Abstract

Background and Purpose

Prehospital scales have been developed to identify patients with acute cerebral ischemia (ACI) due to large vessel occlusion (LVO) for direct routing to Comprehensive Stroke Centers (CSCs), but few have been validated in the prehospital setting, and their impact on routing of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) patients has not been delineated. The purpose of this study was to validate the Los Angeles Motor Scale (LAMS) for LVO and CSC-appropriate (LVO ACI and ICH patients) recognition and compare the LAMS to other scales.

Methods

The performance of the LAMS, administered prehospital by paramedics to consecutive ambulance trial patients, was assessed in identifying: 1) LVOs among all ACI patients, and 2) CSC-Appropriate patients among all suspected strokes. Additionally, the LAMS administered post-arrival was compared concurrently with 6 other scales proposed for paramedic use and the full National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS).

Results

Among 94 patients, age was 70 (±13) and 49% female. Final diagnoses were acute cerebral ischemia in 76% (due to LVO in 48% and non-LVO in 28%), ICH in 19%, and neurovascular mimic in 5%. The LAMS administered by paramedics in the field performed moderately well in identifying LVO among ACI patients (c statistic 0.79, accuracy 0.72) and CSC-Appropriate among all suspected stroke transports (c statistic 0.80, accuracy 0.72). When concurrently performed in the Emergency Department post-arrival, the LAMS showed comparable or better accuracy versus the 7 comparator scales, for LVO among ACI (accuracies LAMS 0.70, other scales 0.62–0.68) and CSC-Appropriate (accuracies LAMS 0.73, other scales 0.56–0.73).

Conclusions

The LAMS performed in the field by paramedics identifies large vessel occlusion and CSC-Appropriate patients with good accuracy. The LAMS performs comparably or better than more extended prehospital scales and the full NIHSS.

Keywords: field validation, Los Angeles Motor Scale, paramedic assessment, prehospital stroke scales, stroke, large vessel occlusion

Introduction

National guidance in the United States for regional systems of acute stroke care has recommended a two tier system comprised of disseminated Primary Stroke Centers (PSCs) and Acute Stroke Ready Hospitals (ASRHs) able to provide intravenous fibrinolysis and organized supportive care and Comprehensive Stroke Centers (CSCs) able to provide endovascular interventions for acute cerebral ischemia and advanced neurosurgical and neurointensive care for patients with intracranial hemorrhage.1, 2 The desirability of routing select ambulance patients directly to Comprehensive Stroke Centers for faster definitive care has been intensified by the demonstration of dramatic, but time-dependent, benefit of endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke due to large vessel occlusion (LVO).3 Accordingly, there is an urgent need to develop and validate LVO-recognition scales for paramedic use in the field, to identify patients who would benefit from direct routing to a nearby CSC, diverting past an even nearer PSC.2, 4, 5

In response to this imperative, several scale thresholds and scale instruments have been developed for paramedic use to identify LVO in the field. The first approach developed was a scale threshold for the Los Angeles Motor Scale (LAMS).6 A 3-item, 0- to 10-point motor stroke-deficit scale, the LAMS had initially been developed for the general purpose of characterizing stroke deficit severity in the field.7 For this application, it performs well, showing excellent concurrent, predictive, and divergent validity when administered by paramedics in the field in a recent large validation study.8 After development, similarly to the NIHSS, the LAMS was analyzed to identify a score threshold associated with an LVO. In a derivation study in consecutive patients examined in the Emergency Department (ED) by physicians, a LAMS threshold ≥ 4 predicted LVO with good accuracy.6 However, this threshold requires validation in patients actually examined prehospital by paramedics. It is also important to analyze how LVO recognition scales categorize, for direct CSC vs PSC routing, prehospital stroke patients whose focal deficits are due to acute intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) rather than ischemic stroke.

Compared with other, generally later-developed, LVO identification instruments,9–14 the LAMS is briefer (3 items), easier to implement (all straightforward motor items), and more efficient [LAMS is obtained automatically when the Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen (LAPSS) is performed for stroke recognition]. If the LAMS performs comparably or better than other scales developed for LVO recognition, it could more easily be integrated into paramedic practice. We undertook a field validation study of the LAMS for LVO recognition and for CSC-appropriate (LVO AIS and ICH patients) recognition, and analyzed the comparative performance of the LAMS with 6 other, later-proposed prehospital the full NIHSS.

Materials and Methods

We analyzed data prospectively gathered in the Field Administration of Stroke Therapy – Magnesium (FAST-MAG) phase 3 randomized trial, which studied prehospital initiation of magnesium versus placebo for likely stroke patients presenting within 2 hours from last known well time.15 Any query regarding the data supporting the findings of this study can be requested from the FAST-MAG Trial Publication Committee through the corresponding author. The detailed methods of the FAST-MAG trial have been previously published.16, 17 For this study, data were analyzed from consecutive patients transported to UCLA Medical Center, the only FAST-MAG receiving hospital site with a standing clinical policy throughout the study period (2004–2012) of obtaining vessel imaging immediately upon patient arrival, using magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or computed tomography angiography (CTA).

