Abstract

This study examined physiological correlates (cortisol and α-amylase [AA]) of peer victimization and aggression in a sample of 228 adolescents (45% male, 55% female; 90% African American; M age = 14 years, SD = 1.6 years) who participated in a longitudinal study of stress, physiology, and adjustment. Adolescents were classified into victimization/aggression groups based on patterns with three waves of data. At Wave 3, youth completed the Social Competence Interview (SCI), and four saliva samples were collected prior to, during, and following the SCI. Repeated-measures analyses of variance with victimization/aggression group as the predictor, and physiological measures as outcomes, controlling for time of day, pubertal status, and medication use revealed significant Group×SCI Phase interactions for salivary AA (sAA), but not for cortisol. The results did not differ by sex. For analyses with physical victimization/aggression, aggressive and nonaggressive victims showed increases in sAA during the SCI, nonvictimized aggressors showed a decrease, and the normative contrast group did not show any change. For analyses with relational victimization/aggression, nonaggressive victims were the only group who demonstrated sAA reactivity. Incorporating physiological measures into peer victimization studies may give researchers and clinicians insight into youth’s behavior regulation, and help shape prevention or intervention efforts.

Peer victimization and aggression during adolescence is highly prevalent and has negative consequences at the individual and societal levels. Although rates vary, in a recent report by the National Center for Education Statistics, 32.2% of 12- to 18-year-olds reported being victimized at school (Dinkes, Kemp, & Baum, 2009). In a nationally representative sample of over 15,000 students in Grades 6 through 10, researchers found that 29.9% reported involvement in moderate or frequent bullying, which included being victimized by peers, aggressing against peers, or being both a victim and an aggressor (Nansel et al., 2001). Experiences of peer victimization and aggressive behavior toward peers are particularly important to examine during early and middle adolescence, as the need for acceptance from peers is particularly salient in this developmental period (Gavin & Furman, 1989). Peer networks are essential to the development of social skills (Fischer, Sollie, & Morrow, 1986), and social comparison to peers is a central process by which adolescents develop their identity (Seltzer, 1989). Thus, disruptions to peer relationships have great significance for youth.

Researchers studying peer victimization and aggression typically focus on characteristics of individuals, risk and protective factors, and outcomes for youth. Recently, there has been a call for researchers to incorporate physiological measures into research (Hazler, Carney, & Granger, 2006). Studying a child’s physiological reactions to stress can give insight into behavior regulation, help identify children who need prevention or intervention, and serve as markers of treatment progress. Although this has garnered considerable attention in the area of aggression, research specific to peer victimization and physiological responses is sparse. The present study addressed this gap in the literature by linking physiological responses to adolescents’ peer victimization and aggression experiences during this developmental time frame.

Several theoretical perspectives informed our study. First, based on stress and coping theory (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), we believe that peer victimization, particularly chronic victimization, is stressful and threatens youth in a variety of ways. A history of peer victimization may “prime” youth to be physiologically reactive to stress. Our previous work on psychosocial correlates of community-based victimization indicates this type of victimization evokes a number of concerns in youth, including fears of negative evaluation by others, and concerns related to loss of relationships (Kliewer & Sullivan, 2008). Second, both theory and research on chronic stress indicate that repeated activation of the hypothalmic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and sympathetic nervous system (SNS) can lead to negative effects on the individual (McEwen & Seeman, 2006; Taylor, Lerner, Sage, Lehman, & Seeman, 2004; Watson, Fischer, & Andreas, 2004). Allostatic load is the psychological and biological impact on the body from the repeated activation and deactivation of these systems (McEwen & Seeman, 2006). These changes can include a heightened or dampened response to stress (Gump & Matthews, 1999). Researchers repeatedly have demonstrated that there is a link between early life experiences and environments and the regulation of these systems (McEwen & Seeman, 2006; Taylor et al., 2004). Based on this idea, the current study explored how chronic peer victimization either by itself or in combination with aggressive behavior impacted the physiological responses of the HPA axis and SNS in adolescents.

Types of Aggression and Victimization

Researchers have identified both forms and types of aggression. Forms of aggression typically fall into one of two categories: direct and indirect. Direct aggression is verbal and physical behavior aimed at individuals with the intent to harm (Björkqvist, Lagerspetz, & Kaukiainen, 1991; Little, Henrich, Jones, & Hawley, 2003). Indirect aggression involves inflicting pain in such a manner that the perpetrator gives the impression that there has been no intention to hurt (Björkqvist et al., 1991). Indirect aggression is more subtle compared to the “in your face” aspects of direct aggression (Little et al., 2003, p. 122; Underwood, 2003); thus, it can be a more covert form of aggression that often allows the aggressor to go undetected.

Two frequently researched types of aggression are physical and relational. Physical aggression is a direct form of aggression and involves the intent to harm using physical force such as hitting, punching, or kicking (Ostrov, 2006). Relational aggression is defined as acts that are intended to damage another individual’s friendships or social status (Little et al., 2003). Relational aggression usually involves social manipulation such as spreading rumors, gossiping, threats to withdraw friendship, or ignoring the individual (Crick, 1997; Crick, Ostrov, & Werner, 2006; Henington, Hughes, Cavell, & Thompson, 1998; Ostrov, 2006; Sullivan, Farrell, & Kliewer, 2006; Underwood, 2003). Unlike physical aggression, relational aggression can be both direct and indirect.

Nonvictimized Aggressors, Aggressive Victims, and Nonaggressive Victims

Several prior studies have classified adolescents involved in perpetrating and/or being victimized in peer contexts into typologies (e.g., Hanish & Guerra, 2004; Schwartz, 2000), and our study does as well. Victims of aggression have been classified into two distinct categories: nonaggressive or “passive” victims and aggressive victims (Hanish & Guerra, 2004; Olweus, 1993; Perry, Kusel, & Perry, 1988; Schwartz, 2000). The nonaggressive victim engages in a submissive and inhibited social style (Schwartz, 2000; Schwartz, Dodge, Petit, & Bates, 1997). Their behaviors communicate to peers that they are insecure in interpersonal interactions and not likely to retaliate in response to victimization experiences (Olweus, 1993). Aggressive victims, in contrast, are both anxious and aggressive (Olweus, 1993). Although a variety of terms are used for the groups, for the purposes of the current paper adolescents were classified as nonvictimized aggressors, aggressive victims, and nonaggressive victims (Olweus, 1993; Perry, Perry, & Kennedy, 1992; Schwartz, 2000). In addition, we included a normative contrast subgroup of youth who were neither highly aggressive nor victimized.

Aggressors are intentionally physically or relationally aggressive toward other adolescents (Olweus, 1993). Researchers have demonstrated that aggression and victimization are associated with a host of negative psychosocial consequences, including long-term outcomes. Aggressors are more likely to use alcohol and cigarettes, engage in delinquent behavior, have poor academic performance, and a negative perception of the school climate (Nansel et al., 2001; van der Wal, de Wit, & Hirasing, 2003). Although aggressors may be able to exert power in their peer group, interactions with them are frequently avoided and they often are disliked (Juvonen, Graham, & Schuster, 2003; Schwartz, 2000; Veenstra et al., 2005). Victims of aggression have greater difficulty making friends, are faced with the stress of being aggressed against, and are often avoided by others in an effort to maintain social status (Perry et al., 1988; Nansel et al., 2001). Victims of peer aggression also reported more symptoms of depression and lower self-esteem as young adults when compared to nonvictimized peers (Olweus, 1993). Aggressive victims may be at particularly high risk for concurrent and later adjustment difficulties (Haynie et al., 2001; Juvonen et al., 2003; Nansel et al., 2001; Solberg, Olweus, & Endresen, 2007). In studies examining differences in psychosocial functioning between the three groups, aggressive victims had the worst outcomes and were characterized by higher rates of conduct problems, higher rates of depressive symptoms and feelings of loneliness, and poorer school performance (Haynie et al., 2001; Juvonen et al., 2003; Schwartz, 2000). Although many researchers have characterized these groups on psychosocial adjustment, the ways in which these adolescents may differ physiologically in response to stress has not been studied.

