Abstract

Molecular checkpoints that trigger the onset of islet autoimmunity or progression to human type 1 diabetes (T1D) are incompletely understood. Using T cells from children at an early stage of islet autoimmunity without clinical T1D, we find that a microRNA181a (miRNA181a)–mediated increase in signal strength of stimulation and costimulation links nuclear factor of activated T cells 5 (NFAT5) with impaired tolerance induction and autoimmune activation. We show that enhancing miRNA181a activity increases NFAT5 expression while inhibiting FOXP3+ regulatory T cell (Treg) induction in vitro. Accordingly, Treg induction is improved using T cells from NFAT5 knockout (NFAT5ko) animals, whereas altering miRNA181a activity does not affect Treg induction in NFAT5ko T cells. Moreover, high costimulatory signals result in phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)–mediated NFAT5, which interferes with FoxP3+ Treg induction. Blocking miRNA181a or NFAT5 increases Treg induction in murine and humanized models and reduces murine islet autoimmunity in vivo. These findings suggest targeting miRNA181a and/or NFAT5 signaling for the development of innovative personalized medicines to limit islet autoimmunity.

INTRODUCTION

Clinical type 1 diabetes (T1D) is presumed to develop from autoimmune destruction of the pancreatic insulin-producing β cells (1), resulting in hyperglycemia. The incidence of T1D is rising markedly, especially in young children with the appearance of multiple islet autoantibodies marking the onset of islet autoimmunity (2). Thereafter, the time from this asymptomatic phase of islet autoimmunity to progression to metabolic T1D is highly plastic, ranging from several months to more than two decades (3). A rapid progression to clinical T1D is indicative of multiple layers of tolerance defects and aberrant immune activation. However, despite recent insights into identifying a divergent autoantigen-responsive CD4+ T cell population in infants before developing islet autoimmunity (4), molecular underpinnings involved in triggering the onset of islet autoimmunity remain incompletely understood.

Peripheral T cell tolerance is mainly executed by regulatory T cells (Tregs). The X chromosome–encoded forkhead domain containing transcription factor Forkhead box protein P3 (FOXP3) is a lineage-specifying factor responsible for the differentiation and function of CD25+CD4+ Tregs (5, 6). Binding of a strong-agonistic antigen to the T cell receptor (TCR) on naïve CD4+ T cells under subimmunogenic conditions results in efficient FOXP3+ Treg induction (7–10). High doses of TCR ligands and strong costimulatory signals activate the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, thereby interfering with Treg induction (11). Therefore, control of PI3K signaling by phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) is essential for Treg function and lineage stability.

Ex vivo frequencies of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–DQ8–restricted insulin-specific Tregs were critically reduced during islet auto-immunity onset or in children with a fast progression to clinical T1D (12), accompanied by an increase in insulin-specific T follicular helper (TFH) precursor cells (13). In contrast, high frequencies of insulin-specific Tregs were associated with profound delays in progressing to symptomatic T1D (12). However, a mechanistic understanding of relevant promoters of T cell activation involved in triggering islet auto-immunity is still lacking.

On the basis of their ability to regulate cellular states including T cell activation, we focused on microRNAs (miRNAs) (14).miRNA-mediated gene regulation comprises a variety of mechanisms including the canonical function of target gene inhibition, relief of miRNA-mediated repression, or miRNAs that in dependence of cellular state and function, can contribute to a potential activation of targeting sites (15–17).

The nuclear factor of activated T cells 5 (NFAT5) represents a functionally and structurally unique member of this transcription factor family (18, 19). Besides its role in regulating transcription in response to hyperosmolar stimuli, NFAT5 exerts important functions after other stimuli including TCR-dependent mechanisms (20–22), whereas PI3K can contribute to NFAT5 activation (23).

Here, we provide evidence for a profound impairment of Treg induction during islet autoimmunity onset. We demonstrate that an miRNA181a-mediated enhanced signal strength of TCR stimulation and costimulation links increased NFAT5 expression with impaired Treg induction. An miRNA181a antagomir or a pharmacological NFAT5 inhibitor improves Treg induction and reduces murine islet autoimmunity in vivo.

RESULTS

Impaired Treg induction during human islet autoimmunity onset

We studied Treg induction in vitro using naïve CD4+ T cells from individual children with different durations of islet autoimmunity without clinical T1D (overview in fig. S1). Given the critical role of insulin epitopes as target autoantigens, we focused on insulin-specific Treg induction using highly pure naïve CD4+ T cells and premature withdrawal of TCR stimulation after 18 hours without transforming growth factor–β (11, 12). We therefore used previously established protocols using HLA-DQ8 insulin-specific monomers coated onto streptavidin-precoated plates (12).

During islet autoimmunity, onset insulin-specific Treg induction was significantly (P < 0.001) impaired compared to children without islet autoimmunity (Fig. 1A). Insulin-specific Tregs were first identified as CD4+CD3+CD127loCD25hi T cells (example in fig. S2A, upper row; for example, 0.302% of all CD4+CD3+ T cells were identified as CD127loCD25hi upon stimulation with HLA-DQ8 insulin-specific monomers). Within this, CD127loCD25hi population percentages of CD25hiFOXP3hi Tregs were assessed (fig. S2A, upper row; for example, 55.6% CD25hiFOXP3hi of 0.302% of CD127lowCD25hi cells). No FOXP3hi Tregs were identified upon stimulation with HLA-DQ8 control monomers (example in fig. S2A, lower row). The functionality of induced Tregs was demonstrated previously (12) and was confirmed in Treg suppression assays (fig. S2B). Consistent with the reduced insulin-specific Treg induction in children with onset of autoimmunity, frequencies of FOXP3intCD4+ T cells were significantly (P < 0.05) increased, thereby pointing to activated T cells (no autoimmunity versus recent onset of autoimmunity, 16.9 ± 8.4 versus 67.2 ± 11.3 CD25hiFOXP3int cells as a percentage of CD127loCD25hiCD4+ T cells, P < 0.05; Fig. 1B and fig. S2A).

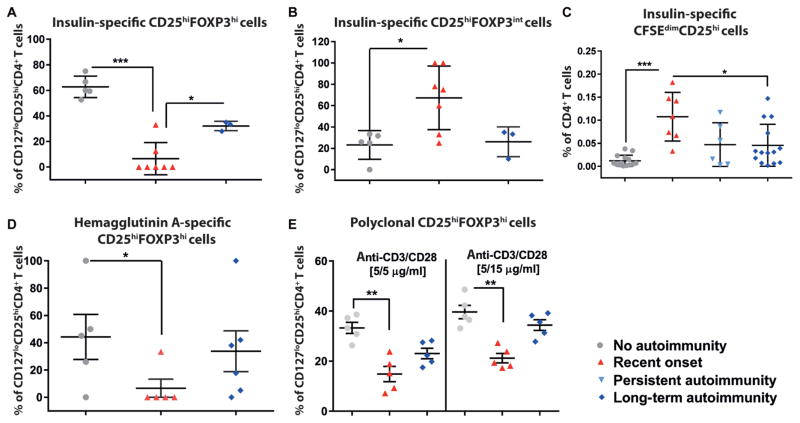

Fig. 1. Analyses on immune activation versus tolerance induction during islet autoimmunity onset.

(A) Frequencies of induced insulin-specific CD127loCD25hiFOXP3hiCD4+ Tregs after stimulation with insulin-specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–DQ8 monomers and interleukin 2 (IL-2) (100 U/ml) in vitro using T cells from children with different durations of islet autoimmunity [no autoimmunity (autoantibody-negative), n = 5; recent onset of autoimmunity (<5 years autoantibody positivity), n = 7; long-term autoimmunity (>10 years autoantibody positivity), n = 4). (B) Activated T cell (CD127loCD25hiFOXP3intCD4+ T cells) frequencies in assays from (A). (C) Proliferative responses of CD4+ T cells from children with different durations of islet autoimmunity to HLA-DQ8–restricted insulin-specific artificial antigen-presenting cells shown as percentages of CD25+CD45RO+CFSEdimCD4+ T cells (no autoimmunity, n = 14; recent onset of autoimmunity, n = 6; persistent autoimmunity, n = 6; long-term autoimmunity, n = 14). (D) Non–autoantigen-specific Treg induction in vitro with the hemaggluttinin A peptide (n = 5 per group). (E) CD127loCD25hiFOXP3hiCD4+ Treg frequencies after polyclonal Treg induction (n = 5 per group). Data are means ± SEM with individual values for data distribution. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test.

Upon stimulation with HLA-DQ8 insulin-specific tetramer-based artificial antigen-presenting cells (aAPCs; fig. S3), naïve CD4+ T cells from children with islet autoimmunity onset proliferated more vigorously (0.11 ± 0.01 CFSEdimCD25+ cells as a percentage of CD4+ T cells) compared to autoantibody negative children (0.01 ± 0.003, P < 0.001) and nondiabetic children with long-term autoimmunity (0.04 ± 0.01, P < 0.05; Fig. 1C). These findings suggest a higher sensitivity to antigenic stimulation during islet autoimmunity onset and are in line with studies showing best Treg induction in T cells that proliferated the least (7, 8, 10, 24). The reduced Treg induction potential during islet auto-immunity onset was confirmed in non–autoantigen-specific assays with a hemagglutinin A peptide [HA(307–319) epitope] and in polyclonal assays (Fig. 1, D and E).

