Abstract

PURPOSE

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of abutment diameter, cement type, and re-cementation on the retention of implant-supported CAD/CAM metal copings over short abutments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sixty abutments with two different diameters, the height of which was reduced to 3 mm, were vertically mounted in acrylic resin blocks with matching implant analogues. The specimens were divided into 2 diameter groups: 4.5 mm and 5.5 mm (n=30). For each abutment a CAD/CAM metal coping was manufactured, with an occlusal loop. Each group was sub-divided into 3 sub-groups (n=10). In each subgroup, a different cement type was used: resin-modified glass-ionomer, resin cement and zinc-oxide-eugenol. After incubation and thermocycling, the removal force was measured using a universal testing machine at a cross-head speed of 0.5 mm/min. In zinc-oxide-eugenol group, after removal of the coping, the cement remnants were completely cleaned and the copings were re-cemented with resin cement and re-tested. Two-way ANOVA, post hoc Tukey tests, and paired t-test were used to analyze data (α=.05).

RESULTS

The highest pulling force was registered in the resin cement group (414.8 N), followed by the re-cementation group (380.5 N). Increasing the diameter improved the retention significantly (P=.006). The difference in retention between the cemented and recemented copings was not statistically significant (P=.40).

CONCLUSION

Resin cement provided retention almost twice as strong as that of the RMGI. Increasing the abutment diameter improved retention significantly. Re-cementation with resin cement did not exhibit any difference from the initial cementation with resin cement.

Keywords: Implant-supported restorations, Abutment geometry, CAD/CAM coping, Luting agent, Re-cementation

INTRODUCTION

Introduction of endosseous dental implants revolutionized and increased the options for reconstruction of edentulous.1 A primary reason to consider dental implants to replace missing teeth is the maintenance of the alveolar bone.2 Dental implants are utilized to support screw-type or cement-type prostheses.3 Cement-retained prostheses have several advantages over screw-retained prostheses, including force transmission along the long axis of implants, easy superstructure adjustments, absence of prosthesis screw loosening, and superior esthetics.4,5

Retention is a vital feature in the clinical success of fixed restorations.6 Factors affecting retention and resistance form of implant restorations include abutment features, luting agent, and superstructure characteristics.7 Abutment features include the height and width, degree of taper,8 and surface roughness.9,10 Type and composition, consistency, film thickness, and pressure duration while cementation pertain to luting agents' characteristics. Fitness and inner roughness of the superstructure also have a role in retention and resistance.11 Therefore, in addition to implant type, considering types of abutment, luting agent, and superstructure is a major step in making a clinical decision.12

An ideal luting agent provides sufficient retention while preserving the access to the superstructure and abutment without compromising any of them.13 Permanent cements provide superior retention, marginal seal, and bond strength but endanger the retrievability of the components.14 Aggressive techniques in crown removal may lead to crown/abutment screw, abutment, or implant fracture.15 On the other hand, use of temporary cements might yield insufficient strength during function, leaching of the cement and restoration mobility. Therefore a specific luting agent is selected based on the restoration condition.16

Introduction of CAD/CAM (Computer-aided Design/Computer-aided Manufacturing) technology revolutionized the laboratory procedures in dentistry. Conventionally, fabrication of a framework required full anatomic wax-up, cutback, investing, and casting, the steps which were rather time-consuming and needed technician's high skills.17,18 During early developing steps of CAD/CAM, ceramics and polymers were widely utilized. For alloys such as Cr-Co, powerful processing machines were needed due to the hardness of alloy blocks, which in turn made the production and maintenance rather costly.19 Presintered Cr-Co blocks, e.g. Ceramill Sintron; Amann Girrbach, and advanced processing techniques have been introduced recently. These soft blocks are dry-milled and sintered in an Argon atmosphere at a high temperature. The shrinkage volume during sintering is about 11%.17,20

Cemented implant restorations sometimes require re-cementation.21 When an abutment length is not sufficient, retention of the restoration is compromised, especially when it is cement-retained. In these cases, permanent or temporary cements can be used for re-cementation. Different methods have been proposed to clean restorations before re-cementation such as cement removal solutions,22 hand instruments e.g. curettes,23,24 ultrasonic bath with alcohol, sandblasting with alumina particles, etching, and burnout.21,25

Sometimes the interarch space is limited; in such cases shorter abutments can be used to reconstruct the edentulous area. Providing retention is a rather sensitive task in short abutments; therefore, additional retentive features and use of more retentive luting agents ought to be considered.

