Abstract

Uncontrolled pain in patients with rib fracture leads to atelectasis and impaired cough which can progress to pneumonia and respiratory failure necessitating mechanical ventilation. Of the various pain modalities, regional anaesthesia (epidural and paravertebral) is better than systemic and oral analgesics. The erector spinae plane block (ESPB) is a new modality in the armamentarium for the management of pain in multiple rib fractures, which is simple to perform and without major complications. We report a case series where ESPB helped in weaning the patients from mechanical ventilation. Further randomised controlled studies are warranted in comparing their efficacy in relation to other regional anaesthetic techniques.

Key words: Analgesia, erector spinae plane block, rib fracture, ventilation

INTRODUCTION

Rib fractures are present in at least 10% of trauma population secondary to road traffic accidents (RTAs).[1] Rib fractures can be isolated or can be seen as a component of polytrauma, with single or multiple ribs fractured at one or more places, resulting in a wide clinical spectrum ranging from asymptomatic patients to respiratory insufficiency necessitating mechanical ventilation. Inadequate analgesia leads to atelectasis, pneumonic consolidation and secondary lung injury. Various modalities of pain management such as oral analgesics, parenteral analgesics, intercostal nerve blocks, interpleural catheters, epidural analgesia and thoracic paravertebral block have been described in the literature, with regional anaesthesia being superior to oral and systemic analgesia.[2] Recently, erector spinae plane block (ESPB) with a catheter has been described for the management of pain in a patient with unilateral rib fracture.[3] We present a case series of two patients where ESPB continuous catheter has been used to provide analgesia and facilitate early extubation in polytrauma with associated rib fractures.

CASE REPORT

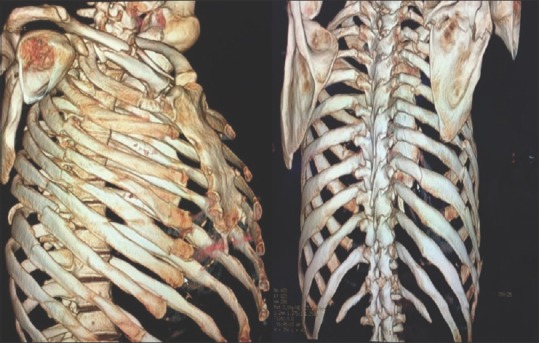

Our first patient was a 52-year-old male who had an RTA. He had sustained fractures of right clavicle, right scapula and the 2nd to 8th ribs on the right side at multiple sites leading to a flail chest [Figure 1]. Due to severe pain (visual analogue scale [VAS] 9/10), he had restriction of chest movements and impaired ventilation. Hence, his trachea was intubated and lungs were ventilated. He had a moderate pneumothorax for which an intercostal drainage tube was inserted. He was electively posted for right clavicle fixation under general anaesthesia.

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional reconstructed image of rib fractures

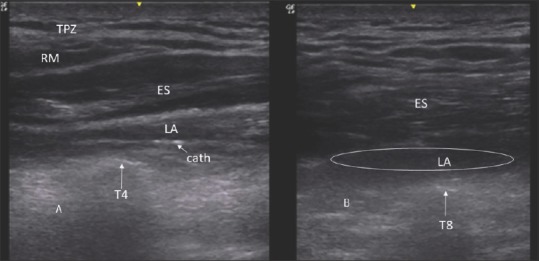

ESPB was planned for post- procedural analgesia. Prior to emergence from general anaesthesia, the patient was positioned in the right lateral position, the right hemithorax was prepared with 2% chlorhexidine in 70% alcohol solution, and using a 10–15 MHz ultrasound probe, the transverse process of the 4th thoracic vertebra was identified. Muscle layers of trapezius, rhomboids major and erector spinae were identified, and the fascial plane beneath the erector spinae muscle was entered with a 17G Tuohy needle. A volume of 10 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine was injected and the spread of local anaesthetic was observed in a shape resembling a Kayak. Through the needle, a 19 G multi-orifice catheter was inserted and placed in the fascial plane and its position was confirmed by injecting 5 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine [Figure 2]. Under ultrasound guidance, the transverse process of the 8th thoracic vertebra was identified and confirmed by identifying only erector spinae muscle layer above the transverse process. An ESPB catheter was placed in the same technique described above. Both the catheters were fixed in position and secured. Post-procedure, the patient was shifted back to the Intensive Care Unit with ventilator support and sedation. Eight hours after the procedure, the patient was weaned off the ventilator and his trachea was extubated and respiration was supported by non-invasive ventilation for the first 24 h in the Intensive Care Unit followed by oxygen through a face mask for the next 2 days in the ward. The extent of sensory blockade post-extubation was from T2 to T10 for cold sensation. The patient received intermittent boluses of 0.2% ropivacaine (15 ml into each of the catheters) twice a day for 4 days. The patient was comfortable with pain score in the range of 2–3/10 on the VAS. Intravenous paracetamol and tramadol were prescribed as rescue analgesics when the VAS was >4. He had received two doses of rescue analgesics 48 h post-extubation and performed deep breathing exercises and chest physiotherapy with ease. The patient did not have pain while at rest, deep breathing or coughing and was able to maintain oxygen saturation without oxygen supplementation on the 6th post-operative day. He was discharged from the hospital on the 9th post-operative day.