Reduced Treg induction by miRNA181a-mediated increase in signal strength of stimulation

To mechanistically dissect the impaired Treg induction, we determined miRNA expression profiles by next-generation sequencing (NGS) using CD4+ T cells from children with or without islet autoimmunity (Fig. 2A and fig. S4A). Given the reduced Treg induction accompanied by increased T cell proliferation, we focused on miRNAs regulating signal strength of antigenic stimulation. Specifically, we identified enhanced miRNA181a abundance in ex vivo–stimulated CD4+ T cells from children with ongoing islet autoimmunity (Fig. 2, A and B). Murine studies had highlighted that miRNA181a regulates TCR signaling strength during T cell development in the thymus (25).

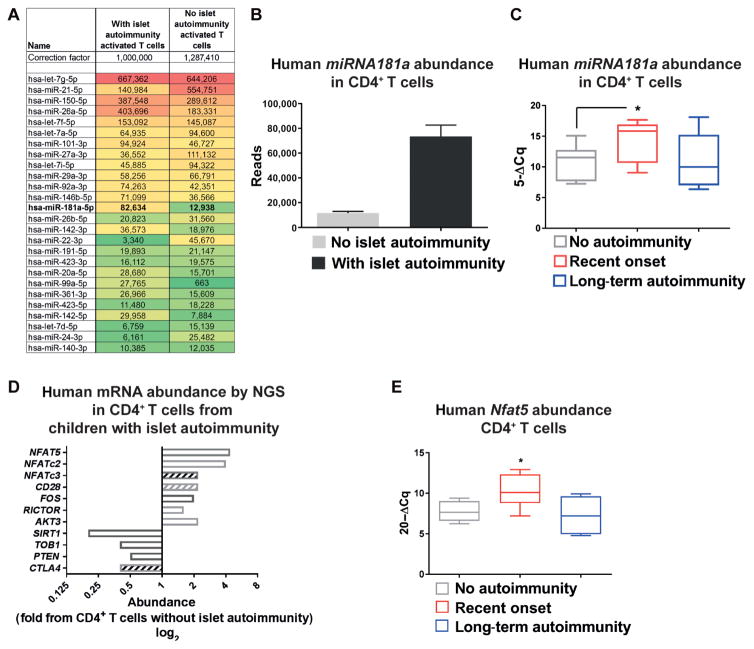

Fig. 2. miRNA181a targets NFAT5 in human CD4+ T cells.

(A) MicroRNA (miRNA) expression profiles in ex vivo CD4+ T cells with an activated phenotype from children with or without autoantibodies by next-generation sequencing (NGS) of pooled samples (n = 4 per group). A set of most abundant miRNAs relevant for T cell activation and or Treg induction is shown. (B) MiRNA181a reads by NGS as in (A) (n = 4 per group). (C) MiRNA181a abundance in ex vivo CD4+ T cells from children with different durations of autoimmunity (no autoimmunity, n = 9; recent onset of autoimmunity, n = 10; long-term autoimmunity, n = 5) by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). (D) Abundance of signaling intermediates involved in T cell activation in ex vivo CD4+ T cells from autoantibody-negative or autoantibody-positive children by NGS from pooled samples (n = 4 per group). Open bars, predicted as direct targets of miRNA181a; hatched bars, not predicted as direct targets of miRNA181a. (E) Human Nfat5 mRNA abundance in ex vivo CD4+ T cells from individual children with or without islet autoimmunity by RT-qPCR (no autoimmunity, n = 6; recent onset of autoimmunity, n = 7; long-term autoimmunity, n = 6). Data are means ± SEM (B) or are presented as box and whisker plots with minimum to maximum values for data distribution (C and E). *P < 0.05, Student’s t test. PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; NFAT5, nuclear factor of activated T cells 5; CTLA4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4; TOB1, transducer of ERRB2 1.

Validation experiments in CD4+ T cells from individual children with onset of autoimmunity showed increased miRNA181a abundance (Fig. 2C). By contrast, miRNA181a expression in CD4+ T cells from nondiabetic children with long-term autoimmunity was as low as that in CD4+ T cells from children without ongoing islet auto-immunity (Fig. 2C).

We used NGS to determine miRNA181a-mediated regulation on mRNA expression in CD4+ T cells, focusing on target genes regulating signal strength of antigenic stimulation. Consistent with enhanced miRNA181a expression, CD4+ T cells from autoantibody-positive children had diminished expression of target genes that negatively affect T cell activation, such as Pten, transducer of ERBB2, 1 (Tob1), and cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 (Ctla4) (Fig. 2D).

In addition, predicted miRNA181a target genes that promote immune activation (Fig. 2D) were up-regulated, accompanied by enhanced CD28 expression, suggesting increased costimulatory signaling and enhanced signal strength during autoimmunity. Accordingly, the expression of NFAT transcription factor family members was enhanced (Fig. 2, D and E, and fig. S4F), with Nfat5 being most prominently increased (Fig. 2D).

Validation experiments using CD4+ T cells from individual children confirmed increased Nfat5 expression during islet autoimmunity onset (Fig. 2E), accompanied by reduced abundance of negative regulators of T cell activation, such as Pten, Tob1, and Ctla4 (fig. S4, C to E). Accordingly, an miRNA181a-mediated suppression of Pten promotes PI3K signaling, which, in turn, can contribute to NFAT5 activation (23).

Promotion of NFAT5 expression by enhancing miRNA181a activity

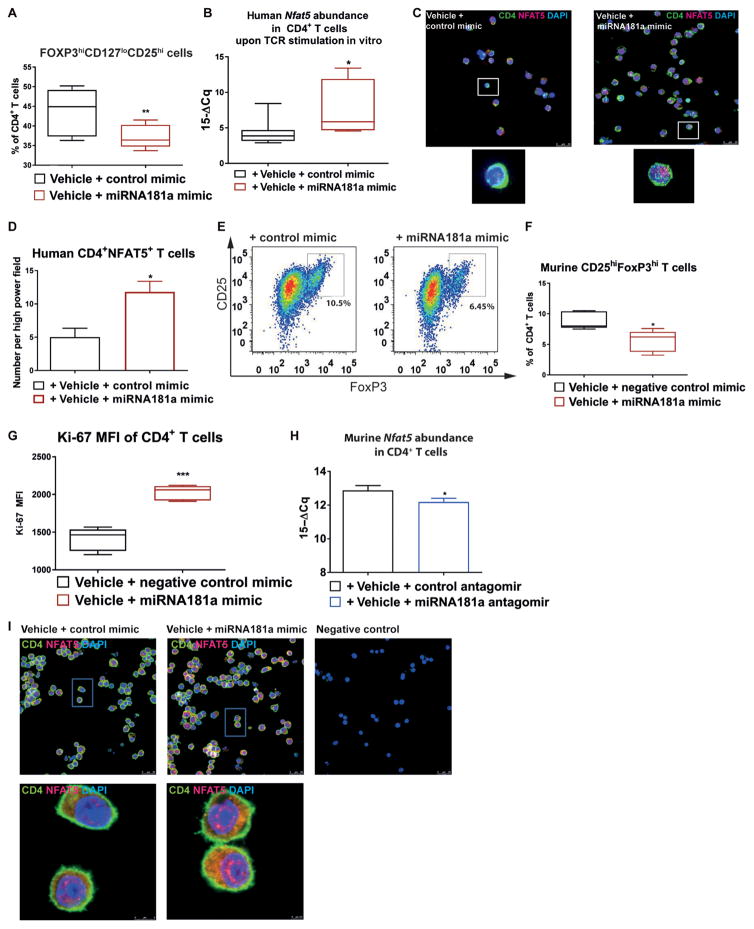

Next, we studied whether modulating miRNA181a activity affects Treg induction during autoimmunity. miRNA181a mimics (fig. S5) were delivered to CD4+ T cells using established chitosan-coated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles (26–28). An miRNA181a mimic significantly lowered Treg induction (human, P < 0.01; murine, P < 0.05) while enhancing Nfat5 abundance (P < 0.05) and cellular proliferation (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3, A to G). In contrast, blocking miRNA181a significantly reduced Nfat5 abundance (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3H). Furthermore, stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy showed that an miRNA181a mimic distinctly enhanced nuclear NFAT5 expression (Fig. 3I). Higher costimulation interfered with FoxP3+ Treg induction, increased Nfat5, and reduced forkhead box protein O1 (Foxo1) expression (fig. S6, A and B).

Fig. 3. Human Treg induction using sub-immunogenic TCR stimulation with an miRNA181a antagomir or mimic.