The study was approved by the prehospital and hospital Institutional Review Boards. Patients were enrolled using explicit written informed consent (preponderance of enrollments) or exception from explicit informed consent in emergency research circumstances (when patient not competent and no legally authorized representative on scene). Patients with likely stroke, indicated by a positive modified LAPSS, and within 2 hours of last known well, were enrolled in the trial. Paramedics performed the LAMS and the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) at time of enrollment in the field in all patients. After hospital arrival, study research coordinators performed the NIHSS and concurrently performed repeat LAMS and GCS assessments.

At the individual patient level, study entry criteria were: 1) transport by UCLA Medical Center by Emergency Medical Services for likely stroke; 2) enrollment in FAST-MAG, and 3) MRA or CTA obtained within 6 hrs of Emergency Department arrival AND prior to intravenous tPA or endovascular thrombectomy. Among final diagnosis acute cerebral ischemia patients, the first vessel imaging study, MRA or CTA, was independently analyzed by two vascular neurologists blinded to other data, assessing if a vessel occlusion was present and which arterial segment was involved. Discordant ratings were settled by joint scan review. Occluded arterial segments were placed into categories of extra-large vessel occlusions (XLVO), large vessel occlusions (LVO), and medium vessel occlusions (MVO). The lead occlusion site analysis was of LVOs, defined as arteries potentially accessible by current endovascular thrombectomy technology. Accordingly, LVO occlusions included occlusions of the intracranial internal carotid artery, the middle cerebral artery (MCA) M1 or M2 segments, the vertebral artery, the basilar artery, the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) P1 segment and the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) A1 segment. XLVO occlusions were the subset of LVO occlusions that are largest, most proximal, and most easily accessed: the ICA, M1 MCA, VA and BA. Patients were considered to have MVOs if occlusions were in the arterial segments inaccessible to endovascular approach: MCA M3 or M4, PCA P2 or higher, and ACA A2 or higher. Patients were placed in the category of CSC-Appropriate if they had either LVO-AIS or ICH.

In the field validation portion of the current study, the performance of the LAMS administered by paramedics in the prehospital setting (PH LAMS) was assessed in identifying: 1) LVOs among all acute cerebral ischemia patients, and 2) CSC-Appropriate patients among all suspected stroke patients. As a negative control, the predictive value of the prehospital GCS (PH GCS) administered by paramedics was also assessed.

In the scale comparison portion of the current study, the predictive value of 8 scales performed by study nurse coordinators in the ED was assessed in identifying: 1) LVOs among all acute cerebral ischemia patients, and 2)CSC-Appropriate patients among all suspected stroke patients. The more extended exam interval in the ED permitted the full NIHSS to be performed, in addition to repeat LAMS and GCS assessments, and individual NIHSS item scores were used to populate multiple LVO assessment scales. The 8 scales for LVO recognition assessed in the ED included 6 developed for prehospital and 2 for ED use. The prehospital scales were: 1) LAMS;6 2) Cincinnati Stroke Triage Assessment Tool (C-STAT; formerly CPSSS);10 3) Field Assessment Stroke Triage for Emergency Destination (FAST-ED);13 4) Pre-hospital Acute Stroke Severity (PASS) scale;11 5) Rapid Arterial Occlusion Evaluation (RACE) scale;12 and 6) Vision-Aphasia-Neglect (VAN) scale.14 The ED scales were: 1) 3-item Stroke scale (3i-SS),9 and 2) full NIHSS. For the prehospital scales and the 3i-SS, the cutpoint evaluated for predicting LVO presence was that recommended by each scale publication, and the same cutpoint was used to identify all CSC-Appropriate patients. For the NIHSS, two recommended cutpoints were analyzed, ≥ 10 and ≥ 7.18, 19 For the GCS, the cutpoint was selected using the Youden Index.20

For all scales, predictive performance over full scale range was evaluated by calculating the c statistic, and predictive performance for suggested scale cut points was evaluated by calculation of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, overall accuracy, and positive and negative likelihood ratios. For the c statistic, scale performance was considered excellent for values between 0.9–1, good between 0.8–0.9, fair between 0.7–0.8, poor between 0.6–0.7 and failed between 0.5–0.6.21

Results

Among the 94 study patients, mean age was 70±13, 49% were female, median prehospital LAMS 4.0 (IQR 3.0–5.0), and median ED NIHSS 9 (IQR 2–18). Final stroke subtype diagnosis was acute cerebral ischemia in 76%, intracranial hemorrhage in 19%, and neurovascular mimic in 5%. The mode of first vessel imaging was MRA in 82% and CTA in 18%. The time interval from last known well (LKW) to paramedic LAMS examination in the field was median 23.5 mins (IQR 14.0–39.3). Additional time intervals were: LKW to ED arrival 62 mins (IQR 48.8–87.3); LKW to first vessel imaging 100.5 mins (IQR 83.3–128.3); and LKW to study nurse ED examination 160 mins (IQR 122.3–195.0). Transports were by 29 ambulances from 4 EMS provider agencies.

Among patients with acute cerebral ischemia, vessel occlusion locations are shown in Table 1. LVOs were present in 45/71 (63%), including XLVOs in 36/71 (51%); medium vessel occlusions were present in 5/71 (7%), and no occlusion was observed in 21/71 (30%). Considering LVO ACI patients (n=45) and ICH patients (n=18), CSC-Appropriate patients accounted for 63/94 (67%) of transports.

Table 1.

