Abstract

G protein βγ subunit (Gβγ) is a major signal transducer and controls processes ranging from cell migration to gene transcription. Despite having significant subtype heterogeneity and exhibiting diverse cell- and tissue-specific expression levels, Gβγ is often considered a unified signaling entity with a defined functionality. However, the molecular and mechanistic basis of Gβγ's signaling specificity is unknown. Here, we demonstrate that Gγ subunits, bearing the sole plasma membrane (PM)–anchoring motif, control the PM affinity of Gβγ and thereby differentially modulate Gβγ effector signaling in a Gγ-specific manner. Both Gβγ signaling activity and the migration rate of macrophages are strongly dependent on the PM affinity of Gγ. We also found that the type of C-terminal prenylation and five to six pre-CaaX motif residues at the PM-interacting region of Gγ control the PM affinity of Gβγ. We further show that the overall PM affinity of the Gβγ pool of a cell type is a strong predictor of its Gβγ signaling–activation efficacy. A kinetic model encompassing multiple Gγ types and parameterized for empirical Gβγ behaviors not only recapitulated experimentally observed signaling of Gβγ, but also suggested a Gγ-dependent, active–inactive conformational switch for the PM-bound Gβγ, regulating effector signaling. Overall, our results unveil crucial aspects of signaling and cell migration regulation by Gγ type–specific PM affinities of Gβγ.

Keywords: cell migration, cell signaling, G protein–coupled receptor, GPCR, G protein, macrophage, computational modeling, G protein βγ, opsin, optogenetics, signal transduction, chemotaxis, plasma membrane, fluorescence, imaging

Introduction

G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs)2 primarily transduce signals by activating G protein heterotrimers consisting of Gα and Gβγ subunits. Active G proteins GαGTP and Gβγ, interact, control a cohort of effectors, and regulate the majority of metazoan signaling (1–3). Although Gα signaling has been the primary focus in the field, recent findings show that Gβγ subunits also regulate crucial signaling pathways and cellular functions. Some of the Gβγ effectors include phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3Kγ), adenylyl cyclase (AC) isoforms (activation of AC2, 4, 7 and inhibition of AC1, 5), inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels, phospholipase C (PLC) isoforms (PLCβ2, β3), Ca2+ channels (N, P/Q type), GPCR kinases (GRKs), and guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) such as Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1), cell division control protein 42 (Cdc42), guanine nucleotide exchange factor (FLJ00018), and p114-RhoGEF (4–13). These effectors coordinate a wide range of cellular and physiological functions such as cellular secretion, gene transcription, contractility, and cell migration, and are therefore involved in numerous pathological conditions including cancer and heart disease (1–3).

Among Gβγ-controlled activities, chemokine GPCR activation–governed cell migration plays a key role in many physiological functions, including embryonic development and immune responses. Altered cell motilities are implicated in pathological processes such as immune deficiencies, lack of wound healing, tissue repair, and cancer metastasis (14–17). We have recently shown that Gβγ is a key regulator of inhibitory G protein (Gi)–coupled GPCR activation–induced macrophage migration (18). In addition to PI3K-PIP3 signaling at the leading edge, we demonstrated that Gβγ-mediated activation of PLCβ pathway is essential for macrophage migration.

Mammalian cells express 12 Gγ and 5 Gβ subunits, and form stable Gβγ dimers with the exception of Gβ5, giving rise to 48 possible combinations of Gβγ (19, 20). It has been shown that most Gγ subtypes comparably interact with the two most predominant Gβ types in cells, Gβ1 and Gβ2, with the exception of Gγ11 for Gβ2 (21). Similar affinities of Gαi1 for Gβγ types have also been demonstrated (20). Studies have suggested the possibility of specific Gβγ subtypes possessing higher affinities toward certain GPCRs or effectors. Using in vitro reconstituted heterotrimers and activated GPCRs, heterotrimers with certain Gγ subtypes exhibited higher affinities for specific GPCRs (20). In addition, specific structural motifs in GPCRs, preferring interactions with certain Gβγ isoforms, also have been reported for adenosine family receptors (22, 23). Assigned cellular functions to the availability of specific Gβ or Gγ subtypes have also been shown (24, 25). For instance, modulation of Golgi vesiculation and cellular secretions by Gγ11 and differential ion channel control by Gγ9 and Gγ3 subunits have been demonstrated (24, 25). Gγ3 and Gγ5 were shown to control predisposition of mice to seizures (26).

Although these investigations have primarily assigned subunit identity of either Gβ or Gγ subtype to specific signaling activities and cellular functions, molecular and mechanistic basis of such a signaling specificity has not been provided. Gβ subunits have a conserved structure with a >80% identity among their isoforms. However, Gγ isoforms show a significant sequence diversity ranging from ∼20–80% (19, 27). Therefore, if the Gβγ diversity is a crucial modulator of its signaling and associated cell behaviors, the Gγ identity in these dimers is likely to be a primary regulator of Gβγ signaling. Although Gβγ is classically considered plasma membrane (PM) bound, recent work has shown that, upon GPCR activation, Gβγ translocates from the PM to internal membranes (IMs) until an equilibrium is reached (25). Interestingly, translocation half-time (Tt½) and the extent |T| are governed by the type of accompanying Gγ subunit (25, 29). These results further suggest that the PM affinity of a Gβγ is Gγ subtype–dependent. Because, Gγ provides the only PM anchor for Gβγ, the accompanying Gγ subtype–dependent translocation ability of Gβγ suggests that the Gγ subunit controls the PM affinity of the accompanying Gβγ. Considering that the majority of Gβγ-effector interactions take place at the PM, Gγ-governed PM affinity is likely to be crucial for Gβγ signaling. Thus, this study is focused on examining how cells employ a selected group of Gγ subunits to tune signal propagation from activated GPCRs to Gβγ effectors, controlling signaling and macrophage migration.