(A) Frequencies of induced CD127loCD25hiFOXP3hiCD4+ Tregs after polyclonal T cell receptor (TCR) stimulation of naïve CD4+ T cells from healthy individuals for 18 hours with IL-2 (100 U/ml) with an miRNA181a mimic (n = 5 independent experiments). (B) Human Nfat5 mRNA abundance by RT-qPCR upon TCR stimulation of CD4+ T cells from healthy individuals for 48 hours with a control mimic or an miRNA181a mimic (n = 8 per group). (C) Representative confocal microscopy images of human CD4+ T cells from healthy individuals stimulated for 54 hours with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 with a control or miRNA181a mimic and IL-2 (100 U/ml) stained for CD4, NFAT5, and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (n = 5 individuals/samples for either control mimic or miRNA181a mimic, with five images per individual/sample; scale bar, 25 μm). (D) Human NFAT5 abundance in samples from (C) (n = 5 per group). (E) Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots indicating induced CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs after TCR stimulation and IL-2 (100 U/ml) from Balb/c mice with a control or miRNA181a mimic. (F) Frequencies of CD25hiFoxP3hiCD4+ Tregs as in (E) (n = 5 independent experiments). (G) Ki-67 expression in induced Tregs as in (E) (n = 5 per group). (H) Nfat5 mRNA abundance in Balb/c CD4 T cells after TCR stimulation for 54 hours with an miRNA181a or control antagomir and IL-2 (100 U/ml) (n = 5 per group). (I) Representative stimulated emission depletion microscopy images of Balb/c CD4+ T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 and either a control or miRNA181a mimic and IL-2 (100 U/ml) for 54 hours, stained for CD4, NFAT5, and DAPI [n = 4 mice/samples for control mimic (10 images per sample) and n = 5 mice/samples for miRNA181a mimic (12 images per sample)]. Scale bars, 25 μm. Negative control slides were incubated with secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbitSTAR635P, Abberior) only. Data are presented as box and whisker plots with minimum to maximum values for data distribution (A, B, F, and G) or are means ± SEM (D and H).*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

Blocking miRNA181a significantly enhanced human Treg induction (without islet autoimmunity, P < 0.001; long-term autoimmunity, P < 0.01; with T1D, P < 0.01) (Fig. 4A). The FOXP3 Treg-specific demethylated (TSDR) region shows the most distinct differences concerning the methylation status of the FOXP3 locus: It is completely demethylated in Tregs and fully methylated in conventional T cells and in Tregs induced by continuous TCR stimulation in vitro (29). We recently had demonstrated that subimmunogenic stimulation of human naïve CD4+ T cells in vitro resulted in higher Treg induction efficacy and improved Treg stability, as seen from restimulation cultures using sort-purified induced Tregs (12). Here, using Treg induction with naïve CD4+ T cells and early withdrawal of TCR stimulation, after 14 hours, some T cells had already up-regulated high FOXP3 expression and, at that early time point, presented with a reduced FOXP3 TSDR methylation (fig. S7). An miRNA181a antagomir significantly lowered the FOXP3 TSDR methylation in such early FOXP3hiCD4+ T cells (P < 0.001) (fig. S7).

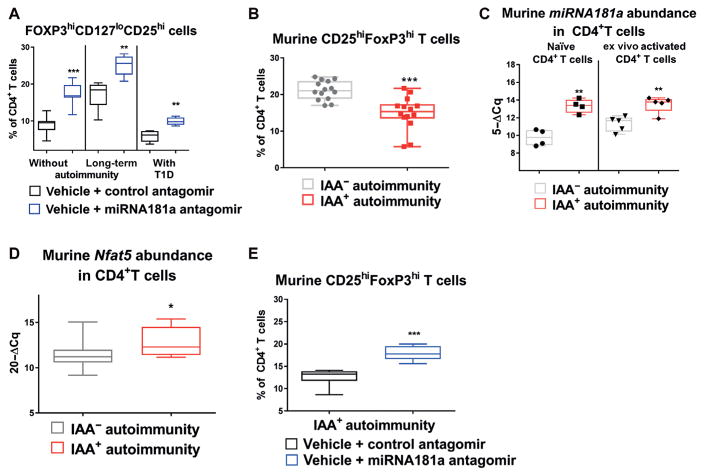

Fig. 4. Murine Treg induction in the presence of an miRNA181a antagomir or mimic.

(A) Effects of an miRNA181a antagomir on Treg induction in cells from children without islet autoimmunity (n = 7 for control and n = 8 for miRNA181a antagomir), with islet auto-immunity and no clinical disease (n = 5 per group), or with established type 1 diabetes (T1D) (n = 5 per group). (B) Frequencies of induced CD25hiFoxP3hiCD4+ Tregs from in vitro polyclonal Treg induction assays with naïve T cells from nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice with or without insulin autoantibody (IAA+) autoimmunity (n = 14 per group, IAA+NOD: median age, 118 days and IQR, 74 to 134 days; IAA−NOD: median age, 99 days and IQR 51 to 120 days). (C) MiRNA181a expression in ex vivo CD4+ T cells with a naïve or activated phenotype from NOD mice with or without IAA+autoimmunity (n = 5 per group). (D) Nfat5 mRNA abundance in ex vivo CD4+ T cells from NOD mice with (n = 8) or without (n = 9) IAA+ autoimmunity. (E) Frequencies of CD25hiFoxP3hi Tregs induced with sub-immunogenic TCR stimulation for 18 hours from naïve CD4+ T cells from NOD mice with or without IAA+autoimmunity and a control or miRNA181a antagomir (n = 6 per group). Data are presented as box and whisker plots with minimum to maximum values for data distribution. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test.

Mechanisms of impaired Treg induction in murine islet autoimmunity

To mechanistically dissect Treg induction during islet autoimmunity, we next studied nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice, which share many similarities with human T1D (30–32). Nondiabetic NOD mice with recent onset of insulin autoantibodies (IAAs) likewise showed significantly impaired Treg induction (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B), accompanied by significantly enhanced miRNA181a (P < 0.01) and Nfat5 (P < 0.05) abundance ex vivo (Fig. 4, C and D). Moreover, the percentage of cells that are NFAT5-positive (and the mean fluorescence intensity of the entire population) was increased in CD4+ T cells from IAA+NOD mice (fig. S8, A and B).

In ex vivo Tregs of IAA+NOD mice, miRNA181a expression was reduced, whereas Nfat5 and Pten expression was unaltered when compared to IAA−NOD mice (fig. S8, C to E). Moreover, CD4+ T cells from IAA+NOD mice had higher miRNA181a expression upon TCR stimulation, and ex vivo PTEN protein expression was reduced (fig. S8, F to H), thereby supporting PI3K signaling and NFAT5 activation.

Next, to dissect a potential involvement of hypertonicity-related signaling in mediating Nfat5 enhancement, we analyzed A kinase anchoring protein 13 (Akap13) and serum/glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (Sgk1) expression in CD4+ T cells from IAA+NOD mice. In contrast to Nfat5, Akap13 and Sgk1 mRNAs were unaltered during IAA+ autoimmunity (fig. S9, A and B). Likewise, AKAP13hi T cells were unchanged (fig. S9, C and D). Furthermore, Treg induction was unaltered with T cells from AKAP13 haploinsufficient (+/−) animals (33) compared to wild-type (WT) T cells or with T cells from IAA+NOD mice with an Akap13 small interfering RNA (siRNA) compared to control siRNA (fig. S9, E to H). Again, blocking miRNA181a distinctly enhanced Treg induction using naïve CD4+ T cells from IAA+NOD mice (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4E).

Treg induction potential in CD4+ T cells from NFAT5ko mice and PTEN Tg mice

Using loss-of-function experiments, naïve CD4+ T cells from NFAT5 knockout (NFAT5ko) mice (34) showed a significantly increased Treg induction potential [CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs (percentage of CD4+ T cells), 17.1 ± 2.8 versus 30.3 ± 1.2, P < 0.01; Fig. 5, A and B]. Accordingly, Pten and Foxo1 mRNA abundance was significantly up-regulated in activated CD4+ T cells from NFAT5ko mice (P < 0.05) (fig. S10, A and B). An improved Treg induction was also seen when modifying TCR signal strength or costimulation (fig. S10, C to E).

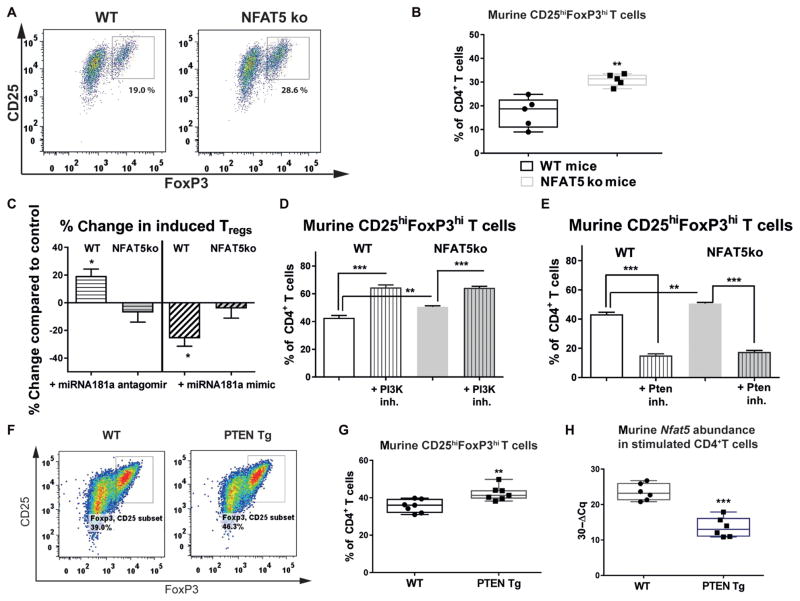

Fig. 5. Treg induction potential in CD4+ T cells from NFAT5ko mice and PTEN Tg mice.