Final diagnoses among enrolled patients

| N | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Acute Cerebral Ischemia | 71/94 | 76% |

| No vessel occlusion | 21/94 | 22% |

| LVO | 45/94 | 48% |

| ICA | 13/94 | 14% |

| M1 | 21/94 | 22% |

| M2 | 9/94 | 10% |

| VA | 1/94 | 1% |

| BA | 1/94 | 1% |

| P1 PCA | 0/94 | 0% |

| A1 ACA | 0/94 | 0% |

| MVO | 5/94 | 5% |

| M3-4 | 2/94 | 2% |

| P2 PCA | 3/94 | 3% |

| A2 ACA | 0/94 | 0% |

| Intracranial Hemorrhage | 18/94 | 19% |

| CVD Mimic | 5/94 | 5% |

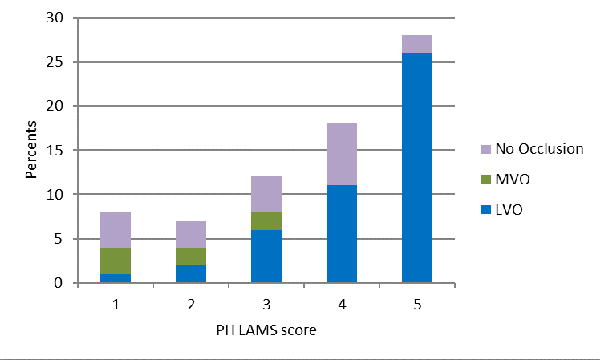

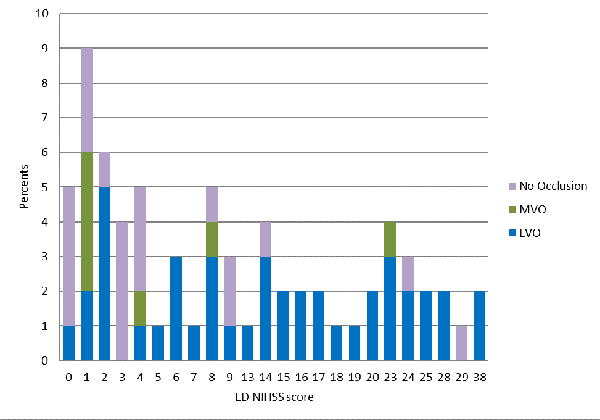

The demographic and clinical features of patients are shown in Table 2. Severity of focal deficits was the only feature consistently distinguishing LVO and CSC-Appropriate patients from all other suspected stroke patients. Both the prehospital LAMS and ED NIHSS were higher in the target patients (Table 2 and Figure 1A,B, Supplementary Figure 1A,B).

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | All Patients | ACI due to LVO | ACI due to Non-LVO | ICH | CVD Mimics | P value LVO vs Other | P value CSC-Appropriate vs Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 94 | 45 | 26 | 18 | 5 | – | – |

| Age (Mean, SD) | 69.6 (12.9) | 70.7 (11.5) | 69.5 (14.0) | 65.1 (13.1) | 78.0 (16.8) | 0.61 | 0.60 |

| Sex Female (N, Percent) | 46 (48.9) | 23 (51.1) | 12 (46.2) | 8 (44.4) | 3 (60.0) | 0.69 | 0.94 |

| Race (N, Percent) | |||||||

| Asian | 4 (4.3) | 2 (4.4) | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.49 | 0.98 |

| Black | 21 (22.3) | 12 (26.7) | 5 (19.2) | 4 (27.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.49 | 0.98 |

| White | 68 (72.3) | 31 (68.9) | 18 (69.2) | 14 (77.8) | 5 (100) | 0.49 | 0.98 |

| Other | 1(1.1) | 0(0.0) | 1(3.8) | 0(0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.49 | 0.98 |

| Ethnicity – Hispanic (N, %t) | 12 (12.8) | 3 (6.7) | 3 (11.5) | 5 (27.8) | 1 (20.0) | 0.47 | 0.98 |

| Prehospital LAMS | |||||||

| Mean, SD | 3.7 (1.3) | 4.1 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.3) | 4.1 (1.1) | 2.4 (0.9) | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Median, IQR | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 5 (3.5–5) | 3 (1.5–4) | 4.5 (3.0–5.0) | 3.0 (1.5–3.0) | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Prehospital GCS | |||||||

| Mean, SD | 14.2 (1.6) | 13.8 (1.8) | 14.4 (1.7) | 14.7 (1.0) | 14.4 (0.9) | 0.16 | 0.32 |

| Median, IQR | 15.0 (14.0–15.0) | 15 (13–15) | 15 (15–15) | 15.0 (15.0–15.0) | 15.0 (13.5–15.0) | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| ED NIHSS | |||||||

| Mean, SD | 11.1 (9.4) | 13.5 (10.1) | 6.1 (7.9) | 13.7 (5.5) | 6.8 (11.3) | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| Median, IQR | 9.0 (2–18) | 14 (4.5–21.5) | 3 (1–8) | 12.5 (9.0–18.3) | 2.0 (1.5–14.5) | 0.001 | 0.03 |

| Prestroke Modified Rankin Scale (Median, IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.48 | 0.86 |

| Hypertension (N, Percent) | 65 (69.1) | 33 (73.3) | 19 (73.1) | 9 (50.0) | 4 (80.0) | 0.98 | 0.45 |

