Background

Public Health Concern

Dizziness and vertigo are responsible for an estimated 4.4 million emergency department (ED) visits in the United States each year, and account for 4% of chief symptoms in the ED.1 Strokes are the underlying cause of about 3-5% of such visits (130,000–220,000).2 These visits are associated with a high cost, estimated now to exceed $10 billion per year in the US.3 This results from neuroimaging obtained in roughly half the patients1 and admissions for nearly 20%.4 ED physicians worldwide rank vertigo a top priority for developing better diagnostic tools.5 An evidence-based, cost-effective approach to diagnosing acute dizziness and vertigo is needed.

Diagnostic Errors

Improving diagnosis is recognized by the National Academy of Medicine as a public health priority.6 Nearly 10% of strokes are misdiagnosed at first medical contact.7 Of the approximately 130,000-220,000 patients with stroke presenting with vertigo or dizziness to the ED, it is estimated that perhaps 45,000-75,000 are initially missed,3 with misdiagnosis disproportionately affecting the young (age <50), women, and minorities.8,9 Atzema et al.10 found that patients discharged from the ED said to have benign dizziness are at 50-fold increased risk of a stroke hospitalization in the 7 days post-discharge relative to propensity score-matched controls.10 Another population-based registry showed that 90% of isolated posterior circulation TIAs, half presenting isolated vertigo symptoms, were not recognized at first medical contact.11 Overall, dizziness and vertigo are the symptoms most tightly linked to missed stroke.7,9

Given their low sensitivity (7-16%),12 CT scans are of little use for identifying acute ischemic strokes,13 particularly in the posterior fossa.12 Despite this, nearly 50% of US ED patient presenting dizziness are imaged by CT, and fewer than 3% by MRI.1 Even MRI with diffusion weighted imaging (MRI-DWI), misses ~15-20%12 of acute posterior fossa infarctions <24-48 hours from symptom onset.12 One study suggests perhaps even a higher fraction (~50%, n=8/15) are missed by MRI-DWI when these strokes are small (<1 cm in diameter);14 but “small” does not mean “benign,” since half of these patients had large-artery stenosis or dissection, increasing recurrent stroke risk.15 Obtaining MRI for every patient presenting with ED dizziness in the US would be time consuming and cost more than $1 billion annually, making it unrealistic.3

Harms related to missed stroke accrue from missed opportunities for acute thrombolysis,8 early secondary prevention,16,17 and surgical treatment of stroke complications from malignant edema.18 Small studies have suggested a high risk of permanent morbidity (33%, n=5/15]) and mortality (40%, n=6/15) among those whose cerebellar strokes were initially missed,19 much higher than what is reported in large cohorts with cerebellar infarction (5%, n=15/282).20 While these may be overestimates, it is clear that delayed stroke diagnosis increases morbidity and mortality substantially.7 One estimate suggests that with strokes presenting dizziness and vertigo, 15,000-25,0003 suffer serious and potentially preventable harms from the initial misdiagnosis.3

These numbers indicate that our current diagnostic practices in the ED are largely ineffective21 and there is substantial room for improvement.22,23 In addition to problems with stroke, many acutely dizzy patients with peripheral vestibular causes for their symptoms are over-tested, misdiagnosed, and undertreated.21 The costs of unnecessary imaging and hospital admissions for these patients waste an estimated $1 billion each year.3 Thus, accurate and efficient diagnosis for these patients will likely save lives and reduce costs through prompt and appropriate treatments.4

Causes of Diagnostic Errors

When evaluating dizziness, physicians seek to differentiate inner ear conditions from stroke or other central causes.24 Vestibular strokes are often missed because clinical findings mimic benign ear disorders. Because 95% or more of ED patients with dizziness do not have stroke, detecting these cerebrovascular cases presents an enormous challenge. Neuroimaging seems like a natural solution, but, as noted above, CT is ineffective and MRI is imperfect and too costly to apply to all ED dizziness. This means that accurate bedside diagnosis is at a premium.

The traditional approach to evaluating these patients places heavy emphasis on defining the “type” of dizziness25—vertigo [vestibular] vs. presyncope [cardiovascular] vs. disequilibrium [neurologic] vs. non-specific [psychiatric/metabolic].26 This approach, however, has been largely debunked.21 A recent study by Kerber et al.27 adds further confirmation against the “type” approach using data from a large national survey. On average, people with likely peripheral vestibular disorders complained of three different types of dizziness, and experienced vertigo as the primary type in just 25%.27 Frequent use of this faulty diagnostic paradigm26 combined with inadequate knowledge of bedside eye movement-based diagnosis, overreliance on vascular risk factors, and false reassurance by negative CT imaging to “rule out stroke”28 likely explains why missed strokes are more common than one would hope.21

In this manuscript, we describe an approach to bedside diagnosis derived from current best evidence that relies first on classifying acute vertigo or dizziness by timing (episodic vs. continuous) and trigger (positional vs. not), rather than type, and then uses that classification to hone in on specific, targeted bedside eye movement examinations to differentiate peripheral vs. central causes.2

Approach to Cerebrovascular Diagnosis

Symptom Definitions

Expert international consensus definitions for vestibular symptoms have been developed as part of the International Classification of Vestibular Disorders (ICVD).29 These define dizziness as “the sensation of disturbed or impaired spatial orientation without a false or distorted sense of motion” and vertigo as “the sensation of self-motion when no self-motion is occurring or the sensation of distorted self-motion during an otherwise normal head movement.29 In this manuscript we use these terms mostly interchangeably, since there is little diagnostic value in distinguishing between them.21

Timing, Triggers, and Targeted Exam (Ti.Tr.A.T.E.)