Results

Gγ subtype identity-specific control of PI3Kγ activation by Gβγ

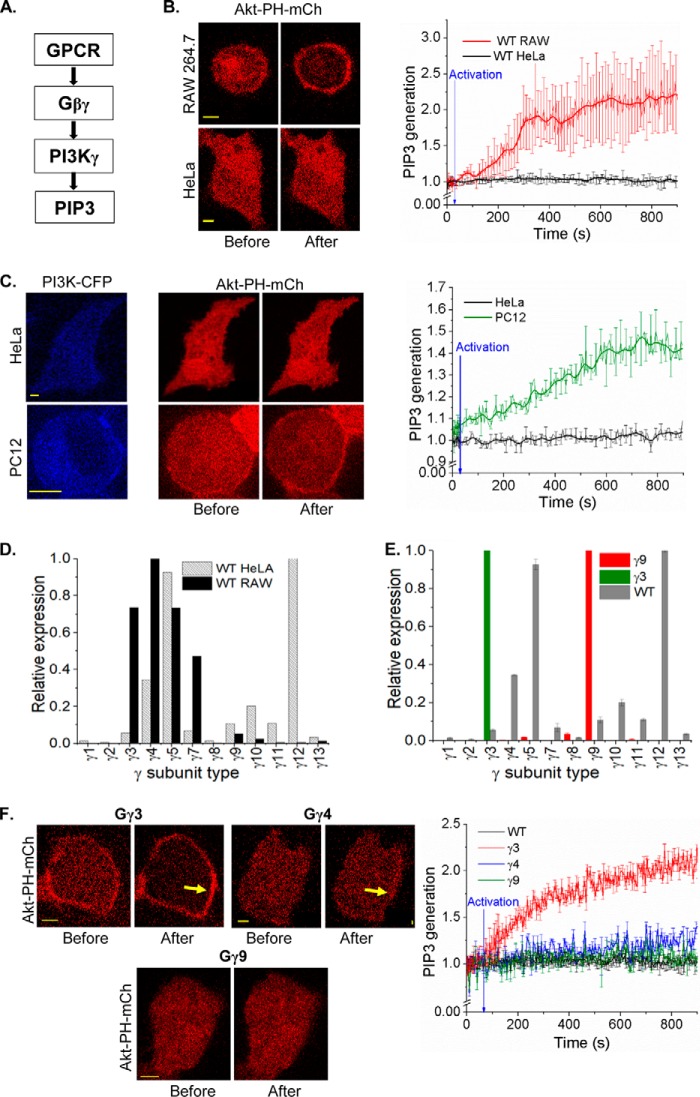

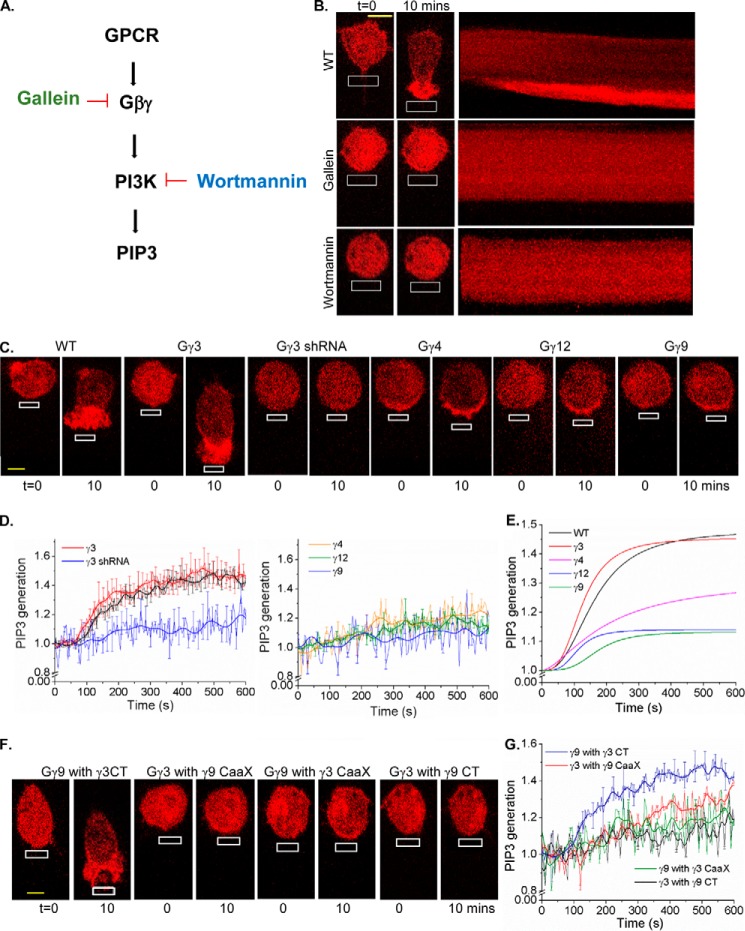

PIP3 is a major regulator of lamellipodia formation in the leading edge of migratory cells (30). Because Gβγ-PI3K interaction leads to the PIP3 generation (Fig. 1A), we examined whether PIP3 production is controlled in a Gγ subtype–dependent manner. To interact with Gβγ and catalyze PIP3 production, PI3K subunit p110 should translocate to the PM upon activation (31, 32). The signaling circuit that drives PIP3 production is composed of GPCRs, Gβγ, and PI3Kγ subunits (Fig. 1A). PIP3 generation was measured using the translocation of a fluorescently tagged PIP3 sensor (Akt-PH-mCherry) from cytosol to the PM. We have previously shown that localized blue opsin activation results in a robust PIP3 production at the leading edge and directional motility of RAW264.7 cells (33). Because both blue opsin and chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) activate G proteins with nearly similar efficiencies, blue opsin was employed to induce macrophage migration (Fig. S1, A–C). Activation of Gi-coupled GPCR, blue opsin, induced a robust PIP3 production in RAW cells (Fig. 1B, top). This suggests that the type of Gβγ in RAW cells supports PI3K activation. However, the same receptor activation in HeLa cells failed to produce an observable PIP3 response (Fig. 1B, lower). Interestingly, both cell types produced similar G protein activation upon blue opsin activation, when measured using translocation of YFP-Gγ9 and YFP-Gγ3, respectively, indicating equivalent G protein activations (Fig. S1, D–F). Therefore, either absence of proper type of Gβγ or low expression of PI3Kγ or both are the source of this lack of PIP3 production. Similar to HeLa cells, PC12 cells also failed to show PIP3 production upon GPCR activation. However, unlike HeLa cells, PC12 cells exhibited augmented PIP3 generation upon expression of PI3Kγ, directing the study toward the type of Gβγ in HeLa cells (Fig. 1C). Real-time PCR data from RAW and HeLa cells revealed that they express substantially different Gγ subunit profiles (Fig. 1D). Compared with RAW cells, HeLa cells show an ∼6-fold lower expression of Gγ3, and the expression of Gγ4 is also significantly lower in HeLa cells. Expression of Gγ3 in HeLa cells resulted in an elevated basal PIP3, even without GPCR activation (Fig. 1F). Blue opsin activation resulted in a robust PIP3 production in these cells. Although Gγ4 expression did not promote an elevation of basal PIP3, opsin activation exhibited a minor increase in PIP3 in HeLa cells (Fig. 1F, yellow arrows). Nevertheless, Gγ9-expressing HeLa cells failed to induce PIP3 production either at the basal state or upon opsin activation (Fig. 1F). Real-time PCR data indicated that overexpression of a Gγ subunit results in the reduction of the fractional contribution of endogenous Gγ subunits to the pool, making the introduced Gγ subunit dominant, creating nearly a mono-Gγ system (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Gγ identity-controlled PIP3 generation. A, pathway for Gβγ-mediated PI3K activation. B, wildtype (WT) HeLa and RAW 264.7 cells expressing the PIP3 sensor, Akt-PH-mCherry and blue opsin–mTurquoise. Cells supplemented with 50 μm 11-cis-retinal were imaged every 5 s for mCherry (with 594 nm). Blue opsin activation with 445 nm blue light–induced translocation of cytosolic PIP3 sensor to the PM only in RAW cells but not in HeLa cells. The plot shows the accumulation Akt-PH-mCherry on the PM. Blue arrow points to initiation of optical activation (at 30 s). Intensities are baseline normalized. C, PI3Kγ expression in a HeLa cell failed to induce PIP3 generation on blue opsin activation (black trace). PC12 cells that showed no PIP3 response elicited a robust repose upon expression of PI3Kγ (green trace). Blue arrow indicates optical activation. D, comparison of real-time PCR Gγ profiles of HeLa and RAW cells. HeLa cells express mRNA for Gγ12 and Gγ5 in abundance, and Gγ4 and Gγ3 are prominent in RAW cells. E, Gγ9 (red) and Gγ3 (green) overexpression induced changes to the Gγ profile in HeLa cells. The overexpressed Gγ type appears to dominate native Gγ. F, HeLa cells expressing Gγ3, blue opsin–mTurquoise, and Akt-PH-mCherry showed an intense PIP3 generation compared with the WT cells upon blue opsin activation. Images and the plot show Gγ4 expression showed a minor (blue trace), whereas Gγ9 showed no PIP3 generation (green trace), compared with WT (black trace) and Gγ3 (red trace) on the PM. The plot shows the corresponding PIP3. Intensity values are baseline normalized, blue arrow indicates optical activation (scale bar, 5 μm; error bars: S.E.).

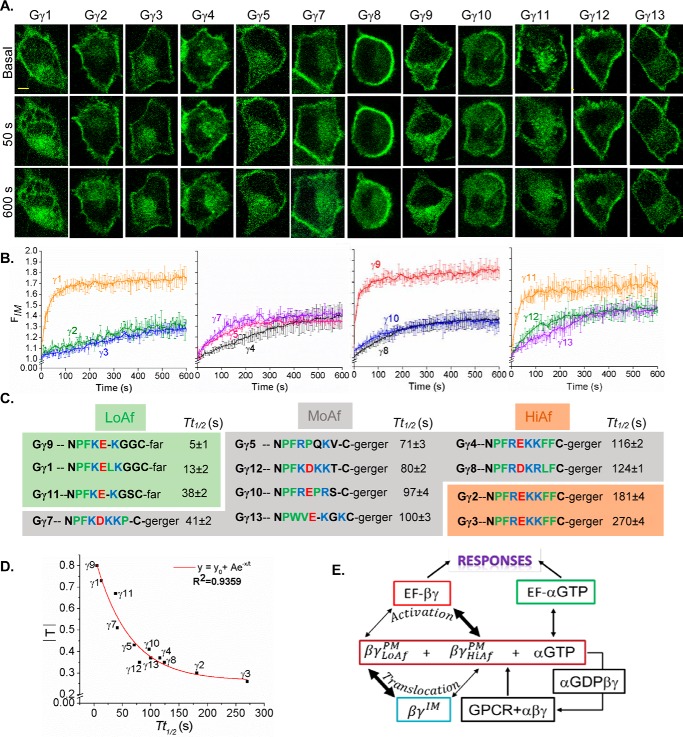

Optogenetic determination of PM affinities of 12 Gγ subunits using Tt½ of Gγ

Measurement of G protein activation upon ligand addition is prone to experimental artifacts because of inconsistencies associated with the agonist injection and variations in its diffusion through the culture media. This hinders calculation of precise Tt½ as well as extent of translocation Gβγ. Thus, to measure the dependence of Gγ type on translocation properties of Gβγ, optically controlled activation of GPCR–G protein signaling was used as follows. HeLa cells expressing blue opsin together with each of YFP-tagged 1–13 Gγ types were examined for translocation upon activation of blue opsin (Fig. 2, A–C). Cells were supplemented with 11-cis retinal for 5 min before opsin activation. Gβγ translocation was measured using YFP fluorescence dynamics in IMs (FIM versus time curves), and the data were fitted to the logistic function

| (1) |

because GPCR activation results in an approximately sigmoidal increase in Gβγ in IMs, which reaches saturation over time. Using the fitted curves, Tt½ and the extent of translocation |T| = (Tmax − Tbase) of individual Gγ subtypes were calculated (Table S1). The plot of |T| versus Tt½ (Fig. 2D) exhibited a strong exponential decay correlation (adjusted R2 = 0.94). This suggests that the Gγ types with moderate to slow translocation rates are translocation-deficient (small |T|). These data also indicate that |T| and Tt½ of Gγ are linked and likely to be controlled by the ability of Gβγ to interact with the PM (Fig. 2E). Considering the link between the Tt½ of Gβγ dissociation from the PM and free energy of the associated transition state (ΔG) the Tt½ of Gβγ was considered as an index of the PM residence time and the PM affinity of Gβγ because the Tt½ includes the effects of Gβγ shuttling between IMs and the PM.

Figure 2.

Gγ-identity driven differential translocation of Gβγ. A, HeLa cells expressing blue opsin–mTurquoise and each of the 12 Gγ subunits with a YFP fluorescent tag. Cells were supplemented with 50 μm retinal and were imaged for YFP (515 nm) and activated with 445 nm light at 2-s intervals in a time-lapse series. This process was continued for 10 min where the YFP fluorescence changes reached the equilibrium. B, plots show baseline normalized YFP fluorescence increase in IMs over time (error bars, S.E.; n = 10; scale bar, 5 μm). C, alignment of carboxyl termini (CT) sequences of 12 Gγ, indicating the properties of amino acids (red, acidic; blue, basic; green, hydrophobic uncharged; black, other residues) and their translocation half-time values (Tt½). Here, Gγ types are grouped, based on their PM affinities. D, plot of Tt½ versus |T| shows an exponential decay relationship. E, schematics of GPCR activation–induced G protein heterotrimer activation and dissociation. LoAf-Gβγ translocates from the PM to IMs faster compared with HiAf-Gβγ, whereas HiAf-Gβγ interacts with effectors to initiate signaling pathways leading to cellular responses efficiently compared with LoAf-Gβγ.

Tt½ values of Gγ9 translocation were identical in HeLa, RAW, and HEK cells (Fig. S1, A–F). This demonstrates that translocation properties of Gγ types are conserved among cell types, suggesting conserved PM affinities of Gγ types. Although Gγ types only possess two types of lipid anchors (geranylgeranyl and farnesyl) at their carboxyl terminal cysteine (in the CaaX motif), they exhibit a discrete series of Tt½ values (Table S1). Therefore, distinct regions of PM-interacting pre-CaaX motifs of Gγ subunits appear to provide further control over their PM affinities, resulting in a discrete series of Tt½ values.