| Diabetes (N, Percent) | 18 (19.1) | 9 (20.0) | 5 (19.2) | 2 (11.1) | 2 (40.0) | 0.94 | 0.55 |

| Hyperlipidemia (N, Percent) | 44 (46.8) | 26 (57.8) | 14 (53.8) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (80.0) | 0.75 | 0.13 |

| Atrial fibrillation (N, Percent) | 26 (27.7) | 15 (33.3) | 9 (34.6) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (20.0) | 0.91 | 0.48 |

| Smoking (N, Percent) | 17 (18.1) | 9 (20.0) | 7 (26.9) | 3 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 0.63 | 0.73 |

| Prior Ischemic Stroke (N, Percent) | 10 (10.6) | 5 (11.1) | 4 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0.60 | 0.27 |

| Prior TIA (N, Percent) | 8 (8.5) | 2 (4.4) | 2 (7.7) | 2 (11.1) | 2 (40.0) | 0.57 | 0.28 |

| Any alcohol use (N, Percent) | 39 (41.5) | 22 (48.9) | 8 (30.8) | 8 (44.4) | 1 (20.0) | 0.14 | 0.86 |

Figure 1.

Deficit severity scores of acute cerebral ischemia patients with large vessel occlusions (LVO). medium vessel occlusions (MVO), and no visualized occlusion, on: A) the Los Angeles Motor Scale performed in the field by paramedics, and B) the full NIH Stroke Scale performed in the ED after hospital arrival.

The LAMS performed by paramedics in the field showed fair performance as a continuous scale in predicting the presence of LVO among cerebral ischemia patients (c statistic = 0.79), and good performance in identifying CSC-Appropriate patients among all suspected stroke transports, (c statistic = 0.80). The prehospital LAMS score cutoff at ≥ 4 showed good binary performance (Table 3), both in identifying LVOs among cerebral ischemia patients (sensitivity 0.76, specificity 0.65, and accuracy 0.72) and in identifying CSC-Appropriate patients among all suspected stroke transports (sensitivity 0.73, specificity 0.71, and accuracy 0.72). Prehospital LAMS performance was similar for identifying XLVOs (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 3.

Performance of Prehospital LAMS ≥ 4 in Identifying LVO and CSC-Appropriate Patients

| LVO Among All Cerebral Ischemia | CSC Among All Suspected Stroke Transports | |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 0.76 | 0.73 |

| Specificity | 0.65 | 0.71 |

| Positive Predictive Value | 0.79 | 0.84 |

| Negative Predictive Value | 0.61 | 0.56 |

| Accuracy | 0.72 | 0.72 |

| Positive Likelihood Ratio | 2.18 | 2.51 |

| Negative Likelihood Ratio | 0.37 | 0.38 |

In contrast, the GCS performed by paramedics in the field showed poor performance as a continuous scale in identifying LVOs among those with cerebral ischemia (c statistic = 0.61) and failed performance in identifying CSC-Appropriate patients among all suspected stroke transports (c statistic = 0.56).The best prehospital GCS threshold of ≤ 14 also performed poorly in identifying LVOs among cerebral ischemia patients (sensitivity 0.4, specificity 0.84, accuracy 0.56) and CSC-Appropriate patients among all suspected stroke transports (sensitivity 0.32, specificity 0.81, accuracy 0.47).

