants who initially declined an HIV test accepted one at the end of the intervention. In addition, a structured comparison of multiple educational video segments indicates differences in effectiveness by treatment and participant characteristics.

Although an initial expectation of this study, based on a review of relevant literature, was that one video would emerge as most effective overall, this is not the case. Instead, between-group differences emerged by participant race and readiness to test. This may indicate that instead of the standard practice of delivering a single educational video to all learners, or even to particular groups of learners, future interventions can be fine-tuned for greater effectiveness by tailoring content to learners’ demographics and other characteristics, such as patients’ readiness to test.

The results also indicate the effectiveness of this study’s methodology. We did not recruit participants based on HIV risk factors but instead offered an intervention to a broad range of patients. As a result, this study offered HIV testing and prevention education to 147 participants who had not been offered an HIV test upon arrival at the hospital. If not for this study, these patients more than likely would not have been offered an HIV test or equivalent education before leaving the ED.

A brief intervention that reaches more people may have a greater public health impact than a “traditional high-contact, low-reach intervention” (Kiene & Barta, 2006, p. 404). Therefore, the data collected for this study are especially encouraging. After a 10-minute intervention participants displayed significant increases in knowledge and condom intent; and more than 40% accepted an HIV test. These findings validate our decision to create a brief intervention and offer it to as many patients as possible.

The fact that we have data to analyze and discuss may in itself offer additional evidence of success. We implemented this study in the main treatment area of an exceptionally high-volume ED. Had this study interfered with patient care, it almost certainly would have been halted by hospital staff. Instead, handheld computers enabled us to work unobtrusively with patients in their hospital beds. Mobile broadband connections enabled us to easily transmit patient responses to an off-site, password-protected database. A primary goal of this study was to create a replicable model to provide HIV testing and prevention education to an increased number of people while collecting data in clinical environment. The data indicate we were successful.

Perhaps most important, approximately 30% of participants who had initially declined an HIV test accepted one at the end of this intervention. This finding indicates that a 10-minute protocol can motivate patients to reconsider a decision not to learn their HIV status. Because people who decline an HIV test may falsely believe they are not at risk of HIV, or may fear a positive test result, interventions that can improve test acceptance among these patients are a public health priority (Carey et al., 2008).

As mentioned earlier, Black or African American participants in this study attended more to messages of HIV testing and prevention when the messages were delivered by a White onscreen model than by an African American onscreen model. These findings appear to support the importance Bandura (1986, 1994) attributed to the physical characteristics of models in vicarious learning environments. However, although Bandura has recommended consistently matching the characteristics of the model to those of the learner, this study’s data suggest there may be circumstances when nonmatching onscreen models result in greater effectiveness among particular groups.

Durantini et al., (2006) noted that groups that have traditionally lacked power—for example, ethnic minorities—may be more sensitive to an interventionist’s physical characteristics. If so, this might explain why African American participants responded differently than White participants. This still would not explain why on-screen race did not appear to influence Latino participants. It is possible that an additional set of video segments depicting a Latino health care provider and patient could have produced different results. It is also possible the lack of significant results is simply due to the smaller number of Latino participants.

Other theories may also be used to interpret differences in response by participant race. For example, stereotype threat might help explain participants’ responses: Awareness of negative stereotypes (Aronson, Fried, & Good, 2002) or situational pressures related to stigmas of intellectual inferiority (Aronson et al., 1999) may explain why Black or African American participants showed greater increases on a knowledge test after viewing a White person onscreen, but again would not explain the response of Latino participants. Ultimately, however, our data do not enable us to draw these types of conclusions, because we did not ask participants why they made their choices. The purpose of the study was not to explain between-group differences by race but instead to examine participant response to multiple video segments. The finding that African American, Latino, and White participants responded differently is in itself important to creating more effective video segments and warrants further research.

