Abstract

Threat appraisals—individuals’ perceptions of how stressful situations may threaten their well-being—are an important but understudied mechanism that could explain links between peer victimization and adjustment. The goal of the present study was to examine relationships between physical and relational victimization by peers, threats to the self, and aggression, anxiety, and depression to better understand the cognitive evaluations that make youth vulnerable to negative adjustment. The sample comprised two cohorts of African American adolescents (N = 326; 54 % female; M = 12.1; SD = 1.6) and their maternal caregivers, who participated in three waves of a longitudinal study. Path models revealed significant direct effects from Time 1 relational victimization, but not physical victimization, to Time 2 threat appraisals (i.e., negative self-evaluations and negative evaluations by others), controlling for Time 1 threat appraisals. Significant direct effects were found from Time 2 threats of negative evaluations by others to Time 3 youth-reported aggression, controlling for Time 1 and Time 2 aggression. Significant direct effects also were found from Time 2 threats of negative self-evaluations to T3 youth-reported depression, controlling for Time 1 and Time 2 depression. Overall, findings highlight the need to consider the role of threats to the self in pathways from peer victimization to adjustment and the implications these appraisals have for youth prevention and intervention efforts.

Keywords: Peer victimization, Threat appraisal, Adjustment, Adolescence

Introduction

Peer victimization is a frequently occurring stressor. Researchers estimate that 40–80 % of school-aged youth experience peer victimization at least once in their lifetime and about 15–20 % experience more chronic, ongoing victimization (Juvonen and Graham 2001). Peer victimization places youth at risk for both externalizing (e.g., aggression; Reijntjes et al. 2011) and internalizing behaviors (e.g., anxiety and depression; Reijntjes et al. 2010). However, there is wide variability in youth outcomes associated with peer victimization, which underscores the importance of identifying specific pathways from peer victimization to adjustment outcomes. The way youth respond to stress has important implications for understanding pathways from peer victimization to adjustment. Previous research has examined relationships between peer victimization, coping and emotion processes, and adjustment (e.g., Kochenderfer-Ladd 2004; Roecker-Phelps 2001); yet, another critical aspect of the coping process, threat appraisals, has been widely understudied. The current study examined the extent to which subtypes of peer victimization (i.e., physical and relational) predicted increases in threat appraisals related to the self (i.e., perceptions of negative self-evaluations and negative evaluations by others). We then explored whether threat appraisals to the self predicted increases in aggression, anxiety, and depression. To our knowledge, no longitudinal studies to date have addressed these specific pathways between peer victimization and adjustment among African American youth living in low-income, urban areas.

Peer Victimization

Peer victimization is defined as aggressive actions directed toward a victim that are intended to be hurtful and harmful. Adolescence represents a timeframe when peer victimization may occur more frequently and be more salient for several reasons. During adolescence, the growing importance of the peer group, desire to attain and maintain status with peers, increased time spent with peers, and greater level of intimacy in peer relationships may result in higher levels of peer victimization as youth vie for status and recognition and disclose personal information in more intimate contexts (Prinstein et al. 2001). In addition, advances in social cognitive competency, such as the increased capacity for future-oriented thought, greater ability to make attributions for others’ actions, and enhanced understanding of sarcasm, may contribute to increases in the sophistication and hurtfulness of peer victimization (Underwood 2003).

Two common subtypes of peer victimization are physical and relational. Physical victimization involves being the target of actual or threatened physical harm (Hawker and Boulton 2000). In contrast, relational victimization involves being the target of behaviors (e.g., spreading rumors and gossip) that are intended to damage youths’ relationships and standing with peers (Crick and Bigbee 1998). Some studies indicate that youth living in low-income, urban areas experience fairly high prevalence rates of both physical and relational forms of peer victimization (Sawyer et al. 2008; Sullivan et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2009). For example, in a sample of 276 predominantly African American youth living in low-income urban areas, 49 and 61 % of youth reported experiencing at least one act of physical or relational victimization, respectively, in the past 30 days, and approximately one-third of youth reported experiencing multiple acts of these subtypes of victimization during this timeframe (Sullivan et al. 2006). Thus, it is critical to better understand the outcomes of peer victimization among this population.

A growing number of studies have examined prospective relationships between peer victimization and internalizing and externalizing behaviors (Reijntjes et al. 2010, 2011). In one meta-analysis that included 10 studies, mean effect sizes showed that peer victimization led to increased externalizing behaviors over a 10–24 month period (Reijntjes et al. 2011). In a separate meta-analysis, the mean effect size of 15 studies indicated that peer victimization predicted changes in internalizing behaviors across 6–24 months (Reijntjes et al. 2010). Studies published since this meta-analysis also support these findings (e.g., Averdijk et al. 2011; Lösel and Bender 2011; Siegel et al. 2009). However, other longitudinal studies reported no significant direct effects between peer victimization and externalizing and internalizing behaviors (Hodges and Perry 1999; Khatri et al. 2000; Leadbeater and Hoglund 2009; McLaughlin et al. 2009; Schwartz et al. 1998), and these studies highlight the importance of pinpointing underlying mechanisms that link peer victimization to increased externalizing and internalizing behaviors.

Relationships Between Peer Victimization and Threat Appraisals

According to Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) transactional theory of stress, threat appraisals are perceptions of the ways stressful situations may threaten individual well-being and are an important part of the stress and coping process that influences adjustment. Examples of threat appraisals include threats to the self (e.g., negative self-evaluations and negative evaluations by others), threats of harm (e.g., to oneself or others), and threats of loss (e.g., loss of objects and loss of relationships) (Kliewer and Sullivan 2008). Lazarus and Folkman (1984) noted that although they are generated in response to various stressful situations, threat appraisals also are influenced by individual characteristics and thus can represent more global ways of responding to the environment. Given the significance of peer relationships during adolescence, events that harm or manipulate these relationships (i.e., relational victimization experiences) may pose significant threats to the self in the form of concerns about negative self-evaluations or being evaluated negatively by others. Such negative cognitions associated with peer victimization also may generalize to other stressful situations. For example, based on Downey and Feldman’s (1996) concept of rejection sensitivity, rejection experiences within important relationships (e.g., relational victimization) can generalize to other situations, triggering youth to expect rejection or hostility in other situations. Furthermore, peer victimization experiences may lead youth to attend to negative cues in other situations and be more likely to appraise these situations as threatening their sense of self.