Physiological Responses to Stress

Incorporating physiological measures into studies of peer victimization and aggression can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the individual and the short- and long-term consequences of victimization and aggression toward peers. This is important because behavior problems only moderately predict later psychopathology (Bauer, Quas, & Boyce, 2002). Thus, physiological indicators may improve our power to predict later adjustment.

Of particular interest to researchers are the stress hormone, cortisol, and the enzyme, α-amylase (AA). Both cortisol and AA are released by the body when it is responding to stressors. Cortisol is secreted following the activation of the HPA axis. This axis influences activity of the immune system and organizes behavioral responses to threat (Dettling, Gunnar, & Donzella, 1999). Healthy adaptation depends upon the body’s ability to increase production of cortisol in stressful situations and reduce production when the stressor is removed (Klimes-Dougan, Hastings, Granger, Usher, & Zahn-Waxler, 2001).

AA is measured to assess the response of the SNS to stress. The SNS is responsible for the fight or flight reaction in the body (Gordis, Granger, Susman, & Trickett, 2006). It increases heart rate, blood flow to muscles, and blood glucose. Salivary AA (sAA) increases in the saliva during sympathetic activity and is produced by the salivary glands (Gordis, Granger, Susman, & Trickett, 2008; Granger, Kivlighan, el-Sheikh, Gordis, & Stroud, 2007). Although it is not representative of AA throughout the body, increases in sAA have been found in the body following physically and psychologically stressful situations (Kivlighan & Granger, 2006; Granger, Kivlighan, el-Sheikh, et al., 2007). Studies examining the changes in sAA in response to stress have consistently shown significant results indicating sAA is reflective of the biological response to psychological stressors (Nater & Rohleder, 2009).

Physiological Measures and Peer Victimization

Despite the plethora of research in the area of peer victimization, research on the physiological correlates of peer victimization during adolescence is limited. We could only locate three studies, all recent, that have addressed the issue with early and middle adolescents. Kliewer (2006) examined the relation between witnessing violence, peer victimization, and cortisol. Participants were African American early adolescents living in an urban area characterized by high stress and violence. The adolescents completed measures of peer victimization, witnessed violence, and internalizing symptoms. Caregivers completed measures on major life events and internalizing symptoms. Cortisol samples were collected in the laboratory surrounding a task that required participants to watch a violent video clip and in the week following the laboratory session (Kliewer, 2006). Results demonstrated that peer victimization was associated with lower levels of cortisol at awakening and increases in cortisol from pre- to posttask following the video clip.

A subsequent study examined the relation between being a victim of bullying and cortisol in a sample of largely Caucasian adolescents living in low-violence areas and of moderate socioeconimic status (Vaillancourt et al., 2008). Researchers collected saliva samples and measures of physical, verbal, and social bullying experiences, depression, anxiety, and pubertal status. Vaillancourt et al. (2008) found that occasional verbal peer victimization, but not physical or social victimization, was associated with higher levels of cortisol in boys and lower levels in girls after controlling for pubertal status, age, depression, and anxiety.

A third study examined whether cortisol and sAA in anticipation of and in response to a laboratory task moderated the relation between peer victimization and aggression in a sample of 132 elementary school-age children (Rudolph, Troop-Gordon, & Granger, 2010). The victimization measure included indicators of both overt and relational victimization. Although there were no zero-order associations between victimization or aggression and the physiological measures, the relation between peer victimization and aggression was strongest in youth with the highest pretask cortisol and sAA levels. Further, sAA reactivity was positively associated with both victimization and teacher-rated aggression, but only in girls.

Taken together, these findings suggest that peer victimization is associated with a heightened cortisol response, at least for some groups of younger adolescents. Less is known about youth’s SNS responses based on their history of peer victimization experiences.

Physiological Measures and Aggression

Traditionally, physiological researchers have monitored heart rate, vagal tone, and skin conductance, or collected plasma samples to measure responses to stress. Despite some studies with opposing results, researchers have concluded that these measures are reliable markers for childhood antisocial behavior (Raine, 1996; Ortiz & Raine, 2004; Scarpa & Raine, 1997; van Goozen, Matthys, Cohen-Kettenis, Buitelaar, & van Engeland, 2000). When using these measures, researchers most frequently found that higher rates of aggressive behavior are associated with lower levels of stress reactivity in adolescents (Gordis et al., 2006; Moss, Vanykov, & Martin, 1995; van Goozen et al., 1998).

Moss et al. (1995) studied salivary cortisol responses in two groups of prepubertal boys: those with fathers who had a substance use disorder or antisocial behavior and those with fathers who did not. Boys at higher risk for these types of dysregulated behaviors had lower cortisol responsivity when faced with an anticipated stressor than boys who were at average risk for such disorders. van Goozen et al. (1998) also examined cortisol levels in their study of 8- to 11-year-old boys with oppositional-defiant disorder or conduct disorder. Results indicated that boys with low anxiousness and high levels of externalizing behaviors had lower levels of cortisol during stress. In both studies, researchers also discovered that basal cortisol levels and the level of hyporesponsivity was associated with the magnitude of aggressive behavior (Moss et al., 1995; van Goozen et al., 1998). Shoal, Giancola, and Kirillova (2003) found that this relation between low cortisol levels and aggressive behavior persisted over time. Pre-adolescent cortisol levels for boys aged 10 to 12 were related to aggressive behavior in middle adolescence at age 15 to 17.

Research on the physiological correlates of victims’ and aggressors’ responses to stress, provides some empirical foundation for the current study. Based on these findings, we expected that aggressive behavior would be associated with a suppression of victims’ physiological responses to a stressor, relative to nonaggressive victims.

Gender Differences in Physiological Responses

The relation between aggression and cortisol is not consistent across sex, and little is known about sex differences in physiological responses to peer victimization. Specifically, low cortisol levels are not consistently associated with externalizing behaviors in females (Shirtcliff, Granger, Booth, & Johnson, 2005). This may be due to biological differences in how males and females deal with stress or that researchers have overlooked females in previous research. One study on adolescent girls in their final stages of puberty who met the criteria for conduct disorder found an association between conduct disorder and low cortisol levels (Pajer, Gardner, Rubin, Perel, & Neal, 2001). In a study of both boys and girls, the association between low cortisol levels and externalizing behaviors was only found in boys (Shirtcliff et al., 2005). Thus, we examined sex as a moderator in the current study.

The Current Study

The purpose of the current study was to examine physiological correlates of peer victimization and aggression experiences. We sought to extend the literature in several ways. First, we examined the joint influences of victimization and aggression on physiological stress responses. None of the previously published studies on peer victimization and physiological stress responses considered how patterns of victimization and aggression may correlate with physiological stress responses. Because peer victimization and aggression are consistently and moderately correlated, and because patterns of victimization and aggression have different psychological correlates, we believed it was important to consider these two constructs simultaneously. Consistent with the work of other researchers, we examined both physical and relational victimization as well as physical and relational aggression in our analyses. Second, unlike most previous research, our data is prospective. We classified adolescents based on three waves of data (over a 2-year period) on their victimization and aggression experiences, and prospectively examined physiological responses to stress, rather than collecting data on victimization retrospectively at the time of the physiological assessments. Third, we studied physiological responses in two biological systems: the HPA axis and the SNS. Thus, we assayed our saliva samples both for cortisol, a hormone, and AA, an enzyme. A secondary purpose of the study was to examine how patterns of physiological responses to peer victimization and aggression differ across sex. The literature is equivocal here, so we examined sex as an exploratory moderator.

