Abstract

Only a small proportion of research-tested interventions translate into broad-scale implementation in real world practice, and when they do, it often takes many years. Partnering with national and regional organizations is one strategies that researchers may apply to speed the translation of interventions into real-world practice. Through these partnerships, researchers can promote and distribute interventions to the audiences they want their interventions to reach. In this paper, we describe five nurse scientists’ programs of research and their partnerships with networks of national, regional, and local organizations, including their initial formative work, activities to engage multi-level network partners, and lessons learned about partnership approaches to speeding broad-scale implementation.

Keywords: Implementation, Research translation, Diffusion of Innovations Theory

Introduction

Only a small proportion of research-tested interventions translate into broad-scale implementation in real-world practice, and when they do, it often takes many years (Stevens & Staley, 2006). The field of implementation science addresses this challenge by identifying strategies to raise awareness of effective interventions and speed their adoption and integration into a range of practice settings (National Institutes of Health, 2016). To further accelerate the translation of effective interventions into practice, a growing number of implementation scientists are recommending that researchers use marketing strategies to distribute and promote their interventions (Dearing, Maibach, & Buller, 2006; Kreuter & Bernhardt, 2009; Maibach, Van Duyn, & Bloodgood, 2006). One of these recommended strategies is for researchers to identify and partner with the national and regional organizations that are already promoting and distributing interventions to the audiences they want their interventions to reach. This underused strategy has potential to accelerate the broad-scale adoption and implementation of nurse-developed interventions. In this article, we describe five nurse scientists’ programs of research and their partnerships with networks of national and regional organizations, including their initial formative work, activities to engage multilevel network partners, and lessons learned about partnership approaches to facilitate broad-scale implementation. The purpose of this paper is to describe how these nurse scientists developed strategies to speed the translation of nurse-developed interventions into practice.

Conceptual Framework

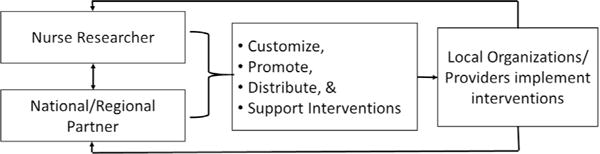

The examples provided in this paper is guided by a conceptual framework that integrates marketing strategies and Diffusion of Innovations Theory (Figure 1; Dearing & Kreuter, 2010; Kreuter & Bernhardt, 2009). The framework describes how nurse researchers partner with national and regional organizations to customize and promote their interventions; distribute interventions to local organizations; and provide support for implementation. Throughout the partnership, nurse researchers and their national and regional partners also learn from local organizations’ experience implementing interventions.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework: National and regional partnerships to accelerate broad-scale implementation.

Partner to Customize and Promote Interventions

The customer or audience is central to marketing science (Storey, Saffitz, & Rimon, 2008). For health interventions, audiences include not only the intended beneficiaries of the intervention (e.g., patients) but also decision makers and staff within the intended adopting organizations (Dearing et al., 2006). The audience may also include key decision makers within national and regional organizations that might promote, distribute, and support the intervention. To facilitate more rapid adoption, an intervention and its promotion need to be tailored or customized to intended audiences’ needs and preferences and to fit within those audiences’ practice contexts. Customization also includes packaging intervention products into attractive and ready-to-use formats and promoting them with messages that address the priorities of each intended audience (Dearing & Kreuter, 2010). Through partnerships with national and regional organizations, nurse researchers have greater access to their intended audiences and therefore opportunities to conduct formative research to understand their needs, preferences, and practice contexts.

Partner to Distribute Interventions

In the absence of partnerships, nurse researchers’ options for distributing their interventions are often limited to presentation at conferences, publication in journals, consultations, or local partnerships. Although several websites disseminate interventions to a national audience, the translation of those interventions into practice has been limited (Hannon et al., 2010). Partnering with national and regional organizations provides an opportunity for nurse researchers to reach a large audience and to distribute their interventions through venues that their intended audiences are already accessing (Kreuter & Bernhardt, 2009). Partnerships further facilitate broad-scale implementation by coupling distribution with training, technical assistance, and other supports for local implementation of the intervention into practice.