Figure 2.

Ultrasound image of the erector spinae plane block (a) Level of T4. Arrow indicates T4 transverse process. TPZ – Trapezius muscle; RM – Rhomboid major; ES – Erector spinae; LA – Local anaesthetic, Cath – Catheter. (b) Level of T8. Arrow indicates T8 transverse process. ES – Erector spinae; LA – Local anaesthetic. LA is in the shape of Kayak

Our second patient was a 46-year-old lady who had sustained multiple rib fractures from the 2nd to the 6th rib along with forearm fracture on the same side. Her respiration was supported by non-invasive ventilation due to pain (VAS 9–10) and ineffective cough. Following the fixation of her forearm under general anaesthesia, ESPB with a catheter at T5 level was placed. She was weaned off the ventilator and extubated on the subsequent day with a pain score of VAS 1–2. Intravenous paracetamol and tramadol were prescribed as rescue analgesics when the VAS is >4. The level of sensory block assessed post-extubation was from T2 to T7 for cold sensation. She received three doses of rescue analgesics 48 h post-extubation and performed deep breathing exercises and chest physiotherapy with ease.

DISCUSSION

Thoracic epidural analgesia and paravertebral techniques are the two commonly employed techniques to provide analgesia in patients with multiple rib fractures.[4] Technical difficulty and associated hypotension preclude the usage of epidural over paravertebral blockade. The disadvantage of paravertebral technique is that it can only be used for unilateral fractures, along with chances of epidural drug spread and difficulty in threading the catheters.[2]

ESPB is a relatively new technique. Cadaveric and limited clinical data suggest that the spread of local anaesthetics may not be uniform; hence when 6 or more ribs are fractured, placing two catheters in the ESPB can allow us to provide pain relief in a wider area of the chest wall. ESPB is a simple block in terms of easy identification of landmarks with ultrasound and safe block with no neurovascular structures in the ESP.[5,6,7] Furthermore, it avoids the complications of other regional techniques (hypotension of epidural analgesia, epidural spread and vascular puncture of paravertebral block, local anaesthetic toxicity and pneumothorax of intercostal nerve and interpleural block). The clinical utility of this block (ESPB) in comparison with epidural or paravertebral blocks for pain relief in rib fractures needs to be confirmed in a larger randomised controlled trial.

CONCLUSION

ESPB may be an alternative to epidural or thoracic paravertebral block for providing analgesia in patients with multiple rib fractures. It provides pain relief, allows the patients to cough and helps in weaning off mechanical ventilation with a negligible risk.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ziegler DW, Agarwal NN. The morbidity and mortality of rib fractures. J Trauma. 1994;37:975–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199412000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho AM, Karmakar MK, Critchley LA. Acute pain management of patients with multiple fractured ribs: A focus on regional techniques. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17:323–7. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328348bf6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamilton DL, Manickam B. Erector spinae plane block for pain relief in rib fractures. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118:474–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrier FM, Turgeon AF, Nicole PC, Trépanier CA, Fergusson DA, Thauvette D, et al. Effect of epidural analgesia in patients with traumatic rib fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Anaesth. 2009;56:230–42. doi: 10.1007/s12630-009-9052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chin KJ, Adhikary S, Forero M. Is the erector spinae plane (ESP) block a sheath block? A reply. Anaesthesia. 2017;72:916–7. doi: 10.1111/anae.13926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forero M, Adhikary SD, Lopez H, Tsui C, Chin KJ. The erector spinae plane block: A novel analgesic technique in thoracic neuropathic pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016;41:621–7. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chin KJ, Adhikary S, Sarwani N, Forero M. The analgesic efficacy of pre-operative bilateral erector spinae plane (ESP) blocks in patients having ventral hernia repair. Anaesthesia. 2017;72:452–60. doi: 10.1111/anae.13814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]