We hypothesized that being victimized by peers would be associated with (a) greater SNS activation in response to stress and (b) greater cortisol reactivity. However, we expected that these patterns would be moderated by aggressive behavior, such that aggressive victims would show lower physiological reactivity in both systems. Given the dearth of literature on physiological responses to physical versus relational victimization and that both types of victimization are stressful for youth, we did not have expectations regarding how physiological responses to these types of victimization might differ.

Method

Participants

Participants included 228 youth (45% male, 90% African American/Black, M age = 14.1 years, SD = 1.6 years) who participated in the first three waves of a larger longitudinal study on violence, physiological stress responses, and adjustment, and who had valid physiological protocols. Although the nature of the research questions meant that many of the participating families would be of lower socioeconomic status, there was some diversity in the sample. At the start of the study in 2005, half of the sample had household incomes of $301 to $400/week or less. About a quarter (27.8%) of the caregivers had not completed high school, 23.6% had completed high school or had a general education diploma, 37.5% had some education beyond high school, including an associate’s or vocational degree, and 9.9% had a bachelor’s degree or higher. A range of family structures was represented in the sample, although many (38.5%) of the caregivers had never married. A third (33.8%) of caregivers were married or cohabitating at the time of the study, 15% were separated, 10.3% were divorced, and 2.3% were widowed.

Procedure

Participants were recruited from neighborhoods in the greater Richmond, Virginia, metropolitan area. US Census data from 2000 indicate that 61% of 15- to 24-year olds in Richmond were African American, and 61% of children lived in neighborhoods classified as high in poverty (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2004). Richmond was ranked the ninth most dangerous city among all US cities with populations over 75,000 based on 2003 FBI violent crime statistics (Nolan, 2004). Participants were recruited from neighborhoods that had high levels of violence and/or poverty based on police statistics and census data (e.g., DeNavas-Walt, Proctor & Lee, 2005). For example, participants were recruited from neighborhoods that had low-income housing; and most of these neighborhoods also had higher levels of crime (i.e., murder, robbery, assault) relative to other areas of the city. They were recruited through community agencies and events, and by canvassing qualifying neighborhoods via flyers posted door to door. Eligible families needed to speak English, have a fifth or eighth grader living in the home, and have female caregiver available to be interviewed. The participation rate of eligible families was 63% (calculated by dividing the number of families who enrolled in the study by the number of eligible families who received flyers). Eligible respondents were scheduled for interviews, which were conducted in participants’ homes unless a family requested to be interviewed elsewhere. Most interviews were conducted in the late afternoon or evening when both caregivers and adolescents were home. However, some weekend interviews were conducted earlier in the day.

At each wave, teams of two interviewers arrived at the home for the interviews. The parent interviewer reviewed the consent and assent forms with the family, and answered any questions. The caregiver received a copy of the signed consent form. After the adolescent and their maternal caregiver provided written consent, the caregiver and adolescent separated for their respective interviews. Additional assent was provided by the adolescent before initiating the interviews. Only data from the adolescent participant is reported here. Face to face interviews using visual aids to illustrate the response options were used to collect the data, and all questions were read aloud, with the exception of a small portion of the adolescent interview.

As part of the procedure, adolescents completed the Social Competence Interview (SCI; Ewart, Jorgensen, Suchday, Chen, & Matthews, 2002), a 15–20 min audiotaped interview in which adolescents were asked to reexperience their most stressful event of the past couple months. The SCI was administered at each wave; for the present study we used the SCI at Wave 3. The SCI is designed to promote physiological arousal and has been repeatedly correlated with changes in blood pressure and heart rate (Chen, Matthews, Salomon, & Ewart, 2002; Ewart & Kolodner, 1991). Unlike other studies that use performance based tasks as a stressor, the SCI elicits details about social and environmental stressors in the participant’s life. The SCI has two phases: a hot phase and a cool phase. During the hot phase, the interviewer asks the child to reexperience the stressful event and asks questions about the participant’s thoughts and feelings during the event. The cool phase follows with the interviewer asking the participant to describe how the situation would have ideally ended and what could be done to achieve that outcome. Thus, the specific stressor discussed differs for each individual. For this project, adolescents were prompted to discuss situations that involved witnessing or experiencing violence. As a guide for choosing a stressful event, adolescents were asked to rank eight categories of different types of violence from most to least stressful. The interviewer then asked the adolescent to identify a recent, stressful situation that exemplified the category they deemed the most stressful.

The events were classified using a coding system developed for the study that included 14 different types of events (Reid-Quinones et al., 2011). All coders received approximately 20 hr of training by the third author, and achieved reliability (κs > 0.80) on each code prior to coding independently. Of interest to the current study, three of the codes reflected physical, verbal, or relational victimization by peers.

Saliva samples were collected from the adolescents before the start of the SCI, at the end of the “hot” phase, and 10 and 20 min later. Participants were instructed not to exercise, to eat, or to drink caffeinated beverages 2 hr prior to the SCI.

Immediately following the SCI adolescents rated the extent to which they felt angry, sad, scared, and embarrassed in the situation they described in the SCI. Ratings were made on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot). Adolescents then completed a 24-item threat appraisal measure (Kliewer & Sullivan, 2008) regarding the event they discussed in the SCI. Adolescents rated the extent to which they experienced different types of threats on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot). Threats of physical harm to oneself, harm to others, negative evaluation by others, negative self-evaluation, material losses, and loss of relationships are captured in this measure.

Tests for interviewer race and sex effects revealed no systematic biases, ps > .10. Interviews lasted approximately 2.5 hr and participating families received $50 in gift cards at each wave. The project was approved by the institutional review board at the first authors’ institution. Because of the level of risk in the study, additional safety precautions were taken. First, a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health. Second, interviewers received detailed training in how to respond to caregiver or adolescent distress.

Measures

Victimization and aggression

At each of the first three waves of the study, adolescents completed measures of overt physical and relational peer victimization and aggression during the past month. Overt and relational victimization by peers was assessed with a modified version of The Social Experience Questionnaire (Crick & Grotpeter, 1996). Several items were slightly reworded to be more appropriate for a middle school context and the response format was changed to reflect the frequency of these behaviors in the past 30 days. One item, “Had someone start a rumor about you” was added to the Relational Victimization Scale. For all items, students indicated how frequently each behavior happened to them in the past 30 days using a 6-point anchored scale (e.g., 1 = never, 2 =1–2 times, 3 =3–5 times, 4 =6–9 times, 5 =10–19 times, and 6 = 20 or more times). The eight-item Overt Victimization Scale measures the frequency of physical harm or threatened physical harm by peers (e.g., “been hit by another kid,” “a student threatened to hit or physically harm you”). The six-item Relational Victimization Scale assessed the frequency of victimization aimed at damaging or manipulating peer relationships (e.g., “had a kid tell lies about you to make other kids not like you anymore”). The α values for the Overt Victimization Scale were 0.78, 0.85, and 0.83 for Waves 1–3, respectively, and 0.75, 0.82, and 0.83 for the Relational Victimization Scale at Waves 1–3.

