Abstract

Shiftwork became common during the last few decades with the growing demands of human life. Despite the social inactivity and irregularity in habits, working in continuous irregular shifts causes serious health issues including sleep disorders, psychiatric disorders, cancer, and metabolic disorders. These health problems arise due to the disruption in circadian clock system, which is associated with alterations in genetic expressions. Alteration in clock controlling genes further affects genes linked with disorders including major depression disorder, bipolar disorder, phase delay and phase advance sleep syndromes, breast cancer, and colon cancer. A diverse research work is needed focusing on broad spectrum changes caused by jet lag in brain and neuronal system. This review is an attempt to motivate the researchers to conduct advanced studies in this area to identify the risk factors and mechanisms. Its goal is extended to make the shift workers aware about the risks associated with shiftwork.

1. Introduction

Fast growing needs demand doing work in recurring periods other than the traditional diurnal periods. The rotations in working shifts disrupt natural sleep-wake cycle and eating patterns [1], which in turn cause serious health problems by affecting mental health and work effectiveness [2]. This disruption alters circadian rhythms [3] and neuronal functions to cause neuronal disorders [2]. Shiftwork for a long period increases the risk of fatigue, aggression, sleep disorders, metabolic disorders, mental abnormalities, and death [2, 4–9]. Shiftwork directly affects alertness [10, 11], causes depression, and promotes anxiety [12].

Working repeatedly during night shifts affects hormonal system and disrupts hormonal secretions and their control factors [13–16]. This altered hormonal profile increases the risk of breast cancer, prostate cancer, gastrointestinal abnormalities, cardiovascular diseases, and reproductive aberrations [17–19]. Alterations in physiological, behavioral, and psychological mechanisms [5] further develop abnormalities associated with peptic ulcer, diabetes type II, and rheumatoid arthritis [20–22]. The measurement of shiftwork is considered complex as it requires several parameters including sleep quality, fatigue level, types of sleep problems, use of stimulants, and sleepiness [2, 23].

Shiftwork has gained huge importance which is inevitable in modern world. This situation alerts researchers to focus on shiftwork and related abnormalities. Without knowing the genetic mechanisms and identifying factors related to shiftwork-promoted health problems, development of prevention and curing strategies may not be achievable. Suitable model organism, monitoring systems, and mimicking the shiftwork in lab conditions are major challenges in studying shiftwork to investigate related disorders. These challenges make the identification genes, majorly involved in shiftwork-related abnormalities, difficult. In this review, we have focused on major health problems that are linked with shiftwork directly or indirectly.

2. Shiftwork Dysregulates Circadian Rhythms by Affecting Clock Genes

Circadian rhythm mainly controls the daily wake and sleep cycle and regulates physiological processes including hormone secretion, body temperature, feeding behavior, cell cycle progression, and drug, glucose, and xenobiotic metabolism. Its disruption through environmental and genetic means causes aberrations in physiological processes. Clock genes with the effects of oscillators and endocrine and neural signals regulate circadian rhythm [24] which may be disrupted apparently by shiftwork. Circadian clock, through appropriate physiological activities in relevance to time, controls the circadian rhythms [4]. Shiftwork (chronic jet lag) suppresses the expression levels of core clock genes, including Per1 and Per2 in suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) and MT1 melatonin and glucocorticoid receptors in the liver. It further causes delay in acrophases of circadian expression of Per1, Per2, BMAL1, and Dbp in liver. Besides clock genes, expression levels of some cell cycle-related genes including c-Myc and p53 are also altered [25]. Vasopressin (V1a and V1b) receptors (expressed in SCN neurons) promote shiftwork effect in combination with core clock genes. Individuals lacking these receptors are normally resistant to jet lag/shiftwork effects [26].

Circadian oscillator period is determined around 24 hours genetically and adjusted by synchronizers such as LD cycle. Circadian rhythms synchronized to day time work and night time sleep require phase adjustment in altered routines by central and peripheral oscillators. This phase adjustment in certain cases disrupts the normal organization and sequence of the clock. Clock genes behave differently during phase shifts [1, 27]. Shift workers undergo circadian dysrhythmia that adversely effects mental health. This further leads to circadian rhythm disorder causing aberrations in neurogenesis and spatial cognition [28].

Many aspects of circadian rhythmicity can be modulated by serotonergic agents that indicate that serotonin is involved in the regulation of circadian rhythm. Serotonin transporter (5-HTT) control serotonin reuptake depending on serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) promoter region (5-HTTLPR) [29]. Significant associations between shiftwork and S variant of the SLC6A4 promoter and 5-HT and 5-HIAA contents of platelet can help in investigating the circadian rhythm-related mechanisms imposed by shiftwork [29]. The effect of shiftwork on circadian rhythm and sleep may cause the metabolic dysregulation and depressions by affecting the genetic pathways. The affect may lead to the disruption of other functioning systems and cause relative disorders either through direct or indirect genetic interaction in continuous/discontinuous forms.

3. Shiftwork Disrupts Normal Sleep and Behavior

Sleep consists of two repeated cyclic patterns “nonrapid eye movement and rapid eye movement” [30]. It is controlled genetically with the influence of environmental factors [31, 32]. Adenosine, a sleep-promoting molecule [33], mediates wake-promoting effects of caffeine by acting on adenosine receptors antagonistically [34]. GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) promotes sleep whereas dopamine, acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and histamine promote wakefulness [35]. The cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) kinase [36, 37], regulatory subunit of Shaker [38], Sleepless (sss) gene [39], and CLK and CYC proteins [40] are key players in sleep regulation. All these genes and regulators may get disrupted in shift workers which will lead to abnormal sleep and other serious health conditions.