As described earlier, White participants who were not offered a test at triage and viewed negative emotional content rejected an HIV test at the end of the intervention almost 90% of the time. In contrast, almost half the participants in this subgroup accepted an HIV test after viewing positive emotional content. This does not, however, indicate that positive emotional content would be most effective in all circumstances. A proportionally greater number of participants who initially declined an HIV test later accepted one after viewing negative emotional content. Although the difference in acceptance rates by emotion among those who declined a test at triage was not statistically significant, it may suggest a more nuanced approach to emotional design. Long-established theories hold that states of positive affect facilitate learning better than negative affect (Ashby et al., 1999; Astleitner, 2000, 2005; Bandura, 1986, 1994). Data from this study may indicate that different types of emotional content are better suited to particular learners in different circumstances. Similarly, these data appear to support Biener et al., (2000) who note the effective use of fear-based messages to promote seat belt use, combat drunken driving, or achieve other public health-related goals. The data also appear to support Witte and Allen (2000), who wrote that fear-based media appeals aimed at behavior change become effective when the message offers a practical way of responding to a threat, such as accepting an HIV test rather than rejecting one.

LIMITATIONS

As is the case for any research, this study has some shortcomings that limit the generalizability of its findings. To limit the number of video segments shown to participants, thereby reducing the number of independent variables, this study intentionally did not attempt to address all possible factors. This study employed a 2 × 2 design, using a total of four video segments and four treatment groups, but could have easily required as many as 16 or 32. Additionally, because two videos depict a White health care professional and a White patient, and the others depict an African American health care professional and an African American patient, we cannot determine if participants are responding to the race of the interventionist, the patient, or both.

This study was designed to determine the most effective of four video segments. It was not originally designed to examine differences in response by participant race. Although the sample size was large enough to draw conclusions and produce notable effect sizes, a larger sample size may have enabled the use of more sophisticated statistical techniques to more closely examine differences by participant race or other characteristics. It is possible that the smaller sample size resulting in a lack of power made it more challenging to detect a significant interaction. Future studies can be designed to better detect and analyze the differences.

Intervention materials were only available in English. As a result, people who did not speak English were excluded from the study, which may have particularly influenced data collected from Latino participants.

Participation in the study was anonymous, and as a result, there was no reliable way to determine if a person who accepted a test at the end of the intervention ultimately received a test. There were at times delays between the point when a study participant accepted the offer of a test and the time a hospital staff member became available to administer one. If the delay was lengthy, there was no way to note which of the patients who accepted a test had actually received one, without compromising participants’ anonymity. We determined that protecting participant anonymity was a greater priority and that we could do so without diminishing the value of this study.

CONCLUSION

Using handheld computers and mobile broadband connections enabled streamlined patient education and data collection in an exceptionally high-volume urban ED environment. Randomizing participants into different groups, and showing each group a different video designed to test specific learning theories, enabled us to identify differences in the videos’ effectiveness by population. Had we followed the generally accepted practice of showing a single video to all participants, we most likely would have missed these important between-group differences. Similarly, if we had drawn participants from a less diverse sample, we might not have found that different population groups can respond so differently to the same set of video segments viewed in the same environment. Future studies can further this line of research by replicating our methodology in additional real-world clinical settings, especially where patient education and research may have previously been deemed impractical. The results will not only lead to stronger computer-based video interventions but to better service for people who might otherwise be missed.

FIGURE 1.

Acceptance rates by when an HIV test was first offered: at triage or after watching a video segment (N = 202). While only 20 percent (n = 11) of those offered a test at triage said yes, 42.2 percent (n = 62) who were not offered a test at triage accepted one after watching a video segment.

FIGURE 2.

Acceptance rates by emotion, White participants not offered a test at triage (n = 48). Only three (11.5 %) of the 26 White participants not offered a test at triage and shown negative content accepted a test afterward. Meanwhile, almost half (45.5 %, n = 10) of White participants not offered a test at triage and shown positive content said yes at the end of the intervention.

Table I.