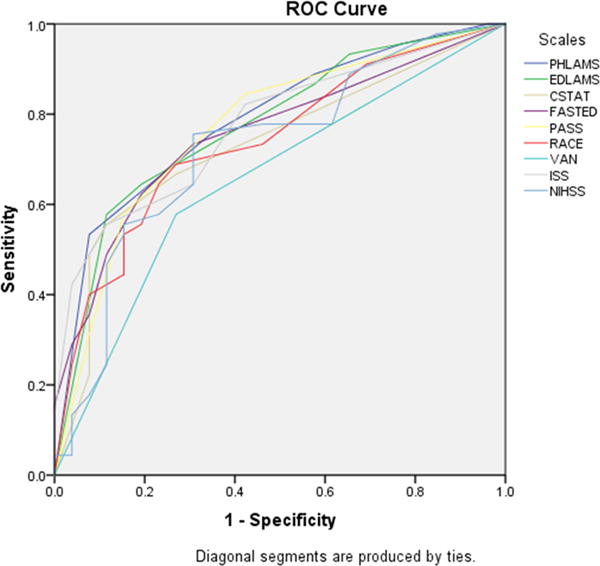

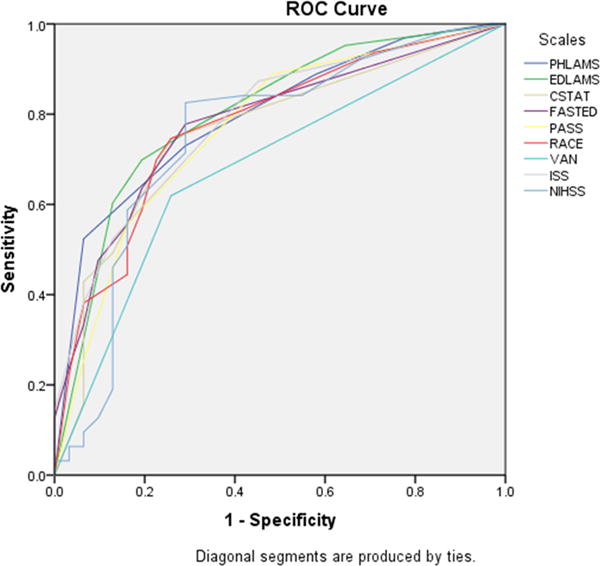

The comparative performance of the 8 scales administered by study nurse coordinators in the ED is shown in Figure 2 and Table 4. For identifying LVOsamong those with cerebral ischemia, all thresholded scales showed fair to moderate performance (accuracies ranging from 0.62 to 0.70). The 4 highest accuracy point estimates were for the LAMS (0.70), the C-STAT (0.68), the PASS (0.68), and the full NIHSS cutoff at ≥ 7 (0.68) and the two lowest point estimates were for the 3i-SS (0.62) and the VAN (0.63). For identifying CSC-Appropriate patients among all suspected stroke transports, the scales showed performance ranging from poor to moderate (accuracies ranging from 0.56 to 0.73). The 4 highest accuracy point estimates were for the LAMS (0.73) and the full NIHSS cutoff at ≥ 7 (0.73), RACE (0.66) and VAN (0.66) and the two lowest point estimates were for the 3i-SS (0.56) and the C-STAT (0.62). Similar results were seen for identifying XLVOs (Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 2.

Comparative performance of 8 scales administered concurrently after ED arrival, in identifying: A) large vessel occlusions among all patients with acute cerebral ischemia, and B) CSC-Appropriate patients among all suspected stroke transports.

Table 4.

Performance of Scales in the ED in Identifying LVO and CSC-Appropriate Patients

| LVO Among All Cerebral Ischemia Patients | CSC-Appropriate Among All Suspected Stroke Transports | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy* | PPV | NPV | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy* | PPV | NPV | |

| ED LAMS | 0.64 | 0.81 | 0.70 | 0.85 | 0.57 | 0.70 | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.88 | 0.57 |

| ED C-STAT | 0.56 | 0.88 | 0.68 | 0.89 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.87 | 0.62 | 0.89 | 0.46 |

| ED FAST-ED | 0.56 | 0.85 | 0.66 | 0.86 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.84 | 0.65 | 0.88 | 0.48 |

| ED PASS | 0.58 | 0.85 | 0.68 | 0.87 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.84 | 0.65 | 0.88 | 0.48 |

| ED RACE | 0.56 | 0.81 | 0.65 | 0.83 | 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.86 | 0.49 |

| ED VAN | 0.58 | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.79 | 0.50 | 0.62 | 0.74 | 0.66 | 0.83 | 0.49 |

| ED 3i-SS | 0.42 | 0.96 | 0.62 | 0.95 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.94 | 0.56 | 0.92 | 0.43 |

| ED NIHSS ≥ 7 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.79 | 0.55 | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.84 | 0.58 |

| ED NIHSS ≥ 10 | 0.56 | 0.85 | 0.66 | 0.86 | 0.52 | 0.59 | 0.84 | 0.67 | 0.88 | 0.50 |

In 2-way comparisons of accuracy values among all instruments, differences reaching nominal p values <0.05 favored the ED LAMS, 3i-SS, and FAST-ED over VAN, for detecting LVO among all cerebral ischemia patients; and the ED LAMS, RACE, 3i-SS, PASS, and FAST-ED over VAN for detecting CSC-appropriate among all suspected stroke patients (DeLong test). P values exceeded 0.05 for all other comparisons.

Discussion

This study provides prospective validation of the Los Angeles Motor Scale performed by paramedics in the field as a useful tool to identify individuals with large vessel occlusions among all acute cerebral ischemia patients; and to identify both types of CSC-appropriate patients, those with symptoms due to LVO acute cerebral ischemia or acute intracranial hemorrhage, among all suspected stroke transports. A LAMS score of 4 or higher doubled, and a LAMS score of 0–3 halved, the likelihood that a patient was among the target group. In addition, this study provides perspective on the comparative performance of the LAMS and other scales for LVO-recognition, when performed concurrently shortly after Emergency Department arrival. The LAMS was comparable or superior to 6 alternative, more complicated scales that have been suggested for pre-hospital or ED use, and comparable to the full NIH Stroke Scale.

This field validation study confirms and extends the findings of the initial derivation study of the LAMS for LVO recognition.6 Whereas the derivation study was based on patients examined by physicians in the ED, the current study confirms that the LAMS has value in identifying LVOs among all cerebral ischemia patients when actually performed by paramedics in the field, and also demonstrates scale value in identifying all CSC-Appropriate patients (LVO AIS plus ICH) among all stroke transports. Though the LAMS showed fair performance, comparable or superior to other proposed scales and the full NIHSS, the accuracy of the LAMS for LVO recognition was less in the current study than in the derivation study, likely for several reasons. The derivation study included not only 911 EMS-transported patients, but also patients arriving by private vehicle, who are likely to have mild deficits and non-LVO strokes, and patients arriving by interfacility transport, who are likely to have severe deficits and LVO strokes. All scales are likely to perform better in such broad cohorts than in a pure 911 EMS-transported patient population, with less representation of mild deficit, non-LVO and severe deficit, LVO extremes. In addition, the derivation study, performed in the era prior to current mechanical endovascular technology, evaluated scale performance in identifying LVOs and MVOs combined, rather than just LVOs.

