Abstract

To understand mechanisms underlying the relationship between adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and diabetes the study evaluated mediators of the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and diabetes in adulthood. This study used cross-sectional data from the 2011 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS). Participants totaled 48, 526 who completed the ACE module. Based on theoretical relationships, path analysis was used to investigate depression and obesity as pathways between childhood sexual abuse, and diabetes in adulthood.

Among adults with diabetes, 11.6% experienced sexual abuse. In the unadjusted model without mediation, sexual abuse was significantly associated with depression (OR=4.48, CI 4.18–4.81), obesity (OR=1.28, CI 1.19–1.38), and diabetes (OR=1.39, CI 1.25–1.53). In the unadjusted model with mediation, depression and obesity were significantly associated with diabetes (OR=1.59, CI 1.48–1.72, and OR=3.77, CI 3.45–4.11, respectively), and sexual abuse and diabetes was no longer significant (OR=1.10, CI 0.98–1.23), suggesting full mediation. After adjusting for covariates in the mediation model, significance remained between sexual abuse and depression (OR=3.04, CI 2.80–3.29); sexual abuse and obesity (OR=1.41, CI 1.29–1.53), depression and diabetes (OR=1.35, CI 1.23–1.47); and obesity and diabetes (OR=3.53, CI 3.20–3.90). The relationship between sexual abuse and diabetes remained insignificant (OR=1.09, CI 0.96–1.24).

This study demonstrates that depression and obesity are significant pathways through which childhood sexual abuse may be linked to diabetes in adulthood. These results can guide intervention development, including multifaceted approaches to treat depression and increase physical activity in patients with a history of sexual abuse to prevent diabetes.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), childhood maltreatment occurred in 3.4 million children in 2012 and it is estimated that every year, 1 in 4 children will experience some form of maltreatment in the United States [1]. Childhood maltreatment is of significant public health concern as research shows that the consequences span through adulthood and include impaired cognitive development, risky health behaviors, greater disease burden, and early mortality [1–2]. Broadly defined, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are stressful events occurring throughout the developmental stages of a child’s life that can have traumatic effects and impact on health and behavior in adulthood. These include four domains of abuse including psychological, physical, sexual, and household dysfunction [2].

Recent examination of the impact of ACEs on adult health has shown that individuals who experience ACEs are at greater risk for the development of chronic diseases in adulthood, including diabetes [2–5]. The relationship between ACEs and diabetes has been found to be graded and the literature suggests that specific ACEs as well as variations in intensity of ACEs experienced may have more impact on the development of diabetes than others [4–7]. Diabetes is an important public health concern, affecting more than 29 million people or 9.3 % of the total U.S. population, and is the seventh leading cause of death in the U.S. [8] Medical expenditures among those diagnosed with diabetes are twice the expenditures of those without, with primary expenditures arising from inpatient hospital stays as well as cost of prescriptions [9]. In 2012, the overall direct and indirect cost of diabetes in the U.S. was $245 billion [8]. Current trends predict that as many as 1 in 3 Americans will have diabetes by the year 2050 [10].

The literature has shown that of the various ACE categories, childhood sexual abuse, in particular, is strongly linked to the development of diabetes in adulthood in both men and women, compared to other chronic illness [5;11;26]. For instance, Shields et al 2016 found that experiencing sexual abuse was related to 1.5 to 2 fold increase of developing diabetes in adulthood, with increased risk being associated with intensity of sexual abuse reported. Additionally, Campbell et al 2016 found that individuals who experienced sexual abuse were 45% more likely to develop diabetes in adulthood compared to 14% and 18% for coronary heart disease and stroke, respectively [11]. The hypothesized mechanisms underlying this relationship between ACEs, such as sexual abuse, and diabetes include both physiological and psychosocial pathways [15–17]. The physiological pathway is hypothesized to occur via chronic stress that leads to inflammatory and metabolic alteration, ultimately disrupting metabolic function [16–19]. The psychosocial pathway is thought to occur via accumulated risk factors for poor health behaviors that impact overall health outcomes over time [16–19]. However, the design for the studies testing these proposed mechanisms have various limitations. For example, studies examining alteration of inflammatory responses have been limited by differential processes for defining and classifying exposure [17]. Similarly, studies evaluating the psychosocial pathway have been restricted by small sample size and lack of standardization in measures [19].