Partner to Support Implementation

Audiences often need training on how to implement an intervention and technical assistance to troubleshoot problems as they arise on use (Kreuter & Bernhardt, 2009). Training may take the form of a manual, online videos, or in-person instruction. Technical assistance often is provided online or by telephone. By partnering with national and regional partners, intervention developers have the opportunity to build on existing infrastructure to support local implementation of their interventions more extensively and efficiently than may otherwise be possible.

Partner to Learn from Local Organizations and Providers

Nurse researchers can learn a great deal from local organizations’ and providers’ experience implementing their interventions into practice. Researchers can learn how local organizations adapt interventions, strategies they use to implement and sustain interventions, and contextual factors that influence both adaptation and implementation. Local organizations also are an important source of innovative approaches to intervening (Leeman & Sandelowski, 2012). Nurse researchers can incorporate what they learn from local experience to further improve their interventions and the guidance they provide to support local implementation.

A range of national and regional organizations promote and distribute health-related interventions and provide support for local implementation (Maibach et al., 2006). For example, at the federal government level, the School Health Branch of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention promotes and distributes intervention guidance to state departments of public health and education who then partner with others to promote and distribute that guidance to school systems and support local implementation. The American Cancer Society and Oncology Nursing Society are national nonprofits that promote and distribute interventions through their state and regional offices and provide trainings to support implementation. The Veterans Administration and other national and regional health care systems promote and distribute interventions to their member organizations of local hospitals and other health care providers.

Nurse Researchers’ Experience Engaging National and Regional Partners

The University of North Carolina School of Nursing (UNC SON) has a long history of intervention research and for more than 20 years has been home to a National Institute of Nursing Research-funded training program on Interventions for Preventing and Managing Chronic Illness. Increasingly, the school’s researchers are exploring opportunities to engage national and regional partners as a means to accelerate the translation of new interventions into real-world practice. Later, we summarize how five UNC SON researchers are partnering with national and regional organizations to design interventions so that they are ready for broad-scale implementation within their respective partnering organizations.

Partnering with the Nurse Family Partnership

Dr. Linda Beeber is working with a national nonprofit organization, Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP), to embed evidence-based mental health interventions within its existing systems. Decades of research have shown that depressive symptoms and anxiety can compromise essential mothering interactions needed for an infant or toddler’s optimal cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and social development (Campbell, Morgan-Lopez, Cox, & McLoyd, 2009; Ciciolla, Gerstein, & Crnic, 2014; Turney, 2012). Mothers who are exposed to stressors, such as economic hardship, immigration trauma, discrimination, stigma, social isolation, and chronic threats of violence, are four times more likely to develop function-limiting depressive symptoms and anxiety than mothers who are not exposed to these factors (Feder et al., 2009; Jackson, Brooks-Gunn, Huang, & Glassman, 2000). Yet, these same factors limit mothers’ access to and use of evidence-based treatment for depressive symptoms and anxiety. Bringing interventions into the home solves some of the most daunting barriers to care. In the United States, a gold-standard national home-visiting program is the NFP, a nurse-delivered model that builds maternal self-efficacy and infant–toddler health through strengthening maternal role function, social support, and personal health domains (Olds et al., 2007). Dr. Beeber is leading a team that is integrating effective mental health intervention strategies within the NFP model of care. The effective intervention strategies include depressive symptom and anxiety screening, referral, crisis, and support strategies that are based on evidence from Dr. Beeber’s and others’ randomized clinical trials (Beeber, Schwartz, Holditch-Davis et al., 2014; Beeber, Schwartz, Holditch-Davis et al., 2013). In five state-level pilot studies, Dr. Beeber collaborated with staff from the national, regional, and local offices of NFP to iteratively refine intervention strategies to fit within the delivery systems of NFP. The pilot version now is being adapted for online distribution nationally through National Service Office infrastructure of NFP, which provides ongoing training to NFP nurse home visitors, local agency supervisors, and NFP teams. The national consultants and educators of NFP are currently working with Dr. Beeber’s development team to tailor the online version to the varying needs of communities in 43 U.S. states.

