Abstract

A novel mild, visible-light-induced palladium-catalyzed hydrogen atom translocation/atom-transfer radical cyclization (HAT/ATRC) cascade has been developed. This protocol involves a 1,5-HAT process of previously unknown hybrid vinyl palladium radical intermediates, thus leading to iodomethyl carbo- and heterocyclic structures.

Keywords: cyclizations, hydrogen-atom transfer, palladium, photochemistry, radicals

A rad transfer

A novel mild, visible-light-induced palladium-catalyzed hydrogen atom translocation/atom-transfer radical cyclization (HAT/ATRC) cascade has been developed. This protocol involves a 1,5-HAT process of previously unknown hybrid vinyl palladium radical intermediates, thus leading to iodomethyl carbo- and heterocyclic structures.

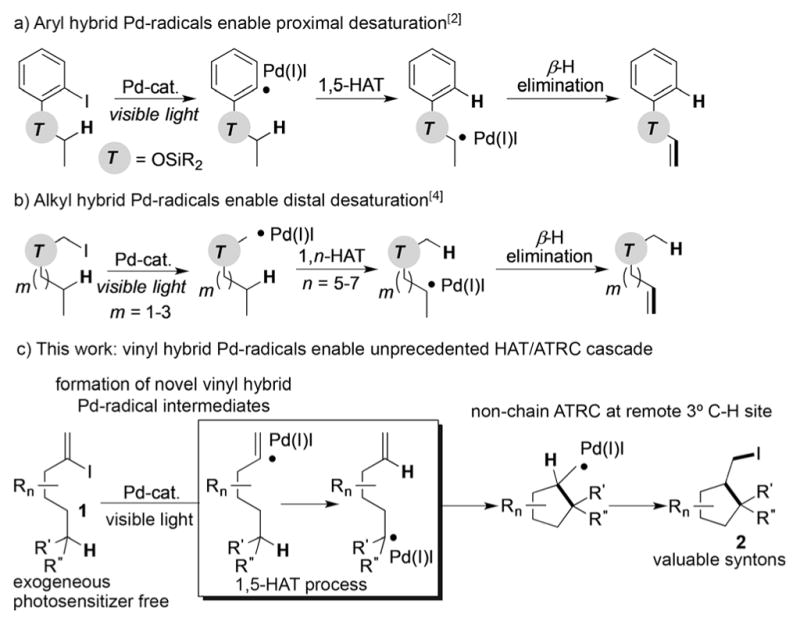

Transformations involving translocation of radical intermediates by hydrogen-atom transfer (HAT) have received much attention over the past few years as a highly regioselective and mild approach toward functionalization of remote C(sp3)–H bonds.[1] Recently, our group reported a HAT process triggered by a hybrid aryl palladium radical intermediate (Scheme 1a).[2] Induced by visible light, these aryl palladium radical species underwent a 1,5-HAT step followed by the β-H elimination to generate silyl enol ethers in an efficient manner. Expanding this strategy by utilizing hybrid alkyl palladium radical species[3] led to the development of a method for remote desaturation of alcohols at unactivated C(sp3)–H sites (Scheme 1b).[4] Based on the ability of these hybrid palladium radical species to activate C–H bonds by a HAT process, we were eager to investigate the possibility of achieving a HAT process with vinyl hybrid palladium radical intermediates as a platform for development of new transformations. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports on the generation and reactivity of vinyl hybrid palladium radical intermediates.[5] Herein, we report a mild, visible-light-induced exogenous photosensitizer free[6,7] formation of novel hybrid vinyl palladium radical species which trigger a HAT process at unactivated C(sp3)–H sites[8]/non-chain atom-transfer radical cyclization sequence to produce valuable iodoalkyl carbo- and heterocycles (Scheme 1c).

Scheme 1.

Hydrogen atom translocation of hybrid palladium radical intermediates.

