Abstract

There is significant morbidity and mortality associated with the transmission of herpes simplex virus (HSV) from pregnant women to their fetus or newborn. Although most commonly transmitted in the peripartum period, in rare cases HSV can lead to intrauterine infection. Cutaneous lesions are the most common manifestation of intrauterine HSV, and have a wide spectrum of presentation. We present a rare case of intrauterine HSV-2 infection presenting with a zosteriform eruption mimicking congenital varicella syndrome in a newborn.

Keywords: neonatal, infection—viral, rash, TORCH

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections are common in women of childbearing age throughout the world. Seroprevalence of HSV-1 and HSV-2 in the United States between 2005 and 2010 were ∼54% and 16%, respectively. 1 HSV-1 and HSV-2 infections transmitted from pregnant women to their fetus or newborn are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. 2 HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection of the newborn can be acquired in utero, postpartum, or peripartum. The estimated rate of occurrence of neonatal HSV is 1 in 3,200 deliveries. The majority of neonates (85%) are infected in the peripartum period, with only 5% of infections thought to occur in utero. 2 Given its uncommon occurrence and variable presentation, a high index of suspicion is required to diagnose intrauterine HSV infection. We present a rare case of intrauterine HSV-2 infection presenting with a zosteriform eruption mimicking congenital varicella syndrome.

Case

A baby girl was born at 37 4/7-week-gestation by cesarean section for breech presentation to a 17-year-old, gravida one woman who received regular prenatal care. Pregnancy was uncomplicated; all prenatal laboratory tests were unremarkable. The baby was vigorous at birth and required routine delivery room care. On initial examination, the baby was noted to have a rash involving her right chest, arm, and upper back.

Physical examination showed a symmetrically small for gestation infant. With the exception of the skin examination, the infant had no additional abnormal physical findings. The skin examination was notable for erythematous erosions and scarred, thin plaques, some with overlying crust, in a T1 to T3 dermatomal distribution over the right anterior chest, trunk, and back ( Fig. 1 ). There was a 1.5cm × 0.5cm cicatricial plaque over the right upper back ( Fig. 2 ). Additionally, there were several rounds, erythematous macules and healing round erosions clustered in the same dermatomal distribution along the right upper extremity and dorsum of right hand. There were no intact vesicles present. Nikolsky sign was negative.

Fig. 1.

Zosteriform rash in the T1 to T3 dermatomal distribution present at birth.

Fig. 2.

Cicatricial plaque over the right upper back.

White blood cell count was 7500 mm 3 with 59% neutrophils, 6% bands, 20% lymphocytes, and 15% monocytes. Hemoglobin was 20.2 g/dL, hematocrit 58.3%, and platelets 66 k/μL. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) contained 22 red blood cells/mm 3 , 9 white blood cells/mm 3 , protein 90 mg/dL, and glucose 49 mg/dL. Complete metabolic panel was normal.

A blood culture was drawn and the patient was then started on ampicillin and gentamicin. A skin biopsy, skin bacterial and fungal cultures were obtained. The skin lesions were swabbed for HSV ½ and varicella zoster virus (VZV) deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. Blood samples were sent for rapid plasma regain test, HSV ½, VZV, human immunodeficiency virus, and enterovirus PCR. CSF was obtained and sent for HSV ½ DNA PCR. While these tests were pending, intravenous (IV) acyclovir was also started. Eye examination and head ultrasound were normal. Maternal serologies were negative for cytomegalovirus, toxoplasma gondii, syphilis, and HSV-1. Mother was rubella and varicella immune. She was negative for anti-Sjögren's-syndrome-related antigen A (SS-A), anti-SS-B, and anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein antibodies. However, her blood sample was positive for HSV-2 immunoglobulin G antibodies.

The patient received 72 hours of antibiotics; all bacterial and fungal cultures returned negative. Thrombocytopenia resolved without intervention. She completed 10 days of IV acyclovir at 20 mg/kg every 8 hours. The original skin biopsy showed nonspecific erosion, shallow ulceration, and inflammatory cell infiltrate. Biopsy immunostaining was negative for HSV ½. The patient remained in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) to work on oral feeding.

Over the NICU course, the areas of erosion and crusting improved with re-epithelialization and some areas of post-inflammatory hypopigmentation. The cicatricial lesion became smaller in size ( Fig. 3 ). The skin swab from an eroded plaque was positive for HSV-2 DNA by PCR amplification. However, this positive result was suspected to be due to contamination from intrapartum exposure as the swab was obtained in the first few hours of life. The final diagnosis was made 1 week after completion of acyclovir therapy when the patient was noted to have new onset of vesicopustular lesions clustered over the right chest, arm, and palm of right hand ( Fig. 4 ). Repeat biopsy showed classic viral cytopathic changes ( Figs. 5 , 6 ). Lesional immunostaining and PCR confirmed a diagnosis of HSV-2 ( Fig. 7 ). She was diagnosed with intrauterine HSV-2 infection given the presence of the skin lesions at birth. The patient completed a second 14-day course of IV acyclovir and the skin lesions healed. She was then transitioned to oral acyclovir with plan for 6-month course of suppressive therapy.