Physical and relational aggression were assessed with two subscales from the Problem Behavior Frequency Scales (Farrell, Kung, White, & Valois, 2000). For all items, students indicated how frequently they engaged in each behavior in the past 30 days using a 6-point anchored scale (e.g., 1 = Never, 2 = 1–2 times, 3 = 3–5 times, 4 = 6–9 times, 5 = 10–19 times, and 6 = 20 or more times). The seven items representing overt physical aggression were based on the Centers for Disease Control’s Youth Risk Survey (Kolbe, Kann, & Collins, 1993). The six items representing relational aggression were based on Crick and Grotpeter’s (1995) measure of relational aggression. Several items were reworded to be more appropriate for a middle school context and the response format was changed to reflect the frequency of these behaviors in the past 30 days. One item, “Spread a false rumor about someone” was added to the Relational Aggression Scale. The α values for the Overt Aggression Scale were 0.77, 0.78, and 0.82 for Waves 1–3, respectively, and were 0.66, 0.65, and 0.77 for the Relational Aggression Scale at Waves 1–3.

Controls

Consistent with prior research, controls in the analyses included time of day, pubertal status, and medication use, all collected at Wave 3. Adolescents rated their maturational status using the Pubertal Development Scale (Peterson, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988). The Pubertal Development Scale consists of five markers of pubertal development, which are rated on a 4-point scale. The measure has excellent validity and reliability. The Cronbach α values in this study were 0.76 for girls and 0.82 for boys. Higher levels reflect greater physical maturation.

Previous studies have shown that medication can impact salivary cortisol and AA (Granger, Kivlighan, el-Sheikh, et al., 2007; Hibel, Granger, Cicchetti, & Rogosch, 2007; Hibel, Granger, Kivlighan, & Blair, 2006). Many studies exclude participants on medication from physiological analyses. However, because a sizable percentage of our sample reported being on medication that could affect sAA (29.6%) or cortisol (39.4%) we elected to include these participants in the analyses and control for medication use. All reported medications were reclassified into one of 25 drug categories, then researched to determine their influence on cortisol and sAA. Each category received a designation of “yes there is an influence,” “no there is no influence,” or “unknown influence.” The “yes” and “unknown” categories were combined and compared with the “no influence” category in the analyses. A more detailed description of our procedures is available from the corresponding author.

Physiological responses

The physiological data was collected using salivettes. Adolescents were asked by the interviewer to place a cotton swab in their mouth and chew for about 1 min. The adolescent spit the swab into the salivette tube and the samples were frozen at a −70°C or below until the samples were taken to the laboratory for analysis. The saliva samples were assayed at the General Clinical Research Center at Virginia Commonwealth University for the stress hormone cortisol and the enzyme AA using an enzyme immunoassay specifically designed for saliva analysis. Saliva samples were spun and frozen prior to testing. On the day of the assay, samples were thawed and assayed directly with no further centrifugation. All samples were assayed for salivary cortisol using a highly sensitive enzyme immunoassay US FDA (510k) cleared for use as an in vitro diagnostic measure of adrenal function (Salimetrics, State College, PA). The test used 25 μl of saliva and had a lower limit of sensitivity of 0.007 μg/dl, with a range of sensitivity from 0.007 to 3.0 μg/dl. Samples were assayed in duplicate; average intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were less than 5% and 10%. The assay for sAA employed a chromagenic substrate, 2-chloro-p-nitrophenol, linked to maltotriose. The enzymatic action of sAA on this substrate yields 2-chloro-p-nitrophenol, which can be spectrophotometrically measured at 405 nm using a standard laboratory plate reader. The amount of sAA activity present in the sample is directly proportional to the increase (over a 2-min period) in absorbance at 405 nm. Results are computed in units/milliliter of sAA using the following formula: (absorbance difference per minute×total assay volume [328 ml]×dilution factor [200])/(millimolar absorptivity of 2-chloro-p-nitrophenol [12.9] ×sample volume [0.008 ml] × light path [0.97]). Following Granger, Kivlighan, Fortunato, and colleagues (2007), all samples were assayed in singlet.

Results

Data cleaning and transformation

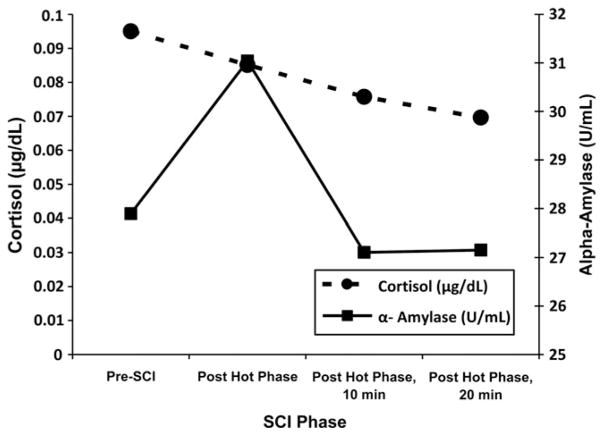

We reviewed the SCI for each participant prior to beginning analysis. Participants were excluded from analyses if the SCI was incomplete, if a stressful event was not recalled, if the participant was not engaged in the process based on the interviewer’s impression, or if the times for the hot and cool phases of the SCI were anomalous. The distributions of sAA and cortisol data were examined and the data were transformed due to skewness and kurtosis. Prior to data transformation, outliers >3 SD above the mean were winsorized using Tukey’s (1977) method, which involves replacing the outlier value with the closest value within the 3 SD range. The sAA data were log transformed, whereas a square root transformation was applied to the cortisol data. The distribution of cortisol and sAA at each of the four time points can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mean values of untransformed salivary α-amylase (U/ml) and cortisol (μg/dl) values across the four time points in the study.

Descriptive information on and correlations among key study variables

Table 1 presents descriptive information on and correlations among the study variables. Peer victimization in the sample was fairly high. For example, in Wave 2 of the study, one-third or more of the sample reported they had been hit (36.0%), pushed (34.4%), yelled at (46.3%), asked to fight (38.6%), or threatened (30.9) by a peer in the previous 30 days. In this same period, students reported have rumors told about them (45.0%), being left out of an activity on purpose (23.3%), having lies told about them (38.7%), and having other kids say mean things about them in order to prevent others from liking them (41.1%). Aggression toward peers likewise was high. Youths reported throwing things at someone to hurt them (39.6%), shoving a peer (46.2%), hitting (41.6%), and threatening to physically harm a peer (23.5%). Youth actively excluded others from a group (32.4%) and left others out of activities on purpose (20.4%). This level of victimization and aggression is consistent with other studies of urban youth (e.g., Sullivan et al., 2006), and it indicates our sample was at fairly high risk for adjustment problems.

Table 1.

Descriptive information on and correlations among the study variables

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex (male) | .13 | .10 | .05 | −.03 | .38 | −.13 | .07 | 0 |

| 2. Physical victimization | .35 | .83 | .28 | .01 | −.04 | .05 | .09 | |

| 3. Physical aggression | .22 | .64 | .11 | −.05 | .04 | .01 | ||

| 4. Relational victimization | .32 | −.01 | −.03 | −.04 | .04 | |||

| 5. Relational aggression | −.02 | −.04 | 0 | −.05 | ||||

| 6. Pubertal status | .01 | .05 | −.02 | |||||

| 7. Time of day | −.05 | −.10 | ||||||

| 8. Medication sAA | .81 | |||||||

| 9. Medication cortisol | ||||||||

| 10. Time 1 sAA | ||||||||

| 11. Time 2 sAA | ||||||||

| 12. Time 3 sAA | ||||||||

| 13. Time 4 sAA | ||||||||

| 14. Time 1 cortisol | ||||||||

| 15. Time 2 cortisol | ||||||||

| 16. Time 3 cortisol | ||||||||

| 17. Time 4 cortisol | ||||||||

| Mean | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 13.42 | — | ||

| SD | 2.40 | 2.28 | 2.42 | 2.34 | 2.98 | — | ||

| % | 29.52 | 39.21 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

|

| ||||||||

| 1. Sex (male) | .06 | .05 | .05 | .06 | .12 | .13 | .13 | .12 |

| 2. Physical victimization | −.12 | .01 | −.06 | −.03 | −.06 | −.06 | −.10 | −.08 |