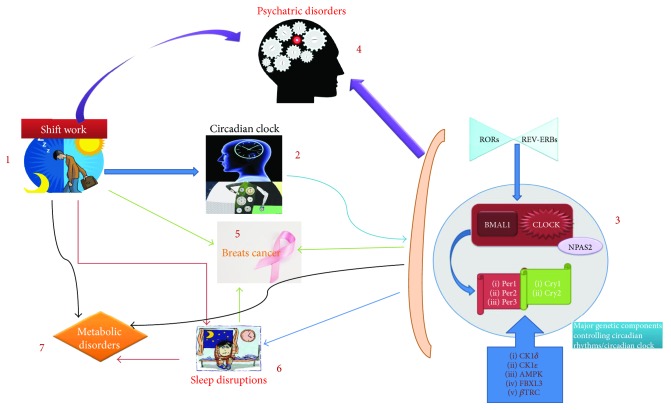

Shiftwork due to the rotation of working schedules and light/dark disturbance directly affects sleep (as shown in Figure 1) and may cause health abnormalities including insomnia, sleep apnea, periodic leg movements, restless leg syndrome (RLS), and sleep-wake state dissociation disorders such as rapid eye movement (REM) and narcolepsy, sleep behavior disorder, and sleep walking [34]. Furthermore, the shiftwork-induced deficits in sleep homeostasis and circadian rhythms may lead to different psychiatric disorders and affect SUR2 gene, which was found involved in energy metabolism and aetiology of cardiomyopathies [41]. Shiftwork may disrupt daily patterns of human physiology controlled by circadian rhythms and sleep, including regulation of energy patterns expenditure [42, 43] and glucose metabolism [42].

Figure 1.

The abnormalities associated with shiftwork. (1) Shiftwork primarily affects the circadian clock and leads to several disruptions and disorders. (2) Disruption in circadian clock further affects the circadian system and alters important gene expressions which play an important role in maintaining normal body functions. (3) BMAL1 and CLOCK genes are the key factors that control circadian rhythms. Any alteration in these groups of genes further alters the genetic expression of genes (Per 1–3 and Cry 1/2) involved in clock maintenance. Other factors and proteins which play a major role in circadian rhythm are RORs, REV-ERBs, CK1δ, CK1ε, AMPK, FBXL3 and βTRC. (4) Shiftwork either directly or through circadian system alterations may cause severe psychiatric disorders including major depression, anxiety, and mood disorders. (5) Due to exposure to light irregularly, shiftwork enhances the chances of breast cancer. Breast cancer development is promoted by sleep disruptions, circadian system imbalances, and dietary conditions. (6) Sleep disorders and disrupted sleep is another condition developed by shiftwork. (7) This disruption in sleep affects the metabolism and causes metabolic disorders including obesity.

Shiftwork may negatively affect genes and factors involved in sleep disorders such that a SNP marker [44] and chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 3 (CCR3) susceptibility gene [45] associated with narcolepsy, MEIS1 locus, and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS1) and BTBD9 associated with RLS [46–48]. Serine to glycine mutation in PER2 and mutation in casein kinase Iδ gene (CSNK1D) develop familial advanced sleep phase syndrome (FASPS) [34, 35] whereas point mutation in PRNP causes fatal familial insomnia (FFI) [35]. The disrupted functions of the above genes through shiftwork may lead to related disorders. Shiftwork can alter the functionality of sleep-promoting immune genes [49], glucocorticoids and NSAIDs [50], protein NF-kB (upregulated during sleep deprivation) [34], TAK1 (TGF-b-activated kinase) and Sik3 (control sleep behaviors), and Nalcn gene (involved in REMS) [51]. Widening its effectiveness, shiftwork promotes acute coronary syndrome [52], menstrual disturbances, and abnormal insulin levels [53] and increases sleepiness and alcohol consumption [54]. It also lifts sleep deprivation that ultimately leads to loss in cognitive, physical, and metabolic consequences. These alterations can possibly end up with developing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [29].

4. Shiftwork Dysregulates Metabolic Process and Develops Related Disorders

Social jet lag is a key player in developing metabolic syndrome by inducing changes in cholesterol levels and disrupting normal food processes. It was observed in an experiment that social jet lag potentiated body weight gain by increasing overconsumption of cafeteria food. As a result, it promoted high insulin and dyslipidemia indicating the risk of metabolic syndrome [55]. A chronic shift in light/dark (LD) cycles induces obesity, increases body weight and glucose intolerance, and accumulates more fat in white adipose tissues. It changes the expression profiles of metabolic genes in liver [56].

According to timed sleep restriction (TSR) study, sleep timing directly affects clock-controlled genes including ClockD19, BMAL1, Per1, Rev-erbα and Dbp, and circadian machinery. This alteration affects metabolic processes including carbohydrate and lipid utilization in liver. BMAL1, Per1, and Dbp were upregulated during early light phase and Rev-erbα during mid-light phase. Carbohydrate regulators affected were insulin receptor substrate 2 (Irs2), glucose-responsive fork head box O1 (Foxo1), and glucose transporter 2 (Slc2a2). These regulators control the functions of pyruvate carboxylase, the pyruvate transporter Slc16a7, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4, the glycerol transporter aquaporin, fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 1, and liver pyruvate kinase. These alterations in carbohydrate regulators further affect glycerol kinase and glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase 2, glutamic-pyruvate transaminase, and regulators of glycerol biosynthesis [4]. This dysregulation may induce critical alterations in genetic system to develop metabolic disorders.

The presence of metabolic process controlling genes in rhythmic transcriptome indicates that alteration in circadian rhythm causes disruption in metabolic process [4, 57–59]. CLOCK, BMAL, and PER2 were found associated with obesity by affecting the metabolic process [60, 61]. Shiftwork brings about changes in appetitive hormones through circadian misalignment which causes reduction in leptin level that ultimately leads to weight gain. Shift workers are considered at higher risk of type II diabetes [42, 62].

5. Shiftwork-Related Health Risks

5.1. Shiftwork Is Associated with Mortality

Quick return occurs due to rotations in between shifts, causing major accidents [22] that normally lead to death. Shiftwork increases the risk of several disorders including mental disorders and sleep-related disorders, which may lead to death. In an experiment related to jet lag effects on transgenic aged rats, it was found that mortality light scheduled rotations at 6 hours phase advance, each week. The survival rate of rats exposed to shifted light schedule was found lesser (47%) than the survival rate (83%) of rats exposed to normal light (12L/12D) scheduled rotations. Although jet lag has no mortal effect on younger mice, it alters the behavior and circadian rhythms which further causes serious health issues by affecting brain and liver [7].

5.2. Shiftwork Induces Mental and Related Disorders

The role of SLC6A4 (serotonin transporter gene) in shift workers was confirmed to be related with time period. The proportion of short allele becomes higher than large allele if the period is more than 5 years. The effectiveness of shiftwork becomes higher in case of internal desynchronization of circadian rhythm [2, 63].