Partnering with Lutheran Services Carolinas

Dr. Mark Toles is partnering with a regional health care system, Lutheran Services Carolinas (LSC), to develop and test his Connect-Home transitional care intervention for use in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). Annually in the United States, nearly 2 million hospitalized older adults transfer to SNFs for short-term rehabilitation (3–4 weeks) before returning home (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 2016). The Connect-Home intervention addresses a serious gap in care of SNF patients—providing evidence-based services that prepare patients and their caregivers to continue care at home and avoid preventable rehospitalization (Toles, Colon-Emeric, Asufu-Adjei, Moreton, & Hanson, 2016). Working in partnership with LSC and a team of researchers in geriatrics, Dr. Toles conducted formative research with SNF staff to design the intervention and completed a successful pilot test in three SNFs (Toles, Colon-Emeric, Naylor, Asafu-Adjei, & Hanson, 2017). As a result of this work, the Connect-Home intervention is exactly tailored to the capacity and needs of LSC. Based on the success of the Connect-Home pilot, Dr. Toles and Lutheran Services America have submitted a proposal to implement the intervention in SNFs in two additional states.

Partnering with Parents as Teachers

Dr. Eric Hodges is working with a national nonprofit organization, Parents as Teachers (PAT), to test his intervention to enhance parents’ feeding responsiveness to their infants to prevent the development of early childhood obesity. PAT is a U.S.-based organization that uses an evidence-based model to develop and deliver parent education curricula for organizations and professionals to support healthy development from birth through early childhood (http://parentsasteachers.org/). A chronic mismatch between a caregiver’s feeding behavior and the infant’s state (feeding in the absence of hunger and/or feeding beyond fullness) is thought to contribute to obesity by undermining the infant’s capacity to self-regulate intake (Disantis, Hodges, Johnson, & Fisher, 2011). Dr. Hodges et al. have developed an intervention that teaches parents American Sign Language signs indicative of hunger, thirst, and satiety, which they in turn teach to their preverbal infant to add to the infant’s repertoire of reflexive and increasingly intentional cues (Hodges, Wasser, Colgan, & Bently, 2016). Dr. Hodges is partnering with the national PAT research and training directors to integrate his intervention within their existing curriculum and systems. In an initial pilot of the integrated approach, he is training parent educators in several North Carolina (NC) counties to deliver the intervention. The feasibility and fidelity of the intervention’s delivery through PAT will be assessed along with infant growth and development outcomes. As PAT affiliates can be found in all 50 states and Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, Switzerland, Australia, and New Zealand, the potential for incorporation and delivery of Dr. Hodges’ intervention into the curricula of PAT could be rapid and widespread.