| 3. Physical aggression | .04 | .03 | .05 | .05 | .07 | .04 | .05 | .06 |

| 4. Relational victimization | −.12 | −.05 | −.08 | −.05 | −.06 | −.06 | −.06 | −.07 |

| 5. Relational aggression | −.07 | −.03 | −.03 | 0 | .02 | .01 | .03 | 0 |

| 6. Pubertal status | −.01 | .03 | .03 | .07 | .05 | .05 | .09 | .08 |

| 7. Time of day | .10 | .13 | .06 | .06 | −.46 | −.45 | −.45 | −.43 |

| 8. Medication sAA | .13 | .14 | .08 | .14 | .08 | .07 | .07 | .02 |

| 9. Medication cortisol | .11 | .14 | .06 | .14 | .09 | .10 | .10 | .09 |

| 10. Time 1 sAA | .76 | .79 | .78 | .02 | 0 | .01 | 0 | |

| 11. Time 2 sAA | .79 | .79 | −.08 | −.02 | −.07 | −.08 | ||

| 12. Time 3 sAA | .82 | −.02 | −.06 | .01 | −.03 | |||

| 13. Time 4 sAA | −.05 | −.08 | −.03 | −.03 | ||||

| 14. Time 1 cortisol | .93 | .90 | .97 | |||||

| 15. Time 2 cortisol | .93 | .88 | ||||||

| 16. Time 3 cortisol | .91 | |||||||

| 17. Time 4 cortisol | ||||||||

| Mean | 27.89 U/ml | 31.04 U/ml | 27.11 U/ml | 27.15 U/ml | 0.10 μg/dl | 0.09 μg/dl | 0.08 μg/dl | 0.07 μg/dl |

| SD | 22.23 | 28.53 | 22.03 | 21.15 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

Note: Correlations > .13 are significant at p < .05. sAA, Salivary α-amylase. sAA is measured units per milliliter, and cortisol is measured in micrograms per deciliter.

Identification of victim–aggressor status

In order to classify youth based on patterns of peer victimization and aggression, we used an approach similar to that of Schwartz (2000). We first standardized then combined overt victimization scores across the three waves of data. We then repeated this process for relational victimization. We then standardized and combined physical aggression scores across Waves 1–3. We repeated this process for relational aggression. We then created distributions based on quartiles. Youth in the bottom quartile of victimization and who were in the top two quartiles on aggression were classified as nonvictimized aggressors. Youth in the top quartile of victimization and who were in the bottom two quartiles on aggression were classified as nonaggressive victims. Youth in the top quartile of victimization and who were in the top two quartiles on aggression were classified as aggressive victims. Youth who were in the bottom two quartiles on both victimization and aggression were classified into a normative contrast subgroup. For physical victimization and aggression, this procedure resulted in identification of 13 nonvictimized aggressors (6.0% of the sample), 16 nonaggressive victims (7.4% of the sample), 38 aggressive victims (17.7% of the sample), 72 normative contrast children (33.5% of the sample), and 76 unclassified children (35.3% of the sample). For relational victimization and aggression, this procedure resulted in identification of 14 non-victimized aggressors (6.4% of the sample), 19 nonaggressive victims (8.6% of the sample), 36 aggressive victims (16.4% of the sample), 72 normative contrast children (32.7% of the sample), and 79 unclassified children (35.9% of the sample).

We conducted one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) to verify the differences in our groups. For analysis with the physical victimization/aggression group as the predictor and the composite physical victimization score as the outcome there was a significant group effect, F (3, 135) = 112.75, p < .001. Post hoc analyses (Bonferonni) revealed that the nonvictimized aggressors and the normative contrast groups had lower physical victimization scores than both aggressive and nonaggressive victims ( ps < .001). There also was a significant group effect for the composite physical aggression score, F (3, 135) = 90.32, p < .001. Post hoc analyses (Bonferroni) revealed that the nonvictimized aggressor and aggressive victim groups had higher physical aggression scores than the nonaggressive victim and normative contrast groups ( ps < .001).

We repeated these analyses for the relational victimization/ aggression group. There was a significant group effect on the composite measure of relational victimization, F (3, 137) = 82.19, p < .001. Post hoc analyses (Bonferonni) revealed that the nonvictimized aggressors and the normative contrast groups had lower relational victimization scores than both aggressive and nonaggressive victims ( ps < .001). There also was a significant group effect for the composite relational aggression score, F (3, 137) = 100.41, p < .001. Post hoc analyses (Bonferroni) revealed that the nonvictimized aggressor and aggressive victim groups had higher physical aggression scores than the nonaggressive victim and normative contrast groups ( ps < .001). In addition, aggressive victims had higher composite relational aggression scores than nonvictimized aggressors ( p < .001).

Tests of the central hypotheses

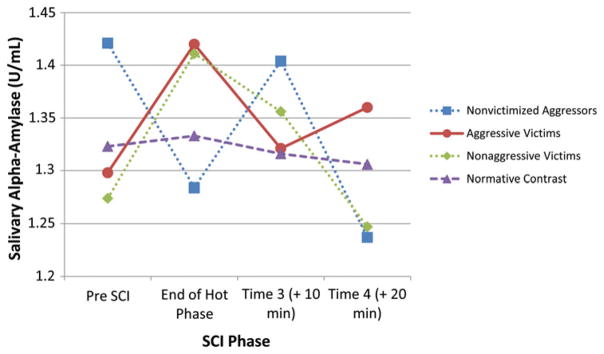

In order to determine whether variations in patterns of victimization and aggression were associated with different physiological responses to a recalled stressor, repeated-measures analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were conducted. In the first set of analyses, physical victimization/aggression group status and sex were predictors, the four physiological responses were outcomes, and controls were time of day, pubertal status, and medication use. For sAA, there was a Group× SCI Phase interaction, Wilk’s λ (9, 294) = 2.37, p < .02, but no significant interaction with sex, and none of the covariates were significant. As seen in Table 2 (top) and Figure 2, both aggressive and nonaggressive victims were reactive to the SCI, nonvictimized aggressors showed a drop in sAA during the height of the SCI, and normative contrast youth remained flat. Univariate ANOVAs with the same controls and pre SCI values as the outcome revealed no differences across victimization/aggression groups, F (3, 125) < 1. When the repeated-measures analysis was replicated with cortisol as the outcome, there was no Group×SCI Phase interaction. However, there was a significant effect for SCI phase and a significant SCI Phase×Time of Day interaction.

Table 2.

Repeated measures analysis of covariance of salivary α-amylase responses in the social competence interview (SCI) as a function of victimization/aggression group and sex, with time of day, pubertal status, and medication usage as covariates

| Source | df | SS | MS | F | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Victimization/Aggression | |||||

|

| |||||

| SCI Phase | 3 | 0.02 | 0.01 | <1 | 0.002 |

| SCI Phase×Time of Day | 3 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 1.47 | 0.012 |

| SCI Phase ×Pubertal Status | 3 | 0.04 | 0.02 | <1 | 0.004 |

| SCI Phase ×Medication | 3 | 0.07 | 0.02 | <1 | 0.006 |

| SCI Phase ×Sex (Male) | 3 | 0.03 | 0.01 | <1 | 0.003 |

| SCI Phase ×Group | 9 | 0.68 | 0.08 | 2.47** | 0.057 |

| SCI Phase ×Group ×Sex | 9 | 0.15 | 0.02 | <1 | 0.013 |

| Error | 369 | 11.35 | 0.03 | ||

|

| |||||

| Relational Victimization/Aggression | |||||

|

| |||||

| SCI Phase | 3 | 0.03 | 0.01 | <1 | 0.003 |

| SCI Phase×Time of Day | 3 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 1.18 | 0.009 |

| SCI Phase ×Pubertal Status | 3 | 0.05 | 0.03 | <1 | 0.005 |

| SCI Phase ×Medication | 3 | 0.06 | 0.02 | <1 | 0.006 |

| SCI Phase ×Sex (Male) | 3 | 0.08 | 0.03 | <1 | 0.008 |

| SCI Phase ×Group | 9 | 0.53 | 0.06 | 2.19* | 0.050 |

| SCI Phase ×Group ×Sex | 9 | 0.21 | 0.02 | <1 | 0.021 |

| Error | 375 | 11.35 | 0.03 | ||

Note: The SCI Phase×Time of Day effects were linear for physical victimization/aggression, F (1, 123) = 3.77, p < .06, and for relational victimization/aggression, F (1, 125) = 3.18, p < .08.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Figure 2.