Several empirical studies have examined relationships between peer victimization and threat appraisals (Catterson and Hunter 2010; Hunter and Boyle 2004; Storch et al. 2003). In a study of 469 Scottish children ages 9–14, youth identified several threat appraisals in response to peer victimization that included concerns about: (a) being physically or psychologically harmed, (b) retaliating with aggression, and (c) becoming socially isolated (Hunter and Boyle 2004). Among 110 Scottish children ages 8–12, peer victimization was associated positively with a composite measure of threat appraisals that encompassed concerns about being victimized repeatedly, having friends not like you anymore, being hurt physically, and feeling bad about yourself (Catterson and Hunter 2010). Lastly, Storch et al. (2003) found that concerns about negative evaluations by others were associated positively with physical and relational victimization among predominantly Hispanic American students in fifth and sixth grade.

A related line of literature has examined social information processing mechanisms, specifically interpretation of situational cues, in association with peer victimization (e.g., Crick and Dodge 1994). This step within social information processing models most closely resembles threat appraisal processes and involves formulating causal and intent attributions and evaluating the meaning of the situation for the self and others (Crick and Dodge 1994). Similar to threat appraisals, these interpretations are influenced by individual and situational characteristics. The majority of research focused on victimized youth has addressed causal and intent attributions and has used hypothetical situations to measure these attributions. For example, Graham et al. (2006) found that victimized middle school students’ causal attributions in response to hypothetical victimization scenarios were likely to include self-blame. Other studies have shown that peer victimization is associated positively with expectations of peer hostility in ambiguous situations (e.g., Dodge et al. 2003; Hoglund and Leadbeater 2007; Yeung and Leadbeater 2007). For instance, in a cross-sectional investigation of relationships between peer victimization and social-cognitive processes, Hoglund and Leadbeater (2007) found that physical and relational victimization were associated positively with hostile intent attributions for ambiguous peer scenarios.

However, previous studies focused on links between peer victimization and both threat appraisals and situational interpretations have several limitations. First, these studies are predominantly cross-sectional in nature and thus cannot determine whether peer victimization predicts increases in youths’ specific types of threat appraisals and situational interpretations over time. The majority of studies also have used hypothetical scenarios to measure youth’s cognitive evaluations of stress and little research has examined these cognitive processes in response to actual stressors, which produces more ecologically-valid interpretations. Lastly, few studies have attempted to delineate whether subtypes of peer victimization (i.e., physical and relational) are associated differentially with particular types of threat appraisals (i.e., threats to the self) (Storch et al. 2003; Yeung and Leadbeater 2007).

Relationships Between Threat Appraisals and Adjustment

Prior research suggests that threat appraisals are associated with both internalizing and externalizing behaviors, though more research has focused on internalizing behavior outcomes. For example, Sandler et al. (2000) found that a composite measure of children’s threat appraisals (i.e., concerns about negative self-evaluations, negative evaluations by others, rejection, criticism of others, harm to others, and material loss) was associated positively with higher levels of depression and anxiety. In a study of children with divorced parents, Sheets et al. (1996) showed that threats to the self (i.e., rejection by others, negative evaluations by others, and negative self-evaluations) in response to stressors associated with parental divorce predicted increases in anxiety over time, after controlling for initial levels of anxiety and stress. Among a sample of early adolescents, threat appraisals of self-blame for their parents’ marital conflict also predicted internalizing behaviors for boys and girls (Dadds et al. 1999). Moreover, among a sample of youth with cancer, Fearnow-Kenney and Kliewer (2000) found that threats to the self (i.e., negative evaluations by others and negative self-evaluations) in response to a variety of stressors were associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression, after controlling for the severity of illness.

Relatively fewer studies have examined relationships between threat appraisals and externalizing behaviors. For example, Dadds et al. (1999) found that appraisals of self-blame for marital conflict predicted externalizing behaviors for boys. In addition, threat appraisals regarding concerns about relatedness and competence in response to stressful video excerpts have been linked to anger emotions (Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2009). The lack of attention to relationships between threat appraisals and externalizing behavior represents an important limitation in the current literature. Research suggests that specific threat appraisals may be associated more strongly with different forms of adjustment difficulties. For instance, Crick and Bigbee (1998) noted that youth who respond to peer victimization with negative self-evaluations may be at higher risk for internalizing versus externalizing behaviors. In contrast, threat appraisals of negative evaluations by others may lead to more direct retaliation in the form of relational or physical aggression based on desires to maintain status and reputation with peers (Crick and Dodge 1996; Prinstein and Cillessen 2003).

The Current Study

The current study expands on the literature to date by examining a relatively understudied construct—threat appraisals—and their relationship to peer victimization and adjustment among low income, urban youth. The goal of the current study was to test a longitudinal path model, in which Time 1 peer victimization predicted Time 2 threat appraisals and Time 2 threat appraisals predicted Time 3 adjustment. Based on research highlighting the relevance of threats to the self for peer victimized youth (Crick and Bigbee 1998; Graham and Juvonen 1998; Storch et al. 2003), we chose to focus on the following two threat appraisals: negative self-evaluations and negative evaluations by others. First, we predicted a significant direct effect of physical victimization on threats of negative evaluations by others in response to stress, based on research showing that physically victimized youth have a tendency to believe that others are behaving in a hostile way towards them (e.g., Dodge et al. 2003). Second, we predicted a significant direct effect of relational victimization on threats of negative self-evaluations and negative evaluations by others in response to stress, given the significance of peers and friendships during adolescence and the likelihood that events that threaten these relationships may lead to increased concerns about thinking negatively about the self and being evaluated negatively by others in stressful situations (e.g., Downey and Feldman 1996; Yeung and Leadbeater 2007). Third, drawing from previous conceptual and empirical efforts that link negative self-evaluations to internalizing behaviors (Dadds et al. 1999; Fearnow-Kenney and Kliewer 2000; Sheets et al. 1996), we anticipated a significant direct effect of negative self-evaluations on internalizing behaviors. Fourth, we anticipated a significant direct effect of negative evaluations by others on aggressive behaviors as this type of threat appraisal may lead to retaliation in order to protect image, status, and reputation (Crick and Dodge 1996; Prinstein and Cillessen 2003).