Rödiger et al. showed that a temporary luting agent is more affected by height and tapering of the abutment than a semi-permanent luting agent.21 According to Cano-Batalla's study, type of cement, sandblasting, and abutment height had a considerable impact on retention although a 1-mm difference in abutment height did not result in any significance.26 On the other hand, in Abbo's study on zirconia copings, a 1-mm decrease in height reduced retention significantly.2 Little evidence is available on the effect of abutment diameter on retention of implant-supported restorations over short abutments.

Since retention is a major concern in short implant abutments, the aim of this study was to investigate the effect of abutment diameter (contact area), type of luting agent, and re-cementation on implant-supported CAD/CAM restorations over short abutments. The null hypothesis was that the different abutment diameters, luting agent types, and recementation do not affect the retention of implant-supported CAD/CAM metal coping over short abutments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this in vitro study, 60 two-piece abutments (Implantium, Dentium, Shrewsburg, UK) were selected.27 Abutment diameters were 4.5 and 5.5 mm. The length of the abutments was initially 5.5 mm, which was reduced to 3 mm by means of a wire cut device.

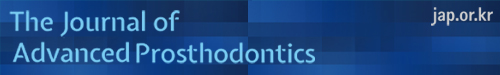

Twenty implant analogs (Implantium, DANSE, Shrewsburg, UK) were vertically mounted in self-cured acrylic resin blocks (Acropars, Marlic, Tehran, Iran) measuring 2.5 cm in diameter and 3 cm in height. The analog alignment was verified by a surveyor. The block surfaces were 1 mm below the abutment-analog junction (Fig. 1).28,29 The abutments were screwed to a 35-N torque force30 with a torque wrench and were subsequently replaced by abutments of the other group, after the test was conducted.

Fig. 1. Shortened abutment in acrylic resin block.

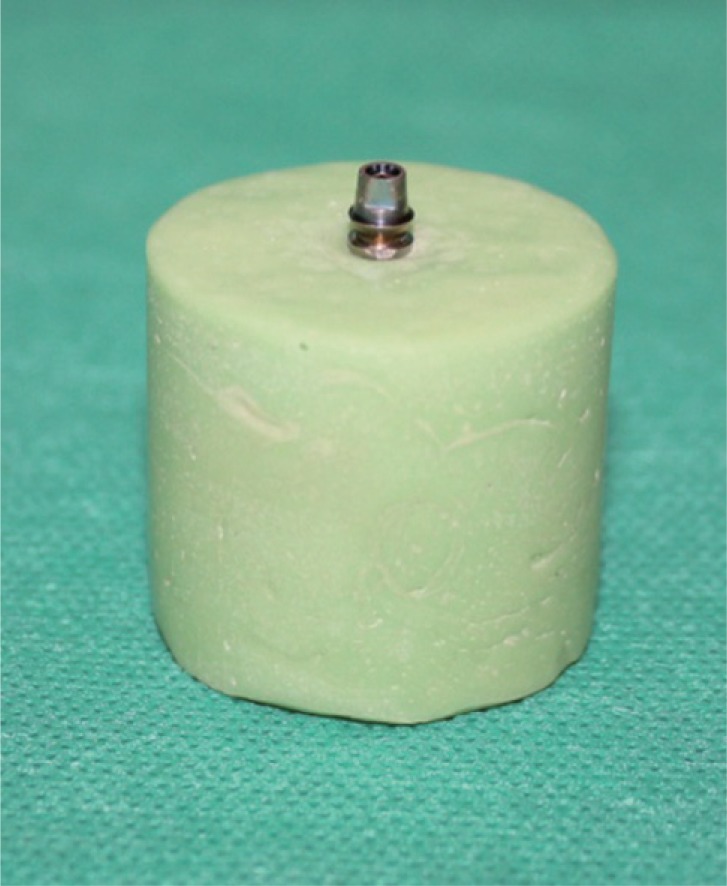

Each abutment was scanned individually (Ceramill Map400, Amann Girrbach, Kolbach, Austria) and a metal coping (Ceramill Sintron, Amann Girrbach, Austria) was fabricated using a CAD/CAM device (Ceramill Motion2 (5X), Amann Girrbach, Austria) with a 30-µm space for the luting agent.30 Each coping was fabricated with an occlusal loop to provide a suitable grip for the universal testing machine (M350-10CT, Rochdale, England) (Fig. 2).21 Marginal fit was evaluated at ×4 magnification under a stereomicroscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and copings with improper fit were excluded.

