Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Frailty is a state of vulnerability to diverse stressors. We assessed the impact of frailty on outcomes after discharge in older surgical patients.

METHODS:

We prospectively followed patients 65 years of age or older who underwent emergency abdominal surgery at either of 2 tertiary care centres and who needed assistance with fewer than 3 activities of daily living. Preadmission frailty was defined according to the Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale as “well” (score 1 or 2), “vulnerable” (score 3 or 4) or “frail” (score 5 or 6). We assessed composite end points of 30-day and 6-month all-cause readmission or death by multivariable logistic regression.

RESULTS:

Of 308 patients (median age 75 [range 65–94] yr, median Clinical Frailty Score 3 [range 1–6]), 168 (54.5%) were classified as vulnerable and 68 (22.1%) as frail. Ten (4.2%) of those classified as vulnerable or frail received a geriatric consultation. At 30 days after discharge, the proportions of patients who were readmitted or had died were greater among vulnerable patients (n = 27 [16.1%]; adjusted odds ratio [OR] 4.60, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.29–16.45) and frail patients (n = 12 [17.6%]; adjusted OR 4.51, 95% CI 1.13–17.94) than among patients who were well (n = 3 [4.2%]). By 6 months, the degree of frailty independently and dose-dependently predicted readmission or death: 56 (33.3%) of the vulnerable patients (adjusted OR 2.15, 95% CI 1.01–4.55) and 37 (54.4%) of the frail patients (adjusted OR 3.27, 95% CI 1.32–8.12) were readmitted or had died, compared with 11 (15.3%) of the patients who were well.

INTERPRETATION:

Vulnerability and frailty were prevalent in older patients undergoing surgery and unlikely to trigger specialized geriatric assessment, yet remained independently associated with greater risk of readmission for as long as 6 months after discharge. Therefore, the degree of frailty has important prognostic value for readmission.

Trial registration for primary study

ClinicalTrials.gov, no. NCT02233153

Readmissions are expensive,1 have been considered an important quality indicator for surgical care2 and are highest after abdominal procedures.1 Older patients are increasingly being admitted with acute surgical conditions3 and have a higher risk of readmission.4

Frailty is more prevalent among, although it is not limited to, older patients.5 It is widely accepted that frailty is a multifactorial state that is marked by vulnerability to internal and external stress6 and that may change over time.6,7 Frailty is a known risk factor for complications,8–11 prolonged hospital stay8,12 and adverse discharge disposition.8,11 Furthermore, degree of frailty shows a dose–response relation to mortality in both surgical13 and critically ill5 patients. However, the impact of frailty on readmission after surgery in older patients has rarely been assessed.

Measuring frailty in hospital using a rapid tool may be especially valuable for surgeons who treat older patients whose risk of poor outcomes is not captured by their age alone.6,14 Perhaps the greatest opportunity lies in increasing recognition of patients who are at high risk without noticeable disability, which could enable early intervention.6 The Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale15 is a previously validated 9-point global subjective assessment of comorbidity and function that does not require specialized training or entail extensive assessment; 16 it has surpassed more complex frailty assessments in predicting readmission and mortality.17,18

Very few studies have examined the risk associated with frailty for subsequent health care utilization in any surgical group.18 Therefore, we assessed the impact of preadmission frailty on 30-day and 6-month readmission or death in older patients undergoing emergency abdominal surgery.

Methods

Population and data collection

We report here a substudy of patients who were prospectively enrolled during the pre-implementation phase of the Elder-friendly Approaches to the Surgical Environment (EASE) study (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT02233153).19 We included patients aged 65 years or older who survived emergency abdominal surgery at 2 tertiary care hospitals in Canada (University of Alberta Hospital, Edmonton, and Foothills Medical Centre, Calgary) between January 2014 and September 2015. Patients who required assistance with 3 or more activities of daily living, underwent palliative or trauma surgery, or were transferred from another ward or hospital were excluded. Baseline and demographic characteristics were collected by trained research assistants through chart review and patient interviews in the hospital or at follow-up. We calculated the Charlson Comorbidity Index for each patient; this index has previously been validated for acutely ill older patients.20