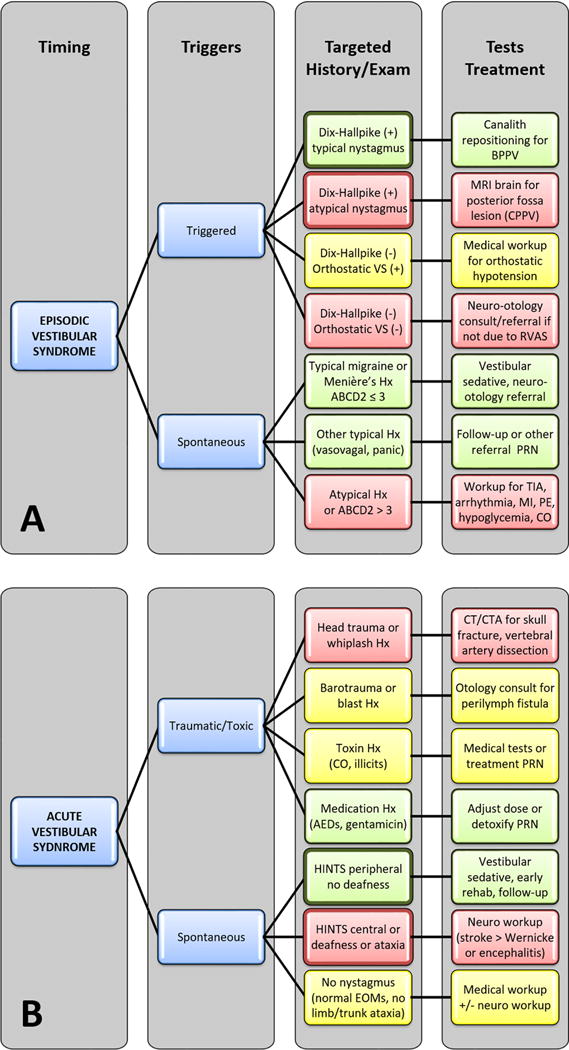

The TiTrATE acronym stands for timing, triggers, and targeted examinations.2 Timing refers to key aspects of onset, duration, and evolution of the dizziness. Triggers refer to actions, movements, or situations that provoke the onset of dizziness in patients who have intermittent symptoms. In the acute setting, a history based on timing and triggers in dizziness results in four possible syndromes in patients presenting in the ED with recent intermittent or continuous dizziness: triggered episodic vestibular syndrome (t-EVS), spontaneous episodic vestibular syndrome (s-EVS), traumatic/toxic acute vestibular syndrome (t-AVS), and spontaneous acute vestibular syndrome (s-AVS).2 Most TIAs present with s-EVS and most strokes or hemorrhages present with s-AVS, but there are exceptions (Table 1). To get to the correct cerebrovascular diagnosis, therefore, it is necessary for the practitioner to understand all four syndromes (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Cerebrovascular causes linked to four acute dizziness/vertigo syndromes

| Syndrome | TIA | Ischemic Stroke | Hemorrhage |

|---|---|---|---|

| t-EVS (brief, repetitive) | Rotational vertebral artery syndrome30 | CPPV from small ischemic strokes near the 4th ventricle31 | CPPV from small hemorrhages near the 4th ventricle32 |

| s-EVS (<24hrs) |

PICA – isolated vertigo AICA – vertigo +/- tinnitus or hearing loss |

Small ischemic strokes presenting transient symptoms33 | Subarachnoid hemorrhages mimicking TIA33 |

| t-AVS (>24hrs) | Overlap syndrome with trauma and vertebral artery dissection/TIA | Overlap syndrome with trauma and vertebral artery dissection/stroke | Overlap syndrome with trauma and traumatic hemorrhage (subdural, subarachnoid, etc.) |

| s-AVS (>24hrs) | Not yet reported |

PICA – isolated vertigo AICA – vertigo +/- tinnitus or hearing loss |

Small to medium-sized cerebellar hemorrhages |

Typeset: Common cerebrovascular presentations are shown in boldface type; the other combinations are rare. Abbreviations: AICA – anterior inferior cerebellar artery; PICA – posterior inferior cerebellar artery; s-AVS – spontaneous acute vestibular syndrome; s-EVS – spontaneous episodic vestibular syndrome; t-AVS – traumatic/toxic acute vestibular syndrome; t-EVS – triggered episodic vestibular syndrome

Figure 1.

Timing, triggers, and target examination (TiTrATE) approach to diagnosing dizziness and vertigo, highlighting cerebrovascular causes (red). Abbreviations: AED, antiepileptic drug; CO, carbon monoxide; EOM, extraocular movement; Hx, history; MI, myocardial infarction; PE, pulmonary embolus; PRN, pro re nata (as needed); VS, vital signs. Modified from, Neurol Clin. 33, Newman-Toker DE and Edlow JA, Titrate: A novel, evidence-based approach to diagnosing acute dizziness and vertigo, 577-599, viii 2015 with permission from Elsevier.2

Episodic Vestibular Syndrome

The episodic vestibular syndrome is defined as “a clinical syndrome of transient vertigo, dizziness, or unsteadiness lasting seconds to hours, occasionally days, and generally including features suggestive of temporary, short-lived vestibular system dysfunction (e.g., nausea, nystagmus, sudden falls).”34 There are triggered and spontaneous forms.