Partnering with Public Health Systems

Dr. Shawn Kneipp is partnering with public health systems to promote the use of her public health nurse case management intervention. At present, her case management intervention is the only intervention that has empirically demonstrated health and employment gains for socioeconomically disadvantaged women receiving Temporary Assistance for NeedyFamilies (TANF) (Kneipp et al., 2011; Kneipp, Kairalla, & Sheely, 2013). Dr. Kneipp et al. developed and tested the public health nurse case management intervention using a community-based participatory research approach that engaged TANF, public health nursing, Medicaid administrators, employers, and women receiving TANF (Kneipp et al., 2011; Lutz, Kneipp, & Means, 2009). The positive outcomes from this intervention prompted the Agency for Health-care Quality & Research to include it on its Innovations Exchange Web site, which was developed to speed the implementation of new and better ways of delivering health care (https://innovations.ahrq.gov/profiles/public-health-nurses-provide-case-management-low-income-women-chronic-conditions-leading) (Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality, 2015). Dr. Kneipp also partnered with PHN and TANF managers to develop and pilot test an animated simulation-based video designed with PHN and TANF managers to elicit adoption interest in NC (Kneipp et al., 2015). Rigorous application of marketing theory and participatory principles were used in this process to customize dissemination formats to managers’ needs and preferences—including a projected estimate of the health and employment outcomes, and the anticipated cost savings that would occur in each manager’s county over time (n = 50 managers). Neither distributing the intervention on the Innovations Exchange nor promoting it via a novel simulation-based video has led to larger-scale implementation. The pilot test of the simulation-based video found that the manager’s first impression of the intervention (following a single sentence description) explained most of the manager’s adoption interest after viewing the video. This suggests that TANF and PHN middle managers have preconceived notions of the types of programs they believe would be of value or worth exploring, and that these ideas are unlikely to change—even when presented with empirical evidence, or facts, that demonstrate expected benefit. Dr. Kneipp’s experience indicates that communication strategies alone are ineffective for persuading midlevel decision makers in these organizational environments to change current practices, even when the outcomes were clearly beneficial to the clients and agency. Communication strategies may need to be coupled with other strategies such as external policy, as exemplified by the 1996 passage of TANF legislation mandating domestic violence screening. In that case, 48 of the 50 U.S. states implemented domestic violence screening to avoid potential reductions in federal monetary support for TANF programs (General Accountability Office, 2005).

Partnering with Emergency Medical Services

Dr. Jessica Zègre-Hemsey aims to improve the early identification of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Prompt identification and accurate diagnosis of ACS is essential to delivery of life-saving reperfusion therapy that optimizes patient outcomes. Emergency Medical Service (EMS) personnel often are the first point of medical contact for patients suffering from ACS. Therefore, partnering with EMS is critical to advancing emergency cardiac care for time-sensitive cardiovascular conditions. Dr. Zègre-Hemsey’s research is in the formative stage and currently focuses on describing the use of electrocardiography for ambulance patients across the state. She partnered with the NC State Office of EMS to analyze more than 1 million patient encounters across the state to determine how many cardiac patients received prehospital electrocardiography between 2008 and 2014. In a second study, she is partnering with MEDIC, NC’s largest EMS system, to assess the influence of EMS personnel’s electrocardiogram interpretation on the accuracy of ACS diagnosis. These collaborations are fundamental to developing future interventions aimed at improving rapid diagnosis, clinical decision making, patient access to emergency cardiac care, and long-term outcomes. Dr. Zègre-Hemsey’s interdisciplinary research team includes EMS providers, cardiologists, emergency medicine physicians, and a cardiovascular epidemiologist who contribute both regional and statewide perspectives to her work. She has ongoing communication with the State EMS office to report on progress of her study. She also is serving on the American Heart Association Mission: Lifeline committee, a national initiative to improve cardiovascular systems of care. Dr. Zègre-Hemsey recently presented her program of research at the NC State Legislative Building in support of a bill that would extend access to emergency cardiac care by medical drones.

Lessons Learned

Understand National and Regional Organizations’ Decision-Making Structure

Organizations differ in the extent to which they have a hierarchical as opposed to horizontal decision-making structure. In more hierarchical decision-making structures, individuals in the national or regional office may decide what new practices will be adopted and then communicate that decision down through the hierarchy. In more horizontal decision-making structures, individuals in the national or regional office may promote new practices, but each local organization decides whether they will adopt. Once researchers understand the system’s decision-making structure, they need to decide whether to engage those in the national or regional office first (i.e., a top–down approach), those in the local organizations (a bottom–up approach), or both. In a more hierarchical system, engaging the national or regional office’s top leadership at the start of the project may be effective, if the researcher is able to do so. This approach is seen most clearly in Dr. Beeber’s work with NFP where she included the NFP model developer, Dr. David Olds, and national NFP consultants, supervisors, and regional experts on her team early in the development of her project. Engaging the national or regional office may not always be possible early on. In that case, and also in more horizontal systems, researchers may benefit from a more bottom–up approach where they engage a local opinion-leading organization to pilot the intervention and then assist the researcher in marketing the intervention to peer local organizations and to the regional or national office. This approach is evident in Dr. Tole’s work, which he started with Lutheran Services leadership in one region of NC. After the completion of a successful pilot, LSC leadership then connected him with the Lutheran Services America national office. Dr. Zègre-Hemsey partnered first with the local EMS Performance Improvement Center at University of North Carolina, which led her to collaborate with the State EMS office.