While the literature has examined the association that overall ACEs have with the development of diabetes, greater understanding about the potential mediators of the relationship is needed to develop more targeted public health interventions. In order to address this gap in knowledge, this study evaluates the mediators of the relationship between sexual abuse in childhood and self-reported diabetes in adulthood using path analysis and theory based models to test for mediation. Sexual abuse was selected from the ACE categories for independent path analysis based on suggestions of the literature as being a siginificant predictor of diabetes in adulthood in comparison to other ACE categories [5;11–12;26]. Using national data from the 2011 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), this study helps elucidate potential pathways through which sexual abuse in childhood and diabetes in adulthood are associated.

Research Design and Methods

Sample

This study used data from the 2011 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey, a cross-sectional telephone survey organized by the CDC. Participants include non-institutionalized adults 18 years and older in the United States. Data collection is conducted by state health departments using random-digit dialing to landline and cellular telephones [20]. Nationally representative estimates are achieved through a complex sampling design using data weighting in analysis [20]. The CDC, in collaboration with public health departments, develop standardized questionnaires in each state and include a standard core, optional modules, and state-added questions [20]. Participants completing the 2011 BRFSS survey totaled 506,467, with 48,526 participants completing the ACE module across five states. This study sample only included data from the five states that administered the ACE module: Minnesota, Montana, Vermont, Washington and Wisconsin. The current study was exempt from Institutional Review Board (IRB) review since it was a secondary analysis of publicly available data.

Measures

Adverse childhood experiences (ACE): an 11-item survey where respondents are asked if they ever experienced sexual, physical, or verbal abuse, or family dysfunction during their childhood (prior to 18 years of age) [20]. In this study, we focused on responses to the three questions specific to sexual abuse. Respondents noted frequency of experiencing anyone at least 5 years older, or an adult, ever forcing sex; forcing touching; or if respondent was ever forced to touch sexually. As this analysis focused primarily on pathways using a logit model, positive response to any frequency on any of the three questions was coded as a yes (vs. no) on a dichotomous variable to assess sexual abuse. Dichotomizing this variable is a valid method seen else where [11;13;14].

Diabetes

Diabetes was self-reported, using the question: Has a doctor or other healthcare provider ever told you that you have diabetes? Based on prevalence estimates approximately 95% of the diabetes population have type 2 diabetes and only 5% have type 1 diabetes [8]. As such, this variable is used as an estimate of U.S. adults assumed to indicate type 2 diabetes [21].

Depression

Depression was a self-report measure using the question: Has a doctor or other healthcare provider ever told you that you have a depressive disorder (including depression, major depression, dysthymia, or minor depression)? This variable is a validdated measure used in the literature [22].

Overweight/Obesity

Overweight/Obesity was assessed based on Body Mass Index (BMI) ≥ 25. The BMI calculated variable from the BRFSS 2011 dataset was used. Calculated variable for BMI in BRFSS is derived from WTKG3 and HTM4. It is calculated by dividing WTKG3 by HTM42 as recommended by the CDC [20]. This variable is validated measure used in the literature and was categorized as higher than 25 or less than 25 using standard calculations based on CDC designation [21;23].

Demographics

The BRFSS survey collects age, gender, race, marital status, education, employment, region of the United States, and income from all individuals. Age was categorized as 18–34 years, 35–54 years, 55–64 years, and 65 years or greater. Gender was dichotomized. Race/ethnicity was categorized as Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Other. Due to sampling distribution, Native American, Pacific Islander, Asian and other were categorized as Non-Hispanic Other. Marital status was characterized as married, separated / divorced / widowed, and not married. Education was categorized as less than high school education, high school graduate, some college, and college graduate. Employment was categorized as unemployed, employed and retired. Region was categorized as Northeast, Midwest, and West. No state from the Southern region of the United States was included in this optional module. Income was categorized as less than $15,000, $15,000–$24,999, $25,000–$34,999, $35,000–$49,999, and greater than or equal to $50,000. Health status was categorized as excellent/very good/good versus fair/poor.

