Abstract

Introduction

Patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) have a poor prognosis and limited treatment options. Since access to longitudinal tumor samples is very limited in patients with this disease, we chose to focus our studies on the characterization of plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA) for rapid, noninvasive monitoring of disease burden.

Methods

We developed a liquid biopsy assay that quantifies somatic variants in cfDNA. The assay detects single nucleotide variants, copy number alterations, and insertions or deletions in 14 genes that are frequently mutated in SCLC, including TP53, RB1, BRAF, KIT, NOTCH1–4, PIK3CA, PTEN, FGFR1, MYC, MYCL1, and MYCN.

Results

Over 26 months of peripheral blood collection, we examined 140 plasma samples from 27 patients. We detected disease-associated mutations in 85% of patient samples with mutant allele frequencies (AFs) ranging from ≤0.1% to 84%. In our cohort, 59% of the patients had extensive stage disease, and the most common mutations occurred in TP53 (70%) and RB1 (52%). In addition to mutations in TP53 and RB1, we detected alterations in 10 additional genes in our patient population (PTEN, NOTCH1–4, MYC, MYCL1, PIK3CA, KIT, and BRAF). Observed AFs and CNAs tracked closely with treatment responses. Notably, in several cases analysis of cfDNA provided evidence of disease relapse before conventional imaging.

Conclusions

These results suggest that liquid biopsies are readily applicable in patients with SCLC and can potentially provide improved monitoring of disease burden, depth of responses to treatment, and timely warning of disease relapse in patients with this disease.

Keywords: Small cell lung cancer (SCLC), cell-free tumor DNA, liquid biopsy, next generation sequencing, plasma

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States and among the leading causes of cancer-related death worldwide1. Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is an aggressive lung cancer of neuroendocrine origin with a propensity for early and extensive metastatic dissemination. SCLC accounts for ~15% of all lung cancers and ~30,000 deaths in the United States annually2. The median overall survival (OS) for SCLC patients is approximately 8–12 months for patients with extensive stage disease and 12–20 months for patients with limited stage disease2. Standard chemotherapy regimens for SCLC have not changed for over 30 years3,4. While SCLC is initially sensitive to conventional platinum doublet chemotherapy, resistance to chemotherapy rapidly develops5. The combination of elusive pathophysiology, poor prognosis, and a lack of therapeutic improvement for several decades has led the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to designate SCLC a recalcitrant cancer6.

Recent studies in this disease have revealed a complex and heterogeneous genomic landscape that is associated with tobacco exposure7,8. Biallelic inactivation of the tumor suppressors, TP53 and RB1, are detected in the majority of SCLC tumors. In addition to these molecular ‘hallmarks’, other genomic variants have been detected at lower frequencies, including amplification of MYC, MYCL1, MYCN, and FGFR, PTEN loss, and activating mutations in PIK3CA, BRAF and the four NOTCH gene paralogs7–9. In addition, a high mutation rate of 7.4 ± 1 protein-changing mutations per million base pairs has been detected in this tumor10. Although many of these genomic alterations could be viewed as potential therapeutic targets, tumor molecular profiling and personalized treatments directed towards oncogenic driver mutations have not yet proven effective in SCLC.

There is an acute need for advances in effective care and treatment of patients with SCLC. Recently, clinical studies using novel therapeutic approaches for SCLC have been reported11–13. In the setting of either conventional treatment or clinical trial research, patients may benefit from access to “real-time”, highly-sensitive monitoring of disease burden. Such information can potentially provide early insight into treatment efficacy, the likelihood of benefit of life-extending procedures, recurrence of disease, and end-of-life decision making. The current standard of care is cross-sectional imaging. While imaging is an essential clinical tool, it cannot detect occult disease or treatment-induced changes in tumor genotypes.

A significant obstacle to advancing translational SCLC research has been the difficulty in obtaining tumor material. Surgical resections are rare in this disease, and tumor biopsies are often of small size and poor quality14. In addition, unlike non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), biopsies of recurrent SCLC are rarely performed, which makes serial analysis of tumor evolution throughout chemotherapy difficult. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop novel methods to obtain SCLC samples in order to fully assess genomic changes in this malignancy.

Here, we describe the development of a liquid biopsy assay for serial monitoring of SCLC-derived cfDNA. Implementation of the assay across a cohort of 27 patients with SCLC revealed a diversity of disease genotypes and dynamic changes in cfDNA allele fraction over the course of treatment.

Methods

Study design and patients

Patients with SCLC were prospectively identified and consented using an Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved protocol for collection of blood plus clinical information and treatment history. All samples were de-identified and protected health information was reviewed according to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) guidelines.

Blood samples and cell free DNA isolation

Blood samples (10–20 mL) were collected in Streck™ tubes (Streck, Omaha, NE) at various time points prior to, during, and after therapy. Blood was centrifuged at 1200 × g for 30 min. Plasma was removed and re-centrifuged at 500 × g for 30 min and immediately aliquoted and stored at −80°C. DNA was extracted from patient plasma samples with Circulating Nucleic Acids Extraction kit following the manufacturer’s instruction except samples were incubated with proteinase K for one hour rather than 30 min (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The yield of double-strand DNA was quantified using a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) and the corresponding high sensitivity DNA quantification kit. Approximately 40 – 100 ng of cfDNA, depending on the yield of cfDNA from the sample, was used for library construction.