Main independent variable

We assessed frailty using the revised Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale.15 Trained research assistants determined frailty status in the 2 weeks preceding index admission by interviewing patients (or their surrogates) shortly after admission or by reviewing medical charts. Degree of frailty was defined as very fit to well (termed “well,” for brevity; score 1 or 2), managing well to vulnerable (termed “vulnerable;” score 3 or 4) or mildly to moderately frail (termed “frail;” score 5 or 6). “Very fit” refers to people who are very active and energetic; “well” indicates those who are occasionally active; “managing well” indicates those who are physically inactive beyond routine walking; “vulnerable” indicates those with comorbidity and limited activity, but without disability; “mild frailty” indicates dependence in 1 or more instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., food preparation or housework); and “moderate frailty” indicates dependence in 1 or 2 basic activities of daily living (e.g., dressing, bathing).16 Patients with severe or very severe frailty, indicating complete dependence in 3 or more activities of daily living, and terminally ill patients (score ≥ 7) were ineligible for the EASE study.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was composite all-cause readmission or death at 30 days and 6 months after discharge, which accounts for the competing risk of death. Readmission and mortality data were collected from a province-wide electronic medical records database. Readmission was defined as acute care admission after the initial surgery, excluding transfers for rehabilitation or convalescence.

Statistical analysis

We determined descriptive statistics, calculating proportions, means and medians. We identified some potential confounders a priori on the basis of existing literature and clinical importance (age, sex and type of surgery). Additional potential confounders were identified in univariable analyses that compared baseline covariables with readmission or death and with frailty, with a predefined cut-off of p < 0.2. We used Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and t tests or one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables (see Table 1 for the variables included). Trends for covariables and degree of frailty are reported.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of older patients discharged from hospital after emergency abdominal surgery

| Characteristic | Preadmission level of frailty*; no. (%) of patients† | p value‡ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well n = 72 |

Vulnerable n = 168 |

Frail n = 68 |

||

| Age, yr, mean ± SD | 73.9 ± 7.0 | 75.2 ± 6.7 | 79.9 ± 9.2 | < 0.001 |

| Sex, female | 30 (41.7) | 75 (44.6) | 35 (51.5) | 0.2 |

| Ethnicity, white | 57 (79.2) | 122 (72.6) | 52 (76.5) | 0.7 |

| Marital status, married or common-law§ | 52 (72.2) | 122 (72.6) | 37 (54.4) | 0.03 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR)§ | 0 (0–1) | 1 (0–2) | 2 (1–3) | < 0.001 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 26 ± 4.5 | 27.6 ± 6.4 | 26.9 ± 6.5 | 0.4 |

| No. of admission medications, mean ± SD | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 |

| Laboratory results in normal range on admission | ||||

| Hemoglobin§ | 57 (79.2) | 115 (68.5) | 37 (54.4) | 0.003 |

| Sodium | 60 (83.3) | 138 (82.1) | 50 (73.5) | 0.1 |

| Potassium§ | 64 (88.9) | 133 (79.2) | 57 (83.8) | 0.3 |

| Creatinine§ | 61 (84.7) | 113 (67.3) | 36 (52.9) | < 0.001 |

| Type of initial surgery | 0.01 | |||

| Colon | 7 (9.7) | 25 (14.9) | 11 (16.2) | |

| Small intestine | 19 (26.4) | 44 (26.2) | 24 (35.3) | |

| Hernia | 10 (13.9) | 23 (13.7) | 9 (13.2) | |

| Open cholecystectomy–appendectomy | 10 (13.9) | 9 (5.4) | 4 (5.9) | |

| Closed cholecystectomy–appendectomy | 23 (31.9) | 52 (31.0) | 11 (16.2) | |

| Other | 3 (4.2) | 15 (8.9) | 9 (13.2) | |

| ASA class, median (IQR)§ | 2 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 3 (3–4) | < 0.001 |

| Creation of ostomy§ | 3 (4.2) | 16 (9.5) | 9 (13.2) | 0.06 |

| Recovery on ward after initial surgery§ | 68 (94.4) | 153 (91.1) | 48 (70.6) | < 0.001 |

| Total no. of consultations, median (IQR)§ | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 1 (0–2) | < 0.001 |

| Geriatric consultation | 1 (1.4) | 3 (1.8) | 7 (10.3) | 0.005 |

| Postoperative use of total parenteral nutrition§ | 14 (19.4) | 33 (19.6) | 21 (30.9) | 0.1 |

| Postoperative use of Foley catheter§ | 41 (56.9) | 111 (66.1) | 51 (75.0) | 0.02 |

| Length of stay, d, median (IQR)§ | 7 (4–11) | 9 (6–12) | 13 (7.5–27.5) | < 0.001 |

| Discharge disposition§ | < 0.001 | |||

| Home, living independently | 63 (87.5) | 121 (72.0) | 24 (35.3) | |

| Home, with support, or lodge | 7 (9.7) | 33 (19.6) | 17 (25.0) | |

| Rehabilitation facility or another hospital | 2 (2.8) | 11 (6.5) | 24 (35.3) | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 0 (0) | 2 (1.2) | 3 (4.4) | |