Statistical Analyses

Preliminary descriptive analyses were performed to identify potential departures from parametric distributional assumptions and since the data was normally distributed, parametric statistics were used. Chi-square statistics were used to compare categorical variables, including sample demographics by diabetes status. Chi-square statistics were also used to compare sexual abuse status by diabetes status.

Path analysis was used to investigate depression and obesity as potential pathways between sexual abuse in childhood and diabetes in adulthood. Path analysis is based on an a priori model, similar to the use of a priori hypothesis in regression. Consistent with the literature on path analysis, the hypothesis is set with an a priori model, which is then tested to determine if the data fits the model. Fit statistics are used to confirm fit. No post hoc analysis are used in path analysis, and therefore were not used in the current analysis. The current analysis followed the methodology as outlined by Shuemacker et al 2010, and Kline et al 2011. Path analysis allows inclusion of multiple predictor and multiple outcome variables, testing simultaneous regression models based on a priori hypothesis regarding causal relationships [24–25]. By including multiple relationships in a single model using path analysis, this method allows for correlation between variables and more valid estimates than separate individual regression models [24]. The ‘gsem option’ in Stata v14, which fits generalized structural equation models (SEM; including SEM with generalized linear response variables and SEM with multilevel mixed effects) was used because several of the outcome and predictor variables (e.g. diabetes, depression, sexual abuse) were binary variables. The ‘estat eform option’ was run after the model to exponentiate coefficients into odds ratios. Given the large sample size, we maintained the 20:1 recommended ratio of observations to variables, which provided 80% power [25]. This sample size minimizes the likelihood of oversaturating the model with variables, thereby, minimizing instability of estimates.

The first model tested was an unadjusted model, without mediation, between sexual abuse and 1) depression, 2) obesity, and 3) diabetes status. The second model was without mediation, and adjusted for the covariates of age, race, gender, marital status, educational attainment, region, and income. The third model was an unadjusted model with mediation of both depression and obesity between sexual abuse and diabetes. In this model, paths were hypothesized to exist between 1) sexual abuse and diabetes, 2) sexual abuse and depression, 3) sexual abuse and obesity, 4) depression and diabetes, and 5) obesity and diabetes. The fourth and final model was a model with mediation and adjusted for the covariates of age, race, gender, marital status, educational attainment, region, and income. If a significant path exists between sexual abuse and diabetes, which after mediation is no longer significant, the models suggest full mediation. If the path remains significant, but the odds ratio decreases, the models suggest partial mediation. Both unadjusted and adjusted models were included to ensure important demographic covariates known to influence both sexual abuse and diabetes status were accounted for in the model estimates.

Results

Table 1 shows sample characteristics overall and by diabetes status in the subpopulation of BRFSS respondents asked ACE questions. Among participants, the majority were age 35–54, and 50% were women. Approximately 83% were white, 60% were employed, 55% had an annual household income less than $50,000, 29% were high school graduates, and 33% had some college. There were statistically significant differences in demographics between those with and without diabetes, except for gender. Of those who responded they had been diagnosed with diabetes, 11.6% also reported having experienced sexual abuse, compared to 7.2% for those not reporting diabetes diagnosis.

TABLE 1.

Sample Demographics by Diabetes Status in Subpopulation, US 2011

| Characteristics | All | Diagnosis of Diabetes | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| N=51548 | N (%) | % No | % Yes |

|

| |||

| Age in years | |||

| 18 – 34 | 7211 (30.2) | 7096 (32.5) | 115 (05.5) |

| 35 – 54 | 16170 (36.3) | 15178 (37.0) | 992 (28.1) |

| 55 – 64 | 12597 (16.2) | 11045 (15.1) | 1552 (28.2) |

| 65+ | 15570 (17.3) | 12847 (15.4) | 2723 (38.2) |

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Men | 21768 (49.8) | 19381 (49.7) | 2387 (50.5) |

| Women | 29780 (50.2) | 26785 (50.3) | 2995 (49.5) |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White | 45420 (83.7) | 40912 (83.9) | 4508 (81.7) |