Notably in the current study, the LAMS performed pre-hospital by paramedics had higher sensitivity, though lower specificity, for LVO than the LAMS performed after arrival in the ED. This pattern likely reflects the frequent occurrence of spontaneous improvement in neurologic deficits among acute cerebral ischemia patients very early after onset,22, 23 and may reflect in some cases actual spontaneous lysis of an LVO between the time of paramedic assessment and ED arrival.24

The comparative performance in this study of the prehospital scales for LVO recognition largely accords with prior investigations. In the largest prior comparative study, analyzing scales performed by physicians in the ED in patients receiving IV tPA, the LAMS, C-STAT, PASS, and RACE all performed comparably in LVO recognition, while the 3i-SS had less sensitivity and greater specificity.11 In another study of consecutive stroke alert patients examined by physicians in the ED, the LAMS, FAST-ED, PASS, and RACE all performed comparably in LVO recognition, while the C-STAT had a lower c statistic.25 Our study similarly shows the LAMS performing comparably or better than other proposed scales.

Few prior studies have analyzed actual performance of an LVO recognition scale when applied by paramedics in the field. In one study, the RACE was evaluated among patients transported by paramedics, but the scale was completed in only 40% of transports, and 18% of patients with completed scales were interfacility transfers rather than direct field responses.12 In addition, CTA, MRA, or catheter angiography were obtained only when there was clinical suspicion of LVO, and were performed in only 23% of patients. In this selected population, the pre-hospital RACE performed with comparable accuracy to the pre-hospital LAMS in the current study (0.72 vs 0.72). In the current study, after ED arrival, the RACE showed lesser accuracy than the concurrently performed LAMS (0.65 vs 0.70). In another study, the C-STAT was performed by paramedics among patients transported during a 6 month period to one stroke center, but C-STAT values were incomplete in 23%, hospital evaluation information missing in 7%, and performance was not assessed in the 7% of patients with subsequent improvement.26 Among the remaining 17 patients, the pre-hospital C-STAT performed with comparable accuracy to the pre-hospital LAMS in the current study (0.71 vs 0.72). In the current study, after ED arrival, the C-STAT showed comparable accuracy to the concurrently performed LAMS (0.68 vs 0.70).

It should not be surprising that, in an acute EMS-transported population, the LAMS, a pure motor assessment, performs comparably in LVO identification to more complex instruments that assess “cortical” findings, such as aphasia, hemineglect, gaze deviation, and visual field defects. First, in acute ischemic stroke, great preponderance of patients with severe motor deficits also have cortical deficits and large vessel occlusions.27, 28 The syndrome of pure motor hemiparesis due to small deep infarcts accounts for only 7% of ischemic stroke presentations.28 Second, some patients with small deep infarcts present with “cortical signs” of aphasia, neglect, gaze deviation, and visual field defect, as language, spatial attention, gaze control, and vision arise from distributed large scale neurocognitive networks in the brain that have subcortical as well as cortical nodes.29–31 Third, presentation of ischemic stroke with isolated aphasia, neglect, and visual field deficits, sparing motor deficits, is uncommon, likely even more uncommon among early activators of the 911 EMS system, and often reflects distal, medium vessel occlusions rather than proximal large vessel occlusions.32, 33 Reflecting these complexities, a detailed analysis of patterns of cortical and elementary findings on the NIHSS in 1085 acute, anterior circulation ischemic stroke patients was unable to identify any pattern of deficits that had enhanced value in detecting the presence of LVO.34 Also of note, all of the LVO recognition scales except the VAN have motor as well as non-motor items, and moderate severe pure motor hemiparesis, with or without result dysarthria, will score high enough to indicate LVO presence, despite the lacunar syndrome presentation, not only on the LAMS, but also 3 of the scales (FAST-ED, RACE, NIHSS).

While the preponderance of prior studies have focused upon LVO recognition, the current study additionally analyzed scale utility in identifying CSC-appropriate patients, defined as patients with either acute ischemic stroke due to LVO or acute intracranial hemorrhage. Intracranial hemorrhage patients typically present with more severe deficits than ischemic stroke patients, and are over-represented in the EMS-transported population as they more often access the 911 system early, reflecting their more severe deficits and more frequent occurrence of headache.16 Accordingly, LVO recognition instruments that reflect greater deficit severity will also disproportionately select intracranial hemorrhage patients for direct transport to CSCs. When CSCs are relatively close to the ambulance point of origin, direct transport to the comprehensive center is desirable. Intracranial hemorrhage patients benefit from the more advanced neurosurgical, neuroendovascular, and neurocritical care services available at CSCs, often in a time-urgent fashion, and interfacility transfer from a PSC to a CSC can be delayed in some jurisdictions.35, 36 Accordingly, in the current analysis, we included patients with ICH along with patients with LVO AIS in the CSC-Appropriate category.

All of the LVO-recognition instruments tested in the current study showed only moderate, rather than high, accuracy, including the current gold standard scale of the full NIHSS. Deficits on physical examination in stroke patients reflect not only the site of vessel occlusion, but also several additional features, including the adequacy of collateral flow, the eloquence of the particular neuroanatomic fields supplied, and pre-existing deficits from prior strokes and neurologic diseases. Nonetheless, while not providing definitive diagnostic information, scale performance is in a range useful for the application of determining patient routing in the field.37 A positive LAMS (4 or higher) more than increases the likelihood a patient harbors a CSC-appropriate lesion by 2.5-fold and a negative LAMS reduces the likelihood by nearly two-thirds.