(A) Representative FACS plots indicating CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs upon Treg induction with subimmunogenic TCR stimulation and IL-2 (100 U/ml) from wild-type (WT) or NFAT5 knockout (NFAT5ko) mice. (B) Frequencies of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs upon Treg induction as in (A) (n = 5 experiments). (C) Percent change in Treg induction with subimmunogenic TCR stimulation and IL-2 (100 U/ml) from WT or NFAT5ko mice with an miRNA181a antagomir or mimic. Percent change refers to the difference in Treg frequency obtained with either a control mimic or antagomir (n = 4 experiments). (D and E) Frequencies of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs upon Treg induction with low-dose TCR stimulation (0.01 μg/ml of anti-CD3) and IL-2 (100 U/ml) in combination with a PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase) (D) or a PTEN inhibitor (inh.) (E) (n = 4). (F) Representative FACS plots indicating CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs upon Treg induction with subimmunogenic TCR stimulation and IL-2 (100 U/ml) from WT or PTEN transgenic (Tg) mice. (G) Frequencies of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs as in (F) (n = 7 per group). (H) Nfat5 mRNA expression in CD4+ T cells after TCR stimulation for 54 hours from WT or PTEN Tg mice (n = 6 per group). Data are presented as box and whisker plots with minimum to maximum values for data distribution (B, G, and H) or are means ± SEM (C to E). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test.

Blocking miRNA181a increased induced Tregs only with naïve CD4+ T cells from WT animals (WT + miRNA181a antagomir, 19.8 ± 6.9% increase in induced CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs compared to control mice, P < 0.05; Fig. 5C) and not with naïve CD4+ T cells from NFAT5ko animals (Fig. 5C). Accordingly, Treg induction was unaltered with naïve CD4+ T cells from NFAT5ko mice and an miRNA181a mimic (Fig. 5C). Modulating miRNA181a activity likewise did not affect Treg induction with naïve CD4+ T cells from NFAT5ko mice and low-dose anti-CD3 stimulation (fig. S11, A to D). PI3K inhibition improved, whereas a PTEN inhibitor decreased, Treg induction in T cells from both WT and NFAT5ko mice (Fig. 5, D and E).

Next, to study the association between costimulation, PTEN, and NFAT5 signaling with Treg induction, we used naïve CD4+ T cells from PTEN transgenic (Tg) animals (35), which harbor constitutively increased PTEN expression and reduced PI3K activation. High PTEN expression significantly enhanced Treg induction compared to WT T cells (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5, F and G). The increased Treg induction from PTEN Tg animals was accompanied by reduced Nfat5 expression, enhanced Foxo1 expression in CD4+ T cells ex vivo (fig. S12, A and B), and lower Nfat5 expression after TCR stimulation (Fig. 5H). An miRNA181a mimic reduced, whereas an miRNA181a antagomir enhanced, Treg induction and inhibited NFAT5 expression using naïve CD4+ T cells from PTEN Tg animals also with subimmunogenic TCR stimulation (figs. S12, C and D, and S13, A and B).

Enhancement of Treg induction by a specific NFAT5 inhibitor

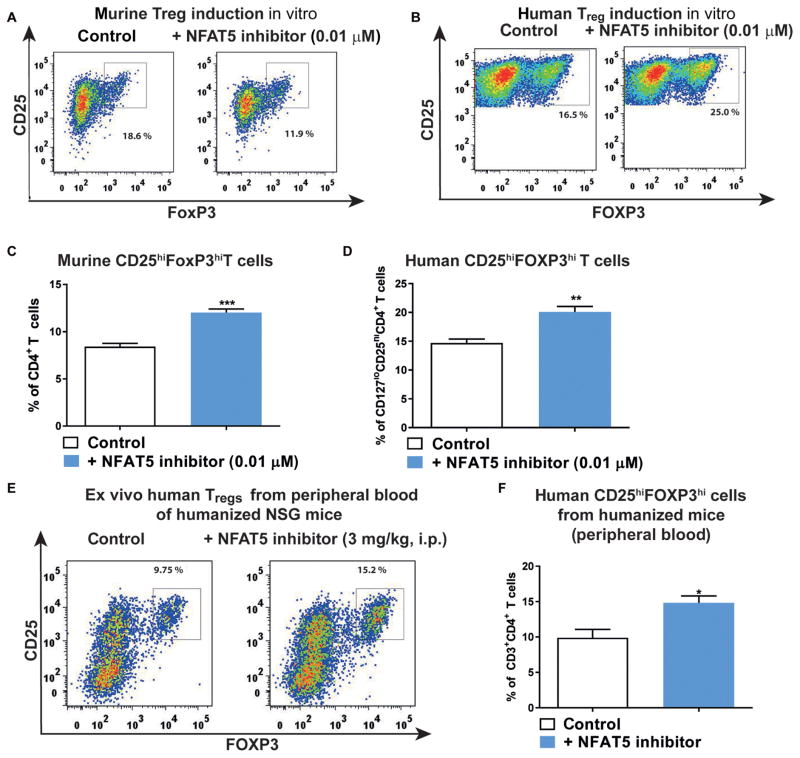

Therapeutic agents that can specifically inhibit NFAT5 have been lacking until now. A recently identified compound was shown to block the proinflammatory NFAT5 activity by inhibiting Nfat5 transcriptional activation without affecting NFAT1 to NFAT4, nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, and cAMP (adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate) response element–binding protein (CREB) activity, excluding potential off-target effects (36). NFAT5 inhibition improved murine and human Treg induction (Fig. 6, A to D) in vitro in WT and PTEN Tg mice, as well as in a humanized mouse model in vivo (Fig. 6, E and F, and fig. S14, A to F). Humanized mice are immunodeficient mice that, after reconstitution with human hematopoietic cells or tissues, do develop a human immune system with a highly diverse TCR repertoire. These mice permit the assessment of human T cell responses in vivo. Here, we made use of the murine MHCII (major histocompatibility complex class II)–deficient, HLA-DQ8 Tg NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl (NSG) mouse model (12).

Fig. 6. A NFAT5 inhibitor increases Treg induction.

(A and B) Representative FACS plots indicating CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs upon murine (A) or human (B) Treg induction with subimmunogenic TCR stimulation and IL-2 (100 U/ml) using naïve CD4+ T cells with or without NFAT5 inhibitor (0.01 μM). (C and D) Frequencies of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs upon Treg induction as in (A) and (B) (n = 5 experiments). (E) Representative FACS plots indicating ex vivo CD4+CD25+FOXP3hi Tregs in peripheral blood of humanized NSG mice after treatment with either saline or a specific NFAT5 inhibitor [3 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.)] for 4 days. (F) Frequencies of CD4+CD25+FOXP3hi Tregs as in (E) (n = 5 per group). Data are means ± SEM (C, D, and F). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test.

Amelioration of murine islet autoimmunity by an miRNA181a antagomir or an NFAT5 inhibitor in vivo

Next, we tested the impact of blocking miRNA181a to modulate islet autoimmunity in IAA+NOD mice in the absence of symptomatic T1D in vivo. The miRNA181a antagomir [10 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (ip)] every other day for 14 days enhanced FoxP3+ Tregs in the peripheral blood (Fig. 7, A to C). The fact that the Treg enhancement was significant in peripheral blood (P < 0.01) but not in the lymph nodes suggests that a further miRNA181a antagomir dose titration might be needed and/or a daily application.

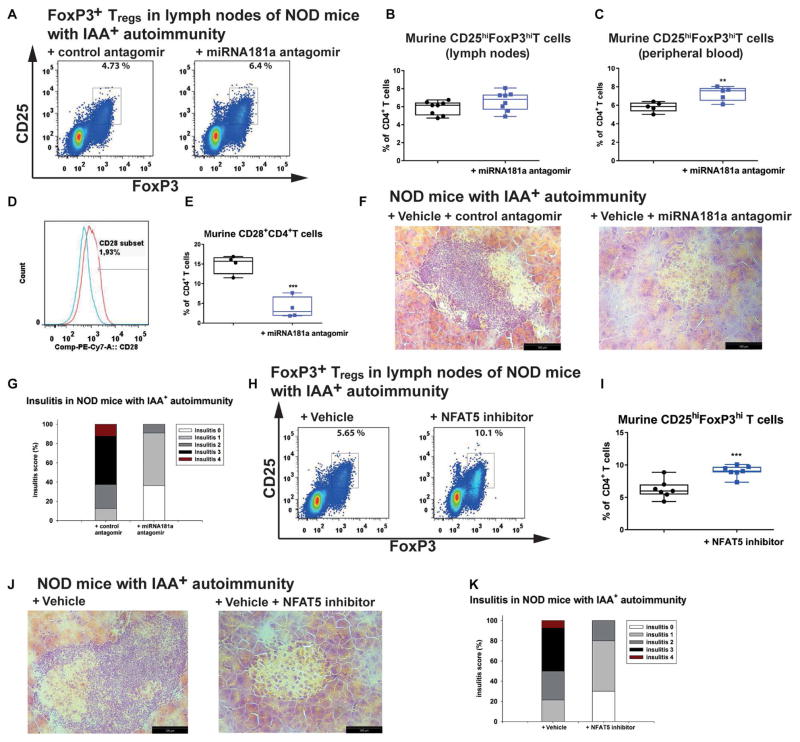

Fig. 7. NFAT5 or miR181a inhibition in vivo improves islet autoimmunity.