| Black | 1197 (3.5) | 990 (03.3) | 207 (05.3) |

| Hispanic | 1498 (5.4) | 1356 (05.5) | 142 (04.0) |

| Other | 2950 (7.4) | 2486 (07.2) | 464 (09.1) |

|

| |||

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 28682 (54.0) | 25990 (53.9) | 2692 (55.6) |

| Divorced | 13928 (18.2) | 11891 (17.1) | 2037 (29.9) |

| Not married | 8668 (27.8) | 8036 (29.0) | 632 (14.5) |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| >HS | 3057 (10.5) | 2566 (10.1) | 491 (14.1) |

| HS graduate | 14261 (29.0) | 12499 (28.7) | 1762 (32.6) |

| Some college | 14949 (33.6) | 13226 (33.5) | 1723 (35.0) |

| College graduate | 19095 (26.9) | 17713 (27.7) | 1382 (18.2) |

|

| |||

| Employment | |||

| Unemployed | 9551 (23.5) | 8266 (23.2) | 1285 (26.7) |

| Employed | 27489 (59.7) | 25888 (61.9) | 1601 (36.0) |

| Retired | 14250 (16.8) | 11785 (15.0) | 2465 (37.3) |

|

| |||

| Region | |||

| NorthEast | 6962 (3.4) | 6264 (03.4) | 698 (03.1) |

| MidWest | 20188 (56.7) | 18255 (57.0) | 1933 (54.1) |

| West | 24398 (40.0) | 21647 (40.0) | 2751 (42.8) |

|

| |||

| Income | |||

| >15k | 4022 (08.1) | 3303 (07.6) | 719 (13.5) |

| 15k – 25k | 7751 (18.2) | 6632 (17.7) | 1119 (23.0) |

| 25k – 35k | 6022 (13.6) | 5288 (13.3) | 734 (17.0) |

| 35k – 49k | 7467 (15.5) | 6707 (15.5) | 760 (15.4) |

| ≥50k | 19772 (44.6) | 18446 (45.9) | 1326 (31.2) |

|

| |||

| Health Status | |||

| Fair/Poor | 7983 (14.4) | 5850 (12.0) | 2133 (41.0) |

| Excellent/ Very Good/Good | 43388 (85.6) | 40167 (88.0) | 3221 (59.0) |

|

| |||

| Sexual Abuse Status | |||

| Yes | 3534 (07.6) | 3052 (07.2) | 482 (11.6) |

| No | 40594 (92.4) | 36444 (92.8) | 4150 (88.4) |

HS=High school

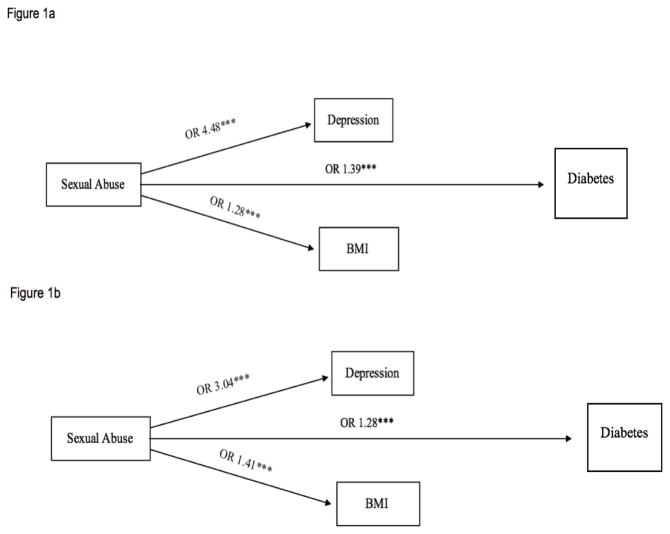

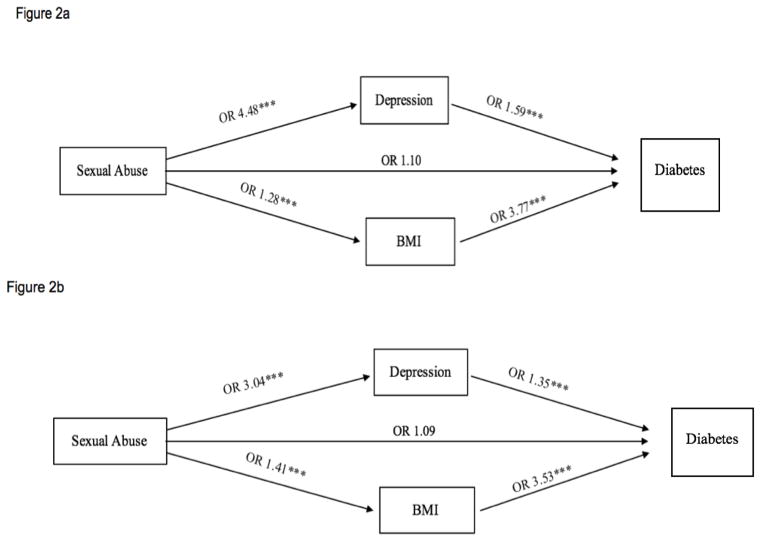

Table 2 and Figures 1(a and b) and 2 (a and b) show the unadjusted and adjusted relationships in models with and without mediation. In the initial unadjusted model, sexual abuse was significantly associated with depression (odds ratio (OR)=4.48, CI 4.18; 4.81), obesity (OR=1.28, CI 1.19; 1.38), and diabetes (OR=1.39, CI 1.25; 1.53). After adjusting for covariates, all relationships remained statistically significant (see Figure 1b). In the unadjusted mediation model, depression (OR=1.59, CI 1.48; 1.72) and obesity (OR=3.77, CI 3.45; 4.11) were significantly associated with diabetes; and the relationship between sexual abuse and diabetes was no longer significant (OR=1.10, CI 0.98; 1.23), suggesting full mediation. After adjusting for covariates, sexual abuse was statistically significantly related to depression (OR=3.04, CI 2.80; 3.29) and obesity (OR=1.41, CI 1.29; 1.53); depression remained significantly associated with obesity (OR=1.35, CI 1.23; 1.47) and diabetes (OR=3.53, CI 3.20; 3.90), and remained insignificant between sexual abuse and diabetes (OR=1.09, CI 0.96; 1.24); see Figure 2b.

