ABSTRACT

Seneca Valley virus (SVV), like some other members of the Picornaviridae, forms naturally occurring empty capsids, known as procapsids. Procapsids have the same antigenicity as full virions, so they present an interesting possibility for the formation of stable virus-like particles. Interestingly, although SVV is a livestock pathogen, it has also been found to preferentially infect tumor cells and is being explored for use as a therapeutic agent in the treatment of small-cell lung cancers. Here we used cryo-electron microscopy to investigate the procapsid structure and describe the transition of capsid protein VP0 to the cleaved forms of VP4 and VP2. We show that the SVV receptor binds the procapsid, as evidence of its native antigenicity. In comparing the procapsid structure to that of the full virion, we also show that a cage of RNA serves to stabilize the inside surface of the virus, thereby making it more acid stable.

IMPORTANCE Viruses are extensively studied to help us understand infection and disease. One of the by-products of some virus infections are the naturally occurring empty virus capsids (containing no genome), termed procapsids, whose function remains unclear. Here we investigate the structure and formation of the procapsids of Seneca Valley virus, to better understand how they form, what causes them to form, how they behave, and how we can make use of them. One potential benefit of this work is the modification of the procapsid to develop it for targeted in vivo delivery of therapeutics or to make a stable vaccine against SVV, which could be of great interest to the agricultural industry.

KEYWORDS: Seneca Valley virus, cryo-electron microscopy, picornavirus, procapsid

INTRODUCTION

Oncolytic virotherapy uses replication-competent viruses for fighting tumors. A number of viruses that specifically infect and kill cancer cells, while leaving the surrounding tissue unharmed, are currently in diverse stages of clinical trials (1). Seneca Valley virus (SVV) is a newly emerged picornavirus with potent antitumor activity (2). Several studies have shown that SVV is capable of specifically infecting and lysing cancer cells with neuroendocrine features (2–4). This treatment method has a number of advantages: the virus can be systemically administered, it is capable of penetrating solid tumors, preexisting antibodies against SVV are rare, and both pediatric and adult early-phase clinical trials have proven its safety (2, 5–8). Recently, we identified the anthrax toxin receptor 1 (ANTXR1) to be the high-affinity receptor for SVV in cancer cells (9). This presents a unique example of a receptor shared between a mammalian virus and a bacterial toxin. From a therapeutic perspective, ANTXR1 constitutes a highly specific biomarker for the identification of potential patients for SVV virotherapy. ANTXR1, also known as tumor endothelial marker 8, has been found to be overexpressed in 60% of human cancers (9) and less expressed in healthy tissues (10). Currently, there is widespread interest in finding therapeutic agents to target ANTXR1 (11–13). Understanding the formation and stability of the viral capsid would open the way to developing SVV as a viable treatment against cancer, either as an oncolytic agent or by constructing virus-like particles (VLPs) for targeted in vivo drug delivery.

Phylogenetic analysis indicates the existence of 3 clades of the virus (14). Clade I contains the strain SVV-001, which was originally developed for cancer treatment. Clades II and III contain strains first identified in Brazil, Canada, China, and the United States and are associated with swine vesicular diseases (14, 15). The association of SVV with these types of symptoms in livestock is rather new, and there are still unanswered questions regarding the causality between the viral infection and vesicular disease. Nevertheless, this association raises concerns due to its similarity with that seen in other major swine diseases. Given the possibility that SVV infection could pose a serious problem for the farming industry, there would be a need for constructing a vaccine against the virus, and VLPs could serve as useful candidates.

SVV is the sole member of the Senecavirus genus in the Picornaviridae family, and it shows the closest sequence similarity with cardioviruses (16, 17). Its 7,280-nucleotide-long genome is translated into a single polyprotein, which is subsequently cleaved into 12 polypeptides in the standard picornavirus L-4-3-4 arrangement (17). It has been shown for many picornaviruses that the assembly pathway involves the initial formation of pentamers from structural proteins VP0, VP1, and VP3, which further self-assemble into full capsids, a process that can be associated with a further cleavage of VP0 into VP2 and VP4. As a result, 60 copies of each of the four structural proteins form an icosahedral capsid with the typical picornavirus architecture. Five copies of VP1 are circularly distributed around the 5-fold axis, while VP2 and VP3 alternate around the 3-fold axis. The three major capsid proteins, VP1, VP2, and VP3, have a similar jelly roll fold with 8 β-strands arranged in a barrel-like structure. VP4 is a smaller, less well ordered protein that is located in the interior of the capsid, under the 5-fold axis.

Despite more than 200 picornavirus structures having been solved either by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) or X-ray crystallography (http://viperdb.scripps.edu), there is still little known about the capsid assembly pathway. The existence of empty capsids resembling the full virion has been reported for several picornaviruses. For members of the Enterovirus family, the presence of a late-entry intermediate empty capsid with a sedimentation coefficient of 80S is well documented as a final stage of the genome uncoating process (18). More puzzling is the presence of a procapsid, having a sedimentation coefficient of 75S, observed in enteroviruses (19–23), hepatoviruses (24), and aphthoviruses (25). Several roles have been proposed: as a strategy for the storage of pentamers to be used later for full virion assembly, as a way of deterring the recognition by neutralizing antibodies, as a procapsid in which the RNA will be further packaged, or as a simple dead-end during viral assembly. In all the studied cases, the procapsid is less stable, which hinders its use as a VLP for vaccine development or as a nanocarrier for drug delivery.

The existence of procapsids for members of other genera of the Picornaviridae is elusive, since they are far less abundant and very unstable (26). Procapsids have been reported for several enteroviruses, such as poliovirus (PV) (19), rhinovirus (22), enterovirus 71 (EV71) (21), and coxsackieviruses (20, 23), as well as for foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) (27) and hepatitis A virus (HAV) (24). No empty particles of any type have been reported for cardioviruses, the closest structural relatives to senecavirus.

Here we used cryo-EM in combination with other techniques to study the role of the SVV procapsid. The exterior of the SVV full capsid and procapsid appeared identical. Most of the differences occurred on the inside of the capsid, where the N-terminal end of VP1 is disordered in the procapsid but becomes ordered in the full virion when in contact with the viral RNA. Unlike the majority of picornaviruses, most copies of VP0 were cleaved in both the procapsid and the full capsid of SVV. Variations in pH affected the stability of both the procapsid and the full virion. Interestingly, in the full virion, part of the genome appeared ordered into a large dodecahedral cage. In addition, we showed that ANTXR1, the cellular receptor of SVV, was able to bind both the full virion and the procapsid.

RESULTS

SVV procapsid purification and characterization.

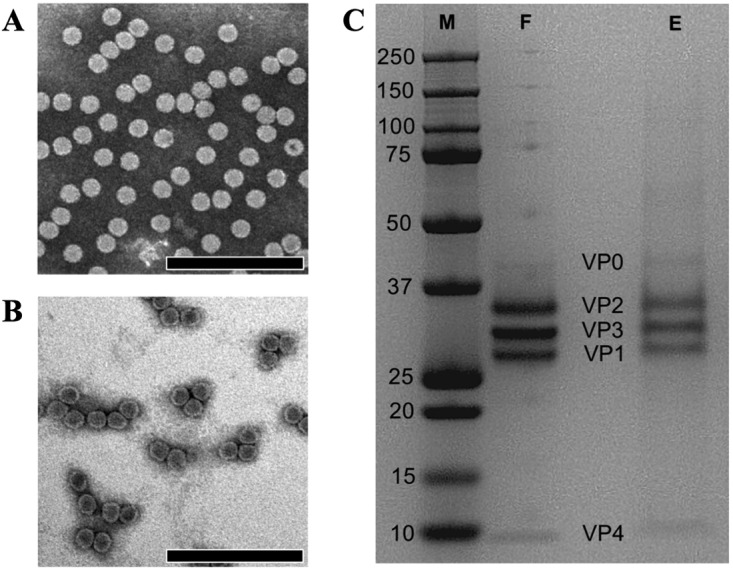

Both full capsids and naturally occurring procapsids of SVV were observed by electron microscopy, with procapsids representing 10 to 20% of the total number of particles, depending on the preparation. SVV purification in a linear 10 to 50% (wt/vol) potassium tartrate gradient resulted in two distinct bands, namely, a light sedimentation band and a heavy sedimentation band. Transmission electron micrographs of these fractions highlighted the presence of homogeneous populations of procapsids and full capsids, respectively (Fig. 1A and B). The purification of SVV using sucrose gradients yielded unsatisfactory results. Additionally, cryo-EM studies were hampered by high sucrose concentrations; therefore, additional purification steps were required.

