Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To conduct a prospective study to examine whether there are pre-treatment and post-treatment disparities in urinary, sexual, and bowel QOL by race/ethnicity, education, or income in men with clinically localized PCa.

METHODS

Participants (N=1508; 81% White; 12% Black; 7% Hispanic; 50% surgery; 27% radiotherapy; 23% active surveillance) completed the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-50) measure of PCa-specific QOL prior to treatment, 6 weeks, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after treatment. We analyzed pre-treatment differences in QOL with multivariable linear regression and post-treatment differences with generalized estimating equation models.

RESULTS

Blacks and Hispanics (compared to Whites), and men with lower income had worse pretreatment urinary function; poorer and less educated men had worse pre-treatment sexual function (p<.05). In adjusted models, among men treated surgically, Blacks and Hispanics had worse bowel function compared to Whites and men with lower income experienced more sexual bother and slower recovery in urinary function. Not all racial/ethnic differences favored Whites; Blacks had higher sexual function than Whites prior to surgery and improved faster post-surgery. Blacks receiving radiotherapy had lower post-treatment bowel bother than Whites (p<.05).

CONCLUSION

Controlling for baseline QOL, there were some post-treatment disparities in urinary and sexual QOL that suggest the need to investigate whether treatment quality and access to follow-up care is equitable. However, survivorship disparities may, to a greater extent, reflect disadvantages in baseline health that exacerbate QOL issues after treatment.

Keywords: Prostate Neoplasm, Quality of Life, Disparities, Race/Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status

There are close to three million prostate cancer (PCa) survivors in the U.S., constituting 43% of all male cancer survivors.1 Quality of survivorship is a major concern with respect to PCa care as most patients will die with, rather than of their disease and many live with treatment-related side effects. Estimates of the prevalence of side effects vary considerably. Most men treated surgically experience urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction, with urinary function improving in the year after surgery and sexual function improving in two years.2 In one study, two years post-surgery, 52% of men with functional erections before treatment had erectile dysfunction.3 In another large study, 60% of men had erectile dysfunction 18 months postoperatively.4 Men who receive radiotherapy are most likely to experience erectile dysfunction and bowel side-effects that can increase in severity over time.5 Of concern is whether vulnerable groups, including racial/ethnic minorities and men with low income or educational attainment disproportionately experience decrements in QOL after PCa treatment. Some evidence indicates this may be the case.

There have been a small number of studies of racial/ethnic disparities in PCa QOL during survivorship, including three large-scale studies.3, 6–8 Results provide an incomplete and sometimes inconsistent picture of racial/ethnic differences in QOL among PCa survivors, in part because the studies examine varying stages of survivorship, different populations, and diverse facets of QOL. Data from these studies are also relatively old, collected between 1994 and 2006, and may not reflect the evolution of PCa care.

Findings for African American men are mixed. In the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study (PCOS), among men treated surgically, African American survivors reported better sexual function at 5 years, although they were also more likely to report sexual bother or perceived problems with function than Whites.6 Blacks also reported better urinary function and lower bother than Whites among men treated with radiotherapy. In the Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor (CaPSURE) study, Black men had worse urinary function and bother and worse bowel function and bother than Whites.8 More recently (data collected 2003 to 2006), in the Prostate Cancer Outcomes and Satisfaction with Treatment Quality Assessment (PROSTQA) study, African American men, 2 years post-brachytherapy had better erectile function than the White/other group. Function did not differ by race/ethnicity among the men treated with either surgery or external beam radiation.3 Single institution studies have been reviewed elsewhere7: the number of minority participants included in the studies have been small and findings have been mixed. One of the largest, with a sample of 665 men (30.5% African American), indicated that African Americans experienced a greater drop in urinary function than Whites 1 year after treatment regardless of treatment received.9

Hispanics have rarely been studied. One exception was PCOS which reported disparities among Hispanics. Compared to Whites, Hispanic men were more likely to report that their sexual function was a problem.6 Given the widely varying results of past studies and lack of attention to Hispanic men, we sought to update the literature on racial/ethnic differences in QOL.