(A) Representative FACS plots indicating ex vivo CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs from the lymph nodes of IAA+NOD mice treated with an miRNA181a or control antagomir for 14 days with 10 mg/kg ip every other day. (B) Summary graphs for CD4+CD25+FoxP3hi Tregs as in (A) (n = 8 per group). (C) Frequencies of ex vivo CD4+CD25+FoxP3hi Tregs from peripheral blood of IAA+NOD mice treated as in (A) (n = 5 per group). (D) Representative histogram of CD28 staining in ex vivo CD4+ T cells from IAA+NOD mice treated with a control antagomir (red) or miRNA181a antagomir (blue). (E) Summary graph for CD28+ T cells as in (D) (n = 4 per group). (F) Representative hematoxylin and eosin–stained pancreas cryosections from IAA+NOD mice treated as in (A) (n = 5 mice per group/3 sections per mouse; scale bars, 100 μm). (G) Grading of insulitis from mice as in (F) (n = 5 per group). (H) Representative FACS plots indicating ex vivo CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs from the lymph nodes of IAA+NOD mice treated with an NFAT5 inhibitor or vehicle control for 14 days with 3 mg/kg ip every day. (I) Summary graphs for CD4+CD25+FoxP3hi Tregs as in (H) (n = 7 per group). (J) Representative hematoxylin and eosin–stained pancreas cryosections from IAA+NOD mice treated as in (H) (n = 5 mice per group/3 sections per mouse; scale bars, 100 μm). (K) Grading of insulitis from mice as in (J) (n = 5 per group). Data are presented as box and whisker plots with minimum to maximum values for data distribution. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test.

Blocking miRNA181a significantly enhanced ex vivo PTEN expression in CD4+ T cells from the lymph nodes of IAA+NOD mice (P < 0.05) (fig. S15, A and B) while significantly reducing CD28 expression (P < 0.001) (Fig. 7, D and E) and lowering IAA levels (P < 0.01) (fig. S15C). The amelioration of autoimmune activation was verified by histopathological and immunofluorescence analyses of pancreatic sections, which showed a reduction in T cell infiltration (Fig. 7, F to G, and fig. S15D).

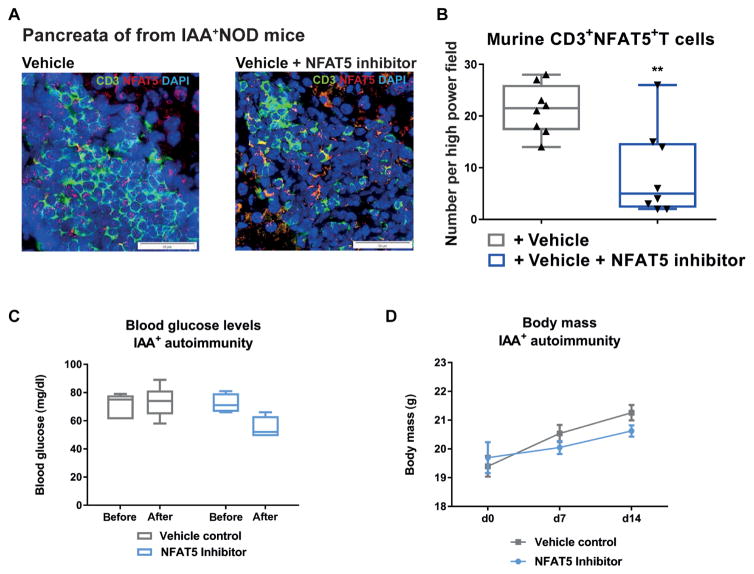

Applying an NFAT5 inhibitor to IAA+NOD mice at 3 mg/kg ip every day for 14 days significantly enhanced FoxP3+ Tregs in lymph nodes (P < 0.001) (Fig. 7, H and I) and reduced pancreatic immune infiltration (Fig. 7, J and K, and fig. S15F). In addition, NFAT5 inhibition distinctly reduced NFAT5 expression in pancreas-infiltrating T cells from IAA+NOD mice (Fig. 8, A and B, and fig. S15G). Blocking NFAT5 did not cause any changes in metabolic parameters (for example, body mass and blood glucose; Fig. 8, C and D).

Fig. 8. NFAT5 inhibition in vivo decreases NFAT5-expressing T cells in the pancreas in the absence of metabolic side effects.

(A) Representative confocal microscopy images of pancreatic cryosections of NOD mice given a vehicle control (left) or NFAT5 inhibitor (right) at 3 mg/kg ip every day for 14 days. Staining for CD3 (green), NFAT5 (red), and DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 50 μm. (B) Frequencies of CD3+NFAT5+ T cells in the pancreata from NOD mice treated as in (A) (n = 4 mice per group/2 sections per mouse). (C) Blood glucose levels in NOD mice treated as in (A). (D) Body mass development in NOD mice treated as in (A). (C and D) n = 4 per group for NFAT5 inhibitor and n = 5 per group for vehicle control. Data are presented as box and whisker plots with minimum to maximum values for data distribution (B and C) or are means ± SEM (D). **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

DISCUSSION

A better understanding of the molecular underpinnings affecting immune tolerance defects is pivotal to develop personalized medicines that limit autoimmune progression. Highly variable progression from islet autoimmunity to clinical T1D (3) underscores plasticity in regulating immune activation versus tolerance. Therefore, T cells from non-diabetic children with ongoing islet autoimmunity offer a valuable resource for studying signaling pathways involved in this plasticity.

An important weakness of this study is that no longitudinal samples from individual children have been available to assess and integrate Treg induction potential from naïve CD4+ T cells in accordance with the duration of islet autoimmunity over time. Therefore and given the differences in the median age within respective disease groups, within the present human data set, a confounding role of age per se in influencing Treg induction potential from naïve CD4+ T cells cannot be excluded.

Here, we provide evidence for a broad Treg induction impairment during islet autoimmunity onset. Consistent with the reduced Treg induction potential, proliferation and frequencies of FOXP3intCD4+ T cells were enhanced, indicative of T cell activation, thereby limiting possibilities of subimmunogenic stimulation necessary for efficient FOXP3+ Treg induction (7, 11, 24).

By contrast, with naïve CD4+ T cells from nondiabetic children with long-term autoimmunity, the Treg induction potential was restored to frequency observed in children without autoimmunity, thereby suggesting that children with long-term autoimmunity might have regulated autoimmune activation or might at least be in a transient state of immune tolerance. Accordingly, children with long-term autoimmunity phenotypes show an accumulation of protective genotypes in T1D susceptibility genes (37), most notably, IL-2, IL2-Rα, INS VNTR, and IL-10. In line, such children with long-term autoimmunity harbored TFH precursor cell frequencies as low as autoantibody-negative children (13), accompanied by an increase in insulin-specific Tregs (12).

As one possible means to explain this Treg induction impairment, we identified enhanced miRNA181a abundance in CD4+ T cells during islet autoimmunity onset. Murine miRNA181a regulates signal strength of stimulation by modulating the sensitivity to antigenic stimulation and signaling thresholds in CD4+ T cells during thymic T cell development (25). These properties of miRNA181a suggest that an increased sensitivity to antigenic stimulation boosts T cell activation, thereby promoting islet autoimmunity and antagonizing Treg induction. Accordingly, an miRNA181a mimic distinctly impeded, whereas an miRNA181a antagomir enhanced, human and murine Treg induction. The miRNA181a-mediated enhancement of signal strength of stimulation also involves the suppression of negative regulators of T cell activation such as the phosphatase PTEN. PTEN functions as a key signaling intermediate controlling the activation of PI3K. Consequently, miRNA181a-mediated PTEN inhibition promotes PI3K signaling, which, in turn, can contribute to NFAT5 activation (23). Therefore, blockade of PTEN signaling by miRNA181a might function as one possible mechanism of indirect regulation to boost NFAT5 expression. Accordingly, in CD4+ T cells from children with ongoing islet auto-immunity, we find enhanced miRNA181a abundance, together with a decrease in Pten and an increase in Nfat5 expression. Moreover, upon miRNA181a blockade in IAA+NOD mice, we identify increased PTEN expression in CD4+ T cells, accompanied by reduced NFAT5 expression.

Furthermore, the observed NFAT5 induction by miRNA181a might also result from additional indirect control of repression pathways and/or potentially involve relief of miRNA181a-mediated repression of NFAT5 (17, 38). In addition, the increase in signal strength of stimulation induced by miRNA181a includes an enhancement of costimulatory signals such as CD28 (25). Specifically, increased miRNA181a levels promoted CD28 expression while reducing CTLA4 surface expression. CD28 signaling triggers PI3K signaling (11), which can contribute to NFAT5 activation (23), thereby offering a potential additional explanation on how miRNA181a might indirectly contribute to NFAT5 up-regulation. Accordingly, we observe enhanced CD28 mRNA abundance in CD4+ T cells from children with ongoing islet autoimmunity. Moreover, miRNA181a blockade in vivo significantly reduced CD28 expression in CD4+ T cells while reducing murine islet autoimmunity.

In the absence of NFAT5, Treg induction was enhanced, T cells harbored increased Pten and Foxo1 expression, both critically involved in favoring Treg induction. Specifically, Foxo1 can directly regulate Treg differentiation (39). In contrast, high PI3K/Akt signaling activity inactivates Foxo1 proteins by excluding them from the nucleus (39).

These results suggest that a low activity of an miRNA181a-NFAT5 signaling axis can link improved FOXP3 inducibility with limited PI3K/Akt/mTOR activation. Accordingly, PTEN-deficient T cells showed a constitutive activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, accompanied by impaired FoxP3+ Treg induction, which was restored by PI3K inhibition.