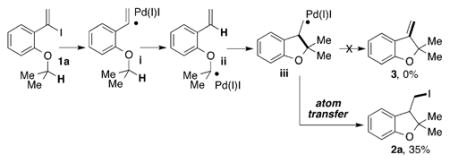

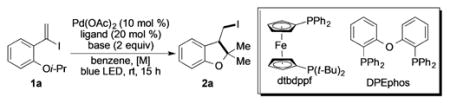

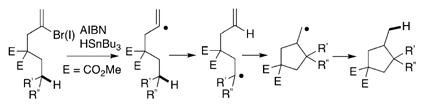

Curran and Shen disclosed translocation of vinyl radicals, which, under standard tin hydride conditions, enabled reductive formation of methylcyclopentane cores by a sequential 1,5-HAT/5-exo-trig cyclization.[9] Inspired by this work, we aimed at developing an oxidative version of this transformation toward methylenecyclopentane fragments [Eq. (1)]. The proposed sequence presumed formation of a hybrid vinyl palladium intermediate (1a→i), followed by its transposition (i→ii), cyclization (ii→iii), and a β-H elimination (iii→3). However, reaction of the benchmark substrate 1a under our previously employed conditions[2] did not result in formation of the expected Heck type-product 3, instead, the iodomethyl dihydrobenzofuran 2a was produced selectively. Apparently, the latter is a product of an unprecedented HAT/ATRC-type cascade reaction involving activation of the C(sp3)–H bond.[10,11]

|

(1) |

Inspired by the discovery of a new HAT/ATRC reaction [Eq. (1)], and motivated by the importance of iodomethyl cyclopentane derivatives,[12] we commenced investigation of this interesting transformation. First, optimization of the reaction conditions, employing 1a, was conducted (Table 1). It was found that this reaction proceeded more efficiently at higher dilution, thus producing 2 a in 51% yield (entry 3). Employment of sterically demanding tertiary amines (Cy2NMe) was equally efficient when compared to Cs2CO3 (entry 5). Switching to more bulky amines or other inorganic bases, however, played a detrimental role (see Table S2 in the Supporting Information). Different palladium sources exhibited minor effects on the outcome of this reaction, thus producing the products in nearly equal amounts (see Table S3). Extensive ligand screening proved DPEphos as the ligand of choice (Table 1, entry 6). Surprisingly, except for dtbdppf, neither the parent dppf (entry 7), nor any of its derivatives (see Table S4) produced appreciable amounts of the product.[13] Commonly for radical chemistry,[1] benzene proved to be the best among variety of solvents tested (see Table S5). Employment of degassed benzene (Table 1, entry 8), as well as lowering the amount of the base (entry 9), led to further improvement of the yield. Performing the reaction under standard free-radical conditions[9] delivered no target product (see Table S6). Finally, control experiments indicated that both light and the catalyst are vital for this transformation (Table 1, entries 10–12).

Table 1.

Optimization of reaction conditions.[a]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | [M] | Base | Ligand | Yield [%][b] |

| 1 | 0.02 | Cs2CO3 | dtbdppf | 35 |

| 2 | 0.05 | Cs2CO3 | dtbdppf | 5 |

| 3 | 0.01 | Cs2CO3 | dtbdppf | 51 |

| 4 | 0.01 | iPr2NEt | dtbdppf | 42 |

| 5 | 0.01 | Cy2NMe | dtbdppf | 53 |

| 6 | 0.01 | Cy2NMe | DPEphos | 55 |

| 7 | 0.01 | Cy2NMe | dppf | nr |

| 8 | 0.01 | Cy2NMe | DPEphos | 64[c] |

| 9 | 0.01 | Cy2NMe | DPEphos | 71,[c,d] (69[e]) |

| 10 | 0.01 | Cy2NMe | DPEphos | 0[f] |

| 11 | 0.01 | Cy2NMe | DPEphos | 7[g] |

| 12 | 0.01 | Cy2NMe | DPEphos | decomp[h] |

All reactions were performed on a 0.05 mmol scale.

GC/MS yields.

Degassed benzene was used.

1 equivalent of Cy2NMe was used.

