Abstract

Grain number per panicle (GNP) is a major determinant of grain yield in cereals. However, the mechanisms that regulate GNP remain unclear. To address this issue, we isolate a series of sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] multiseeded (msd) mutants that can double GNP by increasing panicle size and altering floral development so that all spikelets are fertile and set grain. Through bulk segregant analysis by next-generation sequencing, we identify MSD1 as a TCP (Teosinte branched/Cycloidea/PCF) transcription factor. Whole-genome expression profiling reveals that jasmonic acid (JA) biosynthetic enzymes are transiently activated in pedicellate spikelets. Young msd1 panicles have 50% less JA than wild-type (WT) panicles, and application of exogenous JA can rescue the msd1 phenotype. Our results reveal a new mechanism for increasing GNP, with the potential to boost grain yield, and provide insight into the regulation of plant inflorescence architecture and development.

Inflorescence architecture affects crop grain yield. Here, the authors deploy whole-genome sequencing-based bulk segregant analysis to identify the causal gene of a sorghum multi-seeded (msd) mutant and suggest MSD1 regulating the fertility of the pedicellate spikelets through jasmonic acid pathway.

Introduction

Sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench], is a versatile C4 grass with high efficiency in conversion of solar energy, superior drought tolerance relative to most other crops, and multiple uses as livestock feed, starch ethanol production, and human food. It is the fifth most important cereal crop in both acreage and production worldwide1, 2. In light of its compact genome (~730 Mb), which has been completely sequenced, sorghum is also an attractive functional genomics model for maize, sugarcane, Miscanthus, and other C4 bioenergy crops with complex genomes3–6.

Grain number per panicle (GNP) is one of the most important contributors to grain yield in sorghum and other crops7, and this property is related to inflorescence architecture1, 8. The sorghum inflorescence exhibits a determinate panicle at the end of the shoot meristem; the main inflorescence bears primary branches at each node, and subsequent secondary or tertiary branches develop from the primary branches9, 10. Each inflorescence branch bears a terminal trio of floral spikelets: one sessile spikelet (SS) directly attached to the inflorescence branch and two pedicellate spikelets (PSs) attached to the inflorescence branch through a pedicel. Below the terminal spikelets, several spikelet pairs develop with one SS and one PS each. To date, in all known sorghum accessions in plant gene banks (e.g., www.ars-grin.gov) and germplasm repositories, only the SS, but not the PS, produces a perfect flower that sets grain (Fig. 1a). The PS occasionally develops anthers but no carpel tissues11. It remains unknown why the PS cannot develop into perfect flowers and produce viable grains.

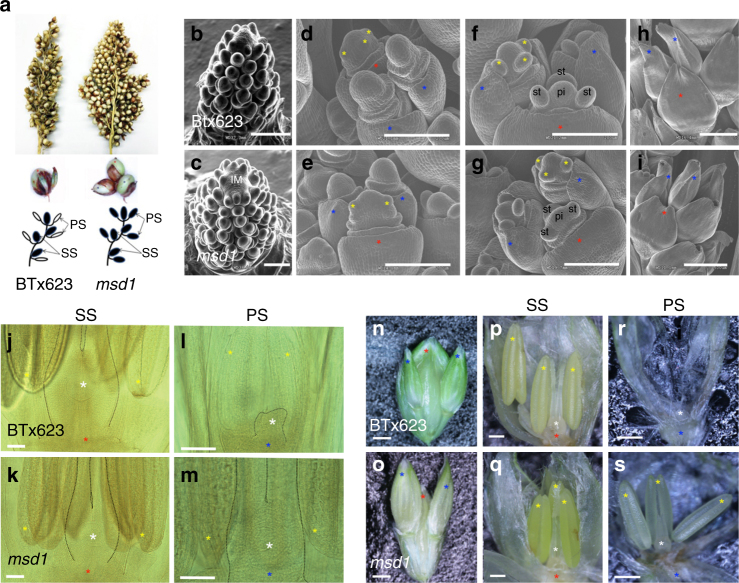

Fig. 1.

MSD1 suppresses floral organ PS at developmental stage 4. a Photographs of primary branches of the panicle (adaxial side) of BTx623 (wild type, WT) and msd1. Images immediately below show terminal spikes: WT has one sessile grain, whereas msd1 has three grains, one sessile and two pedicellate. The diagram provides a schematic representation of a secondary branch depicting SS and PS in WT and msd1: left, WT; right, msd1. SS sessile spikelet, PS pedicellate spikelet. b–i Detailed scanning electron microscopy analysis of inflorescence development, comparing WT and msd1. b, c Inflorescence meristem (IM) of WT (b) and msd1 (c). Bar: 500 μm; (d, e) floral transition in WT (d) and msd1 (e). Bar: 200 μm; three young stamen primordia initiate in SS of both WT and msd1 (d, e); (f, g) developing stamen and pistil primordia in PS and SS of BTx623 and msd1 (g) Bar: 200 μm. In f and g, ‘st’ indicates stamen primordia and ‘pi’ indicates pistil primordia; h, i young PS and SS at developmental stage 4. Bar: 200 μm. Yellow asterisks in panels d–i indicate young stamen primordia. j–m Photomicrographs (lateral view) of floral organ development at stage 4 in PS and SS using cleared spikelets (see Methods). Artificial contour lines were added to emphasize carpel and ovary. Ovary was fully developed only in SS of WT but in both SS and PS of msd1. White asterisk indicates ovary, and yellow asterisks indicate anthers. Bar: 100 μm. n–s Fully developed (mature) spike of WT (n) and msd1 (o) at stage 5; dissected mature (lemma and palea pulled away) SS of WT (p) and msd1 (q); and mature PS of WT (r) and msd1 (s). White asterisk indicates ovary, and yellow asterisks indicate anthers. Bar: 1 mm. d–s Red asterisks indicate SS, and blue asterisks indicate PS

Jasmonic acid (JA), a plant hormone derived from free α-linolenic acid with structural similarities to animal prostaglandins12, 13, plays diverse roles in plant adaptation to biotic and abiotic stresses and development12, 14, 15. During inflorescence development, JA regulates pollen development or pollen shedding in Arabidopsis16, embryo and seed development in tomato17, 18, spikelet formation in rice19, and sex determination in maize20–22. However, despite numerous studies focused on JA biosynthetic pathways and signaling, the regulation of JA biosynthesis during inflorescence development remains elusive.