Associations between socioeconomic status (SES) and QOL in PCa survivors have been reported infrequently.10 Assessments of CaPSURE participants 2 years after treatment indicated almost no differences in QOL as a function of income or education. In a study of 204 White, Black, and Hispanic PCa survivors assessed within 18 months of starting treatment Penedo et al., found that men with lower income and education had lower general QOL; however they were unable to account for baseline QOL in their analyses.11

In the present study we examined whether there are pre and post-treatment differences in urinary, bowel, and sexual function and bother by race/ethnicity, education, and income, including whether there are differences in the temporal trajectory of these dimensions over time. We separately examined QOL in men who received surgery and radiotherapy as their primary treatments, and men who were managed with active surveillance. We hypothesized that we would find a pattern of differences indicating that disadvantaged men- Blacks, Hispanics, men with low income and men with low education- experience worse pre and post-treatment quality of life for multiple dimensions of QOL.

METHODS

Data source and procedure

We analyzed data from the xxx study in which men with clinically localized PCa were recruited at, or shortly after diagnosis. Men were recruited at two comprehensive cancer centers and three large group practices between 2010 and 2014. As it was not possible to approach all men as the large group practices had multiple clinic sites, priority was always given to recruiting minority patients in an effort to enrich this subsample. Additional information about the procedure is reported elsewhere.XX We approached 3,337 patients, of which 2,476 were consented, and 2,008 completed a baseline survey prior to treatment. We surveyed men again 6 weeks (n=1,679), 6 months (n=1,638), 12 months (1,580), 18 months (n=1,394), and 24 months (n=1184) post-surgery. We abstracted clinical information from medical records post-treatment (n=1946). All procedures were institutional review board approved. As the number of men who were a race/ethnicity other than White, Black, or Hispanic was too small to analyze separately (n=25), data from these individuals were excluded. After excluding cases missing data on predictors and covariates, the final sample included 1,508 men.

Measures

As side effect profiles vary by treatment modality, and treatments are received at different rates across race/ethnicity and SES groups, we stratified by treatment type for all analyses of post-treatment data. Men were categorized depending on whether they had been treated with surgery or radiotherapy (external beam radiation, brachytherapy, external beam radiation and brachytherapy, or proton therapy), or managed with active surveillance. The three predictors of interest were a) self-reported race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black, hereafter referred to as White and Black, and Hispanic), b) education attainment, a continuous variable ranging from having completed first grade to fourth year of graduate school, and c) a 9-level income variable ranging from <$5,000 to ≥$100,000.

Covariates included D’Amico disease risk. Low-risk PCa was defined as clinical stage PSA≤10 ng/mL, Gleason score ≤6, and American Joint Commission of Cancer Staging (AJCC) less than cT2b.12 Intermediate-risk PCa was defined as PSA >10 and ≤20 ng/mL or Gleason 7 disease or AJCC cT2b. High-risk disease was defined as PSA >20 ng/mL or Gleason 8–10 disease or AJCC cT2c or higher.12 We also controlled for whether men had received androgen deprivation therapy along with their primary treatment. As comorbid disease may be associated with QOL as well as the predictors, we abstracted information on 23 comorbidities included in the calculation of the Charlson Index. For a given QOL outcome we controlled for any comorbidity that was associated with the outcome at a time point other than baseline at the p<.05 level with Bonferroni correction for multiple tests. In sexual function models we controlled for diabetes, coronary artery disease, and hypertension, and in sexual bother models we controlled for diabetes. In bowel function models we controlled for cerebrovascular disease. In bowel bother models we controlled for cerebrovascular disease and diabetes. All models included age at diagnosis, whether men were working or not, and recruitment site, although the latter is not included in the tables as the reference point is arbitrary. Finally, we controlled for baseline QOL scores. Men’s corresponding baseline functioning or bother was entered for the outcome of interest (e.g., when the outcome was post-treatment urinary function we included pre-treatment urinary function in the model).

The outcomes of interest were urinary, bowel, and sexual QOL assessed with the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-50), a 50-item PCa health-related quality of life scale (α≥;0.82).13 EPIC assesses both function (how frequently one has been affected by a treatment-related side effect during the previous 4 weeks) and bother by side effects (‘how big a problem’ were these side effects). Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing greater function/less bother.