Note: ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists, BMI = body mass index, IQR = interquartile range, SD = standard deviation.

Level of frailty based on Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale.15

Except where indicated otherwise.

Based on χ2 tests of trend using linear regression for continuous variables, score test of trend of odds for binary variables and Wilcoxon-type test of trend for categorical variables.

Variables identified as potential confounders in the univariable analyses.

The following additional variables, for which data are not shown, were also included in the univariable analyses: current smoking status, vital signs on admission, blood glucose level and white blood cell count on admission, and major surgical complication.

We then developed multivariable logistic regression models using a standard approach21 to calculate the odds of readmission or death. Patients who were readmitted or who died were considered to have had an event and were included in the numerator to account for the competing risk of death. Age, sex and type of surgery were forced into all models. Identified potential confounders were then sequentially entered into the model and retained if they met statistical criteria for confounding (potential confounder p < 0.1 or > 10% change in the frailty β-coefficient upon inclusion). We chose the most parsimonious models, allowing as many as 6 variables at 30 days and 7 variables at 6 months. Model fit was judged using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, and accuracy was judged using the C statistic. We conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the relation of interest per 1-point increase in the Clinical Frailty Scale and the additional prognostic value of increasing age and American Society of Anesthesiologists classification (https://www.asahq.org/resources/clinical-information/asa-physical-status-classification-system). We also conducted a post hoc sensitivity analysis excluding patients who underwent cancer surgery. We considered the Clinical Frailty Scale as a dichotomized variable, applying a well-balanced cut-off score of 4 (rather than 5, as used previously5,22,23), because our cohort excluded patients with scores of 7 or higher. Finally, we disaggregated composite outcomes to identify whether readmission or death was driving the relation.

Statistical significance was defined on the basis of 2-tailed p < 0.05. All analyses were conducted with Stata 14 software (StataCorp LP).

Ethics approval

The University of Alberta Research Ethics Board (Pro00047180) and the University of Calgary Research Ethics Board (REB140729) approved the study procedures.