Here we report on the characterization of a sorghum mutliseeded1 (msd1) mutant that produces normal grains from both SS and PS, the latter of which is aborted in all non-mutagenized sorghum accessions. Using bulked segregant analysis of next-generation sequencing data from pooled msd1 mutants selected from a F2 population, we identify the MSD1 gene, which encodes a plant-specific transcription factor with a TCP domain. The TCP designation is coined based on the names of three founding genes: Teosinte branched 1 (Tb1) in maize, Cycloidea (Cyc) in snapdragon, and Proliferating Cell nuclear antigen binding Factor (PCF) in rice23–25. TCP transcription factors play diverse roles in the formation of plant architecture and development26–28. Our results suggest that MSD1 regulates PS development in sorghum through activation of JA biosynthesis and signaling.

Results

msd1 mutants produce fertile pedicellate spikelets

In a series of msd mutants identified from an EMS (ethyl methanesulfonate)-induced mutant population29, both SS and PS developed completely fertile flowers (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, the panicles of msd mutants are much larger than WT due to the greater size and number of inflorescence branches10. Based on scanning electron microscopic analyses, sorghum panicle development can be separated into five stages (Supplementary Fig. 1). At stage 1, branching occurred from the top of the inflorescence meristem (IM) (Fig. 1b–c and Supplementary Fig. 2a). At stage 2, a triple spikelet meristem (TSM) was observed at the top of the IM, while additional branches form below the TSM (Supplementary Fig. 1, 2b). At stage 3, ovary and stamen primordia started to be observed (Fig. 1d–g and Supplementary Fig. 3a). At stage 4, SS can be clearly distinguished from PS. At stage 5, anthers and ovaries can be seen in the SS. A comparison of inflorescence development revealed no differences in panicle morphology between WT and msd1 mutants before stage 3 (Fig. 1d–g). Floral organs initiated normally in both PS and SS in WT and msd1 (Fig. 1b–g and supplementary Fig. 2,3). At stage 4, however, PS arrested in WT but continued to develop in msd1 (Fig. 1h–m). At stage 5, both anthers and ovary were aborted in the PS of WT, but complete floral organs developed in both SS and PS of msd1 (Fig. 1n–s). Together, these results indicate that floral organs initiated in both SS and PS of WT, but that PS sexual organ progression halted early on, and this suppression of floral organs was released in PS of msd1 plants during inflorescence development.

MSD1 encodes a TCP-domain transcription factor

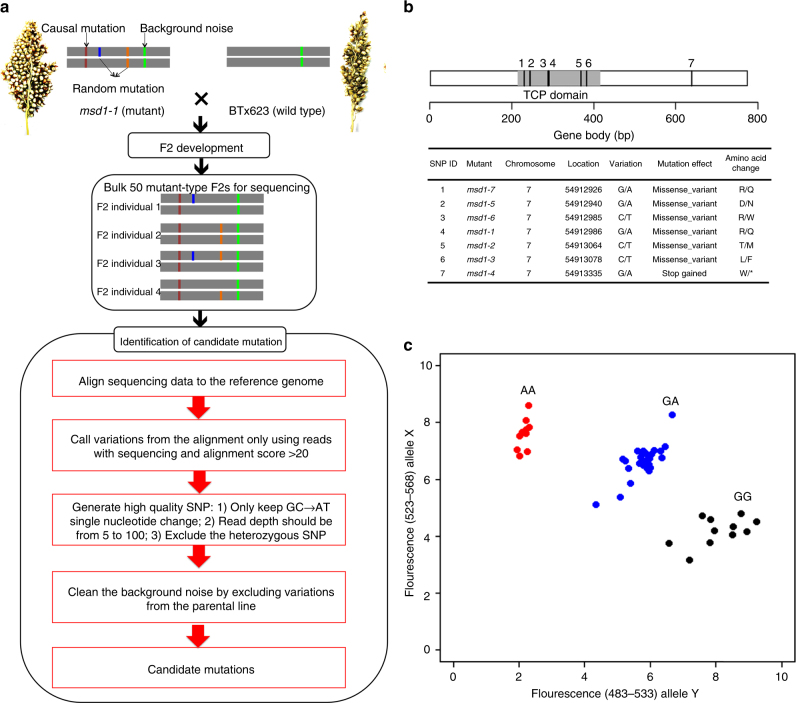

To determine the genetic basis of the msd1 phenotype, we deployed whole-genome sequencing-based bulk segregant analysis to identify the causal gene. To this end, genomic DNA from 50 homozygous msd1-1 mutants selected from an F2 population were pooled and sequenced to about 27× coverage (Fig. 2a). After analysis using our in-house pipeline, we discovered 14 homozygous mutations. Whole-genome sequencing was also performed on the parental line BTx623 and an additional 17 independent homozygous msd mutants, including msd1-1 and msd1-2: two allelic msd1 mutants isolated from independent mutant pools. Only one gene, Sb07g021140, was homozygously mutated in the bulked F2 of msd1-1 and individual msd1-1 and msd1-2 mutants; the msd1-1 and msd1-2 alleles are at different locations in this gene (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, we identified five additional unique mutations in the gene from whole-genome sequencing of the 15 other msd mutants (Fig. 2b). All pairwise crosses among all seven msd1 mutants yielded the msd1 phenotype (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Identification of MSD1 gene in sorghum. a Workflow of bulk segregant analysis combined with whole-genome sequencing, used to identify the causal gene in an msd1-1 F2 population. b Structure of MSD1 (Sb07g021140), depicting the CDS of 774 nucleotides and the TCP domain. The table below shows alleles of msd1 identified by sequencing of 15 msd mutants. c Co-segregation of the msd1-1 mutation in Sb07g021140 with the msd phenotype was analyzed in an F2 population derived from a cross of RTx437×msd1-1. Among the 48 individual F2 plants, 10 with homozygous mutations (AA) had msd panicles, whereas the rest (11 homozygous WT [GG] and 27 heterozygous [GA]) had WT panicles. The phenotype distribution for this population fit a 3:1 WT:msd ratio, with 100% co-segregation of the mutant genotype with the phenotype

To determine whether the trait could be expressed in other sorghum genetic backgrounds, the msd1-1 mutant was crossed to RTx437. Among 48 individual F2 plants, all 10 harboring the homozygous msd1-1 mutation (A/A) had msd1 panicles, whereas the rest (11 homozygous WT [G/G] and 27 heterozygous [G/A]) had WT panicles, supporting the earlier conclusion that Sb07g021140 is the MSD1 gene, and confirming that the msd1 phenotype can be expressed in other genetic backgrounds (Fig. 2c).