Endocrine imbalance in depression and psychosis is the hyperactivity of the HPA axis [64]. Glucocorticoid functions as an immunosuppressant and interacts with melatonin in a form of suppressive effect on the production of ACTH-induced glucocorticoid [65]. Its resistance results in hypercortisolemia in psychiatric patients and increased pituitary volume in depressed patients [66, 67]. Shiftwork causes desynchronization in circadian rhythm which in turn leads to reduced NK activity and weakening cellular immunity [68], disruptions in norepinephrine, melatonin, and serotonin production [69, 70] which may induce anxiety, depression, hypercortisolemia, and psychosis.

5.3. Shiftwork Disorder and Associated Factors

Shiftwork disorder is characterized by insomnia and excessive sleepiness which develops due to working schedules overlapping sleeping time [71]. According to a study, shiftwork disorder was found to occur frequently in males as compared to females, working during the night. Approximately, 9% of the night shift workers reported severe shiftwork disorder while one-third of the total had mild symptoms [71]. Shiftwork sleep disorder changes the behavior and sleeping periods permanently which could possibly be recovered through advanced therapies only. Treatment with modafinil, an effective compound against narcolepsy and obstructive sleep apnea, was found ineffective [6], suggesting that the mechanisms involved in shiftwork sleep disorder are not related to sleep apnea and narcolepsy. Molecular level studies with a broad range of patients, to investigate mechanisms, are needed to find out the main alterations in the system to prevent and cure the conditions properly.

The high number of nights and age were found associated with shiftwork disorder [22], whereas genotypes were found to be associated with morningness and eveningness. Allele 3111C is associated with extreme eveningness and shiftwork with semidominant influence on sleep phases without having an obvious influence on morning/evening preferences. 3111C/C homozygotes are associated with delayed shift of sleep [72] where melatonin can phase-shift the circadian clock being chronobiotic and a sleep promoting agent [73].

5.4. Shiftwork Sleep Disorder

Shiftwork sleep disorder is a condition defined by excessive sleepiness or insomnia accompanied by total sleep time reduction. It is 10–38% prevalent in shift workers [5, 43]. The disturbance in general is the sleep-wake cycle distortion of extrinsic origin. This disorder is related to the night and early morning timings. Reduction in alertness and performance along with the linkage to higher rates of comorbidity with GI disorders [67] make SWSD a severe and attention-requiring condition. Sleepiness during the night and insomnia during the day become more severe with continuous shiftwork for longer periods. Depression, ulcers, and sleepiness-related accidents are the ultimate risks associated with shiftwork sleep disorder. This sleepiness behavior during night is similar to the day time sleepiness in people with narcolepsy [6].

5.5. Advanced and Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome

Advanced sleep phase syndrome (ASPS) is characterized by 3-4 hours advanced awakening times and sleep onsets relative to normal times. It is inherited in autosomal dominant mode, caused by circadian cycle irregularity as circadian clock genes are key players in its development. Missense mutations S662G (occurs in phosphorylation site within CSNK1-binding domain of PER2) and CSNK1D are involved in ASPS [58].

Delayed sleep phase syndrome (DSPS) is characterized by chronic inability to fall asleep and awaken at normal timings [58]. Circadian system genes are majorly involved in this dysregulated sleep behavior. Significant associations with T3111C polymorphism in the 3′UTR of CLOCK and the association of a SNP in the 5′UTR of PER2 with morning preference have been reported in DSPS [72, 74]. According to a study, amino-acid substitution S408N in the CSKN1E gene might protect the body form DSPS and non-24-hour sleep-wake syndrome development [58]. Both the shorter and longer VNTR (variable number tandem repeat) alleles were found (PER3-4/4) associated with DSPS [75]. Per3 gene is involved in delayed sleep phase syndrome and extreme diurnal preference.

Mutation in hPER2 has a notable association with advanced sleep phase syndrome, whereas some haplotypes of hPER3 have shown an association with delayed sleep phase syndrome. These conditions arise because of the alterations into casein kinase Iε (CKIε) phosphorylation of the target clock proteins, affecting morningness and eveningness. Polymorphisms in 3′ flanking region of the human clock homolog (3111T/C, hClock) is associated with eveningness and morningness such that 3111T allele has lower evening preference than 3111C allele [72]. As shiftwork has direct impacts on sleep, it may affect the normal functioning of genes to cause one of the two sleep abnormalities ASPS and DSPS.

5.6. Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorder

Circadian rhythm sleep disorder refers to the abnormalities brought about by circadian misalignment due to variations in sleep-wake pattern. The shift in sleep-wake time is commonly caused by shiftwork, jet lag, light exposure, and insufficient sleep period. Circadian misalignment alters neuroendocrine physiology, impairs glucose tolerance, and reduces insulin sensitivity [42, 62, 76, 77]. Sleep deprivation problem rises with the incompatibility between circadian rhythms and working periods [78]. Both circadian alterations and sleep deprivations lead to fatigue, impairments in vigilance and attention, sleepiness [79], sleep deficiency, impaired physiological function, and aberrant behavior [76, 80–82]. A subset of insomnias including non-24-hour sleep-wake syndrome is also linked with circadian rhythm sleep disorder [81]. Exposure to bright light in shiftwork and working in consecutive shifts if maintained for longer time may change the system at the genetic level. This alteration will further disrupt the normal functions of gene-related behavior, sleep, and circadian system. Such modifications will ultimately lead to health-harming conditions.

6. Shiftwork-Related Alterations in Nervous System to Develop Psychiatric Disorders

Adversely affected nervous system by working in continuously rotating shifts may accelerate the rate of psychiatric disorder occurrence (Figure 1). Being major causes of disabilities [83], psychiatric disorders including bipolar disorder (BD), schizophrenia (SZ), and major depression disorder (MDD) impose enormous medical burdens [84–86]. The genetic alteration and uncontrolled expression of genes primarily causing the aforementioned disorders [83, 87–89] are associated with irregular continuous changing of shifts during work. Night shift work contributed toward several psychiatric disorders through circadian misalignment, sleep deprivation, and light-induced melatonin suppression [73]. Disrupted-in-schizophrenia-1 (DISC1) is an important genetic factor in serious mental disorders including SZ, BD, and MDD [90]. We will further discuss the previously mentioned psychiatric disorders one by one to provide detailed information.

