Abstract

Flavonoids are phytochemicals which can regulate the activity of the intestinal immune system. In patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) there is an overexpression and imbalance of the components of the inflammatory immune reactions which are chronically activated. Suppression of inflammation can be achieved by anti-inflammatory drugs which are used in clinical medicine but these can cause serious side effects. Flavonoids can have natural immunosuppressive properties and inhibit the activation of immune cells and its effectors (chemokines, TNF-, cytokines). Phytochemicals such as flavonoids bind to the nuclear Ah (aryl hydrocarbon) -receptor thereby stimulating protective enzyme activities. As shown by clinical evidence in patients and by experimental work some flavonoids (apigenin, epigallocatechin gallate) were effective in the inhibition of inflammation. Instead of or additionally to anti-inflammatory drugs flavonoids can be used in IBD patients to treat the over-reactive immunologic system. This is accomplished by upregulation of the Ah-receptor. Flavonoids interact with toll-like receptors expressing on the surface of immune cells, then they were internalized to the cytosol and transferred into the nucleus, where they were attached to the Ah-receptor. The Ah-receptor binds to the Ah-R nuclear translocator and via Ah response element beneficial protective enzymes and cytokines are induced, leading to upregulation of the anti-inflammatory system.

Keywords: Flavonoids, Inflammatory bowel disease, Ah-receptor

Core tip: Overview regulation of the intestinal immune system by flavonoids and its utility in chronic inflammatory bowel disease.

INTRODUCTION

Disturbances of the intestinal immune system can lead to chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) including Crohn`s disease and ulcerative colitis (UC)[1,2]. Inappropriate chronic stimulation of the native and adoptive immune-system induces an inflammatory reaction of the epithelial mucosa in the rectum, as well as in small and large bowel. There exists only limited evidence about the cause of this reaction which includes bacterial overproduction, defective barrier function, genetic and environmental aberrations.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

While the pathophysiology of the inflammatory changes is quite well explained the level of the immune reaction is not sufficiently delineated. This level might be determined by factors which regulate the degree of the immune reactions. These regulatory factors could be responsible for the activity of the inflammatory immune reaction and should be identified. Phytochemicals and among them polyphenols and flavonoids can influence various components of immune system and thereby determine the disease activity in IBD and in experimental colitis[3,4].

There is a plethora of clinical studies and experimental results on the association between colorectal cancer (CRC)[5] and exposure to phytochemicals especially flavonoids[6]. It is still not yet clear whether these xenobiotics could play a role in the development of intestinal neoplasia. Most studies indicate that dietary components from fruits and vegetables lower the risk of CRC and other tumors[7,8]. Flavonoids among other phytochemicals could prevent CRC[9] and its precursors (colonic adenomas, dysplasia and aberrant crypt foci) by long term preneoplastic dietary exposure. It is now accepted that chronic inflammatory changes of the intestinal mucosa predate neoplasia and that treatment of the inflammation and identification of its etiologic factors are necessary for cancer prevention.

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY EFFECTS OF FLAVONOIDS

In chronic inflammatory reactions the intestinal mucosa and the submucosa contain 2 components which are responsible for immune activation: The innate system and the adoptive system both of which contribute to the degree of activation. Whereas immune cells such as dendritic cells, granulocytes, macrophages, natural killer cells and mast cells belong to the innate immune system the adaptive system includes T-lymphocytes, B-lymphocytes and plasma cells and immunoglobulins. Innate immunocytes are activated into myeloic and plasmacytoid dentritic cells. Naïve lymphocytes are activated into T-helper cells, cytotoxic T-cells, regulatory T-cells and active B-cells. Inflammatory signals are the main factors for immune activation. Flavonoids are natural inhibitors and can prevent the activation of the innate and adaptive immune system[10]. Some flavonoids such as tea flavonoids (apigenin and epigallocathechin gallate) have been found to prevent the activation of immune cells and its effectors (chemokines, TNF-α and cytokines)[11].

In vivo the anti-inflammatory effects were shown by inhibition of transcriptions factors like nuclear factor ‘kappa-light-chain-enhancer’ of activated B-cells (NF-κB) and by suppression of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) enzymes[12]. In patients with IBD chemokines and chemokine receptors are increased[13]. Phytochemicals have been shown to suppress inflammatory signal transduction systems leading to autophagy and apoptosis[14].