Data Analyses

We explored attrition with bivariate logit models and descriptive statistics, comparing those who were excluded from the multivariable analyses due to not completing any follow-up surveys and the original sample of participants who completed the baseline survey. We examined whether there were adjusted differences in pre-treatment QOL as a function of race/ethnicity, income and education using multivariable linear regression. Covariates included associated comorbities, D’Amico risk score, age at diagnosis, education, race/ethnicity, employment status, marital status, income, and site where participants were recruited. We used general estimating equation (GEE) models to test for differences in adjusted QOL averaged across time and QOL trajectories over time by race/ethnicity, education, and income. For each treatment group we tested four models: a single main effects model for race/ethnicity, education, income, and time, and three interaction effects models that each included an interaction between one of the predictors and time. We repeated this for each of the six quality of life dimensions (urinary, bowel, and sexual function and bother). We controlled for baseline QOL, whether men received androgen deprivation therapy along with their primary treatment, and the clinical and demographic covariates described above. We used GEE to account for non-independence of predictors and outcomes14 as time-points were nested within participants and participants within sites, although participants were treated at far more facilities than the 5 recruiting sites given that many went on to be treated elsewhere. Gaussian family was specified as the QOL outcomes were continuous. For all multivariable models we used robust standard errors so that if the nature of the correlation structure was not correctly specified, the standard errors would still be valid.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. A majority of patients had low (35.7%) or intermediate (47.6%), rather than high (16.6%) disease risk. About half of the participants (50.3%) were treated surgically, 27.1% with radiotherapy, and 22.6% with active surveillance. In addition, 12.1% received androgen deprivation therapy along with their primary treatment, of whom (91.7%) received radiotherapy as their primary treatment. Most participants were non-Hispanic White (80.8%), had a median education of college or greater, and a mean income of $75,000 to $99,999.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (N = 1508)

| Characteristic | N | % or mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment Choice | ||

| Active Surveillance | 341 | 22.61 |

| Radiotherapy | 408 | 27.06 |

| Surgery | 759 | 50.33 |

| D’Amico Risk | ||

| Low Risk | 539 | 35.74 |

| Intermediate Risk | 718 | 47.61 |

| High Risk | 251 | 16.64 |

| Received Hormone Therapy | 182 | 12.07 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 153 | 10.15 |

| Hypertension | 734 | 48.67 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 22 | 1.46 |

| Diabetes | 203 | 13.46 |

| Race | ||

| White | 1218 | 80.77 |

| Black | 184 | 12.20 |

| Hispanic | 106 | 7.03 |

| Education | ||

| < 12 years | 52 | 3.45 |

| 12 years | 252 | 16.71 |

| 13–16 years | 693 | 45.95 |

| > 16 years | 511 | 33.89 |

| Income | ||

| < $25,000 | 109 | 7.23 |

| $25,000 – $49,999 | 191 | 12.67 |

| $50,000 – $74,999 | 228 | 15.12 |

| $75,000 – $99,999 | 210 | 13.93 |

| ≥$100,000 | 770 | 51.06 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Employed | 930 | 61.67 |

| Not Employed | 578 | 38.33 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married/cohabitating | 1251 | 82.96 |

| Not married/cohabitating | 257 | 17.04 |

| Age | 1508 | 66.67 (7.97) |

Note: Percentages may not equal 100% due to rounding. Income and education were continuous variables in the multivariable models.

Attrition

Participants who had at least one follow-up data point were included in analyses of follow-up time points. Depending on the amount of missing data for the QOL outcomes, there were 385–414 fewer participants in the dataset than completed the baseline survey (see Supplemental Table 1 for a comparison between the baseline sample and smallest GEE sample).

Baseline differences in QOL

Worse baseline pre-treatment scores for each QOL domain was associated with worse post-treatment QOL regardless of treatment (ps ≤.001; not presented in Tables). Men’s pre-treatment QOL varied by race/ethnicity and SES, with minorities experiencing worse QOL in some domains and poorer and less educated men experiencing disparities in pre-treatment QOL in many domains. Blacks (b = −3.07, 95% CI = −5.13, −1.01, p=.004) and Hispanics (b = −2.79, 95% CI = −5.48, −0.11, p =.041) had worse pretreatment urinary function than Whites. In contrast, Hispanics reported less bowel bother than Whites (b = 2.60, 95% CI = 0.66, 4.53, p=.009). Men with lower income had worse urinary function (b = 0.98, 95% CI = 0.50, 1.47, p<.001) and bother (b = 1.09, 95% CI = 0.46, 1.72, p<.001). Lower income was associated with worse sexual function (b = 1.63, 95% CI = 0.77, 2.48, p<.001) and more bowel bother (b = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.06, 0.86, p=.025). Lower education was associated with worse sexual function (b = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.40, 1.30, p<.001) and more sexual bother (b =1.46, 95% CI = 0.84, 2.07, p<.001). Table 2 summarizes when results indicated disadvantage or advantage for the target groups.

Table 2.