MSD1 encodes the class II TCP transcription factor SbTCP16, which belongs to the CYC/TB1 subgroup of the sorghum TCP family28. MSD1 is specific to monocots28. The mutations in the six msd1 mutant alleles that fall within the TCP domain of Sb07g021140 (SbTCP16) occur at amino acid positions that are highly conserved throughout the grasses (Supplementary Fig. 4). None of the seven msd1 mutations discovered in this study are present in diversity panels compiled by sequencing of sorghum natural populations30, 31.

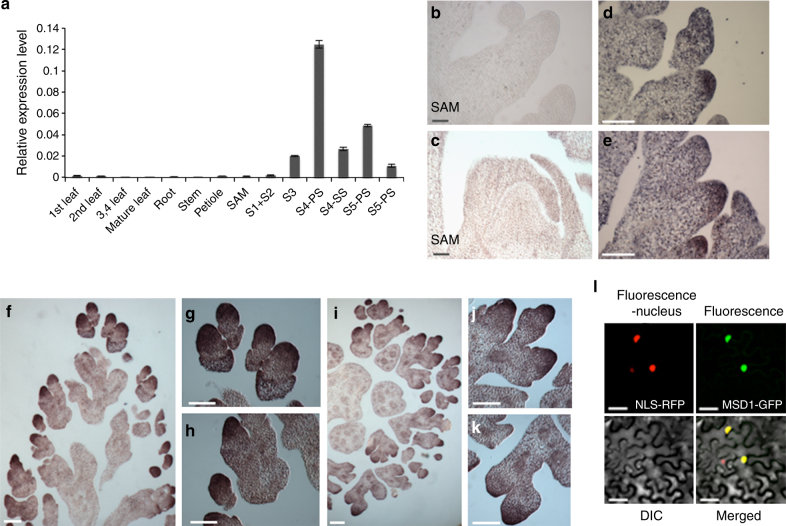

Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) of various tissues revealed that MSD1 expression was enriched during inflorescence development, especially at PS in stage 4 (Fig. 3a), and this expression pattern is also observed in public expression atlas data28, 32. To characterize the temporal and spatial expression pattern of MSD1, we performed RNA in situ hybridization. In a negative control hybridization using a sense probe, MSD1 expression was undetectable in shoot apical meristem and branch primordia (Fig. 3b,c). When using an antisense probe, expression signal was observed during stage 2 in WT plants, localized to the tip of the spikelet meristem (Fig. 3d,e). Expression was maintained at the tip of the floral meristem and then expanded throughout the floral meristem including the glume at stage 3 (Fig. 3f–h). Both transverse and longitudinal sections revealed that MSD1 expression was specifically maintained in a specific dome-like domain of the floral meristem (Fig. 3f–k). At stage 4 (Supplementary Fig. 5), although weak expression of MSD1 was detected in the ovary of both PS and SS, a much stronger signal was observed in anthers. Consistent with the role of MSD1 as a transcription factor, an MSD1–green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion protein exclusively localized in the nucleus in a transient assay using tobacco leaf cells (Fig. 3i), in agreement with a previous prediction28.

Fig. 3.

MSD1 expression analysis in wild type. a Relative expression of MSD1 from qRT-PCR in various tissue types, including leaf, root, stem, petiole, SAM, and inflorescence (stages 1+2, 3, and 4) of PS, SS (stage 4), PS (stage 5), and SS (stage 5). The bars represent mean ± SD of three biological replicates. b–k In situ hybridization of MSD1 during inflorescence development in WT: b Spikelet meristem in stage 2, labeled with sense probe as a negative control. c Longitudinal view of shoot apical meristem. d Spikelet meristem near the top of meristem in stage 2, labeled with antisense probe. e Spikelet meristem at the bottom of meristem in stage 2. f–h Longitudinal section of floral meristem in early stage 3. g and h show magnifications of the floral meristem. i–k Transverse section of floral meristem in early stage 3. Magnifications of the floral meristem at early stage 3 in i are shown in j and k. l Cellular localization of MSD1: confocal images showing MSD1–green fluorescent protein (GFP) localization in tobacco transient assay. Top left: Nuclear Localization Sequence (NLS)-red fluorescent protein (RFP) (control); top right: MSD1-GFP; bottom left: differential interference contrast (DIC) image; bottom right: merged image of NLS-RFP and MSD1-GFP. b–k Bar: 100 μm. I Bar: 50 μm

MSD1 regulates the JA pathway

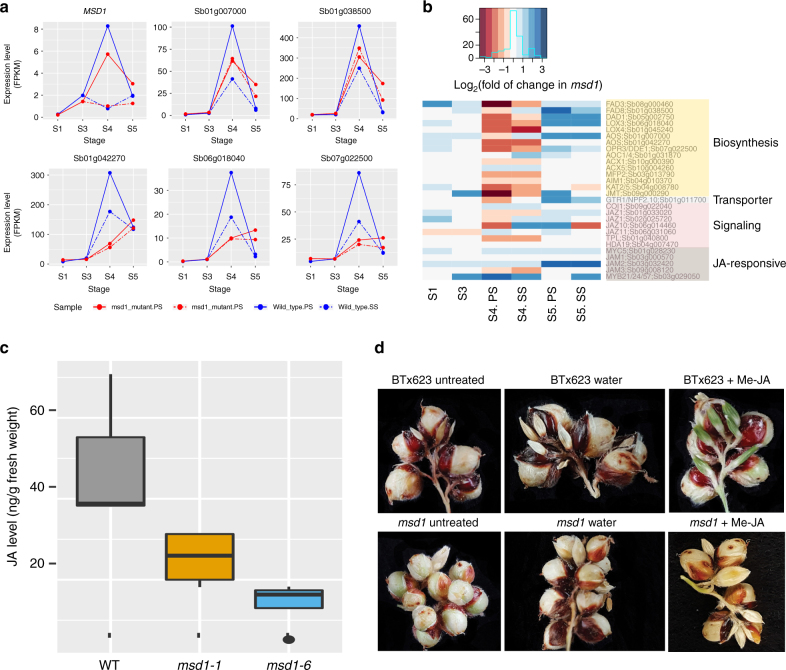

To interrogate the regulatory targets of MSD1, we performed transcriptome profiling by RNA-seq on developing panicles from four developmental stages of WT and msd1-1 with three biological replicates (Supplementary Table 2). After discarding two replicates (R2 < 0.9 relative to another replicate), the average Pearson correlation coefficient of the three biological replicates of each developmental stage was 0.97, indicating that the remaining samples were of high quality (Supplementary Fig. 6a). The MSD1 genotypes were also validated in the transcriptome profiling of both WT and mutant (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Among the 26,654 expressed genes in WT, 11,528 exhibited dynamic changes during panicle development. In WT, more genes were differentially expressed between SS and PS in stage 4 than in stage 5 (1848 versus 97). The number of the genes most differentially expressed between WT and msd1 was also at stage 4 (Supplementary Table 3). The upregulated genes in msd1 vs. WT at stage 4 in PS (Supplementary Table 4,5) were mainly involved in grain development, indicating that the floral development was set in stage 4.