Method

Setting and Participants

Study participants included 326 adolescents (175 girls and 151 boys) representing two cohorts of fifth (n = 173) and eighth (n = 153) grade students. Participants ranged in age from 10 to 16 (M = 12.1; SD = 1.6). All participants identified themselves as African-American. A variety of family structures were represented including 41.8 % of maternal caregivers who never married, 25.8 % married, 23.4 % separated or divorced, 6.8 % cohabitating, and 2.2 % widowed. The median household income for the sample fell between $300 and $400 per week, with 34.3 % of the sample earning $300 or less per week and 38.6 % earning a weekly income of $500 or more. Additionally, caregivers’ level of education varied with 8.9 % holding a bachelor’s or advanced degree, 12.3 % holding an associate’s degree or completed vocational training, 23.7 % who pursued, but did not complete some form of education beyond high school, 32.3 % holding a high school or general education diploma, and 22.8 % who did not complete high school. Participants in the current study lived in neighborhoods in a large city in the Southeastern United States characterized by high violence and/or poverty rates (e.g., neighborhoods with low income housing and high crime rates). Based on US Census data for this city from 2000, a third of youth lived in poverty.

Procedures

All study procedures were approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board. Study participants were recruited as part of a larger four-year study that examined relationships between violence- and poverty-related stressors, coping processes, and adjustment. Recruitment took place in inner-city neighborhoods that had high rates of violence and/or poverty based on police statistics and census data. Participants were recruited by flyers posted door to door in eligible neighborhoods, community agencies, and at community events. To be considered eligible, families must have received a flyer about the study, speak English, and have a female caregiver as well as a child in either the fifth or eighth grade living in the home. Eligible and interested families were scheduled for interviews, which took place in the Fall of 2003 and Spring of 2004, with follow-up interviews occurring one and 2 years later. The current study used the first three waves of data. Interviewers reviewed the consent and assent forms with maternal caregivers and youth, and obtained informed consent (for the caregiver interview) and permission (for the child interview) from caregivers and also assent from youth to participate in the child interview prior to data collection. Of those families that were eligible, 63 % opted to participate in the study.

The interviews were conducted face-to-face and in separate rooms for caregivers and adolescents. The interviewers hired to conduct these sessions were of various racial/ethnic backgrounds and genders. Tests for interviewer race and gender effects revealed no systematic biases, ps >.10. The interviewers read most questions aloud, using visual aids to show response options and collect data from youth. The portion of the youth interview that comprised more sensitive scales (e.g., drug use and coping behavior) was completed by youth using a survey without interviewer assistance. Interviews lasted approximately 2.5 h and each family received $50 in gift cards after each wave of data collection in appreciation of their time and effort.

Measures

Peer Victimization

Victimization by peers was measured at Time 1 using the Problem Behavior Frequency Scales (PBFS; Miller-Johnson et al. 2004), a self-report measure comprised of seven subscales that assessed the frequency of problem behaviors. This scale was revised to assess how frequently youth engaged in these behaviors in the past year versus the past 30-days. Peer victimization was measured by two subscales, Physical Victimization and Relational Victimization, that are partially based on the Social Experiences Questionnaire (SEQ-S) developed by Crick and Grotpeter (1996). The Physical Victimization subscale consists of five items (e.g., “How many times have you been hit by another kid?”) and the Relational Victimization subscale consists of six items (e.g., “How many times has someone spread a false rumor about you?”). Alphas for Physical Victimization and Relational Victimization were .76 for both subscales.

Threat Appraisal

The Threat Appraisals of Negative Events Scale (Kliewer and Sullivan 2008) was used to assess youth’s specific concerns related to a stressful event discussed in the Social Competence Interview (SCI: Ewart et al. 2002) at Time 2. This interview asks individuals to recall a salient stressful event that occurred up to one year ago and prompts them to re-experience it by asking a series of semi-structured questions related to the stressor. Following the SCI youth were administered the Threat Appraisals of Negative Events Scale. This scale contains six four-item subscales, and the current study focused on the following two subscales: (a) Negative Evaluations by Others (e.g., “How much did you think that you would lose the respect of others?”), which measures concerns about being looked down upon by others; and (b) Negative Self-Evaluations (e.g., “How much did you think that it was your fault or you were to blame?”), which assesses threats of feeling bad about the self. Adolescents were asked to rate, on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 4 (A lot), how much they felt or were concerned about a list of 24 statements during the stressful event discussed in the SCI. The scale has been validated in previous research examining longitudinal relationships between exposure to community violence, threat appraisals, and adjustment in urban African American adolescent samples (Kliewer and Sullivan 2008). This research also demonstrated invariance in the factor structure across age and gender (Kliewer and Sullivan 2008). Alphas for Negative Evaluations by Others and Negative Self-Evaluations were .64 and .72, respectively.

Youth-Reported Aggressive Behaviors

Youth completed the Problem Behavior Frequency Scales (PBFS; Farrell et al. 2000; Miller-Johnson et al. 2004; Sullivan et al. 2006) to indicate how frequently they engaged in a variety of behaviors in the past 30 days on a six-point response scale from 0 (Never) to 6 (20 or more times). To measure aggressive behavior the Relational Aggression, Non-Physical Aggression, and Physical Aggression subscales were used. The Relational Aggression subscale consists of 6 items (e.g., “How many times have you spread a false rumor about someone”). The Non-Physical Aggression subscale consists of 5 items (e.g., “How many times have you teased someone to make them angry?”). The Physical Aggression subscale includes 7 items (e.g., “How many times have you hit or slapped another kid?”). Alphas for the Physical Aggression, Non-Physical Aggression, and Relational Aggression subscales were .82, .82, and .77, respectively. A Total Aggression score was obtained by calculating the mean for the items from these three subscales. The alpha for the combined scale was .91.