6.1. Bipolar Disorder

BD is considered one of the severely disabling disorders. Distinctive distortions of emotion regulation make BD a severe psychiatric condition. It mainly affects emotional and social behavior with light effect on perception and thought. Being a multifactorial disorder, its risk is influenced by genetic and environmental factors [91]. Genetic and pathophysiological factors involved in the development of BD are largely unknown [92]. BD increases the risk of schizophrenia and major depression disorder which is an indication for shared genetic basis between these disorders. Although heritability has been proven, more studies are needed to investigate the genetic mechanisms [93, 94]. In BD, important genetic variants that could be affected by shiftwork either directly or indirectly are Del, ANK3 rs1938526, COMT Val158Met, DAOA, BRD1/ZBED4, BDNF Val66Met, BRD1, ASMT, CAMTA1, CCDC132, CHES1, DGKH, DRD4, HTR1A C1019G, SLC6A4, 5-HTTLPR PARD3B, PDLIM5, STin2 VNTR, KLHL3, LYPD5, MAOA T941G, MTHFR A1298C and C677T, TPH1 STAB1, HTR3B, and WNK2 [95]. They are expressed in brain and associated with CREB (cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein). KCNH7 R394H (rs78247304) mutation is linked to BD. ANK3, CACNA1C, an intron variant of CACNA1C (rs79398153), and a missense mutation of ANK3 (N2643S) were confirmed being involved in BD [95, 96]. All these mutations are possibly enhanced in people working in several shifts or exposing to irregular light (jet lag).

6.2. Major Depression Disorder

MDD, a leading cause of loss in work productivity, is considered a fatal disorder. It is considered one of the most prevalent disorders that affect females more than males [97, 98]. Genetic and environmental risk factors mainly contribute to cause MDD. It is a neuroprogressive disorder in which each persisting episode increases impairment in function and sensitivity for upcoming episodes. A decrease in the GR messenger ribonucleic acid levels in hippocampus, frontal cortex, and amygdala has been observed in the patients suffering from MDD. Susceptibility to further episodes is increased by repeated illness which causes the permanent alteration in the normal functions of neurons [99] and genes [100] including MTHFR C677T and 5-HTTLPR [101]. Some of the important genetic variants associated with MDD that could be affected by shiftwork are APOE, SLC6A4, ACE, GNB3, HS6ST3, HTR1A, LHFPL2, PDE11A, DISC1, MAOA, SLC6A3 (DAT1), SLC25A21, VGLL4 BDNF, P2RX7, TPH2, PDE9A, and GRIK3 [95, 100]. Neutral amino acid transporter (SLC6A15) is a susceptibility gene for MDD [102].

7. Shiftwork Affects Expressions of Oncogenes to Develop Cancer

Malignancies are majorly developed by mitigation in pineal hormone melatonin by bright light at night [1]. Reduced production of melatonin, phase shift, and sleep disruption, caused by exposure to light at night, might be the possible mechanisms that cause cancer and related disorders [103]. Shiftwork causes cancer (Figure 1) via altering the clock-controlled gene expression that regulate tumor suppression [1, 104]. Per1 negatively affects the growth of tumor cell and per2 functions as tumor repressor [105]. Long-term shiftwork negatively affects IFNγ (interferon gamma) [106] The association of shiftwork-affected immune system with sleep deprivation increases inflammatory markers thereby causing malignancies and metabolic and cardiovascular disorders [1]. Circadian rhythm disruption by shiftwork or bright light exposure at night increases the rate of cancer and decreases the nocturnal rise in melatonin [19].

7.1. Breast Cancer

The disrupted circadian rhythm or circadian clock through shiftwork effects the development of breast cancer (Figure 2) [107]. Cell proliferation and apoptosis is regulated by approximately 7% of clock-controlled genes, including myelocytomatosis viral oncogene human recombinant (C-Myc), murine double minute oncogene (Mdm-2), and growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible alpha protein (Gadd 45a) and those encoding p53, caspases, and cyclins. Per1 is reduced in cancer tissue and its inhibition blunts apoptosis, whereas Per2 represses tumor in breast cancer and induces estradiol (E2) in mammary cells. Coexpression of Per2 with cytochrome inhibits growth of breast cancer cells. Deficiency of Per2 causes deregulation of Myc, cyclin A, cyclin D1, Mdm-2, and Gadd45a, while its dysfunctionality impairs apoptosis mediated by p53 by activating c-Myc signaling pathway. Overexpressing and downregulating Per1 or Per2 inhibits and accelerates growth of cancer cells, respectively [1]. Telomere shortening is correlated with consecutive night shift work for a long time where it increases breast cancer risk [108].

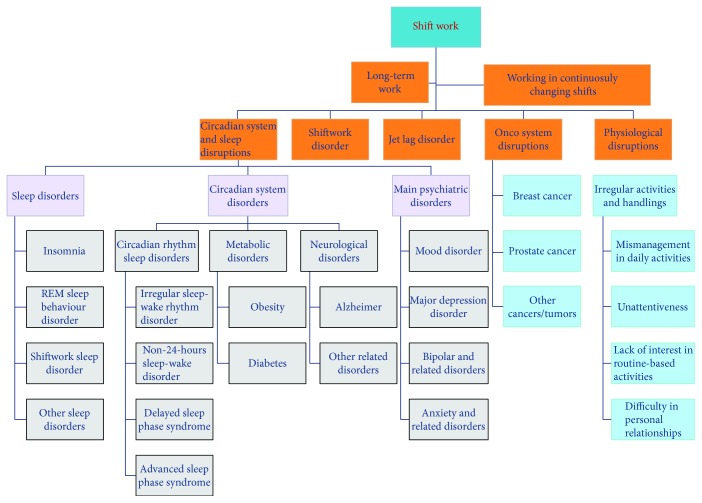

Figure 2.

All disorders that could possibly be caused by shiftwork.

7.2. Colonic Cancer

Per1- and Per2-mediated tumor-repressing effect is more specific to early light and early dark phase. Per2 mutations and deregulation favor development and increases cell proliferation, respectively [1]. Altered light schedules develop mutations in PER1, PER2, and PER3 which in turn promote colonic adenoma and colonic cancer [19, 109].

7.3. Prostate Cancer

Shiftwork-mediated sleep disruption is associated with elevated prostate-specific antigen (PSA), indicating an increased risk of developing prostate cancer [110]. Disrupted circadian rhythms through jet lag inhibits p53, enhances Myc expression, and induces tumorigenesis in prostate tissues targeted by endocrine [1, 111, 112].