Build Strong Interpersonal Relationships

Decades of research support the importance of interpersonal connections to the diffusion of new practices within a social system (Rogers, 2003). Individuals are most willing to adopt new interventions when they learn about them from someone they know and trust. Dr. Kneipp and her team’s experience illustrate the limitations to using online communication strategies alone to promote the adoption of her intervention, even when the intervention offered clear benefits to the intended audiences’ clients and agency. Researchers can develop relationships with individuals at the local, state, and/or national levels. Partnerships with opinion leaders, in particular, contribute to successful implementation within a setting and to the adoption of an intervention across organizations (Damschroder et al., 2009). Opinion leaders are individuals who are well known and respected by their colleagues and who are willing to try new things (Rogers, 2003). Dr. Hodges, for example, developed a strong relationship with the NC State Lead for PAT. He initially contacted the national director of research and evaluation to present his ideas about the study, and she connected him with the NC State Lead who has served as his chief liaison to both the national PAT office and local NC PAT affiliates. Dr. Hodges reports that the importance of this relationship cannot be overstated. The NC State Lead has championed his project to local PAT affiliates and has acted as an intermediary to connect the research team with local parent educators and has ensured that all interactions started off on a positive note.

The early stages of the relationship are particularly important to ensuring a strong long-term partnership. Early indicators of a potentially strong partner include enthusiasm for the intervention, willingness to brainstorm ways to engage the organization with the intervention, and ability to articulate how the intervention will address needs and align with existing infrastructure. Another early indicator is the partner’s responsiveness to requests for information or to schedule meetings without need for follow-up reminders. Engaging leadership is central to efforts at broad-scale implementation (Damschroder et al., 2009). Therefore, relationships need to be developed with an organizational leader or with someone who has been endorsed by the leadership to champion the intervention.

Start Small and Build on Early Successes

Pilot studies play an important role in establishing a researcher’s reliability and credibility within a network of national, regional, and local organizations. Pilot studies also provide early evidence of an intervention’s feasibility and value. All five researchers began with pilot studies and are now building on those initial successes. For example, Dr. Tole’s pilot study in three NC SNFs (2015–2016) demonstrated that his intervention was feasible, acceptable to staff, and associated with improvements in the degree that patient and caregiver dyads were prepared for discharge to home. The pilot study also provided an opportunity to test the feasibility of embedding new tools in the electronic medical records system, thereby creating a foundation for long-term sustainability of the intervention.

Align with Organizations’ Goals/Priorities

Self-interest is a central marketing concept, and marketing research is key to identifying how the product might align with each audiences’ self-interests (Maibach et al., 2006). Through his ongoing partnerships, Dr. Toles has been able to align his intervention with the goals and priorities of his target audience, an audience whose priorities are continuously evolving to keep pace with the ever-changing landscape of policies governing SNFs. From 1997 to 2014, SNF care became one of the most profitable sectors in the U.S. health care context. Since the recent emphasis on value-based purchasing of health care services, tremendous energy has been spent to shift the care of older adults away from SNFs and to compress the length of stay of those who are admitted for SNF care. These recent changes have exacerbated the challenge of providing discharge planning and transitional care within SNFs, which have created an opportunity for Dr. Toles to align his intervention with Lutheran Services America’s emergent priorities. Dr. Toles is able to promote his intervention as a tool for discharge planning for high acuity patients and as a response to new laws taking effect in 2018 that will create reimbursement penalties for nursing homes with high rates of rehospitalization after discharge.