INFLUENCE OF FLAVONOIDS ON THE MICROBIOTA

Dysbalance of the microflora has been found in patients with IBD and chronic diarrhea[15]. The microbiota shows less variability and abundance of certain bacteria such as prevotellaceae and sulfide producing bacteria. Dietetic flavonoids can improve the fecal microbiota and prevent diarrhea. A recent study indicates that in pediatric patients the fecal microflora is related to diet and the composition of the microbiota indicates a pre-inflammatory status of IBD[16].

FLAVONOIDS AND MICROSOMAL ENZYMES

Dietary xenobiotics such as phytochemicals seem to be involved in the pathogenesis and treatment of chronic IBD[17]. Flavonoids are substrates for certain cytochrome P-450 enzymes (including CYP1A1) and are metabolized by components of the proteasome (P), endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria (M), called PERM hypothesis[18]. This PERM concept defines the functional structure, which regulates the survival decision of cells under stress situation. Most probably this dynamic system can act as a single master tuner of cellular decisions about life or death, in order to give a chance to the remaining living cells in an organism. The ER consists of cytochrome P-450 and conjugating enzymes which metabolically break down toxic compounds. Human cytochrome 3A4 and 2C9 enzymes are inhibited by flavonoids in vitro but can also be induced in vivo[19,20]. These enzymes could be biomarkers for the activity of the PERM system, indicate moderate beneficial induction and a favorable immune status. Flavonoid mediated induction is a positive event for the immune system boosting its anti-inflammatory activity. In the intestine of IBD patients the CYP 1A1 enzymes were upregulated[21].

FLAVONOIDS AND PERM

An intracellular mechanism exists for the detoxification of reactive oxygen radicals, which are taken care of by the proteasome, the ER and the mitochondria[18] acting as PERM system. Flavonoids can activate this system as stressing and signaling molecules and are thereby responsible for the suppression of “pathologic” stress. Patients with IBD could probably benefit from dietary flavonoids supplementation[10,22].