Based on the expression pattern of MSD1 (Fig. 4a) and a study of the CYC pathway in Antirrhinum25, we established predicted expression patterns for putative regulatory targets of MSD1. Because MSD1 expression peaked at stage 4 in PS, MSD1 may act as a suppressor that inhibits the development of this organ. Therefore, we reasoned as follows: (1) Because the target genes are mainly required at stage 4 to determine the fate of PS, their expression should peak at S4 in PS in WT plants; (2) because MSD1 suppresses the development of PS in WT but not in msd1, the target genes should be expressed at higher levels in PS than in SS in WT, but their expression levels in PS should be greatly reduced in msd1; and (3) because both PS and SS developed into grains in the mutant, the target genes should be expressed at similar levels in PS and SS during stage 4 in msd1. A total of 167 genes with this pattern were identified as candidate regulatory targets. Based on Gene Ontology (GO) term analysis, genes involved in JA biosynthesis and metabolism were significantly enriched in this set (Table 1). Five putative regulatory targets involved in JA biosynthesis exhibited a pattern consistent with MSD1 targets (Fig. 4a). Among the other orthologs of the Arabidopsis JA pathway, only genes involved in biosynthesis were downregulated at stage 4 in PS of msd1 (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

MSD1 regulates the JA pathway and exogenous Me-JA rescues the msd1 phenotype. a Expression pattern of MSD1 and five putative target genes identified in the RNA-seq analysis that are involved in jasmonic acid (JA) biosynthesis (as determined by orthologs of Arabidopsis thaliana JA pathway). The blue lines depict pattern of expression in WT, whereas red lines represent expression in the msd1-1 mutant. At stages 4 and 5, solid and dotted lines indicate PS and SS, respectively. The expression level of MSD1 clearly differed between SS and PS in stage 4 in WT. MSD1 was differentially expressed between WT and msd1 only at stage 4 in PS. For the five putative target genes, the two red lines almost overlap with each other, indicating that in the msd1 mutant, the expression levels of these three genes were similar in PS and SS. b Heatmap of fold change in expression of sorghum orthologs of the Arabidopsis JA pathway genes in msd1 mutants. Genes involved in biosynthesis were downregulated at stage 4 in PS of msd1. c Box plot showing JA concentrations from five young panicle samples from each of two msd1 mutants and WT (BTx623). Lines from bottom to top represent minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum; dots indicate outliers. JA levels were lower in the two mutants than in WT. d Photograph of adaxial side of a secondary branch of inflorescence during exogenous JA treatment of WT and msd1-1 plants. The msd1-1 mutant reverted to the WT phenotype following treatment with methyl jasmonate (Me-JA)

Table 1.

The 20 most enriched biological process GO terms among putative target genes

| GO term | Description | No. in candidate targets | No. in background | P-valuea | FDRa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0031408 | Oxylipin biosynthetic process | 9 | 66 | 6.60E-10 | 2.60E-07 |

| GO:0031407 | Oxylipin metabolic process | 9 | 66 | 6.60E-10 | 2.60E-07 |

| GO:0006633 | Fatty acid biosynthetic process | 12 | 255 | 7.40E-08 | 1.90E-05 |

| GO:0009694 | Jasmonic acid metabolic process | 7 | 61 | 1.60E-07 | 2.60E-05 |

| GO:0009695 | Jasmonic acid biosynthetic process | 7 | 61 | 1.60E-07 | 2.60E-05 |

| GO:0015979 | Photosynthesis | 11 | 250 | 5.00E-07 | 6.50E-05 |

| GO:0006629 | Lipid metabolic process | 25 | 1351 | 6.00E-07 | 6.70E-05 |

| GO:0006631 | Fatty acid metabolic process | 13 | 387 | 8.60E-07 | 8.40E-05 |

| GO:0019684 | Photosynthesis, light reaction | 8 | 144 | 3.70E-06 | 0.00032 |

| GO:0009765 | Photosynthesis, light harvesting | 5 | 45 | 1.20E-05 | 0.00093 |

| GO:0016053 | Organic acid biosynthetic process | 13 | 637 | 0.00014 | 0.0094 |

| GO:0046394 | Carboxylic acid biosynthetic process | 13 | 637 | 0.00014 | 0.0094 |

| GO:0009617 | Response to bacterium | 10 | 405 | 0.0002 | 0.011 |

| GO:0032787 | Monocarboxylic acid metabolic process | 13 | 661 | 0.00021 | 0.011 |

| GO:0009753 | Response to jasmonic acid stimulus | 9 | 362 | 0.0004 | 0.021 |

| GO:0009698 | Phenylpropanoid metabolic process | 10 | 454 | 0.00048 | 0.023 |

| GO:0042742 | Defense response to bacterium | 7 | 261 | 0.0011 | 0.05 |

| GO:0008610 | Lipid biosynthetic process | 12 | 694 | 0.0011 | 0.05 |

| GO:0009628 | Response to abiotic stimulus | 27 | 2423 | 0.0013 | 0.052 |

| GO:0055114 | Oxidation reduction | 8 | 352 | 0.0015 | 0.057 |

aThe enrichment was calculated by Hypergeometric test. Multi-test adjustment was performed by Yekutieli (FDR under dependency) method

To determine whether JA levels were regulated by MSD1, we measured the changes in JA levels in developing panicles of WT (BTx623), msd1-1, and msd1-6. In stage 3 panicles, JA levels were reduced by >50% relative to WT in both mutants (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, the msd phenotype could be rescued by exogenous application of 1 mM methyl-JA to the whorl of msd1 mutants starting at stage 3 or earlier (Fig. 4d). However, no rescue occurred if methyl-JA was applied after stage 4. We also noted that prolonged methyl-JA treatments at concentrations >1 mM decreased overall panicle size and branching in comparison with controls.