Integrate Interventions with Existing Processes and Structures Across Layers of a Hierarchy

Factors at multiple levels influence how readily an intervention will be implemented into practice. This includes factors at the level of the individuals who deliver the intervention, the organizations where they work, and the larger systems and political context in which those organizations function (Damschroder et al., 2009). Formative research is essential to understanding these factors so that the intervention will integrate across levels. Dr. Beeber did extensive formative work to fit her intervention strategies within the national NFP system. In partnership with national NFP consultants, supervisors, and regional, she designed her intervention strategies to support the 18 existing NFP model elements. She and her team then assessed the strategies’ fit in pilots in five states, monitoring implementation with follow-up conferences with agency-level NFP supervisors. They also solicited input from the national office educators to help shape the elements that would ultimately be included in the online nationally distributed version.

Provide Ongoing Support for Implementation

Audiences often need support for how to use a product and technical assistance to troubleshoot problems as they arise (Kreuter & Bernhardt, 2009). This is particularly true of nurse-developed interventions, which are often complex, involving multiple integrated strategies and repeated contacts overtime (Leeman, 2006). By partnering with national and regional organizations, intervention developers have the opportunity to build on existing infrastructure to provide ongoing support for their interventions more efficiently than may otherwise be possible. To facilitate support for his intervention within PAT, Dr. Hodges studied the existing PAT curriculum that guides the work of the parent educators who would deliver his intervention. By doing so, he was able to assess what already exists that aligns with planned intervention components, what is missing, and features to include in new lesson plans to facilitate intervention delivery by parent educators in the field. Through seeing the existing lesson plans, he and his team were able to design intervention materials in ways that will be familiar in format to existing materials parent educators already use.

Conclusions

Similar to other interventions, nurse-developed interventions have been slow to translate into practice. Partnering with national and regional organizations is one strategy that nurse researchers’ can use to speed the translation of their interventions. As documented in this article, a wide variety of organizations are available and include national nonprofits, health delivery system, and government agencies among others. Partnerships with these organizations can assist nurse researchers in designing interventions to align with the organization’s existing resources and processes; staffs’, patients’, and clients’ needs; and with external policies and other incentives. By partnering with national and regional organizations, nurse researchers also might leverage existing infrastructure to promote, distribute, and support their interventions more widely than they could do on their own.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ) About the AHRQ health care innovations exchange. 2015 Retrieved from https://innovations.ahrq.gov/about-us.

- Beeber LS, Schwartz T, Holditch-Davis D, Canuso R, Lewis V. Parenting enhancement, interpersonal psychotherapy to reduce depression in low-income mothers of infants and toddlers: A randomized trial. Nursing Research. 2013;62(2):82–90. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31828324c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeber LS, Schwartz T, Holditch-Davis D, Canuso R, Lewis V, Matsuda Y. Interpersonal Psychotherapy with a Parenting Enhancement Adapted for In-Home Delivery in Early Head Start. Zero To Three. 2014;34:35–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Morgan-Lopez AA, Cox MJ, McLoyd VC. A latent class analysis of maternal depressive symptoms over 12 years and offspring adjustment in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;3:479–493. doi: 10.1037/a0015923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciciolla L, Gerstein ED, Crnic KA. Reciprocity among maternal distress, child behavior, and parenting: Transactional processes and early childhood risk. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43(5):751–764. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.812038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing JW, Kreuter MW. Designing for diffusion: How can we increase uptake of cancer communication innovations? Patient Education & Counseling. 2010;8:S100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing JW, Maibach EW, Buller DB. A convergent diffusion and social marketing approach for disseminating proven approaches to physical activity promotion. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;31:S11–S23. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disantis K, Hodges EA, Johnson SL, Fisher JO. The role of responsive feeding in overweight during infancy and toddlerhood: a systematic review. International Journal of Obesity. 2011;35:480–492. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. (PAR-16-238).Dissemination and implementation research in health. 2016 Retrieved from http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-16-238.html.