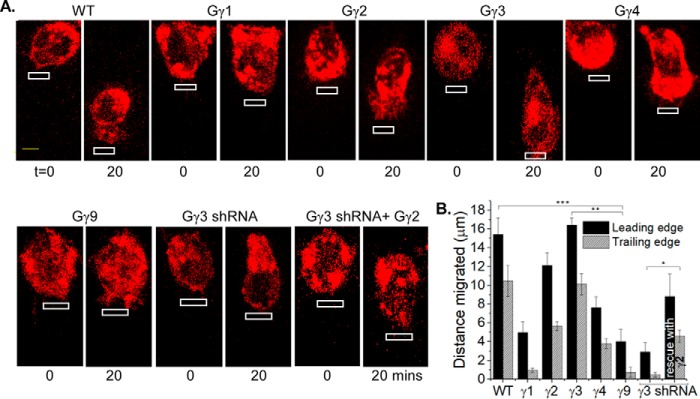

Gγ-dependent control of chemokine pathway–mediated RAW cell migration

Because the subtype identity of Gγ controls PIP3 formation, we examined whether cell migration is also controlled in a Gγ type–dependent manner. Real-time PCR data showed that ∼30% of Gγ in WT RAW 264.7 cells is Gγ3, a high PM affinity (HiAf) Gγ type (Tt½ = ∼270 s) (Fig. 1D). In response to localized optical activation of blue opsin, RAW cells migrate efficiently with a leading edge velocity (νLE) of 0.82 μm/min and trailing edge velocity (νTE) of 0.51 μm/min (Fig. 3, A and B). Knockdown of endogenous Gγ3 using the most effective shRNA identified by screening five constructs (Fig. S2) resulted in a complete cessation of cell migration (Fig. 3, A and B). Nonspecific shRNA did not affect WT RAW cell migration. Expression of HiAf-Gγ2 (Tt½ = ∼181 s) in Gγ3 knockdown cells resulted in rescuing the lost migration ability with νLE: 0.61 μm/min and νTE: 0.28 μm/min (Fig. 3, A and B). Expression of low PM affinity (LoAf) Gγ subtypes showed a marked reduction of migration, i.e. Gγ9 (Tt½ = ∼5 s) → νLE: 0.20 μm/min, νTE: 0.03 μm/min, and Gγ1 (Tt½ = ∼13 s) → νLE: 0.24 μm/min, νTE: 0.04 μm/min (Fig. 3, A and B). Further, expression of moderate PM affinity (MoAf) Gγ4 (Tt½ = ∼116 s) also reduced the migration ability of WT RAW cells substantially (νLE: 0.38 μm/min, νTE: 0.18 μm/min). Although, LoAf Gγ expressing cells occasionally showed lamellipodia formation at the leading edge, trailing edge retraction was not observed. These data collectively suggest that the higher the PM affinity of Gγ, the greater the migration ability of RAW cell. To examine the universal nature of HiAf Gγ subunit requirement in chemokine pathways, we examined whether the introduction of HiAf Gγ3 helps nonmigratory HeLa cells to migrate. Localized opsin activation in HeLa cells expressing Gγ3 showed a distinct trailing edge retraction with lamellipodia formation at the leading edge, resulting in a net movement of the cell. No such responses were observed in WT or Gγ9 expressing HeLa cells for similar signaling activation (Fig. S3).

Figure 3.

Subtype-specific control of macrophage migration by Gγ. A, RAW 264.7 cells expressing blue opsin–mCherry and a selected Gγ subunit, supplemented with 50 μm 11-cis-retinal. Blue opsin was activated in confined regions of cells using a 445 nm laser with 0.22 microwatts/μm2 power in every 2-s interval (white boxes). The images show cells before and after 20 mins of blue opsin activation. Note the difference in cell movement toward the optical input with respect to the Gγ type the cell possesses. Gγ3 expressing cell shows an almost identical cell migration as the WT, and Gγ2 also supports migration. Note the inhibition of cell migration in Gγ3 knockdown cells. This migration loss was rescued by expressing HiAf-Gγ2, but none other. B, bar graph shows the relative displacement of cells' leading and trailing edges, with blue opsin activation (error bars, S.E.; n = 12; *, p = 0.021; **, p < 0.0001; ***, p < 0.0001; scale bar, 5 μm).

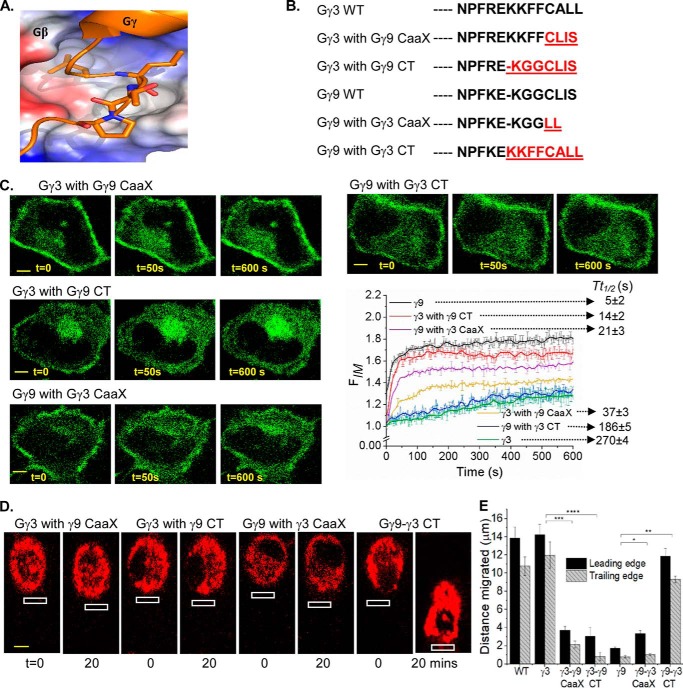

Control of RAW cell migration by CaaX and pre-CaaX residues in the carboxyl termini (CT) of Gγ

Because the CT of Gγ provides sites for Gβγ dimers to anchor and interact with the PM, which is required for Gβγ signaling, properties of their CT on RAW cell migration was examined. The CT sequences of Gγ exhibit a significant diversity (Fig. 2C) (19, 27). Sequence alignment and structural data show that, after the conserved Phe-59 residue in all Gγ subtypes (except Gγ13), CT region loops out from a conserved hydrophobic pocket on Gβ (Figs. 2C and 4A), delineating its last contact point with Gβ (Fig. 4A) (34). The pre-CaaX region of Gγ (between Phe-59 and the CaaX) therefore appears to interact with the PM and partially modulates the PM affinity of Gβγ. The lack of electron density for the CT of Gγ in Gβγ crystal structures indicates that this region is unstructured and suggests dynamic interactions with the PM. We employed a group of Gγ mutants composing the body of HiAf-Gγ with a substituted CaaX and/or pre-CaaX motifs from LoAf-Gγ and vice versa (Fig. 4B). Translocation properties of these mutants resembled properties of WT Gγ in which the introduced CT motifs were originated (Table S1). For instance, Gγ9 with pre-CaaX plus CaaX of Gγ3 (Gγ9-γ3CT) exhibited similar translocation properties to Gγ3. On the contrary, Gγ3 with pre-CaaX plus CaaX regions of Gγ9 (Gγ3-γ9CT) exhibited similar translocation properties to Gγ9 (Fig. 4C). The incorporation of an extra cysteine to Gγ3 CaaX moiety eliminated the translocation ability of Gβγ3 (Fig. S4A). This is likely because of the second geranylgeranyl lipid anchor attachment. Deletion of cysteine from the CaaX motif resulted in complete disruption of PM localization of Gβγ9, limiting it only to the cytosol (Fig. S4B), indicating the lipid anchor requirement for PM interaction of Gβγ. The cells expressing above-mentioned mutants were also examined for their ability to modulate RAW cell migration, for instance, Gγ9-γ3CT mutant–induced cell migration. On the contrary, cells expressing Gγ3-γ9CT mutant failed to migrate, recapitulating migration behavior of RAW cells expressing Gγ9 (Fig. 4, D and E). Collectively, these data suggest that CaaX and pre-CaaX residues of the CT of Gγ control the PM affinity and the signaling efficiency of Gβγ.

Figure 4.

Carboxyl terminus of Gγ governs rates of Gβγ translocation and the extent of cell migration. A, crystal structure of the CT region of Gγ in complex with Gβ (∼Phe-59 of Gγ, the last Gβ contact point) exposing the hydrophobic binding pocket in Gβ. B, sequence alignment of CT mutants of Gγ3 and Gγ9. C, HeLa cells expressing GFP-Gγ mutants and blue opsin–mCherry, supplemented with 11-cis retinal. The cells were imaged for GFP (488 nm) to capture blue opsin activation–induced translocation. Note the significant difference in mutant translocation compared with WT counterparts (error bars, S.E.; n = 10; scale bar, 5 μm). D, RAW 264.7 cells expressing each of the mutant Gγ and blue opsin–mCherry, supplemented 11-cis-retinal. Blue opsin in cells were activated locally (white box) in 2-s intervals for 20 min to induce migration. E, the histogram shows the movement of leading and trailing edges. Permutations to the CT sequences clearly altered the cell migration ability (error bars, S.E.; n = 12; *, p = 0.0009 for the leading edge and 0.5714 for the trailing edge; **, p < 0.0001; ***, p < 0.0001; ****, p < 0.0001; scale bar, 5 μm).