Discussion

Spikelets are specialized units of the diverse inflorescence (flower) architectures of grasses8. Spikelets are classified into two types based on their mode of attachment to the inflorescence branch: SSs are directly attached, while PSs are attached through a short petiole called the pedicel. SS are also referred to as ‘central’, and PS as ‘lateral’, in some grass species33, 34. In general, only SS can produce fertile flowers and grains, whereas PS develop either staminate floral organs or no floral organ at all8, 10, 35. In this study, our characterization of the sorghum msd1 mutants, which bear fertile PS, reveals that suppression of floral organ development is regulated by the TCP transcription factor MSD1 via activation of JA biosynthesis. As described below, this suppression may be mediated through JA-induced programmed cell death.

The TCP-domain proteins are a family of plant-specific transcription factors that shape plant form and architecture26. MSD1 belongs to the CYC/TB1 sub-group of class II TCP-domain proteins. The founding gene of this sub-group, Cyc, was originally isolated from Antirrhinum as a regulator of flower asymmetry25. In WT Antirrhinum, Cyc is expressed at the dorsal (adaxial) side of the apical meristem during sepal primordia initiation and inhibits formation of the sepal, petal, and stamen. The WT flower has five sepals, five petals, four stamens, and one aborted stamen (called the staminode) on the dorsal side. By contrast, in cyc mutants, suppression of initiation and growth of flower organs is abolished, and consequently the staminode on the dorsal side becomes a fully developed stamen. In addition, a new stamen on the dorsal side initiates and fully develops. Thus, the cyc flower has six sepals, six petals, and six stamens. Cyc is also expressed on the dorsal side of the Antirrhinum flower during the late stage of development, altering its symmetry. Another well-studied member of the TCP/TB1 sub-group is the maize Tb1 gene. Similar to CYC in Antirrhinum, which suppresses the initiation and development of flower organs on the dorsal side, TB1 controls apical dominance by inhibiting development of basal tillers23. Its rice ortholog (Os03G0706500) also functions as a suppressor of tiller development36. The sorghum ortholog of maize Tb1 is Sb01g010690 (SbTCP2) and is induced by high planting density and far-red light enrichment, which reduces tiller development37. Therefore, it is likely that SbTCP2 also mediates tiller development. However, phylogenetic analysis indicates that MSD1 is not the ortholog of Tb1, and no functional study of its orthologs has been conducted in other grass species (Supplementary Fig. 7). Here we showed that, in sorghum, MSD1 regulates fertility of PS rather than vegetative tiller.

The inflorescence of barley has a very different architecture than that of sorghum: it has a single indeterminate main inflorescence axis that produces three single-flowered spikelets in a distichous manner at each rachis internode33. In the ancestral two-row barley, each central fertile spikelet is accompanied by two lateral aborted spikelets, whereas in six-row barley, the two lateral spikelets are fertile. To date, five genes have been identified that contribute to the conversion of two-row to six-row barley33, 34, 38–40. One of them, VRS5/INT-C, is the barley homolog of maize Tb1 and modifies lateral spikelet development in certain vrs1 allele backgrounds39. Both INT-C and MSD1 belong to the CYC/TB1 subgroup of class II TCP domain proteins, although INT-C is more closely related to the sorghum TB1 ortholog Sb01g010690 (SbTCP2) than to MSD1 (SbTCP16). Our whole-genome sequencing of 17 independent msd mutants revealed no large-effect mutations in the sorghum homologs of the other barley VRS genes, indicating the pathways that control row number in barley and inflorescence branching and fertility of PSs in sorghum may recruit specific components in each species39.

It remains unknown how TCP transcription factors regulate diverse features of plant architecture. Schommer et al. (2008) showed that a group of TCP transcription factors regulate early-stage leaf morphogenesis and leaf senescence through activation of JA biosynthesis enzymes in Arabidopsis41. Similarly, our results demonstrate that MSD1 also arrests the development of PS through activation of JA biosynthesis enzymes (Fig. 4). Based on our results, we devised a regulatory model of how MSD1 represses the development of PS in WT panicles. According to this model, a development signal during stage 3 may activate the expression of MSD1 in PS, leading to an increase in JA production. At stage 4, elevated JA level triggers a programmed cell death that leads to the arrest of further floral organ development, and eventually abortion of these tissues, in PS42, 43; this idea is supported by our transcriptome profiling (Supplementary Fig. 8). Consistent with the arrest of PS in WT, the top 10 most upregulated genes in the PS of msd1-1 vs WT PS at stage 4 are members of the late embryogenesis abundant protein44, 45 and cupin families46, indicating that embryo development in WT PS essentially ceases (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. 8). This hypothesis is also consistent with the sex-determination function of tassel seed 1 (Ts1) on the fate of tassel spikelet in maize20; Ts1 encodes a plastid-targeted 13-lipooxygenase that catalyzes the first committed step in JA biosynthesis. Maize tassel spikelets are staminate because the pistil primordia abort due to TS1-mediated programmed cell death. Recent work showed that vrs2, a six-row barley mutant, exhibits a phenotype analogous to those of msd mutants in sorghum that may be regulated by the hormone balance of auxin, GA, and cytokinin38. Because the JA level was not monitored in the barley studies, it remains to be determined whether sorghum and barley regulate the suppression of spikelet development through the same or different mechanisms.

In summary, we revealed a mechanism by which GNP is dramatically increased by de-repression of PS development in sorghum panicles. Specifically, we showed that mutation in the TCP transcription factor MSD1 blocks JA signaling, which suppresses organ formation in PS and its development into a perfect flower, possibly by inducing programmed cell death. Reduction of the JA level in developing panicles may also increase branch number and size during panicle development, thereby greatly increasing the overall panicle size under non-limiting environmental conditions19. Given the widespread presence of TCP transcription factors in crop plants, these findings suggest a novel approach for increasing grain number in cereal crops.

Methods

Imaging of inflorescence structures in WT and mutant

Inflorescence tissues at five stages (from meristem to immature spikelets) were collected from greenhouse-grown plants and processed for scanning electron microscopy47. To visualize the floral organs in SS and PS, SS and PS were collected from BTx623 and the msd1-1 mutant at stage 4 and cleared by fixing in FAA (50% ethanol, 1% formaldehyde, and 0.5% acetic acid) overnight at 4 °C. Fixed PS and SS samples were washed with an ethanol series (50, 70, 85, and 100% for at least 30 min each) and then dehydrated in 100% ethanol for 1 h. Fixed tissues were immersed in 1:1 methyl salicylate:ethanol solution for 1 h, transferred to 100% methyl salicylate solution, and soaked for an additional 1 h. For Nomarski microscopy, slides were sealed with Vaseline to keep the samples immersed in methyl salicylate solution. PS and SS organs were observed under Nomarski optics on a Leica DMRB microscope equipped with a QImaging Micropublisher 5.0 RTV.