Overt Physical Victimization/Aggression×Social Competence Interview Phase interaction for transformed values of salivary α-amylase. Time of day, medication usage, and pubertal status were controlled.

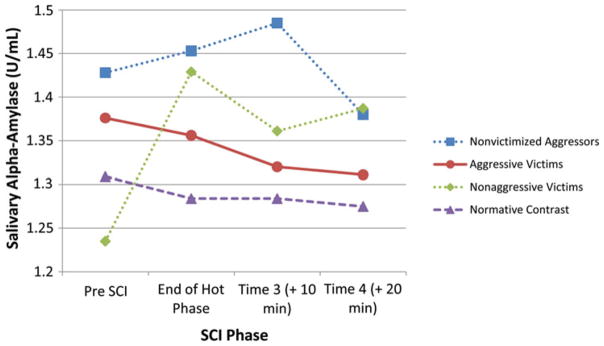

In the second set of analyses, relational victimization/ aggression group status and sex were predictors, the four physiological responses were outcomes, and controls were time of day, pubertal status, and medication use. Similar to the results for physical victimization/aggression, there was a Group×SCI Phase interaction on sAA, Wilk’s λ (9, 299) = 2.12, p < .05, but no significant interaction with sex, and none of the covariates were significant. As seen in Table 2 (bottom) and Figure 3, the pattern of change in sAA during the SCI differed from that seen with the physical victimization/aggression groups. Specifically, nonaggressive victims were the only group reactive to the SCI, and nonvictimized aggressors did not show a drop in sAA during the SCI. As with the physical victimization/aggression groups, there were no pre-SCI differences on sAA, F (3, 127) = 1.24, ns. When the repeated measures analysis was replicated with cortisol as the outcome, there was no Group×SCI Phase interaction. However, there was a significant effect for SCI Phase, and a significant SCI Phase×Time of Day interaction.

Figure 3.

Relational Victimization/Aggression×Social Competence Interview Phase interaction for transformed salivary α-amylase. Time of day, medication usage, and pubertal status were controlled.

Additional analyses

We first conducted additional analyses to determine if discussing a peer victimization event during the SCI affected the pattern of findings. Approximately one-third of the sample discussed a peer victimization event during the Wave 3 SCI, and based on one-way ANOVAs the proportions differed by group status, F (3, 135) = 6.02, p < .001, for physical victimization/ aggression group, and F (3, 137) =3.52, p <.02, for relational victimization/aggression group. The proportion of adolescents in the physical victimization/aggression group who discussed peer victimization during the SCI were as follows: nonvictimized aggressors = 46%, aggressive victims = 42%, nonaggressive victims = 75%, and the normative contrast group = 24%. Post hoc analyses (Bonferroni) revealed that nonaggressive victims and the normative contrast youth differed. Rates for the relational victimization/aggression groups were as follows: nonvictimized aggressors = 36%, aggressive victims = 50%, nonaggressive victims =47%, and the normative contrast group = 22%. Post hoc analyses (Bonferroni) revealed that the aggressive victims and the normative contrast youth differed.

We then reran our significant ANCOVAs covarying for whether or not the adolescent discussed a peer victimization event during the SCI. In both cases (analyses with physical and relational victimization/aggression groups), the Group× SCI Phase interactions remained significant, and there was not an effect for whether or not a peer victimization event was discussed.

Next, we examined whether the extent to which adolescents reported feeling angry, sad, scared, or embarrassed in the situation they described in the SCI differed by group status. The victimization/aggression groups did not differ significantly on any of the rated emotions (Fs < 1.17), which indicated no systematic group differences in reported affect during the SCI.

Finally, we explored differences in threat appraisal by group status. For analyses with the physical victimization/aggression groups, nonvictimized aggressors had lower levels of threat regarding physical harm to themselves and negative evaluation by others relative to aggressive victims ( ps <.05). Further, nonvictimized aggressors had lower levels of threat regarding negative evaluation by others and loss of relationships relative to nonaggressive victims ( ps < .05). Aggressive and nonaggressive victims did not differ on any of the threat subscales. For analyses with relational victimization/ aggression groups, aggressive victims had higher levels of threat relative to the normative contrast group on negative evaluation by others, negative self-evaluation, and loss of relationships. To examine whether these differences in threat appraisals accounted for the observed Group×SCI Phase interaction, we reran our significant ANCOVAs covarying for threat appraisals. Once again, in both cases (analyses with physical and relational victimization/ aggression groups), the Group × SCI Phase interactions remained significant, and thus differences in threat appraisals did not account for differences in patterns of physiological response.

Discussion

This prospective study with a relatively large sample of African American adolescents investigated physiological correlates of peer victimization and aggression groups, using indicators from two biological systems. Three waves of data spanning 2 years were used to classify adolescents into groups of nonvictimized aggressors, aggressive victims, nonaggressive victims, and normative controls. For both the physical victimization and aggression and relational victimization and aggression groups there was a Group×SCI Phase interaction predicting changes in sAA, but no such interaction predicting changes in cortisol. Consistent with our hypothesis, victimization was associated with greater SNS reactivity to the stressor task. However, our hypothesis that aggression would moderate the relation between peer victimization and physiological responses to stress was only confirmed for analyses involving relational victimization and aggression. Our hypotheses regarding cortisol were not confirmed. In the discussion that follows we highlight how our findings mirror work in other literatures, discuss reasons for the differential findings across the two biological systems we investigated, and reiterate the importance of looking at physiological stress responses across biological systems.

Our data indicate that a history of experiencing and responding to both overt and relational victimization by peers over a period of 2 years affects how adolescents react physiologically to stress. The majority of victimized youth in our sample reacted physiologically when describing a stressful event they had experienced recently. In contrast, nonvictimized youth did not show elevations in sAA in response to stress. This suggests that repeated exposure to peer victimization, in this case over a 2-year period spanning the transition into middle school or into high school, may “prime” the body to be reactive to stress. Given that our analyses controlled for time of day, medication use that could affect sAA, and pubertal status, these effects are quite robust. We also found that whether or not the adolescent discussed a peer victimization event during the SCI or the extent to which adolescents reported feeling threatened could not account for the pattern of findings.

Our data are consistent with previous studies with rural youth indicating that chronic stress and elevated levels of risk are associated with higher epinephrine and norepinephrine, and diastolic and systolic blood pressure (Evans, 2003). Further, in a study of African American adolescents, exposure to violence was associated with heightened sympathetic arousal (Wilson, Kliewer, Teasley, Plybon, & Sica, 2002). Our work also mirrors findings from the posttraumatic stress literature that indicates that individuals who have experienced trauma show autonomic reactivity to trauma reminders several years following the trauma experience (Tucker et al., 2007). The victims (both nonaggressive victims and aggressive victims) in our study had significantly higher posttraumatic stress scores than the nonvictimized aggressors or normative contrast youth.