Targeted NGS

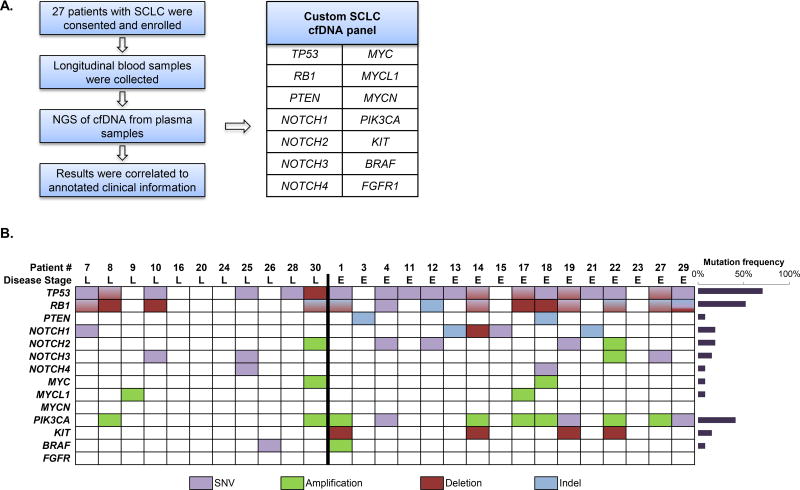

A detailed description of the platform utilized for cfDNA sequencing is described in the Supplementary Methods which accompany this text. Briefly, the panel (Fig. 1A) contains 1608 probes that target all coding exons of BRAF, KIT, NOTCH1–4, PIK3CA, PTEN, RB1 and TP53. The panel also contains probes for copy variation detection in the genes FGFR1, MYC, MYCL1 and MYCN and control probes that target select regions in all 22 autosomes.

Figure 1. Mutational analysis in plasma cfDNA from 27 patients using next-generation sequencing.

(A) Study overview.

(B) Summary of mutations identified by individual patients at any time point. Patients are separated by stage of disease at diagnosis (L: limited stage; E: extensive stage). Alterations are color coded per the figure legend below the image. The mutation frequencies for each gene are plotted on the right panel.

Statistical analysis

The overall survival (OS) was defined from the date of diagnosis to the date of death from any cause or the last follow-up date (data cutoff: February 8, 2017). Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess the association between OS and cfDNA levels, which were measured as genomic equivalents in plasma. For each patient, multiple cfDNA levels were measured over time and included as a time-dependent covariate in all models. One-year survival was estimated from the univariate model. Hazard ratios (HR) for every one-fold increase in cfDNA genomic equivalents with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported for both univariate and multivariable models. Disease stage and treatment status were a priori selected, based on clinical knowledge, to be controlled in the multivariate models.

Results

Disease-associated variants are detected at high frequency in SCLC plasma samples

Over approximately 26 months of peripheral blood collection, we obtained 140 samples from 27 patients with SCLC. Most patients had multiple samples collected (25/27, 93%), with a range of 1–12 collections per patient. The majority of the 27 patients had extensive stage (ES) SCLC (59%), the median age was 66 years, and 52% were women (Table 1). Individual patient information with treatment details are listed in Table S1.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of patients in this study (n=27).

| Patient Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age | Median | 66 years |

| Range | 40–86 years | |

|

| ||

| Gender | Male | 13 (48%) |

|

| ||

| Female | 14 (52%) | |

|

| ||

| Smoking history | Yes | 25 (93%) |

|

| ||

| No | 2 (7%) | |

|

| ||

| Stage of disease at initial diagnosis | Limited | 11 (41%) |

|

| ||

| Extensive | 16 (59%) | |

|

| ||

| Systemic Therapy | First line treatment | 27 (100%) |

|

| ||

| Second line treatment | 14 (52%) | |

|

| ||

| Third line treatment | 7 (26%) | |

|

| ||

| Fourth line treatment | 2 (7%) | |

For serial monitoring of circulating tumor burden, we applied a hybrid-capture next generation sequencing (NGS) technology specifically designed for quantitative analysis of somatic alterations in cfDNA (Supplementary Methods). We developed a custom capture panel that targets 14 genes known to be frequently mutated in SCLC tumors7–10 (Fig. 1A). We detected disease-associated mutations in peripheral blood from 23 patients (85%) (Fig. 1B), with an allele frequency (AF) range of ≤0.1% to ≥84%. Six or more genomic alterations were detected in eight of 27 (30%) of patients. A total of 82 of 140 (59%) plasma samples analyzed had detectable somatic mutations. Significantly, 35 of the 58 (60%) mutation-negative samples were from patients whose somatic alterations dropped to undetectable levels in response to therapy (Table S1 and Table S2). Notably, in cases where pretreatment plasma samples were available, the cfDNA somatic mutation signature in patients that experienced disease relapse was identical to the pretreatment profile.

The most common disease-associated mutations were detected in TP53 (19/27 patients, 70%) and RB1 (14/27 patients, 52%). Fourteen patients (52%) had detectable mutations in both TP53 and RB1. In addition to mutations in TP53 and RB1, we detected alterations in 10 additional genes in our patient population (PTEN, NOTCH1–4, MYC, MYCL1, PIK3CA, KIT, and BRAF; Fig. 1B). Fourteen of 27 (52%) patients had inactivating mutations in NOTCH family genes, and 4 of 27 (15%) patients had genomic amplifications of a MYC family member. Copy number alterations (CNAs) included amplifications in NOTCH2, NOTCH3, MYC, MYCL1, PIK3CA, and BRAF and deletions in TP53, RB1, NOTCH1, and KIT. In total, 91 alterations in 12 genes, including 42 single nucleotide variants (SNVs), 39 CNAs, and 10 insertion/deletions (indels) were detected.

cfDNA tracking is now being used as standard of care in the management of certain genotypes of NSCLC15. Since TP53 mutations are commonly found in both NSCLC16,17 and SCLC7,8,10, we compared mutant AFs between these two types of lung cancer. We analyzed plasma samples from 43 patients with metastatic NSCLC with known TP53 mutations, and compared the AFs of TP53 mutations to the SCLC patients in our cohort. The observed AFs were significantly higher for SCLC (range of 0.45–70.4% in SCLC versus 0.4–36.9% in NSCLC; p= 0.006, Fig. S1).