Identification of the causal gene by bulk sequencing

The msd1-1 mutant was backcrossed to WT (BTx623) in a greenhouse. The WT, 17 independent msd mutants, and backcrossed F2 seeds from the msd1-1 backcross were planted in the USDA-ARS field in Lubbock, TX. During the late grain-filling stage, 50 plants with the mutant phenotype were selected from the backcrossed F2 plants. Leaf samples were collected and used to prepare genomic DNA with a CTAB method followed by purification with MagAttract beads48. Genomic DNA was pooled in equal amounts from the 50 individual F2 mutants and diluted to 100 ng/µl. Pooled F2 genomic DNA, as well as genomic DNA from BTx623 and 17 independent homozygous msd mutants, was sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq2000.

Low-quality reads, adaptor sequences, and contamination were excluded from the raw reads. The remaining clean reads were aligned to the sorghum reference genome v1.4 using Bowtie249. Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) calling was performed with Samtools and Bcftools, using only reads with mapping and sequencing quality >2050. The read depth for true SNPs was set from 3 to 50 for the parental line BTx623 and individual msd mutants and from 5 to 100 for the msd1-1 F2 population. SNPs from the F2 population and 17 mutants were analyzed using Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor51. Because EMS induces only G/C→A/T transition mutations52, only homozygous G/C→A/T were included in this analysis. SNPs from BTx623 were treated as background noise and filtered from all mutants and the F2 population.

To confirm mutations in the candidate genes, primers were designed using Primer3 (www.frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/input.htm). Genomic DNA from WT and each of the msd mutants was amplified using Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). All PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) before use as templates for sequencing. Subsequently, nested sequencing primers that encompassed the predicted SNPs were designed and used for fluorescent Sanger sequencing on an ABI Genetic Analyzer 3130 XL (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). To verify mutations, DNA sequences were assembled and analyzed using the DNAman software (Lynnon, San Ramon, CA, USA) at the chromatogram level.

To further confirm the causal SNPs identified by this approach, candidate genes were genotyped in 48 F2 individuals from the RTx437×msd1-1 cross using a rapid genotyping method, Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR (KASP) by Design (KBioscience/LGC Genomics [www.lgcgenomics.com]), using the manufacturer’s protocols with some modifications. Briefly, the touchdown PCR for the msd1 primers was from 65 to 57 °C, and the actual PCR was performed for 30 cycles at an annealing temperature of 57 °C. Because the msd phenotype was scored as a binary trait, the SNP–trait relationship was analyzed using Fisher’s exact test.

In situ hybridization

RNA in situ hybridization was conducted according to a published protocol with slight modifications53, 54. Inflorescence meristem and shoot apical meristem were dissected under a microscope and fixed under vacuum (400 mm Hg) for 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde containing 20% Tween-20. Shoot apical meristem was collected 3 weeks after germination, and IM was collected at various developmental times based on size and morphology. The ~500-bp MSD1 transcript was amplified from BTx623 cDNA and ligated into StrataClone PCR Cloning Kit vector pSC-A-amp/kan (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). T7 and T3 RNA polymerases were used for MSD1 in vitro transcription and hybridization. MSD1 transcripts were detected using ~500-bp digoxigenin-labeled MSD1 antisense or sense probe; the latter served as a negative control. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 6.

Localization of MSD1 in tobacco

The MSD1 gene (without a stop codon) was subcloned into pdnor221 using BP Clonase and ligated into the destination vector pMDC83. pMDC83 harboring the 35S promoter and MSD1 C-terminally fused to GFP was generated using LR Clonase. pMDC83-MSD1 was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. The transformed Agrobacterium were cultured at 28 °C for 2 days in YEP liquid (5 g NaCl, 10 g Bacto peptone, 10 g yeast extract) supplemented with rifampicin (60 mg/ml), kanamycin (50 mg/ml), gentamycin (50 mg/ml), and hygromycin (40 mg/ml). The Agrobacterium were then precipitated, re-suspended in infiltration buffer (2-ethanesulfonic acid, pH 5.5, 10 mM MgSO4) containing 10 µM acetosyringone, and used to inoculate the abaxial epidermal side of 3–4-week-old Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Two days after infiltration, leaves were observed for GFP and NLS-RFP fluorescence signal on a confocal microscope (ZEISS 710).

Expression analysis

For real-time qRT-PCR, total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) from root, shoot apical meristem, leaf, petiole, stage 1 IM, stage 3 IM, PS, and SS at stages 4 and 5. RNA samples were treated with DNase according to the Ambion Turbo DNA-free Kit protocol (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). cDNA was synthesized from 400 ng RNA using the Superscript III First Strand Synthesis Kit (Life Technologies), and an MSD1-specific primer was designed to amplify a 200–300 bp region of the transcript. Control primers were designed against Sb-Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 4 α(Sb-EIF4α). All real-time PCR analyses were performed on a C1000 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Primers were tested on WT (BTx623) by quantitative PCR on a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real Time System to confirm primer quality, as determined by melting curve and amplification efficiency. Gene expression in each sample was measured in three technical replicates. Primer sequences used for qRT-PCR are provided in Supplementary Table 6.

Transcriptome profiling

For RNA-seq analysis, panicle development was separated into different stages according to size, as described in the Results section. Three replicates (10 plants each) at each stage of development were used for tissue collection. Briefly, at panicle initiation stage 1, whole panicles were harvested from 10 plants, pooled together for each replicate, and processed for extraction of total RNA. In transition stage 3, the differentiated floral organs on the tips of panicles (one-third of the length) were harvested from 10 plants, pooled together for each replicate, and processed for extraction of total RNA. Sessile and pedicellate tissues could be separated at stages 4 and 5 using a dissecting microscope, and these tissues were harvested accordingly for each from 10 plants and pooled for each replicate. Tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C prior to RNA extraction.