Table 2.

Mediation Model for the Relationship Between Sexual Abuse and Diabetes

| Model 1 Without Mediation | Model 2 With Mediation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Unadjusted OR CI | Adjusted OR CI | Unadjusted OR CI | Adjusted OR CI | |

| Depress | ||||

| → Sexual Abuse | 4.48*** | 3.04*** | 4.48*** | 3.04*** |

| 4.18; 4.81 | 2.80; 3.29 | 4.18; 4.81 | 2.80; 3.29 | |

|

| ||||

| BMI >25 | ||||

| → Sexual Abuse | 1.28*** | 1.41*** | 1.28*** | 1.41*** |

| 1.19; 1.38 | 1.29; 1.53 | 1.19; 1.38 | 1.29; 1.53 | |

|

| ||||

| Diabetes | ||||

| → Sexual Abuse | 1.39*** | 1.28*** | 1.10 | 1.09 |

| 1.25; 1.53 | 1.14; 1.44 | 0.98; 1.23 | 0.96; 1.24 | |

|

|

||||

| → Depression | 1.59*** | 1.35*** | ||

| 1.48; 1.72 | 1.23; 1.47 | |||

|

|

||||

| → BMI >25 | 3.77*** | 3.53*** | ||

| 3.45; 4.11 | 3.20; 3.90 | |||

Model adjusted for age, race, gender, marital status, educational attainment, region, and income,

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Unadjusted Without Mediation

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Figure 1b. Adjusted Without Mediation

Model adjusted for age, race, gender, marital status, educational attainment, region, and income,

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Unadjusted Mediated

SEM Path analysis *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Figure 2b. Adjusted Mediated

SEM Path Analysis adjusted for age, race, gender, marital status, educational attainment, region, and income,

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Conclusion

While the relationship between the sexual abuse component of ACEs and the development of diabetes has garnered greater attention more recently, little has been done to fully understand the mechanisms that underlie this relationship. Using path analysis to test for mediation between sexual abuse and diabetes status in adulthood, this study found that the pathway was fully mediated by depression and obesity, before and after adjustment for demographic covariates. This is the first study to our knowledge to test this mechanism using path analysis, which allows for more valid estimates by including multiple regression analyses in one model. Given the prevalence of ACEs in the general population [1–2], and the growing epidemic of diabetes [8], these results can guide future research to test the pathway between different ACE categories and chronic illness, and to further develop interventions to minimize the detrimental impact of this public health concern.