Yield of isolated product.

In dark.

No Pd(OAc)2 was used.

90°C, no light.

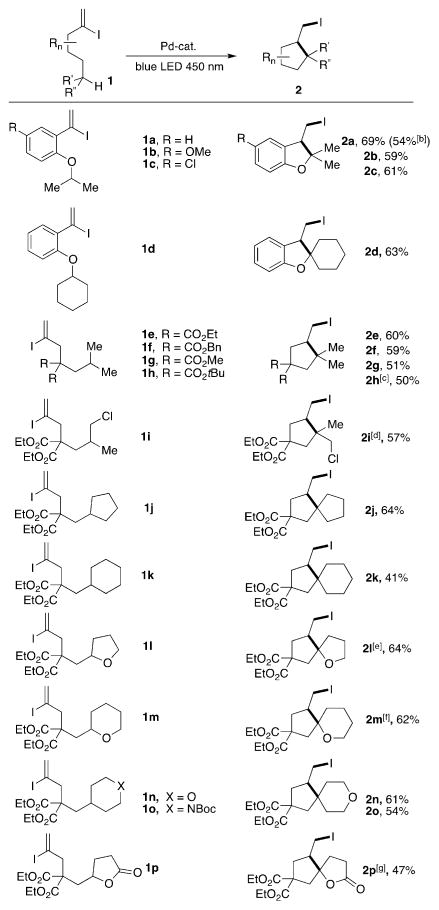

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, the scope of this transformation was explored (Table 2). Reaction of electronically diverse iodovinylbenzyl derivatives (1a–c) provided the corresponding iodomethyl dehydrobenzofurans (2a–c) in good yield. Scaling up this reaction to 1 mmol provided comparable yield of 2a. Replacing the isopropyl group with a cyclohexyl group led to the spirocyclic derivative 2d in reasonable yield. Next, we were eager to probe this methodology on linear aliphatic systems toward assembly of an important cyclopentyl core. Gratifyingly, acyclic precursors proved to be competent reactants leading to the formation of a variety of iodomethyl cyclopentyl derivatives. Substrates, possessing various ester substituents at the carbon tether were nearly as equally efficient (2e–h). Notably, the substrate 1i, bearing a pendant chlorine atom, smoothly underwent reaction to produce the dihalogenated 2i in 57% yield, albeit as the mixture of diastereomers. Markedly, substrates possessing cycloalkyl groups reacted smoothly, thus producing 5/5- (2j) and 5/6- (2k) spirocyclic molecules in 64 and 41% yield, respectively. Importantly, employment of substrates, possessing a heterocyclic substituent [tetrahydrofuryl- (1l) or tetrahydropyranyl- (1m)] with a heteroatom adjacent to the C–H abstraction site reacted diastereoselectively, thus producing the iodomethyl-containing spiroheterocycles 2l,m in good yields. Reaction of substrates, possessing 4-susbtituted tetrahydropyran and piperidine led to efficient formation of the spiroheterocyclic molecules 2 n,o. Finally, a cascade reaction of the γ-butyrolactone-containing substrate led to a valuable spirolactone core[14] (2p) in 47% yield.

Table 2.

Scope of HAT/ATRC cascade reaction.[a]

Reaction conditions: 1 0.1 mmol, Pd(OAc)2 0.01 mmol, DPEphos 0.02 mmol, Cy2NMe 0.1 mmol, benzene 0.01 M, 34 W blue LED.

1 mmol scale reaction.

Yield determined by NMR spectroscopy.

1.1:1 d.r.

5.3 (trans):1 d.r.

Single diastereomer (trans).

1.2:1 d.r.