Longitudinal cfDNA analysis identifies disease recurrence prior to radiographic evidence of tumor progression

To determine if cfDNA sequencing can be used to monitor a patient’s response to systemic therapy, we analyzed serial plasma samples from 25 patients prior to, during, and after therapy. We detected a marked increase in mutation abundance that preceded radiographic evidence of disease progression in 9 patients (VSC-4, VSC-8, VSC-10, VSC-11, VSC-12, VSC-13, VSC-25, VSC-27, and VSC-29). Two representative examples of how changes detected in cfDNA preceded radiographic progression of disease during a patient’s clinical course are highlighted below (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3), and the remaining case descriptions are included in Figs. S2–S5 and Table S2.

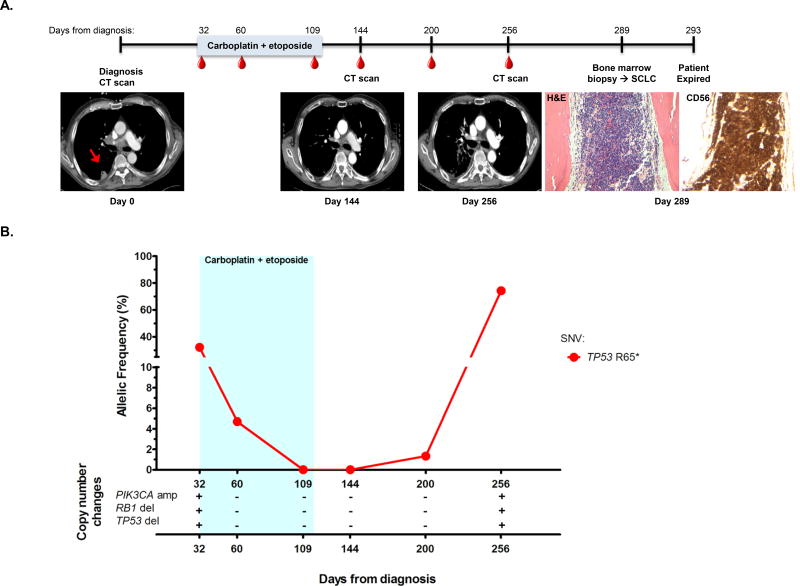

Figure 2. cfDNA detection precedes clinical or radiographic disease progression.

(A) The timeline for patient VSC-8’s clinical course from diagnosis until date of death is shown. The light blue colored bar represents the treatment timeframe, and the red dots indicate blood collections. Radiographic images were acquired at the time of diagnosis, day 144, and day 256. The red arrow in the first CT scan shows the right pleural based primary tumor which resolved on further imaging. Bone marrow biopsy was performed on day 289 and assessed for common SCLC markers, including CD56 (H&E, 200× and CD56 staining, 200×).

(B) Percent mutant allelic frequency and copy number alterations for patient VSC-8 are shown. The light blue box indicates treatment timeframe. A plus or minus symbol (+/−) indicates presence/absence of the copy number alteration listed. * = stop. amp = amplification. del = deletion.

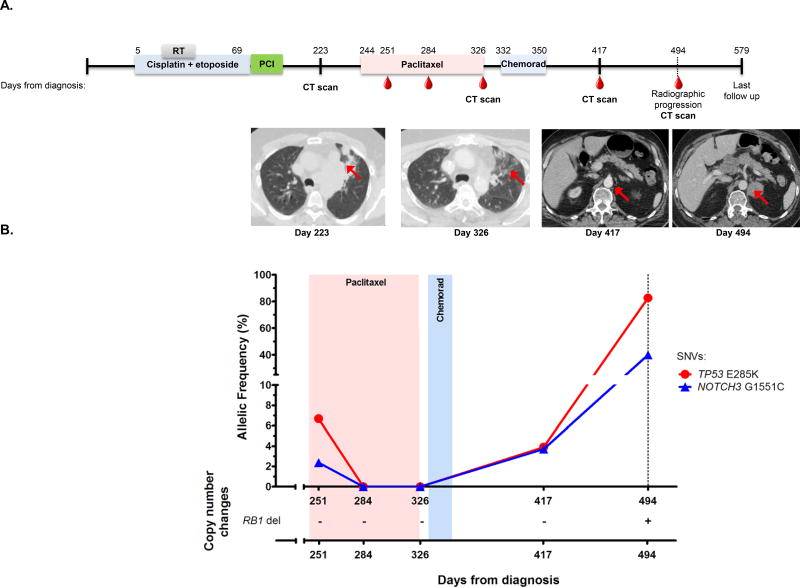

Figure 3. cfDNA detection can clarify mixed response on imaging.

(A) The timeline for patient VSC-10’s clinical course from diagnosis until last follow up date with radiographic images is shown. The colored bars represent the active treatment timeframes, including radiotherapy. The "RT" grey bar indicates radiation therapy, the “PCI” purple bar indicates prophylactic cranial irradiation, and the "chemorad" blue shaded bar represents concurrent chemoradiation with weekly carboplatin and paclitaxel. The red dots indicate blood collection time points. Radiographic images were obtained at time of progression after first line therapy (day 223), day 326, day 417, and day 494. The red arrow at day 223 indicates initially multifocal pulmonary parenchymal disease which resolved after second line paclitaxel (day 326). The subsequent image at day 417 shows a 0.9 cm retroperitoneal lymph node of uncertain etiology. On the day 494 images, the retroperitoneal lymph node enlarged to 3.0 × 2.7 cm.