Summary or pre-treatment and post-treatment differences in QOL by treatment type

| QOL dimension | Black vs. White | Hispanic vs. White | Income gradient | Education gradient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary | Pre- treatment | disadvantage | disadvantage | disadvantage | |

| Post- surgery | disadvantage | ||||

| Post- radiotherapy | |||||

| Bowel | Pre- treatment | advantage | |||

| Post- surgery | disadvantage | disadvantage | |||

| Post- radiotherapy | advantage | ||||

| Sexual | Pre- treatment | disadvantage | disadvantage | ||

| Post- surgery | advantage | disadvantage | |||

| Post- radiotherapy | advantage |

Adjusted differences in QOL by race/ethnicity

Along with potential covariates, adjusted models controlled for baseline function or QOL among Blacks, Hispanics, men with low income, and men with low education. Among men receiving surgery, Blacks (−2.55, 95% CI = −4.75, −0.35, p = .023) and Hispanics (−3.78 95% CI = −6.37, −1.19, p = .004) had worse bowel function post-surgery compared to Whites. However, the differences were eliminated over time. Bowel function among Blacks and Hispanics improved more rapidly than that of Whites such that by two years post-treatment they had the same level of functioning as Whites [Blacks (1.25, 95% CI = 0.36, 2.14, p = .006; Hispanics (1.05, 95% CI = 0.10, 2.01, p = .03)]. Controlling for pre-treatment sexual function, Blacks also experienced faster and greater improvement in sexual function over time compared to Whites (2.56, 95% CI = 0.88, 4.24, p = .003).

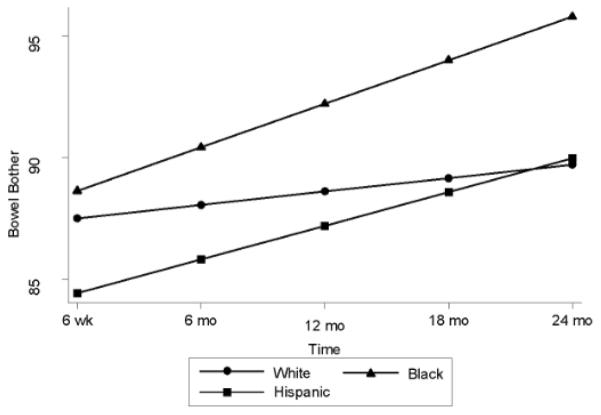

Among men who received radiotherapy, Blacks reported less bowel bother compared to Whites (3.20, 95% CI = 0.59, 5.81, p = .016). Over time, Blacks’ bowel bother improved, whereas scores remained relatively steady among Whites over time (1.24, 95% CI = 0.07, 2.41, p = .038; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Post-Treatment Bowel Bother over Time among Men Treated with Radiotherapy Stratified by Race/Ethnicity

Among men on active surveillance, Hispanics reported less sexual bother (10.34, 95% CI = 1.05, 19.63, p = .029) than Whites.

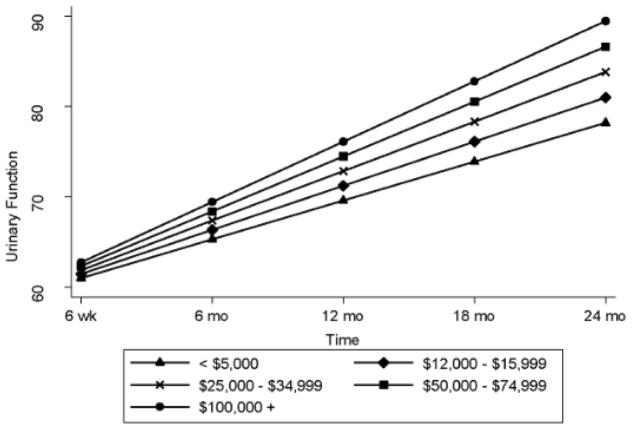

Differences and temporal trends in QOL by income

Controlling for pre-treatment sexual bother, among men who received surgery, men with lower income had greater sexual bother (2.42, 95% CI = 0.64, 4.20, p = .008) than men with higher incomes. They also experienced less improvement in urinary function over time than men with higher incomes (0.30, 95% CI = 0.07, 0.53, p = .012; Figure 2). However, among men who received radiotherapy, lower income was associated with better sexual function (−1.17, 95% CI = −2.16, −0.18, p = .021).

Figure 2.