Modulation of RAW cell migration potential by Gγ subtype–dependent activation of PI3Kγ

Because PIP3 is a key regulator of chemokine-induced cell migration, we examined if PIP3 production is Gγ-type dependent. RAW cells expressing the PIP3 sensor, Akt-PH-mCherry, showed a significant PIP3 accumulation at the leading edge upon localized optical activation of blue opsin (Fig. 5B and Movie S1). Inhibition of Gβγ with gallein and PI3Kγ with wortmannin ceased PIP3 production and migration of RAW cells (Fig. 5, A and B). A gallein-like compound, fluorescein did not show any effect for either PIP3 production or migration. Cells expressing Gγ3 showed a leading edge PIP3 production and a directional migration similar to the responses exhibited by WT RAW cells (Fig. 5C and Movie S2). On the contrary, plots show that Gγ9 expressing RAW cells exhibit mild or no PIP3 production. These cells further failed to migrate as well. (Fig. 5C and Movie S3). Gγ3 knockdown cells showed neither PIP3 production at the leading edge nor cell migration upon opsin activation (Fig. 5, C and D and Movie S4). Additionally, RAW cells expressing Gγ3 mutants composed of either pre-CaaX or CaaX motifs or both from Gγ9 failed to produce PIP3 at the leading edge and subsequently migrate (Fig. 5, F and G). Interestingly, cells expressing Gγ9-γ3CT mutant (both CaaX and pre-CaaX from Gγ3) showed both PIP3 production and cell migration. However, Gγ9 mutants with either pre-CaaX alone or CaaX alone from Gγ3 failed to show PIP3 production or cell migration. This can be understood by examining PM affinities (Tt½ values) of Gγ types and their mutants listed in Table S1. The order of Tt½ is Gγ3 > γ9-γ3CT > γ3-γ9CaaX > γ9-γ3CaaX > γ3-γ9CT > γ9. PIP3 dynamics in RAW cells expressing Gγ types exhibited a reasonable fit to the logistic function with an adjusted R2 > 0.93 (Fig. 5E). This comparative PIP3 response analysis illustrates that cells expressing only HiAf-Gγ subtypes, including Gγ3, Gγ2, and Gγ9-γ3CT mutant elicited a significant PIP3 generation. Such a robust PIP3 production appears to be required for cell migration. Fitted curves also showed that both WT and HiAf-Gγ3 expressing RAW cells possess comparable mean rates of PIP3 production, 0.0022 s−1 and 0.0030 s−1, respectively. However, the mean rate of PIP3 generation in MoAf-Gγ4 expressing cells (0.0009 s−1) was closer to Gγ9 (0.0007 s−1) and Gγ12 (0.0012 s−1) than to Gγ3. Collectively, these data indicate that only Gγ types with the highest PM affinity support significant PIP3 production and RAW cell migration.

Figure 5.

Gγ type–dependent activation of PI3Kγ during macrophage migration. A, GPCR-mediated PIP3 generation pathway and its selected inhibitory points. B, RAW 264.7 cells expressing Akt-PH-mCherry and blue opsin, supplemented with 50 μm 11-cis-retinal. On localized blue opsin activation with 445 nm (white box), WT cells showed the PIP3 production at the activated leading edge. Cells treated with PI3K inhibitor wortmannin and Gβγ inhibitor gallein inhibited both PIP3 production and cell migration, confirming that PIP3 is required for directional cell migration. C, RAW 264.7 cells expressing Akt-PH-mCherry, blue opsin–mTurquoise, a Gγ subunit (Gγ3, Gγ9, Gγ4, Gγ12) and supplemented with 50 μm 11-cis-retinal. On localized blue opsin activation with 445 nm (white box), Gγ3 expressing cells showed PIP3 generation at the leading edge. However, Gγ4, Gγ12, and Gγ9 expressing cells showed minor/no PIP3 accumulation. Gγ3 knockdown cells also showed no PIP3 generation. D, plots show the PIP3 generation with Gγ3, Gγ9, Gγ4, Gγ12 overexpression and Gγ3 knockdown compared with the WT. E, smoothed curves fitted to logistic function show Gγ type–dependent differential PIP3 responses. F, RAW 264.7 cells expressing Akt-PH-mCherry, blue opsin–mTurquoise, each of the mutant Gγ types and supplemented with 50 μm 11-cis-retinal. Upon migration induction, cells expressing the mutant Gγ9-γ3CT showed both PIP3 as well as migration. Failure to exhibit migration in Gγ9-γ3CaaX cells shows the significance of the pre-CaaX motif of Gγ in Gβγ signaling. Gγ3-γ9CT mutant cells exhibited neither PIP3 production nor migration. G, the plot shows PIP3 generation in RAW cells expressing CT mutants of Gγ (error bars, S.E.; n = 15; scale bar, 5 μm).

Gγ subtype–dependent control of Gβγ-mediated PLCβ activation

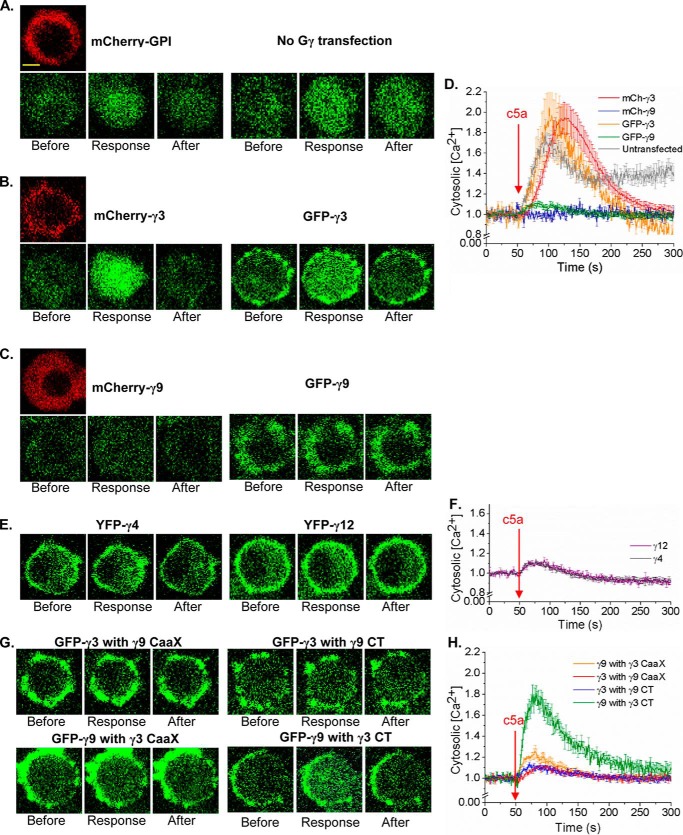

Recently, we demonstrated that Gi-coupled GPCR activation–induced RAW cell migration requires an increase in cytosolic calcium (Ca2+) which is governed by Gβγ-mediated activation of PLCβ to induce trailing edge retraction (18). Thus, we examined if PLCβ activity in RAW cells is also controlled in a Gγ subtype–dependent manner, in the same way it controlled PI3Kγ activation. Ca2+ mobilization upon endogenous Gi-coupled complement component 5a receptor (c5aR) activation in RAW cells with 10 μm c5a (35) was measured using a fluorescence probe for Ca2+, Fluo-4 AM. WT and HiAf-Gγ3 expressing cells showed Ca2+ responses to a higher degree (Fig. 6, A, B, and D), whereas LoAf-Gγ9 expressing RAW cells showed minor or no Ca2+ response upon c5aR activation (Fig. 6, C and D). Interestingly, MoAf-Gγ4 and Gγ12 expressing cells only exhibited a relatively weak response (Fig. 6, E and F). Replacement of the entire CT or CaaX motif alone in Gγ3 with those of Gγ9, respectively, resulted in loss of Ca2+ mobilization ability of WT Gγ3 (Fig. 6, G and H). Although expression of Gγ9-γ3CaaX mutant failed to elicit Ca2+ mobilization, mutant Gγ9-γ3CT showed a Ca2+ response, which is equivalent to responses exhibited by WT as well as Gγ3 expressing RAW cells (Fig. 6, G and H). In addition, we confirmed that the resultant Ca2+ responses are similar for Gγ with different fluorescent tags (Fig. 6, A–D).

Figure 6.

PLCβ activation induced differential Ca2+ response with different Gγs. RAW 264.7 cells expressing different WT Gγs and Gγ mutants were stimulated with 10 μm c5a addition to activate endogenous c5a receptors (c5aRs) after 30-min Fluo-4 incubation. Cells were imaged at 40× magnification to capture the Ca2+ response. A–C, control (A) (mCherry-GPI and untransfected), (B) Gγ3 expressing cells showed greater Ca2+ response compared with (C) Gγ9 expressing cells, which showed almost no Ca2+. Scale bar, 10 μm. D, plot shows the difference in Fluo-4 signal (GFP fluorescence) increase in cells, indicating differential Ca2+ release to the cytoplasm depending on the Gγ subtype they overexpress. Also, it shows that the fluorescent tag of the Gγ subtype is not affecting the Ca2+ response (n = 8). E and F, MoAf-Gγ4 and Gγ12 expressing cells showed minor Ca2+ response with c5AR activation (n = 8). G and H, Gγ9 mutants with Gγ3 CaaX and Gγ3 CT showed an increased Ca2+ response compared with WT Gγ9, whereas Gγ3 with Gγ9 CaaX and Gγ9 CT showed a reduced Ca2+ response compared with WT Gγ3, confirming differential Gβγ-effector interactions with respect to the difference in the PM affinity thus different PM residence times of Gβγ (error bars, S.E.; scale bar, 10 μm).

Tt½ of Gγ is a strong predictor of Gβγ effector activation ability

The purpose was to examine the hypothesis that the extent of Gβγ effector responses elicited upon GPCR activation in a cell can be predicted using the averaged Tt½ of the endogenous Gγ pool. The experimental process to test this concept is given in Fig. 7A. PIP3 production in HeLa cells expressing each of the 12 Gγ subtypes upon blue opsin activation was measured and plotted against the Tt½ of Gγ types (Fig. 7A, blue box). The extent of PIP3 production in each Gγ expressing cell was considered as the effector activation, |EF|expGγ, and was measured using baseline-normalized increase of Akt-PH-mCherry fluorescence at the PM because of PIP3 production (Fig. 7B). Tt½ values of each Gγ type translocation were also similarly calculated by measuring YFP-Gγ translocation (Fig. 2, A–C). The fitted straight line on the resultant |EF|expGγ versus Tt½ (HeLa effector plot, blue box) exhibited an R2 value of 0.94 (Fig. 7C). This indicates a linear relationship between the Gβγ effector responses and the PM affinities of Gβγ. Next, translocation properties of endogenous Gβγ pool in HeLa and RAW cells were measured using blue opsin activation–induced YFP-Gβ1 translocation (Fig. 7D). Because Gβ translocates with endogenous Gγ, Tt½ of Gβ was considered as an indicator of endogenous Gγ translocation and we termed it average Tt½ (avg-Tt½). The fast Tt½ of Gβ observed in Gγ9 expressing cells (Tt½ of Gβ1 = 7 ± 2 s and Gβ2 = 6 ± 1 s) confirms that Gβ represents translocation properties of endogenous or introduced Gγ (Fig. 7, D and E and Table S2). The avg-Tt½ value observed for RAW cells (221 ± 5 s) was greater than avg-Tt½ of HeLa cells (93 ± 2 s) (Fig. 7D and Table S2). These results suggest that, compared with HeLa cells, RAW cells express more HiAf-Gγ types. These data are also in agreement with real-time PCR data of Gγ mRNA (Fig. 1D). To ensure that the type of Gβ does not influence endogenous Gγ translocation, similar experiments were performed in both HeLa and RAW cells, however expressing YFP-Gβ2 (Fig. 7E and Table S2). The observed Tt½ of Gβ1 and Gβ2 were comparable, suggesting that the type of Gβ does not alter the Tt½ of Gγ.