(B) Percent mutant allelic frequencies and copy number alterations for patient VSC-10 are shown. The light red and blue boxes indicate treatment time periods corresponding to labeling on the timeline above. The dotted line indicates the time of radiologic recurrence. A plus or minus symbol (+/−) indicates presence/absence of the copy number alteration listed. del = deletion.

Patient VSC-8 was diagnosed with limited stage SCLC (LS-SCLC) (Fig. 2A). Prior to initiation of first line chemoradiotherapy with carboplatin and etoposide (day 32), we detected a TP53 (R65*) SNV at 32.2% AF, a PIK3CA amplification (4.0 copies), and a copy number loss in both TP53 and RB1 (Fig. 2B). After one cycle (day 60), the TP53 (R65*) mutation AF decreased to 4.7% and the copy number changes in PIK3CA, TP53 and RB1 were no longer detectable. Repeat cfDNA assessments after the third and fourth cycles (day 109 and 144, respectively) of first line therapy detected no somatic mutations (Fig. 2B), and imaging after completion of the fourth cycle showed a partial response (Fig. 2A, day 144 image). Eight weeks after completion of first line therapy (day 200), cfDNA analysis showed recurrence of the TP53 (R65*) mutation at an AF of 1.3%, but imaging showed an excellent response in pulmonary parenchymal disease and hilar adenopathy with ambiguous, subcentimeter adrenal nodularity, and no clear radiographic progression (data not shown). At day 256 following diagnosis, the AF of the TP53 (R65*) mutation increased to 74% (>2 fold higher than at initial diagnosis), the PIK3CA amplification (3.0 copies) reappeared, and deletions in TP53 and RB1 were again detected. Imaging continued to show ambiguous findings in the post-radiation field (Fig. 2A, day 256 image), and 33 days later, with clinical worsening and the development of pancytopenia, progression become apparent when a bone marrow biopsy showed involvement by SCLC (Fig. 2A, images at day 289). This patient did not have a pre-treatment bone marrow biopsy as he had mild anemia but no other cytopenias at the time of diagnosis. In this case, cfDNA testing captured disease progression that was not seen on computed tomography imaging.

cfDNA testing may clarify ambiguous radiographic findings and detect occult disease

While the previous case highlights disease progression in an occult anatomic location detected by peripheral blood cfDNA, many times disease progression on imaging is difficult to discern from treatment effects, infection, or inflammatory changes. In these cases, more information is needed before patients are subjected to changes in therapy. Currently, additional time with repeat imaging is the standard approach, but cfDNA monitoring has the potential to add valuable insight in these cases with ambiguous imaging findings as noted in the ensuing case.

Patient VSC-10 was initially diagnosed with LS-SCLC and received first line chemoradiotherapy (cisplatin and etoposide) with a partial response. At day 223 post diagnosis, local recurrence of the tumor was noted on CT scan (Fig. 3A, day 223 image) and confirmed with supraclavicular lymph node biopsy, and second line therapy with paclitaxel was initiated. One week after initiating second line treatment (day 251), we detected alterations in TP53 (E285K) and NOTCH3 (G1551C) at 6.7% and 2.4%, respectively (Fig. 3B). The patient achieved a complete response with second line therapy (Fig. 3A, day 326 image), and cfDNA analysis 6 weeks (day 284) and 13 weeks (day 326) after initiation of second line therapy detected no tumor associated alterations. However, nearly six months after initiating second line therapy (day 417) the patient’s same disease-associated mutations reappeared (TP53 E285K at 3.9% and NOTCH3 G1551C at 3.7%). Cross-sectional imaging at this time (Fig. 3A, day 417 image) showed no demonstrable tumor recurrence and in fact, there was an interval decreased size of lung nodules compared to previous scan and a small (0.9cm) left retroperitoneal lymph node that was of uncertain etiology. Repeat cfDNA analysis on day 494 revealed a >20 fold increase in TP53 mutant AF (E285K at 82.6%) and a >10 fold increase in NOTCH3 mutant AF (G1551C at 39.9%). Surveillance imaging on day 494 revealed massive, intra-abdominal disease (Fig. 3A, day 494 image). The left retroperitoneal lymph node now measured 3.0 × 2.7 cm. There was also a new 5.9 × 4.5 × 4.1 cm hepatic metastasis, diffuse intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy, and new pleural based metastases (data not shown). This case illustrates an example where liquid biopsy testing was a valuable diagnostic companion to imaging in surveillance for disease recurrence. Similar observations were made in four additional cases (VSC-1, VSC-7, VSC-12, and VSC-13); Figs. S4, S6–7 and Table S2, respectively).