Post- Treatment Urinary Function over Time among Men Treated Surgically Stratified by Income

Controlling for baseline QOL, men on active surveillance with lower incomes had relatively worse bowel function (0.63, 95% CI = 0.16, 1.09, p = .008) and more sexual bother (1.99, 95% CI = 0.10, 3.87, p = .039).

Differences and temporal trends in QOL by education

Controlling for pre-treatment QOL, the only post-treatment difference as a function of education was in men on active surveillance: less educated men reported better bowel function (−0.26, 95% CI = −0.51, −0.003, p = .047) than more educated men.

DISCUSSION

Prior to treatment, minorities, poorer men and men with less education had worse functioning and more bother in several QOL domains. Lower pre-treatment QOL among Blacks8, 15 and poorer men16 have been noted previously. This is important because pre-treatment deficits (or advantages) in QOL predicted post-treatment QOL and are likely contributing to QOL deficits among disadvantaged men. Disparities in PCa QOL may in part be attributable to health disparities that affect historically disadvantaged populations over their lifespan. For example, chronic diseases of the circulatory system, diabetes, and some autoimmune disorders that are more common among minorities and people with low SES17–19 are risk factors for sexual, urinary, and bowel dysfunction.20–22

Contrary to our hypotheses, adjusted models revealed few racial/ethnic disparities in QOL indicating that the disparities were rarely uniquely attributable to differential consequences of treatment. Also, consistent with results from PCOS6, Blacks had higher sexual function than Whites prior to treatment and also experienced faster improvement after treatment. Black men treated with surgery reported worse bowel QOL than Whites, but the reverse was true for men treated with radiotherapy. Poorer men may be at a disadvantage when men are treated surgically; men with lower income experienced more sexual bother and slower recovery in urinary function. Low income men could experience worse side-effects from treatment if they receive different levels of follow-up care; for example, some health care plans do not cover treatments for erectile dysfunction. Men may also differ in how proactive they are in seeking treatment for side-effects. In the PCa population in general, although to a lesser extent in our sample, access to high quality initial treatment can also vary.23

Are QOL disparities clinically significant?

Skolarus and colleagues have identified clinically minimally important differences (MIDs) on the EPIC-26 (highly correlated with EPIC-5024) by functional domain.25 They report that differences in function ranging from 6–9 for the incontinence subscale and 5–7 for the irritative/obstructive subscale of the urinary function (we report total urinary function scores), 4–6 for bowel function, and 10–12 for sexual function are likely MIDs for clinical significance. Adjusted differences between our poorest and wealthiest participants in baseline functioning were approximately 7.8 and 13.0 points for urinary and sexual function, respectively. These meet or nearly meet MID thresholds. Differences as a function of education were smaller, as were differences by race/ethnicity. However, post-treatment differences in bowel function between minorities and Whites approached these criteria. They were 3.6 for Blacks and 3.8 for Hispanics.

Limitations

Attrition was a study limitation. Participants excluded from analyses of follow-up time points differed demographically and clinically from the sample that completed the baseline survey but did not differ with respect to QOL. In addition to avoiding attrition, we wished we had been able to recruit a larger sample of minorities, as there may have been disparities we did not detect due to small sample size. Another limitation is generalizability; participants were a convenience sample and findings may not generalize to all PCa survivors. Future work should address the need to explain disparities and advantages. Information about tumor biology, treatment and follow-up clinical care could help explain the source of disparities and advantages. We also did not collect data on patients’ expectations about side-effects. It is possible that disappointment due to discrepancies between pre-treatment expectations and post-treatment reality 26 could result in lower perceived QOL.