Fig. 2. CAD/CAM metal coping with occlusal loop.

The copings and abutments were divided into 2 groups (n = 30). Thirty abutments were 4.5 mm and the other thirty were 5.5 mm in diameter. Each group was further sub-divided into 3 sub-groups (n = 10), which differed in cement type. The three cement types used were resin-modified glass-ionomer (RMGI) (Ketac Cem, 3M ESPE, Seefeld, Germany), zinc-oxide-eugenol cement (TemBond, Kerr, Romulus, Italy), and resin cement (Panavia F2.0, Kuraray, Kurashiki, Japan).

All the abutments and copings were cleansed in an ultrasonic bath (Ultrasonic, Bandelin, Super RK102H, Berlin, Germany) containing 96% ethanol and dried afterwards.4 Screw access was filled with Cavit (Cavisol, Golchai Co., Tehran, Iran). Cement mixing and application was performed at room temperature with hand by an operator according to manufacturer's instructions.31 The copings were half-filled with cement and pressed down for 5 seconds for cementation. The specimens were later loaded by a 5-kg force for 10 minutes according to ADA specification No. 96.32 Excess cement was removed with an explorer before complete setting.6

The samples were later submerged in 37℃ distilled water for 24 hours.33 To simulate the oral environment, the samples underwent 1000 thermal cycles at 5 – 55℃ with 30 seconds of dwell time (TC-3000, Tehran, Iran).27

The copings were pulled out at a cross-head speed of 0.5 mm/min in a universal testing machine (Fig. 3). The pull force was applied along the vertical axis of abutment-analog.34 The maximum force required for removal of the coping was reported as maximum retention.

Fig. 3. Pull-out test with a cross-head speed of 0.5 mm/min in the universal testing machine.

In the 20 specimens of temporary cement group, after testing, the temporary cement was cleaned from the intaglio surface of the coping and abutment surfaces. The removal procedure of temporary cement consisted of gross removal with the explorer, ultrasonic bath with ethanol for 15 minutes, and a 30-second application of 37% phosphoric acid for complete removal of cement remnants. The specimens were then rinsed and dried.21 The abutments were also cleaned in an ultrasonic bath for 5 minutes and dried.4 After re-cementation with a resin cement, incubation, and thermocycling, the pull-out test was repeated.

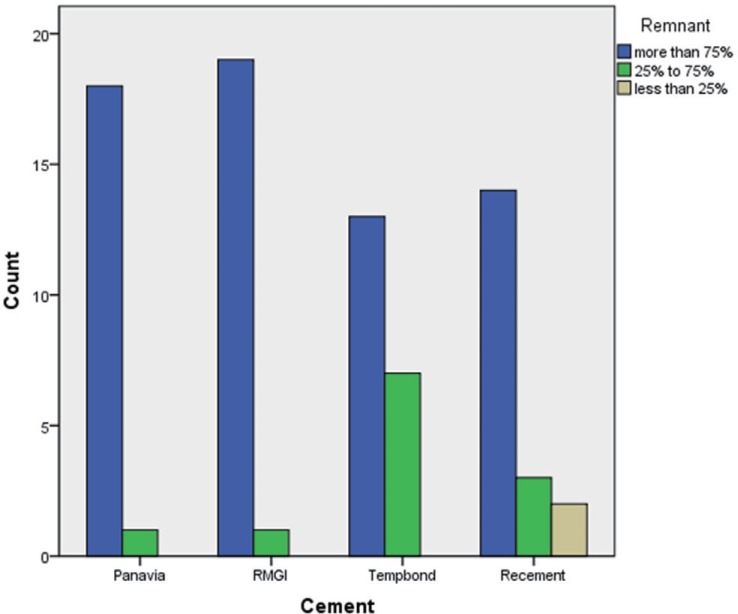

Failure area was investigated under a light microscope (Nikon, Japan) (Fig. 4). Failure modes were classified into three categories: adhesive failure (complete separation of cement from the abutment or coping), cohesive failure (failure within the cement) and mixed failure (a combination of the two above). Since a coping is a combination of several surfaces and the failure mode is different in different surfaces of a coping, the failure modes were categorized as follows: more than 75% of the cement remained on the coping; between 25% and 75% of the cement remained on the coping; less than 25% of the cement remained on the coping.30,35 The axial walls were considered as 4 surfaces and the occlusal wall was considered as one surface, with each surface being considered 20%. The dislodging forces were statistically analyzed with Two-way ANOVA, post hoc Tukey tests, and paired t-test (α = .05).