Parent-Reported Aggressive Behaviors

Parent reports of aggressive behavior were measured with the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach 1991), a 113-item measure that assesses the child’s behavioral and emotional problems over the past 3 months. Parents respond to each item on a scale of 1 (Not true) to 3 (Very True or Often True). The Aggressive Behavior subscale was used. The Aggressive Behavior subscale measures the frequency of physical items (e.g., “This child physically attacks people”) and verbal aggression (e.g., “This child teases a lot”) and contains 20 items. The CBCL is widely used and has excellent reliability and validity (Achenbach 1991). The alpha for the Aggressive Behavior subscale was .91.

Youth-Reported Internalizing Behaviors

Youth completed the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds and Richmond 1978) and the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs 1992) to measure internalizing behaviors. The RCMAS is a 28-item measure assessing physical and emotional symptoms of anxiety. Youth answered, “Yes” or “No” to indicate whether or not items are true. A Total Anxiety Scale score was calculated by taking the mean of the items, with higher scores representing greater levels of anxiety. Previous studies have demonstrated good reliability of the RCMAS (.83) and high correlations (r = .76) between the RCMAS and other measures of anxiety, including the Anxiety subscale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI; Lee et al. 1988). The alpha for this scale was .89.

The CDI is a 27-item measure assessing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral symptoms of depression. For each item, youth are asked to indicate which response best describes them in the past 2 weeks; responses are graded in order of increasing severity ranging from 0 (absence of symptoms; e.g., “I am sad once in a while”) to 2 (definite symptoms; e.g., “I am sad all the time”). A Total Depression Scale score was obtained by summing all the items, with higher scores indicating greater depression. The CDI has demonstrated relatively high test–re-test reliability and internal consistency, with coefficients ranging from .71 to .89 (Kovacs 1992). The alpha for this scale was .85.

Parent-Reported Internalizing Problems

Parent-reported internalizing problems were assessed using the Anxiety/Depression Scale of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach 1991). The Anxiety/Depression subscale contains 14 items (e.g., “This child is nervous, high strung, or tense” and “This child is unhappy, sad, or depressed”). The alpha for this subscale was .85.

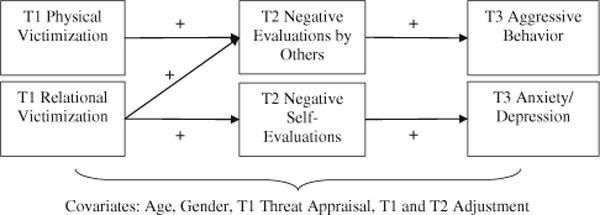

Analytic Strategy

The conceptual model depicting hypothesized relationships tested in the current study is illustrated in Fig. 1. Path models were assessed in Mplus 6.12 (Muthén and Muthén 2010). Four separate models were run for child-reported anxiety/depression, child-reported aggression, parent-reported anxiety/depression, and parent-reported aggression. Each model tested direct effects between peer victimization at Time 1 and threat appraisals at Time 2, controlling for threat appraisals at Time 1 and direct effects between threat appraisals at Time 2 and adjustment at Time 3, controlling for adjustment at Time 1 and Time 2. Covariates also included age and gender. Path analysis results were calculated with the MLR estimator, to account for the non-normality of study variables. Missing data were handled using the full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) method, which estimates missing data based on the variables that are present so that all data can be used (Muthén and Muthén 2010). Several fit indices were used to test model fit, including the χ2 statistic, comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Models with a CFI value of .90 or higher (Hu and Bentler 1999) and RMSEA value below .08 were considered to have an acceptable fit.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model depicting hypothesized relationships between peer victimization, threat appraisals, and adjustment problems

Results

Attrition Analyses

Adolescents who participated in all three waves of data collection (N = 244) were compared to adolescents who participated in the first wave or first two waves only (N = 82) on demographics, peer victimization, threat appraisals, and adjustment at Time 1. There were no significant differences between the two groups based on demographic variables (i.e., gender, age, and grade), peer victimization, threat appraisals, or the adjustment variables.

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics include means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variables (see Table 1). These statistics reflect population parameter estimates based on maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors that adjust for missing data. Correlations indicated that relational victimization at Time 1 was associated significantly with physical victimization at Time 1 (r = 0.54), negative self-evaluations at Time 2 (r = 0.22), and negative evaluations of others at Time 2 (r = 0.19). Physical victimization at Time 1 was associated significantly with negative self-evaluations at Time 2 (r = 0.13). Threat appraisals were correlated significantly with each other (r = 0.40) and youth-reported internalizing behavior at Time 3 (rs ranged from 0.22 to 0.32). In addition, negative evaluations by others at Time 2 were correlated significantly with youth-reported aggression at Time 3 (r = 0.18). All youth-reported adjustment variables were correlated significantly with each other (rs ranged from 0.29 to 0.80) and all parent-reported adjustment variables were correlated significantly with each other (r = .74). Youth- and parent-reports of aggression were correlated significantly (r = .21) as were youth- and parent-reports of anxiety/depression (rs ranged from .22 to .27).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relational victimization (T1) | – | 8.96 | 3.05 | ||||||||

| 2. Physical victimization (T1) | .54*** | – | 5.83 | 2.00 | |||||||

| 3. Negative self-evaluations (T2) | .22*** | .13* | – | 5.30 | 2.09 | ||||||

| 4. Negative evaluations by others (T2) | .19** | .06 | .40*** | – | 5.65 | 2.28 | |||||

| 5. Aggressive behavior—PBFS (T3) | .18** | .12 | .12 | .18** | – | 26.73 | 10.70 | ||||

| 6. Aggressive behavior—CBCL (T3) | .14* | .14* | .08 | .08 | .21** | – | 29.48 | 7.40 | |||

| 7. Anxiety/depression—CBCL (T3) | .17** | .11 | .10 | .09 | .09 | .74*** | – | 18.10 | 4.22 | ||

| 8. Total anxiety—RCMAS (T3) | .26*** | .17** | .29*** | .22** | .29*** | .17** | .27*** | – | 34.81 | 5.83 | |

| 9. Total depression—CDI (T3) | .29*** | .19** | .32*** | .23*** | .32*** | .18** | .22** | .80*** | – | 34.14 | 6.25 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Path Analyses