Figure 7.

Testing Tt½ of Gγ as a predictor of a cell's ability to control Gβγ effectors. A, experimental process of predicting Gβγ effectors activity using Gγ type–dependent PM affinity (Tt½). B, plots showing the extent of blue opsin activation–induced PIP3 generation in HeLa cells expressing each of the 12 Gγ types. Smoothed and logistic function fitted curves of PIP3 generation with all Gγs. C, plot of |EF| versus Tt½ of all 12 Gγ types. The |EF| was measured using PIP3 production on the PM in HeLa cells expressing each of the 12 Gγ types and Akt-PH-mCherry. D, HeLa cells expressing blue opsin–mTurquoise, mCherry-Gγ9, either YFP-Gβ1 or YFP-Gβ2, respectively, supplemented with 50 μm 11-cis-retinal. On blue opsin activation, both Gβ1 and Gβ2 exhibited Tt½ closer to that of Gγ9, further confirming that the translocation properties of Gβ represent the prominent Gγ subtype expressed in the cell. E, HeLa and RAW cells expressing blue opsin–mTurquoise and either YFP-Gβ1 or YFP-Gβ2, respectively, were supplemented with 50 μm 11-cis-retinal. Cell was imaged for YFP and blue opsin was activated with 445 nm light every 3 s. Gβ translocation exhibited the average translocation properties of the entire pool of endogenous Gγ. Gβ type does not influence translocation properties of endogenous Gγ in HeLa cells. The plot shows that Tt½ of Gβ1 and Gβ2 translocation was closer to the Tt½ of the most abundant Gγ of each cell type. F, blue opsin activation–induced experimental |EF| (PIP3 response) measured in WT HeLa and RAW cells expressing blue opsin and the PIP3 sensor (error bars, S.E.; n = 10; scale bar, 5 μm).

Next, blue opsin activation induced PIP3 production in WT HeLa, and WT RAW cells were measured to obtain effector activity induced by endogenous Gβγ (|EF|exp or Δ[PIP3]). Data show that RAW cells possess a 2-fold higher effector activation ability than HeLa cells (Fig. 7F). The avg-Tt½ obtained above for both HeLa and RAW cells (Fig. 7E) were then extrapolated on the HeLa effector plot (Fig. 7C) to obtain predicted effector activities (|EF|calc). The ratio of experimental and calculated effector activities (|EF|exp:|EF|calc) for HeLa and RAW cells were found to be 0.82 and 0.99, respectively. This shows that |EF|exp:|EF|calc ratios for both HeLa and RAW cells are closer to 1. Therefore, the avg-Tt½ of endogenous Gγ pool is a strong predictor of a cell's Gβγ effector-activation ability.

PM-residing ability of Gβγ produced upon GPCR activation on its effector activation potential

Similar to HiAf-Gγ types, moderate affinity Gγ (MoAf-Gγ) types also maintain considerably high Gβγ concentrations on the PM after GPCR activation (Fig. 2B). However, it was unclear why MoAf-Gγ expression does not promote robust PIP3 productions, as seen in HiAf-Gγ expressing cells (Figs. 5E and 7B). To comprehend this, a model was proposed in which Gβγ on the PM stays in a transiently active conformation (Gβγ-PM*) which can activate effectors. We assume that the lifetime (τ) of this transiently active conformation is dependent on the corresponding Gγ type or more specifically the PM affinity of Gγ type. Using Gγ12 as a model MoAf-Gγ, we first examined if the observed lack of translocation in Gγ12 is controlled by factors other than its CT. We substituted CT of Gγ12 with CT of Gγ3 and Gγ9, respectively (Fig. S5). Compared with the moderate translocation observed in Gγ12 (Tt½ = ∼80 s) (Table S1), Gγ12-γ9CT mutant showed a fast translocation with Tt½ = ∼8 s, resembling translocation properties of Gγ9. As expected, Gγ12-γ3CT mutant translocated slower that Gγ12 (Tt½ = ∼232 s) (Fig. S5). Similar changes were observed for Gγ3-γ9CT mutant (Fig. 4C). Because the CT of Gγ does not interact with the receptor, the fast translocating mutants of MoAf- and HiAf-Gγ suggest that their heterotrimers are equally activated by the GPCR, as seen for heterotrimers with LoAf-Gγ through their intense Gβγ translocation. These observations indicate that, although MoAf-Gβγ are liberated from the heterotrimer and reside on the PM, a fraction of them are not conformationally appropriate for Gβγ effector activation. These findings are consistent with recent reports suggesting that K-Ras possesses orientation-dependent effector binding (36).

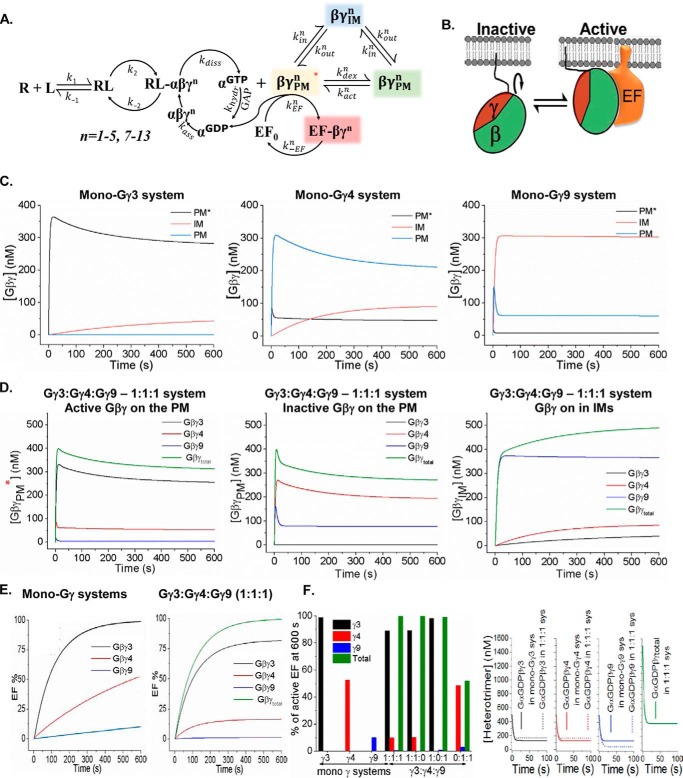

Data-guided computational modeling of Gγ subtypes–driven signal propagation

As an extension to our previous model (37), reactions for Gβγ effector activation in a multi-Gγ containing cell were modeled, to decipher how a diverse group of Gγ types in a cell controls Gβγ effector activities. The optimized model (Variation 3) encompasses reactions in Fig. 8A (see Equations S1 and S2, Variations). The model includes novel circuits for Gβγ to (a) activate effectors, (b) translocate to IMs, and (c) be in fluctuating conformationally active and inactive states on the PM GβγPMn* ⇆GβγPMn. Considering that many proteins fluctuate among multiple conformations, it is likely that Gβγ fluctuates among these structures while one particular conformation has a stronger affinity toward Gβγ effectors (Fig. 8, A and B) (36, 38, 39). The kinetic curves show that Gβγ in the mono-Gγ3 system is primarily in the PM-bound active state (Gβγ-PM*), and is available for effector activation (Fig. 8C). The simulations show low concentrations of Gβγ-PM* for mono-Gγ4 and mono-Gγ9 systems compared with mono-Gγ9. Simulations also demonstrate that, in mixed Gγ systems, Gγ3 is the primary contributor for the active Gβγ on the PM (PM*) (Fig. 8D). Concentrations of activated effectors ([βγPMtotEF]) were plotted as a function of time. The mono Gγ-systems exhibited effector responses (Fig. 8E), and are similar to the experimental PIP3 and Ca2+ responses observed in HeLa and RAW cells expressing specific Gγ subtypes, that we also defined as mono-Gγ systems. Simulations show that mono-Gγ3 systems rapidly activate 90% of the effectors in 195 s, whereas Gγ4 and Gγ9 systems exhibit minor effector activities.

Figure 8.

Data-guided computational modeling of signal transduction from GPCRs to the cell interior in multi-Gγ systems. A, the reactions representing the proposed mechanism of GPCR-G protein activation used in the model. B, Gβγ fluctuation between active–inactive conformations (GβγPMn* ⇆ GβγPMn), which is assumed in the optimized model. C–E, concentrations of signaling entities (Gα(GDP)βγ, Gα(GDP), Gα(GTP), GβγPM, GβγPM*, GβγIM, and GβγEF) as a function of time for the four cases considered in the model (mono-HiAf-Gγ3, mono-MoAf-Gγ4, mono-LoAf-Gγ9, and equal mix of Gγ3, Gγ4 and Gγ9). F, Gβγ effector responses in a multi-Gγ system. The model predicts the responses are primarily dominated by the HiAf-Gγ. This indicates that the highest affinity Gγ of the pool dictates the signaling activity in general.

Effector activation by mixed Gγ [βγPM3+4+9EF] system with equal compositions of HiAf-Gγ3, MoAf-Gγ4, and LoAf-Gγ9 (Fig. 8D) exhibited that Gγ3 interacts with effectors the most (Fig. 8E). In this system at 600 s, 99% of the effectors are activated and 82% of these effectors are bound to Gγ3 (i.e. [βγPM3EF]), 16% to Gγ4 ([βγPM4EF]), and 2% to Gγ9 ([βγPM9EF]). Here, effector activations by MoAf-Gγ4 and LoAf-Gγ9 are lower with respect to mono-Gγ systems. Thus, the model predicts that in mixed systems, physiological responses are primarily governed by HiAf-Gγ. This is also observed for 1:1 mixture of MoAf-Gγ4 and LoAf-Gγ9, where the activity is determined by the available higher affinity Gγ subtype (i.e. Gγ4, Fig. 8F). It is noteworthy that, if translocation rate constants are set equal for individual Gγ type (i.e., kinn = koutn), this activity dominance of HiAf-Gγ is not observed. When fluctuation between active–inactive Gβγ conformations was not incorporated, equal effector activity from Gγ3 and Gγ4 is observed, contradicting experimental observations.