Fig. 4. Intaglio surfaces of metal coping after pull-out test under a light microscope. (A) RMGI (More the 75% remaining cement on coping surface), (B) Resin cement (Between 25% and 75% remaining cement on coping surface), (C) ZOE (Less than 25% remaining cement on coping surface).

RESULTS

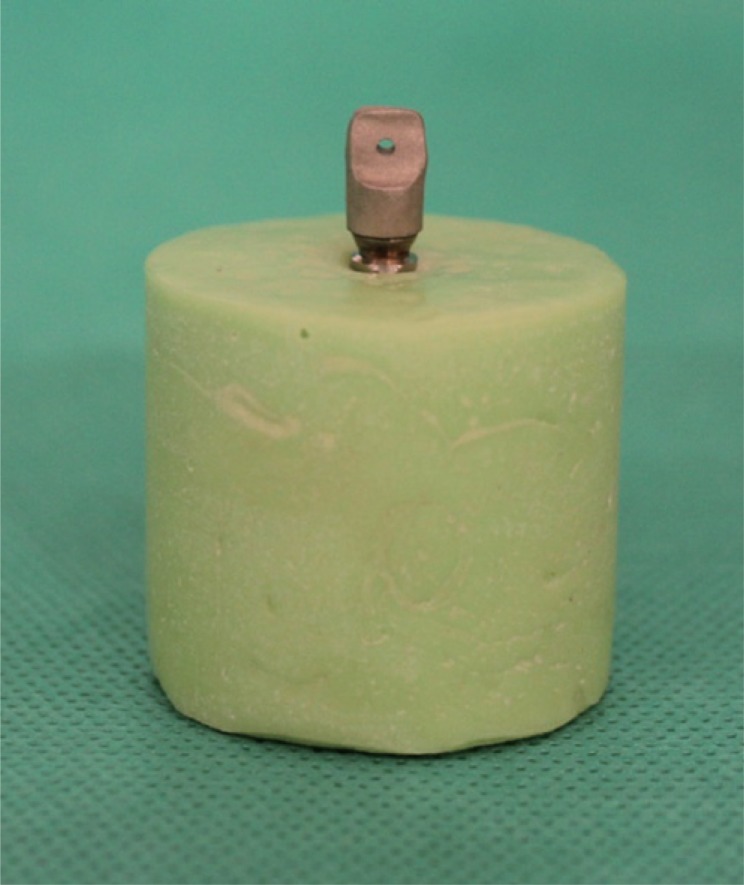

The means and standard deviations of each group are displayed in Table 1. The maximum pulling force for each cementation sub-group was recorded in the abutments with larger diameters. The maximum mean pull-out force pertained to resin cement in both initial cementation and re-cementation sub-groups but the difference between these two sub-groups were not significant. A 1-mm increase in diameter improved retention in all the groups (Fig. 5).

Table 1. Average and standard deviation of pull out force of different cement types with regard to diameter.

| Cement | Diameter | Mean | Std. Deviation | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resin cement | 4.5 | 364.1889 | 126.75385 | 9 |

| 5.5 | 460.4400 | 138.88363 | 10 | |

| Total | 414.8474 | 138.64697 | 19 | |

| RMGI | 4.5 | 154.0200 | 74.95793 | 10 |

| 5.5 | 243.6800 | 102.72642 | 10 | |

| Total | 198.8500 | 98.87186 | 20 | |

| ZOE | 4.5 | 115.9900 | 93.24225 | 10 |

| 5.5 | 164.7 | 125.47864 | 10 | |

| Total | 140.3450 | 110.45703 | 20 | |

| Recement | 4.5 | 352.8444 | 76.17413 | 9 |

| 5.5 | 405.4500 | 132.40771 | 10 | |

| Total | 380.5316 | 109.87738 | 19 | |

| Total | 4.5 | 240.8789 | 145.64482 | 38 |

| 5.5 | 318.5675 | 170.79451 | 40 | |

| Total | 280.7192 | 162.77362 | 78 |

Fig. 5. Average pulling force (N) in study group.