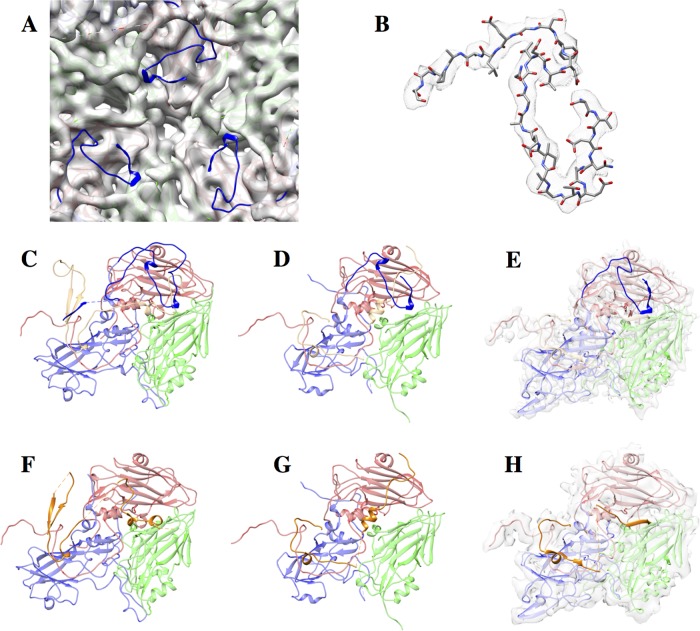

FIG 1.

Purification and characterization of SVV procapsids. (A) A negatively stained electron micrograph of the heavy sedimentation fraction collected from a 10 to 50% potassium tartrate gradient demonstrates the presence of full capsids. (B) A negatively stained electron micrograph of light sedimentation fraction depicts a homogeneous population of SVV empty capsids, as evident by the stain inside. Electron micrographs were recorded at a magnification of ×33,000 on a Phillips CM100 TEM operating at 100 kV. Bars, 200 nm. (C) SDS-PAGE analysis of full and procapsid fractions shows the cleavage in VP0 (∼43 kDa) to VP2 (∼36 kDa) and VP4 (∼7 kDa) in procapsids (lane E), similar to that in full capsids (lane F). The VP1 (27 kDa) and VP3 (31 kDa) bands were observed in both fractions. Lane M, molecular mass markers, with the numbers on the left indicating the molecular mass of each band (in kilodaltons).

To further confirm the purity of each fraction, full and procapsid stocks were titrated using plaque formation assays (PFA) on H446wt monolayers. H446wt cells are wild-type small-cell lung cancer cells which have previously been used for SVV infection studies as well as virus production and purification (9). Our PFA showed a 104-fold difference in the number of infectious virus particles between the procapsids and the full virions, highlighting the relative homogeneity of the separated fractions. We further validated this finding by measuring the total protein content in order to establish the particle/PFU ratios in the respective fractions. Similar to other picornaviruses, such as PV, the SVV full capsid fraction accounts for a particle/PFU ratio of 7.1 × 102. As expected, this value increased to 2.4 × 106 in the procapsid fraction due to the relative absence of infectious particles.

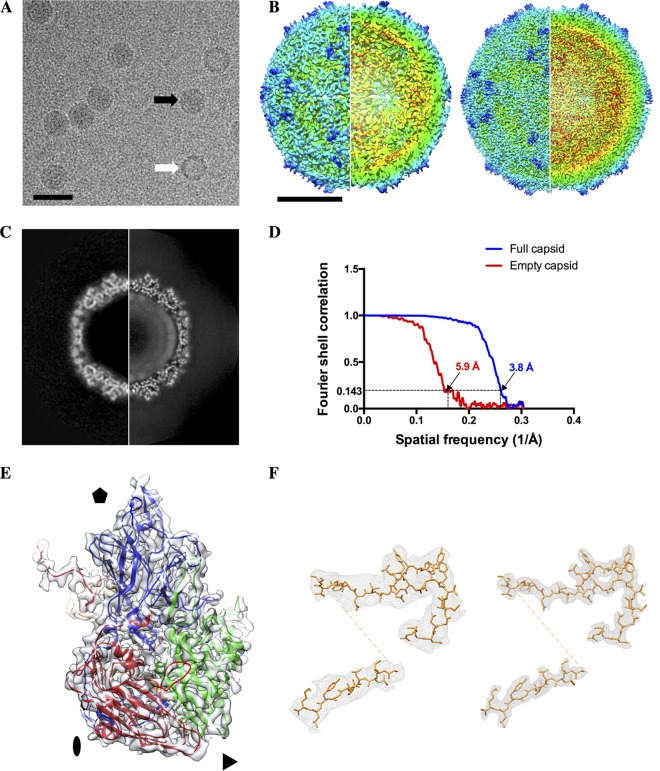

Structure of SVV capsid and procapsid.

We used cryo-EM to solve the structure of the full capsid and procapsid to resolutions of 3.8 Å and 5.9 Å, respectively (Fig. 2). The two structures are largely similar, with the obvious exception being the missing genomic RNA in the procapsid (Fig. 2C). The procapsid is not expanded, and its external surface appears identical to the full particles at this resolution and, correspondingly, also displays the same antigenicity as the full virion. The atomic model, derived from X-ray crystallography (PDB accession number 3CJI) (16), was fitted into the cryo-EM density without alteration and with excellent agreement (Fig. 2E).

FIG 2.

Cryo-EM of SVV full capsid and procapsid. (A) A representative micrograph showing procapsids (white arrow) and mature virions (black arrow). Bar, 50 nm. (B) Outside and cutaway views of the procapsid (left) and full virion (right). Bar, 10 nm. (C) A central slice through the procapsid (left) and the full virion (right). Note the ordered RNA closest to the capsid in the full virion. (D) The Fourier shell correlation curves for gold standard reconstructions of the procapsid and full virion. (E) The X-ray model of SVV agrees well with the cryo-EM map of the SVV capsid. Blue, VP1; green, VP2; red, VP3; orange, VP4. (F) VP4 adopts the same conformation in the procapsid (left) and full virion (right), although the virion is clearly better resolved than the procapsid.

Procapsid binds ANTXR1.

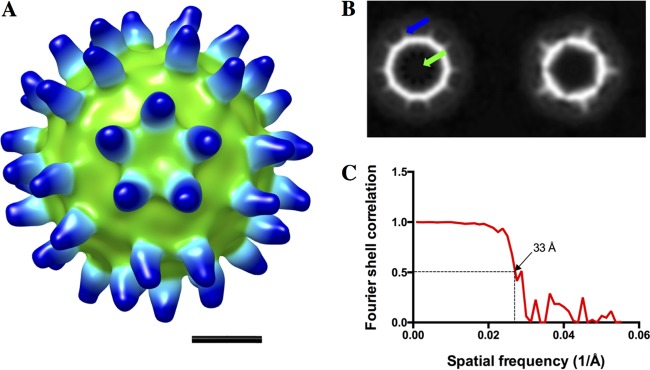

The fact that the full capsid and the procapsid have identical external surfaces (Fig. 2B) suggested that the SVV procapsid would also be able to bind the cellular receptor. In the case of poliovirus, it has been shown that receptor binding triggered partial conformational changes associated with viral entry (28). We incubated the soluble domain of ANTXR1 with purified capsid and collected a small cryo-EM data set of the empty capsid decorated particles. Despite its modest resolution, the calculated map clearly displayed the crown-like arrangement of receptors around the 5-fold axis, as shown for the full capsid (9), confirming the procapsid affinity for ANTXR1 (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

SVV procapsids bind the ANTXR1. (A) The cryo-EM reconstruction of SVV procapsid-ANTXR1 demonstrates the full decoration of ANTXR1 on the capsid surface, similar to that of the virion-ANTXR1complex. Bar, 10 nm. (B) Central sections through the procapsid-ANTXR1 EM map are devoid of any central density corresponding to viral RNA (green arrow) and show bound ANTXR1 on the capsid surface (blue arrow). (C) The resolution of the density map was assessed to be 33 Å, according to a Fourier shell cutoff of 0.5.