In summary, here, we show that an miRNA181a/NFAT5 axis critically contributes to an impairment of Treg induction during islet autoimmunity. These findings suggest that targeting miRNA181a and/or NFAT5 signaling could contribute to the development of translational strategies aimed at inhibiting the signaling intermediates of T cell activation to limit T1D islet autoimmunity while improving Treg induction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This study was designed to investigate Treg induction in T cells from children at an early state of islet autoimmunity without symptomatic T1D. Therefore, peripheral blood from children who are first-degree relatives of T1D patients that consented to the Munich Bioresource project was analyzed. Treg induction during different phases of islet autoimmunity was assessed. T cell–specific miRNAs and miRNA-regulated pathways involved in Treg induction were studied using NGS and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analyses. Treg induction and autoimmune modulation upon miRNA181a or NFAT5 blockade were analyzed in NOD mice and in humanized NSG mice. Specifically, we focused on miRNA181a because of its implication in mediating signal strength of antigenic stimulation and on the role of Nfat5 in interfering with Treg induction. We performed loss- and gain-of-function studies using NFAT5ko animals and PTEN-overexpressing mice to assess the role of an miRNA181a/NFAT5 axis in Treg induction. NOD mice were monitored for weight changes, blood glucose levels, and clinical signs throughout the experiment. The investigators were not blinded, and no animals were excluded because of illness. Primary data are located in table S1.

Human subjects and blood samples

Blood samples were collected from children or adults who are first degree relatives of T1D patients and who consented to the Munich Bioresource project (approval no. 5049/11, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany). All subjects have been already enrolled into longitudinal studies with prospective follow-up from birth (40–42) with the documented age of islet autoantibody seroconversion (initiation of islet autoimmunity). Venous blood was collected using sodium heparin tubes, and blood volumes collected were based on European Union guidelines, with a maximal blood volume of 2.4 ml/kg of body weight. Subjects have been stratified on the basis of the presence or absence of multiple islet autoantibodies (with or without pre-T1D) and on the basis of the duration of islet autoantibody positivity. Details on included subjects can be found in the Supplementary Materials. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by density centrifugation over Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare). Human dendritic cells (DCs) were purified to >90% purity from autologous PBMC samples using the Blood DC Isolation kit II human (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Human CD4+ T cells were isolated at a purity of >90% from fresh PBMCs via positive magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) enrichment, using CD4 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec).

Mice

Female NOD/ShiLtJ mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory and stratified according to their IAA status (IAA+NOD mice: median age, 118 days; interquartile range (IQR), 74 to 134 days; IAA−NOD mice: 99 days; IQR, 51 to 120 days). Analyses of murine IAAs were carried out from serum, as described previously using a mouse high-specificity/sensitivity competitive IAA assay in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay format (43) or a protein A/G radiobinding assay (42). For more details, see the Supplementary Materials. NFAT5ko mice were provided by C. Küper. PTEN Tg mice were provided by M. Serrano. AKAP13 (Brx) haploinsufficient mice were received from J. Segars. NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid H2-Ab1tm1Gru Il2rgtm1Wjl Tg(HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQB1)1Dv//Sz (NSG HLA-DQ8) mice were developed by L. Shultz at the Jackson Laboratory. Ethical approval for all mouse experimentations has been received by the District Government of Upper Bavaria, Munich, Germany. No animals were excluded because of illness or outlier results; therefore, no exclusion determination was required. Further information on ko and Tg mouse lines can be found in the Supplementary Materials. CD4+ T cells were isolated at >90% purity by positive MACS enrichment using CD4 Biotin (BD Biosciences) and streptavidin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec).

Treg induction using subimmunogenic TCR stimulation in vitro

Polyclonal TCR stimulation

Naïve CD4+ T cells were defined as CD3+CD4+CD45RA+CD45RO− CD127+CD25− (human) or as CD4+CD25−CD44− (murine) and sorted with the BD FACS Aria III at a purity of >95%. A total of 10,000 (murine assays) or 100,000 (human assays) naïve CD4+ T cells per well were cultured for 18 hours in 96-well plates precoated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies (5 μg/ml, unless indicated otherwise). Sub-immunogenic TCR stimulation was achieved by pipetting cells into uncoated wells, after 18 hours, where they were cultured for an additional 36 hours.

Insulin-specific TCR stimulation

Human naïve CD4+ T cells were sorted as described above and cultured at 500,000 per well in 96-well plates precoated with streptavidin and HLA-DQ8 (5 μg/ml) monomers in complex with either insulin mimetopes or control peptides (for information on peptides, see the Supplementary Materials). Anti-CD28 (50 ng/ml) was added to the medium. Subimmunogenic TCR stimulation was achieved by changing the medium and pipetting the cells into uncoated wells after 12 hours. Analysis was performed after an additional 36 hours. The insulin specificity of T cell responses has been verified previously using HLA-DQ8– restricted insulin-specific tetramers and control tetramers fused to irrelevant peptides (12), sort purification of tetramer+ T cells, and insulin-specific restimulation (12).

DC-dependent Treg induction

A total of 500,000 human naïve CD4+ T cells per well were cocultured with autologous carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)– labeled DCs at a ratio of 100:1 in the presence of a human HA epitope. After 12 hours, antigen-presenting cells were removed, and CD4+ T cells were sorted as CFSE−, followed by a culture for an additional 36 hours in new wells, without further peptide stimulation. Information on peptides can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

CFSE T cell proliferation assays

CD4+CD25− T cells were labeled with CFSE (0.25 μM) and propagated with aAPCs for 5 days. Information on aAPCs is in the Supplementary Materials. After 5 days, cells were analyzed by FACS (fluorescence-activated cell sorting). Responsiveness was measured by the presence and quantity of CD4+CD25+CFSEdim T cells.

Isolation and processing of miRNAs and mRNAs

For the isolation of miRNAs and mRNAs, the miRNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and purity were determined by a NanoDrop (Epoch, Biotek) or an RNA Nano Chip and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). For complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis, the Universal cDNA Synthesis kit II (for miRNAs; Exiqon) or the iScript cDNA Synthesis kit (for mRNAs; Bio-Rad) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was performed using the ExiLENT SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (for miRNAs; Exiqon) or the SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (for mRNAs; Bio-Rad) and a CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad). Information on primers can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

miRNA/mRNA expression profiling

We used NGS for expression profiling in a test set of each four pooled samples of naïve versus activated CD4+ T cells purified from children with or without ongoing islet autoimmunity. cDNA libraries for miRNA and mRNA sequencing were transcribed from total RNA using the NEBnext Multiplex Small RNA Library Prep Set and NEBnext mRNA Library Prep Master Mix (New England Biolabs), and mRNA library preparation was conducted with TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation kit v2 (Illumina), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. NGS was performed on a HiSeq2000 (Illumina), with 50–base pair single-end reads for small RNA and mRNA using Illumina reagents and following the manufacturer’s instruction. Information on data processing and statistical analysis can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Application of miR181a antagomir or mimic to human and murine CD4+T cells

Chitosan-coated PLGA nanoparticles (for information on nanoparticle preparation, characterization, and testing, refer to the Supplementary Materials) were loaded with an miR181a-5p inhibitor (miRCURY LNA microRNA inhibitor, Exiqon) or an miR181a-5p mimic (miRCURY LNA microRNA mimic, Exiqon) at a nanoparticle to inhibitor/mimic ratio of 50:1 and incubated at room temperature for 30 min, with gentle agitation (sequences can be found in the Supplementary Materials). The loaded nanoparticles were added to the wells of a polyclonal Treg induction assay at a final concentration of 0.95 ng/μl per 100,000 cells for human cells and 0.19 ng/μl per 10,000 cells for murine cells (for miR181a inhibitor) and 2.1 ng/μl per 100,000 cells for human assays and 0.21 ng/μl per 10,000 cells for murine assays (for miR181a-5p mimic). As a control, a negative control mimic or inhibitor with no known targets was used at the same concentration.

Application of PI3K, PTEN, and NFAT5 inhibitors

The PTEN inhibitor SF1670 (Abcam) was added at a concentration of 0.5 μM directly with the start of the stimulation of naïve CD4+ T cells, and the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (final concentration, 10 μM; SYNkinase) was added after 18 hours of TCR stimulation. A small-molecule inhibitor of NFAT5, developed by W.-U.K. (36), was added simultaneously to the TCR stimulation at a concentration of 0.01 μM or 0.01 nM in case of low-dose anti-CD3 stimulation.

In vivo NFAT5 inhibition and miRNA181a antagomir application

For assessment of in vivo NFAT5 inhibition, IAA+NOD mice or human immune system–engrafted NSG HLA-DQ8 mice (12) were injected intraperitoneally with NFAT5 inhibitor (3 mg/kg) once daily for 14 days (NOD mice) or 4 days (NSG mice). An miRNA181a antagomir (inhibitor probe mmu-miR-181a-5p, Exiqon) was injected intraperitoneally into IAA+NOD mice at 10 mg/kg every other day for 14 days. Control mice were injected with sodium chloride. On day 15 or 5, Treg frequencies were analyzed in the peripheral blood and pancreatic lymph nodes (NOD mice) or in the peripheral blood and spleen (NSG HLA-DQ8 mice). Pancreata of NOD mice were embedded for cryosections and analysis of pancreas pathology.

Histopathology of NOD pancreata

Pancreata were embedded with Tissue-Tek O.C.T. Compound and frozen on dry ice, and serial sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Insulitis scoring was performed as previously described (44, 45). The following scores were assigned: 0, intact islets/no lesions; 1, periislet infiltrates; 2, <25% islet destruction; 3, >25% islet destruction; 4, complete islet destruction. Investigators were blinded for group allocations.