7.4. Ovarian Cancer

Functional analysis suggested that variation, in circadian genes including BMAL1, CRY2, CSNK1E, NPAS2, PER3, REV1, and downstream transcription factors KLF10 and SENP3 through disruption of hormonal pathways or changes in light/dark schedules, is associated with ovarian cancer. Silencing the expression of BMAL1 activates p53 to prevent cell cycle arrest which indicates that BMAL1 gene may regulate the p53 tumor suppressor pathway. Per2 inhibition, reduces estrogen receptor α (ERα) response to E2 by overexpression or enhances E2 activation [112, 113]. Its lower expression along with lower expression of BMAL1 and CRY1 promotes lower survival of cells in ovarian cancer [114].

7.5. Lung Cancer

Not only systemic but also somatic disruption of circadian rhythms mediated by jet lag alone affects c-Myc and enhances cell proliferation. Per2 and BMAL1 lose the ability of inhibiting tumor progression and hence promotes lung cancer [115].

7.6. Shiftwork Tolerance

The effects of shiftwork regarding tolerance and responsiveness are concerned with certain factors. The youngest and oldest individuals are affected more than individuals with middle age [116]. Females due to low tolerance develop more problems, like sleep disruptions, higher risk of mortality, disability, fatigue, and obesity, while males show more cognitive disturbances [117, 118]. In case of circadian rhythms, a low score on morningness [119] and languidness and a high score on flexibility [120] are associated positively with shiftwork tolerance.

8. Conclusion and Prospects

Shiftwork has gained central importance due to its detrimental effects on health. A large population of the world, including regular travelers, night shift workers, continuously faces jet lag conditions. Working in frequently rotating shifts causes several medical issues to arise, including cancer, psychiatric disorders, quick return accidents, and metabolic disorders. These conditions lasting longer may bring irreversible changes in the body, leaving no choice for affective recovery. It is impossible to avoid working in rotating shifts or prevent oneself from light exposure.

The health problems related to shiftwork are developed by disruptions in genetic expressions. To prevent or mitigate the adverse effects of shiftwork-related disorders, unveiling of genetic mechanisms and determination of related pathways are needed.

These relations and interactions could be studied in a better way through jet lag, circadian rhythms, and sleep behaviors.

The effects of shiftwork may involve a series of genes and factors majorly involved in circadian rhythm, sleep homeostasis, and the specific disorder prevention. It is considered that circadian genes have noticeable impacts on cancer controlling genes, psychiatric disorder causing genes, and metabolic disorder-related genes. But it is still needed to be investigated whether shiftwork directly affects the genes related to certain disorders or it elongates its impact via targeting other genes such as clock genes. The proper targeted medications are possible to be developed only if the mechanisms and factors causing and promoting the shiftwork effects to cause disorders have been identified.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 31372381) and the Henan Scientific and Technological Innovation Team Fund (17454). The authors are thankful to the Chinese Academy of Science and The World Academy of Science (CAS-TWAS) scholarship program.

Contributor Information

Lunguang Yao, Email: lunguangyao@163.com.