This study uses advanced statistical techniques to test a mechanism previously hypothesized in the literature [11]. In both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses, the literature supports that experiences of sexual abuse in childhood are related to diabetes in adulthood [4, 26]. Evidence also shows that having depression is a significant independent risk factor for the development of diabetes and poor outcomes for those diagnosed [27–29]. Underlying biological mechanisms in this pathway may involve alterations in hormone release and glucose functioning because of depression, ultimately leading to insulin resistance [30]. Furthermore, obesity is a known predictor of diabetes and increased complications [27–29], and has been shown to attenuate the relationship between sexual abuse and diabetes in prior studies [26]. However, a recent study using longitudinal data as part of the Add Health cohort, found BMI did not significantly mediate the relationship between sexual abuse and diabetes [12]. As compared to this analysis, Duncan et al. (2015) did not use theory based path analysis, and instead compared odds ratios between multiple logistic regression models. In addition to methodological differences with our analysis, the age range for those in the Add Health study were younger (ages 24–34) than those in this study. Given the mean and median age of diagnosis for diabetes is 54 years [8], this may explain differences in our findings, as both population’s ethnicities were similar.

Identification of modifiable risk factors as mediators in our study has critical public health prevention implications. For example, physical activity is a well established lifestyle intervention for the treatment of depression and obesity in patients with diabetes and has been shown to improve health outcomes as well as quality of life [31]. This suggests that both depression and obesity can be successfully treated through targeted lifestyle interventions between the age when sexual abuse occurs and adulthood. If pathways can be disrupted through effective treatment of depression and obesity, the impact of sexual abuse on the development of diabetes in adulthood may be reduced.

Limitations

Overall, this study is strengthened by the use of path analysis to evaluate the pathway between sexual abuse and diabetes in adulthood in a large, national data set. However, this study has some limitations that should be noted. First, the BRFSS does not allow for differentiation by diabetes type, as such the assessment of type 2 diabetes is not specific. However, based on the prevalence estimates of diabetes showing 95% of the diabetes population are those with type 2 diabetes [8]. Secondly, measures used in this analysis were self-report and may be impacted by participant recall bias; however prior studies have shown participant recall for chronic illness, such as type 2 diabetes, as well as conditions that have a strong impact on ones’ life, such as traumatic experiences, are very accurate [32–33]. Thirdly, additional confounders not accounted for in this dataset such as other comorbid conditions or lifestyle factors and social support should be explored in future analysis. Additionally, the BRFSS is telephone delivered so may exclude individuals without phone coverage, including those who may be homeless, but it has been adjusted by using landlines and cell phones so approximately 95% of the population is covered. The assessment of ACEs in only five states may also limit generalizability to individuals in states and regions of the U.S. that have used the ACE module. However, prevalence of diabetes in the population used in the analysis was similar to the US population with 8.4% of those responding to the ACE module reporting diabetes, compared to 9.4% of the population being diagnosed as reported by the CDC [8]. Finally, this study used cross-sectional data so results suggest a potential pathway and cannot be causal; more longitudinal studies are needed in order to determine temporality which may offer further support for causality. The current findings represent an initial step in understanding how specific ACEs may influence the development of diabetes through underlying mechananisms. Additional ACE categories known to be associated with diabetes represent a next step in understanding the broad influence of ACEs and diabetes.