Immunofluorsecence staining of NOD pancreata

Immunofluorescence staining was carried out using rabbit anti-mouse insulin antibodies (Cell Signaling) and donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 antibodies (Dianova). For CD4 staining, rat anti-mouse (Becton, Dickinson and Company) antibodies were used, followed by goat anti-rat Alexa Fluor 488 (Dianova). For NFAT5, staining a rabbit anti-mNFAT5 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used. For FoxP3 staining, cells were incubated with rat anti-mouse antibodies (eBioscience) and goat anti-rabbit (Becton, Dickinson and Company), combined with TSA Cyanine 3 amplification (PerkinElmer). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 dye (Invitrogen). Negative control slides were incubated with secondary antibodies. Cells were analyzed by confocal microscopy (Olympus).

Statistics

Results are presented as mean and SEM or as percentages, where appropriate, or as box and whisker plots with minimum to maximum values for data distribution. For normally distributed data, Student’s t test for unpaired values was used to compare means between independent groups, and the Student’s t test for paired values was used to compare values for the same sample or subject tested under different conditions. The nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied when data did not show Gaussian distribution. Group size estimations were based on a power calculation to minimally yield an 80% chance to detect a significant difference in the respective parameter of P < 0.05 between the relevant groups. For all tests, a two-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered to be significant. Statistical significance is shown as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, or not significant (ns) P > 0.05. Analyses were performed using the programs GraphPad Prism 6 and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 19.0, SPSS Inc.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Chmiel, M. Bunk, and S. Hummel for the blood sample collection and patient follow-up; C. Matzke for the support with the insulin autoantibody analyses; S. Fiedler for the support with immunohistochemistry; M. Serrano for providing the PTEN Tg mice; M. Pfaffl and the European Molecular Biology Laboratory GeneCore facility, especially V. Benes, for providing the analysis tools; and M.H. Tschöp for the critical review of the manuscript. Insulin-specific HLA-DQ8–restricted tetramer and monomer reagents were made available from the NIH Tetramer Core Facility under a material transfer agreement with this institution. H. Cho, H.-J. Lim, G. H. Lee, W. K. Park, H. Y. Kim, D. Y. Jeong, W.-U. Kim, C. S. Cho, S. J. Park, and E. J. Han are inventors of patent no. 9650389 held by Korea Research Institute of Chemical Technology, Catholic University of Korea Industry-Academic Cooperation Foundation that covers “8-oxoprotoberberine derivative or pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, preparation method therefor and pharmaceutical composition for preventing or treating diseases associated with activity of NFAT5, containing same as active ingredient”.

Funding: W.-U.K. received support from the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (no. 2015R1A3A2032927). B.W. is supported by WE 4656/2 and DFG-CRC1811 (B02). C.D. is supported by a Research Group at Helmholtz Zentrum München, by the German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD), and through a membership in the CRC1054 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (B11). K.H.K. is supported by an NIH grant (UC4DK112217). K.G. is supported by the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research Erlangen (project J50). A.M.Z. is supported by an NIH grant (K01DK102868). R.P. is supported by DFG-CRC1181 (Z02). This work was supported by grants from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation [JDRF 2-SRA-2014-161-Q-R (to C.D. and A.-G.Z.), JDRF 17-2012-16 (to A.-G.Z.), and JDRF 6-2012-20 (to A.-G.Z.)] and the Kompetenznetz Diabetes mellitus (Competence Network for Diabetes mellitus) and funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (FKZ 01GI0805-07 and FKZ 01GI0805) and the German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD).

Footnotes

www.sciencetranslationalmedicine.org/cgi/content/full/10/422/eaag1782/DC1

Materials and Methods

Fig. S1. Categories of human islet autoimmunity in children at risk of developing TD1.

Fig. S2. Identification of insulin-specific Tregs after Treg induction assays in vitro.

Fig. S3. Insulin-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation in accordance with the duration of islet autoimmunity.

Fig. S4. miR181a-targeted signaling pathways in CD4+ T cells.

Fig. S5. Nanoparticle-mediated miRNA uptake in CD4+ T cells.

Fig. S6. Nfat5 and Foxo1 expression upon TCR stimulation and increasing doses of costimulation.

Fig. S7. DNA methylation analysis of the human FOXP3 TSDR in in vitro–induced Tregs.

Fig. S8. NFAT5 and PTEN protein expression in CD4+ T cells of NOD mice.

Fig. S9. Hypertonicity-independent NFAT5 induction in CD4+ T cells of IAA+NOD mice.

Fig. S10. Pten and Foxo1 expression in CD4+ T cells from NFAT5ko mice.

Fig. S11. Treg frequencies after in vitro induction using CD4+ T cells from NFAT5ko animals.

Fig. S12. Nfat5 and Foxo1 expression in CD4+ T cells of PTEN Tg mice.

Fig. S13. Effect of an miRNA181a antagomir or mimic on Treg induction from PTEN Tg mice with decreasing anti-CD28 stimulation.

Fig. S14. Effect of NFAT5 inhibition in CD4+ T cells from humanized NSG mice or from PTEN Tg mice in vivo.

Fig. S15. Reduction of immune activation by blocking miRNA181a or NFAT5 in NOD mice.