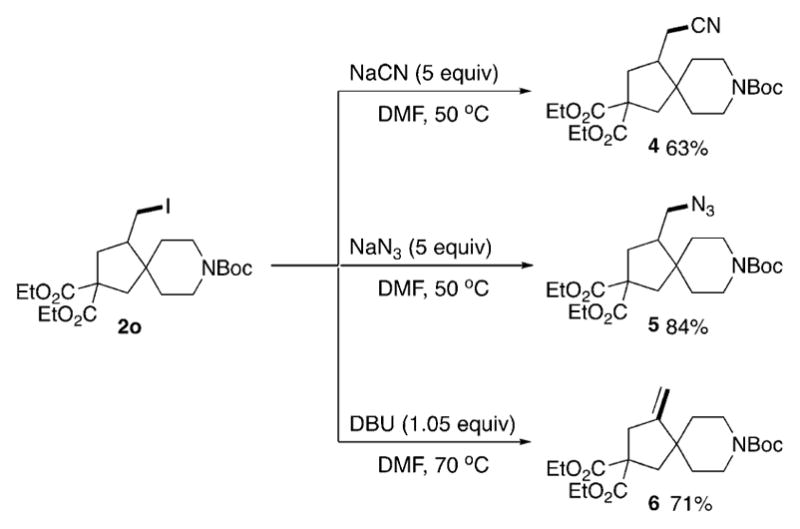

Apparently, the presence of an iodomethyl moiety in the products of the HAT/ATRC cascade provides a convenient handle for further modification. Indeed, nucleophilic substitution of the iodide in 2o with cyanide and azide groups resulted in 4 and 5, respectively, in good yields (Scheme 2). Alternatively, base-mediated elimination of HI provided the exo-methylene-containing spiroheterocycle 6 in 71% yield.

Scheme 2.

Further transformations of HAT/ATRC cascade products. Boc = tert-butoxycarbonyl, DBU = 1,8-diazabicyclo[5-4-0]undec-7-ene, DMF = N,N-dimethylformamide.