We hypothesized that aggression would moderate the relation between peer victimization and physiological responses, such that aggressive victims would be less physiologically reactive when discussing the stressor during the SCI. This hypothesis was confirmed for analyses involving relational victimization and aggression, but not for analyses with physical victimization and aggression. Although our data on threat appraisals statistically could not account for the findings, the data do provide some clues regarding cognitive and affective processes that may underlie differential physiological response patterns. For the analyses with physical victimization/aggression groups, differences in threat appraisals mirrored different patterns of reactivity in the four groups, nonvictimized aggressors, and normative contrast youth, who had the lowest levels of threat, also were the least reactive; aggressive and nonaggressive victims, who had the highest levels of threat, were the most reactive. This was most true for threat of negative evaluation by others, a salient concern among adolescents but particularly in the urban culture that characterized our sample (Anderson, 2000). It is interesting that the aggressive victims in our relational victimization/aggression grouping had higher levels of relational aggression than any other group, including the nonvictimized aggressors. This may account for the observed moderation effect and suggests that a particular level of aggression—a threshold—might be necessary in order to see a moderator effect of aggression on the victimization–physiological response relation.

Consistent with some previous literature (Gordis et al., 2006; Moss et al., 1995; van Goozen et al., 1998), youth in our sample who were nonvictimized aggressors were not reactive to the stressor. In the analysis with physical victimization and aggression these youth showed a decrease in sAA during the task, whereas other groups of youth either showed no response (normative contrast group) or demonstrated increases (both groups of victimized youth).

With respect to cortisol, adolescents were not physically reactive to the task, perhaps because it was not evaluative (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004; Yim, Granger, & Quas, 2010). It should be noted that several recent studies (Hamilton, Newman, Delville, & Delville, 2008; Kobak, Zajac, & Levine, 2009; Rudolph et al., 2010) found that participants’ cortisol did not reliably increase, even when a task presumably was stressful. Rudolph et al. (2010), as well as other researchers (Stroud et al., 2009) have not found increases in cortisol in response to peer rejection assessed in the lab.

Clinical implications

Finally, our data indicate the importance of examining physiological stress responses across multiple biological systems. As the HPA axis and SNS serve different biological functions, researching multiple systems provides greater understanding of the impact of victimization and aggression on physical and emotional health. Biological systems can provide a more comprehensive picture of current and future psychopathology than assessing behavior alone (Bauer et al., 2002). Studying a child’s physiological reactions to stress can give insight into behavior regulation, help identify children for prevention/intervention, and serve as markers of treatment progress. As evidenced in the current study, if only one of the physiological markers was examined, conclusions about the physiological impact of victimization and aggression may have been inaccurate. Further, physiological reactions to stress might be conceptualized as mediators or moderators of interventions for victimized youths. For example, interventions that build youths’ emotion regulation and coping skills might, in turn, alter physiological responses to stress. Alternatively, youths with unusual patterns of physiological reactivity to stress might be less (or more) likely to benefit from interventions. Examining physiological reactivity as a moderator of intervention effects can help scientists to further understand for whom interventions work.

Because many aggressive youths are also victimized, it is important to consider how victimization experiences may alter associations between physiological reactivity and aggression and thus help to explain inconsistent findings in the literature. Specifically, prior work by Gordis and colleagues suggests that high SNS activity is protective against aggression, and future work might consider whether and how this finding is in fact applicable to victimized youths. Our study findings suggest that for physical aggression and victimization, SNS reactivity is comparable for both aggressive and nonaggressive victims. That is, victimization status appears to be a marker for SNS reactivity, regardless of youths’ status as aggressive or nonaggressive. This study provides a preliminary empirical foundation for such work.

Study limitations and future directions

Although our study was longitudinal, we relied on reports of victimization and aggressive from one source: the adolescent. Having additional data from parents and/or teachers might increase the confidence in the findings. We also elected to form our victimization–aggression groups using a modification of a procedure used by Schwartz (2000). We felt this provided the best opportunity to capture chronic victimization experiences in our sample, as well as to create a normative constrast group that was truly low in both victimization and aggression. However, an alternative might have been to use latent profile analyses to form our groups. Although we examined both sAA and cortisol responses to stress, we did not look at how these systems interacted as other researchers have suggested. Despite these limitations, this study was the first to prospectively examine associations between patterns of victimization and aggression and physiological responses.

Future work might focus on understanding the underlying reasons for observed differences in patterns of physiological response to peer victimization and other forms of stress. A focus on the coping process including affect, appraisals, and goals, might be an especially promising direction. Although threat appraisal was associated with both aggression/victimization status and physiological reactivity, threat appraisal did not explain the associations between group status and physiological outcomes. Thus, although threat appraisal is clearly important, future work must uncover additional stress and coping processes that explain why victims show greater SNS reactivity. More research is needed to understand the social ecology surrounding peer victimization and its effects reactivity to a laboratory task.

References

- Anderson E. Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. New York: Norton; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Annie E. Casey Foundation. Kids count. Baltimore, MD: Author; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer AM, Quas JA, Boyce WT. Associations between physiological reactivity and children’s behavior: Advantages of a multi-system approach. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2002;23:102–113. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200204000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björkqvist K, Lagerspetz KMJ, Kaukianinen A. Do girls manipulate and boys fight? Developmental trends in regard to direct and indirect aggression. Aggressive Behavior. 1991;18:117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Matthews KA, Salomon K, Ewart CK. Cardiovascular reactivity during social and nonsocial stressors: Do children’s personal goals and expressive skills matter? Health Psychology. 2002;21:16–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR. Engagement in gender normative versus nonnormative forms of aggression: Links to social–psychological adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:610–617. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social–psychological adjustment. Child Development. 1995;66:710–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Children’s treatment by peers: Victims of relational and overt aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:367–380. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Ostrov JM, Werner NE. A longitudinal study of relational aggression, physical aggression, and children’s social–psychological adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:131–142. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Lee CH. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2005. US Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Dettling AC, Gunnar MR, Donzella B. Cortisol levels of young children in full-day childcare centers: Relations with age and temperament. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1999;24:519–536. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(99)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:355–391. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkes R, Kemp J, Baum K. Indicators of school crime and safety: 2008 (NCES 2009-022/NCJ 226343) Washington, DC: US Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, and US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW. A multimethodological analysis of cumulative risk and allostatic load among rural children. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:924–933. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.5.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart CK, Jorgensen RS, Suchday S, Chen E, Matthews KA. Measuring stress resilience and coping in vulnerable youth: The Social Competence Interview. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:339–352. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart CK, Kolodner KB. Social competence interview for assessing physiological reactivity in adolescents. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1991;53:289–304. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199105000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Kung EM, White KS, Valois R. The structure of self-reported aggression, drug use, and delinquent behaviors during early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:282–292. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JL, Sollie DL, Morrow KB. Social networks in male and female adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1986;6:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gavin L, Furman W. Age difference in adolescents’ perceptions of their peer groups. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:827–834. [Google Scholar]