This study has limitations. Study entry in FAST-MAG required the presence of at least a minor motor deficit, precluding enrollment of patients with pure aphasia or pure hemi-neglect. This may have advantaged scales the 7 scales that used motor items and disadvantaged the VAN scale that did not. However, the frequency of isolated aphasia and neglect presentations is uncommon in acute ischemic stroke, and generally reflects medium rather than large vessel occlusion.32, 33 Study entry in FAST-MAG also required physician phone screen of the patient, in addition to paramedic assessment. As a result, the frequency of stroke mimics among suspected stroke transports may have been reduced in the present study. As mimic patients typically have more minor deficits and no LVO, a reduction in their numbers may have led to underestimation of the specificity of all tested scales for LVO detection. The study focused upon patients encountered by paramedics within 2 hours of onset. Additional studies are needed to determine if the relation between prehospital LVO scale scores and confirmed LVO on arrival is similar or differs in later-presenting patients. Nonetheless, the current study findings are of direct value, as one-half of all EMS-transported ischemic stroke patients in the US are encountered by paramedics within 2 hour of onset.38 The study sample size was moderate, and patients were transported by several ambulances from multiple EMS provider agencies, but within one geographic region to one receiving stroke center. The patients at the receiving center in this study were very similar in demographic and clinical features to patients transported to other centers in the trial.15 Nonetheless, larger, multicenter validation studies are desirable.

We conclude that the Los Angeles Motor Scale performed in the field by paramedics shows good sensitivity and specificity in identifying LVO AIS patients among all cerebral ischemia patients and in identifying CSC-Appropriate patients among all stroke transports. A positive LAMS result more than doubles the likelihood a patient is in a target category, while a negative result decreases by more than half the likelihood a patient is in a target category. The 3 motor-item LAMS is brief and simple for prehospital personnel to perform, and performs comparably or better than more extended prehospital scales and the full NIHSS in identifying LVO AIS and CSC-Appropriate patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