Triggered episodic vestibular syndrome (t-EVS)

Attacks usually last seconds to minutes. The most common triggers are head motion or change in body position (e.g., arising from a seated or lying position). Clinicians must distinguish triggers from exacerbating features, because movement of the head typically exacerbates any dizziness of vestibular cause whether benign vs. dangerous, central vs. peripheral, or acute vs. chronic.

In the ED, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is likely the second most common cause of t-EVS after orthostatic hypotension, accounting for approximately 5-10%35 of acute dizziness cases.36 The diagnosis is confirmed by canal-specific positional testing maneuvers and identifying a canal-specific nystagmus.37 BPPV of the posterior canal is the most common and produces a transient, crescendo-decrescendo upbeat-torsional nystagmus that lasts less than a minute. The second most common is BPPV affecting the horizontal canal, which produces a transient, usually brisk horizontal nystagmus that lasts less than 90 seconds. Patients with atypical nystagmus forms (e.g., persistent positional downbeat or horizontal nystagmus; no latency between the head reaching the target position during positional testing and nystagmus onset) may have mimics known as central paroxysmal positional vertigo (CPPV). CPPV may result from benign central causes, such as alcohol intoxication or vestibular migraine, but other cases are caused by posterior fossa structural lesions.38,39

Although t-EVS is only uncommonly due to cerebrovascular disease, there are two distinct forms. Small strokes or hemorrhages near the fourth ventricle sometimes cause CPPV.31,32,39 The nystagmus is usually horizontal, so differs from the most common (posterior canal) form of BPPV. The other triggered cerebrovascular syndrome is the rare condition known as rotational vertebral artery syndrome.30,40 Here, far lateral rotation of the neck leads to mechanical occlusion of one or both vertebral arteries,40 causing temporary symptoms of vertigo and nystagmus when the offending position is maintained.30 This occurs even with the patient upright, so is rarely confused for CPPV.

Spontaneous episodic vestibular syndrome (s-EVS)

The majority of spells in this category last minutes to hours. While there may be predisposing factors such as dehydration, sleeplessness, or specific foods, there are no obligate, immediate triggers. Because episodes are usually resolved at the time of assessment, examination is often normal and evaluation relies almost entirely on history taking. If symptoms are still present when the patient is being assessed, eye exam techniques for s-AVS, described below, can distinguish central from peripheral forms.41

Menière’s disease is sometimes considered the prototype cause of s-EVS, but vestibular migraine is the most common. Other benign causes include vasovagal presyncope and panic attacks. Principal dangerous causes are cerebrovascular (vertebro-basilar TIA), cardiorespiratory (especially cardiac arrhythmia), and endocrine (especially hypoglycemia). Cardiac arrhythmias should be considered in any patient with s-EVS, even if the presenting symptom is true spinning vertigo.42,43 On rare occasions, subarachnoid hemorrhage may present as s-EVS.33

Multiple studies show that dizziness and vertigo, even when isolated, are the most common premonitory vertebro-basilar TIA symptoms in the days to weeks preceding posterior circulation stroke.11,44 In a large population-based study, 51% (n=23/45) of premonitory vertebro-basilar TIAs presented with isolated vertigo, and 52% of these lasted longer than one hour, making them highly atypical for modern definitions of TIA.11,45 When TIAs affect the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) vascular territory, which supplies blood to the inner ear in most individuals,46 the symptoms may include recurrent vertigo with auditory symptoms that can mimic Menière’s disease.23,47 If seen during an attack, a patient with AICA-territory TIA may demonstrate unilateral sensorineural hearing loss and peripheral-type nystagmus from labyrinthine ischemia, so diagnostic caution is advised when hearing loss is present.48 Some s-EVS cases may show small strokes by MRI-DWI.49 Dizziness is also the most common presenting symptom of vertebral artery dissection (58%),50 which affects younger patients, mimics migraine, and is easily misdiagnosed.19 Vertebral artery dissection can be linked to minor neck injuries sustained during exertional sports, abnormal head postures, or chiropractic neck manipulation, but fewer than half of patients with dissection have such a history.50 While sudden, severe, or sustained headache or neck pain probably points to a vascular pathology,51 photophobia or phonophobia probably points to migraine.52

Acute Vestibular Syndrome

The acute vestibular syndrome (AVS) is defined as “a clinical syndrome of acute-onset, continuous vertigo, dizziness, or unsteadiness lasting days to weeks, and generally including features suggestive of new, ongoing vestibular system dysfunction (e.g., vomiting, nystagmus, postural instability).”34 It is important to note that patients experience worsening of AVS symptoms with any head motion during the attack. These exacerbating features must be distinguished from head movements that trigger dizziness.51 The way to differentiate the two is that a patient with t-EVS is largely asymptomatic at rest and specific head motions induce transient dizziness, whereas a patient with s-AVS is dizzy at rest and feels worse with any head motion.

Traumatic/Toxic Acute Vestibular Syndrome (t-AVS)

In patients with t-AVS, the key exposures are usually obvious, so there is less need for the exam to drive diagnostic decision-making. The most common causes are blunt head injury and drug intoxication, particularly with medications such as anticonvulsants or aminoglycoside antibiotics.2 Carbon monoxide poisoning should also be considered.53 Most patients experience a single, acute attack resolving gradually over days to weeks once the exposure has stopped. The principal cerebrovascular concern in such patients is an overlap syndrome in which a primary pathology (e.g., direct labyrinthine concussion from blunt head injury or alcohol intoxication with a fall) may mask a secondary pathology (e.g., vertebral artery dissection causing cerebellar infarction).