VP0 is cleaved in the procapsid.

The next objective in our study was to determine whether the procapsids isolated during SVV purification are actual procapsids (73S) or empty capsid intermediates formed after the RNA release (80S). In general, picornavirus procapsids are a product of 14S pentameric assembly prior to RNA encapsidation. Thus, the picornavirus procapsid protein composition is mainly composed of uncleaved, myristoylated VP0, VP1, and VP3. However, the VP0 (∼43 kDa) in SVV empty capsids was found to be cleaved into VP2 (∼36 kDa) and VP4 (∼7 kDa), with a relatively small amount of VP0 being left intact (Fig. 1C). Similarly, the protein composition of the mature virion was found to consist of VP1 (27 kDa), VP2, VP3 (∼31 kDa), and VP4, as is characteristic for picornaviruses (Fig. 1C). The band corresponding to VP0 in the virion fraction could be due to the presence of minute amounts of procapsids (with uncleaved VP0). The observation that VP4 still remains in place within the empty capsids confirms that they are procapsids and not empty capsids resulting from RNA release. The mechanisms governing the cleavage of VP0 to VP2 and VP4 in procapsids are still unclear. Nonetheless, it is thought to occur as a result of an autocatalytic process responsible for the cleavage of VP0 in provirions (27, 29) or perhaps by the activity of aberrantly encapsidated 3C protease (27). Previous studies on type A FMDV procapsids have highlighted the cleavage of VP0 to VP2 and VP4 (27). A histidine residue required for cleavage in PV (H195 of VP2) (29), also found in FMDV (H145 of VP2) (27), is positioned identically in SVV (H204 of VP2), suggesting a similar role in autocleavage (Fig. 4). Furthermore, this apparently unusual cleavage of VP0 in procapsids may be a time-dependent event, as reported with the type A FMDV empty capsids (27), thus resulting in a mixture of protomers with uncleaved VP0 and protomers with the cleavage products, VP2 and VP4. However, it is apparent that a bulk proportion of VP0 in SVV procapsids have undergone cleavage, as indicated by a faint VP0 band and stronger VP2 and VP4 bands (Fig. 1C).

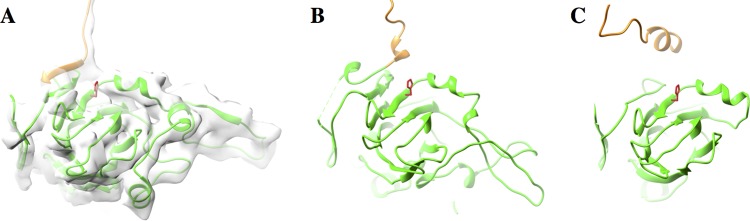

FIG 4.

VP0 cleavage site in picornaviruses. (A) The position of H204 from SVV is analogous to that of its conserved counterparts H145 from the PV procapsid (PDB accession number 1POV) (B) and H195 from an FMDV procapsid (PDB accession number 4IV1) (C). Only VP4 (yellow) and VP2 (green) are shown; the SVV procapsid map is shown semitransparently in panel A.

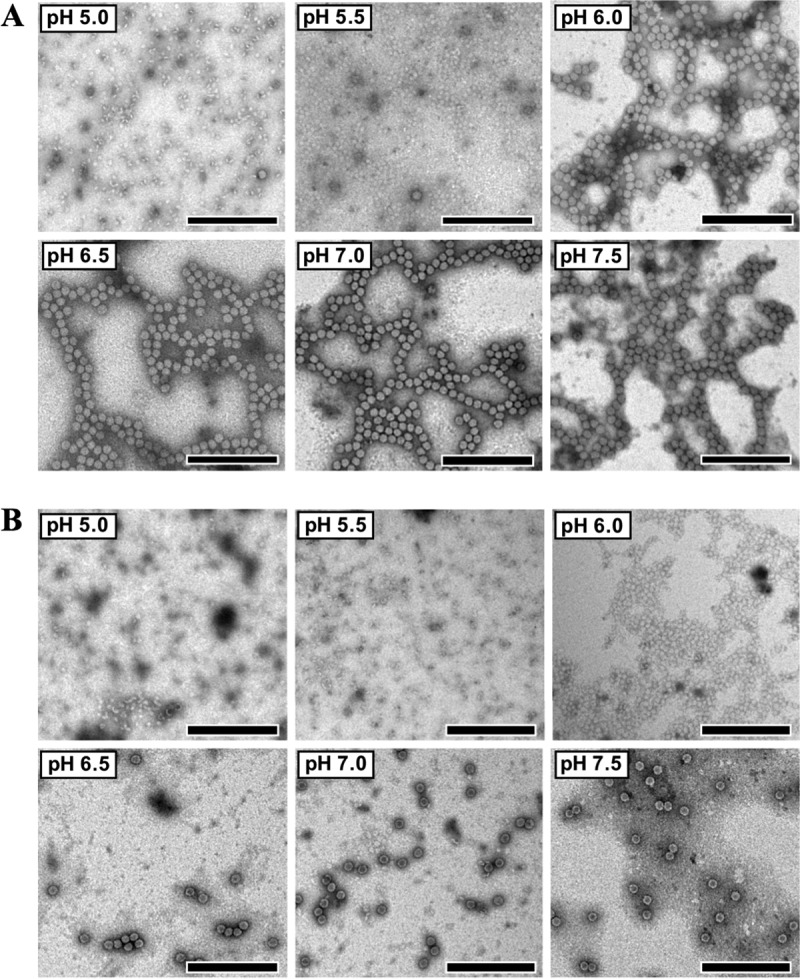

Acid lability of SVV virions and procapsids.

The capsids of picornaviruses act as a protective shell for the encapsidated RNA genome until a suitable host environment is encountered for virus uncoating. Therefore, understanding the environmental factors to which the virus is receptive can provide valuable insights into its biology and potential mechanisms of infection. From a therapeutic perspective, such information is of importance in designing inactivated vaccines and stable VLP preparations.

We carried out pH stability experiments in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH values of between 5.0 and 7.5 with 0.5 pH unit increments. Negative-stain transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images showed that SVV virions disassemble into pentameric subunits at pH values of ≤5.5 (Fig. 5A), whereas this was observed at pH values of ≤6.0 (Fig. 5B) with procapsids. These results suggest that SVV virions are more resistant to acidic conditions than procapsids. However, this result is somewhat contradictory to the acid stability of FMDV virions, which has been shown to be inferior to that of FMDV procapsids. Full capsids of FMDV A serotypes have been shown to dissociate at slightly below neutrality, with pH50 values, defined as the pH where 50% of infectivity is measurable, ranging from 6.0 to 6.65, whereas the natural empty capsid demonstrated pH50 values of 6.0 to 6.35 (30). Investigations into the FMDV infection pathway have shown the necessity of such acid lability, since full capsids undergo disassembly in the increasingly acidic environment of early endosomes. On the other hand, human rhinovirus strain A2 virions uncoat in late endosomal compartments, requiring a higher acid stability (31). Therefore, it can be speculated that SVV disassembly may be a process that is strictly dependent on low-acidic-pH environments in late endosomal compartments. Since SVV virions differ from empty capsids due to the presence of RNA, the increased pH stability of SVV virions could be governed by the interactions between the RNA genome and capsid proteins.

FIG 5.

pH stability of SVV full capsids and procapsids. (A) Electron micrographs of purified virions, diluted in phosphate-buffered saline at pHs ranging from 5.0 to 7.5 and incubated for 30 min at room temperature, show that the capsid disassembles into pentamers at pHs of ≤5.5. (B) Procapsids were found to be more acid labile, with capsid disassembly into pentamers being observed at pHs of ≤6.0. Bars, 200 nm.

Procapsid dissociation into pentamers.