Two-way ANOVA showed that cement type significantly affected the retention of metal copings (F = 27.8, P < .001). Increasing the abutment diameter from 4.5 mm to 5.5 mm increased retention significantly (F = 8.05, P = .006). These two variables (cement type and abutment diameter) acted independently and did not exhibit any interactions (F = 0.23, P = .87) (Table 2).

Table 2. The effect of cement type and abutment diameter on the coping retention (Two-way ANOVA).

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected Model | 1.16886 | 7 | 166900.583 | 13.401 | .000 |

| Intercept | 6219167.828 | 1 | 6219167.828 | 499.342 | .000 |

| Cement | 1039734.469 | 3 | 346578.156 | 27.827 | .000a |

| Diameter | 100336.814 | 1 | 100336.814 | 8.056 | .006b |

| Cement * Diameter | 8837.691 | 3 | 2945.897 | .237 | .871c |

| Error | 871830.201 | 70 | 12454.717 | ||

| Total | 8186790.630 | 78 | |||

| Corrected Total | 2040134.281 | 77 |

a,b: Cement type and diameter significantly affect the retention of metal copings, c: Cement type and abutment diameter don't show any interactions.

Paired t-test showed that the retention difference between initial cementation and re-cementation with resin cement was not statistically significant (α = .40).

After removal of the coping, in all the groups most of the remaining cement was observed on the coping surface (81.25%); a few samples showed mixed failure (16.25%); and only two specimens exhibited most of the cement remnants on the abutment (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Failure mode for each study group.

DISCUSSION

Cement type and abutment diameter had significant effects on retention; thus the null hypothesis was rejected. The cement type affected retention significantly in short abutments. The registered retention force in resin cement group was considerably higher than that of RMGI or ZOE. Similar findings have been reported in previous studies as well.36,37,38

Re-cementation did not affect retention adversely and removal force in the re-cementation group was close to that in the initial cementation group with the use of the resin cement. Panavia resin cement contains 10-methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate (MDP), which forms a chemical bond with metallic oxides30 and yields high bond strength. The relatively minor alterations that occur during re-cementation do not affect the bond strength to adhesive resins. Ayad et al.23 investigated the effect of re-cementation. They compared GI, zinc phosphate, and resin cement (Panavia) and concluded that re-cementation only affected the zinc phosphate cement adversely.

When abutment height is not sufficient and retrievability is vital, resin-modified glass-ionomer is a suitable option. Resin-based cements can make up for the insufficient geometry (such as short abutment height) and thus are recommended in such occasions.38 In all the study groups, the abutments with larger diameter exhibited higher bond strength; therefore, increasing abutment diameter is recommended when the height is not sufficient.

Cano-Batalna and Sadig studied the effect of cement type, sandblasting, and abutment height and reported that all these factors affect the retention of implant-supported restorations, although Cano did not find a significant difference when abutment height increases from 4 mm to 5 mm or from 5 mm to 6 mm.31,37 These findings are consistent with our results. Carnaggio investigated the effect of cement type and contact surface area on the retention of full-ceramic CAD/CAM copings cemented to 3 different sizes of prefabricated abutments. According to him, retention values of RMGI are close to those of the temporary cements and surface area is less vital regarding the resin adhesives.27 According to Covey et al.,28 chemical composition of the cement affects the uniaxial retention force, but increasing the contact area does not improve the retention in wide abutments.28 Farzin and Cuncu reported that modifications in axial wall of the abutment did not change the retention significantly, but cement type significantly affected the retention force.6,22 On the other hand, Abbo showed that reducing the abutment height by 1 mm decreased the retention of zirconia copings significantly.1 In previous studies, the effect of abutment height, tapering, and axial wall alterations were investigated, but in our study, the variable was abutment diameter. All the abutments were reduced in height. In this study, all the three cement types were almost equally affected by an increase in diameter. Rödiger et al.21 studied the effect of abutment height and tapering and demonstrated that temporary lutings were affected by abutment height and tapering to a greater degree compared to semi-permanent luting agents.

The failure mode can be an important consideration in selecting a specific cement. In this study, most specimens exhibited adhesive failure (81.25%) at cement-abutment interface (most of the cement remained on the coping surface). Sandblasting the intaglio surface of the coping improves the micromechanical retention compared to the machined surface of the abutments.37 Adhesive failure is an advantage when retrievability is important since accessing the screw in the abutment is rather easy and the abutment will not be further damaged in an attempt to remove the remaining cement. Ebert et al.39 investigated the retention force of zirconia copings on 2.7-mm abutments and reported that cement mostly remained on the abutment surface, which is caused by prior air-borne particle abrasion of the abutments.