Spontaneous Acute Vestibular Syndrome (s-AVS)

As with patients with t-AVS, those with s-AVS are usually still symptomatic at the time of assessment. Since no obvious exposures are present in s-AVS (and exposures such as “recent viral syndrome” are non-specific), the bedside eye exam is the primary tool for differentiating between central and peripheral causes. The most common s-AVS etiology is vestibular neuritis. Approximately 10-20% of patients with s-AVS have stroke7,54 (typically in the brainstem or cerebellum, 95% ischemic7) as a cause. Sometimes these strokes occur after a series of spontaneous relatively short-lived dizziness episodes in the preceding weeks or months that likely reflect premonitory TIAs.55 Other dangerous causes include thiamine deficiency and listeria encephalitis.2

Strong evidence indicates that a three-part bedside ocular motor examination battery (HINTS—Head Impulse, Nystagmus Type, Skew deviation) plus acute hearing loss by finger rub (HINTS “plus”) rules out stroke more accurately than early MRI (Table 2).14,55-59 While it is possible for ED providers to learn these techniques,48 only a minority use them and even fewer are confident in these bedside skills.60 Skills also vary among neurologists.61 Widespread dissemination of these approaches may require the use of portable video-oculography devices to assist in training and feedback to providers.23

Table 2.

Pre-test and post-test probabilities of stroke using different tests to ‘rule out’ stroke in the spontaneous acute vestibular syndrome (s-AVS)

| Post-Test Probability of Stroke following a Negative Test Obtained in First 24 Hours | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Test Probability of Stroke (vascular risk profile) | General Neuro Exam (Sn 18.8%,56 Sp 95%, NLR 0.85) | CT Brain (Sn 16%,13 Sp 98%,13 NLR 0.86) |

MRI-DWI Brain (Sn 80.0%,62 Sp 96.0%,13 NLR 0.21) |

HINTS+ Battery (Sn 99.2%,63 Sp 97.0%, NLR 0.01) |

| 10% (low) | 8.7% | 8.7% | 2.3% | 0.1% |

| 25% (average62) | 22.2% | 22.3% | 6.5% | 0.3% |

| 50% (high) | 46.1% | 46.2% | 17.2% | 0.8% |

| 75% (very high) | 71.9% | 72.1% | 38.5% | 2.4% |

Abbreviations: CT – computed tomography; HINTS+ - head impulse, nystagmus, test of skew, plus hearing; MRI-DWI – magnetic resonance imaging with diffusion weighted imaging; NLR – negative likelihood ratio; Sn – sensitivity; Sp – specificity

Modified from Newman-Toker, et al., 2015 © Georg

Thieme Verlag KG.23

Details of how to perform these tests and associated videos are found elsewhere (Online Supplement). Of note, HINTS only applies to patients with s-AVS (or s-EVS while the patient remains acutely symptomatic41), including spontaneous or gaze-evoked nystagmus; HINTS should not be relied upon in patients who have other syndromes, particularly t-EVS, where normal head impulse test results would erroneously imply stroke in the majority with BPPV. Pitfalls and pearls in the diagnosis of stroke in acute dizziness and vertigo are described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Ten pitfalls and pearls in the diagnosis of stroke in acute dizziness and vertigo

| Pitfall | Pearl | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| “True” vertigo implies an inner ear disorder. | Focus on timing and triggers, rather than type. | Cerebrovascular disorders frequently present with “true” vertigo symptoms.64,65 |

| Worse with head movement implies peripheral. | Differentiate triggers from exacerbating factors. | Acute dizziness/vertigo is usually exacerbated by head movement, whether peripheral or central.51 |

| Auditory symptoms imply a peripheral etiology. | Beware auditory symptoms of vascular cause. | Lateral pontine and inner ear strokes often cause tinnitus or hearing loss.46,48,58 |

| Diagnose vestibular migraine when headaches accompany dizziness. | Inquire about headache characteristics and associated symptoms. | Sudden, severe, or sustained pain in the head or neck may indicate aneurysm, dissection, or other vascular pathology;51 photophobia may point to migraine.52 |

| Isolated vertigo is not a TIA symptom. | Some TIA definitions do not recognize certain transient vertebro-basilar neurologic symptoms (including isolated vertigo) as TIAs. | Isolated vertigo is the most common vertebro-basilar ‘warning’ symptom before stroke;11,44 it is rarely diagnosed correctly as a vascular symptom at first contact.7,11 |

| Strokes causing dizziness or vertigo will have limb ataxia or other focal signs. | Focus on eye exams: VOR by head impulse test, nystagmus, eye alignment. | Fewer than 20% of stroke patients presenting with AVS have focal neurologic signs.55,56 NIH stroke scales of 0 occur with posterior circulation strokes.66 |

| Young patients have migraine rather than stroke. | Do not over-focus on age and vascular risk factors. Consider vertebral artery dissection in young patients. | Vertebral artery dissection mimics migraine closely;50 young patients 18-44 with stroke are 7-fold more likely to be misdiagnosed than patients over age 75.9 |

| CT is needed to rule out cerebellar hemorrhage in patients with isolated acute dizziness or vertigo. | Intracerebral hemorrhage rarely mimics benign dizziness or vertigo presentations. | Only 2.2% (n=13/595) of intracerebral hemorrhages presented with dizziness or vertigo and only 0.2% (n=1/595) presented with isolated dizziness.67 |

| CT is useful to search for acute posterior fossa stroke. | Recognize the limitations of imaging, especially CT. | Although some retrospective studies68,69 suggest CT may be up to 42% sensitive, prospective studies suggest the sensitivity is no higher than 16%.13,70 |

| A negative MRI-DWI rules out posterior fossa stroke. | Recognize the limitations of imaging, even MRI-DWI. | MRI-DWI in the first 24 hours misses 15-20% of posterior fossa infarctions.12 MRI-DWI sensitivity for brainstem stroke is maximal 72-100 hours after infarction.71 Labyrinthine strokes are not visible. |