None

Sources of Funding: This study was supported by an Award from the National Institutes of Health (NIH-NINDS U01 NS 44364).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest/Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Alberts MJ, Latchaw RE, Selman WR, Shephard T, Hadley MN, Brass LM, et al. Recommendations for comprehensive stroke centers: A consensus statement from the brain attack coalition. Stroke. 2005;36:1597–1616. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000170622.07210.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higashida R, Alberts MJ, Alexander DN, Crocco TJ, Demaerschalk BM, Derdeyn CP, et al. Interactions within stroke systems of care: A policy statement from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2013;44:2961–2984. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182a6d2b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saver JL, Goyal M, van der Lugt A, Menon BK, Majoie CB, Dippel DW, et al. Time to treatment with endovascular thrombectomy and outcomes from ischemic stroke: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:1279–1288. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.13647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Heart/Stroke Association Mission Lifeline Stroke Committee. Severity-based stroke triage algorithm for ems. 2017:2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaidi SF, Shawver J, Espinosa Morales A, Salahuddin H, Tietjen G, Lindstrom D, et al. Stroke care: Initial data from a county-based bypass protocol for patients with acute stroke. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nazliel B, Starkman S, Liebeskind DS, Ovbiagele B, Kim D, Sanossian N, et al. A brief prehospital stroke severity scale identifies ischemic stroke patients harboring persisting large arterial occlusions. Stroke. 2008;39:2264–2267. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.508127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llanes JN, Kidwell CS, Starkman S, Leary MC, Eckstein M, Saver JL. The los angeles motor scale (lams): A new measure to characterize stroke severity in the field. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2004;8:46–50. doi: 10.1080/312703002806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JT, Chung PW, Starkman S, Sanossian N, Stratton SJ, Eckstein M, et al. Field validation of the los angeles motor scale as a tool for paramedic assessment of stroke severity. Stroke. 2017;48:298–306. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singer OC, Dvorak F, du Mesnil de Rochemont R, Lanfermann H, Sitzer M, Neumann-Haefelin T. A simple 3-item stroke scale: Comparison with the national institutes of health stroke scale and prediction of middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2005;36:773–776. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000157591.61322.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz BS, McMullan JT, Sucharew H, Adeoye O, Broderick JP. Design and validation of a prehospital scale to predict stroke severity: Cincinnati prehospital stroke severity scale. Stroke. 2015;46:1508–1512. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hastrup S, Damgaard D, Johnsen SP, Andersen G. Prehospital acute stroke severity scale to predict large artery occlusion: Design and comparison with other scales. Stroke. 2016;47:1772–1776. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez de la Ossa N, Carrera D, Gorchs M, Querol M, Millan M, Gomis M, et al. Design and validation of a prehospital stroke scale to predict large arterial occlusion: The rapid arterial occlusion evaluation scale. Stroke. 2014;45:87–91. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lima FO, Silva GS, Furie KL, Frankel MR, Lev MH, Camargo EC, et al. Field assessment stroke triage for emergency destination: A simple and accurate prehospital scale to detect large vessel occlusion strokes. Stroke. 2016;47:1997–2002. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teleb MS, Ver Hage A, Carter J, Jayaraman MV, McTaggart RA. Stroke vision, aphasia, neglect (van) assessment-a novel emergent large vessel occlusion screening tool: Pilot study and comparison with current clinical severity indices. J Neurointerv Surg. 2017;9:122–126. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2015-012131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saver JL, Starkman S, Eckstein M, Stratton SJ, Pratt FD, Hamilton S, et al. Prehospital use of magnesium sulfate as neuroprotection in acute stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:528–536. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saver JL, Starkman S, Eckstein M, Stratton S, Pratt F, Hamilton S, et al. Methodology of the field administration of stroke therapy - magnesium (fast-mag) phase 3 trial: Part 1 - rationale and general methods. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:215–219. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saver JL, Starkman S, Eckstein M, Stratton S, Pratt F, Hamilton S, et al. Methodology of the field administration of stroke therapy - magnesium (fast-mag) phase 3 trial: Part 2 - prehospital study methods. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:220–225. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer U, Arnold M, Nedeltchev K, Brekenfeld C, Ballinari P, Remonda L, et al. Nihss score and arteriographic findings in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:2121–2125. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000182099.04994.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heldner MR, Zubler C, Mattle HP, Schroth G, Weck A, Mono ML, et al. National institutes of health stroke scale score and vessel occlusion in 2152 patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2013;44:1153–1157. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3:32–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::aid-cncr2820030106>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El Khouli RH, Macura KJ, Barker PB, Habba MR, Jacobs MA, Bluemke DA. Relationship of temporal resolution to diagnostic performance for dynamic contrast enhanced mri of the breast. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30:999–1004. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saver JL, Altman H. Relationship between neurologic deficit severity and final functional outcome shifts and strengthens during first hours after onset. Stroke. 2012;43:1537–1541. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.636928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tipirneni A, Shkirkova K, Sanossian N, Starkman S, Hamilton S, Liebeskind D, et al. Deterioration and improvement in the field: Comparative detection by los angeles motor scale and glasgow coma scale in acute, ems-transported stroke patients. Stroke. 2017;48:ATP235–ATP235. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee VH, John S, Mohammad Y, Prabhakaran S. Computed tomography perfusion imaging in spectacular shrinking deficit. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;21:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao H, Coote S, Pesavento L, Churilov L, Dewey HM, Davis SM, et al. Large vessel occlusion scales increase delivery to endovascular centers without excessive harm from misclassifications. Stroke. 2017;48:568–573. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.016056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMullan JT, Katz B, Broderick J, Schmit P, Sucharew H, Adeoye O. Prospective prehospital evaluation of the cincinnati stroke triage assessment tool. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2017:1–8. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2016.1274349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herman B, Leyten AC, van Luijk JH, Frenken CW, Op de Coul AA, Schulte BP. Epidemiology of stroke in tilburg, the netherlands. The population-based stroke incidence register: 2. Incidence, initial clinical picture and medical care, and three-week case fatality. Stroke. 1982;13:629–634. doi: 10.1161/01.str.13.5.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bogousslavsky J, Van Melle G, Regli F. The lausanne stroke registry: Analysis of 1,000 consecutive patients with first stroke. Stroke. 1988;19:1083–1092. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.9.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carrera E, Bogousslavsky J. The thalamus and behavior: Effects of anatomically distinct strokes. Neurology. 2006;66:1817–1823. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219679.95223.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caplan LR, Schmahmann JD, Kase CS, Feldmann E, Baquis G, Greenberg JP, et al. Caudate infarcts. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:133–143. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530020029011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaditis DG, Zintzaras E, Sali D, Kotoulas G, Papadimitriou A, Hadjigeorgiou GM. Conjugate eye deviation as predictor of acute cortical and subcortical ischemic brain lesions. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2016;143:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denier C, Chassin O, Vandendries C, Bayon de la Tour L, Cauquil C, Sarov M, et al. Thrombolysis in stroke patients with isolated aphasia. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;41:163–169. doi: 10.1159/000442303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strbian D, Ahmed N, Wahlgren N, Kaste M, Tatlisumak T, Investigators S Intravenous thrombolysis in ischemic stroke patients with isolated homonymous hemianopia: Analysis of safe implementation of thrombolysis in stroke-international stroke thrombolysis register (sits-istr) Stroke. 2012;43:2695–2698. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.658435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heldner MR, Hsieh K, Broeg-Morvay A, Mordasini P, Buhlmann M, Jung S, et al. Clinical prediction of large vessel occlusion in anterior circulation stroke: Mission impossible? J Neurol. 2016;263:1633–1640. doi: 10.1007/s00415-016-8180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diringer MN, Edwards DF. Admission to a neurologic/neurosurgical intensive care unit is associated with reduced mortality rate after intracerebral hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:635–640. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200103000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adeoye O, Haverbusch M, Woo D, Sekar P, Moomaw CJ, Kleindorfer D, et al. Is ed disposition associated with intracerebral hemorrhage mortality? Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:391–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Sackett DL. Users’ guides to the medical literature. Iii. How to use an article about a diagnostic test. B. What are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? The evidence-based medicine working group. JAMA. 1994;271:703–707. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.9.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ekundayo OJ, Saver JL, Fonarow GC, Schwamm LH, Xian Y, Zhao X, et al. Patterns of emergency medical services use and its association with timely stroke treatment: Findings from get with the guidelines-stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:262–269. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.