RNA was extracted from 48 samples using TRIzol reagent, and total RNA for each sample was further subjected to DNase treatment and purification using the RNeasy Mini Clean-up Kit (Qiagen). The quality of total RNA was examined on 1% agarose gels and using RNA Nanochips on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Samples with RNA integrity number55 ≥7.0 were used for library preparation. Total RNA (2 μg) was used for poly (A)+ selection using oligo (dT) magnetic beads (Invitrogen 610-02), eluted in 11 µl of water, and used for RNA-seq library construction with the ScriptSeq™ v2 kit (Epicentre SSV21124). Final libraries were amplified by 13 PCR cycles. RNA-seq of three biological replicates was carried out in the sequencing center of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

RNA-seq data from each sample was first aligned to the sorghum version 1.4 reference genome using STAR56. Quantification of gene expression levels in each biological replicate was performed using Cufflinks57. The correlation coefficient among the three biological replicates for each sample was evaluated by the Pearson test in the R statistical environment. After removal of two bad samples, the biological replicates were merged together for differential expression analysis using Cuffdiff57. Only genes with at least five reads supported in at least sample were subjected to differential expression analysis. The cutoff for differential expression was adjusted False Discovery Rate p < 0.05. GO term analysis was performed with agriGO58 Singular Enrichment Analysis using the hypergeometric statistical test method, with significance level set to 0.01.

JA quantification

Five samples of young panicle (0.2–0.9 cm) were collected from WT BTx623 and two msd1 mutants for JA quantification. Samples were solvent-extracted, methylated, collected on a polymeric adsorbent using vapor-phase extraction, and analyzed using gas chromatography/isobutane chemical ion mass spectrometry59. For metabolite quantification, d5-JA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used as an internal standard. The JA level in each sample was normalized to the weight of the panicle and is expressed as 'ng/g fresh weight'.

Phenotypic rescue of msd1 with exogenous methyl-jasmonate

BTx623 or msd1 mutant seeds were germinated and grown in 2-gallon pots with four seedlings/pot for 16-h day cycles at 24 °C in a greenhouse. Beginning at leaf collar stage 7, 1 mL of either 0.05% Tween-20 (polyethylene glycol sorbitan monolaurate) in water (control) or 0.5 mM, 1.0 mM, or 5 mM methyl-jasmonate in 0.05% Tween-20 was aspirated directly down the floral whorl using a pipette. This treatment was repeated every 48 h until the majority of control plants reached the flag leaf stage. At this point, all experimental treatments were halted . All plants were allowed to mature to at least the soft dough stage prior to evaluation of whether successful rescue had occurred. Panicles were analyzed from the soft dough through black-layer stages to account for any delay in development or seed-filling that might have occurred as a result of methyl-JA treatment. Based on preliminary results, methyl-JA concentrations of 1 mM were optimal; higher concentrations severely retarded growth and development of the plant and resulted in significantly smaller panicles than in plants subjected to lower concentrations of methyl-JA.

Data availability

The BSA sequencing and RNA-seq data have been deposited to NCBI SRA under accession number SRP127741.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Y.J., R.C., G.B., J.B., C.H. and Z.X. acknowledge support from the United Sorghum Checkoff program. Z.X. was also partly supported by USDA ARS 3096-21000-019-00-D. Y.J., Y.K.L., N.G., M.R. and D.W. were partly supported by USDA ARS 8062-21000-041-00D; Y.K.L. acknowledges support from Brain Pool Program funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT through the National Research Foundation of Korea (2018H1D3A2002524); N.G. was supported by an ARS-funded postdoc fellowship.

Author contributions

Z.X. and D.W. conceived the study; Z.X. and G.B. isolated the mutants; R.C. and G.B. conducted genetic and co-segregation analyses of the mutations in MSD1 with multi-seededness; Y.J. identified the MSD1 gene and did the expression analysis; Y.K.L. conducted the inflorescence development analysis and MSD1 gene characterization; R.C., Y.K.L. and G.B. performed sampling of stage specific tissues for RNA-seq library; R.C. prepared the RNA samples for library construction; M.R. and Y.K.L. constructed the library for RNA-seq; N.G. and Y.K.L performed JA rescue experiments; S.A.C. analyzed JA levels; and R.C., G.B., C.H., and J.B. participated in the characterization of the mutants. Y.J., Y.K.L. and Z.X. drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in the revision and agree with the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Yinping Jiao and Young Koung Lee contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-03238-4.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Doreen Ware, Email: Doreen.Ware@ARS.USDA.GOV.

Zhanguo Xin, Email: Zhanguo.Xin@ARS.USDA.GOV.

References

- 1.Sreenivasulu N, Schnurbusch T. A genetic playground for enhancing grain number in cereals. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richards RA. Selectable traits to increase crop photosynthesis and yield of grain crops. J. Exp. Bot. 2000;51(Spec No):447–458. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.suppl_1.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swigonova Z, et al. Close split of sorghum and maize genome progenitors. Genome Res. 2004;14:1916–1923. doi: 10.1101/gr.2332504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes TE, Langdale JA, Kelly S. The impact of widespread regulatory neofunctionalization on homeolog gene evolution following whole-genome duplication in maize. Genome Res. 2014;24:1348–1355. doi: 10.1101/gr.172684.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paterson AH, et al. The Sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature. 2009;457:551–556. doi: 10.1038/nature07723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiao Y, et al. Improved maize reference genome with single-molecule technologies. Nature. 2017;546:524–527. doi: 10.1038/nature22971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyles, R. E. et al. Genome-wide association studies of grain yield components in diverse sorghum germplasm. Plant Genome9 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bommert P, Satoh-Nagasawa N, Jackson D, Hirano HY. Genetics and evolution of inflorescence and flower development in grasses. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;46:69–78. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown PJ, et al. Inheritance of inflorescence architecture in sorghum. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006;113:931–942. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0352-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burow G, Xin Z, Hayes C, Burke J. Characterization of a multiseeded () mutant of sorghum for increasing grain yield. Crop Sci. 2014;54:2030–2037. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2013.08.0566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahlberg, J. A. in Sorghum: Origin, History, Technology, and Production (eds Smith, C. A. & Frederiksen, R. A.) 99–130 (John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2000).