CONCLUSION

The most common side-effects of PCa treatment are urinary, sexual and bowel function-related; their impact on QOL can be substantial for many men.27 As there are treatments and supports for men living with PCa treatment side-effects,28, 29 future work should examine whether historically disadvantaged men, in particular poorer men, have access to the same level of post-treatment follow-up care as their more advantaged counterparts. Where there are known inequities such as for access to erectile dysfunction treatment, physicians and hospitals may need to advocate for their patients and for changes to payers’ practices. As disparities in survivorship likely also reflect disadvantages in baseline health, primary care providers and even specialists may recognize a PCa diagnosis as a teachable moment for encouraging lifestyle change and better medication management in patients with comorbid chronic disease. Discussion about the role of these diseases in QOL may help more fully inform men about their health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Live Well Live Long! research group includes Integrated Medical Professionals, site-PI, Carl A. Olsson and CEO Deepak A. Kapoor; Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Institute, site-PI, Christian J. Nelson; Urology San Antonio, site-PI Juan A. Reyna; Houston Metro Urology, P.A., site-PI Zvi Schiffman, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, site-PI, Willie Underwood, III, and the University at Buffalo, site-PI, Heather Orom. We would like to acknowledge the cooperation and efforts of the staff and physicians at these sites for their significant contribution to participant recruitment. This research was supported by funding from the National Cancer Institutes (R01#CA152425).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:252–271. doi: 10.3322/caac.21235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1250–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alemozaffar M, Regan MM, Cooperberg MR, et al. Prediction of erectile function following treatment for prostate cancer. JAMA. 2011;306:1205–1214. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stanford JL, Feng Z, Hamilton AS, et al. Urinary and sexual function after radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer: the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. JAMA. 2000;283:354–360. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller DC, Sanda MG, Dunn RL, et al. Long-term outcomes among localized prostate cancer survivors: Health-related quality-of-life changes after radical prostatectomy, external radiation, and brachytherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2772–2780. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson TK, Gilliland FD, Hoffman RM, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in functional outcomes in the 5 years after diagnosis of localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4193–4201. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnett AL. Racial disparities in sexual dysfunction outcomes after prostate cancer treatment: myth or reality? Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities. 2016;3:154–159. doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lubeck DP, Kim H, Grossfeld C, et al. Health related quality of life differences between black and white men with prostate cancer: Data from the cancer of the prostate strategic urologic research endeavor. J Urol. 2001;166:2281–2285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice K, Hudak J, Peay K, et al. Comprehensive quality-of-life outcomes in the setting of a multidisciplinary, equal access prostate cancer clinic. Urology. 2010;76:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.03.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsey SD, Zeliadt SB, Hall IJ, et al. On the importance of race, socioeconomic status and comorbidity when evaluating quality of life in men with prostate cancer. J Urol. 2007;177:1992–1999. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penedo FJ, Dahn JR, Shen BJ, et al. Ethnicity and determinants of quality of life after prostate cancer treatment. Urology. 2006;67:1022–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:969–974. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, et al. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56:899–905. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Regression analysis for correlated data. Annu Rev Public Health. 1993;14:43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.14.050193.000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rice K, Hudak J, Peay K, et al. Comprehensive quality-of-life outcomes in the aetting of a multidisciplinary, equal access prostate cancer clinic. Urology. 2010;76:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.03.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penson DF, McLerran D, Feng Z, et al. 5-Year urinary and sexual outcomes after radical prostatectomy: Results from the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J Urol. 2005;179:S40–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calixto OJ, Anaya JM. Socioeconomic status. The relationship with health and autoimmune diseases. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2014;13:641–654. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ski CF, King-Shier KM, Thompson DR. Gender, socioeconomic and ethnic/racial disparities in cardiovascular disease: A time for change. Int J Cardiol. 2014;170:255–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.10.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaskin DJ, Thorpe RJ, McGinty EE, et al. Disparities in diabetes: The nexus of race, poverty, and place. Am J Public Health. 2013;104:2147–2155. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu CJ, Hsu CC, Lee WC, et al. Medical diseases affecting lower urinary tract function. Urological Science. 2013;24:41–45. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shamloul R, Ghanem H. Erectile dysfunction. The Lancet. 2013;381:153–165. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60520-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ditah I, Devaki P, Luma HN, et al. Prevalence, trends, and risk factors for fecal incontinence in United States adults, 2005–2010. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014;12:636–643.e632. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gooden KM, Howard DL, Carpenter WR, et al. The effect of hospital and surgeon volume on racial differences in recurrence-free survival after radical prostatectomy. Med Care. 2008;46:1170–1176. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817d696d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szymanski KM, Wei JT, Dunn RL, et al. Development and validation of an abbreviated version of the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Instrument (EPIC-26) for measuring health-related quality of life among prostate cancer survivors. Urology. 2010;76:1245–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skolarus TA, Dunn RL, Sanda MG, et al. Minimally important difference for the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form. Urology. 2015;85:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schroek FR, Krupski TL, Sun L, et al. Satisfaction and regret after open retropubic or robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2008;54:785–793. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eton D, Lepore S, Helgeson V. Early quality of life in patients with localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92 doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6<1451::aid-cncr1469>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roth AJ, Weinberger MI, Nelson CJ. Prostate cancer: Quality of life, psychosocial implications and treatment choices. Future oncology. 2008;4:561–568. doi: 10.2217/14796694.4.4.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skolarus TA, Wolf AM, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.