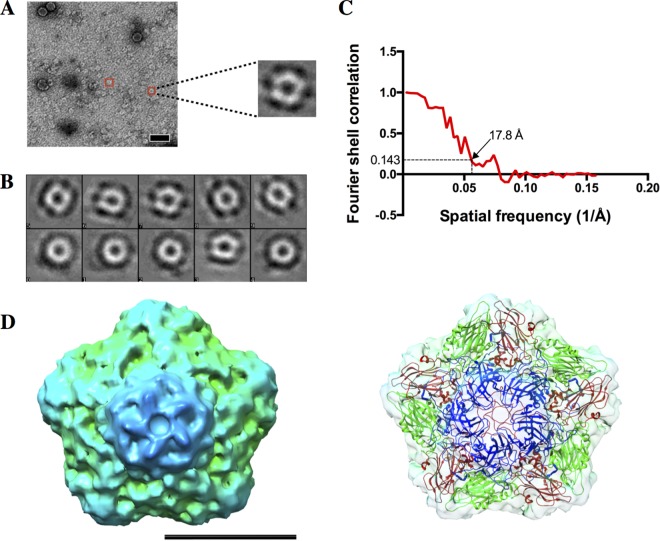

We characterized the morphology of pentameric populations observed in procapsids at pH 6.0 by using negative-stain electron microscopy (EM) single-particle reconstruction (Fig. 6). Class averages showed a 5-fold symmetry characteristic of that of picornaviruses (Fig. 6B). A three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of the pentamer from this study adequately highlighted the 5-fold symmetry of the structure as well as a depression at the center of the pentamer (Fig. 6D). Fitting of the atomic model of the pentamer into the EM map demonstrated a good correlation between the two components, hence validating the low-resolution 3D model (Fig. 6D).

FIG 6.

Negative-stain single-particle reconstruction of procapsid pentamers. (A) An electron micrograph of negatively stained procapsids at pH 6.0 shows that most of the procapsids appeared to be disassembled into pentamers (red boxes) at this pH. Bar, 50 nm. (B) Class averages of particles picked from 36 micrographs were obtained using the EMAN2 image processing suite. These class averages demonstrated the presence of particles with 5-fold symmetry, thereby further validating the presence of pentamers. (C) The 3D reconstruction generated from good class averages had an estimated resolution of 17.8 Å, according to the gold standard Fourier shell correlation cutoff of 0.143. Bars, 10 nm. (D) Fitting of the crystal structure of SVV pentamer into the EM density map revealed a good correlation between the crystal structure and the EM map. Bar, 10 nm.

The VP1 N terminus becomes ordered in contact with the genome.

In SVV, the major differences between the interior of the full capsid and the procapsid were observed at the capsid floor. Consistent with the procapsid structures of other picornaviruses, peptides located at the internal surface were disordered (19, 21, 24, 27). The most obvious difference was on the N-terminal end of VP1, where the first 28 amino acids were disordered in the procapsid (Fig. 7). Nevertheless, while no density was visible for the first 14 amino acids, at a lower threshold there was visible density for the next 14 residues, which indicates the presence of a partially ordered conformation. The disordered and partially ordered parts of VP1 are strongly negatively charged and arrange themselves in clear patches at the interior of the full capsid in a manner reminiscent of that for enteroviruses (Fig. 8).

FIG 7.

Capsid interior. (A) Details of the SVV procapsid centered on a 3-fold axis. The atomic model of the mature virion is depicted in ribbons. The density, displayed semitransparently, accurately accommodates the model, except for the first 28 residues of VP1 (blue). (B) Masked density of the VP1 N terminus from the SVV full capsid is well ordered in comparison to SVV procapsids. (C to E) Interior views of full capsid protomers of PV (C), FMDV (D), and SVV (E) demonstrating the disordered N termini on their procapsid counterparts (dark blue). The PDB accession numbers of the full capsid protomers of PV, FMDV, and SVV are 1HXS, 4GH4, and 3CJI, respectively. VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4 are colored in light shades of blue, green, red, and orange, respectively. (F to H) Interior views of a single protomer of procapsids of PV (F), FMDV (G), and SVV (H) identifying cleaved VP0 in SVV and FMDV and intact VP0 in PV. The PDB accession numbers of the single protomer of procapsids of PV, FMDV, and SVV are 1POV, 4IH4, and 3CJI, respectively. VP1, VP2, and VP3 are colored in light shades of blue, green, and red, respectively; VP4 is colored in orange.

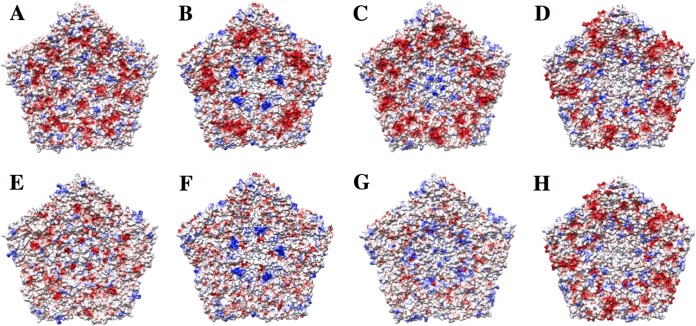

FIG 8.

Comparison of electrostatic surfaces of picornaviruses. The top row contains the electrostatic surfaces of full capsid pentamers of EV71 (PDB accession number 3VBS) (A), SVV (PDB accession number 3CJI) (B), PV (PDB accession number 2PLV) (C), and FMDV (PDB accession number 4GH4) (D). The bottom row contains the electrostatic surfaces of empty capsid pentamers of EV71 (PDB accession number 3VBU) (E), SVV (PDB accession number 3CJI) (F) PV (PDB accession number 1POV) (G), and FMDV (PDB accession number 4IV1) (H). In general, the empty capsids have fewer negatively charged patches. This is especially true of SVV and PV. Red, negative; blue, positive; white, neutral. The color scale runs from −10 to 10 kT/e.

The SVV genome is partially ordered inside the capsid.

A careful inspection of the interior of the full capsid map showed a large part of the genome being ordered. A partially ordered genome has been reported in other picornavirus or picorna-like virus structures (32–36). However, they were mostly represented by loops of genomic material forming contacts with capsid proteins. Cryo-EM studies of RNA bacteriophages, such as MS2 (37, 38) or Qβ (39), have shown that most of the genome is ordered inside the capsid.

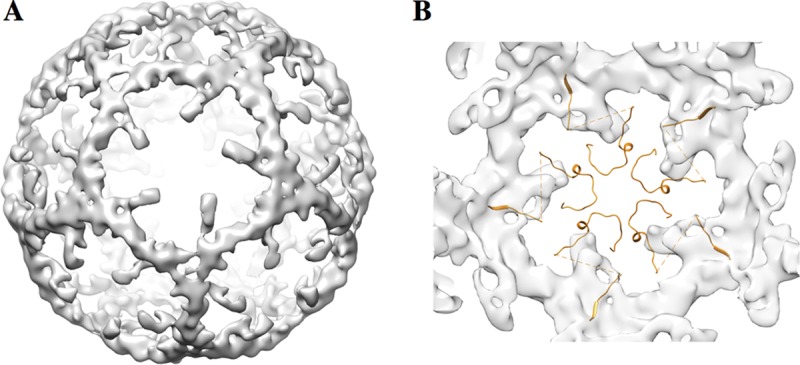

Our structure shows a large dodecahedral cage on the interior of the capsid, with densities sized to accommodate RNA helices (Fig. 9). The cage is not evident at 3.8 Å and becomes clear only at resolutions lower than ∼6 Å, as observed in the case of MS2 bacteriophage (38). This effect is probably due to the fact that the RNA chain is more flexible than the capsid proteins. Imposing icosahedral symmetry averages different regions of the genome into common secondary structural motifs visible only at a lower resolution. A similar RNA cage was reported for the nodaviruses (40, 41), suggesting a common strategy for viral RNA folding. Inside the pentagonal face of the cage, five small densities under the density corresponding to the VP4 protein were visible. These densities could accommodate part of the disordered residues of VP4 and RNA loops involved in the contact with the central part of VP4, which was partially disordered in both the full capsid and procapsid. Nevertheless, compared to other enteroviruses and aphthoviruses, the electrostatic potential of the interior of the SVV capsid showed that a highly positive region is present around the 5-fold axis (Fig. 8). These arrangements of positive residues at the interior of the capsid could be involved in binding viral RNA loops similarly to the Ljungan virus (35) and parechoviruses (34, 36).

FIG 9.

Ordered RNA structure inside the SVV mature capsid. The difference map between the full virion and the procapsid map, each filtered to 9 Å, shows that part of the genome is ordered. (A) An exterior view of the RNA cage, looking down the 5-fold axis. (B) View from the interior of the cage along the 5-fold axis. The VP4 proteins at the 5-fold axis form a star between the RNA densities.