- 12.Wasternack C, Hause B. Jasmonates: biosynthesis, perception, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. An update to the 2007 review in Annals of Botany. Ann. Bot. 2013;111:1021–1058. doi: 10.1093/aob/mct067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan Z, Zhang D. Roles of jasmonate signalling in plant inflorescence and flower development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015;27:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li C, et al. The tomato suppressor of prosystemin-mediated responses2 gene encodes a fatty acid desaturase required for the biosynthesis of jasmonic acid and the production of a systemic wound signal for defense gene expression. Plant Cell Online. 2003;15:1646–1661. doi: 10.1105/tpc.012237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyons R, Manners JM, Kazan K. Jasmonate biosynthesis and signaling in monocots: a comparative overview. Plant Cell Rep. 2013;32:815–827. doi: 10.1007/s00299-013-1400-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Browse J. The power of mutants for investigating jasmonate biosynthesis and signaling. Phytochemistry. 2009;70:1539–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goetz S, et al. Role of cis-12-oxo-phytodienoic acid in tomato embryo development. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:1715–1727. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.192658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L, et al. The tomato homolog of CORONATINE-INSENSITIVE1 is required for the maternal control of seed maturation, jasmonate-signaled defense responses, and glandular trichome development. Plant Cell. 2004;16:126–143. doi: 10.1105/tpc.017954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cai Q, et al. Jasmonic acid regulates spikelet development in rice. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3476. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acosta IF, et al. tasselseed1 is a lipoxygenase affecting jasmonic acid signaling in sex determination of maize. Science. 2009;323:262–265. doi: 10.1126/science.1164645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeLong A, Calderon-Urrea A, Dellaporta SL. Sex determination gene TASSELSEED2 of maize encodes a short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase required for stage-specific floral organ abortion. Cell. 1993;74:757–768. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90522-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan Y, et al. Disruption of OPR7 and OPR8 reveals the versatile functions of jasmonic acid in maize development and defense. Plant Cell. 2012;24:1420–1436. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.094151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doebley J, Stec A, Hubbard L. The evolution of apical dominance in maize. Nature. 1997;386:485–488. doi: 10.1038/386485a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosugi S, Ohashi Y. PCF1 and PCF2 specifically bind to cis elements in the rice proliferating cell nuclear antigen gene. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1607–1619. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.9.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo D, Carpenter R, Vincent C, Copsey L, Coen E. Origin of floral asymmetry in Antirrhinum. Nature. 1996;383:794–799. doi: 10.1038/383794a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manassero NGU, Viola IL, Welchen E, Gonzalez DH. TCP transcription factors: architectures of plant form. Biomol. Concepts. 2013;4:111–127. doi: 10.1515/bmc-2012-0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin-Trillo M, Cubas P. TCP genes: a family snapshot ten years later. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Francis A, et al. Comparative phylogenomic analysis provides insights into TCP gene functions in Sorghum. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:38488. doi: 10.1038/srep38488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiao Y, et al. A sorghum mutant resource as an efficient platform for gene discovery in grasses. Plant Cell. 2016;28:1551–1562. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris GP, et al. Population genomic and genome-wide association studies of agroclimatic traits in sorghum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:453–458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215985110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mace ES, et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals untapped genetic potential in Africa’s indigenous cereal crop sorghum. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2320. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yazawa T, Kawahigashi H, Matsumoto T, Mizuno H. Simultaneous transcriptome analysis of Sorghum and Bipolaris sorghicola by using RNA-seq in combination with de novo transcriptome assembly. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koppolu R, et al. Six-rowedspike4 (Vrs4) controls spikelet determinacy and row-type in barley. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:13198–13203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221950110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Komatsuda T, et al. Six-rowed barley originated from a mutation in a homeodomain-leucine zipper I-class homeobox gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:1424–1429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608580104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kellogg EA. Floral displays: genetic control of grass inflorescences. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007;10:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeda T, et al. The OsTB1 gene negatively regulates lateral branching in rice. Plant J. 2003;33:513–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kebrom TH, Burson BL, Finlayson SA. Phytochrome B represses Teosinte Branched1 expression and induces sorghum axillary bud outgrowth in response to light signals. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:1109–1117. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.074856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Youssef HM, et al. VRS2 regulates hormone-mediated inflorescence patterning in barley. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:157–161. doi: 10.1038/ng.3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramsay L, et al. INTERMEDIUM-C, a modifier of lateral spikelet fertility in barley, is an ortholog of the maize domestication gene TEOSINTE BRANCHED 1. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:169–172. doi: 10.1038/ng.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bull H, et al. Barley SIX-ROWED SPIKE3 encodes a putative Jumonji C-type H3K9me2/me3 demethylase that represses lateral spikelet fertility. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:936. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00940-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schommer C, et al. Control of jasmonate biosynthesis and senescence by miR319 targets. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koch JR, et al. Ozone sensitivity in hybrid poplar correlates with insensitivity to both salicylic acid and jasmonic acid. The role of programmed cell death in lesion formation. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:487–496. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.2.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reinbothe C, Springer A, Samol I, Reinbothe S. Plant oxylipins: role of jasmonic acid during programmed cell death, defence and leaf senescence. FEBS J. 2009;276:4666–4681. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hundertmark M, Hincha DK. LEA (late embryogenesis abundant) proteins and their encoding genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manfre AJ, Lanni LM, Marcotte WR., Jr. The Arabidopsis group 1 LATE EMBRYOGENESIS ABUNDANT protein ATEM6 is required for normal seed development. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:140–149. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.072967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gábrišová D, et al. Do cupins have a function beyond being seed storage proteins? Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:1215. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duchrow M, Hasemeyer S, Broll R, Bruch HP, Windhovel U. Assessment of proliferative activity in colorectal carcinomas by quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) Cancer Invest. 2001;19:588–596. doi: 10.1081/CNV-100104286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xin Z, Chen J. A high throughput DNA extraction method with high yield and quality. Plant Methods. 2012;8:26. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McLaren W, et al. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP effect predictor. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2069–2070. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greene EA, et al. Spectrum of chemically induced mutations from a large-scale reverse-genetic screen in Arabidopsis. Genetics. 2003;164:731–740. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.2.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coen ES, et al. Floricaula: a homeotic gene required for flower development in antirrhinum majus. Cell. 1990;63:1311–1322. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90426-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jackson D, Veit B, Hake S. Expression of maize KNOTTED1 related homeobox genes in the shoot apical meristem predicts patterns of morphogenesis in the vegetative shoot. Development. 1994;120:405–413. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Szklarczyk D, et al. STRINGv10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D447–D452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dobin A, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trapnell C, et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Du Z, Zhou X, Ling Y, Zhang Z, Su Z. agriGO: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W64–W70. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmelz EA, Engelberth J, Tumlinson JH, Block A, Alborn HT. The use of vapor phase extraction in metabolic profiling of phytohormones and other metabolites. Plant J. 2004;39:790–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The BSA sequencing and RNA-seq data have been deposited to NCBI SRA under accession number SRP127741.