Results

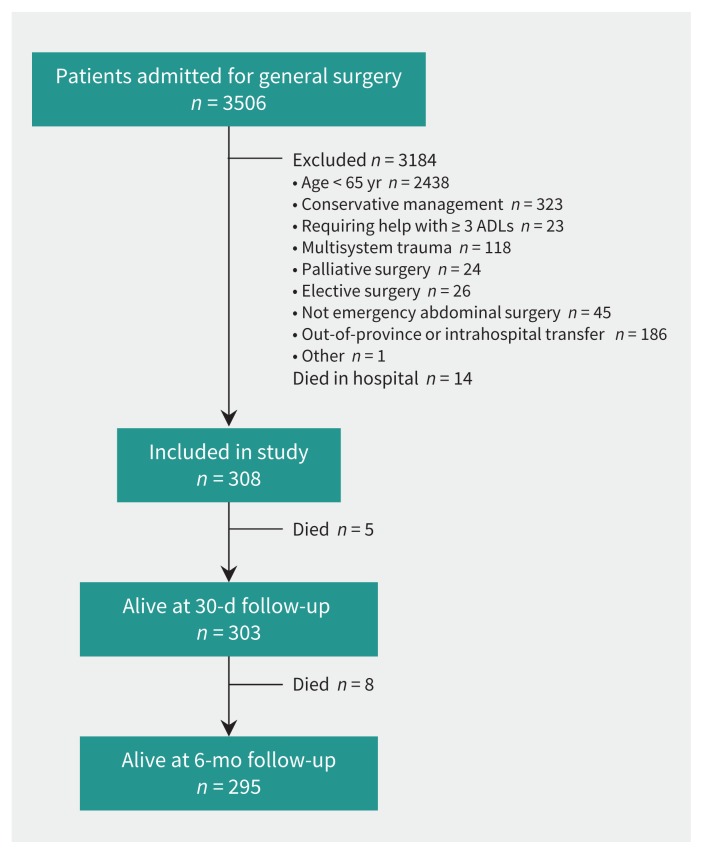

Of 3506 patients screened, most were excluded because of age younger than 65, conservative management or transfer (Figure 1). We enrolled 322 patients and retrieved readmission or mortality data for all patients. Fourteen of the patients died before discharge and were thus excluded from the analyses (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Selection of study patients. ADLs = activities of daily living.

Cohort characteristics

The median age was 75 (range 65–94) years, and 140 (45.4%) of the 308 patients were women. The median score on the Clinical Frailty Scale was 3 (range 1–6): 15 (4.9%) of the patients were “very fit” (score = 1), 57 (18.5%) were “well” (score = 2), 108 (35.1%) were “managing well” (score = 3), 60 (19.5%) were “vulnerable” (score = 4), 39 (12.7%) had “mild frailty” (score = 5), and 29 (9.4%) had “moderate frailty” (score = 6). Before the index admission, 228 (74.0%) of the patients had been living at home independently, 62 (20.1%) had been living at home with assistance, 16 (5.2%) had been residing in a nursing home, and 2 (0.6%) had other living arrangements. The mean Charlson Comorbidity Index was 1.1 (standard deviation 1.2), and nearly all (292 [94.8%]) of the patients underwent a single surgery during their admission; 14 patients (4.5%) required a second surgery, and 2 (0.6%) required more than 2 procedures. Patients underwent the following types of surgery: 109 (35.4%) had cholecystectomy or appendectomy, 87 (28.2%) had small intestinal surgery, 43 (14.0%) had colon surgery, 42 (13.6%) had hernia repair, and 27 (8.8%) had some other type of abdominal surgery.

Prevalence and degree of frailty

Seventy-two (23.4%) of the patients were classified as well (score 1 or 2), 168 (54.5%) as vulnerable (score 3 or 4), and 68 (22.1%) as frail (score 5 or 6) (Table 1). The patients classified as vulnerable or frail were older, had a higher number of comorbidities and medications, and more often presented with abnormal serum hemoglobin and creatinine levels than patients classified as well (Table 1).

At surgery, patients classified as frail were more likely than those classified as well or vulnerable to undergo a laparoscopic (closed) approach for cholecystectomy or appendectomy; if they had intestinal surgery, they were more likely to receive an ostomy (Table 1). Patients classified as vulnerable or frail scored a median of 3 on the American Society of Anesthesiologists classification (interquartile range [IQR] 2–3 and 3–4, respectively), compared with 2 (IQR 2–3) for patients classified as well (Table 1). Although the American Society of Anesthesiologists classification was statistically different for different levels of frailty, the median and mode were the same for patients classified as vulnerable or frail (data not shown). Patients classified as frail were more likely to require postoperative intensive care or close observation and to stay in hospital longer and were less likely to be discharged home independently (Table 1). Although patients classified as vulnerable or frail more often underwent a geriatric assessment than patients classified as well, overall only 4.2% (10/236) of the former group were assessed by a geriatrician.