FLAVONOIDS REGULATE THE AH-RECEPTOR

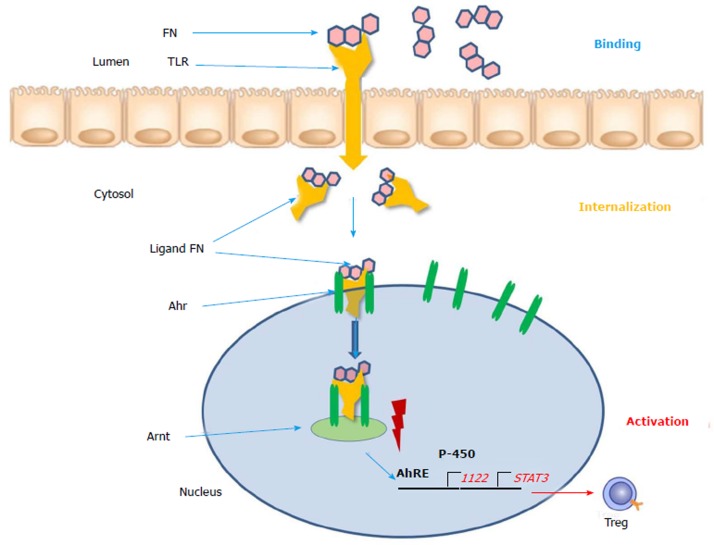

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Ahr) functions as intracellular transcription factor for the action of flavonoids and other phytochemicals such as indoles, isothiocyanates, cruciferous plants and cabbage products (Figure 1)[21]. During the passage through the gastrointestinal tract digestion takes place and flavonoids are broken metabolically down into smaller molecules. FN (flavonoids) present in the gut lumen bind to the toll-like receptor of the plasma membrane and are transported into the cytosol. Here as a ligand they are attached to the Ahr and triggers translocation into the cell nucleus. Via dimerization with the Ahr nuclear translocator (Arnt) protein the ligand FN-Ahr-Arnt complex binds to the AhRE (Ah response Element) found in the 5 V flanking region of numerous genes. This element activates the target genes which are transcript into cytochrome P-450 and other protective enzymes. Additionally, regulatory T-cells, STAT3 and IL-22 are expressed and upregulated. The Ahr is localized mainly in lymphocytes and dendritic cells of the intestinal mucosa. Interleukin-22 is responsible for the intestinal integrity and the production of mucus and upregulation of beta-defensin-2[23]. The FN ligand is the major immune modulator and induces a beneficial pattern of cytokines and immune cells which counteract the inflammatory alterations of the intestinal mucosa. In contrast to the biologicals these botanicals do not require an immunosuppressive therapy and constitute natural inducers of the immune system[24]. As plant products (xenobiotica) they could be used as an anti-inflammatory diet and could be beneficial for prevention and as nutritional supplements[10].

Figure 1.

Simplified scheme of the gene regulation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Flavonoids bind to the toll-like receptor in the lumen and get internalized to the cytosol. Then the complex functions as a ligand for the Ah receptor, which results in the release of associated proteins and translocation to the nucleus followed by dimerization with Arnt. The Ahr/Arnt complex binds the AhRE promoting target gene transcription like upregulation of IL-22, cytochrome P-450 and PERM activity as well as downregulation of STAT3 and NF-κB. The ligands can also exert their effects in the cytoplasm through AhR-associated protein kinases to alter the function of a variety of proteins through a cascade of protein phosphorylation. Ahr: Aryl hydrocarbon receptor; Arnt: Ahr nuclear translocator; Ah: Aryl hydrocarbon.

EVIDENCE OF INHIBITION OF INTESTINAL INFLAMMATION BY FLAVONOIDS

Diets could be beneficial in the treatment of IBD[25]. Dietary flavonoids could play a prominent role as part of a healthy diet[26]. There are several experimental studies which indicate the utility of flavonoids in models of chronic IBD[27-31]. Especially the effects on the various aspects and consequences of inflammation (barrier integrity and microbiota) have been explained. The therapeutic benefits of cathechins are mediated by glutathione peroxidase, glutathione and by downregulation of immune cells of the innate and induced system and their related signaling pathways (NF-κB, MAPK`s)[32].

Regular dietary consumption of green tea extract (epigallocathechin gallate) reduces DNA damage and increases the anti-oxidative capacity of blood plasma[33].

In UC chamomile extract (apigenin) given as a nutritional supplement was capable of remission maintenance. This was shown in a placebo controlled prospective trial[34]. In a similar study this could also be found for curcumin (which is a polyphenol) treatment.

Apigenin K was used in two different experimental colitis models and showed intestinal anti-inflammatory activity[35]. Furthermore, apigenin, as a nutritional supplementary flavonoid, can suppress NF-κB regulated expression of anti-apoptotic COX-2 and cFLIP in activated human T cells. Thus, apigenin is a possible interesting potent inhibitor which can be used for autoimmune inflammatory disease therapy, although the problem of bioavailability can be solved in the future[36].

In a study by Najafzadeh et al[37] flavonoids, especially quercetin and epicatechin, inhibits the DNA damage potency of H2O2 and IQ (quinoline) in lymphocytes isolated from IBD patients[38] in vitro experiments to 48% and 43% in comparison to controls. Here a concentration of 250 µg/mL quercetin and 100 µg/mL epicatechin is sufficient, respectively.

CONCLUSION

Flavonoids are able to influence the intestinal immune system and to regulate the strength and the pattern of the immune response in patients with chronic intestinal inflammation. Flavonoids drive the inflammatory cytokines into regression. The transcription factor Ah-R regulates the expression of target genes for the anti-inflammatory activity of the flavonoids.

Clinical trials in patients with IBD with valid endpoints to measure the outcome with and without flavonoid treatment are rare and should be done soon.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Peer-review started: October 26, 2017

First decision: November 14, 2017

Article in press: December 27, 2017

P- Reviewer: Gheita TAA, Ogata H, Vradelis S S- Editor: Chen K L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Harald Peter Hoensch, Private Practice Gastroenterology, Marien hospital, Darmstadt 64285, Germany.

Benno Weigmann, Department of Medicine 1, University Medical Center, Erlangen 91052, Germany. benno.weigmann@uk-erlangen.de.