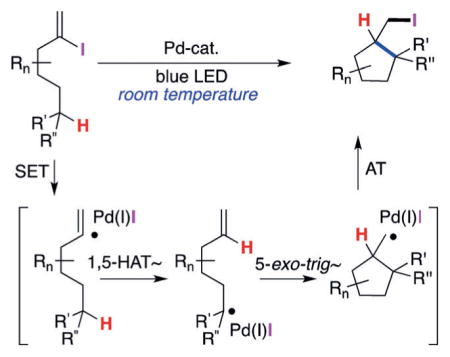

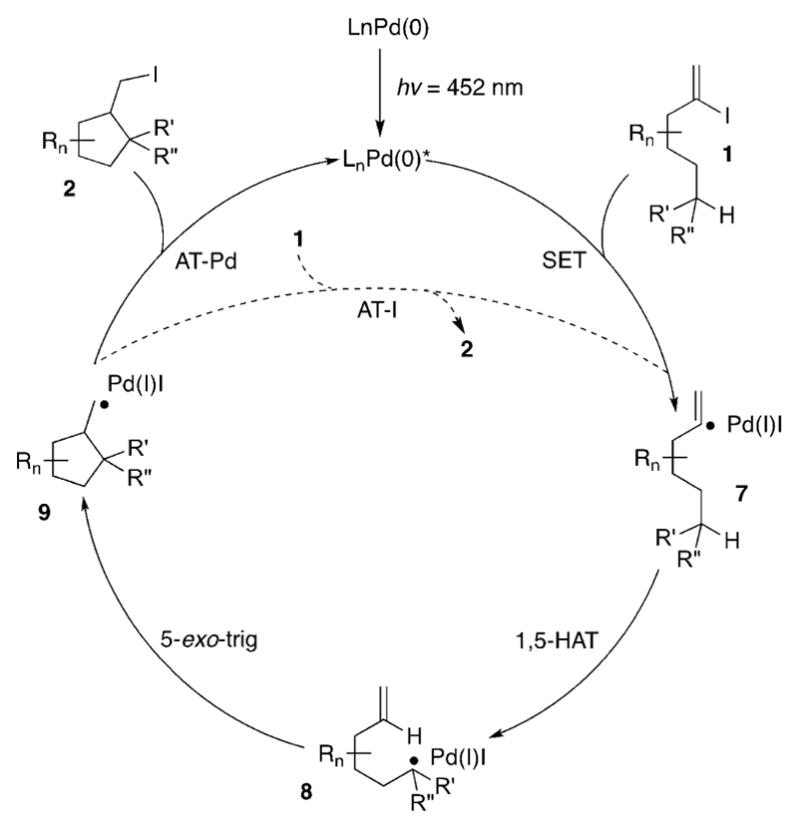

We propose the following mechanism for this novel HAT/ATRC cascade transformation (Scheme 3). The active photo-excited[15] Pd0 complex undergoes a single-electron transfer (SET) with 1 to produce, upon homolysis of the C–I bond, the hybrid vinyl palladium radical intermediate 7. The latter, upon 1,5-HAT generates the tertiary alkyl hybrid palladium radical 8, which upon 5-exo-trig cyclization forms the primary alkyl radical species 9. A subsequent iodine-atom transfer from the putative PdII species to 9 furnishes the product 2 and regenerates the Pd0 catalyst.[16] The radical nature of this transformation was confirmed by radical trap and deuterium-labeling experiments.[17] The UV-vis analysis indicated that the Pd0 complex is the photoabsorbing species. Alternatively, a radical-chain mechanism could be operative,[18] where the palladium catalyst and light would only be needed for the initiation step of the reaction (1→9). Then, an atom-transfer chain reaction (AT-I) between 9 and 1 (9 + 1 → 2 + 7) would propagate the process. However, because of the unfavorable bond dissociation energies (BDEs) of the C–I bonds in vinyl versus alkyl iodides,[19] this scenario is unlikely.

Scheme 3.

Proposed mechanism for HAT/ATRC cascade.

In summary, we have shown that exposure of vinyl iodides to a palladium catalyst and visible light in the absence of exogenous photosensitizers at room temperature leads to formation of a novel vinyl hybrid palladium radical species. This intermediate triggers a novel 1,5-HAT/non-chain ATRC cascade reaction to form valuable iodomethyl-containing cyclopentanes, as well as spiroannulated cyclopentanes with carbo- and heterocycles. The iodomethyl functionality in the formed reaction products can easily be further functionalized. It is believed that the discovery of novel reactivity of vinyl halides under visible-light/palladium-catalyzed conditions would trigger the elaboration of new methods, and that the developed methods would find applications in synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM120281) and the National Science Foundation (CHE-1663779).

Footnotes

Supporting information and the ORCID identification number(s) for the author(s) of this article can be found under: https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201712775.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.For selected reviews, see: Nechab M, Mondal S, Bertrand MP. Chem Eur J. 2014;20:16034–16059. doi: 10.1002/chem.201403951.Sperry J, Liu YC, Brimble MA. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:29–38. doi: 10.1039/b916041h.Cekovic Z. J Serb Chem Soc. 2005;70:287–318.Robertson J, Pillai J, Lush RK. Chem Soc Rev. 2001;30:94–103.Majetich G, Wheless K. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:7095–7129.Renaud P, Sibi MP. Radicals in Organic Synthesis. Vol. 2. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2001. ; For recent examples, see: Green SA, Matos JLM, Yagi A, Shenvi RA. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:12779–12782. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b08507.Obradors CL, Martinez R, Shenvi RA. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:4962–4971. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02032.Wappes EA, Nakafuku KM, Nagib DA. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:10204–10207. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b05214.Wappes EA, Fosu SC, Chopko TC, Nagib DA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:9974–9978. doi: 10.1002/anie.201604704.Angew Chem. 2016;128:10128–10132.Choi GJ, Zhu Q, Miller DC, Gu CJ, Knowles RR. Nature. 2016;539:268–271. doi: 10.1038/nature19811.Chen DF, Chu JCK, Rovis T. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:14897–14900. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b09306.Chu JCK, Rovis T. Nature. 2016;539:272–275. doi: 10.1038/nature19810.Liu T, Myers MC, Yu JQ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:306–309. doi: 10.1002/anie.201608210.Angew Chem. 2017;129:312–315.Liu T, Mei TS, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:5871–5874. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b02065.Wang YF, Chen H, Zhu X, Chiba S. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:11980–11983. doi: 10.1021/ja305833a.Shu W, Nevado C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:1881–1884. doi: 10.1002/anie.201609885.Angew Chem. 2017;129:1907–1910.Hollister KA, Conner ES, Spell ML, Deveaux K, Maneval L, Beal MW, Ragains JR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:7837–7841. doi: 10.1002/anie.201500880.Angew Chem. 2015;127:7948–7952.