Abbreviations: AVS – acute vestibular syndrome; MRI-DWI – magnetic resonance imaging with diffusion-weighted images; NIH – National Institutes of Health; TIA – transient ischemic attack; VOR – vestibulo-ocular reflex

Cerebellar hemorrhages rarely present with isolated dizziness or without clear central neurologic deficits (e.g., dysarthria),67,72 and just 5% of cerebrovascular cases presenting s-AVS are hemorrhages, rather than ischemic strokes.55 Although non-contrast CT identifies acute intracranial hemorrhage with high sensitivity, the low pre-test probability of hemorrhage combined with low sensitivity for acute posterior-fossa ischemia makes CT a poor initial choice for screening patients with isolated dizziness, absent a specific brain hemorrhage risk (e.g., known history of metastatic melanoma).

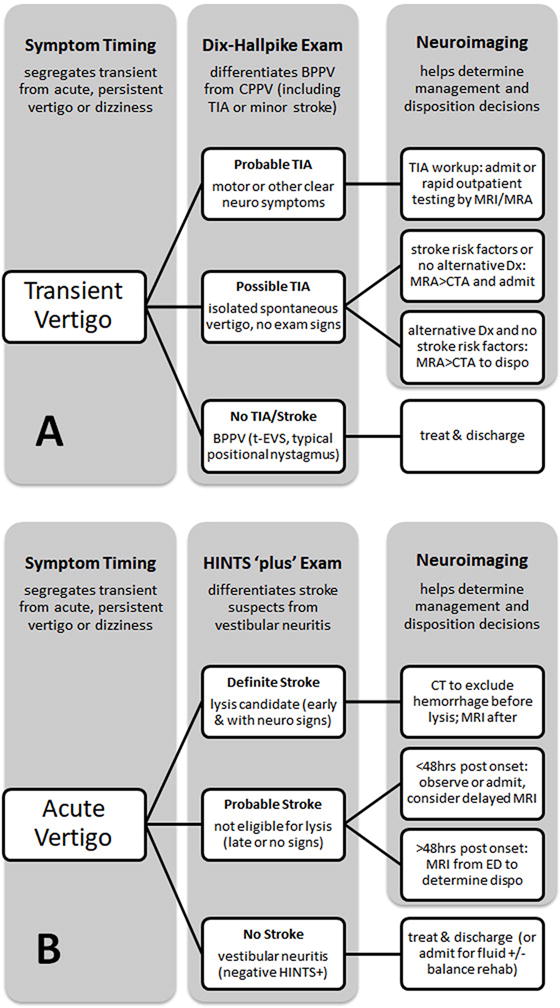

Neuroimaging

The general rule in acute dizziness and vertigo is that if you need neuroimaging, it should be by MRI, rather than CT.12 There are specific exceptions, including the need to definitively exclude hemorrhage before thrombolysis or confirm a suspected vertebral artery dissection by CT angiography. The optimal timing of neuroimaging by MRI is also complex, because the risk of false negatives in the first 48 hours is non-trivial; in some cases, it may be necessary to obtain a repeat MRI if eye findings are suspicious and the initial MRI does not reveal a causal central lesion.14 Although MRI protocols with thinner slices and smaller gaps may improve sensitivity, early false negatives likely relate to the time course of DWI signal intensity change, rather than slice and gap parameters.12,71 In addition to magnetic resonance angiography, special MRI sequences such as “black blood” T1, fat-suppressed axial images through the neck may be necessary to identify intramural hematoma in vertebral artery dissection.12,73 A suggested algorithm for choosing the most appropriate neuroimaging is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Suggested imaging strategy for stroke in patients with new (A) transient or (B) acute, continuous dizziness or vertigo. Abbreviations: BPPV, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo; CPPV, central paroxysmal positional vertigo; TIA, transient ischemic attack; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; Dx, diagnosis; CTA, computed tomography angiography; HINTS, head impulse, nystagmus, test of skew; ED, Emergency Department. Modified from Handb Clin Neurol. 136, Newman-Toker DE et al. Vertigo and hearing loss, 905-921, 2016 with permission from Elsevier.12

Summary

Diagnosing cerebrovascular causes of acute dizziness and vertigo is both important and difficult. It is not routinely done well in current clinical ED practice, where misdiagnosis is frequent, patient harms are significant, and costs are high.3 This stems from a focus on dizziness type and overreliance on negative neurologic examinations and CT results. Current best evidence suggests an alternative approach emphasizing dizziness timing and triggers, focused ocular motor examinations, and MRI, as needed. This “TiTrATE” approach is commonly used by sub-specialists in vestibular neurology, but is not yet common practice among emergency physicians or neurologists. Since most patients in some settings will never be seen by a neurologist,74 and routine MRI for these patients is untenable, alternative strategies to disseminate this approach may be required. Preliminary studies have found accurate diagnosis using a portable video-oculography device that measures eye movements quantitatively.75,76 This approach has the potential to be broadly scalable in the form of an “eye ECG” that helps diagnose stroke in acute dizziness via device-based decision support with telemedicine backup.23 An ongoing NIH [NIDCD] phase II clinical trial of this approach (AVERT, ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02483429) seeks to develop this general approach going forward.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

None.