Serial cfDNA analysis could be used to refine treatment intensity

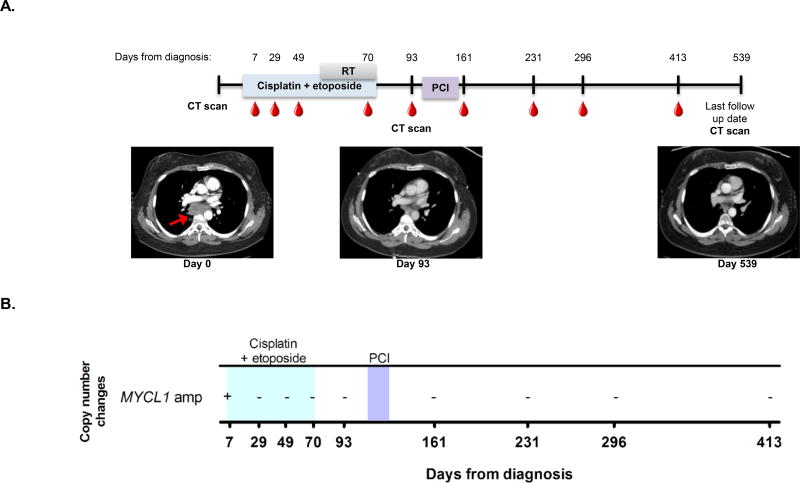

Prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) after first-line chemotherapy is the standard of care for patients with limited stage SCLC18,19. Detection of tumor-associated mutations in cfDNA could potentially be used to identify patients most likely to benefit from PCI while sparing other patients from the toxicities associated with whole brain radiotherapy. The case of patient VSC-9, a 40 year old female with LS-SCLC, illustrates this point (Fig. 4A). Profiling of the patient’s cfDNA prior to first line chemoradiotherapy revealed a MYCL1 amplification (15.5 copies; Fig. 4B). Following treatment with cisplatin and etoposide, this amplification fell to undetectable levels in all serial samples collected up to 413 days after diagnosis (Fig. 4B), suggesting that the patient had platinum-sensitive disease. CT imaging after treatment completion (Fig. 4A, day 93 image) and 15 months after completion of therapy (Fig. 4A, day 539 image) also showed no evidence of disease. Although both CT imaging and cfDNA testing showed complete response to chemotherapy, the patient still received PCI (Fig. 4A, days 112–126 after diagnosis) as standard of care to attempt to prevent brain metastases. In such cases, the absence of detectable ctDNA could add a piece of information that would allow a discussion regarding the likelihood of CNS recurrence and potential impact of PCI. Two other patients in our cohort had similar clinical scenarios with persistent clearance of tumor-associated variants following treatment (Figs. S8–9). None of these patients has had disease recurrence at most recent follow-up 13, 20, and 21 months following diagnosis. At this time, we do not have sufficient data to confidently state the concordance between systemic disease control and intracranial disease control in SCLC patients when cfDNA analysis is negative.

Figure 4. cfDNA changes correspond to remission.

(A) The timeline for patient VSC-9’s clinical course from diagnosis until last follow up date with radiographic images is shown. The colored bars represent the treatment timeframes. The "RT" grey bar indicates radiation therapy and the "PCI" purple bar indicates prophylactic cranial irradiation. Radiographic images were obtained at time of diagnosis, day 93, and at last follow up date (day 539). The red arrow shows primary mediastinal disease which resolved on subsequent imaging.

(B) Copy number alterations for patient VSC-9 are shown. The blue box indicates the time period during which cisplatin plus etoposide was administered and the purple box indicates prophylactic cranial irradiation treatment. A plus or minus symbol (+/−) indicates presence/absence of the copy number alteration listed. amp = amplification.