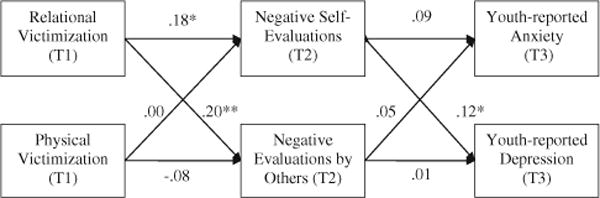

Relationships Between Peer Victimization, Threat Appraisals, and Child-Reported Internalizing Behavior

This model is depicted in Fig. 2 and had an acceptable fit (χ2 = 35.07, df = 18, p < .01, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .97). Examination of direct effects indicated that relational victimization at Time 1 was related to higher levels of negative self-evaluations (β = .18, Z = 2.54, p < .05) and negative evaluations by others at Time 2 (β = .20, Z = 3.15, p < .01), controlling for age, gender, and Time 1 threat appraisals. There were no significant effects from physical victimization at Time 1 to threat appraisals at Time 2. Negative self-evaluations at Time 2 were associated with higher levels of youth-reported depression at Time 3 (β = .12, Z = 2.06, p < .05), controlling for age, gender, and Time 1 and Time 2 depression. There were no significant effects from threat appraisals at Time 2 to youth-reported anxiety at Time 3.

Fig. 2.

Standardized path coefficients for relationships between T1 peer victimization, T2 threat appraisals and T3 youth-reported internalizing behavior. Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

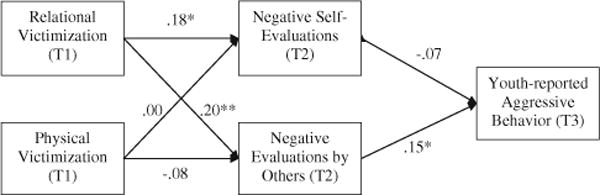

Relationships Between Peer Victimization, Threat Appraisals, and Child-Reported Aggressive Behavior

This model is depicted in Fig. 3 and had an acceptable fit (χ2 = 5.38, df = 8, p = .717, RMSEA = .00, CFI = 1.00). Examination of direct effects indicated that relational victimization at Time 1 was related to higher levels of negative self-evaluations (β = .18, Z = 2.55, p < .05) and negative evaluations by others at Time 2 (β = .20, Z = 3.18, p < .01), controlling for age, gender, and Time 1 threat appraisals. There were no significant effects from physical victimization at Time 1 to threat appraisals at Time 2. Negative evaluations by others at Time 2 were associated with higher levels of youth-reported aggression at Time 3 (β = .15, Z = 2.43, p < .05), controlling for age, gender, and Time 1 and Time 2 aggression.

Fig. 3.

Standardized path coefficients for relationships between T1 peer victimization, T2 threat appraisals and T3 youth-reported aggressive behavior. Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

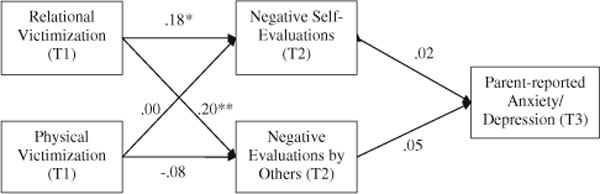

Relationships Between Peer Victimization, Threat Appraisals, and Parent-Reported Internalizing Behavior

This model is depicted in Fig. 4 and had an acceptable fit (χ2 = 2.96, df = 8, p = .937, RMSEA = .00, CFI = 1.00). Examination of direct effects indicated that relational victimization at Time 1 was related to higher levels of negative self-evaluations (β = .18, Z = 2.56, p < .05) and negative evaluations by others at Time 2 (β = .20, Z = 3.17, p < .01), controlling for age, gender, and Time 1 threat appraisals. There were no significant effects from physical victimization at Time 1 to threat appraisals at Time 2 or from threat appraisals at Time 2 to parent-reported anxiety/depression at Time 3.

Fig. 4.

Standardized path coefficients for relationships between T1 peer victimization, T2 threat appraisals and T3 parent-reported internalizing behavior. Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

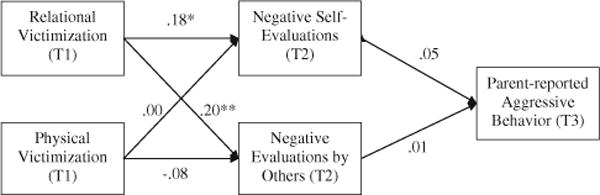

Relationships Between Peer Victimization, Threat Appraisals, and Parent-Reported Aggressive Behavior

This model is depicted in Fig. 5 and had an acceptable fit (χ2 = 3.71, df = 8, p = .882, RMSEA = .00, CFI = 1.00). Examination of direct effects indicated that relational victimization at Time 1 was related to higher levels of negative self-evaluations (β = .18, Z = 2.56, p < .05) and negative evaluations by others at Time 2 (β = .20, Z = 3.17, p < .01), controlling for age, gender, and Time 1 threat appraisals. There were no significant effects from physical victimization at Time 1 to threat appraisals at Time 2 or from threat appraisals at Time 2 to parent-reported aggression at Time 3.

Fig. 5.

Standardized path coefficients for relationships between T1 peer victimization, T2 threat appraisals and T3 parent-reported aggressive behavior. Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Discussion

A large body of literature documents that peer victimization is a frequently occurring stressor that places adolescents at risk for a variety of adjustment difficulties (Reijntjes et al. 2010, 2011). Stress and coping theories (Lazarus and Folkman 1984) highlight the role of threat appraisals, or perceptions of how stressful situations may threaten well-being, in influencing patterns of behavioral responses to stressful situations. Although researchers underscore the need to identify pathways connecting peer victimization to adjustment outcomes, the role of threat appraisals remains understudied. To date, several cross-sectional studies have found positive associations between peer victimization and threat appraisals (e.g., Catterson and Hunter 2010). Some previous studies have also showed concurrent and prospective associations between threat appraisals and adjustment, with most of these studies focusing on internalizing behaviors (e.g., Fearnow-Kenney and Kliewer 2000; Sandler et al. 2000; Sheets et al. 1996). The current study examined links between relational and physical subtypes of peer victimization, threat appraisals to the self, and aggression, anxiety, and depression across a two-year timeframe. It extends prior research in this area not only through the use of an urban, low-income African American sample but also by examining longitudinal relationships between relational and physical subtypes of peer victimization and threat appraisals to the self and between these threat appraisals and externalizing behaviors.