- Gordis EB, Granger DA, Susman EJ, Trickett PK. Asymmetry between salivary cortisol and α-amylase reactivity to stress: Relation to aggressive behavior in adolescents. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:976–987. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordis EB, Granger DA, Susman EJ, Trickett PK. Salivary alpha amylase cortisol asymmetry in maltreated youth. Hormones & Behaviors. 2008;53:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger DA, Kivlighan KT, el-Sheikh M, Gordis E, Stroud LR. Salivary α-amylase in biobehavioral research: Recent developments and applications. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1098:122–144. doi: 10.1196/annals.1384.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger DA, Kivlighan KT, Fortunato C, Harmon AG, Hibel LC, Schwartz EB, et al. Integration of salivary biomarkers into developmental and behaviorally-oriented research: Problems and solutions for collecting specimens. Physiology & Behavior. 2007;92:583–590. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gump BB, Matthews KA. Do background stressors influence reactivity to and recovery from acute stressors. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1999;29:469–494. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton LD, Newman ML, Delville CL, Delville Y. Physiological stress response of young adults exposed to bullying during adolescence. Physiology & Behavior. 2008;95:617–624. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanish L, Guerra N. Aggressive victims, passive victims, and bullies: Developmental continuity or developmental change? Merrill–Palmer Quarterly. 2004;50:17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, Nansel T, Eitel P, Crump AD, Saylor K, Yu K, et al. Bullies, victims, and bully/victims: Distinct groups of at-risk youth. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2001;21:29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hazler RJ, Carney JV, Granger DA. Integrating biological mesures into the study of bullying. Journal of Counseling and Development. 2006;84:298–307. [Google Scholar]

- Henington C, Hughes JN, Cavell TA, Thompson B. The role of relational aggression in identifying aggressive boys and girls. Journal of School Psychology. 1998;36:457–477. [Google Scholar]

- Hibel LC, Granger DA, Kivlighan KT, Blair C. Individual differences in salivary cortisol: Association with common over-the-counter and prescription medication status in infants and their mothers. Hormones & Behavior. 2006;50:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibel LC, Granger DA, Cicchetti D, Rogosch F. Salivary biomarker levels and diurnal variation: Associations with medications prescribed to control children’s problem behavior. Child Development. 2007;78:923–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Graham S, Schuster MA. Bullying among young adolescents: The strong, the weak, and the troubled. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1231–1237. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivlighan KT, Granger DA. Salivary α-amylase response to competition: Relation to gender, previous experience, and attitudes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W. Violence exposure and cortisol responses in urban youth. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;13:109–120. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1302_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Sullivan TN. Community violence exposure, threat appraisal, and adjustment in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:860–873. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimes-Dougan B, Hastings PD, Granger DA, Usher BA, Zahn-Waxler C. Adrenocortical activity in at-risk and normally developing adolescents: Individual differences in salivary cortisol basal levels, diurnal variation, and responses to social challenges. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:695–719. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak R, Zajac K, Levine S. Cortisol and antisocial behavior in early adolescence: The role of gender in an economically disadvantaged sample. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:579–591. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe LD, Kann L, Collins JL. Overview of the youth risk behavior surveillance system. Public Health Reports. 1993;20S:2–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Henrich CC, Jones SM, Hawley PH. Disentangling the “whys” from the “whats” of aggressive behavior. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2003;27:122–133. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Seeman T. Protective and damaging effects of mediators of stress: Elaborating and testing the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;896:30–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HB, Vanyukov MM, Martin CS. Salivary cortisol repsonses and the risk of substance abuse in prepubertal boys. Biological Psychiatry. 1995;38:547–555. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00382-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nater UM, Rohleder N. Salivary alpha-amylase as a non-invasive biomarker for the sympathetic nervous system: Current state of research. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:486–496. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan J. City ninth most dangerous. The Richmond Times Dispatch. 2004 Nov 23;:B3. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz J, Raine A. Heart rate level and antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:154–162. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200402000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrov JM. Deception and subtypes of aggression during early childhood. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2006;93:322–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajer K, Gardner W, Rubin RT, Perel J, Neal S. Decreased cortisol levels in adolescent girls with conduct disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:297–302. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry DG, Kusel SJ, Perry LC. Victims of peer aggression. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:807–814. [Google Scholar]

- Perry DG, Perry LC, Kennedy E. Conflict and the development of antisocial behavior. In: Shantz CU, Hartup WW, editors. Conflict in child and adolescent development. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1992. pp. 301–329. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1988;17:117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A. Autonomimc nervous system factors underlying disinhibited, antisocial, and violent behavior. Biosocial perspectives and treatment implications. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1996;794:46–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb32508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid-Quinones K, Kliewer W, Shields BJ, Goodman K, Ray MH, Wheat E. Cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to witnessed versus experienced violence. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81:51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Troop-Gordon W, Granger DA. Peer victimization and aggression: Moderation by individual differences in salivary cortiol and alpha-amylase. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:843–856. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9412-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa A, Raine A. Psychophysiology of anger and violent behavior. Anger, Aggression, and Violence. 1997;20:375–394. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70318-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D. Subtypes of victims and aggressors in children’s peer groups. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:181–192. doi: 10.1023/a:1005174831561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Dodge KA, Pettit GP, Bates JE. The early socialization of aggressive victims of bullying. Child Development. 1997;68:665–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer VC. The psychosocial worlds of the adolescent. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Shoal GD, Giancola PR, Kirillova GP. Salivary cortisol, personality, and aggressive behavior in adolescent boys: A 5-year longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:1101–1184. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000070246.24125.6D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirtcliff EA, Granger DA, Booth A, Johnson D. Low salivary cortisol levels and externalizing behavior problems in youth. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:167–184. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg ME, Olweus D, Endresen IM. Bullies and victims at school: Are they the same pupils? British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2007;77:441–464. doi: 10.1348/000709906X105689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud LR, Foster E, Papandonatos G, Handwerger K, Granger DA, Kivlighan KT, et al. Stress response and the adolescent transition: Performance versus social rejection stress. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:47–68. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TN, Farrell AD, Kliewer W. Peer victimization in early adolescence: Association between physical and relational victimization and drug use, aggression, and delinquent behaviors among urban middle school students. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:119–137. doi: 10.1017/S095457940606007X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Lerner JS, Sage RM, Lehman BJ, Seeman TE. Early environment, emotions, responses to stress, and health. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:1365–1393. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker PM, Pfefferbaum B, North CS, Kent A, Burgin CE, Parker DE, et al. Physiologic reactivity despite emotional resilience several years after direct exposure to terrorism. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:230–235. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tukey JW. Exploratory data analysis. Ontario: Addison–Wesley; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood MK. Social aggression among girls. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt T, Duku E, Decatanzaro D, Macmillan H, Muir C, Schmidt LA. Variation in hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis activity among bullied and non-bullied children. Aggressive Behavior. 2008;34:294–305. doi: 10.1002/ab.20240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Wal MF, de Wit CAM, Hirasing RA. Psychosocial health among young victims and offenders of direct and indirect bullying. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1312–1317. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Goozen SHM, Matthys W, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Buitelaar JK, van Engeland H. Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and autonomic nervous system activity in disruptive children and matched controls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:1438–1445. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200011000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Goozen SHM, Matthys W, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gispen-de Wied C, Wiegant VM, van Engeland H. Salivary cortisol and cardiovascular activity during stress in oppositional-defiant disorder boys and normal controls. Biological Psychiatry. 1998;43:531–539. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(97)00253-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra R, Lindenberg S, Oldehinkle AJ, De Winter AF, Vehulst FC, Ormel J. Bullying and victimization in elementary schools: A comparison of bullies, victims, bully/victims, and uninvolved preadolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:672–682. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson MW, Fischer KW, Andreas JB. Pathways to aggression in children and adolescents. Harvard Educational Review. 2004;74:404–430. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DK, Kliewer W, Teasley N, Plybon LE, Sica DA. Violence exposure, catecholamine excretion, and blood pressure non-dipping status in African American male versus female adolescents. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64:906–915. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000024234.11538.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim I, Granger DA, Quas JA. Children’s and adults’ salivary alpha-amylase responses to a laboratory stressor and to verbal recall of the stressor. Developmental Psychobiology. 2010;52:598–602. doi: 10.1002/dev.20453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]