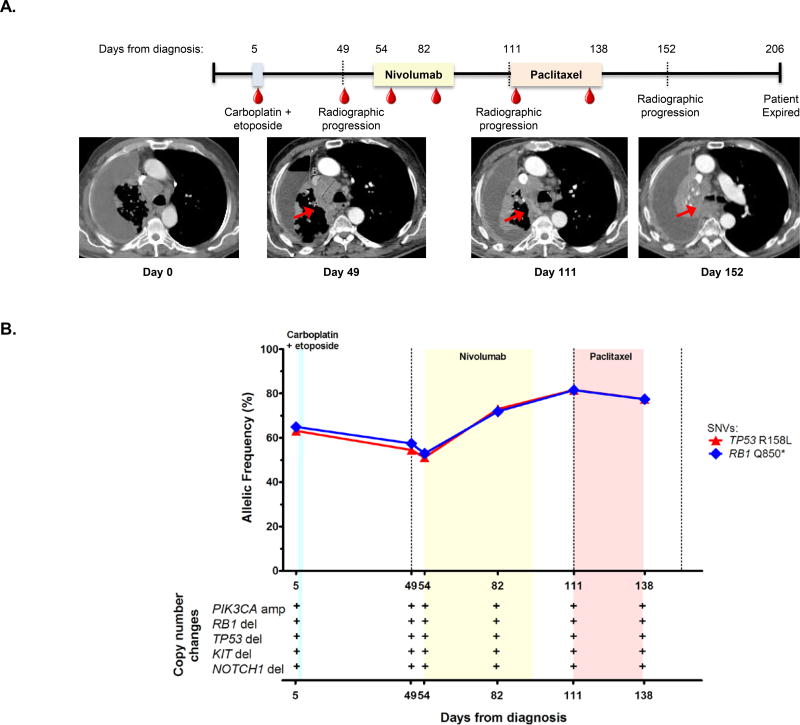

In several patients, cfDNA mutation tracking provided early evidence of resistance to therapy (VSC-1, VSC-12, VSC-14, VSC-18, VSC-27, Fig. 5A–B, Figs. S2, S4, S7, S10). In all these cases, we noted an obvious rise in mutation abundance during treatment. For instance, patient VSC-14, with ES-SCLC, enrolled prior to first line therapy with carboplatin and etoposide (Fig. 5A). We detected two somatic mutations in TP53 (R158L) and RB1 (Q850*) at AFs of 63.1% and 64.9%, respectively, deletions in KIT, TP53, RB1, and NOTCH1, and a PIK3CA amplification (Fig. 5B). The patient did not tolerate the first cycle of carboplatin/etoposide, and repeat cfDNA assessment six weeks after treatment initiation (day 49) revealed the same genomic alterations with TP53 (R158L) and RB1 (Q850*) mutations at AFs of 54.5% and 57.4%, respectively. Imaging revealed ongoing progression of disease at this time, with abdominal adenopathy, pleural, and adrenal metastases slightly increasing in size (Fig. 5A, day 49 image). One week later, the patient began nivolumab, and cfDNA revealed TP53 (R158L) and RB1 (Q850*) mutations at AFs of 51.0% and 52.9%, respectively. One month after initiating nivolumab (day 82), cfDNA revealed AFs of TP53 (R158L) at 73.0% and RB1 (Q850*) at 71.9%, before response imaging was obtained. Eight weeks after initiating nivolumab (day 111), AFs continued to increase to TP53 (R158L) at 81.6% and RB1 (Q850*) at 81.4%, and imaging showed diffuse, progressive disease throughout the thorax and abdomen (Fig. 5A, day 111 image). The patient started third line therapy with paclitaxel, and one month after therapy initiation (day 138), cfDNA revealed AFs of TP53 (R158L) at 77.5% and RB1 (Q850*) at 77.3%. The patient progressed on imaging two weeks later (Fig. 5B, day 152 image), no cfDNA was assessed at that time, and the patient clinically declined and died seven weeks later. In this patient’s case, peripheral blood cfDNA AFs continued to increase while on nivolumab and paclitaxel therapy, in both cases prior to repeat imaging. Early identification of non-responders with cfDNA monitoring could alleviate unnecessary toxicity and promote timely changes of therapy.

Figure 5. cfDNA sequencing enables early identification of treatment refractory disease.

(A) The timeline for patient VSC-14’s clinical course from diagnosis until date of death is shown with radiographic images from diagnosis, day 49, day 111, and day 152, demonstrating slow progression in intrathoracic disease despite all therapy. Red arrow indicates primary mediastinal disease. The color bars represent treatment timeframes. The blue color bar represents one cycle of carboplatin and etoposide treatment, the light yellow box represents nivolumab treatment, and the pink box indicates paclitaxel treatment.

(B) Percent mutant allelic frequencies and copy number alterations for patient VSC-14 are shown. The light blue, yellow and pink boxes indicate treatment time periods corresponding to labeling on the timeline above. The dotted line indicates the time of radiologic recurrence. A plus or minus symbol (+/−) indicates presence/absence of the copy number alteration listed. * = stop. amp = amplification. del = deletion.

Prognostic value of cfDNA levels in SCLC

We assessed whether cfDNA levels, measured as genomic equivalents (GEs) in plasma, had prognostic significance. Increased cfDNA GEs was associated with worse overall survival in both univariate analysis (HR = 2.65, 95% CI 1.41–4.98, P = .0024) and multivariate analysis (HR=2.73, 95% CI 1.27–5.86, P=.0099) (Table S3). The predicted one year survival followed a stepwise pattern based on GEs detected in our cohort. For patients with cfDNA GEs of 2000 (median for the overall cohort=2044), one year survival was 90%. For patients with cfDNA GEs of 4000, 6000, 8000, 12,000, and 16,000, one year survival probabilities were 75%, 60%, 47%, 26%, and 13%, respectively. The genomic equivalents and cfDNA concentrations for all patients in our cohort across all collection dates are provided in Table S4.

Discussion

The results from our study confirm that SCLC-associated cfDNA is detectable in peripheral blood in over 80% of patients using our custom, SCLC-specific gene panel. This tumor-associated peripheral blood biomarker detection rate is analogous to the more labor-intensive strategy of isolating circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in patients with SCLC20–22. Furthermore, cfDNA appears to have a higher sensitivity compared to CTCs when compared across multiple histologies, a finding that suggests these markers may have unique pathologic significance23. Moreover, we demonstrate that cfDNA monitoring in patients with SCLC has the potential to be a useful clinical tool. Specifically, we show that tracking of cfDNA mutation abundance was able to detect disease recurrence and occult disease that were not evident with radiographic imaging. Earlier detection may provide relatively fit patients with secondary treatment options. We found that some patients had lasting responses, and these patients may benefit from forestalling potentially toxic procedures, such as PCI. Other patients showed little response to therapy and in these cases palliative care may be preferable to the possible harms of ineffective treatments. Finally, as new therapeutic options are tested in clinical trials, we believe that cfDNA assessment can provide early insight into treatment efficacy.

Broad clinical implementation of liquid biopsies in SCLC patient care is a realistic goal. The gene panel used in this study had fourteen genes that have been found to be frequently mutated in SCLC tumors7–10. It was designed to monitor disease in the circulating DNA of SCLC patients by quantifying SCLC-associated somatic variants that are at potentially low AFs through sequencing of high-coverage genomic libraries. In fact, the AFs of circulating somatic mutations in patients were much higher than in other forms of lung cancer (Fig. S1). This finding may indicate increased tumor shed in SCLC compared to NSCLC, although other factors – specifically, the extent of metastatic disease – need to be considered. The high signal-to-noise ratio observed in this study suggests that routine cfDNA monitoring in this disease setting is technically feasible. The modest breadth of the gene panel translates into a sequencing cost which may be economically feasible as well. Our immediate objective is to evaluate potential benefits to SCLC patients in prospective studies where molecular analysis is included in patient care.