References

- 1.Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease (1) N Engl J Med. 1991;325:928–937. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199109263251306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease (2) N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1008–1016. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110033251406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aldini R, Micucci M, Cevenini M, Fato R, Bergamini C, Nanni C, Cont M, Camborata C, Spinozzi S, Montagnani M, et al. Antiinflammatory effect of phytosterols in experimental murine colitis model: prevention, induction, remission study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Somani SJ, Modi KP, Majumdar AS, Sadarani BN. Phytochemicals and their potential usefulness in inflammatory bowel disease. Phytother Res. 2015;29:339–350. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kornfeld D, Ekbom A, Ihre T. Is there an excess risk for colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis and concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis? A population based study. Gut. 1997;41:522–525. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.4.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scalbert A, Zamora-Ros R. Bridging evidence from observational and intervention studies to identify flavonoids most protective for human health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101:897–898. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.110205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li YH, Niu YB, Sun Y, Zhang F, Liu CX, Fan L, Mei QB. Role of phytochemicals in colorectal cancer prevention. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9262–9272. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i31.9262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwingshackl L, Schwedhelm C, Hoffmann G, Knüppel S, Laure Preterre A, Iqbal K, Bechthold A, De Henauw S, Michels N, Devleesschauwer B, et al. Food groups and risk of colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2017 doi: 10.1002/ijc.31198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoensch HP, Kirch W. Potential role of flavonoids in the prevention of intestinal neoplasia: a review of their mode of action and their clinical perspectives. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2005;35:187–195. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:35:3:187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoensch HP, Oertel R. The value of flavonoids for the human nutrition: Short review and perspectives. Clinical Nutrition Experimental. 2015;3:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cialdella-Kam L, Ghosh S, Meaney MP, Knab AM, Shanely RA, Nieman DC. Quercetin and Green Tea Extract Supplementation Downregulates Genes Related to Tissue Inflammatory Responses to a 12-Week High Fat-Diet in Mice. Nutrients. 2017;9 doi: 10.3390/nu9070773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruiz PA, Braune A, Hölzlwimmer G, Quintanilla-Fend L, Haller D. Quercetin inhibits TNF-induced NF-kappaB transcription factor recruitment to proinflammatory gene promoters in murine intestinal epithelial cells. J Nutr. 2007;137:1208–1215. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.5.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyazaki H, Takabe K, Yeudall WA. Chemokines, chemokine receptors and the gastrointestinal system. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2847–2863. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i19.2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Talero E, Ávila-Roman J, Motilva V. Chemoprevention with phytonutrients and microalgae products in chronic inflammation and colon cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:3939–3965. doi: 10.2174/138161212802083725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magrone T, Jirillo E. The interplay between the gut immune system and microbiota in health and disease: nutraceutical intervention for restoring intestinal homeostasis. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:1329–1342. doi: 10.2174/138161213804805793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sommer F, Rühlemann MC, Bang C, Höppner M, Rehman A, Kaleta C, Schmitt-Kopplin P, Dempfle A, Weidinger S, Ellinghaus E, et al. Microbiomarkers in inflammatory bowel diseases: caveats come with caviar. Gut. 2017;66:1734–1738. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J, Choi J, Kim S. Effective suppression of pro-inflammatory molecules by DHCA via IKK-NF-κB pathway, in vitro and in vivo. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:3353–3369. doi: 10.1111/bph.13137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chirumbolo S, Bjørklund G. PERM Hypothesis: The Fundamental Machinery Able to Elucidate the Role of Xenobiotics and Hormesis in Cell Survival and Homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017:18. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moon YJ, Wang X, Morris ME. Dietary flavonoids: effects on xenobiotic and carcinogen metabolism. Toxicol In Vitro. 2006;20:187–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimura Y, Ito H, Ohnishi R, Hatano T. Inhibitory effects of polyphenols on human cytochrome P450 3A4 and 2C9 activity. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klotz U, Ammon E. Clinical and toxicological consequences of the inductive potential of ethanol. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54:7–12. doi: 10.1007/s002280050412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carini F, Tomasello G, Jurjus A, Geagea A, Al Kattar S, Damiani P, Sinagra E, Rappa F, David S, Cappello F, et al. Colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel diseases: effects of diet and antioxidants. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2017;31:791–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li A, Gan Y, Wang R, Liu Y, Ma T, Huang M, Cui X. IL-22 Up-Regulates β-Defensin-2 Expression in Human Alveolar Epithelium via STAT3 but Not NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Inflammation. 2015;38:1191–1200. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-0083-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Food, immunity, and the microbiome. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1107–1119. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sigall-Boneh R, Levine A, Lomer M, Wierdsma N, Allan P, Fiorino G, Gatti S, Jonkers D, Kierkus J, Katsanos KH, et al. Research Gaps in Diet and Nutrition in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. A Topical Review by D-ECCO Working Group [Dietitians of ECCO] J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:1407–1419. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sebastian RS, Wilkinson Enns C, Goldman JD, Martin CL, Steinfeldt LC, Murayi T, Moshfegh AJ. A New Database Facilitates Characterization of Flavonoid Intake, Sources, and Positive Associations with Diet Quality among US Adults. J Nutr. 2015;145:1239–1248. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.213025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vezza T, Rodríguez-Nogales A, Algieri F, Utrilla MP, Rodriguez-Cabezas ME, Galvez J. Flavonoids in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review. Nutrients. 2016;8:211. doi: 10.3390/nu8040211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gil-Cardoso K, Ginés I, Pinent M, Ardévol A, Blay M, Terra X. Effects of flavonoids on intestinal inflammation, barrier integrity and changes in gut microbiota during diet-induced obesity. Nutr Res Rev. 2016;29:234–248. doi: 10.1017/S0954422416000159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dou W, Zhang J, Ren G, Ding L, Sun A, Deng C, Wu X, Wei X, Mani S, Wang Z. Mangiferin attenuates the symptoms of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice via NF-κB and MAPK signaling inactivation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;23:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mascaraque C, Aranda C, Ocón B, Monte MJ, Suárez MD, Zarzuelo A, Marín JJ, Martínez-Augustin O, de Medina FS. Rutin has intestinal antiinflammatory effects in the CD4+ CD62L+ T cell transfer model of colitis. Pharmacol Res. 2014;90:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui L, Feng L, Zhang ZH, Jia XB. The anti-inflammation effect of baicalin on experimental colitis through inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB pathway activation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;23:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan FY, Sang LX, Jiang M. Catechins and Their Therapeutic Benefits to Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Molecules. 2017:22. doi: 10.3390/molecules22030484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ellinger S, Müller N, Stehle P, Ulrich-Merzenich G. Consumption of green tea or green tea products: is there an evidence for antioxidant effects from controlled interventional studies? Phytomedicine. 2011;18:903–915. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langhorst J, Varnhagen I, Schneider SB, Albrecht U, Rueffer A, Stange R, Michalsen A, Dobos GJ. Randomised clinical trial: a herbal preparation of myrrh, chamomile and coffee charcoal compared with mesalazine in maintaining remission in ulcerative colitis--a double-blind, double-dummy study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:490–500. doi: 10.1111/apt.12397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mascaraque C, González R, Suárez MD, Zarzuelo A, Sánchez de Medina F, Martínez-Augustin O. Intestinal anti-inflammatory activity of apigenin K in two rat colitis models induced by trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid and dextran sulphate sodium. Br J Nutr. 2015;113:618–626. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514004292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu L, Zhang L, Bertucci AM, Pope RM, Datta SK. Apigenin, a dietary flavonoid, sensitizes human T cells for activation-induced cell death by inhibiting PKB/Akt and NF-kappaB activation pathway. Immunol Lett. 2008;121:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Najafzadeh M, Reynolds PD, Baumgartner A, Anderson D. Flavonoids inhibit the genotoxicity of hydrogen peroxide (H(2)O(2)) and of the food mutagen 2-amino-3-methylimadazo[4,5-f]-quinoline (IQ) in lymphocytes from patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) Mutagenesis. 2009;24:405–411. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gep016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boots AW, Wilms LC, Swennen EL, Kleinjans JC, Bast A, Haenen GR. In vitro and ex vivo anti-inflammatory activity of quercetin in healthy volunteers. Nutrition. 2008;24:703–710. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]