Discussion

Considering diverse and unique tissue- and cell type–specific Gγ-type distribution patterns, the Gγ identity–specific regulation of Gβγ signaling can have a broader impact on the current understanding of GPCR-G protein signal transduction. If Gβγ were to be a unitary signaling entity, cells would have intense Gβγ signaling on all occasions of GPCR activation, which can be deleterious. For instance, RAW cells have a Gγ profile with HiAf-Gγ that supports PI3K activation and PIP3 production. However, for a usually immobile cell type like HeLa, intense PIP3 production may not serve a purpose and thus HiAf-Gγ expression is not required. Supporting this notion, Gγ3 expression allowed HeLa cells to produce PIP3 upon GPCR activation. The fundamental difference identified between the introduced Gγ3 over endogenous Gγ types in HeLa cells was the ability of Gγ3 to make Gβγ more available at the PM, where PIP3 production takes place. To catalyze PIP2 to PIP3, Gβγ recruits and activates PI3K subunits to the PM (40). Of the 12 Gγ types, only Gγ3 and Gγ2 promoted PIP3 production. This is likely because of the weak translocation properties of Gβγ3 that allows maintenance of a relatively higher concentration of free Gβγ on the PM. The Gγ-dependent differential PIP3 generation in HeLa cells hints at a plausible mechanism of how Gβγ effectors are recruited to the PM and activated by PM-bound fraction of HiAf-Gβγ. We recently showed that Gβγ controls PLCβ activation, induces Ca2+ mobilization, governing the trailing edge retraction during RAW cell migration (18). Similar to PI3Kγ, PLCβ1 and PLCβ2 are also cytosolic (41, 42). Our data suggest that PM targeting and/or activation of these Gβγ effectors are likely to be governed by the PM affinity of Gβγ. The extent of effector responses suggests that the stronger the PM affinity of Gβγ, the greater its potential to control signaling. Here we employed Tt½ as an index for the residence time on the PM or the PM affinity of Gβγ. The free energy of the translocation (ΔG) is considered as the energy required to dislodge Gβγ from the PM to the IM. Thus it is a direct measure of PM affinity of Gβγ to the PM. ΔG is related to a first-order reaction equilibrium constant (Keq) by ΔG = −RT ln Keq. For the Gβγ translocation process,

| (2) |

and the half-time, t½ can be expressed as k = 0.693/t½, thus ΔG = −RT ln(t1/2out/1/2in. This indicates that the longer the residence time on the PM, the greater the PM affinity. Translocation t½ of Gβγ is a complex measure which includes the shuttling of Gβγ between the PM and IMs. However the initial reaction is dominated by Gβγ dislodging from the PM (kin), thus, as shown above, Tt½ is a fair approximation of the PM affinity of Gβγ.

Gγ subunits interact with the PM through the prenyl group. The type of prenylation is decided by the CaaX motif sequence of Gγ. The prenylation with 20-carbon geranylgeranyl lipid provides a higher PM affinity to Gβγ compared with the 15-carbon farnesyl lipid attachment. Except for farnesylated Gγ9, Gγ1, and Gγ11, all other Gγ types are geranylgeranylated. However, only Gγ3 and Gγ2 supported RAW cell migration, suggesting factors additional to the type of prenylation control the PM affinity of Gγ. Interestingly, pre-CaaX regions of Gγ3 and Gγ2 are composed of ∼80% positively charged and hydrophobic residues, as opposed to ∼50% in farnesylated Gγ subunits. Extensive mutagenesis to the pre-CaaX region of Gγ suggested that this five- or six-residue region modulates Gβγ-PM interactions, in which positively charged and hydrophobic amino acids strengthen the PM affinity. Previously reported translocation data of Gγ mutants with altered pre-CaaX residues further validate the role of this motif in controlling the PM affinity (29). The complete loss of PM localization observed in Gγ9 upon cysteine removal from CaaX motif indicates that pre-CaaX region only serves as a strong modulator of PM affinity, whereas prenylation is essential for primary PM anchoring of Gβγ. By modulating properties of their pre-CaaX motifs, geranylgeranylated Gγ subunits managed to possess a discrete series of PM affinities.

Heterotrimers with specific Gγ types have been shown to possess higher affinities toward certain GPCRs (20, 43). However, an exchange of the CT of slow translocating Gγ3 and moderate translocating Gγ12 with the CT of Gγ9 resulted in fast translocating mutants, comparable to Gγ9. This can suggest that either (a) heterotrimer activation process is controlled by the CT of Gγ through modulating Gαβγ-GPCR interactions or (b) the PM affinity of generated Gβγ is dependent on the CT of Gγ subunit. Regardless, the CT of Gγ should hold a crucial control over Gβγ function, although our data strongly support possibility (b). We anticipate that, among the available Gβγ pool, LoAf- and MoAf-Gβγ types exist primarily to support GαGTP generation, whereas HiAf-Gβγ subunits activate Gβγ effectors. Our data also support that the PM-bound Gβγ composed of HiAf-Gγ types stay a longer fractional time in the active conformation, compared with their LoAf and MoAf associates. Lack of migration ability in Gγ3-knockdown RAW cells strongly supports this notion, because the remaining MoAf-Gγ types in RAW cells lack effector activation ability. Nevertheless, we are aware that, in addition to Gγ diversity, there are converging and diverging pathways and signaling components, including integrins, secretory proteins (i.e. matrix metalloproteinases) can influence the migration potential of a cell (44–46). Therefore, differences in cell migration potentials among cell types with diverse origins should be examined considering these potential inherent variables. Although we are in concert with these reports, our findings demonstrate that Gβγ-governed migration requires appropriate Gγ types with higher PM affinity. Supporting these findings, even a nonmigratory cell type like HeLa expressing HiAf-Gγ3, undergo directional migration upon blue opsin activation.

Avg-Tt½ of endogenous Gγ measured using Gβ translocation accurately predicted the ability of native Gβγ to control its effectors. Predicted effector activity using this method was similar to the PIP3 production observed in both RAW and HeLa cells. These observations suggest that Tt½, and therefore the PM affinity, of a Gγ type is a strong indicator of the ability of Gβγ to activate effectors. Thus, our observations collectively indicate that Gγ subunit diversity in a cell is a crucial factor in determining whether the cell has the ability to activate Gβγ effectors sufficiently to orchestrate the intended behaviors, including migration.

In the kinetic model with multi-Gγ and embedded experimental observations that Tt½ ∝ PM affinity and Tt½ ∝ |EF|, multiple mechanistic scenarios associated with G protein activation were attempted. The incorporation of an active–inactive conformation circuit to the PM-bound Gβγ was required to simultaneously capture all the experimental responses observed. These include the lack of effector activation by Gβγ associated with MoAf-Gγ. The incorporated circuits to the model indicated that (a) HiAf-Gβγ subtypes tend to readily activate effectors, initiating downstream signaling; (b) the majority of LoAf-Gβγ types translocate away from the PM to down-regulate signaling; and (c) the fraction of MoAf-Gβγ that did not translocate tends to minimize signaling by oscillating between PM-bound active–inactive conformational states. Although these conformational fluctuations are common for all types of Gβγ, the Gγ type and the PM affinity decide the lifetime of their active state. The ability of this model to recapitulate experimental responses indicates its reliability. Therefore, reactions and parameters embedded in our model (Table S3) are likely to closely reflect how PM affinities of Gγ subunits modulate information flow from the activated GPCRs to effectors. The model also allowed simulation of experimentally challenging in vivo conditions, including varying ratios of HiAf-Gγ:LoAf-Gγ and total Gβγ concentrations.

In summary, this study demonstrates that distinct translocation abilities of the 12 Gγ types provide Gβγ a diverse range of PM interaction and effector activation abilities. Because most Gβγ-effector activities occur at the PM, data confirm that the PM affinities of Gγ types expressed in a cell are deterministic to the potency of Gβγ effector as well as downstream signaling activation. Although we only show Gγ identity–dependent control of PI3Kγ and PLCβ, and their regulation of cell migration, it is likely that a plethora of Gβγ-mediated functions are similarly regulated. Because GPCR–G protein signaling is universally conserved and Gβγ signaling pathways are major drug targets, mechanisms we describe here can have a wide influence not only on cell migration but also in many areas of signaling.

Experimental procedures

Reagents

The reagents gallein (TCI America), Fluo-4 AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon), wortmannin 2APB (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), C5a (Eurogentec), U50488 hydrochloride (Tocris) were initially dissolved in DMSO and then diluted in Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) (Gibco) before adding to cells. 11-cis retinal (National Eye Institute) was initially resuspended in absolute ethanol and 2-μl aliquots (50 μm) were further diluted (2 μl for each aliquot) with absolute ethanol before introducing (2 μl) to cells in dark. SDF-1α (PeproTech) was reconstituted in deionized water to a concentration 100 μg/ml and further diluted with a buffer containing 0.1% BSA before adding to cells.

DNA constructs and cell lines

Engineering of DNA constructs used for blue opsin–mCherry, blue opsin–mTurquoise, Akt-PH-mCherry, and YFP-tagged Gγ1–Gγ13 have been described previously (33, 47, 48). YFP-β1 and -β2, κ-opioid receptor, PI3K-CA-CFP, and mCherry-GPI were kind gifts from Professor N. Gautam's lab, Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri. Gγ3, Gγ9, and Gγ12 mutants were generated using Gibson assembly (New England Biolabs (NEB)) (28). Parent constructs mCherry-Gγ3, mCherry-Gγ9, and YFP-Gγ12 were PCR amplified with overhangs containing expected nucleotide mutations. DpnI (NEB) digestion was performed on the PCR product to remove the parent construct. DpnI-digested PCR product was then mixed with the Gibson assembly master mix (NEB) and incubated at 50 °C for 45 min, which was followed by transformation of competent cells and plating on ampicillin LB agar plates. All the constructs used in this study possess the ampicillin-resistant pcDNA 3.1 vector backbone. Cell lines (HeLa, RAW 264.7, PC12, and HEK cells) were originally purchased from the American Tissue Culture Collections (ATCC) and authenticated using a commercial kit to amplify nine unique STR loci.