The current study tested a longitudinal path model, in which Time 1 physical and relational victimization predicted Time 2 threat appraisals to the self (i.e., threats of negative self-evaluations and negative evaluations by others) and Time 2 threat appraisals predicted Time 3 anxiety, depression, and aggression. Findings indicated partial support for our study hypotheses. Path models revealed significant direct effects from Time 1 relational victimization, but not physical victimization, to Time 2 threats of negative self-evaluations and negative evaluations by others, controlling for Time 1 threat appraisals. Significant direct effects were also found from Time 2 threats of negative evaluations by others to Time 3 youth-reported aggression and from Time 2 threats of negative self-evaluations to T3 youth-reported depression, controlling for Time 1 and Time 2 levels of adjustment. In our discussion, we focus on the following: (a) how our work extends current findings in the literature, (b) potential reasons why there were no significant pathways from physical victimization to threat appraisals, and (c) potential reasons why there were no significant pathways from threat appraisals to parent-reported adjustment.

Current study findings indicated significant pathways between Time 1 relational victimization and Time 2 threats of negative self-evaluations, and between Time 2 threats of negative self-evaluations and child-reported depression. Although prior research largely has focused on overt or composite peer victimization measures in examining relationships between peer victimization and self-blaming tendencies (e.g., Graham et al. 2006; Graham and Juvonen 1998), our findings of significant paths from relational victimization to negative self-evaluations and negative self-evaluations to depression are consistent with some prior research (Crick and Bigbee 1998). Some youth who experience relational victimization may be particularly likely to focus their attention towards internal blame and away from adaptive problem solving, in turn making them more vulnerable to feelings of depression and anxiety. Exposure to peer victimization that contributes to increased tendencies to evaluate the self negatively in response to stressors may also lead children to avoid social interactions, thus limiting youth’s exposure to positive peer relationships and causing them to experience increased levels of internalized distress (Crick and Bigbee 1998; Storch et al. 2003). Overall, the tendency to perceive stressful events as posing threats of negative self-evaluations may reflect an internalization of relational victimization experiences, with this type of threat appraisals then contributing to depressive symptoms.

Current study findings also indicated a significant pathway between Time 1 relational victimization and Time 2 threats of negative evaluations by others, and between Time 2 threats of negative evaluations by others and Time 3 child-reported aggression. These findings are consistent with previous research showing the connection between relational victimization and tendencies to attribute hostile intent to others in ambiguous social situations (e.g., Yeung and Leadbeater 2007). Thus, youth who experience negative peer interactions in the form of relational victimization may develop expectancies of rejection and hostility that generalize to other situations (Downey and Feldman 1996). These findings also support the notion that threats of negative evaluations by others may lead to more direct retaliation in the form of relational or physical aggression. Some youth who are concerned about being looked down upon by others in response to stressful events may engage in aggressive behaviors based on desires to gain, reestablish, or maintain status and reputation with peers (Crick and Dodge 1996; Prinstein and Cillessen 2003).

Our results showed that relational, but not physical victimization was associated with threats to the self. Several factors may account for the lack of findings for physical victimization. First, it is possible that physical victimization simply does not activate the same sense of threat to the self that relational victimization activates. Developmental needs for belongingness in adolescence are fulfilled in part through positive relationships with peers and social standing within peer groups. Because relational victimization is intended to damage social relationships and often involves multiple peers (e.g., in cases of rumor and gossip), it may be more likely than physical victimization to lead to increased tendencies to perceive threats to the self over time and across different situations. The motivations underlying physical victimization may be more varied, therefore enabling youth to make different types of attributions for physical victimization (e.g., thinking that the other person is just a bully; thinking that the other person wants to inflict physical harm) and decreasing the likelihood that these cognitive evaluations will generalize to other stressful situations.

Our results showed that threat appraisals were associated differentially with youth-reported outcomes, but not parent-reported outcomes. There are several potential reasons for this lack of findings. First, previous research indicates that there is often a considerable discrepancy in adolescents’ and parents’ reports of internalizing and externalizing behavior (Sourander et al. 1999; Stanger and Lewis 1993; Youngstrom et al. 2000). For example, in a study of 13-year-old youth and their caregivers, Stanger and Lewis (1993) found that adolescents’ and their parents’ reports of internalizing and externalizing behaviors differed significantly, such that adolescents reported higher levels of both behaviors as compared to their parents. Further, previous research also suggests that child-verses parent-report is more informative for assessing internalizing behaviors, as some symptoms of anxiety and depression are not overt and are difficult for parents to infer (e.g., Hope et al. 1999). Second, the questions assessed by parents’ reports on the Child Behavior Checklist do not parallel those assessed by the youth report of aggression. More specifically, the youth report includes items tapping physical, verbal, and relational aggression, whereas the parent report includes items tapping physical and verbal forms of aggression only.

Study Limitations

Although the study had a number of methodological strengths, it is important to note several limitations. First, we relied solely on adolescents’ reports of peer victimization. However, several studies have demonstrated the reliability of self-report measures of physical and relational victimization (e.g., Crick and Grotpeter 1996; Crick and Bigbee 1998; Prinstein et al. 2001). Additionally, the peer victimization scales used in the current study were based on measures that are comparable to peer-nomination measures of these constructs (Crick and Bigbee 1998). In addition, the Threat Appraisal of Negative Events Scale (Kliewer and Sullivan 2008) and the Problem Behavior Frequency Scales (Miller-Johnson et al. 2004) assessed cognitions and behaviors, respectively that occurred in the last year, and as such were subject to response bias. Furthermore, youth’s reports of threat appraisals may have been less of a reflection of their immediate cognitive responses at the time of the actual event than their current evaluation of the recalled event. Moreover, due to power limitations, differences in the path models across age or gender were not examined, although we controlled for the effects of these demographic characteristics. Similarly, the current study could not test differences by income level, urbanicity, and race due to racial homogeneity of the sample and the interrelatedness between these other constructs. Further research is needed to examine the generalizability of the current study’s findings to African American youth in different contexts or to adolescents from different ethnic/racial or socio-economic backgrounds, as the current study is one of few studies (e.g., Hanish and Guerra 2002; McLaughlin et al. 2009) to assess longitudinal relationships between peer victimization, threat appraisals, and adjustment among a large sample of African American youth.