DISCUSSION

For many picornaviruses, two types of particles are produced during infection: the native empty particles (procapsids) and full virions. The two populations are discernible using electron microscopic methods and can be purified by different methods of gradient density ultracentrifugation. In most cases, the two forms of the capsids have an identical external structure and share the same antigenic properties. Despite lacking the internal RNA, procapsids have the same protein composition as the native virions. In the case of enteroviruses, a different class of empty particles exists. Following a major conformational change which leads to an expansion of the capsid into the A particle (18), the genome is externalized (42, 43), leaving behind an altered empty capsid: the B particle (44). The B particle is antigenically different from the native virion and has a different protein composition. Altered empty capsids have been structurally characterized in detail for several enterovirus members, such as PV (44), rhinoviruses (45), enterovirus 71 (EV71) (46), coxsackieviruses (47), and equine rhinitis A virus (48), as well as for other picornaviruses, such as kobuviruses (49), or for picorna-like viruses, such as bee viruses (50, 51). In all these cases the structures show a capsid expanded by 4 to 6%, lacking VP4, and showing more disorder on the interior of the capsid. For enteroviruses, the expansion often leads to large holes at the 2-fold axes, supporting the idea of RNA exit at or near this site (42, 43, 52). The antigenic properties of the expanded empty particles are also distinct, as was shown for PV (53) and EV71 (54). However, the procapsids are much less well studied. Procapsid structures have been solved by cryo-EM or X-ray crystallography for enteroviruses, such as PV (19), EV71 (21), rhinovirus (22), and coxsackieviruses (20, 23). All these structures show an unexpanded capsid with an uncleaved VP0 arranged in a conformation different from that of the final configuration of VP2 and VP4 in the mature capsid. It was shown in several cases that VP0 cleavage is conditional on the presence of viral RNA (19). The cleavage of VP0 into VP4 and VP2 is a condition required for a successful infection in the case of enterovirus, where insertion of VP4 in the cellular membrane is necessary for RNA translocation (55). For other members of the picornavirus family, which rely on acidification to trigger the uncoating process, VP0 is never cleaved. This is the case for the procapsid structures of parechoviruses (35, 36) or kobuviruses (56). The case of aphthoviruses is somewhat different. For FMDV the VP0 cleavage gradually occurs, even in the absence of RNA, at room temperature over several weeks (27). This is not the case for SVV, where the VP0 cleavage occurs spontaneously. Similar to FMDV, the SVV procapsid seems to contain a low percentage of residual uncleaved VP0 (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, it has been shown that FMDV pentamers can reassociate into an empty capsid in an inside-out arrangement (57). This unnatural conformation would expose the VP4 region to the exterior of the capsid. The structures both of pentamers and of the inside-out empty capsid show no density corresponding to VP4, suggesting that VP4 is essential for the correct procapsid assembly. A different situation is observed in the case of EV71 (58) and coxsackieviruses (23), where VP0 is not cleaved in the procapsid and no density corresponding to the VP4 region is observed, indicating that this region is not ordered. A possible explanation could be that the cleavage of VP0 in the absence of the viral RNA would lead to the dissociation of VP4 from the capsid. In contrast, for SVV the partial attachment of the terminal VP4 β-strand to the VP2 β-barrel (Fig. 4 and 7) stabilizes the structure and enables the cleavage of VP0 and the assembly of the resulting VP2 and VP4 in a stable procapsid. This terminal β-strand of VP4 is specific for SVV, with all the other picornavirus structures showing a short α-helix in this region (Fig. 7).

Despite the similarities between SVV and FMDV, their response to exposure to an acid environment is different. While the procapsid of FMDV is more stable than the corresponding mature virion (59), the procapsid of SVV is less stable than the full capsid containing the RNA, suggesting a role of the genomic RNA in stabilizing the capsid. Much effort was put in increasing the stability of FMDV VLPs for use as a vaccine; it was shown that the stability of different serotypes could be increased by mutating residues at the interface of the protomers (25, 60). A similar effort for increasing the stability of SVV procapsids could benefit the construction of VLPs to be used as nanocarriers in cancer treatment or as vaccines against the animal pathogen serotypes.

The mechanism of VP0 cleavage was examined in detail in PV (29), and it was shown to involve a conserved histidine residue located in a pocket at the base of VP2 (Fig. 4). The cleavage implies that the residues corresponding to the VP4-VP2 connection would have to penetrate the pocket containing the conserved histidine to position the scissile bond sufficiently close. Our structure shows that in both the SVV mature capsid and the procapsid the conformations of VP2 and VP4 are in close proximity to the histidine residue at position 204 responsible for the cleavage. The C terminus of VP4 is fully ordered and stops on top of the H204 residue, while the first 11 residues of VP2 are disordered but would easily reach the first ordered residue. In comparison, in PV and FMDV procapsids the ordered part of VP4 covers a much larger part of the pocket, while in FMDV, VP4 is located farther away (Fig. 4). Overall, the position of VP4 in SVV more closely resembles that in PV than that in FMDV.

The length of the disordered N terminus of VP1 could also be responsible for the different behavior of VP0 cleavage in senecaviruses compared with that in enteroviruses and aphthoviruses. In the mature capsids of both FMDV and PV, the histidine pocket is covered by the N terminus of VP1, while in the procapsid, the same region is disordered and thus permits access to the pocket. A smaller flexible region occluding the pocket would lead to a more rapid cleavage of VP0. In the case of SVV, there are 14 fully disordered residues in the N-terminal part of VP1, whereas FMDV has 26 disordered residues and PV has 67 disordered residues (Fig. 7).

The structure of the SVV procapsid highlights several features of related viruses in a unique combination. These lead us to believe that SVV procapsids could prove to become useful tools as VLPs or as drug delivery mechanisms for targeting cancers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth and purification of SVV.

H446wt cells (ATCC, HTB-171) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM; catalog number 11995-073; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin to 80% to 90% confluence in at least 30 T150 flasks. On the day of inoculation, the growth medium was removed and the cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The PBS was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin containing SVV at a virus dose to allow approximately 25 SVV particles per cell using a virus clonal stock that had previously been plaque purified three times. After 2 days postinfection, most of the cells were detached in a single-cell suspension. The cell suspension was transferred to 500-ml Nalgene bottles and spun down at 10,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a clean Nalgene bottle and mixed at 4 parts supernatant to 1 part 10,000-molecular-weight (MW) polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution (100 g of 10,000-MW PEG from Sigma, 6 g NaCl, and 250 ml Millipore water, which were autoclaved and adjusted to pH 7.2 with 0.1 N NaOH). The PEG-containing supernatant was mixed overnight at 4°C to precipitate out the virus. On the following day, the pegylated supernatant was spun down at 10,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The virus-containing PEG precipitate pellet was reconstituted in PBS (5 ml) and dialyzed with an 80,000- to 100,000-molecular-weight-cutoff filter three times, with 1 liter PBS being replaced every 4 h. The dialyzed virus was placed onto a 1.33-g/ml CsCl gradient in a heat-sealed polyallomer tube (catalog number 342413; Beckman) and spun at 360,000 × g at 20°C for 7 to 8 h. The virus band was isolated by first puncturing a hole at the top of the tube and then using an 18-gauge needle to pull out the virus band from the side of the tube. The purified virus was dialyzed into PBS supplemented with magnesium and calcium (PBS++), which was replaced every 4 h for a total of 10 exchanges. The concentration was determined by calculating the optical density at 260 nm (OD260) and OD280. The ratio for OD260/OD280 should be between 1.6 and 1.7, and 1 OD unit with a 1-cm path length equals 9.5e12 virus particles. The aliquoted virus stocks were stored at −70°C.

To further achieve more purified and homogeneous fractions of SVV empty and full capsids, a mixed population of SVV empty and full capsids was subjected to a potassium tartrate linear gradient. Briefly, H446wt cells harvested from 16 T175 flasks were transferred into 250-ml Nalgene bottles and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C in a JA-20 rotor fitted to an Avanti J-26XPI high-speed centrifuge (Beckman Coulter). The supernatant was loaded into 38.5-ml open-top, polypropylene tubes (catalog number Z60105SCA; Beckman) and centrifuged at 86,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C in an SW32 Ti rotor fitted to an Optima XPN-80 ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter). The pellet was resuspended in potassium tartrate purification buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5). The resuspended virus pellet was loaded onto a 10 to 50% potassium tartrate linear gradient in a 16.5-ml open-top, polypropylene tube (catalog number Z60303SCA; Beckman) and subjected to a final round of ultracentrifugation at 105,000 × g for 2.5 h at 4°C in an SW32.1 Ti rotor. Two distinct fractions of virus (an upper band and a lower band) were pulled out from top to bottom using an 18-gauge needle and dialyzed overnight in PBS at 4°C.