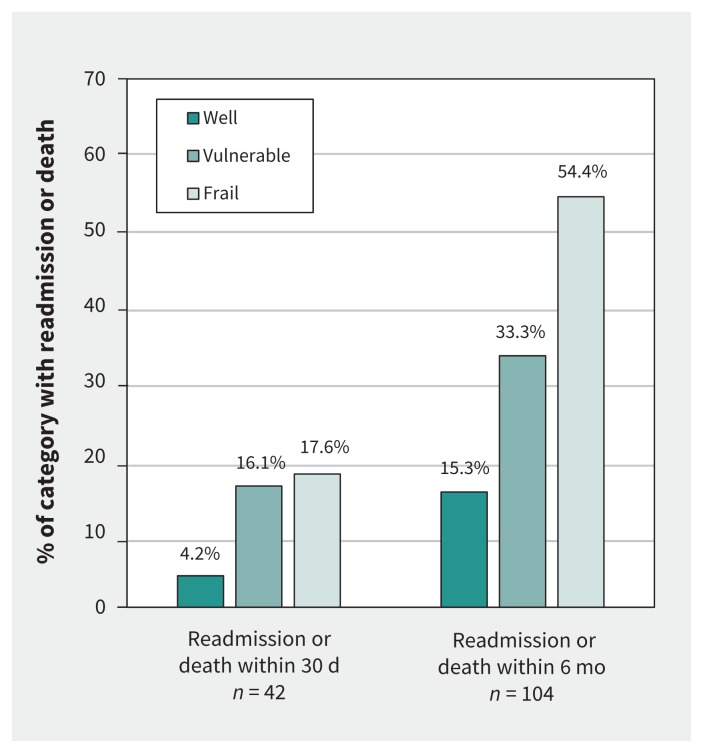

Thirty-day readmission or death

Within 30 days after discharge, 42 (13.6%) of the patients were readmitted or had died. These outcomes occurred in 27 (16.1%) of those classified as vulnerable and 12 (17.6%) of those classified as frail, but only 3 (4.2%) of those classified as well (p = 0.02; Figure 2, Table 2). After adjustment for age, sex, type of surgery, abnormal hemoglobin level and postoperative use of total parenteral nutrition, vulnerable status remained associated with 30-day readmission or death (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 4.60, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.29–16.45), as did frail status (adjusted OR 4.51, 95% CI 1.13–17.94; C statistic 0.75, 95% CI 0.67–0.83) (Table 2).

Figure 2:

Relation between preadmission frailty and outcome after discharge.

Table 2:

Relation between preadmission frailty and outcome after discharge

| Outcome* | Preadmission level of frailty† | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Well n = 72 |

Vulnerable n = 168 |

Frail n = 68 |

|

| 30-day readmission or death‡ | |||

| No. (%) of patients | 3 (4.2) | 27 (16.1) | 12 (17.6) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 4.40 (1.29–15.02) | 4.93 (1.33–18.33) |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 4.60 (1.29–16.45) | 4.51 (1.13–17.94) |

| 30-day readmission‡ | |||

| No. (%) of patients | 3 (4.2) | 26 (15.5) | 11 (16.2) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 4.21 (1.23–14.49) | 4.44 (1.18–16.68) |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 4.23 (1.20–14.97) | 3.97 (1.00–15.78) |

| 6-month readmission or death§ | |||

| No. (%) of patients | 11 (15.3) | 56 (33.3) | 37 (54.4) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 2.77 (1.35–5.68) | 6.62 (2.97–14.73) |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 2.15 (1.01–4.55) | 3.27 (1.32–8.12) |

| 6-month readmission§ | |||

| No. (%) of patients | 11 (15.3) | 55 (32.7) | 33 (48.5) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 2.70 (1.32–5.54) | 5.23 (2.35–11.63) |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 2.20 (1.04–4.62) | 3.03 (1.23–7.49) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

Age, sex and type of surgery were forced into all models. Additional variables meeting the statistical criteria for confounding are detailed in separate footnotes for the individual models.

Level of frailty based on Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale.15

For the 30-day model, the following variables met the statistical criteria for confounding: hemoglobin level on admission, postoperative recovery on ward, postoperative use of total parenteral nutrition and Charlson Comorbidity Index. The final 30-day model was adjusted for age, sex, type of surgery, hemoglobin level on admission and postoperative use of total parenteral nutrition.

For the 6-month model, the following variables met the statistical criteria for confounding: creatinine and hemoglobin levels on admission, postoperative use of total parenteral nutrition, intraoperative ostomy creation and Charlson Comorbidity Index. The final 6-month model was adjusted for age, sex, type of surgery, hemoglobin level on admission, intraoperative ostomy creation and the Charlson Comorbidity Index.

Six-month readmission or death

By 6 months after discharge, 104 (33.8%) of the patients were readmitted or had died. These outcomes occurred in 56 (33.3%) of those classified as vulnerable and 37 (54.4%) of those classified as frail, but only 11 (15.3%) of those classified as well (p < 0.001; Figure 2, Table 2). After adjustment for age, sex, type of surgery, abnormal hemoglobin level, Charlson Comorbidity Index and intraoperative ostomy creation, degree of frailty predicted 6-month readmission or death in a dose-dependent manner (for patients classified as vulnerable, adjusted OR 2.15, 95% CI 1.01–4.55; for patients classified as frail, adjusted OR 3.27, 95% CI 1.32–8.12; C statistic 0.75, 95% CI 0.69–0.81; Table 2).