Directions for Future Research

Overall, our findings highlight the utility of examining youths’ appraisals separately for physical and relational victimization experiences in order to better understand cognitive appraisals that may be uniquely related to specific subtypes of peer victimization. Additional research is needed to identify threat appraisals that may be involved in pathways from physical victimization to adjustment difficulties. For example, physical victimization may lead to other threats appraisals, such as threats of physical harm and loss of objects, which may contribute to increases in aggressive or internalizing behavior. Another direction for future research is to examine poly-victimization (e.g., child maltreatment, community violence exposure, and peer victimization) to better understand the relationships between different types of violence exposure, specific threat appraisals, and adjustment. Lastly, future research should explore potential gender and age differences in relationships between physical and relational victimization experiences, threat appraisals, and adjustment difficulties, given evidence of the differential salience of physical and relational victimization for boys and girls and over the course of adolescence (Cullerton-Sen and Crick 2005; Sullivan et al. 2006).

Practical Implications

Current study findings highlight the importance of understanding youth’s specific threat appraisals in association with subtypes of peer victimization as these concerns make youth vulnerable to negative adjustment. Given findings that relational victimization, and not physical victimization, was associated with threat appraisals (i.e., negative self-evaluations and negative evaluations by others) that then contributed to increased aggression and depression, this form of victimization is especially important to attend to in school settings where the majority of victimization occurs. For example, school policies around bullying behavior should address relational forms of victimization, in addition to physical, so as the reduce or prevent this type of victimization. Teacher intervention is also a key prevention strategy; subsequently, teachers should be trained to recognize and address relational victimization within their classrooms to prevent subsequent negative adjustment.

Attention to youth’s threat appraisals may be useful in therapeutic settings to determine appropriate strategies to reduce aggressive behavior or internalizing symptoms. For example, targeting tendencies for self-blame and worries about negative evaluations by others in response to relational victimization may be an effective strategy to reduce youth’s risk for aggression and depression. Study findings also have important implications for the development of youth violence prevention and intervention efforts targeted toward African American youth living in low-income urban settings. Instructing youth on how to interpret and adaptively cope with peer victimization experiences may be a key component of efforts to prevent adjustment difficulties.

Conclusion

Peer victimization is a significant stressor that unfortunately is experienced by many adolescents. Previous research indicates that youth who experience peer victimization are at risk for adjustment difficulties. The current study sought to add to the existing research by testing specific longitudinal pathways from peer victimization to threat appraisals to adjustment and to examine these pathways among a relatively understudied population— low-income urban African American youth. Findings indicated that there were significant longitudinal pathways between relational victimization and threats appraisals to the self. These threat appraisals including negative self-evaluations and negative evaluations by others then predicted increased frequencies of depression and aggression, respectively. Thus, our study highlights the salience of relational victimization for youth, as these types of experiences predicted increases in concerns about feeling badly about the self and being evaluated negatively by others over time. Our study also highlights the utility of examining youth’s specific threat appraisals, as threats of negative self-evaluations and negative evaluations by others differentially predicted youth outcomes. Overall, our study expands on the current body of literature by pinpointing threats to the self as an important mechanism linking relational victimization to future negative adjustment for low-income urban African American youth.

Acknowledgments

KT conceived of the study, participated in its design and the interpretation of the data, performed statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. TS conceived of the study, participated in its design and the interpretation of the data, and helped to perform statistical analysis and draft the manuscript participated. WK participated in the design of the study and the interpretation of the data and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, NIH grant K5K01DA15442 awarded to Wendy Kliewer (Virginia Commonwealth University). The findings and conclusions in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Katherine Taylor is a doctoral student at Virginia Commonwealth University. She received her M.S. in Developmental Psychology from Virginia Commonwealth University. Her research interests include children’s and adolescents’ coping and adjustment to violence exposure in addition to school-based prevention programs that target youth violence and promote positive development.

Terri Sullivan is an Associate Professor at Virginia Commonwealth University. She received her Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology from Virginia Commonwealth University. Her work focuses on the impact of violence exposure (e.g., exposure to community violence and peer victimization) on children’s psychosocial and emotional development. She is especially interested in the development and evaluation of the effectiveness of school-based youth violence prevention programs for children and adolescents, with a focus on youth with disabilities.

Wendy Kliewer is a Professor and Chair of Psychology at Virginia Commonwealth University. She received her Ph.D. in Social Ecology from the University of California, Irvine. She is a stress and coping researcher whose work over the past 17 years has focused on the consequences of exposure to violence in youth. She is particularly interested in the role of parents and extended family in mitigating the effects of stressors for youth, and in the role of culture in shaping parent–child interaction to influence coping and adjustment.