Mean Increases In Knowledge, Condom Intent

| African American Participants | White Participants | Latino Participants | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Mean Change | n | Pre | Post | Mean Change | n | Pre | Post | Mean Change | n | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Item | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Any type of condom (male or female) will protect you from HIV | White video | 3.00 | 1.68 | 3.87 | 1.47 | 0.87** | 38 | 2.25 | 1.16 | 4.19 | 1.15 | 1.94** | 32 | 3.69 | 1.39 | 4.31 | 1.20 | 0.62 | 29 |

| African American video | 3.44 | 1.54 | 4.61 | 0.69 | 1.17** | 36 | 2.89 | 1.64 | 4.04 | 1.32 | 1.15** | 28 | 3.70 | 1.53 | 3.85 | 1.66 | 0.15 | 20 | |

| You are automatically tested for HIV anytime your doctor gives you a blood test | White video | 3.92 | 1.48 | 4.50 | 1.06 | 0.58* | 38 | 4.50 | 0.98 | 4.63 | 1.10 | 0.13 | 32 | 3.48 | 1.50 | 3.55 | 1.64 | 0.07 | 29 |

| African American video | 3.86 | 1.53 | 3.86 | 1.59 | 0.00 | 36 | 4.39 | 1.23 | 4.79 | 0.79 | 0.4* | 28 | 3.65 | 1.63 | 4.10 | 1.55 | 0.45 | 20 | |

| When people first get infected with HIV they feel sick right away | White video | 4.47 | 1.06 | 4.71 | 0.73 | 0.24 | 38 | 4.88 | 0.49 | 4.97 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 32 | 3.86 | 1.41 | 4.21 | 1.35 | 0.35 | 29 |

| African American video | 4.69 | 0.79 | 4.72 | 0.85 | 0.03 | 36 | 4.82 | 0.48 | 4.82 | 0.61 | 0.00 | 28 | 4.65 | 0.67 | 4.80 | 0.52 | 0.15 | 20 | |

| You can tell from looking at someone if they have HIV/AIDS | White video | 4.53 | 1.11 | 4.68 | 0.84 | 0.15 | 38 | 4.81 | 0.59 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 32 | 4.34 | 1.26 | 4.59 | 0.98 | 0.25 | 29 |

| African American video | 4.83 | 0.61 | 4.78 | 0.80 | −0.05 | 36 | 4.86 | 0.45 | 4.89 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 28 | 4.60 | 0.68 | 4.90 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 20 | |

| Getting an HIV negative test result means I’m not infected | White video | 2.89 | 1.67 | 3.84 | 1.53 | 0.95** | 38 | 3.13 | 1.74 | 4.38 | 1.19 | 1.25** | 32 | 3.07 | 1.69 | 3.76 | 1.64 | 0.69 | 29 |

| African American video | 3.44 | 1.54 | 3.33 | 1.66 | −0.11 | 36 | 3.29 | 1.54 | 4.32 | 1.19 | 1.03** | 28 | 3.30 | 1.90 | 3.35 | 1.84 | 0.05 | 20 | |

| How likely are you to use a condom during vaginal sex? | White video | 3.72 | 1.62 | 4.36 | 1.25 | 0.64** | 25 | 3.09 | 1.90 | 3.23 | 1.93 | 0.14 | 22 | 3.11 | 1.63 | 3.53 | 1.58 | 0.42* | 19 |

| African American video | 3.21 | 1.74 | 3.25 | 1.80 | 0.04 | 24 | 2.83 | 2.01 | 3.00 | 1.97 | 0.17 | 18 | 3.54 | 1.81 | 4.00 | 1.73 | 0.46 | 13 | |

| How likely are you to use a condom during anal sex? | White video | 3.67 | 1.53 | 4.67 | 0.58 | 1.00 | 3 | 2.33 | 1.75 | 2.33 | 1.63 | 0.00 | 6 | 2.50 | 1.98 | 2.83 | 1.84 | 0.33 | 6 |

| African American video | 2.67 | 2.08 | 2.67 | 2.08 | 0.00 | 3 | 4.60 | 0.89 | 4.60 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 5 | 0 | ||||||

p<.05,

p<.01.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded, in part, by a Mitchell Leaska Dissertation Research Award from the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development at New York University. The first author was supported as a postdoctoral fellow in the Behavioral Sciences Training in Drug Abuse Research program sponsored by Public Health Solutions and National Development and Research Institutes with funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (5T32 DA07233). Points of view, opinions, and conclusions in this article do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Government, Public Health Solutions, or National Development and Research Institutes.