Hongwei Hou, Email: houhw@ihb.ac.cn.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Haus E. L., Smolensky M. H. Shift work and cancer risk: potential mechanistic roles of circadian disruption, light at night, and sleep deprivation. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2013;17(4):273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saksvik I. B., Bjorvatn B., Hetland H., Sandal G. M., Pallesen S. Individual differences in tolerance to shift work – a systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2011;15(4):221–235. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salgado-Delgado R., Angeles-Castellanos M., Saderi N., Buijs R. M., Escobar C. Food intake during the normal activity phase prevents obesity and circadian desynchrony in a rat model of night work. Endocrinology. 2010;151(3):1019–1029. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barclay J. L., Husse J., Bode B., et al. Circadian desynchrony promotes metabolic disruption in a mouse model of shiftwork. PLoS One. 2012;7(5, article e37150) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flo E., Pallesen S., Magerøy N., et al. Shift work disorder in nurses – assessment, prevalence and related health problems. PLoS One. 2012;7(4, article e33981) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czeisler C. A., Walsh J. K., Roth T., et al. Modafinil for excessive sleepiness associated with shift-work sleep disorder. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(5):476–486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson A. J., Sellix M. T., Daniel J., Yamazaki S., Menaker M., Block G. D. Chronic jet-lag increases mortality in aged mice. Current Biology. 2006;16(21):R914–R916. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubo T., Ozasa K., Mikami K., et al. Prospective cohort study of the risk of prostate cancer among rotating-shift workers: findings from the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;164(6):549–555. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens R. G., Hansen J., Costa G., et al. Considerations of circadian impact for defining ‘shift work’ in cancer studies: IARC Working Group Report. Occupational & Environmental Medicine. 2010;68(2):154–162. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.053512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sallinen M., Kecklund G. Shift work, sleep, and sleepiness - differences between shift schedules and systems. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 2010;36(2):121–133. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bara A.-C., Arber S. Working shifts and mental health – findings from the British household panel survey (1995–2005) Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 2009;35(5):361–367. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Härmä M., Kecklund G. Shift work and health – how to proceed? Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 2010;36(2):81–84. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rehman J.-U., Brismar K., Holmback U., Akerstedt T., Axelsson J. Sleeping during the day: effects on the 24-h patterns of IGF-binding protein 1, insulin, glucose, cortisol, and growth hormone. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2010;163(3):383–390. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arendt J. Shift work: coping with the biological clock. Occupational Medicine. 2010;60(1):10–20. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqp162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crispim C. A., Waterhouse J., Dâmaso A. R., et al. Hormonal appetite control is altered by shift work: a preliminary study. Metabolism. 2011;60(12):1726–1735. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Cauter E., Knutson K. L. Sleep and the epidemic of obesity in children and adults. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2008;159(Supplement 1):S59–S66. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marino J. L., Holt V. L., Chen C., Davis S. Shift work, hCLOCK T3111C polymorphism, and endometriosis risk. Epidemiology. 2008;19(3):477–484. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816b7378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suwazono Y., Dochi M., Sakata K., et al. A longitudinal study on the effect of shift work on weight gain in male Japanese workers. Obesity. 2008;16(8):1887–1893. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis S., Mirick D. K. Circadian disruption, shift work and the risk of cancer: a summary of the evidence and studies in Seattle. Cancer Causes & Control. 2006;17(4):539–545. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-9010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knutsson A., Bøggild H. Gastrointestinal disorders among shift workers. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 2010;36(2):85–95. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puttonen S., Oksanen T., Vahtera J., et al. Is shift work a risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis? The Finnish Public Sector study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2010;69(4):679–680. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.099184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eldevik M. F., Flo E., Moen B. E., Pallesen S., Bjorvatn B. Insomnia, excessive sleepiness, excessive fatigue, anxiety, depression and shift work disorder in nurses having less than 11 hours in-between shifts. PLoS One. 2013;8(8, article e70882) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamagawa R., Lobb B., Booth R. Tolerance of shift work. Applied Ergonomics. 2007;38(5):635–642. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albrecht U. Timing to perfection: the biology of central and peripheral circadian clocks. Neuron. 2012;74(2):246–260. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwamoto A., Kawai M., Furuse M., Yasuo S. Effects of chronic jet lag on the central and peripheral circadian clocks in CBA/N mice. Chronobiology International. 2014;31(2):189–198. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2013.837478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamaguchi Y., Suzuki T., Mizoro Y., et al. Mice genetically deficient in vasopressin V1a and V1b receptors are resistant to jet lag. Science. 2013;342(6154):85–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1238599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura W., Yamazaki S., Takasu N. N., Mishima K., Block G. D. Differential response of Period 1 expression within the suprachiasmatic nucleus. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(23):5481–5487. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0889-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdullah E., Idris A., Saparon A. PAPR reduction using SCS-SLM technique in STFBC MIMO-OFDM. Journal of Engineering and Applied Science. 2017;12:3218–3221. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sookoian S., Gemma C., Fernández Gianotti T., et al. Effects of rotating shift work on biomarkers of metabolic syndrome and inflammation. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2007;261(3):285–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landis C. A. Physiological and behavioral aspects of normal sleep. In: Redeker N., McEnany G., editors. Sleep Disorders and Sleep Promotion in Nursing Practice. New York, NY, USA: Springer Publishing Company, LLC; 2011. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ambrosius U., Lietzenmaier S., Wehrle R., et al. Heritability of sleep electroencephalogram. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;64(4):344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Gennaro L., Marzano C., Fratello F., et al. The electroencephalographic fingerprint of sleep is genetically determined: a twin study. Annals of Neurology. 2008;64(4):455–460. doi: 10.1002/ana.21434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bjorness T., Greene R. Adenosine and sleep. Current Neuropharmacology. 2009;7(3):238–245. doi: 10.2174/157015909789152182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sehgal A., Mignot E. Genetics of sleep and sleep disorders. Cell. 2011;146(2):194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cirelli C. The genetic and molecular regulation of sleep: from fruit flies to humans. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10(8):549–560. doi: 10.1038/nrn2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raizen D. M., Zimmerman J. E., Maycock M. H., et al. Lethargus is a Caenorhabditis elegans sleep-like state. Nature. 2008;451(7178):569–572. doi: 10.1038/nature06535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langmesser S., Franken P., Feil S., Emmenegger Y., Albrecht U., Feil R. cGMP-dependent protein kinase type I is implicated in the regulation of the timing and quality of sleep and wakefulness. PLoS One. 2009;4(1, article e4238) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bushey D., Huber R., Tononi G., Cirelli C. Drosophila hyperkinetic mutants have reduced sleep and impaired memory. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(20):5384–5393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0108-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koh K., Joiner W. J., Wu M. N., Yue Z., Smith C. J., Sehgal A. Identification of SLEEPLESS, a sleep-promoting factor. Science. 2008;321(5887):372–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1155942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keene A. C., Duboué E. R., McDonald D. M., et al. Clock and cycle limit starvation-induced sleep loss in Drosophila. Current Biology. 2010;20(13):1209–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allebrandt K. V., Amin N., Müller-Myhsok B., et al. A KATP channel gene effect on sleep duration: from genome-wide association studies to function in Drosophila. Molecular Psychiatry. 2011;18(1):122–132. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Depner C. M., Stothard E. R., Wright K. P. Metabolic consequences of sleep and circadian disorders. Current Diabetes Reports. 2014;14(7):p. 507. doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0507-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Markwald R. R., Melanson E. L., Smith M. R., et al. Impact of insufficient sleep on total daily energy expenditure, food intake, and weight gain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(14):5695–5700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216951110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyagawa T., Kawashima M., Nishida N., et al. Variant between CPT1B and CHKB associated with susceptibility to narcolepsy. Nature Genetics. 2008;40(11):1324–1328. doi: 10.1038/ng.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toyoda H., Honda Y., Tanaka S., et al. Narcolepsy susceptibility gene CCR3 modulates sleep-wake patterns in mice. PLos One. 2017;12(11, article e0187888) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Winkelmann J., Czamara D., Schormair B., et al. Correction: genome-wide association study identifies novel restless legs syndrome susceptibility loci on 2p14 and 16q12.1. PLoS Genetics. 2011;7 doi: 10.1371/annotation/393ad2d3-df4f-4770-87bc-00bfabf79362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stefansson H., Rye D. B., Hicks A., et al. A genetic risk factor for periodic limb movements in sleep. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(7):639–647. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Winkelmann J., Lichtner P., Schormair B., et al. Variants in the neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS, NOS1) gene are associated with restless legs syndrome. Movement Disorders. 2008;23(3):350–358. doi: 10.1002/mds.21647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imeri L., Opp M. R. How (and why) the immune system makes us sleep. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10(3):199–210. doi: 10.1038/nrn2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rihel J., Prober D. A., Arvanites A., et al. Zebrafish behavioral profiling links drugs to biological targets and rest/wake regulation. Science. 2010;327(5963):348–351. doi: 10.1126/science.1183090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Funato H., Miyoshi C., Fujiyama T., et al. Forward-genetics analysis of sleep in randomly mutagenized mice. Nature. 2016;539(7629):378–383. doi: 10.1038/nature20142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barger L. K., Rajaratnam S. M. W., Cannon C. P., et al. Short sleep duration, obstructive sleep apnea, shiftwork, and the risk of adverse cardiovascular events in patients after an acute coronary syndrome. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2017;6(10, article e006959) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lim A. J. R., Huang Z., Chua S. E., Kramer M. S., Yong E. L. Sleep duration, exercise, shift work and polycystic ovarian syndrome-related outcomes in a healthy population: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2016;11(11, article e0167048) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee S., Kim H.-R., Byun J., Jang T. Sleepiness while driving and shiftwork patterns among Korean bus drivers. Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2017;29(1) doi: 10.1186/s40557-017-0203-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Espitia-Bautista E., Velasco-Ramos M., Osnaya-Ramírez I., Ángeles-Castellanos M., Buijs R. M., Escobar C. Social jet-lag potentiates obesity and metabolic syndrome when combined with cafeteria diet in rats. Metabolism. 2017;72:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oike H., Sakurai M., Ippoushi K., Kobori M. Time-fixed feeding prevents obesity induced by chronic advances of light/dark cycles in mouse models of jet-lag/shift work. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2015;465(3):556–561. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bass J., Takahashi J. S. Circadian integration of metabolism and energetics. Science. 2010;330(6009):1349–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.1195027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takahashi J. S., Hong H.-K., Ko C. H., McDearmon E. L. The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder: implications for physiology and disease. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2008;9(10):764–775. doi: 10.1038/nrg2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang L., Chung B. Y., Lear B. C., et al. DN1p circadian neurons coordinate acute light and PDF inputs to produce robust daily behavior in Drosophila. Current Biology. 2010;20(7):591–599. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lamia K. A., Storch K.-F., Weitz C. J. Physiological significance of a peripheral tissue circadian clock. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(39):15172–15177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806717105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Turek F. W., Joshu C., Kohsaka A., et al. Obesity and metabolic syndrome in circadian Clock mutant mice. Science. 2005;308(5724):1043–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.1108750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scheer F. A. J. L., Hilton M. F., Mantzoros C. S., Shea S. A. Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(11):4453–4458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808180106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reinberg A., Ashkenazi I. Internal desynchronization of circadian rhythms and tolerance to shift work. Chronobiology International. 2008;25(4):625–643. doi: 10.1080/07420520802256101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pariante C. M. Risk factors for development of depression and psychosis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1179(1):144–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Campino C., Valenzuela F., Arteaga E., et al. Melatonin reduces cortisol response to ACTH in humans. Revista Médica de Chile. 2008;136(11):1390–1397. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872008001100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pariante C. M. Pituitary volume in psychosis: the first review of the evidence. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2008;22(2 Supplement):76–81. doi: 10.1177/0269881107084020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vogel M., Braungardt T., Meyer W., Schneider W. The effects of shift work on physical and mental health. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2012;119(10):1121–1132. doi: 10.1007/s00702-012-0800-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boscolo P., Di Gioacchino M., Reale M., Muraro R., Di Giampaolo L. Work stress and innate immune response. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology. 2011;24:51S–54S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pandi-Perumal S. R., Srinivasan V., Spence D. W., Cardinali D. P. Role of the melatonin system in the control of sleep. CNS Drugs. 2007;21(12):995–1018. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200721120-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rahman S. A., Marcu S., Kayumov L., Shapiro C. M. Altered sleep architecture and higher incidence of subsyndromal depression in low endogenous melatonin secretors. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2010;260(4):327–335. doi: 10.1007/s00406-009-0080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Di Milia L., Waage S., Pallesen S., Bjorvatn B. Shift work disorder in a random population sample – prevalence and comorbidities. PLoS One. 2013;8(1, article e55306) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mishima K., Tozawa T., Satoh K., Saitoh H., Mishima Y. The 3111T/C polymorphism of hClock is associated with evening preference and delayed sleep timing in a Japanese population sample. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2005;133B(1):101–104. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smith M. R., Eastman C. I. Shift work: health, performance and safety problems, traditional countermeasures, and innovative management strategies to reduce circadian misalignment. Nature and Science of Sleep. 2012;4:111–132. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S10372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carpen J. D., Archer S. N., Skene D. J., Smits M., Schantz M. A single-nucleotide polymorphism in the 5′-untranslated region of the hPER2 gene is associated with diurnal preference. Journal of Sleep Research. 2005;14(3):293–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pereira D. S., Tufik S., Louzada F. M., et al. Association of the length polymorphism in the human Per3 gene with the delayed sleep-phase syndrome: does latitude have an influence upon it? Sleep. 2005;28(1):29–32. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Markwald R. R., Wright K. P., Jr. Sleep Loss and Obesity. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2012. Circadian misalignment and sleep disruption in shift work: Implications for fatigue and risk of weight gain and obesity. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Buxton O. M., Cain S. W., O'Connor S. P., et al. Adverse metabolic consequences in humans of prolonged sleep restriction combined with circadian disruption. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4(129, article 129ra43) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Drake C. L., Wright K. P. Shift work, shift-work disorder, and jet lag. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 2011;1:784–798. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ruggiero J. S., Redeker N. S. Effects of napping on sleepiness and sleep-related performance deficits in night-shift workers: a systematic review. Biological Research for Nursing. 2014;16(2):134–142. doi: 10.1177/1099800413476571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Marcheva B., Ramsey K. M., Buhr E. D., et al. Disruption of the clock components CLOCK and BMAL1 leads to hypoinsulinaemia and diabetes. Nature. 