Table S1. Primary source data.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions: I.S. performed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. M.G.S. performed the experiments. A.M.Z. supported the NGS and qPCR analyses. J.S. and M.H. supported the NGS analyses. V.K.F. performed the qPCR analyses. S.K. performed the in vitro analyses. M.B. performed the in vitro assays. P.A. supported the analyses of insulin autoantibodies. A.N. performed the immunofluorescence studies. K.G. performed the immunofluorescence experiments and analyzed the confocal microscopy images. N.L. produced and characterized the chitosan-coated PLGA nanoparticles. B.L. and C.-M.L. conceptualized the nanoparticle delivery. B.K. performed the data analyses from NGS analyses. M.S. and B.H. performed the sample processing for NGS analyses. J.S. provided the AKAP13 (Brx) heterozygous mice. C.K. provided the NFAT5ko mice. R.P. performed STED microcopy. A.W. supported the immunofluorescence studies. R.A.W. designed and produced the tetramer reagents. W.-U.K. provided the NFAT5 inhibitor. B.W. performed the immunofluorescent stainings. K.H.K. advised the miRNA analyses and luciferase experiments. A.-G.Z. co-conceptualized the study design and is the principal investigator of the BABYDIAB, DiMelli, and the Munich Bioresource studies, which provided blood samples for the study. C.D. conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the studies, and wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Bluestone JA, Herold K, Eisenbarth G. Genetics, pathogenesis and clinical interventions in type 1 diabetes. Nature. 2010;464:1293–1300. doi: 10.1038/nature08933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ziegler AG, Nepom GT. Prediction and pathogenesis in type 1 diabetes. Immunity. 2010;32:468–478. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziegler AG, Rewers M, Simell O, Simell T, Lempainen J, Steck A, Winkler C, Ilonen J, Veijola R, Knip M, Bonifacio E, Eisenbarth GS. Seroconversion tomultiple islet autoantibodies and risk of progression to diabetes in children. JAMA. 2013;309:2473–2479. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heninger AK, Eugster A, Kuehn D, Buettner F, Kuhn M, Lindner A, Dietz S, Jergens S, Wilhelm C, Beyerlein A, Ziegler AG, Bonifacio E. A divergent population of autoantigen-responsive CD4+ T cells in infants prior to β cell autoimmunity. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaaf8848. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf8848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khattri R, Cox T, Yasayko SA, Ramsdell F. An essential role for Scurfin in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:337–342. doi: 10.1038/ni909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roncador G, Brown PJ, Maestre L, Hue S, Martínez-Torrecuadrada JL, Ling KL, Pratap S, Toms C, Fox BC, Cerundolo V, Powrie F, Banham AH. Analysis of FOXP3 protein expression in human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells at the single-cell level. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1681–1691. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kretschmer K, Apostolou I, Hawiger D, Khazaie K, Nussenzweig MC, von Boehmer H. Inducing and expanding regulatory T cell populations by foreign antigen. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1219–1227. doi: 10.1038/ni1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daniel C, Wennhold K, Kim HJ, von Boehmer H. Enhancement of antigen-specific Treg vaccination in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:16246–16251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007422107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Boehmer H, Daniel C. Therapeutic opportunities for manipulating TReg cells in autoimmunity and cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:51–63. doi: 10.1038/nrd3683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniel C, Weigmann B, Bronson R, von Boehmer H. Prevention of type 1 diabetes in mice by tolerogenic vaccination with a strong agonist insulin mimetope. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1501–1510. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sauer S, Bruno L, Hertweck A, Finlay D, Leleu M, Spivakov M, Knight ZA, Cobb BS, Cantrell D, O’Connor E, Shokat KM, Fisher AG, Merkenschlager M. T cell receptor signaling controls Foxp3 expression via PI3K, Akt, and mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7797–7802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800928105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serr I, Fürst RW, Achenbach P, Scherm MG, Gökmen F, Haupt F, Sedlmeier EM, Knopff A, Shultz L, Willis RA, Ziegler AG, Daniel C. Type 1 diabetes vaccine candidates promote human Foxp3+Treg induction in humanized mice. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10991. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serr I, Fürst RW, Ott VB, Scherm MG, Nikolaev A, Gökmen F, Kälin S, Zillmer S, Bunk M, Weigmann B, Kunschke N, Loretz B, Lehr CM, Kirchner B, Haase B, Pfaffl M, Waisman A, Willis RA, Ziegler AG, Daniel C. miRNA92a targets KLF2 and the phosphatase PTEN signaling to promote human T follicular helper precursors in T1D islet autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E6659–E6668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606646113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cobb BS, Nesterova TB, Thompson E, Hertweck A, O’Connor E, Godwin J, Wilson CB, Brockdorff N, Fisher AG, Smale ST, Merkenschlager M. T cell lineage choice and differentiation in the absence of the RNase III enzyme Dicer. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1367–1373. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bukhari SIA, Truesdell SS, Lee S, Kollu S, Classon A, Boukhali M, Jain E, Mortensen RD, Yanagiya A, Sadreyev RI, Haas W, Vasudevan S. A specialized mechanism of translation mediated by FXR1a-associated MicroRNP in cellular quiescence. Mol Cell. 2016;61:760–773. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vasudevan S, Steitz JA. AU-rich-element-mediated upregulation of translation by FXR1 and argonaute 2. Cell. 2007;128:1105–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vasudevan S, Tong Y, Steitz JA. Switching from repression to activation: MicroRNAs can up-regulate translation. Science. 2007;318:1931–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1149460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuhofer W. Role of NFAT5 in inflammatory disorders associated with osmotic stress. Curr Genomics. 2010;11:584–590. doi: 10.2174/138920210793360961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniel C, Gerlach K, Väth M, Neurath MF, Weigmann B. Nuclear factor of activated T cells—A transcription factor family as critical regulator in lung and colon cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:1767–1775. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trama J, Lu Q, Hawley RG, Ho SN. The NFAT-related protein NFATL1 (TonEBP/NFAT5) is induced upon T cell activation in a calcineurin-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2000;165:4884–4894. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.4884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halterman JA, Kwon HM, Wamhoff BR. Tonicity-independent regulation of the osmosensitive transcription factor TonEBP (NFAT5) Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C1–C8. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00327.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trama J, Go WY, Ho SN. The osmoprotective function of the NFAT5 transcription factor in T cell development and activation. J Immunol. 2002;169:5477–5488. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irarrazabal CE, Burg MB, Ward SG, Ferraris JD. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mediates activation of ATM by high NaCl and by ionizing radiation: Role in osmoprotective transcriptional regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8882–8887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602911103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gottschalk RA, Corse E, Allison JP. TCR ligand density and affinity determine peripheral induction of Foxp3 in vivo. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1701–1711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li QJ, Chau J, Ebert PJR, Sylvester G, Min H, Liu G, Braich R, Manoharan M, Soutschek J, Skare P, Klein LO, Davis MM, Chen CZ. miR-181a is an intrinsic modulator of T cell sensitivity and selection. Cell. 2007;129:147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravi Kumar MNV, Bakowsky U, Lehr CM. Preparation and characterization of cationic PLGA nanospheres as DNA carriers. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1771–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nafee N, Taetz S, Schneider M, Schaefer UF, Lehr CM. Chitosan-coated PLGA nanoparticles for DNA/RNA delivery: Effect of the formulation parameters on complexation and transfection of antisense oligonucleotides. Nanomedicine. 2007;3:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taetz S, Nafee N, Beisner J, Piotrowska K, Baldes C, Mürdter TE, Huwer H, Schneider M, Schaefer UF, Klotz U, Lehr CM. The influence of chitosan content in cationic chitosan/PLGA nanoparticles on the delivery efficiency of antisense 2′-O-methyl-RNA directed against telomerase in lung cancer cells. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2009;72:358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polansky JK, Kretschmer K, Freyer J, Floess S, Garbe A, Baron U, Olek S, Hamann A, von Boehmer H, Huehn J. DNA methylation controls Foxp3 gene expression. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1654–1663. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alleva DG, Crowe PD, Jin L, Kwok WW, Ling N, Gottschalk M, Conlon PJ, Gottlieb PA, Putnam AL, Gaur A. A disease-associated cellular immune response in type 1 diabetics to an immunodominant epitope of insulin. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:173–180. doi: 10.1172/JCI8525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daniel D, Gill RG, Schloot N, Wegmann D. Epitope specificity cytokine production profile and diabetogenic activity of insulin-specific T cell clones isolated from NOD mice. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1056–1062. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wegmann DR, Norbury-Glaser M, Daniel D. Insulin-specific T cells are a predominant component of islet infiltrates in pre-diabetic NOD mice. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1853–1857. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kino T, Takatori H, Manoli I, Wang Y, Tiulpakov A, Blackman MR, Su YA, Chrousos GP, DeCherney AH, Segars JH. Brx mediates the response of lymphocytes to osmotic stress through the activation of NFAT5. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra5. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Küper C, Beck F-X, Neuhofer W. Generation of a conditional knockout allele for the NFAT5 gene in mice. Front Physiol. 2014;5:507. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ortega-Molina A, Efeyan A, Lopez-Guadamillas E, Muñoz-Martin M, Gómez-López G, Cañamero M, Mulero F, Pastor J, Martinez S, Romanos E, Mar Gonzalez-Barroso M, Rial E, Valverde AM, Bischoff JR, Serrano M. Pten positively regulates brown adipose function, energy expenditure and longevity. Cell Metab. 2012;15:382–394. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han E-J, Kim HY, Lee N, Kim N-H, Yoo S-A, Kwon HM, Jue D-M, Park Y-J, Cho C-S, De TQ, Jeong DY, Lim H-J, Park WK, Lee GH, Cho H, Kim W-U. Suppression of NFAT5-mediated inflammation and chronic arthritis by novel κB-binding inhibitors. EBioMedicine. 2017;18:261–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Achenbach P, Hummel M, Thümer L, Boerschmann H, Höfelmann D, Ziegler AG. Characteristics of rapid vs slow progression to type 1 diabetes in multiple islet autoantibody-positive children. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1615–1622. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2896-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilczynska A, Bushell M. The complexity of miRNA-mediated repression. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:22–33. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ouyang W, Beckett O, Ma Q, Paik J-h, DePinho RA, Li MO. Foxo proteins cooperatively control the differentiation of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:618–627. doi: 10.1038/ni.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ziegler AG, Hummel M, Schenker M, Bonifacio E. Autoantibody appearance and risk for development of childhood diabetes in offspring of parents with type 1 diabetes: The 2-year analysis of the German BABYDIAB Study. Diabetes. 1999;48:460–468. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.3.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ziegler A-G, Bonifacio E BABYDIAB-BABYDIET Study Group. Age-related islet autoantibody incidence in offspring of patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2012;55:1937–1943. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2472-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Achenbach P, Lampasona V, Landherr U, Koczwara K, Krause S, Grallert H, Winkler C, Pfluger M, Illig T, Bonifacio E, Ziegler AG. Autoantibodies to zinc transporter 8 and SLC30A8 genotype stratify type 1 diabetes risk. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1881–1888. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1438-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Babaya N, Liu E, Miao D, Li M, Yu L, Eisenbarth G. Murine high specificity/sensitivity competitive europium insulin autoantibody assay. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2009;11:227–233. doi: 10.1089/dia.2008.0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krishnamurthy B, Dudek NL, McKenzie MD, Purcell AW, Brooks AG, Gellert S, Colman PG, Harrison LC, Lew AM, Thomas HE, Kay TWH. Responses against islet antigens in NOD mice are prevented by tolerance to proinsulin but not IGRP. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3258–3265. doi: 10.1172/JCI29602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crawford F, Stadinski B, Jin N, Michels A, Nakayama M, Pratt P, Marrack P, Eisenbarth G, Kappler JW. Specificity and detection of insulin-reactive CD4+ T cells in type 1 diabetes in the nonobese diabetic (NOD) mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16729–16734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113954108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee KH, Wucherpfennig KW, Wiley DC. Structure of a human insulin peptide–HLA-DQ8 complex and susceptibility to type 1 diabetes. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:501–507. doi: 10.1038/88694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maus MV, Riley JL, Kwok WW, Nepom GT, June CH. HLA tetramer-based artificial antigen-presenting cells for stimulation of CD4+ T cells. Clin Immunol. 2003;106:16–22. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(02)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kong Y. Btrim: A fast lightweight adapter and quality trimming program for next-generation sequencing technologies. Genomics. 2011;98:152–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: Annotating high confidence microRNAs using deep sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D68–D73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weiss B, Schaefer UF, Zapp J, Lamprecht A, Stallmach A, Lehr CM. Nanoparticles made of fluorescence-labelled Poly(L-lactide-co-glycolide): Preparation, stability, and biocompatibility. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2006;6:3048–3056. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2006.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baron U, Floess S, Wieczorek G, Baumann K, Grützkau A, Dong J, Thiel A, Boeld TJ, Hoffmann P, Edinger M, Türbachova I, Hamann A, Olek S, Huehn J. DNA demethylation in the human FOXP3 locus discriminates regulatory T cells from activated FOXP3+ conventional T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2378–2389. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Floess S, Freyer J, Siewert C, Baron U, Olek S, Polansky J, Schlawe K, Chang HD, Bopp T, Schmitt E, Klein-Hessling S, Serfling E, Hamann A, Huehn J. Epigenetic control of the foxp3 locus in regulatory T cells. PLOS Biol. 2007;5:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.