Dr. Jan L. Plass and Dr. Perry N. Halkitis, both of New York University, made tremendously valuable contributions to this research and deserve the greatest thanks. Dr. W. Michael Reed also made deeply important contributions to this work and, sadly, passed away shortly after the study had been completed. He is dearly missed. Dr. Buffie Longmire-Avital and Tavinder Ark helped with data analysis. People who appear in two of the video segments work in the AIDS Clinical Trial Unit at Beth Israel Medical Center. Dr. José Antonio Capriles Quirós of the University of Puerto Rico assisted in the development of two additional video segments. The authors thank all members of the emergency department staff who assisted with data collection. Without their assistance, this study would not have been possible.

Contributor Information

Ian David Aronson, New York University and National Development and Research Institutes, Inc., New York.

Theodore C. Bania, St. Luke’s-Roosevelt/Columbia University, New York

References

- Aronson J, Fried CB, Good C. Reducing the effects of stereotype threat on African American college students by shaping theories of intelligence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2002;38:113–125. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J, Lustina MJ, Good C, Keough K, Steele CM, Brown J. When White men can’t do math: Necessary and sufficient factors in stereotype threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1999;35:29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby FG, Isen IM, Turken AU. A neuropsychological theory of positive affect and its influence on cognition. Psychological Review. 1999;106:529–550. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astleitner H. Designing emotionally sound instruction: The FEASP-approach. Instructional Science. 2000;28(3):169–198. [Google Scholar]

- Astleitner H. Principles of effective instruction—general standards for teachers and instructional designers. Journal of Instructional Psychology. 2005;30:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. In: DiClemente R, Peterson J, editors. Preventing AIDS theories and methods of behavioral interventions. New York: Plenum; 1994. pp. 173–201. [Google Scholar]

- Biener L, McCallum-Keeler G, Nyman AL. Adults’ response to Massachusetts anti-tobacco television advertisements: Impact of viewer and advertisement characteristics. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:401–407. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.4.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branson BM, Handsfield HM, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2006;55:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Coury-Doniger P, Senn TE, Vanable PA, Urban MA. Improving HIV rapid testing rates among STD clinic patients: a randomized controlled trial. Health Psychology. 2008;27:833–838. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durantini MR, Albarracîn D, Mitchell AL, Earl AN, Gillette JC. Conceptualizing the influence of social agents of behavior change: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of HIV-prevention interventionists for different groups. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:212–248. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Theoretical approaches to individual level change in HIV risk behavior. In: Peterson J, DiClemente R, editors. Handbook of HIV prevention. New York: Klumer Academic/Plenum Press; 2000. pp. 3–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P, Ciccarone D, Gansky SA, Bangsberg DR, Clannon K, McPhee SJ, et al. Interactive “video doctor” counseling reduces drug and sexual risk behaviors among HIV-positive patients in diverse outpatient settings. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001988. Retrieved February 5, 2010, from http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0001988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiene SM, Barta WD. A brief individualized computer-delivered sexual risk reduction intervention increases HIV/AIDS preventive behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:404–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant RC, Gee EM, Clark MA, Mayer KH, Seage GR, DeGruttola VG. Comparison of patent comprehension of rapid HIV pretest fundamentals by information delivery format in an emergency department setting. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:238–250. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant RC, Clark MA, Mayer KH, Seage GR, DeGruttola VG, Becker BM. Video as an effective method to deliver pretest information for rapid human immunodeficiency testing. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2009;16:124–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York State Department of Health. Frequently asked questions regarding the amended HIV testing law. n.d Retrieved September 24, 2010, from http://www.ny-health.gov/diseases/aids/testing/amended_law/faqs.htm.

- Roye C, Silverman PP, Krauss B. A brief, low-cost, theory-based intervention to promote dual method use by Black and Latina female adolescents: A randomized clinical trail. Health Education and Behavior. 2007;34:608–621. doi: 10.1177/1090198105284840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte K, Allen A. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education and Behavior. 2000;27:591–615. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]