Implications for Policy and Public Health

The overall prevalence of ACEs and the magnitude of effect linking sexual abuse to diabetes is a public health crisis. As diabetes is currently the seventh leading cause of death in the U.S. and affects more than 29 million people of the total U.S. population [7], public health measures are needed to effectively understand and address the co-occurrence of sexual abuse and diabetes. Intervening with primary prevention before sexual abuse occurs, secondary prevention to screen and provide needed care, and tertiary prevention in individuals with a history of sexual abuse will allow for the development of interventions to disrupt the onset of health conditions such as depression and obesity that may lead to diabetes later in life. Primary prevention is key to lowering the occurrence of ACEs and sexual abuse overall in at risk individuals through educating health professionals, targeting policy development and implementation, and community engagement initiatives [15]. Secondary prevention is needed to screen and effectively intervene where individuals have already experienced sexual abuse, but where the health impact has not become manifest in chronic disease. For example, a recent study tested feasibility of routine screening in primary care visits to allow for development of a more comprehensive treatment plan that would account for the role of ACEs in disease management [34]. Additionally, intervention development to prevent depression in young adults with a history of sexual abuse to disrupt the development of depression or obesity could lower the incidence of diabetes. Future public health initiatives focusing on raising awareness and educating the general public on the potential pathway between sexual abuse and diabetes may encourage screening and individuals to seek additional treatment. Finally, tertiary prevention for individuals who have experienced sexual abuse and are being impacted by the health effects of the abuse would be of great importance to the improvement of disease outcomes that are related to the occurrence of sexual abuse as well as improvement in quality of life, for example decreasing diabetes complications. Utilization of a multifaceted approach to treat depression, and increase physical activity in patients with diabetes who have a history of sexual abuse will address both components of the mechanism found in this study. For example, understanding that sexual abuse may be a risk factor for diabetes via depression and obesity, lowering the threshold for diabetes screening in the primary care setting may be warranted among populations with a history of sexual abuse.

This study indicated that in some individuals, diabetes may be occurring because of childhood sexual abuse. Further, development of diabetes for these individuals may be due to depression and obesity resulting from that abuse. However, further investigation using longitudinal study designs to determine the temporal pattern of this relationship is needed. Understanding the inter-relationship between these two mechanisms and sexual abuse would allow for a better understanding of how obesity and depression link sexual abuse to the development of diabetes, and further guide public health interventions. Overall, effectively establishing public health programs that address the impact that sexual abuse has on the development of diabetes necessitates that the pathways and underlying mechanisms of this relationship be further elucidated.

Highlights.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) increase risk for diabetes in adulthood.

Among adults with diabetes, 11.6% experienced sexual abuse

Sexual abuse increases odds of diabetes by approximately 40%

Obesity and depression significantly mediated the pathway between sexual abuse and diabetes.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant K24DK093699, Principal Investigator: Leonard Egede, MD).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JAC was a major contributor in writing and interpreting the manuscript. LEE analyzed and interpreted the data in this manuscript. GF and SNR were major contributors in writing the manuscript. RJW was a major contributor in interpreting the data in this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Guarantors