Sources of Funding: Dr. Newman-Toker’s effort was supported by grant U01 DC013778 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

Dr. Kattah received loaned research equipment from GN Otometrics, Taastrup, Denmark, in 2012, which is no longer in use.

Dr. Kerber has received research support from NIH/NIDCD R01DC012760, AHRQ R18HS022258, and NIHU01DC013778-01A1, and reimbursement for travel to a conference from GN Otometrics.

Dr. Newman-Toker serves as a paid consultant, reviewing medicolegal cases for both plaintiff and defense firms related to misdiagnosis of neurological conditions, including dizziness and stroke. He has conducted government and foundation funded research related to diagnostic error. Funding was received from the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. He has been loaned research equipment related to diagnosis of dizziness and stroke by two commercial companies (GN Otometrics and Interacoustics).

Footnotes

Conflict(s) of Interest/Disclosure(s):

Drs. Saber Tehrani, Gold, Zee, and Urrutia report no disclosures relevant to this manuscript.

Bibliography

- 1.Saber Tehrani AS, Coughlan D, Hsieh YH, Mantokoudis G, Korley FK, Kerber KA, et al. Rising annual costs of dizziness presentations to u.S. Emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:689–696. doi: 10.1111/acem.12168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman-Toker DE, Edlow JA. Titrate: A novel, evidence-based approach to diagnosing acute dizziness and vertigo. Neurol Clin. 2015;33:577–599, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman-Toker DE. Missed stroke in acute vertigo and dizziness: It is time for action, not debate. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:27–31. doi: 10.1002/ana.24532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman-Toker DE, McDonald KM, Meltzer DO. How much diagnostic safety can we afford, and how should we decide? A health economics perspective. BMJ quality & safety. 2013;22(Suppl 2):ii11–ii20. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eagles D, Stiell IG, Clement CM, Brehaut J, Kelly AM, Mason S, et al. International survey of emergency physicians' priorities for clinical decision rules. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:177–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Improving diagnosis in health care. 2015 http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2015/Improving-Diagnosis-in-Healthcare.aspx. Accessed August 20, 2017.