The canonical mutations in patients with SCLC are alterations in TP53 and RB17–10. In studies of tumor tissue predominantly from patients with LS-SCLC prior to first line chemotherapy, TP53 mutations were identified in 80–95% of patients and RB1 mutations were identified in 35–70% of patients7–10. In our study of cfDNA in predominantly patients with ES-SCLC after initiation of systemic chemotherapy, detection rates of TP53 and RB1 mutations were 70% and 52%, respectively. These rates are similar to the previously presented rates of 70% and 32%, respectively, detected in peripheral blood in a cohort of patients with SCLC24. The differences in TP53 and RB1 mutation rates may relate to differences in extent of disease, timing of recent therapy, and/or partial shedding of tumor cfDNA into circulation. Also, RB1 mutations are likely under-reported in our analysis since RB1 is frequently deleted in SCLC7 and somatic deletion events are difficult to detect at low AFs.

Despite the fact that our monitoring panel was not designed to discover novel mutational profiles, we observed a higher than anticipated mutation rate in NOTCH genes7. Our results are more similar to a smaller study in which 54% of patient tumors were found to have mutations in NOTCH genes9. The broad spectrum of mutational events in the NOTCH family is consistent with the proposed tumor suppressive role of NOTCH gene function in this disease9,10. The discrepancy may be due to the fact that the NOTCH coding regions are G/C rich sequences that can be difficult to sequence. Consistent with this idea, the same study that showed a 25% mutation rate in NOTCH genes showed that 77% of tumors had an expression profile consistent with NOTCH inactivation7. Future studies are likely to focus on clinically actionable aspects of NOTCH gene loss in SCLC.

The clinical implications of the co-occurrence of the tumorigenic mutations we identified necessitate further study. For example, murine models of SCLC have shown that co-occurrence of TP53 and RB1 mutations with MYC amplification may predispose to sensitivity to aurora kinase inhibition25. Further connections between the hallmark genomic changes in SCLC and additional pathogenic mutations we have identified must be carefully recorded to identify molecular patterns that may prove particularly susceptible to novel therapies.

There are several limitations to this work. First, our study included a relatively small number of peripheral blood samples from patients at the time of initial diagnosis (that is, treatment naïve patients). This may be partially accounted for by the fact that some patients receive first-line therapy in the community and then are referred to an academic medical center for second-line therapy and beyond. Second, we were not able to obtain blood samples from every patient prior to cross-sectional imaging, which limited our ability to detect occult disease. Some patients did not have blood draws in between imaging studies, and since we only obtained research samples when blood was being drawn as part of standard of care, this may explain why we were not able to capture blood in between imaging studies for all patients in our cohort. While the variable blood collection timing and absence of a control group limit the rigor of the current analysis, we feel the data is of importance for the burgeoning field of cfDNA analysis in patients with SCLC. Third, sample size of our patient cohort precluded statistical subgroup analyses. Finally, it must be noted that the peripheral blood cfDNA assay we used is one among several commercially available options, all of which continue to necessitate prospective investigation regarding their ability to improve patient outcomes26.

While cfDNA identification technique and cutoff values for statistical analysis have varied widely in patients with NSCLC, this is the only recent cfDNA analysis to be linked to clinical outcomes in patients with SCLC27, allowing for a more uniform standard to be applied in replicating this observation in future studies. The uniquely longitudinal data provided in our analysis sets the stage for future studies of peripheral blood cfDNA as an early predictor of disease progression in patients with SCLC, similar to the conceptual application of cfDNA in patients with breast cancer28,29, melanoma30, and colon cancer31. The optimal frequency of peripheral blood cfDNA monitoring in patients with SCLC (every two weeks, four weeks, etc.) needs validation in future prospective studies. We propose a randomized controlled trial comparing standard of care management of patients with SCLC to standard of care plus peripheral blood cfDNA monitoring to detect early relapse and need for therapy re-initiation or change. Due to the aggressive nature of SCLC and current limitations in treatment options for this patient population, better lead-time information predicting progression is of unclear clinical benefit, but we hypothesize that clinical outcomes in patients with SCLC may be improved by detecting and treating disease relapse sooner than is currently possible with conventional imaging. We do not advocate following cfDNA in all patients with SCLC as standard of care at this time, rather we feel that additional prospective analyses we have proposed are still required to ensure this novel technology is best-applied to clinical decision making.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that quantitative changes in cfDNA levels correlated with responses to therapy and relapse of disease in SCLC patients. The hope is that prospective application of this technology will translate into improved outcomes for patients afflicted with this dreadful disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This study was supported in part by a Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center Young Ambassadors Award and by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Cancer Institute (NCI) R01CA121210 (CML). CML was also supported by a Damon Runyon Clinical Investigator Award, a LUNGevity Career Development Award, a V Foundation Scholar-in-Training Award, an AACR-Genentech Career Development Award, and U10CA180864. KA was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA Fellowship (T32HL094296). ZZ was supported in part by CCSG NCI/NIH 2P30CA068485-19.

We first and foremost would like to thank the patients and their families. We are extremely grateful to the Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center Young Ambassadors Award for their generous support of this pilot project, to Anel Muterspaugh, Hina Chowdhry, and Brandon Winston for their assistance in consenting and collecting patient samples, to Dr. Adam Seegmiller for providing the bone marrow biopsy images, and to the entire Lovly laboratory and Darren Tyson for their thoughtful and critical review of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- SCLC

small cell lung cancer

- cfDNA

cell-free DNA

- AF

allele frequency

- OS

overall survival

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- ES

extensive stage

- LS

limited stage

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

- CNA

copy number alteration

- SNV

single nucleotide variant

- Indel

insertion/deletion

Footnotes

Author disclosures: CML has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Novartis, Astra Zeneca, Genoptix, Sequenom, and Ariad and has been an invited speaker for Abbott and Qiagen. LH is a consultant for Abbvie, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Merck, Roche, and Xcovery. JH, LPL, and CKR have an ownership stake and are employees of Resolution Biosciences. KA, WTI, CBM, YY, ZZ, HC, and YS report no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions: Designed experiments: KA, WTI, LPL, CKR, CML. Performed experiments: KA, YY, JH, LPL, CKR. Generated and analyzed data: KA, WTI, CBM, JH, LPL, CKR, CML. Provided direct patient care: LH, SY. Wrote the manuscript: KA, WTI, CML. Statistical analysis: ZZ, HC, YS. Reviewed the data and final manuscript: KA, WTI, CBM, ZZ, LH, LL, CKR, CML.