Sensitivity analyses

A 1-point increase in the Clinical Frailty Scale predicted a greater risk of readmission or death, both independently (at 30 d, adjusted OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.03–1.77, C statistic 0.74, 95% CI 0.66–0.81; at 6 mo, adjusted OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.11–1.75, C statistic 0.75, 95% CI 0.69–0.81) and without adjustment (at 30 d, crude C statistic 0.65, 95% CI 0.56–0.73; at 6 mo, crude C statistic 0.68, 95% CI 0.62–0.74). Neither increasing age (at 30 d, adjusted OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.47–1.23; at 6 mo, adjusted OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.68–1.40) nor a 1-point increase in the American Society of Anesthesiologists classification (at 30 d, adjusted OR 1.17, 95% CI 0.69–1.98; at 6 mo, adjusted OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.67–1.49) was associated with readmission or death. A post hoc sensitivity analysis that excluded patients who underwent cancer surgery (n = 22, 7.1%) did not change the positive association between frailty and readmission or death at 30 days or at 6 months (data not shown). Applying a Clinical Frailty Scale cut-off score of 4 yielded similar results to the tertile analyses (at 30 d, adjusted OR 2.42, 95% CI 1.16–5.02; at 6 mo, adjusted OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.25–3.92). Additional models were adjusted for the same confounders included in the final models above. With disaggregation of composite outcomes, we found that readmissions drove the observed associations (Table 2). Patients were most commonly readmitted for gastrointestinal problems, infection or pulmonary disease (at 30 d, 15/40 [37.5%], 8/40 [20.0%] and 5/40 [12.5%], respectively; at 6 mo, 32/99 [32.3%], 19/99 [19.2%] and 11/99 [11.1%], respectively). No patients classified as well had died by 6 months after discharge.

Interpretation

This study had 3 main findings. First, one-third of older patients were readmitted or died within 6 months after discharge following surgery. Second, patients classified as vulnerable or frail were at increased risk of 30-day readmission or death. Third, by 6 months, the degree of frailty predicted, in a dose-dependent manner, increased risk of readmission or death after multivariable adjustment.

Our findings support and expand evidence concerning frailty and readmission. Of 25 studies on frailty assessment for prognosis after cardiac surgery, only 2 used the Clinical Frailty Scale, and none used the scale to predict readmission.13 The handful of prior studies conducted in a surgical setting largely reported adverse prognosis for patients with frailty, but were mostly restricted to specific procedures and short follow-up periods.23–27 Very few studies have assessed a dose–response relation. Among 325 older patients who underwent general surgery, no difference was found in unadjusted 30-day readmission rates between frail and nonfrail patients, where frailty was defined by Clinical Frailty Scale scores of 5 or higher.23 However, in 383 adult kidney transplant recipients, frailty classified by the Fried criteria identified a 60% increased risk of 30-day readmission.24 Furthermore, in a retrospective study of 5627 adults who underwent posterior cervical fusion, each additional point on a frailty-based index conferred a 40% increased risk of 30-day readmission,25 similar to the 35% increase in risk per additional point in the Clinical Frailty Scale observed in our study. For 178 older patients with colorectal cancer, frailty on comprehensive geriatric assessment was associated with 2.5 times higher unadjusted risk of 30-day readmission related to colorectal surgery.26 Similarly, after classification of 72 older patients undergoing colorectal surgery on the basis of 7 frailty traits, 30-day readmission rates rose with increasing frailty from 6% to 29%.27 Among nonsurgical patients, a Clinical Frailty Scale score of 5 or higher independently predicted a threefold risk of 30-day readmission or death among 245 older medical patients17 and a twofold risk of 1-year readmission among 421 critically ill older patients.5

In this study, we overcame several limitations of prior studies by enrolling an older but largely unselected surgical cohort and reporting outcomes that occurred as long as 6 months after discharge. We also carefully assessed confounders, adjusting a priori for age, sex and type of surgery (because these factors have been linked to frailty and readmission) and examining a range of demographic, biological and clinical factors. Moreover, by describing the dose–response relation between degree of frailty and readmission rates, we provide evidence of risk in patients admitted without noticeable disability who had lower Clinical Frailty Scale scores. Although our cohort was relatively small compared with potential nonsurgical or all-aged groups, the patients were admitted to hospital for a wide range of abdominal diseases, which supports the importance of frailty in predicting readmission risk in various illnesses. Thus, the results may be relevant for clinicians or researchers concerned with prognosis in older patients in general.