- 7.Tarnutzer AA, Lee SH, Robinson KA, Wang Z, Edlow JA, Newman-Toker DE. Ed misdiagnosis of cerebrovascular events in the era of modern neuroimaging: A meta-analysis. Neurology. 2017;88:1468–1477. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuruvilla A, Bhattacharya P, Rajamani K, Chaturvedi S. Factors associated with misdiagnosis of acute stroke in young adults. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;20:523–527. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newman-Toker DE, Moy E, Valente E, Coffey R, Hines AL. Missed diagnosis of stroke in the emergency department: A cross-sectional analysis of a large population-based sample. Diagnosis (Berl) 2014;1:155–166. doi: 10.1515/dx-2013-0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atzema CL, Grewal K, Lu H, Kapral MK, Kulkarni G, Austin PC. Outcomes among patients discharged from the emergency department with a diagnosis of peripheral vertigo. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:32–41. doi: 10.1002/ana.24521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul NL, Simoni M, Rothwell PM, Oxford Vascular S. Transient isolated brainstem symptoms preceding posterior circulation stroke: A population-based study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:65–71. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70299-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newman-Toker DE, Della Santina CC, Blitz AM. Vertigo and hearing loss. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;136:905–921. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53486-6.00046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chalela JA, Kidwell CS, Nentwich LM, Luby M, Butman JA, Demchuk AM, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in emergency assessment of patients with suspected acute stroke: A prospective comparison. Lancet. 2007;369:293–298. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60151-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saber Tehrani AS, Kattah JC, Mantokoudis G, Pula JH, Nair D, Blitz A, et al. Small strokes causing severe vertigo: Frequency of false-negative mris and nonlacunar mechanisms. Neurology. 2014;83:169–173. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gulli G, Khan S, Markus HS. Vertebrobasilar stenosis predicts high early recurrent stroke risk in posterior circulation stroke and tia. Stroke. 2009;40:2732–2737. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.553859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, Marquardt L, Geraghty O, Redgrave JN, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (express study): A prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet. 2007;370:1432–1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavallee PC, Meseguer E, Abboud H, Cabrejo L, Olivot JM, Simon O, et al. A transient ischaemic attack clinic with round-the-clock access (sos-tia): Feasibility and effects. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:953–960. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70248-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wijdicks EF, Sheth KN, Carter BS, Greer DM, Kasner SE, Kimberly WT, et al. Recommendations for the management of cerebral and cerebellar infarction with swelling: A statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2014;45:1222–1238. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000441965.15164.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savitz SI, Caplan LR, Edlow JA. Pitfalls in the diagnosis of cerebellar infarction. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:63–68. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tohgi H, Takahashi S, Chiba K, Hirata Y. Cerebellar infarction. Clinical and neuroimaging analysis in 293 patients. The tohoku cerebellar infarction study group. Stroke. 1993;24:1697–1701. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.11.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerber KA, Newman-Toker DE. Misdiagnosing dizzy patients: Common pitfalls in clinical practice. Neurol Clin. 2015;33:565–575, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerber KA. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: Opportunities squandered. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1343:106–112. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman-Toker DE, Curthoys IS, Halmagyi GM. Diagnosing stroke in acute vertigo: The hints family of eye movement tests and the future of the “eye ecg”. Seminars in neurology. 2015;35:506–521. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1564298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pope JV, Edlow JA. Avoiding misdiagnosis in patients with neurological emergencies. Emerg Med Int. 2012;2012:949275. doi: 10.1155/2012/949275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerber KA, Forman J, Damschroder L, Telian SA, Fagerlin A, Johnson P, et al. Barriers and facilitators to ed physician use of the test and treatment for bppv. Neurol Clin Pract. 2017;7:214–224. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanton VA, Hsieh YH, Camargo CA, Jr, Edlow JA, Lovett P, Goldstein JN, et al. Overreliance on symptom quality in diagnosing dizziness: Results of a multicenter survey of emergency physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:1319–1328. doi: 10.4065/82.11.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerber KA, Callaghan BC, Telian SA, Meurer WJ, Skolarus LE, Carender W, et al. Dizziness symptom type prevalence and overlap: A US nationally representative survey. [published online ahead of print April 7, 2017] Am J Med. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.05.048. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002934317307143?via%3Dihub. Accessed November 30, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Grewal K, Austin PC, Kapral MK, Lu H, Atzema CL. Missed strokes using computed tomography imaging in patients with vertigo: Population-based cohort study. Stroke. 2015;46:108–113. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bisdorff A, Von Brevern M, Lempert T, Newman-Toker DE. Classification of vestibular symptoms: Towards an international classification of vestibular disorders. J Vestib Res. 2009;19:1–13. doi: 10.3233/VES-2009-0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi KD, Shin HY, Kim JS, Kim SH, Kwon OK, Koo JW, et al. Rotational vertebral artery syndrome: Oculographic analysis of nystagmus. Neurology. 2005;65:1287–1290. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000180405.00560.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim HA, Yi HA, Lee H. Apogeotropic central positional nystagmus as a sole sign of nodular infarction. Neurol Sci. 2012;33:1189–1191. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0884-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johkura K. Central paroxysmal positional vertigo: Isolated dizziness caused by small cerebellar hemorrhage. Stroke. 2007;38:e26–27. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.480319. author reply e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ertl L, Morhard D, Deckert-Schmitz M, Linn J, Schulte-Altedorneburg G. Focal subarachnoid haemorrhage mimicking transient ischaemic attack–do we really need mri in the acute stage? BMC Neurol. 2014;14:80. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-14-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newman-Toker D. Vestibular syndrome definitions for the international classification of vestibular disorders. Bárány Committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders meeting presentation; March 2017; Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kerber KA, Burke JF, Skolarus LE, Meurer WJ, Callaghan BC, Brown DL, et al. Use of bppv processes in emergency department dizziness presentations: A population-based study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148:425–430. doi: 10.1177/0194599812471633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Royl G, Ploner CJ, Leithner C. Dizziness in the emergency room: Diagnoses and misdiagnoses. Eur Neurol. 2011;66:256–263. doi: 10.1159/000331046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.von Brevern M, Bertholon P, Brandt T, Fife T, Imai T, Nuti D, et al. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: Diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res. 2015;25:105–117. doi: 10.3233/VES-150553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhattacharyya N, Baugh RF, Orvidas L, Barrs D, Bronston LJ, Cass S, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139:S47–S81. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macdonald NK, Kaski D, Saman Y, Al-Shaikh Sulaiman A, Anwer A, Bamiou DE. Central positional nystagmus: A systematic literature review. Front Neurol. 2017;8:141. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuether TA, Nesbit GM, Clark WM, Barnwell SL. Rotational vertebral artery occlusion: A mechanism of vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:427–432. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199708000-00019. discussion 432–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi JH, Park MG, Choi SY, Park KP, Baik SK, Kim JS, et al. Acute transient vestibular syndrome: Prevalence of stroke and efficacy of bedside evaluation. Stroke. 2017;48:556–562. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newman-Toker DE, Camargo CA., Jr ‘Cardiogenic vertigo’–true vertigo as the presenting manifestation of primary cardiac disease. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2006;2:167–172. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0125. quiz 173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Newman-Toker DE, Dy FJ, Stanton VA, Zee DS, Calkins H, Robinson KA. How often is dizziness from primary cardiovascular disease true vertigo? A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:2087–2094. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0801-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoshino T, Nagao T, Mizuno S, Shimizu S, Uchiyama S. Transient neurological attack before vertebrobasilar stroke. J Neurol Sci. 2013;325:39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, Alberts MJ, Chaturvedi S, Feldmann E, et al. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association stroke council. Stroke. 2009;40:2276–2293. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hausler R, Levine RA. Auditory dysfunction in stroke. Acta Otolaryngol. 2000;120:689–703. doi: 10.1080/000164800750000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park JH, Kim H, Han HJ. Recurrent audiovestibular disturbance initially mimicking meniere's disease in a patient with anterior inferior cerebellar infarction. Neurol Sci. 2008;29:359–362. doi: 10.1007/s10072-008-0996-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang TP, Wang Z, Winnick AA, Chuang HY, Urrutia VC, Carey JP, et al. Sudden hearing loss with vertigo portends greater stroke risk than sudden hearing loss or vertigo alone. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.09.033. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1052305717305177?via%3Dihub. Accessed November 30, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Schwartz NE, Venkat C, Albers GW. Transient isolated vertigo secondary to an acute stroke of the cerebellar nodulus. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:897–898. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.6.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gottesman RF, Sharma P, Robinson KA, Arnan M, Tsui M, Ladha K, et al. Clinical characteristics of symptomatic vertebral artery dissection: A systematic review. The neurologist. 2012;18:245–254. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e31826754e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Newman-Toker DE. Symptoms and signs of neuro-otologic disorders. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2012;18:1016–1040. doi: 10.1212/01.CON.0000421618.33654.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lempert T, Neuhauser H, Daroff RB. Vertigo as a symptom of migraine. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1164:242–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trevino R. A 19-year-old woman with unexplained weakness and dizziness. J Emerg Nurs. 1997;23:499–500. doi: 10.1016/s0099-1767(97)90154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kerber KA, Meurer WJ, Brown DL, Burke JF, Hofer TP, Tsodikov A, et al. Stroke risk stratification in acute dizziness presentations: A prospective imaging-based study. Neurology. 2015;85:1869–1878. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tarnutzer AA, Berkowitz AL, Robinson KA, Hsieh YH, Newman-Toker DE. Does my dizzy patient have a stroke? A systematic review of bedside diagnosis in acute vestibular syndrome. CMAJ. 2011;183:E571–592. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, Hsieh YH, Newman-Toker DE. Hints to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: Three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early mri diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke. 2009;40:3504–3510. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.551234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Newman-Toker DE, Kattah JC, Alvernia JE, Wang DZ. Normal head impulse test differentiates acute cerebellar strokes from vestibular neuritis. Neurology. 2008;70:2378–2385. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000314685.01433.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Newman-Toker DE, Kerber KA, Hsieh YH, Pula JH, Omron R, Saber Tehrani AS, et al. Hints outperforms abcd2 to screen for stroke in acute continuous vertigo and dizziness. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:986–996. doi: 10.1111/acem.12223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carmona S, Martinez C, Zalazar G, Moro M, Batuecas-Caletrio A, Luis L, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of truncal ataxia and hints as cardinal signs for acute vestibular syndrome. Front Neurol. 2016;7:125. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kene MV, Ballard DW, Vinson DR, Rauchwerger AS, Iskin HR, Kim AS. Emergency physician attitudes, preferences, and risk tolerance for stroke as a potential cause of dizziness symptoms. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16:768–776. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.7.26158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jorns-Haderli M, Straumann D, Palla A. Accuracy of the bedside head impulse test in detecting vestibular hypofunction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:1113–1118. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.109512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tarnutzer AA, Berkowitz AL, Robinson KA, Hsieh YH, Newman-Toker DE. Does my dizzy patient have a stroke? A systematic review of bedside diagnosis in acute vestibular syndrome. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2011;183:E571–592. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Newman-Toker DE, Kerber KA, Hsieh YH, Pula JH, Omron R, Saber Tehrani AS, et al. Hints outperforms abcd2 to screen for stroke in acute continuous vertigo and dizziness. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2013;20:986–996. doi: 10.1111/acem.12223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Newman-Toker DE, Cannon LM, Stofferahn ME, Rothman RE, Hsieh YH, Zee DS. Imprecision in patient reports of dizziness symptom quality: A cross-sectional study conducted in an acute care setting. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:1329–1340. doi: 10.4065/82.11.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee H, Sohn SI, Cho YW, Lee SR, Ahn BH, Park BR, et al. Cerebellar infarction presenting isolated vertigo: Frequency and vascular topographical patterns. Neurology. 2006;67:1178–1183. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000238500.02302.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martin-Schild S, Albright KC, Tanksley J, Pandav V, Jones EB, Grotta JC, et al. Zero on the nihss does not equal the absence of stroke. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:42–45. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.06.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kerber KA, Burke JF, Brown DL, Meurer WJ, Smith MA, Lisabeth LD, et al. Does intracerebral haemorrhage mimic benign dizziness presentations? A population based study. Emerg Med J. 2012;29:43–46. doi: 10.1136/emj.2010.104844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hwang DY, Silva GS, Furie KL, Greer DM. Comparative sensitivity of computed tomography vs. Magnetic resonance imaging for detecting acute posterior fossa infarct. J Emerg Med. 2012;42:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.05.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lawhn-Heath C, Buckle C, Christoforidis G, Straus C. Utility of head ct in the evaluation of vertigo/dizziness in the emergency department. Emerg Radiol. 2013;20:45–49. doi: 10.1007/s10140-012-1071-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ozono Y, Kitahara T, Fukushima M, Michiba T, Imai R, Tomiyama Y, et al. Differential diagnosis of vertigo and dizziness in the emergency department. Acta Otolaryngol. 2014;134:140–145. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2013.832377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Axer H, Grassel D, Bramer D, Fitzek S, Kaiser WA, Witte OW, et al. Time course of diffusion imaging in acute brainstem infarcts. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26:905–912. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee S-H, Stanton V, Rothman R, Crain B, Wityk R, Wang Z, et al. Misdiagnosis of cerebellar hemorrhage – features of ‘pseudo-gastroenteritis’ clinical presentations to the ed and primary care. Diagnosis. 2017;4:27–33. doi: 10.1515/dx-2016-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gottesman RF, Sharma P, Robinson KA, Arnan M, Tsui M, Saber-Tehrani A, et al. Imaging characteristics of symptomatic vertebral artery dissection: A systematic review. The neurologist. 2012;18:255–260. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e3182675511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brown DL, Lisabeth LD, Garcia NM, Smith MA, Morgenstern LB. Emergency department evaluation of ischemic stroke and tia: The basic project. Neurology. 2004;63:2250–2254. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000147292.64051.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Newman-Toker DE, Saber Tehrani AS, Mantokoudis G, Pula JH, Guede CI, Kerber KA, et al. Quantitative video-oculography to help diagnose stroke in acute vertigo and dizziness: Toward an ecg for the eyes. Stroke. 2013;44:1158–1161. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mantokoudis G, Tehrani AS, Wozniak A, Eibenberger K, Kattah JC, Guede CI, et al. Vor gain by head impulse video-oculography differentiates acute vestibular neuritis from stroke. Otology & neurotology. 2015;36:457–465. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.