Fig. 3.

Healing lesion.

Fig. 4.

Vesicopustules present following discontinuation of IV acyclovir.

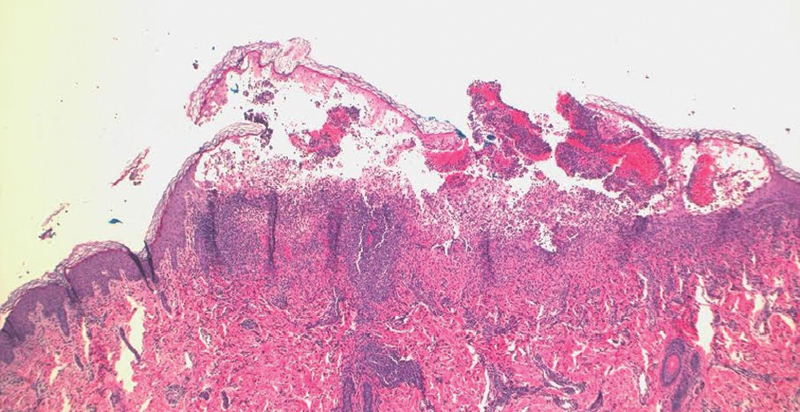

Fig. 5.

Vesiculation, epidermal edema and inflammatory infiltrate present on hematoxylin and eosin, low power.

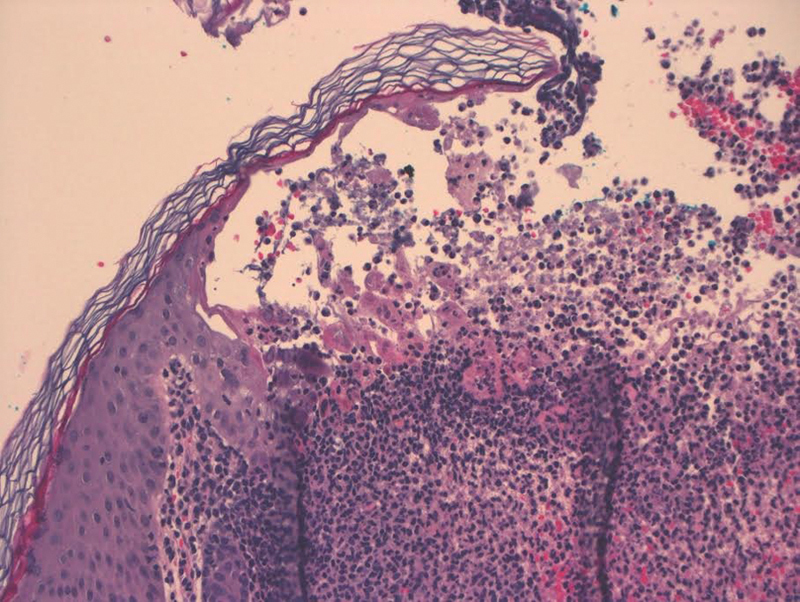

Fig. 6.

Keratinocytes with multinucleation and classic viral cytopathic change on hematoxylin and eosin, high power.

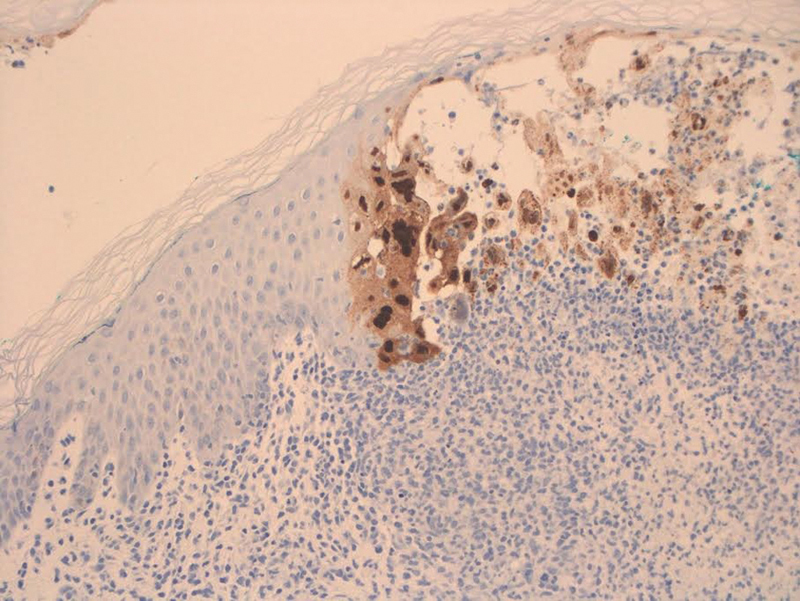

Fig. 7.