2010;466(7306):627–631. doi: 10.1038/nature09253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sack R. L., Auckley D., Auger R. R., et al. Circadian rhythm sleep disorders: part I, basic principles, shift work and jet lag disorders. Sleep. 2007;30(11):1460–1483. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wright K. P., Jr., Bogan R. K., Wyatt J. K. Shift work and the assessment and management of shift work disorder (SWD) Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2013;17(1):41–54. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhao Y., Castellanos F. X. Annual research review: discovery science strategies in studies of the pathophysiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders - promises and limitations. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2016;57(3):421–439. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hawi Z., Cummins T. D. R., Tong J., et al. The molecular genetic architecture of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Molecular Psychiatry. 2015;20(3):289–297. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jeste S. S., Geschwind D. H. Disentangling the heterogeneity of autism spectrum disorder through genetic findings. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2014;10(2):74–81. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Milham M. P. Open neuroscience solutions for the connectome-wide association era. Neuron. 2012;73(2):214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.de Sousa R. T., Loch A. A., Carvalho A. F., et al. Genetic studies on the tripartite glutamate synapse in the pathophysiology and therapeutics of mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(4):787–800. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Burmeister M., McInnis M. G., Zöllner S. Psychiatric genetics: progress amid controversy. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2008;9(7):527–540. doi: 10.1038/nrg2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Amstadter A. B., Maes H. H., Sheerin C. M., Myers J. M., Kendler K. S. The relationship between genetic and environmental influences on resilience and on common internalizing and externalizing psychiatric disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2016;51(5):669–678. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1163-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sawamura N., Ando T., Maruyama Y., et al. Nuclear DISC1 regulates CRE-mediated gene transcription and sleep homeostasis in the fruit fly. Molecular Psychiatry. 2008;13(12):1138–1148. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kieseppä T., Partonen T., Haukka J., Kaprio J., Lönnqvist J. High concordance of bipolar I disorder in a nationwide sample of twins. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(10):1814–1821. doi: 10.1176/ajp.161.10.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mühleisen T. W., Leber M., Schulze T. G., et al. Genome-wide association study reveals two new risk loci for bipolar disorder. Nature Communications. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Craddock N., Sklar P. Genetics of bipolar disorder: successful start to a long journey. Trends in Genetics. 2009;25(2):99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Psychiatric GWAS Consortium Bipolar Disorder Working Group. Large-scale genome-wide association analysis of bipolar disorder identifies a new susceptibility locus near ODZ4. Nature Genetics. 2012;43:977–983. doi: 10.1038/ng.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gatt J. M., Burton K. L. O., Williams L. M., Schofield P. R. Specific and common genes implicated across major mental disorders: a review of meta-analysis studies. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2015;60:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kato T. Whole genome/exome sequencing in mood and psychotic disorders. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2015;69(2):65–76. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kessler R. C., Chiu W. T., Demler O., Merikangas K. R., Walters E. E. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Koido K., Traks T., Balõtšev R., et al. Associations between LSAMP gene polymorphisms and major depressive disorder and panic disorder. Translational Psychiatry. 2012;2(8, article e152) doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Moylan S., Maes M., Wray N. R., Berk M. The neuroprogressive nature of major depressive disorder: pathways to disease evolution and resistance, and therapeutic implications. Molecular Psychiatry. 2013;18(5):595–606. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Levinson D. F. The genetics of depression: a review. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60(2):84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.López-León S., Janssens A. C. J. W., González-Zuloeta Ladd A. M., et al. Meta-analyses of genetic studies on major depressive disorder. Molecular Psychiatry. 2008;13(8):772–785. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kohli M. A., Lucae S., Saemann P. G., et al. The neuronal transporter gene SLC6A15 confers risk to major depression. Neuron. 2011;70(2):252–265. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fritschi L., Glass D. C., Heyworth J. S., et al. Hypotheses for mechanisms linking shiftwork and cancer. Medical Hypotheses. 2011;77(3):430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Khan S., Ullah M. W., Siddique R., et al. Role of recombinant DNA technology to improve life. International Journal of Genomics. 2016;2016:14. doi: 10.1155/2016/2405954.2405954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Xiang S., Coffelt S. B., Mao L., Yuan L., Cheng Q., Hill S. M. Period-2: a tumor suppressor gene in breast cancer. Journal of Circadian Rhythms. 2008;6(1):p. 4. doi: 10.1186/1740-3391-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhu Y., Stevens R. G., Hoffman A. E., et al. Epigenetic impact of long-term shiftwork: pilot evidence from circadian genes and whole-genome methylation analysis. Chronobiology International. 2011;28(10):852–861. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2011.618896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Filipski E., Innominato P. F., Wu M., et al. Effects of light and food schedules on liver and tumor molecular clocks in mice. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97(7):507–517. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Samulin Erdem J., Notø H. Ø., Skare Ø., et al. Mechanisms of breast cancer risk in shift workers: association of telomere shortening with the duration and intensity of night work. Cancer Medicine. 2017;6(8):1988–1997. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wood P. A., Yang X., Taber A., et al. Period 2 mutation accelerates ApcMin/+ tumorigenesis. Molecular Cancer Research. 2008;6(11):1786–1793. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Flynn-Evans E. E., Mucci L., Stevens R. G., Lockley S. W. Shiftwork and prostate-specific antigen in the national health and nutrition examination survey. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2013;105(17):1292–1297. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lee S., Donehower L. A., Herron A. J., Moore D. D., Fu L. Disrupting circadian homeostasis of sympathetic signaling promotes tumor development in mice. PLoS One. 2010;5(6, article e10995) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yang X., Wood P. A., Oh E.-Y., Du-Quiton J., Ansell C. M., Hrushesky W. J. M. Down regulation of circadian clock gene period 2 accelerates breast cancer growth by altering its daily growth rhythm. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2009;117(2):423–431. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0133-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gery S., Komatsu N., Baldjyan L., Yu A., Koo D., Koeffler H. P. The circadian gene per1 plays an important role in cell growth and DNA damage control in human cancer cells. Molecular Cell. 2006;22(3):375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Reeder S. B., Hu H. H., Sirlin C. B. Proton density fat-fraction: a standardized MR-based biomarker of tissue fat concentration. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2012;36(5):1011–1014. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Papagiannakopoulos T., Bauer M. R., Davidson S. M., et al. Circadian rhythm disruption promotes lung tumorigenesis. Cell Metabolism. 2016;24(2):324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Blanch A., Torrelles B., Aluja A., Salinas J. A. Age and lost working days as a result of an occupational accident: a study in a shiftwork rotation system. Safety Science. 2009;47(10):1359–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2009.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Admi H., Tzischinsky O., Epstein R., Herer P., Lavie P. Shift work in nursing: is it really a risk factor for nurses’ health and patients’ safety? Nursing Economics. 2008;26(4):250–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tüchsen F., Christensen K. B., Lund T. Shift work and sickness absence. Occupational Medicine. 2008;58(4):302–304. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqn019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Takahashi M., Tanigawa T., Tachibana N., et al. Modifying effects of perceived adaptation to shift work on health, wellbeing, and alertness on the job among nuclear power plant operators. Industrial Health. 2005;43(1):171–178. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.43.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Di Milia L., Smith P. A., Folkard S. A validation of the revised circadian type inventory in a working sample. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39(7):1293–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]