- Feder A, Alonso A, Tang M, Liriano W, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Weissman MM. Children of low-income depressed mothers: Psychiatric disorders and social adjustment. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:513–520. doi: 10.1002/da.20522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- General Accountability Office. (Report no. GAO-05-701).TANF: State approaches to screening for domestic violence could benefit from HHS guidance. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-05-701.

- Hannon PA, Fernandez ME, Williams RS, Mullen PD, Escoffery C, Kreuter MW, Bowen DJ. Cancer control planners’ perceptions and use of evidence-based programs. Journal of Public Health Management& Practice. 2010;16:E1–E8. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181b3a3b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EA, Wasser HM, Colgan BK, Bentley ME. Development of feeding cues during infancy and toddlerhood. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. 2016;41(4):244–251. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AP, Brooks-Gunn J, Huang CC, Glassman M. Single mothers in low-wage jobs: Financial strain, parenting, and preschoolers’ outcomes. Child Development. 2000;7:1409–1423. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneipp SM, Kairalla J, Lutz BJ, Pereira DB, Hall A, Flocks J, Schwartz T. Effectiveness of public health nursing case-management on the health of women receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: Findings from a randomized controlled trial using community based participatory research. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101:1759–1768. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneipp SM, Kairalla JA, Sheely AL. A randomized controlled trial to improve health among women receiving welfare in the U.S.: The relationship between employment outcomes and the economic recession. Soc Sci Med. 2013;80:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneipp SM, Leeman J, McCall P, Hassmiller-Lich K, Bobashev G, Schwartz TA, Gil B. Synthesizing marketing, community engagement, and systems science approaches for advancing translational research. Advanced Nursing Science. 2015;38:227–240. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Bernhardt JM. Reframing the dissemination challenge: A marketing and distribution perspective. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(12):2123–2127. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.155218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman J. Interventions to improve diabetes self-management: Utility and relevance for practice. Diabetes Educator. 2006;32:571–583. doi: 10.1177/0145721706290833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman J, Sandelowski M. Practice-based evidence and qualitative inquiry. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2012;44:171–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz BJ, Kneipp S, Means D. Developing a health screening questionnaire for women in welfare transition programs in the United States. Qualitative Health Research. 2009;19:105–115. doi: 10.1177/1049732308327347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maibach EW, Van Duyn MAS, Bloodgood B. A marketing perspective on disseminating evidence-based approaches to disease prevention and health promotion. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2006;3:A97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to Congress. Medicare Payment Policy. 2016 Retrieved from http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/june-2016-report-to-the-congress-medicare-and-the-health-care-delivery-system.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- Olds DL, Kitzman H, Hanks C, Cole R, Anson E, Sidora-Arcoleo K, Bondy J. Effects of nurse home visiting on maternal and child functioning: Age-9 follow-up of a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2007;120:832–845. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. New York, NY: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens KR, Staley JM. The Quality Chasm reports, evidence-based practice, and nursing’s response to improve healthcare. Nursing Outlook. 2006;54(2):94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD, Saffitz GB, Rimon JG. Social marketing. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanathan K, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2008. pp. 435–464. [Google Scholar]

- Toles M, Colon-Emeric C, Asafu-Adjei J, Moreton E, Hanson LC. Transitional care of older adults in skilled nursing facilities: A systematic review. Geriatric Nursing. 2016;37:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toles M, Colon-Emeric C, Naylor MD, Asafu-Adjei J, Hanson LC. Connect-Home: Transitional care of skilled nursing facility patients and their caregivers. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2017 doi: 10.1111/jgs.15015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15015 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Turney K. Pathways of disadvantage: Explaining the relationship between maternal depression and children’s problem behaviors. Social Science Research. 2012;41:1546–1564. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]