Several mechanisms may explain the observed relation. Adverse outcomes could result from environmental or behavioural factors, particularly if extreme vulnerability to stressors like surgery28 increases the time of return to physiologic baseline, thereby predisposing frail patients to functional decline29 and reduced self-care capacity.30,31 Social factors may also modulate the adverse effects of frailty, whereby patients of lower socioeconomic status are both more likely to be classified as frail and more likely to be readmitted to hospital.32 Additionally, the inflammatory state associated with postoperative healing may exacerbate the already impaired immune system of frail older patients,33 thereby increasing postoperative infection rates34 or worsening comorbid conditions, leading to readmission. Alternatively, residual confounding may account for some of the risk observed; however, we adjusted for a variety of clinical and biologic markers, as did multiple prior studies of mortality.13,24,25

Limitations

Although this study featured two-centre prospective enrolment, extensive data collection and prolonged follow-up, it was limited by several factors. The findings cannot be generalized to severely frail or terminally ill patients because these groups were excluded. However, we enrolled a diverse cohort and we were more interested in less severely frail patients who are amenable to preventive strategies. Although we did not compare different tools or assess more objective frailty measures, we selected a frailty tool that is easy to use, reliable and predictive of clinically relevant outcomes,16–18 and that has been recommended for use in other surgical populations.13 We did not assess long-term disability or quality of life, which may be of particular importance to clinicians and patients. Lastly, because a dose–response relation was not observed at 30 days, it is possible that our 30-day results were limited by lower event rates or that frailty is more important for long-term than short-term prognosis.

Conclusion

Identifying frailty in surgical patients will help to predict which patients are at high risk of adverse outcomes, thus improving patient and family discussions and targeting patients for enhanced postoperative care. Moreover, the results of this study suggest that poor postoperative prognosis is not limited to the most severely frail patients, but that vulnerable patients without evident disability are also at higher risk of readmission or death after discharge. Further studies are needed to assess the impact and feasibility of interventions in terms of changing frailty status or decreasing risks among frail surgical patients, but current evidence supports the use of well-validated frailty assessments when evaluating risk for adverse postoperative outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs. Fiona Clement, Heather Hanson and Susan Slaughter for continued support of their research and Lindsey M. Warkentin, Ashley Wanamaker, Carrie Le and Hanhmi Huynh for their contributions to data collection for this study.

See related article at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.170902

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Yibo Li and Jenelle Pederson contributed equally as first authors. All of the authors contributed to the design and conduct of the study. Yibo Li and Jenelle Pederson were responsible for data collection and analysis, and drafted the first version of the manuscript. Rachel Khadaroo supervised the study. All of the authors critically reviewed the manuscript, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The Elder-friendly Approaches to the Surgical Environment (EASE) study is funded by the Alberta Innovates Health Solutions Partnership for Research and Innovation in the Health System grant 201300465.

Data sharing: This substudy is based on pre-implementation data for the Elder-friendly Approaches to the Surgical Environment (EASE) study, which is not yet complete. Data can be shared when the main study has been finished and its results published.

Disclaimer: Jayna Holroyd-Leduc is an associate editor for CMAJ and was not involved in the editorial decision-making process for this article.