Immunostaining positive for herpes simplex virus 2.

Discussion

Intrauterine HSV infection is a rare occurrence with a variable spectrum of presentation. It is thought to affect only 1 in 300,000 deliveries. 3 It is the rarest form of neonatal HSV, with 85% of cases infected in the peripartum period, 10% of cases acquired postnatally, and only 5% of cases from in utero transmission. In utero, there are two identifiable routes of transmission, either transplacental or ascending infection, even in the absence of ruptured membranes. 3 Both primary and recurrent HSV infections can lead to viral transmission to the fetus. 4 Recognition of intrauterine HSV infection is important as it is associated with severe outcomes such as spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm birth, neonatal death, or significant neurodevelopmental impairment. 3 A set of diagnostic criteria for intrauterine HSV infection include evidence of disease within the first 48 hours of life, virologic confirmation of infection, and exclusion of other pathologic conditions. 4

Classically, intrauterine HSV infection manifests as a clinical triad of cutaneous, ophthalmologic, and central nervous system (CNS) symptoms present at birth. However, this classic triad is only found in about a third of diagnosed cases. In the largest review of intrauterine HSV cases, the classic triad was found in 30% of patients. 3

Overall, cutaneous lesions are the most common clinical manifestation, present in 92% to 95% of neonates with intrauterine HSV. 3 5 6 7 The variability in cutaneous disease is thought to be one of the main factors contributing to under recognition of intrauterine HSV. Although patients can present with the typically recognized vesicular lesions, cutaneous lesions in intrauterine HSV may also present as bullae, erosions or ulcerations, pustules, plaques, maculopapules, areas of denudation, or cutis aplasia. 3 4 7 Given this spectrum of presentation, the cutaneous lesions of intrauterine HSV can often be mistaken for other TORCH infections, epidermolysis bullosa, aplasia cutis congenita, or incontinentia pigmenti. 3

Very rarely, as in our patient, intrauterine HSV can present with a zosteriform eruption mimicking congenital varicella syndrome. Intrauterine varicella infection is observed to cause characteristic skin lesions such as cicatricial scars or skin loss in a dermatomal distribution. 5 Three cases of zosteriform skin denudation or segmental scarring following intrauterine HSV infection are currently reported in the literature. 6 7 These areas of denuded skin or scarring are thought to be the sequela of vesicular eruptions present earlier in gestation. 3 In all three cases, initial viral culture of the congenital lesions was negative and biopsies nonspecific, likely given the age of the lesions. Only on reculture of fresh vesicles, which erupted in each patient following completion of IV acyclovir, HSV-2 was recovered. 6 7

Early initiation of acyclovir is crucial in the treatment of intrauterine HSV infection; particularly when suspicious skin lesions are present within the first 48 hours of life. Unfortunately, treatment cannot affect damage already sustained in utero, rather, it is aimed at prevention of progression to CNS disease. 3 As in our patient, 50% of infants will experience cutaneous recurrence of disease within 1 to 2 weeks of discontinuing IV acyclovir treatment. Therefore, following parental treatment, patients should be transitioned to oral acyclovir suppressive therapy for 6 months. This suppressive therapy not only prevents skin recurrences, but it can improve neurodevelopmental outcomes in patients with CNS disease. 8

Conclusion

Intrauterine HSV is an uncommon diagnosis with a variable presentation. A zosteriform rash is not typical for this diagnosis. As the sole presenting symptom, it can make intrauterine HSV difficult to diagnose, particularly since the age of the lesions may lead to false-negative culture or biopsy results. Early initiation of IV acyclovir is crucial to prevent the progression of cutaneous HSV to CNS disease. Therefore, a high index of suspicion and early initiation of acyclovir are vital in the diagnosis and treatment of intrauterine HSV infection.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. No financial support was received in the creation of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest None.

Consent for Publication

All authors consent to publication of this article in its current form.

References

- 1.Bradley H, Markowitz L E, Gibson T, McQuillan G M. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2--United States, 1999-2010. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(03):325–333. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimberlin D W. Neonatal herpes simplex infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(01):1–13. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.1.1-13.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marquez L, Levy M L, Munoz F M, Palazzi D L. A report of three cases and review of intrauterine herpes simplex virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(02):153–157. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181f55a5c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin S, Whitley R J. Intrauterine herpes simplex virus infection. Teratology. 1989;39(01):1–10. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420390102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sauerbrei A, Wutzler P.The congenital varicella syndrome J Perinatol 200020(8 Pt 1):548–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabalais G P, Adams G, Yusk J W, Wilkerson S A. Zosteriform denuded skin caused by intrauterine herpes simplex virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991;10(01):79–80. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199101000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cliff S, Ostlere L S, Haque K, Harland C C. Segmental scarring following intrauterine herpes simplex virus infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22(02):96–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Academy of Pediatrics.Herpes simplex Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015432–445. [Google Scholar]