References

- Achenbach TM. Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Averdijk M, Muller B, Eisner M, Ribeaud D. Bullying victimization and later anxiety and depression among pre-adolescents in Switzerland. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research. 2011;3:103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Catterson J, Hunter SC. Cognitive mediators of the effect of peer victimization on loneliness. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2010;80:403–416. doi: 10.1348/000709909X481274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Bigbee M. Relational and overt forms of peer victimization: A multiinformant approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:337–347. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social-information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. Social information-processing mechanisms in reactive and proactive aggression. Child Development. 1996;67:993–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Children’s treatment by peers: Victims of relational and overt aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:367–380. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400007148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cullerton-Sen C, Crick NR. Understanding the effects of physical and relational victimization: The utility of multiple perspectives in predicting social emotional adjustment. School Psychology Review. 2005;34:147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Atkinson E, Turner C, Blums GJ, Lendich B. Family conflict and child adjustment: Evidence for a cognitive-contextual model of intergenerational transmission. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:194–208. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.13.2.194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Lansford JE, Burks VS, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Fontaine R, et al. Peer rejection and social information-processing factors in the development of aggressive behavior problems in children. Child Development. 2003;74:374–393. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Feldman SI. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:1327–1343. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart CK, Jorgensen RS, Suchday S, Chen E, Matthews KA. Measuring stress resilience and coping in vulnerable youth: The social competence interview. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:339–352. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Kung EM, White KS, Valois RF. The structure of self-reported aggression, drug use, and delinquent behaviors during early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2000;29:282–292. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnow-Kenney MD, Kliewer W. Threat appraisal and adjustment among children with cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2000;18:1–17. doi: 10.1300/J077v18n03_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Bellmore AD, Mize J. Peer victimization, aggression, and their co-occurrence in middle school: Pathways to adjustment problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:363–378. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Juvonen J. Self-blame and peer victimization in middle school: An attributional analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:587–599. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Guerra NG. A longitudinal analysis of patterns of adjustment following peer victimization. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:69–89. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402001049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker DSJ, Boulton MJ. Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:441–455. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Perry DG. Personal and interpersonal antecedents and consequences of victimization by peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:677–685. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoglund WL, Leadbeater BJ. Managing threat: Do social-cognitive processes mediate the link between peer victimization and adjustment problems in early adolescence? Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:525–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00533.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hope TL, Adams C, Reynolds L, Powers D, Perez RA, Kelley ML. Parent vs. self-report: Contributions toward diagnosis of adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1999;21:349–363. doi: 10.1023/A:1022124900328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter SC, Boyle JME. Appraisal and coping strategy use in victims of school bullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2004;74:83–107. doi: 10.1348/000709904322848833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Graham S. Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York: Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Khatri P, Kuperschmidt JB, Patterson C. Aggression and peer victimization as predictors of self-reported behavioural and emotional adjustment. Aggressive Behavior. 2000;26:345–358. doi: 10.1002/1098-2337(2000)26:5<345:AID-AB1>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Sullivan TN. Community violence exposure, threat appraisal, and adjustment in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:860–873. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer-Ladd B. Peer victimization: The role of emotions in adaptive and maladaptive coping. Social Development. 2004;13:329–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2004.00271.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The children’s depression inventory. Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater B, Hoglund W. The effects of peer victimization and physical aggression on changes in internalizing from first to third grade. Child Development. 2009;80:843–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SW, Piercel WC, Friedlander R, Collamer W. Concurrent validity of the revised children’s manifest anxiety scale (RCMAS) for adolescents. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1988;48:429–433. doi: 10.1177/0013164488482015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lösel F, Bender D. Emotional antisocial outcomes of bullying and victimization at school: A follow-up from childhood to adolescence. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research. 2011;3:89–96. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hilt LM. Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking peer victimization to internalizing symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:894–904. doi: 10.1037/a0015760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Johnson S, Sullivan TN, Simon TR, MVPP Evaluating the impact of interventions in the Multisite Violence Prevention Study: Samples, procedures and methods. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;26:48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Vernberg ER. Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:479–491. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Cillessen AHN. Forms and functions of adolescent peer aggression associated with high levels of peer status. Merrill Palmer Quarterly. 2003;44:310–342. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2003.0015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, Boelen PA, van der Schoot M, Telch MJ. Prospective linkages between peer victimization and externalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis. Aggressive Behavior. 2011;37:215–222. doi: 10.1002/ab.20374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, Telch MJ. Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2010;34:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. What I Think and Feel: A revised measure of children’s manifest anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1978;6:271–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00919131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roecker-Phelps CE. Children’s responses to overt and relational aggression. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:240–252. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3002_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Kim-Bae LS, MacKinnon D. Coping and negative appraisal as mediators between control beliefs and psychological symptoms in children of divorce. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:336–347. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2903_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer AL, Bradshaw CP, O’Brennan LM. Examining ethnic, gender, and developmental differences in the way children report being a victim of “bullying” on self-report measures. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.011. doi:10/1016/j/jadohealth.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, McFadyen-Ketchum SA, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Peer group victimization as a predictor of children’s behavior problems at home and in school. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:87–99. doi: 10.1017/s095457949800131x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets V, Sandler IN, West SG. Appraisals of negative events by preadolescent children of divorce. Child Development. 1996;67:2166–2182. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RS, La Greca AM, Harrison HM. Peer victimization and social anxiety in adolescents: Prospective and reciprocal relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:1096–1109. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sourander A, Helstelä L, Helenius H. Parent-adolescent agreement on emotional and behavioral problems. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1999;34:657–663. doi: 10.1007/s001270050189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanger C, Lewis M. Agreement among parents, teachers, and children on internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1993;22:107–115. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2201_11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Nock MK, Masia-Warner C, Barlas ME. Peer victimization and social-psychological adjustment in Hispanic and African-American children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2003;12:439–452. doi: 10.1023/A:1026016124091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TN, Farrell AD, Kliewer W. Peer victimization in early adolescence: Association between physical and relational victimization and drug use, aggression, and delinquent behaviors among urban middle school students. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:119–137. doi: 10.1017/S095457940606007x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood MK. Adolescence: Girl talk, moral negotiation, and strategic interactions to inflict social harm. In: Kopp CB, Asher SR, editors. Social aggression among girls. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 134–178. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Iannotti RJ, Nansel TR. School bullying among adolescents in the United States: Physical, verbal, relational, and cyber. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung RS, Leadbeater BJ. Does hostile attributional bias for relational provocations mediate the short-term association between relational victimization and aggression in preadolescence? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:973–983. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9162-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom EA, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Patterns and correlates of agreement between parent, teacher, and male youth behavior ratings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:1038–1052. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Lees DC, Bradley GL, Skinner EA. Use of an analogue method to examine children’s appraisals of threat and emotion in response to stressful events. Motivation and Emotion. 2009;33:136–149. doi: 10.1007/s11031-009-9123-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]