References

- 1.All-cause readmission to acute care and return to the emergency department. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Readmissions reduction program (HRRP). Baltimore: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2016. Available: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html (accessed 2016 Nov. 8). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Population projections for Canada, provinces and territories: 2009 to 2036. Cat no 91-520-X. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2010. Available: www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-520-x/91-520-x2010001-eng.pdf (accessed 2016 Nov. 8). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holt PJE, Poloniecki JD, Hofman D, et al. Re-interventions, readmissions and discharge destination: modern metrics for the assessment of the quality of care. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2010;39:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagshaw SM, Stelfox HT, McDermid RC, et al. Association between frailty and short- and long-term outcomes among critically ill patients: a multicentre prospective cohort study. CMAJ 2014;186:E95–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rockwood K, Bergman H. FRAILTY: a report from the 3rd joint workshop of IAGG/WHO/SFGG, Athens, January 2012. Can Geriatr J 2012;15:31–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Partridge JSL, Harari D, Dhesi JK. Frailty in the older surgical patient: a review. Age Ageing 2012;41:142–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg 2010;210:901–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dasgupta M, Rolfson DB, Stolee P, et al. Frailty is associated with postoperative complications in older adults with medical problems. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2009;48:78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farhat JS, Velanovich V, Falvo AJ, et al. Are the frail destined to fail? Frailty index as predictor of surgical morbidity and mortality in the elderly. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;72:1526–30, discussion 1530–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joseph B, Pandit V, Zangbar B, et al. Superiority of frailty over age in predicting outcomes among geriatric trauma patients: a prospective analysis. JAMA Surg 2014;149:766–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee DH, Buth KJ, Martin BJ, et al. Frail patients are at increased risk for mortality and prolonged institutional care after cardiac surgery. Circulation 2010; 121:973–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim DH, Kim CA, Placide S, et al. Preoperative frailty assessment and outcomes at 6 months or later in older adults undergoing cardiac surgical procedures: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2016;165:650–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Revenig LM, Canter DJ, Henderson MA, et al. Preoperative quantification of perceptions of surgical frailty. J Surg Res 2015;193:583–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clinical frailty scale. Version 1.2. Halifax: Dalhousie University, Geriatric Medicine Research; 2007–2009. Available: http://geriatricresearch.medicine.dal.ca/pdf/Clinical%20Faily%20Scale.pdf (accessed 2017 Mar. 6). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005;173:489–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belga S, Majumdar SR, Kahlon S, et al. Comparing three different measures of frailty in medical inpatients: multicenter prospective cohort study examining 30-day risk of readmission or death. J Hosp Med 2016;11:556–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritt M, Bollheimer LC, Sieber CC, et al. Prediction of one-year mortality by five different frailty instruments: a comparative study in hospitalized geriatric patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2016;66:66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khadaroo RG, Padwal RS, Wagg AS, et al. Optimizing senior’s surgical care — Elder-friendly Approaches to the Surgical Environment (EASE) study: rationale and objectives. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frenkel WJ, Jongerius EJ, Mandjes-van Uitert MJ, et al. Validation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index in acutely hospitalized elderly adults: a prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:342–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babyak MA. What you see may not be what you get: a brief, nontechnical introduction to overfitting in regression-type models. Psychosom Med 2004; 66:411–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahlon S, Pederson J, Majumdar SR, et al. Association between frailty and 30-day outcomes after discharge from hospital. CMAJ 2015;187:799–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hewitt J, Moug SJ, Middleton M, et al. Older Persons Surgical Outcomes Collaboration. Prevalence of frailty and its association with mortality in general surgery. Am J Surg 2015;209:254–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, et al. Frailty and early hospital readmission after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 2013;13:2091–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medvedev G, Wang C, Cyriac M, et al. Complications, readmissions, and reoperations in posterior cervical fusion. Spine 2016;41:1477–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kristjansson SR, Nesbakken A, Jordhøy MS, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment can predict complications in elderly patients after elective surgery for colorectal cancer: a prospective observational cohort study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2010;76:208–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson TN, Wu DS, Pointer L, et al. Simple frailty score predicts postoperative complications across surgical specialties. Am J Surg 2013;206:544–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fried LP, Hadley EC, Walston JD, et al. From bedside to bench: research agenda for frailty. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ 2005;2005:pe24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gregorevic KJ, Hubbard RE, Lim WK, et al. The clinical frailty scale predicts functional decline and mortality when used by junior medical staff: a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uchmanowicz I, Wleklik M, Gobbens RJJ. Frailty syndrome and self-care ability in elderly patients with heart failure. Clin Interv Aging 2015;10:871–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gazala S, Tul Y, Wagg A, et al. Quality of life and long-term outcomes of octo-and nonagenarians following acute care surgery: a cross sectional study. World J Emerg Surg 2013;8:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gutiérrez-Robledo LM, Avila-Funes JA. How to include the social factor for determining frailty? J Frailty Aging 2012;1:13–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang GC, Casolaro V. Immunologic changes in frail older adults. Transl Med UniSa 2014;9:1–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berlin A, Johanning JM. Intraabdominal infections in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med 2016;32:493–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]