- 2.Parasram M, Chuentragool P, Sarkar D, Gevorgyan V. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:6340–6343. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b01628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For selected examples, see: Kurandina D, Parasram M, Gevorgyan V. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:14212–14216. doi: 10.1002/anie.201706554.Angew Chem. 2017;129:14400–14404.Parasram M, Iaroshenko VO, Gevorgyan V. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:17926–17929. doi: 10.1021/ja5104525.Sumino S, Ryu I. Org Lett. 2016;18:52–55. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03238.Sumino S, Ui T, Hamada Y, Fukuyama T, Ryu I. Org Lett. 2015;17:4952–4955. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02302.Zhou WJ, Cao GM, Shen G, Zhu XY, Gui YY, Ye JH, Sun L, Liao LL, Li J, Yu DG. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:15683–15689. doi: 10.1002/anie.201704513.Angew Chem. 2017;129:15889–15893.Wang GZ, Shang R, Cheng WM, Fu Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:18307–18312. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b10009.. For reviews, see: Jahn U. Top Curr Chem. 2012;320:323–452. doi: 10.1007/128_2011_288.Liu Q, Dong X, Li J, Xiao J, Dong Y, Liu H. ACS Catal. 2015;5:6111– 6137.

- 4.Parasram M, Chuentragool P, Wang Y, Shi Y, Gevorgyan V. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:14857–14860. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b08459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.For free-radical generation of vinyl radicals, see: Dénès F, Beaufils F, Renaud F. Synlett. 2008:2389–2399.Gloor CS, Denes F, Renaud F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:13329–13332. doi: 10.1002/anie.201707791.Angew Chem. 2017;129:13514–13517.Huang L, Ye L, Li XH, Li ZL, Lin JS, Liu XY. Org Lett. 2016;18:5284–5287. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02599.Sharma GVM, Chary DH. Synth Commun. 2014;44:1771–1779.Lamarque C, Beaufils F, Denes F, Schenk K, Renaud F. Adv Synth Catal. 2011;353:1353–1358.; For recent examples on transition-metal-catalyzed generation of vinyl radicals, see: Cannillo A, Schwantje TR, Begin M, Barabe F, Barriault L. Org Lett. 2016;18:2592–2595. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00968.Paria S, Reiser O. Adv Synth Catal. 2014;356:557– 562.

- 6.For selected reviews, see: Prier CK, Rankic DA, MacMillan DWC. Chem Rev. 2013;113:5322–5363. doi: 10.1021/cr300503r.Skubi KL, Blum TR, Yoon TP. Chem Rev. 2016;116:10035–10074. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00018.Romero NA, Nicewicz DA. Chem Rev. 2016;116:10075–10166. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00057.Staveness D, Bosque I, Stephenson CRJ. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49:2295–2306. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00270.Tellis JC, Kelly CB, Primer DN, Jouffroy M, Patel NR, Molander GA. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49:1429–1439. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00214.Meggers E. Chem Commun. 2015;51:3290–3301. doi: 10.1039/c4cc09268f.Xie J, Jin H, Hashmi ASK. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46:5193– 5203. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00339k.

- 7.For a review on visible-light-induced transition-metal-catalyzed transformations proceeding without exogenous photosensitizers, see: Parasram M, Gevorgyan V. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46:6227–6240. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00226b.