Cell culture and transfections

RAW 264.7 cells used in migration and PIP3 generation experiments were cultured in RPMI 1640 (10–041-CV; Corning, Manassas, VA) with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum (DFBS; Atlanta Biologicals) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (PS) in 60 mm tissue culture dishes. HeLa cells were maintained in minimum essential medium (MEM; CellGro) supplemented with 10% DFBS and 1% PS. Around 80% cell confluency, the growth medium was aspirated, 2 ml Versene (EDTA) (CellGro) was added, incubated for 3 min at 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator, and then cells were lifted and suspended in Versene. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 1000 × g for 3 min, Versene (EDTA) was aspirated, and the cell pellet was resuspended in its normal growth medium (RPMI/DFBS/PS for RAW and MEM/DFBS/PS for HeLa) at a cell density of 1 × 106/ml. For imaging experiments, cells were seeded on 35-mm glass-bottomed dishes (8 × 104 cells on each) with 15-mm inner diameter, prepared using no. 1 German cover glasses. Before cell seeding, dishes were washed with 2 N NaOH for 20 min, ethanol washed, and sterilized for 1 h using UV irradiation. A day following cell seeding, cells were transfected with appropriate DNA combinations using the transfection reagent PolyJet (SignaGen Laboratories), according to the manufacturer's protocol and then incubated in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were imaged after 16 h of the transfection.

Knockdown of Gγ3 in RAW 264.7 cells

Five shRNAs (TRCN0000036794–98; Sigma-Aldrich) were screened in RAW cells by co-expressing with GFP-Gγ3. Cells were screened for GFP expression, and the shRNA construct that induced the highest reduction in GFP-Gγ3 expression was selected as the most effective shRNA. The identified TRCN0000036795 shRNA (sequence: CCGGGCTTAAGATTGAAGCCAGCTTCTCGAGAAGCTGGCTTCAATCTTAAGCTTTTTG) was employed to knock down Gγ3 in the subsequent experiments. A scrambled shRNA was used as the control.

Live cell imaging to monitor Gβγ translocation, PIP3 generation, and optogenetic control of cell migration

Imaging system comprised a spinning-disk XD confocal TIRF (total internal reflection) imaging system composed of a Nikon Ti-R/B inverted microscope, a Yokogawa CSU-X1 spinning disk unit (5000 rpm), an Andor FRAP-PA (fluorescence recovery after photo-bleaching and photo-activation) module, a laser combiner with 40–100 milliwatt 445, 488, 515, and 594 nm solid-state lasers and iXon ULTRA 897BV back-illuminated deep-cooled EMCCD camera. Live cell imaging was performed using a 60×, 1.4 NA (numerical aperture) oil objective. In cell migration and PIP3 generation experiments, mCherry-tagged receptor blue opsin and the PIP3 sensor Akt-PH were imaged using 594 nm excitation-630 nm emission. To activate blue opsin, 50 μm 11-cis retinal (National Eye Institute) was added and incubated 3–5 min in dark. After incubation, the fluorescent sensor in cells was imaged to capture basal signaling in cell migration and PIP3 generation experiments (i.e. Akt-PH-mCherry in PIP3 experiments and blue opsin–mCherry in cell migration experiments), and then receptor blue opsin was activated by shinning 445 nm blue light at 0.1% transmittance and imaging was continued for 20 min. To examine the Gβγ translocation, YFP and GFP fluorescent tags on Gγ subunits were imaged for 10 min using 515 nm excitation, 527 nm emission or 488 nm excitation, 515 nm emission, respectively. Regular culture media or HBSS supplemented with 1 g/ml glucose preincubated in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator for 30 min were used as the imaging medium. During imaging, cells were maintained at 37 °C. To prevent focal plane drifts, Nikon Perfect Focus System (PFS) was engaged.

Cytosolic Ca2+ measurements

For intracellular Ca2+ measurements, RAW cells seeded on glass-bottom dishes and maintained in at 37 °C with 5% CO2 were transfected with a Gγ subtype on the following day of cell seeding. After 12–16 h of transfection, cells were washed twice with Ca2+-containing HBSS (pH 7.2) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator, Fluo-4 AM in the dark. After incubation, cells were washed twice with HBSS and 500 μl of HBSS was then used as imaging medium. The fluorescence intensity of Fluo-4 AM was continuously imaged at 1-s intervals using 488 nm excitation, 515 nm emission to capture signal before activation for 50 s. Endogenous c5aRs in RAW cells were activated with 10 μm c5a. Observed Fluo-4 AM fluorescence increase because of Ca2+ release was baseline normalized.

Real-time PCR, transcriptome, and RNA seq data analysis

To obtain the Gγ profile of WT HeLa and WT RAW 264.7 cells, RNA was extracted from cells grown in 100 mm tissue culture dishes after reaching 90–100% cell confluency. RNA extraction was performed using the GeneJet RNA purification kit following their given protocol. Extracted RNA was used as the template for cDNA synthesis with Radiant cDNA synthesis kit. cDNA product was quantified using the NanoDrop and used for real-time PCR (Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time qPCR system) in 96-well plates to obtain the Gγ profile. Radiant Green Lo-ROX qPCR kit (Alkali Scientific) was used in real-time PCR experiments and β actin gene was used as the housekeeping gene. To screen the Gγ profile alteration with Gγ3 and Gγ9 overexpression, HeLa cells were seeded in 100 mm tissue culture dishes and transfected with GFP-Gγ3 and GFP-Gγ9, respectively, at 70–80% cell confluency, and RNA was extracted after confirming greater than 70% transfection efficiency by observing under the microscope. This was followed by cDNA preparation and real-time PCR.

Statistics and reproducibility

Results of all quantitative assays (Gβγ translocation, cell migration, and PIP3 generation) are expressed as standard error of mean (S.E.) from n number of cells (indicated in the figure legends) from multiple independent experiments. Statistical analysis of cell migration data of WT and mutant Gγ subtypes was performed using two-tailed unpaired t test. p value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Computational modeling

The dynamic nature of the GPCR signal transduction has been modeled by a series of ordinary differential equations (Equation S2) which encompasses the series of reactions in Fig. 8A. Computations were performed in a custom Python 2.7 script with odeint module to numerically integrate the ordinary differential equations. The equations are an extension of our previous model for a ligand-activated signal transduction and is extended to allow for effector activation by multiple types of Gβγ subunits (HiAf, MoAf, and LoAf). The reaction mechanism is similar to our previous publication (37) with the classical GPCR activation cycle, and includes novel circuits for Gβγ to 1) activate effectors, 2) translocate to IMs, and 3) be in a conformationally inactive structure on the PM. The equations describe the rates of heterotrimer dissociation, heterotrimer association ( Equation S1), Gα(GTP) hydrolysis, Gβγ translocation to IMs, Gβγ oscillation to an inactive configuration, and Gβγ effector activation. The rates for heterotrimer dissociation and Gα(GTP) hydrolysis assume Michaelis-Menten kinetics; all others are assumed as first- or second-order reactions. The ordinary differential equations define the rates of formation or depletion of the important species in the signaling network (i.e. Gα(GDP)βγ, Gα(GDP), Gα(GTP), GβγPM, GβγPM*, GβγIM, and GβγEF). To incorporate multiple Gβγ subunits and consequently the Gγ diversity, there is an ordinary differential equation for each Gβγ type except the Gα(GTP) and Gα(GDP) concentrations. Numerically integrating these functions, the concentration of the species over time was determined.

Author contributions

K. S. and A. K. conceptualization; K. S., D. K., P. S., and M. T. data curation; K. S., P. S., and M. T. formal analysis; K. S. investigation; K. S., J. L. P., and D. K. methodology; K. S. and A. K. writing-original draft; K. S., J. L. P., and A. K. writing-review and editing; J. L. P. software; J. L. P., P. S., M. T., and A. K. validation; J. L. P. and A. K. visualization; A. K. resources; A. K. supervision; A. K. funding acquisition; A. K. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Donald Ronning for providing experimental support and discussions. We thank Dr. Richard Neubig for his valuable comments. We also thank Dr. N. Gautam for providing us with plasmid DNA for various G protein subunits. We acknowledge University of Toledo for funding. We thank National Eye Institute for providing 11-cis retinal. We thank the Ohio Supercomputing Center for the software and computing resources.

This work was supported by start-up funding from the University of Toledo. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S5, Movies S1–S4, Tables S1–S3, and Equations S1 and S2.

- GPCR

- G protein–coupled receptor

- AC

- adenyl cyclase

- PLC

- phospholipase C

- PM

- plasma membrane

- IM

- internal membrane

- HiAf

- high PM affinity

- LoAf

- low PM affinity

- νLE

- leading edge velocity

- νTE

- trailing edge velocity

- CT

- carboxyl termini

- c5aR

- complement component 5a receptor

- HBSS

- Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution

- PS

- penicillin-streptomycin

- DFBS

- dialyzed fetal bovine serum.