LEE, JAC and RWJ are the guarantors of this work and take full responsibility for the work as a whole, including the study design, access to data, and the decision to submit and publish the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Felitti V, Anda R, Nordenberg D, Williamson D, Spitz A, Edwards, … Marks J. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experience study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–58. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Violence Prevention: Adverse childhood experiences. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang H, Yan P, Shan Z, Chen S, Li M, Luo C, … Liu L. Adverse childhood experiences and risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism. 2015;64:1408–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monnat SM, Chandler RF. Long-term physical health consequences of adverse childhood experiences. Sociol Q. 2015;56:723–752. doi: 10.1111/tsq.12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shields ME, Hovdestad WE, Pelletier C, Dykxhoorn JL, O’Donnell SC, Tonmyr L. Childhood maltreatment as a risk factor for diabetes: findings from a population-based survey of Canadian adults. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:879. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3491-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felitti VJ. Adverse childhood experiences and adult health. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:131–2. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman EM, Montez JK, Sheehan CM, Guenewald TL, Seeman TE. Childhood Adversities and Adult Cardiometabolic Health: Does the quantity, timing, and type of adversity matter? J Aging Health. 2015;27:1311–1338. doi: 10.1177/0898264315580122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozieh MN, Bishu KG, Dismuke CE, Egede LE. Trends in health care expenditure in U.S. adults with diabetes: 2002–2011. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1844–1851. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyle J, Thompson T, Gregg E, Barker L, Williamson D. Projections of the year 2050 burden of diabetes in the US adult population: Dynamic modeling of incidence, mortality, and prediabetes prevalence. Popul Health Metr. 2010;8:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-8-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell JA, Walker RJ, Egede LE. Associations between adverse childhood experiences, high risk behaviors, and morbidity in adulthood. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:344–352. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan AE, Auslander WF, Bucholz KK, Hudson DL, Stein RI, White NH. Relationship between abuse and neglect in childhood and diabetes in adulthood: Differential effects by sex, national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E70. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.140434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunningham TJ, Ford ES, Croft JB, Merrick MT, Rolle IV, Giles WH. Sex-specific relationships between adverse childhood experiences and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five states. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2014;9:1033–1042. doi: 10.2147/copd.s68226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong M, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williams JE, Chapman DP, Anda RF. Insights into causal pathways for ischemic heart disease: Adverse childhood experiences study. Circulation. 2004;110:1761–1766. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000143074.54995.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, McGuinn L. Committee on early childhood, adoption, and dependent care. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e232–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertone-Johnson ER, Whitcomb BW, Missmer SA, Karlson EW, Rich-Edwards JW. Inflammation and early-life abuse in women. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:611–620. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coelho R, Viola TW, Walss-Bass C, Brietzke E, Grassi-Oliveira R. Childhood maltreatment and inflammatory markers: A systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;129:180–192. doi: 10.1111/acps.12217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis CR, Dearing E, Usher N, Trifiletti S, Zaichenko L, Ollen, … Crowell JA. Detailed assessments of childhood adversity enhance prediction of central obesity independent of gender, race, adult psychosocial risk and health behaviors. Metabolism. 2014;63:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis CR, Usher N, Dearing E, Barkai AR, Crowell-Doom C, Neupert SD, … Crowell JA. Attachment and the metabolic syndrome in midlife: the role of interview-based discourse patterns. Psychosom Med. 2014;76:611–621. doi: 10.1097/psy.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System: 2011 Survey Data Information. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mokdad AH, Stroup DF, Giles WH. Public health surveillance for behavioral risk factors in a changing environment: recommendations from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance team. MMWR. 2003;52(RR-9):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newschaffer CJ. Validation of behavioral risk factor surveillance system HRQOL measures in a statewide sample. Prevention Research Center at Saint Louis University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Overweight and Obesity, 2016. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schumacker RE, Lomax RG. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling: Third Edition. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis Group; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: The Guildford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rich-Edwards JW, Spiegelman D, Hibert E, Jun H, Todd T, Kawachi I, Wright RJ. Abuse in childhood and adolescence as a predictor of type 2 diabetes in adult women. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2010;39:529–536. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Axon RN, Gebregziabher M, Hunt KJ, Lynch CP, Payne E, Walker RJ, Egede LE. Comorbid depression is differentially associated with longitudinal medication nonadherence by race/ethnicity in patients with type 2 diabetes. Medicine. 2016;95:e3983. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egede LE, Ellis C. Diabetes and depression: Global perspectives. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Everson SA, Saty SC, Lynch JW, Kaplan GA. Epidemiologic evidence for the relation between socioeconomic status and depression, obesity, and diabetes. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:8913. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00303-3. os. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Musselman DL, Betan E, Larson H, Phillips LS. Relationship of depression to diabetes type1 1 and 2: Epidemiology, biology, and treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:317–329. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wadden T. Impact of intensive lifestyle intervention on depression and health-related quality of life in type 2 diabetes: The look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:1544–1544. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edwards WS, Winn DM, Kurlantzick V, Sheridan S, Berk ML, Retchin S, Collins JG. Vital health statistics 2: Evaluation of National Health Interview Survey diagnostic reporting. 1994 Retrieved from National Center for Health Statistics. website: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_120.pdf. [PubMed]

- 33.Bowlin SJ, Morrill BD, Nafziger AN, Lewis C, Pearson TA. Reliability and changes in validity of self-reported cardiovascular disease risk factors using dual response: The behavioral risk factor survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:511–517. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glowa P, Olson A, Johnson DJ. Screening for adverse childhood experiences in a family medicine setting: A feasibility study. JABFM. 2016;29:303–307. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2016.03.150310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]