Transmission electron microscopy.

Dialyzed virus bands were visualized under a transmission electron microscope according to in-house protocols. In brief, 4 μl of the sample was applied onto a glow-discharged, carbon grid for 1 min, and the excess sample was blotted off. The grids were stained with 1% uranyl acetate for 1 min, followed by blotting of excess stain, and were examined on a Philips CM100 transmission electron microscope (Philips Electron Optics, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) operating at 100 kV.

Negative-stain single-particle reconstruction of pentamers.

The procapsid sample at pH 6.0 from the previous section was used for further imaging and image reconstruction. Briefly, 36 micrographs were acquired at a ×40,000 (pixel size = 3.12 Å) magnification on a JEOL JEM-2200FS TEM (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) operating at 200 kV and equipped with a F416 CMOS camera (Tietz Video and Image Processing Systems, Gauting, Germany). The reconstruction of the pentameric unit was carried out with the EMAN2 package (version 2.1) (61). First, 9,112 particles were manually picked and subjected to contrast transfer function (CTF) correction. Thereafter, one round of reference-free two-dimensional (2D) classification was carried out with six iterations, and the bad classes were discarded. The initial reference-free 3D classification was performed, with selected good classes totaling 8,256 particles, and the resulting model was further refined for 10 iterations using pentameric symmetry. The resolution of the constructed EM map was estimated to be 17.8 Å on the basis of the “gold standard” Fourier shell correlation cutoff of 0.143. A model of the pentameric structure generated from the SVV crystal structure (PDB accession number 3CJI) was fitted in the Chimera program.

Cryo-EM of full capsid and procapsid.

Cryo-EM samples were prepared by adding 3.5 μl of purified SVV to Quantifoil R2/2 grids previously glow discharged for 8 s. These were then blotted with Whatman no. 5 filter paper before being plunged into liquid ethane using an FEI Vitrobot IV automated vitrification device at 100% humidity. The images were collected on an FEI Polara microscope equipped with a K2 Summit camera in superresolution mode with a final superresolution pixel size of 0.822 Å and at a total dose of 30 e/Å2 over 30 frames.

The frames were aligned by the use of driftcorr software (62), and CTF parameters were estimated with the ctffind program (63). The virus particles were selected using the Gautomatch (version 0.5) program (http://www.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/kzhang/Gautomatch/). The selected image particles were extracted and subjected to 2D and 3D classification using Relion (version 1.4) software (64), and after the removal of bad classes, the remaining particles were split into empty and full classes for refinement, imposing icosahedral symmetry. Each class was then additionally refined and sharpened using Relion (version 2.1-beta-1) software. The particles were separated into two half data sets for all of the subsequent reconstruction steps following the gold standard procedure. The additional refinement and sharpening with the more recent version of Relion software improved the resolution, marginally giving the final reported values of 5.9 Å for the procapsid and 3.8 Å for the virion (Fig. 2; Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Cryo-EM imaging and data processing statistics

| Characteristic | Value(s) |

|---|---|

| No. of micrographs used | 367 |

| No. of particles | |

| Full capsid | 20,949 |

| Empty capsid | 3,526 |

| Sampling (Å/pixel) | 0.822 (1.644)a |

| Defocus range (μm) | 1.5–5 |

| Resolution (Å)b | |

| Full capsid | 3.8 |

| Empty capsid | 5.9 |

The value in parentheses is the binned value.

Gold standard forward scatter = 0.143 criterion.

Cryo-EM procapsid-receptor complex.

SVV and ANTXR1 (catalog number 13367-H02H; Sino Biological Inc.) were mixed in a ratio of approximately 10:1 receptors per binding site, kept for 90 min at 37°C, and transferred onto ice for another 90 min. Grids were prepared by applying 3 μl of sample on glow-discharged Quantifoil holey carbon grids (Quantifoil Micro Tools GmbH) and flash-frozen using a Leica KF80 cryofixation device (C. Reichert Optische Werke AG). Micrographs were collected on a JEOL JEM-2200FS microscope (JEOL Ltd.) on a TVIPS F416 CMOS camera (TVIPS, Gauting, Germany) at a calibrated magnification of ×50,000, corresponding to a pixel size of 2.53 Å. A number of 214 images of empty capsid were selected, and a 3D reconstruction was computed using the icosahedral symmetry in Relion (version 1.4) software (64). The resolution was estimated to be 33 Å, according to a Fourier shell cutoff of 0.5.

Plaque formation assay.

The infectious virus titer in two virus fractions was determined by standard plaque formation assay. H446wt cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 70% confluence 1 day prior to infection. Serial dilutions of the upper band (10−3 to 10−7) and lower band (10−6 to 10−10) were prepared in R10 medium (RPMI 1640 medium [catalog number 31800-022; Gibco] supplemented with 0.01 M HEPES [catalog number 11344-041l; Gibco]) and 0.02 M sodium bicarbonate (catalog number 205-633-8; Applichem). Confluent monolayers of H446wt cells in duplicate wells were infected with 250 μl of each dilution and the R10 medium control for 1 h at 37°C. The plates were gently tilted every 15 min to ensure uniform adsorption. After 1 h, the virus suspension was removed from each well and the cells were immediately overlaid with 2 ml of R10 medium containing 2% FBS and 1% agarose (SeaPlaque; catalog number 50100; Lonza). The agarose was allowed to set at room temperature for 15 min, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h thereafter. Plaques were stained with 100 μl of 5 mg/ml 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; catalog number M2128; Sigma) per well. The plaques were counted after incubation of the plates at 37°C for 3 h under dark conditions.

Quantification of total protein in empty and full capsid fractions.

The total protein contents in two virus fractions were determined by using a Qubit protein assay kit (catalog number 1814929; Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 10-μl volumes of the sample were incubated with 190 μl of Qubit working solution (1:200 of Qubit reagent/Qubit buffer), and the reaction mixture was incubated under dark conditions at room temperature for 15 min. The same procedure was followed for Qubit protein standards 1, 2, and 3. The readings were recorded for duplicate samples from each fraction by using a Qubit (version 1.0) fluorometer (Life Technologies).

Structural protein analysis in SDS-PAGE.

Protein precipitation of two virus fractions was carried out using the trichloroacetic acid precipitation method. Protein denaturation for SDS-PAGE was performed according to the recommended NuPAGE specifications. Briefly, 15 μl of each protein sample (7 to 15 μg) was mixed with 5 μl of 4× LDS sample loading buffer (catalog number NP0007; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 500 mM dithiothreitol (catalog number SLBH1672V; Sigma), followed by heating at 90°C for 10 min. Then, 5 μl of a prestained Bio-Rad low-range protein ladder (catalog number 161-0305) and 20 μl of each sample were loaded onto a Novex Bolt 4 to 12% bis-Tris Plus gel. Electrophoresis was undertaken in a Bio-Rad PowerPac 200 instrument at a constant voltage of 80 V in 1× 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) running buffer until the dye front reached the end of the gel. The gel was stained by the 0.1% Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 (0.02%, wt/vol) colloidal staining method overnight and was destained in Milli-Q water for 12 h. The gel image was captured on a Uvidoc imaging system (Uvitec, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

pH stability of SVV empty and full capsids.

The acid sensitivity of empty capsids and full capsids was investigated according to methods adapted from published protocols (65). Each sample was mixed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solutions of different pHs (5 to 7.5) at a ratio of 1:10. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min and subsequently visualized by electron microscopy as described above.

Accession number(s).