These data were presented as a poster presentation at the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Annual Meeting, Santa Monica, CA, February 22–25, 2017 and as an oral abstract at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, April 1–5, 2017.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Lung Cancer Statistics. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;893:1–19. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-24223-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernhardt EB, Jalal SI. Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 2016;170:301–322. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-40389-2_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan BA, Coward JI. Chemotherapy advances in small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5(Suppl 5):S565–578. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.07.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramalingam SS. Small-Cell Lung Cancer: New Directions for Systemic Therapy. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(2):119–120. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.009225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pietanza MC, Byers LA, Minna JD, Rudin CM. Small cell lung cancer: will recent progress lead to improved outcomes? Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(10):2244–2255. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gazdar AF, Minna JD. Developing New, Rational Therapies for Recalcitrant Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(10) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George J, Lim JS, Jang SJ, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiles of small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2015;524(7563):47–53. doi: 10.1038/nature14664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudin CM, Durinck S, Stawiski EW, et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis identifies SOX2 as a frequently amplified gene in small-cell lung cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44(10):1111–1116. doi: 10.1038/ng.2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meder L, Konig K, Ozretic L, et al. NOTCH, ASCL1, p53 and RB alterations define an alternative pathway driving neuroendocrine and small cell lung carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(4):927–938. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peifer M, Fernandez-Cuesta L, Sos ML, et al. Integrative genome analyses identify key somatic driver mutations of small-cell lung cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44(10):1104–1110. doi: 10.1038/ng.2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saunders LR, Bankovich AJ, Anderson WC, et al. A DLL3-targeted antibody-drug conjugate eradicates high-grade pulmonary neuroendocrine tumor-initiating cells in vivo. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(302):302ra136. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac9459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byers LA, Wang J, Nilsson MB, et al. Proteomic profiling identifies dysregulated pathways in small cell lung cancer and novel therapeutic targets including PARP1. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(9):798–811. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antonia SJ, Lopez-Martin JA, Bendell J, et al. Nivolumab alone and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in recurrent small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 032): a multicentre, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(7):883–895. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter L, Rothwell DG, Mesquita B, et al. Molecular analysis of circulating tumor cells identifies distinct copy-number profiles in patients with chemosensitive and chemorefractory small-cell lung cancer. Nat Med. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nm.4239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwapisz D. The first liquid biopsy test approved. Is it a new era of mutation testing for non-small cell lung cancer? Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(3):46. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.01.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511(7511):543–550. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012;489(7417):519–525. doi: 10.1038/nature11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Auperin A, Arriagada R, Pignon JP, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation for patients with small-cell lung cancer in complete remission. Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation Overview Collaborative Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(7):476–484. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908123410703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arriagada R, Le Chevalier T, Riviere A, et al. Patterns of failure after prophylactic cranial irradiation in small-cell lung cancer: analysis of 505 randomized patients. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(5):748–754. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou JM, Greystoke A, Lancashire L, et al. Evaluation of circulating tumor cells and serological cell death biomarkers in small cell lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(2):808–816. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou JM, Krebs MG, Lancashire L, et al. Clinical significance and molecular characteristics of circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor microemboli in patients with small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(5):525–532. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.3716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kidess E, Jeffrey SS. Circulating tumor cells versus tumor-derived cell-free DNA: rivals or partners in cancer care in the era of single-cell analysis? Genome Med. 2013;5(8):70. doi: 10.1186/gm474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(224):224ra224. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgensztern DDS, Masood A, Waqar SN, Carmack AC, Banks KC, et al. Circulating cell-free tumor DNA (cfDNA) testing in small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34 abstr e23077. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mollaoglu G, Guthrie MR, Bohm S, et al. MYC Drives Progression of Small Cell Lung Cancer to a Variant Neuroendocrine Subtype with Vulnerability to Aurora Kinase Inhibition. Cancer Cell. 2017;31(2):270–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Webb S. The cancer bloodhounds. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(11):1090–1094. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fournie GJ, Courtin JP, Laval F, et al. Plasma DNA as a marker of cancerous cell death. Investigations in patients suffering from lung cancer and in nude mice bearing human tumours. Cancer Lett. 1995;91(2):221–227. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(95)03742-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olsson E, Winter C, George A, et al. Serial monitoring of circulating tumor DNA in patients with primary breast cancer for detection of occult metastatic disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7(8):1034–1047. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Murillas I, Schiavon G, Weigelt B, et al. Mutation tracking in circulating tumor DNA predicts relapse in early breast cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(302):302ra133. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang GA, Tadepalli JS, Shao Y, et al. Sensitivity of plasma BRAFmutant and NRASmutant cell-free DNA assays to detect metastatic melanoma in patients with low RECIST scores and non-RECIST disease progression. Mol Oncol. 2016;10(1):157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tie J, Wang Y, Tomasetti C, et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis detects minimal residual disease and predicts recurrence in patients with stage II colon cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(346):346ra392. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf6219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.