References

- 1. Khan S. M., Sleno R., Gora S., Zylbergold P., Laverdure J.-P., Labbé J.-C., Miller G. J., and Hébert T. E. (2013) The expanding roles of Gβγ subunits in G protein–coupled receptor signaling and drug action. Pharmacol. Rev. 65, 545–577 10.1124/pr.111.005603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McCudden C. R., Hains M. D., Kimple R. J., Siderovski D. P., and Willard F. S. (2005) G-protein signaling: back to the future. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 62, 551–577 10.1007/s00018-004-4462-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smrcka A. V. (2008) G protein βγ subunits: Central mediators of G protein–coupled receptor signaling. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 65, 2191–2214 10.1007/s00018-008-8006-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tang W. J., and Gilman A. G. (1991) Type-specific regulation of adenylyl cyclase by G protein beta gamma subunits. Science 254, 1500–1503 10.1126/science.1962211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sunahara R. K., and Taussig R. (2002) Isoforms of mammalian adenylyl cyclase: multiplicities of signaling. Mol. Interv. 2, 168–184 10.1124/mi.2.3.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kawano T., Chen L., Watanabe S. Y., Yamauchi J., Kaziro Y., Nakajima Y., Nakajima S., and Itoh H. (1999) Importance of the G protein gamma subunit in activating G protein-coupled inward rectifier K(+) channels. FEBS Lett. 463, 355–359 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01656-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smrcka A. V., and Sternweis P. C. (1993) Regulation of purified subtypes of phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C β by G protein α and βγ subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 9667–9674 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ikeda S. R. (1996) Voltage-dependent modulation of N-type calcium channels by G-protein βγ subunits. Nature 380, 255–258 10.1038/380255a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pitcher J. A., Inglese J., Higgins J. B., Arriza J. L., Casey P. J., Kim C., Benovic J. L., Kwatra M. M., Caron M. G., and Lefkowitz R. J. (1992) Role of beta gamma subunits of G proteins in targeting the beta-adrenergic receptor kinase to membrane-bound receptors. Science 257, 1264–1267 10.1126/science.1325672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ueda H., Nagae R., Kozawa M., Morishita R., Kimura S., Nagase T., Ohara O., Yoshida S., and Asano T. (2008) Heterotrimeric G protein βγ subunits stimulate FLJ00018, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rac1 and Cdc42. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 1946–1953 10.1074/jbc.M707037200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Niu J., Profirovic J., Pan H., Vaiskunaite R., and Voyno-Yasenetskaya T. (2003) G Protein βγ subunits stimulate p114RhoGEF, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for RhoA and Rac1: Regulation of cell shape and reactive oxygen species production. Circ. Res. 93, 848–856 10.1161/01.RES.0000097607.14733.0C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mayeenuddin L. H., McIntire W. E., and Garrison J. C. (2006) Differential sensitivity of P-Rex1 to isoforms of G protein βγ dimers. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 1913–1920 10.1074/jbc.M506034200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Herlitze S., Garcia D. E., Mackie K., Hille B., Scheuer T., and Catterall W. A. (1996) Modulation of Ca2+ channels by G-protein beta gamma subunits. Nature 380, 258–262 10.1038/380258a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Keller R. (2005) Cell migration during gastrulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17, 533–541 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Locascio A., and Nieto M. A. (2001) Cell movements during vertebrate development: Integrated tissue behaviour versus individual cell migration. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 11, 464–469 10.1016/S0959-437X(00)00218-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Luster A. D., Alon R., and von Andrian U. H. (2005) Immune cell migration in inflammation: Present and future therapeutic targets. Nat. Immunol. 6, 1182–1190 10.1038/ni1275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang W., Goswami S., Sahai E., Wyckoff J. B., Segall J. E., and Condeelis J. S. (2005) Tumor cells caught in the act of invading: Their strategy for enhanced cell motility. Trends Cell Biol. 15, 138–145 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Siripurapu P., Kankanamge D., Ratnayake K., Senarath K., and Karunarathne A. (2017) Two independent but synchronized Gβγ subunit-controlled pathways are essential for trailing-edge retraction during macrophage migration. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 17482–17495 10.1074/jbc.M117.787838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cook L. A., Schey K. L., Cleator J. H., Wilcox M. D., Dingus J., and Hildebrandt J. D. (2001) Identification of a region in G protein γ subunits conserved across species but hypervariable among subunit isoforms. Protein Sci. 10, 2548–2555 10.1110/ps.ps.26401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lim W. K., Myung C.-S., Garrison J. C., and Neubig R. R. (2001) Receptor-G protein γ specificity: γ11 shows unique potency for A1 adenosine and 5-HT1A receptors. Biochemistry 40, 10532–10541 10.1021/bi010950c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ray K., Kunsch C., Bonner L. M., and Robishaw J. D. (1995) Isolation of cDNA clones encoding eight different human G protein γ subunits, including three novel forms designated the γ4, γ10, and γ11 subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 21765–21771 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bigler Wang D., Sherman N. E., Shannon J. D., Leonhardt S. A., Mayeenuddin L. H., Yeager M., and McIntire W. E. (2011) Binding of β4γ5 by adenosine A1 and A2A receptors determined by stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture and mass spectrometry. Biochemistry 50, 207–220 10.1021/bi101227y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schwindinger W. F., Mihalcik L. J., Giger K. E., Betz K. S., Stauffer A. M., Linden J., Herve D., and Robishaw J. D. (2010) Adenosine A2A receptor signaling and golf assembly show a specific requirement for the γ7 subtype in the striatum. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 29787–29796 10.1074/jbc.M110.142620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saini D. K., Karunarathne W. K. A., Angaswamy N., Saini D., Cho J.-H., Kalyanaraman V., and Gautam N. (2010) Regulation of Golgi structure and secretion by receptor-induced G protein βγ complex translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 11417–11422 10.1073/pnas.1003042107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ajith Karunarathne W. K., O'Neill P. R., Martinez-Espinosa P. L., Kalyanaraman V., and Gautam N. (2012) All G protein βγ complexes are capable of translocation on receptor activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 421, 605–611 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.04.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schwindinger W. F., Mirshahi U. L., Baylor K. A., Sheridan K. M., Stauffer A. M., Usefof S., Stecker M. M., Mirshahi T., and Robishaw J. D. (2012) Synergistic roles for G-protein γ3 and γ7 subtypes in seizure susceptibility as revealed in double knock-out mice. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 7121–7133 10.1074/jbc.M111.308395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hurowitz E. H., Melnyk J. M., Chen Y.-J., Kouros-Mehr H., Simon M. I., and Shizuya H. (2000) Genomic characterization of the human heterotrimeric G protein α, β, and γ subunit genes. DNA Res. 7, 111–120 10.1093/dnares/7.2.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ratnayake K., Kankanamge D., Senarath K., Siripurapu P., Weis N., Tennakoon M., Payton J. L., and Karunarathne A. (2017) Measurement of GPCR-G protein activity in living cells. Methods Cell Biol. 142, 1–25 10.1016/bs.mcb.2017.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. O'Neill P. R., Karunarathne W. K., Kalyanaraman V., Silvius J. R., and Gautam N. (2012) G-protein signaling leverages subunit-dependent membrane affinity to differentially control βγ translocation to intracellular membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E3568–E3577 10.1073/pnas.1205345109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kölsch V., Charest P. G., and Firtel R. A. (2008) The regulation of cell motility and chemotaxis by phospholipid signaling. J. Cell Sci. 121, 551–559 10.1242/jcs.023333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brock C., Schaefer M., Reusch H. P., Czupalla C., Michalke M., Spicher K., Schultz G., and Nürnberg B. (2003) Roles of G βγ in membrane recruitment and activation of p110 gamma/p101 phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ. J. Cell Biol. 160, 89–99 10.1083/jcb.200210115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Braselmann S., Palmer T. M., and Cook S. J. (1997) Signalling enzymes: Bursting with potential. Curr. Biol. 7, R470–R473 10.1016/S0960-9822(06)00239-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Karunarathne W. K., Giri L., Kalyanaraman V., and Gautam N. (2013) Optically triggering spatiotemporally confined GPCR activity in a cell and programming neurite initiation and extension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E1565–E1574 10.1073/pnas.1220697110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Akgoz M., Kalyanaraman V., and Gautam N. (2006) G protein βγ complex translocation from plasma membrane to Golgi complex is influenced by receptor γ subunit interaction. Cell Signal 18, 1758–1768 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roach T. I. A., Rebres R. A., Fraser I. D. C., DeCamp D. L., Lin K.-M., Sternweis P. C., Simon M. I., and Seaman W. E. (2008) Signaling and cross-talk by C5a and UDP in macrophages selectively use PLCβ3 to regulate intracellular free calcium. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 17351–17361 10.1074/jbc.M800907200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Prakash P., Zhou Y., Liang H., Hancock J. F., and Gorfe A. A. (2016) Oncogenic K-ras binds to an anionic membrane in two distinct orientations: A molecular dynamics analysis. Biophys. J. 110, 1125–1138 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Senarath K., Ratnayake K., Siripurapu P., Payton J. L., and Karunarathne A. (2016) Reversible G protein βγ9 distribution-based assay reveals molecular underpinnings in subcellular, single-cell, and multicellular GPCR and G protein activity. Anal. Chem. 88, 11450–11459 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xu Q., and Gunner M. R. (2001) Trapping conformational intermediate states in the reaction center protein from photosynthetic bacteria. Biochemistry 40, 3232–3241 10.1021/bi002326q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Samama P., Cotecchia S., Costa T., and Lefkowitz R. J. (1993) A mutation-induced activated state of the beta 2-adrenergic receptor. Extending the ternary complex model. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 4625–4636 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Thorpe L. M., Yuzugullu H., and Zhao J. J. (2015) PI3K in cancer: Divergent roles of isoforms, modes of activation and therapeutic targeting. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15, 7–24 10.1038/nrc3860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Faenza I., Bavelloni A., Fiume R., Santi P., Martelli A. M., Maria Billi A., Lo Vasco V. R., Manzoli L., and Cocco L. (2004) Expression of phospholipase C beta family isoenzymes in C2C12 myoblasts during terminal differentiation. J. Cell Physiol. 200, 291–296 10.1002/jcp.20001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Adjobo-Hermans M. J. W., Goedhart J., and Gadella T. W. Jr. (2008) Regulation of PLCβ1a membrane anchoring by its substrate phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate. J. Cell Sci. 121, 3770–3777 10.1242/jcs.029785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mahmoud S., Farrag M., and Ruiz-Velasco V. (2016) Gγ7 proteins contribute to coupling of nociceptin/orphanin FQ peptide (NOP) opioid receptors and voltage-gated Ca(2+) channels in rat stellate ganglion neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 627, 77–83 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.05.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Curnock A. P., Logan M. K., and Ward S. G. (2002) Chemokine signalling: Pivoting around multiple phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Immunology 105, 125–136 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01345.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kim S.-H., Turnbull J., and Guimond S. (2011) Extracellular matrix and cell signalling: the dynamic cooperation of integrin, proteoglycan and growth factor receptor. J. Endocrinol. 209, 139–151 10.1530/JOE-10-0377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim D., Kim S., Koh H., Yoon S.-O., Chung A.-S., Cho K. S., and Chung J. (2001) Akt/PKB promotes cancer cell invasion via increased motility and metalloproteinase production. FASEB J. 15, 1953–1962 10.1096/fj.01-0198com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Akgoz M., Kalyanaraman V., and Gautam N. (2004) Receptor-mediated reversible translocation of the G protein βγ complex from the plasma membrane to the Golgi complex. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 51541–51544 10.1074/jbc.M410639200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Saini D. K., Kalyanaraman V., Chisari M., and Gautam N. (2007) A family of G protein βγ subunits translocate reversibly from the plasma membrane to endomembranes on receptor activation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24099–24108 10.1074/jbc.M701191200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.