Cryo-EM maps of the full virion and procapsid can be found in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb/) under accession numbers EMD-7110 and EMD-7111, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Vivienne Young for help with procapsid purification and Thomas Devine for help with image processing of the pentamer structure. Electron microscopy was performed at Harvard Medical School and the Otago Centre for Electron Microscopy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fountzilas C, Patel S, Mahalingam D. 2017. Review: oncolytic virotherapy, updates and future directions. Oncotarget 8:102617–102639. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddy PS, Burroughs KD, Hales LM, Ganesh S, Jones BH, Idamakanti N, Hay C, Li SS, Skele KL, Vasko AJ, Yang J, Watkins DN, Rudin CM, Hallenbeck PL. 2007. Seneca Valley virus, a systemically deliverable oncolytic picornavirus, and the treatment of neuroendocrine cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 99:1623–1633. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poirier JT, Dobromilskaya I, Moriarty WF, Peacock CD, Hann CL, Rudin CM. 2013. Selective tropism of Seneca Valley virus for variant subtype small cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 105:1059–1065. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morton CL, Houghton PJ, Kolb EA, Gorlick R, Reynolds CP, Kang MH, Maris JM, Keir ST, Wu J, Smith MA. 2010. Initial testing of the replication competent Seneca Valley virus (NTX-010) by the pediatric preclinical testing program. Pediatr Blood Cancer 55:295–303. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke MJ, Ahern C, Weigel BJ, Poirier JT, Rudin CM, Chen Y, Cripe TP, Bernhardt MB, Blaney SM. 2015. Phase I trial of Seneca Valley virus (NTX-010) in children with relapsed/refractory solid tumors: a report of the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62:743–750. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Z, Zhao X, Mao H, Baxter PA, Huang Y, Yu L, Wadhwa L, Su JM, Adesina A, Perlaky L, Hurwitz M, Idamakanti N, Police SR, Hallenbeck PL, Hurwitz RL, Lau CC, Chintagumpala M, Blaney SM, Li XN. 2013. Intravenous injection of oncolytic picornavirus SVV-001 prolongs animal survival in a panel of primary tumor-based orthotopic xenograft mouse models of pediatric glioma. Neuro Oncol 15:1173–1185. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudin CM, Poirier JT, Senzer NN, Stephenson J Jr, Loesch D, Burroughs KD, Reddy PS, Hann CL, Hallenbeck PL. 2011. Phase I clinical study of Seneca Valley virus (SVV-001), a replication-competent picornavirus, in advanced solid tumors with neuroendocrine features. Clin Cancer Res 17:888–895. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke M. 2016. Oncolytic Seneca Valley virus: past perspectives and future directions. Oncolytic Virother 5:81–89. doi: 10.2147/OV.S96915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miles LA, Burga LN, Gardner EE, Bostina M, Poirier JT, Rudin CM. 2017. Anthrax toxin receptor 1 is the cellular receptor for Seneca Valley virus. J Clin Invest 127:2957–2967. doi: 10.1172/JCI93472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies G, Rmali KA, Watkins G, Mansel RE, Mason MD, Jiang WG. 2006. Elevated levels of tumour endothelial marker-8 in human breast cancer and its clinical significance. Int J Oncol 29:1311–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pietrzyk L. 2016. Biomarkers discovery for colorectal cancer: a review on tumor endothelial markers as perspective candidates. Dis Markers 2016:4912405. doi: 10.1155/2016/4912405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao C, Wang Z, Huang L, Bai L, Wang Y, Liang Y, Dou C, Wang L. 2016. Down-regulation of tumor endothelial marker 8 suppresses cell proliferation mediated by ERK1/2 activity. Sci Rep 6:23419. doi: 10.1038/srep23419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Opoku-Darko M, Yuen C, Gratton K, Sampson E, Bathe OF. 2011. Tumor endothelial marker 8 overexpression in breast cancer cells enhances tumor growth and metastasis. Cancer Invest 29:676–682. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2011.626474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Segales J, Barcellos D, Alfieri A, Burrough E, Marthaler D. 2017. senecavirus A. Vet Pathol 54:11–21. doi: 10.1177/0300985816653990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu W, Hole K, Goolia M, Pickering B, Salo T, Lung O, Nfon C. 2017. Genome wide analysis of the evolution of senecavirus A from swine clinical material and assembly yard environmental samples. PLoS One 12:e0176964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Venkataraman S, Reddy SP, Loo J, Idamakanti N, Hallenbeck PL, Reddy VS. 2008. Structure of Seneca Valley virus-001: an oncolytic picornavirus representing a new genus. Structure 16:1555–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hales LM, Knowles NJ, Reddy PS, Xu L, Hay C, Hallenbeck PL. 2008. Complete genome sequence analysis of Seneca Valley virus-001, a novel oncolytic picornavirus. J Gen Virol 89:1265–1275. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy HC, Bostina M, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. 2010. Cell entry: a biochemical and structural perspective, p 87–104. In Ehrenfeld E, Domingo E, Roos RP (ed), The picornaviruses. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basavappa R, Syed R, Flore O, Icenogle JP, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. 1994. Role and mechanism of the maturation cleavage of VP0 in poliovirus assembly: structure of the empty capsid assembly intermediate at 2.9 Å resolution. Protein Sci 3:1651–1669. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ren J, Wang X, Zhu L, Hu Z, Gao Q, Yang P, Li X, Wang J, Shen X, Fry EE, Rao Z, Stuart DI. 2015. Structures of coxsackievirus A16 capsids with native antigenicity: implications for particle expansion, receptor binding, and immunogenicity. J Virol 89:10500–10511. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01102-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cifuente JO, Lee H, Yoder JD, Shingler KL, Carnegie MS, Yoder JL, Ashley RE, Makhov AM, Conway JF, Hafenstein S. 2013. Structures of the procapsid and mature virion of enterovirus 71 strain 1095. J Virol 87:7637–7645. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03519-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y, Hill MG, Klose T, Chen Z, Watters K, Bochkov YA, Jiang W, Palmenberg AC, Rossmann MG. 2016. Atomic structure of a rhinovirus C, a virus species linked to severe childhood asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:8997–9002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606595113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu L, Zheng Q, Li S, He M, Wu Y, Li Y, Zhu R, Yu H, Hong Q, Jiang J, Li Z, Li S, Zhao H, Yang L, Hou W, Wang W, Ye X, Zhang J, Baker TS, Cheng T, Zhou ZH, Yan X, Xia N. 2017. Atomic structures of coxsackievirus A6 and its complex with a neutralizing antibody. Nat Commun 8:505. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00477-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, Ren J, Gao Q, Hu Z, Sun Y, Li X, Rowlands DJ, Yin W, Wang J, Stuart DI, Rao Z, Fry EE. 2015. Hepatitis A virus and the origins of picornaviruses. Nature 517:85–88. doi: 10.1038/nature13806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porta C, Kotecha A, Burman A, Jackson T, Ren J, Loureiro S, Jones IM, Fry EE, Stuart DI, Charleston B. 2013. Rational engineering of recombinant picornavirus capsids to produce safe, protective vaccine antigen. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003255. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mullapudi E, Novacek J, Palkova L, Kulich P, Lindberg AM, van Kuppeveld FJ, Plevka P. 2016. Structure and genome release mechanism of the human cardiovirus Saffold virus 3. J Virol 90:7628–7639. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00746-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curry S, Fry E, Blakemore W, Abu-Ghazaleh R, Jackson T, King A, Lea S, Newman J, Stuart D. 1997. Dissecting the roles of VP0 cleavage and RNA packaging in picornavirus capsid stabilization: the structure of empty capsids of foot-and-mouth disease virus. J Virol 71:9743–9752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basavappa R, Gomez-Yafal A, Hogle JM. 1998. The poliovirus empty capsid specifically recognizes the poliovirus receptor and undergoes some, but not all, of the transitions associated with cell entry. J Virol 72:7551–7556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hindiyeh M, Li QH, Basavappa R, Hogle JM, Chow M. 1999. Poliovirus mutants at histidine 195 of VP2 do not cleave VP0 into VP2 and VP4. J Virol 73:9072–9079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maree FF, Blignaut B, de Beer TA, Rieder E. 2013. Analysis of SAT type foot-and-mouth disease virus capsid proteins and the identification of putative amino acid residues affecting virus stability. PLoS One 8:e61612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snyers L, Zwickl H, Blaas D. 2003. Human rhinovirus type 2 is internalized by clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J Virol 77:5360–5369. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5360-5369.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hesketh EL, Meshcheriakova Y, Dent KC, Saxena P, Thompson RF, Cockburn JJ, Lomonossoff GP, Ranson NA. 2015. Mechanisms of assembly and genome packaging in an RNA virus revealed by high-resolution cryo-EM. Nat Commun 6:10113. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shakeel S, Dykeman EC, White SJ, Ora A, Cockburn JJB, Butcher SJ, Stockley PG, Twarock R. 2017. Genomic RNA folding mediates assembly of human parechovirus. Nat Commun 8:5. doi: 10.1038/s41467-016-0011-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shakeel S, Westerhuis BM, Domanska A, Koning RI, Matadeen R, Koster AJ, Bakker AQ, Beaumont T, Wolthers KC, Butcher SJ. 2016. Multiple capsid-stabilizing interactions revealed in a high-resolution structure of an emerging picornavirus causing neonatal sepsis. Nat Commun 7:11387. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu L, Wang X, Ren J, Porta C, Wenham H, Ekstrom JO, Panjwani A, Knowles NJ, Kotecha A, Siebert CA, Lindberg AM, Fry EE, Rao Z, Tuthill TJ, Stuart DI. 2015. Structure of Ljungan virus provides insight into genome packaging of this picornavirus. Nat Commun 6:8316. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalynych S, Palkova L, Plevka P. 2015. The structure of human parechovirus 1 reveals an association of the RNA genome with the capsid. J Virol 90:1377–1386. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02346-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koning RI, Gomez-Blanco J, Akopjana I, Vargas J, Kazaks A, Tars K, Carazo JM, Koster AJ. 2016. Asymmetric cryo-EM reconstruction of phage MS2 reveals genome structure in situ. Nat Commun 7:12524. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dai X, Li Z, Lai M, Shu S, Du Y, Zhou ZH, Sun R. 2017. In situ structures of the genome and genome-delivery apparatus in a single-stranded RNA virus. Nature 541:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature20589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorzelnik KV, Cui Z, Reed CA, Jakana J, Young R, Zhang J. 2016. Asymmetric cryo-EM structure of the canonical allolevivirus Qbeta reveals a single maturation protein and the genomic ssRNA in situ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:11519–11524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609482113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang L, Johnson KN, Ball LA, Lin T, Yeager M, Johnson JE. 2001. The structure of Pariacoto virus reveals a dodecahedral cage of duplex RNA. Nat Struct Biol 8:77–83. doi: 10.1038/83089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ho KL, Kueh CL, Beh PL, Tan WS, Bhella D. 2017. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of the Macrobrachium rosenbergii nodavirus capsid at 7 angstroms resolution. Sci Rep 7:2083. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02292-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strauss M, Levy HC, Bostina M, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. 2013. RNA transfer from poliovirus 135S particles across membranes is mediated by long umbilical connectors. J Virol 87:3903–3914. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03209-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bostina M, Levy H, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. 2011. Poliovirus RNA is released from the capsid near a twofold symmetry axis. J Virol 85:776–783. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00531-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levy HC, Bostina M, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. 2010. Catching a virus in the act of RNA release: a novel poliovirus uncoating intermediate characterized by cryo-electron microscopy. J Virol 84:4426–4441. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02393-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garriga D, Pickl-Herk A, Luque D, Wruss J, Caston JR, Blaas D, Verdaguer N. 2012. Insights into minor group rhinovirus uncoating: the X-ray structure of the HRV2 empty capsid. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002473. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shingler KL, Yoder JL, Carnegie MS, Ashley RE, Makhov AM, Conway JF, Hafenstein S. 2013. The enterovirus 71 A-particle forms a gateway to allow genome release: a cryoEM study of picornavirus uncoating. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003240. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seitsonen JJ, Shakeel S, Susi P, Pandurangan AP, Sinkovits RS, Hyvonen H, Laurinmaki P, Yla-Pelto J, Topf M, Hyypia T, Butcher SJ. 2012. Structural analysis of coxsackievirus A7 reveals conformational changes associated with uncoating. J Virol 86:7207–7215. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06425-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tuthill TJ, Harlos K, Walter TS, Knowles NJ, Groppelli E, Rowlands DJ, Stuart DI, Fry EE. 2009. Equine rhinitis A virus and its low pH empty particle: clues towards an aphthovirus entry mechanism? PLoS Pathog 5:e1000620. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sabin C, Fuzik T, Skubnik K, Palkova L, Lindberg AM, Plevka P. 28 September 2016. Structure of Aichi virus 1 and its empty particle: clues towards kobuvirus genome release mechanism. J Virol. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01601-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kalynych S, Fuzik T, Pridal A, de Miranda J, Plevka P. 2017. Cryo-EM study of slow bee paralysis virus at low pH reveals iflavirus genome release mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:598–603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616562114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Organtini LJ, Shingler KL, Ashley RE, Capaldi EA, Durrani K, Dryden KA, Makhov AM, Conway JF, Pizzorno MC, Hafenstein S. 2017. Honey bee deformed wing virus structures reveal that conformational changes accompany genome release. J Virol 91:e01795-. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01795-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee H, Shingler KL, Organtini LJ, Ashley RE, Makhov AM, Conway JF, Hafenstein S. 2016. The novel asymmetric entry intermediate of a picornavirus captured with nanodiscs. Sci Adv 2:e1501929. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strauss M, Schotte L, Karunatilaka KS, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. 2017. Cryo-electron microscopy structures of expanded poliovirus with VHHs sample the conformational repertoire of the expanded state. J Virol 91:e01443-. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01443-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Plevka P, Lim PY, Perera R, Cardosa J, Suksatu A, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. 2014. Neutralizing antibodies can initiate genome release from human enterovirus 71. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:2134–2139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320624111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Panjwani A, Strauss M, Gold S, Wenham H, Jackson T, Chou JJ, Rowlands DJ, Stonehouse NJ, Hogle JM, Tuthill TJ. 2014. Capsid protein VP4 of human rhinovirus induces membrane permeability by the formation of a size-selective multimeric pore. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004294. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu L, Wang X, Ren J, Kotecha A, Walter TS, Yuan S, Yamashita T, Tuthill TJ, Fry EE, Rao Z, Stuart DI. 2016. Structure of human Aichi virus and implications for receptor binding. Nat Microbiol 1:16150. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malik N, Kotecha A, Gold S, Asfor A, Ren J, Huiskonen JT, Tuthill TJ, Fry EE, Stuart DI. 2017. Structures of foot and mouth disease virus pentamers: insight into capsid dissociation and unexpected pentamer reassociation. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006607. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang X, Peng W, Ren J, Hu Z, Xu J, Lou Z, Li X, Yin W, Shen X, Porta C, Walter TS, Evans G, Axford D, Owen R, Rowlands DJ, Wang J, Stuart DI, Fry EE, Rao Z. 2012. A sensor-adaptor mechanism for enterovirus uncoating from structures of EV71. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19:424–429. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Curry S, Abrams CC, Fry E, Crowther JC, Belsham GJ, Stuart DI, King AM. 1995. Viral RNA modulates the acid sensitivity of foot-and-mouth disease virus capsids. J Virol 69:430–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kotecha A, Seago J, Scott K, Burman A, Loureiro S, Ren J, Porta C, Ginn HM, Jackson T, Perez-Martin E, Siebert CA, Paul G, Huiskonen JT, Jones IM, Esnouf RM, Fry EE, Maree FF, Charleston B, Stuart DI. 2015. Structure-based energetics of protein interfaces guides foot-and-mouth disease virus vaccine design. Nat Struct Mol Biol 22:788–794. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tang G, Peng L, Baldwin PR, Mann DS, Jiang W, Rees I, Ludtke SJ. 2007. EMAN2: an extensible image processing suite for electron microscopy. J Struct Biol 157:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li X, Mooney P, Zheng S, Booth CR, Braunfeld MB, Gubbens S, Agard DA, Cheng Y. 2013. Electron counting and beam-induced motion correction enable near-atomic-resolution single-particle cryo-EM. Nat Methods 10:584–590. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mindell JA, Grigorieff N. 2003. Accurate determination of local defocus and specimen tilt in electron microscopy. J Struct Biol 142:334–347. doi: 10.1016/S1047-8477(03)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scheres SH. 2012. RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J Struct Biol 180:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Caridi F, Vazquez-Calvo A, Sobrino F, Martin-Acebes MA. 2015. The pH stability of foot-and-mouth disease virus particles is modulated by residues located at the pentameric interface and in the N terminus of VP1. J Virol 89:5633–5642. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03358-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]