The type of dislodging force was one of the limitations of this study. The dynamic intraoral forces are different from the uniform static forces applied by the testing machine and the cemented restorations almost never dislodge vertically. Fatigue loading also alters the behavior of the cement, which must be further investigated in future studies. In this study, copings were milled from Cr-Co blocks (Sintron) and the results may not apply to gold, titanium, or zirconia copings. Manual mixing of the cement can affect the cement strength and it is advisable to use auto-mixed types if possible. Other types of cement, conditions of storage, thermocycling, and masticatory simulation should be studied. These in vitro studies and clinical trials can provide useful evidence and their results should be interpreted with caution.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of this study, it can be concluded that:

Adhesive resin cements are three times as strong as temporary cements and almost twice stronger than RMGI cements in implant-supported restorations with short abutment height. When the abutment height is not sufficient, increasing the diameter can considerably improve the retention of implant-supported restorations. Re-cementing the implant-supported copings over short abutments with adhesive resin cements does not adversely affect retention.

References

- 1.Abbo B, Razzoog ME, Vivas J, Sierraalta M. Resistance to dislodgement of zirconia copings cemented onto titanium abutments of different heights. J Prosthet Dent. 2008;99:25–29. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(08)60005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mish CE. Dental implant prosthetics. 2th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier Co.; 2015. pp. 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hebel KS, Gajjar RC. Cement-retained versus screw-retained implant restorations: achieving optimal occlusion and esthetics in implant dentistry. J Prosthet Dent. 1997;77:28–35. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(97)70203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chee WW, Torbati A, Albouy JP. Retrievable cemented implant restorations. J Prosthodont. 1998;7:120–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849x.1998.tb00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chee W, Felton DA, Johnson PF, Sullivan DY. Cemented versus screw-retained implant prostheses: which is better? Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1999;14:137–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Güncü MB, Cakan U, Canay S. Comparison of 3 luting agents on retention of implant-supported crowns on 2 different abutments. Implant Dent. 2011;20:349–353. doi: 10.1097/ID.0b013e318225f68e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akça K, Iplikçioğlu H, Cehreli MC. Comparison of uniaxial resistance forces of cements used with implant-supported crowns. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2002;17:536–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bresciano M, Schierano G, Manzella C, Screti A, Bignardi C, Preti G. Retention of luting agents on implant abutments of different height and taper. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2005;16:594–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2005.01159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim Y, Yamashita J, Shotwell JL, Chong KH, Wang HL. The comparison of provisional luting agents and abutment surface roughness on the retention of provisional implant-supported crowns. J Prosthet Dent. 2006;95:450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akin H, Guney U. Effect of various surface treatments on the retention properties of titanium to implant restorative cement. Lasers Med Sci. 2012;27:1183–1187. doi: 10.1007/s10103-011-1026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qeblawi DM, Muñoz CA, Brewer JD, Monaco EA., Jr The effect of zirconia surface treatment on flexural strength and shear bond strength to a resin cement. J Prosthet Dent. 2010;103:210–220. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(10)60033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kent DK, Koka S, Froeschle ML. Retention of cemented implant-supported restorations. J Prosthodont. 1997;6:193–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849x.1997.tb00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan YH, Lin TM, Liu PR, Ramp LC. Effect of luting agents on retention of dental implant-supported prostheses. J Oral Implantol. 2015;41:596–599. doi: 10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-13-00161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michalakis KX, Hirayama H, Garefis PD. Cement-retained versus screw-retained implant restorations: a critical review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2003;18:719–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahu N, Lakshmi N, Azhagarasan NS, Agnihotri Y, Rajan M, Hariharan R. Comparison of the effect of implant abutment surface modifications on retention of implant-supported restoration with a polymer based cement. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:239–242. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/7877.3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michalakis K, Pissiotis AL, Kang K, Hirayama H, Garefis PD, Petridis H. The effect of thermal cycling and air abrasion on cement failure loads of 4 provisional luting agents used for the cementation of implant-supported fixed partial dentures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2007;22:569–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee DH, Lee BJ, Kim SH, Lee KB. Shear bond strength of porcelain to a new millable alloy and a conventional castable alloy. J Prosthet Dent. 2015;113:329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JH. An accelerated technique for a ceramic-pressed-tometal restoration with CAD/CAM technology. J Prosthet Dent. 2014;112:1021–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suleiman SH, Vult von. Fracture strength of porcelain fused to metal crowns made of cast, milled or laser-sintered cobalt-chromium. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013;71:1280–1289. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2012.757650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim KB, Kim JH, Kim WC, Kim JH. Three-dimensional evaluation of gaps associated with fixed dental prostheses fabricated with new technologies. J Prosthet Dent. 2014;112:1432–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rödiger M, Rinke S, Ehret-Kleinau F, Pohlmeyer F, Lange K, Bürgers R, Gersdorff N. Evaluation of removal forces of implant-supported zirconia copings depending on abutment geometry, luting agent and cleaning method during re-cementation. J Adv Prosthodont. 2014;6:233–240. doi: 10.4047/jap.2014.6.3.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farzin M, Torabi K, Ahangari AH, Derafshi R. Effect of abutment modification and cement type on retention of cement-retained implant supported crowns. J Dent (Tehran) 2014;11:256–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayad MF, Rosenstiel SF, Woelfel JB. The effect of recementation on crown retention. Int J Prosthodont. 1998;11:177–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felton DA, Kanoy BE, White JT. Recementation of dental castings with zinc phosphate cement: effect on cement bond strength. J Prosthet Dent. 1987;58:579–583. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(87)90387-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ayad MF, Johnston WM, Rosenstiel SF. Influence of tooth preparation taper and cement type on recementation strength of complete metal crowns. J Prosthet Dent. 2009;102:354–361. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(09)60192-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cano-Batalla J, Soliva-Garriga J, Campillo-Funollet M, Munoz-Viveros CA, Giner-Tarrida L. Influence of abutment height and surface roughness on in vitro retention of three luting agents. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2012;27:36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carnaggio TV, Conrad R, Engelmeier RL, Gerngross P, Paravina R, Perezous L, Powers JM. Retention of CAD/CAM all-ceramic crowns on prefabricated implant abutments: an in vitro comparative study of luting agents and abutment surface area. J Prosthodont. 2012;21:523–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2012.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Covey DA, Kent DK, St Germain, Koka S. Effects of abutment size and luting cement type on the uniaxial retention force of implant-supported crowns. J Prosthet Dent. 2000;83:344–348. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(00)70138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nejatidanesh F, Savabi O, Ebrahimi M, Savabi G. Retentiveness of implant-supported metal copings using different luting agents. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2012;9:13–18. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.92921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nejatidanesh F, Savabi O, Jabbari E. Effect of surface treatment on the retention of implant-supported zirconia restorations over short abutments. J Prosthet Dent. 2014;112:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2013.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sadig WM, Al Harbi MW. Effects of surface conditioning on the retentiveness of titanium crowns over short implant abutments. Implant Dent. 2007;16:387–396. doi: 10.1097/ID.0b013e31815c8d7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White SN, Yu Z. Film thickness of new adhesive luting agents. J Prosthet Dent. 1992;67:782–785. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(92)90582-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernal G, Okamura M, Muñoz CA. The effects of abutment taper, length and cement type on resistance to dislodgement of cement-retained, implant-supported restorations. J Prosthodont. 2003;12:111–115. doi: 10.1016/S1059-941X(03)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinelli LA, Fais LM, Ricci WA, Reis JM. In vitro comparisons of casting retention on implant abutments among commercially available and experimental castor oil-containing dental luting agents. J Prosthet Dent. 2013;109:319–324. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(13)60308-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kokubo Y, Kano T, Tsumita M, Sakurai S, Itayama A, Fukushima S. Retention of zirconia copings on zirconia implant abutments cemented with provisional luting agents. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37:48–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2009.02013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan YH, Ramp LC, Lin CK, Liu PR. Comparison of 7 luting protocols and their effect on the retention and marginal leakage of a cement-retained dental implant restoration. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2006;21:587–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rappelli G, Corso M, Coccia E, Camaioni E, Di Felice R, Procaccini M. In vitro retentive strength of metal superstructures cemented to solid abutments. Minerva Stomatol. 2008;57:95–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garg P, Pujari ML, Prithviraj R, Khare S. Retentiveness of various luting agents used with implant-supported prosthesis: An in vitro study. J Oral Implantol. 2014;40:649–654. doi: 10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-12-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ebert A, Hedderich J, Kern M. Retention of zirconia ceramic copings bonded to titanium abutments. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2007;22:921–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]