- 8.For a recent review on palladium-catalyzed functionalizations of aliphatic C–H bonds, see: He J, Wasa M, Chan KSL, Shao Q, Yu J-Q. Chem Rev. 2017;117:8754–8786. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00622.

-

9.Curran DP, Shen W. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:6051–6059.

- 10.Most established palladium-catalyzed ATRC protocols employing alkyl halide precursors operate by a radical chain mechanism. Moreover, the active palladium species were found to serve as initiators rather than a catalyst. For selected references, see: Curran DP, Chang CT. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:933–936.Mori M, Kubo Y, Ban Y. Tetrahedron. 1988;44:4321–4330.Mori M, Kanda N, Ban Y, Aoe K. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1988:12–14.Mori M, Kubo Y, Ban Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:1519–1522.Mori M, Oda I, Ban Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:5315–5318.Liu H, Qiao Z, Jiang X. Org Biomol Chem. 2012;10:7274–7277. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25990g.Monks BM, Cook SP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:14214–14218. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308534.Angew Chem. 2013;125:14464–14468.

- 11.Although palladium-catalyzed ATRC radical cyclizations of alkyl halides are much more developed, a few reports on the employment of aryl or vinyl halides have been reported. However, these methods typically employ high reaction temperatures and substrates that lack β-hydrogen atoms (postcyclization). For a review, see: Petrone DA, Ye J, Lautens M. Chem Rev. 2016;116:8003–8104. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00089.; For selected examples, see: Newman SG, Lautens M. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1778–1780. doi: 10.1021/ja110377q.Newman SG, Howell JK, Nicolaus N, Lautens M. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:14916–14919. doi: 10.1021/ja206099t.Lan Y, Liu P, Newman SG, Lautens M, Houk KN. Chem Sci. 2012;3:1987–1995.Petrone DA, Malik HA, Clemenceau A, Lautens M. Org Lett. 2012;14:4806–4809. doi: 10.1021/ol302111y.Petrone DA, Lischka M, Lautens M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:10635–10638. doi: 10.1002/anie.201304923.Angew Chem. 2013;125:10829–10832.Liu H, Li C, Qiu D, Tong X. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:6187– 6193. doi: 10.1021/ja201204g.

- 12.a) Talele TT. J Med Chem. 2017 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00315.; b Okada M, Matsuda Y, Mitsuhashi T, Hoshino S, Mori T, Nakagawa K, Quan Z, Qin B, Zhang H, Hayashi F, Kawaide H, Abe I. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:10011–10018. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b05799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Schneider S, Provasi D, Filizola M. Biochemistry. 2016;55:6456–6466. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Gernet DL, Grese TA, Belvo MD, Borromeo PS, Kelley SA, Kennedy JH, Kolis SP, Lander PA, Richey R, Sharp VS, Stephenson GA, Williams JD, Yu H, Zimmerman KM, Steinberg MI, Jadhav PK, Bell MG. J Med Chem. 2007;50:6443– 6445. doi: 10.1021/jm701186z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.At this point, the reasons of the observed ligand effect on this reaction are not clearly understood.

- 14.a) Qin B, Li Y, Meng L, Ouyang J, Jin D, Wu L, Zhang X, Jia X, You S. J Nat Prod. 2015;78:272–278. doi: 10.1021/np500864e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Leverett CA, Purohit VC, Johnson AG, Davis RL, Tantillo DL, Romo D. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:13348– 13356. doi: 10.1021/ja303414a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen TL, Kramer S, Overgaard J, Skrydstrup T. Organometallics. 2017;36:2058–2066. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Although the exact role of base in this transformation is not completely understood, it may prevent formation of the catalytically inactive PdI2 species (see Ref. [10g]).

- 17.See the Supporting Information for details.

- 18.Studer A, Curran DP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:58–102. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2016;128:58–106. [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Luo YR. Comprehensive Handbook of Chemical Bond Energies. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2007. [Google Scholar]; b) Blanksby SJ, Ellison GB. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:255–263. doi: 10.1021/ar020230d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.